Abstract

Besides the massive gene transfer from organelles to the nuclear genomes, which occurred during the early evolution of eukaryote lineages, the importance of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) in eukaryotes remains controversial. Yet, increasing amounts of genomic data reveal many cases of bacterium-to-eukaryote HGT that likely represent a significant force in adaptive evolution of eukaryotic species. However, DNA transfer involved in genetic transformation of plants by Agrobacterium species has traditionally been considered as the unique example of natural DNA transfer and integration into eukaryotic genomes. Recent discoveries indicate that the repertoire of donor bacterial species and of recipient eukaryotic hosts potentially are much wider than previously thought, including donor bacterial species, such as plant symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria (e.g., Rhizobium etli) and animal bacterial pathogens (e.g., Bartonella henselae, Helicobacter pylori), and recipient species from virtually all eukaryotic clades. Here, we review the molecular pathways and potential mechanisms of these trans-kingdom HGT events and discuss their utilization in biotechnology and research.

Keywords: Horizontal gene transfer, Agrobacterium, Bacterium-to-eukaryote HGT, Type IV secretion system

1. Introduction

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) among bacterial species (Beiko et al. 2005; Gogarten and Townsend 2005; Koonin et al. 2001) represents a mechanism that dominates evolution of prokaryotic life and is essential for the survival of microbial populations (Koonin 2016). In contrast to the genetic promiscuity observed among prokaryotes, the importance of HGT from bacteria to eukaryotes in evolution is still debated. The transfer of many genes from the genomes of bacterial endosymbiont-derived organelles, i.e., mitochondria or plastids, to their eukaryotic hosts is well-documented (Archibald 2015). These episodes of massive gene transfer took place in the early evolution of eukaryotic cells and are usually referred to as endosymbiotic gene transfer (EGT) or organelle gene transfer (OGT; Huang 2013). Understanding the relative importance of continued HGT from non-organelle bacteria during the evolution of eukaryotes still requires more investigation. For example, whereas a recent study suggests that events of bacterium-to-eukaryote HGT did not lead to an accumulation of transferred genes in modern eukaryotes (Ku et al. 2015), an increasing number of reported cases of HGT argues for an important role in adaptive evolution (Fitzpatrick 2012; Husnik and McCutcheon 2018; Lacroix and Citovsky 2016; Schönknecht et al. 2014; Sieber et al. 2017). In the early stages of eukaryote evolution, the pool of genes of prokaryotes was likely much larger than that of eukaryotes. Thus, acquisition of genes from organelles might reflect the role of endosymbiosis as a way to acquire new genes (Fournier et al. 2009). Besides the HGT events revealed by analyses of genomic sequences of eukaryotes, DNA transfer from Agrobacterium spp. to their host plant cells represents a rare example of HGT frequently occurring in the natural world at present day. Accumulated knowledge of the mechanisms involved in this naturally occurring bacterium-to-eukaryote HGT is essential to understand general molecular pathways of bacterial DNA transfer and integration into the eukaryotic host cell genome. In this chapter, we will review the pathways and the genomic signatures of trans-kingdom HGT, with a focus on its likely mechanisms and their utilization in biotechnology and research.

2. Pathways for Bacterium-to-Eukaryote HGT

Three different pathways for lateral DNA exchange between bacteria have been identified and well characterized: transformation, transduction, and conjugation (Arber 2014; Johnsborg et al. 2007). Transformation relies on the uptake of free DNA segments present in the environment. Transduction, mediated by bacteriophages, may occur as restricted transduction (i.e., only the bacteriophage sequence and small adjacent sequences are transferred) or as generalized transduction (i.e., larger sequences from the bacterial genome are co-transferred with the phage). Conjugation, or plasmid-mediated transfer, usually requires close cell-to-cell contact between the donor and recipient cells and relies on the activity of complex secretion machinery. Theoretically, bacterium-to-eukaryote HGT may occur via any of these three pathways. In eukaryotic cells, however, the nuclear envelope, which acts as a physical barrier to invading nucleic acid molecules, makes the acquisition of foreign DNA more complex than in prokaryotic cells. Indeed, once the transferred DNA segment enters the cell cytoplasm, it must be transported into the nucleus and then find its way through the highly structured and packaged host chromatin toward a potential site of integration. It is unlikely that a macromolecule the size of a natural DNA segment encoding protein functions could diffuse freely in the crowded environment of a eukaryotic cell cytoplasm. Moreover, DNA molecules usually are too large to traffic passively through the nuclear pore complex (NPC); the molecular size for such diffusion is thought to be about 9 nm (Forbes 1992), and the passage of larger molecules requires active nuclear import. Thus, nuclear import of foreign DNA most likely depends on the host import machinery. Similarly, after the entry of the foreign DNA into the nucleus, the incoming DNA molecule must be guided to a potential site of integration in the host chromatin, unless it functions as a self-replicating element, such as a plasmid. In some instances, gene delivery to the nucleus may follow the break-down of the nuclear membrane during mitosis, but this strategy is not effective in quiescent, non-dividing cells.

2.1. Transformation

Natural transformation, i.e., the uptake of free DNA segments, is observed in many different bacterial species (Johnsborg et al. 2007). In eukaryotic cells, several laboratory techniques are available to introduce free DNA into the cells via mechanical or chemical treatments. Such transformation protocols may lead to transient expression of the transgenes and to generation of stably transformed cells/organisms, thus demonstrating the possibility of acquisition and integration of free DNA segments by eukaryotic cells. However, it is generally considered that this pathway of DNA transfer to eukaryotic cells does not occur naturally. Although recent studies suggest that natural competence for exogenous DNA uptake does exist in yeast (Mitrikeski 2013), additional research is needed to assess the extent of this DNA acquisition pathway.

2.2. Transduction

Another possible pathway of DNA transfer from bacteria to eukaryotes is transfer via DNA replicating elements such as transposons, phages, and viruses. Exchange of genetic information via bacteriophages is well-documented between different bacterial species that are closely related as well as evolutionarily distant. Whereas phages or viruses able to cross-kingdom boundaries have not been identified so far, the analysis of sequences of bacterial origin in eukaryotic genomes has shown potential signatures of bacteriophage-mediated DNA transfer, for example, in the case of HGT from the intracellular pathogen Wolbachia spp. to its host Aedes aegypti (Klasson et al. 2009). Specifically, it has been suggested that giant viruses might mediate the transfer of genetic information from bacteria to eukaryotic cells (Schönknecht et al. 2013).

