Abstract

To investigate the interaction between FtsZ and the Min system during cell division of Escherichia coli, we examined the effects of combining a well-known thermosensitive mutation of ftsZ, ftsZ84, with ΔminCDE, a deletion of the entire min locus. Because the Min system is thought to down-regulate Z-ring assembly, the prediction was that removing minCDE might at least partially suppress the thermosensitivity of ftsZ84, which can form colonies below 42°C but not at or above 42°C. Contrary to expectations, the double mutant was significantly more thermosensitive than the ftsZ84 single mutant. When shifted to the new lower nonpermissive temperature, the double mutant formed long filaments mostly devoid of Z rings, suggesting a likely cause of the increased thermosensitivity. Interestingly, even at 22°C, many Z rings were missing in the double mutant, and the rings that were present were predominantly at the cell poles. Of these, a large number were present only at one pole. These cells exhibited a higher than expected incidence of polar divisions, with a bias toward the newest pole. Moreover, some cells exhibited dramatically elongated septa that stained for FtsZ, suggesting that the double mutant is defective in Z-ring disassembly, and providing a possible mechanism for the polar bias. Thermoresistant suppressors of the double mutant arose that had modestly increased levels of FtsZ84. These cells also exhibited elongated septa and, in addition, produced a high frequency of branched cells. A thermoresistant suppressor of the ftsZ84 single mutant also synthesized more FtsZ84 and produced branched cells. The evidence from this study indicates that removing the Min system exposes and exacerbates the inherent defects of the FtsZ84 protein, resulting in clear septation phenotypes even at low growth temperatures. Increasing levels of FtsZ84 can suppress some, but not all, of these phenotypes.

Bacteria such as Escherichia coli normally divide by binary fission, producing two daughter cells of equal size, each containing a nucleoid. The division process starts with the localization of FtsZ to the center of the mother cell and formation of a septal ring structure, the Z ring. Other essential cell division proteins are then recruited to the Z ring, and the ring contracts as the ingrowing septum invaginates. Once the septum is fully formed, the Z ring disappears and the daughter cells separate. Little is known about what regulates Z-ring assembly, contraction, and disassembly.

FtsZ is essential for cell division and viability. Deletion or mutation of the ftsZ gene blocks cell division at an early stage, causing the formation of long filamentous cells with multiple nucleoids. The thermosensitive ftsZ84 mutant grows normally at 28°C but becomes filamentous at higher temperatures and fails to form colonies at 42°C. This mutant has been particularly well-studied because it encodes a protein with an amino acid change in a domain implicated in GTP binding. This domain is highly conserved among FtsZ proteins throughout prokaryotes and organelles and is also conserved among eukaryotic tubulins (19, 23). As expected, purified FtsZ84 protein has reduced GTP binding, hydrolysis, and polymerization activity (8, 30). The lethal phenotype of the ftsZ84 mutant at 42°C can be suppressed by (i) complementation by the wild-type FtsZ, indicating that the mutation is recessive; (ii) increasing levels of FtsZ84 itself, by expressing it ectopically or by increasing the NaCl concentration, which appears to increase transcription of the ftsZ gene via ppGpp effects (24, 25); and (iii) moderate overexpression of another essential cell division protein, ZipA, which appears to stabilize FtsZ polymers in vivo and in vitro (29). These results indicate that lower temperatures, increased concentrations of the defective FtsZ84 protein itself, or increased concentrations of ZipA are sufficient to overcome the GTP binding defect, allowing a functional Z ring to polymerize.

