Abstract

The complete primary structure of the str operon of Bacillus stearothermophilus was determined. It was established that the operon is a five-gene transcriptional unit: 5′-ybxF (unknown function; homology to eukaryotic ribosomal protein L30)-rpsL (S12)-rpsG (S7)-fus (elongation factor G [EF-G])-tuf (elongation factor Tu [EF-Tu])-3′. The main operon promoter (strp) was mapped upstream of ybxF, and its strength was compared with the strength of the tuf-specific promoter (tufp) located in the fus-tuf intergenic region. The strength of the tufp region to initiate transcription is about 20-fold higher than that of the strp region, as determined in chloramphenicol acetyltransferase assays. Deletion mapping experiments revealed that the different strengths of the promoters are the consequence of a combined effect of oppositely acting cis elements, identified upstream of strp (an inhibitory region) and tufp (a stimulatory A/T-rich block). Our results suggest that the oppositely adjusted core promoters significantly contribute to the differential expression of the str operon genes, as monitored by the expression of EF-Tu and EF-G.

The streptomycin operon (str) belongs among the most-conserved operons in prokaryotic evolution (20, 27). The str operon of Escherichia coli, from which most of our knowledge about this operon is derived, is composed of four genes: rpsL (coding for ribosomal protein S12), rpsG (ribosomal protein S7), fus (elongation factor G [EF-G]), and tufA (elongation factor Tu [EF-Tu]). It is transcribed from its main promoter situated upstream of the rpsL gene (43). Besides the main promoter, two additional promoters, located within the fus gene, direct the transcription of the tufA gene (1, 57, 59). Zengel and Lindahl estimated the combined activity of these additional promoters to be about 30% of the activity of the main promoter (58, 59). These promoters, as well as the second copy of the tuf gene (tufB) present in the E. coli chromosome (21), contribute to the increased expression of EF-Tu relative to the expression of other genes of the str operon.

Approximately 50 str operons have already been sequenced. However, only a few of them were also characterized functionally by their transcriptional products and transcriptional starts. In our previous work, we cloned and characterized the tuf gene of Bacillus stearothermophilus. A tuf-specific promoter (tufp) was detected in the fus-tuf intergenic region. Based on Northern blot experiments, the ratio between the tuf-specific and the polycistronic transcript was estimated to be at least 10:1 (28).

In the present work, we extended our studies to the rest of the str operon of B. stearothermophilus with a special focus on the characterization of the promoters of this operon. As a prerequisite, the complete primary structure of the str operon of B. stearothermophilus was determined, and the main operon promoter (strp) was mapped. By using the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) assay technique, the strength of the strp promoter was compared with the strength of the previously identified tufp promoter. The proposed stimulatory function of an A/T-rich block preceding tufp was experimentally confirmed and an inhibitory cis element acting on strp was discovered. Based on the comparison of EF-G and EF-Tu expression, we suggest that the promoter for the tuf gene plus the cis elements acting on tufp and on strp significantly contribute to the differential expression of the str operon genes in gram-positive B. stearothermophilus. An “additional” gene, one preceding the rpsL gene and designated ybxF, was found to belong to the str operon in B. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis. The implications derived from the presence of the ybxF gene in this highly conserved operon are outlined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

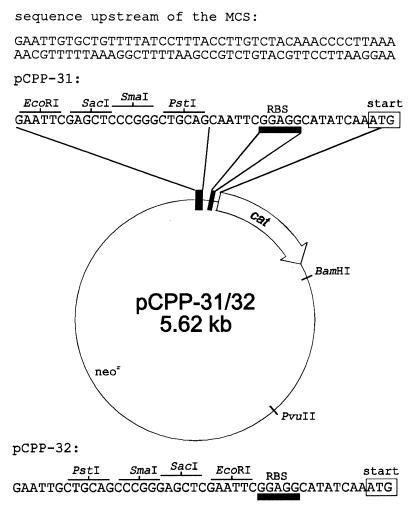

B. stearothermophilus (CCM 2184) and B. subtilis 168 were used as the sources of DNA and RNA, and B. subtilis MI 115 (leu rm− mm− recA4) as a host in CAT assay experiments. E. coli DH5α served as a host in cloning and subcloning experiments. Plasmids pUC18 and pUC19 (54) were used in cloning and subcloning experiments. Promoter probe E. coli-B. subtilis shuttle vector pCPP-3, obtained upon request from Band et al. (3), was modified by insertion of a multiple cloning site (MCS). The resulting constructs were named pCPP-31 and pCPP-32, depending on the orientation of the MCS (see Fig. 6). Plasmids are available upon request. Shuttle vector pCPP-31 was used as a promoter probe vector in CAT assay experiments. Plasmids pCPP-31.X1-7 and pCPP-31.Y1-3, derivatives of pCPP-31, were constructed to evaluate the activity of strp and tufp (see Fig. 8). pCPP-31 was digested with EcoRI and PstI, and appropriate, PCR-amplified, inserts were ligated into it. Precise endpoints of cloned fragments are indicated in Fig. 2 and 7. Primer sequences used to amplify the promoter regions that were cloned into these plasmids are available on request. The plasmid copy number of the constructs (in B. subtilis) was assessed regularly, according to the method of Labes et al. (29). The plasmid copy number was approximately 20, and it varied <10% among the individual constructs. Sequence inspection of the region upstream of the MCS did not reveal any known motif (secondary structures; presence of core promoter-like sequences in both the plasmid and the inserted DNA that could upon ligation create an artificial promoter; and UP element-like sequence adjacent to the MCS) that could, in the context of the inserted DNA, influence the results of the CAT assays.

FIG. 6.

Map of pCPP-31 and pCPP-32. The ribosome binding site (RBS) is underlined with a rectangle shaded in gray. The cat gene accession number (GenBank) is K00544 (18). The MCS sequences and their flanking regions are deposited in the EMBL database under accession numbers AJ133759 (pCPP-31) and AJ133760 (pCPP-32). For details, see Materials and Methods.

