Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b has been implicated in numerous food-borne epidemics and in a substantial fraction of sporadic listeriosis. A unique lineage of the nonpathogenic species Listeria innocua was found to express teichoic acid-associated surface antigens that were otherwise expressed only by L. monocytogenes of serotype 4b and the rare serotypes 4d and 4e. These L. innocua strains were also found to harbor sequences homologous to the gene gtcA, which has been shown to be essential for teichoic acid glycosylation in L. monocytogenes serotype 4b. Transposon mutagenesis and genetic studies revealed that the gtcA gene identified in this lineage of L. innocua was functional in serotype 4b-like glycosylation of the teichoic acids of these organisms. The genomic organization of the gtcA region was conserved between this lineage of L. innocua and L. monocytogenes serotype 4b. Our data are in agreement with the hypothesis that, in this lineage of L. innocua, gtcA was acquired by lateral transfer from L. monocytogenes serogroup 4. The high degree of nucleotide sequence conservation in the gtcA sequences suggests that such transfer was relatively recent. Transfer events of this type may alter the surface antigenic properties of L. innocua and may eventually lead to evolution of novel pathogenic lineages through additional acquisition of genes from virulent listeriae.

Wall teichoic acids are predominant constituents of the cell envelope of Listeria monocytogenes and other gram-positive bacteria. In Listeria, pronounced diversity in teichoic acid structure and antigenicity is conferred by glycosidic substitutions of the ribitol phosphate units (6, 7, 12, 27, 28). Such substitutions differ among different listerial serotypes. In the pathogenic species L. monocytogenes (the only Listeria species pathogenic to humans), serotype 4b strains are unique in bearing both galactose and glucose substituents on the N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) of teichoic acid (6, 27). This is of interest, as serotype 4b accounts for a large fraction of sporadic infections due to L. monocytogenes and for almost all confirmed food-borne outbreaks of listeriosis (5, 13, 21).

The genetic basis for teichoic acid glycosylation in L. monocytogenes and other species of Listeria remains poorly understood. Recently we described the serogroup 4-specific gene gtcA, which was essential for decoration of cell wall teichoic acids of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b with galactose and glucose. Mutants with insertional mutations in gtcA lacked galactose and had only trace levels of glucose in the teichoic acid (20). Several findings suggest that teichoic acid glycosylations may serve important ecological and virulence functions in L. monocytogenes: glycosylation-impaired mutants of serotype 1/2a and 4b were found to be resistant to serotype-specific phages (26; N. Promadej, F. Fiedler, and S. Kathariou, unpublished data), and gtcA mutants of serotype 4b are impaired in certain aspects of the host cell-pathogen interaction, including invasion of fibroblasts (Promadej et al., unpublished data) and endothelial cell activation (D. A. Drevets and S. Kathariou, unpublished data).

Genetically, the species L. monocytogenes appears to be partitioned in two major clonal groups, which are correlated with the flagellin (H antigen) component of the serotypic designations of Seeliger and Hoehne (23). One group includes strains of serotype 1/2a, 1/2c, 3a, and 3c, whereas the other includes serotypes 1/2b, 3b, and 4b (3, 18). The two clonal groups are characterized by nonoverlapping allelic variants in numerous genetic markers, suggesting strong linkage disequilibrium and an apparent lack of gene flow between the groups. Within L. monocytogenes, sequences homologous to gtcA were found only within serotype 4b and other serogroup 4 strains and were absent from serotypes 1/2b and 3b in the same clonal group (15), suggesting that the distribution of these sequences reflected the presence of serogroup-specific, somatic antigens.

Other Listeria species were found to lack sequences homologous to gtcA, with the notable exception of certain strains of the nonpathogenic species Listeria innocua (15). These unusual L. innocua strains were initially identified because they reacted with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) which otherwise were specific for L. monocytogenes of serotypes 4b, 4d, and 4e (14). In L. monocytogenes serotype 4b, reactivity with these MAbs requires intact glycosylation of wall teichoic acid, i.e., the presence of galactose and glucose as substituents on the GlcNAc of the teichoic acid backbone (20).

L. innocua is the species genetically closest to L. monocytogenes. Even though these two species differ markedly in pathogenicity, they share the same ecological niches in the environment (including food, vegetation, and soil), and in fact L. innocua was not recognized as a species distinct from L. monocytogenes until 1981 (22). In spite of the apparent potential for genetic exchange between L. monocytogenes and L. innocua, such exchanges have not yet been documented. In terms of teichoic acid structure, it is interesting that L. innocua shares the teichoic acid backbone (containing integral GlcNAc) with serogroup 4 L. monocytogenes but typically lacks the glycosylations that characterize serotype 4b of the latter species (6). It is conceivable, therefore, that lateral transfer of the genes conferring these teichoic acid glycosylations may allow L. innocua strains to express serotype 4b-like teichoic acids.

To better understand the distribution and evolution of teichoic acid glycosylation genes in Listeria, we pursued the characterization of the gtcA genomic region in the unusual L. innocua strains which expressed serotype 4b-like surface antigens. Results described in this communication indicate that such L. innocua strains indeed have serotype 4b-like glycosylations in their teichoic acid and support the possibility of a relatively recent transfer of gtcA between serogroup 4 L. monocytogenes and L. innocua, at a genomically equivalent locus. In L. innocua strains which express serotype 4b-like sugar substituents in the teichoic acid, gtcA was found to be functional and essential for teichoic acid glycosylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth media.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were routinely grown in brain heart infusion (Difco) in stationary cultures at 35°C. Growth on agar was on tryptic soy agar (TSA) (Difco) supplemented with yeast extract (0.7%). Hemolytic activity was determined on TSA supplemented with 4% sheep blood (BBL). Escherichia coli was grown in Luria-Bertani broth (Difco) with ampicillin (50 μg/ml). When applicable, antibiotics used for Listeria were streptomycin (1,200 μg/ml), erythromycin (10 μg/ml), and chloramphenicol (7 μg/ml). Antibiotics were purchased from Sigma.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Species and strain | Serotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| L. monocytogenes | ||

