ABSTRACT

Flaviviruses are positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses, including some well-known human pathogens such as Zika, dengue, and yellow fever viruses, which are primarily associated with mosquito and tick vectors. The vast majority of flavivirus research has focused on terrestrial environments; however, recent findings indicate that a range of flaviviruses are also present in aquatic environments, both marine and freshwater. These flaviviruses are found in various hosts, including fish, crustaceans, molluscs, and echinoderms. Although the effects of aquatic flaviviruses on the hosts they infect are not all known, some have been detected in farmed species and may have detrimental effects on the aquaculture industry. Exploration of the evolutionary history through the discovery of the Wenzhou shark flavivirus in both a shark and crab host is of particular interest since the potential dual-host nature of this virus may indicate that the invertebrate-vertebrate relationship seen in other flaviviruses may have a more profound evolutionary root than previously expected. Potential endogenous viral elements and the range of novel aquatic flaviviruses discovered thus shed light on virus origins and evolutionary history and may indicate that, like terrestrial life, the origins of flaviviruses may lie in aquatic environments.

KEYWORDS: aquatic virology, evolutionary history, Flaviviridae, flavivirus, marine virology

INTRODUCTION

Flaviviruses are positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses that belong to the Flaviviridae family. Their genomes tend to be ~11 kb in length containing a single open reading frame (ORF), and their viral particles are about 50 nm in size (1). The Flaviviridae family also includes the genera Pestivirus, Pegivirus, and Hepacivirus, of which hepatitis C virus is a well-known species (2).

Flaviviruses are commonly split into groups based on phylogenetic placement, host range, and modes of transmission. The most well-known flaviviruses are horizontally transmitted by hematophagous arthropod vectors such as mosquitoes (mosquito-borne flaviviruses [MBFV]) and ticks (tick-borne flaviviruses [TBFV]) to vertebrate hosts and are therefore called arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses). They have a wide primary host range, and infection can cause effects ranging from asymptomatic to fatal. Some well-known arboviruses significant to public health include yellow fever, dengue, Zika, and tick-borne encephalitis viruses (3). Other members of the Flavivirus genus are insect-specific flaviviruses (ISF) and those that are vertebrate-specific with no known arthropod vector (4). ISF are only capable of infecting insect hosts. A novel group of ISF is more closely grouped with MBFVs, showing that arthropod-borne flaviviruses are paraphyletic and flaviviruses acquired the ability to infect vertebrate hosts multiple times (5).

Since viruses evolve relatively quickly without leaving physical fossils, tracing their deep evolutionary history is particularly difficult. However, the discovery of endogenous viral elements (EVEs), including some related to flaviviruses, can provide much-needed indications about the viral past. EVEs are parts or complete genomes of viruses that have been integrated into the genome of their host (6). Although retroviruses rely on this integration as part of their replication cycle, other nonretroviral viruses, such as flavivirus-derived EVEs, have also been identified in various host genomes (7). EVEs result from the conjunction of rare events, starting with the production of DNA genomic material, followed by integration in the host’s genome in germ lines, possibly through interaction with retrotransposons (8, 9). In addition, after integration EVEs still need to overcome genetic drift and natural selection to reach fixation in the host population (8).

Because of these conditions, EVEs likely indicate long-term and intimate interactions between viruses and their hosts. As a result, they can act as genetic “fossils” to provide insight into host-virus interactions and their evolution (10). Flavivirus-derived EVEs have been primarily detected in arthropods, including mosquitoes (11–13) and ticks (14), but a recent study has expended this range (15).

Flaviviruses and flavi-like EVEs have been predominantly described in terrestrial environments. However, the recent rise in aquatic virus research and metagenomic studies may contribute to a better understanding of flavivirus evolution and origins. An exploration and review of known and novel flaviviruses and flavi-like EVEs in hosts found in aquatic environments, both marine and freshwater, can aid in understanding the diversity and origins of flaviviruses, and provide insight into the evolutionary history of dual-host flaviviruses and other arboviruses.

DISCOVERY OF AQUATIC FLAVIVIRUSES

Flaviviruses in aquatic tetrapods.

The majority of flavivirus research is focused on terrestrial species that are in contact with the two primary flavivirus vectors (mosquitoes and ticks). However, known flaviviruses have been found to make their way into aquatic or aquatic-adjacent environments. This includes isolated infection events of mosquito-borne flaviviruses, such as the West Nile virus and St. Louis encephalitis virus, in a select few marine mammals. St. Louis encephalitis infection occurred in a killer whale (Orcinus orca) at SeaWorld in Florida in 1990 (16). West Nile virus infection occurred in a harbor seal (Phoca vitulina) at the New Jersey Aquarium in 2006 (17) and in another killer whale at SeaWorld in San Antonio, Texas, in 2007 (18). Although mosquitoes predominantly transmit these from bird to bird, they can be transmitted to mammals under certain circumstances. The infected mammals may show symptoms of infection; however, they are considered “dead-end” hosts since mosquitoes are usually unable to get infected from these hosts (19). While the enclosed and artificial environments where these infections occurred may not be strictly marine, and while linked behavioral changes might enhance the risks of infection (20), these reports show that crossover can occur and that flaviviruses are not constrained to terrestrial species. Such transmission can happen in the wild, as suggested by the detection of antibodies to West Nile virus in wild Atlantic bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) off the coast of the eastern United States (21).

