Abstract

Objectives

Honey has been used for millennia as a treatment for covering wounds that are difficult to repair. Hippocrates already reported the benefits of honey with this type of treatment. The objective of this work is to evaluate the literature on the use of honey in cases as preventive as treatment complications after extractions, more specifically alveolar osteitis or alveolitis.

Material and Methods

A systematic literature review was carried out on PubMed, LILACS and Dimensions platforms, following PRISMA guidelines, to gain more knowledge on the topic. Due to the scarcity of articles on the topic, there are no restrictions regarding languages, publication dates or impact factor journal. Animal studies and reviews were excluded. Risk of bias was assessed through Review Manager Software 5.4.

Results

With simple, low-cost, and affordable medications, many of the complications after tooth extractions can be resolved more quickly and less painfully for patients with more significant difficulties, whether financial or access, to other treatments.

Conclusion

Honey is an effective prevention and treatment for alveolar osteitis.

Keywords: Honey, Dry socket, Osteitis, Oral surgery, Postoperative complications

Introduction

In 2019, at a meeting at the Royal Geographical Society in London, United Kingdom, bees were considered an essential living thing on Earth. The justification for this choice, carried out by wildlife experts and scientists, is the significance of pollination carried out by these animals; about 70% of world agriculture depends exclusively on bees. Bees are the only living beings that do not carry any kind of pathogen. Bees’ importance is so great that the great physicist Albert Einstein said: “If the bees disappear, the human being will have no more than four years of life” [1].

Bees are responsible for producing various products such as honey, royal jelly, pollen, propolis, and wax, among others [2]. Each of these bee products is used differently by man, and, from time to time, the indications of consumption and use end up being expanded.

Honey, the most common product made by bees, has always been used as food; human collection and use of honey has been described there for more than 15,000 years. It is produced by the nectar collected from flowers by the bees’ digestive enzymes and stored in honeycombs for later feeding. Since ancient Greece, honey has been used as a local antimicrobial that is placed under infected wounds, and challenging to heal. Hippocrates, the father of medicine, presents reports on the benefits of using honey for these purposes and its use in several other medicines [3].

Interest in honey and its local antimicrobial properties is increasing. There is a noticeable increase in the number of professionals who have been using honey as a cover for infected wounds that are difficult to heal is visible, and interest in the subject has increased in recent years, but still, most health professionals are unaware of this use of honey [4, 5].

Alveolar osteitis, or alveolitis, is a complication of extractions. This is a situation of loss of the socket’s protective clot, resulting in bone exposure, a frightening circumstance that, depending on geographic area and some local habits, in addition to gender, can occur in about 5% of patients undergoing tooth extraction [6, 7].

Several treatments and forms of prevention of alveolar osteitis, such as minimal surgical trauma, fine suture, postoperative care (not smoking, not using straws). Nonetheless, alveolar osteitis can occur in less traumatic surgeries and disciplined patients, and some studies, including more recent studies, have suggested that techniques and drugs reduce this incidence [8, 9]. Honey is one of those treatments.

The present study aims to provide a systematic review of the specific uses of honey in the treatment and prevention of post-tooth complications, particularly alveolar osteitis, a relatively common alveolar situation such as minimal surgical trauma, fine suturing, aftercare (no smoking, no straws) among others. However, even with less traumatic surgeries and disciplined patients, alveolar osteitis may arise, and some recent studies have suggested that techniques and drugs reduce this incidence [10–12]. Patients affected by this extremely painful complication often undergo contraindicated home treatments without no easy access to professional care. Honey can be a cheap and affordable alternative for these patients. In addition, a meta-analysis was carried out to assess the risk of bias of the studies involved and seek to confirm the effectiveness of honey in alveolar osteitis based in the relevant literature.

Material and methods

A bibliographic search was carried out on January 7, 2021, on the application of use of honey in alveolar osteitis in the Pubmed, LILACS, and Dimensions platforms. The research was carried out with the following strategy: honey AND (“alveolar osteitis” OR “third molar” OR (tooth AND extraction)).

