Abstract

Oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is effective at preventing HIV. However, low adherence is common and undermines these protective effects. This is particularly relevant for groups with disproportionately higher rates of HIV, including Black men who have sex with men (MSM). The current study tested the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a gamified mobile health contingency management intervention for PrEP adherence—called mSMART (Mobile App-Based Personalized Solutions for Medication Adherence of Rx Pill Tool). Fifteen Black MSM already prescribed PrEP in the community completed baseline and follow-up assessments separated by 8 weeks of using mSMART. Regarding feasibility, there was no study attrition, no mSMART functional difficulties that significantly interfered with use, and a mean rate of 82% daily mSMART use. Acceptability ratings were in the moderately to extremely satisfied range for factors such as willingness to recommend mSMART to others and user-friendliness, and in the low range for ratings on difficulty learning how to use mSMART. Scores on a system usability measure were in the acceptable range for 73% of the sample. Qualitative analysis of follow-up interviews identified individual components of mSMART that could be modified in future iterations to make it more engaging. PrEP composite adherence scores from biomarkers indicated an improvement from baseline to follow-up with a medium effect size, as well as a decrease in the number of perceived barriers to medication adherence. Findings indicate a future efficacy trial is needed to examine the effects of this gamified mobile health contingency management intervention on PrEP adherence.

Keywords: PrEP, MSM, mobile health, HIV prevention

Introduction

Despite advances in antiretroviral therapy and the landmark of treatment as prevention, HIV continues to threaten the health of millions annually (1). In the southern United States (US) alone there were 37,968 new infections in 2018, which accounted for over half of new infections in the US (2). Men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender persons, Black individuals, and Hispanics/Latinos continue to be disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic. Among incident HIV infection, 69% were among gay, bisexual, and other MSM (3). Black individuals represent the highest group for number of new HIV infections within this group (4). Novel HIV prevention strategies targeting Black MSM are needed to curb the ongoing HIV epidemic, particularly those living in the southern US.

Since receiving approval from the US Food and Drug Administration in 2012, oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) given as daily tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine combination (TDF/FTC) pill has been available as a highly effective tool in the armamentarium of HIV prevention strategies (5–13). However, new HIV diagnoses in the US only decreased 7% (3). This is likely due in part to low PrEP adherence—the protective effects of PrEP are strongly correlated with sustained adherence (7, 8, 14). A meta-analysis of PrEP trials demonstrated that adherence moderates acquiring HIV (15, 16). Adherence rates to this once-daily medication are highly variable in clinical trials (12–80%) (8, 17–22). In community settings, PrEP adherence rates can also be problematic. For example, in a predominantly Black and MSM sample recruited from a public health department in the southern US, PrEP adherence was 30% (23). Recent clinical trials indicate that younger participants, including MSM, are less likely to be adequately adherent to PrEP (7). This is notable because young Black MSM have a disproportionately higher incidence of HIV diagnosis (24). Given the importance of PrEP adherence, there is a need for evidence-based interventions to target this behavior.

Mobile health interventions provide a scalable, cost-effective platform that can be integrated into clinical settings and reach a large number of people (25). Interventions that utilize texting or email as mobile health interventions to support PrEP adherence have demonstrated acceptability and promising effects that warrant further evaluation in MSM (26, 27) or MSM and transgender women (28). Among other types of mobile health interventions—smartphone applications (apps)—for PrEP adherence, while studies are ongoing (29), initial findings have been mixed. One within subjects design among MSM demonstrated feasibility (30), though two trials comparing an app to an active treatment comparison condition among MSM and transgender women yielded null results (31, 32).

Interactive gaming can enhance health behavior motivation among a variety of clinical populations and may be beneficial to integrate with efforts to develop mobile health interventions. In one trial, an HIV prevention computer game targeting safer sex negotiation among adolescents and young adults demonstrated significant improvement in self-efficacy for partner negotiation and condom skills for those with lower self-efficacy at baseline (33). Interactive gaming for antiretroviral therapy adherence is feasible and acceptable, and is also associated with adherence among HIV positive young MSM (34). In terms of PrEP, one study of an iPhone gaming intervention for PrEP adherence demonstrated that it is acceptable among young MSM (35). In addition to an ongoing trial that has good preliminary support (36), one recently completed study examining the impact of an iPhone game against an active treatment comparison condition among MSM, optimal PrEP dosing was higher in the group that received the iPhone game (37). Such gamified interventions are needed to improve PrEP adherence among MSM, particularly Black MSM.

Contingency management (CM) is a behavioral approach that uses systematic reinforcement, typically in the form of money, dependent on the occurrence of a specific behavior and has been used for improving medication adherence (38)—this approach may be an important, novel addition to app-based PrEP adherence interventions given the effects of CM for medication adherence among HIV positive or exposed individuals. That is, CM improves adherence to antiretroviral medications for those who are HIV positive or HIV exposed (39, 40). In addition, our group recently developed an app—mSMART (Mobile App-Based Personalized Solutions for Medication Adherence of Rx Pill Tool)—that included CM to improve PrEP adherence among MSM with promising results (41). While mSMART was feasible and acceptable in that sample, we adopted a fixed-ratio schedule of reinforcement, which is less cost effective than other forms of CM, particularly an approach known as the “fishbowl” method (42). This method was developed by Petry and colleagues for substance use (43–46) and incorporates the principle of intermittent reinforcement. Using this method, instead of earning rewards with monetary value, individuals earn the opportunity to draw slips or tokens from a bowl that provide verbal praise without any monetary value or with a reward with monetary value. This is cost effective because the probability of drawing a slip or token for a reward with monetary value versus verbal praise without any monetary value can be varied. Also, the value of the actual reward can vary. For example, for meeting a goal (e.g., a negative urine drug screen), participants may be able to draw from slips of paper in a fishbowl with an opportunity to win a prize: 50% of the slips may state “Good job!” and not contain any monetary value, 42% of the slips may contain a prize with little monetary value, 7% of the slips may contain a prize with moderate monetary value, and 1% of the slips may contain a prize with high monetary value (47)—these probabilities are the same for every opportunity to draw a slip of paper. While fishbowl CM is more cost effective than traditional CM (46), it is just as efficacious (48). In addition, the fishbowl approach can be viewed as a way to gamify CM because patients get to “play” via the drawing. We propose to integrate this fishbowl approach to gamify mSMART.

Overall, PrEP adherence interventions are needed, particularly among Black MSM. Mobile health interventions can play a central role to support this effort. One limitation in the literature we identified above is a scarcity of gamified mobile health interventions for PrEP adherence. A CM fishbowl method is novel and may be a particularly promising solution to this limitation. To our knowledge, a gamified CM approach has not been developed nor tested in current app-based PrEP adherence interventions. The overarching aim of this study was to adapt a smartphone-based CM app designed to improve PrEP adherence among Black MSM—called mSMART— and add a gamification element by incorporating fishbowl CM. Whereas we have piloted mSMART in MSM utilizing a more traditional CM approach, the sample was predominantly White and the CM approach was not gamified (41). We aimed to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of mSMART with an adapted fishbowl CM feature among Black MSM over an 8 week period. Following a within group design, we predicted that the adapted mSMART would be feasible, acceptable, and demonstrate preliminary efficacy.