West Nile virus infections have also been described in crocodilian species, such as American alligators (Alligator mississippiensi) in Florida in 2001 and 2002 (22, 23), Nile crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus) in Zambia in 2017 (24), and saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) in Australia in 2016 (25). Exposition to the same virus, estimated by the presence of antibodies, has been characterized in Mexico (26), Israel (27), and Australia (28) in various species. Interestingly, West Nile virus transmission between crocodilian hosts might be vector independent and mediated by exposition to contaminated water (25, 29).

Fishes.

Flaviviruses have also been found in a variety of fish species. A large-scale metatranscriptomic study discovered 214 vertebrate-associated viruses, including one flavivirus, Wenzhou shark flavivirus, in a Pacific spadenose shark (Scoliodon macrorhynchos) (30). Two metatranscriptomic studies of fish in Australia revealed fragments of a novel flavivirus in the Eastern red scorpionfish (Scorpaena jacksoniensis) (31) and the Western carp gudgeon (Hypseleotris klunzingeri) (32). Other flaviviruses found in fish include Cyclopterus lumpus flavivirus (33) and a flavivirus identified in the Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), both of which show features uncharacteristic of typical flaviviruses, such as dual ORFs (34, 35).

Several flavi-like EVEs have also been identified in marine ray-finned fish, including tube-eyed deep-sea fish (Stylephorus chordatus), common deep-sea mora (Mora moro), pufferfish (Takifugu), phycid hakes (Phycis), cusk (Brosme brosme), and blue-spotted mudskipper (Boleophthalmus pectinirostris) (15).

A putative EVE sequence was also discovered in several other fish, including medaka/Japanese rice fish (Oryzias latipes), showing a low sequence identity to the Tamana bat virus. However, it is not confirmed whether this is actually an EVE or an exogenous virus sequence or sample contaminant (36). Flavi-like EVEs have also been identified in the mangrove killifish (Austrofundulus limnaeus) and the Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii) (15).

Aquatic arthropods.

A flavivirus sequence was extracted from a marine arthropod, the sea spider Endeis spinosa. Further analysis indicated that this flavivirus was more closely related to insect-specific flaviviruses. It was also unclear whether the Endeis spinosa NS5 flavivirus (ESNS5) discovered was from an active infection or an EVE from a past or recent integration event (37). Another flavi-like EVE has been recently identified in a calanoid copepod (Eurytemora affinis) (15).

Variants of the Wenzhou shark flavivirus have been identified in multiple Gazami crab (Portunus trituberculatus) populations (34, 38). This flavivirus’ dual-host and horizontally transmitted nature is supported by genetic similarity, proof of replication within Portunus trituberculatus through RNAi (RNA interference) immune responses, and both shark and crab populations living in overlapping locations (34). The discovery of this new vertebrate-invertebrate host association can be important in understanding the evolutionary history and origins of vector-borne viruses; past research has only identified these associated with terrestrial arthropod vectors such as mosquitoes and ticks.

Multiple flavi-like viruses have been found in the brown shrimp (Crangon crangon) (34, 39). The Crangon crangon flavi-like virus 1 (CcFLV1) genome was significantly shorter and clustered with the previously discovered Crangon crangon flavivirus and the two amphipod viruses. On the other hand, the Crangon crangon flavi-like virus 2 (CcFLV2) genome was larger than CcFLV1 and other viruses within the Flaviviridae family (39), similar to other flavi-like viruses found in other organisms (40).

Interestingly, flaviviruses have also been found in freshwater crustaceans such as two amphipod species, Gammarus pulex and Gammarus chevreuxi (34), as well as the planktonic crustacean Daphnia magna (30, 34), the tadpole shrimp (Lepidurus arcticus) (34), and the Amano shrimp (Caridina multidentata) (38). These sequences seem closely related to insect-infecting viruses, and their presence within crustacean genomes suggests an overall long coevolutionary history between flaviviruses and arthropods (34).

A novel Flaviviridae-associated infectious precocity virus was also discovered in giant freshwater prawns (Macrobrachium rosenbergii). Although this virus was similar in genomic structure and organization to known flaviviruses, it was only phylogenetically distantly related to other flaviviruses, showing only 30% amino acid sequence identity to the closest flavivirus (41).

Molluscs, echinoderms, and cnidarians.

