Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy represents a landmark advance in personalized cancer treatment. CAR-T strategy generally engineers T cells from a specific patient with a new antigen-specificity, which has achieved considerable success in hematological malignancies, but scarce benefits in solid tumors. Recent studies have demonstrated that tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) cast a profound impact on the immunotherapeutic response. The immunosuppressive landscape of TIME is a critical obstacle to the effector activity of CAR-T cells. Nevertheless, every cloud has a silver lining. The immunosuppressive components also shed new inspiration on reshaping a friendly TIME by targeting them with engineered CARs. Herein, we summarize recent advances in disincentives of TIME and discuss approaches and technologies to enhance CAR-T cell efficacy via addressing current hindrances. Simultaneously, we firmly believe that by parsing the immunosuppressive components of TIME, rationally manipulating the complex interactions of immunosuppressive components, and optimizing CAR-T cell therapy for each patient, the CAR-T cell immunotherapy responsiveness for solid malignancies will be substantially enhanced, and novel therapeutic targets will be revealed.

Keywords: Tumor immune microenvironment, immunotherapy, chimeric antigen receptor T cell, immunosuppression network, solid tumors

1. Introduction

The past decade has witnessed a revolutionary evolution in the application of immunology to oncology treatment. Immunotherapy has made striking advances in malignancies, far outperforming conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Frustratingly, the immunosuppressive properties of the tumor microenvironment (TME) pose the challenge of limited clinical efficacy and severe side effects to tumor immunotherapy 1. Priming the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) is a critical next step in scaling up the success of current immunotherapies 2. Emerging evidence suggests that the effectiveness of immunotherapy can be maximized by addressing the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment 3, 4. Hence, a more detailed dissection and description of immunosuppression in TIME and a deeper understanding of the tumor immunosuppressive profile are necessary for the development and optimization of novel and effective cancer immunotherapy.

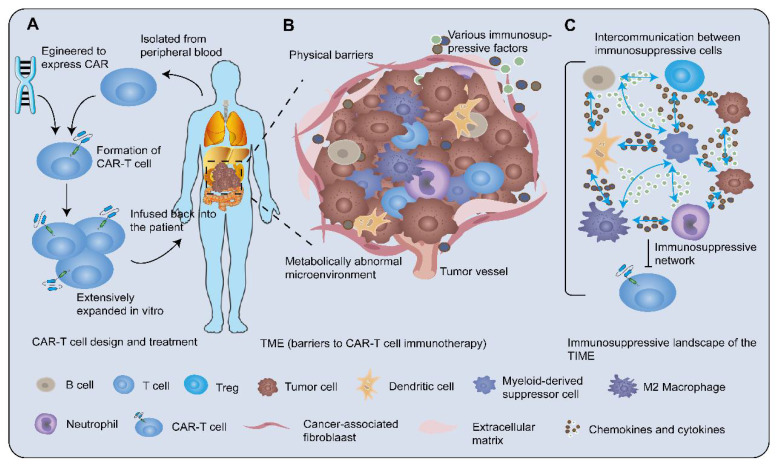

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy is novel immunotherapy through genetically engineered T cells to express CAR targeting molecules. CAR-T cell therapy aims at introducing CARs genes into patient-derived T cells of peripheral blood in a fairly short period, where the biological properties of T cells are redirected and reprogrammed 5. T cells are rapidly expanded to derive memory and effector lymphocytes with high affinity in vitro. These T cells are then infused back into the patient to proliferate robustly and elicit potent anti-tumor activity (Figure 1A). These synthetic receptors recognize their corresponding specific antigens using a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) from the variable region in a major histocompatibility complex-independent manner. The majority of scFv possesses binding properties similar to antibodies. CAR-T cell therapy has shown dramatic clinical responses and high rates of complete remission in hematologic malignancies 6. However, therapeutic effects in solid tumors are not durable, partly owing to physical barriers, cancer heterogeneity, and TIME, which lead to recurrent CAR antigen loss and rapid CAR-T cell exhaustion 7. Recent strategies constantly focus on harnessing CAR-T cell therapy via engineering CARs, T cells, and interactions with other elements of TIME. Among these, remodeling TIME is one of the most attractive strategies for promoting the endogenous immune response to achieve a permanent CAR-T cell engagement 8.

Figure 1.

CAR-T cell therapy and tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment. A After isolating T cells from the peripheral blood of the patient, engineering the CARs genes into T cells to generate CAR-T cells. Then CAR-T cells are extensively expanded in vitro and administered to the patient. B TME is the central mediator of tumorigenesis and tumor-promoting function. The solid tumor microenvironment including the extracellular matrix, various immune cells, abnormal tumor vasculature, immunosuppressive molecules, and tumor metabolites prevents CAR-T cells from exerting high cytotoxicity. The tumor-associated stroma such as fibroblasts and mesenchymal cells formed physical barriers against the entry of T cells. The migration of T cells towards tumor lesions was increasingly challenged by dysregulation of adhesion molecules, mismatching of tumor-derived chemokines, and immune cell-expressed chemokine receptors. In addition, the metabolically abnormal TME impeded immune cell activity. C Cellular crosstalk between tumor cells and immune cells and bulk masses of immunosuppressive factors orchestrate a severely immunosuppressive tumor milieu to suppress the efficacy of CAR-T cells.

The immune characteristics of the tumor microenvironment (TME) have been categorized as one of the ten tumor characteristics 9, which play a decisive role in predicting the clinical outcomes of patients 10. Recognizing the essence of TIME has paramount implications for battling cancer cells. Here, we review evidence for each of the following perspectives. Firstly, how tumors orchestrate an immunosuppressive microenvironment promoting immune tolerance and evasion. Secondly, how to enhance the effectiveness of CAR-T cell therapy. Ultimately, we further elucidate the utilization of refreshing technologies to reverse the immunosuppressive microenvironment.

2. The Intricate Network Sustaining Immunosuppression in TIME

TME contributes to unfavorable immunotherapy efficacy by preventing CAR-T cells from exerting high cytotoxicity against tumor cells (Figure 1B). As proof: 1) The tumor-associated stroma such as fibroblasts, mesenchymal cells, and various extracellular matrices formed stumbling block against the entry of T cells 11; 2) The migration of T cells towards tumor lesions was increasingly overshadowed by the 'bad guys', such as dysregulation of adhesion molecules, aberrant tumor-related vasculature, and mismatching of chemokines and their receptors 11; 3) Cancer cells expressed ligands of suppressive immune checkpoints such as immune-dampening PD-1 ligand (PD-L1)/L2 12 and recruited more immunosuppressive cells 13, 14 to interfere with the effector T cells (Teffs) cytotoxic function. Additionally, the metabolically abnormal TME characterized by restricted nutrient availability, acidosis, and local hypoxia, impeded immune cell activity 15, 16. Nevertheless, these straitened circumstances have in turn spurred the design of CAR-T cells to better unleash the potential of immunotherapy. Generally, TME is the central mediator of tumorigenesis and tumor-promoting function, with immunological features possessing indispensable status. The complex immunosuppressive network in TME, that is tumor immunosuppression microenvironment, consists of miscellaneous immunosuppressive cell subsets, secretions, and signals that inhibit the recruitment, proliferation, differentiation, and execution of effector functions of immune cells. Here, we focus on the immunosuppressive landscape of TIME (Figure 1C).

2.1. Representative immunosuppressive cells in TIME

Tumor-associated immune cells possess crucial functions in tumorigenesis, which antagonize and/or promote tumors. Homogeneous immune cells could reshape themselves depending on different tumor ecosystems (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Miscellaneous immune cells inside tumors. The tumor-associated immune cells may possess tumor-antagonizing or tumor-promoting capacities. The homogeneous immune cells are able to change their state due to different tumor ecosystem or different stages of tumorigenesis. For instance, macrophages can shift from a hostile to a friendly status after immunotherapy. Elevating the amount of tumor-antagonizing immune cells opens a broad window for tumor treatment.

2.1.1 Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)

MDSCs are pathologically activated monocytes and neutrophils with vigorous immunosuppressive behavior and are implicated in the negative modulation of immune responses and poor clinical outcomes 17. An ocean of extracellular factors could induce MDSCs differentiation or expansion, encompassing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin (IL)-6, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), IL-13, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In contrast, IL-4 and all-trans-retinoic acid can inhibit this procedure 18, 19. MDSCs could be classified into granulocytic MDSCs (G-MDSCs) and monocytic MDSCs (M-MDSCs) according to the phenotypic and morphological characteristics or cell surface markers of MDSCs. M-MDSCs hindered CD8+ T cells via an inducible nitric oxide (iNOS)-mediated pathway 20-22, whereas G-MDSCs suppressed T-cell function through arginase and/or reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent mechanisms 23, 24.

