Abstract

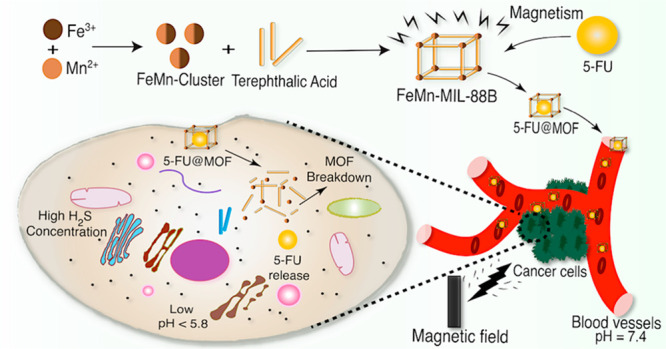

Along with the increasing incidence of cancer and drawbacks of traditional drug delivery systems (DDSs), developing novel nanocarriers for sustained targeted-drug release has become urgent. In this regard, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) have emerged as potential candidates due to their structural flexibility, defined porosity, lower toxicity, and biodegradability. Herein, a FeMn-based ferromagnetic MOF was synthesized from a preassembled Fe2Mn(μ3-O) cluster. The introduction of the Mn provided the ferromagnetic character to FeMn-MIL-88B. 5-Fluoruracil (5-FU) was encapsulated as a model drug in the MOFs, and its pH and H2S dual-stimuli responsive controlled release was realized. FeMn-MIL-88B presented a higher 5-FU loading capacity of 43.8 wt % and rapid drug release behavior in a tumor microenvironment (TME) simulated medium. The carriers can rapidly release loaded drug of 70% and 26% in PBS solution (pH = 5.4) and NaHS solution (500 μM) within 24 h. The application of mathematical release models indicated 5-FU release from carriers can be precisely fitted to the first-order, second-order, and Higuchi models of release. Moreover, the cytotoxicity profile of the carrier against human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293T) suggests no adverse effects up to 100 μg/mL. The lesser toxic effect on cell viability can be attributed to the low toxicity values [LD50 (Fe) = 30 g·kg–1, (Mn) = 1.5 g·kg–1, and (terephthalic acid) = 5 g·kg–1] of the MOFs structural components. Together with dual-stimuli responsiveness, ferromagnetic nature, and low toxicity, FeMn-MIL-88B MOFs can emerge as promising carriers for drug delivery applications.

1. Introduction

Cancer has remained one of the major human diseases with an ever-increasing mortality rate every year.1 Although the quality of knowledge about cancer has improved, its management and eradication still require novel therapeutic approaches.2 Among different influences on therapeutic efficacy, the tumor microenvironment (TME) is considered a crucial aspect. The TME is the location where, apart from tumor cells, blood vessels, extracellular matrix (ECM), and signaling molecules exist.3,4 As compared to normal tissues, the TME consists of a hypoxic environment,5 lower pH6 due to metabolic alterations, and excessive reactive oxygen species.7,8 The major chunk of cancer treatments are still comprised of traditional chemotherapy, surgical resection, and radiotherapy,9 the efficacy of which is hampered due to the nonspecific toxicity, emergence of drug resistance, and cancer metastasis.10

To overcome these challenges, drug delivery systems (DDS), such as quantum dots,11 mesoporous silica,12 nanoparticles,13 dendrimers,14 and liposomes,15 have extensively been studied. Still, their applications are hindered by the limitations of premature degradability, undue toxicity, and lower drug loading capacities.1,16 Among all the available DDS, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), endowed with excellent porosity, tunable character, higher surface areas, and better biocompatibility, exhibit encouraging potential as nanocarriers for anti-cancer drug delivery.17 Since their first use in the sustained release of ibuprofen in 2006,18 MOFs have been extensively modified to be used in advanced drug delivery applications.19

Recently, stimuli-responsive MOFs have gained much attention that in response to internal (e.g., ATP, redox reaction, pH, and H2S) or external stimuli (temperature, pressure, irradiation, and magnetic field) triggered drug delivery.20−24 Among others, magnetically active MOFs can be effectively deployed for target-specific drug delivery, as they can be dragged to a specific location through an external magnetic field.16,25,26 However, magnetically responsive MOF-based nanocarriers usually achieve their magnetic properties through the encapsulation of magnetically active nanostructures (Fe3O4) at the expense of reduced porosity and lowered drug encapsulation efficiency,27,28 whereas introduction of the second metals into the structural nodes of the MOFs is another way to induce magnetic properties without losing porosity.29−32 Among various methods, the secondary building unit (SBU) approach is the most favored one. In this method, presynthesized mixed metal clusters are used to fabricate bimetallic MOFs with a precise ratio of both metals inside the structure.33,34 Keeping in view the lower pH of the TME (pH 5.2–6)35 and higher (H2S) concentration in some cancer types (colon and ovarian),36−39 the pH/H2S-responsive magnetic MOFs could serve as potential DDS for improved therapeutic effects, but they have rarely been studied.

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) is an anti-cancer drug (pyrimidine analog) that has been clinically approved to treat various tumors. It is incorporated into the DNA or RNA and alters their structure, causing cytotoxicity and, ultimately, the death of cancerous cells.40,41 However, because of the rapid degradation rate of 5–10 min,42 its clinical efficacy is still hampered due to the lack of suitable carriers in chemotherapeutics.43,44

In this study, a magnetic bimetallic iron–manganese MOF (FeMn-MIL88B) was synthesized for encapsulation and stimuli-responsive delivery of 5-FU. Through the characterization of powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), UV–vis, and mathematical release models, the drug release behavior of FeMn-MIL-88B was discussed. Moreover, the cytotoxicity profile of the carriers was evaluated in human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthetic Scheme

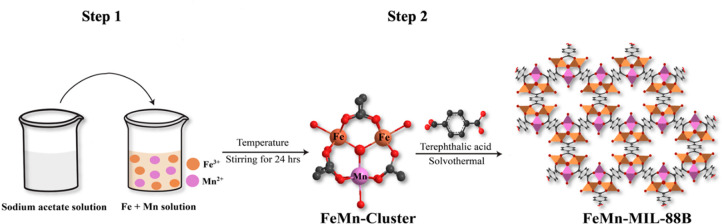

The synthesis of bimetallic (FeMn) MIL-88B MOFs followed a two-step approach (Scheme 1). At first, a bimetallic cluster compound was synthesized following a previously published procedure.45 During synthesis, mixed-metal ions were bridged to a central oxygen (μ3-O) triangularly. In their terminal positions, these metal ions were bonded to solvent molecules (H2O) and also coordinated with acetate ligands and gave a cluster compound with a trinuclear geometry [Fe2Mn(μ3-O)(CH3COO)6(H2O)3].46

Scheme 1. Illustration of the Synthetic Route for the Synthesis of FeMn-MIL-88B.