Additional flaviviruses were found in cephalopod species, the Firefly squid (Watasenia scintillans) and the Southern pygmy squid (Idiosepius notoides). These cephalopod flaviviruses seem more closely related to previously discovered marine flaviviruses, such as the Wenzhou shark flavivirus, than to crustacean flaviviruses (34).

A flavivirus-like genome fragment has also been discovered in the California sea cucumber (Apostichopus californicus). It was found in a metagenomic study of holothurian samples from various locations. The structure of this flavivirus-like fragment was similar to insect-specific flaviviruses and seemed closely related to the Wenzhou shark flavivirus (42). The virus sequence was extended during an examination of the RNA virome of echinoderms, completing a second ORF (43). Finally, flavi-like EVEs have also been identified in the freshwater jellyfish (Craspedacusta sowerbii) (15).

Untargeted metagenomics in aquatic environments.

Two recent studies also identified viral sequences associated with flaviviruses in aquatic environments. The first one leverages the impressive Tara Oceans RNA sequence data and found multiple flavi-like sequences in samples. These correspond with eukaryotic size fragment metatranscriptomes in various sampling sites across the Arctic, Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, as well as in the Mediterranean Sea (44). The second study identifies flavi-like sequences in metatranscriptomes of samples collected in sediments from freshwater aquatic environments in multiple regions of China (45). These reports, however, do not indicate the nature of these sequences, making it unclear whether they derive from EVEs or exogenous viruses. In addition, they provide limited insights about the original hosts.

Phylogenetic relationships.

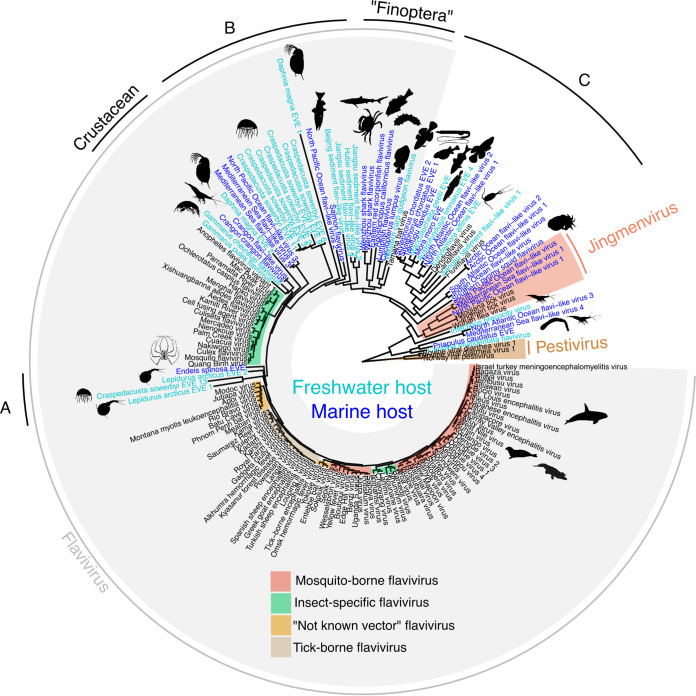

Aquatic flaviviruses are diverse and do not form a monophyletic clade (Fig. 1). The diversity is important and expanding, limiting the fine resolution of the evolutionary relationship as inferred by phylogenetic trees. Interestingly, however, viruses or virus-derived sequences found in freshwater or marine hosts are mixed, and there is no evidence for phylogenetic clustering based on host ecology.

FIG 1.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of the NS5 (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) amino acid sequences of flaviviruses, trimmed with BMGE v1.2 (66), under an LG+F+R8 protein substitution model in IQ-TREE v1.6.12 (67). Aquatic host-linked flaviviruses are highlighted in blue—light blue for freshwater hosts or dark blue for marine hosts. A, B, and C refer to clades that have not yet been tentatively named. The Tree file, alignment, and table containing accession numbers of used sequences are available on GitHub (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6980038).

Several endogenous viral elements in aquatic invertebrates are related to mosquito-borne flaviviruses (Fig. 1,A). Some crustacean flaviviruses (Fig. 1, Crustacean) form a group related to insect-specific flaviviruses, supporting the existence of a broader “arthropod-specific” flavivirus group. This could extend to a pan-invertebrate group (Fig. 1,B), including sequences from jellyfish and metatranscriptomes data from marine and freshwater environments. The “Finoptera” (fins and wings) clade (35), related to the Tamana bat virus, contains viruses infecting fish and invertebrates (crustaceans and echinoderms) (Fig. 1, “Finoptera”). Another clade, probably outside the Flavivirus genus, is associated with fish, crustaceans, and sequences from metatranscriptomes of both marine and freshwater environments (Fig. 1,C). This clade is also associated with recently discovered viruses (Dendroflavili, Candiflavili, and Fluviflavili viruses) in parasitic flatworms (46). Interestingly, a few sequences identified in the Tara Ocean sequence data are also related to the jingmenviruses; a new, segmented group of viruses initially identified in ticks (47). This might suggest a much broader host range of jingmenviruses than previously discovered.

