Abstract

A positive selection method for mutations affecting bioconversion of aromatic compounds was applied to a mutant strain of Agrobacterium tumefaciens A348. The nucleotide sequence of the A348 pcaHGB genes, which encode protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase (PcaHG) and β-carboxy-cis,cis-muconate cycloisomerase (PcaB) for the first two steps in catabolism of the diphenolic protocatechuate, was determined. An omega element was introduced into the pcaB gene of A348, creating strain ADO2077. In the presence of phenolic compounds that can serve as carbon sources, growth of ADO2077 is inhibited due to accumulation of the tricarboxylate intermediate. The toxic effect, previously described for Acinetobacter sp., affords a powerful selection for suppressor mutations in genes required for upstream catabolic steps. By monitoring loss of the marker in pcaB, it was possible to determine that the formation of deletions was minimal compared to results obtained with Acinetobacter sp. Thus, the tricarboxylic acid trick in and of itself does not appear to select for large deletion mutations. The power of the selection was demonstrated by targeting the pcaHG genes of A. tumefaciens for spontaneous mutation. Sixteen strains carrying putative second-site mutations in pcaH or -G were subjected to sequence analysis. All single-site events, their mutations revealed no particular bias toward multibase deletions or unusual patterns: five (−1) frameshifts, one (+1) frameshift, one tandem duplication of 88 bp, one deletion of 92 bp, one nonsense mutation, and seven missense mutations. PcaHG is considered to be the prototypical ferric intradiol dioxygenase. The missense mutations served to corroborate the significance of active site amino acid residues deduced from crystal structures of PcaHG from Pseudomonas putida and Acinetobacter sp. as well as of residues in other parts of the enzyme.

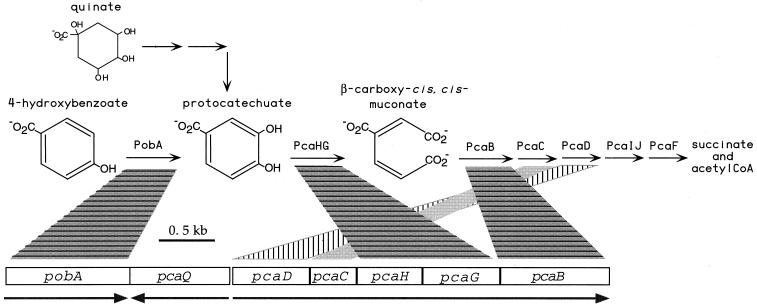

The β-ketoadipate pathway consists of two convergent branches that convert aromatic compounds into tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates. The protocatechuate (3,4-dihydroxybenzoate) branch of the pathway, widespread among soil bacteria, serves as a common catabolic destination for quinate, shikimate, and numerous aromatic substrates, including its diphenolic namesake (Fig. 1). Because of its ubiquity in soil microbes, biochemical characterization, and role as a common track in the biotransformation of diverse aromatic compounds, the β-ketoadipate pathway has been a fruitful subject of investigation in several species of bacteria (18, 30).

FIG. 1.

Steps for the conversion of 4-hydroxybenzoate, quinate, and protocatechuate to intermediates of the TCA cycle, shown above the organization of A. tumefaciens A348 genes required for initial steps in the catabolic pathway. Spotlights link enzymes with their encoding genes; pcaQ encodes an activator of pcaDCHGB expression. Arrows denote units and directions of transcription. Enzymes: PobA, 4-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase; PcaHG, protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase; PcaB, β-carboxy-cis,cis-muconate cycloisomerase; PcaC, γ-carboxymuconolactone decarboxylase; PcaD, β-ketoadipate enol-lactone hydrolase; PcaIJ, β-ketoadipate succinyl coenzyme A (CoA) transferase; PcaF, β-ketoadipyl-CoA thiolase.

A positive selection method has been described for a derivative of Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 that contains the pcaBDK1 deletion (16, 17). Lacking two enzymes required for growth at the expense of protocatechuate, the strain cannot grow at the expense of the compound or of substrates that feed into it. Buildup of inhibitory levels of the intermediate β-carboxy-cis,cis-muconate was deduced to lead to the additional failure of the strain to grow on nonselective media in the presence of added aromatic substrates. The ability to screen for secondary mutant strains that can reduce toxic levels of the tricarboxylic acid has proved to be a powerful experimental tool (7, 12). Genetic analysis of secondary mutant strains derived from the ΔpcaBDK1 strain, ADP500, revealed that many of them contained large deletions in the pca region of the chromosome (12).

Characterization of the pca genetic region of the tumorigenic plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens A348 (30) has provided an opportunity to investigate the role of aromatic compound degradation in the process of wound colonization. Plant wound sites are likely to be particularly rich in aromatic compounds, which can be toxic. It is not known whether the ability to degrade particular aromatic compounds contributes to successful colonization of the plant wound by A. tumefaciens nor to what extent the aromatic constituents of the wound environment exert a toxic effect. Obtaining a mutant that is particularly sensitive to the presence of aromatic growth substrates would facilitate efforts to understand this aspect of colonization and could be used to generate second-site mutants that would complement such a study. Therefore, this investigation was undertaken to determine whether the positive selection method used with Acinetobacter could be applied successfully to A. tumefaciens.

The outcome of the pcaB-tricarboxylic acid positive selection method is likely to depend on a number of variables which include gene organization and regulation. In Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1, the enzyme that produces the potentially toxic tricarboxylic acid is encoded by the last two genes of the pcaIJFBDKCHG transcript (8); its substrate, protocatechuate, is a coinducer of the transcript. In A. tumefaciens A348, the product of this enzymatic reaction, carboxymuconate, is the coinducer of the pcaDCHGB transcript (Fig. 1B) (30). Because pcaB lies downstream of pcaHG, a selectable element could be inserted into it without terminating transcription of pcaHG.

The initial target of spontaneous mutation in A. tumefaciens was protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase (PcaHG). This enzyme catalyzes an intradiol cleavage of the aromatic ring by oxygen. High-resolution crystal structures of the dioxygenases from Pseudomonas putida (27) and Acinetobacter sp. (45) have been determined. Although PcaHG quarternary structures from diverse microbes vary, the unit promoters have been found to be the same: a heterodimer comprised of an α and a β chain, encoded by pcaG and pcaH, respectively, and a nonheme ferric ion. With the active site located at the α/β interface, critical active site residues are contributed by both subunits, but only the β subunit contains iron ligands (26).

The ability of an Agrobacterium radiobacter strain to oxidize 4-sulfocatechol was shown to be mediated by a novel PcaHG (14). The holoenzyme complex of the sulfocatechol dioxygenase was much smaller than that of most characterized PcaHGs (23). Information gleaned from the sequence and mutational analysis of the A. tumefaciens A348 protein should be relevant to the ongoing study of the related dioxygenases of A. radiobacter.