Apart from promoting tumor development by forming pre-metastatic niches and angiogenesis 25, 26, MDSCs could also contribute to immunosuppression through the following mechanisms: 1) Inducting other immunosuppressive cells: MDSCs could not only secret IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) to directly hamper Teffs but also induce the de novo generation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) mediated by IL-10 and IFN-γ in vivo 21. CCR5 ligands CCL5, CCL4, and CCL3, produced by tumor-infiltrating M-MDSCs could recruit massive amounts of CCR5+ Tregs 27. They could also shift macrophages from M1 to an M2-like state with immunosuppressive features. It was demonstrated that MDSCs-produced IL-10 decreased macrophage IL-6 and TNF-α 28. 2) Blocking lymphocyte homing: splenic or blood-borne MDSCs were shown to execute far-reaching immune suppression through downregulating L-selectin lymph node homing receptors on naïve T and B cells. Furthermore, loss of L-selectin expression could disrupt T cell trafficking. T cells preconditioned by MDSCs have diminished responses to subsequent antigen exposure 29, 30. 3) Engendering reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: secreting ROS such as hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals, and superoxide anions was a well-known strategy to eradicate tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Enhanced ROS levels could increase the quantity and quality of tumor-infiltrating MDSCs by NF erythroid 2-related factor 2 and VEGF receptors, which might create a positive feedback loop 31, 32. MDSCs could also generate high levels of reactive nitrogen species (RNS) via activating the iNOS pathway 33. RNS could induce chemokine CCL2 nitration, hinder T-cell infiltration and engage T-cell apoptosis, leading to the trapping of specific T-cells in the tumor-associated stroma 34, 35. 4) Competing with immune cells for nutrient metabolites: high expression of arginase I and cationic amino acid transporter 2B by mature MDSCs could rapidly incorporate L-Arginine (L-Arg) and deplete extracellular L-Arg in vitro 36. L-Arg depletion blocked antigen-specific proliferation of OT-1 and OT-2 cells and the re-expression of CD3zeta in stimulated T cells 37. 5) Another mechanism by which MDSCs inhibit immune cells included the expression of ectoenzymes regulating adenosine metabolism from ATP 38 and negative immune checkpoint molecules 39.

2.1.2 Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs)

Proverbially, macrophages are essential components of innate immunity and leukocyte infiltration present in solid tumors, which regulate cancer-related inflammation and constitute vital regulators of tumor initiation and progression. Circulating monocytes could be recruited into the tumor stroma by multiple chemokines and cytokines such as CCL2, GM-CSF, and VEGF family members 40, 41. TME then prompted the differentiation of monocytes into TAMs 42. The immunological effects of TAMs are pro- and anti-tumor functions based on the state of macrophage activation. Collectively, M1 macrophages could respond to danger signals that produced type I pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-12, and TNF-α. Conversely, M2 macrophages expressed scavenger receptors and type II cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, promoting anti-inflammatory responses 43-45. M2 macrophages possessed pro-tumorigenic functions including promotion of tumor cell growth 46, drug resistance 47 and metastasis 48, neo-angiogenesis 9, 49, and immune suppression 50. The M1/M2 balance varied with cancer types. Both M1 and M2 macrophages have high levels of plasticity, with the ability to be converted into each other upon TIME or therapeutic interventions 51, 52. For example, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)-derived exosomes could reshape macrophages and result in M2-polarized TAMs via inducing pro-inflammatory factors and activating NF-κB signaling 53.

TAMs could regulate the immunological activity of T cells to foster tumor progression. Pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by TAMs could trigger the accumulation and expansion of CD4+ Th17 cells to foster angiogenesis and overexpressing CTLA-4, programmed death-1 (PD-1), and glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor (GITR), thereby promoting tumor development 54. TAMs could also attract Tregs into tumor tissues by producing various chemokines, such as CCL17, CCL18, and CCL22 55, 56. Additionally, they could directly handicap the proliferation of CD8+ T cells through the metabolism of L-arginine and the production of iNOS and ROS 34, 57.

TGF-β in TME upregulated Tim-3 expression on TAMs, which promoted tumorigenesis and tolerance via NF-κB signaling and downstream IL-6 production 58. It has been also validated that TAMs could produce IL-6 and signal via STAT3 to facilitate the expansion of carcinoma stem cells sustaining carcinogenesis 59. Likewise, TAMs were demonstrated as a nexus with the prognosis of numerous tumors, such as HCC 60 and breast cancer 61.

2.1.3 Tregs and regulatory B cells (Bregs)

Commonly referred to as Tregs are CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells, which could chemoattract TME through chemokine gradients such as CCR8-CCL1, CCR4-CCL17/22. Tregs negatively moderate immune responses to maintain autoimmune tolerance and homeostasis. However, excessive suppression of immune responses in the TME promoted tumor progression 62. Abundant infiltration of Tregs positively correlated with depressed survival in various tumor types, such as pancreatic and melanoma 63. Intratumoral Tregs were highly immunosuppressive and consumed IL-2 through the high expression of CD25 (IL-2 receptor subunit-α), thereby limiting the activation and proliferation of Teffs dependent on IL-2. Tregs also inhibited and/or killed Teffs by releasing suppressive molecules and producing cytotoxic substances 64, 65. Upregulating immune checkpoint molecules including the lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3), CTLA-4, PD-1, and inducible co-stimulator (ICOS), was an alternative strategy for Tregs to suppress Teffs 64.

B cells in TME play a double-edged sword effect either by promoting tumor immunity or enhancing tumorigenesis 66. It has been shown that any B cell has the potential to differentiate into Bregs. Bregs prohibited the expansion of T cells and other immune-system pro-inflammatory lymphocytes to exert suppression. Despite partial consensus on the immunosuppressive effector functions of Bregs, the field has not yet reached a unified view on their phenotype 67. Immunohistochemical analyzes showed that the frequency of CD19+IL-10+ Bregs in tongue squamous cell carcinoma was significantly higher than adjacent normal tissue. Increased Bregs could convert CD4+CD25- T cells into CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs in cytological experiments and are associated with cancer progression and worse survival 68. Correspondingly, B cells enriched in the ascites from ovarian cancer patients were inversely correlated with the frequencies of IFN-g+CD8+ T cells, but positively correlated with Tregs 69. Another study showed that bone marrow-derived Bregs could abrogate NK cell antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity against multiple myeloma cells 70.

2.1.4 Others

Tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) are another type of immune cell that infiltrates various tumors. TANs could be recruited to TME by IL-8 via CXCR1/CXCR2 receptors and abolish the ability of CD8+ T cells through TNF-α production-mediated NO 71, 72. Similar to TAMs, TANs are partitioned into anti-tumoral (N1) and pro-tumoral (N2) phenotypes. Type I IFNs could alter neutrophils into N1 phenotypes, which transform the pro-tumor properties of low neutrophil extracellular traps and TNF-α expression into anti-tumor milieus. The constantly changing TIME drove the polarization of TANs. Altered TANs were connected with different prognoses in cancers and modulation of TANs phenotypes may represent a potent therapeutic option 73, 74. More significantly, TANs infiltration or neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio strongly correlates with cancer development, which may have utility as a predictive biomarker to monitor cancer patients receiving immunotherapy (e.g., melanoma, metastatic renal cell cancer) 75, 76.

Mast cells (MCs) are well known to participate in allergy and inflammation. The ability of MCs in TME has been hypothesized to be either pro- or anti-tumor 77. The number of infiltrating MCs correlated positively with poor cancer prognosis 78, 79. Recently, Leveque et al. have demonstrated that tumor-associated mast cells (TAMCs), a heterogeneous population, harbor a distinct phenotype compared to MCs present in the non-lesional homologue of lung cancer 80. It is further noted that the TAMCs subset expressing alpha E integrin, namely CD103+ TAMCs, appeared more actively to interact with CD4+ T cells and located closer to tumor cells than their CD103- counterparts. Recruitment of TAMCs was mediated by chemotactic agents released by TME, such as VEGF, CXC chemokine ligand (CXCL)12, PGE2, and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) 80, 81. Activated TAMCs could express CCL5 and IL-33 to further recruit MCs into tumor sites and activate themselves in an autocrine manner. TAMCs could drive angiogenesis, immunosuppression, as well as tumor invasion and metastasis through secreting substantial proteolytic enzymes and growth factors 79, 81. Nevertheless, some studies have shown that a high frequency of TAMCs correlated with better progression-free survival and overall survival 79, 80. Together, the immunosuppression of TAMCs in TME remains relatively vague and controversial.

