Abstract

Uptake of cobalamins by the transporter protein BtuB in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli requires the proton motive force and the transperiplasmic protein TonB. The Ton box sequence near the amino terminus of BtuB is conserved among all TonB-dependent transporters and is the only known site of mutations that confer a transport-defective phenotype which can be suppressed by certain substitutions at residue 160 in TonB. The crystallographic structures of the TonB-dependent transporter FhuA revealed that the region near the Ton box, which itself was not resolved, is exposed to the periplasmic space and undergoes an extensive shift in position upon binding of substrate. Site-directed disulfide bonding in intact cells has been used to show that the Ton box of BtuB and residues around position 160 of TonB approach each other in a highly oriented and specific manner to form BtuB-TonB heterodimers that are stimulated by the presence of transport substrate. Here, replacement of Ton box residues with proline or cysteine revealed that residue side chain recognition is not important for function, although replacement with proline at four of the seven Ton box positions impaired cobalamin transport. The defect in cobalamin utilization resulting from the L8P substitution was suppressed by cysteine substitutions in adjacent residues in BtuB or in TonB. This suppression did not restore active transport of cobalamins but may allow each transporter to function at most once. The uncoupled proline substitutions in BtuB markedly affected the pattern of disulfide bonding to TonB, both increasing the extent of cross-linking and shifting the pairs of residues that can be joined. Cross-linking of BtuB and TonB in the presence of the BtuB V10P substitution became independent of the presence of substrate, indicating an additional distortion of the exposure of the Ton box in the periplasmic space. TonB action thus requires a specific orientation for functional contact with the Ton box, and changes in the conformation of this region block transport by preventing substrate release and repeated transport cycles.

TonB function is crucial for the operation of energy-dependent transport systems across the outer membrane (OM) of gram-negative bacteria (reviewed in references 19, 30, and 32). These transport systems carry out the high-affinity uptake of corrinoids, such as vitamin B12 (cyano-cobalamin [CN-Cbl]), and of iron complexes with siderophores or host iron-binding proteins. These nutrients are too large or scarce in natural environments to diffuse effectively through the porin channels, and they require specialized uptake mechanisms comprising a specific, high-affinity OM transporter and an ATP-dependent periplasmic permease system for transport across the cytoplasmic membrane. Transport across the OM depends on energy coupling through the action of the TonB protein (15, 34). TonB spans the periplasmic space to interact with its accessory proteins ExbB and ExbD in the cytoplasmic membrane and with the OM transporters (23, 35).

The crystallographic structures of the Escherichia coli ferric hydroxamate OM transporter FhuA (12, 25) and the ferric enterobactin OM transporter FepA (7) were very similar. The C-terminal region of each forms a 22-stranded transmembrane β-barrel with short periplasmic turns and large extracellular loops which partially occlude the top of the channel. The N-terminal 153 residues of FepA or 160 residues of FhuA form a novel conformation, termed a plug, cork, or hatch, which is held in the barrel by an extensive series of hydrogen bonds and salt bridges and which occludes the central channel to prevent ion fluxes (4, 26). In the FhuA crystal structure, the substrate ferrichrome was found to bind to residues on the upper face of the central domain and on two external loops of the barrel (25). The binding of ferrichrome to FhuA had little effect on the conformation of residues around its binding pocket but resulted in a substantial conformational change in the N-terminal segment of the protein exposed to the periplasmic opening of the barrel.

Part of the N-terminal segment has been implicated in TonB function. Called the Ton box, it is one of the conserved motifs that define the family of TonB-dependent transporters (19). The Ton box in the cobalamin transporter BtuB has the sequence DTLVVTA between residues 6 and 12. Some mutations affecting this region in numerous TonB-dependent transporters result in a unique phenotype, characterized by loss of TonB-dependent functions but without deficit in protein stability, membrane insertion, substrate binding, or TonB-independent transport activities (3, 10, 16, 22, 33, 37, 38). This TonB-uncoupled phenotype can be partially suppressed by amino acid changes elsewhere in the Ton box or at Gln-160 in TonB (3, 13, 17, 37, 38). These results suggested that the Ton box regions might be sites of interaction with TonB, but some investigators claimed that more-direct evidence was needed to show their contact (20).

Formaldehyde-dependent covalent cross-linking of TonB to FepA and FhuA allowed Postle and colleagues (22, 31, 39) to demonstrate that contact of TonB to both OM proteins occurred and was affected by the presence of their transport substrate and by the integrity of the Ton box. The sites of protein contact could not be deduced owing to the nonspecific action of this cross-linking agent. Subsequently, we (8) used site-directed disulfide bonding to show that disulfide bonds between introduced cysteine residues in the Ton box of BtuB and in the vicinity of residue 160 of TonB could be formed. Disulfide-bonded BtuB-TonB heterodimers were formed in intact cells only between Cys residues at specific positions in both proteins. Thus, TonB with the Q16OC substitution (TonB Q160C) formed cross-links mainly to BtuB L8C and V10C, whereas TonB Q162C reacted with BtuB L8C and A12C and weakly with BtuB Vl0C and T11C, and TonB Y163C reacted only with BtuB A12C. This high degree of selectivity for cross-linking indicated that this portion of TonB approaches the Ton box of BtuB in a specific and oriented manner. For most pairs, cross-linking was stimulated by the presence of the transport substrate CN-Cbl.

Here we analyzed BtuB variants in which Cys and Pro substitutions were systematically scanned through the Ton box and show that a Pro substitution at only a few sites confers the TonB-uncoupled phenotype. The L8P and Vl0P substitutions, which strongly interfered with CN-Cbl transport, markedly affected the pattern of disulfide binding between Cys residues in TonB and in the Ton box. The altered reactivities of these Pro-Cys double mutants with the TonB Cys variants showed that the uncoupling mutations did not prevent BtuB-TonB contact but caused a dramatic change in the positional specificity of their interaction. Finally, the process of suppression was found not to restore normal transport function but did allow BtuB to transport substrate in a very limited and energy-uncoupled manner.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

E. coli strain JM109 (Stratagene) was used as the host for plasmid construction and maintenance. Phenotypic and cross-linking analyses of BtuB and TonB variants used the following derivatives of strain MC4100 [Δ(argF-lac)U169 araD139 rpsL150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR22 non-9 gyrA219] (9). Strain RK8452 is metE70 ΔbtuB::Km; RK5016 is metE70 argH btuB recA; RK5043 is metE70 tonB recA; NC11 is metE70 tonB::Km polA; NC12 is metE70 btuB::Tn10 tonB::Km. The tonB::Km allele was introduced by P1 transduction from strain KP1032, which was obtained from K. Postle. Transfer of mutations to the chromosome of E. coli used strains DHB6521, containing the λlnCh1 vector (cl857 Sam7), compatible with pBR vectors (5), DHB6501, the permissive strain for propagation of the phage, and EMG2 (F′λ+), a strain containing the pKO3 vector for allelic replacement (24).