In the second step, the bimetallic cluster was reacted with the organic linker (terephthalic acid), which displaced the acetate ligands attached to the metal center. This substitution reaction followed a dissociative pathway, resulting in the formation of bimetallic MOFs with MIL-88B type topology.34

2.2. Characterization of Materials

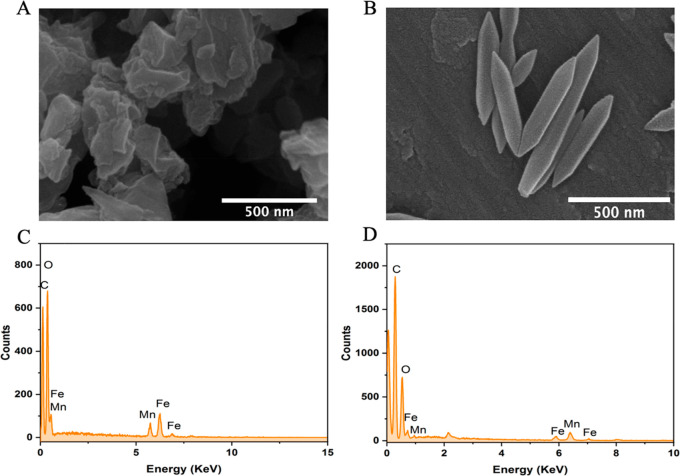

The morphology, crystal size, and elemental composition of the cluster compound and corresponding MOF were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX). SEM analysis of the clusters shows a polycrystalline sample with no defined morphology (Figure 1A), whereas the corresponding FeMn-MIL-88B nanocrystals exhibited a hexagonal rod-shaped morphology (Figure 1B) with an average aspect ratio of 500 ± 116 nm and 140 ± 30 nm diameter (Figure 2D). The size distribution was also analyzed through the dynamic light scattering (DLS) method, and the average size of the particles was found to be 504 nm (Figure S2).

Figure 1.

SEM images (A, B) and EDX spectra (C, D) of the FeMn cluster and FeMn-MIL-88B MOFs.

Figure 2.

PXRD patterns of the FeMn cluster (A) and FeMn-MIL-88B (B). FT-IR spectra (C), aspect ratio (D), N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm (E), and pore size distribution (F) of FeMn-MIL-88B.

The EDX elemental maps confirmed the homogeneous distribution of Fe and Mn elements in a 2:1 ratio in both the cluster (Figure 1C) and FeMn-MIL-88B MOFs (Figure 1D). The elemental composition was further confirmed through inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) analysis of the solubilized samples (Figure S1C). The Fe to Mn ratio in the cluster and FeMn-MIL-88B MOF was found to be 2:1, as also confirmed by the EDX spectra. These results indicated that clusters retained their structural features during the reaction and are present as the metal nodes in the framework.

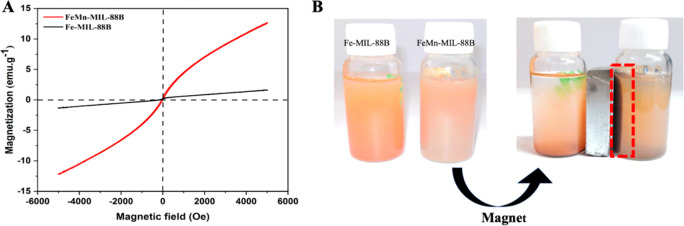

The structural characteristics in terms of the crystallinity and phase purity of the FeMn cluster and FeMn-MIL-88B were analyzed through PXRD measurements. The PXRD pattern of the FeMn cluster (Figure 2A) exhibited a polycrystalline material with characteristic peaks matching well with the reported Fe3O cluster.47 The PXRD pattern of the synthesized MOF crystals reveals a highly crystalline material with prominent reflection peaks and matches well with the simulated pattern of the pure phase MIL-88B MOFs.48 As evident from Figure 1B, FeMn-MIL-88B exhibited three characteristic peaks at 9.1°, 10.5°, and 11.8° corresponding to the 002, 100, and 101 planes.49 A shift from 10.9° for as-synthesized MOFs to 11.8° in the thermally activated MOF was also observed. A shift in the 2θ value to a higher angle represents the cage shrinkage based on Bragg’s law.50 The decrease in cage volume of FeMn-MIL-88B is due to the evacuation of trapped solvent molecules.

The formation of the mixed-metal cluster and the corresponding MOFs was further confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy. The monometallic Fe3O cluster shows a D3h symmetry which breaks to C2v upon the incorporation of one Mn and the formation of a bimetallic cluster (Fe2MnO). In the FT-IR spectra, the characteristic peaks for the Fe3O cluster (at ∼600 cm–1) were absent, and two new metal–oxygen stretchings appeared at 726 and 524 cm–1 corresponding to the FeMn–O linkage in the cluster (Figure S3) and the MOFs (Figure 2C).51 The absorption bands around 1577 and 1409 cm–1 in the FeMn(μ3-O) cluster were attributed to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the -COO bonds of the acetate ligand.52−54 A similar trend was also observed in the IR spectra of the corresponding MOF, and the strong absorption stretching vibrations found around 1373 and 1606 cm–1 were assigned to the asymmetric and symmetric stretchings of the coordinated terephthalic acid.53

Nitrogen physisorption studies at 77 K were carried out to determine the porosity and Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET)-specific surface area of the bimetallic MOF. FeMn-MIL-88B represented a type-I isotherm with a BET surface area of 46 m2·g–1 (Figure 2E). The lower surface area is due to the reversible swelling behavior of the MIL-88B structure, as it tends to shrink into a highly dense and closed form upon thermal activation by subsequent removal of coordinated solvent molecules.55 The FeMn-MIL-88B samples showed characteristics of a microporous structure with an average pore diameter of 1.4 nm and a 0.155 cc·g–1 pore volume (Figure 2F).

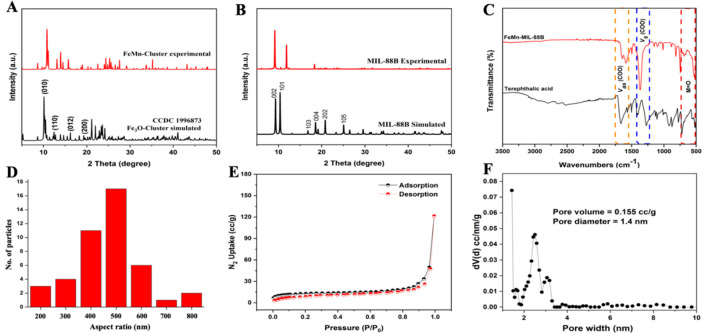

The magnetic behavior of Fe-MIL-88B and FeMn-MIL-88B MOFs was characterized through vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) analysis. From the VSM plots of the MOFs (Figure 3A), it can be observed that the saturation magnetization values for Fe-MIL-88B MOFs and FeMn-MIL-88B are 1.6 emu·g–1 and 12.7 emu·g–1, respectively. From the magnetic hysteresis loop, the coercivity and remanence values were calculated to be zero. The results revealed that the FeMn-MIL-88B MOF shows a superparamagnetic nature compared to Fe-MIL-88B, which renders our bimetallic MOFs susceptible to the magnetic field and easily separable from the reaction mixture by magnetic attraction (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Magnetic hysteresis loop of the VSM studies (A) and magnetic properties of the Fe-MIL-88B (B) checked physically with an external magnet.

2.3. Fabrication of FeMn-MIL-88B/5-FU

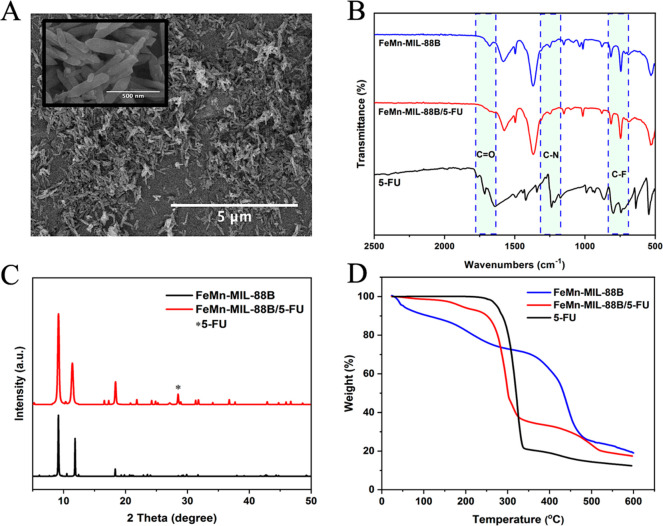

SEM analysis was performed to assess the morphological changes in the crystals after 5-FU impregnation. As seen in Figure 4A, the MOF crystals retain their overall morphological features after encapsulating the drug except for an expansion in the crystal structure leading to swollen crystallites. The drug incorporation into FeMn-MIL-88B was further confirmed by FT-IR, XRD, UV–vis spectroscopy, and TGA analysis. The characteristic peaks in the IR spectra of 5-FU at 1731 and 1240 cm–1 were attributed to the C–O and C–N stretching vibrations of the drug molecule, while the additional characteristic peaks found around 800 cm–1 to 540 cm–1 were ascribed to the C–F deformations of 5-FU.56 These vibrational stretchings were also evident in the IR spectra of FeMn-MIL-88B/5-FU samples (Figure 4B), confirming the loading of 5-FU into the materials.