2.3. Conjugation

To date, trans-kingdom conjugation via a type IV secretion system (T4SS) remains the only demonstrated pathway of DNA transfer from bacteria to eukaryotic cells (Table 1). T4SSs are molecular machines specialized in the transport of macromolecules, proteins, and DNA, between bacteria and from bacteria to a variety of eukaryotic hosts. T4SSs are widespread among eubacteria (Alvarez-Martinez and Christie 2009; Maindola et al. 2014); originally, they were described in gram-negative bacterial species, although similar systems also exist in gram-positive bacteria (Goessweiner-Mohr et al. 2013). Generally, bacterial T4SSs are involved in the intercellular transport of macromolecules that fulfill many different functions in the host cell. Conjugation allows the exchange of genetic information between bacterial cells from the same or a related species via the transfer of plasmid or conjugative transposon DNA in the form of a nucleoprotein. Besides bacterial conjugation, T4SSs mediate the transport of macromolecules, proteins, or nucleoprotein complexes, from bacterial to eukaryotic cells. In many cases, T4SS-mediated transport plays a crucial role in the natural, pathogenic, or symbiotic interactions between bacterial cells and their eukaryotic hosts. For instance, effector proteins are transported from several animal prokaryotic pathogens to the host cells (Backert and Meyer 2006). This transport is exemplified by the facultative intracellular pathogen Brucella spp., which translocates several proteins that interfere with host functions, e.g., apoptosis inhibition or F-actin modulation, and facilitate infection (Siamer and Dehio 2015). Similarly, two human pathogens, Helicobacter pylori (Backert and Selbach 2008) and Legionella pneumonia (Hubber and Roy 2010), rely on their T4SS to translocate effector proteins into their hosts. Symbiotic plant-associated Mesorhizobium loti might also transfer proteins to host cells in a T4SS-dependent manner (Hubber et al. 2004). Finally, several species of the Agrobacterium genus naturally transfer DNA and proteins to many different species of plant hosts, resulting in the genetic transformation of the host cell. In nature, most potential Agrobacterium host species belong to several families of dicotyledonous plants (Gelvin 2010; Lacroix and Citovsky 2013), and the transferred DNA leads to uncontrolled cell division (tumors), and production of opines (small molecules used as carbon and nitrogen sources by Agrobacterium cells; Escobar and Dandekar 2003). Agrobacterium-mediated T-DNA transfer represents the most extensively studied example of HGT; a current model of its molecular mechanism is described in Fig. 1. Under laboratory conditions, using various plant tissue culture techniques and exogenously added enhancers of Agrobacterium virulence, virtually all plant species, including monocotyledonous plants, are amenable to genetic transformation by Agrobacterium, albeit often with low efficiency. Moreover, DNA transfer from Agrobacterium was also demonstrated toward non-plant species. Indeed, yeast (Bundock et al. 1995; Piers et al. 1996), other fungi (Bundock et al. 1999; de Groot et al. 1998; Gouka et al. 1999), sea urchin (Bulgakov et al. 2006), and cultured animal cells (Kunik et al. 2001; Machado-Ferreira et al. 2015) were shown to be recipients of Agrobacterium-mediated DNA transfer under laboratory conditions (Lacroix et al. 2006), with variable efficiencies.

Table 1.

DNA transfer from bacteria to eukaryotes in natural and artificial systems

| Bacterial donor | Eukaryotic recipient | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | Most plant species | Lacroix et al. (2006) |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Bundock et al. (1995), Piers et al. (1996) | |

| Penicillium | de Groot et al. (1998) | |

| Other fungi | Lacroix et al. (2006), Soltani et al. (2008) | |

| Insect cells | Machado-Ferreira et al. (2015) | |

| Sea urchin | Bulgakov et al. (2006) | |

| Human cells in culture | Kunik et al. (2001) | |

| Rhizobium trifolii Phyllobacterium myrsinacearum | Tobacco | Hooykaas et al. (1977) |

| Rhizobium sp. NGR234 Sinorhizobium meliloti Rhizobium loti | Tobacco | Broothaerts et al. (2005), Wendt et al. (2011) |

| Ensifer adhaerens | Tobacco, rice | Wendt et al. (2012), Zuniga-Soto et al. (2015) |

| Rhizobium etli | Tobacco | Lacroix and Citovsky (2016), Wang et al. (2017) |

| Escherichia coli | Saccharomyces | Heinemann and Sprague (1989) |

| Other fungi | Hayman and Bolen (1993), Inomata et al. (1994) | |

| Human cells in culture | Waters (2001) | |

| Bartonella henselae | Endothelial human cells in culture | Fernández-González et al. (2011), Schröder et al. (2011) |

| Helicobacter pylori | Human cells in culture | Varga et al. (2016) |

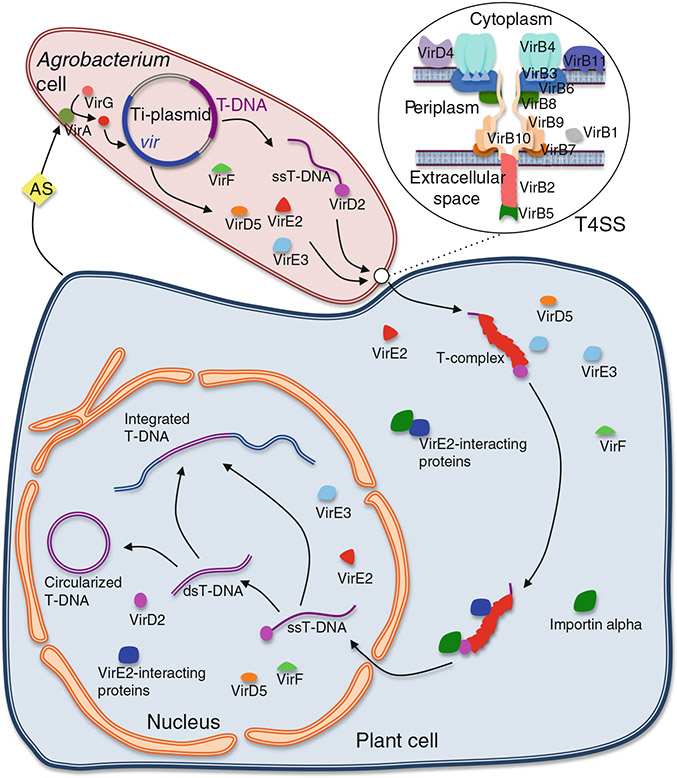

Fig. 1.

Summary of the molecular mechanism of T-DNA transfer from Agrobacterium to plant cells. More details and most references may be found in several extensive reviews (Gelvin 2003; Lacroix and Citovsky 2013). Upon wounding of plant tissues, plant-produced small phenolic signals (e.g., acetosyringone, AS) activate the VirA sensor, which in turn activates the VirG transcriptional inducer by phosphorylation. Phosphorylated VirG recognizes regulatory elements (vir boxes) in different vir gene promoters on the Ti (tumor-inducing) plasmid and induces their expression. The Vir proteins then initiate the transfer of DNA. VirD2 and VirD1 generate the single-stranded (ss) T-DNA (corresponding to the sequence element between the two 25-bp left and right T-DNA borders) from the Ti plasmid via a strand-replacement mechanism, and the VirD2 endonuclease remains covalently attached to the 5’ end of the T-DNA molecule. T4SS composed of the protein products of the virB operon and of VirD4 assembles at the membrane and mediates the export of the nucleoprotein complex VirD2-T-DNA as well as vir gene-encoded effector proteins VirD5, VirE2, VirE3, and VirF out of the bacterial cell and into the host cell cytoplasm. Noteworthy, the mechanism of passage of these macromolecules through the host cell barriers is not understood. In the host cell cytoplasm, molecules of the ssDNA-binding protein VirE2 likely associate with the ssT-DNA, forming the T-complex. Intracellular transport and nuclear import of the T-complex rely on its interactions with bacterial effectors and host factors such as cytoskeletal elements, VirE2-interacting proteins, and importin alpha proteins. Once the T-DNA enters the cell nucleus, it is uncoated from its associated proteins, most likely with the help of the bacterial F-box protein effector VirF and the host ubiquitin/proteasome system. Following uncoating, several scenarios are possible. The T-DNA may ligate into a genomic double-stranded DNA break (DSB) as a single-stranded molecule presumably via the action of a DNA polymerase theta-like enzyme (van Kregten et al. 2016), or be converted into a double-stranded form before integration into DSBs via one of the host’s DSB repair pathways. In some hosts, such as yeast cells, double-stranded T-DNA may also circularize and form a plasmid able to replicate