Isolation and manipulations of DNA followed standard protocols (36). Plasmid pAG1 carrying the btuB gene in pBR322 was previously described (13). Plasmid pNC1 carries the E. coli tonB and exbBD coding sequences under the control of their native promoters and was constructed by PCR amplification of both loci from the chromosome of strain JM109. Each PCR primer introduced unique restriction sites at each end of the fragment; primer sequences are available upon request. The resulting amplimers were ligated into the corresponding sites of the polylinker region site of plasmid pSU19 (27), tonB as a 988-bp PstI-SalI fragment, and exbBD as a 1,321-bp AvaI-SacI fragment. Plasmids containing separate tonB (pNC2) or exbBD (pNC3) inserts were constructed similarly.

Plasmid DNA was introduced into host strains by CaCl2-mediated transformation. Plasmid-bearing cells were maintained in the presence of the appropriate antibiotics at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 40 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml. Growth media were Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or minimal A salts medium (29).

Site-directed mutagenesis.

A two-step PCR method (18) was used to replace the single cysteine residue present in wild-type TonB encoded by plasmid pNC1 with an alanine residue to yield TonB C18A, encoded in plasmid pNC4 (8). The same method was used to create single and double cysteine and proline substitutions in the TonB box region of BtuB (residues 6 to 12) encoded by plasmid pAG1. Plasmid pNC4 was modified by PCR mutagenesis to introduce single cysteine residues at positions 159 to 164 of TonB. All mutational changes were verified by nucleotide sequencing at the University of Virginia Biomolecular Resource Facility.

Genetic techniques.

The btuB variants encoding mutants with single cysteine or proline mutations were introduced into the chromosomal btuB locus of strain RK8452 by allelic replacement using the pKO3 system (24). For this purpose, the wild-type btuB gene was first cloned into plasmid pKO3 and the variant alleles were introduced by replacing a 295-bp HindIII-BsiWI fragment with the corresponding mutated coding sequence. The chromosomal btuB::Km gene of RK8452 was replaced by the mutant alleles in two steps. The conditionally replication-deficient plasmids were introduced by transformation, and Campbell-type integrants at the btuB locus were obtained by selection for chloramphenicol resistance. The second homologous recombination event to remove plasmid sequences and the btuB::Km allele was obtained by selection for resistance to 5% sucrose, and recombinants sensitive to chloramphenicol and kanamycin were chosen (24). Recombinant clones were verified by PCR with primers that amplify the entire btuB locus. The amplified fragments were digested with appropriate restriction enzymes to verify that the kanamycin resistance cassette of strain RK8452 had been replaced by the btuB alleles. The btuB Cys/Pro double mutations were introduced into the attλ site of strain RK8452 using the λlnCh system (5), in which the btuB::Km gene of strain RK8452 is not replaced. Recombinant clones were verified by PCR analysis. The tonB alleles were integrated into the chromosome following transformation into polA tonB strain NC11.

Phenotypic assays. (i) Growth on CN-Cbl.

Strains harboring btuB and/or tonB mutations on plasmids or on the chromosome were tested for growth on minimal A salts-agar plates supplemented with 0.02% glucose, 0.01% arginine, and various concentrations of CN-Cbl (0.1 to 5,000 nM) in place of methionine (2). Results are expressed as the lowest CN-Cbl concentration allowing maximal colony size after a 48-h incubation at 37°C, relative to colony size after growth on methionine-supplemented medium.

(ii) CN-Cbl uptake assay.

CN-[57Co]Cbl (4 μCi/nmol) was prepared by growing cells of Propionibacterium freudenreichii (ATCC 9614) on medium containing 1 mCi of 57CoCl2. After growth of cells for 3 days, labeled cobalamins were extracted with 80% ethanol at 80°C, converted to the CN form, and purified by paper electrophoresis.

E. coli cells were grown in the minimal medium as described above, harvested in mid-exponential growth phase, washed, and suspended in 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.6 (6). Cells were incubated with CN-[57Co]Cbl. Samples (1 ml) were removed at intervals, collected on Millipore filters (0.45 μm, pore size), washed twice with 10 ml of 100 mM LiCl, and dried. Radioactivity in the samples was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Results are expressed as picomoles of CN-Cbl taken up per 109 cells.

(iii) Susceptibility to E colicins and BF23 phase.

Onto soft-agar overlays of each strain on LB agar plates were spotted 5-μl samples of serial 10-fold dilutions of BF23 phage or of culture supernatants containing colicins E1 or E3 induced with mitomycin C. After overnight incubation at 37°C, zones of bacterial killing were seen where the agents had been spotted, and susceptibility is reported as the negative logarithm of the highest dilution that gave a zone of complete clearing.

Disulfide cross-linking analysis.

Cells of btuB strain RK5016 carrying pairs of compatible plasmids expressing BtuB and TonB cysteine variants were tested for formation of disulfide-linked species, as previously described (8). Cells were grown in minimal A salts medium supplemented with 0.02% glucose, 0.01% methionine and arginine, 10 mM MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl2, and 100 μg of ampicillin and 40 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:9 into fresh medium and grown to early exponential phase in duplicate tubes. CN-Cbl (5 μM final concentration) was added to one series of cultures for 15 min before the cells were harvested, washed, and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The bacteria were adjusted to the same optical density and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western immunoblotting. Each cross-linking assay was repeated at least twice.

SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis.

