Abstract

Objective:

To examine whether the functionally advantageous KL-VS variant of the KLOTHO gene attenuates age-related alteration in CSF biomarkers or cognitive function in a cohort of middle-aged and older adults enriched for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk.

Methods:

Sample included non-demented adults (N=225, mean age = 63±8, 68% women; excluding MCI and any dementia diagnosis) from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention (WRAP) and the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (W-ADRC) who were genotyped for KL-VS, underwent CSF sampling and had neuropsychological testing data available proximal to CSF draw. Covariate-adjusted multivariate regression examined relationships between age group (Younger vs. Older; mean split at 63 years), AD biomarkers, and neuropsychological performance tapping memory and executive function, and whether these relationships differed by KL-VS status (non-carrier (KL-VSNC) vs. heterozygote (KL-VSHET)).

Results:

In the pooled analyses, older age was associated with higher levels of total tau (tTau), phosphorylated tau (pTau), and their respective ratios to amyloid-β(Aβ)42 (P’s ≤ 0.002), and with poorer performance on all cognitive tests (P ‘s ≤ 0.001). In the stratified analyses, KL-VSNC exhibited this age-related pattern of associations with CSF biomarkers (all P ‘s ≤ .001), which were abated in KL-VSHET (P ‘s ≥ 0.14). Similarly, KL-VSNC exhibited age-related deficits in memory and executive function (p’s ≤0.003), which again were attenuated in KL-VSHET (P ‘s ≥ 0.18).

Conclusion:

Worse memory and executive function, and higher tau burden with age were attenuated in carriers of a functionally advantageous KLOTHO variant. KL-VS heterozygosity seems to be protective against age-related cognitive and biomolecular alterations that confer risk for AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Biomarkers, CSF, Memory, Executive Function

INTRODUCTION

Age is the single biggest risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1]. Currently the sixth leading cause of death in the developed world [2], AD is a progressive, irreversible and debilitating neurological disorder of old age, marked clinically by memory loss and neuropathologically by accumulation of plaques and tangles in the brain [3]. No effective treatments are currently available. With the mean population age steadily rising and the personal and socioeconomic costs of AD mounting, it is imperative to identify approaches that prevent, delay or treat the disease.

The long-standing belief that dementia, and the accumulation of its pathognomonic brain lesions, is an inevitable consequence of aging has been challenged on multiple fronts. We now know that it is possible to age successfully [4], that not all individuals at genetic risk develop AD [5], and that even many individuals with AD neuropathology are able to maintain high levels of cognitive function well into old age [6,7]. This has shifted the focus from risk factors onto potentially protective or compensatory mechanisms, and thereby on prevention of disability and disease [8].

Klotho is a transmembrane protein and longevity factor [9,10]. Two KLOTHO single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs9536314 and rs9527025) segregate to form a functional haplotype, KL-VS, that modulates klotho secretion in humans [11–13]. Several recent meta-analyses indicated a significant association of KL-VS heterozygosity (KL-VSHET), which is the functionally advantageous KLOTHO genotype, with various favorable outcomes including longevity, and better cardiovascular health and cognitive function [12–18]. It remains unknown whether favorable outcomes related to KLOTHO heterozygosity within the context of normal aging extend to those at risk for developing neurogenerative disease, and specifically AD. The literature related to AD and its biomarkers has only began to address β-amyloid (Aβ) accumulation, whereby KL-VS heterozygosity seems to be associated with lesser Aβ burden [11,19] and lower AD risk [19] in APOE4 carriers. In light of the current gaps in the literature, we extend the investigations of the protective role of KL-VS to measures of tau in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), as well as episodic memory and executive function, given their sensitivity to incipient AD [20].

Here we leveraged data from risk-enriched, late-middle-aged adults from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention (WRAP) and the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (W-ADRC) to examine whether KLOTHO confers resilience against age-related changes in (1) cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of AD and (2) cognition. We predicted that the expected adverse effect of age on both cognitive performance and AD CSF biomarkers will be attenuated in carriers of the functionally advantageous genotype of KLOTHO, i.e., KL-VSHET.

METHODS

Participants

The current sample is comprised of 225 cognitively normal adults (age range 45–65 at study entry; 68% female) who are enrolled in either WRAP [19] or the W-ADRC’s IMPACT (Investigating Memory in Preclinical AD–Causes and Treatments) cohorts, both enriched for AD risk based on parental history [11]. Participants in this report were chosen based on availability of genetic, CSF, and neuropsychological data and all were characterized as cognitively normal based on standardized, multidisciplinary, consensus conferences diagnosis [11,21]. All study procedures were approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board and signed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from blood using the PUREGENE DNA Isolation Kit (Gentra Systems, Inc, Minneapolis, MN). DNA concentrations were quantified using ultraviolet spectrophotometry (DU 530 Spectrophotometer, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). LGC Genomics (Beverly, MA) performed genotyping for APOE (rs429358 and rs7412) and KLOTHO (rs9536314 and rs9527025) using competitive allele-specific PCR-based KASP genotyping assays. Quality control procedures have been previously published [11,22] and are deemed satisfactory. As expected based on HapMap and the literature [12,23,24], rs9536314 and rs9527025 were in perfect linkage disequilibrium in our study population as well.

