ABSTRACT

Apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing catalytic polypeptide-like 3 family members (APOBEC3s) are host restriction factors that inhibit viral replication. Viral infectivity factor (Vif), a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) accessory protein, mediates the degradation of APOBEC3s by forming the Vif-E3 complex, in which core-binding factor beta (CBFβ) is an essential molecular chaperone. Here, we screened nonfunctional Vif mutants with high affinity for CBFβ to inhibit HIV-1 in a dominant negative manner. We applied the yeast surface display technology to express Vif random mutant libraries, and mutants showing high CBFβ affinity were screened using flow cytometry. Most of the screened Vif mutants containing random mutations of different frequencies were able to rescue APOBEC3G (A3G). In the subsequent screening, three of the mutants restricted HIV-1, recovered G-to-A hypermutation, and rescued APOBEC3s. Among them, Vif-6M showed a cross-protection effect toward APOBEC3C, APOBEC3F, and African green monkey A3G. Stable expression of Vif-6M in T lymphocytes inhibited the viral replication in newly HIV-1-infected cells and the chronically infected cell line H9/HXB2. Furthermore, the expression of Vif-6M provided a survival advantage to T lymphocytes infected with HIV-1. These results suggest that dominant negative Vif mutants acting on the Vif-CBFβ target potently restrict HIV-1.

IMPORTANCE Antiviral therapy cannot eliminate HIV and exhibits disadvantages such as drug resistance and toxicity. Therefore, novel strategies for inhibiting viral replication in patients with HIV are urgently needed. APOBEC3s in host cells are able to inhibit viral replication but are antagonized by HIV-1 Vif-mediated degradation. Therefore, we screened nonfunctional Vif mutants with high affinity for CBFβ to compete with the wild-type Vif (wtVif) as a potential strategy to assist with HIV-1 treatment. Most screened mutants rescued the expression of A3G in the presence of wtVif, especially Vif-6M, which could protect various APOBEC3s and improve the incorporation of A3G into HIV-1 particles. Transduction of Vif-6M into T lymphocytes inhibited the replication of the newly infected virus and the chronically infected virus. These data suggest that Vif mutants targeting the Vif-CBFβ interaction may be promising in the development of a new AIDS therapeutic strategy.

KEYWORDS: apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing catalytic polypeptide-like 3 family member (APOBEC3), core-binding factor beta (CBFβ), dominant negative mutant, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), viral infectivity factor (Vif)

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is a retrovirus that affects the human immune system. In addition to the structural and enzyme proteins (Gag, Pol, and Env) encoded by all retroviruses, HIV-1 encodes six accessory proteins (Vif, Vpr, Tat, Rev, Vpu, and Nef) (1). Viral infectivity factor (Vif) protein plays an important role in the replication of HIV-1 (2). Apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing catalytic polypeptide-like 3 family members (APOBEC3s) are important host restriction factors that can inhibit viral replication in nonpermissive cells in the absence of Vif (3). APOBEC3G (A3G) inhibits HIV-1 replication most effectively and can be packaged into the virus through binding of HIV-1 Gag and host RNA (4–6). In addition to interfering with reverse transcription and integration of the virus (7, 8), the most important function of A3G is that it can deacetylate C to U in single-stranded DNA replication intermediates. This results in hypermutation of G to A on the double-stranded cDNA of HIV-1, thus leading to a highly efficient interruption of HIV-1 replication (9).

Vif protein expressed in the late stage of infection can antagonize APOBEC3 proteins (10). Vif mediates the degradation of APOBEC3 proteins through the proteasome pathway by recruiting an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (11). Key sites of Vif binding to proteins in the E3 complex and A3G have been widely investigated (12). A conservative motif, 161PPLP164, on Vif is critical for Vif oligomerization and binding to A3G (13). Vif binds directly to Cullin5 (Cul5) via the zinc finger domain and recruits Elongin B (EB)/Elongin C (EC) heterodimers by binding to the BC-box of EC (14, 15). The core-binding factor beta (CBFβ) chaperone is required to ensure the binding of Vif to Cul5 (16). The interaction area between CBFβ and Vif is extensive, and both the N and C termini of Vif are important binding regions (17). Vif mutation analysis showed that W5, W11, W21, W38, L64, I66, E88, and W89, the zinc finger region (residues 102 to 109), and F115 are key sites for the interaction with CBFβ (17–23).

Although antiretroviral therapy effectively reduces the morbidity and mortality of patients infected with HIV, it cannot eliminate HIV and is not curative (24). Therefore, novel treatment strategies to permanently control or eliminate the virus are required. Gene therapy is a promising anti-HIV approach because it may enable continued inhibition of HIV replication after a single therapeutic intervention (25). A dominant negative mutant, applied as an antiviral protein in gene therapy, is an altered viral or cellular protein that can inhibit the normal function of its wild-type counterparts (26). The most widely studied dominant negative mutant is RevM10 (27–29); other transdominant mutant targets include Tat (30), Gag (31, 32), CCR5 coreceptor (33), Vif (34, 35), and HIV-1 integrase interactor 1 protein (36). In the Vif-E3 complex, Vif-CBFβ binding is required to recruit the E3 complex to degrade APOBEC3s. If the Vif-CBFβ interaction is disrupted, Vif-sensitive APOBEC3s are released to inhibit HIV-1 replication. We recently identified a novel small-molecule compound that inhibits HIV-1 by targeting Vif-CBFβ (37). These findings suggest that CBFβ can be used as a target for protecting A3G. Nonfunctional Vif mutants with higher affinity for CBFβ may competitively block Vif-CBFβ binding, thereby interrupting Vif recruitment of the E3 complex.

In this study, we aimed to screen Vif mutants with higher affinity for CBFβ by establishing a yeast surface display (YSD) platform displaying Vif random mutant libraries. Through three rounds of enrichment and single-cell sorting by flow cytometry, we selected some Vif mutants to further evaluate their inhibitory effect on HIV-1.

RESULTS

YSD-based screening of Vif mutants with higher affinity for CBFβ from Vif random mutant libraries.

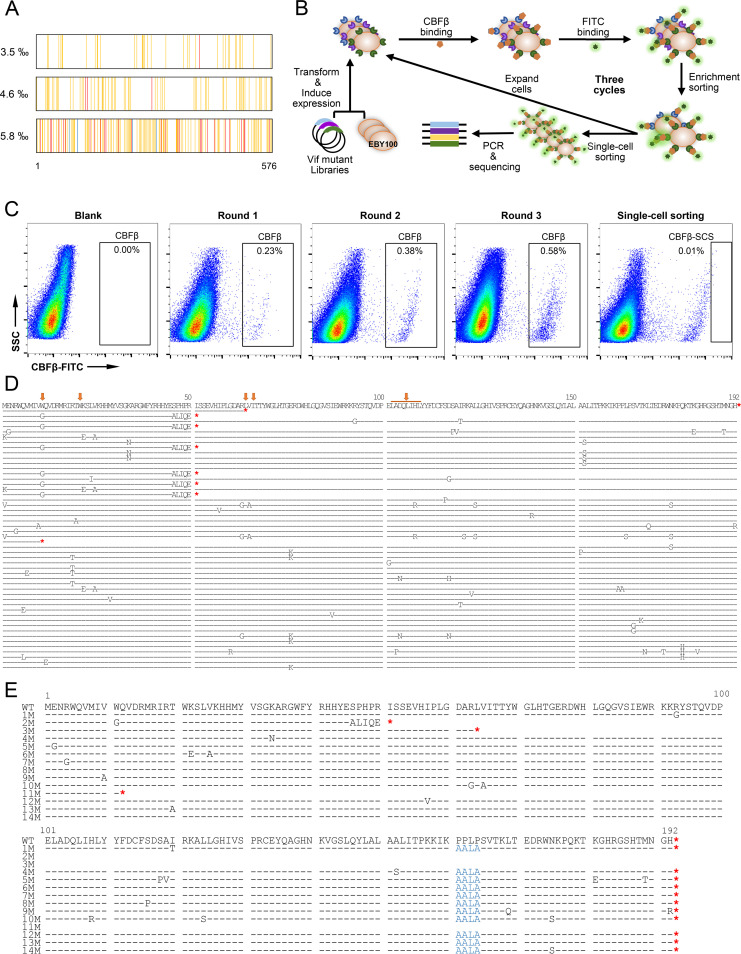

The targets of reported small-molecule inhibitors that antagonize the function of Vif include Vif oligomerization, Vif-EC, and Vif-A3G (38). Recently, we identified the first small-molecule inhibitor targeting the Vif-CBFβ interaction that can inhibit HIV-1 replication (37). Considering that the interaction of Vif-CBFβ is an effective target against HIV-1, we screened Vif dominant negative mutants with high affinity for CBFβ by displaying recombinant proteins on the surface of Saccharomyces cerevisiae; YSD is widely used in the biotechnology and biomedical fields (39). We constructed three Vif random mutant libraries with different mutation frequencies (0.35%, 0.46%, and 0.58%) by PCR random mutagenesis, and the mutations were confirmed to be randomly distributed (Fig. 1A). The three libraries were mixed for display on the surface of EBY100 yeast cells to screen Vif mutants with high affinity for CBFβ. Three rounds of sorting enrichment were performed as shown in Fig. 1B, and the percentage of CBFβ-positive cells gradually increased. Finally, the top 0.01% of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-positive cells was individually sorted into 96-well PCR plates (Fig. 1C). After nested-PCR and sequencing, 50 single-cell sequences were obtained (Fig. 1D). Among the mutations, W11 of Vif has been reported as a key site for the interaction with CBFβ (17). Some mutations, such as K22E, R63G, and V65A, are near known key sites (Vif residues W21, L64, and I66) (19, 21). The zinc finger domain of Vif (102 to 109) is an important binding region of Vif to CBFβ and Cul5 (14, 16), and an H108R mutation is present in this region. These results show that the mutation sites screened by this method were CBFβ high-affinity specific, indicating that the YSD platform can be used to screen engineered Vif proteins. Finally, 14 mutants containing key mutations were selected (Fig. 1E). The selection criteria include the sequences that occurred at high frequency, as well as mutation sites with high frequency; we also wanted to ensure that the mutation sites were dispersed throughout the Vif sequence. In addition, sequences with early termination and partial frameshift were selected.