| 4b1 | 4b | 20 |

| M44 (Tn916ΔE mutant) | 4b | 20 |

| 4WT | 4b | 20 |

| LM1320 | 4b | R. Kanenaka |

| F4242 | 1/2b | B. Swaminathan |

| 99-468 | 1/2a | R. Kanenaka |

| L. innocua | ||

| F8596 | L. Pine | |

| F8596L | This study | |

| 1F3 (Tn916ΔE mutant) | This study | |

| 4E6 (Tn916ΔE mutant) | This study | |

| 5F1 (Tn916ΔE mutant) | This study | |

| 12G7 (Tn916ΔE mutant) | This study | |

| 14D9 (Tn916ΔE mutant) | This study | |

| 14D9(pKSV7) | This study | |

| 14D9(pNP21) | This study | |

| F7833 | L. Pine | |

| F8735 | L. Pine | |

| 121E9 | R. Kanenaka | |

| 120A1 | R. Kanenaka | |

| SLCC3379 (type strain) | 6a | H. Hof |

| 30-1 | R. Kanenaka | |

| 40-1 | R. Kanenaka | |

| 44-1 | R. Kanenaka | |

| 45-1 | R. Kanenaka | |

| 46-1 | R. Kanenaka | |

| K-10 | R. Kanenaka | |

| 99-248 | W. Lin | |

| E. coli DH5α F− φ180dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK−) supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1 | X. F. Gao |

Transposon mutagenesis.

Strain F8596L, a spontaneously derived streptomycin-resistant derivative of L. innocua F8596, was used as a transposon Tn916ΔE recipient in filter membrane matings done as previously described (15), except that conjugations were done at 22°C overnight. Antibiotics used for selection and maintenance of transconjugants were streptomycin (1,200 μg/ml) and erythromycin (10 μg/ml). Single transconjugants were inoculated into individual wells of 96-well microtiter plates containing 200 μl of brain heart infusion with the antibiotics, incubated at 35°C overnight, and subsequently kept frozen at −70°C.

Screening of mutants with MAbs.

MAbs c74.22, c74.33 and c74.180, which react with serotypes 4b, 4d, and 4e but not with other L. monocytogenes serotypes, have been described before (14). For colony immunoblots with these antibodies, the bacteria were grown at 22°C, transferred to nitrocellulose, and processed as described previously (15).

Biochemical analysis of cell wall composition.

The cell wall composition was determined as described by Fiedler et al. (6). Teichoic acids from L. innocua F8596 and mutant 14D9 were extracted and analyzed as previously described (6, 12).

Listeria phage infection assay.

Listeria genus-specific phage A511 (16) was a gift from M. Loessner. Infections with this phage and determination of adsorption efficiency were done as described previously (26, 31).

DNA manipulation and analysis.

Standard molecular procedures (2) were used unless otherwise indicated. Genomic DNA was extracted from L. monocytogenes and L. innocua as described previously (15). Restriction enzymes were purchased from MBI-Fermentas or from Promega. PCR employed Taq polymerase (Promega), and PCR products were purified with a Geneclean kit (Bio101). PCR to detect the listeriolysin gene hly was done as described previously (8). Plasmids were purified with a Wizard Miniprep kit (Promega). Southern blotting was done to determine Tn916ΔE copy number and for other purposes as indicated, using previously described procedures (15) with the nonradioactive Genius digoxigenin labeling and detection system (Boehringer Mannheim). High-stringency hybridizations were done at 42°C. Nucleotide sequences were determined by automated sequencing at the University of Hawaii Biotechnology Core Facility and analyzed as described previously (20).

To isolate transposon-flanking sequences and identify the transposon insertion site in mutant 14D9, we used single-specific-primer PCR (24) as previously described (20). A 0.5-kb product was amplified and cloned in the pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen), resulting in plasmid pLI1. The cloned fragment was used as a digoxigenin-labeled probe in Southern blots to confirm its location in the transposon-flanking region and was sequenced.

Primers used to amplify different genomic regions of L. innocua F8596 are listed in Table 2. To identify gtcA and the flanking genomic sequences of L. innocua F8596, we used two primers (RHOST and RR4) from the gtcA genomic region of L. monocytogenes 4b1, with the annealing temperature set at 46°C. A product of about 1.1 kb was amplified and cloned in pCR2.1, resulting in plasmid pLI2. The cloned fragment was sequenced on both strands.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used for PCR amplification of genes in the gtcA genomic region of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b and L. innocua F8596

| Primer | Sequence | Position | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| RHOST | 5′ GAA TTC AAA GGG ACA GGC AAC AT 3′ | 3225–3247 | AF072894 |

| RR4 | 5′ GCT GAG TGC GCA AAT TAT TT 3′ | 4336–4355 | AF072894 |

| 1P1ST | 5′ CAC ATA GAA AGA AGT TAT 3′ | 3512–3529 | AF072894 |

| 11N | 5′ ACA CGT AGT TCA GTA CAA GC 3′ | 3916–3935 | AF072894 |

| 11R6 | 5′ CGT GTC GAA ATC TCT TCT GA 3′ | 4210–4229 | AF072894 |

| RR8 | 5′ ATC GCT TTG TTT CGG 3′ | 3387–3401 | AF072894 |

| 2P3 | 5′ GTA ACG TCT CAT ATA TAG GGA G 3′ | 3434–3454 | AF033015 |

| CP1 | 5′ CAC AGA AGC GAT ACG ATG A 3′ | 4347–4365 | AF033015 |

To construct probes internal to rho, gtcA, rpmE, and locus II of L. innocua F8596, we used the primer pairs (M13F and RR8, 1P1ST and 11N, 11R6 and RR4, and 2P3 and CP1, respectively) listed in Table 2. The template was genomic DNA of L. innocua F8596, with the exception of the rho PCR fragment, which was obtained using pLI2 as the template.