Inclusion criteria were articles that used honey as a treatment or prevention of dry socket. Due to the shortage of articles on the topic, there are no restrictions on languages, publication dates or impact factor journal.

The use of antibiotics was an exclusion criterion to avoid biasing the effectiveness of honey therapy, since dry socket is not an infection, antitiotics use is not required [13]. All other bee products such as propolis and royal jelly were excluded as animal studies and reviews. This systematic review was carried out using the PRISMA guidelines [14].

Articles by the same author or center have been excluded to avoid risk of bias. Any disagreement regarding the inclusion or exclusion of articles was resolved by consensus between authors. In order to assess the studies’ quality, the risk of bias was assessed in accordance with the Cochrane handbook of systematic reviews of interventions. The results were used in Review Manager Software 5.4 (Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.4. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). The questions of the included studies are briefly explained as follows:

Random sequence generation (selection bias);

Allocation concealment (selection bias);

Blinding of participants and researchers (performance bias);

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias);

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

Selective reporting (reporting bias);

Other bias.

Results

After removing the duplicates, articles unrelated to proposed topic were excluded, and the use of other bee products such as propolis and royal jelly was excluded [15, 16]. Papers that evaluated the use of honey in animals were also be excluded [12, 17, 18] as, so literature reviews [5, 19].

One article was deleted because of its difficult accessibility [20]. Three articles were excluded because they were created in the same study center or with the same authors, and at the same time, it is not clear whether the sample examined was the same [21–23]. Although two Indian articles with the same surname are not the same authors, one has been excluded because it was written at the same study center, in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India [11]. A total of eight articles were included in this systematic review.

Characteristics of included studies

Forty articles were found on the topic of honey for repairing the socket after extractions. After excluding articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria, eight articles were included. Figure 1 exemplifies the workflow diagram for selecting the items.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for inclusion of articles

There was a great dichotomy as to the year of publication of the studies, two of which were conducted more than twenty years ago [24, 25], and both have a visible difference in scientific methodology that can be explained by the demands of the time. The guidelines for registering clinical trials, particularly the CONSORT guideline, did not become known until 1996, and many journals have been slow to adapt to this practice [26]. Other six studies of 2014 [27], 2016 [28] and four of 2019 [10, 29–31]. Two of these studies followed strict clinical trial protocols, presenting a low risk of bias [10, 31].

Cuban work was the only one that did not use a control group [24]. The substance used in the control groups varied between studies, using gauze soaked with saline and zinc oxide [27, 29], gauze moistened with saline [30], chlorhexidine 0.2% [10], Alvogyl ® [25] or just alveolar cloth [28, 31].

Four studies evaluated honey as a preventive measure against alveolitis and postoperative pain and edema levels [10, 28, 30, 31]. The other half of the studies specifically evaluated the treatment of alveolitis and the effectiveness of honey in this treatment [24, 25, 27, 29].

The uses of honey were also varied. In one study, the authors used gauze soaked in honey diluted in saline [29]. In two studies, a cotton swab was used to apply honey to the surface of the socket [10, 30]. Most of the studies, five, used intra-alveolar honey; the socket was rinsed with saline and a lot of honey was poured into the socket [24, 25, 27, 28, 31].

Some studies revealed the sex of the patients visited, three with a similar distribution between the sexes [10, 27, 28] and one with a more significant dominance for women [31]. Tables 1 and 2 summarize this reported information.

Table 1.

Comparison between studies in terms of location and number of patients in the control and experimental groups (studies in chronological order)

| City | Country | Experimental group | Control group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rivero Varona et al. | 1999 | Camagüey | Cuba | 40 | 0 | |

| Cheema et al. | 1999 | Lahore | Pakistan | 50 | 50 | Alvogyl |

| Passi et al. | 2014 | Lucknow | India | 40 | 30 | Zinc oxide |

| Ayub et al. | 2016 | Karachi | Pakistan | 50 | 50 | Cloth |

| Ansari et al. | 2019 | Navi Mumbai | India | 25 | 25 | Zinc oxide |

| Abu-Mostafa et al. | 2019 | Riyadh | Saudi Arabia | 57 | 43 | Chlorhexidine |

| Mokhtari et al. | 2019 | Tehran | Iran | 21 | 21 | Moistened gauze |

| Al-Khanati, Moudallal | 2019 | Damascus | Syria | 28 | 28 | Cloth |

Table 2.

