Abstract

Oral cancer pain is attributed to release from cancers of mediators that sensitize and activate sensory neurons. Intraplantar injection of conditioned media (CM) from human tongue cancer cell line HSC-3 or OSC-20 evokes nociceptive behavior. By contrast, CM from non-cancer cell lines, DOK and HaCaT are non-nociceptive. Pain mediators are carried by extracellular vesicles (EVs) released from cancer cells. Depletion of EVs from cancer cell line CM reverses mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia. Conditioned media from non-nociceptive cell lines become nociceptive when reconstituted with HSC-3 EVs. We identified two miRNAs (hsa-miR-21-5p and hsa-miR-221-3p) present in increased abundance in EVs from HSC-3 and OSC-20 CM compared to HaCaT CM. The miRNA target genes suggest potential involvement in oral cancer pain of the toll like receptor 7 (TLR7) and 8 (TLR8) pathways, as well as signaling through interleukin 6 cytokine family signal transducer receptor (gp130, encoded by IL6ST) and colony stimulating factor receptor (G-CSFR, encoded by CSF3R), Janus kinase and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAK/STAT3). These studies confirm the recent discovery of the role of cancer EVs in pain and add to the repertoire of algesic and analgesic cancer pain mediators and pathways that contribute to oral cancer pain.

Keywords: extracellular vesicles, oral cancer, pain, oral cancer induced pain, miRNA, miR-21, miR-221

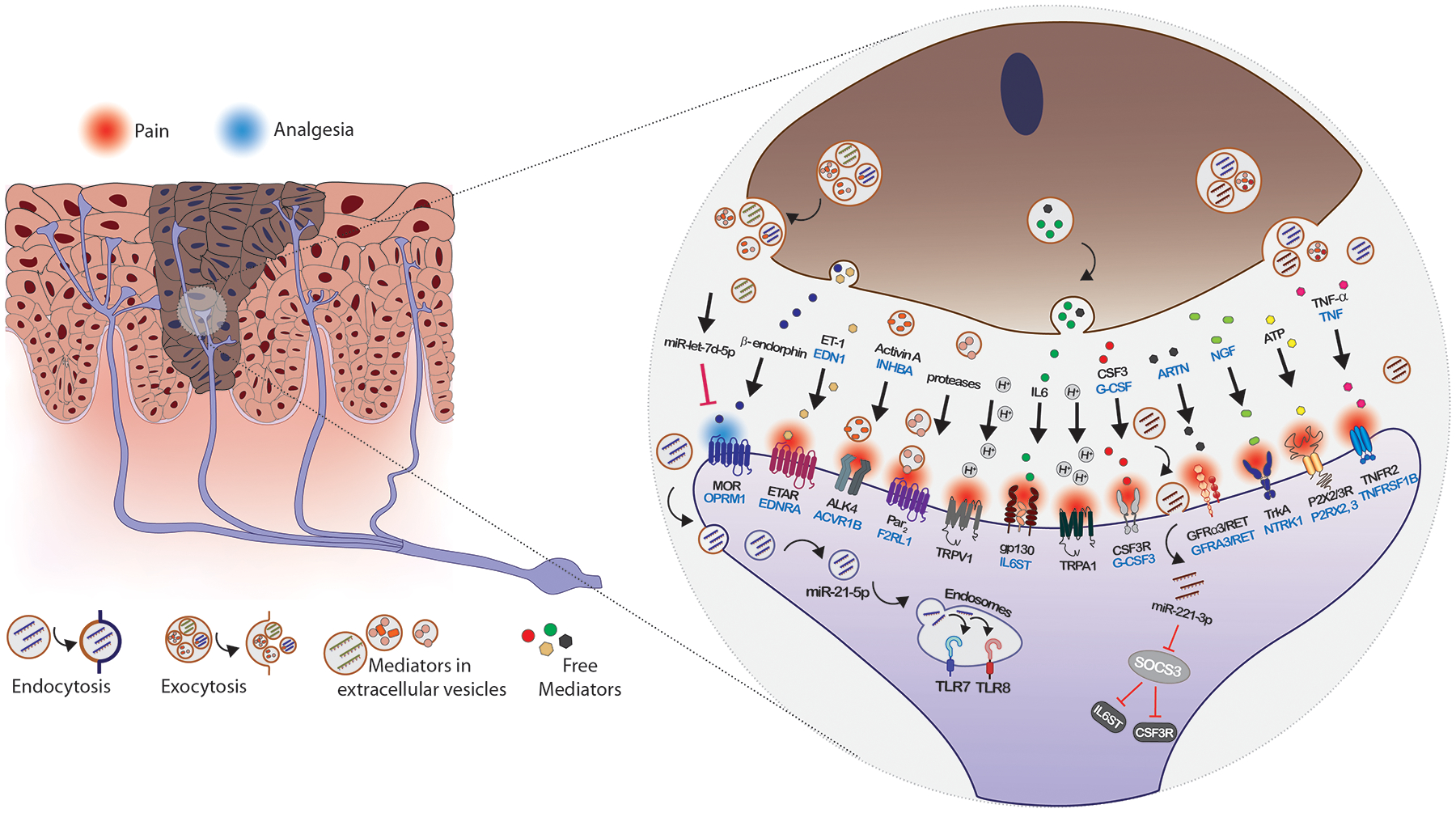

Graphical Abstract

Oral cancer patients suffer pain at the site of the cancer. Oral cancers release extracellular vesicles (EVs) carrying pain mediators. The EV protein and miRNA cargoes can contribute to oral cancer pain by direct ligand-receptor interactions or by modulating expression or activity of genes leading to increased activity of nociceptive pathways or reduced activity of analgesic pathways in neurons.

1. Introduction

Oral cancer, a member of the group of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs), generates more prevalent and more severe pain than all other cancers.[1] Despite the severity and clinical problem of oral cancer pain, the etiology remains unclear.

Oral cancer pain is initiated and maintained in the cancer microenvironment.[2–4] Oral cancer patients suffer from function related pain, i.e, when chewing, talking and eating.[5] Spontaneous pain levels are low. Pain is alleviated following complete surgical resection of the cancer, which suggests a peripheral mechanism is responsible for generating and maintaining the pain and argues against a central component or sensitization.[6] These observations support the current understanding that oral cancer pain is attributed to release of mediators from the cancer and microenvironment. On the one hand, the mediators sensitize or activate primary afferent sensory neurons that respond to nociceptive stimuli (nociceptors) and induce sprouting of sensory and sympathetic neurons into the microenvironment.[7–10] On the other hand, neuropeptides released from sensory neurons promote cancer.[10,11] Neuropeptides induce epidermal proliferation, angiogenesis, perineural invasion and transformation of stromal cells.[12–16] The mechanisms of reciprocal interaction between oral cancer cells and neurons, and how the interactions promote cancer and pain, are not known. There is a need to define the mechanisms by which oral cancers and neurons interact with each other and the efficacy of disrupting this interaction to treat oral cancer and associated pain.

Patients with regional/nodal metastasis (N+) oral cancer experience greater pain than patients without metastasis (N0).[5,17] Patient reported pain on the University of California San Francisco Oral Cancer Pain Questionnaire[5] has potential to identify the presence of metastasis prior to surgery to remove the cancer.[17] Proteins encoded by genes differentially expressed in N+ cancers from patients with high levels of pain, “pain and metastasis genes,” are enriched for functions in extracellular matrix organization and angiogenesis. These genes have oncogenic and neuronal functions. This set of genes overlaps with the meta-signature of the partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (p-EMT) program, also recently described as an independent predictor of lymph node metastasis in HNSCC.[18,19] Pain and metastasis genes have been identified as cargo of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in publicly available databases such as ExoCarta.[20] Depletion of EVs from cancer cell line conditioned media (CM) reversed CM-induced thermal and mechanical allodynia in a mouse model, implicating EVs in the transport of pain mediators.[17]

Extracellular vesicles carry proteins, nucleic acids and lipids and provide a means of communication between cells.[21] Cancers release elevated levels of EVs and the protein cargo of EVs is cancer type specific.[21,22] EVs released into the circulation and their cargo are potential biomarkers for cancer detection and diagnosis of cancer type.[22] Recent studies highlight EV heterogeneity.[23–25] Subpopulations of EVs and nanoparticles, collectively referred to as EVPs, differ in size and cargoes. Small EVs (sEVs) or exosomes (40–150 nm in diameter) are formed within the endosomal system as intralumenal vesicles of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and are released into the extracellular space when the MVBs fuse with the plasma membrane. Classic exosomes carry the exosomal markers CD63, CD9 and CD81, but these markers are absent from another group of similarly sized vesicles, non-classical exosomes.[24] Exosome cargo is enriched in proteins associated with signaling and transduction pathways. Large EVs, microvesicles (150–1000 nm in diameter) and oncomirs (1–10 μm in diameter) are formed by membrane budding. Annexin A1 is a specific marker of microvesicles.[24] Two types of non-membranous nanoparticles have recently been distinguished – exomeres (<50 nm in diameter) and supermeres, identified in the supernatant after ultracentrifugation to isolate exomeres.[25,26] Exomere cargo is enriched for proteins involved in metabolism, coagulation and glycan-mediated protein folding control.[26] Supermeres differ from exomeres in structure and functional properties. Supermeres are now known to be the subpopulation enriched in extracellular RNAs, including miRNAs previously reported in association with exosomes.[25]

MicroRNAs are small, 19–24 nucleotide long, non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression.[27] They bind to the 3’UTR of target mRNAs and inhibit translation or reduce mRNA stability.[27] MicroRNAs can also interact directly with proteins.[28,29] MicroRNAs are aberrantly expressed in cancer and act as oncogenes (oncomiRs) or tumor suppressors.[30,31] MicroRNAs released from cancer cells in EVs communicate with cells in the tumor microenvironment, to modulate the vasculature, stroma, immune infiltrate and nervous innervation.[32–34] Deregulated neuronal expression of specific miRNAs is reported in association with painful conditions, including neuropathic, inflammatory and cancer pain.[35–37] The role of miRNAs released in cancer cell EVs in cancer pain is not defined.

