Abstract

Purpose

We sought to explore the utility of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) in a poor prognosis group of women with few embryos available for transfer.

Methods

This was a retrospective matched cohort study examining records for first or second-cycle IVF patients with 1 to 3 blastocysts. The study group comprised 130 patients who underwent PGT-A on all embryos. The control group included 130 patients matched by age, BMI, and blastocyst number and quality who did not undergo PGT-A during the same time period.

Results

The live birth rate (LBR) per embryo transfer (ET) were similar in the PGT-A and control groups, and the spontaneous abortion (SAB) rate was the same (23%). However, we found a significantly higher LBR per oocyte retrieval in the control group vs the PGT-A group (43% vs 20%, respectively) likely due to the many no-euploid cycles in the PGT-A group. In a subgroup analysis for age, the similar LBR per ET persisted in women < 38. However, in older women, there was a trend to a higher LBR per ET in the PGT-A group (43%) vs the control group (22%) but a higher LBR per oocyte retrieval in the control group (31%) vs the PGT-A group (13%).

Conclusions

Overall, we observed a significant increase in LBR per oocyte retrieval in women in the control group compared to women undergoing PGT-A, and no difference in SAB rate. Our data suggests that PGT-A has no benefit in a subpopulation of women with few embryos and may cause harm.

Keywords: Preimplantation genetic testing, In vitro fertilization, Pregnancy, Low ovarian reserve

Introduction

Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) has been adopted into many clinical programs as an add-on to IVF. The theoretical argument underpinning widespread application of PGT-A relies on a series of assumptions. The primary assumption is that many embryo transfers fail or lead to miscarriage because of aneuploid embryos, so eliminating aneuploid embryos will improve IVF outcomes [1]. Theoretically, the benefits of PGT-A and euploid embryo transfer are to increase the live birth rate per embryo transfer, reduce the risk of miscarriage and shorten the time taken to conceive.

Relating to the procedure of PGT-A itself, another assumption is that a single trophectoderm (TE) biopsy of a few cells is representative of the whole TE, and that the TE ploidy reflects the chromosomal composition of the inner cell mass (ICM). However, it is well known that euploid/aneuploid mosaicism is common and biopsy of a few cells of a mosaic embryo could, by chance, result in a diagnosis of euploidy, aneuploidy or mosaicism [2]. Finally, when offering PGT-A clinically, one must also assume that the chromosomal complement of the embryo does not change (i.e. self-correct), an assumption that has also been called into question by animal studies demonstrating that the inner cell mass of mosaic embryos has the ability to eliminate aneuploid cells through apoptosis to become euploid [3, 4]. Therefore, discarding embryos diagnosed as aneuploid by PGT-A runs the risk of eliminating embryos that might have been capable of a normal live birth (false positive diagnosis). On the other hand, possible benefits of transferring an embryo diagnosed as euploid are reduction of the time to ongoing pregnancy and a reduced risk of a pregnancy that is likely to miscarry.

In practice, PGT-A cycles eliminate many potential embryo transfers because of an aneuploid, diagnosis. A higher pregnancy rate per embryo transfer may be observed with PGT-A tested embryos but if there are any false positive diagnoses, the cumulative pregnancy rate per cycle could be lower than the alternative of not testing [5]. In a large randomized controlled trial, PGT-A with transfer of euploid embryos was shown to be associated with a higher ongoing pregnancy rate (OPR) per embryo transfer in older women, though this benefit was not seen when OPR was analyzed per oocyte retrieval [6]. In one positive study, cumulative live birth rates were no different between PGT-A and controls although first embryo transfer live birth rates were higher in the PGT-A group [7]. In another study analyzing over 1200 women with 3 or more blastocysts, the cumulative live birth rate was significantly lower in PGT-A compared with controls [8].

