Abstract

Introduction:

In fostering community and culture through entertainment in shared spaces, performing arts venues have also become targets of terrorism. A greater understanding of these attacks is needed to assess the risk posed to different types of venues, to inform medical disaster preparedness, to anticipate injury patterns, and to reduce preventable deaths.

Methods:

A search of the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) was conducted from the year 1970 through 2019. Using pre-coded variables for target/victim type and target subtype, attacks involving “business” and “entertainment/cultural/stadium/casino” were identified. Attacks targeting performing arts venues were selected using the search terms “theater,” “theatre,” “auditorium,” “center,” “hall,” “house,” “concert,” “music,” “opera,” “cinema,” and “movie.” Manual review by two authors was performed to confirm appropriateness for inclusion of entries involving venues where the primary focus of the audience was to view a performance. Descriptive statistics were performed using R (version 3.6.1).

Results:

A total of 312 terrorist attacks targeting performing arts venues were identified from January 1, 1970 through December 31, 2019. Two-hundred nine (67.0%) attacks involved cinemas or movie theaters, 80 (25.6%) involved unspecified theaters, and 23 (7.4%) specifically targeted live music performance venues. Two-hundred thirty-four (75.0%) attacks involved a bombing or explosion, 50 (16.0%) damaged a facility or infrastructure, and 17 (5.4%) included armed assault. Perpetrators used explosives in 234 (75.0%) attacks, incendiary weapons in 50 (16.0%) attacks, and firearms in 19 (6.1%) attacks. In total, attacks claimed the lives of 1,307 and wounded 4,201 persons. Though fewer in number, attacks against music venues were responsible for 29.4% of fatalities and 35.0% of those wounded, and more frequently involved the use of firearms. Among 95 attacks falling within the highest quartile for victims killed or wounded (>two killed and/or >ten wounded), 83 (87.4%) involved explosives, seven (7.4%) involved firearms, and three (3.2%) involved incendiary methods.

Conclusion:

While uncommon, terrorist attacks against performing arts venues carry the risk for mass casualties, particularly when explosives and firearms are used.

Keywords: disaster medicine, Emergency Medical Services, emergency preparedness, performing arts, terrorism

Introduction

The performing arts are a vital expression of human creativity and values, fostering community and culture. Venues for presenting the performing arts to the public can include cinemas, theaters, concert halls, and opera houses as well as multi-purpose spaces such as arenas, amphitheaters, stadiums, and other outdoor locations (eg, festival sites). In bringing together large numbers of people to experience the arts, these venues have been targets of terrorism with important implications for medical disaster preparedness and prehospital emergency care.

Attacks against the Bataclan concert hall in Paris, France in 2015; Manchester Arena in the United Kingdom in 2017; and the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas, Nevada (USA) later the same year underscore the vulnerability of performing arts venues to terrorist attack with the potential for mass casualties. In such events, multi-tiered, highly-integrated emergency responses are necessary not only to address the on-going threat posed by the attackers, but render time-critical medical care to victims to save life and limb. Apart from such high-profile attacks, historical trends in and characteristics of terrorist attacks against performing arts venues have not been well-described. A greater understanding of these attacks is needed to assess the overall risk posed to such venues, to inform emergency planning, to anticipate likely victim injury patterns, and to reduce preventable deaths in their aftermath.

In this study, a comprehensive unclassified terrorist attack database was analyzed to determine the frequency of attacks against performing arts venues, the methods of attack used, and the extent of the casualties incurred over the past 50 years.

Methods

The Global Terrorism Database (GTD) is an open-source database maintained by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START; College Park, Maryland USA) reporting information on terrorist attacks occurring from 1970 through 2019.1 To be included in the GTD, an incident must be intentional, entail some level of violence or immediate threat of violence, and be perpetrated by sub-national actors. Furthermore, an incident must meet at least two of the following three criteria: (1) the act must be aimed at attaining a political, economic, religious, or social goal; (2) there must be evidence of an intention to coerce, intimidate, or convey some other message to a larger audience than the immediate victims; and/or (3) the action must be outside the context of legitimate warfare activities.1

A search of the GTD was performed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standard.2 Using pre-coded variables for target/victim type and target subtype, attacks involving “business” and more specifically “entertainment/cultural/stadium/casino” were identified. Attacks against performing arts venues were then identified using the search terms “theater,” “theatre,” “auditorium,” “center,” “hall,” “house,” “concert,” “music,” “opera,” “cinema,” and “movie.” Finally, two authors (SYL and GNJ) reviewed each attack including free-text variables for specific target information to confirm the appropriateness of all entries included in the analysis, selecting preferentially for attacks against venues where the primary focus of the audience was to view a performance. If consensus could not be reached regarding inclusion or exclusion of an entry, a third author reviewed the entry to resolve any discrepancy. Nightclubs, dance halls, and other social venues where watching a performance may not be the sole or primary focus of the visiting public were excluded. Variables analyzed included date of incident, country of incident, method of attack, and number of victims killed or wounded. A variable classifying the type of performing arts venue was created based on the free-text variable for specific target information mentioned before.