We extended our study of putative EV cancer pain mediators identified by differential gene expression in clinical samples to ask whether EVs from nociceptive oral cancer cells might also carry miRNA pain mediators. We compared EV miRNA cargo from oral cancer cell lines associated with pain and non-cancer cell lines. MicroRNAs enriched in cancer cell EVs have potential to modulate pain receptors and pain signaling pathways in neurons.

2. Results

2.1. Intraplantar injection of CM from oral cancer cell lines evokes nociceptive behavior in mice

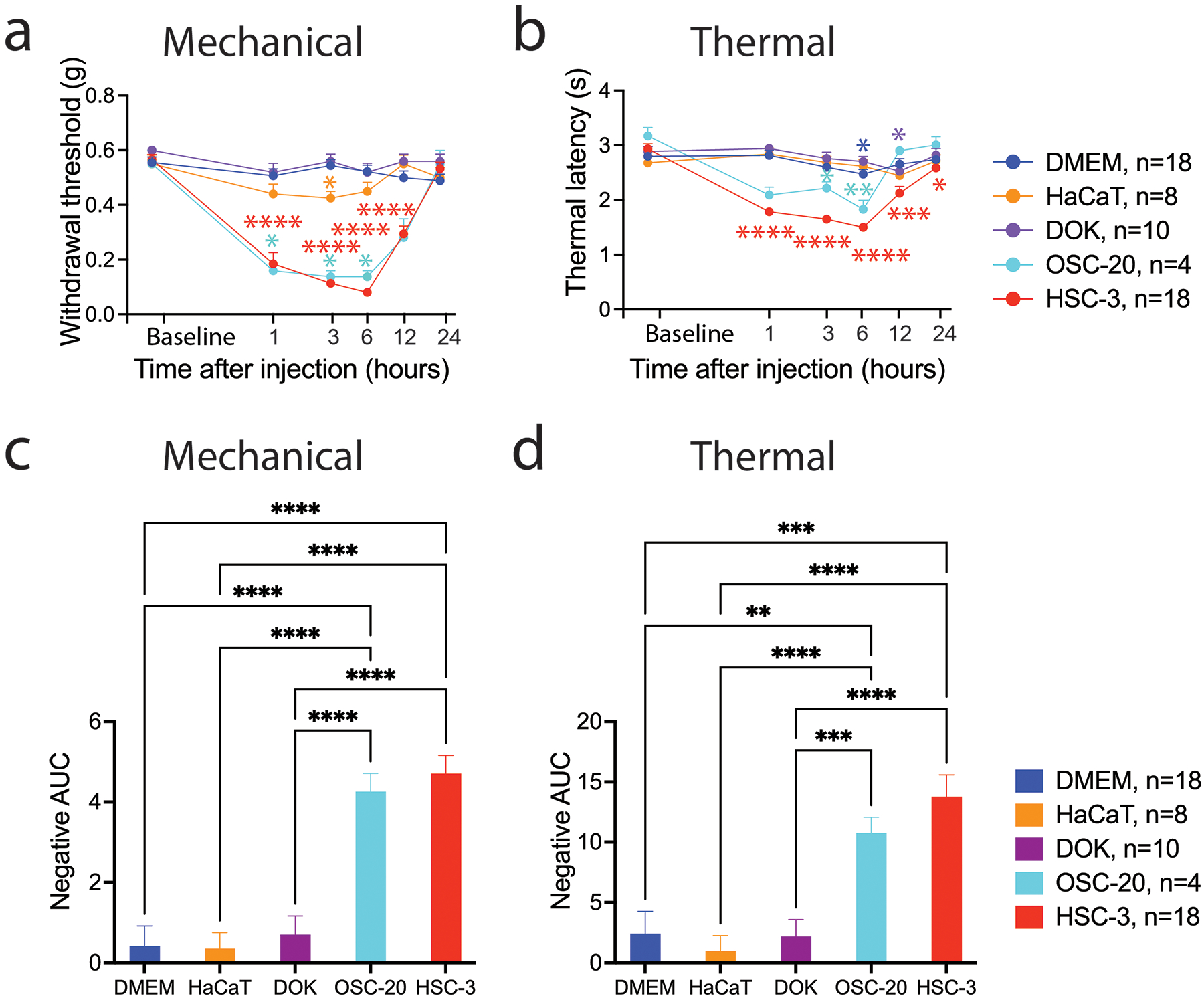

Injection of CM or compounds (e.g., proteins, lipids) into the rodent hind paw, followed by measurement of paw withdrawal threshold in response to a mechanical stimulus (von Frey fibers)[38] or latency of response to a thermal probe[39] are established assays for evoked nociception (the animal equivalent of pain).[40] We compared paw withdrawal in response to intraplantar injection of CM among two oral cancer cell lines and two non-cancer cell lines. The studied cancer cell lines included HSC-3 (RRID:CVCL_1288), a cell line established from a cervical metastasis of a tongue cancer in a 64 year old man and OSC-20 (RRID:CVCL_3087), established from a cervical metastasis of a tongue cancer in a 59 year old woman.[41] The non-cancer cell lines included, the spontaneously immortalized DOK (RRID:CVCL_1180) and HaCaT (RRID:CVCL_0038) cell lines.[42,43] DOK was established from the dysplasia at the margins of a hemiglossectomy specimen as part of a resection for tongue cancer in a 57 year old man, who was a heavy smoker. The DOK cells harbor highly rearranged genomes and display a partially transformed phenotype – DOK does not grow in soft agar and is non-tumorigenic. The HaCaT cell line was established from tissue excised from a site distant from a melanoma on the upper back (not extensively sun-exposed skin) of a 62 year old man. The HaCaT cell line is aneuploid, fails to form tumors in nude mice, and retains the capacity to differentiate in organotypic culture. Mechanical allodynia was observed in response to the oral cancer cell line CM at 1, 3, 6 and 12 hours after injection, but not in response to DMEM and non-cancer cell line CM (Figure 1a and 1c, Table S1, Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). A decrease in the paw withdrawal latency in response to a thermal stimulus was observed following intraplantar injection of the HSC-3 cancer cell line CM (Figure 1b and 1d, Table S2, Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). The response was greater than that of non-cancer cell line CM at 1, 3, 6 and 12 hours after injection. Intraplantar injection of OSC-20 CM elicited a more modest response (Figure 1c and 1d, Table S2, Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Significant reduction in thermal latency relative to baseline was also observed in response to DMEM and DOK at 6 and 12 hours after injection, respectively (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Intraplantar injection of conditioned media from oral cancer cell lines evokes nociceptive behavior in mice. The allodynic effect of samples injected into the right hind paw was measured by assaying induced mechanical nociception (a) and thermal hyperalgesia (b) at baseline (before injection) and at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 hours after injection. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 cell line CM versus cell line baseline indicated by color, Two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Cell line CM induced nociception measured in response to mechanical (c) and thermal (d) stimuli is summarized as the negative area under the curve (AUC) measured up to 12 hours after injection relative to baseline. **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, Brown-Forsythe and Welch ANOVA tests with Dunnett T3 multiple comparisons test.