Comparison between studies on intention, type of application, gender and age (studies in chronological order)

| Treatment or prevention | Application method | Gender | Age range | Mean age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rivero Varona et al. | Treatment | Intrasocket | > 15 | ||

| Cheema et al. | Treatment | Intrasocket | 18–41 | ||

| Passi et al. | Treatment | Intrasocket | 38M/32F | ||

| Ayub et al. | Prevention | Intrasocket | 51M/49F | 24–37 | 30.89 |

| Ansari et al. | Treatment | Moistened gauze | |||

| Abu-Mostafa et al. | Prevention | Swab | 48M/52F | 17–69 | 38.13 |

| Mokhtari et al. | Prevention | Swab | 4–9 | ||

| Al-Khanati, Moudallal | Prevention | Intrasocket | 8M/20F | 22.25 |

Meta-analysis

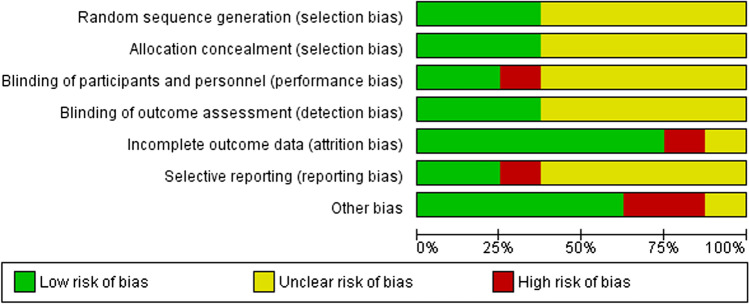

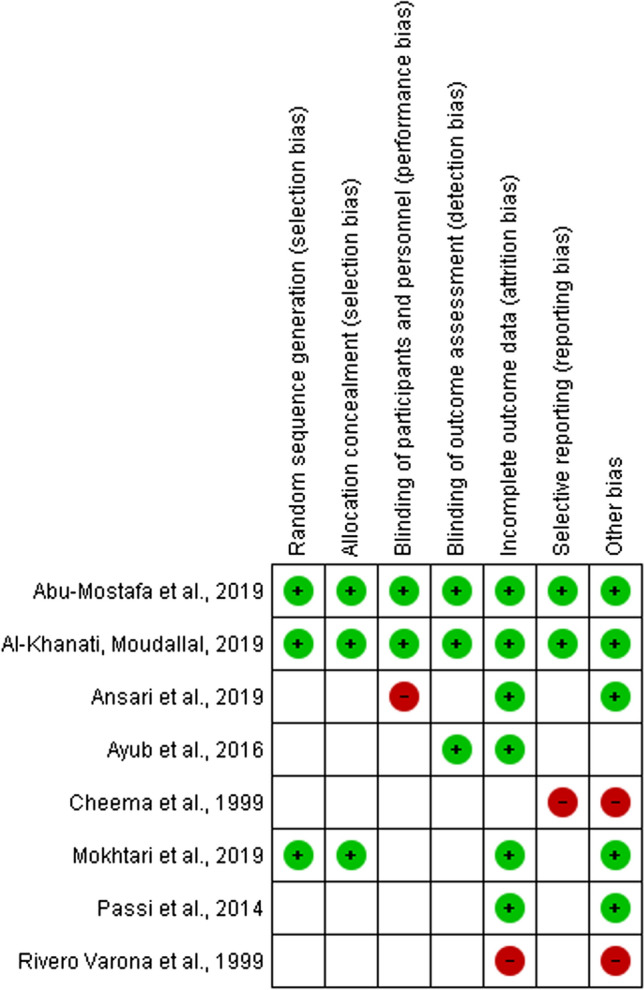

The risk of bias of the articles included in this study (Figs. 2 and 3) was analyzed using the RevMan 5.4® software (Cochrane Library). When analyzing the figures, it should be noted that some studies show a risk of bias in terms of both randomization and blinding of the studies.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias graph

Fig. 3.