Dendritic cells (DCs) acting as specialized antigen-presentation cells have long been recognized as a critical factor in T-cell-mediated anti-tumor reactions. DCs uptake and cross-present tumor antigens to naïve T cells accompanied by priming and activating CTLs with the ability to eradicate tumor cells 82. Intriguingly, although tumor-associated dendritic cells (TADCs) could prevent prolongedly steady tumor expansion at early stages, the enduring activity of T cells was abrogated by microenvironmental immunosuppressive TADCs at late stages, becoming less responsive 83, 84. The tumor-antagonizing role of DCs within TME faced inauspicious roadblocks85. The chemotactic gradient of TME caused a paucity of DCs recruitment and a constellation of immunosuppressive factors accelerated tolerance and DCs dysfunction 86, 87. Numerous oncogenic signaling axes could restrict the ability of DCs. Ruiz et al. reported that HCC impaired DCs recruitment due to the absence of a tumor-derived chemokine CCL5 via tumor-intrinsic Wnt/β-catenin signaling 88. STAT3-mediated signaling also handicapped the differentiation and maturation of DCs by producing IL-10, TGF-β, and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) 89. Furthermore, TADCs could express immune-inhibitory checkpoints, such as PD-L1 and TIM-3, to impede the activation of CTLs 88, 90. TADCs could also spark tumor plasticity, growth, and metastasis by promoting genomic instability, neovascularization, and immunometabolism 91, 92.

2.2 The intricate immune inhibitory factors network in TIME

Immune cells, endothelial, stromal, and tumor cells within the TME secreted bulk masses of immunosuppressive factors including chemokines, cytokines, and inhibitory molecules to assist and/or restrain each other, which orchestrates a severely immunosuppressive tumor milieu. These factors bind to corresponding receptors via paracrine, autocrine or endocrine means to modulate tumor growth/invasion/metastasis, and immune responses, thereby reshaping TME and mediating intercellular crosstalk. Some of their specific features have been mentioned above. Herein, we dissect the representative participants in the current data (Table 1).

Table 1.

Representative immune inhibitory factors mediated pro-/anti-tumor function

| Molecules and signaling pathways | Category | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-7, IL-15, IL-21 | Pro-inflammatory cytokine |

· The common γ chain cytokine family · Promote the generation of the stem cell-like memory T cell phenotype · Boost the tumor-killing activity of NK and CTL cells |

93, 94 |

| IL-18 | Pro-inflammatory cytokine |

· A potent inducer of IFN-γ · Contribute to T and NK cell activation and Th-1 cell polarization · Participate in promoting tumor angiogenesis, metastasis, and immune escape |

95, 96 |

| IL-12 | Pro-inflammatory cytokine (anti-tumor immunity modulator) |

· Activate NK cells and T lymphocytes and induce Th-1 type responses · Increase IFN-γ secretion and cytotoxicity |

97 |

| IL-4, IL-13 | Anti-inflammatory/inhibitory cytokine |

· Suppress type 1 immunity and cytotoxic T cell development · Induce expansion of monocytes or macrophages within the tumor stroma and antagonize the tumor-suppressing activity of type 1‑activated macrophages |

19, 43 |

| IL-6/STAT3 | Pro-inflammatory/carcinogenesis signaling |

· Induce MDSCs differentiation or expansion, then result in immunosuppression · Favor the expansion of carcinoma stem cells sustaining carcinogenesis · Up-regulate IDO production; down-regulate IFN-γ; induce T cells apoptosis and dysfunction |

18, 19, 59 |

| PD-1/PD-L1 | Immune checkpoint molecules | · Expressed on activated T lymphocytes and deliver immunosuppressive signals, drive T cells into a state of exhaustion, tolerance, or dysfunction | 64 |

| LAG3 | Immune checkpoint molecule |

· An exhaustion marker and inhibitory receptor · Impair CD4+ and CD8+ TILs functions |

64, 98 |

| CTLA-4 | Immune checkpoint molecule |

· Exert an inhibitory signal to T cells, and then make T cells with an inactive state · Enhance Tregs activity and IDO and IL-10 productions in DCs |

64, 99 |

| Tim3/Galectin-9 signaling pathway | Immune checkpoint signaling | · Inhibit the activation and function of CTLs and promote immune cells apoptosis | 90, 98 |

| CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11/CXCR3 axis | Th1-type chemokines |

· Produced by tumors and immune cells, augment Teff and NK cell trafficking into tumors · Promote CTLs and NK cells differentiation, and regulate differentiation of naive T cells to T helper 1 (Th1) cells · Possess an opposite role in either pro- or anti-tumor responses |

100, 101 |

| CXCL12/CXCR4 | C-X-C subfamily chemokine and its receptor |

· CXCL12 contributes to the migration of plasmacytoid DCs into TME, tumor proliferation, and metastasis · CXCR4 can only combine with CXCL12 and prevents tumor metastasis and development |

102 |

| CCL2, CCL3, CCL5 | C-C subfamily chemokines |

· Recruit macrophages, neutrophils, and Tregs into TME, promote the polarization of M2-macrophages ·Assist the accumulation of immunosuppressive MDSCs and tumor metastasis |

27, 40, 41 |

| CXCR1 | C-X-C chemokine receptor family |

· Increase neutrophil recruitment · Bolster proliferation of tumor-initiating cells, and neoplastic mass formation |

72 |

| CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling | Immunosuppressive signaling axis |

· Stimulate tumor proliferation and self-renewal, correlate with pro-angiogenic and cancer-promoting genes of the tumor, involve in tumor metastasis · Amplify its production and remarkably induce both tumor-promoting and immunosuppressive factors |

103 |

| IDO | Immunosuppressive modulator |

· Suppress T cell cytotoxicity and IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α production · Enhance Treg-mediated immunosuppression, thus creating a tolerogenic milieu in tumor sites |

50, 104 |

| VEGF, PDGF | Growth factors |

· Promote angiogenesis and immune evasion · Mediate recruitment of immune inhibitory cells and other pro-inflammatory signals in TME |

32, 81 |

| Hypoxia /HIF1α | Tumor metabolic environmental factors/ “oxygen sensor” |

· Increase the MDSCs infiltration and suppressive function · Control the PD-L1 expression on cancer cells and PD-1 expression on T cells, accordingly dampening T cell survival and effector functions |

16, 105 |

| Hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals, superoxide anions, and nitric oxide | Reactive species (ROS, RNS) |

· Lead to immune cell apoptosis and deficient effector differentiation, · Inhibit the proliferation and function of CD8+ T cells · Contribute to MDSC recruitment into the TME, result in differentiation and expansion of MDSCs |

16, 32-34 |

| Extracellular adenosine/ Adenosine signaling | immunosuppressive molecule/ signaling |

· Impair the activation, proliferation, survival and cytokine production of T cells and other immune cells · Activation of adenosine receptors A2A and A2B on tumor-infiltrating immune cells suppress the anti-tumor activities of these cells · Favor tumor progression and escape from anti-tumor immunity |

106-109 |

2.3 Tumor antigen heterogeneity

In addition to the exogenous factors mentioned above (e.g., immunosuppressive cells and factors of the TIME), the endogenous factors (e.g., tumor antigen heterogeneity) could further exacerbate the immunosuppressive landscape of TIME. Identifying tumor-specific antigens as targets is a challenge for CAR-T cell therapy to win the war against solid tumors. The optimal target surface antigen should possess excellent coverage, high expression on solid tumors, and not affect normal cells to avoid on-target and off-tumor cross-reactions 110. However, antigenic heterogeneity is a specific feature of solid tumors. Tumor cells could conceal themselves by removing or constantly modifying their representative antigens, which are antigen loss and antigen-low escape, confusing the targeted attacks of CAR-T cells 111, 112. It has been demonstrated that antigen loss occurred via two distinct mechanisms: antigen escape or lineage switch 113. Antigen escape, or isoform switch, occurs when cancer cells present different patterns of targeted antigens without being detected by CAR-T cells. This mechanism is probably connected to gene mutations at the antigen locus due to immune pressure by CAR-T cells 114. Lineage switch is linked to substantial changes in chromatin accessibility and rewiring of transcriptional programs in tumor cells, including alternative splicing 115. Antigen-low escape indicated that CAR-T cells targeting specific antigens were unable to effectively eliminate specific antigens-low cells 116. There is an overlap between antigen escape and low antigen density escape.

3. Up-to-date Strategies for CAR-T Cell Therapy to Address the Hostile Immune Microenvironment

With the increasing understanding of TIME, more strategies concentrate on 're-editing' TIME to better arouse tumor-antagonizing immunity, which offers a novel tactic for CAR-T cell therapy.