Methods

Participants

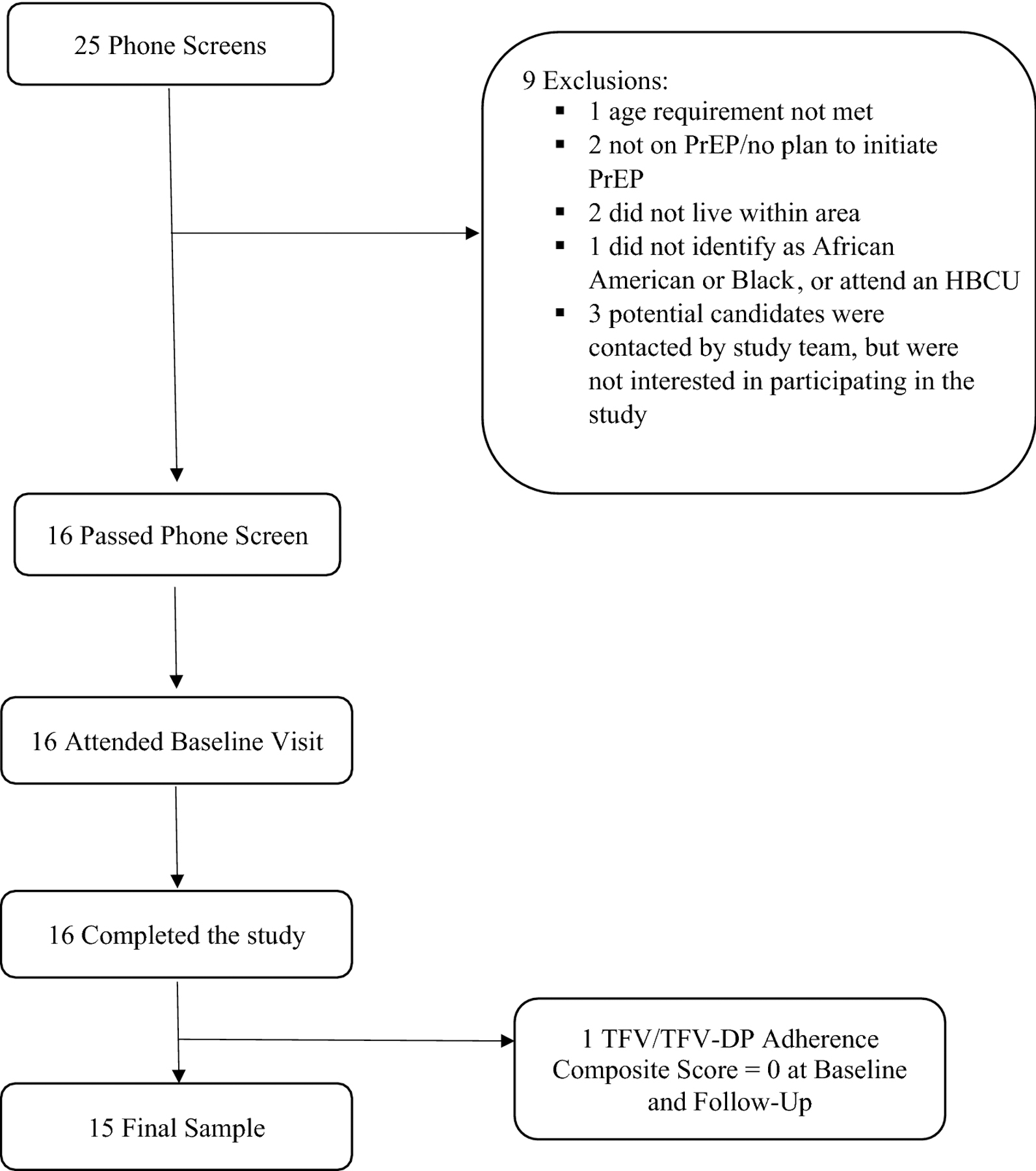

Participants were recruited in the Durham, NC community and local clinics via advertisements, word of mouth, and electronic health record search at a large medical center (including a PrEP clinic) after they agreed to be contacted by the study team following initial contact with their healthcare team. The final sample included 15 young Black MSM (Figure 1) with the majority (53%) being recruited from a PrEP clinic. Inclusion criteria were: age 18–30 years-old, assigned male sex at birth, reported having sex with men in the past six months, enrolled in a historically black college or university (HBCU) or identify as Black or African American, currently prescribed PrEP, possess an Android or iOS smartphone compatible with the mSMART smartphone app, and speak English. Exclusion criteria were: history of a chronic/significant medical or psychiatric condition that may interfere with study participation or being unable to attend all study visits. As noted in Figure 1, 16 participants completed the study, but the final sample was 15. The participant removed from the analysis had baseline and follow-up tenofovir (TFV)/TFV-diphosphate (TFV-DP) levels indicating that he was not taking PrEP. Furthermore, there was concern about the validity of the self-report data this participant provided. We subsequently added an inclusion criterion that participants provide evidence of their prescription for PrEP, such as taking a picture of their pill bottle with their name on it. Table 1 provides a summary of the sample demographics.

Figure 1.

Sample recruitment and participant flowchart. TFV: tenofovir, TFV-DP: tenofovir-diphosphate.

Table 1.

Sample demographics (n = 15)

| M (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 25.60 (2.10) |

|

| |

| Months on PrEPa | 12.00 (15.66) |

|

| |

| MSMb Risk Index Scorec | 15.27 (6.10) |

|

| |

| N (%) | |

|

| |

| Race | |

| Black | 14 (93%) |

| White | 0 (0%) |

| Asian | 0 (0%) |

| Multiracial | 1 (6%)d |

|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0%) |

| Not Hispanic | 13 (87%) |

| Not reported | 2 (13%) |

|

| |

| Employment status | |

| Full-Time | 10 (67%) |

| Part-Time | 2 (13%) |

| Unemployed | 1 (6%) |

| Dependent or Student | 2 (13%) |

|

| |

| Education | |

| Partial College | 5 (33%) |

| College Graduate | 6 (40%) |

| Postgraduate | 4 (27%) |

|

| |

| Smartphone device | |

| iPhone | 13 (87%) |

| Android | 2 (13%) |

Notes.

PrEP = Pre-exposure prophylaxis.

MSM = Men who have sex with men.

10 of the 15 participants (67%) exceeded the cut-off score of 10 and therefore are recommended to evaluate for PrEP for Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines (50, 51).

This participant included Black as a part of his racial identity.

Procedures

Baseline and follow-up in-person visits were separated by eight weeks in which participants used the mSMART app. At the baseline visit, participants completed an informed consent form and measures to characterize the sample, including demographics, the Risk Behavior Assessment for MSM (49) recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (50, 51) to characterize HIV risk over the past six months, and other measures administered to characterize the sample (see Supplement for the latter). Participants were registered with the mSMART app by a study team member on a secure website (52) and subsequently participants downloaded the app from the appropriate application distribution platform (i.e., Apple Store and Google Play). At that point participants received a brief overview of the mSMART app from a study team member. During the eight week period using the app, participants were called weekly to inquire about any technical difficulties with mSMART.

mSMART intervention.