Figure 4.

SEM image (A, inset: at 500 nm scale), FT-IR spectra (B), PXRD patterns (C), and TGA curves (D) of MOF crystals after contact with 5-FU.

PXRD patterns of the samples were collected to check the effect of drug encapsulation on the carriers. No significant change was observed in the PXRD patterns of the 5-FU encapsulated carriers, and most of the characteristic peaks were retained by the carriers. An extra peak around 28.2 (2θ) found in the PXRD pattern of FeMn-MIL-88B/5-FU was attributed to 5-FU,57−59 confirming its presence in the structure (Figure 4C). Moreover, loading of 5-FU resulted in FeMn-MIL-88B’s pore volume expansion, reflected by the decrease in the diffraction angle of the 101 peak from 11.8 to 11.2 (2θ). These findings further confirm the structural flexibility of FeMn-MIL-88B through the “breathing effect” that enables the carriers to entrap drug molecules with a shrinkable architecture (consistent with the previous literature).46,60−62

Finally, thermogravimetric analysis was carried out to rectify the loading of 5-FU by calculating the decrease in mass of FeMn-MIL-88B and FeMn-MIL-88B/5-FU heated under nitrogen. The samples without 5-FU molecules presented two major weight loss regions. The weight loss below 275 °C corresponded to the removal of any coordinated water/solvent molecules present in the structure, while the major weight loss that occurred from ∼275 to 475 °C was attributed to the decomposition of the terephthalic acid and structural collapse.63 The TGA curve of FeMn-MIL-88B/5-FU lacked most of the initial weight loss pattern for solvent molecules found in FeMn-MIL-88B and indicated the presence of 5-FU molecules inside the pores.7,64−66 However, a 10% weight loss related to solvent molecules can be seen from 150 to 240 °C. The initial weight loss up to 300 °C in FeMn-MIL-88B/5-FU was attributed to the loss of incorporated 5-FU molecules. The second phase of weight loss from 310 to 520 °C was due to the degradation of linker and collapse of the structure (Figure 4D).

By analyzing the IR, PXRD, and TGA results of FeMn-MIL-88B/5-FU, we concluded the successful incorporation of 5-FU into our carriers. To further quantify the amount of drug loaded on the carriers, UV–vis spectroscopy was utilized to determine the concentration of 5-FU at 265 nm (λmax). The loading capacity of the MOFs was found to be ∼438 mg·g–1 correlated with the calibration curve of different 5-FU concentrations in ethanol (Figure S4).

2.4. Release Kinetics

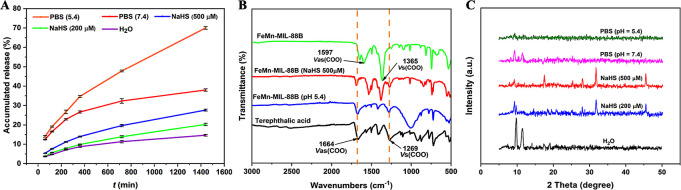

The pH-triggered release of 5-FU from the MOFs was first investigated in PBS solutions (pH 5.4 and pH 7.4), mimicking the pH of the tumor microenvironment and physiological fluid system. The drug release quantity was calculated through the calibration curve drawn in PBS (Figure S6). The drug release can be distinguished into two stages: the first stage involves the rapid release of 5-FU molecules, whereas, in the second stage, drug release occurs in a sustained manner. The initial rapid release of 5-FU from the carriers can be attributed to the loosely bound drug molecules on the surface of the carriers. Under the simulated physiological pH (7.4), a slow and controlled release of 5-FU from the carriers amounted to a cumulative 38% even after 24 h (Figure 5A). The slower drug release at physiological pH is due to the reasonable stability of MIL-88B MOFs at physiological pH and aqueous solutions.67 It is also beneficial to prevent unwanted and untargeted drug releases that may cause toxicity to healthy cells.25 However, a rapid release of 70% from the carriers was observed at a slightly acidic pH (5.4).

Figure 5.

5-FU release from FeMn-MIL-88B/5-FU (A), FT-IR spectra of terephthalic acid and of FeMn-MIL-88B MOFs before and after being contacted with PBS (pH 5.4) and NaHS (500 μM) (B), and PXRD patterns of samples immersed in PBS (pH = 5.4 and 7.4), water, and NaHS solutions (C).

The rapid release under weakly acidic pH could result from MOFs’ structural decomposition due to linker protonation.68,69 To confirm this, the FT-IR spectra of FeMn-MIL-88B MOFs (before and after) immersed in pH 5.4 solution for 24 h and free linker were compared. As shown in Figure 5B, a shift in the antisymmetric and symmetric bands of the coordinated linker from 1597 and 1365 cm–1 to 1627 and 1277 cm–1 in the acid-exposed MOFs hints at the protonation of the linker.51 Consequently, the disintegration of the MOF releases the encapsulated drug molecules. To gain further insights into the MOFs’ behavior under different pH conditions, we performed PXRD analysis of MOFs immersed in PBS (pH = 7.4 and 5.4) for 24 h. These MOFs were able to retain their crystallinity under pH 7.4 (Figure 5C), which corroborates well with previous literature.70,71 However, at pH 5.4, our carriers lost their crystallinity and disintegrated, as shown by the PXRD pattern that appeared featureless.

Furthermore, considering the higher concentration of H2S found in breast and colon cancers, 5-FU release from the nanocarriers was also investigated under a H2S simulating environment. Drug release contents were calculated through the calibration curve of 5-FU drawn from the different concentrations of the drug dissolved in water (Figure S5). Compared to the drug release of 11% in deionized water, rapid release of 5-FU was observed in NaHS solutions. The material showed NaHS concentration-dependent release of the payload. By increasing the NaHS concentration from 200 to 500 μM, a release of 5-FU from 19% to 26% was observed. Such behavior of MOFs upon contacting NaHS solution is due the strong affinity of the S atom toward Fe ions in the nanocarriers and their competitive binding against the linker.72 According to the previously published reports, Fe3+ in the MOFs is rapidly seized by H2S due to ultrahigh affinity between S2– and Fe3+ resulting in the formation of Fe2S3. The intermediate product (Fe2S3) is unstable and rapidly converts into FeS and S. The strong coordination between Fe and S results in the breakage of other metal bonds (e.g., of metal–linker) and ultimately results in the release of the linker and MOFs’ decomposition. The emergence of extra peaks at 28°, 32°, and 45–47° (2θ) in the PXRD pattern (Figure 5C) of the NaHS-immersed samples indicates the presence of a metal–sulfide linkage73−75 and correlates to the decomposition phenomenon. We also compared the FT-IR analysis of the NaHS immersed samples with non-NaHS-exposed samples and a free linker. As shown in Figure 5B, the emergence of the antisymmetric and symmetric vibrational stretchings of -COO at 1638 and 1271 cm–1 in the NaHS-exposed samples indicates the presence of an uncoordinated linker.51 Furthermore, by comparing the recently reported MOFs for anti-cancer drug delivery (Table S1), FeMn-MIL-88B exhibits a higher loading capacity of 5-FU. Our MOFs also bypass the laborious step of loading superparamagnetic oxides or making MOF-based composites to achieve the magnetic character and dual-stimuli responsiveness.