FIG 1.

Screening of Vif mutants with higher affinity for CBFβ by yeast surface display technology. (A) Sequencing analysis of the distribution of mutation sites of the Vif mutant libraries. A total of 25 clones from each of 3 Vif mutant libraries with different mutation frequencies (0.35%, 0.46%, 0.58%) were sequenced. The nucleotide mutation sites are highlighted (one mutation: orange, two mutations: red, three mutations: blue). (B) Identification strategy based on yeast surface cDNA display. The Vif mutant library was displayed on the surface of yeast cells, incubated with CBFβ protein, and stained with FITC antibody. Cells binding to CBFβ were identified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based screening. (C) Yeast clones displaying Vif protein mutants with high affinity for CBFβ were enriched by three rounds of FACS. Single cells were sorted into 96-well PCR plates, and Vif mutants were sequenced after nested PCR. (D) Sequences of 50 Vif mutants aligned to wild-type Vif (wtVif), amplified from single cells with higher CBFβ affinity. The red asterisks indicate the termination codon in each sequence. The reported key sites in Vif for interaction with CBFβ are marked with orange arrows. (E) Fourteen sequences were selected for further identification. The PPLP motif was mutated to AALA (shown in blue) based on the sequences of the sorted Vif mutants. The red asterisks indicate the termination codon in each sequence.

Identification of Vif mutants with dominant negative character.

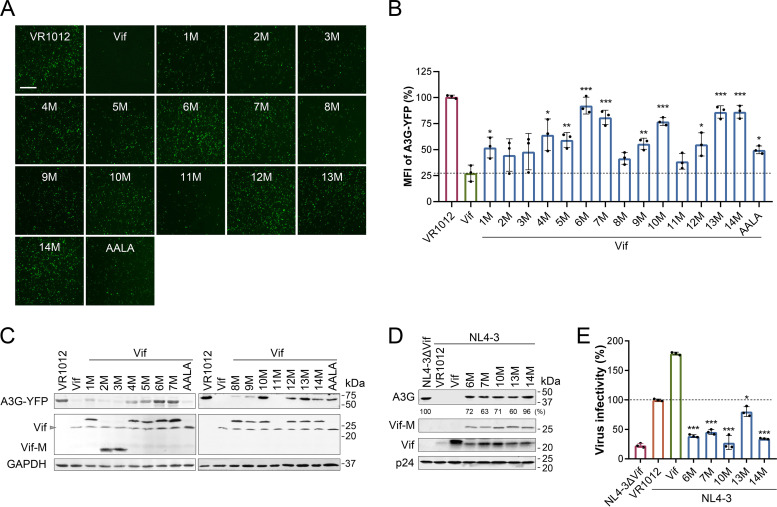

For Vif mutants with high affinity for CBFβ, it was necessary to disrupt their ability to mediate A3G degradation to competitively inhibit the function of wild-type Vif (wtVif). Mutation of PPLP to AALA has been shown to disrupt Vif oligomerization and Vif interaction with A3G (13). Thus, the motif PPLP in Vif mutants was mutated to AALA. To screen the Vif mutants that could competitively inhibit the function of wtVif, the ability of the mutants to rescue A3G was tested. 293T cells were cotransfected with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-fused A3G (A3G-YFP), wtVif, and each Vif mutant or Vif-AALA as a control. The expression of A3G-YFP was observed by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2A) and quantified by flow cytometry (Fig. 2B) at 48 h posttransfection. The results showed that A3G-YFP expression was recovered to different degrees by most mutants when cotransfected with wtVif, including Vif-AALA. Among them, Vif-6M, 7M, 10M, 13M, and 14M showed stronger abilities to rescue A3G (P < 0.001). The results of Western blotting showing expression levels of A3G were consistent with the fluorescence results (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, Western blotting of A3G levels in HIV-1 virions showed that these five mutants increased the incorporation of A3G (Fig. 2D). TZM-bl cells were infected with equal amounts of reverse transcriptase (RT; 2 ng) of the above-mentioned viruses to examine their infectivity (Fig. 2E). Except for Vif-13M (P = 0.017), the other four mutants effectively inhibited viral infection (P < 0.001).

FIG 2.

Vif mutants dominantly interfered with the function of wtVif. (A) A3G-YFP levels detected under a fluorescence microscope. 293T cells were cotransfected with A3G-YFP and wtVif alone or with each Vif mutant. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of A3G-YFP detected by flow cytometry. 293T cells were cotransfected with A3G-YFP and wtVif alone or with each Vif mutant for 48 h. Data were pooled from three independent experiments; mean ± SD. The significance of differences between each group and the Vif group was assessed by Student’s t test. (C) Western blot analysis of A3G recovered by Vif mutants (Vif-M). GAPDH was detected as a loading control. (D) Western blot analysis of A3G packaged into HIV-1 virions in the presence of Vif mutants. A3G-cmyc, pNL4-3, and wtVif alone or with each Vif mutant were cotransfected into 293T cells. Cells transfected with pNL4-3ΔVif were included as a control. After 48 h, viral particles were obtained by ultracentrifugation. p24 was detected as a loading control, and expression of A3G was normalized with p24. Protein expression levels were quantified using Quantity One software. (E) Infectivity of viruses determined by TZM-bl cells. Data were pooled from triplicate experiments; mean ± SD. The significance of differences between each group and the NL4-3 group was assessed by Student’s t test.

Vif mutants rescued the anti-HIV-1 function of A3G and released APOBEC3s in a CBFβ-specific manner.

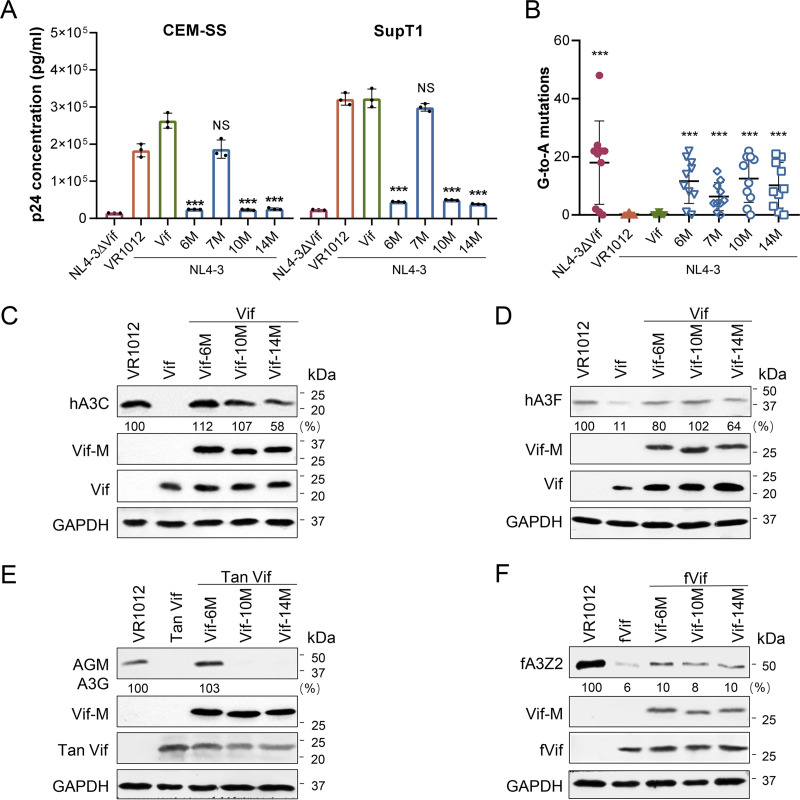

A3G is packaged into HIV particles to induce G-to-A hypermutation in the viral genome of target cells (9). We demonstrated that Vif-6M, 7M, 10M, and 14M enhanced A3G incorporation into HIV-1 particles. We then examined whether the four Vif mutants could recover the G-to-A mutations induced by A3G to inhibit HIV-1 replication and infection. In 293T cells, A3G-cmyc, pNL4-3, and wtVif or each Vif mutant were cotransfected, with pNL4-3ΔVif used as a control. The viral particles in each group were harvested and used to infect permissive T lymphocytes (CEM-SS and SupT1 cells) in equal amounts (4 ng RT). After 48 h of infection, virus production was quantified as the concentration of p24 in the culture supernatant (Fig. 3A). Notably, Vif-7M did not inhibit HIV-1 replication in CEM-SS or SupT1 cells. The results suggest that Vif-6M, 10M, and 14M rescued A3G packaged into virions, and thus inhibited the replication of HIV-1 in T lymphocytes. To verify that the G-to-A mutations were enhanced by the Vif mutants, the genomic DNA of CEM-SS cells was extracted, and an 885-bp fragment of pol was amplified by nested-PCR. The results showed that Vif-6M, 7M, 10M, and 14M significantly enhanced the G-to-A mutations (P < 0.001) compared with that in the NL4-3 group (Fig. 3B), which indicated that these Vif mutants did not inhibit the catalytic activity of A3G. Vif-6M, 10M, and 14M more effectively recovered the G-to-A hypermutation (hypermutation rate, >50%), whereas Vif-7M had a weaker effect (hypermutation rate, 20%) (Table 1). The results indicate that Vif-6M, 10M, and 14M inhibited the degradation of A3G mediated by wtVif and thus rescued the anti-HIV-1 function of A3G.