The bacterial suspensions were lysed in sample buffer containing 50 mM iodoacetamide to block subsequent disulfide bond formation. Proteins were resolved by electrophoresis on 9.5% (wt/vol) SDS-PAGE gels under nonreducing conditions, using the discontinuous buffer system of Laemmli (21). Resolved proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) by electrophoresis for 1.5 h at 500 mA in buffer consisting of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 192 mM glycine, and 20% (vol/vol) methanol (40). The membranes were blocked in PBS containing 2.5% dried nonfat milk for at least 1 h and were then reacted for 1 h with monoclonal antibodies directed against BtuB (4B1; 1:10) or TonB (4H4; 1:20,000; kindly provided by K. Postle) diluted in the same buffer, as described previously (8). The membranes were washed three times for 10 min in PBS–0.02% Tween 20 before being incubated for 1 h with affinity-purified horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch) diluted 1:5,000 in PBS with 2.5% dried nonfat milk. After three washes in PBS–0.02% Tween 20, the blots were developed using the chemiluminescent substrate LumiGlo (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories) and exposed to X-ray film (Kodak XAR).

RESULTS

Effect of proline substitutions in the BtuB Ton box.

Some mutations affecting the Ton box in several transporters confer an energy-uncoupled phenotype (3, 10, 13, 22, 38). Out of 30 substitutions in the BtuB Ton box only a few displayed this phenotype, with the greatest impairment resulting from Pro or Gly substitutions for residue Leu-8 or Val-10 (13). To systematically investigate the sequence requirements of the BtuB Ton box, residues 6 through 12 were individually changed to Pro or Cys. When these proteins were expressed from a moderate-copy-number plasmid, their levels were similar to that of the wild-type protein (data not shown). The mutated allele encoding each substitution was transferred onto the chromosome by homologous recombination. The BtuB phenotypes determined upon expression from the plasmid or chromosome were comparable, but only the data from single-copy expression are presented (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Phenotypes of proline substitutions in the BtuB Ton box

| btuB allelea | CN-Cbl concn (nM) for maximal growthb | Titerc of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ColE1 | ColE3 | BF23 | ||

| Null | >5,000 | R | R | R |

| WT | 0.5 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| D6P | 0.5 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| T7P | 0.5 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| L8P | >5,000 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| V9P | 0.5 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| V10P | >5,000 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| T11P | 0.5 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| A12P | 0.5 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

The indicated btuB alleles were present in single gene copy at the chromosomal btuB locus in strain RK8452. The alleles are designated by the corresponding amino acid substitution, numbered from the mature sequence. WT, wild type.

Strains were streaked on minimal plates supplemented with required nutrients and serial 10-fold dilutions of CN-Cbl or l-methionine at 100 μg/ml. After the plates were incubated for 40 h at 37°C, the sizes of colonies were estimated, and the lowest concentrations of CN-Cbl allowing a colony size comparable to that on methionine-supplemented medium are reported.

As described in Materials and Methods, serial 10-fold dilutions of the indicated colicins or phage were spotted onto cells in soft-agar layers on LB plates. The titers are the negative logs of the highest dilution of the agent that produces a zone of complete clearing. R, resistant to the highest concentration tested.

The Ton box variants carrying proline substitutions were tested for their ability to allow a metE strain to grow on CN-Cbl in place of methionine. The L8P and V10P variants were completely defective for growth below 5 μM CN-Cbl (Table 1), which is the same behavior as that shown by a btuB or tonB null strain (2). Variants carrying the other five Pro substitutions showed the same growth response as the wild-type protein, i.e., maximal growth with even 0.5 nM CN-Cbl. Thus, Pro substitutions at only positions 8 and 10 interfered with CN-Cbl utilization in the growth assay. Susceptibility to colicins E1 and E3 and phage BF23, which are TonB-independent BtuB substrates, was unaffected in all cases except for the T11P variant, whose susceptibility to all three agents was reduced 10- to 100-fold.

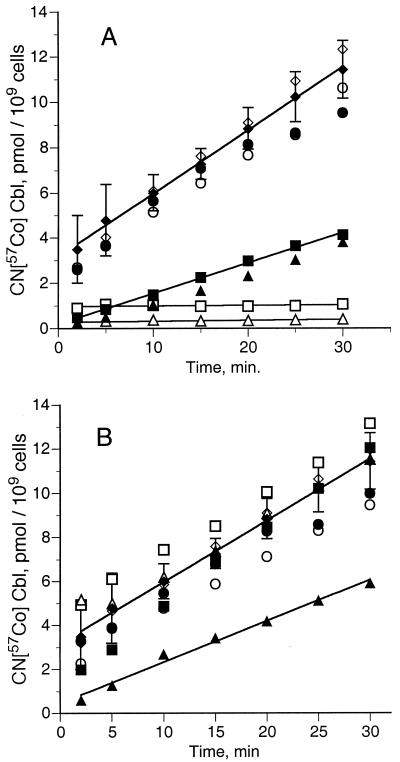

The growth response to CN-Cbl is not a good indicator of BtuB activity because each cell doubling requires the uptake of as few as 25 molecules of CN-Cbl. Assays of CN-[57Co]Cbl uptake provided quantitative information on the effect of these substitutions on BtuB function. The Pro substitutions expressed at single gene copy showed differences in transport activity which were not apparent in the growth assay (Fig. 1A). The L8P and V10P variants showed no significant CN-Cbl uptake subsequent to binding, as expected (13). The L8P mutant bound more CN-Cbl than did the V10P mutant. The V9P and T11P variants showed reduced uptake, and all other variants carrying Pro substitutions flanking positions 8 through 11 had uptake within 10% of that of wild-type BtuB.

FIG. 1.

CN-Cbl uptake by BtuB variants with Ton box substitutions. Derivatives of strain RK8452 carrying the indicated btuB mutations in single gene copy were grown and assayed for rate of uptake of CN-[57Co]Cbl, as described in Materials and Methods. The strains carried Pro substitutions (A) or Cys substitutions (B) at D6 (○), T7 (●), L8 (□), V9 (▪), V10 (▵), T11 (▴), and A12 (⋄). (♦), wild type.

Effect of Cys and Cys-Pro substitutions in the Ton box.

For use in site-directed disulfide bonding and spin labeling (8, 28), single Cys substitutions were introduced at each position in the Ton box of BtuB. The phenotypes conferred by all seven Cys substitutions expressed at single gene copy were indistinguishable from that of the wild type for utilization of CN-Cbl (Table 2) and for susceptibility to the E colicins and phage BF23. Uptake of labeled CN-Cbl was comparable to that of strains carrying wild-type BtuB, except for reduced activity of the T11C variant (Fig. 1 B).

