Abstract

Introduction

Chestnut rot caused by the fungus Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi is a disease present in the world’s major chestnut growing regions. The disease is considered a significant threat to the global production of nuts from the sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa). Conventional fungicides provide some control, but little is known about the potential of biological control agents (BCAs) as alternatives to manage the disease.

Objective

Evaluate whether formulated BCAs and their secreted metabolites inhibit the in vitro growth of G. smithogilvyi.

Methods

The antifungal potential of BCAs was assessed against the pathogen through an inverted plate assay for volatile compounds (VOCs), a diffusion assay for non-volatile compounds (nVOCs) and in dual culture. Methanolic extracts of nVOCs from the solid medium were further evaluated for their effect on conidia germination and were screened through an LC–MS-based approach for antifungal metabolites.

Results

Isolates of Trichoderma spp., derived from the BCAs, significantly suppressed the pathogen through the production of VOCs and nVOCs. The BCA from which Bacillus subtilis was isolated was more effective in growth inhibition through the production of nVOCs. The LC–MS based metabolomics on the nVOCs derived from the BCAs showed the presence of several antifungal compounds.

Conclusion

The results show that G. smithogilvyi can be effectively controlled by the BCAs tested and that their use may provide a more ecological alternative for managing chestnut rot. The in vitro analysis should now be expanded to the field to assess the effectiveness of these alternatives for chestnut rot management.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11306-022-01933-4.

Keywords: Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi, Biological control, nVOCs, VOCs, Trichoderma spp., Bacillus subtilis

Introduction

One of the main threats to the production of nuts from sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) worldwide is the diseases caused by the fungus Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi (Ascomycete, Gnomoniaceae, Diaporthales). Incursions of the pathogen have been reported in several countries, including Australia (Shuttleworth et al., 2012), Chile (Cisterna-Oyarce et al., 2022), India (Dar and Rai, 2015), Spain (Trapiello et al., 2018), Italy (Visentin et al., 2012) and Switzerland (Dennert et al., 2015), among others. Under the right conditions of humidity and temperature, the pathogen colonises the starch-rich nut endosperm affecting its integrity and colour, which makes it unmarketable (Shuttleworth and Guest, 2017). Currently, in conventional farming, alternatives to growers for managing the disease include the application of fungicides pre-harvest (Australian Pesticides & Veterinary Medicines Authority, 2021; Chestnuts Australia, 2018) and sanitization of nuts with disinfectant post-harvest (Chestnuts Australia, 2017). However, these measures seem insufficient to control the incidence of G. smithogilvyi as disease peaks are still of considerable magnitude. For example, studies have found levels of nut infection of 91% in Switzerland (Dennert et al., 2015), 93.5% in Italy (Lione et al., 2015), and 70% in Australia (Shuttleworth et al., 2013). This demonstrates the significant risk to which chestnut production worldwide is exposed due to G. smithogilvyi. Therefore, there is an urgent need for the application of new strategies that could complement or replace those used currently to control the pathogen.

Biological control agents (BCAs) such as fungi and bacteria have emerged as an effective and environmentally friendly alternative to control several plant diseases (Minchev et al., 2021; Syed-Ab-Rahman et al., 2018). Within the vast microbial world, bacteria and fungi from the genus Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Trichoderma, for example, have been examined for their production of volatile and non-volatile metabolites that show antimicrobial activity. For example, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas putida and Trichoderma harzianum effectively suppressed the in vitro mycelial growth of Alternaria solani (Zhang et al., 2020), Colletotrichum gloeosporides (Sheoran et al., 2015) and Fusarium oxysporum (Li et al., 2018), respectively. Similarly, non-volatile compounds (nVOCs) secreted by B. subtilis, P. putida and T. harzianum showed significant growth inhibition of F. graminearum (Munakata et al., 2022), Colletotrichum acutatum (Moreira et al., 2014), and Magnaporthe oryzae (Zhao et al., 2020). However, there have been very limited studies on whether such microbially derived metabolites are active against G. smithogilvyi.

We examined several BCA formulations for their effectiveness in suppressing G. smithogilvyi growth. These formulations included species of the genera Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Trichoderma. We examined the effectiveness of VOCs and nVOCs derived from the BCAs in suppressing pathogen growth in vitro. Through high-resolution liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC–MS), a comparative study of the composition of the nVOCs produced by the BCAs was undertaken. There were clear differences in the metabolomes produced by the BCAs and which was closely linked to the differential activity observed. A new avenue for disease management that is more environmentally friendly and sustainable for the complex chestnut rot disease has thus been provided.

Materials and methods

G. smithogilvyi isolates and BCAs identification

Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi isolates, B15 and F1N1, were obtained from rotted nut tissues cultured onto potato dextrose agar (PDA, DifcoTM, New Jersey, USA). The BCAs (TRI, SUP and D25) used in this study correspond to commercially available formulations composed of a mixture of microorganisms including Trichoderma spp., Bacillus subtilis, and Pseudomonas putida. For molecular identification of the G. smithogilvyi and the fungi or bacteria in two (TRI, SUP) of the BCAs DNA was extracted from 5-day-old colonies grown on PDA at 23 °C using a commercial kit (Quick-DNA™ Fungal/Bacterial Miniprep Kit, Zymo Research) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For G. smithogilvyi the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region was amplified with primers ITS-5 (forward) and ITS-4 (reverse) according to White et al. (1990). Microbial profiling of BCAs was carried out by amplifying the ITS (fungi), 16S (bacteria) regions, and Sanger sequencing was performed by the Australian Genome Research Facility, Melbourne, Australia. All sequences were analysed using the NCBI-GenBank database.

BCAs preparation for analysis of VOCs and nVOCs

The BCAs were dissolved in sterile water (stH2O) to make a stock solution of 20 mg/mL or 20 μL/mL depending on the formulation format (Supplementary Table 1). The stock solution was activated for 4 h at 23 °C in the dark, filtered and a range of tenfold dilutions were made from 20 to 0.002 mg/mL (TRI, SUP) or 20 to 0.002 μL/mL (D25).

Effect of nVOCs on G. smithogilvyi growth in vitro

The effect of nVOCs derived from the cultured BCAs on G. smithogilvyi mycelial growth was evaluated following the procedure described by Steyaert et al. (2016) with some modifications (Fig. 1A). Firstly, sterile cellophane membrane discs (90 mm-in-diameter) were overlain on PDA using forceps. Then, 10 μL of each BCA concentration or stH2O for the control treatment were placed on a 5 mm-in-diameter sterile filter paper disc (no.1, Whatman®, Cytiva, UK) in the middle of the plate. Plates were sealed with parafilm and incubated at 23 °C in the dark for four days. After incubation, the cellophane membrane was removed carefully to ensure that BCA tissue did not contact the medium. Plates were then inoculated in the centre with a 6 mm-in-diameter plug of a five-day-old culture of G. smithogilvyi isolate B15 or F1N1. Plates were then sealed with Parafilm® (Amcor, Switzerland) and incubated at 23 °C in the dark for 6 days. Mycelial growth of the isolates was measured radially from the plug border to the edge of the colony by taking three measurements perpendicular to each other. The experiment was carried out with three replicates for each BCA × isolate × concentration combination and repeated 3 times.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the experimental procedures performed to evaluate the biological control agents against G. smithogilvyi. A Non-volatile compounds assay (nVOCs). See Sect. 2.3, B Volatile compounds (VOCs) assay. See Sect. 2.4, C Dual culture assay. See Sect. 2.5, D Extraction and analysis of metabolites through LC–MS. See Sect. 2.7

Effect of VOCs on G. smithogilvyi growth in vitro

The effect of VOCs on G. smithogilvyi mycelial growth was evaluated through an inverted Petri plate technique described by Dennis and Webster (1971) with some modifications (Fig. 1B). BCAs (10 μL) at each concentration or stH2O for control treatments were placed on a 5 mm-in-diameter sterile filter paper disc (Whatman No. 1) in the centre of the PDA plate. A second PDA plate was inoculated with a 6 mm-in-diameter plug from a five-day-old G. smithogilvyi culture of either isolate B15 or F1N1. The plate containing the pathogen was mounted facing downward on top of the plate containing the BCA or stH2O and then the two plates sealed with two layers of Parafilm®. Finally, plates were incubated at 23 °C in the dark for 6 days. After incubation, mycelial growth was measured as described above. The experiment was carried out with three replicates for each BCA × isolate × concentration combination and repeated 3 times.