FIG 3.

Vif mutants rescued the anti-HIV-1 activity of A3G and the level of other APOBEC3s. (A) Replication of viruses packaged in the presence of Vif mutants. A3G, pNL4-3, and wtVif or each Vif mutant or empty vector (VR1012) were cotransfected into 293T cells. Cells transfected with pNL4-3ΔVif were included as a control. After 48 h, cell supernatants containing viruses were collected by centrifugation. CEM-SS and SupT1 cells were infected with equal amounts of virus (4 ng RT). After 48 h, the concentration of produced viruses was detected using a Lenti RT activity ELISA kit. (B) G-to-A mutations induced by A3G in the presence of Vif mutants. At 48 h after viral infection, genomic DNA of CEM-SS cells was extracted. An 885-bp fragment of pol was amplified by nested PCR and ligated into the pGEM-T-easy cloning vector for sequencing (mean ± SD; n = 10). The values on the y axis represent the number of G-to-A mutants in each sequence. The significance of difference between each group and the NL4-3 group was assessed by Student’s t test. (C and D) Western blot analysis of hA3C and hA3F rescued by Vif mutants by interfering with wtVif. 293T cells were cotransfected with hA3C-FLAG (C) or hA3F-cmyc (D), Vif-HA, and Vif mutants. (E) Western blot analysis of AGM A3G saved by Vif mutants from SIVagmTan Vif (Tan Vif)-mediated degradation. 293T cells transfected with AGM A3G-HA, Tan Vif-cmyc, and Vif mutants were cultured for 48 h. (F) Western blot analysis of the effect of Vif mutants on feline immunodeficiency virus Vif (fVif). 293T cells transfected with feline A3Z2-HA (fA3Z2-HA), fVif-cmyc, and Vif mutants were cultured for 48 h. In Western blot analysis, GAPDH was detected as a loading control, and APOBEC3 expression was normalized with GAPDH.

TABLE 1.

G-to-A mutations in the HIV-1 NL4-3 genomea

| Subject | NL4-3 ΔVif |

NL4-3 | NL4-3 +Vif |

NL4-3 +6M |

NL4-3 +7M |

NL4-3 +10M |

NL4-3 +14M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypermutation rate (%)b | 70 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 20 | 60 | 50 |

| No. of mutations | 196 | 14 | 15 | 131 | 89 | 141 | 112 |

| No. of G-to-A mutations | 180 | 2 | 2 | 116 | 63 | 125 | 101 |

| Mutations/sequence | 19.60 | 1.40 | 1.50 | 13.10 | 8.90 | 14.10 | 11.20 |

| Mutations/100 bp | 2.21 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 1.48 | 1.01 | 1.59 | 1.27 |

| G-to-A mutations/100 bp | 2.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.31 | 0.71 | 1.41 | 1.14 |

Each group has 10 unique clones.

Hypermutation rate: no. of hypermutated sequences/no. of total sequences.

The interaction of Vif and CBFβ was necessary for the degradation of APOBEC3s mediated by Vif. Vif mutants that competitively bind CBFβ should release other Vif-sensitive APOBEC3s besides A3G. Therefore, the protective effect of the Vif-6M, 10M, and 14M mutants on other APOBEC3s was examined. 293T cells were transfected with human A3C (hA3C), wtVif, and each Vif mutant and cultured for 48 h before Western blot analysis. The expression of hA3C was rescued by the three Vif mutants to various degrees (Fig. 3C). Similarly, the expression level of human A3F (hA3F) was significantly restored by the three mutants (Fig. 3D). As simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) Vif-mediated APOBEC3 degradation also requires CBFβ, whereas feline immunodeficiency virus Vif-mediated APOBEC3 degradation does not require CBFβ (40, 41), the protective effect of these mutants on African green monkey (AGM) A3G and feline APOBEC3Z2 (fA3Z2) was further examined. Only Vif-6M had a protective effect on AGM A3G (Fig. 3E), and none of the three mutants effectively rescued the expression of fA3Z2 (Fig. 3F). These results indicate that the protective effect of Vif mutants on APOBEC3s was CBFβ specific.

Vif-6M competitively inhibited Vif-CBFβ interaction.

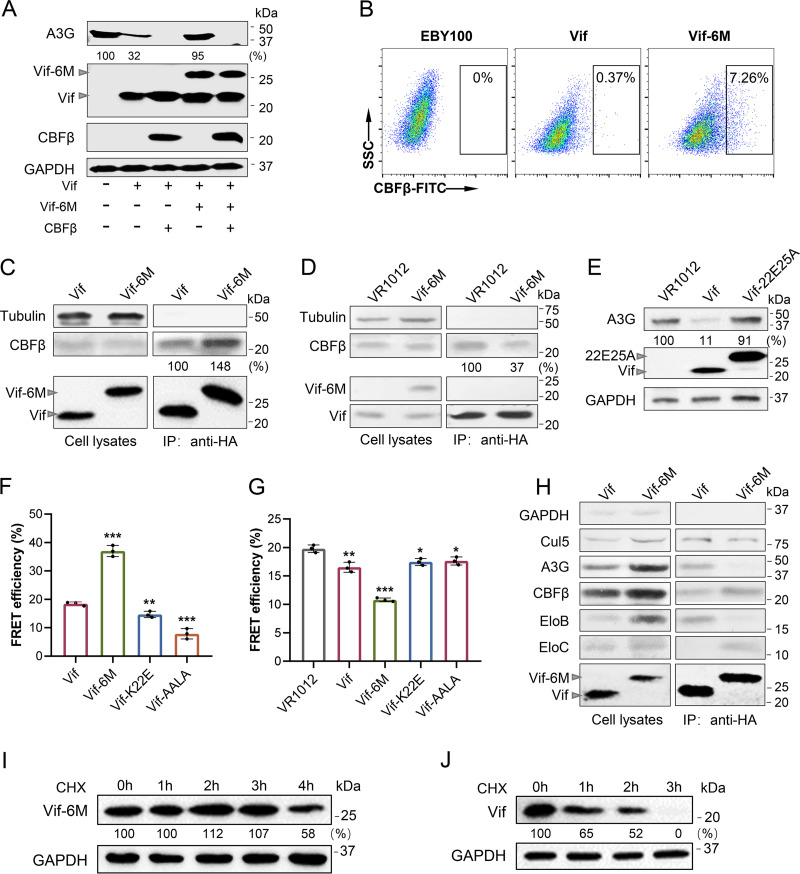

Based on the above-described experimental results, Vif-6M showed good performance in improving A3G packaging into virions and had a cross-protective effect on hA3C, hA3F, and AGM A3G. Therefore, Vif-6M was further evaluated to determine its antiviral effect and mechanism of action. If the interaction of Vif-CBFβ is indeed the target of Vif-6M, overexpression of CBFβ together with Vif and Vif-6M should interrupt the competitive inhibition from Vif-6M. We coexpressed CBFβ with A3G, wtVif, and Vif-6M in 293T cells. As expected, the Western blot analysis showed that overexpression of CBFβ resulted in A3G degradation mediated by wtVif again in the presence of Vif-6M (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

