Abstract

Spontaneous gas gangrene of lower limb is rare. It may complicate digestive cancer or neutropenia. We report a case of spontaneous gas gangrene of the lower limb complicating a rectal cancer, initially diagnosed as deep vein thrombosis. The diagnostic delay was fatal.

Keywords: delayed diagnosis, gas gangrene, rectal neoplasms

Spontaneous gas gangrene of the lower limb is a serious infection. Early diagnosis and management are essential to improve the prognosis. It should be considered in patient with digestive cancer who presents pain with local signs in the lower limb.

1. INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous or nontraumatic gas gangrene is a rare form of gangrenous disease. 1 It is a serious infection that usually occurs in immunocompromised patients. 2 Symptoms are common to several pathologies. The diagnosis may be delayed especially in the absence of a previous trauma. We report a case of spontaneous gas gangrene of the lower limb that was wrongly taken as thrombophlebitis.

2. CASE PRESENTATION

2.1. Case history and examination

A 43‐year‐old female patient, without comorbidities, was followed for locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the middle rectum, for 3 months. The carcinoma was classified T4N0M0, invaded the vagina, without any distant metastasis. Neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy was initiated, complicated by bone marrow aplasia, which required transfusions. She consulted for pain and functional impotence of the right lower limb, evolving for 3 days, without other associated signs.

On examination, the patient was febrile at 38°C. Hemodynamic parameters were stable. Unlike the left lower limb, the right lower limb was swollen, warm, and painful at palpation with a positive Homan's sign. There were no skin necrosis, bullae, or cutaneous crepitus. The femoral pulse was present, whereas, the popliteal and pedal pulses were weak. The abdomen was soft, depressible, and painless. The rectal examination revealed a tumor of 5 cm from the anal margin, which was painful.

2.2. Differential diagnosis, investigations, and treatment

Initially, laboratory tests showed a white blood cell count of 7700 elements/mm3 and a C‐reactive protein (CRP) of 6 mg/L. Hemoglobin was of 8.2 g/dl. The chest X‐ray was normal and the urinary cytobacteriological examination did not show urinary infection. A venous Doppler ultrasound of the lower limb was performed urgently, which did not reveal any thrombosis.

The diagnosis of thrombophlebitis of the right lower limb has not been discarded. The patient was put on curative doses of heparin, using a syringe pump, with monitoring the vital signs. After 48 h, a second venous Doppler ultrasound was scheduled.

Subsequently, the pain has become more pronounced in the right limb with the persistence of fever around 38.5°. On examination, the hemodynamic status remained stable but a tachycardia had appeared on the second day. There was an increased swelling, with the appearance of an erythematous plaque on the anterior side of the right thigh and a suspicion of crepitus above the knee.

Following these findings, an infectious investigation was started urgently. The biological assessment showed an increase in the white blood cell count from 7700 to 11,000 elements/mm3. The CRP remained negative. Renal function was preserved. Blood cultures were taken but were contaminated with Staphylococcus epidermis. At the same time a venous Doppler ultrasound was performed and did not show venous thrombosis. It showed diffuse deep collections in muscle compartments of the thigh.

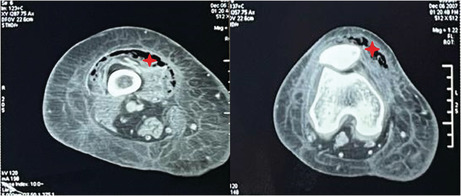

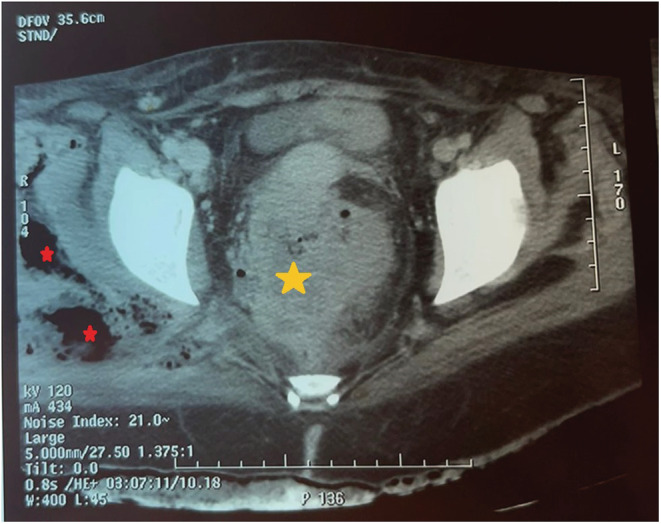

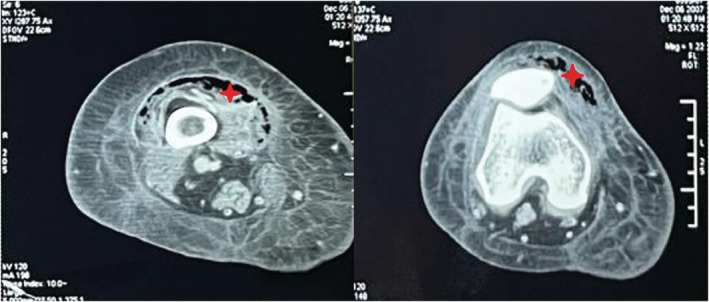

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and the lower limb was performed showing an abscessed and ruptured rectum tumor with purulent and gaseous flares extending to the right gluteal muscles (Figure 1) and right thigh (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