TABLE 2.

CN-Cbl utilization phenotype of cysteine substitutions in the BtuB Ton box and effect of the L8P and V10P substitutionsa

| btuB alleleb | CN-Cbl concn (nM) for maximal growth of a strain carrying BtuB with the indicated substitutionc

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alone | L8P | V10P | |

| WT | 0.5 | >5,000 | >5,000 |

| D6C | 0.5 | 5 | 500 |

| T7C | 0.5 | 0.5 | 100 |

| L8C | 0.5 | NAd | >5,000 |

| V9C | 0.5 | >5,000 | 500 |

| V10C | 0.5 | >5,000 | NA |

| T11C | 0.5 | 5 | >5,000 |

| A12C | 0.5 | 500 | >5,000 |

The lowest concentrations of CN-Cbl that allows formation of colonies of sizes comparable to those on methionine-supplemented medium are reported as in Table 1.

The indicated btuB alleles were present in single gene copy at the attλ locus. Allele designations are as in Table 1. WT, wild type.

Each btuB allele encoded the cysteine substitution indicated in the left column along with either no other amino acid substitution (Alone) or the L8P or V10P substitution.

NA, not applicable.

Two series of double substitutions, which combined the uncoupled L8P or V10P substitution with Cys residues at the remaining positions in the Ton box, were made. These double mutants differed substantially in their ability to utilize CN-Cbl for growth in place of methionine (Table 2). Five of the 12 double mutants, namely, a mutant with L8P and V9C substitutions (L8P V9C), L8P V10C, L8C V10P, V10P T11C, and V10P A12C, showed the complete defect in CN-Cbl utilization as did the single mutants expressing L8P or V10P alone. Four double mutants, L8P A12C, D6C V10P, T7C V10P, and V9C V10P, showed an intermediate phenotype and grew on 100 to 500 nM CN-Cbl. Three double mutants, D6C L8P, T7C L8P, and L8P T11C, grew with CN-Cbl at 0.5 to 5 nM. Similar intragenic suppression of the uncoupled phenotype by other substitutions in the Ton box was described previously (13). All double mutants showed wild-type susceptibility to phage BF23 and normal or slightly reduced response to the E colicins in the case of the V10P series (data not shown).

Intragenic suppression.

The finding that Cys at positions 6, 7, and 11 suppressed the growth defect of the variant with the L8P substitution prompted further analysis of the intragenic-suppression phenotype. CN-Cbl uptake assays showed that none of the double mutants containing Cys substitutions in combination with L8P or V10P showed any detectable CN-Cbl transport beyond the level of binding to BtuB (data not shown), regardless of the ability of the strains to utilize CN-Cbl efficiently for growth.

A more sensitive assay for uptake of labeled CN-Cbl measured its intracellular conversion to other metabolic forms. Strains carrying btuB encoding the L8P substitution (btuB L8P) or btuB T7C L8P in single copy were grown to late exponential phase in 1-liter cultures in minimal medium supplemented with 1 nM CN-[57Co]Cbl. The cell-associated Cbl was measured, extracted from the cells, and resolved by paper electrophoresis. The L8P strain bound an average of 264 molecules of Cbl per cell, and roughly 97% of the label was unaltered CN-Cbl, indicating that this strain can bind but not transport CN-Cbl into the periplasm. The suppressed strain T7C L8P took up 245 molecules of Cbl per cell, of which 81% was CN-Cbl, the remainder being converted to aquo-Cbl (11% of total), methyl-Cbl (7%), and adenosyl Cbl (3%). Thus, the suppressed BtuB variant T7C L8P is capable of a small amount of Cbl uptake, corresponding to less than one molecule of substrate transported per BtuB molecule on the cell surface.

To test whether this low level of CN-Cbl uptake was TonB dependent, plasmids expressing the series of BtuB Cys substitutions in conjunction with L8P were introduced into tonB strain RK5043. The growth responses to various concentrations of CN-Cbl were compared to those of the same strain carrying the btuB+ plasmid pAG1 and of btuB tonB+ strain RK5016. Strikingly, CN-Cbl utilization by the suppressed BtuB variants was almost as effective in the absence of TonB function as in its presence, showing a maximal growth response at 5 nM CN-Cbl, in contrast to the situation for the btuB+ tonB strain, which grew well only at 5 μM CN-Cbl. It was possible that the low level of CN-Cbl entry allowed by the variant BtuB proteins was the result of nonspecific OM leakage. However, the expression of any of these variants did not result in any change in the ability to grow on MacConkey agar or in the size of the zone of growth inhibition surrounding disks containing SDS, deoxycholate, chloramphenicol, rifampin, or erythromycin (data not shown), indicating the retention of the barrier properties of the OM. Thus, the intragenic suppression of the L8P substitution was mediated by the TonB-independent passage across the OM of less than one molecule of substrate per BtuB molecule.

Phenotype produced by Cys substitutions In TonB.

To study the interaction between BtuB and TonB, Cys residues were introduced in TonB at each position between N159 to P164, flanking Q160, the site of suppressors of uncoupled Ton box mutations (2, 17, 37, 38). Their effect on TonB function and on suppression of the defective phenotype of the BtuB L8P and V10P variants was determined. The TonB variants were expressed from plasmid pSU19 together with the accessory proteins, ExbB and ExbD. pSU19 and derived plasmids encoding the TonB variants and ExbB and ExbD were introduced into tonB strain RK5043 to test for complementation of the phenotypic growth defect in CN-Cbl utilization (Table 3). All of the Cys-scanning substitutions in TonB complemented the tonB mutation in strain RK5043 to restore the same level of growth on 0.5 nM CN-Cbl as in a strain carrying the wild-type tonB gene. Strains containing the pSU19 vector or pNC3 (ExbBD alone) showed the same defective growth phenotype as the tonB null strain.

TABLE 3.