While there is some indication of clustering by host group (e.g., vertebrates/invertebrates), most clades present a mix of host species. Similar mixing can be observed in other RNA virus families, such as the Nodaviridae, where viruses were found in fish and diverse marine arthropods such as copepods, barnacles, horseshoe crabs, and decapods (38). Similarly, a caligrhavirus (Rhabdoviridae) found in fish parasites (sea lice) was found to be related to fish-infecting viruses (38).

IMPACT ON HOST HEALTH

Not all symptoms and effects of flaviviruses found in aquatic species are known; however, it is thought that some cause disease and can be harmful to the host they infect. An example of this is the previously mentioned Cyclopterus lumpus flavivirus, which is thought to be associated with a disease in lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus) primarily affecting the liver and kidney (33). Similarly, the detection of the salmon flavivirus (SFV) came as a result of unexplained death and uncharacteristic behavior in Chinook salmon in California, although clinical signs could not be clearly linked to infection by SFV (35).

Another example is the infectious precocity virus affecting giant freshwater prawns (Macrobrachium rosenbergii), which is thought to be associated with iron prawn syndrome (IPS), which reduces their growth by up to 50% compared to noninfected prawns (48). When considering the diseases with which these flaviviruses are associated, it may be important to note that IPS occurs in farmed prawns and has been the cause of substantial losses in production.

Aquaculture has become one of the leading sectors of animal-derived food production (49). However, farming activity can provide an ideal environment for the emergence and spread of viruses and other infectious diseases. This can be attributed to a combination of factors such as the cointroduction of these infectious diseases into the farmed environment, increased susceptibility due to the low genetic diversity of farmed populations, and higher stock densities than found in natural environments (50). While infectious diseases in aquaculture can have a detrimental impact on aquaculture production, the transmission of these viruses is not always constrained to farmed environments. Interactions facilitated by environmental factors and movement between farming sites may impact wild populations (51, 52). Salmon species, for example, have experienced declining populations due to a range of environmental factors and human impacts (53), and pathogen emergence may also play a role in this decline. The presence of infectious diseases in general, including flaviviruses, highlights the importance of further research in both farmed and wild species to understand the emergence and history of these viruses, as well as to assess the ecological and commercial impacts.

MODES OF TRANSMISSION

The Wenzhou shark flavivirus presenting itself in both an invertebrate and vertebrate host calls for revisiting the evolutionary history of arthropod-borne flaviviruses. These dual-host invertebrate-vertebrate viruses may have a more profound evolutionary history than initially thought (34). Well-known dual-host flaviviruses are often associated with arthropod vectors such as mosquitoes and ticks; however, these findings may indicate that this relationship extends beyond hematophagous vectors to arthropods in general, including crustaceans. With more supporting evidence and further research, this may be important in understanding the emergence of terrestrial vector-borne viruses and horizontal transfer between unrelated, drastically different species.

This idea may also extend to other viral families. For example, a study identified a putative RNA virus phylogenetically associated with the arthropod-infecting Negevirus genus in both an invertebrate parasite and the spleen and pancreas of a wild Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), indicating that dual-host transmission between two unrelated organisms may be occurring (54). This reflects and supports that some viruses can be transmitted horizontally between vertebrates and invertebrates in aquatic environments. Although neither study gives an explicit and fully confirmed example of dual-host viruses in an aquatic environment, they allude to their existence across various viral families.

Modes of transmission of these novel viruses discovered in aquatic environments are also still predominantly unknown. It seems uncertain whether infections are transmitted vertically or horizontally between individuals of the same or different species. Ecological niches and habitats may play a role in virus transmission between different species. It has been suggested that some of these viruses could be transmitted horizontally via parasites or down the natural food chain (35). Alternatively, the detection of SFV in the ovarian fluids of salmon might suggest vertical transmission from parent to offspring. Other flaviviruses are capable of vertical transmission, both in vertebrates such as Zika virus in humans (55) and in invertebrates such as mosquitoes (56). Because modes of transmission are yet to be characterized for most newly discovered aquatic flaviviruses, it is challenging to determine the exact nature of their interaction with their hosts.

The infective nature of the majority of these viruses is also unknown. It is also possible that crustaceans are a vector similar to known terrestrial vector-borne flaviviruses that have an arthropod vector and infect vertebrates. A select few aquatic flaviviruses had similar nucleotide composition to mosquito-borne flaviviruses (MBFV), suggesting that they may circulate between invertebrates and vertebrates similarly to MBFV (57). These findings have led to speculation about the possible evolutionary history of flaviviruses, including the idea that terrestrial vector-borne viruses may have evolved from marine ancestors (34). However, proposed hypotheses concerning the evolutionary history of flaviviruses can only be resolved with more research and context.