Vif-6M influenced assembly of Vif and E3 complex by competitively binding CBFβ. (A) The ability of Vif-6M to rescue A3G when CBFβ was overexpressed. 293T cells were cotransfected with CBFβ, A3G, wtVif, and Vif-6M and then cultured for 48 h. In Western blot analysis, GAPDH was detected as a loading control, and A3G expression was normalized with GAPDH. (B) The affinity of Vif-6M for CBFβ detected by YSD. Vif or Vif-6M was displayed on the surface of EBY100 cells; the cells were incubated with CBFβ protein for 4 h, stained with FITC-antibody, and monitored by flow cytometry. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis of the affinity of wtVif or Vif-6M with CBFβ. 293T cells were cotransfected with CBFβ-FLAG and Vif-HA or HA-Vif-6M-cmyc. At 48 h posttransfection, cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody-conjugated agarose beads. Expression of CBFβ in the cells and its interaction with Vif or Vif-6M were detected by Western blotting. The CBFβ level was normalized with Vif and Vif-6M. (D) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis of the ability of Vif-6M to block the interaction of Vif-CBFβ. 293T cells were cotransfected with CBFβ-FLAG and Vif-HA with Vif-6M-cmyc or VR1012. Expression of CBFβ in cells and its interaction with Vif were detected by Western blotting. The CBFβ level was normalized with Vif. (E) Western blot analysis of A3G degradation mediated by wtVif and Vif with K22E and V25A mutations. 293T cells were transfected with A3G, wtVif or Vif22E25A for 48 h. GAPDH was detected as a loading control, and the expression of A3G was normalized with GAPDH. Protein expression levels were quantified using Quantity One. (F) FRET efficiency of wtVif, Vif-6M, Vif-K22E, or Vif-AALA to CBFβ. 293T cells were cotransfected with CBFβ-CFP and Vif-YFP or Vif mutant-YFP and then cultured for 48 h. Samples were excited at λmaxCFP (440 nm), and fluorescence emission was detected by scanning fluorometry. FRET efficiency was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Three independent experiments; mean ± SD. The significance of difference between each group and the Vif group was assessed by Student’s t test. (G) The inhibitory effect of wtVif, Vif-6M, Vif-K22E, or Vif-AALA on Vif-CBFβ interaction. 293T cells were cotransfected with Vif-YFP, CBFβ-CFP, and Vif, Vif-6M, Vif-K22E, Vif-AALA, or VR1012 and then cultured for 48 h. Three independent experiments; mean ± SD. The significance of difference between each group and the VR1012 group was assessed by Student’s t test. (H) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis of the interaction between Vif-6M and members of the E3-complex. 293T cells were cotransfected with Cul5-cmyc, A3G-cmyc, CBFβ-cmyc, EB-cmyc, EC-cmyc, and Vif-HA or HA-Vif-6M-cmyc. Expression of proteins in the cells and their interaction with Vif or Vif-6M were detected by Western blotting. (I and J) Western blot analysis of the stability of wtVif and Vif-6M. The 293T cells transfected with Vif-6M (I) or wtVif (J) were treated with 100 μg/mL cycloheximide (CHX) at the indicated time. GAPDH was detected as a loading control, and expression of Vif or Vif-6M was normalized with GAPDH.

The interaction between Vif-6M and CBFβ was examined. Vif-6M and wtVif were displayed on the surface of EBY100 cells. After being incubated with CBFβ protein and stained with an FITC-antibody, EBY100 cells were examined for their affinity with CBFβ by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells displaying Vif-6M combined with CBFβ was approximately 19.6-fold higher than that of cells displaying wtVif (Fig. 4B). Binding of wtVif and Vif-6M to CBFβ was also examined by coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP). Western blotting demonstrated that Vif-6M coimmunoprecipitated with more CBFβ than wtVif (Fig. 4C). Because Vif-6M has a high affinity for CBFβ, it should preferentially bind to CBFβ to block the Vif-CBFβ interaction. Co-IP was performed to confirm this hypothesis. 293T cells were cotransfected with wtVif-HA and CBFβ-FLAG with or without Vif-6M-cmyc. Western blot analysis showed that the expression of Vif-6M reduced the level of CBFβ coimmunoprecipitated with Vif to 37% of that without Vif-6M (Fig. 4D).

Vif-6M contains K22E, V25A, and the PPLP-AALA mutation (Fig. 1E). A previous study showed that Vif containing a K22D mutation cannot mediate the degradation of A3G (42). As both the K22D and K22E mutations were changed from alkaline to acidic amino acids, Vif-6M without the PPLP-AALA mutation may not be able to mediate the degradation of A3G, like the K22D mutant. As expected, Vif containing only the K22E and V25A mutations (Vif22E25A) lost the ability to induce A3G degradation (Fig. 4E). Overexpression of nonfunctional Vif mutants should also inhibit the ability of Vif to interact with CBFβ. To confirm that the dominant negative effect of Vif-6M is dependent on the specific competitive binding of CBFβ, we compared the affinities of wtVif, Vif-6M, Vif-K22E, and Vif-AALA to CBFβ by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay. The FRET efficiency of Vif-6M-YFP and cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)-fused CBFβ (CBFβ-CFP) was approximately twice that of wtVif-YFP and CBFβ-CFP (P = 0.0001) (Fig. 4F). However, the affinities of Vif-K22E and Vif-AALA to CBFβ were lower than that of wtVif. We then detected the inhibitory effect of wtVif, Vif-6M, Vif-K22E, and Vif-AALA on the interaction between Vif and CBFβ by FRET analysis (Fig. 4G). Compared with that of VR1012, the presence of wtVif or each of the three Vif mutants significantly attenuated the FRET efficiency of Vif and CBFβ (P < 0.05), and Vif-6M showed a stronger inhibitory effect (P < 0.001) than wtVif (P < 0.01), Vif-K22E (P < 0.05), and Vif-AALA (P < 0.05). These results indicated that Vif-6M weakened the interaction of CBFβ with wtVif through competitively binding to CBFβ.

The interaction of Vif-6M with other proteins in the E3-complex was also explored. The co-IP results showed that Vif-6M had a higher affinity for CBFβ than wtVif, with stronger binding to EC (Fig. 4H). However, there was no significant change in the binding level of Cul5. Vif-6M containing the mutation of PPLP to AALA was not expected to bind A3G, which is consistent with our results. EB showed almost no interaction with Vif-6M, agreeing with the results for VifΔN and VifΔC which also disrupted the Vif-CBFβ interaction (43). In summary, Vif-6M only bound to EC, CBFβ, and Cul5 but did not recruit EB and A3G to form a complete E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. This result indicates that binding of Vif-6M to CBFβ disrupts the assembly of the E3 complex.

CBFβ has been reported to stabilize Vif protein and prolong its half-life by binding to Vif (44). CBFβ may also stabilize Vif by disrupting mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2)-mediated degradation of Vif (44, 45). Thus, if Vif-6M has a high affinity for CBFβ, its stability in the cytoplasm should be better than that of wtVif. We detected the stability of wtVif and Vif-6M in a cycloheximide (CHX) pulse-chase assay. The level of Vif-6M did not decrease for 3 h after CHX addition and decreased to 58% at 4 h (Fig. 4I). However, the expression of wtVif decreased to 65% at 1 h after treatment with CHX (Fig. 4J). These results suggest that increasing the affinity of Vif for CBFβ can improve the stability of Vif.

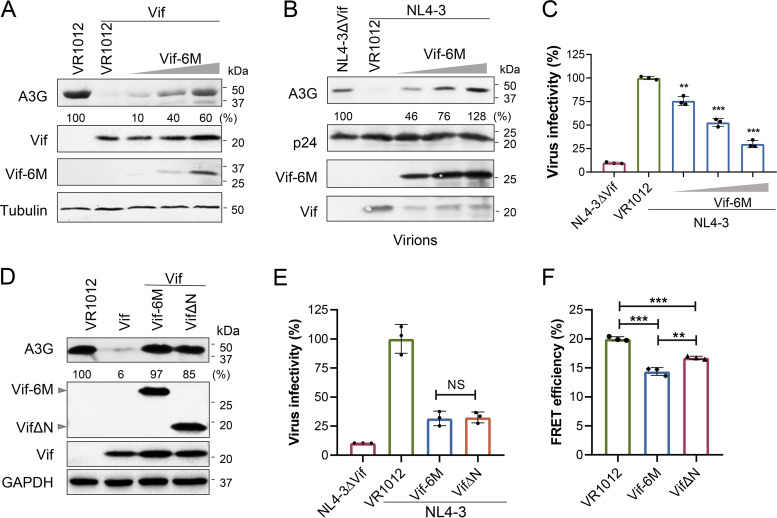

Vif-6M provided dose-dependent protection from HIV-1 Vif-mediated degradation of A3G.

The ability of Vif-6M to interfere with wtVif was detected with the gradient expression of Vif-6M. A3G, wtVif, and Vif-6M (200 ng, 400 ng, or 800 ng) were cotransfected into 293T cells. Vif-6M exerted a dose-dependent ability to rescue A3G in the presence of wtVif (Fig. 5A). We also examined the expression of A3G in virions, when we cotransfected A3G with pNL4-3 and Vif-6M into 293T cells. The Western blotting results showed that Vif-6M restored A3G in viral particles in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). The incorporation of A3G should inhibit the infection of HIV-1, and the infectivity of the above-described virus determined in TZM-bl cells was indeed related to the expression level of A3G in virions (Fig. 5C).

FIG 5.