Effect of BCAs on G. smithogilvyi growth in a dual culture assay

On one side of a PDA Petri dish (90 mm) a 6 mm-in-diameter agar plug of a five-day-old culture of G. smithogilvyi was placed 1 cm from the edge (Fig. 1C). On the opposite side, a 5 mm-in-diameter sterile filter paper disc that contained 10 μL of each BCA prepared at 20 mg/mL (TRI, SUP), 20 μL/mL (D25) and stH2O for the control treatment was also placed 1 cm from the edge. Plates were then sealed with parafilm and incubated at 23 °C in the dark. Growth area of each isolate was measured following 6 days of incubation and then again at 8 days. Growth area of each isolate was determined using a free software program (ImageJ, version 1.51j8, U.S. National Institutes of Health, USA). The experiment was carried out with three replicates and repeated 3 times.

Extraction of nVOCs from solid medium

The BCAs were grown on PDA media overlayed with cellophane membrane at 23 °C for 4 days. Then, the cellophane membrane containing BCAs was removed, and 5 g/plate of the medium was used for nVOCs extraction (Fig. 1D). The agar medium sample was placed in 10 mL capped culture tubes, frozen with liquid nitrogen for 4 min, and then freeze dried (VirTis BenchTop Pro freeze dryer, SP scientific, USA) for 48 h. The instrument was set at − 60 °C with a vacuum pressure of 200 m Torr. Freeze-dried samples were resuspended and adjusted to 50 mg/mL with 100% methanol (HPLC grade, Merck, Germany). The solution was then subjected to ultrasonication (Power sonic 410, Hwashin technology, South Korea) set at 30 °C for 60 min. Then, 1.5 mL of the solution was transferred to a 2 mL centrifuge tube to pellet undissolved particles by centrifugation at 11,000 rpm for 5 min. Finally, 300 μL of deionised water was added to 700 μL of the supernatant and kept in 2 mL glass vials at − 20 °C until analysis by LC–MS. Five plates treated with BCAs or stH2O were used as technical replicates for analysis.

High-performance liquid chromatography fractionation of nVOCs

Samples were fractionated using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system with a diode array detector (UltiMate™ 3000 BioRS, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). The LC parameters were as follows: column 4.6 × 150 mm, 3 µm Luna C18 (2) (Phenomenex, USA), column temperature 25 °C, flow rate 0.75 mL/min, with gradient elution. Mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid in water, mobile phase B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (LC–MS grade solvents used). The initial mobile phase composition was 5% B which linearly increased to 100% B over 14 min with a 3-min hold at 100% B then re-equilibration for 5 min at 5% B, giving a total run time of 22 min. The diode array detector was set from 220 to 800 nm. Sample injection volume was 25 µL and fractions were collected every 1 min from 1 to 16 min.

Analysis of nVOCs from solid media and HPLC fractions

Samples were analyzed using an ultra-high resolution mass spectrometer coupled with liquid chromatography (LC–MS. Vanquish Flex UHPLC coupled with an OrbitrapExploris-240, ThermoFisher Scientific). The LC parameters were as follows: column 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 µm C18 Zorbax Elipse plus (Agilent, USA), column temperature 30 °C, flow rate 0.4 mL/min, with gradient elution. Mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid in water, mobile phase B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile, LC–MS grade solvents were used. The initial mobile phase composition was 5% B which held for 1 min then linearly increased to 100% B over 9 min with a 2 min hold at 100% B then re-equilibration for 3 min at 2% B, giving a total run time of 15 min. The H-ESI source settings were: ion spray voltage 3800 V, sheath gas 50 (arb. units), sweep gas 1 arb, ion transfer tube 325 °C, vaporizer temperature 350 °C. The MS was operated in data dependant MS/MS mode with a full scan between 90 and 1350 m/z at a resolution of 120,000 and MS/MS scans with a resolution of 15,000. The cycle time was 0.6 cycles per second (1 full scan 7 MS/MS scans per 0.6 s cycle). Three normalised collision energies were used for MS/MS (20, 40, 60 NCE) and the MS/MS threshold was 5000 counts. The injection volume of sample extracts was 5 µL. The Easy-IC internal calibration was used giving sub-1 ppm mass accuracy. Data was collected in both positive and negative ionization mode in separate runs.

Annotation of nVOCs detected by LC–MS

Annotation, chromatographic deconvolution, library searching, and data visualization of putative compounds was performed with the software program Compound Discoverer 3.3 (ThermoFisher Scientific). Compounds were annotated based on comparing their calculated elemental composition against that of 220 compounds from a manually constructed library of compounds reported for Bacillus, Pseudomonas and Trichoderma species in the literature. Additionally, compounds were compared against the ChemSpider database. Elucidation of putative compound structures was carried out by applying the software-integrated function Fragment Ion Search (FISh) scoring algorithm which matches fragments ions to the theoretical structure of the parent molecule (Wang et al., 2019; Welling et al., 2021).

Antifungal activity of crude extracts against G. smithogilvyi

The fungicidal activity of methanolic crude extracts of the BCAs was evaluated against G. smithogilvyi isolate B15 by means of a disc diffusion assay on PDA. Firstly, the methanolic nVOCs extract was concentrated by evaporating the solvent in a vacuum concentrator (model RVC 2–18 CDplus, Christ, Germany) set a 35 °C for 2 h and adjusted to 500 mg/mL with 70% methanol in water. Then, 150 μL of a conidial suspension (1.7 × 106 conidia/mL) of isolate B15 was dispersed on the surface of the medium in each Petri plate (90 mm). Filter paper discs (5 mm-in-diameter) were equidistantly placed onto the medium and then inoculated with 10 μL of the crude extract or 70% methanol in water as the control. Plates were incubated at 23 °C in the dark for 3 days and the diameter of the zone of inhibition was measured across two sections perpendicular to each other. The experiment was performed in quadruplicate and repeated twice.

Evaluation of antifungal activity of HPLC fractions

The collected fractions were evaluated for their potential to inhibit G. smithogilvyi isolate B15 mycelial growth on PDA. Fractions were vacuum evaporated as described above and resuspended in 100 μL of 70% methanol in water. Then, 30 μL of each fraction or 70% methanol in water for the control were evenly dispersed using a sterile L-shaped spreader on each of three individual PDA plates (60 mm-in-diameter). A plug of 6 mm-in-diameter from a five-day-old G. smithogilvyi isolate B15 culture was then placed on the agar surface in the centre of the plate. Plates were incubated at 23 °C in the dark for 3 days and the colony area was measured using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis and data visualisation

Statistical analysis and graphical visualisation were performed using a commercial software program (GraphPad Prism, vers. 8.0.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software, USA). The effect of the VOCs, nVOCs and dual culture on mycelial growth of both G. smithogilvyi isolates were evaluated by analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA). The mean of each treatment was subjected to multiple comparisons with Dunnett’s post-hoc test at a 5% significance level (p = 0.05). Disc diffusion assay results were compared with one-way ANOVA with the same post-hoc test. UpSet plots were used to show distribution and correlation of unique and shared metabolites between BCAs and were constructed with Python (Lex et al., 2014).

