Abstract

We discovered and characterized a temperate transducing bacteriophage (Ba1) for the avian respiratory pathogen Bordetella avium. Ba1 was initially identified along with one other phage (Ba2) following screening of four strains of B. avium for lysogeny. Of the two phage, only Ba1 showed the ability to transduce via an allelic replacement mechanism and was studied further. With regard to host range, Ba1 grew on six of nine clinical isolates of B. avium but failed to grow on any tested strains of Bordetella bronchiseptica, Bordetella hinzii, Bordetella pertussis, or Bordetella parapertussis. Ba1 was purified by CsCl gradient centrifugation and was found to have an icosahedral head that contained a linear genome of approximately 46.5 kb (contour length) of double-stranded DNA and a contractile, sheathed tail. Ba1 readily lysogenized our laboratory B. avium strain (197N), and the prophage state was stable for at least 25 generations in the absence of external infection. DNA hybridization studies indicated the prophage was integrated at a preferred site on both the host and phage replicons. Ba1 transduced five distinctly different insertion mutations, suggesting that transduction was generalized. Transduction frequencies ranged from approximately 2 × 10−7 to 1 × 10−8 transductants/PFU depending upon the marker being transduced. UV irradiation of transducing lysates markedly improved transduction frequency and reduced the number of transductants that were lysogenized during the transduction process. Ba1 may prove to be a useful genetic tool for studying B. avium virulence factors.

The study of temperate phage that infect pathogenic bacteria has provided numerous insights into the virulence of the host bacterium. The role of a temperate phage in virulence can be quite direct, in that some temperate phage carry toxin genes required for the host bacterium (lysogen) to cause disease (5, 26, 38, 39). In other cases, lysogeny affects virulence in more subtle ways that have to do with cell surface alterations (2, 3, 28, 34). Mutations to phage resistance often affect virulence properties by altering the cell surface, rendering the bacterium impaired not only in its ability to interact with phage but also with the host (8, 9, 30, 35). In addition to providing insights into the pathogenic process, temperate phage are often found to be generalized transducing phage (31). Such transducing phage provide valuable tools to characterize pathogenic bacteria genetically, especially in those pathogens where the means for genetic exchange via other mechanisms are limited (17, 18).

Bordetella avium causes bordetellosis, an upper respiratory tract disease in birds. Commercially raised turkeys are particularly susceptible (33). The disease involves colonization of the trachea, resulting in the death of ciliated tracheal cells. Experimentally infected birds normally recover after several weeks (36), but naturally infected birds are subject to a variety of secondary infections which cause severe economic losses in all poultry-producing regions of the world (33). The virulence-associated factors of B. avium are not well defined.

In this communication, we report the discovery of a B. avium temperate transducing phage (Ba1). We determined the host range of the phage and its biochemical and physical properties. Also, we characterized the nature of the Ba1 prophage state. In addition, we present evidence that transduction is generalized, having successfully transduced five randomly chosen insertion mutations. Finally, we identify procedures to increase transduction frequency and reduce lysogenization of transductants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

Bacteria and bacteriophage used in this study are listed in Table 1. B. avium and Bordetella hinzii broth cultures were grown at 37°C with shaking in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (Difco) as described previously (37). BHI agar plates consisted of BHI broth with 1.5% agar added. Soft agar for preparing top-agar lysates contained 0.7% agar. Bacteria to be phage infected were grown overnight to stationary phase. The preparation of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) indicator agar and minimal medium for B. avium has been previously described (37). Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis were maintained on Bordet-Gengou agar (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) with 15% sheep's blood. Phage sensitivity spot tests with these two strains employed a minimal medium (Stainer-Scholte) described by Hewlett and Wolff (16).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial and bacteriophage strains

| Strain | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| B. avium | ||

| 197N | Parental strain; relevant phenotype: Ba1s Ba2s Nalr Strs Lac− Kans Mot+ Hag+ | 37 |

| 197N2 | Spontaneous streptomycin-resistant mutant of 197N | This study |

| G145 | 197N except hag::mini-Tn5lacZ2 Hag− Kanr Lac+ | This study |

| G146 | 197N except mot::mini-Tn5lacZ2 Mot− Kanr Lac+ | 37 |

| 1B1 | 197N with random insertion (Ω1) using mini-Tn5 | This study |

| 1B4 | 197N with random insertion (Ω2) using mini-Tn5 | This study |

| 1B5 | 197N with random insertion (Ω3) using mini-Tn5 | This study |

| AP21 | 197N lysogenized by Ba1 | This study |

| GOBL271a | Strain screened for temperate phage (Ba1 and Ba2, sensitive) | 15 |

| 35086 | Strain screened for temperate phage (lysogenic for Ba2; resistant to Ba1 and Ba2) | ATCCb |