The Min system is an important regulator of FtsZ assembly and Z-ring positioning in E. coli. Encoded by a three-gene operon, MinC and MinD together act as an FtsZ inhibitor, while MinE acts to suppress MinCD-mediated inhibition only at the central division site (9, 10) MinE therefore confers topological specificity upon the MinCD inhibitor. Deletion of minCD or overexpression of minE leads to polar division and produces anucleate minicells, while moderate overexpression of minCD, high-level overexpression of minC, or deletion of minE inhibits cell division at all potential sites and results in filament formation (7, 9, 10). Recent results have shed new light on how the Min system might regulate Z-ring positioning. First, MinE forms a ring near midcell independent of FtsZ (26); this could explain how MinE can counteract the MinCD inhibitor at the division site, allowing the medial Z ring to form. Second, when the Min system is eliminated by deletion, seemingly random clusters of Z rings form in all nucleoid-free regions of the cell but rarely on top of nucleoids, suggesting that (i) the nucleoid inhibits ring formation and (ii) MinCD normally inhibits ring formation throughout the cell except where the inhibition has been suppressed by MinE (41). Third, MinD and MinC oscillate rapidly together between the two cell poles, consistent with the idea that MinCD inhibits FtsZ throughout the cell (13, 27, 28). The isolation of an FtsZ allele which resists MinCD inhibition suggests that FtsZ is the direct target of MinCD inhibition (5), although no interaction between FtsZ and MinC or MinD has been detected in yeast two-hybrid assays (15). Recently, high levels of purified MinC were shown to inhibit FtsZ polymerization in vitro (14), suggesting that a direct interaction between MinC and FtsZ occurs in the cell. In vivo, MinCD-mediated inhibition can be overcome by a severalfold increase in the levels of FtsZ and another key cell division protein, FtsA, which leads to polar division and minicell production (4, 38). This Min− phenocopy is presumably caused by titration of the MinCD inhibitor by the higher levels of FtsZ and FtsA. Despite these advances, it is not yet clear how MinC inhibits polymerization, nor how MinD helps MinC inhibit Z rings in vivo.

To understand more about how the Min proteins and FtsZ interact, we chose to investigate how the activity of the defective FtsZ84 protein might be affected by removing the Min system. The promiscuity of Z-ring formation in ΔminCDE mutants and the ability of MinC to inhibit FtsZ polymer assembly suggested that FtsZ84 might be more active in the absence of the Min proteins. In this paper, we describe the phenotype of an ftsZ84 ΔminCDE double mutant and report several unexpected findings. Instead of suppressing the thermosensitivity of the ftsZ84 mutant, deletion of the Min system made the thermosensitive phenotype more severe. This phenotype correlated with a scarcity of Z rings and could be suppressed by higher levels of FtsZ84. Interestingly, FtsZ84 rings appeared to have a novel defect in disassembly and were strongly biased toward polar localization at the permissive temperature. A model to explain these findings is presented.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth media.

All strains were derivatives of the wild-type E. coli strain MG1655. TX3772 is an MG1655 derivative that contains ΔlacU169 (37). LB (Luria-Bertani) medium (31) containing 0.5% NaCl was used for most experiments. In cases where more stringent conditions for ftsZ84 were desired, LBNS (LB with no added NaCl) medium was used. Minimal glucose medium for TX3772 derivatives contained M9 salts supplemented with 0.2% glucose (31).

Construction of mutant strains.

To construct the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant in the wild-type MG1655 background, an ftsZ84 allele linked to a leu::Tn10 marker from EC488 (39) was first transduced into the MG1655 derivative TX3772 at 32°C with phage P1. Tetr transductants were screened for thermosensitivity at 42°C, and one such transductant was purified and designated WM1109. To remove the Tetr marker in order to facilitate future strain constructions, WM1109 was transduced to leucine prototrophy by selection for colony growth on minimal glucose, and leu+ Tets transductants were then screened for thermosensitivity. One purified transductant, WM1125, exhibited a phenotype typical of an ftsZ84 mutant, growing normally at 32°C but forming filaments at 42°C. The presence of the ftsZ84 allele in WM1125 was further confirmed by PCR sequence analysis. The ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant was then constructed by transducing a ΔminB::kan allele from PB114 in which the entire minCDE operon was deleted and replaced with a Kanr cassette (10) into strain WM1125 to make WM1147. WM947 is a derivative of MG1655 that also contains the same ΔminB::kan marker (41).