On the bacterial side, the repertoire of potential donor species for DNA transfer to eukaryotic cells can also be expanded beyond Agrobacterium spp. Indeed, several species belonging to the Rhizobiales order (which includes Agrobacterium spp. and many species involved in symbiotic interactions with plants that result in fixation of nitrogen) can mediate DNA transfer to plant cells when they are provided with plasmid(s) containing the machinery for DNA transfer (virulence region) and the sequence to be transferred (T-DNA) from a virulent species of Agrobacterium. For example, Rhizobium trifolii became virulent, i.e., able to induce tumors on several plant species, after conjugative transfer of the Ti plasmid from Agrobacterium (Hooykaas et al. 1977). Then, several other Rhizobiaceae species (i.e., R. leguminosarum, R. trifolii, and Phyllobacterium myrsinacearum) displayed the ability to transfer T-DNA to Arabidopsis, tobacco, and rice after being transformed with two plasmids: a helper plasmid that carries the virulence (vir) region and a binary plasmid that carries the T-DNA (Broothaerts et al. 2005). Introduction of a similar set of plasmids into Sinorhizobium meliloti, Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234, and Mesorhizobium loti conferred onto these bacteria the ability to genetically transform potato plants (Wendt et al. 2011). More recently, Ensifer adhaerens (also known as Sinorhizobium adhearens) was used to transfer DNA to potato and rice plants after introduction of a plasmid containing both vir and T-DNA regions of Agrobacterium (Wendt et al. 2012; Zuniga-Soto et al. 2015).

Lacroix and Citovsky (2016) recently reported that R. etli harbors a plasmid with a vir region highly similar to that encoded by Agrobacterium and that this bacterium was able to mediate plant genetic transformation when a plasmid carrying a T-DNA sequence was provided to the bacterial cell. Unlike the examples described above, where the vir region had to be supplied to the different Rhizobiales strains to render them virulent, R. etli harbors a complete and functional plant genetic transformation machinery in its p42a plasmid. Moreover, the transcriptional regulation of vir genes in R. etli overall is similar to that in Agrobacterium (Wang et al. 2017), with a few minor differences. For example, the R. etli virB2 gene, located outside of the virB operon, showed almost no activation upon acetosyringone treatment, which may partially explain the lower level of virulence of R. etli compared to A. tumefaciens. Among several other Rhizobiales strains that possess genes sharing homology with the Agrobacterium vir genes, none contain close homologs of all the vir genes essential for T-DNA transfer (i.e., virA, virB1 to virB11, virC, virD1, virD2, virD4, virE1, virE2, and virG). However, the presence of vir gene homologs in many bacterial species might represent the remnants of more widely spread systems of DNA transfer. Although no sequences similar to Agrobacterium T-DNA were detected in the R. etli genome, it is clear that HGT to plant cells can be mediated by a non-Agrobacterium species carrying its own virulence system.

In addition, E. coli was reported to mediate the transfer of plasmid DNA to eukaryotic host cells via a T4SS-dependent mechanism. Initially, plasmid transfer to Saccharomyces cerevisiae was demonstrated via a mechanism that shares essential features with bacterial conjugation (Heinemann and Sprague 1989): the requirement for close cell-to-cell contact and for the mob and oriT functions of the conjugative DNA transfer. Other yeast species, such as Kluyveromyces lactis and Pichia angusta or S. kluyveri, can be recipients of DNA transfer from E. coli (Hayman and Bolen 1993; Inomata et al. 1994). Furthermore, E. coli was able to transfer DNA to other types of eukaryotic cells, such as human cells in culture (Waters 2001) and diatoms, a type of unicellular algae (Karas et al. 2015). Another bacterial species, Bartonella henselae, could mediate the transfer of plasmid DNA to endothelial human cells in vitro via a mechanism related to conjugation (Fernández-González et al. 2011; Schröder et al. 2011). B. henselae is a facultative intracellular human pathogen, known to transfer effector proteins into its host cells via a T4SS-dependent mechanism during the infection process (Siamer and Dehio 2015). In these two studies (Fernández-González et al. 2011; Schröder et al. 2011), different plasmids, a modified cryptic plasmid or R388 plasmid derivatives, were transferred from B. henselae to their host cells, resulting in stable transgenic human cell lines, which signifies that the transferred DNA was integrated in the host cell genome. A functional T4SS was essential to the transfer, as B. henselae strains mutated in the virB region that encodes T4SS were unable to mediate DNA transfer. Unlike genetic transformation by Agrobacterium and R. etli, host cell division was required for B. henselae transgene expression, suggesting that transport of transferred DNA from B. henselae into the host cell nucleus relies on the disruption of the host nuclear envelope rather than on the host nuclear import machinery. Recently, it was shown that another human bacterial pathogen, Helicobacter pylori, known as a risk factor for gastric cancer, may translocate to its host cells not only its effector proteins but also DNA molecules that are recognized by an intracellular receptor TLR9 (Varga et al. 2016). The nature of the transported H. pylori DNA and its fate in the host cell, however, remain unknown. Another indication of bacterium-to-human cell DNA transfer comes from analyses of the genome sequences of human tumors, in which integrated bacterial DNA was detected (Riley et al. 2013; Sieber et al. 2016). These analyses could not be performed in non-tumor cells because it is next to impossible to detect HGT reliably in a single cell genome, whereas tumors represent clones of a single cell, allowing such studies.

The data summarized here indicate that HGT mediated by a conjugation-like mechanism is not restricted to Agrobacterium spp. and their host plants, and it likely occurs in other instances. Interestingly, however, except for Agrobacterium, no demonstrated roles for DNA transfer in infection, symbiosis, or cancer induction have been identified so far for the eukaryote-associated bacterial species that may transfer DNA to their host cells.