The primary goal of this investigation was to discover whether the pcaB mutant trick which works so well in Acinetobacter would be effective in a different genetic background. An additional goal was to assess the types of spontaneous mutations generated by exposure to toxic levels of carboxymuconate. To this end, the spontaneous pcaH or pcaG mutations generated under the toxic selection conditions were catalogued without bias with respect to particularly desirable types, such as missense mutations. As an outcome of the work, a number of novel PcaHG mutants were isolated. Although previous work established the order pcaH-pcaG-pcaB in A. tumefaciens A348, only a small segment of the former two genes was sequenced (34). This communication presents a sequence analysis of the three genes in their entirety.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular techniques and growth media.

Standard methods of molecular biology were used (3, 41). Conjugations were carried out as previously described (32). A. tumefaciens cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (43) or minimal medium (35) at 30°C. Minimal medium was supplemented with carbon source(s) at the following concentrations: succinate or arabinose at 10 mM, quinate at 5 mM, or 4-hydroxybenzoate at 1.5 mM. Luria-Bertani medium, used for growth of Escherichia coli at 37°C, was supplemented with one or more of the antibiotics ampicillin, spectinomycin, streptomycin, and tetracycline at concentrations of 80, 40, 20, and 12.5 μg ml−1, respectively. Minimal medium prepared for A. tumefaciens included ampicillin, spectinomycin, and tetracycline at concentrations of 100, 125, and 1.25 μg ml−1, respectively, as necessary.

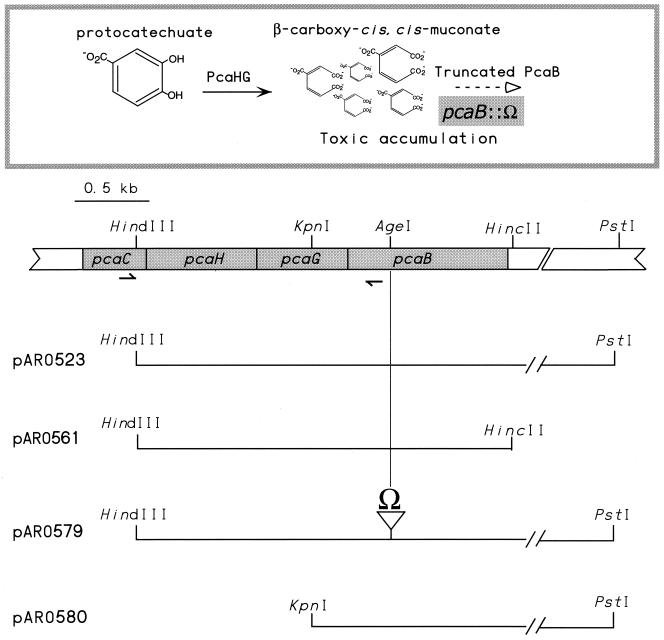

Construction and characterization of a pcaB mutant strain.

Table 1 lists strains and plasmids integral to the project. Sequence analysis identified a unique AgeI site 0.43 kb from the 5′ end of the pcaB gene in pARO523 (Fig. 2). An Ω transcription termination element with compatible ends was ligated into the site, forming pARO579 (Fig. 2). The pcaB::Ω mutation was introduced into A. tumefaciens A348 through conjugation with E. coli S17-1(pARO579). The mating mix was plated onto agar-solidified minimal medium containing succinate plus spectinomycin. Spcr colonies were screened for absence of the vector Apr marker, and a pcaB::Ω candidate was purified. The pcaB::Ω isolate, strain ADO2077, failed to grow at the expense of aromatic compounds, and it was maintained on medium free of aromatic or hydroaromatic compounds. Location of the Ω element was verified by PCR using primers flanking the site of insertion, described below, followed by gel electrophoresis. As expected, introduction of plasmid pARO4 carrying a heterologous pcaB restored the ability of ADO2077 to grow at the expense of quinate. Furthermore, introduction of either pARO561 or pARO580 (Fig. 2) restored ADO2077 to a quinate+ phenotype.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) supE44λ− thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Gibco-BRL |

| S17-1 | recA pro hsdR; RP4-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 integrated into the chromosome | 44 |

| Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP853 | pcaB frameshift mutation created by filling in the ends of an NcoI site | W. M. Coco |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains | ||

| A348 | Chlr Nalr Rifr Smr; derived from C58, containing the cryptic plasmid pAtC58 and the octopine Ti plasmid pTiA6 | 20 |

| ADO2077 | Spcr SmrΩ element of pHP45Ω in AgeI site of pcaB; pcaB1 | This study |

| ADO2085 to ADO2100 | pcaH or pcaG mutation in ADO2077 genetic background (Table 2) | This study |

| UIA5 | Rifr Smr Spcr; derived from C58, cured of pTiC58 and the cryptic plasmid pAtC58 | S. K. Farrand |

| Plasmids | ||

| pARO2 | Tcr; HindIII insertion of Acinetobacter pcaCHG genes in pRK415 | 37 |

| pARO4 | Tcr; SalI insertion of Acinetobacter pcaFBDKC genes in pRK415 | 37 |

| pARO190 | Apr; mobilizable derivative of pUC19 | 33 |

| pARO523 | Apr; 4.65-kb HindIII-PstI fragment of A. tumefaciens A348 DNA carrying the 3′ end of pcaC plus pcaBHG in pARO190 | 34 |

| pARO561 | Apr; pARO523 with a 1.6-kb deletion from the HincII site 71 bp beyond the 3′ end of pcaB to the PstI site at the end of the insertion | This study |

| pARO566 | Apr; HindIII-PstI fragment of pARO523 ligated into the corresponding sites in pUC19 | This study |

| pARO567 | Apr; 3.0-kb KpnI-PstI fragment of pARO523 in pUC19. The lac promoter directs transcription off the noncoding strand of pcaB. | This study |

| pARO572 | Apr Spcr Smr; XmaI-digested Ω fragment of pHP45Ω in the AgeI site of pARO566, yielding pcaB::Ω | This study |

| pARO579 | Apr Spcr Smr; insertion of pARO572 in pARO190 | This study |

| pARO580 | Apr; KpnI-PstI insertion of pARO567 in pARO190 | This study |

| pHP45Ω | Apr Spcr Smr; source of 2.0-kb Ω element | 38 |

| pRK415 | Tcr; broad-host-range, mobilizable vector | 19 |

| pUC19 | Apr; cloning vector | 47 |

FIG. 2.

Subclones used in construction of A. tumefaciens strain ADO2077 and analysis of mutant strains. ADO2077 accumulates carboxymuconate in the presence of protocatechuate or certain of its metabolic precursors. Beneath a map of chromosomal pca genes are subclones used to sequence, to create the pcaB::Ω mutation, and to analyze ADO2077 as well as secondary mutant strains derived from it. The small arrows, not drawn to scale, shown under pcaC and pcaB represent the locations of primers ATPCAH2 (on the left) and DP523HF2 (on the right) used in PCR amplification of mutant pcaHG sequences. The distance from the 3′ end of pcaB to the PstI site is 1.7 kb, and this DNA encodes a set of genes with homology to ABC-type transporter genes (Parke, unpublished).