Thermoresistant suppressors were isolated from WM1125 and WM1147 by selecting for colonies on LB plates at 42 and 37°C, respectively, and were named WM1175 and WM1151, respectively.

Indirect immunofluorescence staining.

Cell fixation, immunofluorescence staining, staining of nucleoids with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), phase-contrast microscopy, and fluorescence microscopy were performed as described previously (36, 42). Secondary antibodies conjugated to the green fluorophore Alexa 488 were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oreg.). Images were captured with a DEI-750 RGB color video camera and framegrabber (Optronics Engineering, Goleta, Calif.) and manipulated with Adobe Photoshop. As previously described, the blue and red channels of the RGB output from the camera were swapped in order to have the blue DAPI stain appear red for greater contrast. For time-lapse growth of cells on agar-coated microscope slides, cells were treated essentially as described previously (35).

Quantitation of FtsZ protein levels.

The level of FtsZ in different strains under different conditions was measured by immunoblotting. First, cells were grown in LB medium at different temperatures and harvested by centrifugation. Cell pellets were resuspended in 100 to 200 μl of 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and incubated at 100°C for 10 min. Ten microliters of this sample was diluted into 200 μl of distilled H2O, and the total protein concentration of the cell lysate was measured by the bicinchoninic acid assay (32) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard. SDS was added to the BSA standard to ensure all samples contained the same concentration of SDS. The proteins in the samples were then separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with affinity-purified polyclonal anti-FtsZ antibody at a 1:2,000 dilution. Blots were then incubated with goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to peroxidase (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), and antibody binding was detected by chemiluminescence. The resulting bands on X-ray films were scanned, and their intensities were quantitated with NIH Image 1.60.

RESULTS

Synthetic thermosensitive phenotype of a ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant.

To test the hypothesis that a min deletion might partially suppress the thermosensitive phenotype of an ftsZ84 mutant, a ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant was constructed by sequential P1 transduction (WM1147). We examined the ability of WM1147 to form colonies at different temperatures on LB agar. Surprisingly, this strain was significantly more thermosensitive than WM1125, its min+ ftsZ84 parent. WM1125 could form colonies at all temperatures tested below 42°C, although at 37°C the colonies contained a mixture of filaments and short cells (Table 1). In contrast, WM1147 could form colonies only at 22°C and 28 but not at 32°C or above (Table 1 and data not shown). Expression of wild-type FtsZ from a plasmid in WM1147 allowed growth at all temperatures (data not shown), indicating that no additional mutations other than ftsZ84 and ΔminCDE were responsible for the synthetic phenotype. These results suggest that removal of the MinCD division inhibitor, along with the topological specificity factor MinE, further exacerbates the ftsZ84 defects. This is contrary to the predicted suppression of ftsZ84 by removal of the MinCD inhibitor.

TABLE 1.

Ability of ftsZ84, ΔminCDE, and ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant strains to form colonies on LB agar at different growth temperatures

| Strain | Colony formation ata:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22°C | 32°C | 37°C | 42°C | |

| TX3772 (wild-type) | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| WM1125 (ftsZ84) | +++ | +++ | ++ | − |

| WM1147 (ΔminCDE ftsZ84) | +++ | − | − | − |

| WM1151 (ΔminCDE ftsZ84*)b | +++ | +++ | ++ | − |

| WM1175 (ftsZ84*) | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

+++, plating efficiency and colony size similar to those at 22°C; ++, reduced plating efficiency, smaller colony size, and longer cells as compared to 22°C; −, no colonies.

*, thermoresistant suppressor of ftsZ84.

Many Z rings are missing in the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant.