The development of mSMART is described in a previous trial (41). mSMART is composed of six different components described in Table 2 that target PrEP adherence. In this study, the CM feature of mSMART was different from past iterations of mSMART. In a past iteration of mSMART for PrEP adherence, after participants logged a dose within the Medication Aide two hours prior to or following the pre-determined dose time, a fixed-ratio schedule of reinforcement was adopted and participants would earn $2 each time. The money earned was provided either weekly or at the end of four weeks, whichever the participant preferred (41). For the current study, we used an adapted CM “fishbowl” approach (46). Instead of earning money directly following TDF/FTC adherence as assessed by the Medication Aide, participants earned the opportunity to draw chances during a weekly “drawing.” That is, each day that the app indicated that if a participant was adherent to TDF/FTC, they earned one drawing for a virtual scratch-off ticket completed in the mSMART app at the end of the week. They were allowed to earn one drawing per day. Since taking TDF/FTC at least four times/week has an impact on reducing HIV infection (7), participants earned three bonus draws if they reached this weekly goal. For each draw at the end of each week, participants completed virtual “scratch off” tickets in the app. For each ticket, participants had a chance of receiving a non-monetary reinforcer (65.5% chance), $1 (26.7% chance), $20 (7.6% chance), and $100 (0.2% chance), which is consistent with past applications of this approach to antiretroviral medication use (53). CM monetary reinforcers were delivered on the same day for each weekly drawing in the form of an online Amazon gift card emailed directly to participants (processed by the study team and sent electronically via email).

Table 2.

mSMART description (adapted from Mitchell et al., 2018)

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Medication Aide | Participants would use this component to either enter a daily PrEP dose they had already taken or were about to take. For the former (i.e., daily dose already taken), the participant would manually enter into the app when they took their daily dose of PrEP by selecting the approximate time taken. For the latter (i.e., about to take the daily dose), the camera-based medication event-monitoring tool was activated, which involved taking the participant to a screen that prompted the app to activate the smartphone’s camera. Within the mSMART app, the camera would process the image of the pill in the participant’s hand (about 5–10 seconds) and indicate if the image was processed. These pictures were not examined by the study team or saved. |

| SMART Desk | This is an interactive space in which the app prompted once daily surveys (i.e., one to four questions) to gauge the participant’s knowledge or concerns about PrEP, knowledge about HIV and HIV prevention, and general medication use concerns or problems. These questions were phased out after any seven day window if participants were achieving 100% PrEP adherence (according to the app’s Medication Aide feature) and were phased back in if doses were missed. Notifications informing participants of missing a PrEP dose were also provided through the SMART Desk. |

| Adherence Strategies | This component introduced behavioral strategies to overcome barriers to PrEP adherence identified in the literature [45–48]. The strategies were displayed in a list form and were prioritized based on responses from participants in the SMART Desk. For example, if participants indicated they had difficulties remembering to take medications in the SMART Desk, the Adherence Strategies components would list strategies to help decrease forgetfulness associated with a taking medication regularly. Thus, adherence strategies were individualized based on participant responses in the SMART Desk. In addition to accessing adherence strategies by clicking on the Adherence Strategies icon, participants were automatically routed to specific Adherence Strategies from the SMART Desk after completing questions in the SMART Desk. This routing occurred regardless of the response selected with the intent to increase exposure to a variety of adherence strategies. |

| Coping Strategies | This component contained a list of common PrEP side effects and strategies on how to mitigate their impact on adherence. The most common side effects reported in the literature [e.g., upset stomach, headache, vomiting (50, 51)] were included. Participants could click on the Coping Strategies feature at any time. |

| Prescription and Doses | This component allowed participants to set up the time they wanted to receive a medication reminder (similar to receiving a text message). This time could be changed by participants at any point. |

| Treatment Progress | This component provided visual feedback about overall PrEP adherence (percent adherence) based on logging doses within a two-hour window of pre-determined dosing times. The pre-determined time was based on the time participants set in the Prescription and Doses component; logging doses was based on the participant logging a dose using the Medication Aide component. This feature also informed participants of how much money they had earned based on the CM procedures. |

Measures

Feasibility.

The following were measured to assess feasibility of mSMART: study attrition rate, rate of mSMART functioning issues over the 8 week course of using mSMART, rate of daily engagement with mSMART based on frequency of logging a daily dose over the 8 week course of using mSMART, and time needed to complete tasks on mSMART and number of prompts (initiated by either the participant or experimenter) to assist participants in completing the tasks during the follow-up visit. For the latter, participants completed pre-determined tasks within the mSMART app following guidelines from another smartphone application development study (54) and that we have administered in another study (41). An experimenter sat next to the participant, provided instructions on six different tasks, and recorded the time to complete each task. These six tasks participants were asked to complete within the mSMART app involved: (a) taking a picture of their medication, (b) changing the reminder time for daily dosing, (c) checking how much money was earned using the app, (d) checking for any questions prompted by mSMART, (e) looking up a detail about medication side effects, and (f) looking up a second detail about medication side effects. The time recorded for each task was based on the first attempt to complete it.

Acceptability.

The System Usability Scale (SUS) (55), an exit interview, and mSMART task performance were administered during the follow-up visit to assess acceptability.

The SUS is a 10-item scale that assesses responses on a 5-point Likert scale with scores ranging from 0 to 100. Scores at or above 68 were used to assess acceptability (56).

The exit interview was used in a previous PrEP adherence intervention study (41). Treatment acceptability ratings were provided by participants during the in-person interview and are reported on descriptively to assess acceptability. Participants were asked to rate overall satisfaction with mSMART (i.e., “What was your overall satisfaction with mSMART?”), mSMART usability on a daily basis (i.e., “How usable was mSMART on a daily basis?”), difficulty learning how to use mSMART (i.e., “How difficult was it to learn how to use mSMART?”), willingness to recommend mSMART to others (i.e., “Would you recommend mSMART to a friend who is taking a medication?”), and overall user-friendliness of mSMART (i.e., “How user-friendly was mSMART?”) on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (extremely).

Exit interviews also included open-ended questions for qualitative analysis of participant experiences and perceptions of mSMART. Interview questions addressed topics such as mSMART design features, navigation, barriers to use, and features that facilitated regular use similar to other studies examining participant experience with smartphone-based interventions [e.g., Vilardaga et al. (54)]. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and qualitatively analyzed. Qualitative analysis involved the use of categories we identified in previous treatment development work on mSMART for PrEP adherence (41). Two raters separately read through the transcripts in a Microsoft Word document and identified category endorsements for each participant. Each interview excerpt that was identified with a category endorsement was transferred to a Microsoft Excel document so that frequency counts for particular categories could be summed across the full sample. We have adopted similar procedures in past studies (41, 57). Inter-rater reliability between raters was assessed on a subset of interview excerpts. Kappa coefficient between raters was .82 when determining if a category should be endorsed.

Preliminary efficacy.