A pelvic slice of the abdominal computed tomography scan showing the abscessed rectal tumor (yellow star) and the gaseous infiltration of the deep muscles of the right gluteal region (red star).

FIGURE 2.

Computed tomography scan of the right lower limb showing a gaseous infiltration of the anterior thigh muscle compartment reaching the knee (red star).

The patient was put on empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy targeting digestive tract bacteria, consisting of cefotaxime, metronidazole, and gentamicin. The patient was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit. He was conditioned for an urgent operation. During conditioning, the patient was put on vasoactive drugs for hemodynamic distress, with a fall in blood pressure from 100/70 mmHg to 90/60 mmHg and a tachycardia >120 beats per minute.

The patient was operated on: An elective colostomy was performed to divert the feces. On the right thigh, a fasciotomy was performed with evacuation of the pus and wide excision of the necrotic tissue. Drainage in contact with the excised tissue was performed. Bacteriological samples were not taken and this attitude was not justified. The hemodynamic status further deteriorated intraoperatively, necessitating a gradual increase in the doses of vasoactive drugs. The intervention lasted 2 h in total.

2.3. Outcome and follow‐up

The postoperative course was marked by the onset of septic shock refractory to antibiotics, vascular filling, and vasoactive drugs. The patient died 20 h after surgery.

3. DISCUSSION

Our case is with great importance because it highlights a serious disease entity, often overlooked by clinicians because of its rarity.

Gas gangrene of the lower limb or necrotizing clostridial infection is rare but constitutes a serious disease. 1 Approximately 70% of these infections are of traumatic origin and 30% of nontraumatic origin, also called spontaneous. 1 Factors that predispose to spontaneous gangrene are mainly the presence of digestive cancer or neutropenia. 2 , 3 The occurrence of spontaneous gangrene in a patient without these factors should prompt a search for digestive cancer. 3 This infection is commonly caused by commonly caused by Clostridium perfringens or Clostridium septicum. 3

In our patient's case, both risk factors were present: rectal cancer and recent chemotherapy‐induced bone marrow aplasia.

The clinical presentation is made of local signs such as pain, swelling of the limb, erythema, hemorrhagic bullae, skin necrosis, and subcutaneous crepitus. 4 , 5 The combination of these signs is not constant. 4 , 5 General signs may range from isolated fever to septic shock. 5 Some diagnostic pitfalls to be aware of are the absence of fever (40%), the absence of skin manifestations (25%), the attribution of pain to another local cause, and the attribution of systemic manifestations to another general cause. 1 Biological examinations may orientate the diagnosis by the presence of hyperleukocytosis, elevated CRP, and elevated creatinine in the absence of arterial hypotension. 6

For our patient, the discretion of the cutaneous signs at the beginning and the presence of a thrombogenic disease (Rectal cancer), the absence of hyperleukocytosis, biological inflammatory syndrome, or elevated creatinine, had diverted the attention of the clinicians toward another diagnosis: Deep vein thrombosis of the lower limb.

Deep vein thrombosis is one of the differential diagnoses of lower limb gangrenous disease. 7 D‐Dimer testing is not required if there is a strong clinical suspicion of thromboembolic disease 8 : A proximal venous Doppler of the lower limb should be performed. 9 If the proximal Doppler does not show the presence of deep vein thrombosis, the diagnosis cannot be eliminated and a venous Doppler ultrasound of the whole limb should be performed after 48–72 h. 9

In our patient's case, the absence of deep vein thrombus did not lead the clinicians to consider other diagnoses. The patient was put on curative doses of heparin for fear of progression to pulmonary embolism before the second venous Doppler.

Computed tomography scan of the lower limb can be of an important aid to diagnosis. It may show gas infiltration of the muscle compartments. 10 , 11 , 12 In the case of infected mid or lower rectal cancer, the evolution may be toward Fournier's gangrene of obvious clinical diagnosis, 13 or rarely toward gangrene of one of the lower limbs where a CT scan can be necessary to make the diagnosis. 10

The diagnosis was made late in our patient, after the local signs had worsened.