Data were analyzed using R (version 3.6.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria).3 Categorical variables were reported using frequencies (n [%]) and continuous variables using median and interquartile range (IQR). A subgroup analysis of attacks in the highest IQR for number of victims killed and/or wounded was also performed. This study was determined to be exempt from review by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Research Protection Office (St. Louis, Missouri USA).

Results

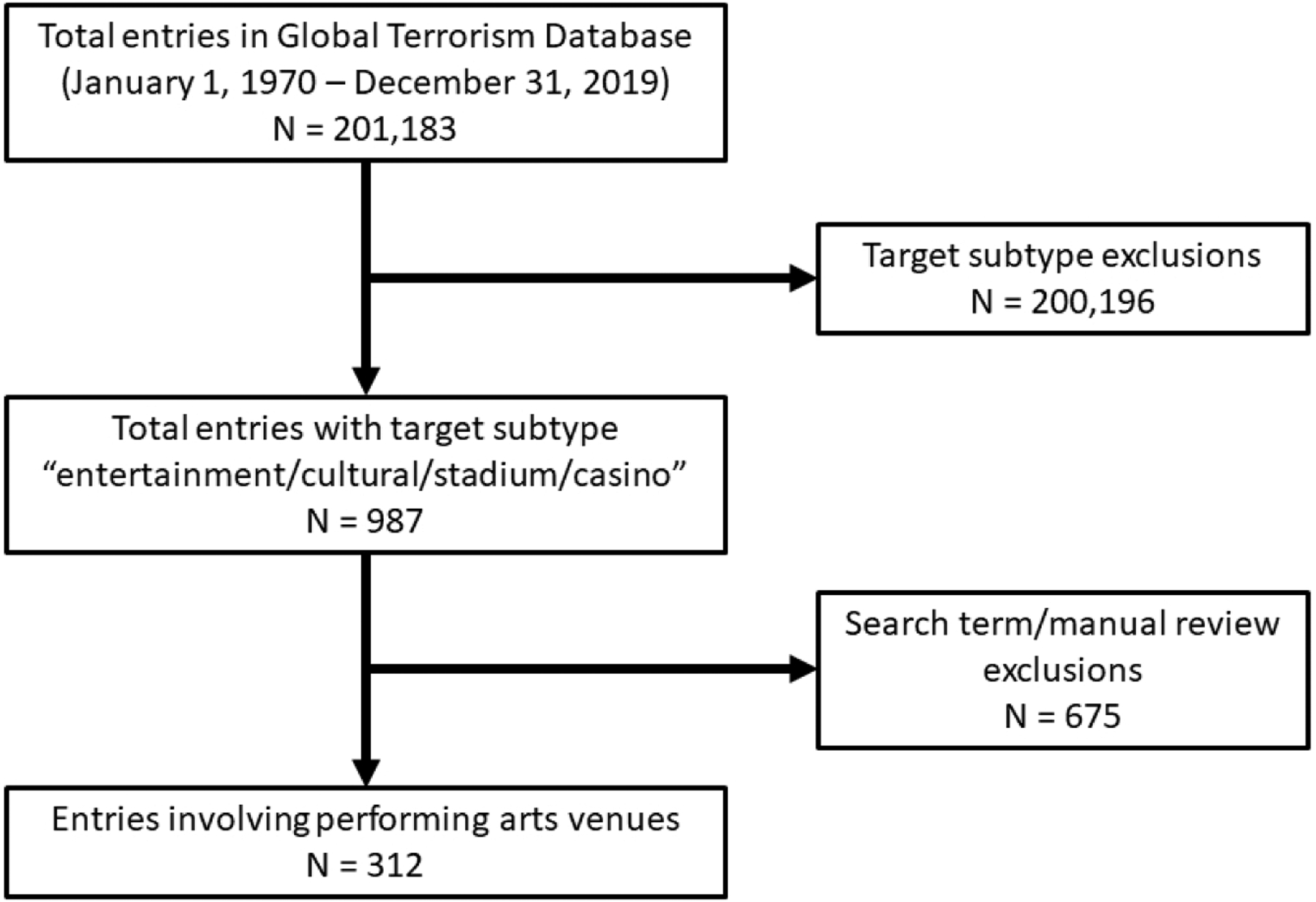

A total of 201,183 entries involving intentional global incidents were reported in the GTD from January 1, 1970 through December 31, 2019. Of those, 987 entries were identified by the pre-coded target subtype variable for “entertainment/cultural/stadium/casino” during this time period. Of these, 312 terrorist attacks targeting performing arts venues were included in the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Flow Diagram for Inclusion/Exclusion of Entries from the Global Terrorism Database.

