Abstract

Since 2014, the National Lung Cancer Audit (NLCA) has been evaluating the performance of the UK NHS lung cancer services against established standards of care. Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the NLCA's annual reports revealed a steady stream of improvements in early diagnosis, access to surgery, treatment with anti-cancer therapies, input from specialist nursing and survival for patients with lung cancer in the NHS. In January 2022, the NLCA reported on the negative impact COVID-19 has had on all aspects of the lung cancer diagnosis and treatment pathway within the NHS. This article details the fundamental changes made to the NLCA data collection and analysis process during the COVID-19 pandemic and details the negative impact COVID-19 had on NHS lung cancer patient outcomes during 2020.

Key words: Audit, cancer, COVID-19, improvement, lung, national, NHS, NLCA, pandemic, surgery, survival

Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most common type of cancer in the UK, after breast cancer, with over 44 500 new cases diagnosed each year, and is the most common cause of cancer-related death [1]. In 2018, the UK ranked sixth among the 31 European countries studied for the incidence of lung cancer, with 79 in every 100 000 people being diagnosed with the condition [2]. The UK's incidence rate for this cancer type was higher than the European average of 71 cases per 100 000 people and the UK ranked the 12th highest among the 31 European countries studied for the age-standardised mortality of lung cancer, with 57 in every 100 000 people dying from the condition in 2018 [2]. The UK's mortality rate for this cancer type was lower than the European average of 58 per 100 000 people [2].

The National Lung Cancer Audit (NLCA) was established in 2004 in response to the findings that outcomes for lung cancer patients in the UK lagged those in other Westernised countries and varied considerably between organisations in the UK. The NLCA is a national clinical audit commissioned by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership on behalf of NHS England in response to the need for better information about the quality of services and care provided to individuals with lung cancer in England and Wales [3]. The NLCA is part of the National Clinical Audit and Patient Outcomes Programme, which also includes additional cancer audits focusing on breast, bowel, oesophagogastric and prostate cancer. The NLCA works with the National Cancer Registry in England and the Wales Cancer Network to acquire datasets on lung cancer patients, which allows it to report on how well people with lung cancer are being diagnosed and treated in hospitals across England and Wales.

The NLCA evaluates the performance of NHS lung cancer services against established standards of care and encourages NHS hospitals with unwarranted levels of variation in areas of clinical practice or patient outcomes to examine their lung cancer service and formulate action plans to improve their clinical performance. The NLCA indicators and associated targets, which are detailed in Table 1 , have been developed over the last 15 years and form a consensus across the NLCA team and its clinical advisory group and board members that all NHS hospitals and health boards delivering lung cancer services should be achieving.

Table 1.

Performance status (PS), Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), Systemic anticancer therapy (SACT).

| Key indicators | NLCA benchmark figures | 2019 RCRD | 2020 RCRD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | N/A | 33 ,091 | 31 ,371 |

| Proportion of patients with stage IV disease | N/A | 43% | 44% |

| Proportion of patients with PS 0–1 | N/A | 52% | 47% |

| Proportion of patients with pathological confirmation of | |||

| lung cancer for stage I/II and PS 0–1 | ≥90% | 84% | 77% |

| Proportion of patients with NSCLC undergoing surgery | >17% | 20% | 15% |

| Proportion of patients with SCLC receiving chemotherapy | >70% | 69% | 66% |

| Curative treatment rate in patients with stage I/II and PS 0–1 | >80% | 81% | 73% |

| Proportion of patients with NSCLC stage IIIB–IV and PS 0–1 who | |||

| received systemic anti-cancer therapy | >65% | 54% | 55% |

| Proportion of patients seen by lung CNS | >90% | 80% | 75% |

| Diagnosis via emergency presentation | N/A | 31% | 35% |

| Median time from diagnosis to treatment | N/A | 28 days | 27 days |

| Median survival | N/A | 316 days | 306 days |

CNS, cancer nurse specialist; NLCA, National Lung Cancer Audit; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PS, performance status; RCRD, Rapid Cancer Registration Dataset; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