Why would deleting minCDE make the ftsZ84 mutant more thermosensitive? One hypothesis is that the removal of MinCD inhibition also uncovers more sites at which FtsZ protein can localize, which might reduce the protein concentration at the normal potential division site. The increase in such sites in ΔminCDE cells does not prevent wild-type FtsZ from promiscuously forming clusters of Z rings at most of these sites (41). However, the low GTP-binding activity of FtsZ84 should result in a higher critical concentration for assembly. If a critical local protein concentration is necessary for multimerization and nucleation of the Z ring, the availability of more potential sites might dilute the FtsZ84 protein to a point where little nucleation could occur. This should be manifested by a scarcity of Z rings, even in nucleoid-free regions normally able to support promiscuous ring formation by the wild-type protein.

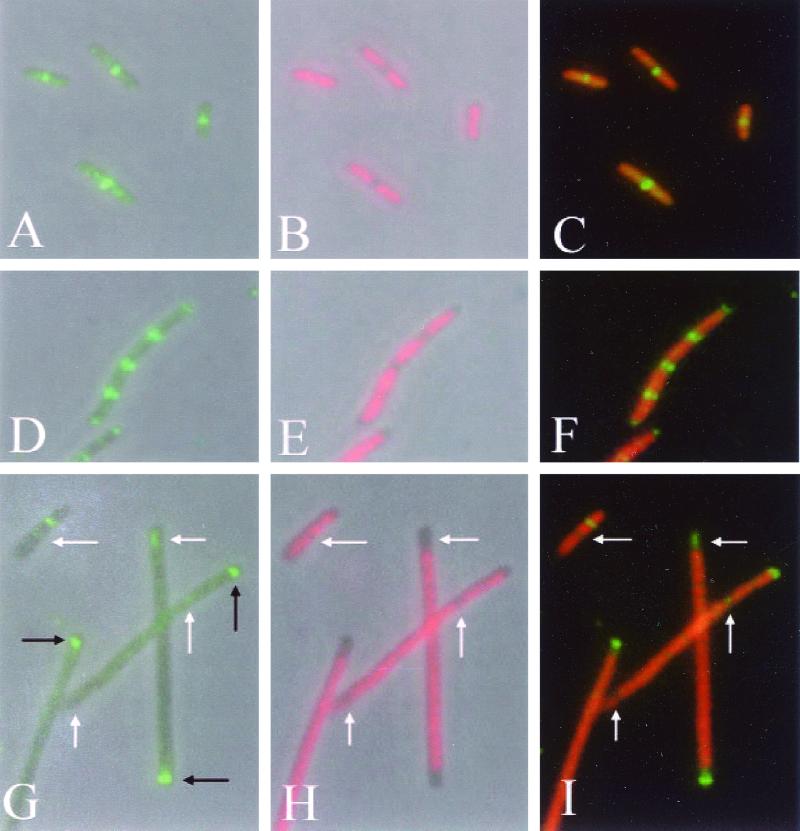

To test this hypothesis, we examined FtsZ localization in the double mutant strain WM1147 by immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM) and compared this localization to that in the single mutants. In the min+ ftsZ84 mutant (WM1125), FtsZ84 formed a central ring in most cells grown at the permissive temperature, in this case 22°C (Fig. 1A to C). In the ftsZ+ ΔminCDE mutant, Z rings were present in all nucleoid-free regions of the cell including the poles (Fig. 1D to F), as observed previously (41). However, in the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant, Z rings were notably absent at many potential division sites between nucleoids (Fig. 1G to I). This occurred even at 22°C, a permissive temperature for colony formation.