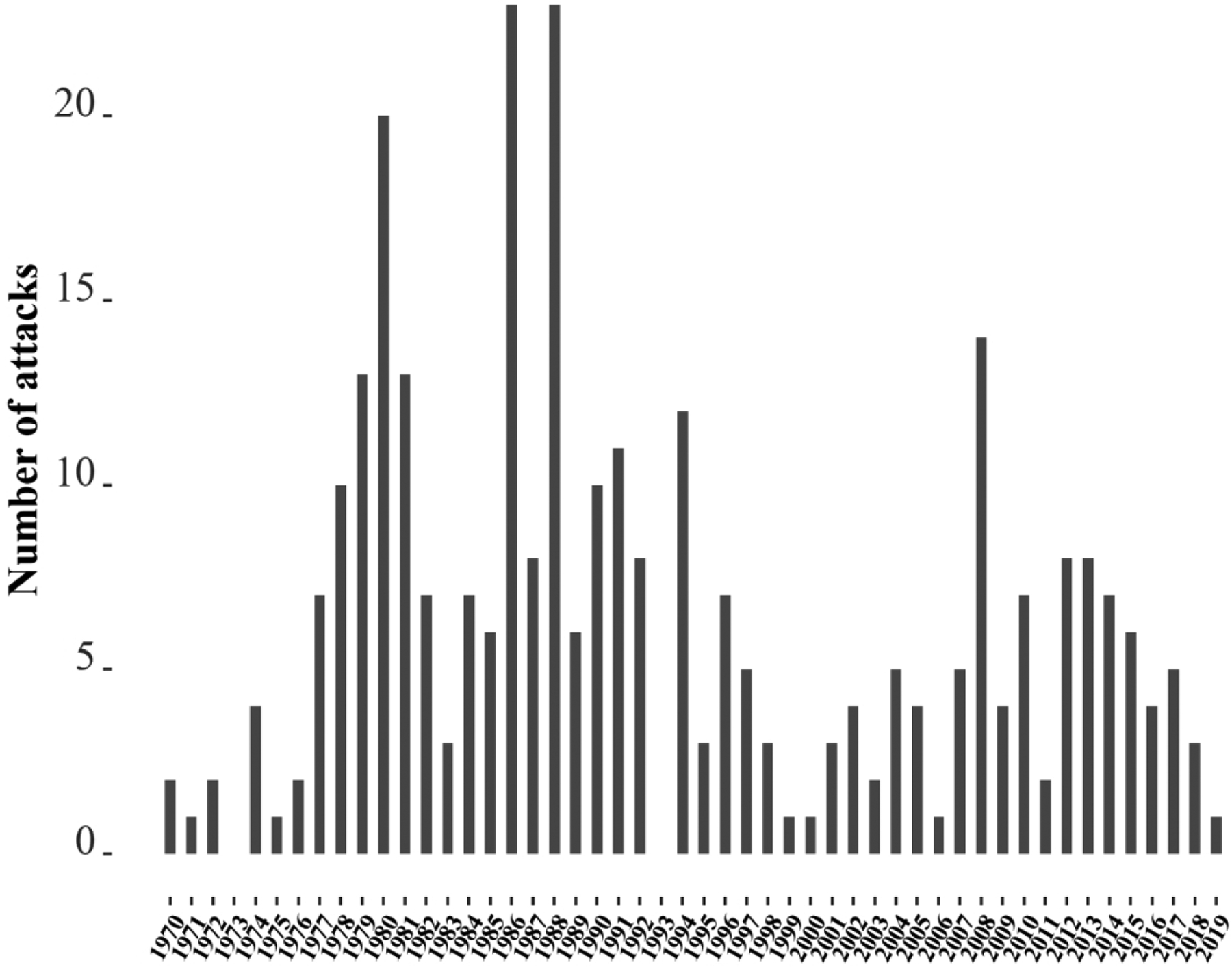

The greatest number of attacks against performing arts venues was 23 in 1986 and 1988, followed by 20 in 1980, 14 in 2008, and 13 in 1979 and 1981 (Figure 2). Two-hundred and nine (67.0%) attacks involved venues described as cinemas or movie theaters (Table 1). Eighty (25.6%) attacks involved theaters without further detail regarding whether these venues were for film viewing or live performances. Twenty-three (7.4%) attacks specifically targeted live music performance venues including concert halls, opera houses, music festivals, and outdoor spaces. The highest number of attacks occurred in India (50), Pakistan (28), Peru (21), the Philippines (21), the United States (18), and Italy (15). Attacks on performing arts venues were carried out in 49 countries.