Since its inception, the NLCA has been at the vanguard of cancer audit and has driven quality improvement for lung cancer patients across England and Wales. In particular, the NLCA has helped to drive up lung cancer surgical resection rates and, in turn, the number of thoracic surgeons within the NHS [[4], [5], [6]]. Through the course of its annual publications, it has documented a sustained improvement in survival rates after surgery and a national transition to minimal access surgery as the predominant approach used [4]. The NLCA has impacted at local, regional and national levels, helping to inform national and international guidelines. As a result, standards and outcomes for patients with lung cancer have improved year on year [4,5,[7], [8], [9]]. This has been achieved by disseminating to hospitals and their clinical teams the findings of the audit that highlight the areas of good clinical practice and areas that should be improved. In recent years, the NLCA has used a robust outlier process, which has helped to further drive quality improvement [10]. Hospital trusts that are identified to be outliers are contacted and invited to review their data accuracy and provide an action plan to improve the metric for which they have been identified as outliers. Although this could be challenging, it has been a positive experience for several trusts and provided leverage to gain additional resources within organisations to help improve lung cancer care. The results of the NLCA are also made easily available to the public, patients and their carers for scrutiny and reflection and the NLCA has previously published a report specifically tailored to patients and carers [9,11]. The NLCA has also published spotlight audits on curative-intent treatment rates for stage I–IIIa non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), molecular testing rates in advanced lung cancer, management of mesothelioma and lung cancer service organisational reports for NHS lung cancer services in England and Wales [8,[12], [13], [14]].

Methods

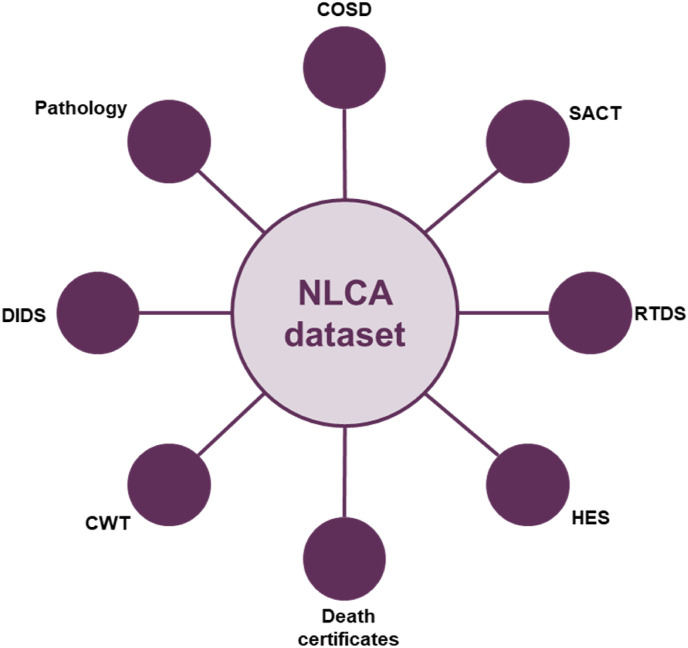

The audit began collecting data nationally in 2005, and since then has become an exemplar among national cancer audits. The original lung cancer audit dataset (LUCADA), as part of a standalone system of data collection, was reliant upon clinicians and multidisciplinary team co-ordinators submitting data for analysis. However, since 2014, the NLCA has only used pre-existing information from routine hospital administrative datasets on the diagnosis, management and treatment of every patient newly diagnosed with lung cancer available from the National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service (NCRAS) in England and the Wales Cancer Network. The advantage of this approach is that it minimises the burden of data collection on multidisciplinary teams. This includes the Cancer Outcomes and Services Dataset (COSD), which specifies the data items that need to be submitted to NCRAS on a monthly basis via multidisciplinary team electronic data collection systems linked to other national datasets to provide extra information including ‘gold standard’ cancer registry data (whereby NCRAS processes and collates patient data from a range of national data feeds across all NHS providers), Hospital Episode Statistics data, the Office for National Statistics dataset, the national Radiotherapy Dataset and the Systemic Anti-Cancer Dataset.