| Wampler | Strain screened for temperate phage (lysogenic for Ba1; Ba2 sensitive) | 22 |

| F247-P4164 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 sensitive | J. K. Skeeles |

| F242-95-950 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive | J. K. Skeeles |

| F241-95-931 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 sensitive | J. K. Skeeles |

| F243-P4485 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 sensitive | J. K. Skeeles |

| TR96-1212 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive | M. Blakeley |

| Ba169 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 sensitive | 19 |

| Ba198 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 sensitive | 19 |

| Ba177 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive; lysogenic | 19 |

| Ba002 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 sensitive | 19 |

| B. hinzii | ||

| Ba008 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive | Y. M. Saif |

| B. bronchiseptica | ||

| 17640 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive | 23 |

| 110NH | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive | 4 |

| 110H | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive | 4 |

| R-5 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive | 6 |

| Romark | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive | 24 |

| 87 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive | 4 |

| 64-C-0406 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive | Laboratory collection |

| JS34682 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive | 24 |

| BB213 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive | E. Hewlett |

| BB361 | Clinical isolate; Ba1 insensitive | 24 |

| B. pertussis 388 | Ba1 insensitive | 40 |

| B. parapertussis 253 | Ba1 insensitive | 25 |

| Bacteriophage | ||

| Ba1 | Wild type; isolated from B. avium strain Wampler | This study |

| Ba1c1 | Clear-plaque mutant of Ba1 | This study |

| Ba2 | Temperate B. avium phage isolated from ATCC strain 35086 | This study |

GOBL271 is derived from the same lineage as 197N (i.e., the parental strain of both is 197 [14]). This relationship was unknown at the time of screening for bacteriophage.

American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.

Preparation of Ba1 lysates for phage purification.

A portion of an overnight culture of B. avium 197N (typically 0.2 ml containing approximately 109 CFU) was mixed with a portion of a Ba1 lysate in a 15-ml test tube to produce a ratio of approximately 10−4 PFU: 1 CFU in a total volume of 0.3 ml. After a 20-min adsorption at 37°C, equal volumes (3 ml each) of soft agar and BHI broth were added, and the contents were mixed and poured onto a freshly made BHI agar plate. After a 10- to 11-h incubation period at 37°C, lysates were harvested by scraping the soft agar layer into a 40-ml centrifuge tube, adding approximately 0.2 ml of CHCl3, and vigorously mixing the contents on a vortex mixer for 30 s. Following a 20-min incubation at room temperature, agar and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 7,800 × g for 10 min. The resulting supernatant, referred to as crude lysate, had an average titer of approximately 5 × 109 PFU/ml (titering was performed essentially as for lysate preparation except that 3 ml of soft agar overlay was employed with serial dilutions of the lysate in 0.15 N NaCl). The addition of either MgCl2 or CaCl2 during adsorption had no effect upon the resulting titer. For further purification, phage were isolated from the crude lysate by centrifugation for 3 h at 31,200 × g. The resulting phage pellet was resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl–5 mM MgCl2 (λ-dil [10]), and the phage was isolated on a CsCl step gradient.

Phage isolation and nucleic acid extraction and manipulation.

An eight-step 17-ml CsCl gradient (41) subjected to centrifugation for 20 h at 116,000 × g in a Beckman SW28 rotor was used to estimate the buoyant density of Ba1 (ca. 1.55 g/ml), and a working gradient was established that consisted of three steps (1.36 g/ml, 1.50 g/ml, and 1.60 g/ml). The three-step gradient produced a well-isolated, readily visible phage band when approximately 1011 PFU were applied to the gradient. Needle aspiration of the band resulted in the recovery of an average of 75% ± 15% of the PFU applied to the gradient. Phage DNA was extracted as indicated for bacteriophage λ (24). Chromosomal and plasmid DNA was isolated as described for Escherichia coli (32). Restriction endonuclease digestion and agarose gel electrophoresis were performed as described by Davis et al. (10). DNA probes were isolated from agarose gels and then labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) as described by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim). Transfer of DNA to nitrocellulose was accomplished as directed by Maniatis et al. (23), and bands were detected as directed in the DIG high-prime DNA labeling and detection starter kit II (Boehringer Mannheim).

Electron microscopy.

Phage morphology measurements were conducted using CsCl purified phage. For contour length phage genome measurements, dilutions of phage DNA (extracted as directed by Dykstra [12]) were mixed with dilutions of purified pBR322 DNA (used as a size standard). These mixtures were placed on Formvar-coated grids and treated as described by Dykstra (12). Grids were examined with a Philips 410 transmission electron microscope. Contour lengths were determined for 10 full-length phage genomes using a map measure and were compared to the lengths of relaxed forms of pBR322.

Immunological techniques.