Figure 2.

Number of Terrorist Attacks per Year Against Performing Arts Venues.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Terrorist Attacks Against Performing Arts Venues

| Characteristics, no. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Performance Venue Type | |

| Cinema or Movie Theater | 209 (67.0) |

| Theater, Unspecified | 80 (25.6) |

| Music Venue (eg, concert hall, opera house, outdoor spaces) | 23 (7.4) |

| Region | |

| South Asia | 88 (28.2) |

| Middle East & North Africa | 49 (15.7) |

| South America | 42 (13.5) |

| Western Europe | 38 (12.2) |

| Southeast Asia | 31 (10.0) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 26 (8.3) |

| North America | 18 (5.8) |

| Central America & Caribbean | 12 (3.8) |

| Eastern Europe | 4 (1.3) |

| East Asia | 3 (1.0) |

| Central Asia | 1 (0.3) |

| Australasia & Oceania | 0 (0.0) |

| Attack Typea | |

| Bombing/Explosion | 234 (75.0) |

| Facility/Infrastructure Attack | 50 (16.0) |

| Armed Assault | 17 (5.4) |

| Hostage Taking (barricade incident) | 5 (1.6) |

| Assassination | 3 (1.0) |

| Unknown | 3 (1.0) |

| Hostage Taking (kidnapping) | 1 (0.3) |

| Unarmed Assault | 1 (0.3) |

| Weapon Type Used in Attackb | |

| Explosives | 234 (75.0)c |

| Incendiary | 50 (16.0)d |

| Firearms | 19 (6.1) |

| Unknown | 10 (3.2) |

| Melee | 2 (0.6%)e |

| Other | 2 (0.6%)f |

| Chemical | 1 (0.3)g |

| Suicide Attack | 7 (2.2) |

| Victims, Number (median [IQR]) | |

| Killed, Total | 1,307 (0 [0–2]) |

| Cinema or Movie Theater | 876 (0 [0–2]) |

| Theater, Unspecified | 47 (0 [0–0]) |

| Music Venue (eg, concert hall, opera house, outdoor spaces) | 384 (1 [0–6.5]) |

| Wounded, Total | 4,201 (1 [0–10]) |

| Cinema or Movie Theater | 2,395 (1.5 [0–13]) |

| Theater, Unspecified | 333 (0 [0–4]) |

| Music Venue (eg, concert hall, opera house, outdoor spaces) | 1,473 (4 [0–34.8]) |

In 2 (0.6%) attacks, more than 1 attack type was reported. 1 combined bombing/explosion with armed assault; 1 combined bombing/explosion with hostage taking (barricade incident).

In 6 (1.9%) attacks, more than 1 weapon type was used. 5 combined explosives with firearms; 1 combined explosives with incendiary.

Unknown explosive type (157), grenade (31), other explosive (13), time fuse (10), dynamite/TNT (7), remote trigger (6), vehicle (6), suicide (5), projectile (4), pipe bomb (2), landmine (1) were used in 234 attacks involving explosives. 8 attacks combined use of 2 explosive types.

Unspecified incendiary (42), arson/fire (3), Molotov cocktail/petrol bomb (3), and gasoline/alcohol (2) were used in 50 attacks involving an incendiary weapon.

Knife or other sharp object.

Smoke bomb (1) and smoke grenade (1).

Tear gas (1).

A bombing or explosion was involved in 234 (75.0%) attacks, followed by damage to a facility or infrastructure (excluding the use of an explosive) in 50 (16.0%) attacks, armed assault in 17 (5.4%) attacks, hostage taking involving a barricade incident in five (1.6%) attacks, and targeted assassination in three (1.0%) attacks. Perpetrators used explosives in 234 (75.0%) attacks, incendiary weapons in 50 (16.0%) attacks, firearms in 19 (6.1%) attacks, unknown weapons in 10 (3.2%) attacks, melee weapons in two (0.6%) attacks, other weapons in two (0.6%) attacks, and a chemical agent in one (0.3%) attack. Further stratification on the most common weapon types demonstrated that explosives were used in 156 (74.6%) attacks against cinemas and movie theaters, 65 (81.3%) attacks against unspecified theaters, and 13 (56.5%) attacks against music venues. Incendiary weapons were used in 35 (16.7%) attacks against cinemas and movie theaters, 13 (16.3%) attacks against unspecified theaters, and two (8.7%) attacks against music venues. Firearms were used in 11 (5.3%) attacks against cinemas and movie theaters, three (3.8%) attacks against unspecified theaters, and five (21.7%) attacks against music venues.

