Abstract

The primary objective of preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic disorders (PGT-M) is to avoid having a child with a serious monogenic disease. Combining testing for unrelated sporadic chromosomal abnormalities (PGT-A) and excluding embryos with chromosomally abnormal results from transfer proffers the chance to mitigate the risk of miscarriage and to reduce the number of embryo transfers, but also risks excluding healthy embryos from transfer due to abnormal test results that do not reflect the true potential of the embryo. The theoretical utility of combining PGT-M with PGT-A is explored in this communication. It is concluded that PGT-M without PGT-A is preferred to achieve an unaffected live birth. Since PGT-M is mostly undertaken by couples where the female partner is younger than 35 years, PGT-A is likely to marginally mitigate the risk of miscarriage. Experimental non-selection studies are needed to assess the potential detrimental effect of combining PGT-M with PGT-A in a clinical setting.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10815-022-02519-8.

Keywords: PGT-M, Monogenic disorders, Preimplantation genetic testing, Aneuploidy

Aneuploidy screening was introduced because of the well-known association of an increased risk of a trisomic conception for older women. It was thought that avoiding transferring age-related embryos with common aneuploidies would reduce the risk of spontaneous miscarriage and termination of an affected pregnancy thereby improving the efficiency of IVF for older women [1]. Historically, an effort was often made to differentiate preimplantation genetic testing for serious inherited genetic diseases from trying to optimise IVF [2]. The distinction could also be a moot point, particularly for couples with recurrent primary trisomy 21, or men presenting with the common 13/14 Robertsonian translocation and infertility. The fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) technique previously in common use for sex-determination, for sex-linked diseases and for structural chromosome rearrangements, also enabled incorporating DNA probes for unrelated chromosomes into the test (typically 13, 18 and 21 where trisomy for these chromosomes is associated with Patau, Edwards and Down syndrome respectively). Due to the limitations of the FISH technology, the practice of trying to do too much also risked compromising the utility of the test [3]. PGT is now in an era where next-generation sequencing technology (NGS) offers a universal platform, combining testing for inherited pathogenic variants associated with serious genetic disease (PGT-M), inherited chromosomal imbalance due to meiotic segregation of parental chromosomal rearrangements (PGT-SR) and unrelated sporadic meiotic and mitotic chromosomal abnormalities (chromosomal aneuploidy and segmental imbalance) for every chromosome (PGT-A).

The latest ESHRE PGT Consortium data collection publication for the period 2016 to 2017 reported that 7% (225/3098) of PGT-M and 42% (429/1018) of PGT-SR analyses were combined with PGT-A, with a mean maternal age of 34.8 and 34.0 years respectively at oocyte retrieval, and commented that the practice of accumulating embryos from more than 1 stimulated cycle before analysis was more likely to be applied [4].

In an audit of PGT-M/SR activity in the UK (monogenic disorders and structural rearrangements were not differentiated by the HFEA) for the period January 2016 to December 2018, 2 clinics (both employing a freeze-all strategy with blastocyst transfer: 1 known to combine PGT-A, 298 attempted thaw cycles; 1 known not to use PGT-A, 1131 attempted thaw cycles) accounted for 73% (1429/1950) of all PGT-M/SR cycles identified (fresh and frozen), of which 67% (964/1429) were for women aged less than 35 years [5]. Compared to IVF/ICSI cycles for these clinics, it seems likely that PGT-M/SR couples had a better prognosis for a live birth with or without PGT-A, and that testing for unrelated chromosomal abnormalities was unlikely to mitigate the risk of clinical miscarriage and improve a transferred embryo’s chance of success. However, due to the inherent lack of granularity in the HFEA data, there is potential for confounding caused by pooling recessive and dominant autosomal and sex-linked disorders, and different types of chromosomal rearrangements.

Previous simulated trials for PGT-SR (specifically reciprocal translocations) and PGT-M (specifically autosomal recessive disorders) [6, 7] have shown that PGT with or without PGT-A is expected to be effective in preventing an abnormal pregnancy, but excluding all test results indicating unrelated chromosomal imbalance is detrimental to the cumulative live birth rate for women with up to 14 blastocysts (median 5). The detriment can be avoided by ranking rather than excluding embryos from transfer; however, this is also problematical if embryos with test results of uncertain reproductive potential merely remain in the freezer [8], and transferring an embryo with a putative abnormal test result is likely to be difficult and raise concern regarding the health and wellbeing of any pregnancy and live born child, which may always persist.