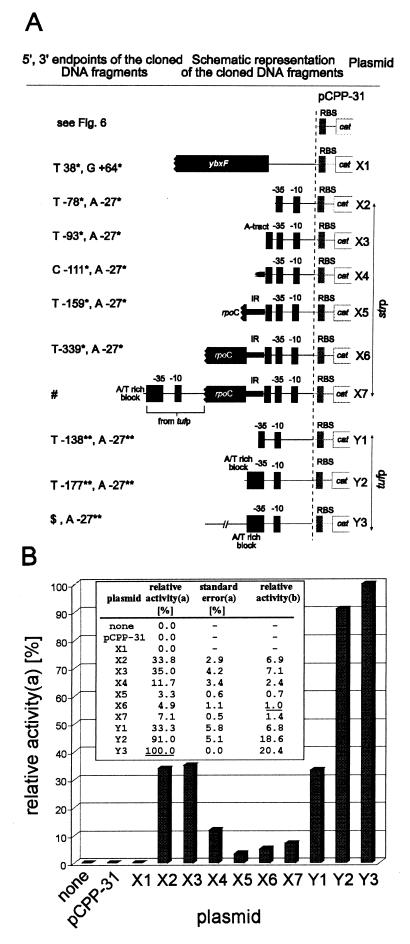

FIG. 8.

Schematic structure of pCPP-31 derivatives (A) and their transcriptional activity in CAT assays (B). (A) All DNA inserts were cloned into the EcoRI-PstI site of the polylinker upstream of the cat gene and its ribosome binding site (RBS) of pCPP-31. The picture is not drawn to scale, and the pCPP-31 part of the plasmid name is omitted. The ′X2-′X7 plasmids carry the strp core promoter sequence extended with its upstream DNA regions of increasing size as indicated. The ′Y1-′Y3 plasmids carry the tufp core promoter extended in the same way. ∗ and ∗∗, see Fig. 2 and 7. #, the DNA insert upstream of the strp core promoter is the same as in X6 extended for the tuf promoter region specified in ′Y2; $, the 5′ end of the insert is 499 bp upstream of the tuf gene translational start (for nucleotide sequence see EMBL database entry AJ249559). (B) CAT assay results. The background value of the negative control (plasmidless B. subtilis) was subtracted. The results are averages of at least two experiments done in duplicates, normalized to the same amounts of protein. a, the activity of the most active promoter region (pCPP-31.Y3) was taken as 100% (underlined); b, relative strengths of promoter regions compared to the activity of the strp promoter (pCPP-31.X6). Its activity was taken as 1 (underlined).

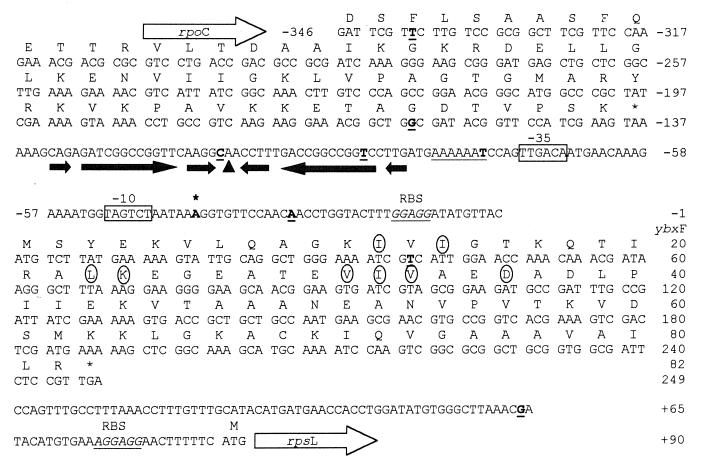

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of the region upstream of the rpsL gene, and deduced amino acid sequences of the ybxF gene and the 3′ end of the rpoC gene of B. stearothermophilus. The Shine-Dalgarno sequences are in underlined italics. The −35 and −10 regions of the strp are boxed. The +1 nucleotide of the str operon transcript is in boldface, indicated by an asterisk. The A-tract upstream of strp is underlined. The transcription termination signal of the rpoC gene is underlined with shaded arrows. The top of the palindrome is indicated by a triangle. The stability of this structure was calculated to be −49.3 kJ mol−1 at 65°C (RNAdraw V1.0 [34]). The IR extends from the 3′ end of the rpoC gene (from −159) to the 5′ end of the A tract. The circled amino acids denote the RNA-binding motif (26). The underlined boldface letters denote the 5′ and 3′ ends of the cloned DNA fragments (see also Fig. 8).

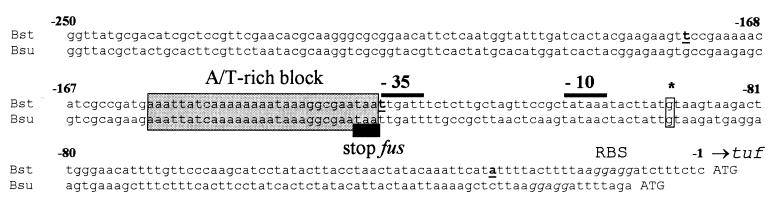

FIG. 7.

Sequence alignment of B. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis tuf promoter regions. The 3′ ends of the sequences end with start codons of tuf genes. The black rectangle below the sequence denotes the stop codon of the fus gene. The −35 and −10 hexamers are indicated by thick lines above the sequence. The asterisk denotes the transcription-initiation site as determined previously (28). The ribosome binding site (RBS) is italicized. The shaded box contains the A/T-rich block. The thick underlined letters mark the endpoints of cloned DNA fragments as described in Fig. 8.

Media and transformation.

B. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis 168 were grown as described by Krásný et al. (28). E. coli competent cells were prepared, and consecutive transformations were carried out as described by Hanahan (17). Transformants were selected by plating onto RMK (composition per liter: Bacto-tryptone, 20 g; Bacto-yeast extract, 5 g; 1 M KCl, 10 ml; 20% glucose, 16.7 ml; 80% [wt/vol] MgSO4 · 7H2O, 10 ml) agar plates supplemented either with ampicillin (80 μg/ml) or neomycin (20 μg/ml). B. subtilis MI 115 cells were made competent, and transformation experiments were carried out according to the method of Dubnau and Davidoff-Abelson (12). Transformants were selected by plating them onto agar plates prepared from the enriched Spizizen medium (composition per liter: (NH4)2SO4, 2 g; KH2PO4, 6 g; sodium citrate · 2H2O, 1 g; MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.2 g; glucose, 0.5%; K2HPO4 · 3H2O, 18.3 g; tryptone, 20 g; yeast extract, 5 g) supplemented with neomycin (20 μg/ml).

Enzymes and chemicals.

Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, shrimp alkaline phosphatase, DNA Megaprime Labeling Kit, T7 Sequenase DNA Sequencing Kit, QUAN-T-CAT kit, [α-32P]dCTP, and [γ-32P]ATP were purchased from Amersham (Germany); RNase A, T4 polynucleotide kinase, RNasin, and avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase were purchased from Promega. The Expand High-Fidelity PCR System was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim. Deep Vent DNA polymerase was from New England BioLabs. All enzymes and kits were used according to the manufacturers' recommendations. Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from GeneriBiotech (Czech Republic).