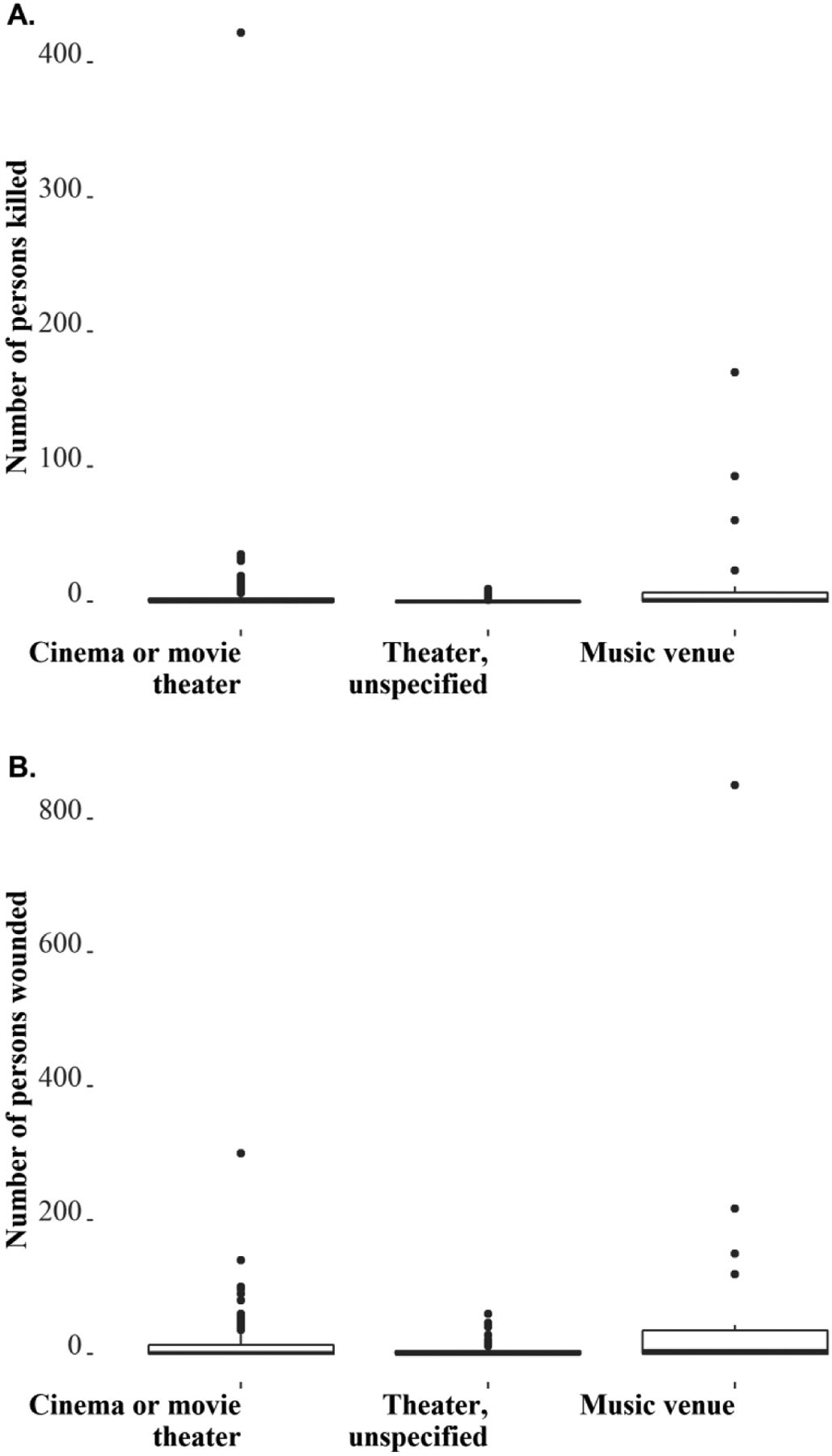

In total, 1,307 persons (median = 0; interquartile range [IQR]: 0–2) died and 4,201 persons (median = 1; IQR: 0–10) were wounded in attacks against performing art venues from 1970 through 2019. Attacks involving cinemas or movie theaters resulted in 876 deaths and 2,395 wounded, while those involving unspecified theaters resulted in 47 deaths and 333 wounded. Attacks targeting music venues resulted in 384 deaths and 1,473 wounded (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(A) Number of Persons Killed or (B) Wounded by Terrorist Attacks Against Performing Arts Venues by Venue Type, Shown in Boxplots.

Note: Boxes and horizontal bars denote interquartile range (IQR) and median. Whisker endpoints equal to the maximum and minimum values below or above the median.