3.1 Targeting immune suppressive cells

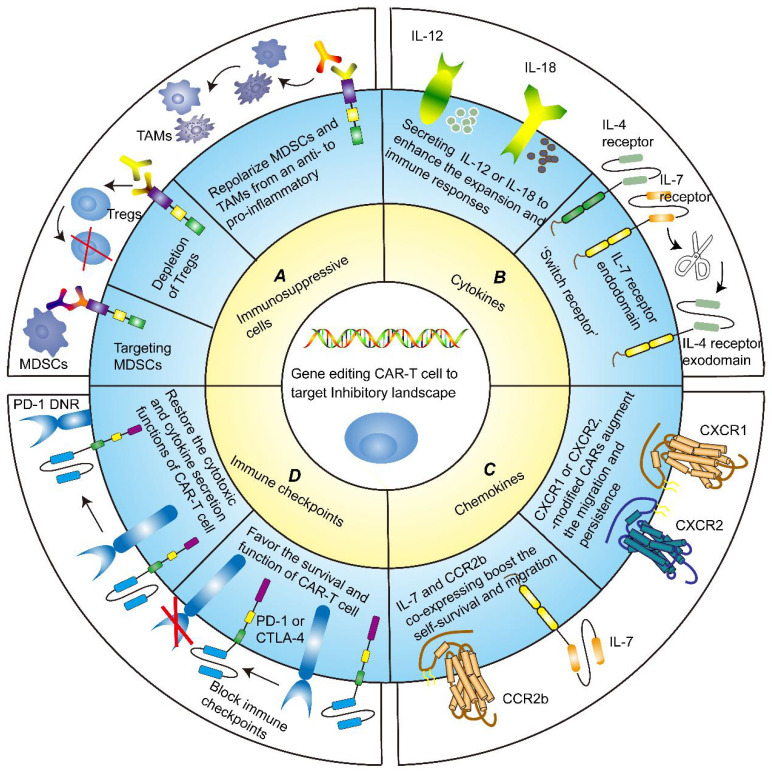

Several approaches of targeting immunosuppressive cells to advance the tumor-killing ability of CAR-T cells have been applied in basic studies (Figure 3A). It has been reported that MDSCs inhibited the cytotoxicity of different generations of disialoganglioside (GD2)-CAR-T cell. The frequency of circulating MDSCs was inversely correlated with the levels of GD2-CAR-T cell in phase I/II clinical trial, further underlining the importance of targeting immunosuppressive cells 117. Frustratingly, due to the high similarity of MDSCs to normal myeloid cells, it is extremely challenging to specifically target and eliminate MDSCs from TME without detrimental off-target signaling. Nevertheless, flow cytometry analysis confirmed that TRAIL receptor 2 (TR2) was highly expressed on the surface of MDSCs. By co-expressing a costimulatory TR2.41BB receptor to target both tumor cells and MDSCs, CAR-T cells exhibited enhanced persistence and proliferation 118.

Figure 3.

Gene modification strategies for CAR-T cells. A Targeting immune suppressive cells. CAR-T cells exhibit enhanced persistence and proliferation by targeting MDSCs or depleting Tregs. Likewise, repolarizing MDSCs and TAMs from an immunosuppressive to pro-inflammatory phenotype could boost the anti-tumor functions of CAR-T cells. B Targeting cytokines milieu. CAR-redirected T-cell engineered to release inducible IL-12 or IL-18 could eliminate the antigen-loss cancer cells, recruit immune cells and reinforce their functions, and sustain pro-inflammatory responses. An alternative strategy to counteract immunosuppressive TME is to generate an inverted cytokine receptor in which the IL-4 receptor exodomain was fused to the IL-7 receptor endodomain, which removes the side effects of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-4. C Targeting chemokines milieu. CXCR1 or CXCR2-modified CARs remarkably favored T-cell migration and persistence in TME, leading to the induction of complete tumor regression and durable immunologic memory. IL-7 and CCR2b co-expressing CAR-T cells also boosted the self-survival and migration, increased IFN-γ, Gzms-B, and IL-2 expression, and inhibited tumor growth. D Targeting immune checkpoints. Blocking immune checkpoints sponsored CAR-T cell survival and function of killing tumor cells. Dominant-negative receptors (DNRs) could interfere with the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, thereby restoring the cytotoxic and cytokine secretion functions of CAR-T cells.

The combination of CAR-T therapy with immunomodulatory agents was proposed for obtaining satisfactory therapeutic results 119, 120. Sun and colleagues performed co-administration of Olaparib, a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor killing cancer cells by participating in DNA defect repair pathways, in combination with CAR-T cells 121. The co-administration enhanced anti-tumor responses by impeding MDSCs migration through the SDF1a/CXCR4 axis in immunocompetent mouse models of breast cancer. The combination of CAR-T cell therapy with the folate-targeted Toll-like receptor 7 agonists repolarized MDSCs and TAMs from a hostile to the amicable state. Moreover, it also concurrently enhanced the accumulation and activation of both CAR-T cells and endogenous T cells 122.

Engineering CARs to target TAMs is also a pervasive experimental direction. TAMs that expressed appreciable levels of folate receptor beta (FRβ) possessed an immunosuppressive M2-like phenotype, which indicated that targeting FRβ could limit the outgrowth of solid tumors 123, 124. Subsequently, Rodriguez-Garcia and colleagues demonstrated that CAR-T cell-mediated selective elimination of FRβ+ TAMs could augment pro-inflammatory monocyte enrichment and endogenous tumor-specific CD8+ T cell influx, delayed cancer progression, and prolonged survival in syngeneic cancer mouse models 124. By employing a similar strategy, other researchers designed third-generation CAR-natural killer (NK) and -T cells. They specifically targeted human CSF 1 receptor (CSF1R) on TAMs and had favorable cytotoxicity to remove the inhibitory effect of M2 TAMs 125. However, Wu and colleagues reported that the effects of GPC3-CAR T cells could be further improved, which can at least partially be ascribed to IL12 secretion of TAMs 119. This implied that TAMs are highly plastic and heterogeneous. And to some extent, early TIME might exhibit anti-tumor effects, while late TIME was more biased toward tumor promotion 83, 84.

Likewise, depletion of other immunosuppressive cells is an attractive way. Using an anti-CD25 antibody with augmented binding to activating Fc gamma receptor (FcγR, an inhibitory receptor that blocks intra-tumoral Tregs depletion), CD25+ Tregs were depleted. This reinforced cancer-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and improved the eradication of established tumors 126. The third-(CD28-4-1BBz) generation CAR-T cell that the PYAP Lck binding-motif of CD28 domain incorporated two amino acid substitutions to eliminate IL-2-associated Tregs has been invented. CAR-T cell remarkably retarded cancer growth without a need for lymphodepletion 127. Alternatively, pretreatment of immune cells to lessen the inhibitory effect may serve as bridging salvage chemotherapy for further CAR-T cell therapy 128. For instance, daratumumab had successfully treated a case-patient with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma-transformed plasma-cell leukemia. The immune cell subset analysis of patients revealed dramatical down-regulation of CD38+ NK cells, Tregs, and Bregs 129. In mice tumor models, CAR-T cells armed with neutrophil-activating protein (NAP, a pluripotent pro-inflammatory protein) could slow tumor occurrence and development, and bolster survival rates of innate immune cells, regardless of host haplotype, target antigen, and tumor type 130. Taken together, reprogramming cancer-associated immunosuppressive cells to a more favorable niche could provide new dawn for CAR-T cell therapy.

3.2 Targeting the cytokine and/or chemokine milieu

3.2.1 Cytokines

Induced local dissemination of stimulatory factors could counteract the immunosuppressive dilemma to reinforce CAR-T cell potency (Figure 3B). Currently, recombinant cytokine drugs such as IL-2 and IFN-α, have been approved for anti-tumor treatment. This facilitates the generation of “armored” CAR-T cells engineered to secret pro-inflammatory cytokines. To illustrate, CAR-redirected T-cells tailored to release inducible IL-12 could eliminate the antigen-loss cancer cells, recruit macrophages and reinforce the function, and sustain pro-inflammatory responses 131. Combining CAR-T cells with recombinant human IL-12 also fueled anti-cancer activity 132. IL-18-expressing CAR-T cells have also been shown to possess excellent multiplication power and induce deeper B cell aplasia in mice with B16F10 melanoma 133. Interestingly, Kunert and colleagues verified that IL-12-secreting T-cell receptor-modified T (TCR-T) cells caused severe edema-like toxicity, augmented blood levels of IFNγ and TNFα, and decreased numbers of peripheral TCR-T cells, while IL-18-secreting TCR-T cells reduced cancer burden and prolonged survival without side effects 134.