Antibody to Ba1 was raised by injection of a New Zealand White rabbit with approximately 1011 PFU of CsCl-purified phage in complete Freund's adjuvant. Six monthly booster doses of approximately 1010 PFU in incomplete Freund's adjuvant were given, and blood was withdrawn biweekly. The neutralization constant (K) value (42) of the antiserum after 2 months was stable at approximately 470 min−1.

Genetic techniques.

Coreversion analysis of a motility-negative (Mot−) mini-Tn5lacZ insertion mutant (strain G146 [Table 1 and reference 37]) that was phenotypically Lac+ on X-Gal plates was accomplished by first patching 20 colonies into a 0.35% soft agar layer on BHI agar plates. This was followed by examination of the plates after 48 h at 31°C for flares of motile revertants surrounding the original site of inoculation. Twenty independently isolated, motile revertants were examined for their Kan and Lac phenotype. All were Kans, Lac− and Mot+.

Transduction experiments were carried out with donor strains that had mini-Tn5 insertions (11). Recipient strains were grown overnight in BHI broth, and 0.2 ml of that culture was mixed with 0.1 ml of serially diluted crude phage lysate (average titer 5 × 109 PFU/ml) to produce a range of ratios from approximately 0.1 to 0.001 PFU/CFU in 10-fold increments. After a 20-min adsorption period at 37°C, the mixtures were diluted with 1.0 ml of BHI broth containing 0.1 M sodium citrate, and the bacteria were isolated by a brief centrifugation. The bacterial pellets were resuspended in 1.0 ml of the same medium and were incubated with shaking for 1.0 h at 37°C. After this incubation (to allow phenotypic expression of the neoR gene in mini-Tn5), cells were reisolated by centrifugation, and each cell pellet was resuspended in 0.15 N NaCl (0.1 ml). Each suspension was plated on BHI agar containing 40 μg of kanamycin/ml).

UV irradiation of phage lysates was accomplished using a General Electric G8T5 UV bulb and exposing approximately 12 ml of freshly prepared crude lysate (diluted to give approximately 2 × 109 PFU/ml in 0.15 N NaCl) in the bottom of a plastic petri plate. Ergs/mm2 were calculated using a Blak-Ray model J225 UV light monitor.

Ba1 lysogens of strain 197N were isolated by first spotting a drop of Ba1 phage lysate onto a lawn of strain 197N. After 8 h of incubation at 37°C, material from the turbid area where Ba1 had been spotted was streaked to obtain isolated colonies. Such isolates were defined as lysogens by (i) their resistance to lysis by Ba1 in cross-streaking tests (32) and (ii) their ability to produce phage as detected by the presence of PFU in supernatants from broth cultures. Lysogeny was confirmed physically by DNA hybridization using DNA from CsCl-purified phage as a probe.

Hydroxylamine mutagenesis of Ba1 to produce clear plaque mutants was accomplished essentially as described previously for λ phage (10). Pilot experiments revealed that hydroxylamine exposure at 37°C for 15 h produced the largest proportion of clear plaque mutants.

Spontaneous streptomycin-resistant mutants (Strr) were isolated by plating approximately 1010 CFU of strain 197N on BHI agar medium containing 50 μg of streptomycin/ml and were single-colony purified. Random insertion mutants and the hemagglutination defective (Hag−) insertion mutant (strain G145 [Table 1]) were obtained as described by Temple et al. (37). The Hag− mutant contained mini-Tn5lacZ2 (11) and was phenotypically Lac+ on X-Gal-containing agar. The random insertion mutants contained mini-Tn5Km2 (11).

Statistical analysis.

Means, the standard deviation of the means, and the statistical significance of mean differences (using Student's t test) were determined with the aid of the statistical package included with Microsoft Excel, version 4.0. P values of <0.05 were taken as significantly different.

RESULTS

Discovery.

Ba1 was discovered along with another B. avium temperate phage (Ba2) in a screen that involved cross-spotting supernatants from four B. avium strains (197N, GOBL271, ATCC 35086, and Wampler [Table 1]) onto lawns of each of the strains. Supernatants from broth cultures of the ATCC 35086 strain and the Wampler strain produced plaques on our laboratory B. avium strain, 197N. The Wampler phage was designated Ba1, and the ATCC 35086 phage, Ba2. Both phage appeared to be temperate, judging from their turbid plaques. Also, both phage were morphologically indistinguishable when viewed in the electron microscope (data not shown). However, lysogens constructed from each phage in strain 197N were heteroimmune and were distinguishable by other criteria (e.g., plaque morphology [our unpublished observations]). Ba1 was the only phage found to transduce via allelic replacement (described in more detail below) and was consequently chosen for further study.

Host range.