In light of the variable results of the studies summarized above, the question arises as to which patients stand to benefit most from PGT-A and which patients may not benefit, or worse, may be harmed by unnecessarily discarding embryos that could become healthy pregnancies. Of particular interest is the subpopulation of patients with a small number of embryos, where a false positive PGT-A result would yield a disproportionate negative impact on live birth outcome. The objective of the present study was to compare pregnancy outcomes in a poor prognosis group of patients undergoing PGT-A with 3 or fewer blastocysts compared to a control group matched by age, BMI, and number of blastocysts who did not undergo PGT-A.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective matched cohort study examining records for first or second-cycle IVF patients who obtained 1 to 3 blastocysts in IVF cycles conducted in 2019 and 2020 and had embryo transfers up until April 2021. The study group comprised 130 patients who underwent PGT-A on all their embryos. The decision to undergo PGT-A was made between the patient and their physician. The control group included 130 patients matched by age, BMI, and blastocyst number who did not use PGT-A during the same time-period. The study was conducted with Research Ethics Board approval from Veritas IRB, study #2776. The cumulative clinical pregnancy and live birth rates included all fresh and frozen embryo transfers during the study period. Donor oocyte recipients were excluded, as were patients with endometriosis, 2 or more miscarriages, or mosaic embryos.

IVF protocol

IVF with ICSI was performed as previously described [9]. ICSI was completed in mHTF/10% (v/v) LGPS (LIFE Global Canada/Denmark) under sterile mineral oil. All ICSI for PGT-A patients was performed using polarized light imaging (Oosight, Hamilton-Thorne, Beverly MA USA) system for visualizing the spindle. The spindle was considered normally placed if within 26.5 degrees of the polar body [10]. If the spindle was in way of ICSI, the oocyte was rotated using the spindle for orientation at 6 or 12 o’clock. Patient embryos were cultured in the embryoscope time-lapse system and annotated for morphometric parameters daily. No morphometric parameters were analyzed for this particular study. Culture conditions were 37 Degrees C under 5.5% CO2 5.0% O2. Culture Media used was Life Global media supplemented with 10% (v/v) LGPS (LifeGlobal protein supplement), over laid with sterile gassed mineral oil. Blastocysts were assessed using the Gardner grading system [11] on days 5 and 6. All embryos for PGT-A were biopsied by one of five senior embryologists all having a minimum of 15 years. experience in biopsies (day 3 and day 5). Blastocyst was biopsied on day 5, if embryo was graded 2BB or higher, if not the embryo was allowed to grow over night. Day 6 cutoff for biopsy and cryopreservation was 3BB. Embryos were biopsied using a laser (Octax Laser, Vitrolife, Englewood USA) for assisted hatching. Embryos were pre-hatched on day 3 of culture to facilitate trophectoderm biopsy on day 5. For biopsy, the blastocyst was placed into a micro-drop of mHTF/10% LGPS (v/v) overlaid with warm gassed mineral oil. PVP (company) was used in aspiration pipette for control and to reduce sticking of cells. The embryo was held with a holding pipette (at the inner cell mass) while the biopsy pipette gently aspirated approximately 4–6 cells from the trophectoderm. The laser was used to loosen tight junctions between cells and a minimal quantity of laser shots was used. Once the embryo was biopsied, it was placed back into culture until it was vitrified within the next 3 h. The trophectoderm cells were placed into buffer solution provided by the genetics lab. Vitrification was performed using Irvine vitrification solutions (15% ethylene glycol/15% DMSO/20% HSA V/V) with HSV straws (FujiFilm Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana CA USA). Blastocysts were vitrified one per straw according to embryo biopsy so that embryo number and genetic results were always reconciled. Genetics results were received approximately 1 week after biopsy. PGT-A analysis was performed by Cooper (Livingston, NJ). At Cooper, PGT-A/SR samples were amplified using the standard PicoPlex Whole Genome Amplification method. Analysis was performed by Cooper’s proprietary AI algorithm (PGTai2.0) based on two simultaneous analysis approaches, SNP analysis and CNV analysis, with no manual interpretation. The limit of detection was 5 MB. Threshold for reporting mosaicism was euploid, < 20% mosaicism, low level mosaic, 20–40% mosaicism, high level mosaic (41–80% mosaicism), and aneuploid (> 80% mosaicism). For the control group, only patients with embryos graded 2BB or higher were chosen for matching to the PGT-A group.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were computed and reported. Mean and standard deviation were calculated for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. T-test was used for continuous variables and chi-square analysis was used for categorical variables. Power calculations were performed post hoc indicating adequate sample size at alpha of 0.05 and power of 0.80 to demonstrate the significant difference in cumulative live birth per retrieval noted between the PGT-A and control groups.