Nucleic acids preparation and manipulation.

B. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis genomic DNAs were extracted and purified as described earlier (33) with some modifications. Plasmid DNAs were prepared with the Wizard System purchased from Promega. Gel extractions were carried out with the QiaexII kit from Qiagen. Restriction mapping, Southern hybridization analysis, agarose gel electrophoresis, and subcloning of DNA fragments were performed by standard procedures (47). B. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis RNA was prepared from cells harvested in the mid-log-growth phase with the RNAeasy kit purchased from Qiagen. Formaldehyde agarose electrophoresis, blotting, and Northern blot hybridization were carried out as described previously (47). RNA marker from Gibco-BRL was used as a molecular weight marker in Northern blot hybridization experiments.

Cloning of the fus gene.

A pair of primers was designed to amplify the region containing the entire fus gene: PIII from residues 1053 to 1073 (25) (5′-GCGTGCGCGATCATTTCTCTG-3′) and PIV from residues 16 to 36 (28) (5′-GAGCGCACGAAACCGCACGTC-3′). The Expand High-Fidelity PCR System was used to ensure the fidelity of the PCR. The 2.3-kb product was cloned into pUC18. Three recombinant clones were selected for further analysis.

Cloning of the region upstream of rpsL.

Ligation-mediated PCR (LM-PCR) (44) was used to clone the region upstream of the rpsL gene with the following modifications. Primers PV (5′-TCTCCGTTGACCAGTTTGCC-3′) and PVI (5′-GTTTTTTCGGCGTCATG-3′) were used to amplify a part of the rpsL gene, which was used as a probe in Southern hybridization experiments. A BclI digest of chromosomal DNA was established to contain a 1.4-kb fragment containing at its 3′ end the 5′-end region of the rpsL gene. Primers PVII (5′-TAGCTTATTCCTCAAGGCACGACG-3′) and PVIII (5′-GATCCGTCGTGC-3′) were assembled into a linker. The linker was ligated to the BclI digest of chromosomal DNA. Subsequently, the ligation mixture was digested with BclI. Primers PVII and PIX (5′-CAAACTGGTCAACGGAGAATCGCC-3′; from positions −105 to −83 [25]) from the region adjacent to the rpsL gene were used to amplify the 1.4-kb fragment. The Expand High-Fidelity PCR System was used to ensure the fidelity of the PCR. The 1.4-kb fragment was cloned into pUC18, and three clones were selected for further analysis.

DNA sequence determination.

DNA sequencing was done in both directions with either T7 Sequenase DNA Sequencing Kit or fluorescent AutoRead Sequencing Kit purchased from Pharmacia. At least three clones from independent PCR reactions of each DNA fragment were sequenced. The fus gene sequence was obtained by sequencing of subcloned DNA fragments. The 1.4-kb fragment from the region upstream of the rpsL gene was first sequenced from both sides to verify its identity. It contained the 3′ end of the rpoC gene at its 5′ end, and it ended upstream of the rpsL gene. The 3′-end half of the fragment reaching far into the rpoC gene was then separately cloned and sequenced.

PCR: Northern blot hybridization probes.

The following pairs of primers were used to amplify the respective regions of the str operon: for B. stearothermophilus, fus probe, PAN (5′-GCACAATGGAAAGGCCACCGC-3′) and VOK (5′-GCCCAGCCGGAGAAGACCGGG-3′), and ybxF probe (containing the entire ybxF gene), B. subtilis, fus probe, nucleotides (nt) 3772 to 3791 (forward primer) and nt 4019 to 4038 (reverse primer), and ybxF probe, nt 2429 to 2428 (forward primer) and nt 2661 to 2680 (reverse primer) (numbering is according to Yasumoto and coworkers [55]).

Primer extension experiments.

The primer extension experiments were carried out as described previously (28) with the following modifications. A total of 25 μg of B. stearothermophilus total RNA was hybridized to the primer SMICH (5′-CGATCACTTCCGTTGCTTCC-3′), complementary to the 5′ end of the ybxF gene. The hybridization temperature was set at 30°C.

2D electrophoresis.

B. stearothermophilus EF-Tu and EF-G were isolated essentially as described earlier (23, 28). B. stearothermophilus S30 fractions from the mid-exponential and stationary (overnight culture) phases were prepared from bacterial cells resuspended in the following buffer: 20 mM cacodylic acid sodium salt (pH 6.8), 60 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 15% glycerol. Estimation of the protein concentration was performed by the method of Bradford (6). A total of 0.5 μg of the S30 fraction was resolved on Mini 2D electrophoresis gels (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The density of the second-dimension gel was 12%. EF-Tu and EF-G were analyzed in a parallel experiment to allow the identification of EF-Tu and EF-G spots in the B. stearothermophilus proteome map. Proteins were visualized either by staining with Coomassie blue R-250 or by silver staining (4). The relative staining efficiencies of identical amounts of isolated EF-Tu and EF-G were about equal. The relative amounts of EF-Tu and EF-G in the two-dimensional (2D) map were determined by densitometric measurements, normalized to the molecular weights of these proteins.

CAT assay experiments.

B. subtilis MI 115 transformed with respective plasmids (see Fig. 8) was grown in enriched Spizizen medium at 37°C. The cells were harvested at an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.6. Then, 1 ml of the cell suspension was centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of ice-cold 0.1 M Tris-Cl (pH 7.8). Next, 100 μl of this suspension was transferred into a fresh tube, and the cells were disrupted by sonication at 0°C (twice, for 10 s each time; amplitude, 0.6 μm; Soniprep 150). The sonicated cells were pelleted, and the supernatant (S30) was used in subsequent steps. Then, 0.04 μl of the supernatant, diluted in 40 μl of 0.1 M Tris-Cl (pH 7.8), was used to conduct CAT assays with the QUAN-T-CAT kit (Amersham). The CAT assays were conducted according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Estimation of protein concentration was performed by the method of Bradford (6).

FCA.

Factorial correspondence analysis (FCA) was performed with the assistance of the database Indigo, accessible through the World-Wide Web at http: //indigo.genetique.uvsq.fr).

Accession numbers.

The fus gene sequence and the sequence of the region upstream of the rpsL gene have been submitted to the EMBL database under accession numbers AJ249559 and AJ249558, respectively. The MCSs of pCPP-31 and pCPP-32 have been submitted to the EMBL database under accession numbers AJ133759 and AJ133760, respectively.