Vif-6M protected A3G from HIV-1 Vif-mediated degradation as efficiently as VifΔN in a dose-dependent manner. (A) The protection of Vif-6M on A3G in the presence of wtVif. 293T cells were cotransfected with A3G-cmyc and Vif-HA alone or with Vif-6M (200, 400, or 800 ng). After 48 h, the cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting. (B) Western blot analysis of A3G restored by Vif-6M in the presence of NL4-3. Tubulin and p24 were detected as loading controls. A3G expression was normalized with tubulin or p24. (C) Vif-6M inhibited the infection of viruses in a dose-dependent manner. 293T cells were cotransfected with A3G, pNL4-3, and Vif-6M (200, 400, or 800 ng). Cells transfected with pNL4-3ΔVif were included as a control. After 48 h, the cell supernatant containing virus was collected by centrifugation. Viral infectivity was determined using TZM-bl cells. Triplicate experiments; mean ± SD. The significance of difference between each group and the NL4-3 group was assessed by Student’s t test. (D) Western blot analysis of the recovery of A3G by Vif-6M or VifΔN. 293T cells were cotransfected by A3G, wtVif, and Vif-6M or VifΔN and then cultured for 48 h. GAPDH was detected as a loading control, and the expression of A3G was normalized with GAPDH. (E) The ability of Vif-6M and VifΔN to inhibit viral infection. A3G, pNL4-3, and VR1012, Vif-6M or VifΔN were cotransfected into 293T cells. Cells transfected with pNL4-3ΔVif were included as a control. After 48 h, the infectivity was detected by TZM-bl cells. Triplicate experiments; mean ± SD. (F) The FRET efficiency of Vif-CBFβ with the expression of Vif-6M or VifΔN. 293T cells were cotransfected with Vif-YFP, CBFβ-CFP, and Vif-6M or VifΔN and then cultured for 48 h. Samples were excited at λmaxCFP (440 nm), and the fluorescence emission was detected by scanning fluorometry. Three independent experiments; mean ± SD.

The only two Vif dominant negative mutants reported to act on Vif-CBFβ are VifΔC and VifΔN (43). Thus, we compared the inhibition effect of Vif-6M and VifΔN, which were both found to recover A3G (Fig. 5D) and reduce viral infectivity equally (Fig. 5E). We also performed the FRET assay to compare the ability of these mutants to weaken the Vif-CBFβ interaction (Fig. 5F) and found that the inhibitory effect of Vif-6M was stronger than that of VifΔN (P = 0.0049).

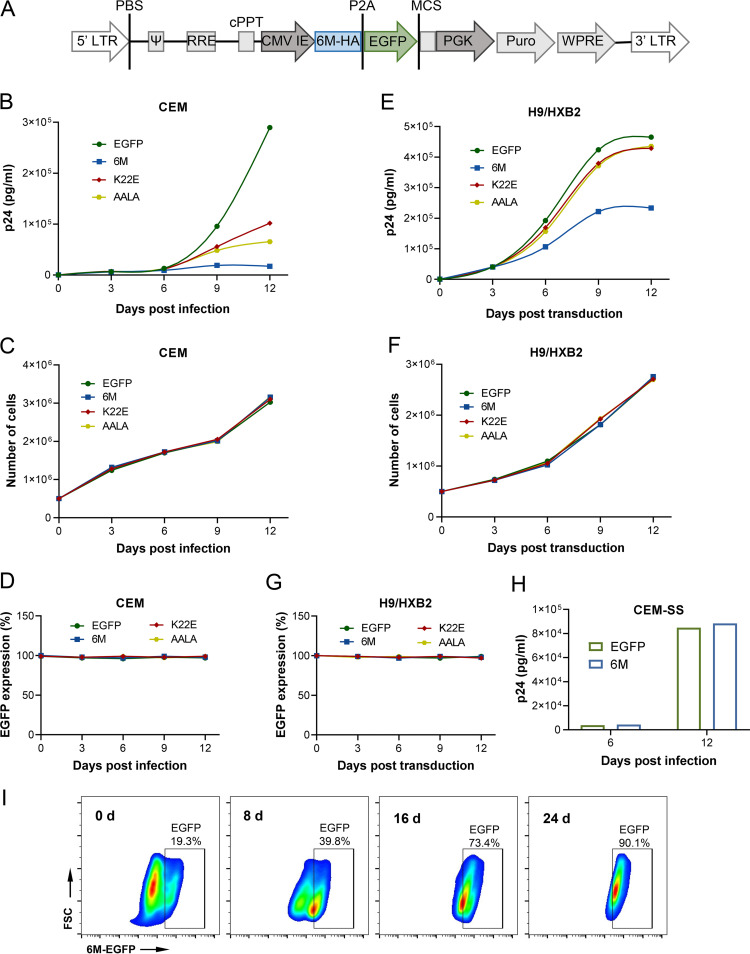

Transduction of Vif-6M inhibited HIV-1 replication in T lymphocytes.

To explore whether Vif-6M has the potential to be applied as a dominant negative inhibitor in gene therapy, Vif-6M was transduced into T lymphocytes to detect its inhibitory effect on HIV-1 replication. Nonfunctional Vif mutants Vif-K22E and Vif-AALA were included as controls. Enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP) was fused to the C terminus of Vif-6M-HA, Vif-K22E-HA, and Vif-AALA-HA, and the P2A peptide was used to splice the fragments after translation. The fragments of Vif mutants-HA-EGFP were then inserted into the HIV-1-based pLVX-puro vector (Fig. 6A). Pseudoviruses were produced by transfection of Vif mutants-HA-EGFP-pLVX-puro, psPAX2, and VSV-G into 293T cells, with EGFP-pLVX-puro used as a control. T lymphocytes (CEM, H9/HXB2, and CEM-SS cells) stably expressing the Vif mutants were obtained by puromycin selection and flow cytometry sorting. CEM and H9 cells are nonpermissive cells that express A3G and restrict HIV-1ΔVif viral replication; CEM-SS cells are permissive cells that no longer restrict HIV-1ΔVif replication due to the defective expression of A3G (37, 46). Sorted CEM cells (CEM-6M, CEM-K22E, CEM-AALA, and CEM-EGFP) were infected with HIV-1 NL4-3 and cultured. Viral replication was detected by measuring the concentration of p24 in the culture supernatant at different days postinfection, whereas EGFP expression was monitored by flow cytometry (Fig. 6B and D). According to cell counting, the cell growth levels in the four groups were comparable (Fig. 6C). The HIV-1 replication level in CEM cells expressing EGFP increased exponentially from day 6, and stable expression of Vif mutants inhibited NL4-3 replication (Fig. 6B). Compared to Vif-K22E and Vif-AALA, Vif-6M strongly controlled the replication of HIV-1 at baseline and up to 12 days postinfection.

FIG 6.

Transduction of Vif-6M inhibited long-term HIV-1 replication in T lymphocytes. (A) Schematic representation of the HIV-1-based 6M-HA-EGFP-pLVX-puro lentiviral vector in the proviral genome form. A P2A peptide cleavage site is added after the C-terminal HA-tag of the Vif mutants. (B) Vif-6M transduction into CEM cells inhibited HIV-1 replication. Vif-6M, EGFP, Vif-K22E, and Vif-AALA were transduced into CEM cells. After infection with HIV-1 NL4-3, the virus production was monitored at the indicated time points using a p24 ELISA kit. (C) Growth curve of CEM cells over time. (D) EGFP expression was detected by flow cytometry. (E) Vif-6M transduction into H9/HXB2 cells inhibited HIV-1 replication. Similarly, Vif-6M, EGFP, Vif-K22E, and Vif-AALA were transduced into H9/HXB2 cells. Virus production was monitored at the indicated time points using a p24 ELISA kit. (F) Growth curve of H9/HXB2 cells over time. (G) EGFP expression was detected by flow cytometry. (H) The effect on HIV-1 replication in CEM-SS cells after transduction of Vif-6M. Virus production was monitored at the indicated time points using a p24 ELISA kit. (I) Survival advantage of CEM-6M cells. The CEM cells stably expressing Vif-6M (20%) were mixed with CEM cells (80%) and then infected by NL4-3. The proportion of CEM-6M cells was monitored by flow cytometry for 24 days.

The effect of Vif-6M on viral replication in T lymphocytes already infected with HIV-1 was also investigated. In H9/HXB2 cells chronically infected with HIV-1 HXB2, virus production was monitored after flow cytometry sorting for 12 days (Fig. 6E). During this period, EGFP expression and the cell growth levels between the four groups were similar (Fig. 6G and F). The HIV-1 replication in H9/HXB2 cells in the Vif-6M group was maintained in a slowly increasing state compared to that in the EGFP group (Fig. 6E), indicating that transduction of Vif-6M inhibited viral replication in T lymphocytes already infected with HIV-1. However, the inhibitory ability of Vif-K22E and Vif-AALA was weak (Fig. 6E). These results showed that compared to the nonfunctional Vif mutants, Vif-6M exhibited a stronger inhibitory effect on HIV-1 replication, suggesting that Vif-6M acts in a competitive inhibitory manner. Also, Vif-6M did not affect the replication of HIV-1 in the permissive cell line CEM-SS (Fig. 6H), indicating that the antiviral function of Vif-6M was APOBEC3 specific.

When infected with HIV-1, T lymphocytes expressing Vif-6M may have a survival advantage compared with cells without HIV-1 resistance. This prediction was examined by mixing CEM cells with CEM-6M cells; the initial proportion of CEM-6M cells was approximately 20% (Fig. 6I). After infection with HIV-1 NL4-3, the proportion of CEM-6M was analyzed by flow cytometry for 24 days. The percentage of CEM cells expressing Vif-6M gradually increased over time. At 24 days postinfection, 90% of cells were CEM-6M, showing that the anti-HIV-1 activity conferred by transduction of Vif-6M contributed to the survival of T lymphocytes.