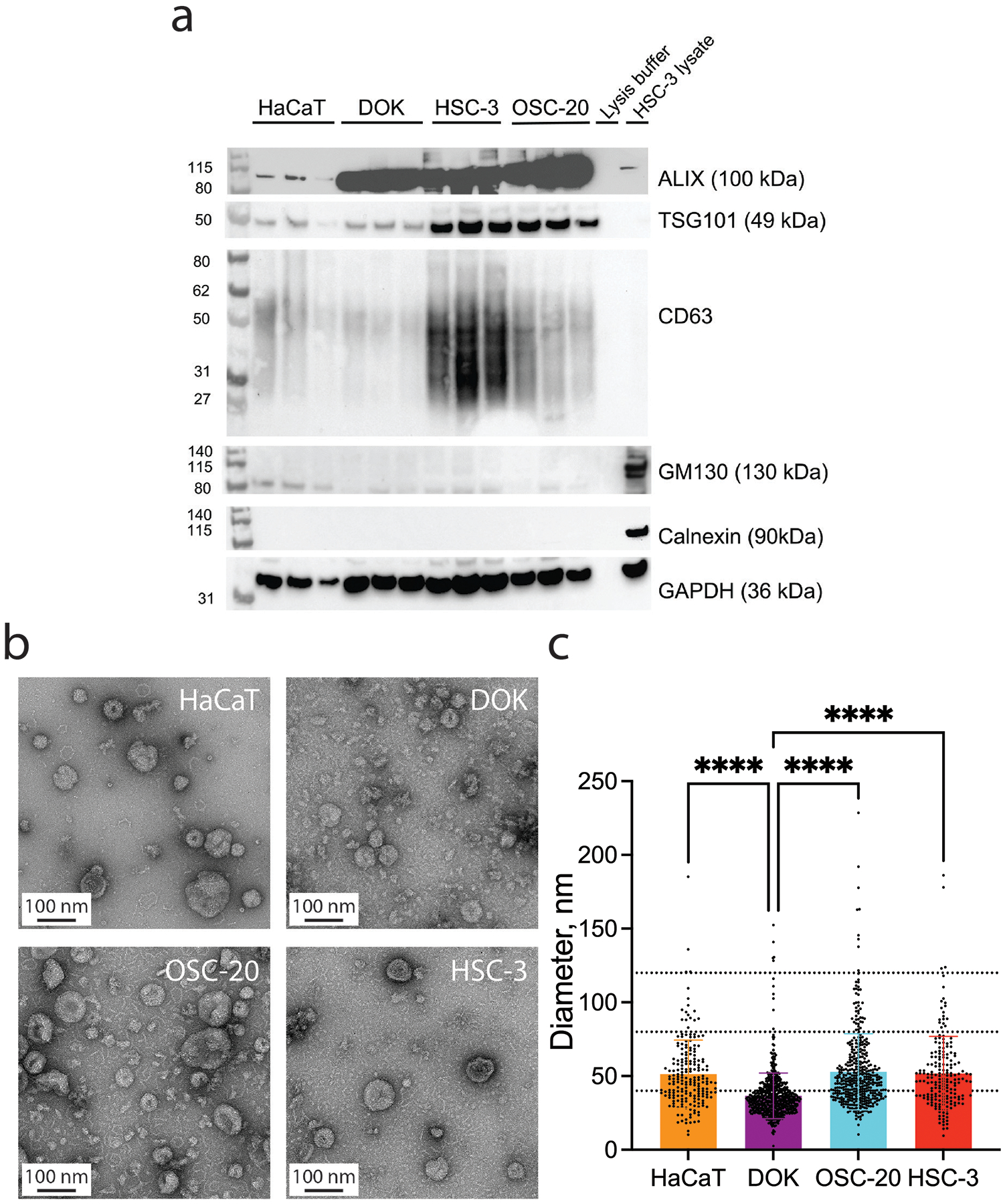

2.2. Oral cancer cells release EVs with the characteristics of exosomes

Extracellular vesicles were isolated from HaCaT, DOK, OSC-20 and HSC-3 cell lines by ultracentrifugation. The EV preparations were enriched for “exosome” markers CD63, ALIX and TSG101, although expression levels varied among the cell lines. Cytoplasmic proteins GM130 and calnexin were not detected in the EV preparations, but were present in the HSC-3 cell lysate control (Figure 2a). The diameters of the EVs were measured from transmission electron micrographs taken at 92,000× magnification (Figure 2b and 2c). The measured diameters of the EVs from the dysplasia cell line DOK were smaller than the diameters of the two oral cancer cell lines and the non-tumorigenic skin keratinocyte line HaCaT. Recent studies have highlighted the different subtypes of EVs, distinguished by size and nature of the EV cargoes. Further studies will be required to understand how the smaller DOK EVs differ from the EVs of the other cell lines.

Figure 2.

Oral cancer cells release EVs with the characteristics of exosomes. (a) Isolated EVs express exosome endocytic marker proteins TSG101 and ALIX, and tetraspanin, CD63. Calnexin (CANX, endoplasmic reticulum marker) and GM130 (cis-Golgi network marker) were not detected. (b) Representative transmission electron micrographs of EVs isolated from HaCaT, DOK, OSC-20 and HSC-3 conditioned media. (c) The EVs from DOK cells are significantly smaller than the EVs from HaCaT, OSC-20 and HSC-3 cells. Diameters of EVs (mean ± SD) measured from TEM images taken at 92,000× magnification (10–12 fields per sample). Dotted lines indicate y-axis values = 40, 80 and 120 nm. Diameters of EVs from the cell lines (mean ± SD). HaCaT: 51.31±23.06 nm, n=201; DOK: 36.53±15.49 nm, n=615; OSC-20: 52.84±25.79 nm, n=427; HSC-3: 51.68±25.18 nm, n=193 (F(3,1432) = 62.77, ****p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Data independently replicated.

2.3. Depletion of EVs reverses mechanical allodynia and thermal hypersensitivity

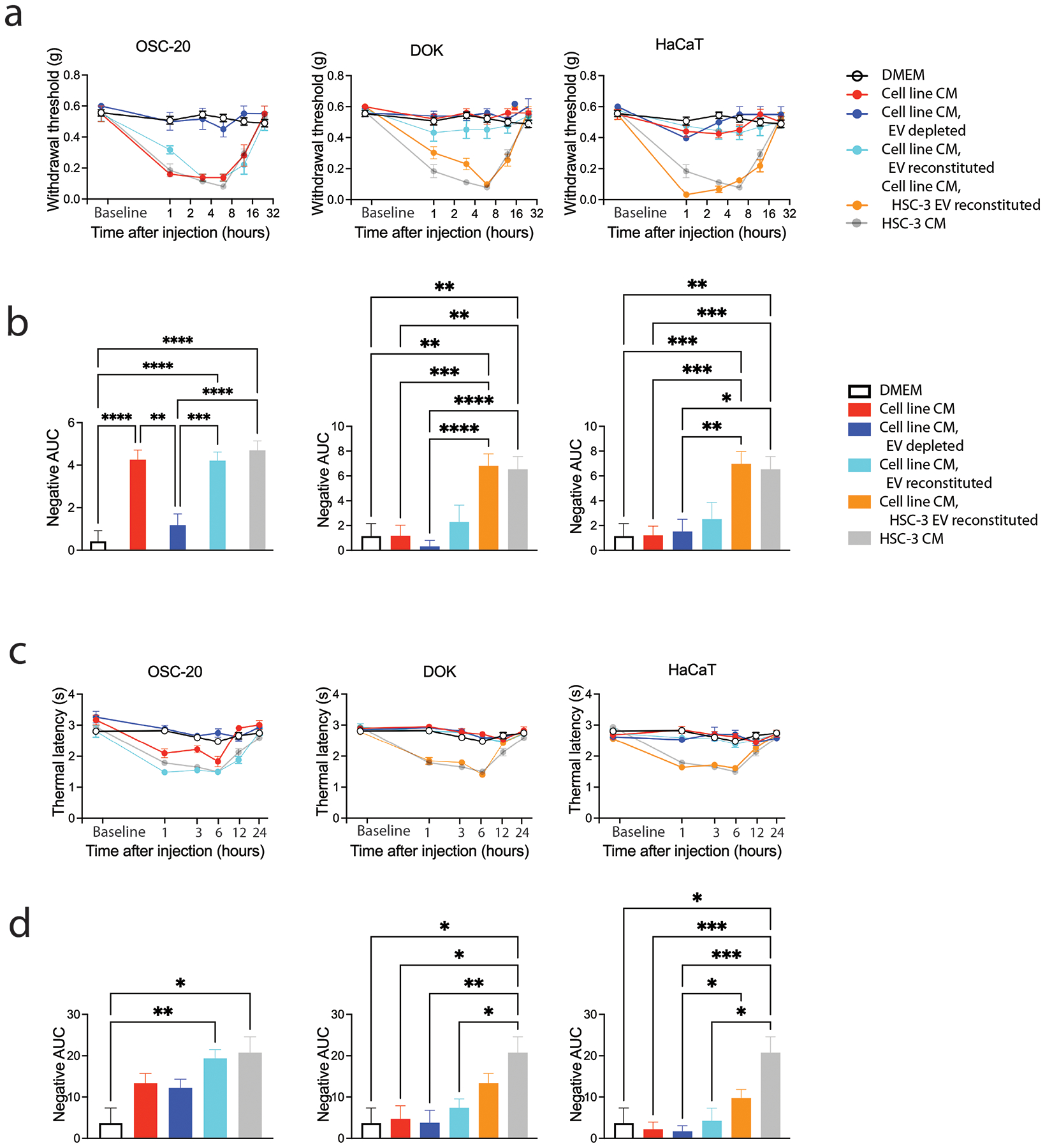

We previously reported that HSC-3 CM depleted of EVs does not induce mechanical or thermal hypersensitivity.[17] To assess whether nociceptive behavior evoked by the OSC-20 cancer cell line CM might be attributed to EVs released into the CM, we fractionated the CM by size exclusion chromatography to obtain EV fractions (EV+) and fractions devoid of EVs (EV−) (Figure S1). We injected DMEM, CM, CM depleted of EVs (EV−), and CM depleted of EVs and reconstituted with EVs (EV− & EV+) into the hind paw of mice and performed paw withdrawal assays (Figure 3). Depletion of EVs from the OSC-20 CM alleviated mechanical allodynia and thermal hypersensitivity. Paw withdrawal threshold and thermal latency did not differ from that of DMEM alone (Table S3 and S4, two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Nociceptive responses to mechanical and thermal stimulation were restored by reconstitution of the OSC-20 EV depleted media with the OSC-20 EV fraction. Withdrawal thresholds in response to intraplantar injection of OSC-20, EV reconstituted OSC-20 and HSC-3 CM were similar over the 24-hour test period (Figure 3a and 3b, Table S3 and S4, two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). By contrast, whereas HaCaT and DOK CM did not induce nociceptive behavior in response to mechanical or thermal stimuli, when HaCaT or DOK EV depleted CM was reconstituted with HSC-3 EVs, paw withdrawal threshold and thermal latency were reduced (Figure 3, Table S3 and S4, two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). The responses to HSC-3 and HSC-3 reconstituted CM were similar over the 1- to 12-hour time period of testing for mechanical sensitivity (Figure 3a, Table S3, two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Thermal sensitivity induced by reconstitution of DOK and HaCaT CM with HSC-3 EVs measured over the 1- to 6-hour period was similar to HSC-3 (Figure 3c, Table S4, Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). These differences in sensitivity in response to intraplantar injection of non-nociceptive CM reconstituted with HSC-3 EVs are reflected in the negative AUC (Figure 3b and 3d).