Results

A total of 191 PGT-A cycles where 3 of fewer blastocysts were biopsied were identified during the study period. 34 cases were excluded since they carried a diagnosis of endometriosis or 2 or more miscarriages. A further, 27 cycles were excluded since the PGT-A results included a mosaic embryo. The resulting 130 PGT-A cycles where 3 or fewer blastocysts were obtained were included and matched to 130 control cycles. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in age, BMI, oocyte number, MII oocytes, normally fertilized oocytes or blastocysts (Table 1). Further, the total number of embryos in each group was identical. Of note, each patient was represented in only one included IVF cycle.

Table 1.

Population demographics

| PGT (130 cycles) | No PGT (130 cycles) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.0 ± 5.1 | 36.4 ± 3.5 | 0.24 |

| BMI | 23.8 ± 4.1 | 24.9 ± 5.0 | 0.063 |

| Oocytes | 10.1 ± 5.5 | 8.9 ± 4.5 | 0.058 |

| 2PN | 5.3 ± 3.2 | 4.8 ± 2.6 | 0.36 |

| MII | 7.7 ± 4.6 | 6.8 ± 3.3 | 0.50 |

| Blasts | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 0.99 |

| Total embryos | 263 | 263 | |

| Total euploid embryos | 90 (34% of total) | n/a |

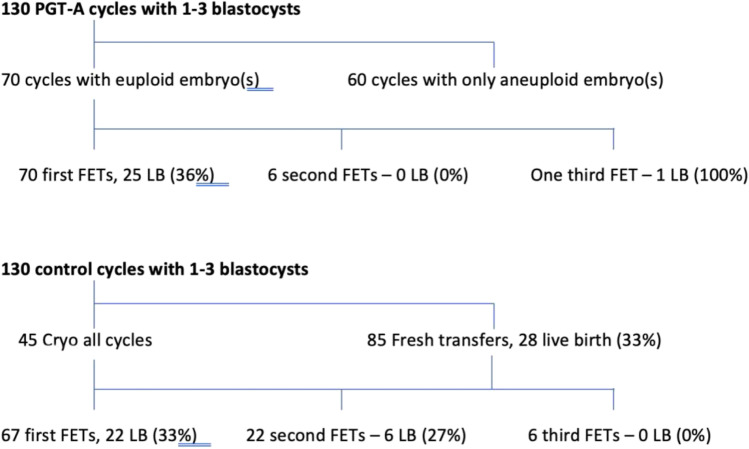

Figure 1 shows the treatment pathways for each group. In the PGT-A group, 60 of the 130 cycles (46%) yielded no euploid embryos available for transfer. In the remaining 70 cycles, 90 embryos were euploid and available for transfer. Since no PGT-A testing was done in the control group, there were many more embryos available for transfer. At the time of the data analysis, 180 embryo transfers were performed in the control group (68% of total embryos) vs 77 in the PGT-A group (29% of total embryos).

Fig. 1.

The treatment pathways including live birth outcome for the 130 cycles yielding 1 to 3 blastocysts where PGT-A was performed (top) and the 130 matched control cycles that did not undergo PGT-A (bottom)

Table 2 shows the pregnancy outcomes by cycle. The clinical pregnancy rate and live birth rate per embryo transfer were no different in the PGT-A and control groups. The miscarriage rate at 23% was the same in both groups. However, with many more transfers in the control group, including 85 fresh transfers, significantly higher cumulative live birth rates per oocyte retrieval were seen in the control group (0.43 vs 0.20). Cumulative live birth was calculated by adding together all live births obtained after all embryo transfers during the study period, and then reporting a per oocyte retrieval pregnancy rate.

