Abstract

Holins are integral membrane proteins that control the access of phage-encoded muralytic enzymes, or endolysins, to the cell wall by the sudden formation of an uncharacterized homo-oligomeric lesion, or hole, in the membrane, at a precisely defined time. The timing of λ-infected cell lysis depends solely on the 107 codon S gene, which encodes two proteins, S105 and S107, which are the holin and holin inhibitor, respectively. Here we report the results of biochemical and genetic studies on the interaction between the holin and the holin inhibitor. A unique cysteine at position 51, in the middle of the second transmembrane domain, is shown to cause the formation of disulfide-linked dimers during detergent membrane extraction. Forced oxidation of membranes containing S molecules also results in the formation of covalently linked dimers. This technique is used to demonstrate efficient dimeric interactions between S105 and S107. These results, coupled with the previous finding that the timing of lysis depends on the excess of the amount of S105 over S107, suggest a model in which the inhibitor functions by titrating out the effector in a stoichiometric fashion. This provides a basis for understanding two evolutionary advantages provided by the inhibitor system, in which the production of the inhibitor not only causes a delay in the timing of lysis, allowing the assembly of more virions, but also increases effective hole formation after triggering.

Bacteriophage λ has four lysis genes S, R, Rz, and Rz1 (8, 19, 25, 26, 40). Only S and R are absolutely required for host cell lysis under standard laboratory conditions (14, 15). Rz and Rz1 are required for lysis only when the outer membrane is stabilized by millimolar concentrations of divalent cations (40, 42). The overlapping lysis genes are clustered in a region referred to as the lysis cassette, and are located downstream of the single late gene promoter pR′ (Fig. 1A). The λ R gene encodes the endolysin, a soluble, cytoplasmic transglycosylase that accumulates throughout late gene expression (2, 8). The S gene, or holin, is a 107 codon open reading frame that encodes two nearly identical inner membrane proteins with opposing functions (3, 5, 10). Holins are responsible for controlling endolysin access to the host cell wall (38). At a precisely scheduled time programmed into the structure of the holin the host cytoplasmic membrane is permeabilized, allowing the transglycosylase access to the peptidoglycan, resulting in immediate cell lysis (37–39). Four lines of evidence speak to the nature of the hole. First, S acts independently of all other host and phage gene products to effect lysis; thus, the holes are thought to be composed solely of S protein (13, 30, 38). Second, cross-linking experiments demonstrate that the λ S protein can exist in an oligomeric state in the inner membrane (41). Third, the lesion has to be of sufficient size to allow the escape of fully folded 18-kDa endolysin in λ-infected cells, as well as endolysins up to 70 kDa from other phage-infected cells (12, 20, 23). Fourth, the hole is apparently nonspecific since permeabilization of the membrane by λ S allows the escape of heterologous endolysins (7, 21, 34). However, the true nature of the holin-mediated membrane lesion remains elusive.

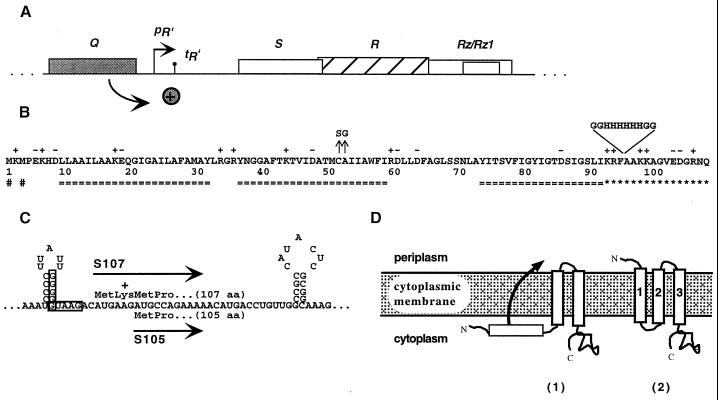

FIG. 1.

λ lysis cassette, translational control region, primary structure, and putative membrane topology for λ S. (A) All four lambda lysis genes—S, R, Rz, and Rz1—lie in an overlapping cluster in the lysis cassette downstream of the single late gene promoter pR′. Expression of the lysis genes is dependent on the antiterminator protein Q. (B) The primary structure of λ S is shown. Charged residues are indicated by + or −. Transmembrane domains as predicted by the TMHMM program are indicated (===) below the sequence (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-1.0/) (32). The highly charged dispensable C-terminal region is indicated by asterisks (4), and the two start codons of S are indicated (#) below the sequence. The missense changes of two early lysis alleles are marked by arrows above the sequence. The position and sequence of the oligo-histidine tag in Sτ94H is also indicated above the sequence. (C) The dual-start motif of λ S is shown. The boxed sequences indicate the Shine-Dalgarno sequences for the dual translational starts of S. The length of both protein products is given in amino acid (aa) residues. (D) Topological model for λ S with three alpha-helical transmembrane domains (2). A putative intermediate membrane topology for the lysis inhibitor, S107 is also depicted (1).