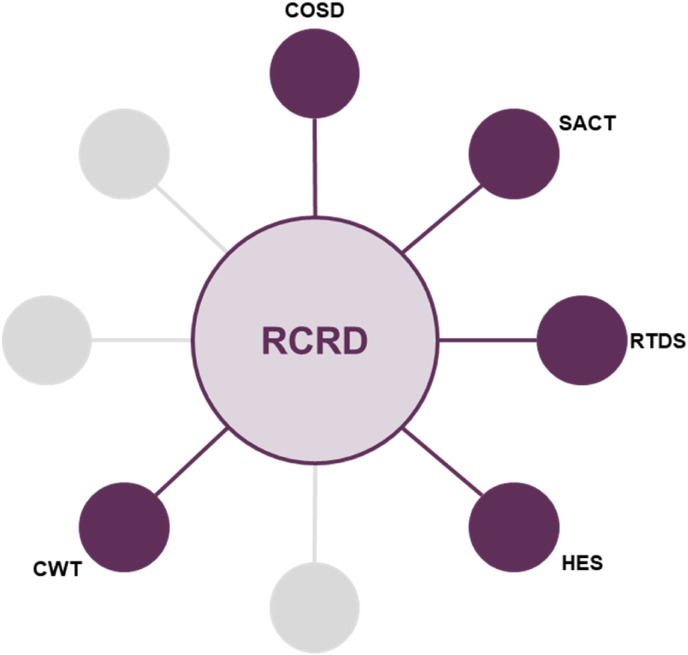

More recently, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in significant delays to the availability of ‘gold standard’ cancer registry data. However, for the most recent NLCA Annual Report, NCRAS provided data from the Rapid Cancer Registration Dataset (RCRD), which is sourced mainly from COSD but contains proxy tumour registrations, as the ‘gold standard’ cancer registry data were unavailable. The use of the RCRD represents a new phase in the evolution of the NLCA. This dataset is provided more quickly than has been possible in the past, although the speed of production and the pandemic has meant that several of the standard data items are unavailable or too incomplete for use. Importantly, registrations of lung cancer only occur from the COSD dataset and patients with entries only in the Systemic Anti-Cancer Dataset, Hospital Episode Statistics, the national Radiotherapy Dataset or death certificate-only routes are not included. However, this rapid data source has enabled the NCLA team to provide a more rapid view of lung cancer care in 2019 and 2020 than has been previously possible. Fig 1, Fig 2 show the different data sources used in the pre-COVID-19 pandemic NLCA dataset and the new RCRD dataset.

Fig 1.

Gold standard National Lung Cancer Audit (NLCA) dataset. COSD, Cancer Outcomes and Services Dataset; CWT, cancer waiting times; DIDS, Diagnostic Imaging Dataset; HES, Hospital Episode Statistics; RTDS, Radiotherapy Dataset; SACT, System Anti-cancer Therapy Dataset.

Fig 2.

Rapid Cancer Registration Dataset (RCRD). COSD, Cancer Outcomes and Services Dataset; CWT, cancer waiting times; HES, Hospital Episode Statistics; RTDS, Radiotherapy Dataset; SACT, System Anti-cancer Therapy Dataset.

In August 2020, the NLCA published its 15th annual report covering key performance indicator results for lung cancer services and patient outcomes for patients diagnosed during 2018 prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The report revealed a steady stream of improvements in early diagnosis, access to surgery, treatment with anti-cancer therapies, input from specialist nursing and survival for patients with stage III NSCLC [7]. The 15th annual report though continued to highlight inequalities across NHS hospitals and made recommendations around key areas that could be improved further. Unfortunately, before these improvements could be implemented, the COVID-19 pandemic struck, which has caused significant disruption to healthcare services and delivery globally. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, lung cancer services in England and Wales have been affected, as shown in the results of the latest NLCA report published in January 2022 [5].

For the 2022 annual report, which covers both 2019 and 2020, only the RCRD was available for England (Figure 2). Therefore, it was decided that the report would initially compare this RCRD of 2019 patients with the usual quality-assured NLCA dataset from 2018. Assuming that the incidence of lung cancer was unchanged between 2018 and 2019, the analysis revealed that the 2019 RCRD seems to have not included about 4300 patients previously identified by Public Health England's full registration process. Another significant issue the NLCA team faced was that ‘trust first seen’ was not available for the RCRD and it was therefore not possible to run the trust allocation algorithm used in previous years. Therefore, a decision was taken by the NLCA team to only provide data at alliance level and consequently it was not possible to conduct and publish an outlier process within the 2022 NLCA report. An analysis of data completeness revealed significant variation across alliances and could reflect a further impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the ability to collect and enter patient data in an efficient and timely manner.