More recently, a preclinical study emphasized that CAR-T cells via autocrine IL-23 signaling had the superior anti-tumor capacity and attenuated side effects, with decreased PD-1 expression and increased granzyme B in comparison to those expressing IL-18 135. Gene-engineering expressing IL-15 136, IL-7 and CCL19 137, and IL-4/21 138 has also been explored to boost anti-tumor activities through promoting proliferation, survival, activation, and stem cell memory subset of CAR-T cells and endogenous T cells. The above CAR-T cells equipped with cytokines could reverse immunosuppressive TME not only by extending their expansion and lifespan, but also by activating immune effector cells.

Another approach to addressing the efficacy conundrum is to modify CAR-T cells by rewiring inhibitory inputs to stimulatory outputs or being refractory to inhibitory cytokines present in TME. Engineering of TGF-β CAR-T cells demonstrated that CARs could express a dominant-negative TGF-βRII (dnTGF-βRII), thereby blocking TGF-β signaling in T cells. DnTGF-βRII increased CAR-T cell proliferation and long-term in vivo persistence, bolstered cytokine secretion, fought against exhaustion, and induced tumor eradication 139, 140. In contrast, CAR-T cells engineered to respond to TGF-β allowed themselves to convert immunosuppressive cytokine into triggers of anti-tumor activity 139, 141. TGF-β-responsive CAR-T cells could proliferate and produce T helper type 1 (Th1)-associated cytokines in the presence of soluble TGF-β, protect nearby cells from the immunosuppressive effects of TGF-β, and significantly improve the anti-tumor efficacy of neighboring CTLs 139, 141. Notably, TGF-β was associated with the lack of immune response exhibiting low levels of T cell penetration into the tumor center 142. Thus, targeting this axis could be the most susceptible solution to destroy solid tumors.

'Switch receptor' could also achieve by rewiring negative signals. Mohammed and colleagues 143 generated an inverted cytokine receptor in which the IL-4 receptor exodomain was fused to the IL-7 receptor endodomain to remove the side effects of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-4. This result manifested that engineered CAR-T cells could transmit inhibitory signals into therapeutic stimulants through an IL-7-induced downstream pathway and possessed strengthened proliferation and superior anti-tumor ability 143, 144. Pleasingly, combined single-cell transcriptome analysis and CRISPR-Cas9 knockin nominated a novel TGF-βR2:4-1BB switch receptor to improve CAR-T cell fitness and solid tumor clearance 145.

3.2.2 Chemokines

Given the pivotal role of chemokines and their receptors in recruiting immune cells and trafficking CAR-T cells into tumors, numerous studies have endeavored to integrate chemokines and CAR-T cells to battle tumors in recent years (Figure 3C) 146. Most investigations focused on CXCR2-modified CAR-T cells. Preclinical models demonstrated that IL-8 receptor, CXCR1 or CXCR2, -modified CARs remarkably favored T cell migration and persistence in TME, thereby inducing complete cancer regression and immunologic memory in aggressive tumors such as ovarian, glioblastoma, and pancreatic cancer 147. CXCR2-modified CAR-T cells could also accelerate trafficking in vivo and tumor-specific accumulation 148. Whilding and colleagues came to a similar conclusion that CXCR2-expressing CAR-T cells efficiently migrated towards tumor-conditioned media containing IL-8 and had a more favorable toxicity profile of eliciting anti-cancer responses against αvβ6-expressing ovarian or pancreatic tumor xenografts 149.

Targeting other chemokines is under active experimentation, some of which have achieved satisfactory therapeutic effects in solid tumors. Some researchers constructed a lentivirus-based CAR gene transfer system targeting CCR4, a chemokine receptor over-expressed in T-cell malignancies and Tregs profiles 150. CCR4-expressing directed CAR-T cells displayed antigen-dependent potent cytotoxicity against T-cell malignancies in mouse xenograft models. Wang and colleagues designed co-expressing mesothelin (Msln) and chemokine receptors CCR2b or CCR4 CAR-T cells 151. The Msln-CCR2b-CAR and/or Msln-CCR4-CAR T cells possessed fortified migration and infiltration, specifically exerted cytotoxicity, and expressed high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Compared with traditional CAR-T cells, IL-7 and CCR2b co-expressing CAR-T cells boosted self-survival and migration, enhanced IFN-γ, Gzms-B, and IL-2 expression, and obstructed tumor growth 152. These strategies all pave the way for the clinical application of CAR-T cells.

Undoubtedly, CAR-T cells engineered to acquire responsiveness to cytokines, chemokines, and their receptors exhibit stronger tumor-antagonizing and trafficking functions than the classical second-generation. CAR-T cells against other soluble inhibitors such as PGE2 153 and VEGF receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) 154 could also conduce to solid tumor regression, shedding light on the potential novel solid tumors treatment regimens. Even so, individuals treated with the aforementioned CAR-T cells might develop off-target effects and various systemic toxicities such as cytokine release syndrome 155, and neurotoxicity 156, even leading to death 157. It has been hypothesized that gaining insight into cytokine and chemokine expression profiles across different tumor types and different individuals and exploring how to traffic CAR-T cells into TME with personalized medicine could lessen the severity of toxicities. No matter what, the efficacy in patients is required to be further tested in clinical trials.

3.3 Targeting immune checkpoints

Immune checkpoint receptors and ligands, such as PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4, could preclude CAR-T cell cytotoxicity and induce anergy in TME 158. Checkpoint blockades are a successful therapeutic intervention to date for solid tumors, which have been used concurrently with CAR-T cell therapy in ongoing clinical trials and obtained potent synergistic activities (Figure 3D) 159. Combination therapy targeting PD-1 has been demonstrated to promote the survival of CAR-T cell and kill PD-L1+ cancer cells via activation-induced cell death 160. A multitude of studies had also shown that PD-1/PD-L1 pathway interference, including anti-PD-1 antibodies, cell-intrinsic PD-1 shRNA blockades, or PD-1 dominant-negative receptors (DNRs) restored the cytotoxic and cytokine secretion functions of CAR-T cell through tailored to secrete immune-checkpoint blockades or combination therapy 159, 161, 162. Moreover, the combination therapy of GD2-CAR-T cells with checkpoint blockades was well tolerable and effective in patients with relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma 163. Likewise, clinically significant antitumor responses following PD-1 blockade combined with CAR-T cells have been reported in a patient with refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and progressive lymphoma 164.

Gene-editing technologies that knock out immune checkpoints could also be applied to abrogate the expression of T cell negative regulators. PD-1 knockout through TALEN technology augmented the persistence and tumor clearance capability of intratumoral T cells and established durable anti-tumor memory 165. In addition, CRISPR-Cas9-mediated PD-1 disruption enhanced CAR-T cell cytokine production and cytotoxicity towards PD-L1+ cancer cells without attenuating the proliferation 166. Using the CRISPR/Cas9 system to disrupt universal CAR-T cells with genes lacking TCR and PD-1, Ren and colleagues demonstrated potent anti-tumor effector function in vitro and animal models 167. Knockout of CD3-signaling regulator diacylglycerol kinase for resistance to PGE2 could also augment CAR-T cell abilities 168. Nevertheless, the safety and feasibility of genome-editing technology to reverse checkpoint-induced inhibitory signaling in clinical patients are still in non-stop exploration.

Similar to PD-1, LAG-3 and T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (Tim-3) known as T cell exhaustion markers functioned as coinhibitory receptors to throttle T cell proliferation and cytokine production 98, 169. Shapiro et al. found that soluble LAG3 promoted tumor cell activation and anti-apoptotic effects 170. Afterward, blocking LAG-3 ramped up T cell activation, which rendered LAG-3 evolve into a popular target. Equivalently, targeting Tim-3 is also a prospective strategy 169. Indeed, checkpoint blockades have revolutionized the field of immuno-oncology, which could be operative against malignancies that fail CAR-T cell therapy and refuel CAR 164. However, one hypothesis suggests that CAR-T cell therapy for most tumor cells with unexpressed targeted antigen is unlikely to be successful unless combination strategies that enhance bystander effects are applied, and neither anti-PD-1/CTLA-4 antibodies stir bystander effects 171. Combination therapy could also increase on-target off-cancer toxicity. Inspiringly, Rafiq et al. modified CAR-T cells to secrete PD-1-blocking scFv 172. ScFv-secreting CAR-T cells were equally effective or superior to combination therapy with CAR-T cells and a checkpoint inhibitor. Notably, this strategy could prevent the toxicities connected with systemic checkpoint inhibition.