3. Stable and Transient HGT

Regardless of the molecular mechanisms of HGT, one approach to assess its importance and relevance for evolution is to investigate the presence of sequences from bacterial origin in eukaryotic genomes (see next section). It is important to mention, however, that formation of these signatures of the bacterium-to-eukaryote HGT requires several additional molecular reactions following the initial transport of DNA from the bacterial cell to the host cell cytoplasm. Indeed, fixation of bacterial sequences in a eukaryotic genome and their vertical transmission do not depend merely on the ability of the bacterial donor species to transfer a DNA segment to a eukaryotic cell. The accumulated knowledge of the molecular pathways of Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation (Gelvin 2003, 2017; Lacroix and Citovsky 2013) provides us with precious clues on the steps required for expression of the transferred DNA and its integration into the host genome, which represent two distinct processes. In fact, DNA may be imported into the host nucleus, and the genes it carries may be expressed without actual integration in the genomic DNA. This phenomenon is well known during plant genetic transformation and is termed transient expression of the transgene. Only a fraction of transiently expressed DNA undergoes integration, and this DNA mediates what is termed stable expression of the transgene. Integration of the transferred DNA is necessary, but not sufficient for production of a transgenic organism. First, even if the transferred DNA was integrated into the genome of the target cell, it still must be conserved through rearrangements of the genome during subsequent cell divisions. Second, the transformed cell must be of a type that will regenerate into a fully functional and fertile organism. In the case of unicellular eukaryotes and most fungi, for which at least a part of the cell cycle is in the unicellular form, genes acquired by cells in this unicellular stage may be transmitted to the progeny by simple cell division. For plants, cells from many tissues can dedifferentiate and regenerate into a functional organism under appropriate conditions; a transformed cell may thus regenerate into an organism carrying the transforming DNA, i.e., a genetically modified organism. For most animals, the transgene may be transmitted to the progeny only if the target cell is a germline cell, with the exception of sessile organisms that do not possess dedicated germline cells, e.g., some marine organisms (Degnan 2014). Finally, the transgene must be transmitted through generations and conserved during evolution of the surviving transgenic line. Obviously, the conservation of a sequence of bacterial origin is more likely if it confers a selective advantage or is at least neutral for the recipient, or confers an advantage to the DNA segment itself in the case of a selfish DNA element. The consequence of these multiple steps is that the HGT event signatures identified by analyzing genome sequences likely resulted from a much higher frequency of initial gene transfer from bacteria to eukaryotes that did not lead to integration and fixation of the transferred sequences in the progeny of the original recipient. The possibility of gene transfer and transient expression without integration in the host genome also raises the question of a potential role of this phenomenon as a strategy to express bacterium-encoded effector proteins in the host cell, providing an alternative to the direct introduction of the effector proteins via T3SS or T4SS pathways and further facilitating infection. Indeed, in the case of Agrobacterium, expression of T-DNA genes very early after inoculation, presumably before integration, leads to changes in the host cell that facilitate subsequent development of a tumor (Lee et al. 2009). In this scenario, the transferred genes, similarly to the Agrobacterium T-DNA genes, would harbor regulatory sequences compatible with expression in eukaryotic cells.

4. HGT Signatures in Eukaryotic Genomes

Based on the examples of DNA transfer in natural and experimental systems described above, it appears that HGT is possible from many bacterial species to cells of organisms belonging to virtually all clades of eukaryotes. Indeed, genomic signatures of bacterium-to-eukaryote HGT have been found in many organisms (Table 2). Based on these examples, it is possible to outline general conditions required for the bacterium-to-eukaryote gene transfer. Most important is the close interaction between the bacterial donor and eukaryotic recipient cells: at the minimum a shared habitat, and sometimes cell-surface attachment or even intracellular location of the donor bacteria. The close association between donor and recipient cells must be concomitant with the HGT occurrence. Thus, when considering the signature of ancient HGT, one must also consider the interactions that may have taken place between ancestors of the involved species. Interestingly, among the donor bacterial species at the origin of HGT into eukaryotes, a higher proportion of proteobacteria and cyanobacteria is found (Le et al. 2014); consistently, the most common endosymbionts and closely eukaryote-associated bacteria belong to these families (Huang 2013).

Table 2.

Genomic signatures of bacterium-to-eukaryote HGT

| Bacterial donor | Eukaryotic recipient |

Transferred sequences | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unknown | Colletotrichum spp. | 11 genes involved in interaction with plants | Jaramillo et al. (2015) |

| Proteobacteria | Verticillium spp. | Glucan glycosyltransferase | Klosterman et al. (2011) |

| Thermoacidophilic bacteria | Galdieria sulphuraria | Several genes facilitating ecological adaptation | Schönknecht et al. (2013) |

| Unknown | Dictyostelium discoideum | 18 genes, some encoding functional proteins | Eichinger et al. (2005) |

| Unknown | Blastocystis spp. | Up to 2.5% of the genes | Eme et al. (2017) |

| Agrobacterium rhizogenes | Nicotiana glauca | T-DNA genes | Aoki et al. (1994, White et al. (1983) |

| Nicotiana spp. | T-DNA genes | Furner et al. (1986), Intrieri and Buiatti (2001) | |

| Linaria spp. | T-DNA genes | Matveeva et al. (2012) | |

| Ipomea batatas | T-DNA genes | Kyndt et al. (2015) | |

| Unknown | Arabidopsis thaliana | Genes for xylem formation, defense, growth regulation | Yue et al. (2012) |

| Actinobacteria | Land plants | Transaldolase | Yang et al. (2015) |

| Unknown | Land plants | Auxin biosynthesis pathway | Yue et al. (2014) |

| Unknown | Most land plants | Glycerol transporter | Zardoya et al. (2002) |

| Alpha-proteobacteria | Most land plants | Gamma-glutamylcysteine ligase, glutathione synthesis | Copley and Dhillon (2002) |

| Unknown | Most land plants | DNA-3-methyladenine glycosylase (DNA repair) | Fang et al. (2017) |

| Unknown | Hydra magnipapillata | Unknown | Chapman et al. (2010) |

| Unknown | Bdelloid rotifers | Unknown | Gladyshev et al. (2008) |

| Wolbachia spp. | Arthropods (8 species) | Large sequences (up to 30% of the bacterial genome) | Dunning Hotopp et al. (2007) |

| Rhizobiales | Plant-parasitic nematodes | Multiple genes (e.g., invertase) | Danchin et al. (2016) |

| Bacillus spp. | Hypothenemus hampei | Mannanase (HhMAN1) | Chapman et al. (2010) |

Usually, the first hint for detecting an HGT event is the unexpected phyletic distribution of a sequence that differs from the known species phylogenetic tree. Indeed, a topological discrepancy between the known species tree and the predicted gene tree represents a good indication that a sequence was acquired via HGT (Fitzpatrick 2012; Koonin et al. 2001; Syvanen 2012). Nevertheless, it cannot be excluded that the presence of a sequence only in one species of a clade is due to differential gene loss in all other species. Thus, to confirm that the presence of an unexpected sequence is due to HGT, several secondary clues must be taken into account. Such auxiliary evidence includes base composition, codon usage, presence or absence of introns, synteny analysis, and a certain level of ecological association between the species involved, e.g., shared niche or habitat or closer physical association. Claims of HGT events from bacteria to eukaryotes must be examined carefully. Indeed, several publications that reported large numbers of genes acquired from bacterial donors via HGT have been later contested because of insufficiently stringent criteria for identification of HGT-derived genes or because of possible contaminations of the sequenced DNA. For example, the human genome was reported to contain many HGT-derived genes (Lander et al. 2001), but subsequent phylogenetic studies including a larger number of eukaryotic species contested this initial finding (Crisp et al. 2015; Stanhope et al. 2001). Similarly, the discovery of a large fraction of HGT-acquired genes in a tardigrade Hypsibius dujardini genome (Boothby et al. 2015) was likely the result of contamination by bacterial DNA (Koutsovoulos et al. 2016). However, the number of HGT signatures in eukaryotic genomes may also be underestimated for different reasons, such as an extinct donor bacterium or a large number of mutations in the transferred gene, which may prevent the identification of the bacterial origin of these genes (Degnan 2014; Sieber et al. 2017).