A huge advantage of the new RCRD process is that the data are available for extraction 4 months after diagnosis. For the 2022 NLCA report, data for the 2020 cohort were provided in June 2021, prior to analysis in July 2021. This is a significant improvement on past NLCA reports, where there was typically an 18-month period between diagnosis and data availability for analysis. When combined with the report review process within funder organisations, this has meant that prior reports were not available to the clinical community for at least 2 years after diagnosis, limiting their impact on quality improvement. If the RCRD continues to be used for future audit cycles, it is hoped that upcoming annual reports will be available a maximum of 1 year after the last diagnosis and that regularly updated dashboards are available for local quality improvement initiatives.

Results

Despite the caveats of the RCRD, the results from 2019 and 2020 make for concerning reading. Many of the predictions of the impact of COVID-19 have come to pass and perhaps the outcomes are worse than expected [15,16]. In England in 2019, the incidence of lung cancer recorded in the RCRD was 83% of that recorded in the 2018 full registration dataset. The RCRD did not capture about 4300 patients per year with a poorer prognosis and, as a result, patients in 2019 would seem to have a better prognosis than those included in previous years. Therefore, the 1-year survival of 46% for patients diagnosed in 2019 (compared with 39% in 2018) may not be an accurate representation of all patients and shows that the RCRD is biased to those patients with better survival.

The 2022 NLCA report showed a significant drop in curative treatment rate for stage I/II, performance status 0–1 NSCLC patients, from 81% in 2019 to 73% in 2020, with surgical resection rates in 2020 like those 10 years ago. Both the 2019 and 2020 data demonstrate that about 40–50% of stage IIIA patients with performance status 0–2 and potentially ‘curable’ stage III NSCLC are still either receiving no active treatment or palliative-intent chemotherapy with or without palliative radiotherapy. These treatment rates probably significantly contributed to the low median survival for stage III NSCLC patients in England at 12 months in 2019.

In 2017, the NLCA set an audit standard of systemic anti-cancer therapy for 65% of patients with advanced NSCLC (stages IIIB, IIIC and IV) and a good performance status (0–1). Overall, 54% of patients in 2019 and 55% in 2020 with good performance status and advanced NSCLC received systemic anti-cancer therapy. This seems to represent a substantial fall from the 2018 result of 65% and reveals that the audit standard of 65% was not met during both these analysis periods.

Table 1 highlights the clinical impact that COVID-19 has had on key lung cancer metrics. In addition to the reduction in the number of lung cancer diagnoses, there is a stage shift to patients with more advanced disease and more patients diagnosed via the emergency route, both of which are associated with poorer outcomes. Performance status is also known to be a powerful predictor of prognosis and fewer patients had a performance status of 0–1 in 2020 (47% in 2020 versus 52% in 2019). As expected, there was a significant drop in pathological diagnosis rates in 2020 and the proportion of patients assessed by a nurse specialist, reflecting clinician redeployment and less diagnostic capacity in 2020. These factors, plus the loss of critical care and surgical inpatient bed capacity through acute COVID-19 admissions, have led to a 10% drop off in surgical resection rates in eligible patients, which prior to 2020 had been increasing and takes us back to a surgical resection rate from 10 years ago. The curative-intent treatment rate in patients with early-stage disease and good performance was significantly reduced from 81% in 2019 to 73% in 2020. This is explained by the fall in surgical resection rates, which has only partly been compensated for by an increase in radical radiotherapy, including stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy. An analysis of the impact COVID-19 had on diagnostic and treatment pathways for patients undergoing lung radiotherapy has been conducted through the COVID-RT Lung cohort study [17]. This study analysed changes in lung cancer management and outcomes, with a specific focus on patients undergoing radical radiotherapy treatment. During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, consensus guidelines based on current literature and practice were published in the UK offering guidance on how to safely reduce the number of fractions (and therefore hospital visits) when delivering curative-intent radiotherapy in patients with lung cancer [18]. The COVID-RT Lung study found that 12% of patients referred for radical radiotherapy had their diagnostic investigations altered and a third of patients had a change to standards of care treatment [17]. In respect to systemic therapies, the proportion of eligible patients receiving systemic anti-cancer therapy was also lower in 2020.

The number of patients available for survival analysis in the 2020 dataset was 23 719 as the data cut-off was in October. The median survival of the analysed patients was 306 days (versus 316 for the 2019 cohort) and the 1-year survival was 44.3% (versus 46% for the 2019 cohort).