Growth tests with ADO2077 and A348 were conducted in liquid minimal medium containing succinate to determine the sensitivity of ADO2077 to 4-hydroxybenzoate. Each replicate set of experiments originated from a single colony inoculated into liquid minimal medium containing succinate. A diluted, overnight culture of those cells was used as a source of approximately 104 cells, which were inoculated into 5 ml of liquid minimal medium containing succinate alone or succinate plus different concentrations of 4-hydroxybenzoate. The low inoculum was used to minimize the contribution of suppressor mutants to the population of ADO2077 cells. Growth of cultures exposed to succinate alone was closely monitored. When those cells reached stationary phase, which took the same length of time for A348 and ADO2077 cells, growth yields were determined for all conditions in each replicate set of tubes. Due to low growth yields under some conditions and the presence of a compound(s) that absorbed at 600 nm, it was necessary to obtain viable counts for the ADO2077 cells. Viable counts were also made for one replicate of the wild-type cells, but since the correlation between optical density at 600 nm and viable count was consistent for them, growth yields could be determined by optical density and converted into viable counts for other replicates of these cells.

Second-site suppressor mutation frequency was measured by spreading an overnight culture grown at the expense of succinate onto selective medium. The same cells were diluted, and their viable count was determined on a nonselective medium. Suppressor mutation frequency was the fraction of the total viable count that appeared as CFU on the selective medium at 30°C. Colonies were counted after 5 days on succinate plus 1.5 mM 4-hydroxybenzoate and after 3 days on arabinose plus the aromatic compound.

Isolation of pcaH or pcaG secondary mutant strains.

ADO2077 was plated onto minimal medium containing succinate plus 1.5 mM 4-hydroxybenzoate. Protocatechuate itself was not used in the initial selection because of its instability (7). Colonies that appeared to be resistant to 4-hydroxybenzoate were purified. Further screening for pcaH or -G mutants involved testing each isolate for accumulation of protocatechuate upon exposure to 4-hydroxybenzoate. For this test, minimal medium containing 4-hydroxybenzoate and succinate was supplemented with p-toluidine, a chromophore specific for diphenolics (31). In addition, isolates were rechecked on the medium used for the initial selection as well as screened on medium supplemented with protocatechuate rather than 4-hydroxybenzoate. Presumptive pcaH or -G secondary mutant strains, isolated at 30°C, were assessed for heat sensitivity by screening at 21°C. Strains that had preserved the Spcr Ω marker and had accumulated protocatechuate were mated with E. coli S17-1(pARO523) and plated onto selective medium with quinate as the sole carbon source. An independent analysis was carried out by introducing pARO561. Strains for which pARO523 and pARO561 (Fig. 2) restored the ability to grow at the expense of quinate and 4-hydroxybenzoate were presumed to be pcaH or -G mutants. The pcaHG region in each mutant was recovered from the chromosome by PCR amplification as described below, and both genes were sequenced.

Correction of the pcaB::Ω mutation in strains carrying secondary mutations in pcaH or -G.

To discern the effect of a pcaH or -G mutation on the phenotype of Agrobacterium in the absence of the pcaB mutation, it was desirable to correct the latter mutation. In Acinetobacter strain ADP500, it is possible to select for replacement of ΔpcaBDK1 with wild-type genes because the strain also contains a mutation in catD. The latter gene encodes an enzyme that is isofunctional with PcaD and that catalyzes a reaction in the dissimilation of benzoate; expression of pcaD is sufficient to allow catD mutant cells to grow at the expense of benzoate (12, 21). Given that A. tumefaciens has a different gene organization, correction of the pcaB mutation required a different approach.

Replacement of pcaB::Ω with the wild-type gene was carried out on eight strains with missense, deletion, or insertion mutations in pcaH or -G. Introduction of pARO2 provided a heterologous PcaHG to compensate for the PcaH or -G mutation. A. tumefaciens strains carrying pARO2 were mated with E. coli S17-1(pARO580). Agrobacterium cells that had acquired the pcaB marker of pARO580 (Fig. 2) and retained pARO2 were able to grow at the expense of quinate. Following colony purification on solidified minimal medium containing quinate plus tetracycline, colonies were screened for the absence of the pARO580 Apr marker and the pcaB Ω marker. Aps Spcs Tcr quinate+ colonies were cultured in nonselective liquid medium to cure them of pARO2. Following subculture, Tcs strains were presumed to retain the pcaH or -G mutation, with the wild-type pcaB restored. Strains carrying only the pcaH or -G mutation exhibited varying, reduced growth on quinate.

PCRs.

Template DNA was prepared according to directions supplied with InstaGene Matrix (Bio-Rad). PCR conditions for the primer pair ATPCAH2 and DP523HF2 were 97°C for 3 min, 30 cycles of denaturing at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 59°C for 30 s, and elongation at 72°C for 1 min. Conditions for the primer set ATPCAB and DP523HF1 were similar except for annealing at 65°C for 30 s and elongation at 72°C for 2 min 30 s. The Keck Biotechnology Resource Lab at Yale University synthesized PCR primers. Primers ATPCAH2 (5′-CCGCCAACCACGCTTTCAAG-3′), located near the 3′ end of pcaC, and DP523HF2 (5′-CGCATCTGCCGCACGAGTT-3′), located in pcaB, were used to amplify pcaH or-G mutant strains, and their locations are shown in Fig. 2. Primers ATPCAB (5′-C G C A G G C G C A G G T G G G A A C A G-3′) and DP523HF1 (5′-CGCGATATCCTGCCCGAACTT-3′) served to amplify the region encompassing the pcaB::Ω mutation. When generating template from a mutant strain for sequence analysis, usually several independent PCRs were performed, the reaction products were pooled, and a QIAquick PCR purification step (Qiagen Inc.) preceded DNA sequencing.

DNA sequencing.

Analysis of A. tumefaciens pcaB makes reference to sequence data for Sinorhizobium meliloti generated by S. R. Long and colleagues at the Department of Biological Sciences, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the Stanford DNA Sequencing and Technology Center (http://cmgm.stanford.edu/∼mbarnett/1xgenome.htm). ABI PRISM terminator cycle sequencing with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase, conducted at the Yale Keck Biotechnology Resource Lab, was employed to sequence both strands of the pcaHGB region by primer walking with pARO523 or pARO561 as a template.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence for the pcaQDCHGB genes from A. tumefaciens A348 has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. U32867.

RESULTS

Evidence that the pca gene cluster is chromosomal in A. tumefaciens A348.