Figure 3.

Depletion of EVs from cancer cell line CM reverses mechanical allodynia and thermal hypersensitivity. The allodynic effect of samples injected into the right hind paw was measured by assaying induced mechanical nociception (a and b) and thermal hyperalgesia (c and d) at baseline (before injection) and at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 hours after injection (group sizes are given in Table S5). Cell line CM induced nociception measured in response to mechanical (c) and thermal (d) stimuli is summarized as the negative area under the curve (AUC) measured up to 12 hours after injection relative to baseline. *p<0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, Brown-Forsythe and Welch ANOVA tests with Dunnett T3 multiple comparisons test.

2.4. Cancer pain mediators in EV cargo

EVs carry lipids nucleic acids and proteins and these cargoes could sensitize nociceptors. We reported previously the presence in EVs of genes associated with pain in human cancer.[17] We confirmed expression of MMP1 in HSC-3 EVs grown under normoxia and absence of MMP1 in EVs released from OSC-20 grown under normoxia (Figure S2). We did not detect MMP1 in EVs from HaCaT and DOK. By contrast, we detected legumain (LGMN), a lysosomal asparagine endopeptidase in the EV preparations from nociceptive and non-nociceptive cell lines. LGMN has been reported to be present in EVs,[44,45] to promote metastasis in cancers[46] and contribute to cancer induced bone pain and oral cancer pain.[47,48] In this study, we asked whether we could identify candidate miRNA pain mediators by analysis of their differential presence in EVs from oral cancer cell line CM that induce nociception (HSC-3, OSC-20) compared to HaCaT that does not induce nociception.

2.4.1. Genome-wide profiling of miRNAs in EVs using the NanoString nCounter miRNA platform.

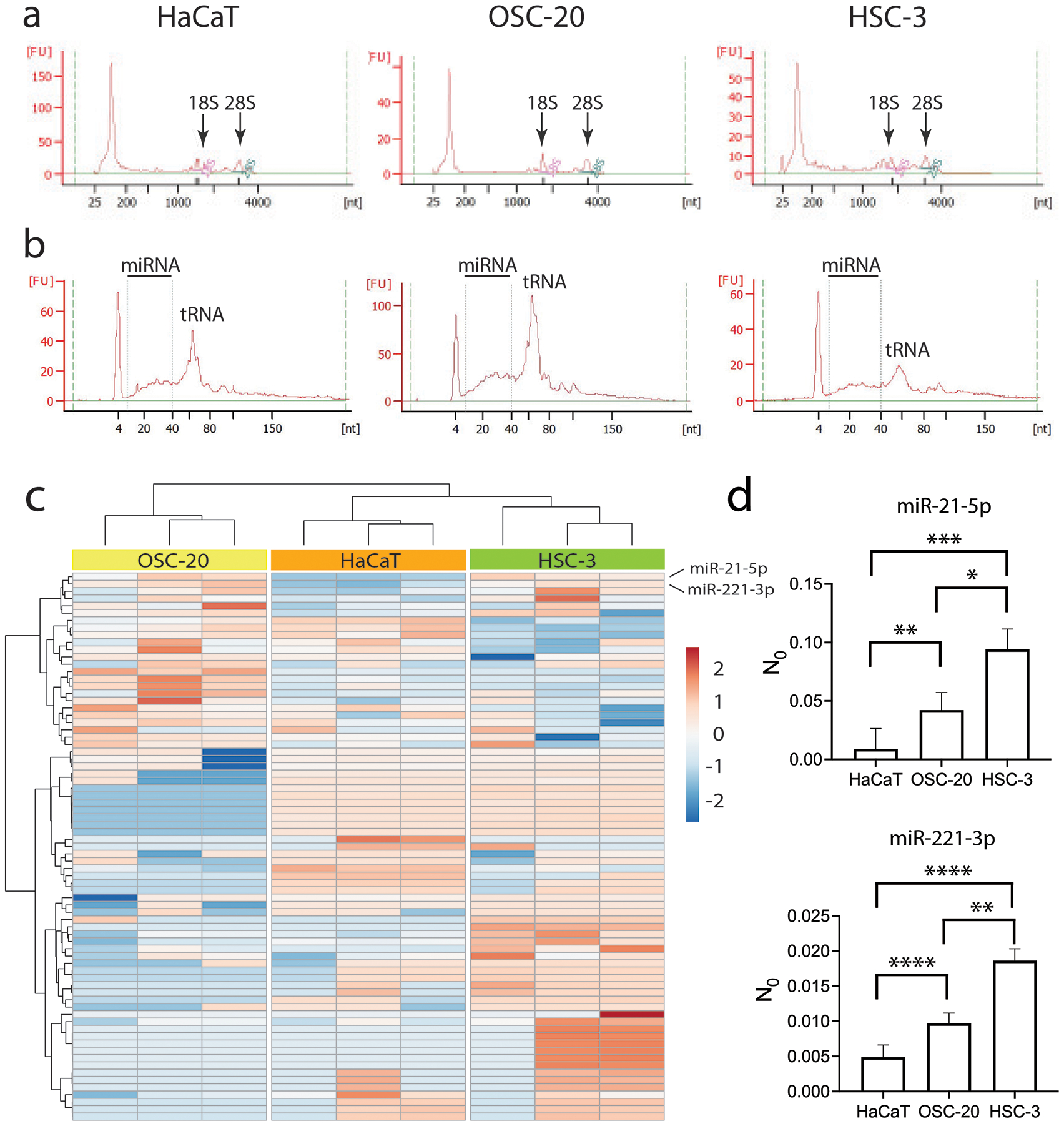

We isolated RNA from independent preparations of EVs from the cell lines. The isolated RNA preparations, analyzed by the Agilent Bioanalyzer pico and small RNA assays, were enriched for low molecular weight species. Little material was observed migrating at the expected positions of 18S and 28S ribosomal RNA (Figure 4a and 4b). Total RNA samples (100 ng) from three independent EV preparations from HSC-3, OSC-20 and HaCaT were analyzed with the NanoString nCounter Human v3 platform (800 miRNAs). We identified 105 miRNAs expressed in at least one sample (>20 counts). Hierarchical clustering revealed that the biological replicates clustered according to cell line with differences apparent among the three cell lines in their EV miRNA cargo (Figure 4c). Two miRNAs, hsa-miR-21-5p and hsa-miR-221-3p were enriched in EVs from the nociceptive oral cancer cell lines compared to HaCaT (log2 fold change = 1.65 and 1.62, q = 0.007 and 0.007, respectively).

Figure 4.

Total RNA isolated from EVs is mostly small RNA. Shown are electropherograms of total RNA from EVs using the Pico (a) and Small (b) Agilent Bioanalyzer assays. (c) Composition of EV miRNA cargoes differs among oral cancer cell lines HSC-3 and OSC-20 and keratinocyte line HaCaT. MicroRNAs with counts >50 in at least one sample in the NanoString nCounter assay were clustered by Euclidean distance and Ward linkage. Shown are cell lines in columns and miRNAs in rows. (d) Both miR-21-5p and miR-221-3p are more abundant in total RNA isolated from cancer cell line EVs than from HaCaT EVs as measured by qRT-PCR. Expression levels determined as the efficiency-corrected target quantity (N0) were measured in equal amounts of cDNA reverse transcribed from total RNA (3 ng) from three to four independent isolates of EVs. Plotted are the grand means and 95% confidence intervals. Expression levels of miR-21-5p for HaCaT: mean=0.009, n=3; OSC-20: mean=0.04, n=4; HSC-3: mean=0.09, n=3 (F(2,7) = 34.24, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, nested one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Expression levels of miR-221–3p for HaCaT: mean=0.005, n=3; OSC-20: mean=0.01, n=4; HSC-3: mean=0.02, n=3 (F(2,7) = 96.66, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001, nested one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Data replicated in two independent cDNA preparations.

2.4.2. Confirmation of differential expression of miR-21 and miR-221 in cancer EVs using quantitative real‐time PCR (qRT‐PCR).

We confirmed the data obtained with the NanoString platform by qRT-PCR. Expression levels of hsa-miR-21-5p and hsa-miR-221-3p were assayed in total RNA (3 ng) from independent preparations of EVs using TaqMan™ Advanced miRNA Assays. Because of the challenge associated with selecting appropriate internal controls for studies of small RNAs,[49] we compared the starting concentrations (N0) of the miRNAs in the cell line EV RNA, as determined by the LinRegPCR algorithm.[50,51] The LinRegPCR algorithm uses linear regression to calculate from the log-linear portion of the slope, the PCR efficiency (log efficiency) and the intercept, the starting concentration (logN0). This approach avoids assumptions about equal PCR efficiencies and allows direct comparison of the values of N0=10intercept in fluorescence units between samples. Expression of both miRNAs was higher in the cancer cell lines than in HaCaT (Figure 4d), consistent with the NanoString assay.