The number of perceived barriers to PrEP adherence was assessed with the 20-item Adherence Starts with Knowledge questionnaire (ASK-20) (58) at baseline and follow-up visits. A blood draw was also conducted at both visits to assess for PrEP adherence biomarkers. Blood samples were collected to assess concentrations of TFV in plasma and intracellular TFV-DP in upper layer packed cells to both characterize baseline concentrations and as a comparison with the follow-up concentrations [see methods described in Adams et al. (59)]. These concentrations were used to develop a semi-ordinal composite adherence score over the past four weeks ranging from 0 (low/no doses of drug identified: no detectable TFV and <10,000 fmol/mL TFV-DP) to 5 (good adherence: >10ng/mL TFV and >1,000,000 fmol/mL TFV-DP) (22). A score of 4 (i.e., four to five doses per week) or 5 (approximately daily dosing) is typically considered the level of adherence in which PrEP is efficacious among MSM (60).

Results

Feasibility

There was no study attrition—all participants who began using mSMART used it for the eight week duration and completed the study. Regarding mSMART functioning issues, 6 participants reported no issues when assessed during weekly phone calls from study staff, while 9 reported at least one issue. Identified issues were: connectivity issues (n = 5 participants), delay in receiving the weekly scratch off cards (n = 2 participants), log-in difficulties (n = 5 participants), and a delay in the Medication Aide indicating that a dose had been taken for the day (n = 3 participants). Regarding connectivity issues, these events all involved problems with the app not opening if they were not signed onto a wireless network. Connectivity issues all occurred within the first seven days of using the app with a duration of up to two weeks. Regarding log-in difficulties, participants reported that they had to enter in their four-digit entry code twice to open the app. Overall, the issues identified with using mSMART did not significantly impact daily engagement with the app.

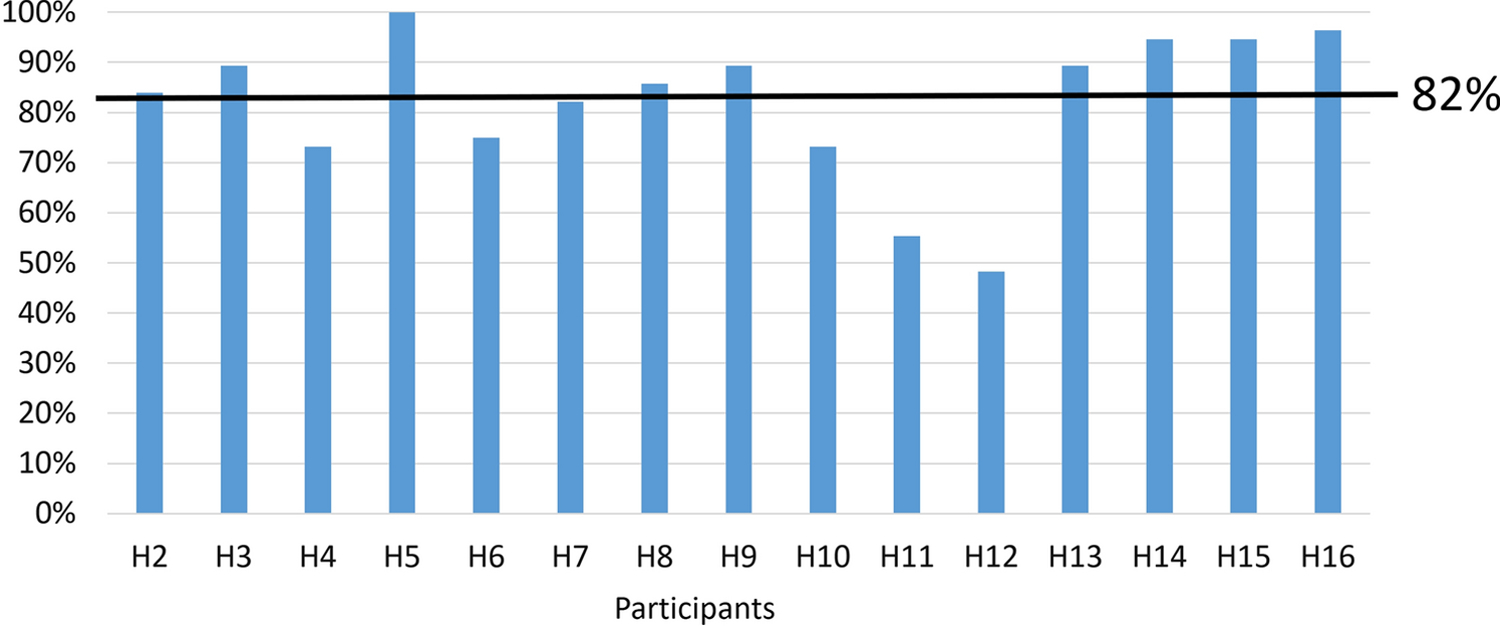

Participants also engaged with mSMART frequently based on rates of logging daily doses. Usage rates ranged from 48% to 100%—mean daily mSMART use was 82% across all participants. Figure 2 provides a summary of individual rates.

Figure 2.

Rates of logging PrEP adherence on mSMART (either using the camera or manual entry) for each participant.

Table 3 provides a summary of the amount of time to complete tasks within mSMART when timed by an examiner during the follow-up visit.

Table 3.

Follow-Up Visit mSMART Task Performance

| Task Instruction | # of seconds M (SD) |

# of prompts |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Show me where you go on the app to take a picture of your pill. | 1.87 (1.45) | 0 |

| 2. Change the time of your daily medication reminder. | 6.92 (9.18) | 1 |

| 3. Check to see how much money you’ve earned using mSMART. | 5.90 (7.25) | 2 |

| 4. Check to see if you have any questions on the SMART Desk. | 1.82 (0.92) | 0 |

| 5. Check to see if upset stomach is a side effect of using Truvada. | 3.80 (2.98) | 0 |

| 6. What percentage of people who take Truvada experience an upset stomach at some point? | 4.10 (2.82) | 0 |

Notes. For the number of prompts column, the prompt for task instruction 2 was requested by the participant. The two prompts for task instruction 3 was divided into 1 requested by the participant and 1 was offered by the examiner.

Acceptability

Table 4 provides a summary of acceptability ratings participants provided for mSMART. On average, participants reported they were moderately to extremely satisfied with the overall functioning of mSMART, usability, willingness to recommend to others, user-friendliness, and willingness to use if they just started taking PrEP. The average rating was in the “not at all” range regarding difficulty learning how to use mSMART. Using an SUS acceptability threshold score of ≥68, 11 of 15 participants (73%) had scores in the acceptable range. The average score on the SUS across the sample was 72.33 (SD = 15.82), which was also above the cut-off score.

Table 4.

Exit interview responses on a 4-point Likert scale

| Question | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| 1. What was your overall satisfaction with mSMART? | 3.38 (.50) |

| 2. How usable was mSMART on a daily basis? | 3.56 (.51) |

| 3. Would you recommend mSMART to a friend who is taking or just started taking Truvada? | 3.50 (.82) |

| 4.How user-friendly was mSMART? | 3.13 (.72) |

| 5. Would you use mSMART if you just started taking Truvada? | 3.69 (.79) |

| 6. How difficult was it to learn how to use mSMART? | 1.19 (.40) |

Notes. Responses option were: 1 = Not at all, 2 = Somewhat, 3 = Moderately, 4 = Extremely.

Qualitative analysis of follow-up visit interviews.