The early evolution of eukaryote lineages was marked by events of vast transfer of genetic information from intracellular organelles of bacterial origin, i.e., plastids and mitochondria, to their host cells. Indeed, acquisition of genes from these organelles by the nuclear genome represents major and most evolutionary significant transfer of genetic information from bacterial to eukaryotic genomes (Archibald 2015). The mechanism of these HGT events is unknown; however, gene transfer from chloroplasts to nuclear genome was measured experimentally at significant rates (Huang et al. 2003; Stegemann et al. 2003). Note that, in some cases, genes had been acquired by eukaryotic cells from different bacterial sources to compensate for the loss of the corresponding functions in their organelles (e.g., Nowack et al. 2016), which has been described as maintenance HGT (Husnik and McCutcheon 2018). Besides the gene transfer that originated from permanent organelles, the acquisition of bacterial genes was demonstrated in several instances (see Table 2) and played an important role in the adaptive evolution of eukaryotes.

Eukaryotic species displaying a predominant unicellular stage in their life cycle, which include unicellular eukaryotes and most fungi, represent a favored target for HGT from bacteria because they do not need to dedifferentiate and regenerate as do multicellular organisms. The acquisition of genes from bacteria may have played an important role in evolution of many fungal species, particularly in the rhizosphere, where plant-associated bacteria and fungi live in close proximity to each other (Gardiner et al. 2013). Indeed, the adaptive evolution of plant-associated fungi is likely to be facilitated by the acquisition of bacterial genes, many of which encode factors involved in pathogenicity, niche specification, and adaptation to different metabolic requirement, via HGT (Fitzpatrick 2012). For example, sequencing of the genomes of three species of Colletotrichum, plant-pathogenic fungi responsible for a crop-destructive anthracnose disease, revealed at least 11 independent events of HGT from bacteria (Jaramillo et al. 2015). These transferred genes likely are important for niche adaptation because most of them encode proteins involved in interactions with the host plant or virulence. In two species of the Verticillum genus, the causative agent of vascular wilt in more than two hundred plant species, a gene encoding a glucan glycosyltransferase and playing a role in virulence via the synthesis of extracellular glucans, was also acquired by HGT from proteobacteria (Klosterman et al. 2011).

Genome sequencing of several unicellular eukaryotes also revealed genes from bacterial origin. For example, genes obtained from bacteria and archaea were found in the genome of Galdieria sulphuraria, a red alga living in hot, acidic, and heavy-metal-rich extreme environment. Taking into account duplication and diversification, these genes of suspected bacterial origin may represent up to 5% of all G. sulphuraria protein-encoding genes and encode proteins that may have helped the evolution of this species toward adaptation to extreme environments. Among these proteins is an arsenic membrane protein pump similar to those found in thermoacidophilic bacteria (Schönknecht et al. 2013). Similarly, 18 genes likely resulting from HGT from bacteria were found in the soil-living amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum genome. Some of these genes encoded proteins conferring a new function, such as a dipeptidase that may degrade bacterial cell walls (Eichinger et al. 2005). In genomes of several species of Blastocystis, parasites found notably in the human gut, up to 2.5% of the genes have been acquired through HGT mostly, i.e., 80%, from bacterial donors. Many of these genes appear to be functional and important for adaptation to the environment (Eme et al. 2017).

The first series of HGT events in plants was discovered in the genomes of several species as a result of T-DNA transfer from a donor bacterial species related to Agrobacterium rhizogenes. Based on the known biology of Agrobacterium-plant interactions, it is likely that the first step after T-DNA integration was the regeneration of a functional organism from dedifferentiated transformed cells induced by T-DNA gene expression, followed by vertical transmission via sexual reproduction (Matveeva and Lutova 2014). The presence of T-DNA genes acquired via HGT was first discovered in Nicotiana glauca (Aoki et al. 1994; White et al. 1983), and further studies showed that it could detected in many species of the Nicotiana genus (Furner et al. 1986; Intrieri and Buiatti 2001). Analysis of more than 100 dicotyledonous plant species detected the presence of T-DNA in the genomes of Linaria vulgaris and Linaria dalmatica (Matveeva et al. 2012; Matveeva and Lutova 2014). Recently, genome sequencing of several varieties of cultivated sweet potato Ipomea batatas revealed the presence of T-DNA sequences derived from HGT (Kyndt et al. 2015). Unlike most of the HGT events described in this section, signatures of Agrobacterium-to-plant HGT correspond to the rare case for which the transfer pathway is known and the source of transferred genes is clearly identified. Indeed, it was determined that all T-DNA sequences found in Nicotiana and Linaria originated from a mikimopine strain of A. rhizogenes, whereas in the case of I. batatas the donor bacterium was an ancestral form of A. rhizogenes. It is still unknown whether these T-DNA genes, which have been preserved during evolution and some of which are expressed at detectable levels, play a role in the plant biology. However, a recent analysis suggested that T-DNA genes acquired by HGT likely play a role in the recipient plant evolution, for example, by affecting root development (Quispe-Huamanquispe et al. 2017). A comparative genomic study of the early land plant Physcomitrella patens and of Arabidopsis thaliana suggested that several families of nuclear genes potentially originated from bacterium-to-plant HGT events (Yue et al. 2012). Because some of these genes were specific for land plant activities, such as growth regulation and xylem formation, these HGT events were suggested to be important for transition from aquatic to terrestrial environments. For example, the genes encoding a transaldolase enzyme found in many land plant species may have derived from an ancient event of HGT from an Actinobacterium to an ancestor of land plants (Yang et al. 2015). In addition, genes involved in several other pathways may have been acquired by HGT from bacteria. These include essential genes for auxin biosynthesis (Yue et al. 2014), a glycerol transporter (Zardoya et al. 2002), a gamma-glutamylcysteine ligase that catalyzes glutathione synthesis (Copley and Dhillon 2002), and a DNA-3-methyladenine glycosylase involved in base excision repair (Fang et al. 2017).