3. Discussion

3.1. Extracellular vesicles released by oral cancer cells carry protein and miRNA cargoes with potential to cause pain

Genes overexpressed in cancers from node positive oral cancer patients with pain have been reported in EVs and predicted to have functions in extracellular matrix organization, angiogenesis and neuritogenesis.[17] We demonstrated that depletion of EVs from cancer cell line CM reverses the nociception induced by the cancer cell line CM, while non cancer cell line CM reconstituted with cancer cell line EVs became nociceptive. We verified that a reported cancer pain mediator, legumain is present in oral cancer EVs and identified putative miRNA oral cancer pain mediators, miR-21 and miR-221. Both miR-21[52,53] and miR-221[54,55] are reported oncomiRs in a variety of cancers, including oral cancer.

Reference to miRNA target databases (e.g., Targetscan, MirBase, MirWalk, MiRanda) suggested a plethora of potential targets for the identified miRNAs. Therefore to identify target genes likely to impact oral cancer pain and cancer-neuronal interactions, we focused on experimentally verified target genes reported in the literature. Oral cancer pain (mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia) is associated with increased expression and activation and sensitization of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) and transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily A member 1 (TRPA1) on peripheral sensory nerves.[40,56] Expression levels of TRPV1 and TRPA1 are increased in the trigeminal ganglion in preclinical models of oral cancer pain. Potentiation of TRPV1 can occur through receptor phosphorylation and increased translocation to the plasma membrane in addition to increased expression. Antagonism of TRPV1 and TRPA1 reduces cancer associated nociception.

Validated targets of miR-221 likely to modulate neuronal functions include genes related to Schwann cell maturation and activation (ADAM22, NAB1),[57–59] neuritogenesis and neuron regeneration (PTEN, SOCS3, PTEN and SOCS3 together, VASH1)[60–64] and nociception (HIF1A, PPARGC1A, SOCS3).[65–69] miR-221 and target gene SOCS3 have been implicated in (cancer) pain. In a streptozotocin induced model of diabetic peripheral neuropathy, inhibition of miR-221 increased paw withdrawal thresholds and latencies in response to mechanical and thermal stimuli, respectively.[69] In a cancer model, overexpression of SOCS3 reduced cancer associated mechanical allodynia, but not thermal hyperalgesia.[68] SOCS3, is an inducible negative regulator of several cytokine signaling pathways involving Janus kinase (JAK) and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), including interleukin 6 (IL6) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF, encoded by CSF3). Signaling via JAK/STAT induces expression of SOCS3, which binds to specific cytokine receptors including the IL6 receptor gp130 (encoded by IL6ST) and G-CSF receptor (G-CSFR, encoded by CSF3R).[70] Both IL6[71] and G-CSF[72] have been reported to promote head and neck cancer and to act as mediators of cancer pain. Conditional deletion of gp130 in Nav1.8 neurons implicated IL6/gp130/JAK/STAT signaling in cancer induced mechanical hypersensitivity and transcriptional regulation of TRPA1.[73] Thermal sensitivity in a cancer model has been attributed to IL6/gp130 mediated activation of PKC δ and regulation of TRPV1.[74] Functional G-CSF receptors are expressed on nociceptors. Exposure of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neuron cultures to G-CSF induced up-regulation of TRPV1 and thermal hyperalgesia in a dose dependent manner.[75]

Increased local expression of miR-21 has been reported in clinical studies of patients with pain syndromes, including in lumbar disc herniation patients with sciatic pain[76] and in the prostatic secretion of patients with IIIA chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome.[77] Preclinical studies have established roles for miR-21 in oral cancer neuritogenesis[34] and pain.[78–80] miR-21 acts as ligand for toll like receptors 7 and 8 (TLR7 and TLR8).[28] Injection of miR-21 into the knee joint acutely induced transient mechanical allodynia in naïve rats. The miR-21 associated mechanical allodynia was suppressed by injection of a TLR7-specific antagonist, implicating, miR-21 acting as a ligand for TLR7. TLR7 and TLR8 are located in endosomes. miR-21 in EVs released from cancer cells functionally binds to and activates TLR7 and TLR8 in endosomes of recipient cells.[28] Binding results in activation of ERK and production of inflammatory mediators.[79,80]. We note that TLR7 is also present on the plasma membrane. Binding of miRNA-let-7b and miR-599 to TLR7 on the plasma membrane induces excitation of nociceptor neurons by coupling to TRPA1.[81] miR-21, however, does not have this capability; miR-21 lacks the required GUUGUGU motif present on miR-let-7b.

3.2. Identified oral cancer protein and miRNA pain mediators suggest multiple pathways contribute to oral cancer pain

Studies of animal models of oral cancer pain have identified a variety of pain mediators (Figure 5), including proteases,[48,82–85] lipids,[86] ATP[87] and genes involved in pain processing.[4,88] The number likely reflects the individual nature and intensity of pain experienced by patients.[5,6,17] Our group has focused on activation and sensitization of TRPV1 and TRPA1 via signaling through protease activated receptor 2 (Par2 encoded by F2RL1).[48,82–85] Cancers release proteases that cleave and activate Par2, which sensitize TRPV1 through protein kinase C alpha (PKA, encoded by PRKCA) and epsilon (PKCε encoded by PRKCE) dependent mechanisms.[89] Antagonism of Par2 or Par2 activating proteases reduces nociception in animal cancer models. Our study of patient reported pain identified activin A (encoded by INHBA) as a gene overexpressed in metastatic oral cancers from patients reporting high levels of pain.[17] Activin A, signaling through activin receptors and PKCε, sensitizes TRPV1 and evokes nociceptive behavior – tactile allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in rodents.[90,91]

Figure 5.

Multiple pathways contribute to oral cancer pain. Oral cancer cells release soluble mediators and EVs into the cancer microenvironment that activate and sensitize nociceptors. Cancer pain mediators interact with membrane bound receptors to activate downstream signaling pathways that increase expression or potentiate TRPV1 and TRPA1. Neuronal interactions may occur via ligand-receptor interactions with pain mediators that are soluble or carried on EVs (e.g., proteases activating Par2, IL6/gp130 signaling) and by internalization of EV cargoes following fusion, phagocytosis or endocytosis of the EVs, resulting in transfer of proteins and miRNAs that modify neuronal gene expression (e.g., miR-221, let-7d-5p) or act as ligands (e.g., miR-21/TLR7 signaling). Pain mediators include, in addition to those discussed in the text, endothelin (ET-1, encoded by EDN1, receptor ETAR, encoded by endothelin receptor type A, EDNRA), acids (H+), artemin (encoded by ARTN, receptors GFRα3/RET, encoded by GDNF family receptor alpha 3 and ret proto-oncogene, GFRA3 and RET), nerve growth factor (NGF, receptor TrkA, encoded by neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 1, NTRK1), adenosine triphosphate (ATP, receptors P2X2R and P2X3R, encoded by purinergic receptors P2X 2 and 3, P2RX2 and P2RX3) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα, encoded by TNF, receptor TNFR2 encoded by TNF receptor superfamily member 1B TNFRSF1B).

Loss of analgesia, provided by secretion of endogenous opioids (beta-endorphin and enkephalins), has also been studied as a mediator of oral cancer pain. Keratinocytes and lymphocytes secrete beta-endorphin.[92] Antinociception has been demonstrated for keratinocyte secreted beta-endorphin.[93] The mu opioid receptor 1 (MOR, encoded by OPRM1) is the receptor for endogenous opioids. Reduced expression of OPRM1 has been reported in oral cancers and in nerves innervating cancers and tissues in other pain states.[88,94,95] The loss of OPRM1 expression has been attributed to methylation of OPRM1 in oral cancers and to release from non-small cell lung cancer cells of EVs with miR-let-7d-5p that targets neuronal OPRM1 mRNA.[96] Delivery of OPRM1 into cancer cells is antinociceptive.[97]

The additional cancer pain signaling pathways suggested by the miRNAs identified here and the genes they target enrich the picture of cancer pain mediators and pathways (Figure 5). Abundance of miR-221 and miR-21 in oral cancer cell lines has highlighted the potential for cancer pain signaling through IL6/gp130 and G-CSF/G-CSFR, as well as TLR7 and TLR8, and suggests further investigation is warranted of these cancer pain pathways.

3.3. Oral cancers and patient experienced pain are heterogeneous

A limitation of our study is the small number of nociceptive and non-nociceptive cell lines queried for differential expression of pain mediators in cancer EVs, which cannot capture the molecular heterogeneity of oral cancers and patients’ experience of pain. MicroRNA EV cargoes differed between the two studied cancer cell lines (Figure 4c). Heterogeneity in nociceptive responses to lipids released by oral cancer cell lines has been reported previously.[86] Study of a greater number of oral cancer cell lines, potentially under hypoxic conditions, might reveal a role for additional EV miRNAs in oral cancer pain and provide a richer picture of pain mediators and pathways.

4. Conclusion

EVs released from oral cancer cells carry protein, lipid and miRNA cargoes with potential to activate and sensitize sensory neurons. Oral cancers are heterogeneous. Cancers take different paths to achieve the hallmarks of cancer, suggesting that the aforementioned signaling pathways, and likely others, contribute to neuronal sensitization and activation to different extents in different cancers. The challenge will be to measure the contributions made by the mediators that together result in in personal experiences of oral cancer pain.