In a recent article in this journal, Shen and colleagues [9] report the results of retesting stored DNA for unrelated chromosomal abnormalities (PGT-A) from trophectoderm samples of blastocysts that had resulted in a live birth following PGT-M. They found that 17.1% (13/76) of embryos resulting in a live birth would have been excluded from transfer, 11 embryos due to an aneuploid test result and 2 embryos with an intermediate copy number test result consistent with > 50% aneuploid cells (aneuploid/diploid mosaicism) in the sample.

The analysis presented here (see Supplementary data material) envisages women aged less than 35 years undergoing a first cycle of preimplantation genetic testing for a monogenic disorder, either testing only for the affected gene (PGT-M) or combined with testing for unrelated chromosomal gain/loss (whole-chromosome aneuploidy and segmental imbalance) (PGT-MA). Employing a freeze-all strategy and taking into account diagnostic accuracy, single vitrified-warmed embryo transfers are performed (with a 98% warming survival rate) until there is a live birth event or no more embryos are available; the calculations were made using a spreadsheet tool developed previously [10]. The context is that DNA from a trophectoderm biopsy sample is analysed using next-generation sequencing (NGS), and blastocysts with an abnormal test result are excluded from transfer (those consistent with an affected genotype for the monogenic disorder, non-mosaic aneuploidy and segmental imbalance, and intermediate results indicating aneuploid/diploid mosaicism with > 50% chromosomal abnormality). Based on Shen and colleagues’ study [8], it was assumed that 17.1% (95% CI 9.4–27.5%) of unaffected healthy live births following PGT-M could be excluded due to an abnormal test result for unrelated chromosomal abnormalities that do not reflect the true potential of the embryo (false positives). The base, best (lower 95% CI limit), worst (upper 95% CI limit) and optimised (a putative calculated positive predictive value of at least 95%) case scenarios assumed false positive rates of 17.1%, 9.4%, 27.5% and 1.8% respectively, in the context of clinics with typical and high IVF/ICSI success rates. The clinic success groups are subjective and are based on live births per embryo transferred (high success being 60% PGT-MA vs 50% PGT-M, RR 1.2) and typical success being 45.6% PGT-MA vs 38.0% PGT-M, RR 1.2). The miscarriage rates per clinical pregnancy are similar for both success groups (5% PGT-MA vs 8% PGT-M, RR 0.625). Binomial theorem [11] was used to estimate the number of blastocysts for testing to give at least an 80% chance of obtaining at least the number of unaffected embryos required for an autosomal recessive and dominant monogenic condition (assuming a 25% and 50% risk of an affected genotype respectively).