Complementation of the mutant in trans.

The gtcA-containing shuttle plasmid pNP21 (20) was used for genetic complementation of mutant 14D9 in trans. Preparation of Listeria electrocompetent cells and electroporation were done as described previously (20). Transformants were selected on TSA–0.7% yeast extract plates containing chloramphenicol (7 μg/ml) for 2 to 3 days at 30°C.

Strain typing by REP-PCR and analysis of 16S rDNA.

Repetitive extragenic palindrome (REP)-based PCR (REP-PCR) was done using freshly extracted genomic DNA as the template and the REP primers and PCR conditions described by Jeršek et al. (11). PCR products were visualized following electrophoresis in an 18-cm gel. To determine 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequences of L. innocua F8596, we used primers BACT8-27F (5′ AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTT AG 3′) and 1510-1492R (5′ RGY TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T 3′), corresponding to nucleotides 8 to 27 and 1492 to 1510, respectively, in the E. coli 16S rDNA sequence. The resulting 1.5-kb PCR product was recovered from the gel, purified with the Geneclean kit and used for nucleotide sequence determinations.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data for the 16S rDNA 5′ region, 16S rDNA 3′ region, and gtcA genomic region of L. innocua F8596 have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF201855, AF201854, and AF160251, respectively.

RESULTS

Bacteriologic and taxonomic characterization of L. innocua strains with serogroup 4-like genes and surface antigens.

Earlier studies suggested that three unusual strains of L. innocua, F8596, F7833, and F8735, reacted with MAbs (c74.22, c74.33, and c74.180) which otherwise reacted only with serotype 4b, 4d, and 4e L. monocytogenes (14). Furthermore, these L. innocua strains also harbored genomic sequences with homology to sequences which otherwise appeared to be unique to L. monocytogenes serogroup 4 (15, 20).

These strains were completely nonhemolytic, as would be expected of L. innocua. To exclude the possibility that they may represent nonhemolytic variants of L. monocytogenes, we used PCR to detect the hemolysin (listeriolysin) gene hly. Such PCRs did not yield any product, suggesting the absence of the corresponding sequences. In addition, Southern blots with an hly probe failed to yield any hybridizing bands using these strains, even under low-stringency conditions (data not shown).

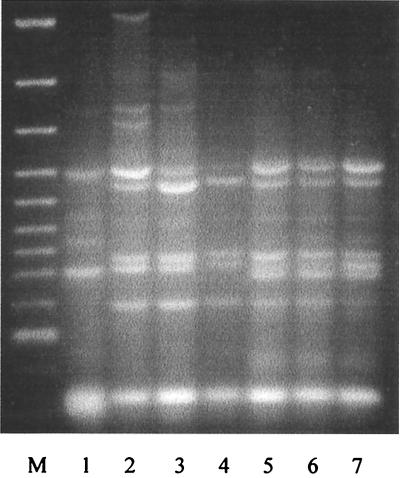

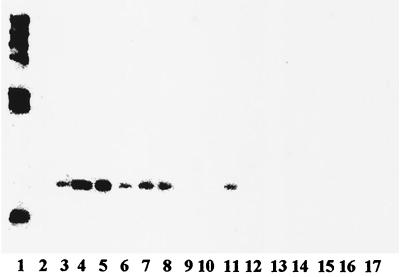

To evaluate the genotypic similarity among these strains, as well as between them and other L. innocua strains, we employed REP-PCR, which is based on the distribution of a class of repetitive elements (REPs) in the genome (29). F8596, F8735, and F7833 were found to have virtually indistinguishable REP-PCR patterns (Fig. 1). The patterns were highly similar to those produced by three other L. innocua strains (including the type strain) and were distinct from the REP-PCR pattern of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b. In particular, PCR fragments of 0.6, 0.75, and 1.1 kb were prominent when the templates were genomic DNAs from F8596, F8735, and F7833, as well as from the other three L. innocua strains, but were absent when DNA from L. monocytogenes 4b was used as the template (Fig. 1). The REP-PCR data suggest that F8596, F8735, and F7833 belong to one genotypic cluster within L. innocua.

FIG. 1.

REP-PCR profiles of Listeria spp. Lane M, molecular marker (fragment sizes are, from top to bottom, 3.0, 2.0, 1.5, 1.2, 1.0, 0.9, 0.8, 0.7, 0.6, 0.5, and 0.4 kb); lane 1: L. monocytogenes 4b1; lane 2, L. innocua SLCC3379 (type strain); lane 3, L. innocua 121E9; lane 4, L. innocua 99-248; lane 5, L. innocua F7833; lane 6, L. innocua F8596; lane 7, L. innocua F8735. REP-PCR was done as described in Materials and Methods.

We chose L. innocua F8596 as the prototype strain for further molecular studies. 16S rDNA sequence analysis revealed that the sequences (459 and 560 bp at the 5′ and 3′ regions of the 16S rDNA sequence [accession no. AF201855 and AF201854, respectively]) had 99.8 and 100% identity with the L. innocua sequences in the database (accession no. X98527). At nucleotide positions 357, 376, and 390 (accession no. AF201854) in the 3′ portion of 16S rDNA, which appear to differentiate between L. innocua (accession no. X98527) and L. monocytogenes (accession no. X98530), the corresponding nucleotides of F8596 were identical to those of L. innocua (data not shown).

Identification of the gtcA genomic region of L. innocua F8596.