Although it was previously established that the pca genetic region of A348 was not located on its Ti plasmid (36), it remained possible that a cryptic plasmid, pAtC58, carried these sequences. Strain UIA5, which has a C58 chromosomal background similar to that of A348 except for antibiotic resistance markers, is cured of pTi and pAtC58. However, it displayed the growth properties of A348 on minimal medium with quinate as the sole carbon source. Establishment of a chromosomal location of the pca genes in this strain is interesting in light of evidence that the genes for quinate and protocatechuate are located on the pSymb megaplasmid in the related bacterium S. meliloti (4). It remains to be determined whether the pca genetic region is on the circular or the linear chromosome of A348 (13).

Sensitivity of the pcaB::Ω strain ADO2077 to 4-hydroxybenzoate.

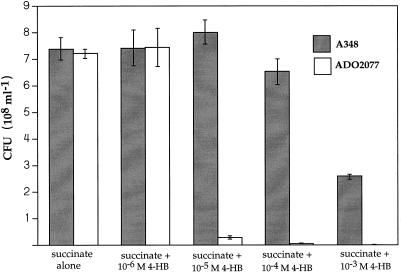

Figure 3 shows the growth yields of ADO2077 compared to its parental strain in the presence of increasing concentrations of 4-hydroxybenzoate. Growth inhibition by 4-hydroxybenzoate was imperceptible at 1 μM, was notable at 10 μM, and appeared to be complete at 1 mM. On minimal medium plates containing succinate, 4-hydroxybenozate caused total inhibition of cell growth at 1 mM as well, and this was the minimum concentration required to screen for suppressor mutants. Only extremely slow growth of single colonies was observed on solid media containing succinate plus 10−4 M aromatic compound. For comparison, the phenotype of Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP853 (W. M. Coco and L. N. Ornston, Abstr. 97th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. K-81, p. 355, 1997), a pcaB strain, was examined. This strain was used rather than ADP500 because its mutation is restricted to pcaB. A culture of ADP853 was streaked on the same succinate plates containing different concentrations of 4-hydroxybenzoate. Formation of single colonies of ADP853 was totally inhibited by 10 μM 4-hydroxybenzoate. It should be noted that cells recover from growth inhibition once the aromatic compound is removed. The viable cell concentration in cultures exposed to 1 mM 4-hydroxybenzoate for the duration of the experiments shown in Fig. 3 remained stable (Fig. 3); however, the mechanism of carboxymuconate inhibition remains unknown.

FIG. 3.

Growth yields of pcaB mutant strain ADO2077 in the presence of different concentrations of 4-hydroxybenzoate (4-HB) relative to those of the parental strain A348. As detailed in Materials and Methods, the growth yields for each replicate set of conditions were determined when the cells grown in the presence of succinate alone reached full growth yield, and this occurred at about the same time for both A348 and ADO2077. Values for ADO2077 exposed to 10−5, 10−4, and 10−3 M 4-hydroxybenzoate, difficult to gauge in the figure, are 2.4 × 107, 3.2 × 106, and 3.5 × 103 CFU ml−1, respectively. The data presented are the means from three independent growth tests. The error bars represent standard error of the mean for each set of conditions.

Curiously, supplementation of minimal medium containing succinate or arabinose with the precursor substrate quinate (Fig. 1) was not growth inhibitory to ADO2077. The rationale for this result may lie in feedback regulation of quinate dissimilation. The ADO2077 pcaB mutation was very stable: revertants did not arise out of a population of 3 × 1010 cells plated onto quinate.

Characterization of pcaB::Ω strains which are resistant to 4-hydroxybenzoate.

Resistant colonies appeared on plates of minimal medium containing succinate plus 1.5 mM 4-hydroxybenzoate at a frequency of 5 × 10−6 at 30°C. The colonies appeared significantly faster when arabinose was substituted for succinate, but ultimately the frequency was the same. A similar frequency of resistant colonies was noted for ADP853 on the same succinate plus 4-hydroxybenzoate medium, a reflection of the large number of potential targets for suppressor mutations. The number of genes or genetic regions that could be responsible for resistance to 4-hydroxybenzoate is limited, however (Fig. 1): the pob structural gene or its upstream regulatory gene, the pcaQ regulatory gene or the intergenic region upstream of it, or the pcaH or pcaG structural gene. Strains later shown to be pcaH or -G mutants excreted protocatechuate in the presence of precursor substrate, they generally grew slower on a medium containing 4-hydroxybenzoate than pob mutants, and they grew more rapidly than the latter strains on minimal medium supplemented with protocatechuate. Mutations in pcaQ or the region between pcaQ and pcaD would accumulate protocatechuate as well, but the following test distinguished pcaH or -G mutations from these. The final step was correction of the quinate− phenotype by pARO523 and pARO561 (Fig. 2). The plasmids should not restore the wild-type phenotype to a regulatory mutant. Use of pARO561 rules out the possibility that DNA beyond the HincII site contributed to the wild-type phenotype.

Strains resistant to 4-hydroxybenzoate were also screened for retention of the Ω element which lies 0.46 kb downstream of pcaG in ADO2077. Out of 120 purified isolates, only 2 had deletions that covered the region of the Spcr insertion. Furthermore, every presumptive pcaH or -G mutant for which PCR amplification was carried out possessed the primer sequences upstream and downstream of pcaHG (Fig. 2).

Sequence analysis of pcaB.

The ATG start codon of the A. tumefaciens A348 pcaB gene is located 12 bp downstream of pcaG and 7 bp downstream of a putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence. The gene is 1,062 bp long, with a G+C content of 63.6%. The HincII site shown in Fig. 2 is 73 bp beyond the 3′ end of pcaB. One half of an 8-bp stem palindrome precedes the HincII site by 5 bp. A set of genes with homology to ATP-binding cassette transporter genes lies downstream of pcaB; the first open reading frame of the set is 0.37 kb beyond the stop codon of pcaB (D. Parke, unpublished data).

The A348 PcaB sequence was subjected to BLAST analysis (2), and the top five scoring sequences were analyzed further by the Clustal alignment method. Of the five, the A348 PcaB most closely resembled a PcaB-like sequence from P. putida (GenBank accession no. 5091486) (39). Alignment by the Clustal method revealed 37% amino acid sequence identity of that strain against the A348 primary sequence. Since the functional enzymes from other species are distant from that of A348 as well, the enzyme clearly tolerates extensive divergence.

Homologs examined by the Clustal method included two P. putida strains (GenBank accession no. 2851427 and 5091486), Acinetobacter strain ADP1 (GenBank accession no. 6093650), Bradyrhizobium japonicum (GenBank accession no. 6093651), and Rhodococcus opacus (GenBank accession no. 2935026) (9, 21, 24, 46). Compared to the other five PcaBs, that of A348 is truncated at the C terminus. Relative to the Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 pcaB gene, it is truncated by 297 bp. One of the P. putida genes (GenBank accession no. 2851427) is also divergent at the 3′ end, being 135 bp shorter than that of ADP1. The C-terminal 150 amino acid sequence of a putative PcaB was deduced from the preliminary database on S. meliloti. Alignment of the available C-terminal half of this protein with that of A348 revealed a sequence identity of 65%. The S. meliloti open reading frame ends two amino acids short of the A. tumefaciens sequence. The S. meliloti pcaB homolog was located on an 881-bp contig, and the end of the gene was about 200 bp from the end of the fragment. It should be noted that the presumed 5′ end of the pcaB gene was found on another contig just downstream of pcaG in S. meliloti, as in A348.