Despite a lack of structural data with respect to the hole, the understanding of holin regulation and function has continued to advance. It is known that two distinct proteins, S107 and S105, are expressed from the S gene and are composed of 107 and 105 amino acids, respectively (Fig. 1B and C). Although these two proteins differ by only two N-terminal residues (the N-terminal Met1-Lys2 extension of S107), they have opposing functions. The shorter product, S105, is the actual lysis effector, whereas the longer product, S107, functions as a specific inhibitor of S105 (3, 5, 24). Genetic studies revealed an mRNA secondary structure near the 5′ end of the S gene that controls translational initiations from Met1 and Met3 (Fig. 1C). This structure, termed sdi (for site-directed initiation), determines the ratio of S105 to S107, which is approximately 2:1 (10). S107 has a dual capacity; it acts as an inhibitor as long as the membrane is energized and actively contributes to hole formation upon depolarization of the membrane (3). Previous studies have shown that the additional positive charge at the N terminus of S107 is required for this inhibitory function (3, 33). Substitution of the lysine by the negatively charged residue glutamate not only abolishes inhibition but converts S107 into a lysis effector protein (3).

Recently, it has been shown that S has three membrane-spanning domains with the N terminus located in the periplasm and the C terminus located in the cytosol (9, 16, 17, 35) (Fig. 1D). Graschopf and Bläsi have proposed a molecular basis for the difference between S107 and S105 (16). These authors reported that the extension of the N terminus of S105 with a secretory signal sequence conferred leader peptidase dependency on the holin, strongly suggesting that the translocation of the N terminus to the periplasm is required for S function. Moreover, these results also implied that the extra N-terminal positive charge of S107 prevents or retards translocation of its N terminus to the periplasm, as demonstrated for other N-terminal translocation events in oligotopic membrane proteins with the same topology (Fig. 1D) (16, 35). Accordingly, the ability of S107 to inhibit S105 suggests that it interacts directly with the holin effector and that its N-in topology poisons hole formation, as previously proposed (6).

Here we report genetic, physiological and biochemical experiments to characterize the interaction between the λ S holin and the holin inhibitor in the membrane. The results are discussed in terms of a model for the control of lysis timing and the evolutionary advantages of the holin-endolysin pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials, strains, bacteriophages, plasmids, and growth media.

N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) and 1-10 phenanthroline were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo.). All other reagents were of the highest purity commercially available. The strains MC4100, XL1-Blue, the lysis-defective thermoinducible prophages λCmΔSR and λKnΔSR, and the lysis-proficient thermoinducible prophages λCmS105 (expressing S105) and λCmS105τ94 (expressing the histidine-tagged S105τ94) have been described previously (24, 28, 31). λCmS107 is essentially the same as λCmS105 with the exception that this phage has the M3L instead of the M1L mutation within the S gene and therefore expresses S107 protein only. Media, growth conditions, and thermal induction of the λ lysis genes from a prophage and/or plasmid have been described previously (10, 17, 30). The ability of S alleles to be triggered by cyanide was assessed by adding KCN to a final concentration of 10 mM to a portion of an induced culture. A 1 M KCN stock solution was freshly prepared just prior to use. All cells harboring a plasmid were grown in Luria broth with 100 μg of ampicillin/ml. Cells harboring a kanamycin- or chloramphenicol-resistant prophage were grown in LB with 40 μg of kanamycin or 10 μg of Cm chloramphicol per ml, respectively. Cells containing both a chloramphenicol-resistant prophage and an Ap plasmid were grown in LB-ampicillin medium without chloramphenicol.

Standard DNA manipulations, PCR, site-directed mutagenesis, and DNA sequencing.

Plasmids used in this study and plasmids newly constructed by site-directed mutagenesis are listed in Table 1, along with the single base changes. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.) as described previously (17). Base changes in all constructs were verified by automated fluorescence sequencing as described previously (29).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pKB1 | Derivative of pOR19; λ lysis gene region (Sam7) cloned as HindIII/ClaI fragment (λ nta 4141–46440) | 22 |

| pKB110 | Derivative of pOR19; λ lysis gene region cloned as HindIII/ClaI fragment (λ nt 4141–46440) | 9 |

| pS105 | S with M1L mutation (ATG→CTG); bears S105 only | 30 |

| pS107 | S with M3L mutation (ATG→CTG); bears S107 only | This study |

| pS105τ94 | Insertion (G2H6G2) after codon F94 in S105 | 30 |

| pS105A52G | S105 with A52G mutation (GCC→GGC) | 31 |

| pS105C51S | S105 with C51S mutation (TGC→AGC) | 17 |

| pSC51S | S with C51S mutation (TGC→AGC) | This study |

| pSA52G | S with A52G mutation (GCC→GGC) | This study |

| pS107C51S | S107 with C51S mutation (TGC→AGC) | This study |

| pS107A52G | S107 with A52G mutation (GCC→GGC) | This study |

nt, nucleotides.

Protein sample preparation, SDS-PAGE, Western blotting, and immunodetection.