CSF assessment

Lumbar puncture was performed in the morning after a 12-hour fast with a Sprotte 24- or 25-gauge spinal needle at L3–4 or L4–5 with extraction into polypropylene syringes. Each sample consisted of 22 mL CSF, which was then combined, gently mixed, and centrifuged at 2,000g for 10 minutes. Supernatants were frozen in 0.5mL aliquots in polypropylene tubes and stored at −80°C. The samples were immunoassayed for Aβ42, total tau (tTau) and phosphorylated tau181 (pTau) with INNOTEST ELISAs (Fujirebio, Ghent, Belgium), as previously described [11,25].

Neuropsychological Testing.

Participants completed a comprehensive cognitive test battery [26,27]. The assessment spanned five cognitive domains: episodic memory, attention, executive function, language, and visuospatial ability. Here we primarily focused on measures of episodic memory (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, RAVLT) [28] and executive function (Trail Making Test, TMT, Parts A & B) [29] given their sensitivity to incipient AD [20], and also because they were the tests that are common to both WRAP and the W-ADRC batteries. For the RAVLT, we focused on Total Learning (sum of Trials 1–5) and Long Delay whereas for the TMT we analyzed time to test completion.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were done in SPSS, v. 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Participants were split into two age groups—Younger vs Older—for analytical purposes, using the mean age of 63 years. For the CSF biomarkers, a series of linear regression models that included terms for age, sex, APOE ε4 status, and parental history of AD were fitted to first ascertain the effect of age on the biomarkers. Then, the analyses were repeated after stratifying the sample by KL-VS genotype [30] in keeping with the existing literature [11,31], to determine whether the deleterious effect of age differed as a function of KL-VS status (non-carriers (KL-VSNC)) vs. heterozygotes (KL-VSHET)). KL-VS homozygosity, which is associated with lower levels of klotho, decreased longevity and worse cognition, is a rare genotype [12] (N=5 in our cohort) and was omitted from analysis. For the cognitive measures, the same analytical strategy was adopted, with the inclusion of education as an additional covariate. Whenever possible, neuropsychological data corresponding to the visit at which lumbar puncture was performed was used; otherwise, analysis was restricted to neuropsychological test data most proximal to lumbar puncture (within one year before or after; time interval M(SD) = 0.16 (0.34) years). We compared the groups on demographic characteristics either using χ2 or independent-samples t-tests.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics.

Characteristics of the entire sample, and also stratified by KL-VS, are detailed in Table 1. Overall, participants were predominantly white (97%) and female (68%) with average age of 62.8±7.9 and education of 16.1±2.5 years. The sample was enriched for AD risk; 42% are APOE ε4 carriers, and 75% have a parental history of dementia. The MMSE scores ranged between 26 and 30, with an average of 29.3±0.86. After stratifying the sample by KL-VS, there were no significant differences (all P’s > 0.3) in any of the above-mentioned characteristics between non-carriers (N=168; 45% (75/168) younger and 55% (93 /168 older)) and heterozygotes (N=57; 56% (32/57) younger and 44% (25/57 older)).

Table 1.

Background characteristics of study participants

| VARIABLE | TOTAL SAMPLE (N =225) | KL-VSNC (N=168) | KL-VSHET (N=57) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 62.85 (7.99) | 62.99 (7.99) | 61.81(8.16) | 0.34 |

| Education, M (SD) | 16.09 (2.51) | 16.06 (2.49) | 16.19 (2.59) | 0.73 |

| MMSE, M (SD) | 29.31 (0.86) | 29.32 (0.89) | 29.30 (0.86) | 0.93 |

| Females, N (%) | 152 (68) | 115 (68) | 37 (65) | 0.62 |

| White, N (%) | 219 (97) | 164 (98) | 55 (97) | 0.34 |

| APOE ε4+, N (%) | 94 (42) | 73 (43) | 21 (37) | 0.38 |

| KL-VSHET, N(%) | 57 25 | - | - | - |

| Parental history of AD, N (%) | 168 (75) | 125 (74) | 43 (75) | 0.88 |

| * Aβ42 negative, N (%) | 25 (11) | 21 (12) | 4 (7) | 0.18 |

| * pTau negative, N (%) | 32 (14) | 22 (13) | 10 (18) | 0.27 |

| * tTau negative, N (%) | 32 (14) | 23 (14) | 9 (16) | 0.42 |

Abbreviations: KL-VSNC = KL-VS non-carriers; KL-VSHET = KL-VS heterozygotes; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination score; APOE ε4+ = APOE ε4 carrier