Results

Effect of nVOCs on G. smithogilvyi mycelial growth

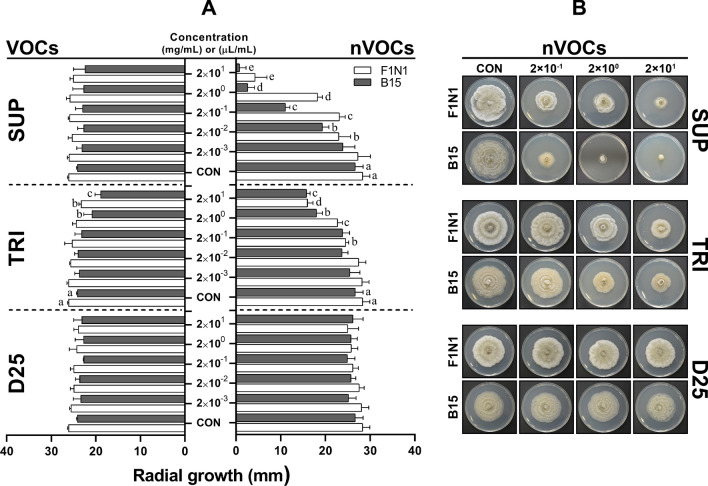

The antifungal properties of the nVOCs secreted by BCAs on PDA medium differed greatly in their effectiveness in reducing G. smithogilvyi mycelial growth (Fig. 2A, B). The results showed that the nVOCs exuded by SUP were comparatively more effective in reducing the mycelial growth of both isolates than of TRI and D25. There were significant differences (p < 0.05) in growth compared to the control treatment at concentrations of SUP that ranged between 2 × 10–2 and 2 × 101 (mg/mL). Treatment with the highest concentration resulted in the minimum radial growth for both isolates, with F1N1 reaching 4.27 ± 1.5 mm and B15 0.81 ± 0.81 mm compared with the control of 28.36 ± 1.6 mm (F1N1) and 26.68 ± 1.7 mm (B15). The second most effective nVOCs that inhibited mycelial growth were produced by TRI. Significant differences (p < 0.05) were found between the control and treatments at concentrations ranging from 2 × 10–1 to 2 × 101 (mg/mL). Again, at the highest concentration of TRI, both isolates were restricted to growth of 16.0 ± 0.7 mm (F1N1) and 15.8 ± 0.4 mm (B15).

Fig. 2.

Effect of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and non-volatile compounds (nVOCs) on mycelial growth of G. smithogilvyi isolates B15 and F1N1. A Shows the effect of VOCs (Left) and nVOCs (right) on the radial growth of the isolates at each concentration tested (centre). B Representation of the effect of nVOCs secreted by the highest three BCAs concentrations on the mycelial growth of both isolates. Plates were incubated at 23 °C in the dark for six days. Means ± SEM labelled with the same letter are not significantly different to the control according to Dunnett’s test at p = 0.05

Effect of VOCs on G. smithogilvyi mycelial growth

The inverted Petri dish assay showed that the VOCs emitted by TRI were the most effective in controlling the mycelial growth of both G. smithogilvyi isolates (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 1). Significant differences (p < 0.05) in growth compared with the control were found with TRI treatments at concentrations between 2 × 100 and 2 × 101 (mg/mL) with colony growth of 23.3 ± 0.2 mm (F1N1) and 18.9 ± 0.6 mm (B15) at the concentration 2 × 101 (mg/mL). Both D25 and SUP BCAs did not significantly reduce the mycelial growth of either of the isolates.

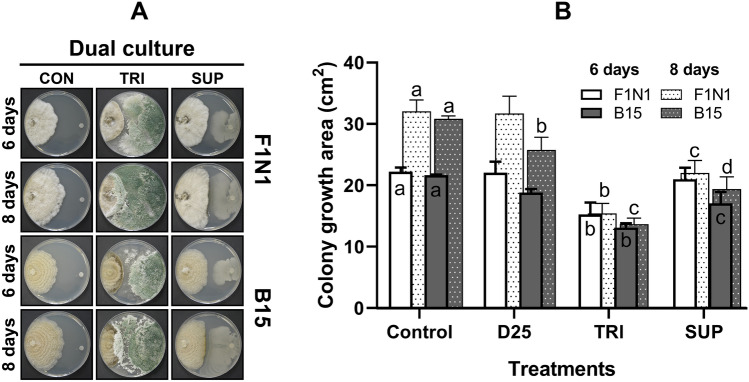

Effect of BCAs on G. smithogilvyi growth in dual culture

The antagonistic activity of BCAs against G. smithogilvyi isolates was assessed in vitro through a dual culture assay on PDA after 6 and 8 days of incubation. Our results showed that the selected BCAs suppressed significantly (p < 0.05) the pathogen mycelial growth compared to the control in a time-depended manner (Fig. 3A, B). TRI was the most rapid and effective BCAs in limiting significantly (p < 0.05), compared with the controls, the growth of the isolates to 15.2 ± 1.0 and 13.1 ± 0.3 cm2 for F1N1 and B15 at 6 days, respectively (Fig. 3B). The intense antagonistic activity of TRI limited the isolates from further growth at 8 days to 15.4 ± 0.9 cm2 (F1N1) and 13.6 ± 0.5 cm2 (B15). Of particular interest is the apparent impact of TRI on the viability at both 6 and 8 days, G. smithogilvyi culture appeared to be killed, as shown by the intense darkening of the culture margin.

Fig. 3.

Effect of the biological control agents TRI and SUP on the growth of G. smithogilvyi isolates B15 and F1N1 evaluated in a dual culture assay. A Inhibition of growth of G. smithogilvyi due to exposure to TRI and SUP at 6 and 8 days in the dual culture assay compared with controls. Note for the BCA present in TRI overgrowing G. smithogilvyi colony and the halo of inhibition displayed under the SUP treatment. B Growth area of the isolates measured after 6 and 8 days. Means ± SEM labelled with different letters are significantly different to the control according to Dunnett’s test at p = 0.05

Biological control agent SUP was the second most effective at limiting G. smithogilvyi colony growth. We observed the earliest effect of SUP on isolate B15 where development was suppressed to 17.0 ± 1.0 cm2 at 6 days. In contrast, SUP did not have a significant effect on inhibiting isolate F1N1 colony growth at 6 days. However, SUP was significantly more effective in limiting the growth of both isolates to 22.0 ± 1.1 cm2 (F1N1) and 19.3 ± 1.1 cm2 (B15) compared to the control after 8 days. On the other hand, D25 was only effective in restricting the growth of isolate B15 to 25.7 ± 1.1 cm2 after 8 days compared to the control treatment. The growth area of F1N1 did not differ statistically from the control after being challenged with D25.