HGT from bacteria to animals has been confirmed in a limited number of cases, mostly invertebrates. These HGT events often originate from DNA transfer from unknown bacteria to asexual animals, i.e., sessile organisms able to regenerate into a functional organism by asexual reproduction, or from DNA transfer from endosymbiotic bacteria to their host germline cells (Dunning Hotopp 2011). Indeed, several freshwater asexual animals were recipients for HGT from bacteria, as in the case of the freshwater cnidarian Hydra magnipapillata (Chapman et al. 2010) and bdelloid rotifers (Gladyshev et al. 2008). Wolbachia, identified as donor of heritable HGT to their host arthropods or nematodes, are maternally inherited endosymbiotic bacteria transmitted through the egg cytoplasm. Eight out of 11 completely sequenced genomes of arthropods display Wolbachia sequences acquired via HGT, which may represent up to 30% of the recipient genome in some cases (Dunning Hotopp et al. 2007). Plant-parasitic nematodes have acquired several genes by HGT from bacteria, including a gene encoding an invertase, which is important for metabolism of host plant carbohydrates and likely originated from bacteria of the Rhizobiales order (Danchin et al. 2016). A major pest of coffee plants, Hypothenemus hampei, the coffee berry borer beetle, harbors a gene encoding a mannanase HhMAN1 protein that hydrolyzes the major coffee storage polysaccharide galactomannan and that most likely originated from a Bacillus gene (Acuña et al. 2012).

5. Bacterium-to-Eukaryote HGT as Tool for Research and Biotechnology

In plant research and biotechnology, Agrobacterium represents the major vector used for gene transfer. Since the first successful transformation and regeneration of tobacco transgenic plants in the early 1980s (Horsch et al. 1984), Agrobacterium has been used to genetically transform virtually all plant species for generation of transgenic organisms (Banta and Montenegro 2008). Whereas most plant species are susceptible to Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation (Lacroix et al. 2006), the efficiency of transgenic plant generation remains low for many of them. Agrobacterium-mediated DNA transfer is also used as an inexpensive and convenient method for transient gene expression in plant tissues allowing, for example, rapid evaluation of protein subcellular localization or promoter regulation (Krenek et al. 2015). Both transient expression and stable transformation are widely used in plant research for studies of gene function. The random nature of T-DNA insertion into the host plant genome has allowed generation of numerous collections of insertional mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana plants (Alonso et al. 2003), which represented a transformative advance in plant genomics research. New molecular tools allowing targeted genomic modifications, such as the CRISPR/Cas9 system, were also introduced into plants via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (Char et al. 2017). The many cases of bacterium-to-eukaryote HGT described in this chapter show that, at least under experimental conditions, the repertoire of bacterial donor cells and of eukaryote recipient cells is much wider than the mere cases of plant genetic transformation mediated by Agrobacterium spp. Since the discovery of genetic transformation of yeast and other fungi by Agrobacterium, Agrobacterium has also become the major tool for genetic modification and insertional mutagenesis of these organisms (Frandsen 2011). Potentially, protocols based on several other systems of gene transfer from bacterial to eukaryotic cells will be developed in the future. For example, the ability of other bacterial species, such as R. etli, to transform plants could be exploited with host species that are recalcitrant to Agrobacterium (Broothaerts et al. 2005; Lacroix and Citovsky 2016; Wendt et al. 2012). Moreover, it has been suggested that E. coli could be used as tool to transform yeast or other fungal cells (Moriguchi et al. 2016), whereas B. henselae could be used as tool to transform human cells (Llosa et al. 2012). As a potential application, B. henselae—or similar bacterial species such as H. pylori, engineered to transfer DNA to human cells—could be used as a vector for gene therapy (Elmer et al. 2013; Walker et al. 2017), which might be useful when other types of vectors are not usable or to avoid viral vectors that may inherently represent health risks.

6. Conclusions

HGT is known to occur from Agrobacterium spp. to their host plant cells during infection of plants by Agrobacterium, resulting in plant diseases such as tumors (termed crown galls) and hairy roots. Moreover, it is also known that sequences of bacterial origin and resulting from HGT are found in many eukaryotic genomes. These sequences most likely were derived from endosymbionts that produced permanent organelles as well as from non-organelle bacteria, often resulting in the acquisition of genes important for adaptive evolution. Recent studies have also shown that DNA transfer from various bacterial species to different eukaryotic cells may be performed under laboratory conditions. Consequently, it is likely that bacterium-to-eukaryote HGT occurs or has occurred among a wide variety of combinations of donor bacterial species and recipient eukaryotic species. Several compelling reasons exist for continuing research of these gene transfer systems: understanding the potential evolutionary and ecological significance of HGT, deciphering the pathways of transport and integration of the incoming bacterial DNA, and developing new tools for the use of HGT in fundamental and applied research.

Extensive studies of DNA transfer from Agrobacterium to its host cells have provided many invaluable insights in the mechanisms by which a segment of bacterial DNA can be transported into a eukaryotic host cell nucleus and integrated in its genome. Yet, numerous unanswered questions remain, many of which center on the largely unknown responses of the recipient cell to the donor DNA. For example, introduction of foreign DNA into a cell genome represents an aggressive act against the cell, and eukaryotic organisms may have evolved adapted responses to maintain the integrity of their genomes. Even when transferred DNA is not integrated, the products of expression of transiently transferred bacterial genes may act similarly to bacterial or viral effector proteins, also eliciting host defense responses.

Acknowledgements

The work in the VC laboratory is supported by grants from USDA/NIFA, NIH, NSF, and BARD to VC.

References

- Acuña R, Padilla BE, Flórez-Ramos CP et al. (2012) Adaptive horizontal transfer of a bacterial gene to an invasive insect pest of coffee. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:4197–4202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JM, Stepanova AN, Leisse TJ et al. (2003) Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301:653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Martinez CE, Christie PJ (2009) Biological diversity of prokaryotic type IV secretion systems. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73:775–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki S, Kawaoka A, Sekine M et al. (1994) Sequence of the cellular T-DNA in the untransformed genome of Nicotiana glauca that is homologous to ORFs 13 and 14 of the Ri plasmid and analysis of its expression in genetic tumours of N. glauca x N. langsdorffii. Mol Gen Genet 243:706–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber W (2014) Horizontal gene transfer among bacteria and its role in biological evolution. Life 4:217–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald JM (2015) Endosymbiosis and eukaryotic cell evolution. Curr Biol 25:R911–R921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backert S, Meyer TF (2006) Type IV secretion systems and their effectors in bacterial pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol 9:207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backert S, Selbach M (2008) Role of type IV secretion in Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol 10:1573–1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banta L, Montenegro M (2008) Agrobacterium and plant biotechnology. In: Tzfira T, Citovsky V (eds) Agrobacterium: from biology to biotechnology. Springer, New York, pp 72–147 [Google Scholar]