Suppression of btuB L8P and V10P mutations by Cys substitutions in TonBa

| Plasmid or plasmid-encoded substitution | Concn of CN-Cbl for maximal growth (nM) of strain carrying:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tonBb |

btuBc

|

|||

| pBtuB+ | pL8P | pV10P | ||

| pSU19 | >5,000 | 0.5 | 5,000 | 5,000 |

| pTonB | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1,000 | 5,000 |

| pExbBD | >5,000 | 0.5 | 5,000 | 5,000 |

| pTonBExbBD | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1,000 | 5,000 |

| C18A | 0.5 | 0.5 | 500 | 5,000 |

| N159C | 0.5 | 0.5 | 500 | 50 |

| Q160C | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| P161C | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1,000 | 5,000 |

| Q162C | 0.5 | 0.5 | 50 | 50 |

| Y163C | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1,000 | 5,000 |

| P164C | 0.5 | 0.5 | 500 | 5,000 |

Concentrations of CN-Cbl affording colony sizes comparable to that on methionine-supplemented medium are reported as in Table 1.

The indicated tonB plasmids were introduced into the tonB strain RK5043 to evaluate their ability to complement the defect in CN-Cbl utilization. No btuB-carrying plasmid was present.

The indicated plasmids were introduced into btuB strain RK5016 in combination with compatible plasmid pAG1 derivatives carrying the wild-type btuB gene or the L8P- or V10P-encoding alleles, as indicated.

To determine the CN-Cbl transport activity of the Cys-substituted TonB variants, each variant gene was transferred to the chromosome in single copy by integration of the tonB exbBD-carrying plasmids in tonB polA host strain NC11. Even when expressed at single gene copy, all Cys-substituted TonB variants conferred the same growth response to CN-Cbl as did wild-type TonB. The uptake of CN-[57Co]Cbl was very close (within 10%) to the wild-type activity, whereas the tonB parent and the strain with the integrated exbBD locus showed no detectable CN-Cbl uptake (data not shown). Thus, the replacement of TonB residues from 159 to 164 with Cys had no detectable effect on TonB function.

Extragenic suppression.

The ability of the TonB Cys variants to suppress the defect in CN-Cbl utilization caused by the BtuB L8P and V10P substitutions was evaluated by growth (Table 3) and transport assays. Plasmids expressing the uncoupled BtuB variants and the panel of TonB Cys substitution variants were transformed pairwise into btuB strain RK5016 and btuB tonB strain NC12. In RK5016 the growth phenotype of the L8P variant, but not that of the V10P variant, was modestly reversed by all plasmids expressing any TonB variant. The TonB Q160C variant, altered at the site of the original suppressors, completely suppressed the growth defect of the BtuB L8P and V10P variants to allow growth on 0.5 nM CN-Cbl. The TonB Q162C variant also showed weaker suppression and allowed growth on 50 nM CN-Cbl. Other TonB Cys substitutions had a moderate effect on the L8P variant (N159C and P164C) and on the V10P variant (N159C) to allow growth on 50 to 500 nM CN-Cbl, indicating the existence of allele-specific interactions between TonB and the BtuB Ton box. Essentially identical growth responses to CN-Cbl were seen when these plasmids were transferred to tonB host strain NC12, showing that suppression was unaffected by the presence of chromosome-encoded wild-type TonB.

As was seen with intragenic suppression, the suppression by TonB Q160C or Q162C of the BtuB L8P or V10P growth defects did not result in any detectable restoration of active accumulation of CN-Cbl in the transport assay, even though the amount of CN-Cbl binding was elevated in response to plasmid carriage of the btuB genes.

Disulfide cross-linking of BtuB and TonB.

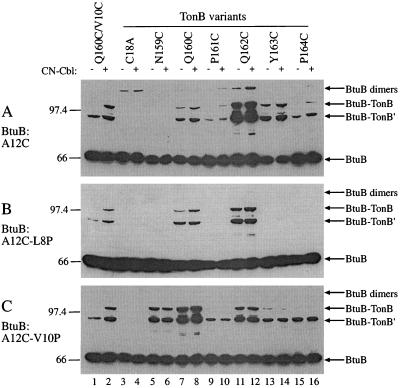

We examined the pattern of site-directed disulfide cross-linking between these cysteine residues in the BtuB Ton box and in TonB. To verify the identity of cross-linked species, we compared the detection of dimers formed between TonB Q160C and BtuB V10C when the primary monoclonal antibodies against BtuB and TonB were used separately with duplicate blots or were combined for detection on a single blot (Fig. 2). The immunoreactive species revealed by anti-BtuB (A) and anti-TonB (B) were identified as the 35-kDa TonB monomer, the 66-kDa BtuB monomer, the 100-kDa BtuB-TonB and 90-kDa BtuB-TonB′ heterodimers shown previously to contain full-length BtuB and the full-length and truncated TonB species, respectively, and the 130-kDa BtuB dimer (8). A 75-kDa species reactive with antibodies to BtuB but not to TonB was present. Probing with both primary antibodies together (C) detected all species reactive with the individual antibodies and demonstrated the comigration of the heterodimeric species. Hence, in subsequent experiments both antibodies were combined to allow detection of all cross-linked species and both monomeric species on the same immunoblot. Note that the addition of CN-Cbl 15 min before cell harvest resulted in substantial increases in the amounts of the BtuB dimer and the BtuB-TonB heterodimers.

FIG. 2.

Western immunoblots comparing the detection of TonB Q160C and BtuB V10C following their coexpression in strain RK5016 in the absence and presence of CN-Cbl (5 μM), using for detection anti-BtuB monoclonal antibody 4B1 diluted 1:10 (A), anti-TonB monoclonal antibody 4H4 diluted 1:20,000 (B), or both antibodies together (C). The protein species are identified on the right, and the mobilities of molecular weight markers are indicated on the left.

All pairwise combinations of cysteine BtuB and TonB variants were examined. Two representative sets of results, in which one BtuB substitution, D6C (Fig. 3A) or A12C (Fig. 4A), was coexpressed with each TonB Cys substitution from N159 to P164. The strain expressing BtuB V10C and TonB Q160C was included as a positive control (lanes 1 and 2), and Cys-less TonB C18A was a negative control (lanes 3 and 4). BtuB D6C showed only weak cross-linking to TonB cysteines at residues 159, 160, and 162 (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 to 16), and it formed homodimers mainly in the presence of CN-Cbl. The BtuB A12C variant formed cross-links to all TonB positions from residues 160 to 164, most strongly to positions 162 and 163 (Fig. 4A). Cross-linking between most positions occurred in the absence of CN-Cbl but was stimulated by its presence. Homodimer formation through residue 12 (A12C) was much weaker than it was through residue 6 (D6C).