negative based on our center’s derived cutpoint for CSF AD biomarkers32

We have also assessed how many of the participants in this sample would be considered positive (i.e., abnormal) based on our center’s derived cutpoint for CSF AD biomarkers [32], namely Aβ42 (≤471.54), pTau (≥ 59.5), and tTau (≥ 461.26). Majority of the participants in our sample were negative for both Aβ42 and tau biomarkers. Based on χ2-tests, the percentage of those who were Aβ42 positive did not significantly differ between KL-VS heterozygotes (7%) versus non-carriers (12%) (p = 0.18). Similarly, the percentage of those who were positive based on pTau did not significantly differ between KL-VS heterozygotes (18%) and non-carriers (13%) (p = 0.27). Finally, based on the tTau measure, the percentage of those who were positive did not significantly differ between KL-VS heterozygotes (16%) and non-carriers (14%) (p = 0.42).

Relationships between age and CSF or cognitive measures.

In the entire sample, Aβ42 did not differ significantly between the Younger and Older groups (P = 0.8). As expected, Older age was associated with both tau accumulation and worse cognitive performance. Specifically, the Older group had significantly higher levels of CSF tTau and pTau (both P’s ≤ 0.001), as well as their respective ratios to Aβ42 (both P’s ≤ 0.002). Similarly, the Older group exhibited significantly lower cognitive performance across all neuropsychological measures of interest (all P’s ≤ 0.001). The same pattern of results remains when age is used as a continuous variable (Aβ42: P = 0.56; all other P’s ≤ 0.001).

Adverse effect of age on CSF and cognitive measures varies by KL-VS genotype.