DISCUSSION

CBFβ was previously found to be a key molecular chaperone for Vif to mediate the degradation of APOBEC3s (16, 22, 47). Subsequently, the crystal structure of the Vif-CBFβ-Cul5-EB-EC complex was resolved (17); however, A3G was not included in the complex. We recently identified a small-compound inhibitor targeting Vif-CBFβ through structure-based virtual screening (37). The antiviral activity of this inhibitor (CV-3) suggested that blocking the interaction of Vif-CBFβ effectively restored APOBEC3s and inhibited the replication of HIV-1. However, the 50% inhibitory concentration (8 μM) of CV-3 was high, and thus we screened for other inhibitors with potential applications in gene therapy against this target. We screened Vif mutants with high affinity for CBFβ utilizing a yeast surface display assay and mutated PPLP to AALA to eliminate their ability to degrade A3G. We identified Vif dominant negative mutants that competitively bound to CBFβ and inhibited the function of wtVif.

Two types of Vif-based dominant negative mutants have been reported. One is a natural mutant of Vif, named F12-Vif, containing 14 amino acid substitutions; this protein can inhibit the replication and spread of HIV-1 in T lymphocytes, but its mechanism of action is unclear (34). The other is a series of inactivated Vif mutants designed based on Vif functional sites, including the Cul5-binding motif, BC box, and PPLP motif (35). VifΔC (Δ144-149, BC box-deleted) and VifΔN (Δ155-164, PPLP-deleted) in this series of inactivated Vif mutants exhibited dominant negative characteristics by competitively binding to CBFβ, suggesting that CBFβ is critical in anti-HIV-1 therapy (43). Compared with the reported Vif dominant negative mutants, more unknown key sites in Vif can be identified by displaying the Vif mutant library on the surface of yeast cells. In the sequences of mutants obtained from sorted single cells, some mutations were consistent with the location of key residues binding to CBFβ reported previously (14, 16, 17, 19, 21), demonstrating that the screening method is valid. Moreover, some unreported mutations, such as K34N (Vif-4M), A152S (Vif-4M), and N175S (Vif-10M and Vif-14M) occurred at a higher frequency. The protective effect of Vif-4M, Vif-10M, and Vif-14M on A3G showed that our platform can be applied to screen for other dominant negative mutants against different targets.

Among the three Vif mutants with anti-HIV-1 effects (Fig. 3), Vif-10M contains more mutations, including R63G, V65A, H108R, L124S, and N175S. Among them, three mutations (R63G, V65A, and H108R) are associated with known key sites (L64, I66, and the zinc finger domain of Vif) for the interaction between Vif and CBFβ. Vif-14M contains only one mutation site, N175S, which was also observed in Vif-10M. Compared with wtVif, the only two mutation sites of Vif-6M, K22E and V25A, are found in its N terminus in a highly conserved 21WKSLVK26 motif in HIV-1 Vif (22WHSLIK27 in HIV-2 and SIVmac239 and 23WKIVK28 in SIVagmTan) (42). This may explain why Vif-6M restored AGM A3G, whereas Vif-10M and 14M did not (Fig. 3E). Moreover, it was previously reported that the ΔSLV mutation prevents Vif from inducing A3G degradation (42), possibly because mutation of ΔSLV causes Vif to lose its ability to bind CBFβ. That study also showed that Vif containing the K22D mutation cannot mediate the degradation of A3G. In this study, we showed that Vif with K22E and V25A mutations lost the ability to induce A3G degradation. By analyzing the Vif-CBFβ interaction in the crystal structure (PDB ID: 4N9F), we found that K22 in Vif did not directly interact with CBFβ, suggesting that the mutations K22E and V25A may alter the conformation of Vif and increase its affinity for CBFβ. The high affinity of Vif-6M for CBFβ indicates that 21WKSLVK26 may be related to the interaction of Vif-CBFβ, but this hypothesis needs to be further investigated. However, because there is no crystal structure for the A3G interaction with Vif and other E3 complex members, it is unclear how the K22 mutation prevents Vif from binding to A3G.

Vif-6M showed better stability in 293T cells than wtVif (Fig. 4I and J). Initially, we only detected their stability because CBFβ can stabilize Vif protein and prolong its half-life by binding to Vif or disrupting MDM2-mediated degradation of Vif (44, 45). Subsequently, the co-IP result showed that Vif-6M fails to recruit EB and A3G to assemble a complete E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (Fig. 4H). Vif itself can also be degraded by the proteasome pathway together with the APOBEC3 family proteins. Therefore, the increased stability of Vif-6M may also be due to its inability to form the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, meaning that it is more resistant to degradation.

Compared to previous studies, Vif-6M strongly inhibited HIV-1 replication and showed good stability. Transduction of Vif-6M inhibited the replication of newly infected HIV-1 and HIV-1 replication in the chronically infected cell line H9/HXB2. Although stable expression of Vif-6M did not affect cell growth, the impact of Vif-6M on hijacking CBFβ in vivo must be further evaluated. In summary, our screening identified an effective dominant negative Vif mutant, Vif-6M, through a new target of Vif-CBFβ interaction, which may be used as an antiviral protein for gene therapy. Subsequent optimization can be achieved by continued screening for mutation sites based on Vif-6M.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The infectious molecular clone NL4-3 and the Vif mutant NL4-3ΔVif construct, as well as those of VR1012, A3G-HA, A3G-YFP, A3C-HA, A3F-V5, fA3Z3-HA, AGM A3G, HIV-1 Vif-cmyc, Vif-HA, feline immunodeficiency virus Vif-cmyc, TanVif-cmyc, Cullin5-cmyc, and ElonginB/C-cmyc, have been previously described (48). Construction of CBFβ-cmyc, CBFβ-6×His, Vif-pCTcon2, CBFβ-CFP, and Vif-YFP were previously described (37). Vif-AALA, Vif-K22E, and Vif22E25A were constructed by site-directed PCR mutagenesis. The FLAG-epitope tag sequence was added to the C terminus of CBFβ by PCR. N-terminal YFP-fused Vif-mutants were constructed by overlapping PCR and then cloned into the EcoRI and XbaI sites of VR1012. Vif-6M was inserted into the NheI and BamHI sites of pCTcon2 (Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA). Vif mutant libraries were generated using a Diversify PCR random mutagenesis kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA), and the mutation rates were 0.38%, 0.46%, and 0.58% for sorting. Fragments of HA-Vif mutant-cmyc were obtained by PCR and then cloned into the SalI and BglII sites of VR1012 for subsequent validation. The hemagglutinin (HA) tag and linker region at the N terminus of Vif-6M-cmyc were removed for co-IP experiments. EGFP or Vif-mutant-HA-EGFP fragments were inserted into the BamHI and XbaI sites of pLVX-puro (Clontech).

Cells, antibodies, and protein.

HEK293T cells were purchased from the American Tissue Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). HeLa cell-derived indicator TZM-bl cells and the human T cell lines H9, CEM, and CEM-SS were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program (NIH-ARP), Division of AIDS. HEK293T and TZM-bl cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The SupT1 cell line was gifted by Shan Cen (Department of Virology, Institute of Medicinal Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Medical Science). The chronically infected cell line H9/HXB2 has been described previously (49). Briefly, H9 cells were infected with an infectious HIV-1 clone (HXB2Neo) which contained the neomycin resistance gene in place of the nef open reading frame and were selected by G418. T cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain EBY100 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was cultured in yeast extract peptone dextrose medium at 30°C with shaking at 270 rpm.

The antibodies used in this study were described previously (37): anti-HA antibody (Covance, Emeryville, CA, USA), anti-myc antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and anti-tubulin antibody (Covance). Pr55Gag and p24 were detected with a monoclonal anti-HIV capsid antibody generated by an HIV-1 p24 hybridoma (NIH-ARP). The rabbit monoclonal antibody against CBFβ, goat anti-rabbit IgG(H+L) (fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]), and goat anti-mouse IgG(H+L) (FITC) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) were used for flow cytometry analysis.

CBFβ protein was expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21. Cells were grown in Luria-Bertani medium containing 100 mg/L ampicillin at 37°C until the optical density reached 0.8, and protein expression was induced by adding 1 mM isopropyl-beta-d-thiogalactopyranoside and incubating the cells at 16°C overnight. The cells were harvested, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), sonicated, and clarified by centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant was then applied to a nickel affinity column (Invitrogen), and the fraction containing CBFβ was pooled and concentrated in PBS.

Yeast surface display.

The Vif random mutation library was constructed according to the instructions of the Diversify PCR random mutagenesis kit (Clontech), and three Vif libraries with mutation frequencies of 0.38%, 0.46%, and 0.58% were constructed. The Vif mutation library was transformed into EBY100 cells; transformants were selected on SDCAA medium (containing 2% dextrose, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, and 0.5% Casamino Acids) and then confirmed by PCR. Selected transformants were inoculated into 1 mL SDCAA for overnight incubation at 30°C; to induce the expression of Vif mutants on the yeast surface, the yeast cells were reinoculated in SGCAA (SDCAA containing 2% galactose in place of dextrose) at an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0 and grown at 20°C for 36 h. Induction was verified by immunolabeling with HA monoclonal antibody. Approximately 1 × 107 induced cells in 200 μL PBS were incubated with 200 μg CBFβ protein for 4 h at 4°C. The cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with 200 μL of 1:500 diluted CBFβ antibody for 40 min at 4°C. These cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with 200 μL of 1:100 diluted goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to FITC antibody for 40 min at 4°C. After washing twice with PBS, the cells were sorted by flow cytometry on an MoFlo XDP instrument (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and analyzed by flow cytometry with a C6 device (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Transfection and virus purification.