Alignment of the additional C-terminal PcaB sequences of the other, divergent species reveals a number of conserved residues. Such conservation suggests that the C-terminal portion of those proteins is important and that compensatory mutations may have been required for functionality of the truncated A348 cycloisomerase.

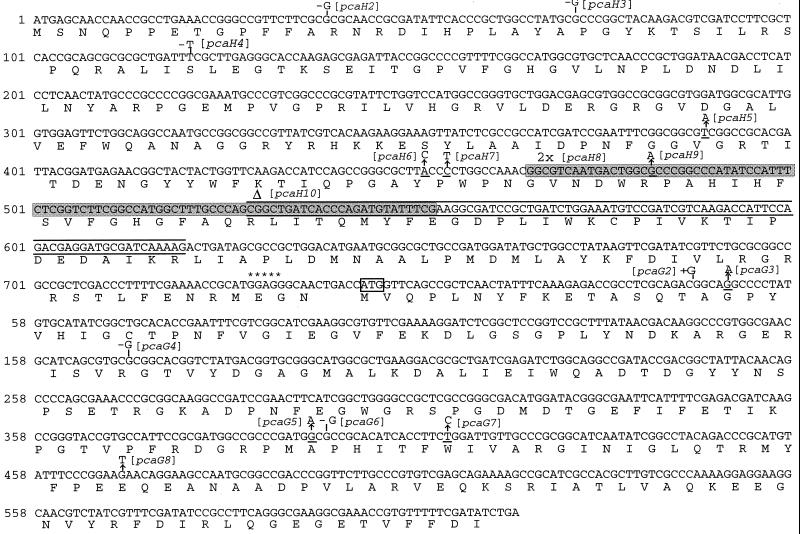

Sequence analysis of pcaHG.

The sequence of A348 pcaHG, with a G+C content of 60.1%, and its deduced amino acid sequence are presented in Fig. 4. The translational start of pcaH overlaps the last four bases of pcaC, and 5-bp upstream of it lies a putative Shine-Dalgarno motif in the sequence GGAGGAG. The subunits share a common evolutionary origin (15, 26): Clustal alignment of the A. tumefaciens PcaH and PcaG revealed that 32% of the aligned residues of the β subunit are identical to those of the α subunit.

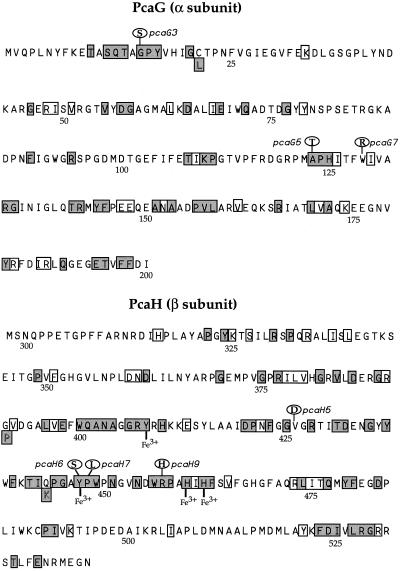

FIG. 4.

Nucleotide and translated amino acid sequences of pcaH and pcaG from A. tumefaciens A348. The initiation codon of pcaG is boxed for clarity. Locations of mutations are shown above the wild-type sequence. Mutations include a deletion of G (pcaH2, pcaH3, pcaG4, and pcaG6), insertion of G (pcaG2), deletion of T (pcaH4), and the G-to-T transversion of pcaG8. Locations of missense mutations (pcaH5, pcaH6, pcaH7, pcaH9, pcaG3, pcaG5, and pcaG7) are underlined; the new base is shown above an arrow. Additional mutations are the 88-bp tandem duplication (2x) pcaH8, shown as a highlighted sequence, and the 92-bp deletion of pcaH10, denoted by over- and underlining. Asterisks mark the putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence for pcaG translation.

Alignment of the A. tumefaciens α or β subunits with their respective homologs from seven other bacterial strains representing four genera was made using Clustal analysis; the seven strains are listed in the legend to Fig. 5. By this method, the A. tumefaciens β chain showed 59% identity with that of P. putida (GenBank accession no. 1172050) and 58% with that of Acinetobacter (GenBank accession no. 6174894). The α subunits (GenBank accession no. 1172049 and 6174893) were slightly more divergent, with values of 46 and 57.8%, respectively. By this measure, the A348 subunits resembled those of the other two species as much as or more than the latter two resembled each other.

FIG. 5.

Conserved residues of A. tumefaciens A348 PcaG and PcaH sequences and amino acid substitutions caused by missense mutations. Oval balloons above the PcaG and PcaH sequences contain residues substituted in the mutant strains, next to the gene designations underlying the changes. Table 2 and Fig. 4 provide additional information on each mutation. The Clustal method of sequence alignment was applied to PcaG and PcaH chains from strain A348 and the following species and strains (with GenBank accession numbers in parentheses): Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 (6174893 and 6174894), Burkholderia cepacia (129711 and 129714), Pseudomonas marginata (4096596 and 4096595), P. putida NCIMB 9869 (4808515 and 4808514), P. putida ATCC 23975 (1172049 and 1172050), Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 (4886556 and 4886555), and R. opacus (2935025 and 2935024) (6, 9, 7, 11, 15, 29, 48). Gaps introduced in the A348 PcaG sequence by Clustal alignments are not shown; however, none of the gaps are unique to A348. Shaded boxed residues are identical in all strains; unshaded boxed residues represent amino acids that are not necessarily identical in all strains but belong to the following related groups: residues with nitrogenous side chains (H, K, N, Q, R), acidic (D, E), small nonpolar (I, L, V), polar (S, T), or aromatic (F, W, Y). Amino acids boxed below the Agrobacterium sequences are identical in the aligned proteins of all other bacteria compared. Also shown below the A348 line are four residues implicated in binding Fe3+. To facilitate comparison with structurally characterized proteins, the numbering beneath the amino acid residues corresponds to published positions in P. putida and Acinetobacter sp. subunits (7, 27). Thus, the residues in PcaG are numbered −2 to 200 and those of PcaH are numbered 298 to 542, which necessarily differs from the numbering used in Fig. 4 and Table 2.

Spectrum of mutations in pcaH and pcaG.