A spot test, in which at least 108 PFU of Ba1 (in approximately 20 μl) was dispensed onto lawns of Bordetella bronchiseptica, B. pertussis, B. hinzii, and B. parapertussis, was used to determine if they were sensitive to Ba1-mediated lysis. None of the species tested (Table 1) showed any evidence of sensitivity to Ba1. However, six of nine B. avium strains, obtained from clinical cases of bordetellosis (Table 1), were sensitive to Ba1 in the spot test. (Ba1 was subsequently shown to form plaques on these strains with a plaquing efficiency similar to that seen with strain 197N.) Of the three resistant strains, one (Ba177) appeared to be lysogenic for a bacteriophage morphologically similar to Ba1, raising the possibility that resistance in this strain was due to immunity or to superinfection exclusion (2). However, no experiments were performed to confirm this possibility.

Morphology and genome length of CsCl-purified phage.

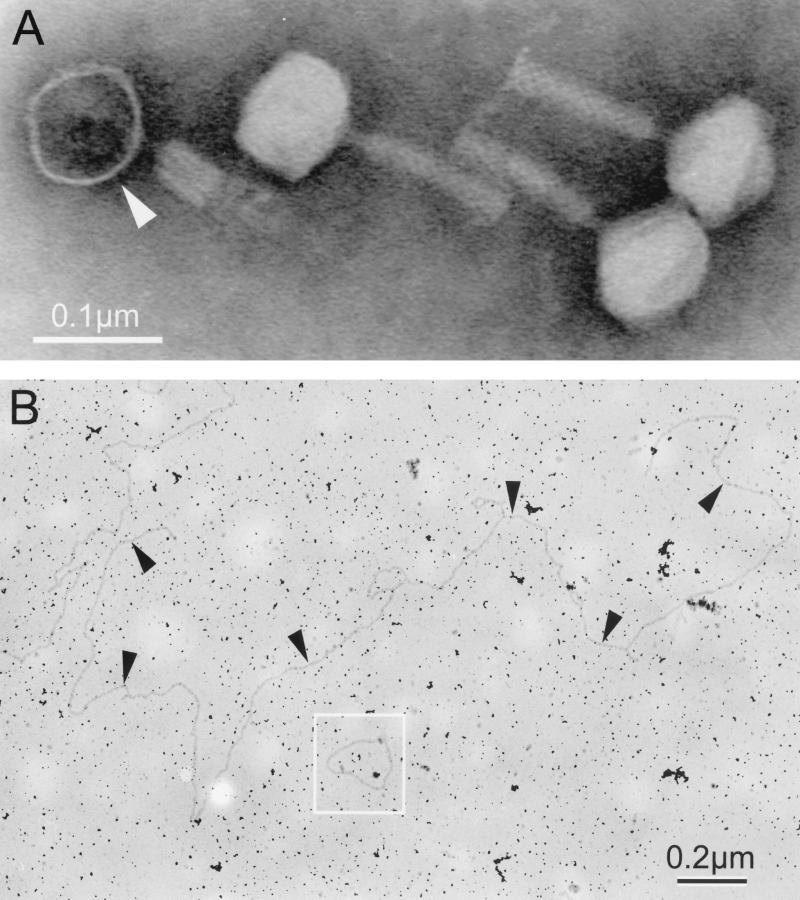

Measurements of 10 virions negatively stained and examined via transmission electron microscopy produced the following morphological measurements: (i) head size, measured parallel and perpendicular to the tail, was 55 ± 4 nm and 53 ± 2 nm, respectively; (ii) extended tail length was 85 ± 5 nm; and (iii) extended tail width was 14 ± 2 nm. Electron microscopy further revealed that the phage had a contractile, sheathed tail and faintly visible short tail fibers (Fig. 1A). The length of the double-stranded, linear DNA phage genome was determined by contour length measurements using pBR322 (in its relaxed circular form) as a size standard (Fig. 1B). Measurements of 10 phage genomes produced a length corresponding to a size of 46.5 ± 0 kb. This size is similar to size estimates based on electrophoretic migration of phage DNA digested with three different restriction endonucleases (XhoI, HindIII and EcoRI), which gave an average size of 48.6 ± 2.0 kb (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

(A) Transmission electron micrograph of negatively stained Ba1 phage particles. One phage (arrowhead) appears to have an empty head. (Note its electron-darkened head and contracted tail sheath exposing the inner tail core.) (B) Transmission electron micrograph of Ba1 DNA prepared from purified phage as described in Materials and Methods. Arrowheads denote a single linear genome. The relaxed form of pBR322 DNA (4.36 kb) was used as a size standard (box).

Ba1 prophage state.