FIG. 3.

Western immunoblots showing the cross-linked species produced during coexpression of each member of the series of TonB Cys substitutions from residue 159 to 164, as indicated, with BtuB D6C (A), BtuB D6C L8P (B), and BtuB D6C V10P (C). Cells were grown in the absence or presence of CN-Cbl, added 15 min before harvest, as indicated. Protein detection used a mixture of the monoclonal antibodies reactive to Btub and TonB. Included in the first four lanes are, as a positive control, the pair of BtuB V10C and TonB Q160C, and, as a negative control, the pair of BtuB D6C and TonB C18A lacking a Cys residue. The protein species are identified on the right, and the mobilities of molecular weight markers are indicated on the left.

FIG. 4.

Western immunoblots showing the cross-linked species produced during coexpression of each member of the series of TonB Cys substitutions from residue 159 to 164, as indicated, with BtuB A12C (A), BtuB A12C L8P (B), and BtuB A12C V10P (C). Conditions were as described in the legend to Fig. 3.

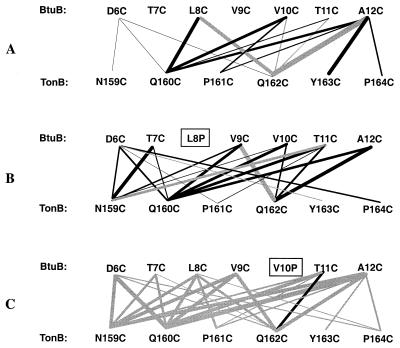

The cross-linking patterns observed for the 42 strains expressing all combinations of Cys substitutions in BtuB and TonB are summarized in Fig. 5A. The occurrence of cross-linking between two residues is indicated by a line whose thickness is roughly related to the amount of heterodimers. These results confirm and extend our previous observations (8) that BtuB positions 6 (D6C), 7 (T7C), and 9 (V9C) cross-link very weakly, if at all, with TonB positions 159 to 164. BtuB cysteines at positions 8 (L8C), 10 (V10C), and 12 (A12C) reacted preferentially with TonB cysteines at positions 160 (Q160C), 162 (Q162C), and 163 (Y163C). All cross-linking, except that involving TonB Q162C, was stimulated by CN-Cbl.

FIG. 5.

Schematic representation summarizing the cross-linking patterns observed upon co expression of the series of TonB Cys substitutions between residues 159 and 164 and the BtuB Cys variants between residues 6 and 12 (A), the BtuB Cys variants in combination with the L8P substitution (B), and the BtuB Cys variants in combination with the V10P substitution (C). The thickness of the lines is related to the relative amounts of the cross-linked species that were formed. Black lines, cross-links whose formation was stimulated by the presence of CN-Cbl; gray lines, cross-links whose formation was not noticeably affected by the presence of CN-Cbl.

Distortion of cross-linking by the BtuB L8P or V10P substitutions.

To examine the effect of the uncoupling mutations on the cross-linking of BtuB and TonB, the L8P and V10P substitutions were combined with the Cys substitutions at the other positions in BtuB and tested for cross-linking with each TonB Cys variant (Fig. 3B and C and 4B and C). The presence of the uncoupling mutations resulted in marked changes in cross-linking pattern, indicating a loss of orientation specificity. When combined with the L8P mutation, the weakly reactive BtuB residue at position 6 (D6C) showed considerably increased cross-linking to most TonB positions, particularly positions 159 (N159C), 160 (Q160C), 163 (Y163C), and 164 (P164C) (compare Fig. 3A and B). Formation of most of the cross-linked species containing BtuB L8P was stimulated by CN-Cbl, as in the wild-type strain (Fig. 3B). The presence of the BtuB L8P substitution reduced the cross-linking activity at position 12 (A12C), leading to loss of detectable cross-linking to TonB positions 161 (P161C), 163 (Y163C), and 164 (P164C) (Fig. 4B). As summarized for all pairs of Cys substitutions in Fig. 5B, the presence of the L8P substitution caused the weakly or nonreactive BtuB positions 6 (D6C), 7 (T7C), and 9 (V9C) to participate in cross-linking with numerous TonB positions. Conversely, the TonB residues at positions 161 (P161C), 163 (Y163C), and 164 (P164C) showed greatly reduced levels of cross-linking and change in linking specificity. The nonreactive residue at position 159 (N159C) reacted with most BtuB L8P positions.

The presence of the V10P substitution also greatly extended the range of cross-linking but revealed a different pattern of reactivities than was seen with the L8P series (Fig. 3C and 4C). When coupled to the V10P substitution, the weakly reactive BtuB residue at position 6 (D6C) showed increased linking with TonB cysteines at 159, 160, 162, and 164 (Fig. 3C). BtuB residue at position 12 (A12C) cross-linked to every position in this region of TonB, quite strongly with the residues at positions 159 (N159C) and 160 (Q160C). Indeed, in the presence of the V10P substitution, almost every Ton box residue reacted with almost every TonB residue to a degree independent of the presence of CN-Cbl (summarized in Fig. 5C). Even the formation of BtuB homodimers carrying V10P was independent of CN-Cbl. Thus, the uncoupling L8P and V10P substitutions resulted in drastic changes in the cross-linking patterns with TonB, suggesting that the access of the Ton box for contact with TonB was increased but the orientation of their contact was decreased in the mutants.

DISCUSSION

Genetic and cross-linking studies have implicated the Ton box as an important element in the response of OM active transport proteins to the energy-coupling factor TonB. Contact between TonB and its client transporters had been deduced from the ability of overexpressed FhuA to stabilize overexpressed TonB from degradation (14) and from direct demonstration of formaldehyde-mediated cross-linking by Postle's laboratory (22, 31, 39) and of site-directed disulfide bonding (8). Results presented here provide information about three major aspects of the interaction of BtuB and TonB.