5. Methods

Cell lines and supernatant collection.

Human oral tongue cancer cell lines, HSC-3 (JCRB Cat# JCRB0623, RRID:CVCL_1288, passages 4–12) and OSC-20 (Cat# JCRB0197, RRID:CVCL_3087, passages 4–12) were obtained from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank. The spontaneously immortalized human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT (RRID:CVCL_0038, passages 4–12) was purchased from AddexBio Technologies (Cat# T0020001, San Diego, CA). Human dysplastic keratinocyte cell line DOK (RRID:CVCL, 1180, passages 4–12) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat# 94122104). The cell lines harbor mutations in TP53. Further information on the mutational status of the HSC-3, OSC-20 and DOK cell lines can be obtained from COSMIC, the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk).[98] The cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA, HSC-3, DOK, HaCaT) or DMEM/F12 (OSC-20) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin (50 U/mL) for 48 hours. Cell lines were cultured in 75 cm2 cell culture flasks at 37°C with 5% CO2, 21% O2 (normoxia). When cells reached 70–80% confluency, the culture medium was replaced with media supplemented with 10% exosome-depleted FBS (Gibco) and cultured for a further 48 hours for preparation of exosomes. Cell culture supernatant was collected and used for isolation of exosomes.

Extracellular vesicle (EV) isolation by ultracentrifugation.

Cell culture supernatant was centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 minutes to pellet cells, then transferred to a fresh tube and centrifuged at 2000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C to remove dead cells. The supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove cell debris. Extracellular vesicles were isolated by ultracentrifugation at 120,000 × g for 70 minutes at 4°C. The pellet was washed with DPBS followed by repeat ultracentrifugation under the same conditions. The EV pellet was suspended in 40–50 μL DPBS and used immediately.

Transmission electron microscopy.

A 5 μL suspension of EVs in 2% formaldehyde in PBS was added onto a carbon coated 400 mesh Cu/Rh grid (Ted Pella Inc., Redding, CA) and stained with 1% uranyl acetate (Polysciences, Inc, Warrington, PA) in ddH2O. Stained grids were examined with a Thermo Fisher Talos L120C transmission electron microscope and photographed with a Gatan OneView digital camera.

Western blotting analysis.

Protein samples were separated by 4–12% Bis-Tris Gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to a 0.2 μm pore-size nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). The primary antibodies used were: rabbit polyclonal anti-TSG101 (1:1000, Bethyl Laboratories Inc., Cat# A303–507A, RRID:AB_10971167), rabbit polyclonal anti-CD63 (1:1000, Invitrogen, Cat# PA5–78995, RRID:AB_2746111), mouse monoclonal anti-human ALIX (1:2000, Bio-Rad PrecisionAb western blot validated, clone OTI1A4, VMA00273), sheep polyclonal anti-GM130/GOLGA2 (1:1000, R&D Systems Cat# AF8199-SP), rabbit anti-calnexin (1:2000, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# C4731, RRID:AB_476845). The secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase were: donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000, GE Healthcare Cat# NA934, RRID:AB- 772206), sheep anti-mouse (1:10,000, GE Healthcare Cat# NA931, RRID:AB_772210), donkey anti-sheep (1:10,000, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., Cat# 713-035-003, RRID:AB_2340709), donkey anti-goat (1:10,000, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# A15999, RRID: AB_2534673). The pre-stained protein ladder was from Abcam (ab234592).

Cancer cell line conditioned media EV depleted/reconstituted pain model.

For preparation of conditioned media, cells were cultured in two 10 cm cell culture dishes in 10 mL of media and 10% exosome depleted FBS for 48 hours (70–80% confluent). The cells were washed three times with PBS and cultured for a further 48 hours in 3 mL serum-free DMEM without phenol red. Cell culture supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 minutes to pellet cells. The supernatant was centrifuged at 2000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C, 10,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C, and filtered through a 0.22 μm Millipore filter to remove dead cells, debris and large vesicles. One mL of media was loaded on a Sepharose CL-2B column (1.5 cm × 6.2 cm) and 0.5 mL fractions were collected. Extracellular vesicles elute in fractions 8–11.[17] To prepare exosome depleted and reconstituted CM, fractions 8–11 (EV fraction) and 12–26 (EV depleted fraction) were each concentrated to 1 mL using Vivaspin 3 kDa MWCO centrifugal concentrators. The reconstituted CM (EV+ & EV−) was prepared by mixing 0.5 mL each of the EV+ and EV depleted fractions and concentrating the mixture to a final volume of 1 mL using Vivaspin 3 kDa MWCO centrifugual concentrators.

Following recording baseline behavior, male mice (C57BL/6J, 8 weeks old, JAX # 000664) were arbitrarily selected to receive one of five treatments by an investigator blinded to the identity of the treatment. The mice received an intraplantar injection (20 μL) into the right hind paw under 1% isoflurane anesthesia of 1) cell line CM, 2) cell line media only (DMEM), 3) conditioned media depleted of EVs by size exclusion chromatography (EV−, Cell line CM, EV depleted), 4) EV depleted CM reconstituted with the cell line EV fraction (EV− & EV+, cell line CM, reconstituted), or 5) EV depleted cell line CM reconstituted with the HSC-3 EV fraction (EV− & HSC-3 EV). Based on our experience with the paw withdrawal assay, group sizes of at least four mice were used (Table S5). Animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the National Institute of Health guidelines and the PHS Policy on the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The protocol (IA16–00437) was approved by the New York University Langone Health Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Behavioral testing.

Each mouse was tested for mechanical nociception and thermal hyperalgesia. Thermal hyperalgesia was measured 20 minutes after von Frey testing. Mechanical nociception was measured with calibrated von Frey filaments (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA). The mice were placed individually in a transparent chamber on a raised platform with a metal mesh floor for one hour before testing. The right hind paw was stimulated with the von Frey filament through the mesh floor of each chamber. Withdrawal threshold was defined as the gram-force sufficient to elicit a distinct paw withdrawal upon application of the von Frey filament tip. Withdrawal threshold was determined as the mean of three trials for each animal. The mechanical nociception assay was conducted before (Baseline), 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 hour(s) after the right plantar injection.

Thermal hyperalgesia was measured with a paw thermal stimulator (IITC Life Sciences, Woodland Hills, CA). The mice were placed in a transparent chamber on a pre-heated (29°C) glass surface for one hour before the thermal hyperalgesia assay. A radiant heat source was focused on the right hind paw. Paw withdrawal latency was measured as the mean of three trials taken at least 5 minutes apart. The cut-off latency was established at 20 seconds to avoid tissue damage. The thermal hyperalgesia assay was conducted before (Baseline), 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 hour(s) after the right plantar injection. The investigators performing the mechanical nociception and thermal hyperalgesia assays were blinded to the treatment.

RNA isolation and miRNA expression analysis using the NanoString nCounter platform.

Total RNA was extracted from cell culture supernatant from three independent cell cultures (median volume = 90 mL, range 70–110 mL) using a Total Exosome RNA and Protein Isolation Kit (Invitrogen). The RNA yield was measured using the Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and RNA quality was assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer pico and small RNA assays (Agilent Technologies). Samples (100 ng total EV RNA) were analyzed using a NanoString nCounter Max/Flex prep station and digital analyzer and the nCounter Human v3 miRNA Assay, which contains probes for 798 miRNAs. Hybridization to capture and reporter probes was carried out overnight at 65° C. Counts were obtained by scanning 550 fields of view and data displayed with the nSolver software (Table S6). Probes with >20 counts were considered expressed (n=105 miRNA probes expressed in at least one sample). Counts were normalized to total counts for each sample (total counts range, 5,000–13,000).

RNA isolation and miRNA analysis by qRT-PCR.

Expression of selected miRNAs was measured using quantitative RT-PCR. Total RNA (3 ng) was reverse transcribed into first-strand cDNA with a TaqMan Advanced miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. TaqMan™ Advanced miRNA Assays for hsa-miRNA-21-5p (Primer Assay ID 477975_mir, cat# A25576) and hsa-miR-221-3p (Assay ID 477981_mir, cat# A25576) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Triplicate reactions for each biological sample were carried out using the TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Thermal cycling conditions included an initial step at 95°C for 20 seconds, and 40 cycles at 95°C for 1 second and at 60°C for 20 seconds. Raw data from the AriaMX thermal cycler (Agilent Technologies, Software Version 1.8) were exported in rdml format[99] and uploaded to the LinRegPCR website for analysis (https://www.gear-genomics.com/rdml-tools/).

Statistical analysis.

We used GraphPad Prism 9 for Mac OSX (version 9.3.1) to test for mean differences between groups. Hierarchical clustering was performed using ClustVis.[100]

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Drs. Dubeykovskaya and Tu contributed equally to this work, which was supported by NIH Grants R01 CA228525 and R01 CA231396. Dr. Ramírez Garcia is the recipient of an International Association for the Study of Pain John J. Bonica Trainee Fellowship. We thank Kristen Dancel-Manning, NYU Langone Health Microscopy Laboratory for assistance with TEM work. The NanoString nCounter assays were performed by the NYU Langone Health Genome Technology Center. These shared resources are partially funded by the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Comprehensive Cancer Center support grant, P30CA016087. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library.