We review each category from the qualitative analysis below. See Table 5 for a summary.

Table 5.

Qualitative category endorsement rates

| Category | Endorsement Rate |

|---|---|

| 1. mSMART features | |

| Liked | 15 (100%) |

| Disliked | 12 (80%) |

| 2. Barriers to daily use | |

| Few barriers when taking PrEP | 14 (93%) |

| Some kind of barrier emerged | 13 (87%) |

| 3. mSMART aesthetics | |

| Liked | 11 (73%) |

| Disliked | 15 (100%) |

| 4. Learning how to use mSMART | |

| Easy | 14 (93%) |

| Difficult | 5 (33%) |

| 5. Features of mSMART that should be modifieda | 14 (87%) |

| 6. Likelihood of using mSMART depends on how soon you start PrEP or if you have adherence problems | 12 (80%) |

Notes.

indicates other than aesthetics captured in Category 2.

mSMART features that were liked or disliked.

All participants (n = 15) reported specific features of mSMART that they liked; 12 also reported features that they disliked. To characterize these participant preferences, we present the particular mSMART features most commonly identified and a descriptive comparison of those who liked and disliked the feature. The most frequently liked features of mSMART were the medication administration reminders (n = 11) and the “lottery” CM system (n = 11). Comments on liked aspects of the “lottery” CM included:

“I enjoyed the scratch-off game, actually… that was really fun to get, like to know that my cards were adding up.” 25 year-old Black MSM

However, not all participants appreciated the medication reminder feature. That is, four participants disliked the medication reminders, though the majority of these comments primarily involved dislike of different forms of communication from the app in general (e.g., prompts to complete daily assessments) and not specifically the actual daily medication reminders. Dislike of the notifications included:

“[The notifications] felt kind of patronizing.” 21 year-old multi-racial (including Black) MSM

There were no dislikes of the “lottery” CM system.

Other liked features of mSMART included medication adherence strategies and PrEP education (n = 9), tracking medication adherence (n = 9), coping strategies to manage negative side effects of PrEP (n = 8), and daily questions through the SMART Desk (n = 7). A few participants disliked these features, including the medication adherence strategies and PrEP education (n = 3), tracking medication adherence (n = 4), coping strategies to manage negative side effects of PrEP (n = 2), and daily questions through SMART Desk (n = 4). Because the purpose of mSMART is to improve medication adherence, we were particularly interested in reasons participants disliked tracking medication adherence. Out of these 4 participants, 3 felt that the way adherence was measured was essentially too strict or not fully representative of their adherence (i.e., if they took PrEP that day but outside of the window of time determined on the app, they would receive feedback that they were non-adherent). The other participant felt that he knew what his adherence was already and therefore feedback from the app was not necessary.

Among liked features of the app, relatively fewer participants found the use of camera (n = 5) and setting reminders to take PrEP (n = 3) enjoyable—a nearly equal amount of participants disliked these features. Four participants liked the non-monetary rewards (i.e., positive feedback from the app) and zero had negative comments regarding this feature.

There were features of the mSMART app that were not specifically evaluated through the interviews. Participants (n = 9) reported additional features liked, such as:

“It felt secure in that there was a PIN, just in case wanted to steal my phone, they don’t know what meds I’m taking.” 25 year-old Black MSM

Other participants (n = 10) reported features disliked, particularly the predetermined time each day to take a dose, such as:

“like it not being flexible enough with the time. … on the weekends, depending on what I had going on, or what I did the night before, um you know, being up between that 7:30 and 9:30 window just to take the pill—well, to record, because I took the pill everyday—but to take it in that timeframe was frustrating because it wasn’t, it wasn’t flexible enough. … a setting … maybe on the weekend I could adjust it or something, just because, you know, I sleep in on the weekends.” 28 year-old Black MSM

Barriers to Daily mSMART use.

Nearly all participants (n = 14) reported using the app when it was time to take PrEP with few barriers. However, 13 participants reported the presence of at least one barrier to daily use of the app in general, particularly with technical issues with the app. Technical issues with mSMART included connection problems (n = 8) and “slow speed” (n = 3). Comments the typified these responses included:

“Yeah, it glitched sometimes and you just kind of have to like, go out of the app and then log back in and that, it would work the second time. But, yeah, it was a couple of like glitches plus the time I showed you like the, the connection error—that thing.” 25 year-old Black MSM

Several participants (n = 8) reported barriers to daily use of the app that were not explicitly asked during the interviews. These barriers included:

“it depends where you put it on your phone. … where you put it in your opening menu will impact sort of the layers or barriers to entry. … I probably should’ve just put it in my, um, shortcuts, right? Like on my, on the bottom half of my iPhone opening menu.” 25 year-old Black MSM

And

“… the biggest barrier to me is getting the notification and not being around your medicine and then you can’t, there’s no way to like change it, because once you’re late, you’re too late. … like if I’m at work and I have a 5:30 time and it’s over at 7:30 and I get off at 8 and my pills are in the car or something, I mean, it’s counted as a missed dose … So, maybe there should be a function where you, like if it reminds you it should say like, ‘it might be later, like can you remind me again in two-hours.’” 25 year-old Black MSM

On the topic of barriers, participants also commented on factors that may facilitate use of mSMART. Two respondents would use mSMART for other medications. There was one suggestion to pair the camera feature to help identify additional medications:

“I would like to know if the camera could notify different medications. So, if you take like five medications, if it could recognize all of them…I think that would be my biggest improvement…. if you’re taking both your medications at once, if you could just scan, you can scan all of them and recognize them—that would help.” 27 year-old Black MSM

One participant also suggested additional daily use features including:

“I’m changing prescribers. And so like, I’m trying to go through that process and like, the app could be helpful if, you know, because I think there is a website of like registered, um, PrEP prescribers.” 27 year-old Black MSM

No participants thought that linking mSMART to electronic health records or medical providers would be beneficial or detrimental to daily use.

mSMART aesthetics.

Opinions on mSMART app aesthetics were mixed. While 11 participants noted aesthetics they liked, all participants (n = 15) also commented on aesthetics they disliked. Viewpoints on the color and design of the app were split. Seven participants liked the app color and nine liked the design, whereas six did not like the colors and thought the app looked outdated. Participants commented:

“It was pretty basic…Like, there’s only six little icons…I feel like some of the apps, like some of the icons kind of can be merged…Yeah, like you can definitely merge like the adherence strategy and SMART Desk.” 25 year-old Black MSM

And

“I think it could use like some more color…In just a more user-friendly way … I think like after entering like the home screen—which was like blue and yellow I believe—um, after like entering that screen, um, the sign-in screen, it’s just kind of gray and white.” 24 year-old Black MSM

Additional feedback on aesthetics disliked included too much text and lack of graphics (n = 4) and the perception that the app was not engaging (n = 7). One participant stated:

“Not that it, like, needs to be entertaining or like seamless, or beautiful, or elegant. But like it wasn’t, but I mean like, it wasn’t like other, you know what I mean, expensive apps, but not like more expensive but more broadly used apps.” 21 year-old multi-racial (including Black) MSM

And

“[The app was] a little clinical… it’s clear that it’s like a medical app, it’s clear that it’s striving for accuracy, um, it’s striving to be informative, um, and it really, you know, wants to provide the barebones for someone’s adherence to the medication. The problem is that it’s not fun. Um, and it’s not particularly a rewarding experience.” 25 year-old Black MSM

Nearly all participants provided suggestions on how the app could improve. These improvements included:

“but I think when you launch the app or when you have it in beta, um, you might want to experiment with really what people are going to use this for are like, they’re adhering to the medication, so like the picture and getting information about like usage. I, I really think you only need those two windows, um, and then out of, say the second window, which is coping/adherence strategies, you can then unfold to different options, right? …. no more than three options when you open the menu.” 25 year-old Black MSM

Learning how to use mSMART.