CONCLUSIONS

Flavivirus divergence has previously been estimated to have occurred relatively recently between 64,000 and 159,000 years ago; a time period that aligns virus evolution with biogeographical migration events (58). However, the abundance of novel aquatic flaviviruses which may have emerged before other known flaviviruses may alter this even more drastically, potentially pushing the origins of flaviviruses closer to the emergence of metazoans some 750 to 800 million years ago (MYA) (59). The previously mentioned discovery of flavivirus EVEs in freshwater jellyfish also suggests that flaviviruses may have existed 500 to 800 MYA (15).

Tracing the deep evolutionary history of viruses can be difficult. However, it is thought that horizontal virus transfer between diverse hosts lies at its core and that viruses have evolved alongside these hosts. A hypothetical evolutionary history of flaviviruses describes a continuous line of descent from RNA phages to picorna-like viruses to the late emergence of flavi-like viruses (60). The context provided by novel aquatic flaviviruses and putative EVEs supports this hypothesis; however, more virome sampling of aquatic species across a range of marine and freshwater environments is necessary for further support and understanding Flavivirus evolution and virus evolution as a whole. Although virus origins are not explicitly known, new findings reviewed here indicate that, like terrestrial life, the answers may lie in aquatic environments. The discovery of endogenous retroviruses in ray-finned fish has already suggested that the origin of retroviruses may lie in marine settings (61).

Recent meta-transcriptomic studies (44, 45) or mining of publicly available data sets (see, for example, reference 62) provide an unprecedented expansion of the known genomic diversity of eukaryotic viral families, including Flaviviridae. However, they present limited insights into the nature of these sequences (EVEs or exogenous viruses) and, for meta-transcriptomic studies, the identification of the natural host. Moreover, they cannot provide crucial information about the ecology of these viruses, including transmission mechanisms, pathogenic potential, and ways through which they can impact their ecosystem (63–65). The high abundance of existing and newly discovered viruses and how little is known about their presence and ecology within aquatic environments as a whole provides a large area for potential research. The intersection of virology and marine sciences may be important in forming a better understanding of both disciplines.

Contributor Information

Sebastian Lequime, Email: s.j.j.lequime@rug.nl.