Ba1 lysogeny was stable in the absence of external reinfection, as demonstrated by the growth of a 197N lysogen for over 25 generations in the presence of Ba1 antiserum sufficient to eliminate all detectable external phage (K = 47 min−1). Cultures were maintained in logarithmic growth by periodic dilution. Examination of 100 isolated colonies at the beginning and at the end of the experiment for Ba1 production and Ba1 immunity revealed that all 200 colonies examined were lysogenic. From the foregoing, we concluded that Ba1 formed a true lysogen rather than existing as a pseudolysogen (produced as a result of a persistent infection and exemplified by certain filamentous phages [2]).

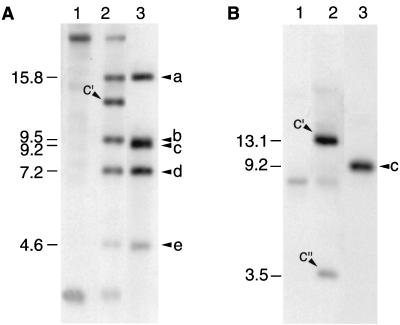

DNA hybridization studies that compared bacterial DNA from four independently isolated lysogenic 197N strains, the nonlysogenic 197N strain, and vegetative Ba1 DNA strongly suggested that the phage genome was integrated into the chromosome or other stable host replicon (strain 197N has a single large plasmid) at a preferred site on both the host and phage. One such lysogen, identical to the other three examined, is shown in Fig. 2A. From the figure, it is evident that at least one vegetative phage band (the 9.2-kb c band in lane 3) was lost upon lysogeny, and at least one new band appeared in the lysogen (c′, lane 2). Whereas this might be consistent with phage circularization, the total molecular weight of the hybridizing bands in the lysogen was higher than that of the total phage DNA, implying some form of integration. When a portion of the vegetative phage c band (an EcoRI fragment internal to the NotI) was used as a hybridization probe rather than whole vegetative phage DNA, two new bands in the lysogen were clearly present (c′ and c" Fig. 2B). We propose that the vegetative c fragment contains an attachment site which is split in two during integration to produce the c′ and c" fragments in lysogens. The absence of the c" band in Fig. 2A is likely due to the low specific activity of the whole phage probe DNA. In fact, the c" band was seen when using the whole phage probe if longer radiographic exposure was employed in concert with shorter electrophoresis times (data not shown). These procedures increased sensitivity and reduced band diffusion, respectively. The nonlysogenic strain 197N contained some DNA similar to Ba1 (lane 1, Fig. 2A and B). This may represent cryptic (nonfunctional) phage DNA or DNA coincidentally similar to the phage. Attempts to induce Ba1 lysogens with UV irradiation or mitomycin C using standard techniques were unsuccessful (our unpublished results).

FIG. 2.

(A) An autoradiograph of NotI-digested chromosome and phage DNA that was hybridized with DIG-labeled vegetative Ba1 DNA. Lanes: 1, nonlysogenic strain (197N); 2, lysogenic strain (AP21); 3, vegetative Ba1. The numbers to the left denote the fragment sizes in kilobases of the bands lettered on the right. The letters (a to e) identify specific vegetative phage fragments. The c′ in the lysogen lane (2) denotes a new fragment in the lysogen not present in the vegetative phage. (B) An autoradiograph of NotI-digested chromosomal and phage DNA hybridized with a DIG-labeled EcoRI restriction endonuclease fragment internal to the vegetative Ba1 NotI c fragment. Lanes: 1, the nonlysogenic strain (197N); 2, lysogenic strain (AP21); 3, vegetative Ba1. The numbers to the left denote the molecular weights of the putative attachment site-containing bands (c in the vegetative phage, and c′ and c" in the lysogen) in kilobases.

Ba1-mediated transduction of markers at five randomly chosen loci.

In order to test whether Ba1 was a transducing phage, we first established the association of a motility mutation with a transposon insertion using a coreversion test (Materials and Methods). We then used the Mot− Kanr Lac+ mutant as a donor in transduction experiments. The recipient was a spontaneous streptomycin-resistant (Strr) mutant of strain 197N. Selecting for Kanr, we readily found Kanr transductants, all having the phenotype Strr Kanr Mot− Lac+, as opposed to the donor phenotype, Strs Kanr Mot− Lac+, or the recipient phenotype, Strr Kans Mot+ Lac−. Interestingly, the Ba2 phage, when tested in this manner, transduced the antibiotic resistance marker, but approximately half of the transductants were still Mot+. As stated earlier, we have not characterized Ba2 further. Subsequent transduction experiments using Ba1, a hemagglutination-defective (Hag−) Lac+ mutant, and three additional mutants with insertions at undefined locations supported the generalized nature of the transduction in that all five markers tested were transduced, albeit some at different (i.e., statistically distinguishable) frequencies than others (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Ba1 transduction frequencies of insertion mutations at various locia

| Donor strain | Locusb | Phenotype conferred | Transductants per PFU (avg ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| G145 | hag::mini-Tn5lacZ | Hag− Kanr Lac+ | 1.7 × 10−8 ± 2.2 × 10−8 |