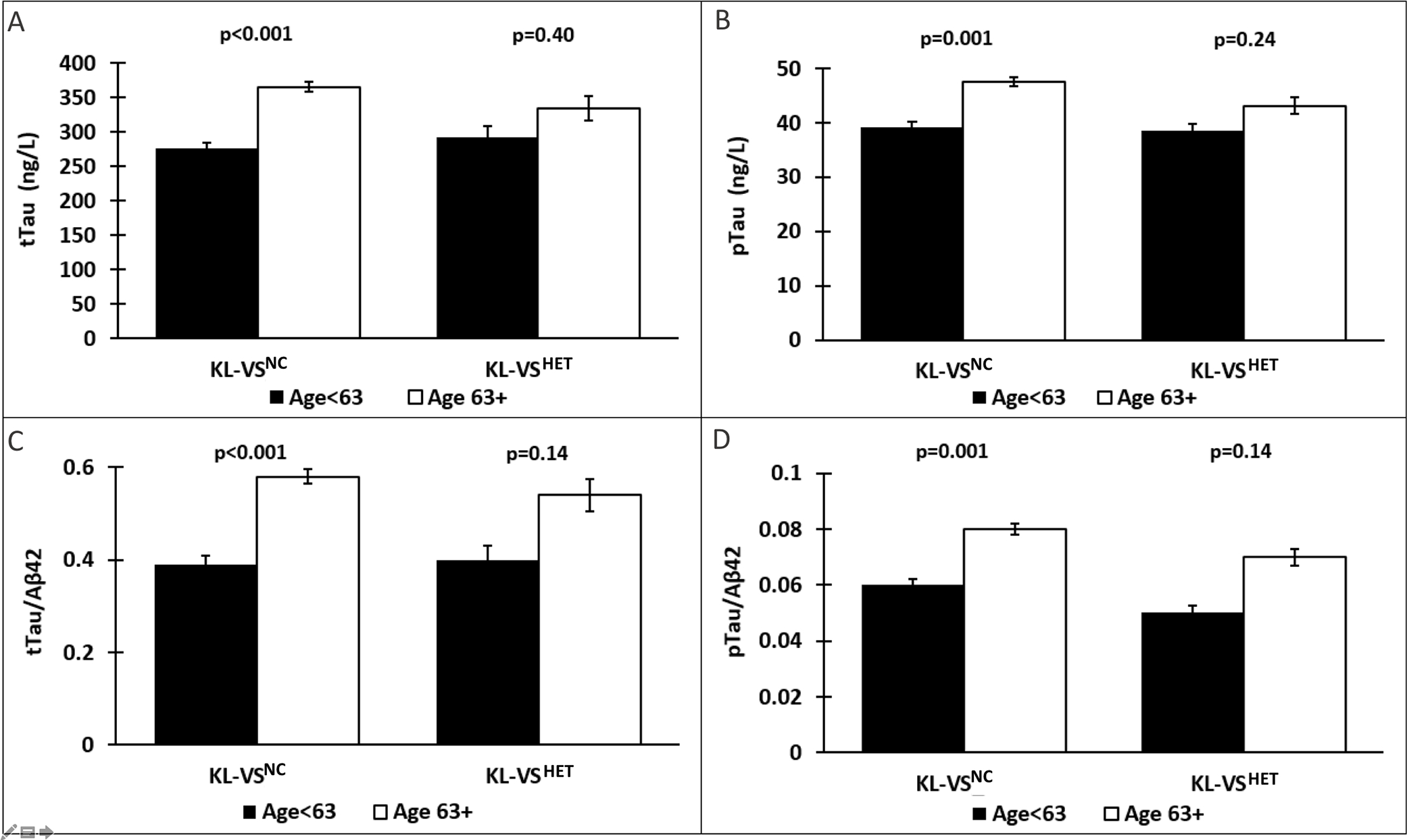

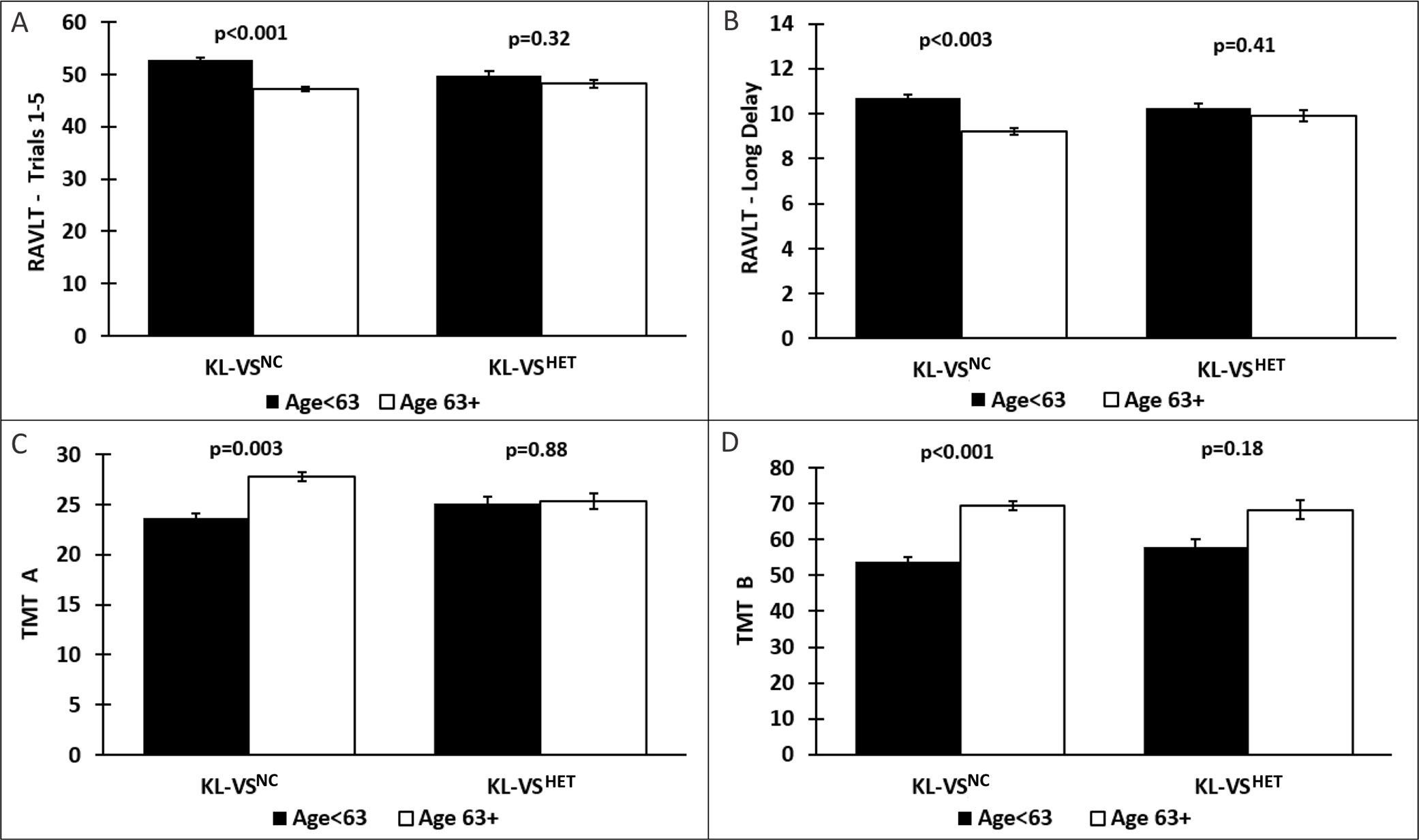

In the KL-VSNC, the Older age group consistently exhibited the expected pattern of higher tau values (Table 2; Figure 1) and worse cognitive performance (Table 3; Figure 2) across measures (all P’s ≤ 0.003). In contrast, age-related differences in tau burden and cognitive performance were attenuated across the board in KL-VSHET (all P’s ≥ 0.1). The results of our stratified analyses were confirmed by unstratified moderation analysis (all P’s ≤ 0.004).