The first result of this study addressed the sequence requirements for Ton box function, which had not been systematically investigated. The Ton box is one of the few regions that is conserved among TonB-dependent transporters. Despite this conservation, the replacement of each residue through the BtuB Ton box (residues 6 to 12) with Cys caused no detectable defect in function, other than a modest decrease in TonB-dependent activities in the T11C variant, indicating that the recognition of side chains of Ton box residues is not critical for function. Substitutions of proline at residues 8 through 11 impaired TonB-coupled transport function, with positions 8 and 10 being most critical. It was noteworthy that T11P exhibited a decrease in TonB-independent activities. Prolines introduced at flanking residues had no effect on transport. These findings suggest that backbone secondary structure within only a very small region is important for function, perhaps representing a critical hinge or other structural element. The lack of effect of proline or glycine (13) even one residue outside of the region from residues 8 to 11 is consistent with the recognition of this region by specific contact, rather than a global conformational change. Site-directed spin-labeling studies (28) showed that residues in the BtuB Ton box undergo substantial change in mobility in response to binding of substrate.

The nature of intra- and extragenic suppression of Ton box variants of BtuB led to an unexpected view of BtuB action. The defect in CN-Cbl utilization owing to the BtuB L8P substitution was substantially suppressed by nearby D6C, T7C, and T11C substitutions, and the V10P defect was partially suppressed by the T7C substitution. The defect in CN-Cbl utilization of the L8P and the V10P variants could also be strongly suppressed by the TonB Q160C variant and less strongly by the Q162C substitution. These examples of allele-specific suppression could indicate direct interaction of these residues, consistent with their participation as the major sites of disulfide cross-linking (see below).

It is clear that the suppression of the growth phenotype is not accompanied by appreciable restoration of transport activity, and thus suppression must involve the opening of a new pathway of BtuB action. Previous studies of suppression examined mainly the growth response, which requires only uptake of as few as 25 molecules of CN-Cbl per cell doubling of a metE strain (11). The suppression of the BtuB L8P variant by TonB Q160K revealed several unexpected properties, namely, that the suppressor form of TonB still functioned efficiently with wild-type BtuB and behaved in a manner recessive to wild-type TonB (1, 17). The transport assays described here showed that each BtuB L8P molecule, whether suppressed by the T7C change or the changes in TonB at Q160 or Q162, gave very low but detectable transport of CN-Cbl into the cell. This level of transport corresponded to no more than one molecule of CN-Cbl per BtuB protein. This transport by BtuB T7C L8P was TonB independent but was not associated with any detectable increase in OM leakiness.

The results also showed that the suppressor substitutions themselves, BtuB T7C or TonB Q160C, conferred no defect in function with wild-type BtuB. We propose from these findings that BtuB can exist in three transport states. Wild-type BtuB in association with TonB can carry out repeated transport cycles resulting in the accumulation of CN-Cbl in the periplasmic space. A second state is seen for BtuB L8P or wild-type BtuB in the absence of TonB, in which CN-Cbl binds normally to BtuB but is not released at all into the periplasmic space. The ability of cells carrying BtuB in this state to grow with 5 μM CN-Cbl probably reflects the low-affinity entry of CN-Cbl by way of porin channels, since this growth is independent of production of BtuB or TonB proteins. In the third or suppressed state, bound CN-Cbl can be released into the periplasm but the transporter is incapable of further transport cycles and no more CN-Cbl can be taken up than there are BtuB proteins in the OM. We propose that interaction with TonB and hence the proper conformation of the Ton box is required both for release of CN-Cbl from BtuB and to allow BtuB to carry out repeated transport cycles.

The third aspect of these findings addresses the orientation specificity of the interaction of the Ton box and TonB. The most extensive disulfide cross-linking between transport-competent proteins occurred between BtuB positions 8, 10, and 12 and TonB positions 160, 162, and 163. Cysteines in adjacent residues cross-linked weakly, if at all. In all cases except TonB Q162C, cross-linking was stimulated by the presence of CN-Cbl. These cross-linking patterns extended our previous conclusion (8) that these protein segments approach each other in a highly oriented manner and that access of the Ton box to TonB is substantially increased when substrate is bound.

It has been suggested that the L8P or V10P mutations or the analogous changes in other transporters prevent interaction with TonB, based on the effect of the analogous mutants on stabilization of TonB (14) or on formaldehyde-mediated cross-linking (22). In contrast, TonB-BtuB disulfide cross-linking occurs even more strongly in these mutants, but the specific orientation of approach of these protein segments was markedly deranged. These results are not inconsistent with the other studies since TonB is certain to contact other parts of BtuB besides the Ton box. The misoriented contact between TonB and BtuB in the Ton box mutants may distort the other protein contacts so that the formaldehyde-linked residues are not in proximity and the contacts cannot stabilize TonB from proteolysis. There is no correlation between cross-linking pattern and the level of suppression provided in the various mutants, which reflects the situation that the suppression does not restore normal transport function. The interaction of TonB with the uncoupled form of the Ton box is still distorted, but the suppressor forms of BtuB or TonB must allow release of bound substrate although not recycling of the transport process.

The binding of substrate to the external face of the central domain changes the conformation and exposure of the Ton box, as indicated by the unfolding of helix 1 in FhuA and the extensive movement of the Ton box attachment region (25). The substrate binding-induced conformational change of the Ton box is indicated by the strong stimulation of BtuB D6C homodimer formation, of disulfide cross-linking to TonB, and of local residue mobility as measured by the electron paramagnetic resonance spin labeling (28). We conclude that the L8P and V10P substitutions do not prevent contact of BtuB and TonB but distort the orientation of the Ton box to prevent its highly oriented approach to TonB. These mutations prevent the proper folding of the Ton box into its usual immobilized conformation in the absence of substrate, as revealed by the high mobility of the spin probe attached to all BtuB Ton box residues when combined with the uncoupling mutations (C. H. Lin, K. A. Coggshall, N. Cadieux, R. J. Kadner, and D. S. Cafiso, unpublished data). These same mutations result in a general increase of cross-linking of BtuB and TonB positions that are normally nonreactive and in decreased cross-linking to normally reactive positions at the C-terminal sides of these regions. Future studies, particularly determination of the structure of these proteins, are needed to explain why cross-linking to the V10P-containing Ton box is independent of substrate, whereas cross-linking to the wild-type and L8P proteins is stimulated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the receipt of monoclonal antibody to TonB from K. Postle, without which this work could not be done, and helpful discussions with David Cafiso.