Ninety-five attacks fell within the highest quartile for number of victims killed or wounded (>two killed and/or >ten wounded). Of these attacks, 71 (74.7%) involved cinemas or movie theaters, 12 (12.6%) involved unspecified theaters, and 12 (12.6%) music venues. Eighty-three (87.4%) involved explosives, seven (7.4%) involved firearms, three (3.2%) involved incendiary methods, two (2.1%) involved an unknown modality, one (1.1%) involved melee, and one (1.1%) involved a chemical. Two (2.1%) attacks combined use of explosives with firearms.

Discussion

In a retrospective analysis of 312 terrorist attacks against performing arts venues world-wide from 1970 through 2019, two-thirds involved cinemas and movie theaters. Another one-quarter targeted theaters without distinction of whether cinematic or live performances were presented in those spaces. Twenty-three (7.4%) attacks involved live music performance venues. Overall, the most frequent weapons types employed by attackers were explosives, incendiary weapons, and/or firearms. Explosives and incendiary weapons were more frequently used in attacks against cinemas, movie theaters, and unspecific theaters compared to music venues. While infrequent, firearm use was greater in attacks against music venues. Although most terrorist attacks against performing arts venues resulted in few if any casualties, a subset of attacks contributed disproportionately high numbers of fatalities and wounded.

With an estimated 200,000 cinema screens world-wide, 40,000 of which can be found in the United States alone, cinemas and movie theaters provide inexpensive and widely accessible entertainment to audiences.4 Attacks against cinemas and movie theaters accounted for 67.0% of all fatalities and 57.0% of those wounded in attacks against performing arts venues identified in this analysis of the GTD. Ranging from small clubs to traditional concert halls and opera houses to large amphitheaters and multi-use outdoor spaces, the number of music venues world-wide can be more challenging to quantify. Despite representing a small percentage of terrorist attacks against performing arts venues, attacks involving music venues were responsible for 29.4% of fatalities and 35.0% of those wounded. The high number of deaths and non-fatal injuries incurred during these attacks may be due in part to the large audiences many can accommodate and which limited run live performances are likely to attract. The wide variation in casualties associated with attacks against performing arts venues may also depend upon the time and location of the attack, types of weapons used, and overall objective of the perpetrators (eg, to intimidate businesses and patrons, physically damage a venue to prevent further performances, or intentionally inflict loss of life or limb).

In a subgroup analysis of attacks against performing arts venues falling within the highest quartile for casualties inflicted (>two killed and/or >ten wounded), 87.4% involved the use of explosives. The detonation of an improvised explosive device by a suicide bomber at the Manchester Arena as attendees were leaving an Ariana Grande concert on May 22, 2017 resulted in 23 deaths (20 at the scene, including the attacker) and at least 119 wounded. This indoor venue had a capacity to seat up to 21,000 people and the explosion occurred in the entrance foyer where parents were waiting for young audience members at the end of the performance. Among 153 patients (109 adults, 44 children) presenting to emergency departments following the attack with data in the National Health Service (NHS; United Kingdom) England Trauma Audit and Research Network (TARN) registry, the median Injury Severity Score (ISS) was one (IQR 1–10); 30 (20%) had moderate injuries (ISS 9–15), and 19 (12%) had severe injuries (ISS>15).5 Bomb blast and accompanying high-energy shrapnel dispersion resulted in major life-threatening injuries (Abbreviated Injury Scale ≥3), predominantly involving the extremities and/or chest; notably, the proportion of major injuries involving the head and chest was greater in children compared to adults. The use of explosives in terrorist attacks has remained common world-wide, with suicide bombings increasingly employed due to their lethality and ability to inflict not only significant physical but psychological harm.6,7