Table 2.

Association between CSF AD biomarkers and age across KL-VS strata

| CSF MEASURE | AGE GROUP | KL-VSNC | KL-VSHET | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SE) | F (df) | P | M (SE) | F(df) | P | ||

| Aβ42 | <63 | 718.59 (22.88) | 0.001 (1,163) | 0.98 | 740.77 (35.18) | 0.51 (1,52) | 0.48 |

| ≥63 | 719.17 (20.47) | 705.44 (39.96) | |||||

| tTau | <63 | 275.74 (16.12) | 16.40 (1,163) | <0.001 | 292.59 (31.39) | 0.71 (1,52) | 0.40 |

| ≥63 | 364.99 (14.42) | 333.61 (35.66) | |||||

| pTau | <63 | 39.21 (1.82) | 11.45 (1,163) | 0.001 | 38.46 (2.78) | 1.41 (1,52) | 0.24 |

| ≥63 | 47.64 (1.63) | 43.12 (3.15) | |||||

| tTau/Aβ42 | <63 | 0.39 (0.04) | 16.27 (1,163) | <0.001 | 0.40 (0.06) | 2.25 (1,52) | 0.14 |

| ≥63 | 0.58 (0.03) | 0.54 (0.07) | |||||

| pTau/Aβ42 | <63 | 0.06 (0.004) | 12.54 (1,163) | 0.001 | 0.05 (0.005) | 2.28 (1,52) | 0.14 |

| ≥63 | 0.08 (0.004) | 0.07 (0.006) | |||||

Abbreviations: KL-VSNC = KL-VS non-carriers; KL-VSHET = KL-VS heterozygotes; Aβ42 = β-amyloid42; tTau = total tau; pTau = phosphorylated tau

Figure 1. Age differentially associates with CSF tau measures as a function of KL-VS status.

Bar graphs depicting group differences (M(SE)) in tau between Younger (black) and Older (white) individuals. Among KL-VSNC, Older age was associated with worse levels of A) total tau (tTau), B) phosphorylated tau (pTau), and their respective ratios to Aβ42 (C & D). This age-related pattern of associations with CSF tau biomarkers was abated in KL-VSHET.

Abbreviations: M=mean; SE=standard error; Aβ42 = β-amyloid42; tTau = total tau; pTau = phosphorylated tau; KL-VSNC = KL-VS non-carriers; KL-VSHET = KL-VS heterozygotes.

Table 3.

Association between cognitive function and age across KL-VS strata

| COGNITIVE MEASURE | AGE GROUP | KL-VSNC | KL-VSHET | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SE) | F (df) | P | M (SE) | F (df) | P | ||

|

RAVLT Trials 1–5 |

<63 | 52.77 (0.91) | 19.43 (1,163) | <0.001 | 49.84 (1.41) | 1.01 (1,52) | 0.32 |

| ≥63 | 47.19 (0.82) | 48.21 (1.61) | |||||

|

RAVLT Long Delay |

<63 | 10.69 (0.36) | 8.86 (1,163) | 0.003 | 10.23 (0.45) | 0.69 (1,52) | 0.41 |

| ≥63 | 9.22 (0.32) | 9.89 (0.51) | |||||

| TMT A (time) | <63 | 23.66 (0.97) | 9.24 (1,163) | 0.003 | 25.15 (1.20) | 0.02 (1,52) | 0.88 |

| ≥63 | 27.80 (0.87) | 25.36 (1.36) | |||||

| TMT B (time) | <63 | 53.69 (2.67) | 18.01 (1,163) | <0.001 | 57.95 (4.46) | 1.81 (1,52) | 0.18 |

| ≥63 | 69.48 (2.39) | 68.31 (5.06) | |||||

Abbreviations: KL-VSNC = KL-VS non-carriers; KL-VSHET = KL-VS heterozygotes; RAVLT = Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; TMT = Trail Making Test

Figure 2. Age differentially associates with measures of episodic memory and executive function as a function of KL-VS status.

Bar graphs depicting group differences (M(SE)) in cognition between Younger (black) and Older (white) individuals. KL-VSNC exhibited age-related deficits in memory (A & B) and executive function (C & D), which were attenuated in KL-VSHET.

Abbreviations: M=mean; SE=standard error; RAVLT = Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (total trials); TMT = Trail Making Test (time in seconds); KL-VSNC = KL-VS non-carriers; KL-VSHET = KL-VS heterozygotes.