Molecular identification of the isolated biological control agents

Although the commercial products tested were labelled as containing a number of species of Trichoderma and/or Bacillus and Pseudomonas, in the in vitro assays we only found Trichoderma-like species (TRI) and Bacillus-like species (SUP) to be present. These species were found to be effective in suppressing growth of G. smithogilvyi in vitro. Therefore, we further characterised them via Sanger sequencing. The sequencing results showed that TRI yielded sequences that were 100% identical to T. harzianum (taxid: 5544) and T. lignorum (syn. viride) (taxid: 5547) and 98.3% identity to T. koningii (taxid: 97,093). On the other hand, SUP yielded sequences with 100% identity to the Bacillus subtilis (taxid: 1423). Sequences for Trichoderma sp. and Pseudomonas putida were not detected in SUP (Supplementary Table 2).

Identification of nVOCs from solid media through LC–MS

The LC–MS analysis of the positive and negative ionization modes yielded a total of 2789 and 2898 nVOCs respectively. The overall heat maps derived from the Pearson clustering under the positive (Fig. 4A) and negative (Fig. 4C) ionization modes showed the differences in the types of metabolites produced by each BCA. Principal component analysis (PCA) further confirmed the differences between BCAs by clustering the samples in three distinct groups. In the positive ionization mode PCA1 and PCA2 explained 51.3 and 25.7% of the total variance, respectively (Fig. 4C). For the negative ionisation data, PCA1 and PCA2 explained 49.6 and 28.6% of the total variance, respectively (Fig. 4D). Although we used the same amount of crude extract from each BCA for analysis, we observed differences in the total number of metabolites detected. We used an UpSet plot to examine the number of unique and common metabolites across the three BCAs in the positive (Fig. 4E) and negative ionisation modes (Fig. 4F). The majority of nVOCs were molecules present only in SUP. This BCA contributed with 1129 (40.4%) and 1355 (46.7%) to the total number of compounds detected in the positive and negative ion modes respectively. Of the total number of nVOCs detected 26.3% were unique to TRI in the positive ion mode and 17.8% in the negative ion mode. The BCA D25 had the least complex molecular profile with only 4.5% of unique compounds from the total metabolites detected in the positive mode and 4.1% in the negative ionization mode. Moreover, the UpSet plot analysis showed that 221 (7.9%) positively and 357 (12.3%) negatively ionized compounds were commonalities between the three BCAs. On the other hand, about 20% and 18% of the metabolome were commonalities between two of the three BCAs under the positive and negative ionization modes, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of the non-volatile compounds (nVOCs) profile of biological control agents SUP, D25 and TRI for the positive (+) and negative (−) ionisation modes. A, B Heat map analysis, C, D principal component analysis (PCA) and E, F UpSet plots for the positive (+) and (−) modes respectively. Heat maps display the normalized compounds abundance in a colour code: low level (green) and high level (red). Both heat maps were clustered with Person’s distance function, and the median was used as the linkage method. UpSet plots show the distribution of nVOCs unique to each BCA (first three bars) and shred between two or three BCAs (last four bars) (Color figure online)

Based on the library search and the FISh scoring assigned to each molecular structure, we were able to putatively annotate 28 nVOCs with a FISh coverage greater than 30 (Table 1). These compounds represented various chemical classes with known bioactivity including aldehydes (one detected), amides (1), aminoalkyl citrates (1), butenolides (1), lipopeptides (4), organic acids (2), peptides (3), polyketides (3), pyrones (3) and terpenes (5). Surprisingly none of these metabolites were shared by the BCAs. Nevertheless, some of the known antimicrobial metabolites detected were for TRI: 6-pentyl-2H-pyran-2-one (C10H14O2) peak at m/z = 167.1065 [M + H]+1, farnesol (C15H26O) at m/z = 223.2055 [M + H]+1, cyclonerodiol (C15H28O2) peak at m/z = 241.2162 [M + H]+1 and benzoic acid (C7H6O2) with peak at m/z = 123.0439 [M + H]+1. Some of the featured metabolites detected in SUP were: surfactin B (C52H91N7O13) peak m/z = 1022.6745 [M + H]+1, surfactin C (C53H93N7O13) at peak m/z = 1036.6899 [M + H]+1, cyclo(L-Val-L-Pro) (C10H16N2O2) at m/z = 197.1284 [M + H]+1 and myriocin at m/z 400.2849 [M + H]+1 (See Supplementary Fig. 2 for myriocin as an example for determination of FISh score). On the other hand, we identified in D25 the following antimicrobial metabolites: 3,7-dimethyloct-6-enal (C10H18O) peak at m/z 137.1324 [M + H–H2O]+1, 4-hydroxycoumarin (C9H6O3) at m/z = 163.0389 [M + H]+1, tryptophol (C10H11NO) peak at m/z = 162.0913 [M + H]+1, and marinactinone B (C16H26O3) at m/z = 267.1955 [M + H]+1. The chemical structures of these compounds are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3

Table 1.

Non-volatile compounds (nVOCs) produced by formulated BCAs D25, SUP and TRI detected by LC–MS

| Tentative compound identification | Molecular formula | Cal. Mol.a mass | m/z | Δ mass (ppm) | FISh coverage | Ion | RT (min) | D25 | SUP | TRI | Activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aldehyde | ||||||||||||

| 3,7-dimethyloct-6-enal | C10H18O | 154.1357 | 137.1324 | − 0.27 | 80 | [M + H-H2O]+1 | 6.4 | ✓b | – | – | Antibacterial | Singh et al. (2018) |

| Amides | ||||||||||||

| Bacillamidin B | C19H35NO5 | 357.2515 | 358.2588 | 0.0 | 42 | [M + H]+1 | 7.0 | – | ✓ | – | Antibacterial | Zhou et al. (2018) |

| Aminoalkyl citrates | ||||||||||||

| Viridiofungin A | C31H45NO10 | 591.3040 | 592.3113 | − 0.53 | 76 | [M + H]+1 | 7.8 | – | – | ✓ | Antifungal | El-Hasan et al. (2009) |

| Butenolides | ||||||||||||

| 5-hydroxyvertinolide | C14H18O5 | 266.1154 | 289.1046 | 0.16 | 66 | [M + Na]+1 | 6.0 | – | – | ✓ | Antifungal | Derntl et al. (2017) |

| Lipopeptides | ||||||||||||

| Fengycin | C72H110N12O20 | 1462.7953 | 732.4049 | − 0.38 | 33 | [M + 2H]+2 | 6.9 | – | ✓ | – | Antifungal | Romero et al. (2007) |

| Surfactin A | C51H89N7O13 | 1007.6515 | 1008.6589 | − 026 | 43 | [M + H]+1 | 10.7 | – | ✓ | – | Antifungal | Sarwar et al. (2018) |

| Surfactin B | C52H91N7O13 | 1021.6671 | 1022.6745 | − 0.29 | 85 | [M + H]+1 | 11.1 | – | ✓ | – | Antibacterial | Gun Hee et al. (2011) |

| Surfactin C | C53H93N7O13 | 1035.6826 | 1036.6899 | − 0.45 | 56 | [M + H]+1 | 11.8 | ✓ | Antifungal | Aleti et al. (2016) | ||

| Organic acids | ||||||||||||

| 2-methylbutanoic acid | C5H10O2 | 102.0681 | 101.0608 | 0.16 | 38 | [M-H]−1 | 1.2 | ✓ | – | – | Antibacterial | Hayashida-Soiza et al. (2008) |

| Benzoic acid | C7H6O2 | 122.0367 | 123.0439 | − 0.55 | 80 | [M + H]+1 | 4.7 | ✓ | Antifungal | Nehela et al. (2021) | ||