RESULTS

Structure and genomic organization of the str operon.

Sequences of two fragments of the str operon of B. stearothermophilus have already been reported: (i) the rpsL (S12) and rpsG (S7) genes (25) and (ii) the tuf gene (28). To determine the primary structure of the remaining parts of the str operon, the fus gene located between the rpsG and tuf genes was cloned and sequenced (Fig. 1). The fus gene consists of 2,079 nt. It codes for EF-G, a protein of 692 amino acid (aa) residues with a calculated 77,038-Da molecular mass (excluding possible posttranslational modification) and a pI of 5.10. EF-G is a monomeric GTP-binding protein involved in translocation of peptidyl-tRNA from the A to the P site on the ribosome. Starting from the aa 46 (Gly), the amino acid sequence of the N terminus of EF-G deduced here differs from that proposed by Kimura (25). This difference is due to a missing G nucleotide at this position in his published DNA sequence. The nucleotide identity of the B. stearothermophilus fus gene to the fus gene of B. subtilis is 72%.

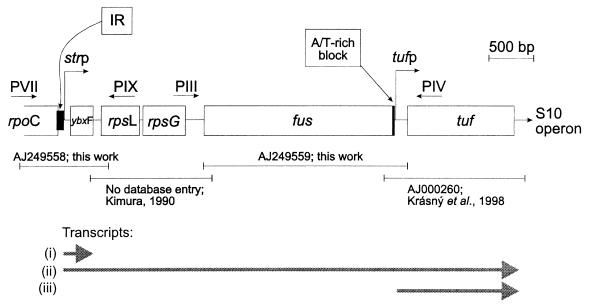

FIG. 1.

str operon of B. stearothermophilus. Horizontal arrows represent PCR primers used in cloning experiments (for details, see Materials and Methods). The EMBL accession numbers assigned to nucleotide sequences are indicated below the scheme in combination with the sequences of Kimura (25) and Krásný et al. (28). The positions of the functional promoters strp and tufp and their transcriptional products are shown. Transcripts: i, ybxF transcript terminated in the ybxF-rpsL intergenic region; ii, full-length transcript of the str operon; and iii, tuf gene transcript transcribed from the tuf-specific promoter (see reference 28). The A/T-rich block and the IR are indicated.

Subsequently, the LM-PCR cloning strategy (44) was used to clone the unknown region upstream of the rpsL gene (Fig. 2; see also Materials and Methods). Directly upstream of the rpsL gene is an open reading frame (ORF) of 249 nt separated from the 5′ end of the rpsL gene by 90 nt. It shares 61% nucleotide identity with an analogous ORF of B. subtilis. It was therefore assigned to ybxF. The ybxF gene codes for a protein of 82-aa residues with a calculated molecular mass of 8,591 Da and a pI of 8.91. The region upstream of the ybxF gene is occupied by the 3′ end of another ORF. Since it is 72% identical to the rpoC gene of B. subtilis that codes for the β′ subunit of RNA polymerase (55), it was assigned to rpoC. The intergenic region between rpoC and ybxF is 136 nt long and contains a palindromic structure that most likely serves as a transcription termination signal for the rpoC gene (Fig. 2). At the 3′ end, the str operon is followed by the S10 operon (28).

The str operon is a five-gene transcriptional unit.

Based on the cloning and sequencing experiments, a question emerged: does the ybxF gene of B. stearothermophilus belong to the str operon? Even in B. subtilis the answer to this question was unknown. So far, it has been assumed that the str operon of B. subtilis is a four-gene transcriptional unit (20). To address this question experimentally, Northern blot hybridization experiments were carried out. In Fig. 3A, lane 1, total RNA of B. stearothermophilus was hybridized with a DNA fragment from the fus gene. A single band corresponding in size to 4.9 kb was detected. In parallel, the ybxF was used as a probe. A signal appeared in precisely the same position as in the experiment with the fus gene fragment as a probe (Fig. 3A, lane 2). This experiment was repeated with B. subtilis RNA and corresponding probes. The result was identical: the ybxF probe hybridized in the same position as the fus probe (Fig. 3B). The conclusion drawn from these experiments is that the ybxF gene is a part of the str operon in both B. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis.

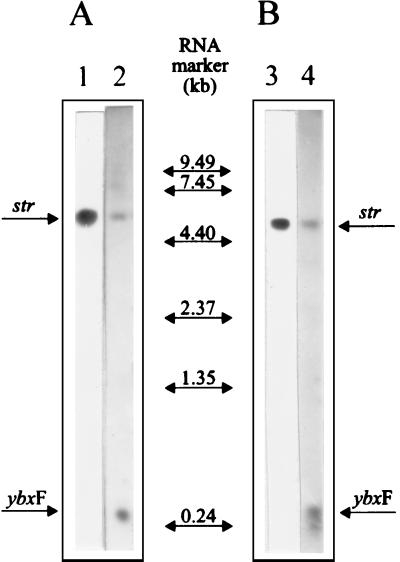

FIG. 3.

Northern blot hybridization analysis of B. stearothermophilus (A) and B. subtilis (B) RNA. Each lane contains 5 μg of total RNA. Hybridization was carried out with fus probes (lanes 1 and 3) or ybxF probes (lanes 2 and 4). The polycistronic (str) and ybxF (ybxF) transcripts are indicated. The RNA molecular weight marker was from Gibco-BRL.

Besides the polycistronic transcripts of 4.9 kb (B. stearothermophilus) and 4.7 kb (B. subtilis), the ybxF probes of both bacteria hybridized to a small transcript of approximately 0.3 kb (Fig. 3, lanes 2 and 4). Its length suggests that it comprises the entire ybxF gene and terminates in the ybxF-rpsL intergenic region. This transcript is most likely not a processing product because both the ybxF and fus probes detected no other transcripts indicative of processing of the str mRNA.

Mapping of the str promoter.