| G146 | mot::mini-Tn5lacZ | Mot− Kanr Lac+ | 1.7 × 10−7 ± 2.9 × 10−8 |

| 1B1 | Ω1 | Kanr | 1.1 × 10−8 ± 1.0 × 10−8 |

| 1B4 | Ω2 | Kanr | 9.0 × 10−8 ± 8.7 × 10−8 |

| 1B5 | Ω3 | Kanr | 2.0 × 10−8 ± 2.1 × 10−8 |

Transductions were carried out using dilutions of crude lysates as described in Materials and Methods. Ba1 lysates were not UV irradiated. All transducing lysates had similar titers (average, 4.8 × 109 ± 3.7 × 109 PFU/ml). The alleles transduced at the two highest frequencies (mot and Ω2) were statistically distinct from the rest but not from each other.

The hag and mot mutations were conferred by mini-Tn5lacZ transcriptional fusions. All Kanr transductants (>100 tested) had the hemagglutination-negative (Hag−) or motility-negative (Mot−) phenotype of the donor (37). Also, the transductant colonies were blue (“Lac+”) on X-Gal-containing agar, as were the donors. Insertion mutants 1B1, 1B4, and 1B5 have random mini-Tn5 insertions. The insertion sites in these mutants were not mapped except to note that they were each inserted into restriction endonuclease fragments of a different size, as indicated by DNA hybridization studies (data not shown).

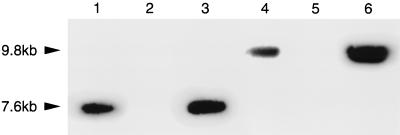

Physical evidence for a reciprocal exchange of markers in each of the five transductions came from DNA hybridization experiments using donor, recipient, and transductant DNA digested with EcoRI and probed with the Tn903 neoR gene (EcoRI does not cleave in neoR [11]). As was seen in all the transductants, including the two examples shown (mot::mini-Tn5 and hag::mini-Tn5 [Fig. 3]), donors and transductants had identical banding patterns. This was true also when donor and transductant DNA were digested with restriction endonucleases that cleaved at sites internal to the neoR gene (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Autoradiograph showing EcoRI restriction endonuclease fragments of donor and recipient strains in transduction experiments using a neoR gene probe as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes: 1, mot::mini-Tn5lacZ donor strain (G146); 2, recipient strain (197N2); 3, mot::mini-Tn5lacZ transductant; 4, hag::mini-Tn5lacZ donor strain (G145); 5, recipient strain (197N2); 6, hag::mini-Tn5lacZ transductant. Arrowheads denote the size of the reacting bands.

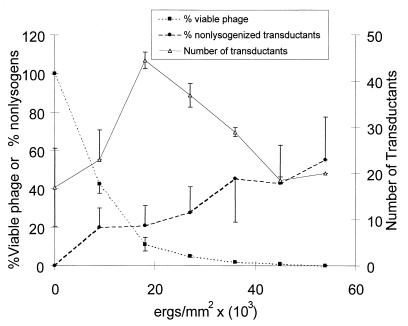

UV irradiation of transducing lysates.

One complication of Ba1 transduction was that transductants were frequently lysogenized. Ostensibly, this was because of the relatively high number of phage needed to get a successful transduction. Ba1 antiserum, employed during the transduction, was not effective at improving transduction frequency and eliminating lysogenization (our unpublished results). However, UV irradiation of Ba1, so as to drastically reduce the number of viable phage, not only reduced lysogen formation but also greatly increased transduction frequency (Fig. 4). The best transduction frequency with the fewest lysogens was found after exposure of Ba1 phage to approximately 4.2 × 104 ergs/mm2, resulting in approximately 99.9% killing of vegetative phage. A similar level of UV irradiation of a hydroxylamine-derived clear plaque Ba1 mutant (Ba1c1) was extremely effective at improving transduction frequency, and transductant lysogeny was eliminated (data not shown). However, unirradiated Ba1c1 lysates did not transduce at measurable frequencies.

FIG. 4.

Effect of UV irradiation on transduction parameters: viable phage, transduction frequency, and transductant lysogeny. Solid squares (■) denote the percentage of viable Ba1 after UV irradiation of a crude lysate grown on strain G146. Also plotted are the percentage of mot::mini-Tn5lacZ nonlysogenized transductants (●) and the number of transductants emerging from the irradiated lysate at each UV dose (▵). Points represent the averages of two experiments. Vertical bars denote standard errors of the means.

DISCUSSION

In this report we describe the discovery and characterization of Ba1, a temperate, transducing phage for B. avium. Ba1 was isolated along with one other temperate but distinctly different B. avium phage, Ba2. Ba1 was chosen for further study because it was capable of transduction via an allelic replacement mechanism. To our knowledge, Ba1 and Ba2 are the first reported phage discovered for this species of Bordetella.