| Peptides | ||||||||||||

| Bacilysin | C12H18N2O5 | 270.1215 | 269.1143 | 0.08 | 47 | [M-H]−1 | 0.9 | – | ✓ | – | Antibacterial | Wu et al. (2015) |

| Cyclo(L-Val-L-Pro) | C10H16N2O2 | 196.1211 | 197.1284 | − 0.08 | 61 | [M + H]+1 | 3.9 | – | ✓ | – | Antibacterial | Zin et al. (2020) |

| Myriocin | C21H39NO6 | 401.2777 | 400.2849 | − 0.06 | 72 | [M + H]+1 | 8.8 | – | ✓ | – | Antifungal | Wang et al. (2021) |

| Polyketides | ||||||||||||

| Macrolactin A | C24H34O5 | 402.2407 | 403.2479 | 0.26 | 35 | [M + H]+1 | 5.2 | – | ✓ | – | Antibacterial | Chen et al. (2019) |

| Macrolactin-O | C30H44O10 | 564.2937 | 609.2919 | 0.56 | 53 | [M + FA-H]−1 | 6.0 | – | ✓ | – | Antibacterial | Zheng et al. (2007) |

| Oxydifficidin | C31H45O7P | 560.2901 | 1143.5695 | − 0.34 | 30 | [2 M + Na]+1 | 8.6 | – | ✓ | – | Antibacterial | Im et al. (2020) |

| Pyrones | ||||||||||||

| 6-pentyl-2H-pyran-2-one | C10H14O2 | 166.0993 | 167.1065 | − 037 | 87 | [M + H]+1 | 7.2 | – | – | ✓ | Antifungal | Jin et al. (2020) |

| Viridepyronone | C10H12O3 | 180.0786 | 181.0858 | − 0.20 | 76 | [M + H]+1 | 5.0 | – | – | ✓ | antifungal | Evidente et al. (2003) |

| Marinactinone B | C16H26O3 | 266.1882 | 267.1955 | 0.17 | 60 | [M + H]+1 | 8.3 | ✓ | – | – | Cytotoxic | Wang et al. (2011) |

| Terpenes | ||||||||||||

| Cyclonerodiol | C15H28O2 | 240.2089 | 241.2162 | 0.04 | 83 | [M + H]+1 | 6.1 | – | – | ✓ | Antifungal | Wu et al. (2011) |

| Farnesol | C15H26O | 222.1982 | 223.2055 | − 0.37 | 87 | [M + H]+1 | 7.1 | – | – | ✓ | Antifungal | Cotoras et al. (2013) |

| Trichocarane A | C15H26O3 | 254.1881 | 255.1954 | − 0.14 | 50 | [M + H]+1 | 6.0 | – | – | ✓ | G. inhibitor | Macías et al. (2000) |

| Trichocarotin C | C15H22O3 | 250.1569 | 251.1642 | 0.06 | 75 | [M + H]+1 | 6.0 | – | – | ✓ | Antimicroalgal | Shi et al. (2018) |

| Trichocitrin | C20H28O | 284.2140 | 258.2213 | 0.08 | 33 | [M + H]+1 | 9.8 | – | – | ✓ | Antibacterial | Liang et al. (2016) |

| Others | ||||||||||||

| 4-hydroxycoumarin | C9H6O3 | 162.0316 | 163.0389 | − 0.43 | 66 | [M + H]+1 | 6.2 | ✓ | – | – | Antibacterial | Yang et al. (2016) |

| Formononetin | C16 H12O4 | 268.0736 | 291.0628 | 0.16 | 33 | [M + Na]+1 | 6.2 | ✓ | – | – | Antifungal | das Neves et al. (2016) |

| Indirubin | C16H10N2O2 | 262.0742 | 263.0815 | 0.08 | 50 | [M + H]+1 | 4.4 | – | – | ✓ | Antifungal | Ponnusamy et al. (2010) |

| Tryptophol | C10H11NO | 161.0840 | 162.0913 | − 0.19 | 62 | [M + H]+1 | 5.2 | ✓ | – | – | Antifungal | Singkum et al. (2019) |

b() compound present, (–) compound absent

aCalculated molecular mass

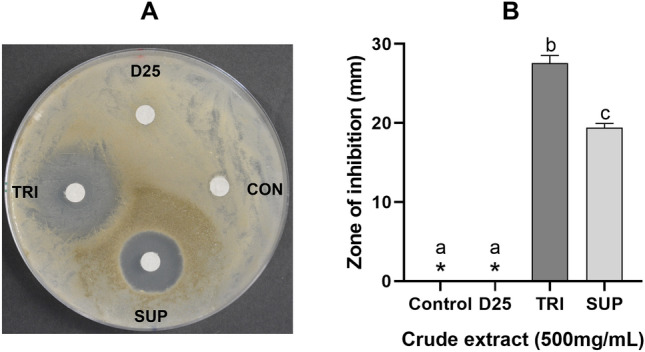

Bioactivity of BCAs crude extracts and assessment of their fractionation

Methanolic crude extracts (500 mg/mL) evaluated through the disc diffusion assay showed that TRI and SUP extracts were significantly effective (p < 0.05) at inhibiting conidial germination and subsequent mycelial growth of G. smithogilvyi isolate B15 (Fig. 5A). These results clearly show the potential effect of nVOCs on suppressing the conidial germination process. In particular, the crude extract obtained from TRI was the most effective inhibitor and displayed a zone of inhibition of 27.6 ± 1.3 mm (Fig. 5B). On the other hand, the methanolic extract derived from SUP was the second most effective and induced a zone of inhibition of 19.6 ± 0.6 mm. In contrast, the crude extract derived from D25 did not show any effect on inhibiting conidia germination and mycelial growth.

Fig. 5.

Disc diffusion assay of BCAs methanolic crude extracts (500 mg/mL) and effect on G. smithogilvyi conidia germination and mycelial growth. A A representative plate displaying the zone of inhibition of each crude extract compared to the control treatment. B Size of the zone of inhibition for each BCA. Means ± SEM labelled with different letters are significantly different to the control according to Dunnett’s test at p = 0.05. (*) Represents means with a value of zero

The heat map derived from LC–MS data for the positive ionization mode showed that each BCA was distinct in terms of its fractionation profile and that each fraction within a BCA was also quite distinct. All targeted compounds were detected in at least one of the fractions. However, we found that some metabolites were detected in more than one fraction. For example, 5-hydroxyvertinolide was detected in fractions 9 and 10. Similarly, Viridiofungin A was detected in fractions 13 and 14 (Supplementary Fig. 4). This resulted in the fractions having on average 599 (SUP) and 882 (TRI) compounds (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, even though the same amount of fractionated crude extract was applied to each plate, no observable reduction in mycelial growth was found (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Discussion

The present study provides new information on the evaluation and use of biocontrol-based products to control G. smithogilvyi as an alternative for the management of the causal agent of nut rot in chestnuts. The most significant antifungal activity was found for the nVOCs produced by the BCAs. We found that Trichoderma species- and B. subtilis-derived metabolites suppressed G. smithogilvyi mycelial growth and conidial germination. Analysis of nVOCs through LC–MS revealed several antimicrobial compounds from various chemical classes, including aldehydes, aminoalkyl citrates, butenolides, lipopeptides, organic acids, peptides, polyketides, pyrones and terpenes. Our analysis of VOCs showed that only that produced by the formulation TRI were effective in inhibiting pathogen growth. Due to the very limited impact of VOCs on G. smithogilvyi and only shown for the BCA TRI under the experimental conditions used here, we have focused on a deeper analysis of nVOCs which, in contrast, showed much stronger bioactivity.