Unique spontaneous mutations were distributed along the nucleotide sequence of pcaH and pcaG (Fig. 4; Table 2). Two mutations were exceptional, altering multiple base pairs: pcaH8, an 88-bp tandem duplication; and pcaH10, a 92-bp deletion. Both mutations resulted in frameshifts (Fig. 4; Table 2). Of the remaining 14 mutations, 6 caused frameshifts; 5 were 1-bp deletions, and 1 was a 1-bp duplication. The eight point mutations included one, pcaG8, that introduced a nonsense codon near the end of pcaG; the rest were missense mutations. In keeping with the relative numbers of transition and transversion mutations in other systems (42), there were five of the former and three of the latter.

TABLE 2.

Strains with sequenced spontaneous mutations in pcaH and -G

| Strain | Genotype | Mutation

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide(s)a | Amino acid(s)b | ||

| ADO2085 | pcaB1 pcaH2 | Δ(G39) | Frameshift |

| ADO2086 | pcaB1 pcaH3 | Δ(G72) | Frameshift |

| ADO2087 | pcaB1 pcaH4 | Δ (T121) | Frameshift |

| ADO2088 | pcaB1 pcaH8 | 2× (G466–G553) | 2× (G156-E185′); frameshift |

| ADO2089 | pcaB1 pcaH10 | Δ(C529–G620) | Δ(R177-R207′); frameshift |

| ADO2090 | pcaB1 pcaH5 | T389A | V130D |

| ADO2091 | pcaB1 pcaH6 | A452C | Y151S |

| ADO2092 | pcaB1 pcaH7 | C455T | P152L |

| ADO2093 | pcaB1 pcaH9 | G482A | R161H |

| ADO2094 | pcaB1 pcaG2 | +G (between C44 and G45) | Frameshift |

| ADO2095 | pcaB1 pcaG4 | Δ(G170) | Frameshift |

| ADO2096 | pcaB1 pcaG6 | Δ(G396) | Frameshift |

| ADO2097 | pcaB1 pcaG8 | G469T | Termination |

| ADO2098 | pcaB1 pcaG3 | G49A | G17S |

| ADO2099 | pcaB1 pcaG5 | G394A | A132T |

| ADO2100 | pcaB1 pcaG7 | T412C | W138R |

The first nucleotide in the numbering of each gene is the A residue in the ATG start codon.

Each subunit is numbered starting from its N-terminal amino acid as shown in Fig. 4. However, to simplify comparison to published data on PcaHG in P. putida (27) and Acinetobacter sp. (7, 45), the nomenclature is different in Fig. 5: amino acid residues in PcaG are numbered −2 to 200, and those of PcaH are numbered 298 to 542. Primes indicate truncated codons.

There is evidence that spontaneous mutations are influenced by DNA context (1, 5, 12, 22, 25, 40). Interpreting the role of short sequence motifs, minor and extended direct repetitions, palindromes, and quasi-palindromes in predisposing particular nucleotides to mutate will be facilitated by analysis of many mutations, occurring in different genetic contexts. Although the collection of A. tumefaciens pcaH or -G strains is small, the mutations were examined for examples of nucleotide sequence patterns that might have contributed to their occurrence. For many mutations, alternative rationales could be proposed, and these were not strikingly persuasive. It seems likely that many of the mutations represent rare events in the panoply of screenable mutations. Of uncertain significance four of the five single-base-pair deletions lost the third nucleotide in the short palindrome (or 2-bp repeat) 5′-GCGC-3′ (pcaH2, pcaH3, pcaG4, and pcaG6 [Fig. 4]). The pcaG4 mutation also perfects an inverted repetition, 5′-GTGCGCGGCAC-3′ with the deletion underlined. The fifth single-base-pair deletion, pcaH4, occurred at the 3′ nucleotide in a 3-bp repeat, possibly due to 5′ to 3′ slipped strand mispairing of the coding strand. Four of the missense mutations, considered the most common types of transition mutations, may have arisen by base modification. Exposure of the pcaH5 nucleotide in the loop of a predicted palindrome (5′-GCGGC-4 nt-GCCGC-3′) may have made it selectively vulnerable to mutation.

The wild-type sequence corresponding to the 88-bp duplication of pcaH8 has short, inverted repeats which span each gap juncture (5′-ACGGCGT-3′ upstream and 5′-TTC GAA-3′ or 5′-TCGAAGGCGA-3′ downstream) as well as short palindromes at each end (5′-TGG CCA-3′ upstream and 5′-GATCCGCTGATC-3′ downstream). In addition, near each endpoint is the direct repetition 5′-GGCG-3′. There is strong evidence that spontaneous deletions are promoted by short direct identities (1, 5). The 92-bp deletion of pcaH10 has a short repetition flanking each end (5′-C-A--G-CTGAT--C-C-3′, where the dashes represent nonidentical bases) as well as very short inverted repeats flanking the gap (5′-CAG-3′ upstream and 5′-CTG-3′ downstream [Fig. 4]). The fact that the pcaH8 duplication and pcaH10 deletion overlap further suggests the mechanism of slipped mispairing: short, noncontiguous sequence repetitions in this region (for example, five repeats of 5′-TGATC-3′ or 5′-CGATC-3) may have contributed to stepwise misalignments or to intragap distance-shortening secondary structures.

Analysis of missense mutations in PcaH and PcaG.

As noted above, the degree of divergence of the A. tumefaciens protomer from that of the Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter homologs is similar to that of the latter two from each other. Thus, it is not unreasonable to apply information gleaned from crystal structures of the Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter enzymes (27, 45) to analysis of Agrobacterium PcaH or -G mutations. Conversely, certain spontaneous PcaH or -G mutations isolated in Agrobacterium may corroborate inferences drawn from crystal structures and guide site-directed mutagenesis of the structurally characterized enzymes.

To provide a framework for analysis of the amino acid substitutions caused by the mutations, Clustal alignment of the α and β chains, respectively, of six other bacterial species with those of A348 was made, and data from the alignments were used to create Fig. 5. Numbering of residues below the A348 polypeptide sequences in this particular figure is sequential from the α to the β subunits, and it follows the numbering used for previous structural analyses in order to facilitate reference to them (7, 27). Consequently, the numbering referred to in the next paragraph does not follow the A. tumefaciens sequence nomenclature of Fig. 4 and Table 2. A few amino acids of the A. tumefaciens A348 subunits are different from those conserved in the other sequences (for details see the legend to Fig. 5). Reflecting the divergence statistics already mentioned, the β subunits required a negligible number of gaps (and none in the A. tumefaciens subunit) to achieve alignment; apparently less divergence was tolerated in the iron-binding subunit.

In the A. tumefaciens protomer, residues critical to structure and function, such as the iron ligands Tyr408, Tyr447, His460, and His462 (27, 45), are conserved. Amino acids that interact directly with the substrate (Thr12, Pro15, Tyr16, Tyr324, Tyr447, Trp449, Arg457, and Ile491) are also strictly conserved as is Gln477, which forms a critical hydrogen bond to Arg457 (28) (Fig. 5). An indentation in the substrate binding cavity has been proposed to be the position from which oxygen interacts with the C-3/C-4 carbon of substrate (27, 28, 45). Residues Ala13 (Gly13 in Acinetobacter), Gly14, Pro15, Tyr16, Val17, Trp400, Tyr408, His462, and iron form the minicavity. All of these residues are conserved in the A. tumefaciens protomer.