When interpreting these data, it must be borne in mind that the source of the data is the RCRD, and that the analysis is based upon 23 719 patients out of 31 371 in the dataset for whom 1 year follow-up was available. This dataset has the advantage of being available quickly after a patient is registered with a lung cancer diagnosis but has the disadvantage that many cases are missing. Many of the missing patients are those with advanced stage disease and worse prognosis. Therefore, although the 2019 and 2020 datasets appear to have similar survival, the 2020 dataset does not include missing patients with a poorer prognosis. If we assume that 4300 patients missing from the RCRD are distributed evenly throughout the year and that they also did not survive for 1 year, then the 1-year survival of patients in 2020 can be estimated to be 39%. A similar analysis for the 2019 data gives a 1-year survival of 40.7%. This suggests a drop in 1-year survival for the 2020 cohort compared with 2019, reversing the trend of improved survival seen in previous years.

During 2020, some lung cancer patients may have died with or because of COVID-19. This may explain the reduced incidence in 2020. In addition, routes to diagnosing early-stage lung cancer, e.g. on computed tomography scans carried out for other reasons or early detection initiatives, were interrupted in 2020. The NLCA report has also shown that compared with 2019, lung cancer patients diagnosed in England in 2020 had worse performance status, were more likely to be diagnosed via emergency presentation and less likely to have a pathological diagnosis. Curative treatment rates fell from 81% in 2019 to 73% in 2020, with a drop in surgical resection rate from 20% to 15%. These factors may contribute to worse survival in 2020.

Discussion

We can see from these results in key performance indicators that previous progress in lung cancer care has been reversed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The NLCA team support an urgent action plan for lung cancer to harness support and resources to rectify these adverse effects on lung cancer patients. The recovery will include continued expansion of the lung health check programme and implementing nationwide lung cancer screening, supporting lung cancer awareness and early diagnosis, rapid diagnosis, and treatment, guaranteeing adequate workforce, prioritising lung cancer research, allocation of sufficient in-patient capacity to allow elective surgical recovery, and ensuring that rapid high-quality data are available for organisations to implement improvement initiatives and identify pathway problems. It is also worth remembering that healthcare accounts for only a proportion of the variation in overall survival and that addressing social determinants of health will also have a significant impact.

Despite the pandemic, important areas for quality improvement can be identified. One key area is data completeness. The RCRD offers a more rapid method for data reporting, but if it is to be used routinely then case ascertainment and data completeness should be improved. Data completeness in 2020 for performance status and stage at alliance level ranged from 58% to 91%. Another notable finding within the 2022 NLCA report was that five of 21 cancer alliances were able to maintain treatment with curative-intent rates above 80% during the COVID-19 pandemic. The NLCA contacted clinical leads within organisations with high levels of data completeness and high curative treatment rates to gain insight on how this was achieved. The NLCA will provide these insights to alliances who have struggled to achieve this.

Finally, there must be an urgent refocus on early diagnosis. To achieve this, further implementation of lung cancer screening is required, and complementary work must be carried out at alliance and commissioner, as well as trust, level to promote early presentation of lung cancer patients. The NLCA can be central to supporting lung cancer services by its benchmarking of lung cancer services to national standards and by stimulating local quality improvement. The NLCA team has also set out improvement goals that it plans to implement during the next 5-year contract period:

-

•

Increasing the proportion of patients who receive treatment with curative intent. This will reflect two NICE 2019 Quality Standards: increasing the proportion of patients encouraged to seek medical advice if experiencing symptoms (statement 1) and ensuring that patients suitable for curative treatment have their stage and lung function established (statement 4 + 5) [19,20].

-

•

Increasing the proportion of patients who are assessed by a lung cancer nurse specialist – NICE 2019 Quality Standard (statement 3) [19,20].

-

•

Reducing the number of patients diagnosed after an emergency presentation. These patients usually have advanced stage and poor prognosis. This goal will form part of the NLCA reporting of routes to diagnosis and will be reported to primary care and cancer alliances to complement the work of the NHS England's Lung Health Checks initiative, part of the NHS Long Term Plan to improve early diagnosis and survival for those diagnosed with cancer [21].

-

•

Improving compliance with the National Optimal Lung Cancer Pathway, which sets tight timeframes for each stage of the care pathway, ideally enabling treatment for patients to start within 49 days of lung cancer being suspected [22].