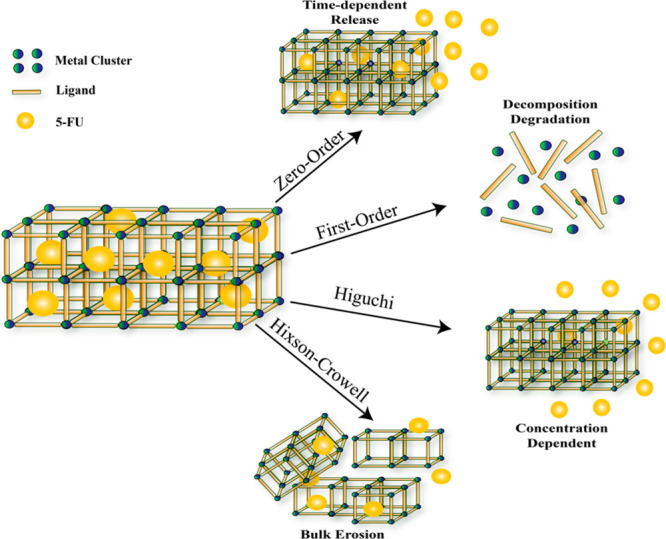

We applied several mathematical kinetic release models to better understand the factors behind the drug release behavior of FeMn-MIL-88B (Figure S7). The summary of the drug delivery mechanisms by their correlating fitting models is presented in Scheme 2 and Table 1. The drug release kinetics from a carrier depends on different factors such as drug movement, the carrier’s swelling nature, interaction with the guest molecules, and degradation.76,77 The zero-order release model relies on Fick’s law of diffusion and evaluates the drug release kinetics from diffusion-controlled carriers.76 Similarly, the Higuchi model is based on the principle of drug release from insoluble carriers.78 The first-order and Hixson–Crowell models describe the drug release by complete decomposition or block erosion of the material.79,77

Scheme 2. Illustrative Scheme of 5-FU Release from FeMn-MIL-88B.

Table 1. Drug Release Kinetic Parameters and Mathematical Models.

| Drug release medium | Parameters | Zero-order model | First-order model | Higuchi model | Hixon-Crowell model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS (7.4) | R2 | 0.984 | 0.9983 | 0.994 | 0.9356 |

| PBS (5.4) | R2 | 0.9452 | 0.9673 | 0.9979 | 0.8801 |

| NaHS (500 μM) | R2 | 0.9199 | 0.9875 | 0.9974 | 0.9014 |

The regression coefficient (R2) of each model was evaluated to fit the accuracy of the statistical models (Table 1). In our case, the higher R2 (>0.96) values of the zero-order, first-order, and Higuchi models for release kinetics suggest the release of 5-FU from the carriers in a complex manner. The drug release occurs through diffusion, dissolution, and structural decomposition of the carriers.

2.5. Cytotoxicity Studies

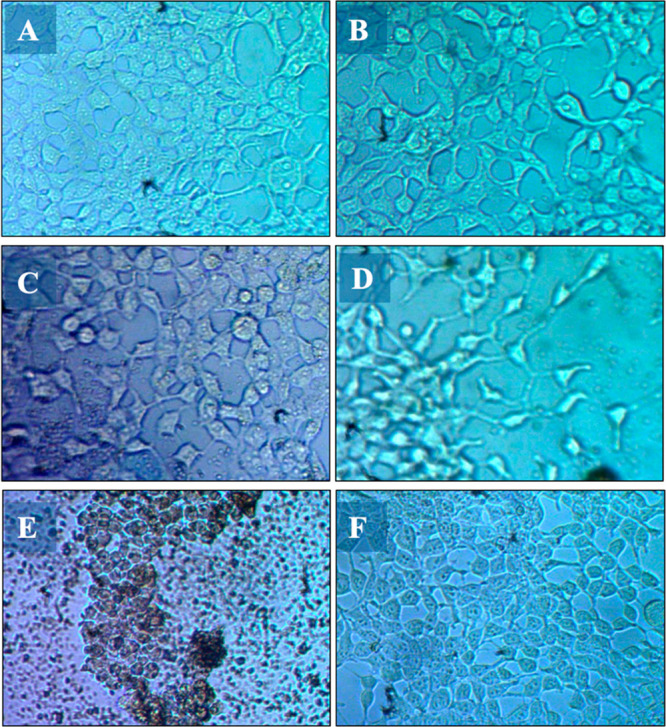

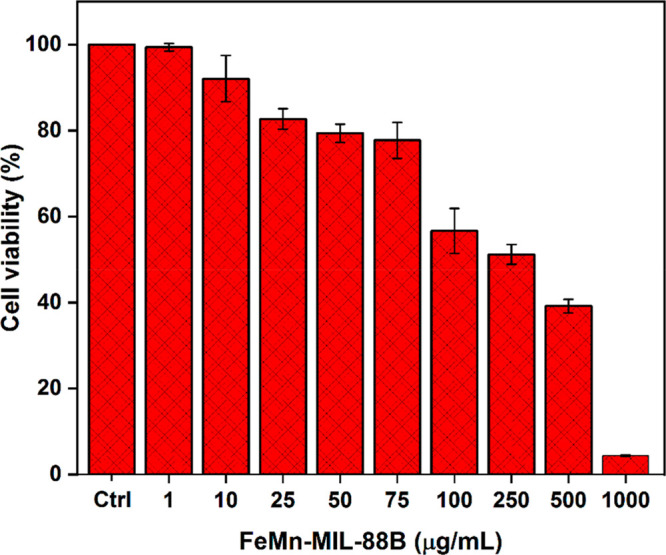

The HEK293T cells belong to a class of human embryonic kidney cell lines widely utilized to assess the toxicity of materials.80 The optical images of the HEK293T cells treated with FeMn-MIL-88B nanocarriers exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity.

The non-MOF-exposed (control group) cells appear in a spindle-shaped morphology, which is typical of the untreated version of HEK293T cells.81,82 However, when these cells were treated with MOFs, a morphology and cell density change was observed (Figure 6). Upon a gradual increase in the MOFs’ concentration (50 μg·mL–1 to 1000 μg·mL–1), cells started to lose their defined morphological characteristics and number. The chemical composition of FeMn-MIL-88B might be the reason behind their improved biocompatibility as compared to other nanomaterials (e.g., nanoparticles).83 The lower LD50 values of Fe, Mn, and terephthalic acid (BDC) (Fe = 30 g·kg–1, Mn = 1.5 g·kg–1, and BDC = 5 g·kg –1) constituting FeMn-MIL-88B make it less toxic to HEK293T cells.84 For further confirmation, an MTT assay was performed to assess the cell viability (Figure 7). Compared to the control group, HEK293T cells treated with different concentrations of nanocarriers exhibited a reduction in the cell viability by an increase in the concentration of the MOFs. An obvious decrease in the cell viability (51.2%) was observed upon reaching the nanocarrier concentration of 250 μg·mL–1 with an IC50 = 180 μg·mL–1.

Figure 6.