All but two of the amino acids altered in the A. tumefaciens mutants are different from those mutated in the PcaH and -G analyses of Acinetobacter (7, 12). The most striking validation of the efficacy of the pcaB positive selection technique and the screening procedure used with A. tumefaciens is the location of mutations pcaH6 and pcaH9 in the translated protein. In the pcaH6 mutant ADO2091, Tyr447, an iron ligand that also rotates to interact with protocatechuate, is converted to Ser447 (Fig. 5). Directed mutants at Tyr447 of the P. putida β chain were constructed to corroborate its role in catalysis (10, 28). The pcaH9 mutant, ADO2093, has an R457H change (Fig. 5). It has been proposed that Arg457 stabilizes development of a negative charge on C-4 of protocatechuate, making it susceptible to nucleophilic attack by oxygen (28). An R457C mutation in Acinetobacter was isolated previously (12). Several residues, among them Gly14, are proposed to orient the active site residue Pro15 so that it can interact with the aromatic ring of the substrate (7, 27). Knockout mutation G14S in ADO2098 (pcaG3) (Fig. 5) may compromise the active-site conformation. It may undermine the function of the putative oxygen-binding minicavity mentioned above as well.

Although heat-sensitive mutants of PcaHG may be characterized by large changes in the denaturation temperature along with minor structural changes, some mutants active only at lower temperature may have an alteration in the active site rather than in their stability (7). In ADO2092 (pcaH7), a P448L mutation led to a heat-sensitive phenotype. Pro448 helps to define the active site pocket (45), and it contributes to the interface between two protomers in the P. putida crystal structure (27). A second heat-sensitive mutant, ADO2099 (pcaG5), has an A123T mutation. In Acinetobacter, a mutation of A123V (12) was also heat sensitive and was interpreted to create structurally destabilizing van der Waals clashes (7).

Pointing to the value of augmenting comparative sequence alignments with spontaneous mutation analysis is the fact that two of the A348 mutations occur at sites not strictly conserved in divergent PcaHGs. The site of the W129R mutation of ADO2100 (pcaG7) is occupied by Ser in the P. putida α chain. Ser129 appears to form a main chain hydrogen bond with the conserved Glu69, which forms one half of a specific charge pair at the α/β interface (27). The other mutation in a nonconserved residue is V426D in ADO2090 (pcaH5), which has uncharged residues in the analogous position in most of the other species' subunits. The mutation may disrupt hydrophobic interactions: in the P. putida enzyme, Val426 is proposed to form part of the α/β interface (27). The V426D change leads to a subtler decrease in enzyme activity, as judged by protocatechuate accumulation by ADO2090 exposed to 4-hydroxybenzoate or quinate compared to strain ADO2091.

DISCUSSION

An endogenous catabolic trickle through the protocatechuate pathway may arise from hydroaromatic intermediates in the biosynthesis of aromatic compounds. The greater tolerance of ADO2077 than of an Acinetobacter pcaB mutant strain toward aromatic and hydroaromatic compounds confers the advantage of decreasing the likelihood of secondary mutations arising during maintainance of the strain and of the concomitant isolation of sibling suppressor mutants. Given the selection conditions used, it is likely that the types of mutations isolated in A. tumefaciens include some that are subtler than those in Acinetobacter, since a slight reduction in activity of the dioxygenase is likely to protect ADO2077.

The most striking difference between the types of secondary mutations arising in Acinetobacter and A. tumefaciens is the number and extent of deletions. In one Acinetobacter study, 25% of the ΔpcaBDK1 suppressor mutants were large deletions which extended equally upstream and/or downstream of pcaB and pcaHG (12). In A. tumefaciens, fewer than 2% of 120 suppressor mutants had undergone a deletion sizable enough (at least 0.46 kb) to delete the Ω marker. That value admittedly underestimates the total number of deletion mutants because it measures only pca deletions that extend in the 3′ direction. It does indicate, however, that the catabolite toxicity at the root of the selection does not a priori cause a disproportionate number of deletions. To circumvent screening the preponderance of nonmissense mutations that would add little to understanding the function of PcaHG, a second study of spontaneous pcaHG mutants in Acinetobacter focused on heat-sensitive mutants, which comprised 5% of the population of 4-hydroxybenzoate-resistant pcaBDK1 mutants (7). In a screen of a similar collection of A. tumefaciens mutants, it was necessary to use a temperature differential of 9°C rather than the 15°C used with Acinetobacter. In spite of this, 3 to 4% of 70 A. tumefaciens mutants screened were heat-sensitive PcaHG mutants, indicating that the same strategy for narrowing the spectrum of pcaHG mutants analyzed should work with the narrower temperature range.

The isolation of unambiguous A. tumefaciens PcaHG mutants that have a clear relationship to structure and function validates the selection method and screening process employed. Its success demonstrates that the positive selection method may have wider applications that go beyond its use in derivatives of Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. Although the competence of ADP1 for natural transformation elevates it to the status of a model experimental organism, certain questions require mutants in particular microbes. Not only does a pcaB mutant afford the potential to generate mutants for structure-function analysis of enzymes and regulatory proteins, it also provides an environmental sleuth and a preliminary assessor of preferred carbon sources, along with the underlying regulatory implications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to W. M. Coco for providing Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP853, to S. K. Farrand for offering A. tumefaciens UIA5, and to L. N. Ornston for encouragement. Additional thanks are due to L. N. Ornston and D. M. Young for critical reading of the manuscript. Preliminary sequence data for Sinorhizobium meliloti were generated by S. R. Long and colleagues at the Department of Biological Sciences, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the Stanford DNA Sequencing and Technology Center (http://cmgm.stanford.edu/∼mbarnett/1xgenome.htm). Concurrent with the preparation of this communication, M. Contzen and A. Stolz prepared a manuscript on sequence analysis of related dioxygenases of Agrobacterium radiobacter. Appreciation is extended to them for open communication during this process.