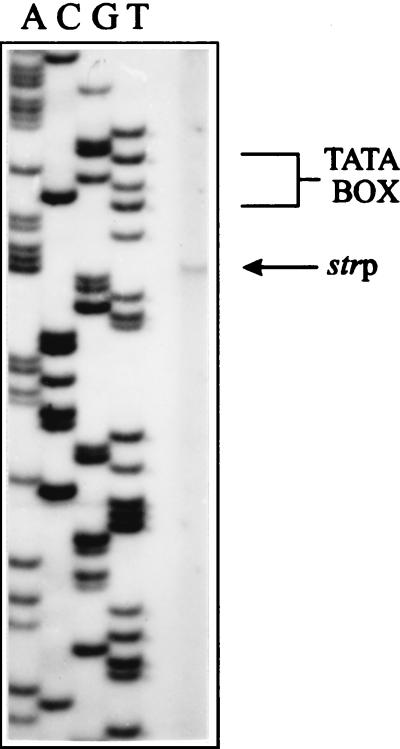

S1 nuclease experiments mapped the 5′ end of the str mRNA transcript upstream of the ybxF gene (data not shown). The +1 nucleotide, determined by primer extension experiments (Fig. 4), was mapped 6 bp downstream of the TAGTCT sequence that has 5 nt identical to the B. stearothermophilus −10 promoter consensus sequence (TATTA/CT [52]; Fig. 2). Further upstream, separated by a spacer of 17 nt, is a hexanucleotide TTGACA sequence that in 5 out of 6 nt matches the B. stearothermophilus −35 promoter consensus sequence (TTGACT/C). Inspection of the corresponding region of B. subtilis revealed a similar promoter-like structure. The −10 region (GATAAT, consensus TATAAT) and the −35 region (TTGACA, same as consensus) are separated by 16 nt. The promoter sequences of both organisms comply with all requirements on Bacillus promoter sequences necessary for efficient recognition by the ςA subunit of the RNA polymerase involved in transcription of housekeeping genes (16).

FIG. 4.

Primer extension analysis of the polycistronic transcript of B. stearothermophilus str operon. The 5′ end of the transcript, initiated at strp, is indicated by an arrow. Lanes A, C, G, and T contain sequencing ladder of the respective genomic region generated with the same primer. The −10 region is indicated by a bracket.

Intracellular level of EF-G and EF-Tu and quantitative evaluation of the tufp and strp promoters.

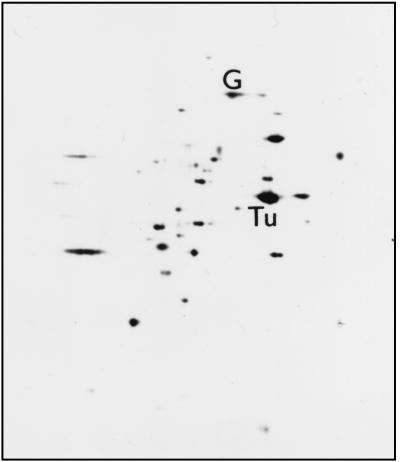

Prior to quantitative evaluation of strp and tufp, the relative intracellular concentrations of EF-G and EF-Tu were determined. Direct densitometric measurements within the proteome, the 2D profile map of B. stearothermophilus proteins, indicated that the ratio of molar concentrations of EF-Tu and EF-G is approximately 9:1 (Fig. 5). The experiments were performed with cells from the exponential and stationary phases (see Materials and Methods) with identical results. This experiment was also carried out with B. subtilis. The EF-Tu/EF-G ratio was almost the same as in B. stearothermophilus: 10:1 (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

2D electrophoresis of B. stearothermophilus S30 fraction from the mid-exponential phase. The first dimension was run from left to right, with the more acidic proteins migrating further to the right. The second dimension was run from the top down. The positions of EF-Tu and EF-G are indicated.

Since both our previous experiments (28) and the experiments presented here suggested that transcription of the str operon of B. stearothermophilus is controlled from two promoters, various portions of the putative promoter regions were cloned into a newly constructed promoter probe E. coli-B. subtilis shuttle vector pCPP-31 (Fig. 6) to assess promoter strengths of the cloned DNA fragments. The cloning experiments were conducted in gram-negative E. coli, and the constructs were used to transform gram-positive B. subtilis to provide for a homologous environment in subsequent CAT assay experiments. The nucleotide sequences of the cloned DNA fragments are shown in Fig. 2 (the strp region) and 7 (the tufp region).

Figure 8 schematically represents all of the recombinant constructs used in this study and summarizes the results of the CAT assay experiments obtained for bacteria from the mid-exponential phase. (i) The region upstream of the rpsL gene, where the main promoter of str operons is regularly found, e.g., in E. coli (43), did not possess any promoter activity (pCPP-31.X1). Its effect on the expression of CAT remained at a level comparable to the background expression from the insertless pCPP-31. (ii) In contrast, insertion of strp and tufp core promoters (fragments containing −35 and −10 hexamers) upstream of the otherwise promoterless cat gene of pCPP-31 induced a strong expression of CAT (constructs pCPP-31.X2 and pCPP-31.Y1, respectively). Both core promoters were equally active in vivo. (iii) The previously identified A/T-rich block preceding the −35 region of tufp (Fig. 7) (28) stimulated transcription from the tufp core promoter (−10 and −35) by a factor of about three (pCPP-31.Y2). (iv) The DNA sequence upstream of the A/T-rich block was not found to significantly influence the transcriptional activity of tufp. The DNA fragment containing tufp and the A/T-rich block, extended by about 300 bp further upstream of the A/T-rich block (pCPP-31.Y3), was approximately as active in CAT assays as the nonextended fragment (pCPP-31.Y2). The ∼10% difference in activities between pCPP-31.Y2 and pCPP-31.Y3 may rather be attributed to the overall nucleotide composition of the region upstream of the A/T-rich block than to a particular structural element. (v) In contrast to tufp, the activity of the strp promoter was not influenced by an A-tract (construct pCPP-31.X3) situated directly upstream of the −35 hexamer, i.e., in a position analogous to the A/T-rich block of tufp (Fig. 2). (vi) However, further upstream extension of the strp region for approximately 70 bp (pCPP-31.X5) resulted in a sharp, ∼10-fold drop in the promoter activity. This unexpected finding indicated the presence of an inhibitory element in the intergenic region partially suppressing the core promoter activity. (vii) Further upstream extension of the promoter region for 180 bp (pCPP-31.X6) slightly relieved the suppression brought about by the 70-bp inhibitory region (IR). Nevertheless, ∼7-fold inhibition of the core promoter activity was retained. (viii) The IR contains the termination palindrome for the transcription of the rpoC gene. To test whether the palindromic structure could be responsible for the inhibition by extruding into a cruciform, pCPP-31.X4 was constructed. The insert comprised only the 3′-end half of the palindrome. Despite this substantial modification, which abolishes the formation of any cruciform based on the palindrome, the inhibitory activity of the insert was retained, although 2.4-fold decreased with respect to pCPP-31.X6, indicating that the palindrome is not essential for the inhibition. (ix) Since the IR is in vivo most likely transcribed, the pCPP-31.X7 was constructed to check whether the simultaneous transcription of the rpoC gene influences transcription initiation from strp. The simultaneous transcription of the 3′-terminal part of the rpoC gene fragment, controlled by the inserted tufp region including the A/T-rich block (pCPP-31.X7), was not found to significantly modify the promoter suppression imposed by the IR.