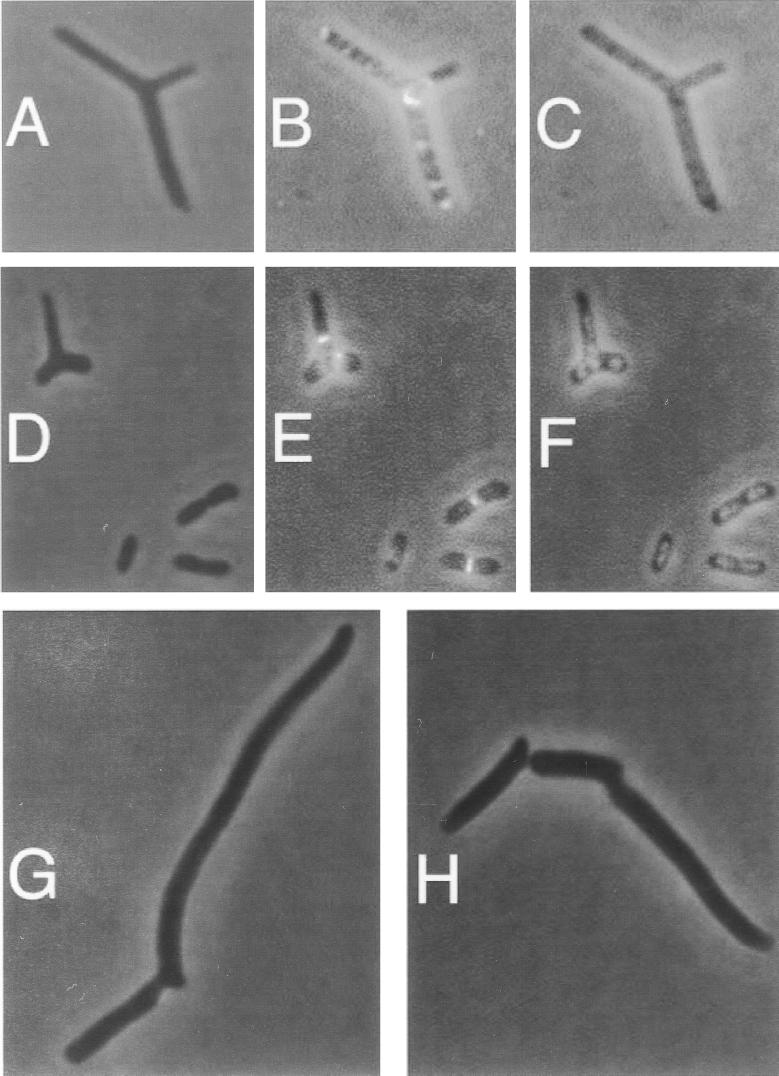

FIG. 1.

Localization of FtsZ in ftsZ84, ΔminCDE, and ΔminCDE ftsZ84 mutants. Cells were grown by shaking in LB broth at 22°C to mid-exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm of approximately 0.2). Ten microliters of cells was loaded onto a 12-mm coverslip precoated with polylysine, fixed, and incubated with affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-FtsZ antibody (1:500 dilution). The samples were subsequently incubated with Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (green) and 1 μg of DAPI per ml (pseudocolored red). (A to C) Strain WM1125 (ftsZ84); (D to F) strain WM947 (ΔminCDE); (G to I) strain WM1147 (ΔminCDE ftsZ84). (A, D, and G): FtsZ staining; (B, E, and H): DAPI staining; (C, F, and I): overlay of FtsZ and DAPI images. White arrows in panels G to I highlight apparent gaps between nucleoids; black arrows highlight polar FtsZ rings.

We next investigated the effects of raising the temperature to the nonpermissive range. Although the WM1147 double mutant could not form colonies on LB agar at 37°C, it could be grown in LB broth at 37°C after prior growth at 22°C. At least 90% of the long filaments generated after several generations at 37°C were devoid of Z rings, as detected by IFM. However, a minority of filaments contained clear Z rings and often had multiple rings per filament. It is not clear if the latter class of filaments represents an adaptation/suppression phenomenon (see below) or if some filaments were somehow better predisposed to form rings prior to the temperature induction.