Therapeutic management is based on early surgical intervention consisting on excision of infected tissues and pus evacuation, appropriate antimicrobial treatment adapted after surgical bacteriological samples, and effective intensive care management managing sepsis signs or septic shock. 1 , 14 , 15 Colostomy stool diversion should be performed in cases of abscessed cancer to better control the infection. 13 , 16

The prognosis is poor, especially in cases of delayed diagnosis and treatment. 2 , 17 Mortality rate is about 70% of cases. 18

In our patient, the presentation of the gangrene was not atypical: An immunocompromised patient, with digestive cancer, consulting for fever, pain, and swelling of a lower limb and a painful rectal examination. An early abdominal and lower limb CT scan, just after the first venous Doppler ultrasound, could avoid the diagnostic delay, which was made at the stage of septic shock. The prognosis could be better for the patient.

4. CONCLUSION

Spontaneous gas gangrene of the lower limb is a serious infection with high mortality. Early diagnosis and management are essential to improve the prognosis. It should be considered as a matter of principle in any patient with digestive cancer who presents pain with local signs in the lower limb.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

All the authors participated in the design of the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Mohamed Farès Mahjoubi has drafted the work and contributed to the literature research. Bochra Rezgui has collected data. Aymen Mabrouk has substantively revised the work. Nada Essid and Laila Jedidi have made substantial contributions to the literature research. Mounir Ben Moussa has made substantial contributions to the conception of the work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors have no conflict of interests.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Our locally appointed ethics committee “Charles Nicolle Hospital local committee” has approved the work.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was not obtained from the patient because he died.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

Our study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None.

Mahjoubi MF, Rezgui B, Mabrouk A, Essid N, Jedidi L, Ben Moussa M. Spontaneous gas gangrene of the lower limb in a patient with rectal cancer: A fatal diagnostic pitfall. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10:e06311. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.6311

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data and supportive information is available within the article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Stevens DL, Bryant AE, Goldstein EJ. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. Infect Dis Clin North. 2021;35(1):135‐155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stevens DL, Musher DM, Watson DA, et al. Spontaneous, nontraumatic gangrene due to Clostridium septicum . Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(2):286‐296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bodey GP, Rodriguez S, Fainstein V, Elting LS. Clostridial bacteremia in cancer patients. A 12‐year experience. Cancer. 1991;67(7):1928‐1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McHenry CR, Piotrowski JJ, Petrinic D, Malangoni MA. Determinants of mortality for necrotizing soft‐tissue infections. Ann Surg. 1995;221(5):558‐563; discussion 563‐565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Muduli IC, Ansar PP, Panda C, Behera NC. Diabetic foot ulcer complications and its management—a medical college based descriptive study in Odisha, an eastern state of India. Indian J Surg. 2015;77(2):270‐274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wall DB, Klein SR, Black S, de Virgilio C. A simple model to help distinguish necrotizing fasciitis from nonnecrotizing soft tissue infection. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191(3):227‐231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Perkins JM, Magee TR, Galland RB. Phlegmasia caerulea dolens and venous gangrene. Br J Surg. 1196;83(1):19‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Messas E, Wahl D, Pernod G, Collège des Enseignants de Médecine Vasculaire . Management of deep‐vein thrombosis: a 2015 update. J Mal Vasc. 2016;41(1):42‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kitchen L, Lawrence M, Speicher M, Frumkin K. Emergency department management of suspected calf‐vein deep venous thrombosis: a diagnostic algorithm. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17(4):384‐390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carbonetti F, Cremona A, Carusi V, et al. The role of contrast enhanced computed tomography in the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis and comparison with the laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis (LRINEC). Radiol Med. 2016;121(2):106‐121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ruiz EF, Rahni DO. Is air an issue? A severe case of subcutaneous emphysema in an immunocompromised patient. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10(5):e05906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ben Ismail I, Hammami N, Zenaidi H, Rebii S, Zoghlami A. Clostridial abdominal wall gas gangrene secondary to sigmoid cancer perforation. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91(12):2851‐2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yoshino Y, Funahashi K, Okada R, et al. Severe Fournier's gangrene in a patient with rectal cancer: case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14(1):234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mwenibamba RM, Nteranya DS, Mukakala AK, et al. Medial thigh fasciocutaneous flaps for reconstruction of the scrotum following Fournier gangrene: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10(4):e05747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beji H, Bouassida M, Zribi S, Touinsi H. Ileal gastrointestinal stromal tumor causing mesenteric gangrene. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10(4):e05772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eray IC, Alabaz O, Akcam AT, et al. Comparison of diverting colostomy and bowel management catheter applications in Fournier gangrene cases requiring fecal diversion. Indian J Surg. 2015;77(2):438‐441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Menon B, Krishna M, Galagali A, Mehrotra S. Necrotising soft tissue infection in the twenty‐first century—a clinical and microbiological spectrum analysis. Indian J Surg. 2021;83(1):66‐71. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Srivastava I, Aldape MJ, Bryant AE, Stevens DL. Spontaneous C. septicum gas gangrene: a literature review. Anaerobe. 2017;48:165‐171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data and supportive information is available within the article.