Images of HEK293T cells after being exposed to varying concentrations of FeMn-MIL-88B MOFs for 72 h using an inverted microscope: 50 μg/mL (A), 100 μg/mL (B), 250 μg/mL (C), 500 μg/mL (D), 1000 μg/mL (E), and control group (F).

Figure 7.

Effect of FeMn-MIL-88B on HEK293T cells by the MTT assay. Cell viability was tested by measuring the OD570 of the HEK293T cells treated with varying concentrations (1–1000 μg/mL with ctrl = control) of FeMn-MIL-88B.

3. Conclusions

In this study, ferromagnetic FeMn-MIL-88B nanocarriers were synthesized by a two-step approach. They were utilized as pH/H2S sensitive DDS for the encapsulation and delivery of an anti-cancer drug (5-FU). The cumulative release of 5-FU from the vehicles arrived at ∼70% and ∼38% in the PBS solutions (pH = 5.4 and 7.4) after 24 h. The mechanism behind the rapid release of the drug molecules in a simulated cancer environment (PBS, pH = 5.4) was analyzed through PXRD, ICP-OES, FT-IR, and release kinetic models. The strong binding affinity between the Fe ions in the carrier and the S atoms of the NaHS in the H2S simulated microenvironment also influenced the 5-FU release in the NaHS solutions as compared to water. The cumulative release percent in NaHS solutions (200 μM and 500 μM) arrived at ∼19% and 26%, while, for water, it only stood at 12% after 24 h. By studying the PXRD patterns, FT-IR spectra, and release kinetic models, the 5-FU release can be attributed to the disintegration and decomposition of FeMn-MIL-88B’s structure. The release behavior in PBS and NaHS solutions can be fitted well with the zero-order, first-order, and Higuchi models of drug release. The low toxicity against HEK293T cells and its ferromagnetic and dual-stimulus (pH and H2S) sensitive nature makes FeMn-MIL-88B an excellent candidate for anti-cancer drug delivery.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

Iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O), manganese(II) nitrate tetrahydrate (Mn(NO3)2·4H2O), 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid (BDC/terephthalic acid), sodium acetate trihydrate (CH3COONa·3H2O), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Methanol (CH3OH) and water (H2O) used were of HPLC grade. All of the chemicals were used as received.

4.2. Synthesis of the Mixed-Metal Cluster

Mixed metal clusters (FeMn) were synthesized following a previous method.45 In a typical synthesis, CH3COONa·3H2O (12 g, 0.088 mol) was dissolved in 20 mL deionized (D.I) water in a 50 mL beaker and called solution-1. A mixed solution of Fe(NO3)3·9H2O (2.284 g, 0.0056 mol) and Mn(NO3)2·4H2O (8.308 g, 0.028 mol) in 20 mL D.I. water in another beaker (solution-2) was prepared, filtered, and kept on stirring. After that, solution-1 was added dropwise into a stirred solution-2. The reaction mixture was kept on stirring for 24 h at room temperature. After 24 h, dark brown precipitates were filtered off and washed once with a small amount of absolute ethanol. Finally, the product was left to air-dry.

4.3. Synthesis of MOFs (FeMn-MIL-88B)

For the synthesis of FeMn-MIL-88B, equimasses of the corresponding bimetallic cluster (100 mg) and BDC (100 mg) were dissolved in 7.5 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide. Sample vials were sonicated until the clusters and linker were dissolved. Later, the dissolved cluster was added dropwise to a stirred linker solution along with 0.5 mL of glacial acetic acid. The mother solution was kept on stirring for 1 h until a homogeneous solution was obtained. Finally, all reactants were transferred to 25 mL Pyrex vials and incubated at 120 °C for 24 h. After that, precipitates were obtained with centrifugation and washed thrice with DMF and ethanol. Further, samples were vacuum-dried for 24 h at 120 °C before characterization.

4.4. Characterization

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the samples was obtained on a BRUKUER (D2 Phaser) diffractometer over a 2θ range from 5 to 80° using Ni-filtered Cu Kα irradiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). The surface morphology of the MOFs was characterized through an FEI NOVA Nano SEM 450 scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray spectroscope (EDX). The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm was calculated using Quantachrome Nova 2200e. The FT-IR spectra of the samples were assessed in the range of 400–4000 cm–1 using a Bruker Alpha Platinum ATR instrument. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed under an N2 atmosphere in the temperature range of 10 to 600 °C (10°/min ramp) using the TA Instruments (SDT Q600). The particle size of the MOFs was determined on a Malvern Zetasizer (Nano ZS, Malvern) using dynamic light scattering (DLS) at room temperature. The magnetic properties of MIL-88B (Fe) and FeMn-MIL-88B were analyzed by a physical magnetic system and vibrating-sample magnetometer (Cryogenic Ltd.). The high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system used was manufactured by The Waters Alliance (Model e2695) and equipped with a (Waters 2998) photodiode array detector and fitted with a C18 column. UV–vis spectroscopy was performed to determine the drug content in the liquid samples using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800).

4.5. Preparation of FeMn-MIL-88B/5-FU

60 mg of MOF samples was immersed in 30 mL of ethanolic solution with a 6000 ppm concentration of 5-FU. The immersed samples were put on an orbital shaker for 48 h. After the adsorption process, the filtrate was obtained through centrifugation and further used to calculate the adsorbed 5-FU in the samples through the UV–vis spectrophotometer. The drug loading capacity of the MOFs was measured by the following equation:85

In this equation, C0 and Cf correspond to the initial and final concentrations of 5-FU in the ethanolic solution, whereas V is the solution’s volume and m indicates the mass of the final MOFs (dried at 50 °C for 24 h).

4.6. In Vitro Drug Release

The detailed 5-FU release from the samples was carried out by exposing the 5-FU-loaded MOFs to 80 mL of PBS (pH 5.4 and 7.4), NaHS (220 and 500 μM) solutions, and D.I. water. Briefly, a dialysis bag (3500 MWCO) containing a concentrated solution of FeMn-MIL-88B/5-FU was put into 80 mL of PBS, NaHS, or water-containing beaker, and dialysis was carried out under magnetic stirring at 37 °C constant temperature. After predetermined intervals, 2 mL of the solution was withdrawn and the same amount of the fresh solution was added to maintain the total volume at a constant concentration. The withdrawn mixture was used to calculate the drug release using HPLC with mobile phase 5% methanol and 95% water at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The 5-FU content was detected at 265 nm wavelength. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and final results were realized through averaging. The equation used to determine the cumulative release percentages of 5-FU is as follows:

where Rt is the concentration of 5-FU released from the MOFs at time t and Rf is the amount of total 5-FU concentration present in the carriers.

4.7. Cell Culture

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK293T cells) were obtained from the NIBGE Cell Culture Collection (NCCC) and were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium) supplemented with 10% Hi-FBS, 1% Pen-strep (100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin), 2 mM l-glutamine, and 1% nonessential amino acids (NEAAs). The cells were grown in cell culture flasks (tissue culture treated) and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Every 3–5 days, the cells were treated with 1–2 mL of 0.25% trypsin–EDTA solution and were subcultured at a 1:3 split ratio.