Triton X-100-solubilized preparations of inner membrane proteins were obtained as described previously (10, 29). Briefly, 5-ml aliquots of induced cultures were disrupted by a single passage through a large SLM-Aminco French pressure cell (Spectronic Instruments, Rochester, N.Y.) at 16,000 lb/in2. The membrane fraction was collected from the disrupted sample by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 60 min at 18°C. The membrane pellet was solubilized in 50 μl of membrane extraction buffer (1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 0.5 M NaCl, 35 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) for 12 to 14 h at 37°C. Where indicated, the membrane extraction buffer was supplemented with 0.1 M NEM to avoid formation of disulfide bridges. After solubilization of the membrane pellet, detergent-insoluble material was removed by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 45 min at 18°C. Unless otherwise stated the detergent-soluble fraction was diluted 1:1 with 2× protein sample buffer devoid of reducing agent prior to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis. Protein samples were placed for 10 min at 37°C and then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature. Proteins were separated on a precast 16% Tris-Tricine mini gel (Xcell II Minicell; Novex, San Diego, Calif.) following the manufacturer's instruction. Western blotting and immunodetection with anti-S antibodies were performed as described previously (17).

Determination of protein synthesis, protein stability, and protein concentration.

To analyze levels of S synthesis as well as protein stability, MC4100 (λKnΔSR) bearing the plasmids pS107 or pS107C51S was induced at an A550 of 0.2 as described above. Aliquots (5 ml) were withdrawn 30, 60, and 90 min after thermal induction, and the Triton X-100 soluble fractions of inner membrane proteins were prepared as described. Total protein concentrations of these extracts were measured using the DC protein assay from Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) following the manufacturer's instructions. Protein samples were mixed 1:1 with 2× sample buffer containing 2.8 M β-mercaptoethanol, incubated 5 min at 100°C, and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature. Samples were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE as described above.

Oxidative disulfide bridge formation in membranes.

Cultures expressing one or two S alleles from a prophage, plasmid, or both were induced as described above, except that the cells were induced at an A550 of 0.3. Unless otherwise stated, 5-ml aliquots were disrupted in a French pressure cell after cell lysis was completed or 100 min after induction and oxidized with 20 mM CuSO4 and 60 mM 1-10 phenanthroline for 60 min at room temperature. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 0.1 M NEM, and incubation was continued at room temperature for an additional 60 min. A stock solution of CuSO4 was prepared in double-distilled water, and stock solutions of 1-10 phenanthroline and NEM were prepared in ethanol just prior to use. Membrane proteins were extracted in the presence of 0.1 M NEM, and protein samples were prepared for SDS-PAGE as described above. As a control to ensure that disulfide bond formation did not occur during sample preparation, two different plasmid-borne S alleles were induced in separate cultures and mixed shortly before disruption in the French pressure cell. These combined lysates were then subjected to centrifugation and detergent extraction as described above.

RESULTS

Cys51 supports oxidative dimerization of λ S but is nonessential for holin function.

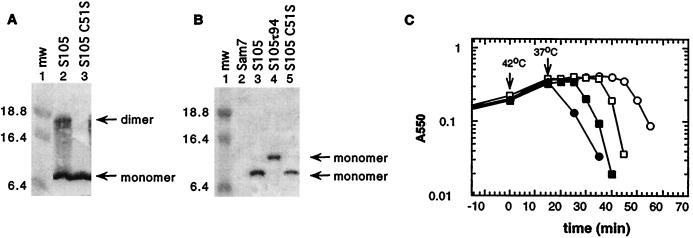

Using the cross-linker dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate), S oligomers up to hexamers have been detected in the cytoplasmic membrane by Western blot analysis (41). Even without the addition of a cross-linking agent, an SDS-resistant S dimer band was observed on Western blots (Fig. 2A, lane 2). Addition of reducing reagents, such as dithiothreitol or β-mercaptoethanol, reduced the intensity of this dimer band but did not completely abolish its appearance (data not shown). λ S has a single cysteine at position 51 which could be involved in dimer formation through the formation of an intermolecular disulfide bridge. To test this hypothesis the Cys codon at position 51 was mutated to Ser in the wild-type S gene as well as in the S105 and S107 genes (where S105 is SM1L producing only S105, and S107 is SM3L producing only S107, with Met3 replaced by a Leu residue [5]). Membrane extracts were prepared from cells in which S105C51S was expressed. No dimer band was detected with the cysteineless S variant (Fig. 2A, lane 3), indicating that the SDS-resistant dimer was a product of disulfide bond formation between Cys51 residues of two S105 molecules. The presence of NEM during membrane extraction with Triton X-100 abolished the formation of disulfide-bonded dimers, even in the absence of reductant in the protein sample buffer (Fig. 2B). Thus, the SDS-resistant disulfide-bonded dimers are not formed in the bacterial membrane but during membrane extraction with detergent. The formation of a disulfide bond is not required for holin function, since the cysteineless S alleles were fully functional and caused even earlier lysis than the parental S allele (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

S monomer and dimer formation in the cytoplasmic membrane. (A) Membrane protein samples were prepared from MC4100(λKnΔSR) + pS105 (lane 2) or MC4100(λKnΔSR) + pS105C51S (lane 3) and analyzed by Western blotting. (B) Membrane protein samples of MC4100(λCmΔSR) bearing the plasmids pKB1 (Sam7) (lane 2), pS105 (lane 3), pS105τ94 (lane 4), or pS105C51S (lane 5) were prepared in the presence of NEM in the membrane extraction buffer and analyzed by Western blotting. Molecular weights (mw) of the prestained molecular standards (in thousands) (lane 1) are indicated to the left. S monomer and dimer bands are indicated by arrows. (C) MC4100(λKnΔSR) cells carrying the plasmids pKB110 (S+) (○), pS105 (□), pSC51S (●), or pS105C51S (■) were induced and monitored for turbidity.