Table 2.

Pregnancy outcomes by cycle

| PGT (130 cycles) | No PGT (130 cycles) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total embryo transfers | 77 | 180 | |

| Fresh transfers | 0 | 85 (CPR 0.41, LBR 0.32) | |

| Number of blastocysts per ET | 1.0 ± 0 | 1.05 ± 0.04 | 0.90 |

| Clinical pregnancy rate per ET | 0.45 (35/77) | 0.41 (74/180) | 0.51 |

| SAB rate | 0.23 (8/35) | 0.23 (17/74) | 0.99 |

| Biochemical pregnancy rate | 0.04 (3/77) | 0.04 (7/180) | 0.99 |

| Live birth rate per ET | 0.34 (26/77) | 0.31 (56/180) | 0.68 |

| Live birth rate per oocyte retrieval | 0.20 (26/130) | 0.43 (56/130) | 0.0037 |

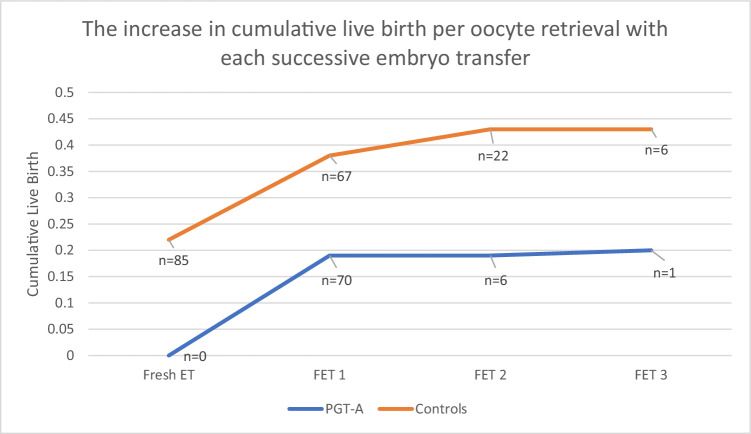

Figure 2 shows the increase in cumulative live birth with each subsequent embryo transfer. Cumulative live birth was recalculated here after each FET by adding to the numerator live births that arose from each subsequent embryo transfer, while the denominator (the oocyte retrievals that preceded these transfers) was a constant. The figure shows that a live birth benefit was seen in the control group after the first FET. Further, because of the possibility of fresh transfer when PGT-A is not performed, pregnancies that would result in live birth had already been achieved in the control group before embryo transfers were possible in the PGT-A group.

Fig. 2.

The increase in cumulative birth per oocyte retrieval with each successive embryo transfer in the PGT-A group vs the control group