Firearms were used in 7.4% of attacks against performing arts venues ranked in the highest quartile for casualties in the GTD. The complex coordinated terrorist attacks of November 13, 2015 in Paris utilized explosives and firearms at multiple locations throughout the city. At the Bataclan concert hall, an indoor venue with a capacity to accommodate up to 1,500 people, three perpetrators wearing improvised explosive devices and armed with assault weapons gained entry during a performance by the rock band “Eagles of Death Metal,” firing on attendees and taking hostages. In the course of the law enforcement response, two of the improvised explosive devices worn by the attackers detonated. The attack at the Bataclan alone resulted in 93 deaths (including the three attackers) and at least 217 wounded. In an analysis of 337 patients injured and admitted to 16 civilian and two military hospitals after the Paris terrorist attacks, 286 (85%) sustained gunshot wounds and 51 (15%) blast injuries; 196 (58%) were wounded at the Bataclan.8 The median ISS for the entire cohort was two (IQR 1–9), with 49 (15%) having sustained severe injuries (ISS>15). Those with gunshot wounds had more severe injuries and were more likely to need blood transfusion and/or emergency surgery compared to those injured by an explosion. In several small case series reported from individual trauma centers and hospitals, extremity soft tissue wounds and open fractures were the most common injuries; fewer patients presented with severe chest, abdominal, or head trauma.9–11 Among 25 patients with penetrating chest trauma sustained during the attacks, 80% were due to gunshot wounds; intrathoracic injuries included hemothorax (80%), pulmonary contusion (80%), pneumothorax (60%), and pulmonary laceration (54%).12 A mass shooting on the night of October 1, 2017 at the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas, Nevada resulted in 60 deaths and at least 850 wounded. Taking place at the Las Vegas Village, a 15-acre outdoor performance venue on the Strip, the festival attracted over 22,000 attendees the day of the attack. The attacker fired assault weapons from the 32nd floor of a hotel overlooking the venue during the closing performance of country music singer Jason Aldean; 31 people died at the scene and 22 were dead on arrival to receiving hospitals.13 In an analysis of blood component usage (red blood cells, plasma, and platelets) at hospitals responsible for treating 519 persons injured in the attack, 185 were admitted and nearly 500 blood components were transfused during the first 24 hours of care.13 While firearms have not been employed as frequently as explosives in terrorist attacks world-wide, the risk of fatal injury associated with their use has been higher than other weapon types in a prior analysis of the GTD.14

Incendiary methods accounted for only 3.2% of attacks against performing arts venues in the highest quartile of casualties analyzed. Most notably, in 1978, an incendiary attack against the Cinema Rex in Abadan, Iran resulted in over 400 deaths at a screening of the film “The Deer.” According to news reports, the theater was doused in gasoline and set on fire; patrons succumbed to traumatic injuries from trampling, thermal injury, and asphyxiation.15 Emergency exits were reportedly locked preventing egress and further complicating rescue. Across all attacks against performing arts venues studied, incendiary methods were used more frequently in attacks against cinemas, movie theaters, and unspecified theaters than music venues. Apart from the attack against the Cinema Rex, few if any persons were reported killed or wounded due to use of an incendiary weapon against a performing arts venue in the GTD. It is possible this method of attack may be preferred when the objective is to damage property or intimidate the public rather than inflict casualties; however, the intent of a terrorist attack is not assessed in the GTD.

Characterization of the most common methods of terrorist attack against performing arts venues and the likely injuries to be encountered can better inform medical disaster preparedness and prehospital emergency care and reduce preventable death. Originally developed in 2013, the Hartford Consensus proposed the THREAT framework to improve survival of victims of mass shootings: Threat suppression by law enforcement is tantamount to stopping further killing, external Hemorrhage control (eg, rapid tourniquet application, hemostatic dressing), Rapid Extrication to safety, Assessment by medical providers, and Transport to definitive care represent potentially integrated responses across law enforcement, fire/rescue, and Emergency Medical Services.16 Massive hemorrhage from an extremity injury, whether due to an explosion or gunshot wound, was considered a significant source of preventable death on the modern battlefield that was significantly reduced through the use of tourniquets during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.17 These lessons can likely be extrapolated to terrorist attacks against civilian targets given the similarity in weapons employed and translated safely to civilian first responders rendering prehospital care.18 However, specific data are limited and effectiveness has not been well-established. Equipping public spaces such as entertainment venues with point-of-injury bleeding control kits has been proposed but presents its own challenges with respect to appropriate bystander training, strategic placement of kits, cost, and maintenance.19,20

Proactive communication and collaboration between public safety, health care systems, and performing arts venues can lay the groundwork to optimize survival outcomes for victims of a terrorist attack or other mass-casualty incident. A dedicated event disaster/mass-causality incident plan should be established in advance of any large gathering and should be familiar to all emergency resources staged at the venue, responding agencies, as well as definitive care receiving centers. Identifying several potential sites for casualty collection and triage on-scene or near the venue can expedite prehospital emergency care and streamline evacuation to definitive care. Emergency departments and hospitals should familiarize themselves with the performance schedules of local venues. When a large crowd is anticipated at an event, emergency departments likely to receive casualties from performing arts venues after an attack should establish and review contingency plans to manage patient surge and ensure adequate health care resources, personnel, and patient flow processes as part of on-going emergency preparedness efforts. Indeed, mass-casualty events often involve patterns of self-referral, both on foot and in private vehicles, and hospitals must be prepared for a rapid influx of casualties in the wake of a terrorist attack.