The deletion mapping experiments provided evidence that the two cis-acting regulatory elements, one enhancing (the A/T-rich block) and the other silencing (the rpoC-ybxF intergenic region preceding the strp core promoter), set the in vivo ratio between strp and tufp transcriptional strength to approximately 1:20.

Codon usage.

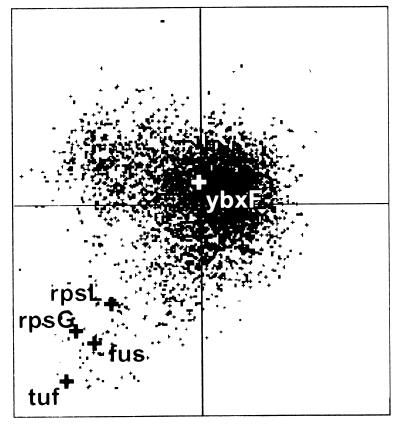

Our experiments have established a direct positional and transcriptional link between the rpsL, rpsG, fus, and tuf genes and the ybxF gene within the B. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis str operons. Since most proteins of the translational apparatus have a highly biased codon usage in a particular organism (35), FCA was carried out to address the functional relatedness of ybxF with other genes of the str operon. This method relates genes according to their usage of synonymous codons (reference 40 and references therein). Genes highly expressed under specific physiological conditions should display a similar codon usage bias (36). Figure 9 shows that the rpsL, rpsG, fus, and tuf genes of B. subtilis group together, while the ybxF gene is positioned at a distance from this cluster (for further interpretation, see Discussion).

FIG. 9.

Factorial correspondence analysis of codon usage in the B. subtilis ORFs. The large black crosses represent rpsL, rpsG, fus, and tuf. The position of ybxF is marked by the large white cross (for details, see the text).

DISCUSSION

Transcription of the str operon.

Our experiments have established that the str operons of both B. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis are transcriptional units composed of five genes: 5′-ybxF-rpsL (S12)-rpsG (S7)-fus (EF-G)-tuf (EF-Tu)-3′ (Fig. 1). Besides the highly conserved rpsL, rpsG, fus, and tuf genes, the ybxF gene was found to extend the 5′ end of the operon in both organisms. This is a rare observation because until now all genes found to precede the rpsL gene of the str operon, with the exception of the archaebacterium Methanococcus vannielii (30), have been considered to be genes adjacent to the str operon but never as members of the operon (5, 20).

The measurements of the strength of strp and tufp of B. stearothermophilus revealed that the transcription proceeds about 20 times more efficiently from tufp than from strp. The experiments demonstrated that the observed concentration difference between the polycistronic and the tuf-specific transcript is based on two differently active promoters. The difference in transcription from these two promoters is brought about by a combined effect of two cis elements acting on equally active core promoters (Fig. 1 and 8). The main operon core promoter is downregulated (by the IR), while the tuf-specific core promoter is upregulated (by the A/T-rich block).

Sequence inspection of the IR revealed the presence of a palindrome representing the transcription termination signal for the rpoC gene. If the palindrome created an unusual DNA structure, such as a cruciform, it might interfere with formation of the transcription-initiation complex (37, 49). We tested this alternative on a plasmid containing only the 3′-end half of the palindrome (pCPP-31.X4). This modification excluded the formation of any palindrome-based cruciform. However, the inhibitory effect of the region was not abolished, only decreased. The promoter activity of the construct was still 2.9-fold lower than that of the strp core promoter. Also, in vitro S1 nuclease mapping experiments (41) failed to detect any cruciform in pCPP-31.X6 (data not shown). These results suggested an additive, stepwise-like inhibitory effect within the IR sequence. We further tested the strp region for the presence of DNA curvature, which could be responsible for the suppression (10, 42, 45). DNA bending manifests itself by anomalous electrophoretic mobility in polyacrylamide gels. DNA fragments containing bends migrate more slowly than unbent DNA fragments (11). The K value (the ratio of the apparent length of a fragment to its actual length) of the fragment cloned into pCPP-31.X5 was 1.2, strongly suggesting the presence of a DNA bend (data not shown). Further experiments are required to characterize the detected DNA bend, its position and distribution. Furthermore, the suppression can be aided by protein factors, and we intend to study the topology of the IR to determine its mode of function.

The A/T-rich block preceding the −35 region was demonstrated to stimulate the tufp activity by a factor of three. Generally, A/T-rich blocks, also referred to as upstream (UP) elements, are sequence elements that increase promoter strength (39, 53). The UP elements contribute to promoter recognition via their interaction with the C-terminal domain of the α subunit (αCTD) of RNA polymerase (9, 22, 46). Therefore, a contact between the A/T-rich block and the αCTD RNAP may be the mechanism that contributes to the efficient transcription of the tuf gene in B. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis.

It should be emphasized that the experimental design of the CAT assay experiments described here does not rule out the possibility that some unknown regulatory factor may be neutralized by the elevated gene dosage (the plasmid copy number is approximately 20; see Materials and Methods). However, the ratios of EF-Tu to EF-G (this work) and str mRNA to tuf mRNA (28) are based on measurements of the products of the chromosome-borne genes. The relative strength of the two tested promoters correlates with the relative concentrations of these products. Therefore, we feel it is reasonable to suggest that the results of our experiments reflect the promoter activities in the chromosome.

Our findings are consistent with the idea that the differential transcription of the fus and tuf genes significantly contributes to the observed 1:9 EF-G/EF-Tu ratio in B. stearothermophilus, provided the two classes of the tuf mRNAs are not translated with significantly different efficiencies. In E. coli, neither the two additional, weak tufA-specific promoters nor the second copy of the tuf gene, which is transcribed from a promoter approximately as active as the additional tufA promoters (1), provide a sufficient excess of the tuf-containing mRNAs over the fus-containing mRNAs that would explain the 1:10 EF-G/EF-Tu ratio in this organism (56). Thus, while in E. coli other mechanisms, such as translational efficiency or mRNA or protein stability, must adjust the final EF-G/EF-Tu ratio by increasing the concentration difference between these two proteins, in B. stearothermophilus the difference is already created at the transcriptional level. In fact, the difference is more pronounced at the transcriptional than at the translational level, most likely also further accentuated by the partially readthrough termination downstream of the ybxF gene, and additional mechanisms must be required to adjust the final EF-G/EF-Tu ratio by reducing the concentration difference created at the transcriptional level. Thus, E. coli and B. stearothermophilus represent two solutions of the same problem.