Risk of bias summary

Then, the risk of bias graph and summary were created with the Cochrane Collaboration Tool [32], using the following domains:

Random sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participants and personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment data

Incomplete outcome data

Selective reporting

Other bias

Bias refers to factors that can systematically influence the observation and conclusions of the work and cause a change in the perception of the truth [33].

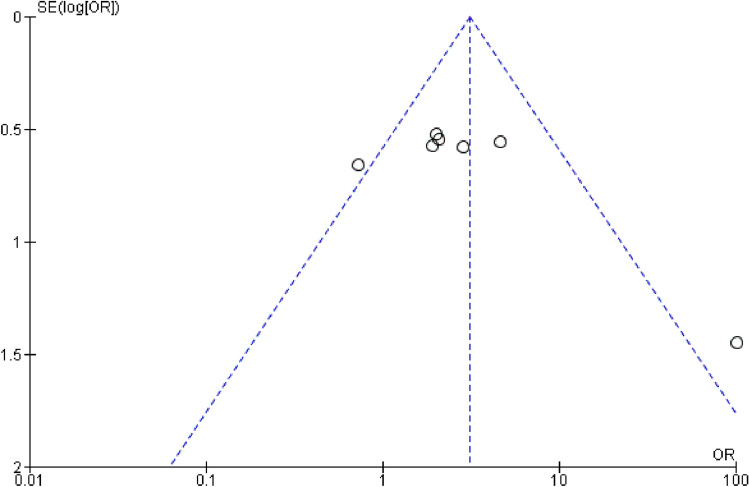

As shown in the summary of risk of bias (Fig. 3), two studies showed a low risk of bias overall [10, 31]. This means that these studies have been carried out adequately and systematically with high methodological quality. Two studies have the highest risk of bias [24, 25]. A forest plot (Fig. 4) demonstrates the effectiveness of honey in the treating alveolar osteitis. A funnel plot (Fig. 5) can be used to verify that the studies are heterogeneous, with the exception of two [24, 25]. This study was conducted with a 95%CI (p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot showing the effectiveness of honey in alveolar osteitis

Fig. 5.

Funnel plot showing the heterogenicity of the studies

Discussion

The combined studies applied honey in 316 patients and an additional 251 patients in the control group. Of these sockets to which honey was added, 160 were used for treatment; that is, the patients already had alveolar osteitis, and 156 were used for prevention. It was preferred to use intra-alveolar honey to treat alveolitis rather than using moistened gauze.

Honey is antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory [24, 27–31], moisturizer, and odorless [29]. Its broad-spectrum antimicrobial function (aerobic, anaerobic,gram-positive, and gram-negative bacteria, in addition to some fungi) [25, 27, 30] it is linked to the dehydration of bacteria due to its hygroscopic property, acid pH, and the presence of hydrogen peroxide, inactivating them [25, 27, 29–31]. Potassium in its composition dehydrates bacteria while hydrogen peroxide produces enzymes that make it the main antibacterial factor in honey. An acidic pH contributes to wound debridement and reduces local colonization [31]. The antimicrobial function of honey has been known since the nineteenth century [30]. Diluted honey can neutralize toxins from microorganisms [30]. Decreases the chance of using post-procedure antibiotic therapy [27].

Stimulates blood cells to produce cytokines, particularly interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor [27, 29–31]. The level of C-reactive proteins, a substance that occurs in tissue inflammation situations, decreases markedly with the use of honey [30].