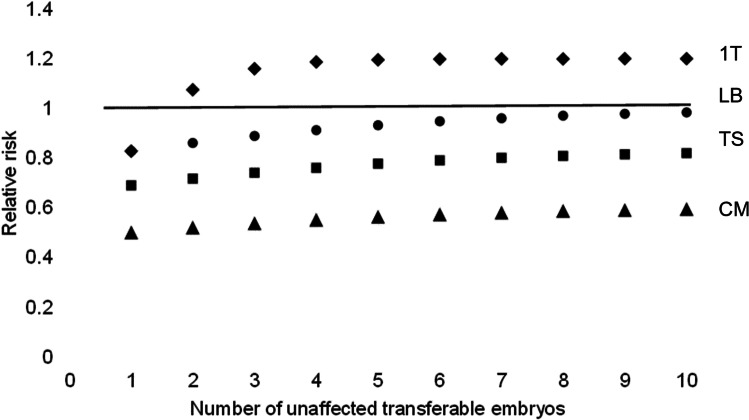

Table 1 shows a summary of all the scenarios (see Supplementary data material). Figure 1 shows the base model for a clinic with a typical success rate (scenario 2.1). Testing for unrelated chromosomal gain/loss has utility to differentiate a viable blastocyst when there are 2 or more embryos available which are unaffected for the monogenic condition (1 T RR > 1, P < 0.05, Pearson’s chi-square). The deficit in the cumulative live birth rate is less than 5% for 7 or more embryos (LB RR > 0.95). The PGT-MA live birth rate per embryo transferred is superior (45.6% vs 38.0%) indicating that testing for unrelated chromosomal gain/loss has value to discern a viable embryo; however, with 17.1% fewer live births due to the exclusion of viable unaffected embryos with test results that do not reflect the true potential of the embryo. With a prevalence of non-viable unaffected embryos of 62.0%, the predictive value is estimated to be 79.0% for an abnormal (non-transferable) chromosome test result correctly predicting no live birth (PPV), and 45.6% for a normal (transferable) chromosome test result correctly predicting a live birth event (NPV). The power of PGT-A to differentiate a viable embryo (diagnostic odds ratio, DOR), where the value 1 indicates no power, is estimated to be 3.150.

Table 1.

PGT-MA scenario summary for autosomal recessive (AR) and dominant (AD) monogenic conditions

| Model scenarios | (1) High success clinic | (2) Typical success clinic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women aged < 35 years | (1.1) Base | (1.2) Best | (1.3) Worst | (1.4) Optimised | (2.1) Base | (2.2) Best | (2.3)Worst | (2.4) Optimised |

| Diagnostic accuracy measures | ||||||||

| Prevalence of non-viable blastocysts % | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 62.0 | 62.0 | 62.0 | 62.0 |

| Negative predictive value (NPV) % | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 45.6 | 45.6 | 45.6 | 45.6 |

| Positive predictive value (PPV) % | 72.3 | 80.8 | 65.3 | 95.0 | 79.0 | 85.4 | 73.6 | 96.2 |

| Diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) | 3.924 | 6.319 | 2.818 | 28.778 | 3.150 | 4.911 | 2.337 | 21.425 |

| Unaffected viable blastocysts excluded % | 17.1 | 9.4 | 27.5 | 1.8 | 17.1 | 9.4 | 27.5 | 1.8 |

| Utility criteria: 1 T RR > 1, P < 0.05 | ||||||||

| Unaffected blastocysts required | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Blastocysts required for testing — AR/AD | 3/5 | 3/5 | 5/8 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 5/8 | 3/5 |

| Benefit — women avoiding a miscarriage* | 1 in 33 | 1 in 36 | 1 in 27 | 1 in 39 | 1 in 40 | 1 in 43 | 1 in 30 | 1 in 47 |

| Disbenefit — fewer women with a live birth | 1 in 8 | 1 in 15 | 1 in 6 | 1 in 82 | 1 in 7 | 1 in 13 | 1 in 5 | 1 in 72 |

| Utility criteria: 1 T RR > 1, P < 0.05, LB RR > 0.95 | ||||||||

| Unaffected blastocysts required | 5 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 2 |

| Blastocysts required for testing — AR/AD | 8/12 | 5/8 | 11/17 | 3/5 | 11/17 | 6/10 | 14/21 | 3/5 |

| Benefit — women avoiding a miscarriage* | 1 in 28 | 1 in 31 | 1 in 28 | 1 in 39 | 1 in 29 | 1 in 32 | 1 in 28 | 1 in 47 |

| Disbenefit — fewer women with a live birth | 1 in 25 | 1 in 22 | 1 in 27 | 1 in 82 | 1 in 26 | 1 in 22 | 1 in 23 | 1 in 72 |

*An overestimate; there is a bias in favour of PGT-MA caused by more women with more than 1 miscarriage with PGT-M

Fig. 1.

Scenario 2.1. The theoretical relative risk for PGT-MA compared to PGT-M with single embryo transfer. Live birth considering only up to 1 transfer attempt (1 T). Live births (LB), clinical miscarriages (CM) and transfer procedures (TS) for a full cycle (cumulative)

Given 2 unaffected embryos available for transfer and acting on test results for unrelated chromosomal abnormalities, approximately 1 in 40 women are likely to benefit by avoiding a clinical miscarriage, with the disbenefit of a reduction in the number of women with a live birth of around 1 in 7. It is estimated that 3 and 5 blastocysts are required to give at least an 80% chance of obtaining at least 2 unaffected embryos for an autosomal recessive and dominant monogenic condition respectively.