PCR using primers from the gtcA genomic region of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b and standard conditions (annealing temperature of 48°C) did not produce a product from L. innocua F8596, even though homologous sequences were detected with Southern blots (data not shown). PCR using the same primers at a lower annealing temperature (46°C), however, produced a product of 1,083 bp from F8596, which was subsequently cloned and sequenced.

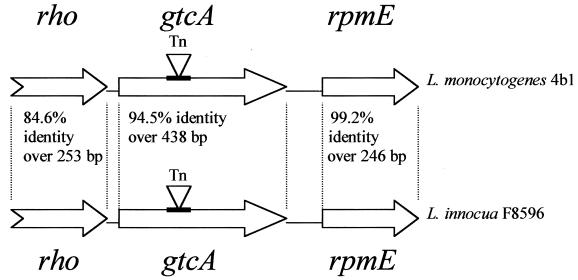

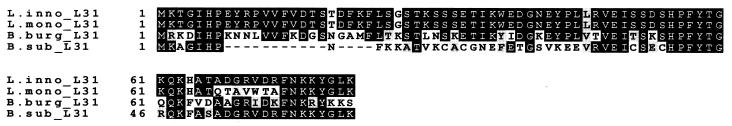

ORF analysis.

The 1,083-bp genomic region of L. innocua F8596 had 93.9% identity to the corresponding region in L. monocytogenes 4b1. Three open reading frames (ORFs) were identified, rho (partial sequence), gtcA, and rpmE, in the same order as in L. monocytogenes serotype 4b (Fig. 2). On the basis of sequence similarity to other genes in the database, the partial rho gene and rpmE are expected to encode the putative transcription termination factor Rho and ribosomal protein L31, respectively, similarly to the corresponding sequences in L. monocytogenes serotype 4b (20). The available 3′ portion of rho of L. innocua F8596 had 84.6% identity over 253 bp to its counterpart in L. monocytogenes 4b1 (Fig. 2). The deduced 84-amino-acid portion of the Rho factor, however, was identical in the two strains. The gtcA coding sequence had 94.5% identity over its entire length (438 bp) to its counterpart in L. monocytogenes 4b1, and only one amino acid substitution was detected in the 17.4-kDa deduced gene product (Glu75 instead of Asp75). The rpmE coding sequence had 99.2% identity over 243 bp to its counterpart in L. monocytogenes 4b1. The deducted amino acid sequences (81 amino acids), however, diverged in the C terminus (residues 67 to 73) due to two apparent frameshift mutations which resulted in QTAVWTA in L. innocua F8596 instead of ADGRVDR in L. monocytogenes 4b1 (Fig. 3). The G+C content of gtcA in L. innocua F8596 was 30%, which is noticeably lower than the overall value of 38% for L. innocua. On the other hand, the available sequences of rho and rpmE had G+C values of 37 and 40%, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Characterization of ORFs in the gtcA genomic regions of L. monocytogenes 4b1 (serotype 4b) (accession no. AF072894) and L. innocua F8596 (accession no. AF160251).

FIG. 3.

Multiple-sequence alignment (CLUSTAL) of the deduced sequences of ribosomal protein L31 of L. innocua (L. inno) F8596 (accession no. AF160251), L. monocytogenes (L. mono) 4b1 (accession no. AF072894), Borrelia burgdorferi (B. burg) (accession no. AE001133), and Bacillus subtilis (B. sub) (accession no. X73124).

gtcA is functional in L. innocua F8596 and is essential for teichoic acid glycosylation and MAb reactivity.

L. innocua F8596, F8537, and F7833 were first noticed because they reacted with the serotype-specific MAbs c74.22, c74.33, and c74.180 (14). In L. monocytogenes serotype 4b, insertional inactivation of gtcA resulted in the c74.22-negative phenotype (20). We pursued, therefore, the generation of c74.22-negative mutants of L. innocua F8596, in order to determine whether such mutants would have insertions in the gtcA gene as well and, if this was the case, in order to evaluate the possible function(s) of gtcA in this strain. Screening of about 2,200 Tn916ΔE mutants with MAb c74.22 identified six which were c74.22 negative. Of these, five (1F3, 4E6, 5F1, 12G7, and 14D9) were found to have insertions in the gtcA region, using a gtcA probe in Southern blotting. Southern blotting using the transposon probe revealed the presence of a single copy number of Tn916ΔE in mutants 4E6, 5F1, and 14D9 (data not shown).

The single-copy mutant 14D9 was chosen for further studies. Sequence analysis of the transposon-flanking region revealed that the insertion was inside the coding region of gtcA, between nucleotides 484 and 485 (accession no. AF160251). The transposon target sequence, TTTTCTAATAAAAA, was the same as that targeted in other Tn916 and Tn916ΔE mutants of L. monocytogenes 4b1 (20) and were similar to the Tn916 preferred target sites reported for other gram-positive bacteria (17).