Because the sample size of KL-VSNC was about three times that of KL-VSHET (168 vs. 57) we repeated the foregoing analyses on a subsample of 57 KL-VSNC who were perfectly matched on sex and APOE status to the 57 KL-VSHET to rule out the possibility that our results were due to differences in sample size. Nearly identical patterns of results were seen in the matched sub-sample analyses compared to that observed in the full sample. Specifcially, Older KL-VSNC had greater tau accumulation (P’s <0.01), worse executive function (P’s <0.04), and episodic memory (P = 0.01; with the exception of the RAVLT Long Delay measure (P = 0.21)) whereas age-related differences were not significant in KL-VSHET (P’s > 0.14).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report that well-established associations of older age with lower cognition and higher CSF tau levels were mitigated in carriers of a functionally favorable KL-VS genotype in a late-middle-aged cohort enriched for AD risk. Specifcially, in this late middle-aged cohort enriched for AD risk, the expected age-related alterations in tTau, pTau, tTau/Aβ42, and pTau/Aβ42 were observed in KL-VSNC, but not in KL-VSHET. Similarly, whereas older KL-VSNC exhibited expectedly worse memory and executive function compared to younger KL-VSNC, we did not observe the same age-related differences in cognitive performance in KL-VSHET.

The role of KLOTHO in longevity [9,10,13–17] is well-established. There is mounting evidence in support of relationships between KL-VS heterozygosity and preserved brain integrity and cognitive performance during normal aging [12–17,23,24,33,34]. For example, better global cognition is reported in heterozygotes compared to non-carriers in three independent cohorts of non-demented adults [12] as well as slower cognitive decline [32]. Moreover, KL-VSHET exhibit better executive function in conjunction with greater dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume [24] and also show greater intrinsic connectivity in functional brain networks known to be vulnerable to unfavorable effects of aging [34]. Our group has previously reported that KL-VS heterozygosity mitigated negative effects of APOE ε4 on Aβ burden in a late-middle-aged cohort at risk for AD [11]. These findings were confirmed in a recent meta-analysis combining data from 25 studies reporting that APOE ε4 carriers, who were also KL-VS heterozygotes, were at a reduced risk for the combined outcome of conversion to MCI or AD [19]. We add to the current state of the literature by demonstrating that the favorable effects of KL-VSHET extend to age-related tau burden and deficits in memory and executive function in a non-demented sample enriched for AD.

Although topographic evolution of tauopathy in the brain is the basis for Braak neuropathological staging of AD [35], which in turn strongly associates with cognitive impairment [36,37], there is considerable interindividual heterogeneity and significant diagnostic overlap of neuropathological findings in cognitively unimpaired individuals at autopsy [6]. Age is not only the greatest risk factor for clinical AD, but also the most robust determinant of AD biomarker changes and cognitive decline in the absence of manifest disease. Together, the literature underscores the importance of identifying factors that confer resilience. Here, we offer a glimpse into how one genetic factor, KLOTHO, offers resilience against age-related changes in cognition and tau deposition.

KL-VSHET may confer resilience by leading to higher circulating klotho levels [12,24] or changing its functions. In mouse studies, elevating klotho levels extends lifespan [10], enhances cognition [38] and increases resilience to AD-related toxicity [39]. In future studies, it will be interesting to assess whether klotho protein levels in the serum and CSF of individuals associate with measures of AD and preclinical disease. It is interesting to speculate that KL-VSHET individuals could be biologically younger and thus show resilience to age-induced cognitive and tau changes.

Our participants are predominantly white and highly educated. Moreover, they were selected for parental history of AD and consequently many are APOE ε4 carriers, resulting in higher prevalence of both traits in this cohort than what is normally observed in the general population. These characteristics of our cohort may potentially limit the generalizability of our findings. Another potential limitation is the arguably modest sample size after stratification by KLOTHO haplotype and age group, although our findings remained unchanged when the analysis was repeated in an even smaller subsample of matched participants. Lastly, the cross-sectional nature of the present study may be seen as a limitation. This, however, is addressable in future publications as both WRAP and W-ADRC cohorts are prospective and continuing to collect longitudinal CSF and cognitive data.

Overall, our results suggest that KL-VS heterozygosity may attenuate deleterious effects of aging on risk markers for AD. Given the current lack of disease modifying therapies, AD is poised to become a public health crisis. Our results suggest that KL-VS heterozygosity may be protective against age-related cognitive impairment and accumulation of tau burden in CSF. Identification of new genetic variants that modify AD risk will bring to light novel molecular targets for future therapeutic trials. This line of research is poised to identify complementary pathways for curbing the disease progression and delaying symptom onset.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the researchers and staff of the Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, where CSF was assayed. We also thank the staff and study participants of the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention and the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, without whom this work would not be possible.