This investigation was supported by Department of Energy grant DOE88ER13947.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albertini A M, Hofer M, Calos M P, Miller J H. On the formation of spontaneous deletions: the importance of short sequence homologies in the generation of large deletions. Cell. 1982;29:319–328. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schafer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Wiley Interscience; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charles T C, Finan T M. Analysis of a 1600-kilobase Rhizobium meliloti megaplasmid using defined deletions generated in vivo. Genetics. 1991;127:5–20. doi: 10.1093/genetics/127.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chedin F, Dervyn E, Dervyn R, Ehrlich S D, Noirot P. Frequency of deletion formation decreases exponentially with distance between short direct repeats. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:561–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cronin C N, Kim J-H, Fuller J, Zhang X-P, McIntire W S. Organization and sequences of p-hydroxybenzaldehyde dehydrogenase and other plasmid-encoded genes for early enzymes of the p-cresol degradative pathway in Pseudomonas putida NCIMB 9866 and 9869. DNA Seq. 1999;10:7–17. doi: 10.3109/10425179909033930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Argenio D A, Vetting M W, Ohlendorf D H, Ornston L N. Substitution, insertion, deletion, suppression, and altered substrate specificity in functional protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenases. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6478–6487. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6478-6487.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doten R C, Ngai K-L, Mitchell D J, Ornston L N. Cloning and genetic organization of the pca gene cluster from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3168–3174. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.7.3168-3174.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eulberg D, Lakner S, Golovleva L A, Schlomann M. Characterization of a protocatechuate catabolic gene cluster from Rhodococcus opacus 1CP: evidence for a merged enzyme with 4-carboxymuconolactone-decarboxylating and 3-oxoadipate enol-lactone-hydrolyzing activity. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1072–1081. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1072-1081.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frazee R W. Ph.D. thesis. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frazee R W, Livingston D M, LaPorte D C, Lipscomb J D. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the Pseudomonas putida protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase genes. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6194–6202. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6194-6202.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerischer U, Ornston L N. Spontaneous mutations in pcaH and -G, structural genes for protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1336–1347. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1336-1347.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodner B W, Markelz B P, Flanagan M C, Crowell C B, Jr, Racette J L, Schilling B A, Halfon L M, Mellors J S, Grabowski G. Combined genetic and physical map of the complex genome of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5160–5166. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5160-5166.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammer A, Stolz A, Knackmuss H-J. Purification and characterization of a novel type of protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase with the ability to oxidize 4-sulfocatechol. Arch Microbiol. 1996;166:92–100. doi: 10.1007/s002030050361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartnett C, Neidle E L, Ngai K-L, Ornston L N. DNA sequences of genes encoding Acinetobacter calcoaceticus protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase: evidence indicating shuffling of genes and of DNA sequences within genes during their evolutionary divergence. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:956–966. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.956-966.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartnett G, Averhoff B, Ornston L N. Selection of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus mutants deficient in the p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase gene (pobA) a member of a supraoperonic cluster. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6160–6161. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.6160-6161.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartnett G B. Ph.D. thesis. New Haven, Conn: Yale University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harwood C S, Parales R E. The β-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:553–590. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keen N T, Tamaki S, Kobayashi D, Trollinger D. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1988;70:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knauf V C, Nester E W. Wide host range cloning vectors: a cosmid clone bank of an Agrobacterium Ti plasmid. Plasmid. 1982;8:45–54. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(82)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kowalchuk G A, Hartnett G B, Benson A, Houghton J E, Ngai K-L. Contrasting patterns of evolutionary divergence within the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus pca operon. Gene. 1994;146:23–30. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90829-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levinson G, Gutman G A. Slipped-strand mispairing: a major mechanism for DNA sequence evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:203–221. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipscomb J D, Orville A M. Mechanistic aspects of dihydroxybenzoate dioxygenases. In: Sigel H, Sigel A, editors. Metal ions in biological systems. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1992. pp. 243–298. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorite M J, Sanjuan J, Velasco L, Olivares J, Bedmar E J. Characterization of Bradyrhizobium japonicum pcaBDC genes involved in 4-hydroxybenzoate degradation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1397:257–261. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mollet B, Delley M. Spontaneous deletion formation within the β-galactosidase gene of Lactobacillus bulgaricus. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5670–5676. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5670-5676.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohlendorf D H, Lipscomb J D, Weber P C. Structure and assembly of protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase. Nature (London) 1988;336:403–405. doi: 10.1038/336403a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohlendorf D H, Orville A M, Lipscomb J D. Structure of protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa at 2.15 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1994;244:586–608. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orville A M, Lipscomb J D, Ohlendorf D H. Crystal structures of substrate and substrate analog complexes of protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase: endogenous Fe3+ ligand displacement in response to substrate binding. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10052–10066. doi: 10.1021/bi970469f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Overhage J, Kresse A U, Priefert H, Sommer H, Krammer G, Rabenhorst J, Steinbuchel A. Molecular characterization of the genes pcaG and pcaH, encoding protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase, which are essential for vanillin catabolism in Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:951–960. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.951-960.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parke D. Acquisition, reorganization, and merger of genes: novel management of the β-ketoadipate pathway in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;146:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parke D. Application of p-toluidine in chromogenic detection of catechol and protocatechuate, diphenolic intermediates in catabolism of aromatic compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2694–2697. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2694-2697.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parke D. Characterization of PcaQ, a LysR-type transcriptional activator required for catabolism of phenolic compounds, from Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:266–272. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.266-272.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parke D. Construction of mobilizable vectors derived from plasmids RP4, pUC18 and pUC19. Gene. 1990;93:135–137. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90147-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parke D. Supraoperonic clustering of pca genes for catabolism of the phenolic compound protocatechuate in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3808–3817. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3808-3817.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parke D, Ornston L N. Nutritional diversity of Rhizobiaceae revealed by auxanography. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:1743–1750. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parke D, Ornston L N, Nester E W. Chemotaxis to plant phenolic inducers of virulence genes is constitutively expressed in the absence of the Ti plasmid in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5336–5338. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.11.5336-5338.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parke D, Rynne F, Glenn A. Regulation of phenolic catabolism in Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5546–5550. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5546-5550.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prentki P, Kirsch H M. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene. 1984;29:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramos J L, Duque E, Godoy P, Segura A. Efflux pumps involved in toluene tolerance in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3323–3329. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3323-3329.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ripley L S. Frameshift mutation: determinants of specificity. Annu Rev Genet. 1990;24:189–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.001201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schaaper R M, Dunn R L. Spontaneous mutation in the Escherichia coli lacI gene. Genetics. 1991;129:317–326. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.2.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silhavy T J, Berman M L, Enquist L W. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vetting M W, D'Argenio D A, Ornston L N, Ohlendorf D H. Structure of Acinetobacter strain ADP1 protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase at 2.2 Å resolution: implications for the mechanism of an intradiol dioxygenase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7943–7955. doi: 10.1021/bi000151e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams S E, Woolridge E M, Ransom S C, Landro J A, Babbitt P C, Kozarich J W. 3-Carboxy-cis,cis-muconate lactonizing enzyme from Pseudomonas putida is homologous to the Class II fumarase family: a new reaction in the evolution of a mechanistic motif. Biochemistry. 1992;31:9768–9776. doi: 10.1021/bi00155a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zylstra G J, Olsen R H, Ballou D P. Genetic organization and sequence of the Pseudomonas cepacia genes for the alpha and beta subunits of protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5915–5921. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.5915-5921.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]