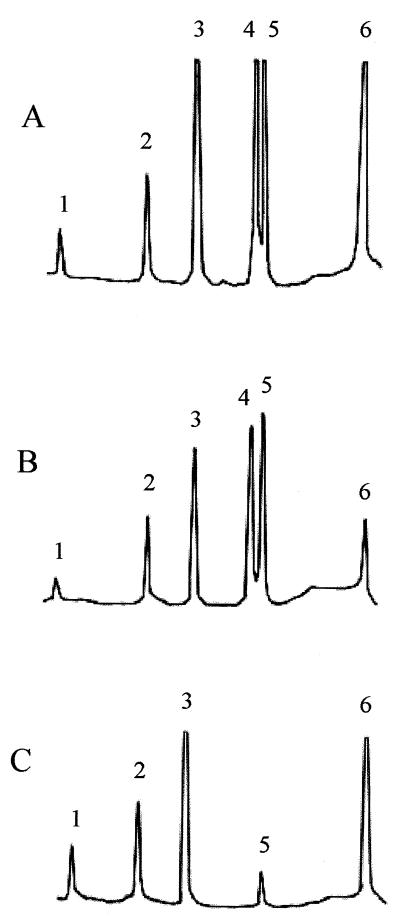

Biochemical analysis of the teichoic acid composition of 14D9 was pursued to determine whether the insertion affected the teichoic acid components. The wild-type parental strain, L. innocua F8596, was found to be indistinguishable from L. monocytogenes serotype 4b in regard to teichoic acid composition (Fig. 4). Identical data (not shown) were obtained with F7833 and F8735. GlcNAc was present in the teichoic acid backbone, with galactose and glucose substituents, unlike the case for typical L. innocua strains, which have GlcNAc in the teichoic acid backbone but lack the simultaneous presence of both galactose and glucose (6). Inactivation of gtcA in mutant 14D9 was accompanied by marked teichoic acid glycosylation defects, identical to those observed in previously characterized gtcA mutants of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b (20). Galactose could not be detected in the teichoic acid of 14D9, and glucose was markedly reduced in amount. GlcNAc and other teichoic acid components were not affected (Fig. 4). Peptidoglycan appeared to be normal (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Teichoic acid compositions of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b strain 4WT (A), L. innocua F8596 (B), and mutant 14D9 (C). Peaks: 1, glycerol; 2, anhydroribitol; 3, ribitol; 4, galactose; 5, glucose; 6, glucosamine. Teichoic acids were prepared and analyzed as described previously (6, 12, 27). The teichoic acid composition of strains F7833 and F8735 was identical to that of F8596.

In strain F8596, gtcA is essential for phage A511 sensitivity.

Screening of mutant 14D9 with the Listeria-specific phage A511 showed that the mutant was resistant to phage infection. The efficiency of A511 plaque formation by 14D9 was less than 1.5 × 10−3 of that obtained with wild-type bacteria. The resistance of 14D9 to A511 may be due to failure of the phage to adsorb, since adsorption efficiency was reduced 28-fold (Table 3). The resistance of 14D9 to phage A511 was unexpected, as this phage appears to utilize peptidoglycan as a receptor (30). In addition, this phage infects listeriae of different species and serotypes (16). Since peptidoglycan was not affected in 14D9, we may conclude that teichoic acid glycosylation is required for proper exposure or conformation of the receptor determinants on the peptidoglycan. Interestingly, gtcA mutants of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b were also A511 resistant (the efficiency of plaque formation was less than 10−3 of that obtained with the wild type), suggesting that glycosylation of serotype 4b-like teichoic acids is essential for infection by the Listeria genus-specific phage A511.

TABLE 3.

Phage A511 adsorption deficiency of mutant 14D9

| Organism | Phage A511 adsorption (PFU ml−1)a |

|---|---|

| L. monocytogenes 4b1 | 3.7 × 104 |

| L. innocua | |

| F8596 | 3.0 × 105 |

| 14D9 | 8.4 × 106 |

| 14D9(pKSV7) | 7.9 × 106 |

| 14D9(pNP21) | 1.5 × 105 |

Adsorption of phage A511 was measured by determining the number of PFU remaining in the supernatant of a mixture containing the phage A511 (8.6 × 106 PFU) and the indicated strain (ca. 1 × 108 CFU), as described in the text. 14D9(pKSV7) and 14D9(pNP21) are the mutant 14D9 harboring the cloning vector pKSV7 and a recombinant pKSV7 with the gtcA gene of L. monocytogenes 4b1, respectively. Results are averages from two experiments.

gtcA of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b can complement the mutant phenotypes of the L. innocua F8596 gtcA mutant.

Plasmid pNP21, which harbors gtcA of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b on the shuttle vector pKSV7 (20), and pKSV7 alone were electroporated into mutant 14D9. The resulting strains were grown in the presence of chloramphenicol at 30°C, a temperature which permits both replication of the temperature-sensitive plasmid (25) and optimal expression of the serotype 4b-specific surface antigens (14). Reactivity of the mutant with c74.22 was partially restored in the presence of pNP21, whereas constructs with the vector pKSV7 alone remained negative (data not shown). Furthermore, the complemented strain recovered sensitivity to phage A511, whereas the constructs with the vector pKSV7 alone were still phage resistant (Table 3). These findings suggest that the gtcA gene of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b can complement in trans the mutant phenotypes conferred by inactivation of gtcA in L. innocua F8596.

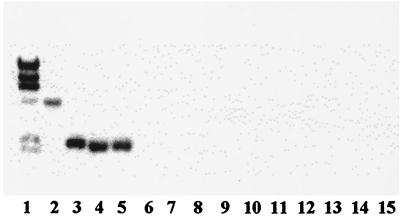

Identification of gtcA sequences in c74.22-negative L. innocua.

A probe derived from gtcA of L. innocua F8596 was used in Southern blots of a panel of 13 L. innocua strains. Interestingly, in addition to the three strains (F8596, F8735, and F7833) that reacted with MAb c74.22, two additional strains (121E9 and 99-248), which were negative with c74.22, were found to harbor gtcA homologues in their genomes (Fig. 5). Since the latter strains appeared to belong to a REP-PCR genotypic cluster separate from that of the c74.22-positive L. innocua strains (Fig. 1), we can conclude that at least two separate L. innocua lineages harbor gtcA homologues, even though only one (comprising F8596, F8735, and F7833) expresses the c74.22-specific surface antigen. In strains such as 121E9 and 99-248, gtcA was cryptic, not being associated with a known phenotype.

FIG. 5.