3.4 Targeting tumor antigen heterogeneity

In the previous section on targeting immunosuppressive cells and/or factors, we covered part of targeting tumor antigen heterogeneity. Admittedly, as CAR-T cells targeting solid tumors become increasingly effective due to tumor antigen heterogeneity, clinical outcomes will be constrained 112. Single-target CAR-T cells typically lead to positive selection of antigen-mismatched tumor cells, thereby dampening durable efficacy. Conversely, bispecific CAR-T cells can launch a dual attack on evading cancer cells to avoid ineffective treatment due to heterogeneous target antigen expression and overgrowth of cancers lost a single targeted antigen 173. CAR monomers of bispecific CAR-T cells comprised two patterns. One was two distinct scFvs 'hand-in-hand' on one cell, whereas the other was two independent CAR monomers with distinct scFvs on a single cell. Recent studies showed that bispecific CAR-T cells could enhance tumor-suppression capacity through dual antigen recognition and internal activation to effectively eradicate tumor cells 174, 175.

Another way to achieve multiple targets is to create bispecific T cell engagers (BiTEs) linking CD3 scFvs and tumor-associated antigens. BiTEs are bispecific antibodies that redirect T cells to target antigen-expressing tumors. Compared with single-target CAR-T cells, BiTE CAR-T cells demonstrated prominent activation, cytokine production, and cytotoxicity in response to target-positive tumors 176, 177. Choi et al. developed a bicistronic construct to drive CAR expression specific for EGFRvIII and EGFR. Unlike EGFR-specific CAR-T cells, BiTE-CAR efficiently redirected CAR-T cells, recruited untransduced bystander T cells against heterogeneous tumors, and was not toxic to human skin grafts in vivo 177. In conclusion, BiTEs secreted by T cells exhibit robust anti-tumor function, substantial sensitivity, and specificity, establishing a bridge between CAR-T cells and solid tumors 178.

4. Future Directions for CAR-T Cell to Optimize TIME

Despite countless researchers working on the clinical translation of CAR-T cells to overcome the unfriendly TIME, there are numerous hard nuts to crack without any clue. Table 2 lists the ongoing clinical trials of CAR-T cell therapy in solid tumors and no results for all studies in clinical applications. Solid tumors excel at selectively fascinating or avoiding leukocyte subsets and inducing dysfunctional or immunosuppressive phenotypes on resident leukocytes to promote immunosuppression and/or tumor progression 8. The road for CAR-T cells to conquer the chilly TIME of solid tumors is extremely tortuous. Several reports indicated that aggressive cancer growth was primarily driven by mobilization of immunosuppressive leukocytes in TME rather than loss of tumor immunogenicity following a relatively long incubation period 83, 84. Due to the spatial and temporal variability of TIME, both immune composition and tumor-specific targets undergo dynamic variation in genotype, phenotype and transcriptome, further illustrating the undisputed primacy of targeting TIME 179.

Table 2.

Representative CAR-T cell clinical trials for solid tumors.

| NCT Number | Phase | Status | Tumor types | Interventions | Study result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT03851146 | Ⅰ | Completed | Advanced Cancer | LeY CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT03706326 | Ⅰ | Ⅱ | Unknown status | Advanced Esophageal Cancer | Anti-MUC1 CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT03874897 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Advanced Solid Tumor | CAR-CLDN18.2 T-Cells | - |

| NCT02862028 | Ⅰ | Ⅱ | Unknown status | Advanced Solid Tumor | HerinCAR-PD1 cells | - |

| NCT05287165 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Digestive System Neoplasms | Pancreatic Cancer | Colorectal Cancer | IM96 CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT05275062 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Gastric Cancer | Esophagogastric Cancer | Pancreatic Cancer | IM92 CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT03356795 | Ⅰ | Ⅱ | Unknown status | Cervical Cancer | Cervical cancer-specific CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT05089266 | Ⅰ | Not yet recruiting | Colorectal Cancer | αPD1-MSLN-CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT05415475 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Colorectal Cancer | Esophageal Cancer | Stomach Cancer | Pancreatic Cancer | CEA CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT04503980 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Colorectal Cancer | Ovarian Cancer | αPD1-MSLN-CAR T cells | - |

| NCT05341492 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Lung Cancer | Breast Cancer | EGFR/B7H3 CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT04581473 | Ⅰ | Ⅱ | Recruiting | Gastric Adenocarcinoma | Pancreatic Cancer | Gastroesophageal Adenocarcinoma | CT041 autologous CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT05131763 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Glioblastoma | Medulloblastoma | Colon Cancer | NKG2D-based CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT02932956 | Ⅰ | Active, not recruiting | Liver Cancer | Glypican 3-specific CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT04489862 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Non-small-cell Lung Cancer | Mesothelioma | αPD1-MSLN-CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT04864821 | Ⅰ | Not yet recruiting | Osteosarcoma | Neuroblastoma | Gastric Cancer | Lung Cancer | Targeting CD276 CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT04981691 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Refractory Malignant Solid Neoplasm | anti-MESO CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT03356782 | Ⅰ | Ⅱ | Recruiting | Sarcoma | Osteoid Sarcoma | Ewing Sarcoma | Sarcoma-specific CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT02107963 | Ⅰ | Completed | Sarcoma | Osteosarcoma | Neuroblastoma | Melanoma | Anti-GD2-CAR engineered T cells | - |

| NCT03545815 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Solid Tumor | anti-mesothelin CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT05437315 | Ⅰ | Ⅱ | Recruiting | Solid Tumor | bi-4SCAR GD2/PSMA T cells | - |

| NCT05382377 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Solid Tumor | NKG2D CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT05373147 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Solid Tumor | αPD1-MSLN-CAR-T cells | - |

| NCT04976218 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Solid Tumor | EGFR Overexpression | TGFβR-KO CAR-EGFR T Cells | - |

| NCT04467853 | Ⅰ | Recruiting | Solid Tumors | LCAR-C18S cells | - |

-: No Results Available

Recently, the rapid advancement of nanomedicine has provided inimitable insights into the security and durability of CAR-T cell therapy. Nanoparticles that achieve targeted delivery and prolong the retention time of carried drugs could better remodel the tumor immunosuppressive environment than traditional drugs 180. Luo and colleagues developed IL-12 nanostimulant-engineered CAR-T cell (INS-CAR-T) biohybrids that not only evoked robust anti-tumor efficacy and biosafety via immune feedback but allowed for controllable drug effects 181. INS-CAR T biohybrids enjoyed various characteristics, including elevated expression of anti-tumor factors, efficient recruitment, deep penetration, and selective proliferation. Several researchers put forward an alternative strategy that CAR-T cells engineered to produce extracellular vesicles containing RN7SL1 by delivering the pattern recognition receptor agonists could effectively stimulate anti-tumor immunity 182. These CAR-T cells with delivery systems or functional nanochaperones could be a powerful tool with the possibility to shift the immunologic landscape and outlook for solid tumors (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Cutting-edge technologies to augment the security and durability of CAR-T cells. There are increasingly revolutionary technologies and researches applied in CAR-T cell therapy, which provide a bright guide to reshaping TIME. A Nanoparticles could achieve targeted delivery and prolong the retention time of carried drugs. Nanostimulant-engineered CAR-T cells not only could evoke robust anti-tumor efficacy and biosafety via immunofeedback but allow for controllable drug effects on CAR-T cells. I CAR-T cells penetrate the tumor location and elicit the first killing. II Secreting pro-inflammatory factors to trigger immune cells and endogenous T cells at the right moment could initiate secondary killing and form a positive anti-tumor cycle from CAR-T cells to T cells. III The cancer cells with CAR antigen loss could be recognized and killed by CAR-T cells delivering peptide antigen to cancer cells. B Radioactive material is extensively utilized and may have distinct immunomodulatory effects both locally and systemically. The combination of radiotherapy and CAR-T cell therapy could maximize the effect of immunotherapy. The separated T cells are directly labeled and genetically modified. The radiolabeled CAR-T cells are infused into tumor-bearing mice and monitored by PET/SPECT imaging. If the tumor worsens in tumor-bearing mice, then redesign and relabel the CAR-T cells with radioactive material.

Radioactive material is extensively utilized and may have distinct immunomodulatory effects locally and systemically. In addition to boosting local expression of multiple cytokines and promoting vascular normalization, radiotherapy could activate endogenous target antigen-specific immunity to yield complementary benefits, thereby maximizing the effect of CAR-T cells 183-185. Radionuclide-based molecular imaging afforded the visualization and therapeutic monitoring of CAR-T cells through cellular radiolabeling approach or gene imaging strategies in determining whether CAR-T cells homed and infiltrated into the tumor bed, as well as their survival and persistence in TIME 186. The endogenous cell imaging could reflect the immune status and functional information of T cells and even delineate the developmental trajectory of immune cells. Dynamic monitoring will help researchers understand cellular behavior in vivo, allowing better infusion timing and dosage optimization to avoid potentially lethal systemic toxicity (Figure 4B) 187. As for assessing the prognosis and suitability of CAR-T cell therapy, types of TIME could be considered as a novel biomarker to stratify the overall survival risk of untreated tumor patients and tertiary lymphoid structure (TLS) could be used as a sign of effective immunotherapies 179, 188. Upregulation of TLS in most tumors could foster CAR-T cell immunotherapy 188.