Other members of the Bordetella genus are known to be infected by temperate phage (20, 21, 29). Both B. pertussis and B. bronchiseptica have temperate phage associated with them, and one phage for B. bronchiseptica has been reported to be a temperate transducing phage (M. Liu and J. F. Miller, Abstr. 97th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. B-321, 1997). However, none of the Bordetella phage have been used extensively as genetic tools, nor has an examination of the effect of lysogeny or phage resistance upon virulence been investigated.

Ba1 had an icosahedral head, a sheathed, contractile tail, double-stranded DNA, and a linear genome of a remarkably constant length. Ba1 most closely resembled members of the Myoviridae family morphologically (1). The stability of the prophage state was indicated by using Ba1-specific antiserum to show that lysogeny was maintained in the absence of external reinfection. Results of DNA hybridization experiments with four independently isolated 197N lysogens were consistent with phage circularization and integration at a preferred site in both phage and host replicons (7).

The most useful feature of Ba1 was its ability to transduce genetic markers. This property should allow the transfer of mutations between any Ba1-susceptible B. avium strains. Using nine random clinical B. avium isolates, we found that 67% were susceptible, but none of the other Bordetella species were lysed by Ba1. With regard to transduction frequency, some genetic markers were transduced at frequencies significantly different from those of others. A contributing factor to heterogeneity in marker-based transduction frequencies has been traced to features of the DNA surrounding the marker being transduced (e.g., chi sites [27]). Such features may be a contributing factor here. Also, we do not know the distance between the five transduced markers. We have assumed, since all five markers were chosen at random and all five were transduced, that the transduction is generalized. However, should the markers all turn out to be (coincidentally) closely linked, this conclusion would need to be reevaluated.

As with other transducing phage, transduction frequency was dramatically improved by UV irradiation of the transducing lysate (13). UV treatment reduces the number of viable phage, which are responsible for killing or lysogenizing transductants. With regard to the problem of transductant lysogenization, our Ba1 clear-plaque mutant (Ba1c1), if UV irradiated, eliminated the problem of transductant lysogeny. In addition to the ability of Ba1 to transduce, other properties associated with its interaction with B. avium (e.g., lysogeny or mutations to Ba1 resistance) may prove to be instrumental in better understanding B. avium pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Craig Altier for a critical reading of the manuscript and students from the Molecular Genetics classes at Drew University for their interest in and contributions to this project.