Southern blot of EcoRI-digested genomic DNAs from different L. innocua and L. monocytogenes strains with a gtcA probe from L. innocua F8596. Lane 1, λ molecular size markers (fragment sizes are, from the top to bottom, 23, 9.4, 6.6, 4.4, 2.3, 2.0, and 0.56 kb); lanes 2 to 4, L. monocytogenes strains F4242 (serotype 1/2b), 4b1 (serotype 4b), and LM1320 (serotype 4b), respectively; lanes 5 to 17, L. innocua strains F8596, F8735, F7833, 121E9, 120A1, SLCC3379, 99-248, 30-1, 40-1, 44-1, 45-1, 46-1, and K-10, respectively. With the exception of F8596, F8735, and F7833 (lanes 5 to 7), the only other L. innocua strains that yielded a signal were 121E9 (lane 8) and 99-248 (lane 11). The rather weak signal in lane 6 reflected relative small amounts of DNA.

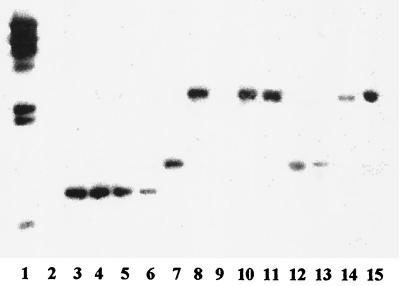

Possible reasons for the c74.22-negative phenotype of strains 121E9 and 99-248 may be that gtcA is not functional in these strains or, alternatively, that additional genes may be required for expression of the teichoic acid-associated surface antigens recognized by c74.22. Introduction of the gtcA gene of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b into these strains in trans on plasmid pKSV7 failed to render them positive with c74.22 (data not shown), suggesting that gtcA alone is not sufficient for expression of the serotype-specific surface antigen and reactivity with these antibodies. In earlier studies we identified another genomic region (locus II) of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b, which was found to be specific to serotype 4b-4d-4e as well as to F8596, F8735, and F7833 (15). Probing the same panel of L. innocua strains used for the Southern blot shown in Fig. 5 with a probe derived from locus II revealed that only F8596, F8735, and F7833 harbored homologous sequences (Fig. 6). All other strains, including the c74.22-negative strains that harbored gtcA homologues, were negative with the locus II probe (Fig. 6). These results suggest that expression of serotype 4b-like surface antigens is a unique property of a unique L. innocua lineage that harbors gtcA as well as at least one additional serogroup 4-specific locus.

FIG. 6.

Southern blot of EcoRI-digested genomic DNAs from different L. innocua and L. monocytogenes strains with a probe derived from locus II of L. innocua F8596. Lane 1, λ molecular size markers, as described in the legend for Fig. 4; lane 2, L. monocytogenes LM1320 (serotype 4b); lanes 3 to 15, L. innocua strain F8596, F8735, F7833, 121E9, 120A1, 44-1, SLCC3379, 99-248, 30-1, 40-1, 45-1, 46-1, and K-10, respectively. Of the L. innocua strains, only F8596, F8735, and F7833 (lanes 3 to 5) produced signals. The hybridizing band of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b is larger than those of F8596, F8735, and F7833. The probe was derived from PCR using F8596 genomic DNA as the template and primers 2P3 and CP1, as shown in Table 2 (accession no. AF033015).

gtcA of L. innocua F8596 represents a monocistronic serogroup 4-specific cassette.

DNA sequence analysis of the available rho sequence upstream of gtcA in L. innocua F8596 suggested that this sequence had diverged substantially (84.6% identity) from its counterpart in L. monocytogenes serotype 4b, in contrast to the observed conservation of gtcA (94.5% identity). To determine whether the rho sequence of F8596 represented a serotype 4b-like sequence that had undergone divergence or, alternatively, was typical of the rho sequences endemic in L. innocua, Southern blotting of a panel of L. innocua strains was done using the F8596 rho portion as a probe. The probe did not produce detectable signals with L. monocytogenes serotype 4b in high-stringency hybridizations (Fig. 7), as expected on the basis of the sequence divergence between the two rho sequences (84.6% identity). L. monocytogenes serotype 1/2a also failed to yield a signal with the rho probe from L. innocua F8596. In contrast, all screened L. innocua strains harbored homologues to the F8596 rho (Fig. 7), suggesting that in F8596, gtcA is flanked upstream by typical L. innocua sequences.

FIG. 7.

Southern blot of EcoRI-digested genomic DNAs from different L. innocua and L. monocytogenes strains with a rho probe from L. innocua F8596. Lane 1, λ molecular size markers, as described for Fig. 4; Lane 2, L. monocytogenes 4b1 (serotype 4b); lanes 3 to 8, L. innocua strain F8596, F8735, F7833, 121E9, 120A1, and SLCC3379, respectively; lane 9, L. monocytogenes 99-468 (serotype 1/2a), lanes 10 to 15, L. innocua strains 30-1, 40-1, 44-1, 45-1, 46-1, and K-10, respectively. The L. innocua F8596 rho probe hybridizes with all other L. innocua strains but not with L. monocytogenes. Three distinct EcoRI restriction fragment length polymorphisms are seen within L. innocua with this probe.

The gene rpmE, immediately downstream of gtcA, was highly conserved among different L. monocytogenes serotypes (20) as well between L. monocytogenes serotype 4b and L. innocua F8596 (99% identity). A probe specific to rpmE hybridized with all screened L. innocua and L. monocytogenes strains (data not shown). Thus, the combined Southern blot and nucleotide sequence data suggest that in L. innocua F8596, gtcA represents a monocistronic cassette that is serogroup 4 specific and is flanked by sequences not specific or unique to serogroup 4.