Most participants (n = 14) thought aspects of mSMART were easy to use. Specifically, most felt that the app was easy to navigate (n = 13) and learning how the different buttons provide different features of the app were easy to learn (n = 6). Two interviewees provided additional comments on features of the app that were easy to learn. No participants thought that the instructional video was unnecessary. Some of the insight included:

“it’s a good layout, umm, it’s fairly straightforward. … and as far as the accessibility, everything is right, it’s right where you need it to be.. it’s straightforward.” 27 year-old Black MSM

Only five participants found features of mSMART difficult to learn how to use. These included:

“I think navigation was difficult at times when I was looking for certain information…Like when I was actually looking for, um, like the doses I had taken over like the course of the past week, I realized that I couldn’t find them.” 24 year-old Black MSM

mSMART features that should be added.

Many of the mSMART features suggested for improvement were based on aesthetics and described in the previous section. Other features suggested for the mSMART app included fewer buttons (n = 4) and reminder snooze function or notification that does not go away (n = 3).

Fewer participants requested the option for a thumbprint log-on (n = 2) or an option to opt out of entering their PIN each time the app opens (n = 2). A small number of participants (n = 2) wanted additional education on PrEP and social aspects, such as dating someone with HIV. One participant was interested in adding content on sexually transmitted infections (STI), integration with their pharmacy, and adding more gamification to the app. No interviewees provided viewpoints on the addition of a “search” feature, ability to log STI/HIV testing, or making questions more engaging.

Likelihood of using mSMART.

Overall, 12 participants reported that the likelihood of using mSMART depends on how recently PrEP was started or if there are adherence problems. Regarding the former, most participants (n = 11) stated that the app would have been helpful when they first started on PrEP. Conversely, three interviewees felt that the app was just as helpful at the time they used it as it would have been when starting on PrEP. One participant noted:

“I think overall it was a good app. I would absolutely recommend it to new users. I mean, I honestly think that is the target for this app. My friends have been on (PrEP) for a while so I don’t think it would be necessarily helpful, you know, recommending it to them, but a new user, absolutely; I think it’s a great app.” 28 year-old Black MSM

Six participants thought that the target population for this app should be persons with adherence difficulties with PrEP rather than those who just started on PrEP. One comment was:

“So, I wouldn’t recommend the app to someone who is just starting Truvada … when you just starting taking Truvada and you’re going through all the side effects or whatever, so I had to learn like, when to take it, like how to take it, water, food, night, day, blah, blah, blah. So, trying to do that and deal with the app at the same time … it just would’ve been too much going on trying to starting new medication and trying to learn the app at the same time.” 25 year-old Black MSM

Preliminary efficacy

PrEP composite adherence scores based on TFV/TFV-DP values indicated that PrEP adherence was 3.60 (SD = 1.68) at baseline and 4.60 (SD = 0.83) at follow-up. The magnitude of this change was medium with a Cohen’s d effect size of .59. The majority of the sample, 73%, yielded a baseline composite adherence score at the therapeutic level (i.e., n = 11 had a score of 4 or 5). This increased to 93% (n = 14) at the follow-up visit. Overall, composite adherence scores improved for 40% of the sample (n = 6), worsened for 7% (n = 1), and did not change for 53% (n = 8). Regarding cases in which adherence scores did not change, all of these participants had composite adherence scores at a therapeutic level of baseline.

The perceived number of barriers to medication adherence on the ASK-20 was 3.33 (SD = 3.18) at baseline and 1.80 (SD = 1.78) at follow-up. The magnitude of this change was medium with a Cohen’s d effect size of −.48. Sixty percent of the sample reported a reduction in number of perceived barriers (n = 9), 13% (n = 2) did not change, and 27% (n = 4) reported an increase.

Discussion

This study examined the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a smartphone-based app designed to improve PrEP adherence among Black MSM called mSMART. A previous iteration of the app demonstrated feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy in a sample of predominantly White MSM (41). For the current study, the CM component of mSMART was gamified by adopting the low cost “fishbowl” method. To our knowledge, this is the first smartphone app targeting medication adherence that has applied this CM approach and is the only mobile app developed specifically for PrEP that includes CM.

Findings indicated that the app is feasible and acceptable over an 8-week period using traditional quantitative methods, although qualitative analysis of in-depth follow-up interviews identified areas the app may be refined. For example, aesthetic features of the app, appropriate timing to use the app relative to how long someone has been on PrEP, and the addition of more options to set an alarm for dose reminders were identified by participants. Findings from this pilot study indicate such areas that can be adapted for a future efficacy study in which mSMART is tested in comparison to an active treatment comparison condition. The current study established preliminary efficacy and effect sizes for outcome variables—PrEP composite adherence scores based on TFV/TFV-DP values and perceived barriers to medication adherence—that can be used to statistically power an efficacy trial.

Preliminary efficacy findings were promising. Although a ceiling effect could have emerged given the high rates of PrEP use at a therapeutic level of baseline at 73% using a biomarker of PrEP adherence, this rate increased to 93% at follow-up. Overall, these PrEP biomarker composite adherence scores that ranged from 1 to 5 increased an entire point (i.e., baseline group average scores were 3.60 at baseline and 4.60 at follow-up) and overall yielded a medium effect size. Similarly, perceived barriers to medication adherence decreased with a medium effect size. Future studies should consider the population targeted for mSMART. For example, while the preliminary efficacy from this study is promising, the majority of the sample was largely PrEP adherent at baseline and may potentially respond differently to mSMART than other more difficult-to-treat subgroups, such as those who have a history of poor medication adherence. Other subgroups identified from our qualitative analysis that may be promising to target in future trials include those just initiating PrEP. Therefore, we recommend that future studies target these groups that may particularly benefit from a PrEP adherence intervention. In addition, given that retention in PrEP care is suboptimal (61), it may be beneficial to assess how an intervention like mSMART that targets adherence can impact PrEP care retention.