According to DNA sequence data, it is likely that elements similar to those described here are also active in the B. subtilis (55) and B. halodurans str operon (50). Therefore, it is tempting to hypothesize that mechanisms of control of the EF-G/EF-Tu ratio have common features among bacilli. The work on streptomycetes conducted by Tieleman and coworkers (51) implies that the presence of a tuf-specific promoter may also be characteristic for other gram-positive bacteria. The relative activities of tufp and strp in streptomycetes, however, were not assessed.

Implications derived from the presence of the ybxF gene in the str operon.

The ybxF gene codes for a protein of unknown function, homologous to eukaryotic ribosomal protein L30. The ybxF gene product shares 41% amino acid identity and 82% amino acid similarity with a 30-aa conserved region of human-rat liver L30 (38). L30 proteins bind to 28S rRNA (31, 32). A conserved, tentative RNA binding motif (Fig. 2) was identified in these proteins by Koonin and coworkers (26). The deduced amino acid sequences of the ybxF genes of both B. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis contain the same RNA binding motif, and their cotranscription with ribosomal proteins and basic pI suggest that they are ribosomal proteins. However, none of the known primary structures of B. stearothermophilus ribosomal proteins (2, 19) matches the deduced aa sequence of the ybxF gene. To resolve whether the product of the ybxF gene is a part of the ribosome or possesses a different function, or both, will be the subject of further studies.

The factorial correspondence analysis of B. subtilis ybxF gene revealed its codon usage as being significantly different from the remaining four genes of the operon. This result suggests that the rpsL, rpsG, fus, and tuf genes have evolved under similar selective constraints, whereas the ybxF gene was linked to the rest of the str operon at a point in evolution when the aforementioned four genes had already coexisted and participated in translation. This result supports the view that the ybxF translation product has a nonribosomal destination.

The ybxF gene has a paralogous counterpart on the B. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis chromosomes, the ymxC gene. The ymxC gene is organized in the nusA-infB region and codes for a protein of unknown function (7, 48). In most of the known archaebacterial genomes, the nusA gene and the ybxF orthologue are organized upstream of the rpsL gene (see, for example, references 8, 24, and 30). FCA of B. subtilis genes positions nusA and ybxF close to each other (data not shown). Thus, the ybxF gene in bacilli may have originated by duplication of the ymxC gene or vice versa. It is also interesting to note that the gene adjacent to ymxC, infB, codes for a GTP-binding protein, translation initiation factor IF2, that is partially homologous to EF-Tu and EF-G.

The presence of the ybxF gene in the str operon bears further phylogenetic implications. A database search revealed that also some other gram-positive bacteria have the ybxF gene organized in the same genomic context (e.g., Clostridium acetobutylicum and Staphylococcus aureus), but nothing is known about their transcriptional organization. In contrast, gram-negative bacteria do not have a homologue of the ybxF gene. Thus, our results support the hypothesis that archaebacteria are more closely related to gram-positive bacteria, especially to the low-G+C gram-positive bacteria (e.g., bacilli), than to gram-negative bacteria (13, 14, 15).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Draper for comments on the structure of the fus gene of B. stearothermophilus and L. Výborná and K. Zemanová for skillful technical assistance.

This work was supported by grant 75195-540305 from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to J.J.) and by grant 204/98/0863 from the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (to J.J.).