Ted C. Pierson, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

REFERENCES

- 1.Lindenbach BD, Thiel HJ, Rice CM. 2007. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication, p 1101–1152. In Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott/Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simmonds P, Becher P, Bukh J, Gould EA, Meyers G, Monath T, Muerhoff S, Pletnev A, Rico-Hesse R, Smith DB, Stapleton JT, ICTV Report Consortium . 2017. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Flaviviridae. J Gen Virol 98:2–3. 10.1099/jgv.0.000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pierson TC, Diamond MS. 2020. The continued threat of emerging flaviviruses. Nat Microbiol 5:796–812. 10.1038/s41564-020-0714-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moureau G, Cook S, Lemey P, Nougairede A, Forrester NL, Khasnatinov M, Charrel RN, Firth AE, Gould EA, de Lamballerie X. 2015. New insights into flavivirus evolution, taxonomy and biogeographic history, extended by analysis of canonical and alternative coding sequences. PLoS One 10:e0117849. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blitvich B, Firth A. 2015. Insect-specific flaviviruses: a systematic review of their discovery, host range, mode of transmission, superinfection exclusion potential and genomic organization. Viruses 7:1927–1959. 10.3390/v7041927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feschotte C, Gilbert C. 2012. Endogenous viruses: insights into viral evolution and impact on host biology. Nat Rev Genet 13:283–296. 10.1038/nrg3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katzourakis A, Gifford RJ. 2010. Endogenous viral elements in animal genomes. PLoS Genet 6:e1001191. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes EC. 2011. The evolution of endogenous viral elements. Cell Host Microbe 10:368–377. 10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horie M. 2020. Interactions among eukaryotes, retrotransposons and riboviruses: endogenous riboviral elements in eukaryotic genomes. Genes Genet Syst 94:253–267. 10.1266/ggs.18-00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horie M, Tomonaga K. 2011. Nonretroviral fossils in vertebrate genomes. Viruses 3:1836–1848. 10.3390/v3101836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crochu S, Cook S, Attoui H, Charrel RN, De Chesse R, Belhouchet M, Lemasson J-J, de Micco P, de Lamballerie X. 2004. Sequences of flavivirus-related RNA viruses persist in DNA form integrated in the genome of Aedes spp. mosquitoes. J Gen Virol 85:1971–1980. 10.1099/vir.0.79850-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lequime S, Lambrechts L. 2017. Discovery of flavivirus-derived endogenous viral elements in Anopheles mosquito genomes supports the existence of Anopheles-associated insect-specific flaviviruses. Virus Evol 3:vew035. 10.1093/ve/vew035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roiz D, Vázquez A, Seco M, Tenorio A, Rizzoli A. 2009. Detection of novel insect flavivirus sequences integrated in Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Northern Italy. Virol J 6:93. 10.1186/1743-422X-6-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maruyama SR, Castro-Jorge LA, Ribeiro JMC, Gardinassi LG, Garcia GR, Brandão LG, Rodrigues AR, Okada MI, Abrão EP, Ferreira BR, da Fonseca BAL, de Miranda-Santos IKF. 2014. Characterization of divergent flavivirus NS3 and NS5 protein sequences detected in Rhipicephalus microplus ticks from Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 109:38–50. 10.1590/0074-0276130166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bamford CGG, de Souza WM, Parry R, Gifford RJ. 2021. Comparative analysis of genome-encoded viral sequences reveals the evolutionary history of the Flaviviridae. Evol Biol preprint. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.09.19.460981v3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buck C, Paulino GP, Medina DJ, Hsiung GD, Campbell TW, Walsh MT. 1993. Isolation of St. Louis encephalitis virus from a killer whale. Clin Diagn Virol 1:109–112. 10.1016/0928-0197(93)90018-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piero FD, Stremme DW, Habecker PL, Cantile C. 2006. West Nile flavivirus polioencephalomyelitis in a harbor seal (Phoca vitulina). Vet Pathol 43:58–61. 10.1354/vp.43-1-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.St Leger J. 2011. West Nile virus infection in killer whale, Texas, USA, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis 17:1531–1533. 10.3201/eid1708.101979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahlers LRH, Goodman AG. 2018. The immune responses of the animal hosts of West Nile virus: a comparison of insects, birds, and mammals. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8:96. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jett J, Ventre J. 2012. Orca (Orcinus orca) captivity and vulnerability to mosquito-transmitted viruses. J Mar Anim Ecol 5:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaefer AM, Reif JS, Goldstein JD, Ryan CN, Fair PA, Bossart GD. 2009. Serological evidence of exposure to selected viral, bacterial, and protozoal pathogens in free-ranging Atlantic bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) from the Indian River Lagoon, Florida, and Charleston, South Carolina. Aquatic Mammals 35:163–170. 10.1578/AM.35.2.2009.163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson ER, Ginn PE, Troutman JM, Farina L, Stark L, Klenk K, Burkhalter KL, Komar N. 2005. West Nile virus infection in farmed American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) in Florida. J Wildl Dis 41:96–106. 10.7589/0090-3558-41.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller DL, Mauel MJ, Baldwin C, Burtle G, Ingram D, Hines ME, Frazier KS. 2003. West Nile virus in farmed alligators. Emerg Infect Dis 9:794–799. 10.3201/eid0907.030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simulundu E, Ndashe K, Chambaro HM, Squarre D, Reilly PM, Chitanga S, Changula K, Mukubesa AN, Ndebe J, Tembo J, Kapata N, Bates M, Sinkala Y, Hang’ombe BM, Nalubamba KS, Kajihara M, Sasaki M, Orba Y, Takada A, Sawa H. 2020. West Nile virus in farmed crocodiles, Zambia, 2019. Emerg Infect Dis 26:811–814. 10.3201/eid2604.190954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Habarugira G, Moran J, Colmant AMG, Davis SS, O’Brien CA, Hall-Mendelin S, McMahon J, Hewitson G, Nair N, Barcelon J, Suen WW, Melville L, Hobson-Peters J, Hall RA, Isberg SR, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. 2020. Mosquito-independent transmission of West Nile virus in farmed saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus). Viruses 12:198. 