CM is an intervention based on a core behavioral principle of reinforcement: if a behavior is positively reinforced in close proximity to its occurrence, then it will increase in frequency. CM has been used to improve medication adherence in a number of populations (38), including those who are HIV positive or HIV exposed (39, 40) and for PrEP adherence (41). While this study adapted the CM component of mSMART that we hypothesize is a core feature of the app that improves PrEP adherence, mSMART includes additional interventions separate from CM that may have a similar or stronger impact on adherence. For example, dose reminders for PrEP adherence is a component of mSMART and other PrEP adherence interventions (26) and, like CM, is also based on a behavioral principle (i.e., stimulus control). Studies are needed to assess how these intervention components compare. Other gamified mobile PrEP adherence interventions include features that overlap with mSMART (e.g., questions to develop knowledge about HIV and PrEP, the use of financial rewards [though contingent on app use and not PrEP adherence], and feedback about adherence) and features that are not incorporated in mSMART (e.g., social discussion board for peer-to-peer communication and a video game) (35–37). One direction for future studies might be testing which particular components of these various PrEP adherence interventions are more efficacious than others, including whether the gamified CM feature in mSMART adds additional benefits on PrEP adherence than the non-CM features. To move the field of mobile health gamified PrEP adherence interventions forward more broadly, it would be beneficial to identify multiple efficacious and scalable components so that patients can choose from different options and can match interventions with their preferences and needs. Additionally, studies that can identify which components are more efficacious for particular PrEP subgroups would be beneficial. For example, CM as administered in this study may be differentially efficacious for different individuals on PrEP.

Another feature for future consideration is a cost benefit analysis of CM for PrEP adherence. While the fishbowl approach to CM is more cost effective than tradition CM procedures (46), there are financial costs to the use of CM according the procedures we adopted in this study. However, despite the financial cost of CM incentives (e.g., average cost per subject with CM in this study was $156 over an eight week period [SD = $40.93, range: $93-$254]), these costs are negligible in the cost of lifelong treatment for HIV. For example, in 2010 US dollars, the lifetime treatment cost of an HIV infection is approximately $380,000 (62). Given the increasing recognition of the financial benefit of health promotion interventions that offset the costs of otherwise poorer health outcomes, the use of financial incentives is increasing (63), particularly in government-sponsored systems (64, 65) and large healthcare insurers (66).

In addition, one way to minimize concerns about the financial cost of CM for PrEP might be the administration of CM as a feature of mSMART for a limited time and then remove it while relying on other strategies introduced through the app to maintain initial gains established with CM. For example, if the CM feature of mSMART can help with establishing adherence upon initiating PrEP and gradually be removed while other features are gradually introduced, then the costs of mSMART may be reduced without potentially impacting efficacy. Such an approach has been demonstrated in other populations (67, 68).

The current study has a number of strengths for a phase I trial, including the use of biomarkers as a measure of adherence as an outcome measure and a novel, gamified CM approach administered remotely. In terms of limitations, the sample size for this pilot trial is small—future studies are needed with a larger sample. Future studies are needed to demonstrate the impact of mSMART on adherence in comparison to a control group in a larger sample. As outlined above, future studies also need to assess the impact of mSMART on particular subgroups on PrEP (e.g., those just initiating PrEP) and to address which components of the intervention are most efficacious. In addition, while the current study examined mSMART in Black MSM and a previous study examined mSMART among predominantly White MSM, future studies are needed to examine mSMART among other MSM and non-MSM groups. Relatedly, we have examined mSMART among young adults, but not among adolescents or older adults. Future studies will also need to consider generalizability regarding other aspects of sample composition, such as samples characterized by higher levels of substance use and depressed mood (see Supplement). An additional consideration involves generalizability of mSMART to rural MSM. The current study took place in a predominantly urban medical center setting, which may be a group with different PrEP adherence intervention needs than rural MSM [e.g., Owens et al. (69)]. Finally, while the intervention tested in this study examined PrEP adherence, future studies should address additional aspects of the PrEP care continuum to further reduce rates of HIV infection. For example, PrEP uptake is lower among young Black MSM than young White MSM (4.7% vs. 29.5%, respectively) (70). Factors that contribute to lower levels of uptake should also be targeted in interventions to further reduce racial disparities in HIV infection.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrated that mSMART as a novel, gamified CM intervention is feasible, acceptable, and has preliminary efficacy among Black MSM. The mobile health format makes mSMART a scalable intervention that could be administered with fidelity in real-world clinical settings. However, future efficacy trials are needed to demonstrate if mSMART impacts adherence in a well-powered study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Tony McLaurin for assistance with recruitment and data collection, and Goutam Satapathy, Ph.D., for assistance with mSMART.

Funding:

This research was supported by both the Duke University and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Centers for AIDS Research (CFARs), NIH funded programs (5P30 AI064518 and P30 AI050410, respectively). CMB received support from National Institutes of Health Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (5T32AI007392).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethics approval: This study was reviewed and approved by the IRB at Duke University (Pro00076107). The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov under NCT03080597.

Consent to participate: Participants reviewed and signed an individual voluntary written informed consent form with a trained member of the study team.

Consent for publication: Participants consented to have de-identified data published.

Availability of data and material: Study data available upon request.