REFERENCES

- 1.An G, Lee J S, Friesen J D. Evidence for an internal promoter preceding tufA in the str operon of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:548–553. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.2.548-553.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arndt E, Scholzen T, Krömer W, Hatakeyama T, Kimura M. Primary structures of ribosomal proteins of the archaebacterium Halobacterium marismortui and the eubacterium Bacillus stearothermophilus. Biochimie. 1991;73:657–668. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Band L, Yansura D G, Henner D J. Construction of a vector for cloning promoters in Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1983;26:313–315. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blum H, Beier H, Gross H J. Improved silver staining of plant proteins, RNA and DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis. 1987;8:93–99. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bork P, Dandekar T, Diaz-Lazcoz Y, Eisenhaber F, Huynen M, Yuan Y. Predicting function: from genes to genomes and back. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:707–725. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brombach M, Gualerzi C O, Nakamura Y, Pon C L. Molecular cloning and sequence of the Bacillus stearothermophilus translational initiation factor IF2 gene. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;205:97–102. doi: 10.1007/BF02428037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, et al. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busby S, Ebright R H. Promoter structure, promoter recognition, and transcription activation in prokaryotes. Cell. 1994;79:743–746. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coulombe B, Burton Z. DNA bending and wrapping around RNA polymerase: a “revolutionary” model describing transcriptional mechanism. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:457–478. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.457-478.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diekmann S. Analyzing DNA curvature in polyacrylamide gels. Methods Enzymol. 1992;212:30–46. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)12004-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubnau D, Davidoff-Abelson R. Fate of transforming DNA following uptake by competent Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1971;56:209–221. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta R S. Protein phylogenies and signature sequences: evolutionary relationships within prokaryotes and between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1997;72:49–61. doi: 10.1023/a:1000278224701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta R S. What are archaebacteria: life's third domain or monoderm prokaryotes related to gram-positive bacteria? A new proposal for the classification of prokaryotic organisms. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:695–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta R S, Golding G B. Evolution of HSP70 gene and its implications regarding relationships between archaebacteria, eubacteria, and eukaryotes. J Mol Evol. 1993;37:573–582. doi: 10.1007/BF00182743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haldenwang W G. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:1–30. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.1-30.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harwood C R, Williams D M, Lovett P S. Nucleotide sequence of a Bacillus pumilus gene specifying chloramphenicol acetyltransferase. Gene. 1983;24:163–169. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herwig S, Kruft V, Wittmann-Liebold B. Primary structures of ribosomal proteins L3 and L4 from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Eur J Biochem. 1992;207:877–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itoh T, Takemoto K, Mori H, Gojobori T. Evolutionary instability of operon structures disclosed by sequence comparisons of complete microbial genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:332–346. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaskunas R S, Lindahl L, Nomura M, Burgess R R. Identification of two copies of the gene for the elongation factor EF-Tu in E. coli. Nature. 1975;257:458–462. doi: 10.1038/257458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeon Y H, Negishi T, Shirakawa M, Yamazaki T, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Kyogoku Y. Solution structure of the activator contact domain of the RNA polymerase α subunit. Science. 1995;270:1495–1497. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonák J, Pokorná K, Meloun B, Karas K. Structural homology between elongation factors EF-Tu from Bacillus stearothermophilus and Escherichia coli in the binding site for aminoacyl-tRNA. Eur J Biochem. 1986;154:355–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawarabayasi Y, Hino Y, Horikawa H, et al. Complete genome sequence of an aerobic hyper-thermophilic crenarchaeon, Aeropyrum pernix K1. DNA Res. 1999;6:83–101. doi: 10.1093/dnares/6.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimura M. The nucleotide sequences of Bacillus stearothermophilus ribosomal protein S12 and S7 genes: comparison with the str operon of Escherichia coli. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;55:207–213. doi: 10.1271/bbb1961.55.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koonin E V, Bork P, Sander C. A novel RNA-binding motif in omnipotent suppressors of translation termination, ribosomal proteins and ribosome modification enzyme? Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2166–2167. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.11.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koonin E V, Galperin M Y. Prokaryotic genomes: the emerging paradigm of genome-based microbiology. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:757–763. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krásný L, Mesters J R, Tieleman L N, Kraal B, Fučík V, Hilgenfeld R, Jonák J. Structure and expression of elongation factor Tu from Bacillus stearothermophilus. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:371–381. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labes G, Simon R, Wohlleben W. A rapid method for the analysis of plasmid content and copy number in various Streptomycetes grown on agar plates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:2197. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.8.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lechner K, Heller G, Böck A. Organization and nucleotide sequence of a transcriptional unit of Methanococcus vannileii comprising genes for protein synthesis elongation factors and ribosomal proteins. J Mol Evol. 1989;29:20–27. doi: 10.1007/BF02106178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marion M J, Marion C. Localization of ribosomal proteins on the surface of mammalian 60S ribosomal subunits by means of immobilized enzymes. Correlation with chemical cross-linking data. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;143:1077–1083. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90518-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marion M J, Reboud J P. Two specific ribonucleoprotein fragments from rat liver 60S ribosomal subunits. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;17:4325–4337. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.17.4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marmur J. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from microorganisms. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matzura O, Wennborg A. RNAdraw: an integrated program for RNA secondary structure calculation and analysis under 32-bit Microsoft Windows. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:247–249. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Médigue C, Rouxel T, Vigier P, Hénaut A, Danchin A. Evidence for horizontal gene transfer in Escherichia coli speciation. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:851–856. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90575-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moszer I, Rocha E P, Danchin A. Codon usage and lateral gene transfer in Bacillus subtilis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:524–528. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukerji M, Mahadevan S. Characterization of the negative elements involved in silencing the bgl operon of Escherichia coli: possible roles for DNA gyrase, H-NS, and CRP-cAMP in regulation. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:617–627. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3621725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakanishi O, Oyanagi M, Kuwano Y, Tanaka T, Nakayama T, Mitsui H, Nabeshima Y, Ogata K. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequences of cDNAs specific for rat liver ribosomal proteins S17 and L30. Gene. 1985;35:289–296. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishi T, Itoh S. Enhancement of transcriptional activity of the Escherichia coli trp promoter by upstream A+T rich regions. Gene. 1986;44:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nitschké P, Gerdoux-Jamet P, Chiapello H, Faroux G, Hénaut C, Hénaut A, Danchin A. Indigo: a world wide web review of genomes and gene functions. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1998;22:207–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panayotatos N, Wells R D. Cruciform structures in supercoiled DNA. Nature. 1981;289:466–470. doi: 10.1038/289466a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pérez-Martín J, Lorenzo V. Clues and consequences of DNA bending in transcription. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:593–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Post L E, Arfsten A E, Reusser F, Nomura M. DNA sequences of promoter regions for the str and spc ribosomal protein operons in E. coli. Cell. 1978;15:215–229. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prod'hom G, Lagier B, Pelicic V, Hance A J, Cicquel B, Guilhot C. A reliable amplification technique for the characterization of genomic DNA sequences flanking insertion sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;158:75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rivetti C, Guthold M, Bustamante C. Wrapping of DNA around the E. coli RNA polymerase open promoter complex. EMBO J. 1999;18:4464–4475. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ross W, Gosink K K, Salomon J, Igarashi K, Zou C, Ishihama A, Severinov K, Gourse R L. A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the α subunit of RNA polymerase. Science. 1993;262:1407–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.8248780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shazand K, Tucker J, Grunberg-Manago M, Rabinowitz J C, Leighton T. Similar organization of the nusA-infB operon in Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2880–2887. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2880-2887.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh J, Mukerji M, Mahadevan S. Transcriptional activation of the Escherichia coli bgl operon: negative regulation by DNA structural elements near the promoter. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:1085–1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17061085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takami H, Takaki Y, Nakasone K, Hirama C, Inoue A, Horikoshi K. Sequence analysis of a 32-kb region including the major ribosomal gene clusters from alkaliphilic Bacillus sp. strain C-125. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1999;63:452–455. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tieleman L N, van Wezel G P, Bibb M J, Kraal B. Growth phase-dependent transcription of the Streptomyces ramocissimus tuf1 gene occurs from two promoters. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3619–3624. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3619-3624.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu L, Welker N E. Cloning and characterization of a glutamine transport operon of Bacillus stearothermophilus NUB36: effect of temperature on regulation of transcription. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4877–4888. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4877-4888.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamada M, Kubo M, Miyake T, Sakaguchi R, Higo Y, Imanaka T. Promoter sequence analysis in Bacillus and Escherichia: construction of strong promoters in E. coli. Gene. 1991;99:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yasumoto K, Yoshikava H, Takahashi H. Sequence analysis of a 50 kb region between spo0H and rrnH on the Bacillus subtilis chromosome. Microbiology. 1996;142:3039–3046. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-11-3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Young S F, Furano A V. Regulation of E. coli elongation factor Tu. Cell. 1981;24:695–706. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zengel J M, Archer R H, Lindahl L. The nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli fus gene, coding for elongation factor G. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:2181–2192. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.4.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zengel J M, Lindahl L. A secondary promoter for elongation factor Tu synthesis in the str ribosomal protein operon of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;185:487–492. doi: 10.1007/BF00334145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zengel J M, Lindahl L. Mapping of two promoters for elongation factor Tu within the structural gene for elongation factor G. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1050:317–322. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(90)90188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]