The analysis of TRI-derived nVOCs yielded > 1200 molecules in both ionisation modes, from which we detected eleven known antimicrobial compounds based on their structural FISh scores. For example, the pyrone, 6-pentyl-2H-pyran-2-one (6-PP) has been found to be produced by several Trichoderma species, including T. atroviride (Garnica-Vergara et al., 2016), T harzianum (Rubio et al., 2009), T. koningii (Simon et al., 1988) and T. viride (Jeleń et al., 2014). This metabolite showed a significant antifungal effect against the ascomycete Cylindrocarpon destructans, the causal agent of root rot in Panax notoginseng (Chinese ginseng) (Jin et al., 2020). Similarly, evaluation of 6-PP at high concentrations showed significant mycelial growth inhibition of Fusarium culmorum in vitro (Jeleń et al., 2014). Another known antimicrobial compound detected in the nVOCs derived from the Trichoderma species present in TRI was cyclonerodiol. The effectiveness of cyclonerodiol in controlling fungal pathogens has been demonstrated against the ascomycetes F. avenaceum (Wu et al., 2011), Magnaporthe oryzae and the oomycete Phytophthora infestans (Ngo et al., 2021). Our detection of cyclonerodiol indicates that this antifungal compound may have a role in suppression of G. smithogilvyi growth.

The analysis of nVOCs produced by B. subtilis present in the product SUP yielded > 1500 metabolites in positive and negative ion modes. Based on the FISh scoring, the most prominent metabolites detected were eleven antimicrobial compounds belonging to various chemical groups including amides, lipopeptides, peptides and polyketides. Within the lipopeptides we identified fengycin and three surfactins (A, B and C). These compounds are cyclic lipopeptides produced by a broad range of Bacillus species (Théatre et al., 2021). Studies have shown that these lipopeptides cause cell apoptosis by inducing structural and functional changes in the plasma membrane, cell wall and mitochondrial membrane (Qi et al., 2010; Song et al., 2013). The effectiveness of fengycin and surfactins as antimicrobial compounds has also been shown against a broad range of plant pathogens including bacteria and fungi. For example, Romero et al. (2007) found that fengycin was highly effective at inhibiting conidial germination of Podosphaera fusca the causal agent of powdery mildew in cucurbits.

In addition to the above lipopeptides, surfactin A had shown strong inhibition against a number of Fusarium species associated with rice bakanae disease (Sarwar et al., 2018). Surfactin B was effective against the bacterium Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in vitro (Gun Hee et al., 2011) and surfactin C isomers showed significant inhibition of mycelial growth of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici and Aspergillus niger (Romano et al., 2013). Finally, another relevant metabolite that we detected was the peptide, myriocin, which has been shown to be effective at inhibiting growth of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum (Wang et al., 2021) and F. graminearum (Shao et al., 2021). Similar to fengycin and surfactins, myriocin acts in the fungal plasma membrane by decreasing its fluidity and destroying its integrity (Wang et al., 2021).

The variation observed in the number of unique metabolites produced by the different BCAs is not uncommon, as their synthesis is influenced by multiple factors. For example, in fungi the type of metabolites depends on the development stage of the species (Calvo et al., 2002) and their number can be increased upon the interaction with other species (Akone et al., 2016; Li et al., 2020). Similarly, the amount and type of metabolites produced in bacteria such as Bacillus spp. depends on their growth cycle, with significant increases during the stationary phase (Ayed et al., 2015; Horak et al., 2019). Regardless of the factors that induced the differences in the number of metabolites produced by the BCAs, we have shown that BCAs produced multiple compounds with antifungal properties that are likely to be active against G. smithogilvyi. There are almost certainly unknown antimicrobial compounds present in our dataset which could be further investigated through fractionation and application to plates. On the other hand, our HPLC fractionation of crude extract showed that the contribution of individual compounds, such as those discussed above, to the inhibition of fungal growth needs to be further explored. Also, any inhibition is likely due to a combination of compounds or higher concentration of individual metabolites, as some compounds were split over more than one fraction resulting in dilution. Furthermore, the role, if any, of the VOCs secreted by the tested BCAs in suppression of G. smithogilvyi growth is still uncertain and could be the subject of further studies either on the tested BCAs or other formulations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study has revealed the potential of formulated biological control agents to suppress the growth of G. smithogilvyi under in vitro conditions. The Trichoderma species present in TRI can effectively suppress the pathogen through the secretion of VOCs and nVOCs. In addition, we showed that the B. subtilis contained in SUP displayed a strong antifungal activity against the pathogen due to secreted nVOCs alone. Our in vitro studies need now to be expanded into the field to accelerate the implementation of these eco-friendly alternatives for the management of the causal agent of chestnut rot.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the generous funding support of the Premium Chestnut Association Australia and Deakin University in the undertaking of this research project. We would also like to thank Andrew Goh in Deakin eSolutions for support in the use of UpSet plots, and Frank Merenda from Zadco for donating some of the biological products evaluated in this study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by MS, DLC, and DC. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MS and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to commercial confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human and/or animal participants performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Matias Silva-Campos, Email: msilvacampos@deakin.edu.au.

Damien L. Callahan, Email: damien.callahan@deakin.edu.au

David M. Cahill, Email: david.cahill@deakin.edu.au

References

- Akone SH, Mándi A, Kurtán T, Hartmann R, Lin W, Daletos G, Proksch P. Inducing secondary metabolite production by the endophytic fungus Chaetomium sp. through fungal–bacterial co-culture and epigenetic modification. Tetrahedron. 2016;72:6340–6347. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2016.08.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aleti G, Lehner S, Bacher M, Compant S, Nikolic B, Plesko M, Schuhmacher R, Sessitsch A, Brader G. Surfactin variants mediate species-specific biofilm formation and root colonization in Bacillus. Environmental Microbiology. 2016;18:2634–2645. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority. (2021). Public chemical registration information system search. Retrieved September 01, 2021, from https://portal.apvma.gov.au/pubcris

- Ayed HB, Maalej H, Hmidet N, Nasri M. Isolation and biochemical characterisation of a bacteriocin-like substance produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens An6. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. 2015;3:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo AM, Wilson RA, Bok JW, Keller NP. Relationship between secondary metabolism and fungal development. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews: MMBR. 2002;66:447–459. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.447-459.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Liu T, Wei M, Zhu Z, Liu W, Zhang Z. Macrolactin a is the key antibacterial substance of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens D2WM against the pathogen Dickeya chrysanthemi. European Journal of Plant Pathology. 2019;155:393–404. doi: 10.1007/s10658-019-01774-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chestnuts Australia. (2017). Nuts & Burrs/regular. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from https://www.chestnutsaustraliainc.com.au/publications/

- Chestnuts Australia. (2018). Chestnut industry Newsletter—technical. Retrieved December 01, 2019, from https://www.chestnutsaustraliainc.com.au/latest-news/