Until recently, tumor-on-chip offered a renewed direction for preclinical CAR-T cell research. Compared with conventional in vivo animal models and in vitro planar cell models, emerging tumor-on-chip platforms integrating microfluidics, tissue engineering, and 3D cell culture have successfully mimicked the key structural and functional properties of TME in vivo 189-191. Several studies have attempted to generate functional immune cells from human pluripotent stem cells in combination with neo-platforms, such as the generation of T-cell progenitors from hematopoietic organoids 192 and the invention of hematopoietic organs-on-chips 193. The studies pushed the limit of pluripotent stem cells to produce immune cells useful for CAR-T therapy. Thus, tumor/organ-on-chip platforms hold great promise as more accurate and realistic models for investigating the immunosuppressive mechanisms of TIME as well as the drug toxicity and efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy before being applied to individuals. Additionally, using a comprehensive single-cell gene expression and TCR sequencing dataset for pre- and post-infusion CAR-T cells, Wilson et al. 194 found a unique signature of CAR-T cell effector precursors present in pre-infusion cell products. These effector precursor CAR-T cells exhibited functional superiority and decreased expression of the exhaustion-associated transcription factor, consistent with post-infusion cellular patterns observed in patients. Engineering alternative immune cells (such as NK and macrophages) to express CAR targeting molecules is also an optimal strategy. CAR-NK cells or macrophages were shown to induce a pro-inflammatory TIME and boost anti-tumor T cell activity 195, 196. Collectively, these nascent technologies or preclinical studies offer great potential for therapeutic applications.

5. Conclusion

CAR-T immunotherapy is revolutionizing the paradigm of cancer therapy. However, unique obstacles posed by solid tumors remain a Gordian knot for CAR-T immunotherapy. The intricate interactions among immune cells, tumor cells, immune molecules, and cytokines form TIME that throttles immune responses and encourages tumor development. By precisely mapping the complex regulatory network of TIME and drawing the optimization strategies, we could provide patients with more effective and tailored CAR-T immunotherapy. To address the hostile TIME and mitigate or even obviate the risk of serious adverse reactions, cutting-edge technologies, such as nanoparticle delivering systems, radionuclide-based molecular imaging, and novel tumor-on-chip platforms are gradually applied for CAR-T immunotherapy. Indeed, the current understanding of TIME is only the tip of an iceberg. Nevertheless, we believe that by progressively regulating the harsh TIME to reshape a friendly microenvironment, CAR-T immunotherapy will produce a more astonishing breakthrough.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

ZQL, XWH, and QD provided direction and guidance throughout the preparation of this manuscript. ZKZ, ZQL, and QD wrote and edited the manuscript. QD reviewed and made significant revisions to the manuscript. HX, JXL, HYL, QD, and ZQL collected and prepared the related papers. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BiTE