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R15 AI/OD3773 and AI-23695), the USDA (950 1934, 99-35204-7743), Drew University, and the State of North Carolina.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackerman H W, Berthiaume L, Jones L A. New actinophage species. Intervirology. 1985;23:121–130. doi: 10.1159/000149602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barksdale L, Arden S B. Persisting bacteriophage infections, lysogeny and phage conversions. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1974;28:265–299. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.28.100174.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barondess J T, Beckwith J. A bacteriophage virulence determinant encoded by lysogenic coli phage lambda. Nature. 1990;346:871–874. doi: 10.1038/346871a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bemis D A, Greisen H A, Appel M J G. Bacteriological variation among Bordetella bronchiseptica isolates from dogs and other species. J Clin Microbiol. 1977;5:471–480. doi: 10.1128/jcm.5.4.471-480.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betley M J, Mekalanos J J. Staphylococcal enterotoxin F1 is encoded by phage. Science. 1985;229:185–187. doi: 10.1126/science.3160112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns E H, Jr, Norman J M, Hatcher M D, Bemis D A. Fimbriae and determination of host species specificity of Bordetella bronchiseptica. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1838–1844. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1838-1844.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell A. Episomes. Adv Genet. 1962;11:101–145. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell G R O, Reuhs B L, Walker G C. Different phenotypic classes of Sinorhizobium meliloti mutants defective in synthesis of K antigen. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5432–5436. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5432-5436.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleary P P, Johnson L. Possible dual function of M protein: resistance to bacteriophage A25 and resistance to phagocytosis by human leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1977;16:280–292. doi: 10.1128/iai.16.1.280-292.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis R W, Botstein D, Roth J R. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis K N. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dykstra M J. A manual of applied techniques for biological electron microscopy. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garren A, Zinder N D. Radiological evidence for partial genetic homology between bacteriophage and host bacteria. Virology. 1955;1:347–376. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(55)90030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gentry-Weeks C R, Cookson B T, Goldman W E, Rimmler R B, Porter S B, Curtiss R., III Dermonectrotic toxin and tracheal cytotoxin, putative virulence factors of Bordetella avium. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1698–1707. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.7.1698-1707.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gentry-Weeks C R, Provence D L, Keith J M, Curtiss R., III Isolation and characterization of Bordetella avium phase variants. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4026–4033. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.4026-4033.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hewlett E, Wolff J. Soluble adenylate cyclase from the culture medium of Bordetella pertussis: purification and characterization. J Bacteriol. 1976;127:890–898. doi: 10.1128/jb.127.2.890-898.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodgson D A. Generalized transduction of serotype 1/2 and serotype 4b strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:312–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humphrey S B, Stanton T B, Jensen N S, Zuerner R L. Purification and characterization of USH-1, a generalized transducing bacteriophage of Serpulina hyodysenteriae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:323–329. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.323-329.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackwood M W, Saif Y M, Moorhead P D, Dearth R N. Further characterization of the agent causing coryza in turkeys. Avian Dis. 1985;29:690–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karataev G I, Moskivina I L, Ryabinina O P, Miller G G, Mebel S M, Lapaeva I A. Isolation and characterization of bacteriophage from the vaccine strain Tohama Phase I. Mol Genet Mikrobiol Virusol. 1988;4:22–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lapaeva I A, Mebel S M, Pereverev N A, Sinayshina L N. Bordetella pertussis bacteriophage. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1980;5:85–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luginbuhl G H, Cutter D, Campodonico G, Peace J, Simmons D G. Plasmid DNA of virulent Alcaligenes faecalis. Am J Vet Res. 1986;47:619–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musser J M, Bemis D A, Ishikawa H, Selander R K. Clonal diversity and host distribution in Bordetella bronchiseptica. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2793–2803. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2793-2803.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Musser J M, Hewlett E L, Peppler M S, Selander R K. Genetic diversity and relationships in populations of Bordetella species. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:230–237. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.1.230-237.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newland J W, Stockbine N A, Miller S R, O'Brien A D, Holmes R K. Cloning of Shiga-like toxin structural genes from a toxin converting phage of Escherichia coli. Science. 1985;230:178–181. doi: 10.1126/science.2994228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newman B J, Masters M. The variation in frequency with which markers are transduced by phage P1 is primarily a result of discrimination during recombination. Mol Gen Genet. 1980;180:585–589. doi: 10.1007/BF00268064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nnalue N A, Newton S, Stocker B A D. Lysogenization of Salmonella choleraesuis by phage 14 increases average length of O-antigen chains, serum resistance and intraperitoneal mouse virulence. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:393–402. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90026-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pereverzev N A, Lapaeva I A, Abdryrasulov S A, Sinyashina L N, Mebel S M, Zeitlenok L N. Ultrastructural organization of the bacteriophage isolated from Bordetella pertussis. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1981;5:54–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raleigh E A, Signer E R. Positive section of nodulation-deficient Rizobium phaseoli. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:83–88. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.83-88.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schicklmaier P, Schmieger H. Frequency of generalized transducing phages in natural isolates of the Salmonella typhimurium complex. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1637–1640. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1637-1640.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silhavy T J, Berman M L, Enquist L W. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skeeles J K, Arp L H. Bordetellosis (turkey coryza) In: Calnek B W, Barnes H J, Beard C W, McDougal L R, Saif Y M, editors. Diseases of poultry. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press; 1997. pp. 275–288. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spanier J G, Cleary P P. Bacteriophage control of antiphagocytic determinants in group A streptococci. J Exp Med. 1980;152:1393–1406. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.5.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spears P A, Temple L M, Orndorff P E. A role for lipopolysaccharide in turkey tracheal colonization by Bordetella avium as demonstrated in vivo and in vitro. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:1425–1435. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01963.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suresh P, Arp L H, Huffman E L. Mucosal and systemic humoral immune response to Bordetella avium in experimentally infected turkeys. Avian Dis. 1994;38:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Temple L M, Weiss A A, Walker K E, Barnes H J, Christensen V L, Miyamoto D M, Shelton C B, Orndorff P E. Bordetella avium virulence measured in vivo and in vitro. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5244–5251. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5244-5251.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uchida T M, Gill M, Pappenheimer A M., Jr Mutation in the structural gene for diphtheria toxin carried by temperate phage beta. Nature. 1971;233:8–11. doi: 10.1038/newbio233008a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waldor M K, Mekalanos J J. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science. 1996;272:1910–1914. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss A A, Hewlett E L, Meyers G A, Falkow S. Tn-5 induced mutations affecting virulence factors of B. pertussis. Infect Immun. 1983;42:33–41. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.33-41.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamamoto K R, Alberts B M, Benzinger R, Lawhorne L, Treiber G. Rapid bacteriophage sedimentation in the presence of polyethylene glycol and its application to large-scale virus purification. Virology. 1970;40:734–744. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(70)90218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zinder N D. Virus neutralization. In: Williams C A, Chase M W, editors. Methods in immunology. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1967. pp. 375–399. [Google Scholar]