- Cisterna-Oyarce V, Carrasco-Fernández J, Castro JF, Santelices C, Muñoz-Reyes V, Millas P, Buddie AG, France A. Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi: Identification, characterization and incidence of the main pathogen causing brown rot in postharvest sweet chestnut fruits (Castanea sativa) in Chile. Australasian Plant Disease Notes. 2022;17:2. doi: 10.1007/s13314-022-00450-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cotoras M, Castro P, Vivanco H, Melo R, Mendoza L. Farnesol induces apoptosis-like phenotype in the phytopathogenic fungus Botrytis cinerea. Mycologia. 2013;105:28–33. doi: 10.3852/12-012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar MA, Rai M. Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi, a canker causing pathogen on Castanea sativa: First report. Mycosphere Journal of Fungal Biology. 2015;6:327–336. doi: 10.5943/mycosphere/6/3/8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- das Neves MVM, da Silva TMS, Lima EDO, da Cunha EVL, Oliveira EDJ. Isoflavone formononetin from red propolis acts as a fungicide against Candida sp. Brazilian. Journal of Microbiology. 2016;47:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennert FG, Broggini GAL, Gessler C, Storari M. Gnomoniopsis castanea is the main agent of chestnut nut rot in Switzerland. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2015 doi: 10.14601/Phytopathol_Mediterr-14712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C, Webster J. Antagonistic properties of species-groups of Trichoderma: II. Production of volatile antibiotics. Transactions of the British Mycological Society. 1971;57:41–48. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1536(71)80078-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derntl C, Guzmán-Chávez F, Mello-de-Sousa TM, Busse H-J, Driessen AJM, Mach RL, Mach-Aigner AR. In vivo study of the sorbicillinoid gene cluster in Trichoderma reesei. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2017 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hasan A, Walker F, Schöne J, Buchenauer H. Detection of viridiofungin A and other antifungal metabolites excreted by Trichoderma harzianum active against different plant pathogens. European Journal of Plant Pathology. 2009;124:457–470. doi: 10.1007/s10658-009-9433-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evidente A, Cabras A, Maddau L, Serra S, Andolfi A, Motta A. Viridepyronone, a new antifungal 6-substituted 2H-pyran-2-one produced by Trichoderma viride. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51:6957–6960. doi: 10.1021/jf034708j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnica-Vergara A, Barrera-Ortiz S, Muñoz-Parra E, Raya-González J, Méndez-Bravo A, Macías-Rodríguez L, Ruiz-Herrera LF, López-Bucio J. The volatile 6-pentyl-2H-pyran-2-one from Trichoderma atroviride regulates Arabidopsis thaliana root morphogenesis via auxin signaling and ethylene insensitive 2 functioning. New Phytologist. 2016;209:1496–1512. doi: 10.1111/nph.13725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gun Hee S, Jiyoung K, Maria John M, Sarah L, Hyang Yeon K. antimicrobial compounds profile during cheonggukjang fermentation against Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2011;21:1147–1150. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1109.09075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashida-Soiza G, Uchida A, Mori N, Kuwahara Y, Ishida Y. Purification and characterization of antibacterial substances produced by a marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis strain. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2008;105:1672–1677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak I, Engelbrecht G, van Rensburg PJJ, Claassens S. Microbial metabolomics: Essential definitions and the importance of cultivation conditions for utilizing Bacillus species as bionematicides. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2019;127:326–343. doi: 10.1111/jam.14218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im SM, Yu NH, Joen HW, Kim SO, Park HW, Park AR, Kim J-C. Biological control of tomato bacterial wilt by oxydifficidin and difficidin-producing Bacillus methylotrophicus DR-08. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 2020;163:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2019.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeleń H, Błaszczyk L, Chełkowski J, Rogowicz K, Strakowska J. Formation of 6-n-pentyl-2H-pyran-2-one (6-PAP) and other volatiles by different Trichoderma species. Mycological Progress. 2014;13:589–600. doi: 10.1007/s11557-013-0942-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Guo L, Jin B, Zhu S, Mei X, Wu J, Liu T, He X. Inhibitory mechanism of 6-Pentyl-2H-pyran-2-one secreted by Trichoderma atroviride T2 against Cylindrocarpon destructans. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 2020;170:104683. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2020.104683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lex A, Gehlenborg N, Strobelt H, Vuillemot R, Pfister H. UpSet: Visualization of intersecting sets. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. 2014;20:1983–1992. doi: 10.1109/TVCG.2014.2346248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Alfiky A, Wang W, Islam M, Nourollahi K, Liu X, Kang S. Volatile compound-mediated recognition and inhibition between Trichoderma Biocontrol agents and Fusarium oxysporum. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Tang J, Karuppiah V, Li Y, Xu N, Chen J. Co-culture of Trichoderma atroviride SG3403 and Bacillus subtilis 22 improves the production of antifungal secondary metabolites. Biological Control. 2020;140:104122. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.104122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X-R, Miao F-P, Song Y-P, Guo Z-Y, Ji N-Y. Trichocitrin, a new fusicoccane diterpene from the marine brown alga-endophytic fungus Trichoderma citrinoviride cf-27. Natural Product Research. 2016;30:1605–1610. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2015.1126264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lione G, Giordano L, Sillo F, Gonthier P. Testing and modelling the effects of climate on the incidence of the emergent nut rot agent of chestnut Gnomoniopsis castanea. Plant Pathology. 2015;64:852–863. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macías FA, Varela RM, Simonet AM, Cutler HG, Cutler SJ, Eden MA, Hill RA. Bioactive carotanes from Trichoderma virens. Journal of Natural Products. 2000;63:1197–1200. doi: 10.1021/np000121c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minchev Z, Kostenko O, Soler R, Pozo MJ. Microbial consortia for effective biocontrol of root and foliar diseases in tomato. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.756368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira RR, Nesi CN, May De Mio LL. Bacillus spp. and Pseudomonas putida as inhibitors of the Colletotrichum acutatum group and potential to control Glomerella leaf spot. Biological Control. 2014;72:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2014.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munakata Y, Heuson E, Daboudet T, Deracinois B, Duban M, Hehn A, Coutte F, Slezack-Deschaumes S. Screening of antimicrobial activities and lipopeptide production of endophytic bacteria isolated from vetiver roots. Microorganisms. 2022;10:209. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10020209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehela Y, Taha NA, Elzaawely AA, Xuan TD, et al. Benzoic acid and its hydroxylated derivatives suppress early blight of tomato (Alternaria solani) via the induction of salicylic acid biosynthesis and enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant defense machinery. Journal of Fungi. 2021;7:663. doi: 10.3390/jof7080663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo MT, Nguyen MV, Han JW, Park MS, Kim H, Choi GJ. In Vitro and In Vivo antifungal activity of sorbicillinoids produced by Trichoderma longibrachiatum. Journal of Fungi. 2021;7:428. doi: 10.3390/jof7060428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnusamy K, Petchiammal C, Mohankumar R, Hopper W. In vitro antifungal activity of indirubin isolated from a South Indian ethnomedicinal plant Wrightia tinctoria R. Br. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2010;132:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi G, Zhu F, Du P, Yang X, Qiu D, Yu Z, Chen J, Zhao X. Lipopeptide induces apoptosis in fungal cells by a mitochondria-dependent pathway. Peptides. 2010;31:1978–1986. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano A, Vitullo D, Senatore M, Lima G, Lanzotti V. Antifungal cyclic lipopeptides from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Strain BO5A. Journal of Natural Products. 2013;76:2019–2025. doi: 10.1021/np400119n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero D, de Vicente A, Rakotoaly RH, Dufour SE, Veening J-W, Arrebola E, Cazorla FM, Kuipers OP, Paquot M, Pérez-García A. The iturin and fengycin families of lipopeptides are key factors in antagonism of Bacillus subtilis toward Podosphaera fusca. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2007;20:430–440. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-20-4-0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio MB, Hermosa R, Reino JL, Collado IG, Monte E. Thctf1 transcription factor of Trichoderma harzianum is involved in 6-pentyl-2H-pyran-2-one production and antifungal activity. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2009;46:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar A, Hassan MN, Imran M, Iqbal M, Majeed S, Brader G, Sessitsch A, Hafeez FY. Biocontrol activity of surfactin A purified from Bacillus NH-100 and NH-217 against rice bakanae disease. Microbiological Research. 2018;209:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J, Pei Z, Jing H, Wang L, Jiang C, Du X, Jiang C, Lou Z, Wang H. Antifungal activity of myriocin against Fusarium graminearum and its inhibitory effect on deoxynivalenol production in wheat grains. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. 2021;114:101635. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2021.101635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheoran N, Valiya Nadakkakath A, Munjal V, Kundu A, Subaharan K, Venugopal V, Rajamma S, Eapen SJ, Kumar A. Genetic analysis of plant endophytic Pseudomonas putida BP25 and chemo-profiling of its antimicrobial volatile organic compounds. Microbiological Research. 2015;173:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z-Z, Fang S-T, Miao F-P, Yin X-L, Ji N-Y. Trichocarotins A-H and trichocadinin A, nine sesquiterpenes from the marine-alga-epiphytic fungus Trichoderma virens. Bioorganic Chemistry. 2018;81:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth LA, Guest DI. The infection process of chestnut rot, an important disease caused by Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi (Gnomoniaceae, Diaporthales) in Oceania and Europe. Australasian Plant Pathology. 2017;46:397–405. doi: 10.1007/s13313-017-0502-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth LA, Guest DI, Liew ECY. Fungal planet description sheet 108 Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi L.A. Shuttleworth, E.C.Y. Liew & D.I. Guest, sp. Nov. Persoonia. 2012;28:142–143. doi: 10.3767/003158512X652633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth LA, Liew ECY, Guest DI. Survey of the incidence of chestnut rot in south-eastern Australia. Australasian Plant Pathology. 2013;42:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s13313-012-0170-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simon A, Dunlop RW, Ghisalberti EL, Sivasithamparam K. Trichoderma koningii produces a pyrone compound with antibiotic properties. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 1988;20:263–264. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(88)90050-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Gupta R, Tandon S, Pandey R. Anti-biofilm and anti-virulence potential of 3,7-dimethyloct-6-enal derived from Citrus hystrix against bacterial blight of rice caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2018;115:264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singkum P, Muangkaew W, Suwanmanee S, Pumeesat P, Wongsuk T, Luplertlop N. Suppression of the pathogenicity of Candida albicans by the quorum-sensing molecules farnesol and tryptophol. The Journal of General and Applied Microbiology. 2019;65:277–283. doi: 10.2323/jgam.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B, Rong Y-J, Zhao M-X, Chi Z-M. Antifungal activity of the lipopeptides produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens anti-CA against Candida albicans isolated from clinic. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2013;97:7141–7150. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5000-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steyaert J, Hicks E, Kandula J, Kandula D, Alizadeh H, Braithwaite M, Yardley J, Mendoza-Mendoza A, Stewart A. Methods for the evaluation of the bioactivity and biocontrol potential of species of Trichoderma. In: Glare TR, Moran-Diez ME, editors. Microbial-based biopesticides: Methods and protocols. New York: Springer; 2016. pp. 23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed-Ab-Rahman SF, Singh E, Pieterse CMJ, Peer M. Emerging microbial biocontrol strategies for plant pathogens. Plant Science. 2018;267:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théatre A, Cano-Prieto C, Bartolini M, Laurin Y, Deleu M, Niehren J, Fida T, Gerbinet S, Alanjary M, Medema MH, Léonard A, Lins L, Arabolaza A, Gramajo H, Gross H, Jacques P. The surfactin-like lipopeptides from Bacillus spp.: Natural biodiversity and synthetic biology for a broader application range. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.623701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapiello E, Feito I, González AJ. First report of Gnomoniopsis castaneae causing canker on hybrid plants of Castanea sativa × C. crenata in Spain. Plant Disease. 2018;102:1040–1040. doi: 10.1094/pdis-12-17-1874-pdn. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Visentin I, Gentile S, Valentino D, Gonthier P, Tamietti G, Cardinale F. Gnomoniopsis castanea sp. Nov. (Gnomoniaceae, Diaporthales) as the causal agent of nut rot in sweet chestnut. Journal of Plant Pathology. 2012;94:411–419. doi: 10.4454/JPP.FA.2012.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Tian X, Huang C, Li Q, Zhang S. Marinactinones A–C, new γ-pyrones from marine actinomycete Marinactinospora thermotolerans SCSIO 00606. Journal of Antibiotics. 2011;64:189–192. doi: 10.1038/ja.2010.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Wang Z, Liu Z, Wang K, Xu W. Membrane disruption of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum induced by myriocin from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens LZN01. Microbial Biotechnology. 2021;14:517–534. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Chang X, Luo X, Su M, Xu R, Chen J, Ding Y, Shi Y. An integrated approach to characterize intestinal metabolites of four phenylethanoid glycosides and intestinal microbe-mediated antioxidant activity evaluation in vitro using UHPLC-Q-exactive high-resolution mass spectrometry and a 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl-based assay. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welling MT, Deseo MA, Bacic A, Doblin MS. Untargeted metabolomic analyses reveal chemical complexity of dioecious Cannabis Flowers. Australian Journal of Chemistry. 2021;74:463–479. doi: 10.1071/CH21033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. Academic Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Wu H, Chen L, Yu X, Borriss R, Gao X. Difficidin and bacilysin from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 have antibacterial activity against Xanthomonas oryzae rice pathogens. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:12975. doi: 10.1038/srep12975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S-H, Zhao L-X, Chen Y-W, Huang R, Miao C-P, Wang J. Sesquiterpenoids from the endophytic fungus Trichoderma sp. PR-35 of Paeonia delavayi. Chemistry & Biodiversity. 2011;8:1717–1723. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201000236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Ding W, Xu Y, Wu D, Li S, Chen J, Guo B. New insights into the antibacterial activity of hydroxycoumarins against Ralstonia solanacearum. Molecules. 2016;21:468. doi: 10.3390/molecules21040468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Yu S, Yang Y, Zhang J, Zhao D, Pan Y, Fan S, Yang Z, Zhu J. Antifungal effects of volatiles produced by Bacillus subtilis against Alternaria solani in potato. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2020;11:1196–1196. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D-L, Zhang X-F, Huang R-H, Wang D, Wang X-Q, Li Y-Q, Zheng C-J, Zhang P, Zhang C-S. Antifungal nafuredin and epithiodiketopiperazine derivatives from the mangrove-derived fungus Trichoderma harzianum D13. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C-J, Lee S, Lee C-H, Kim W-G. Macrolactins O-R, Glycosylated 24-membered lactones from Bacillus sp. AH159-1. Journal of Natural Products. 2007;70:1632–1635. doi: 10.1021/np0701327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S-Y, Hu Y-J, Meng F-C, Qu S-Y, Wang R, Andersen RJ, Liao Z-H, Chen M. Bacillamidins A–G from a Marine-Derived Bacillus pumilus. Marine Drugs. 2018;16:326. doi: 10.3390/md16090326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zin NM, Al-shaibani MM, Jalil J, Sukri A, Al-Maleki AR, Sidik NM. Profiling of gene expression in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in response to cyclo-(l-Val-l-Pro) and chloramphenicol isolated from Streptomyces sp., SUK 25 reveals gene downregulation in multiple biological targets. Archives of Microbiology. 2020;202:2083–2092. doi: 10.1007/s00203-020-01896-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to commercial confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.