-

•

Reducing variation in quality and improving timeliness for patients undergoing predictive molecular marker analysis – NICE 2019 Quality Standard (statement 6) [19,20].

These goals have been developed in consultation with the patient and professional representatives within the clinical reference group, which includes representation from Lung Cancer Nursing UK and the Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation. The NLCA believes that involvement of the members of the standalone NLCA Patient and Carer Panel, which it plans to establish, will be crucial for having the experiences and views of patients and their carers feed into the ongoing work of the NLCA team. The NLCA team also plans to create a quality improvement strategy that focuses on a strong communication policy, which will consist of three inter-related elements.

First, we will support clinical staff in the implementation of best practice by publishing key indicators for local benchmarking. The NLCA will review the existing key indicators with a view to refining and evolving them to enable us to monitor progress against existing and planned healthcare improvement goals. The NLCA team expect this process to build on the existing NLCA performance indicators seen in Table 1, so that the audit provides continuity for NHS lung cancer services. These indicators will be published quarterly on the NLCA dashboard and be presented in appropriate formats to promote quality improvement initiatives (e.g. run charts). Second, the NLCA will continue the programme of quality improvement workshops. These introduce delegates to quality improvement techniques and how they can be applied (e.g. the implementation of faster lung cancer pathways). It will also provide a venue for the sharing of good practice. Third, the NLCA will refine the existing quality improvement toolkit, which currently contains several aids to help local teams address areas of weakness identified by the indicator dashboard, and future state-of-the-nation NLCA reports.

Through the ongoing work of the NLCA and its annual publications, it is hoped that future reports will show the benefits of this on lung cancer care and patient outcomes within England and the devolved nations of the UK [23].

Funding

The National Lung Cancer Audit is currently funded by a grant from Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership to the Royal College of Surgeons. N. Navani is supported by a Medical Research Council Clinical Academic Research Partnership (MR/T02481X/1). This work was partly undertaken at the University College London Hospitals/University College London, which received a proportion of funding from the Department of Health's National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre's funding scheme.

Author Contributions

JC, JN, CF, DW, DC and NN are guarantors of integrity of the entire study. JC, JN, CF, DW, DC and NN were responsible for the literature research. JC, JN, CF, DW, DC and NN were responsible for clinical studies. JC, JN, CF, DW, DC and NN were responsible for experimental studies/data analysis. JC, JN, CF, DW, DC and NN were responsible for manuscript preparation. JC, JN, CF, DW, DC and NN were responsible for manuscript editing.

Conflicts of Interest

J. Conibear reports a relationship with Pfizer that includes: consulting or advisory, speaking and lecture fees, and travel reimbursement. J. Conibear reports a relationship with AstraZeneca PLC that includes: consulting or advisory, speaking and lecture fees, and travel reimbursement. J. Conibear reports a relationship with Merck Sharp and Dohme that includes: consulting or advisory, speaking and lecture fees, and travel reimbursement. J. Conibear reports a relationship with Amgen Inc that includes: consulting or advisory, speaking and lecture fees, and travel reimbursement. J. Conibear reports a relationship with Chugai Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes: consulting or advisory, speaking and lecture fees, and travel reimbursement. J. Conibear reports a relationship with Daiichi Sanyo that includes: consulting or advisory, speaking and lecture fees, and travel reimbursement. J. Conibear reports a relationship with Guardant Health Inc that includes: consulting or advisory, speaking and lecture fees, and travel reimbursement. J. Conibear reports a relationship with GlaxoSmithKline Plc that includes: consulting or advisory, speaking and lecture fees, and travel reimbursement. J. Conibear reports a relationship with Takeda Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes: consulting or advisory, speaking and lecture fees, and travel reimbursement. J. Conibear reports a relationship with Roche that includes: consulting or advisory, speaking and lecture fees, and travel reimbursement. N. Navani reports a relationship with Amgen Inc that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. N. Navani reports a relationship with AstraZeneca PLC that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. N. Navani reports a relationship with Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc that includes: consulting or advisory, speaking and lecture fees, and travel reimbursement. N. Navani reports a relationship with Bristol Myers Squibb that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. N. Navani reports a relationship with Guardant Health Inc that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. N. Navani reports a relationship with Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. N. Navani reports a relationship with Lilly that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. N. Navani reports a relationship with Merck Sharp and Dohme that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. N. Navani reports a relationship with Olympus that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. N. Navani reports a relationship with OncLive that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. N. Navani reports a relationship with PeerVoice that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. N. Navani reports a relationship with Pfizer that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. N. Navani reports a relationship with Takeda Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. D. West reports a relationship with AstraZeneca that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees.