Specific disulfide bridge formation via single cysteine at position 51 in the membrane under oxidative conditions.

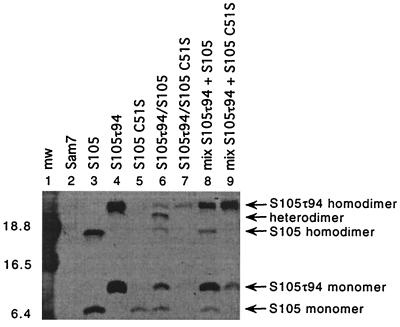

Next we tested whether disulfide bond formation between two S molecules could be forced in the bacterial membrane under oxidative conditions. This would allow the analysis of interactions between transmembrane segments of S. Membranes from cultures expressing one or two S alleles were subjected to oxidizing conditions by the addition of CuSO4 and 1-10 phenanthroline. Disulfide bond formation was stopped by the addition of NEM prior to detergent extraction of the membrane proteins. As shown in Fig. 3, these conditions supported efficient homodimer formation of S105 and S105τ94, the latter of which carries an oligo-histidine tag insert between residues 94 and 95 (Fig. 1B) and thus displays a reduced mobility during SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 4). In addition, heterodimers were formed between S105 and S105τ94 (Fig. 3, lane 6). Replacement of the cysteine in S105 with a serine prevented homo- and heterodimer formation (Fig. 3; lanes 5 and 7). Expression of the same two S alleles S105 and S105τ94 in different cells failed to produce heterodimers (Fig. 3, lane 8), showing that dimer formation between S molecules occurred indeed in the membrane environment and not during solubilization or a subsequent step in sample preparation.

FIG. 3.

S dimer formation in the bacterial membrane. Oxidation and sample preparation for Western blot analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Samples were prepared from the indicated strains: lane 1, molecular weight standards; lane 2, MC4100(λCmΔSR) + pKB1 (Sam7); lane 3, MC4100(λCmΔSR) + pS105; lane 4, MC4100(λCmΔSR) + pS105τ94; lane 5, MC4100(λCmΔSR) + pS105C51S; lane 6, MC4100(λCmS105τ94) + pS105; lane 7, MC4100(λCmS105τ94) + pS105C51S; lane 8, mixed cultures MC4100(λCmΔSR) + pS105τ94 and MC4100(λCmΔSR) + pS105; lane 9: mixed cultures MC4100(λCmΔSR) + pS105τ94 and MC4100(λCmΔSR) + pS105C51S. Molecular weights of the prestained molecular standards (mw) (in thousands) are indicated to the left of the panel. S monomer and dimer bands are indicated with arrows.

Direct interaction between the lysis protein S105 and the lysis inhibitor S107 in the bacterial membrane.

It has been proposed that the lysis inhibitor S107 inhibits lysis through intermolecular interaction with the lysis effector S105 (6). Under oxidative conditions S107 formed disulfide-bonded dimers in the membrane (Fig. 4, lane 3). The electrophoretic mobility of S107 homodimers was distinctively faster than the mobility of the S105τ94 homodimers (Fig. 4, lanes 3 to 5), which made it possible to discriminate between homodimer and heterodimer formation. Indeed, under oxidative conditions efficient heterodimer formation between holin and holin inhibitor was observed, if the membranes contained both the effector S105τ94 and the inhibitor S107 (Fig. 4, lane 6).

FIG. 4.

Interaction between the holin S105 and holin inhibitor S107 in the bacterial membrane. Protein samples were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Lane 1, molecular weight standards; lane 2, MC4100(λCmΔSR) + pKB1 (Sam7); lane 3, MC4100(λCmΔSR) + pS107; lane 4, MC4100(λCmΔSR) + pS105τ94; lane 5, mixed cultures MC4100(λCmΔSR) + pS105τ94 and MC4100(λCmΔSR) + pS107; lane 6, MC4100(λCmS107) + pS105τ94. Labeling of the panel is as described in the legend to Fig. 3.

The inhibitor function is abolished in the early lysis mutants SC51S and SA52G.