Honey reduced inflammation, hyperemia, pain and discomfort in the patients [25, 29, 31]. This anti-inflammatory effect was also found in the absence of infection and has been demonstrated in histological studies [27, 31]. The decrease in the prostaglandin levels and increase in nitric oxide, as well as the modulation of adrenergic and muscarinic receptors, contribute to the anti-inflammatory function of honey [31]. Analgesia in the treatment of alveolitis can be prolonged by various applications of honey at daily intervals [24].

Studies have measured the size of the socket and compared its repair with the use of honey [29, 30], for debridement of necrotic tissue, which reduces the formation of scar tissue [25, 27, 29, 30]; the presence of aluminum sulfate and sucrose is responsible for this acceleration of the repair. Only one study did not report accelerated tissue repair [28].

Speeding up repair is one of the main reasons for using honey and other sucrose-rich products, such as white sugar [4, 27, 34]. In addition to glucose destroying bacteria, it acts as a substrate for macrophages, whose main function is phagocytosis. It also stimulates the proliferation of B and T lymphocytes [30]. Honeycomb is closely related to delaying honeycomb repair and this is why honey is becoming an excellent alternative [27].

Honey has antioxidant properties that act to avoid free radicals [27, 29] in addition to physical properties that allow the formation of an osmotic barrier, increasing local oxygenation [30, 31] and create a humid environment conducive to repair is beneficial, but without adhering to the surrounding tissue [27, 29]. The ability to form this osmotic barrier, that protects the region, is one factor responsible for its analgesic effect [25, 30]. Honey improved postoperative bad breath in patients due to its ability to form a mechanical barrier [25, 27] and due to the presence of formic acid [24].

It is considered a product with no side effects [29], non-toxic [24, 30], while other treatments used for alveolitis can have undesirable effects such as bone necrosis which can be produced with eugenol [29].

Its use in children is tolerated as it has a sweet taste that pleases the taste of these patients [30]. Although honey is better known as a food, it is also medicine and will be used worldwide for a long time [25, 27].

It has therapeutic potential in several areas such as periodontal diseases, oral ulcers, and other oral diseases, such as mucositis caused by radiotherapy and chemotherapy [27, 30]. There are even studies on the use of honey to decrease carious lesions because even though it is a substance rich in carbohydrates, it has anti-cariogenic activity [30]. There have been reports of bee products that are successfully used to disinfect dentinal tubules [35] and as an intraroot medication [36].

Quality control in honey production is essential to ensure that its composition and, consequently, its properties are not altered [24]. If this control is followed, honey is a non-toxic and already sterilized product that does not require any procedure after collection and storage [25, 31]. Methods of sterilizing honey change its properties with a consequent loss of antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, analgesic and healing functions.

One study compared the intra-alveolar use of honey with 0.2% chlorhexidine for the prevention of alveolar osteitis and concluded that honey was inferior to chlorhexidine in all items evaluated for pain, incidence alveolitis and halitosis, but the difference was not statistically significant. The authors concluded that the use of honey to prevent alveolitis needs further studies, mainly when compared to other substances already used and better studied, such as chlorhexidine [10]. This inefficiency of honey may be related to the form of application, which uses a swab instead of wet or intra-alveolar gauze, as in other studies.

Only two studies specified the plant used to make honey, the manuka flower [10, 31]. Manuka is a plant in the Leptospermum family, some species of which are endemic to Australia and others are also found in New Zealand and Southeast Asia. It is a type of monofloral honey that is not produced in the Americas and, if found, at exorbitant prices. The significant difference between Manuka honey and other types of honey is its high content of methylglyoxal [10, 31], a phytochemical component with a high antimicrobial power [37]. Another advantage of Manuka honey over other honeys is its high viscosity, which stays in the socket for longer [31].

The antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, analgesic and tissue repair accelerator properties honey are closely related to the origin of the honey, and different plants can produce honeys with distinct properties. [30]. The use of honey has been seen as a good option in the treatment and prevention of alveolar osteitis [27, 29, 30]; simples technology and inexpensive product [30].