Limitations

Strengths of this study include the size and scope of the GTD, considered the most comprehensive unclassified database of terrorist attacks world-wide available to researchers. However, source data for the GTD originate from publicly-available materials including media reports as well as existing datasets, secondary sources (eg, books, journals), and legal documents, but not medical records. Additionally, the GTD does not include foiled or failed plots, attacks in which violence is threatened as a means of coercion, incidents reported from non-high-quality sources, or attacks in conflict zones where the combatant may be “national” and fall out of their inclusion criteria. Access to reliable source materials and efficiency of workflows have varied over the long history of the GTD. All of these limitations may mean that the true incidence and human toll of terrorist attacks targeting performing arts venues could be under-reported or misreported. The GTD likely under-reports the number of individuals killed or wounded; in many instances, these numbers are not known and so no numbers are reported. Finally, attacks where terrorism is a strong possibility but some uncertainty exists are included in the GTD and identified as such for incidents occurring after 1997. A clear association between an attack and terrorism can be difficult to establish. Of the 312 attacks included in this analysis, seven such incidents were identified, which could have impacted the findings, particularly with respect to the reported number of individuals killed or wounded. One of these incidents was the 2017 mass shooting at the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas, Nevada. These attacks were included in the study to provide a broader, more complete understanding of attacks against performing arts venues captured in the GTD.

Conclusion

While uncommon, terrorist attacks against performing arts venues have the potential to inflict mass casualties, particularly when explosives and firearms are used. An understanding of global trends and characteristics of past attacks can serve as a starting point for prehospital and emergency clinicians and performing arts venue leaders to assess risk, to anticipate injury patterns, and to identify best practices to reduce preventable deaths.

Conflicts of interest/disclosures:

SYL, LT, GAC, BJL, and GNJ have no conflicts of interest to report. SYL received support through the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital and the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences which is, in part, supported by the NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program (UL1TR002345).

Abbreviations:

- GTD

Global Terrorism Database

- ISS

Injury Severity Score

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

References

- 1.National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Response to Terrorism (START). University of Maryland. Global Terrorism Database (GTD). https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd. Accessed May 5, 2022.

- 2.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.R Core Team (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed May 5, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Institute for Statistics Database. http://data.uis.unesco.org/Index.aspx. Accessed May 5, 2022.

- 5.Dark P, Smith M, Ziman H, Carley S, Lecky F; Manchester Academic Health Science Centre. Healthcare system impacts of the 2017 Manchester Arena bombing: evidence from a national trauma registry patient case series and hospital performance data. Emerg Med J. 2021;38(10):746–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards DS, McMenemy L, Stapley SA, Patel HD, Clasper JC. 40 years of terrorist bombings - a meta-analysis of the casualty and injury profile. Injury. 2016;47(3):646–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tin D, Galehan J, Markovic V, Ciottone GR. Suicide bombing terrorism. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2021;36(6):664–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raux M, Carli P, Lapostolle F, et al. Analysis of the medical response to November 2015 Paris terrorist attacks: resource utilization according to the cause of injury. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(9):1231–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregory TM, Bihel T, Guigui P, et al. Terrorist attacks in Paris: surgical trauma experience in a referral center. Injury. 2016;47(10):2122–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbier O, Malgras B, Choufani C, Bouchard A, Ollat D, Versier G. Surgical support during the terrorist attacks in Paris, November 13, 2015: experience at Begin Military Teaching Hospital. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(6):1122–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Femy F, Follin A, Juvin P, Feral-Pierssens AL. Terrorist attacks in Paris: managing mass casualties in a remote trauma center. Eur J Emerg Med. 2019;26(4):289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boddaert G, Mordant P, Le Pimpec-Barthes F, et al. Surgical management of penetrating thoracic injuries during the Paris attacks on 13 November 2015. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;51(6):1195–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lozada MJ, Cai S, Li M, Davidson SL, Nix J, Ramsey G. The Las Vegas mass shooting: an analysis of blood component administration and blood bank donations. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86(1):128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tessler RA, Mooney SJ, Witt CE, et al. Use of firearms in terrorist attacks: differences between the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1865–1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Branigan W. Terrorists Kill 377 by Burning Theater in Iran. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1978/08/21/terrorists-kill-377-by-burning-theater-in-iran/2eb80ec8-123b-4d73-b351-870bc2a41f3f/. Accessed May 5, 2022.

- 16.Jacobs LM, Wade DS, McSwain NE, et al. The Hartford Consensus: THREAT, a medical disaster preparedness concept. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(5):947–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Seguin P, et al. Death on the battlefield (2001–2011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6 Suppl 5):S431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borgers F, Van Boxstael S, Sabbe M. Is tactical combat casualty care in terrorist attacks suitable for civilian first responders? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;91(4):e86–e92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goolsby C, Strauss-Riggs K, Rozenfeld M, et al. Equipping public spaces to facilitate rapid point-of-injury hemorrhage control after mass casualty. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(2):236–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agrawal P. Is the plural of anecdote data? Creating evidence-based policy for mass-casualty incidents. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(2):189–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]