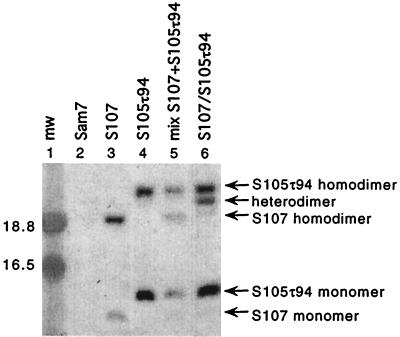

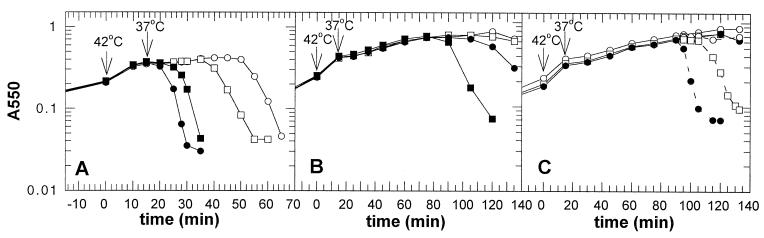

The cysteineless S allele SC51S exhibited an early lysis phenotype (Fig. 2C). The mutant SA52G with a similar phenotype has been isolated previously by genetic selection (Fig. 5A) (18). The lysis phenotype of both mutants was distinctive. Expression of wild-type S resulted in retarded lysis, compared to S105, because the former produces the inhibitor S107 in addition to the holin effector S105. In contrast, expression of SC51S or SA52G, which encode both the shorter and longer forms, resulted in earlier lysis than with the alleles S105C51S or S105A52G, which produce only the short form of the protein (Fig. 2C and 5A). This indicated not only that the S107C51S and S107A52G proteins had lost their inhibitory capacity but that they had been converted into effectors. A similar result has been previously reported for the S107K2E mutant protein (3).

FIG. 5.

Lysis phenotype of SA52G, S107A52G, and S107C51S. In all panels, lysogens carrying the specified plasmids were induced and monitored for turbidity. (A) Lysogen, MC4100(λCmΔSR); plasmids, pKB110 (S+) (○), pS105 (□), pSA52G (●), or pS105A52G (■). (B) Lysogen, MC4100(λCmΔSR); plasmids, pKB1 (Sam7) (○), pS107 (□), pS107C51S (●), or pS107A52G (■). (C) Lysogen, MC4100(λKnΔSR); plasmids, pKB1 (Sam7) (○), pS107 (□), or pS107C51S (●). In this experiment the cultures were divided into two flasks 90 min after induction and 10 mM KCN was added to one flask (dashed lines). The turbidity of the culture was monitored until lysis was completed or 130 min after induction.

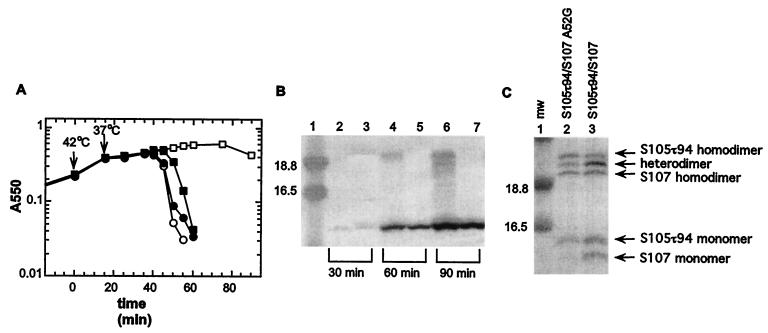

To examine the lysis phenotype of the mutant S107 proteins in more detail, we constructed the plasmids pS107, pS107C51S, and pS107A52G, which each produce only the S107 form. Expression of the mutant S107 alleles by transactivation in induced lysis-defective lysogens had a more deleterious effect on cell growth than expression of the parental S107 allele, resulting in lysis onset at about 90 to 100 min after induction with pS107A52G (Fig. 5B). Although S107C51S did not support lysis, it exhibited more rapid triggering after addition of an energy poison than the parental S107 allele (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, expression of these mutant S107 alleles in trans to S105 revealed that these S107 variants exhibit essentially no inhibitory effect (Fig. 6A). To ensure that this loss of inhibitor capacity was not due to altered protein synthesis or decreased stability, the accumulation of S107 and S107C51S proteins was examined by Western blot analysis and revealed no difference between the two proteins (Fig. 6B). Therefore, we conclude that the loss of inhibitory function of the S107C51S allele is not due to impaired expression or reduced protein stability. Another possibility is that the loss of the inhibitor function is due to the inability of the mutant S107 proteins to dimerize with S105. For S107C51S this cannot be tested with the oxidation method because of the lack of the Cys residue. However, with A52G, this method revealed that substantial heterodimer formation between S107A52G and S105 can be detected (Fig. 6C). Although this technique does not permit quantitative assessment of the capacity for heterodimerization, due to differential extractability from the oxidized membrane material, nevertheless we conclude that the severe reduction in the ability of S107A52G to function as a holin inhibitor does not reflect a major loss in its ability to interact with S105.

FIG. 6.