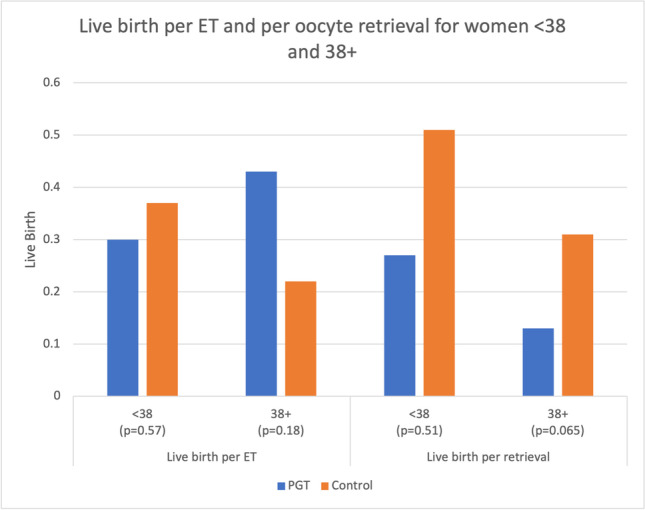

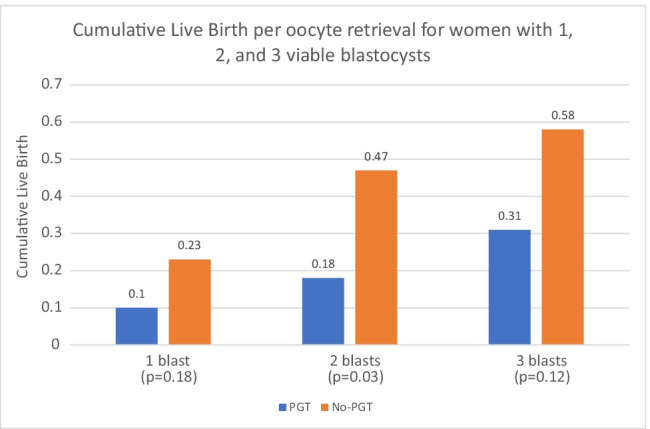

We performed a subgroup analysis by age (Table 3 and Fig. 3). For women aged < 38 years, there were 63 PGT-A cycles and 78 non-PGT control cycles. Of the 63 PGT-A cycle, 14 cycles were associated with no euploid embryos. The live birth rate per embryo transfer was 30% in the PGT-A group and 37% (NS) in the control group. However, the cumulative live birth rate per oocyte retrieval was 27% in the PGT-A group and 51% in the control group (P = 0.054). For women ≥ 38 years, there were 67 PGT-A cycles and 52 control cycles. Of the 67 PGT-A cycles, 46 cycles had no euploid embryos after testing. The live birth rate per embryo transfer was 43% in the PGT-A group and 22% in the control group (P = 0.18). However, the cumulative live birth rate per oocyte retrieval was lower (P = 0.065) in the PGT-A group of women ≥ 38 (13%) compared to the control group (31%). Altogether, out of 130 IVF cycles in the PGT-A group there were 26 babies born compared to the control group in which there were 56 babies born from 130 IVF cycles. In addition, there are another 83 embryos remaining in the control group and 13 embryos remaining in the PGT-A group which could potentially increase the cumulative pregnancy rate further in both groups (Table 4 and Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis analyzing outcomes for women 38 years and older and women under 38

| Women under 38 (141 cycles) | p-value | Women 38 and older (119 cycles) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGT (63 cycles) | Control (78 cycles) | PGT (67 cycles) | Control (52 cycles) | |||

| Total embryo transfers | 56 | 109 | 21 | 71 | ||

| Total number of embryos | 137 | 159 | 126 | 104 | ||

| Cycles with no euploid embryos | 14 | n/a | 46 | n/a | ||

| Total number of euploid embryos | 67 | n/a | 23 | n/a | ||

| Number of blastocysts per ET | 1.0 ± 0 | 1.0 ± 0 | n/a | 1.0 ± 0 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.13 |

| Clinical pregnancy rate per ET | 0.41 (23/56) | 0.47 (51/109) | 0.66 | 0.57 (12/21) | 0.32 (23/71) | 0.19 |

| SAB rate | 0.23 (5/23) | 0.24 (10/51) | 0.86 | 0.25 (3/12) | 0.30 (7/23) | 0.80 |

| Biochemical pregnancy rate | 3 | 6 | 0.99 | 0 | 1 | 0.99 |

| Live birth rate per ET | 0.30 (17/56) | 0.37 (40/109) | 0.57 | 0.43 (9/21) | 0.22 (16/71) | 0.18 |

| Live birth rate per oocyte retrieval | 0.27 (17/63) | 0.51 (40/78) | 0.054 | 0.13 (9/67) | 0.31 (16/52) | 0.065 |

Fig. 3.