- Beiko RG, Harlow TJ, Ragan MA (2005) Highways of gene sharing in prokaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:14332–14337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothby TC, Tenlen JR, Smith FW et al. (2015) Evidence for extensive horizontal gene transfer from the draft genome of a tardigrade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:15976–15981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broothaerts W, Mitchell HJ, Weir B et al. (2005) Gene transfer to plants by diverse species of bacteria. Nature 433:629–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulgakov VP, Kiselev KV, Yakovlev KV et al. (2006) Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of sea urchin embryos. Biotechnol J 1:454–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundock P, den Dulk-Ras A, Beijersbergen A et al. (1995) Trans-kingdom T-DNA transfer from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J 14:3206–3214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundock P, Mroczek K, Winkler AA et al. (1999) T-DNA from Agrobacterium tumefaciens as an efficient tool for gene targeting in Kluyveromyces lactis. Mol Gen Genet 261:115–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JA, Kirkness EF, Simakov O et al. (2010) The dynamic genome of Hydra. Nature 464:592–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Char SN, Neelakandan AK, Nahampun H et al. (2017) An Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR/Cas9 system for high-frequency targeted mutagenesis in maize. Plant Biotechnol J 15:257–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copley SD, Dhillon JK (2002) Lateral gene transfer and parallel evolution in the history of glutathione biosynthesis genes. Genome Biol 3: research0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp A, Boschetti C, Perry M et al. (2015) Expression of multiple horizontally acquired genes is a hallmark of both vertebrate and invertebrate genomes. Genome Biol 16:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danchin EG, Guzeeva EA, Mantelin S et al. (2016) Horizontal gene transfer from bacteria has enabled the plant-parasitic nematode Globodera pallida to feed on host-derived sucrose. Mol Biol Evol 33:1571–1579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot MJ, Bundock P, Hooykaas PJJ et al. (1998) Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of filamentous fungi [published erratum appears in Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 1074 (1998)]. Nat Biotechnol 16:839–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan SM (2014) Think laterally: Horizontal gene transfer from symbiotic microbes may extend the phenotype of marine sessile hosts. Front Microbiol 5:638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning Hotopp JC (2011) Horizontal gene transfer between bacteria and animals. Trends Genet 27:157–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning Hotopp JC, Clark ME, Oliveira DC et al. (2007) Widespread lateral gene transfer from intracellular bacteria to multicellular eukaryotes. Science 317:1753–1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichinger L, Pachebat JA, Glöckner G et al. (2005) The genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature 435:43–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmer JJ, Christensen MD, Rege K (2013) Applying horizontal gene transfer phenomena to enhance non-viral gene therapy. J Control Release 172:246–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eme L, Gentekaki E, Curtis B et al. (2017) Lateral gene transfer in the adaptation of the anaerobic parasite blastocystis to the gut. Curr Biol 27:807–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar MA, Dandekar AM (2003) Agrobacterium tumefaciens as an agent of disease. Trends Plant Sci 8:380–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H, Huangfu L, Chen R et al. (2017) Ancestor of land plants acquired the DNA-3-methyladenine glycosylase (MAG) gene from bacteria through horizontal gene transfer. Sci Rep 7:9324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-González E, de Paz HD, Alperi A et al. (2011) Transfer of R388 derivatives by a pathogenesis-associated type IV secretion system into both bacteria and human cells. J Bacteriol 193:6257–6265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick DA (2012) Horizontal gene transfer in fungi. FEMS Microbiol Lett 329:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes DJ (1992) Structure and function of the nuclear pore complex. Annu Rev Cell Biol 8:495–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier GP, Huang J, Gogarten JP (2009) Horizontal gene transfer from extinct and extant lineages: biological innovation and the coral of life. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 364:2229–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frandsen RJ (2011) A guide to binary vectors and strategies for targeted genome modification in fungi using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation. J Microbiol Methods 87:247–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furner IJ, Huffman GA, Amasino RM et al. (1986) An Agrobacterium transformation in the evolution of the genus Nicotiana. Nature 319:422–427 [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner DM, Kazan K, Manners JM (2013) Cross-kingdom gene transfer facilitates the evolution of virulence in fungal pathogens. Plant Sci 210:151–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelvin SB (2003) Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation: the biology behind the “gene-jockeying” tool. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67:16–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelvin SB (2010) Plant proteins involved in Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation. Annu Rev Phytopathol 48:45–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelvin SB (2017) Integration of Agrobacterium T-DNA into the plant genome. Annu Rev Genet 51:195–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladyshev EA, Meselson M, Arkhipova IR (2008) Massive horizontal gene transfer in bdelloid rotifers. Science 320:1210–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goessweiner-Mohr N, Arends K, Keller W et al. (2013) Conjugative type IV secretion systems in gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid 70:289–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogarten JP, Townsend JP (2005) Horizontal gene transfer, genome innovation and evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:679–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouka RJ, Gerk C, Hooykaas PJJ et al. (1999) Transformation of Aspergillus awamori by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated homologous recombination. Nat Biotechnol 17:598–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman GT, Bolen PL (1993) Movement of shuttle plasmids from Escherichia coli into yeasts other than Saccharomyces cerevisiae using trans-kingdom conjugation. Plasmid 30:251–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann JA, Sprague JF Jr (1989) Bacterial conjugative plasmids mobilize DNA transfer between bacteria and yeast. Nature 340:205–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooykaas PJJ, Klapwijk PM, Nuti MP et al. (1977) Transfer of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid to avirulent Agrobacteria and to Rhizobium ex planta. J Gen Microbiol 98:477–484 [Google Scholar]