Code availability: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Treatment as Prevention Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/art/index.html. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- 2.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Statistics Overview – HIV Surveillance Report Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/index.html. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- 3.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Overview: Data & Trends: U.S. Statistics. Key Points: HIV Incidence Available at: https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- 4.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States and Dependent Areas Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/ataglance.html. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- 5.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Results of the iPrEx open-label extension (iPrEx OLE) in men and transgender women who have sex with men: PrEP uptake, sexual practices, and HIV incidence. AIDS 2014 Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [abstract TUAC0105LB]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molina J, Capitant C, Charreau I, et al. On demand PrEP with oral TDF-FTC in MSM: Results of the ANRS Ipergay Trial. 2015 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Seattle, WA, 2015. [abstract #23LB]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14(9):820–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 2010;363(27):2587–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baeten JM, Heffron R, Kidoguchi L, Celum C. Near elimination of HIV transmission in a demonstration project of PrEP and ART. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Seattle, WA, 2015. p. 23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin M, Mock PA, Curlin ME, Vanichseni S. Preliminary follow-up of injecting drug users receiving preexposure prophylaxis. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Seattle, WA, 2015. p. 23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson L, Taylor D, Roddy R, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for prevention of HIV infection in women: a phase 2, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. PLoS clinical trials 2007;2(5):e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCormack S, Dunn D. Pragmatic open-label randomised trial of preexposure prophylaxis: the PROUD Study. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Seattle, WA, 2015. p. 23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grohskopf LA, Chillag KL, Gvetadze R, et al. Randomized trial of clinical safety of daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate among HIV-uninfected men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;64(1):79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amico KR, Stirratt MJ. Adherence to preexposure prophylaxis: current, emerging, and anticipated bases of evidence. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59 Suppl 1:S55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fonner G, Grant R, Baggaley R. Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for all populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness, safety, and sexual and reproductive health outcomes Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SH, Tanner A, Friedman DB, Foster C, Bergeron C. Barriers to clinical trial participation: comparing perceptions and knowledge of african american and white south carolinians. J Health Commun 2015;20(7):816–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med 2012;367(5):399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381(9883):2083–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med 2015;372(6):509–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2012;367(5):423–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med 2012;367(5):411–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corneli AL, Deese J, Wang M, et al. FEM-PrEP: adherence patterns and factors associated with adherence to a daily oral study product for pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66(3):324–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clement ME, Johnston BE, Eagle C, et al. Advancing the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis continuum: a collaboration between a public health department and a federally qualified health center in the southern United States. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2019;33(8):366–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in U.S. HIV diagnoses, 2005–2014 Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/373332015. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- 25.Miller G The smartphone psychology manifesto. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012;7(3):221–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu AY, Laborde ND, Coleman K, et al. DOT diary: developing a novel mobile app using artificial intelligence and an electronic sexual diary to measure and support PrEP adherence among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuchs JD, Stojanovski K, Vittinghoff E, et al. A mobile health strategy to support adherence to antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2018;32(3):104–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore DJ, Jain S, Dube MP, et al. Randomized controlled trial of daily text messages to support adherence to PrEP in at-risk for HIV individuals: the TAPIR study. Clin Infect Dis 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strong C, Wu HJ, Tseng YC, et al. Mobile app (UPrEPU) to monitor adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men: protocol for a user-centered approach to mobile app design and development. JMIR Res Protoc 2020;9(12):e20360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weitzman PF, Zhou Y, Kogelman L, et al. mHealth for pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence by young adult men who have sex with men. Mhealth 2021;7:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Songtaweesin WN, Kawichai S, Phanuphak N, et al. Youth-friendly services and a mobile phone application to promote adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis among adolescent men who have sex with men and transgender women at-risk for HIV in Thailand: a randomized control trial. J Int AIDS Soc 2020;23 Suppl 5:e25564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van den Elshout MAM, Hoornenborg E, Achterbergh RCA, et al. Improving adherence to daily preexposure prophylaxis among MSM in Amsterdam by providing feedback via a mobile application. AIDS 2021;35(11):1823–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas R, Cahill J, Santilli L. Using an interactive computer game to increase skill and self-efficacy regarding safer sex negotiation: field test results. Health Educ Behav 1997;24(1):71–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hightow-Weidman L, Muessig K, Knudtson K, et al. A gamified smartphone app to support engagement in care and medication adherence for HIV-positive young men who have sex with men (AllyQuest): development and pilot study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2018;4(2):e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whiteley L, Mena L, Craker LK, Healy MG, Brown LK. Creating a theoretically grounded gaming app to increase adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis: lessons from the development of the viral combat mobile phone game. JMIR Serious Games 2019;7(1):e11861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LeGrand S, Knudtson K, Benkeser D, et al. Testing the efficacy of a social networking gamification app to improve pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence (P3: Prepared, Protected, emPowered): protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2018;7(12):e10448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whiteley L, Craker L, Haubrick KK, et al. The impact of a mobile gaming intervention to increase adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis. AIDS Behav 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petry NM, Rash CJ, Byrne S, Ashraf S, White WB. Financial reinforcers for improving medication adherence: findings from a meta-analysis. Am J Med 2012;125(9):888–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mbuagbaw L, Sivaramalingam B, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART): a systematic review of high quality studies. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2015;29(5):248–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Landovitz RJ, Fletcher JB, Shoptaw S, Reback CJ. Contingency management facilitates the use of postexposure prophylaxis among stimulant-using men who have sex with men. Open Forum Infect Dis 2015;2(1):ofu114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitchell JT, LeGrand S, Hightow-Weidman LB, et al. Smartphone-based contingency management intervention to improve pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence: pilot trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6(9):e10456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stitzer ML, Vandrey R. Contingency management: utility in the treatment of drug abuse disorders. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008;83(4):644–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petry NM, Martin B. Low-cost contingency management for treating cocaine- and opioid-abusing methadone patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002;70(2):398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, Kranzler HR. Give them prizes, and they will come: contingency management for treatment of alcohol dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000;68(2):250–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petry NM, Martin B, Simcic F Jr. Prize reinforcement contingency management for cocaine dependence: integration with group therapy in a methadone clinic. J Consult Clin Psychol 2005;73(2):354–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petry NM, Tedford J, Austin M, Nich C, Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. Prize reinforcement contingency management for treating cocaine users: how low can we go, and with whom? Addiction 2004;99(3):349–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petry NM. Contingency management treatments. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:97–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petry NM, Alessi SM, Marx J, Austin M, Tardif M. Vouchers versus prizes: contingency management treatment of substance abusers in community settings. J Consult Clin Psychol 2005;73(6):1005–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Menza TW, Hughes JP, Celum CL, Golden MR. Prediction of HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36(9):547–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States - 2014: Clinical Providers’ Supplement Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/PrEPProviderSupplement2014.pdf; 2014. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- 51.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States - 2014: A Clinical Practice Guideline www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf2014. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- 52.Intelligent Automation, Inc. mSMART website Available at: https://msmart.i-a-i.com/. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- 53.Rosen MI, Dieckhaus K, McMahon TJ, et al. Improved adherence with contingency management. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2007;21(1):30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vilardaga R, Rizo J, Kientz JA, McDonell MG, Ries RK, Sobel K. User experience evaluation of a smoking cessation app in people with serious mental illness. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18(5):1032–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brooke J SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale. Usability Eval Ind 1996;189:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sauro JA. A practical guide to the System Usability Scale: Background, benchmarks, and best practices. Measuring Usability LLC 2011.

- 57.Mitchell JT, Sweitzer M, Tunno A, Kollins SH, McClernon FJ. “I use weed for my ADHD”: a qualitative analysis of online forum discussions on cannabis and ADHD. PloS One 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hahn SR, Park J, Skinner EP, et al. Development of the ASK-20 adherence barrier survey. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24(7):2127–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adams JL, Sykes C, Menezes P, et al. Tenofovir diphosphate and emtricitabine triphosphate concentrations in blood cells compared with isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells: a new measure of antiretroviral adherence? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;62(3):260–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med 2012;4(151):151ra25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chan PA, Patel RR, Mena L, et al. Long-term retention in pre-exposure prophylaxis care among men who have sex with men and transgender women in the United States. J Int AIDS Soc 2019;22(8):e25385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Cost-effectiveness 2019 Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/programresources/guidance/costeffectiveness/index.html. Accessed June 5, 2021.

- 63.Mantzari E, Vogt F, Shemilt I, Wei Y, Higgins JP, Marteau TM. Personal financial incentives for changing habitual health-related behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 2015;75:75–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DePhilippis D, Petry NM, Bonn-Miller MO, Rosenbach SB, McKay JR. The national implementation of Contingency Management (CM) in the Department of Veterans Affairs: Attendance at CM sessions and substance use outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;185:367–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petry NM, DePhilippis D, Rash CJ, Drapkin M, McKay JR. Nationwide dissemination of contingency management: the Veterans Administration initiative. Am J Addict 2014;23(3):205–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Volpp KG, Pauly MV, Loewenstein G, Bangsberg D. P4P4P: an agenda for research on pay-for-performance for patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(1):206–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carpenter VL, Hertzberg JS, Kirby AC, et al. Multicomponent smoking cessation treatment including mobile contingency management in homeless veterans. J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76(7):959–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hertzberg JS, Carpenter VL, Kirby AC, et al. Mobile contingency management as an adjunctive smoking cessation treatment for smokers with posttraumatic stress disorder. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15(11):1934–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Owens C, Hubach RD, Lester JN, et al. Assessing determinants of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adherence among a sample of rural Midwestern men who have sex with men (MSM). AIDS care 2020;32(12):1581–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Schneider J, Garofalo R, Fujimoto K. Use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in young men who have sex with men is associated with race, sexual risk behavior and peer network size. AIDS Behav 2017;21(5):1376–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.