Live birth per embryo transfer and per oocyte retrieval for women < 38 and women 38 + in the PGT-A group vs the control group

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis analyzing outcomes by number of blastocysts obtained

| 1 blast | 2 blast | 3 blast | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGT (n = 40) | No PGT (n = 39) | p-value | PGT (n = 49) | No PGT (n = 47) | p-value | PGT (n = 42) | No PGT (n = 43) | p-value | |

| Total embryo transfers | 14 | 40 | 28 | 68 | 37 | 79 | |||

| Number of blastocysts per ET | 1.0 ± 0 | 1.0 ± 0 | n/a | 1.0 ± 0 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.082 | 1.0 ± 0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 |

| Clinical pregnancy rate per ET | 0.29 (4/14) | 0.38 (15/40) | 0.67 | 0.39 (11/28) | 0.40 (27/68) | 0.98 | 0.54 (20/37) | 0.41 (32/79) | 0.41 |

| SAB rate | 0 | 0.33 (5/15) | n/a | 0.18 (2/11) | 0.18 (5/27) | 0.98 | 0.30 (6/20) | 0.22 (7/32) | 0.61 |

| Biochemical pregnancy rate | 0 | 4/40 | n/a | 2/28 | 1/28 | 0.57 | 2/37 | 1/79 | 0.21 |

| Live birth rate per ET | 0.29 (4/14) | 0.23 (9/40) | 0.72 | 0.32 (9/28) | 0.32 (22/68) | 0.99 | 0.35 (13/37) | 0.32 (25/79) | 0.79 |

| Live birth rate per oocyte retrieval | 0.10 (4/40) | 0.23 (9/39) | 0.18 | 0.18 (9/49) | 0.47 (22/47) | 0.03 | 0.31 (13/42) | 0.58 (25/43) | 0.12 |

Fig. 4.

Cumulative live birth per oocyte retrieval for women with 1, 2, and 3 blastocysts in the PGT-A group vs the control groups

Discussion

In our study of patients with 3 or fewer embryos, PGT-A offered no significant improvement in live birth per embryo transfer but yielded a significantly lower cumulative live birth rate per oocyte retrieval compared with matched controls (20% vs 43%, p = 0.0037).

A subgroup analysis by age revealed that live birth per embryo transfer did trend toward a benefit in the PGT-A group for women > 38 years of age but not for younger women, as consistent with the literature [6]. However, the cumulative live birth rate per oocyte retrieval was higher in the control group for both younger and older women, reflecting the benefit of more embryos for transfer in the control group. For example, in older women during the study period, 21 of 23 possible euploid transfers had occurred in the PGT-A group, whereas only 71 of 104 (68%) possible transfers had occurred in the control group, offering the opportunity for many more pregnancies (Table 3).

The large difference in cumulative birth rate is related to the number of oocyte retrievals in the PGT-A group that resulted in no embryo transfers due to no euploid embryos. Almost half of the cycles in the PGT-A group (46%) resulted in no euploid embryos available for transfer, and of the total 263 embryos in the PGT-A group only about a third (34%) were euploid and available for transfer. This effect was more pronounced in women > 38 years of age where 69% of cycles (46 of 67) yielded no euploid embryos for transfer, and only 18% (23 of 126) of embryos were euploid.

We also observed that the spontaneous abortion rate was not lower in the PGT-A group compared to the control group. This finding has been reported in prior studies, suggesting that the chromosomal status of the embryo is not the primary cause of miscarriage or alternatively, that the PGT-A process may be incomplete in its detection of aneuploidy (false negative) [6, 12, 13].

Our study differs from most previous studies of PGT-A since we evaluated a low prognosis group of patients with few embryos (3 or fewer) obtained after IVF stimulation. With a lower number of embryos for transfer, a screening test that has the risk of false positives will inordinately impact the live birth rate negatively. Moreover, our analysis included per oocyte retrieval pregnancy outcomes, as opposed to only per embryo transfer. This distinction is important since any potential value of PGT-A will only be realized if it maximizes the number of babies born while reducing the risk of miscarriage. Our results show that neither of these goals of PGT-A was achieved in women with a low number of embryos. Cycles yielding no embryos for transfer were disproportionately frequent in these women (46% of PGT-A cycles overall had no euploid embryos and 68% of cycles with no euploid embryos in women > 38 years old).