DNA transfections were carried out using jetPRIME (Polyplus-transfection, Illkirch, France) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Virus in the cell culture supernatants was precleared of cellular debris by centrifugation. Viral particles were concentrated through a 20% sucrose cushion by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. For immunoblotting, the viral pellets were resuspended in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer.

Immunoblot analysis.

Cells and viruses were harvested at 48 h after transfection and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. The samples were boiled for 10 min, subjected to standard SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for Western blotting. The secondary antibodies were alkaline phosphatase or horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA). Staining was carried out with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate and nitroblue tetrazolium solutions or chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Protein expression levels were quantified using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Viral infectivity assay.

Viral supernatants were normalized with the level of RT activity using a Lenti RT activity kit (Cavidi, Uppsala, Sweden). Virus samples containing an equal amount of RT were mixed with DEAE (diethylaminoethyl)-dextran (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at a final concentration of 20 μg/mL and then incubated with 1 × 104 TZM-bl indicator cells per well in 96-well plates. Infectivity was measured 48 h after infection by performing a luciferase assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

HIV-1 replication in human T cells and hypermutation analysis.

In 293T cells, A3G, pNL4-3, and wtVif or the Vif mutants were cotransfected, with pNL4-3ΔVif used as a control. After 48 h, the virus-containing supernatants were filtered through a 0.45-μm filter and treated with DpnI (20 U/mL) at 37°C for 1 h. The viral stocks were normalized for RT activity prior to infection. After 3 h of incubation, the cells (5 × 105) were washed three times with PBS. After 48 h, HIV-1 replication levels were monitored using the Lenti RT activity kit. Viral infectivity was detected as described above.

Hypermutation analysis was performed as previously described (37). Briefly, genomic DNA was isolated from CEM-SS cells, and a DNA fragment of pol was amplified by nested PCR. The fragments were cloned into the pGEM-T-easy vector (Promega), and the sequencing results of the clones were analyzed using Hypermut 2.0 (https://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/HYPERMUT/hypermut.html).

FRET assay.

FRET experiments to detect protein-protein interactions were performed as described previously with some modifications (50). Briefly, Vif-YFP and CBFβ-CFP were cotransfected into 293T cells, which were then cultured for 48 h. The cells were harvested and resuspended in PBS. Fluorescence signals were detected by placing the samples in a 1.5-mL quartz microcuvette with a magnetic stir bar and using an LS-55 spectrofluorometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). In each FRET experiment, fluorescence emission spectra were recorded from four separate samples: (i) buffer-only blank, (ii) sample containing only CBFβ-CFP, (iii) sample containing only Vif-YFP, and (iv) sample containing both CBFβ-CFP and Vif-YFP fluorescence emission. FRET between CFP- and YFP-tagged receptors was detected by following a procedure that removed the background signal, CFP emission (“bleed-through”), and direct YFP emission (“cross talk”) from the CFP-tagged and YFP-tagged sample emission spectrum as previously described (50).

The “apparent FRET efficiency” was calculated as follows (50):

where Eapp is the apparent FRET efficiency, FDAFRET is the fluorescence intensity attributable to FRET, and FDAA is the fluorescence intensity of the acceptor when excited at λmaxYFP.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

Transfected 293T cells were washed with cold PBS, disrupted in lysis buffer (containing 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, with 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets) at 4°C for 40 min, and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min. The precleared cell lysates were then mixed with anti-HA antibody-conjugated agarose beads (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and incubated at 4°C for 3 h. The samples were washed three times with washing buffer (containing 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, with 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.05% Tween 20). The beads were eluted with elution buffer (0.1 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.0), and the eluates were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting.

Transduction of Vif-6M.

293T cells were cotransfected with 6M-HA-EGFP-pLVX or pLVX-EGFP, VSVG, and psPAX2 (Addgene) and cultured for 48 h. Pseudovirus in the cell culture supernatants was purified by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. CEM, CEM-SS, and H9/HXB2 cells were infected by the pseudovirus with 1 ng/μL Polybrene for 24 h. The cells were washed three times with PBS to remove the virus and then cultured with puromycin for 7 days to kill uninfected cells. Next, 1 × 105 EGFP-positive cells were sorted by flow cytometry. After culturing for 24 h, the cells were infected with HIV-1 NL4-3, or HIV-1 NL4-3ΔVif, the p24 level was monitored using a p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (PerkinElmer), and EGFP level in the cells was monitored by flow cytometry C6 (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis.

The experimental data were statistically analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t test (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA), and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). Error bars are represented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Shan Cen for the gift of the human T cell lines. This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFC2301500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82002138 and 82150202), the Science and Technology Development Project of Jilin Province (20210508041RQ), the Science and Technology Research Projects of the Education Department of Jilin Province (JJKH20211063KJ), and the Program for Jilin University Science and Technology Innovative Research Team (2017TD-05).

We declare that no competing interest exists.

Contributor Information

Jiaxin Wu, Email: wujiaxin@jlu.edu.cn.

Xianghui Yu, Email: xianghui@jlu.edu.cn.