DISCUSSION

L. innocua is genetically and bacteriologically the species closest to L. monocytogenes, but it is notably nonpathogenic to humans and other animals. Horizontal transfer of genetic determinants between the two species would be expected to take place and could be of special interest in terms of elucidating the evolution of pathogenicity and virulence in Listeria. However, to date evidence for such transfer has been lacking. The results described in this work can be best explained as the outcome of horizontal transfer of a serotype-specific gene cassette between one lineage of L. monocytogenes (serogroup 4) and a lineage of L. innocua, which we designate lineage I and which includes strains F8596, F7833, and F8735. The strong conservation of the gtcA genes in L. monocytogenes serotype 4b and L. innocua F8596 (94.5% identity) suggests a relatively recent transfer of gtcA sequences between L. monocytogenes serotype 4b and L. innocua lineage I. Since all screened strains of L. monocytogenes serogroup 4 harbor the gene, whereas only a subpopulation of L. innocua does so, the direction of transfer would be more likely to have been from L. monocytogenes serogroup 4 to L. innocua than vice versa.

An alternative hypothesis, that gtcA was present in a common L. monocytogenes-L. innocua ancestor and was subsequently maintained only in selected lineages, is less likely, as nucleotide sequence divergence would be expected to be substantially higher under such conditions. The same reason renders less likely the hypothesis that gtcA was transferred independently, from a common source, to L. monocytogenes serogroup 4 and to L. innocua lineage I, unless one also presumes relatively recent transfers to multiple serotypes (4a, 4b, 4c, 4d, and 4e) as well as to L. innocua lineage I.

Recent data from our laboratory revealed that within L. monocytogenes, strains other than those of serogroup 4 harbor apparent gtcA alleles, although the genetic divergence of these alleles from the serotype 4b sequences is significant (79 to 80% in serotypes 1/2a and 1/2b) (Z. Lan and S. Kathariou, unpublished data). Such data suggest that these gtcA alleles may be of different origin than the sequences detected in serogroup 4 and L. innocua lineage I. We presently do not know the ultimate origin(s) of gtcA sequences in Listeria. The relatively low G+C content of the sequences (20; Lan and Kathariou, unpublished data), which differs from that characteristic of the overall Listeria genome, may be indicative of a nonlisterial origin(s), as speculated for surface polymer glycosylation genes of other bacteria as well (1).

On the basis of present data it is not clear what the possible advantage(s) of the acquisition of gtcA may be for L. innocua. Sugar substituents on the teichoic acid have been shown to be essential for phage adsorption in L. monocytogenes (26, 30; Promadej et al., unpublished data), and the serotype 4b-like teichoic acid of L. innocua lineage I may confer some yet-unidentified selective advantages to the microorganism in terms of phage infection. Teichoic acid glycosylation may also affect other surface-related attributes of the microorganism (e.g., attachment to surfaces and biofilm formation) and other aspects of the adaptive physiology of the bacteria, especially under conditions of environmental stress.

Although gtcA was found to be essential for glycosylation of the serotype 4b-like teichoic acid of L. innocua F8596, it is likely not acting alone. This is suggested by the identification of strains of L. innocua which harbored cryptic gtcA sequences and lacked the serotype 4b-like glycosylation. Furthermore, unlike all other L. innocua strains which we examined, lineage I harbors additional serotype-specific sequences (locus II) that are otherwise harbored only by L. monocytogenes serotypes 4b, 4d, and 4e (15). It is reasonable to postulate, therefore, that L. innocua strains with serotype 4b-like teichoic acid glycosylation have acquired not only gtcA but additional sequences (locus II and possibly others, yet unidentified) from L. monocytogenes serogroup 4.

Our molecular data indicated that in lineage I of L. innocua and in L. monocytogenes serotype 4b, gtcA is integrated as a monocistronic gene cassette in the rho-rpmE region of the genome. One may speculate that the rpmE locus, which is highly conserved between L. monocytogenes and L. innocua, may have served as a target for a recombination system, perhaps phage mediated, that resulted in the integration of gtcA in this region. The sequence information presently available, however, does not provide evidence for phage involvement in the introduction of gtcA, and such ideas remain speculative.

L. monocytogenes serotype 4b may have special pathogenesis-related features, being responsible for the majority of outbreaks of listeriosis (as well as a large fraction of sporadic cases). In many bacterial pathogens, surface carbohydrates play critical roles in host cell recognition and adherence, and in fact surface galactose has been shown to serve as a ligand for interactions of L. monocytogenes with certain host cells (4, 9; Promadej et al., unpublished data).

Although the unique L. innocua lineage described here possesses serotype 4b-like sugars on the teichoic acid moiety, it would still be expected to be nonpathogenic, since the virulence-essential hemolysin (listeriolysin) gene hly (19) appears to be absent. Nonetheless, these strains are of special interest in terms of the evolution of listerial pathogenesis. For instance, their serotype 4b-like teichoic acid determinants can serve as receptors for transducing serotype 4b-specific phages, examples of which have been recently described (10). The sugars on the teichoic acid moiety are essential for phage adsorption of serotype-specific phages of L. monocytogenes (26, 30; Promadej et al., unpublished data). Strains such as those of lineage I may represent an early step in the emergence of novel pathogenic lineages of Listeria, as in the course of time and under appropriate selection regimes, virulence genes from L. monocytogenes may be transferred (e.g., by transduction) and stabilized into the genomes of initially nonpathogenic strains.

In the past 15 years, extensive work has been performed on the genetic and cell biologic aspects of listerial pathogenesis (13, 19). In contrast, mechanisms underlying the evolution of virulence in this genus, which contains both pathogenic and nonpathogenic species and is widely encountered in the environment, have not been investigated. Recently, the European Commission funded the complete sequencing of the genomes of L. monocytogenes (strain EGD of serotype 1/2a) and of L. innocua, and the projects are now complete, although the sequences have not yet been released (http://www.pasteur.fr/recherche/unites/gmp /Gmp_projects.html#lm/). The availability of these genome sequencing data to the international scientific community will promote the establishment of novel approaches to the study of the evolution of virulence in Listeria. Genetic and bacteriologic studies of relevant model systems, such as the L. innocua lineage described here, are expected to complement such evolutionary investigations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by U.S. Department of Agriculture Competitive Research Initiative AAFS grant 99-35201-8183 and by ILSI-North America.