4.8. Cell Viability Test

MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay was used for cytotoxicity studies and calculation of cell viability. For this purpose, 100 μL of HEK293T cells with a 0.1 × 106 cells/mL density was seeded in a 96 well plate. The cell culture medium was removed after overnight incubation, and FeMn-MIL-88B was dissolved appropriately in the cell culture medium and was added immediately into the cells after sonication. The cells were treated with FeMn-MIL-88B (1–1000 μg/mL). After 72 h of treatment, 10 μL of MTT (12 mM) reagent was added to each well. Before the addition of the MTT reagent, the morphological changes in cells were observed with an inverted phase-contrast microscope (IMT-2; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The cells were incubated for 4 h; after the removal of medium from the wells, 100 μL of DMSO was added to dissolve formazan, i.e. the end product. A Synergy H1 hybrid multimode microplate reader (BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) was used to check the absorbance of samples at 570 nm. The percentage of viable cells was calculated by the following formula: % = [100 × (sample abs/control abs)]. The IC50 of FeMn-MIL-88B treated cells was calculated by Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Faculty Initiative Fund (grant no. FIF-739) by Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS). M.U.A. acknowledges LUMS and Gomal University for providing technical support and curriculum base for the investigations in the project. The authors would also like to extend their gratitude to National Institute for Biotechnology and Genetics Engineering (NIBGE) for providing technical support in the project.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c04144.