None of the included studies compared two or more different types of honey, or different ways of applying honey to the socket (swabs, intra-alveolar, moistened gauze).

Conclusion

The use of honey in the treatment and prevention of alveolar osteitis is very efficient due to its antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, analgesic properties and as a repair accelerator besides its low cost and easy access. Intra-alveolar application appears to be more efficient than the use of swabs. Future studies are needed to compare different types of honey and the best way to use it.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare that there are no conflict or duality of interests of any author in this paper.

Ethical standard

All the procedures in this study were in accordance with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration, updated in 2013.

Informed consent

Informed consent is not needed since this is a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Concio CJ (2019) Bees declared to be the most important living being on earth. The Science Times. 2019. https://www.sciencetimes.com/articles/23245/20190709/bees-are-the-most-important-living-being-on-earth.htm

- 2.Wang Z, Ren P, Wu Y, He Q. Recent advances in analytical techniques for the detection of adulteration and authenticity of bee products—a review. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2021;38(4):533–49. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2020.1871081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raymond B, Sudjatmiko G. Standardization of honey application on acute partial thickness wound. J Plast Rekonstruksi. 2012;1(6):570–574. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franceschi C, Bricchi M, Delfrate R. Anti-infective effects of sugar-vaseline mixture on leg ulcers. Veins Lymphat. 2017;6(2):36–37. doi: 10.4081/vl.2017.6652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Namias N. Honey in the management of infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2003;4(2):68–69. doi: 10.1089/109629603766957022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Øyri H, Jensen JL, Barkvoll P, Jonsdottir OH, Reseland J, Bjørnland T. Incidence of alveolar osteitis after mandibular third molar surgery. Can inflammatory cytokines be identified locally? Acta Odontol Scand. 2021;79(3):205–11. doi: 10.1080/00016357.2020.1817546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolokythas A, Olech E, Miloro M. Alveolar osteitis: a comprehensive review of concepts and controversies. Int J Dent. 2010;2010:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2010/249073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang CH, Yang SH, Jen HJ, Tsai JC, Lin HK, Loh EW. Preventing alveolar osteitis after molar extraction using chlorhexidine rinse and gel: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Nurs Res. 2020;29(1):e137. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen YW, Chi LY, Lee OKS. Revisit incidence of complications after impacted mandibular third molar extraction: a nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abu-Mostafa N, Al-Daghamin S, Al-Anazi A, Al-Jumaah N, Alnesafi A. The influence of intra-alveolar application of honey versus Chlorhexidine rinse on the incidence of Alveolar Osteitis following molar teeth extraction. A randomized clinical parallel trial. J Clin Exp Dent. 2019;11(10):871–6. doi: 10.4317/jced.55743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh V, Pal U, Singh R, Soni N. Honey a sweet approach to alveolar osteitis: a study. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2014;5(1):31–34. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.140166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bahrami N, Shahabinejad H, Mohamadnia A, Shirian S, Seifi S, Seifi H, et al. The effects of nano-honey containing hydroxyapatite on socket healing. J Sci Tech Res. 2019;12(4):9373–9377. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansari A, Joshi S, Garad A, … BM-C clinical, 2019 U. A study to evaluate the efficacy of honey in the management of dry socket. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, Antes G, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):66. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alfahdawi I. Effect of propolis on fungal infection for denture wearers and dry socket introduction. Tikrit J Dent Sci. 2017;5:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skrobidurska D, Kubacka S, Posz A. Propolis application in stomatology for alleviation of postextraction pain. Czas Stomatol. 1975;28(10):973–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilyas M, Fahim A, Awan U, Athar Y, Sharjeel N, Imran A, et al. Effect of honey on healing of extracted tooth socket of albino wista rats article. Int Med J. 1994;22(5):422–425. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarraf P, Jaisani DP, Dongol MR, Shrestha A, Rauniar A. Effect of honey on healing process of extraction socket in rabbits. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2019;68(4):287–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saralaya S, Jayanth BS, Thomas NS, Sunil SM. Bee wax and honey—a primer for OMFS. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;25(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10006-020-00893-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elbagoury EF, Fayed NA. Application of “natural honey” after surgical removal of impacted lower third molar. Egypt Dent J. 1985;31(3):203–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soni N, Singh V, Mohammad S, Singh RK, Pal US, Singh R, et al. Effects of honey in the management of alveolar osteitis: a study. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2016;7(2):136–147. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.201354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prasad SD, Rajesh JM, Ashish S, Gajendra Prasad R. Effect of honey on rate of healing of socket after tooth Extraction in rabbits. J Pharm Sci Emerg Drugs. 2018;66:06. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikram R, Khan S, Cheema M. Role of honey as dressing material in oral cavity. Ann King Edward. 2000;6(4):404–405. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rivero Varona T, Maldonado M, Pérez M, Corrales M, Reyes O. Uso terapéutico de la miel en el tratamiento de las alveolitis. Arch méd Camaguey. 1999;3(4):43–47. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheema M, Khan S, Ikram R. Study of honey impregnated dressing and alvogyl as dressing materials for the management of alveolar osteitis. Proc SZPGMI. 1999;13(3–4):91–94. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans SJ, Keech A, Gebski V, Pike R. Interpreting and reporting clinical trials. A guide to the CONSORT statement and the principles of randomised controlled trials. Trials. 2008;9(1):66. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-9-27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Passi D, Singh D, Dutta S, Sharma S, Mishra S, Gupta C. Honey extract as medicament for treatment of dry socket: an ancient remedy rediscovered-case series and literature review. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2014;66:e1–e6. doi: 10.1007/s12663-014-0692-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayub T, Qureshi N, Kashif M. Effect of the honey of post extraction soft tissue healing of the socket effect of the honey of post extraction soft tissue healing of the socket. J Pak Dent Assoc. 2016;22(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ansari A, Joshi S, Garad A, Mhatre B, Bagade S, Jain R. A study to evaluate the efficacy of honey in the management of dry socket. Contemp Clin Dent. 2019;10(1):52–55. doi: 10.4103/ccd.ccd_283_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mokhtari S, Sanati I, Abdolahy S, Hosseini Z. Evaluation of the effect of honey on the healing of tooth extraction wounds in 4- to 9-year-old children. Niger J Clin Pract. 2019;22(10):1328. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_102_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Khanati NM, Al-Moudallal Y. Effect of intrasocket application of manuka honey on postsurgical pain of impacted mandibular third molars surgery: split-mouth randomized controlled trial. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2019;18(1):147–152. doi: 10.1007/s12663-018-1142-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedrosa Viegas de Carvalho AI, Silva VI, José Grande A III (2013) Medicina baseada em evidências Avaliação do risco de viés de ensaios clínicos randomizados pela ferramenta da colaboração Cochrane, vol. 18, Diagn Tratamento

- 33.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343(7829):66. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi CM, Nakao H, Yamazaki M, Tsuboi R, Ogawa H. Mixture of sugar and povidone-iodine stimulates healing of MRSA-infected skin ulcers on db/db mice. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;299(9):449–456. doi: 10.1007/s00403-007-0776-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vasudeva A, Sinha DJ, Tyagi SP, Singh NN, Garg P, Upadhyay D. Disinfection of dentinal tubules with 2% Chlorhexidine gel, Calcium hydroxide and herbal intracanal medicaments against Enterococcus faecalis: an in-vitro study. Singap Dent J. 2017;38:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.sdj.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sobhi MB, Manzoor MA. Efficacy of camphorated paramonochlorophenol to a mixture of honey and mustard oil as a root canal medicament. J Coll Phys Surg Pak. 2004;14(10):585–588. doi: 10.2004/JCPSP.585588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Majtan J, Klaudiny J, Bohova J, Kohutova L, Dzurova M, Sediva M, et al. Methylglyoxal-induced modifications of significant honeybee proteinous components in manuka honey: possible therapeutic implications. Fitoterapia. 2012;83(4):671–677. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]