- Horsch RB, Fraley RT, Rogers SG et al. (1984) Inheritance of functional foreign genes in plants. Science 223:496–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CY, Ayliffe MA, Timmis JN (2003) Direct measurement of the transfer rate of chloroplast DNA into the nucleus. Nature 422:72–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J (2013) Horizontal gene transfer in eukaryotes: the weak-link model. BioEssays 35:868–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubber A, Roy CR (2010) Modulation of host cell function by Legionella pneumophila type IV effectors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 26:261–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubber A, Vergunst AC, Sullivan JT et al. (2004) Symbiotic phenotypes and translocated effector proteins of the Mesorhizobium loti strain R7A VirB/D4 type IV secretion system. Mol Microbiol 54:561–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husnik F, McCutcheon JP (2018) Functional horizontal gene transfer from bacteria to eukaryotes. Nat Rev Microbiol 16:67–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inomata K, Nishikawa M, Yoshida K (1994) The yeast Saccharomyces kluyveri as a recipient eukaryote in transkingdom conjugation: Behavior of transmitted plasmids in transconjugants. J Bacteriol 176:4770–4773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intrieri MC, Buiatti M (2001) The horizontal transfer of Agrobacterium rhizogenes genes and the evolution of the genus Nicotiana. Mol Phylogenet Evol 20:100–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo VD, Sukno SA, Thon MR (2015) Identification of horizontally transferred genes in the genus Colletotrichum reveals a steady tempo of bacterial to fungal gene transfer. BMC Genom 16:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsborg O, Eldholm V, Havarstein LS (2007) Natural genetic transformation: prevalence, mechanisms and function. Res Microbiol 158:767–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karas BJ, Diner RE, Lefebvre SC et al. (2015) Designer diatom episomes delivered by bacterial conjugation. Nat Commun 6:6925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasson L, Kambris Z, Cook PE et al. (2009) Horizontal gene transfer between Wolbachia and the mosquito Aedes aegypti. BMC Genom 10:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klosterman SJ, Subbarao KV, Kang S et al. (2011) Comparative genomics yields insights into niche adaptation of plant vascular wilt pathogens. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin EV (2016) Horizontal gene transfer: essentiality and evolvability in prokaryotes, and roles in evolutionary transition. F1000 Res 5 1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Aravind L (2001) Horizontal gene transfer in prokaryotes: Quantification and classification. Annu Rev Microbiol 55:709–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsovoulos G, Kumar S, Laetsch DR et al. (2016) No evidence for extensive horizontal gene transfer in the genome of the tardigrade Hypsibius dujardini. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:5053–5058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenek P, Samajova O, Luptovciak I et al. (2015) Transient plant transformation mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens: principles, methods and applications. Biotechnol Adv 33:1024–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku C, Nelson-Sathi S, Roettger M et al. (2015) Endosymbiotic origin and differential loss of eukaryotic genes. Nature 524:427–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunik T, Tzfira T, Kapulnik Y et al. (2001) Genetic transformation of HeLa cells by Agrobacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:1871–1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyndt T, Quispe D, Zhai H et al. (2015) The genome of cultivated sweet potato contains Agrobacterium T-DNAs with expressed genes: An example of a naturally transgenic food crop. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:5844–5849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix B, Citovsky V (2013) The roles of bacterial and host plant factors in Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation. Int J Dev Biol 57:467–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix B, Citovsky V (2016) A functional bacterium-to-plant DNA transfer machinery of Rhizobium etli. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix B, Tzfira T, Vainstein A et al. (2006) A case of promiscuity: Agrobacterium’s endless hunt for new partners. Trends Genet 22:29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES, Consortium IHGS, Linton LM et al. (2001) Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409:860–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le PT, Pontarotti P, Raoult D (2014) Alphaproteobacteria species as a source and target of lateral sequence transfers. Trends Microbiol 22:147–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CW, Efetova M, Engelmann JC et al. (2009) Agrobacterium tumefaciens promotes tumor induction by modulating pathogen defense in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 21:2948–2962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llosa M, Schröder G, Dehio C (2012) New perspectives into bacterial DNA transfer to human cells. Trends Microbiol 20:355–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado-Ferreira E, Balsemño-Pires E, Dietrich G et al. (2015) Transgene expression in tick cells using Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Exp Appl Acarol 67:269–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maindola P, Raina R, Goyal P et al. (2014) Multiple enzymatic activities of ParB/Srx superfamily mediate sexual conflict among conjugative plasmids. Nat Commun 5:5322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matveeva TV, Bogomaz DI, Pavlova OA et al. (2012) Horizontal gene transfer from genus Agrobacterium to the plant Linaria in nature. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 25:1542–1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matveeva TV, Lutova LA (2014) Horizontal gene transfer from Agrobacterium to plants. Front Plant Sci 5:326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrikeski PT (2013) Yeast competence for exogenous DNA uptake: towards understanding its genetic component. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 103:1181–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi K, Yamamoto S, Ohmine Y et al. (2016) A fast and practical yeast transformation method mediated by Escherichia coli based on a trans-kingdom conjugal transfer system: just mix two cultures and wait one hour. PLoS ONE 11:e0148989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowack EC, Price DC, Bhattacharya D et al. (2016) Gene transfers from diverse bacteria compensate for reductive genome evolution in the chromatophore of Paulinella chromatophora. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:12214–12219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piers KL, Heath JD, Liang X et al. (1996) Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:1613–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quispe-Huamanquispe DG, Gheysen G, Kreuze JF (2017) Horizontal gene transfer contributes to plant evolution: the case of Agrobacterium T-DNAs. Front Plant Sci 8:2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley DR, Sieber KB, Robinson KM et al. (2013) Bacteria-human somatic cell lateral gene transfer is enriched in cancer samples. PLoS Comput Biol 9:e1003107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönknecht G, Chen WH, Ternes CM et al. (2013) Gene transfer from bacteria and archaea facilitated evolution of an extremophilic eukaryote. Science 339:1207–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönknecht G, Weber AP, Lercher MJ (2014) Horizontal gene acquisitions by eukaryotes as drivers of adaptive evolution. BioEssays 36:9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder G, Schuelein R, Quebatte M et al. (2011) Conjugative DNA transfer into human cells by the VirB/VirD4 type IV secretion system of the bacterial pathogen Bartonella henselae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:14643–14648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siamer S, Dehio C (2015) New insights into the role of Bartonella effector proteins in pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol 23:80–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber KB, Bromley RE, Dunning Hotopp JC (2017) Lateral gene transfer between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Exp Cell Res 358:421–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber KB, Gajer P, Dunning Hotopp JC (2016) Modeling the integration of bacterial rRNA fragments into the human cancer genome. BMC Bioinformatics 17:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltani J, van Heusden GP, Hooykaas PJJ (2008) Agrobacterium-mediated ransformation of non-plant organisms. In: Tzfira T, Citovsky V (eds) Agrobacterium: from biology to biotechnology. Springer, New York, pp 649–675 [Google Scholar]

- Stanhope MJ, Lupas A, Italia MJ et al. (2001) Phylogenetic analyses do not support horizontal gene transfers from bacteria to vertebrates. Nature 411:940–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegemann S, Hartmann S, Ruf S et al. (2003) High-frequency gene transfer from the chloroplast genome to the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:8828–8833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syvanen M (2012) Evolutionary implications of horizontal gene transfer. Annu Rev Genet 46:341–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kregten M, de Pater S, Romeijn R et al. (2016) T-DNA integration in plants results from polymerase-theta-mediated DNA repair. Nat Plants 2:16164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga MG, Shaffer CL, Sierra JC et al. (2016) Pathogenic Helicobacter pylori strains translocate DNA and activate TLR9 via the cancer-associated cag type IV secretion system. Oncogene 35:6262–6269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker BJ, Stan GV, Polizzi KM (2017) Intracellular delivery of biologic therapeutics by bacterial secretion systems. Expert Rev Mol Med 19:e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Lacroix B, Guo J et al. (2017) Transcriptional activation of virulence genes of Rhizobium etli. J Bacteriol 199:e00841–00816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters VL (2001) Conjugation between bacterial and mammalian cells. Nat Genet 29:375–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt T, Doohan F, Mullins E (2012) Production of Phytophthora infestans-resistant potato (Solanum tuberosum) utilising Ensifer adhaerens OV14. Transgenic Res 21:567–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt T, Doohan F, Winckelmann D et al. (2011) Gene transfer into Solanum tuberosum via Rhizobium spp. Transgenic Res 20:377–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White FF, Garfinkel DJ, Huffman GA et al. (1983) Sequences homologous to Agrobacterium rhizogenes T-DNA in the genomes of uninfected plants. Nature 301:348–350 [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Zhou Y, Huang J et al. (2015) Ancient horizontal transfer of transaldolase-like protein gene and its role in plant vascular development. New Phytol 206:807–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue J, Hu X, Huang J (2014) Origin of plant auxin biosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci 19:764–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue J, Hu X, Sun H et al. (2012) Widespread impact of horizontal gene transfer on plant colonization of land. Nat Commun 3:1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zardoya R, Ding X, Kitagawa Y et al. (2002) Origin of plant glycerol transporters by horizontal gene transfer and functional recruitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:14893–14896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga-Soto E, Mullins E, Dedicova B (2015) Ensifer-mediated transformation: an efficient non-Agrobacterium protocol for the genetic modification of rice. SpringerPlus 4:600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]