Conflict of Interest

The authors state that they have no financial or commercial Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J, Ann Oncol. 2007,18, 1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickering V, Jay Gupta R, Quang P, Jordan RC, Schmidt BL, Eur J Pain. 2008,12, 293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt BL, Pickering V, Liu S, Quang P, Dolan J, Connelly ST, Jordan RC, Eur J Pain. 2007,11, 406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viet CT, Ye Y, Dang D, Lam DK, Achdjian S, Zhang J, Schmidt BL, Pain. 2011,152, 2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connelly ST, Schmidt BL, J Pain. 2004,5, 505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolokythas A, Connelly ST, Schmidt BL, J Pain. 2007,8, 950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji RR, Chamessian A, Zhang YQ, Science. 2016,354, 572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faulkner S, Jobling P, March B, Jiang CC, Hondermarck H, Cancer Discov. 2019,9, 702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zahalka AH, Frenette PS, Nat Rev Cancer. 2020,20, 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt PJ, Andujar FN, Silverman DA, Amit M, Neurosci Lett. 2021,746, 135658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gysler SM, Drapkin R, J Clin Invest. 2021,131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujiwara T, Kubo T, Kanazawa S, Shingaki K, Taniguchi M, Matsuzaki S, Gurtner GC, Tohyama M, Hosokawa K, Wound Repair Regen. 2013,21, 588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu M, Warn JD, Fan Q, Smith PG, Cell Tissue Res. 1999,297, 423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheret J, Lebonvallet N, Buhe V, Carre JL, Misery L, Le Gall-Ianotto C, J Dermatol Sci. 2014,74, 193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roggenkamp D, Kopnick S, Stab F, Wenck H, Schmelz M, Neufang G, J Invest Dermatol. 2013,133, 1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu XJ, Li CY, Xu YH, Chen LM, Zhou CL, Cell Biol Int. 2009,33, 1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhattacharya A, Janal MN, Veeramachaneni R, Dolgalev I, Dubeykovskaya Z, Tu NH, Kim H, Zhang S, Wu AK, Hagiwara M, Kerr AR, DeLacure MD, Schmidt BL, Albertson DG, Sci Rep. 2020,10, 14724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puram SV, Tirosh I, Parikh AS, Patel AP, Yizhak K, Gillespie S, Rodman C, Luo CL, Mroz EA, Emerick KS, Deschler DG, Varvares MA, Mylvaganam R, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Rocco JW, Faquin WC, Lin DT, Regev A, Bernstein BE, Cell. 2017,171, 1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parikh AS, Puram SV, Faquin WC, Richmon JD, Emerick KS, Deschler DG, Varvares MA, Tirosh I, Bernstein BE, Lin DT, Oral Oncol. 2019,99, 104458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keerthikumar S, Chisanga D, Ariyaratne D, Al Saffar H, Anand S, Zhao K, Samuel M, Pathan M, Jois M, Chilamkurti N, Gangoda L, Mathivanan S, J Mol Biol. 2016,428, 688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiteside TL, Adv Clin Chem. 2016,74, 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoshino A, Kim HS, Bojmar L, Gyan KE, Cioffi M, Hernandez J, Zambirinis CP, Rodrigues G, Molina H, Heissel S, Mark MT, Steiner L, Benito-Martin A, Lucotti S, Di Giannatale A, Offer K, Nakajima M, Williams C, Nogues L, Pelissier Vatter FA, Hashimoto A, Davies AE, Freitas D, Kenific CM, Ararso Y, Buehring W, Lauritzen P, Ogitani Y, Sugiura K, Takahashi N, Aleckovic M, Bailey KA, Jolissant JS, Wang H, Harris A, Schaeffer LM, Garcia-Santos G, Posner Z, Balachandran VP, Khakoo Y, Raju GP, Scherz A, Sagi I, Scherz-Shouval R, Yarden Y, Oren M, Malladi M, Petriccione M, De Braganca KC, Donzelli M, Fischer C, Vitolano S, Wright GP, Ganshaw L, Marrano M, Ahmed A, DeStefano J, Danzer E, Roehrl MHA, Lacayo NJ, Vincent TC, Weiser MR, Brady MS, Meyers PA, Wexler LH, Ambati SR, Chou AJ, Slotkin EK, Modak S, Roberts SS, Basu EM, Diolaiti D, Krantz BA, Cardoso F, Simpson AL, Berger M, Rudin CM, Simeone DM, Jain M, Ghajar CM, Batra SK, Stanger BZ, Bui J, Brown KA, Rajasekhar VK, Healey JH, de Sousa M, Kramer K, Sheth S, Baisch J, Pascual V, Heaton TE, La Quaglia MP, Pisapia DJ, Schwartz R, Zhang H, Liu Y, Shukla A, Blavier L, DeClerck YA, LaBarge M, Bissell MJ, Caffrey TC, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, Bromberg J, Costa-Silva B, Peinado H, Kang Y, Garcia BA, O’Reilly EM, Kelsen D, Trippett TM, Jones DR, Matei IR, Jarnagin WR, Lyden D, Cell. 2020,182, 1044.32795414 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H, Freitas D, Kim HS, Fabijanic K, Li Z, Chen H, Mark MT, Molina H, Martin AB, Bojmar L, Fang J, Rampersaud S, Hoshino A, Matei I, Kenific CM, Nakajima M, Mutvei AP, Sansone P, Buehring W, Wang H, Jimenez JP, Cohen-Gould L, Paknejad N, Brendel M, Manova-Todorova K, Magalhaes A, Ferreira JA, Osorio H, Silva AM, Massey A, Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Galletti G, Giannakakou P, Cuervo AM, Blenis J, Schwartz R, Brady MS, Peinado H, Bromberg J, Matsui H, Reis CA, Lyden D, Nat Cell Biol. 2018,20, 332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeppesen DK, Fenix AM, Franklin JL, Higginbotham JN, Zhang Q, Zimmerman LJ, Liebler DC, Ping J, Liu Q, Evans R, Fissell WH, Patton JG, Rome LH, Burnette DT, Coffey RJ, Cell. 2019,177, 428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Q, Jeppesen DK, Higginbotham JN, Graves-Deal R, Trinh VQ, Ramirez MA, Sohn Y, Neininger AC, Taneja N, McKinley ET, Niitsu H, Cao Z, Evans R, Glass SE, Ray KC, Fissell WH, Hill S, Rose KL, Huh WJ, Washington MK, Ayers GD, Burnette DT, Sharma S, Rome LH, Franklin JL, Lee YA, Liu Q, Coffey RJ, Nat Cell Biol. 2021,23, 1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Q, Higginbotham JN, Jeppesen DK, Yang YP, Li W, McKinley ET, Graves-Deal R, Ping J, Britain CM, Dorsett KA, Hartman CL, Ford DA, Allen RM, Vickers KC, Liu Q, Franklin JL, Bellis SL, Coffey RJ, Cell Rep. 2019,27, 940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartel DP, Cell. 2004,116, 281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fabbri M, Paone A, Calore F, Galli R, Gaudio E, Santhanam R, Lovat F, Fadda P, Mao C, Nuovo GJ, Zanesi N, Crawford M, Ozer GH, Wernicke D, Alder H, Caligiuri MA, Nana-Sinkam P, Perrotti D, Croce CM, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012,109, E2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehmann SM, Kruger C, Park B, Derkow K, Rosenberger K, Baumgart J, Trimbuch T, Eom G, Hinz M, Kaul D, Habbel P, Kalin R, Franzoni E, Rybak A, Nguyen D, Veh R, Ninnemann O, Peters O, Nitsch R, Heppner FL, Golenbock D, Schott E, Ploegh HL, Wulczyn FG, Lehnardt S, Nat Neurosci. 2012,15, 827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ, Nat Rev Cancer. 2006,6, 259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otmani K, Lewalle P, Front Oncol. 2021,11, 708765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu W, Liu C, Bi ZY, Zhou Q, Zhang H, Li LL, Zhang J, Zhu W, Song YY, Zhang F, Yang HM, Bi YY, He QQ, Tan GJ, Sun CC, Li DJ, Mol Cancer. 2020,19, 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madeo M, Colbert PL, Vermeer DW, Lucido CT, Cain JT, Vichaya EG, Grossberg AJ, Muirhead D, Rickel AP, Hong Z, Zhao J, Weimer JM, Spanos WC, Lee JH, Dantzer R, Vermeer PD, Nat Commun. 2018,9, 4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amit M, Takahashi H, Dragomir MP, Lindemann A, Gleber-Netto FO, Pickering CR, Anfossi S, Osman AA, Cai Y, Wang R, Knutsen E, Shimizu M, Ivan C, Rao X, Wang J, Silverman DA, Tam S, Zhao M, Caulin C, Zinger A, Tasciotti E, Dougherty PM, El-Naggar A, Calin GA, Myers JN, Nature. 2020,578, 449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bali KK, Selvaraj D, Satagopam VP, Lu J, Schneider R, Kuner R, EMBO Mol Med. 2013,5, 1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalpachidou T, Kummer KK, Kress M, Neuronal Signal. 2020,4, NS20190099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakai A, Suzuki H, Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015,888, 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL, J Neurosci Methods. 1994,53, 55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J, Pain. 1988,32, 77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ye Y, Dang D, Zhang J, Viet CT, Lam DK, Dolan JC, Gibbs JL, Schmidt BL, Mol Cancer Ther. 2011,10, 1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Momose F, Araida T, Negishi A, Ichijo H, Shioda S, Sasaki S, J Oral Pathol Med. 1989,18, 391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang SE, Foster S, Betts D, Marnock WE, Int J Cancer. 