Expression of S107A52G and S107C51S in trans to S105. (A) The inhibitory effect of the mutant S107 protein was tested in trans to S105. MC4100(λCmS105) cells carrying the plasmids pKB1 (Sam7) (○), pS107 (□), pS107C51S (●), or pS107A52G (■) were induced and monitored for turbidity. (B) Expression and stability of S107 and S107C51S were analyzed by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. Samples from the induced cultures were taken 30, 60, or 90 min after induction. Lane 1, molecular weight standards; lanes 2, 4, and 6, S107; lanes 3, 5, and 7, S107C51S. Time points when samples were taken are indicated below the panel. Total protein (12.8, 21, or 28 μg) was loaded for the 30, 60, or 90 min time points, respectively. Labeling of the panel is as described in the legend to Fig. 3. (C) Aliquots (5 ml) of the induced cultures were taken 50 min after induction. Oxidation and sample preparation for Western blot analysis were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, molecular weight standards; lane 2, MC4100(λCmS105τ94) + pS107A52G; lane 3, MC4100(λCmS105τ94) + pS107. Labeling of the panel is as described in the legend to Fig. 3.

DISCUSSION

The role of the S protein in the λ lytic cycle is to terminate the vegetative phage cycle at a precisely scheduled time by allowing the fully folded endolysin R access to its substrate, the peptidoglycan. The structure of the membrane lesion which permits the transit of R is unknown. In the simplest model, the S protein, which has three transmembrane domains, would form an oligomeric hole at least 5 nm in diameter (to allow passage of the globular R protein [12]) (16, 17, 38). Although direct evidence for the hole has not yet been obtained, the available biochemical, genetic, and physiological data support the concept of a homo-oligomeric lesion in the membrane (39, 41).

The sole cysteine, Cys51, in the λ S sequence has been shown to be located in the core of the second membrane-spanning domain (17). In this work, it is shown that under oxidative conditions a disulfide bond between two S molecules can be formed in the membrane (Fig. 3). Under the oxidative conditions used in these experiments, approximately 50% of the total S105 protein can be trapped in this covalent dimer form (Fig. 3). Taken with the finding that the disulfide linkage itself is not required, as shown by the lytic competence of the C51S mutant, this suggests that much of the holin pool forms noncovalent dimers during the period leading to hole formation. Using these oxidative conditions, we were also able to obtain the first biochemical evidence for a direct interaction between the lysis effector and the lysis inhibitor (Fig. 4). Although the effector in this case is the histidine-tagged S105τ94 protein, there is ample evidence that the interaction between it and S107 is the same as that between S105 and S107. First, the S105τ94 allele is expressed at normal levels and has a normal lysis time under physiological conditions (31). Moreover, host lysis by either S105 or S105τ94 is retarded equivalently by the expression of S107 in trans (Fig. 6A and data not shown). It is worth noting that the proportion of heterodimers formed between S107 and S105τ94, relative to the S107 homodimers, is apparently higher than that observed with S105 and S105τ94, suggesting that the extra N-terminal Met1 Lys2 sequence confers on the inhibitor form of S a bias towards heterodimer formation.

It is unknown how the S107 inhibitor acts to block or retard the action of S105. Recently, Graschopf and Bläsi (16) reported that fusing a secretory signal sequence to the N terminus of S not only made lysis dependent on cleavage of the signal sequence but also largely eliminated the functional difference between the effector and inhibitor forms. This suggested a model in which, after integration of transmembrane domains 2 and 3 (Fig. 1D) into the bilayer, the N terminus of S107 with its extra cationic side chain is blocked from penetration by the energized membrane, as reported for leader petidase Lep and M13 coat protein gpVIII (11, 27). However, Barenboim et al. (1) have shown that the dual-start motif functions analogously in the type II holin gene S21, where the N terminus is almost certainly located in the cytosol. In light of these findings the longer gene products resulting from dual-start motifs in class I and II holins may attain inhibitor capacity by different molecular mechanisms. Regardless of the mechanism, there must be a significant selective advantage in having an intrinsic inhibitor system, since dual-start motifs have been identified in a number of other class I and class II holin genes from phages of both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria (37, 39).