This research was supported by research grant GM19078 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and funds from the University of Virginia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anton M, Heller K J. The wild-type allele of tonB in Escherichia coli is dominant over the tonB1 allele, encoding TonBQ160K, which suppresses the btuB451 mutation. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;239:371–377. doi: 10.1007/BF00276935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassford P J, Jr, Kadner R J. Genetic analysis of components involved in vitamin B12 uptake in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1977;132:796–805. doi: 10.1128/jb.132.3.796-805.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell P E, Nau C D, Brown J T, Konisky J, Kadner R J. Genetic suppression demonstrates interaction of TonB protein with outer membrane transport proteins in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3826–3829. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3826-3829.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonhivers M, Ghazi A, Boulanger P, Letellier L. FhuA, a transporter of the Escherichia coli outer membrane, is converted into a channel upon binding of bacteriophage T5. EMBO J. 1996;15:1850–1856. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd D, Weiss D S, Chen J C, Beckwith J. Towards single-copy gene expression systems making gene cloning physiologically relevant: lambda InCh, a simple Escherichia coli plasmid-chromosome shuttle system. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:842–847. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.842-847.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradbeer C. The proton motive force drives the outer membrane transport of cobalamin in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3146–3150. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.3146-3150.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchanan S K, Smith B S, Venkatramani L, Xia D, Esser L, Palnitkar M, Chakraborty R, van der Helm D, Deisenhofer J. Crystal structure of the outer membrane active transporter FepA from Escherichia coli. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:56–63. doi: 10.1038/4931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadieux N, Kadner R J. Site-directed disulfide bonding reveals an interaction site between energy-coupling protein TonB and BtuB, the outer membrane cobalamin transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10673–10678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casadaban M J. Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in E. coli using bacteriophage transposons. J Mol Biol. 1976;104:541–555. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornelissen C N, Anderson J E, Sparling P F. Energy-dependent changes in the gonococcal transferrin receptor. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:25–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5381914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiGirolamo P M, Kadner R J, Bradbeer C. Isolation of vitamin B12 transport mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1971;106:751–757. doi: 10.1128/jb.106.3.751-757.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferguson A D, Hofmann E, Coulton J W, Diederichs K, Welte W. Siderophore-mediated iron transport: crystal structure of FhuA with bound lipopolysaccharide. Science. 1998;282:2215–2220. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gudmundsdottir A, Bell P E, Lundrigan M D, Bradbeer C, Kadner R J. Point mutations in a conserved region (TonB box) of Escherichia coli outer membrane protein BtuB affect vitamin B12 transport. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6526–6533. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6526-6533.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Günter K, Braun V. In vivo evidence for FhuA outer membrane receptor interaction with the TonB inner membrane protein of Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1990;274:85–88. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81335-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hancock R E W, Braun V. Nature of the energy requirement for the irreversible adsorption of bacteriophages T1 and φ80 to Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1976;125:409–415. doi: 10.1128/jb.125.2.409-415.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heller K, Kadner R J. Nucleotide sequence of the gene for the vitamin B12 receptor protein in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:904–908. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.3.904-908.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heller K J, Kadner R J, Gunther K. Suppression of the btuB451 mutation by mutations in the tonB gene suggests a direct interaction between TonB and TonB-dependent receptor proteins in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1988;64:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90488-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higuchi R, Krummel B, Saiki R K. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7351–7367. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.15.7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadner R J. Vitamin B12 transport in Escherichia coli: energy coupling between membranes. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:2027–2033. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klebba P E, Newton S M C. Mechanisms of solute transport through outer membrane porins: burning down the house. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1:238–248. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsen R A, Foster-Hartnett D, McIntosh M A, Postle K. Regions of Escherichia coli TonB and FepA proteins essential for in vivo physical interactions. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3213–3221. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3213-3221.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Letain T E, Postle K. TonB protein appears to transduce energy by shuttling between the cytoplasmic membrane and the outer membrane in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:271–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3331703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Link A J, Phillips D, Church G M. Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: application to open reading frame characterization. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6228–6237. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6228-6237.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Locher K P, Rees B, Koebnik R, Mitschler A, Moulinier L, Rosenbusch J P, Moras D. Transmembrane signaling across the ligand-gated FhuA receptor: crystal structures of free and ferrichrome-bound states reveal allosteric changes. Cell. 1998;95:771–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Locher K P, Rosenbusch J P. Modeling ligand-gated receptor activity. FhuA-mediated ferrichrome efflux from lipid vesicles triggered by phage T5. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1448–1451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez E, Bartolome B, de la Cruz F. pACYC184-derived cloning vectors containing the multiple cloning site and lacZ alpha reporter gene of pUC8/9 and pUC18/19 plasmids. Gene. 1988;68:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90608-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merianos H J, Cadieux N, Lin C H, Kadner R J, Cafiso D S. Substrate-induced exposure of an energy-coupling motif of a membrane transporter. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:205–209. doi: 10.1038/73309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moeck G S, Coulton J W. TonB-dependent iron acquisition: mechanisms of siderophore-mediated active transport. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:675–681. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moeck G S, Coulton J W, Postle K. Cell envelope signaling in Escherichia coli. Ligand binding to the ferrichrome-iron receptor FhuA promotes interaction with the energy-transducing protein TonB. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28391–28397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Postle K. Active transport by customized β-barrels. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:3–6. doi: 10.1038/4869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pressler U, Staudenmaier H, Zimmermann L, Braun V. Genetics of the iron dicitrate transport system of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2716–2724. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2716-2724.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reynolds P R, Mottur G P, Bradbeer C. Transport of vitamin B12 in Escherichia coli. Some observations on the roles of the gene products of btuC and tonB. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:4313–4319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roof S K, Allard J D, Bertrand K P, Postle K. Analysis of Escherichia coli TonB membrane topology using PhoA fusions. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5554–5557. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5554-5557.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sauer M, Hantke K, Braun V. Sequence of the fhuE outer-membrane receptor gene of Escherichia coli K12 and properties of mutants. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:427–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoffler H, Braun V. Transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli via the FhuA receptor is regulated by the TonB protein of the cytoplasmic membrane. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;217:378–383. doi: 10.1007/BF02464907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skare J T, Ahmer B M M, Seachord C L, Darveau R P, Postle K. Energy transduction between membranes. TonB, a cytoplasmic membrane protein, can be chemically cross-linked in vivo to the outer membrane receptor FepA. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16302–16308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Towbin H, Staehlin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]