Viviana Simon, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

REFERENCES

- 1.Li G, De Clercq E. 2016. HIV genome-wide protein associations: a review of 30 years of research. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 80:679–731. 10.1128/MMBR.00065-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gabuzda DH, Lawrence K, Langhoff E, Terwilliger E, Dorfman T, Haseltine WA, Sodroski J. 1992. Role of Vif in replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Virol 66:6489–6495. 10.1128/JVI.66.11.6489-6495.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheehy AM, Gaddis NC, Choi JD, Malim MH. 2002. Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature 418:646–650. 10.1038/nature00939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alce TM, Popik W. 2004. APOBEC3G is incorporated into virus-like particles by a direct interaction with HIV-1 Gag nucleocapsid protein. J Biol Chem 279:34083–34086. 10.1074/jbc.C400235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan MA, Goila-Gaur R, Opi S, Miyagi E, Takeuchi H, Kao S, Strebel K. 2007. Analysis of the contribution of cellular and viral RNA to the packaging of APOBEC3G into HIV-1 virions. Retrovirology 4:48. 10.1186/1742-4690-4-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apolonia L, Schulz R, Curk T, Rocha P, Swanson CM, Schaller T, Ule J, Malim MH. 2015. Promiscuous RNA binding ensures effective encapsidation of APOBEC3 proteins by HIV-1. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004609. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwatani Y, Chan DS, Wang F, Stewart-Maynard K, Sugiura W, Gronenborn AM, Rouzina I, Williams MC, Musier-Forsyth K, Levin JG. 2007. Deaminase-independent inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcription by APOBEC3G. Nucleic Acids Res 35:7096–7108. 10.1093/nar/gkm750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mbisa JL, Bu W, Pathak VK. 2010. APOBEC3F and APOBEC3G inhibit HIV-1 DNA integration by different mechanisms. J Virol 84:5250–5259. 10.1128/JVI.02358-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lecossier D, Bouchonnet F, Clavel F, Hance AJ. 2003. Hypermutation of HIV-1 DNA in the absence of the Vif protein. Science 300:1112. 10.1126/science.1083338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stopak K, Noronha CD, Yonemoto W, Greene WC. 2003. HIV-1 Vif blocks the antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by impairing both its translation and intracellular stability. Mol Cell 12:591–601. 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu X, Yu Y, Liu B, Luo K, Kong W, Mao P, Yu XF. 2003. Induction of APOBEC3G ubiquitination and degradation by an HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-SCF complex. Science 302:1056–1060. 10.1126/science.1089591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barraud P, Paillart JC, Marquet R, Tisné C. 2008. Advances in the structural understanding of Vif proteins. Curr HIV Res 6:91–99. 10.2174/157016208783885056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donahue JP, Vetter ML, Mukhtar NA, D’Aquila RT. 2008. The HIV-1 Vif PPLP motif is necessary for human APOBEC3G binding and degradation. Virology 377:49–53. 10.1016/j.virol.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao Z, Ehrlich E, Yu Y, Luo K, Wang T, Tian C, Yu XF. 2006. Assembly of HIV-1 Vif-Cul5 E3 ubiquitin ligase through a novel zinc-binding domain-stabilized hydrophobic interface in Vif. Virology 349:290–299. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergeron JR, Huthoff H, Veselkov DA, Beavil RL, Simpson PJ, Matthews SJ, Malim MH, Sanderson MR. 2010. The SOCS-box of HIV-1 Vif interacts with ElonginBC by induced-folding to recruit its Cul5-containing ubiquitin ligase complex. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000925. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fribourgh JL, Nguyen HC, Wolfe LS, Dewitt DC, Wenyan Z, Xiao-Fang Y, Elizabeth R, Yong X. 2014. Core binding factor beta plays a critical role by facilitating the assembly of the Vif-cullin 5 E3 ubiquitin ligase. J Virol 88:3309–3319. 10.1128/JVI.03824-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo Y, Dong L, Qiu X, Wang Y, Zhang B, Liu H, Yu Y, Zang Y, Yang M, Huang Z. 2014. Structural basis for hijacking CBF-beta and CUL5 E3 ligase complex by HIV-1 Vif. Nature 505:229–233. 10.1038/nature12884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsui Y, Shindo K, Nagata K, Io K, Tada K, Iwai F, Kobayashi M, Kadowaki N, Harris RS, Takaori-Kondo A. 2014. Defining HIV-1 Vif residues that interact with CBFβ by site-directed mutagenesis. Virology 449:82–87. 10.1016/j.virol.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou X, Han X, Zhao K, Du J, Evans SL, Wang H, Li P, Zheng W, Rui Y, Kang J, Yu XF. 2014. Dispersed and conserved hydrophobic residues of HIV-1 Vif are essential for CBFβ recruitment and A3G suppression. J Virol 88:2555–2563. 10.1128/JVI.03604-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desimmie BA, Smith JL, Matsuo H, Hu WS, Pathak VK. 2017. Identification of a tripartite interaction between the N-terminus of HIV-1 Vif and CBFβ that is critical for Vif function. Retrovirology 14:19. 10.1186/s12977-017-0346-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim DY, Kwon E, Hartley PD, Crosby DC, Mann S, Krogan NJ, Gross JD. 2013. CBFβ stabilizes HIV Vif to counteract APOBEC3 at the expense of RUNX1 target gene expression. Mol Cell 49:632–644. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang W, Du J, Evans SL, Yu Y, Yu XF. 2011. T-cell differentiation factor CBF-β regulates HIV-1 Vif-mediated evasion of host restriction. Nature 481:376–379. 10.1038/nature10718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hultquist JF, McDougle RM, Anderson BD, Harris RS. 2012. HIV type 1 viral infectivity factor and the RUNX transcription factors interact with core binding factor beta on genetically distinct surfaces. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 28:1543–1551. 10.1089/AID.2012.0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Looney D, Ma A, Johns S. 2015. HIV therapy: the state of art. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 389:1–29. 10.1007/82_2015_440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrera-Carrillo E, Berkhout B. 2014. Potential mechanisms for cell-based gene therapy to treat HIV/AIDS. Expert Opin Ther Targets 19:245–263. 10.1517/14728222.2014.980236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falkenhagen A, Joshi S. 2018. Genetic strategies for HIV treatment and prevention. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 13:514–533. 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morgan RA, Walker R, Carter CS, Natarajan V, Tavel JA, Bechtel C, Herpin B, Muul L, Zheng Z, Jagannatha S, Bunnell BA, Fellowes V, Metcalf JA, Stevens R, Baseler M, Leitman SF, Read EJ, Blaese RM, Lane HC. 2005. Preferential survival of CD4+ T lymphocytes engineered with anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) genes in HIV-infected individuals. Hum Gene Ther 16:1065–1074. 10.1089/hum.2005.16.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malim MH, Böhnlein S, Hauber J, Cullen BR. 1989. Functional dissection of the HIV-1 Rev trans-activator: derivation of a trans-dominant repressor of Rev function. Cell 58:205–214. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90416-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malim M, Freimuth W, Liu J, Boyle T, Lyerly H, Cullen B, Nabel G. 1992. Stable expression of transdominant Rev protein in human T cells inhibits human immunodeficiency virus replication. J Exp Med 176:1197–1201. 10.1084/jem.176.4.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Apolloni A, Lin MH, Sivakumaran H, Li D, Kershaw MH, Harrich D. 2013. A mutant Tat protein provides strong protection from HIV-1 infection in human CD4+ T cells. Hum Gene Ther 24:270–282. 10.1089/hum.2012.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SK, Harris J, Swanstrom R. 2009. A strongly transdominant mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene defines an Achilles heel in the virus life cycle. J Virol 83:8536–8543. 10.1128/JVI.00317-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson-Daniels J, Singh PK, Sowd GA, Li W, Engelman AN, Aiken C. 2019. Dominant negative MA-CA fusion protein is incorporated into HIV-1 cores and inhibits nuclear entry of viral preintegration complexes. J Virol 93:e01118-19. 10.1128/JVI.01118-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luis Abad J, González MA, del Real G, Mira E, Mañes S, Serrano F, Bernad A. 2003. Novel interfering bifunctional molecules against the CCR5 coreceptor are efficient inhibitors of HIV-1 infection. Mol Ther 8:475–484. 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Porcellini S, Alberici L, Gubinelli F, Lupo R, Olgiati C, Rizzardi GP, Bovolenta C. 2009. The F12-Vif derivative Chim3 inhibits HIV-1 replication in CD4+ T lymphocytes and CD34+-derived macrophages by blocking HIV-1 DNA integration. Blood 113:3443–3452. 10.1182/blood-2008-06-158790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker RC, Jr, Khan MA, Kao S, Goila-Gaur R, Miyagi E, Strebel K. 2010. Identification of dominant negative human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif mutants that interfere with the functional inactivation of APOBEC3G by virus-encoded Vif. J Virol 84:5201–5211. 10.1128/JVI.02318-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cano J, Kalpana GV. 2011. Inhibition of early stages of HIV-1 assembly by INI1/hSNF5 transdominant negative mutant S6. J Virol 85:2254–2265. 10.1128/JVI.00006-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duan S, Wang S, Song Y, Gao N, Meng L, Gai Y, Zhang Y, Wang S, Wang C, Yu B, Wu J, Yu X. 2020. A novel HIV-1 inhibitor that blocks viral replication and rescues APOBEC3s by interrupting vif/CBFβ interaction. J Biol Chem 295:14592–14605. 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bennett RP, Salter JD, Smith HC. 2018. A new class of antiretroviral enabling innate immunity by protecting APOBEC3 from HIV Vif-dependent degradation. Trends Mol Med 24:507–520. 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cherf GM, Cochran JR. 2015. Applications of yeast surface display for protein engineering. Methods Mol Biol 1319:155–175. 10.1007/978-1-4939-2748-7_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kane JR, Stanley DJ, Hultquist JF, Johnson JR, Mietrach N, Binning JM, Jónsson SR, Barelier S, Newton BW, Johnson TL, Franks-Skiba KE, Li M, Brown WL, Gunnarsson HI, Adalbjornsdóttir A, Fraser JS, Harris RS, Andrésdóttir V, Gross JD, Krogan NJ. 2015. Lineage-specific viral hijacking of non-canonical E3 ubiquitin ligase cofactors in the evolution of Vif anti-APOBEC3 activity. Cell Rep 11:1236–1250. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ai Y, Zhu D, Wang C, Su C, Ma J, Ma J, Wang X. 2014. Core-binding factor subunit beta is not required for non-primate lentiviral Vif-mediated APOBEC3 degradation. J Virol 88:12112–12122. 10.1128/JVI.01924-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dang Y, Wang X, Zhou T, York IA, Zheng YH. 2009. Identification of a novel WxSLVK motif in the N terminus of human immunodeficiency virus and simian immunodeficiency virus Vif that is critical for APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F neutralization. J Virol 83:8544–8552. 10.1128/JVI.00651-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyagi E, Welbourn S, Sukegawa S, Fabryova H, Kao S, Strebel K. 2020. Inhibition of Vif-mediated degradation of APOBEC3G through competitive binding of core-binding factor beta. J Virol 94:e01708-19. 10.1128/JVI.01708-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyagi E, Kao S, Yedavalli V, Strebel K. 2014. CBFβ enhances de novo protein biosynthesis of its binding partners HIV-1 Vif and RUNX1 and potentiates the Vif-induced degradation of APOBEC3G. J Virol 88:4839–4852. 10.1128/JVI.03359-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsui Y, Shindo K, Nagata K, Yoshinaga N, Shirakawa K, Kobayashi M, Takaori-Kondo A. 2016. Core binding factor β protects HIV, type 1 accessory protein viral infectivity factor from MDM2-mediated degradation. J Biol Chem 291:24892–24899. 10.1074/jbc.M116.734673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bour S, Strebel K. 2000. HIV accessory proteins: multifunctional components of a complex system. Adv Pharmacol 48:75–120. 10.1016/s1054-3589(00)48004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jäger S, Kim DY, Hultquist JF, Shindo K, LaRue RS, Kwon E, Li M, Anderson BD, Yen L, Stanley D, Mahon C, Kane J, Franks-Skiba K, Cimermancic P, Burlingame A, Sali A, Craik CS, Harris RS, Gross JD, Krogan NJ. 2011. Vif hijacks CBF-β to degrade APOBEC3G and promote HIV-1 infection. Nature 481:371–375. 10.1038/nature10693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zuo T, Liu D, Lv W, Wang X, Wang J, Lv M, Huang W, Wu J, Zhang H, Jin H, Zhang L, Kong W, Yu X. 2012. Small-molecule inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by targeting the interaction between Vif and ElonginC. J Virol 86:5497–5507. 10.1128/JVI.06957-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee YM, Tang XB, Cimakasky LM, Hildreth JE, Yu XF. 1997. Mutations in the matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibit surface expression and virion incorporation of viral envelope glycoproteins in CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Virol 71:1443–1452. 10.1128/JVI.71.2.1443-1452.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harding PJ, Attrill H, Boehringer J, Ross S, Wadhams GH, Smith E, Armitage JP, Watts A. 2009. Constitutive dimerization of the G-protein coupled receptor, neurotensin receptor 1, reconstituted into phospholipid bilayers. Biophys J 96:964–973. 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]