bispecific T cell engager

- Breg

regulatory B cell

- CAR

chimeric antigen receptor

- CTL

cytotoxic lymphocyte

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4

- CXCL

CXC chemokine ligand

- DC

dendritic cell

- DNR

dominant-negative receptor

- FcγR

Fc gamma receptor

- FRβ

folate receptor beta

- GD2

disialoganglioside

- GITR

glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor

- GM-CSF

granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- G-MDSC

granulocytic MDSC

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- ICOS

inducible co-stimulator

- IFN-γ

interferon-gamma

- IL

interleukin

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide

- LAG-3

lymphocyte activation gene-3

- L-Arg

L-Arginine

- MC

Mast cell

- M-CSF

macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- MDSC

myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- M-MDSC

monocytic MDSC

- Msln

mesothelin

- NAP

neutrophil-activating protein

- NK cell

natural killer cell

- Nrf2

NF erythroid 2-related factor 2

- PD-1

programmed death-1

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PD-L1

PD-1 ligand

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TADC

tumor-associated dendritic cell

- TAM

tumor-associated macrophage

- TAMC

tumor-associated mast cell

- TAN

tumor associated neutrophil

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- Teff

effector T cell

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- Th1

T helper type 1

- Tim-3

T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3

- TIME

tumor immune microenvironment

- TLS

tertiary lymphoid structure

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- TR2

TRAIL receptor 2

- Treg

regulatory T cell

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- 1.Gupta RG, Li F, Roszik J, Lizee G. Exploiting Tumor Neoantigens to Target Cancer Evolution: Current Challenges and Promising Therapeutic Approaches. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:1024–39. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Ende T, van den Boorn HG, Hoonhout NM, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, Meijer SL, Derks S. et al. Priming the tumor immune microenvironment with chemo(radio)therapy: A systematic review across tumor types. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020;1874:188386. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang X, Han L, Wang R, Zhu W, Zhang N, Qu W. et al. Dual-responsive nanosystem based on TGF-beta blockade and immunogenic chemotherapy for effective chemoimmunotherapy. Drug Deliv. 2022;29:1358–69. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2022.2069877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, Pan Y, Zou K, Lan Z, Cheng G, Mai Q. et al. Biomimetic manganese-based theranostic nanoplatform for cancer multimodal imaging and twofold immunotherapy. Bioact Mater. 2023;19:237–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh Z, Yang Y, Kohler ME. Immunobiology of chimeric antigen receptor T cells and novel designs. Immunol Rev. 2019;290:100–13. doi: 10.1111/imr.12794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feins S, Kong W, Williams EF, Milone MC, Fraietta JA. An introduction to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:S3–S9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Zhu X, Qian Y, Yuan X, Ding Y, Hu D. et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy in Glioblastoma: Current and Future. Front Immunol. 2020;11:594271. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.594271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong M, Clubb JD, Chen YY. Engineering CAR-T Cells for Next-Generation Cancer Therapy. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:473–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyashita M, Sasano H, Tamaki K, Hirakawa H, Takahashi Y, Nakagawa S. et al. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ and FOXP3+ lymphocytes in residual tumors and alterations in these parameters after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer: a retrospective multicenter study. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:124. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0632-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sterner RC, Sterner RM. CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:69. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00459-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka A, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res. 2017;27:109–18. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loeuillard E, Yang J, Buckarma E, Wang J, Liu Y, Conboy C. et al. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages and granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells augments PD-1 blockade in cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:5380–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI137110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez M, Moon EK. CAR T Cells for Solid Tumors: New Strategies for Finding, Infiltrating, and Surviving in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2019;10:128. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen L, Xiao Y, Tian J, Lu Z. Remodeling metabolic fitness: Strategies for improving the efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. Cancer Lett. 2022;529:139–52. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2022.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veglia F, Sanseviero E, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:485–98. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00490-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tcyganov EN, Hanabuchi S, Hashimoto A, Campbell D, Kar G, Slidel TW, Distinct mechanisms govern populations of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in chronic viral infection and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2021. 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Zhao Y, Wu T, Shao S, Shi B, Zhao Y. Phenotype, development, and biological function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1004983. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1004983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, Gabrilovich DI. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:5791–802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang B, Pan PY, Li Q, Sato AI, Levy DE, Bromberg J. et al. Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells mediate the development of tumor-induced T regulatory cells and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1123–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Movahedi K, Guilliams M, Van den Bossche J, Van den Bergh R, Gysemans C, Beschin A. et al. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. 2008;111:4233–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez PC, Ernstoff MS, Hernandez C, Atkins M, Zabaleta J, Sierra R. et al. Arginase I-producing myeloid-derived suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma are a subpopulation of activated granulocytes. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1553–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ko JS, Zea AH, Rini BI, Ireland JL, Elson P, Cohen P. et al. Sunitinib mediates reversal of myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2148–57. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi H, Zhang J, Han X, Li H, Xie M, Sun Y. et al. Recruited monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote the arrest of tumor cells in the premetastatic niche through an IL-1beta-mediated increase in E-selectin expression. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:1370–83. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binsfeld M, Muller J, Lamour V, De Veirman K, De Raeve H, Bellahcene A. et al. Granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote angiogenesis in the context of multiple myeloma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:37931–43. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlecker E, Stojanovic A, Eisen C, Quack C, Falk CS, Umansky V. et al. Tumor-infiltrating monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells mediate CCR5-dependent recruitment of regulatory T cells favoring tumor growth. J Immunol. 2012;189:5602–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beury DW, Parker KH, Nyandjo M, Sinha P, Carter KA, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Cross-talk among myeloid-derived suppressor cells, macrophages, and tumor cells impacts the inflammatory milieu of solid tumors. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;96:1109–18. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A0414-210R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ku AW, Muhitch JB, Powers CA, Diehl M, Kim M, Fisher DT, Tumor-induced MDSC act via remote control to inhibit L-selectin-dependent adaptive immunity in lymph nodes. Elife. 2016. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking inflammation and cancer. J Immunol. 2009;182:4499–506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beury DW, Carter KA, Nelson C, Sinha P, Hanson E, Nyandjo M. et al. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Survival and Function Are Regulated by the Transcription Factor Nrf2. J Immunol. 2016;196:3470–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kusmartsev S, Eruslanov E, Kubler H, Tseng T, Sakai Y, Su Z. et al. Oxidative stress regulates expression of VEGFR1 in myeloid cells: link to tumor-induced immune suppression in renal cell carcinoma. J Immunol. 2008;181:346–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raber PL, Thevenot P, Sierra R, Wyczechowska D, Halle D, Ramirez ME. et al. Subpopulations of myeloid-derived suppressor cells impair T cell responses through independent nitric oxide-related pathways. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:2853–64. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molon B, Ugel S, Del PF, Soldani C, Zilio S, Avella D. et al. Chemokine nitration prevents intratumoral infiltration of antigen-specific T cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1949–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagaraj S, Gupta K, Pisarev V, Kinarsky L, Sherman S, Kang L. et al. Altered recognition of antigen is a mechanism of CD8+ T cell tolerance in cancer. Nat Med. 2007;13:828–35. doi: 10.1038/nm1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez PC, Quiceno DG, Zabaleta J, Ortiz B, Zea AH, Piazuelo MB. et al. Arginase I production in the tumor microenvironment by mature myeloid cells inhibits T-cell receptor expression and antigen-specific T-cell responses. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5839–49. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez PC, Zea AH, DeSalvo J, Culotta KS, Zabaleta J, Quiceno DG. et al. L-arginine consumption by macrophages modulates the expression of CD3 zeta chain in T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2003;171:1232–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Wang L, Chen X, Li L, Li Y, Ping Y. et al. CD39/CD73 upregulation on myeloid-derived suppressor cells via TGF-beta-mTOR-HIF-1 signaling in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1320011. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1320011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamauchi Y, Safi S, Blattner C, Rathinasamy A, Umansky L, Juenger S. et al. Circulating and Tumor Myeloid-derived Suppressor Cells in Resectable Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:777–87. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201708-1707OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guerriero JL. Macrophages: The Road Less Traveled, Changing Anticancer Therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2018;24:472–89. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–44. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Franklin RA, Liao W, Sarkar A, Kim MV, Bivona MR, Liu K. et al. The cellular and molecular origin of tumor-associated macrophages. Science. 2014;344:921–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1252510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wynn TA. Type 2 cytokines: mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:271–82. doi: 10.1038/nri3831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu XL, Pan Q, Cao HX, Xin FZ, Zhao ZH, Yang RX. et al. Lipotoxic Hepatocyte-Derived Exosomal MicroRNA 192-5p Activates Macrophages Through Rictor/Akt/Forkhead Box Transcription Factor O1 Signaling in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology. 2020;72:454–69. doi: 10.1002/hep.31050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye H, Zhou Q, Zheng S, Li G, Lin Q, Wei L. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages promote progression and the Warburg effect via CCL18/NF-kB/VCAM-1 pathway in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:453. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0486-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Q, Lu Y, Li R, Jiang Y, Zheng Y, Qian J. et al. Therapeutic effects of CSF1R-blocking antibodies in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2018;32:176–83. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Georgoudaki AM, Prokopec KE, Boura VF, Hellqvist E, Sohn S, Ostling J. et al. Reprogramming Tumor-Associated Macrophages by Antibody Targeting Inhibits Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2000–11. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mantovani A, Locati M. Macrophage Metabolism Shapes Angiogenesis in Tumors. Cell Metab. 2016;24:653–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan H, Dong M, Liu X, Shen Q, He D, Huang X. et al. Multiple myeloma cell-derived IL-32gamma increases the immunosuppressive function of macrophages by promoting indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) expression. Cancer Lett. 2019;446:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.He L, Jhong JH, Chen Q, Huang KY, Strittmatter K, Kreuzer J. et al. Global characterization of macrophage polarization mechanisms and identification of M2-type polarization inhibitors. Cell Rep. 2021;37:109955. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang J, Zhao Y, Zhang L, Fan H, Qi C, Zhang K. et al. RIPK3/MLKL-Mediated Neuronal Necroptosis Modulates the M1/M2 Polarization of Microglia/Macrophages in the Ischemic Cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28:2622–35. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yin C, Han Q, Xu D, Zheng B, Zhao X, Zhang J. SALL4-mediated upregulation of exosomal miR-146a-5p drives T-cell exhaustion by M2 tumor-associated macrophages in HCC. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:1601479. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1601479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuang DM, Peng C, Zhao Q, Wu Y, Chen MS, Zheng L. Activated monocytes in peritumoral stroma of hepatocellular carcinoma promote expansion of memory T helper 17 cells. Hepatology. 2010;51:154–64. doi: 10.1002/hep.23291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang D, Yang L, Yue D, Cao L, Li L, Wang D. et al. Macrophage-derived CCL22 promotes an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment via IL-8 in malignant pleural effusion. Cancer Lett. 2019;452:244–53. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mamrot J, Balachandran S, Steele EJ, Lindley RA. Molecular model linking Th2 polarized M2 tumour-associated macrophages with deaminase-mediated cancer progression mutation signatures. Scand J Immunol. 2019;89:e12760. doi: 10.1111/sji.12760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Movahedi K, Laoui D, Gysemans C, Baeten M, Stange G, Van den Bossche J. et al. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6C(high) monocytes. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5728–39. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yan W, Liu X, Ma H, Zhang H, Song X, Gao L. et al. Tim-3 fosters HCC development by enhancing TGF-beta-mediated alternative activation of macrophages. Gut. 2015;64:1593–604. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wan S, Zhao E, Kryczek I, Vatan L, Sadovskaya A, Ludema G. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages produce interleukin 6 and signal via STAT3 to promote expansion of human hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1393–404. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dong P, Ma L, Liu L, Zhao G, Zhang S, Dong L. et al. CD86(+)/CD206(+), Diametrically Polarized Tumor-Associated Macrophages, Predict Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patient Prognosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:320. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mehta AK, Kadel S, Townsend MG, Oliwa M, Guerriero JL. Macrophage Biology and Mechanisms of Immune Suppression in Breast Cancer. Front Immunol. 2021;12:643771. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.643771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ohue Y, Nishikawa H. Regulatory T (Treg) cells in cancer: Can Treg cells be a new therapeutic target? Cancer Sci. 2019;110:2080–9. doi: 10.1111/cas.14069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chaudhary B, Elkord E. Regulatory T Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment and Cancer Progression: Role and Therapeutic Targeting. Vaccines (Basel) 2016. 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Togashi Y, Shitara K, Nishikawa H. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunosuppression - implications for anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16:356–71. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cao X, Cai SF, Fehniger TA, Song J, Collins LI, Piwnica-Worms DR. et al. Granzyme B and perforin are important for regulatory T cell-mediated suppression of tumor clearance. Immunity. 2007;27:635–46. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sarvaria A, Madrigal JA, Saudemont A. B cell regulation in cancer and anti-tumor immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14:662–74. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rosser EC, Mauri C. Regulatory B cells: origin, phenotype, and function. Immunity. 2015;42:607–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou X, Su YX, Lao XM, Liang YJ, Liao GQ. CD19(+)IL-10(+) regulatory B cells affect survival of tongue squamous cell carcinoma patients and induce resting CD4(+) T cells to CD4(+)Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells. Oral Oncol. 2016;53:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wei X, Jin Y, Tian Y, Zhang H, Wu J, Lu W. et al. Regulatory B cells contribute to the impaired antitumor immunity in ovarian cancer patients. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:6581–8. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4538-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang L, Tai YT, Ho M, Xing L, Chauhan D, Gang A. et al. Regulatory B cell-myeloma cell interaction confers immunosuppression and promotes their survival in the bone marrow milieu. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7:e547. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2017.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Michaeli J, Shaul ME, Mishalian I, Hovav AH, Levy L, Zolotriov L. et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils induce apoptosis of non-activated CD8 T-cells in a TNFalpha and NO-dependent mechanism, promoting a tumor-supportive environment. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1356965. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1356965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Powell D, Lou M, Barros BF, Huttenlocher A. Cxcr1 mediates recruitment of neutrophils and supports proliferation of tumor-initiating astrocytes in vivo. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13285. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31675-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Andzinski L, Kasnitz N, Stahnke S, Wu CF, Gereke M, von Kockritz-Blickwede M. et al. Type I IFNs induce anti-tumor polarization of tumor associated neutrophils in mice and human. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:1982–93. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]