We thank M. Loessner (Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany) for providing phage A511 and all of the investigators for providing bacterial strains as indicated in Table 1. We thank Ella Meleshkevitch for REP-PCR. We thank Nattawan Promadej, Xiang-He Lei, Edward Lanwermeyer, and all other members of our laboratories for valuable feedback and support throughout the course of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allison G E, Verma N K. Serotype-converting bacteriophages and O-antigen modification in Shigella flexneri. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01646-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J D, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bibb W F, Gellin B G, Weaver R, Schwartz B, Plikaytis B D, Reeves M W, Pinner R W, Broome C V. Analysis of clinical and food-borne isolates of Listeria monocytogenes in the United States by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and application of the method to epidemiologic investigations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2133–2141. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.7.2133-2141.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowart R E, Lashmet J, McIntosh M E, Adams T J. Adherence of a virulent strain of Listeria monocytogenes to the surface of a hepatocarcinoma cell line via lectin-substrate interaction. Arch Microbiol. 1990;153:282–286. doi: 10.1007/BF00249083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farber J M, Peterkin P L. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:476–511. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.476-511.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiedler F, Seger J, Schrettenbrunner A, Seeliger H P. The biochemistry of murein and cell wall teichoic acids in the genus of Listeria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1984;5:360–376. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujii H, Kamisango K, Nagaoka M, Uchikara K, Sekikawa I, Yamamoto K, Azuma I. Structural study of teichoic acids of Listeria monocytogenes types 4a and 4d. J Biochem. 1985;97:883–891. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golsteyn T, King E, J, R K, Burchak J, Gannon V P J. Sensitive and specific detection of Listeria monocytogenes in milk and ground beef with the polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2576–2580. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.9.2576-2580.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzman C A, Rohde M, Chakraborty T, Domann E, Hudel M, Wehland J, Timmis K N. Interaction of Listeria monocytogenes with mouse dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3665–3673. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3665-3673.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodgson D A. Generalized transduction of serotype 1/2 and serotype 4b strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:312–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeršek B, Tcherneva E, Rijpens N, Herman L. Repetitive element sequence-based PCR for species and strain discrimination in the genus Listeria. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;23:55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1996.tb00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamisango K, Fujii H, Okumura H, Saiki I, Araki Y, Yamamura Y, Azuma I. Structural and immunochemical studies of teichoic acid of Listeria monocytogenes. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1983;93:1401–1409. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kathariou S. Pathogenesis determinants of Listeria monocytogenes. In: Cary J W, Linz J E, Bhatnagar D, editors. Microbial foodborne diseases. Lancaster, Pa: Technomics Publishing Co., Inc.; 2000. pp. 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kathariou S, Mizumoto C, Allen R D, Fok A K, Benedict A A. Monoclonal antibodies with a high degree of specificity for Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3548–3552. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3548-3552.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lei X-H, Promadej N, Kathariou S. DNA fragments from regions involved in surface antigen expression specially identify Listeria monocytogenes serovar 4 and a subset thereof: cluster IIB (serotype 4b, 4d, and 4e) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1077–1082. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1077-1082.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loessner M J, Busse M. Bacteriophage typing of Listeria species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1912–1918. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1912-1918.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu F, Churchward G. Tn916 target DNA sequences bind the C-terminal domain of integrate protein with different affinities that correlate with transposon insertion frequency. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1938–1946. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.1938-1946.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piffaretti J C, Kressebuch H, Aeschbacher M, Bille J, Bannerman E, Musser J M, Selander R K, Rocourt J. Genetic characterization of clones of the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes causing epidemic disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3818–3822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Portnoy D A, Chakraborty T, Goebel W, Cossart P. Molecular determinants of Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1263–1267. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1263-1267.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Promadej N, Fiedler F, Cossart P, Dramsi S, Kathariou S. Cell wall teichoic acid glycosylation in Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b requires gtcA, a novel, serotype-specific gene. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:418–425. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.418-425.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuchat A, Swaminathan B, Broome C V. Epidemiology of human listeriosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:169–183. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seeliger H P. Nonpathogenic listeriae: L. innocua sp. n. Zentbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A. 1981;249:487–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seeliger H P, Hoehne K. Serotypes of Listeria monocytogenes and related species. Methods Microbiol. 1979;13:31–49. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shyamala V, Ferro-Luzzi Ames G. Genome walking by single-specific primer polymerase chain reaction: SSP-PCR. Gene. 1989;84:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith K, Youngman P. Use of a new integrational vector to investigation compartment-specific expression of the Bacillus subtilis spoIIM gene. Biochimie. 1992;74:705–711. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(92)90143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tran H L, Fiedler F, Hodgson D A, Kathariou S. Transposon-induced mutations in two loci of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 1/2a result in phage resistance and lack of N-acetylglucosamine in the teichoic acid of the cell wall. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4793–4798. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.4793-4798.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uchikawa K, Sekikawa I, Azuma I. Structural studies on teichoic acids cell walls of several serotypes of Listeria monocytogenes. J Biochem. 1986;99:315–327. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ullmann W W, Cameron J A. Immunochemistry of the cell walls of Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol. 1969;98:486–493. doi: 10.1128/jb.98.2.486-493.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Versalovic J, Koeuth T, Lupski J R. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6823–6831. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wendlinger G, Loessner M J, Scherer S. Bacteriophage receptors on Listeria monocytogenes cells are the N-acetylglucosamine and rhamnose substituents of teichoic acids or the peptidoglycan itself. Microbiology. 1996;142:985–992. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-4-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng W, Kathariou S. Host-mediated modification of Sau3AI restriction in Listeria monocytogenes: prevalence in epidemic-associated strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3085–3089. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3085-3089.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]