10.3390/v12020198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Machain-Williams C, Padilla-Paz SE, Weber M, Cetina-Trejo R, Juarez-Ordaz JA, Loroño-Pino MA, Ulloa A, Wang C, Garcia-Rejon J, Blitvich BJ. 2013. Antibodies to West Nile virus in wild and farmed crocodiles in southeastern Mexico. J Wildl Dis 49:690–693. 10.7589/2012-11-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinman A, Banet-Noach C, Tal S, Levi O, Simanov L, Perk S, Malkinson M, Shpigel N. 2003. West Nile virus infection in crocodiles. Emerg Infect Dis 9:887–889. 10.3201/eid0907.020816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habarugira G, Moran J, Harrison JJ, Isberg SR, Hobson-Peters J, Hall RA, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. 2022. Evidence of infection with zoonotic mosquito-borne flaviviruses in saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) in northern Australia. Viruses 14:1106. 10.3390/v14051106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byas AD, Gallichotte EN, Hartwig AE, Porter SM, Gordy PW, Felix TA, Bowen RA, Ebel GD, Bosco-Lauth AM. 2022. American alligators are capable of West Nile virus amplification, mosquito infection, and transmission. Virology 568:49–55. 10.1016/j.virol.2022.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi M, Lin X-D, Chen X, Tian J-H, Chen L-J, Li K, Wang W, Eden J-S, Shen J-J, Liu L, Holmes EC, Zhang Y-Z. 2018. The evolutionary history of vertebrate RNA viruses. Nature 556:197–202. 10.1038/s41586-018-0012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geoghegan JL, Di Giallonardo F, Cousins K, Shi M, Williamson JE, Holmes EC. 2018. Hidden diversity and evolution of viruses in market fish. Virus Evol 4:vey031. 10.1093/ve/vey031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costa VA, Mifsud JCO, Gilligan D, Williamson JE, Holmes EC, Geoghegan JL. 2021. Metagenomic sequencing reveals a lack of virus exchange between native and invasive freshwater fish across the Murray–Darling Basin, Australia. Virus Evol 7:veab034. 10.1093/ve/veab034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skoge RH, Brattespe J, Økland AL, Plarre H, Nylund A. 2018. New virus of the family Flaviviridae detected in lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus). Arch Virol 163 10.1007/s00705-017-3643-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parry R, Asgari S. 2019. Discovery of novel crustacean and cephalopod flaviviruses: insights into the evolution and circulation of flaviviruses between marine invertebrate and vertebrate hosts. J Virol 93:e00432-19. 10.1128/JVI.00432-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soto E, Camus A, Yun S, Kurobe T, Leary JH, Rosser TG, Dill-Okubo JA, Nyaoke AC, Adkison M, Renger A, Ng TFF. 2020. First isolation of a novel aquatic flavivirus from Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) and its in vivo replication in a piscine animal model. J Virol 94:e00337-20. 10.1128/JVI.00337-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belyi VA, Levine AJ, Skalka AM. 2010. Unexpected inheritance: multiple integrations of ancient bornavirus and ebolavirus/marburgvirus sequences in vertebrate genomes. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001030. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conway MJ. 2015. Identification of a Flavivirus Sequence in a Marine Arthropod. PLoS One 10:e0146037. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang T, Hirai J, Hunt BPV, Suttle CA. 2021. Arthropods and the evolution of RNA viruses. Microbiology preprint. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.05.30.446314v1.full. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Eynde B, Christiaens O, Delbare D, Shi C, Vanhulle E, Yinda CK, Matthijnssens J, Smagghe G. 2020. Exploration of the virome of the European brown shrimp (Crangon crangon). J Gen Virol 101:651–666. 10.1099/jgv.0.001412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paraskevopoulou S, Käfer S, Zirkel F, Donath A, Petersen M, Liu S, Zhou X, Drosten C, Misof B, Junglen S. 2021. Viromics of extant insect orders unveil the evolution of the flavi-like superfamily. Virus Evol 7:veab030. 10.1093/ve/veab030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong X, Wang G, Hu T, Li J, Li C, Cao Z, Shi M, Wang Y, Zou P, Song J, Gao W, Meng F, Yang G, Tang KFJ, Li C, Shi W, Huang J. 2021. A novel virus of Flaviviridae associated with sexual precocity in Macrobrachium rosenbergii. mSystems 6:e00003-21. 10.1128/mSystems.00003-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hewson I, Johnson MR, Tibbetts IR. 2020. An unconventional flavivirus and other RNA viruses in the sea cucumber (Holothuroidea; Echinodermata) virome. Viruses 12:1057. 10.3390/v12091057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jackson EW, Wilhelm RC, Buckley DH, Hewson I. 2022. The RNA virome of echinoderms. Microbiology preprint. 10.1099/jgv.0.001772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zayed AA, Wainaina JM, Dominguez-Huerta G, Pelletier E, Guo J, Mohssen M, Tian F, Pratama AA, Bolduc B, Zablocki O, Cronin D, Solden L, Delage E, Alberti A, Aury J-M, Carradec Q, da Silva C, Labadie K, Poulain J, Ruscheweyh H-J, Salazar G, Shatoff E, Bundschuh R, Tara Oceans Coordinators, et al. 2022. Cryptic and abundant marine viruses at the evolutionary origins of Earth’s RNA virome. Science 376:156–162. 10.1126/science.abm5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Y-M, Sadiq S, Tian J-H, Chen X, Lin X-D, Shen J-J, Chen H, Hao Z-Y, Yang W-D, Zhou Z-C, Wu J, Li F, Wang H-W, Xu Q-Y, Wang W, Gao W-H, Holmes EC, Zhang Y-Z. 2021. RNA virome composition is shaped by sampling ecotype. SSRN Electron J 10.2139/ssrn.3934022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dheilly NM, Lucas P, Blanchard Y, Rosario K. 2022. A world of viruses nested within parasites: unraveling viral diversity within parasitic flatworms (Platyhelminthes). Microbiol Spectr 10:e00138-22. 10.1128/spectrum.00138-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi M, Lin X-D, Vasilakis N, Tian J-H, Li C-X, Chen L-J, Eastwood G, Diao X-N, Chen M-H, Chen X, Qin X-C, Widen SG, Wood TG, Tesh RB, Xu J, Holmes EC, Zhang Y-Z. 2016. Divergent viruses discovered in arthropods and vertebrates revise the evolutionary history of the Flaviviridae and related viruses. J Virol 90:659–669. 10.1128/JVI.02036-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou JM, Dai XL, Jiang F, Ding FJ. 2017. The preliminary analysis of the reasons for the poor growth of Macrobrachium rosenbergii in pond. J Shanghai Ocean Univ 26:853–861. [Google Scholar]