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging grants K23 AG045957 (O.C.O.), R21 AG051858 (O.C.O.), R01 AG027161 (S.C.J.), P50 AG033514 (S.A.) and P30 AG062715 (S.A.); by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke R01 NS092918 (D.B.D.); and a Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1RR025011) to the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Portions of this research were supported by the Extendicare Foundation; Alzheimer’s Association; Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation; Veterans Administration, including facilities and resources at the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, WI; European Research Council; Torsten Söderberg Foundation; Swedish Brain Foundation; and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

KLOTHO is the subject of a pending international patent application held by the Regents of the University of California. All authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hou Y, Dan X, Babbar M, Wei Y, Hasselbalch SG, Croteau DL, Bohr VA. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2019;15:565–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer’s Association. 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14:367–429. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Cauwenberghe C, Van Broeckhoven C, Sleegers K. The genetic landscape of Alzheimer disease: clinical implications and perspectives. Genet Med 2016;18:421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stern Y, Barnes CA, Grady C, Jones RN, Raz N. Brain reserve, cognitive reserve, compensation, and maintenance: operationalization, validity, and mechanisms of cognitive resilience. Neurobiol Aging 2019;83:124–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallagher M, Okonkwo OC, Resnick SM, Jagust WJ, Benzinger TLS, Rapp PR. What are the threats to successful brain and cognitive aging? Neurobiol Aging 2019;83:130–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Driscoll I, Resnick SM, Troncoso JC, An Y, O’Brien R, Zonderman AB. Impact of Alzheimer’s pathology on cognitive trajectories in nondemented elderly. Ann Neurol 2006;60(6):688–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driscoll I, Troncoso J. Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease: a prodrome or a state of resilience? Curr Alzheimer Res 2011;8(4):330–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singer B, Friedman E, Seeman T, Fava GA, Ryff CD. Protective environments and health status: Cross-talk between human and animal studies. Neurobiol Aging 2005;S26:S113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chateau MT, Araiz C, Descamps S, Galas S. Klotho interferes with a novel FGF-signalling pathway and insulin/Igf-like signalling to improve longevity and stress resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging 2010;2:567–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, Pastor JV, Nandi A, Gurnani P, McGuinness OP, Chikuda H, Yamaguchi M, Kawaguchi H, Shimomura I, Takayama Y, Herz J, Kan CR, Rosenblatt KP, Kuro-o M. Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science 2005;309:1829–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erickson CM, Schultz SA, Oh JM, Darst BF, Ma Y, Norton D, Betthauser T, Gallagher CL, Carlsson CM, Bendlin BB, Asthana S, Hermann BP, Sager MA, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Engelman CD, Chritian BT, Johnson SC, Dubal DB, Okonkwo OC. KLOTHO heterozygosity attenuates APOE4-related amyloid burden in preclinical AD. Neurology 2019;92(16):e1878–e1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubal DB, Yokoyama JS, Zhu L, Broestl L, Worden K, Wang D, Sturm VE, Kim D, Klein E, Yu GQ, Ho K, Eilertson KE, Yu L, Kuro-o M, De Jager PL, Coppola G, Small GW, Bennett DA, Kramer JH, Abraham CR, Miller BL, Mucke L. Life extension factor klotho enhances cognition. Cell Rep 2014;7:1065–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arking DE, Krebsova A, Macek M Sr, Macek M Jr, Arking A, Mian IS, Fried L, Hamosh A, Dey S, McIntosh I, Dietz HC. Association of human aging with a functional variant of klotho. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:856–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheikhi A, Barchowsky A, Sahu A, Shinde SN, Pius A, Clemens ZJ, Li H, Kennedy CA, Hoeck JD, Franti M, Ambrosio F. Klotho: An elephant in aging research. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2019;74(7):1031–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Bona D, Accardi G, Virruso C, Candore G, Caruso C. Association of Klotho polymorphisms with healthy aging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rejuvenation Res 2014;17:212–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montesanto A, Dato S, Bellizzi D, Rose G, Passarino G. Epidemiological, genetic and epigenetic aspects of the research on healthy ageing and longevity. Immunity & Ageing 2012, 9:6–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revelas M, Thalamuthu A, Oldmeadow C, Evans TJ, Armstrong NJ, Kwok JB, Brodaty H, Schofield PR, Scott RJ, Sachdev PS, Attia JR, Mather KA. Review and meta-analysis of genetic polymorphisms associated with exceptional human longevity. Mech Ageing Dev 2018;175:24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vo HT, Laszczyk AM, King GD. Klotho, the Key to Healthy Brain Aging? Brain Plast 2018;3(2):183–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belloy ME, Napolioni V, Han SS, Le Guen Y, Greicius MD, for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Associations of Klotho-KS heterozygosity with risk of Alzheimer’s disease in individuals who carry APOE4. JAMA Neurol 2020;Epub ahead of print.w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blacker D, Lee H, Muzikansky A, Martin EC, Tanzi R, McArdle JJ, Moss M, Albert M. Neuropsychological measures in normal individuals that predict subsequent cognitive decline. Arch Neurol 2007;64(6):862–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson SC, Koscik RL, Jonaitis EM, Clark LR, Mueller KD, Berman SE, Bendlin BB, Engelman CD, Okonkwo OC, Hogan KJ, Asthana S, Carlsson CM, Hermann BP, Sager MA. The Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention: a review of findings and current directions. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2018;10:130–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darst BF, Koscik RL, Racine AM, Oh JM, Krause RA, Carlsson CM, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Christian BT, Bendlin BB, Okonkwo OC, Hogan KJ, Hermann BP, Sager MA, Asthana S, Johnson SC, Engelman CD. Pathway-specific polygenic risk scores as predictors of amyloid-beta deposition and cognitive function in a sample at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;55:473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arking DE, Atzmon G, Arking A, Barzilai N, Dietz HC. Association between a functional variant of the KLOTHO gene and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood pressure, stroke, and longevity. Circ Res 2005;96:412–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yokoyama JS, Sturm VE, Bonham LW, Klein E, Arfanakis K, Yu L, Coppola G, Kramer JH, Bennett DA, Miller BL, Dubal DB. Variation in longevity gene KLOTHO is associated with greater cortical volumes. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2015;2:215–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmqvist S, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Vestberg S, Andreasson U, Brooks DJ, Owenius R, Hägerström D, Wollmer P, Minthon L, Hansson O. Accuracy of brain amyloid detection in clinical practice using cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid 42: a cross-validation study against amyloid positron emission tomography. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:1282–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sager MA, Hermann B, La Rue A. Middle-aged children of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: APOE genotypes and cognitive function in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2005;18(4):245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, Ferris S, Graff-Radford NR, Chui H, Cummings J, DeCarli C, Foster NL, Galasko D, Peskind E, Dietrich W, Beekly DL, Kukull WA, Morris JC. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23(2):91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt M Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test: A Handbook. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reitan R, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and clinical interpretation. Tucson: Neuropsychology Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Behrens G, Winkler TW, Gorski M, Leitzmann MF, Heid IM. To stratify or not to stratify: power considerations for population-based genome-wide association studies of quantitative traits. Genet Epidemiol 2011;35:867–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porter T, Burnham SC, Milicic L, Savage G, Maruff P, Lim YY, Ames D, Masters CL, Martins RN, Rainey-Smith S, Rowe CC, Salvado O, Groth D, Verdile G, VIllemagne VL, Laws SM. Klotho allele status is not associated with Aβ and APOE ε4-related cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2019;76:162–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark LR, Berman SE, Norton D, Koscik RL, Jonaitis E, Blennow K, Bendlin BB, Asthana S, Johnson SC, Zetterberg H, Carlsson CM. Age-accelerated cognitive decline in asymptomatic adults with CSF β-amyloid. Neurology. 2018;90(15):e1306–e1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de VriesCF, Staff RT, Se Harris, Chapko D, Williams DS, Reichert P, Ahearn T, McNeil CJ, Whalley LJ, Murray AD. Klotho, APOEepsilon4, cognitive ability, brain size, atrophy and survival: a study in Aberdeen Birth Cohort of 1936. Neurobiol Aging 2017;55:91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yokoyama JS, Marx G, Brown JA, Bonham LW, Wang D, Coppola G, Seeley WW, Rosen HJ, Miller BL, Kramer JH, Dubal DB. Systemic klotho is associated with KLOTHO variation and predicts intrinsic cortical connectivity in healthy human aging. Brain Imaging Behav 2017; 11(2):391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 1991;82(4):239–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duyckaerts C, Bennecib M, Grignon Y, Uchihara T, He Y, Piette F, Hauw JJ. Modeling the relation between neurofibrillary tangles and intellectual status. Neurobiol Aging 21997;18(3):267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Kelly JF,Aggarwal NT, Shah RC, Wilson RS. Neuropathology of older persons without cognitive impairment from two community-based studies. Neurology 2006;66:1837–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leon J, Moreno AJ, Garay BI, Chalkley RJ, Burlingame AL, Wang D, Dubal DB. Peripheral Elevation of a Klotho Fragment Enhances Brain Function and Resilience in Young, Aging, and α-Synuclein Transgenic Mice. Cell Rep 2017;20(6):1360–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubal DB, Zhu L, Sanchez PE, Worden K, Broestl L, Johnson E, Ho K, Yu GQ, Kim D, Betourne A, Kuro-O M, Masliah E, Abraham CR, Mucke L. Life extension factor klotho prevents mortality and enhances cognition in hAPP transgenic mice. J Neurosci 2015;35(6):2358–2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]