Franasiak et al. showed that in good prognosis patients with many embryos, the no euploid embryo rate was lowest in women aged 26 to 37 (2 to 6%) but increased significantly at ages 38 and above [14]. In the present study, limited to women with 3 or fewer embryos, we found the no euploid rate to approach 25% in women under 38, and 46% with no euploid embryos to transfer overall. This finding suggests a potential harm of PGT-A in women with few embryos.

In the case of older women, the argument has been made that the higher pregnancy rate per embryo transfer with PGT-A results in potentially reduced stress of fewer transfer failures leading to fewer patients discontinuing treatment [15]. However, with the results of the present study, this argument is specious if more than half of the cycles tested do not result in an embryo transfer because of all embryos testing aneuploid with PGT-A and especially with the results of the control group suggesting that many normal embryos are being discarded.

Even in the case of younger women where no difference in per transfer pregnancy outcome was seen, PGT-A may cause harm by reducing the proportion of cycles where an embryo transfer was possible. In our dataset of younger women with few embryos, up to 25% of PGT-A cycles had no transfer. This could lead to additional oocyte retrieval cycles which carry higher personal and financial costs than embryo transfer cycles.

A meta-analysis demonstrated an improved live birth per embryo transfer with the transfer of a PGT-A embryo as compared with an untested embryo [16]. But several studies have not shown PGT-A to improve outcomes, particularly in intention to treat analysis rather than per embryo transfer analysis [5, 7, 17, 18]. Of note, the large STAR trial found no significant pregnancy outcome difference per embryo transfer in PGT-A vs controls overall and only a small improvement in women age > 38. However, if results of the STAR trial were corrected for cycles with no embryo transfer because of all aneuploid embryos, the pregnancy rate per cycle was also not different in the women over age 38 compared to those with no PGT-A.

Although the cumulative pregnancy rate per oocyte retrieval was higher in the control group, a reasonable question is whether this may be overshadowed by the potential advantage of PGT-A to speed up the time to pregnancy, especially in older, poor prognosis patients where time consumed by failed transfers is both psychologically and biologically critical. In our study, the control group had a shorter time to pregnancy because of the ability to benefit from fresh embryo transfer, a path not possible in the PGT-A group. In fact, in our study of women with three or fewer embryos, almost half of the PGT-A group had no euploid embryos for transfer and the time to pregnancy was in fact prolonged in that group due to the need for additional retrievals.

Our study had limitations. Although we ensured that our PGT-A and control groups were well matched by the criteria we used, and we excluded certain diagnoses that were known to heavily influence IVF outcomes, we did not match for different diagnoses in our group. Further, this study was retrospective with all the bias inherent with that design. In addition, although the grades of the transferred embryos varied, we did standardize the control cycles to ensure that any embryos below the grade required for PGT-A biopsy (2BB) were not included. Mosaic cycles were excluded since our goal was to understand pregnancy outcomes in embryo transfers with normal PGT-tested embryos compared with matched controls. The exclusion of mosaic embryos due to the small number of cycles in this group and our desire to focus our question is a limitation of the study. Moreover, since the decision to undergo PGT-A was made between patient and physician, the precise reasons the patient choose PGT-A were also unknown.

The greatest strength of our study was the novel perspective of analyzing women with three or fewer embryos who underwent PGT-A and matching to others who also had only a few embryos for transfer without PGT-A.

Conclusion

Our study explored PGT-A results for the subgroup of patients who obtained 3 or fewer embryos in an IVF cycle. Our data suggest that PGT-A is not beneficial in this group. In younger women, pregnancy outcomes per embryo transfer were comparable in PGT-A vs controls but 25% of PGT-A cycles had no euploid embryos and did not proceed to embryo transfer. In older women (38 +), the PGT-A group trended to a higher per embryo transfer live birth rate for the few transfers that occurred, but a lower cumulative live birth rate per oocyte retrieval. In these older women, the impact of the large number of cycles with no embryos for transfer (69%) has a disproportionate adverse effect. Finally, our data showed that one of the largest contributions to cumulative live birth rate came from fresh embryo transfers which are not possible in the PGT-A group. The time to pregnancy, rather than being prolonged, may actually be shortened in the control group due to the potential for fresh transfer, and the lack of cancelled cycles due to no euploid embryos. Our data suggests PGT-A has limited utility in the subpopulation of women with few embryos and may cause harm.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: In Fig. 3 of this article the bars were incorrect. The figure should have appeared as shown below.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