References

- 1.Cancer Research UK Lung cancer statistics. 2022. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/lung-cancer Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 2.European Cancer Information System Estimates of incidence and mortality. 2022. https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/index.php Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 3.Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership National quality improvement programmes. 2022. https://www.hqip.org.uk/national-programmes/ Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 4.Royal College of Physicians Lung Cancer Clinical Outcomes Publication (LCCOP) 2021. https://nlca.rcp.ac.uk/content/misc/LCCOP%202021(2018).pdf Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 5.Royal College of Physicians National Lung Cancer Audit Annual Report. 2022. https://www.hqip.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/REF294_NLCA-Annual-Report-v20220113_FINAL.pdf Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 6.Pons A., Lim E. Thoracic surgery in the UK. J Thorac Dis. 2022;14(2):575–578. doi: 10.21037/jtd-21-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of Physicians National Lung Cancer Audit Annual Report. 2020. https://www.hqip.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/REF119_NLCA_AnnRep_2018-data_FINALv2.1.pdf Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 8.Royal College of Physicians National Lung Cancer Audit Organisational Audit Report. 2020. https://www.hqip.org.uk/resource/national-lung-cancer-audit-organisational-audit-report/#.Yra--hXMIQ9 Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 9.Royal College of Physicians National Lung Cancer Audit 2016: Key findings for patients and carers. 2017. https://www.hqip.org.uk/resource/national-lung-cancer-audit-2016-patients-carers/#.Yra-KxXMIQ9 Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 10.Royal College of Physicians National Lung Cancer Audit Outlier Policy 2019. 2019. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/file/20491/download Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 11.Royal College of Physicians National Lung Cancer Audit 2017: Key findings for patients and carers. 2018. https://www.hqip.org.uk/resource/national-lung-cancer-audit-2017-key-findings-for-patients-and-carers/#.Yra9IBXMIQ9 Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 12.Royal College of Physicians Spotlight report on curative intent treatment of stage I–IIIa non-small-cell lung cancer. 2020. https://www.hqip.org.uk/resource/spotlight-report-on-curative-intent-treatment-of-stage-i-iiia-non-small-cell-lung-cancer/#.Yra-oxXMIQ9 Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 13.Royal College of Physicians Spotlight report on molecular testing in advanced lung cancer. 2020. https://www.hqip.org.uk/resource/spotlight-report-on-molecular-testing-in-advanced-lung-cancer/#.Yra-pRXMIQ9 Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 14.Royal College of Physicians National Lung Cancer Audit Report 2014 Mesothelioma. 2014. https://www.hqip.org.uk/resource/national-lung-cancer-audit-report-2014-mesothelioma/#.YiHlNejP1hE Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 15.Maringe C., Spicer J., Morris M., Purushotham A., Nolte E., Sullivan R., et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(8):1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30388-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wasim U., Tahir M.J., Siddiqi A.R., Jabbar A., Ullah I. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on impending cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in the UK. J Med Virol. 2022;94(1):20–21. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faivre-Finn C., Fenwick J.D., Franks K.N., Harrow S., Hatton M.Q.F., Hiley C., et al. Reduced fractionation in lung cancer patients treated with curative-intent radiotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Oncol. 2020;32(8):481–489. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banfill K., Croxford W., Fornacon-Wood I., Wicks K., Ahmad S., Britten A., et al. Changes in the Management of patients having radical radiotherapy for lung cancer during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Clin Oncol. 2022;34(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2021.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NICE Lung cancer in adults. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs17 Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 20.NICE Lung cancer: diagnosis and management. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng122/resources/lung-cancer-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-66141655525573 Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 21.NHS The NHS Long Term Plan. 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.

- 22.Lung Clinical Expert Group . 2017. National optimal lung cancer pathway.http://content.smallerearthtech.co.uk/system/file_uploads/16086/original/National_Optimal_LUNG_Pathway_Aug_2017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Lung Cancer Audit 2022. https://www.lungcanceraudit.org.uk Available at: Accessed 19 June 2022.