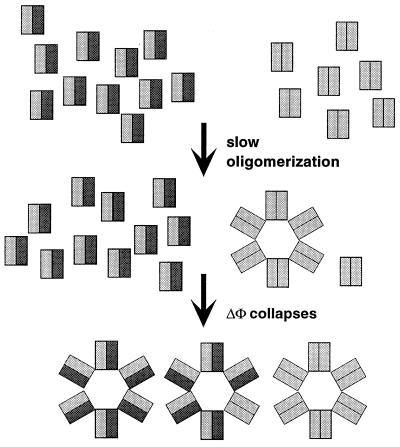

The demonstration here of efficient dimerization of holin proteins within the membrane environment and a direct dimer interaction between S105 and S107 suggests an operational basis for this selective advantage. In the scenario depicted in Fig. 7, it is postulated that the holin dimer is the fundamental unit of assembly of the holin lesion and that S107 exerts its inhibitory effect by dimerizing with S105, creating heterodimers which are either nonfunctional or of reduced functional capacity. Functional, in this case, is defined as counting in the pathway towards assembly of an oligomeric lesion, which is drawn in Fig. 7 as a hole of six dimers for illustrative purposes. This model is supported by the work of Chang et al. (10), which demonstrated a correlation between lysis timing and the excess of S105 over S107. Based on the 2:1 ratio of S105 to S107 prior to the triggering of lysis, about half of the S105 molecules would be unavailable by virtue of dimerization with S107. If about 1,000 molecules of S are present per cell at the time of lysis, then there would be about 500 dimers, of which two-thirds would be inactive heterodimers if S107 preferentially complexes with S105. The effect is that the timing of lysis, reflecting the rate of accumulation of the active S105 homodimers, is delayed because half of the effector is hidden from participating in the formation of the first lesion. However, once that first lesion is formed, the membrane potential would collapse, eliminating the inhibitory capacity of S107 (3, 5). Thus, suddenly all of the previously inactive S105-S107 heterodimers would be triggered into forming the permeabilizing lesions.

FIG. 7.

Model for lysis inhibition by S107. S105 and S107 molecules are represented by gray and black rectangles, respectively. The model assumes that holin dimers are the functional unit for the assembly of the membrane lesion; that S107 preferentially forms heterodimers with S105, which is in a twofold excess over S107; and that S105-S107 heterodimers are nonfunctional for hole formation. Once the first membrane lesion is formed the membrane potential (ΔΦ) collapses, which allows the inactive S105-S107 heterodimers to participate in hole formation.

Two main advantages are conferred by such a system. First, very precise adjustment of the timing of hole formation, and thus the length of the vegetative phase of phage development, can be achieved by altering the relative proportion of inhibitor and effector. Wang et al. (36) have shown that there is an optimal time for lysis for any particular combination of bacterial and phage growth conditions, and clearly the dual-start motif would constitute an ideal system for evolutionary fine-tuning to the best lysis time. Moreover, it is possible that there are physiological conditions that would alter the S105/S107 ratio, either through effects on the translational control of S or perhaps through selective proteolysis of the inhibitor or effector forms. Second, the system also confers a saltatory nature to the lysis phenomenon, because at the instant of triggering (either when the first hole forms naturally or when an exogenous factor depolarizes the membrane), the amount of functional dimers is trebled, presumably allowing many more permeabilizing lesions to form. As has been suggested elsewhere, it is crucial that the lytic process, once begun, be as rapid and complete as possible, for the obvious reason that no further particle assembly occurs once the cell is physiologically dead because of the permeabilized membrane (6). Thus, the dual-start motif contributes to keeping the infected cell productive for as long as is optimal but then minimizing the dwell time in the lysing corpse of the host.

The data clearly show that the two mutations A52G and C51S both largely ablate the inhibitory capacity of S107 (Fig. 6A). For the C51S mutation, it is also clear that this loss of inhibitory function is not due to decreased accumulation in the membrane (Fig. 6B). Moreover, this loss of inhibitory function is not due to a general reduction in the ability to participate in oligomeric interactions, because, at least with A52G, the S107 product not only loses inhibitor function but also gains effector function (Fig. 5B). Both changes also significantly accelerate the triggering of lysis in the context of the S105 effector protein (Fig. 2C and 5A). The simplest interpretation is that the S105-S107 heterodimers are blocked from participating in the formation of the oligomeric lesion because of a required conformational change that is favored by the A52G and C51S changes and blocked by the extra N-terminal positive charge on S107. Experiments to determine whether this involves the putative externalization of the N-proximal transmembrane domain are in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support for this work was provided by PHS grant GM27099 and funds from the Robert A. Welch Foundation and Texas Agricultural Experiment Station.