10/3/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s10815-022-02631-9

References

- 1.Gleicher N, Orvieto R. "Is the hypothesis of preimplantation genetic screening (PGS) still supportable? A review," (in eng) J Ovarian Res. 2017;10(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13048-017-0318-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gleicher N, Patrizio P, Orvieto R. "How not to introduce laboratory tests to clinical practice: preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy," (in eng) Clin Chem. 2022;68(4):501–503. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvac001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang M, et al. "Author Correction: Depletion of aneuploid cells in human embryos and gastruloids," (in eng) Nat Cell Biol. 2021;23(11):1212. doi: 10.1038/s41556-021-00775-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolton H, et al. "Mouse model of chromosome mosaicism reveals lineage-specific depletion of aneuploid cells and normal developmental potential," (in eng) Nat Commun. 2016;7:11165. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang HJ, Melnick AP, Stewart JD, Xu K, Rosenwaks Z. "Preimplantation genetic screening: who benefits?," (in eng) Fertil Steril. 2016;106(3):597–602. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munné S, et al. "Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy versus morphology as selection criteria for single frozen-thawed embryo transfer in good-prognosis patients: a multicenter randomized clinical trial," (in eng) Fertil Steril. 2019;112(6):1071–1079.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.07.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubio C, et al. "In vitro fertilization with preimplantation genetic diagnosis for aneuploidies in advanced maternal age: a randomized, controlled study," (in eng) Fertil Steril. 2017;107(5):1122–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan J, et al. "Live Birth with or without preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy," (in eng) N Engl J Med. 2021;385(22):2047–2058. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meriano JS, Alexis J, Visram-Zaver S, Cruz M, Casper RF. "Tracking of oocyte dysmorphisms for ICSI patients may prove relevant to the outcome in subsequent patient cycles," (in eng) Hum Reprod. 2001;16(10):2118–2123. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.10.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rama Raju GA, Prakash GJ, Krishna KM, Madan K. "Meiotic spindle and zona pellucida characteristics as predictors of embryonic development: a preliminary study using PolScope imaging," (in eng) Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14(2):166–74. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner DK, Lane M. "Culture and selection of viable blastocysts: a feasible proposition for human IVF?," (in eng) Hum Reprod Update. 1997;3(4):367–82. doi: 10.1093/humupd/3.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno I, et al. "Evidence that the endometrial microbiota has an effect on implantation success or failure," (in eng) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(6):684–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franasiak JM, Scott RT. "Contribution of immunology to implantation failure of euploid embryos," (in eng) Fertil Steril. 2017;107(6):1279–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franasiak JM, et al. "The nature of aneuploidy with increasing age of the female partner: a review of 15,169 consecutive trophectoderm biopsies evaluated with comprehensive chromosomal screening," (in eng) Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):656–663.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Domar AD, Smith K, Conboy L, Iannone M, Alper M. "A prospective investigation into the reasons why insured United States patients drop out of in vitro fertilization treatment," (in eng) Fertil Steril. 2010;94(4):1457–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen M, Wei S, Hu J, Quan S. "Can comprehensive chromosome screening technology improve IVF/ICSI outcomes? A Meta-Analysis," (in eng) PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maxwell SM, McCulloh DH, Lee H, Berkeley AS, Grifo J. Preimplantation genetic screening (PGS) with next generation sequencing (NGS) achieves ongoing pregnancy with fewer transfers and total miscarriages compared to non-PGS cycles. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(3):e20. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy LA, et al. To test or not to test? A framework for counselling patients on preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) Hum Reprod. 2018;34(2):268–275. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]