SEM, elemental maps, ICP-OES reports, particle size distribution by DLS, FT-IR spectra, calibration curves, release kinetic models, and comparison table for stimuli responsive MOFs (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wang Y.; Yan J.; Wen N.; Xiong H.; Cai S.; He Q.; Hu Y.; Peng D.; Liu Z.; Liu Y. Metal-organic frameworks for stimuli-responsive drug delivery. Biomaterials 2020, 230, 119619. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y.; Sun J.; Qv N.; Zhang G.; Yu T.; Piao H. Application of molecular imaging technology in tumor immunotherapy. Cell. Immunol. 2020, 348, 104039. 10.1016/j.cellimm.2020.104039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quail D. F.; Joyce J. A. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19 (11), 1423–1437. 10.1038/nm.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junttila M. R.; De Sauvage F. J. Influence of tumour micro-environment heterogeneity on therapeutic response. Nature 2013, 501 (7467), 346–354. 10.1038/nature12626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu A.; Kwon I.; Tae G. Improving cancer therapy through the nanomaterials-assisted alleviation of hypoxia. Biomaterials 2020, 228, 119578. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb B. A.; Chimenti M.; Jacobson M. P.; Barber D. L. Dysregulated pH: a perfect storm for cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11 (9), 671–677. 10.1038/nrc3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An J.; Geib S. J.; Rosi N. L. Cation-triggered drug release from a porous zinc– adeninate metal– organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131 (24), 8376–8377. 10.1021/ja902972w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes J. D.; Dinkova-Kostova A. T.; Tew K. D. Oxidative stress in cancer. Cancer cell 2020, 38 (2), 167–197. 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Bernards R. Taking advantage of drug resistance, a new approach in the war on cancer. Front. Med. 2018, 12 (4), 490–495. 10.1007/s11684-018-0647-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Fan W.; Zhang Z.; Wen Y.; Xiong L.; Chen X. Advanced nanotechnology leading the way to multimodal imaging-guided precision surgical therapy. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31 (49), 1904329. 10.1002/adma.201904329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadian S.; Najafi K.; Sadrpoor S. M.; Ektefa F.; Dalir N.; Nikkhah M. Graphene quantum dots based magnetic nanoparticles as a promising delivery system for controlled doxorubicin release. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 331, 115746. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen S.; Gorain B.; Choudhury H.; Chatterjee B. Exploring the role of mesoporous silica nanoparticle in the development of novel drug delivery systems. Drug Delivery Transl. Res. 2021, 12, 105–123. 10.1007/s13346-021-00935-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X.; He C.; Lin W. Supramolecular metal-based nanoparticles for drug delivery and cancer therapy. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2021, 61, 143–153. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gökçe B. B.; Boran T.; Emlik Çalık F.; Özhan G.; Sanyal R.; Güngör S. Dermal delivery and follicular targeting of adapalene using PAMAM dendrimers. Drug Delivery Transl. Res. 2021, 11 (2), 626–646. 10.1007/s13346-021-00933-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães D.; Cavaco-Paulo A.; Nogueira E. Design of liposomes as drug delivery system for therapeutic applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 601, 120571. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M. X.; Yang Y. W. Metal–organic framework (MOF)-based drug/cargo delivery and cancer therapy. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29 (23), 1606134. 10.1002/adma.201606134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y.-B.; Wang S.; He X.; Tang W.; Wang J.; Shao A.; Zhang J. A combination of glioma in vivo imaging and in vivo drug delivery by metal–organic framework based composite nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7 (48), 7683–7689. 10.1039/C9TB01651A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horcajada P.; Serre C.; Vallet-Regí M.; Sebban M.; Taulelle F.; Férey G. Metal–organic frameworks as efficient materials for drug delivery. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 118 (36), 6120–6124. 10.1002/ange.200601878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson H. D.; Walton S. P.; Chan C. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Drug Delivery: A Design Perspective. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13 (6), 7004–7020. 10.1021/acsami.1c01089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W.; Wang J.; Chu C.; Chen W.; Wu C.; Liu G. Metal–organic framework-based stimuli-responsive systems for drug delivery. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6 (1), 1801526. 10.1002/advs.201801526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani K.; Arkan E.; Derakhshankhah H.; Haghshenas B.; Jahanban-Esfahlan R.; Jaymand M. A novel bioreducible and pH-responsive magnetic nanohydrogel based on β-cyclodextrin for chemo/hyperthermia therapy of cancer. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 252, 117229. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K.; Luo H.; Zeng M.; Jiang Y.; Li J.; Fu X. Intracellular pH-triggered, targeted drug delivery to cancer cells by multifunctional envelope-type mesoporous silica nanocontainers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7 (31), 17399–17407. 10.1021/acsami.5b04684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kankala R. K.; Han Y. H.; Na J.; Lee C. H.; Sun Z.; Wang S. B.; Kimura T.; Ok Y. S.; Yamauchi Y.; Chen A. Z. Nanoarchitectured structure and surface biofunctionality of mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32 (23), 1907035. 10.1002/adma.201907035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjua A. C.; Alves V. D.; Crespo J. o. G.; Portugal C. A. Magnetic responsive PVA hydrogels for remote modulation of protein sorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11 (23), 21239–21249. 10.1021/acsami.9b03146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke F.; Yuan Y.-P.; Qiu L.-G.; Shen Y.-H.; Xie A.-J.; Zhu J.-F.; Tian X.-Y.; Zhang L.-D. Facile fabrication of magnetic metal–organic framework nanocomposites for potential targeted drug delivery. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21 (11), 3843–3848. 10.1039/c0jm01770a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. n.; Zhou M.; Li S.; Li Z.; Li J.; Wu B.; Li G.; Li F.; Guan X. Magnetic metal–organic frameworks: γ-Fe2O3@ MOFs via confined in situ pyrolysis method for drug delivery. Small 2014, 10 (14), 2927–2936. 10.1002/smll.201400362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza B. E.; Tan J.-C. Mechanochemical approaches towards the in situ confinement of 5-FU anti-cancer drug within MIL-100 (Fe) metal–organic framework. CrystEngComm 2020, 22 (27), 4526–4530. 10.1039/D0CE00638F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Javanbakht S.; Hemmati A.; Namazi H.; Heydari A. Carboxymethylcellulose-coated 5-fluorouracil@ MOF-5 nano-hybrid as a bio-nanocomposite carrier for the anti-cancer oral delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 876–882. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Liu X.; Yang Q.; Wei Q.; Xie G.; Chen S. Mixed-metal–organic frameworks (M′ MOFs) from 1D to 3D based on the “organic” connectivity and the inorganic connectivity: syntheses, structures and magnetic properties. CrystEngComm 2015, 17 (17), 3312–3324. 10.1039/C5CE00126A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng M.-H.; Wang B.; Wang X.-Y.; Zhang W.-X.; Chen X.-M.; Gao S. Chiral magnetic metal-organic frameworks of dimetal subunits: magnetism tuning by mixed-metal compositions of the solid solutions. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45 (18), 7069–7076. 10.1021/ic060520g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z.; Han X.; Liu Y.; Xu W.; Wu Q.; Xie Q.; Zhao Y.; Hou H. Metal-dependent photocatalytic activity and magnetic behaviour of a series of 3D Co–Ni metal organic frameworks. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48 (18), 6191–6197. 10.1039/C9DT00968J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows A. D. Mixed-component metal–organic frameworks (MC-MOFs): enhancing functionality through solid solution formation and surface modifications. CrystEngComm 2011, 13 (11), 3623–3642. 10.1039/c0ce00568a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L.; Asgari M.; Mieville P.; Schouwink P.; Bulut S.; Sun D. T.; Zhou Z.; Pattison P.; Van Beek W.; Queen W. L. Using predefined M3 (μ3-O) clusters as building blocks for an isostructural series of metal–organic frameworks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9 (28), 23957–23966. 10.1021/acsami.7b06041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Cong H.; Deng H. Deciphering the spatial arrangement of metals and correlation to reactivity in multivariate metal–organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (42), 13822–13825. 10.1021/jacs.6b08724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B.; Chen H.; Liang D.; Lin W.; Qi X.; Liu H.; Deng X. Acidic pH and high-H2O2 dual tumor microenvironment-responsive nanocatalytic graphene oxide for cancer selective therapy and recognition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11 (12), 11157–11166. 10.1021/acsami.8b22487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Niu M.; Wang W.; Su L.; Feng H.; Lin H.; Ge X.; Wu R.; Li Q.; Liu J. In situ activatable ratiometric NIR-II fluorescence nanoprobe for quantitative detection of H2S in colon cancer. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93 (27), 9356–9363. 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c00427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S.; Li J.; Huang Z.; Yue T.; Zhu J.; Wang X.; Liu Y.; Wang P.; Chen S. The CBS-H2S axis promotes liver metastasis of colon cancer by upregulating VEGF through AP-1 activation. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 126 (7), 1055–1066. 10.1038/s41416-021-01681-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Zhu Y.; Liang L.; Wang C.; Ning X.; Feng X.. Self-Assembly of Intelligent Nanoplatform for Endogenous H2S-Triggered Multimodal Cascade Therapy of Colon Cancer. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 4207–4214 10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c01131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velusamy N.; Binoy A.; Bobba K. N.; Nedungadi D.; Mishra N.; Bhuniya S. A bioorthogonal fluorescent probe for mitochondrial hydrogen sulfide: new strategy for cancer cell labeling. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53 (62), 8802–8805. 10.1039/C7CC05339H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson M.; Gustavsson M.; Hu G.-Z.; Murén E.; Ronne H. A Ham1p-dependent mechanism and modulation of the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway can both confer resistance to 5-fluorouracil in yeast. PloS one 2013, 8 (10), e52094. 10.1371/journal.pone.0052094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojardin L.; Botet J.; Quintales L.; Moreno S.; Salas M. New insights into the RNA-based mechanism of action of the anti-cancer drug 5′-fluorouracil in eukaryotic cells. PloS one 2013, 8 (11), e78172. 10.1371/journal.pone.0078172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leelakanok N.; Geary S.; Salem A. Fabrication and use of poly (d, l-lactide-co-glycolide)-based formulations designed for modified release of 5-fluorouracil. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 107 (2), 513–528. 10.1016/j.xphs.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bag P. P.; Wang D.; Chen Z.; Cao R. Outstanding drug loading capacity by water stable microporous MOF: a potential drug carrier. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52 (18), 3669–3672. 10.1039/C5CC09925K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-B.; Cui T.-J.; Lin G.; Wang F.; Zhang J. Sodalite-type metal-organic zeolite with uncoordinated N-sites as potential anti-cancer drug 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) delivery platform. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2019, 109, 107560. 10.1016/j.inoche.2019.107560. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lionet Z.; Nishijima S.; Kim T.-H.; Horiuchi Y.; Lee S. W.; Matsuoka M. Bimetallic MOF-templated synthesis of alloy nanoparticle-embedded porous carbons for oxygen evolution and reduction reactions. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48 (37), 13953–13959. 10.1039/C9DT02943E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horcajada P.; Salles F.; Wuttke S.; Devic T.; Heurtaux D.; Maurin G.; Vimont A.; Daturi M.; David O.; Magnier E. How linker’s modification controls swelling properties of highly flexible iron (III) dicarboxylates MIL-88. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133 (44), 17839–17847. 10.1021/ja206936e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Lievanos K. R.; Tariq M.; Brennessel W. W.; Knowles K. E. Heterometallic trinuclear oxo-centered clusters as single-source precursors for synthesis of stoichiometric monodisperse transition metal ferrite nanocrystals. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49 (45), 16348–16358. 10.1039/D0DT01369B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong G.-T.; Pham M.-H.; Do T.-O. Synthesis and engineering porosity of a mixed metal Fe2Ni MIL-88B metal–organic framework. Dalton Transactions 2013, 42 (2), 550–557. 10.1039/C2DT32073H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horcajada P.; Serre C.; Maurin G.; Ramsahye N. A.; Balas F.; Vallet-Regi M.; Sebban M.; Taulelle F.; Férey G. Flexible porous metal-organic frameworks for a controlled drug delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130 (21), 6774–6780. 10.1021/ja710973k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragg W. L.The diffraction of short electromagnetic waves by a crystal. Scientia 1929, 23 ( (45), ), 153. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal B.; Saleem M.; Arshad S. N.; Rashid J.; Hussain N.; Zaheer M. One-Pot Synthesis of Heterobimetallic Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for Multifunctional Catalysis. Chem. - Eur. J. 2019, 25 (44), 10490–10498. 10.1002/chem.201901939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham M.-H.; Vuong G.-T.; Vu A.-T.; Do T.-O. Novel route to size-controlled Fe–MIL-88B–NH2 metal–organic framework nanocrystals. Langmuir 2011, 27 (24), 15261–15267. 10.1021/la203570h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. L.; Zhao X. J.; Yang X. X.; Li Y. F. A nanosized metal–organic framework of Fe-MIL-88NH 2 as a novel peroxidase mimic used for colorimetric detection of glucose. Analyst 2013, 138 (16), 4526–4531. 10.1039/c3an00560g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T.-z.; Lu Y.; Li Y.-g.; Zhang Z.; Chen W.-l.; Fu H.; Wang E.-b. Metal–organic frameworks constructed from three kinds of new Fe-containing secondary building units. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2012, 384, 219–224. 10.1016/j.ica.2011.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M.; Bétard A.; Weber I.; Al-Hokbany N. S.; Fischer R. A.; Metzler-Nolte N. Iron-based metal–organic frameworks MIL-88B and NH2-MIL-88B: high quality microwave synthesis and solvent-induced lattice “breathing. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13 (6), 2286–2291. 10.1021/cg301738p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhuri A. R.; Laha D.; Pal S.; Karmakar P.; Sahu S. K. One-pot synthesis of folic acid encapsulated upconversion nanoscale metal organic frameworks for targeting, imaging and pH responsive drug release. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45 (45), 18120–18132. 10.1039/C6DT03237K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashour A. E.; Badran M.; Kumar A.; Hussain T.; Alsarra I. A.; Yassin A. E. B. Physical pegylation enhances the cytotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil-loaded PLGA and PCL nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 9259. 10.2147/IJN.S223368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezekiel C. I.; Bapolisi A. M.; Walker R. B.; Krause R. W. M. Ultrasound-Triggered Release of 5-Fluorouracil from Soy Lecithin Echogenic Liposomes. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13 (6), 821. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13060821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moisescu-Goia C.; Muresan-Pop M.; Simon V. New solid state forms of antineoplastic 5-fluorouracil with anthelmintic piperazine. J. Mol. Struct. 2017, 1150, 37–43. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2017.08.076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loiseau T.; Serre C.; Huguenard C.; Fink G.; Taulelle F.; Henry M.; Bataille T.; Férey G. A rationale for the large breathing of the porous aluminum terephthalate (MIL-53) upon hydration. Chem. - Eur. J. 2004, 10 (6), 1373–1382. 10.1002/chem.200305413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M.; Noei H.; Mienert B.; Niesel J.; Bill E.; Muhler M.; Fischer R. A.; Wang Y.; Schatzschneider U.; Metzler-Nolte N. Iron metal–organic frameworks MIL-88B and NH2-MIL-88B for the loading and delivery of the gasotransmitter carbon monoxide. Chem. - Eur. J. 2013, 19 (21), 6785–6790. 10.1002/chem.201201743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton R. I.; Munn A. S.; Guillou N.; Millange F. Uptake of Liquid Alcohols by the Flexible FeIII Metal–Organic Framework MIL-53 Observed by Time-Resolved In Situ X-ray Diffraction. Chem. - Eur. J. 2011, 17 (25), 7069–7079. 10.1002/chem.201003634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X.; Lin J.; Pang M. Facile synthesis of highly uniform Fe-MIL-88B particles. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16 (7), 3565–3568. 10.1021/acs.cgd.6b00313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gandara-Loe J.; Souza B. E.; Missyul A.; Giraldo G.; Tan J.-C.; Silvestre-Albero J. MOF-based polymeric nanocomposite films as potential materials for drug delivery devices in ocular therapeutics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12 (27), 30189–30197. 10.1021/acsami.0c07517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas S.; Colinet I.; Cunha D.; Hidalgo T.; Salles F.; Serre C.; Guillou N.; Horcajada P. Toward understanding drug incorporation and delivery from biocompatible metal–organic frameworks in view of cutaneous administration. ACS omega 2018, 3 (3), 2994–3003. 10.1021/acsomega.8b00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheta S. M.; El-Sheikh S. M.; Abd-Elzaher M. M. Simple synthesis of novel copper metal–organic framework nanoparticles: biosensing and biological applications. Dalton trans. 2018, 47 (14), 4847–4855. 10.1039/C8DT00371H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liédana N.; Lozano P.; Galve A.; Téllez C.; Coronas J. The template role of caffeine in its one-step encapsulation in MOF NH 2-MIL-88B (Fe). J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2 (9), 1144–1151. 10.1039/C3TB21707H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari C.; Mishra A.; Nayak D.; Chakraborty A. Metal organic frameworks modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN): A nano-composite system to inhibit uncontrolled chemotherapeutic drug delivery from bare-msn. J. Drug Delivery Sci. Technol. 2018, 47, 1–11. 10.1016/j.jddst.2018.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bikiaris N. D.; Ainali N. M.; Christodoulou E.; Kostoglou M.; Kehagias T.; Papasouli E.; Koukaras E. N.; Nanaki S. G. Dissolution enhancement and controlled release of paclitaxel drug via a hybrid nanocarrier based on mpeg-pcl amphiphilic copolymer and fe-btc porous metal-organic framework. Nanomaterials 2020, 10 (12), 2490. 10.3390/nano10122490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar P.; Priyatharshni S.; Nagashanmugam K.; Thanigaivelan A.; Kumar K. Chitosan capped nanoscale Fe-MIL-88B-NH2 metal-organic framework as drug carrier material for the pH responsive delivery of doxorubicin. Mater. Res. Express 2017, 4 (8), 085023. 10.1088/2053-1591/aa822f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.-S.; Lin K.-S. Characterization of the size and porous temperature sensitivity of Pluronic F127–Coated MIL–88B (Fe) for drug release. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 328, 111456. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2021.111456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Zhao Y.; Liu D. pH and H2S Dual-Responsive Magnetic Metal–Organic Frameworks for Controlling the Release of 5-Fluorouracil. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4 (9), 7103–7110. 10.1021/acsabm.1c00710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi-Kamazani M.; Zarghami Z.; Salavati-Niasari M. Facile and novel chemical synthesis, characterization, and formation mechanism of copper sulfide (Cu2S, Cu2S/CuS, CuS) nanostructures for increasing the efficiency of solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120 (4), 2096–2108. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b11566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalid S.; Ahmed E.; Malik M. A.; Lewis D. J.; Bakar S. A.; Khan Y.; O’Brien P. Synthesis of pyrite thin films and transition metal doped pyrite thin films by aerosol-assisted chemical vapour deposition. New J. Chem. 2015, 39 (2), 1013–1021. 10.1039/C4NJ01461H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Meng W.; Wang L.; Li L.; Long Y.; Hei Y.; Zhou L.; Wu S.; Zheng Z.; Luo L. Preparation of nano-copper sulfide and its adsorption properties for 17α-ethynyl estradiol. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2020, 15 (1), 48. 10.1186/s11671-020-3274-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siepmann J.; Siepmann F. Mathematical modeling of drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 364 (2), 328–343. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa P.; Lobo J. M. S. Modeling and comparison of dissolution profiles. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001, 13 (2), 123–133. 10.1016/S0928-0987(01)00095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Peng Y.; Xia X.; Cao Z.; Deng Y.; Tang B. Sr/PTA metal organic framework as a drug delivery system for osteoarthritis treatment. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17570. 10.1038/s41598-019-54147-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körber M. PLGA erosion: solubility-or diffusion-controlled?. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27 (11), 2414–2420. 10.1007/s11095-010-0232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sooklert K.; Chattong S.; Manotham K.; Boonwong C.; Klaharn I.-y.; Jindatip D.; Sereemaspun A. Cytoprotective effect of glutaraldehyde erythropoietin on HEK293 kidney cells after silver nanoparticle exposure. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 597. 10.2147/IJN.S95654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C.-J.; Jiang X.-F.; Junaid M.; Ma Y.-B.; Jia P.-P.; Wang H.-B.; Pei D.-S. Graphene oxide nanosheets induce DNA damage and activate the base excision repair (BER) signaling pathway both in vitro and in vivo. Chemosphere 2017, 184, 795–805. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.; Xu H.; Wu Y.; Tang M.; McEwen G. D.; Liu P.; Hansen D. R.; Gilbertson T. A.; Zhou A. Investigation of free fatty acid associated recombinant membrane receptor protein expression in HEK293 cells using Raman spectroscopy, calcium imaging, and atomic force microscopy. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85 (3), 1374–1381. 10.1021/ac3020577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X.; Lu C.; Tang M.; Yang Z.; Jia W.; Ma Y.; Jia P.; Pei D.; Wang H. Nanotoxicity of silver nanoparticles on HEK293T cells: A combined study using biomechanical and biological techniques. ACS omega 2018, 3 (6), 6770–6778. 10.1021/acsomega.8b00608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horcajada P.; Gref R.; Baati T.; Allan P. K.; Maurin G.; Couvreur P.; Ferey G.; Morris R. E.; Serre C. Metal–organic frameworks in biomedicine. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112 (2), 1232–1268. 10.1021/cr200256v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C.-Y.; Qin C.; Wang X.-L.; Yang G.-S.; Shao K.-Z.; Lan Y.-Q.; Su Z.-M.; Huang P.; Wang C.-G.; Wang E.-B. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 as efficient pH-sensitive drug delivery vehicle. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41 (23), 6906–6909. 10.1039/c2dt30357d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.