Given 7 unaffected embryos available for transfer and acting on test results for unrelated chromosomal abnormalities, approximately 1 in 29 women are likely to benefit by avoiding a clinical miscarriage, with the disbenefit of a reduction in the number of women with a live birth of around 1 in 26. It is estimated that 11 and 17 blastocysts are required to give at least an 80% chance of obtaining at least 7 unaffected embryos for an autosomal recessive and dominant monogenic condition respectively.

All the scenarios show that PGT-A marginally mitigates the risk of miscarriage at the cost of healthy live births. More embryos are required for testing for autosomal dominant conditions than recessive conditions, and the number of blastocysts required to marginalise the deficit in healthy live births due to PGT-A could be greater than might be typically expected from a first stimulated cycle where the female partner is less than 35 years old.

In conclusion, given that a first PGT-M treatment cycle is likely to be performed for couples where the female partner is younger than 35 years, acting on test results for unrelated chromosomal abnormalities (PGT-A) is likely to marginally mitigate the risk of miscarriage at the cost of healthy live births. In order to ensure the detriment to the cumulative live birth rate is marginal, it is likely that large numbers of blastocysts (more for dominant conditions than recessive conditions) will be needed if PGT-A is to be combined with PGT-M, which could make the practice of accumulating embryos from more than 1 stimulated cycle before analysis more likely. The primary objective of preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic disorders is to avoid having a child with a serious monogenic condition and PGT-M without PGT-A is preferred. Experimental clinical non-selection studies are needed to assess the potential detrimental effect of combining PGT-M with PGT-A.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contribution

The author is responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Data availability

Supplementary file provided.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Verlinsky Y, Cieslak J, Ivakhnenko V, Evsikov S, Wolf G, White M, Lifchez A, Kaplan B, Moise J, Valle J, Ginsberg N, Strom C, Kuliev A. Preimplantation diagnosis of common aneuploidies by the first- and second-polar body FISH analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1998;15:285–289. doi: 10.1023/a:1022592427128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braude P, Pickering S, Flinter F, Ogilvie CM. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:941–953. doi: 10.1038/nrg953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scriven PN, Bossuyt PM. Diagnostic accuracy: theoretical models for preimplantation genetic testing of a single nucleus using the fluorescence in situ hybridization technique. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:2622–2628. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Montfoort A, Carvalho F, Coonen E, Kokkali G, Moutou C, Rubio C, Goossens V, De Rycke M. ESHRE PGT Consortium data collection XIX-XX: PGT analyses from 2016 to 2017. Hum Reprod Open. 2021;2021(3):hoab024. 10.1093/hropen/hoab024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Scriven PN. Insights into the utility of preimplantation genetic testing from data collected by the HFEA. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:3065–3068. doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02369-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scriven PN. PGT-SR (reciprocal translocation) using trophectoderm sampling and next-generation sequencing: insights from a virtual trial. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:1971–1978. doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02174-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scriven PN. Carrier screening and PGT for an autosomal recessive monogenic disorder: insights from virtual trials. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2022;39:331–340. doi: 10.1007/s10815-022-02398-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barad DH, Albertini DF, Molinari E, Gleicher N. IVF outcomes of embryos with abnormal PGT-A biopsy previously refused transfer: a prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2022 Apr 12:deac063. Epub ahead of print. 10.1093/humrep/deac063 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Shen X, Chen D, Ding C, Xu Y, Fu Y, Cai B, Wang Y, Wang J, Li R, Guo J, Pan J, Zhang H, Zeng Y, Zhou C. Evaluating the application value of NGS-based PGT-A by screening cryopreserved MDA products of embryos from PGT-M cycles with known transfer outcomes. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2022 Mar 11. Epub ahead of print. 10.1007/s10815-022-02447-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Scriven PN. Towards a better understanding of preimplantation genetic screening and cumulative reproductive outcome: transfer strategy, diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness. AIMS Genetics. 2016;3:177–195. doi: 10.3934/genet.2016.3.177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uitenbroek DG: SISA Calculating binomial probabilities. https://www.quantitativeskills.com/sisa/distributions/binomial.htm . Accessed 28 March 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary file provided.

Not applicable.