1992,52, 896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boukamp P, Petrussevska RT, Breitkreutz D, Hornung J, Markham A, Fusenig NE, J Cell Biol. 1988,106, 761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang D, Xiong M, Chen C, Du L, Liu Z, Shi Y, Zhang M, Gong J, Song X, Xiang R, Liu E, Tan X, Kidney Int. 2018,94, 91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li X, Tang M, Zhu Q, Wang X, Lin Y, Wang X, Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2020,43, 263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang W, Lin Y, Cells. 2021,10. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yao P, Ding Y, Han Z, Mu Y, Hong T, Zhu Y, Li H, Mol Pain. 2017,13, 1744806917708127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tu NH, Jensen DD, Anderson BM, Chen E, Jimenez-Vargas NN, Scheff NN, Inoue K, Tran HD, Dolan JC, Meek TA, Hollenberg MD, Liu CZ, Vanner SJ, Janal MN, Bunnett NW, Edgington-Mitchell LE, Schmidt BL, J Neurosci. 2021,41, 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi J, J Clin Med. 2016,5. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramakers C, Ruijter JM, Deprez RH, Moorman AF, Neurosci Lett. 2003,339, 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Untergasser A, Ruijter JM, Benes V, van den Hoff MJB, BMC bioinformatics. 2021,22, 398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jung HM, Phillips BL, Patel RS, Cohen DM, Jakymiw A, Kong WW, Cheng JQ, Chan EK, J Biol Chem. 2012,287, 29261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawakita A, Yanamoto S, Yamada S, Naruse T, Takahashi H, Kawasaki G, Umeda M, Pathol Oncol Res. 2014,20, 253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He S, Lai R, Chen D, Yan W, Zhang Z, Liu Z, Ding X, Chen Y, Biomed Res Int. 2015,2015, 751672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amini S, Abak A, Sakhinia E, Abhari A, Lab Med. 2019,50, 333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nagamine K, Ozaki N, Shinoda M, Asai H, Nishiguchi H, Mitsudo K, Tohnai I, Ueda M, Sugiura Y, J Pain. 2006,7, 659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ozkaynak E, Abello G, Jaegle M, van Berge L, Hamer D, Kegel L, Driegen S, Sagane K, Bermingham JR Jr., Meijer D, J Neurosci. 2010,30, 3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lancaster E, Burnor E, Zhang J, Lancaster E, Neurosci Lett. 2019,704, 159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao L, Yuan Y, Li P, Pan J, Qin J, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Tian F, Yu B, Zhou S, Neuroscience. 2018,379, 239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mak HK, Ng SH, Ren T, Ye C, Leung CK, Exp Eye Res. 2020,192, 107938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miao T, Wu D, Zhang Y, Bo X, Subang MC, Wang P, Richardson PM, J Neurosci. 2006,26, 9512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mishra KK, Gupta S, Banerjee K, IUBMB Life. 2016,68, 468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith PD, Sun F, Park KK, Cai B, Wang C, Kuwako K, Martinez-Carrasco I, Connolly L, He Z, Neuron. 2009,64, 617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Castillo X, Melo Z, Varela-Echavarria A, Tamariz E, Arona RM, Arnold E, Clapp C, de la Escalera G. Martinez, Neuroendocrinology. 2018,106, 221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kanngiesser M, Mair N, Lim HY, Zschiebsch K, Blees J, Haussler A, Brune B, Ferreiros N, Kress M, Tegeder I, Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014,20, 2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miao J, Zhou X, Ding W, You Z, Doheny J, Mei W, Chen Q, Mao J, Shen S, Anesth Analg. 2020,130, 240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meng W, Hao MM, Yu N, Li MY, Ding JQ, Wang BH, Zhu HL, Xie M, Mol Pain. 2019,15, 1744806919871813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wei J, Li M, Wang D, Zhu H, Kong X, Wang S, Zhou YL, Ju Z, Xu GY, Jiang GQ, Mol Pain. 2017,13, 1744806916688901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu X, Wang X, Yin Y, Zhu L, Zhang F, Yang J, Adv Clin Exp Med. 2021,30, 623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Babon JJ, Nicola NA, Growth Factors. 2012,30, 207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yadav A, Kumar B, Datta J, Teknos TN, Kumar P, Mol Cancer Res. 2011,9, 1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gutschalk CM, Herold-Mende CC, Fusenig NE, Mueller MM, Cancer Res. 2006,66, 8026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Quarta S, Vogl C, Constantin CE, Uceyler N, Sommer C, Kress M, Mol Pain. 2011,7, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Andratsch M, Mair N, Constantin CE, Scherbakov N, Benetti C, Quarta S, Vogl C, Sailer CA, Uceyler N, Brockhaus J, Martini R, Sommer C, Zeilhofer HU, Muller W, Kuner R, Davis JB, Rose-John S, Kress M, J Neurosci. 2009,29, 13473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stosser S, Schweizerhof M, Kuner R, J Mol Med (Berl). 2011,89, 321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zou ZF, He JP, Chen YL, Chen HL, Adv Clin Exp Med. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Chen Y, Chen S, Zhang J, Wang Y, Jia Z, Zhang X, Han X, Guo X, Sun X, Shao C, Wang J, Lan T, Oncotarget. 2018,9, 12186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hoshikawa N, Sakai A, Takai S, Suzuki H, Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020,19, 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu T, Gao YJ, Ji RR, Neurosci Bull. 2012,28, 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang ZJ, Guo JS, Li SS, Wu XB, Cao DL, Jiang BC, Jing PB, Bai XQ, Li CH, Wu ZH, Lu Y, Gao YJ, J Exp Med. 2018,215, 3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Park CK, Xu ZZ, Berta T, Han Q, Chen G, Liu XJ, Ji RR, Neuron. 2014,82, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lam DK, Dang D, Flynn AN, Hardt M, Schmidt BL, Pain. 2015,156, 923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lam DK, Dang D, Zhang J, Dolan JC, Schmidt BL, J Neurosci. 2012,32, 14178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lam DK, Schmidt BL, Pain. 2010,149, 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tu NH, Inoue K, Chen E, Anderson BM, Sawicki CM, Scheff NN, Tran HD, Kim DH, Alemu RG, Yang L, Dolan JC, Liu CZ, Janal MN, Latorre R, Jensen DD, Bunnett NW, Edgington-Mitchell LE, Schmidt BL, Cancers (Basel). 2021,13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ruparel S, Bendele M, Wallace A, Green D, Mol Pain. 2015,11, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ye Y, Ono K, Bernabe DG, Viet CT, Pickering V, Dolan JC, Hardt M, Ford AP, Schmidt BL, Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014,2, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Viet CT, Dang D, Ye Y, Ono K, Campbell RR, Schmidt BL, Clin Cancer Res. 2014,20, 4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Amadesi S, Cottrell GS, Divino L, Chapman K, Grady EF, Bautista F, Karanjia R, Barajas-Lopez C, Vanner S, Vergnolle N, Bunnett NW, J Physiol. 2006,575, 555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhu W, Xu P, Cuascut FX, Hall AK, Oxford GS, J Neurosci. 2007,27, 13770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xu P, Van Slambrouck C, Berti-Mattera L, Hall AK, J Neurosci. 2005,25, 9227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wintzen M, Yaar M, Burbach JP, Gilchrest BA, J Invest Dermatol. 1996,106, 673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Khodorova A, Navarro B, Jouaville LS, Murphy JE, Rice FL, Mazurkiewicz JE, Long-Woodward D, Stoffel M, Strichartz GR, Yukhananov R, Davar G, Nat Med. 2003,9, 1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Suzuki M, Narita M, Hasegawa M, Furuta S, Kawamata T, Ashikawa M, Miyano K, Yanagihara K, Chiwaki F, Ochiya T, Suzuki T, Matoba M, Sasaki H, Uezono Y, Anesthesiology. 2012,117, 847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lee CY, Perez FM, Wang W, Guan X, Zhao X, Fisher JL, Guan Y, Sweitzer SM, Raja SN, Tao YX, Eur J Pain. 2011,15, 669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Li X, Chen Y, Wang J, Jiang C, Huang Y, Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021,9, 666857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yamano S, Viet CT, Dang D, Dai J, Hanatani S, Takayama T, Kasai H, Imamura K, Campbell R, Ye Y, Dolan JC, Kwon WM, Schneider SD, Schmidt BL, Pain. 2017,158, 240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, Sondka Z, Beare DM, Bindal N, Boutselakis H, Cole CG, Creatore C, Dawson E, Fish P, Harsha B, Hathaway C, Jupe SC, Kok CY, Noble K, Ponting L, Ramshaw CC, Rye CE, Speedy HE, Stefancsik R, Thompson SL, Wang S, Ward S, Campbell PJ, Forbes SA, Nucleic Acids Res. 2019,47, D941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ruijter JM, Lefever S, Anckaert J, Hellemans J, Pfaffl MW, Benes V, Bustin SA, Vandesompele J, Untergasser A, consortium R, BMC bioinformatics. 2015,16, 197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Metsalu T, Vilo J, Nucleic Acids Res. 2015,43, W566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.