We thank all the members of the Young laboratory for their support and Sharyll Pressley for her always-reliable secretarial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barenboim M, Chang C-Y, dib Hajj F, Young R. Characterization of the dual start motif of a class II holin gene. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:715–727. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bienkowska-Szewczyk K, Lipinska B, Taylor A. The R gene product of bacteriophage λ is the murein transglycosylase. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;184:111–114. doi: 10.1007/BF00271205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bläsi U, Chang C-Y, Zagotta M T, Nam K, Young R. The lethal λ S gene encodes its own inhibitor. EMBO J. 1990;9:981–989. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bläsi U, Fraisl P, Chang C-Y, Zhang N, Young R. The C-terminal sequence of the lambda holin constitutes a cytoplasmic regulatory domain. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2922–2929. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.9.2922-2929.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bläsi U, Nam K, Hartz D, Gold L, Young R. Dual translational initiation sites control function of the lambda S gene. EMBO J. 1989;8:3501–3510. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bläsi U, Young R. Two beginnings for a single purpose: the dual-start holins in the regulation of phage lysis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:675–682. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.331395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonovich M T, Young R. Dual start motif in two lambdoid S genes unrelated to λ S. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2897–2905. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2897-2905.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell A, Campillo-Campbell A D. Mutant of bacteriophage lambda producing a thermolabile endolysin. J Bacteriol. 1963;85:1202–1207. doi: 10.1128/jb.85.6.1202-1207.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang C-Y. Synthesis, function and regulation of the lambda holin. Ph.D. thesis. College Station: Texas A&M University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang C-Y, Nam K, Young R. S gene expression and the timing of lysis by bacteriophage λ. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3283–3294. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3283-3294.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalbey R E, Kuhn A, von Heijne G. Directionality in protein translocation across membranes: the N-tail phenomenon. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:380–383. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)89079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evrard C, Fastrez J, Declercq J P. Crystal structure of the lysozyme from bacteriophage lambda and its relationship with V and C-type lysozymes. J Mol Biol. 1998;276:151–164. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrett J, Bruno C, Young R. Lysis protein S of phage lambda functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:7275–7277. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.7275-7277.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrett J, Fusselman R, Hise J, Chiou L, Smith-Grillo D, Schulz R, Young R. Cell lysis by induction of cloned lambda lysis genes. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;182:326–331. doi: 10.1007/BF00269678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrett J, Young R. Lethal action of bacteriophage lambda S gene. J Virol. 1982;44:886–892. doi: 10.1128/jvi.44.3.886-892.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graschopf A, Bläsi U. Molecular function of the dual-start motif in the λ S holin. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:569–582. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gründling A, Bläsi U, Young R. Biochemical and genetic evidence for three transmembrane domains in the class I holin, λ S. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:769–776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson-Boaz R, Chang C-Y, Young R. A dominant mutation in the bacteriophage lambda S gene causes premature lysis and an absolute defective plating phenotype. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:495–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kedzierska S, Wawrzynow A, Taylor A. The Rz1 gene product of bacteriophage lambda is a lipoprotein localized in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1996;168:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00712-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loessner M J, Gaeng S, Scherer S. Evidence for a holin-like protein gene fully embedded out of frame in the endolysin gene of Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophage 187. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4452–4460. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4452-4460.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu M-J, Henning U. Lysis protein T of bacteriophage T4. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;235:253–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00279368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nam K. Translational regulation of the S gene of bacteriophage lambda. Ph.D. thesis. College Station: Texas A&M University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navarre W W, Ton-That H, Faull K F, Schneewind O. Multiple enzymatic activities of the murein hydrolase from staphylococcal phage φ11. Identification of a D-alanyl-glycine endopeptidase activity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15847–15856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raab R, Neal G, Sohaskey C, Smith J, Young R. Dominance in lambda S mutations and evidence for translational control. J Mol Biol. 1988;199:95–105. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reader R W, Siminovitch L. Lysis defective mutants of bacteriophage lambda: genetics and physiology of S cistron mutants. Virology. 1971;43:607–622. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(71)90286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reader R W, Siminovitch L. Lysis defective mutants of bacteriophage lambda: on the role of the S function in lysis. Virology. 1971;43:623–637. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(71)90287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuenemann T A, Delgado-Nixon V M, Dalbey R E. Direct evidence that the proton motive force inhibits membrane translocation of positively charged residues within membrane proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6855–6864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.6855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith D L. Purification and biochemical characterization of the bacteriophage λ holin. Ph.D. thesis. College Station: Texas A&M University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith D L, Chang C-Y, Young R. The λ holin accumulates beyond the lethal triggering concentration under hyper-expression conditions. Gene Expr. 1998;7:39–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith D L, Struck D K, Scholtz J M, Young R. Purification and biochemical characterization of the lambda holin. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2531–2540. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2531-2540.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith D L, Young R. Oligohistidine tag mutagenesis of the lambda holin gene. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4199–4211. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.16.4199-4211.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sonnhammer E L, von Heijne G, Krogh A. Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology. Menlo Park, Calif: AAAI Press; 1998. A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences; pp. 175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steiner M, Bläsi U. Charged amino-terminal amino acids affect the lethal capacity of lambda lysis proteins S107 and S105. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:525–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steiner M, Lubitz W, Bläsi U. The missing link in phage lysis of gram-positive bacteria: gene 14 of Bacillus subtilis phage φ29 encodes the functional homolog of lambda S protein. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1038–1042. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1038-1042.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Heijne G, Gavel Y. Topogenic signals in integral membrane proteins. Eur J Biochem. 1988;174:671–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang I-N, Dykhuizen D E, Slobodkin L B. The evolution of phage lysis timing. Evol Ecol. 1996;10:545–558. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang I-N, Smith D L, Young R. Holins: the protein clocks of bacteriophage infections. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:799–825. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young R. Bacteriophage lysis: mechanism and regulation. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:430–481. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.3.430-481.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young R, Wang I-N, Roof W D. Phages will out: strategies of host cell lysis. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:120–128. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young R, Way S, Yin J, Syvanen M. Transposition mutagenesis of bacteriophage lambda: a new gene affecting cell lysis. J Mol Biol. 1979;132:307–322. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zagotta M T, Wilson D B. Oligomerization of the bacteriophage lambda S protein in the inner membrane of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:912–921. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.912-921.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang N, Young R. Complementation and characterization of the nested Rz and Rz1 reading frames in the genome of bacteriophage lambda. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;262:659–667. doi: 10.1007/s004380051128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]