- 49.FAO. 2020. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2020. FAO, Rome, Italy. http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ca9229en. Accessed 14 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bouwmeester MM, Goedknegt MA, Poulin R, Thieltges DW. 2021. Collateral diseases: aquaculture impacts on wildlife infections. J Appl Ecol 58:453–464. 10.1111/1365-2664.13775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kibenge FS. 2019. Emerging viruses in aquaculture. Curr Opin Virol 34:97–103. 10.1016/j.coviro.2018.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mordecai GJ, Miller KM, Bass AL, Bateman AW, Teffer AK, Caleta JM, Di Cicco E, Schulze AD, Kaukinen KH, Li S, Tabata A, Jones BR, Ming TJ, Joy JB. 2021. Aquaculture mediates global transmission of a viral pathogen to wild salmon. Sci Adv 7:eabe2592. 10.1126/sciadv.abe2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katz J, Moyle PB, Quiñones RM, Israel J, Purdy S. 2013. Impending extinction of salmon, steelhead, and trout (Salmonidae) in California. Environ Biol Fish 96:1169–1186. 10.1007/s10641-012-9974-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mordecai GJ, Di Cicco E, Günther OP, Schulze AD, Kaukinen KH, Li S, Tabata A, Ming TJ, Ferguson HW, Suttle CA, Miller KM. 2021. Discovery and surveillance of viruses from salmon in British Columbia using viral immune-response biomarkers, metatranscriptomics, and high-throughput RT-PCR. Virus Evol 7:veaa069. 10.1093/ve/veaa069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ades AE, Soriano-Arandes A, Alarcon A, Bonfante F, Thorne C, Peckham CS, Giaquinto C. 2021. Vertical transmission of Zika virus and its outcomes: a Bayesian synthesis of prospective studies. Lancet Infect Dis 21:537–545. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30432-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lequime S, Paul RE, Lambrechts L. 2016. Determinants of arbovirus vertical transmission in mosquitoes. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005548. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harima H, Orba Y, Torii S, Qiu Y, Kajihara M, Eto Y, Matsuta N, Hang’ombe BM, Eshita Y, Uemura K, Matsuno K, Sasaki M, Yoshii K, Nakao R, Hall WW, Takada A, Abe T, Wolfinger MT, Simuunza M, Sawa H. 2021. An African tick flavivirus forming an independent clade exhibits unique exoribonuclease-resistant RNA structures in the genomic 3′-untranslated region. Sci Rep 11:4883. 10.1038/s41598-021-84365-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pettersson JH-O, Fiz-Palacios O. 2014. Dating the origin of the genus Flavivirus in the light of Beringian biogeography. J Gen Virol 95:1969–1982. 10.1099/vir.0.065227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Erwin DH. 2015. Early metazoan life: divergence, environment and ecology. Philos Trans R Soc B 370:20150036. 10.1098/rstb.2015.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dolja VV, Koonin EV. 2018. Metagenomics reshapes the concepts of RNA virus evolution by revealing extensive horizontal virus transfer. Virus Res 244:36–52. 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aiewsakun P, Katzourakis A. 2017. Marine origin of retroviruses in the early Palaeozoic Era. Nat Commun 8:13954. 10.1038/ncomms13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Edgar RC, Taylor J, Lin V, Altman T, Barbera P, Meleshko D, Lohr D, Novakovsky G, Buchfink B, Al-Shayeb B, Banfield JF, de la Peña M, Korobeynikov A, Chikhi R, Babaian A. 2022. Petabase-scale sequence alignment catalyses viral discovery. Nature 602:142–147. 10.1038/s41586-021-04332-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.French RK, Holmes EC. 2020. An ecosystems perspective on virus evolution and emergence. Trends Microbiol 28:165–175. 10.1016/j.tim.2019.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roux S, Matthijnssens J, Dutilh BE. 2021. Metagenomics in virology, p 133–140. In Encyclopedia of virology. Elsevier, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sommers P, Chatterjee A, Varsani A, Trubl G. 2021. Integrating viral metagenomics into an ecological framework. Annu Rev Virol 8:133–158. 10.1146/annurev-virology-010421-053015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Criscuolo A, Gribaldo S. 2010. BMGE (Block Mapping and Gathering with Entropy): a new software for selection of phylogenetic informative regions from multiple sequence alignments. BMC Evol Biol 10:210. 10.1186/1471-2148-10-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 32:268–274. 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]