In the few WM1147 filaments containing Z rings, we measured the overall cell length per ring to be 22.8 μm. This compares with average lengths per ring in the ftsZ84 mutant, wild-type, and ΔminCDE mutant of 6.8, 3.1, and 1.8 μm, respectively, at 37°C. The higher frequency of Z rings per cell length in a ΔminCDE mutant relative to the wild type has been described previously (41). The data indicate that the ring density drops significantly in the ftsZ84 mutant grown at 37°C and becomes much lower in the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant WM1147. It should be emphasized that the 22.8-μm cell length per ring pertains to the 10% of WM1147 cells with rings; the estimated cell length per ring in the overall WM1147 population grown at at 37°C is at least 100 μm.

FtsZ84 protein levels in the double mutant.

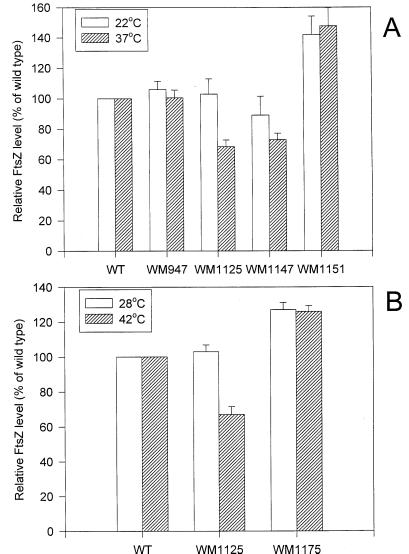

To rule out the possibility that the decreased number of Z rings in the double mutant was caused by a significant decrease in FtsZ levels, we measured the total levels of FtsZ in the wild type and single and double mutants by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 2A, at 37°C, the level of FtsZ in the ftsZ84 mutant WM1125 and the double mutant WM1147 is about 70% of that in wild-type cells, while the level of FtsZ in the min mutant WM947 is essentially the same as in the wild type. This indicates that the FtsZ84 protein may be itself somewhat thermolabile in vivo, which might contribute to the increased thermosensitivity of strains containing the ftsZ84 allele. At 22°C, on the other hand, the levels of FtsZ in the above mutants are between 90 and 100% of the wild-type values. Because FtsZ84 levels in the min+ and ΔminCDE mutants are essentially the same at both 22 and 37°C, it is unlikely that the increased thermosensitivity and drastically lower ring frequency in the ΔminCDE mutant results from differences in FtsZ levels. Instead, we favor the idea that the absence of min exposes existing defects of FtsZ84, as discussed below.

FIG. 2.

FtsZ protein levels in the wild-type, ftsZ84, ΔminCDE, ΔminCDE ftsZ84, and ΔminCDE ftsZ84 thermoresistant suppressor strains at different temperatures. Quantitation of FtsZ by immunoblotting with anti-FtsZ antibody was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The FtsZ level in wild-type (TX3772) cells was arbitrarily assigned a value of 100% (y axis). All values are the averages from three independent experiments. (A) Comparison of FtsZ levels in the different mutants at 22 and 37°C; (B) comparison at 28 and 42°C.

Preferential polar localization and activity of Z rings in the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant.

In short cells with newly segregated nucleoids, the absence of the Min system should result in three possible regions in which Z rings can form: the two polar sites and the midcell (nonpolar) site. Assuming that rings can form at these sites with equal probability, the theoretical ratio of polar to nonpolar (internal) Z rings in short ΔminCDE cells should be 2:1 (35). However, in reality, many ΔminCDE cells are multinucleate filaments because polar divisions occur at the expense of midcell divisions. Therefore, the ratio of polar to nonpolar rings is often less than 1:1 (41). The deficiency of Z rings in the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant results in filaments that are significantly longer than those in a ΔminCDE ftsZ+ mutant. As a result, the expected polar/nonpolar ratio should be lower still, given the large number of potential division sites predicted to exist within the long filaments compared to the fixed number of two polar sites.

After characterizing the positioning of the Z rings in the double mutant at the permissive temperature of 22°C, we were surprised to find that the few Z rings that were present were localized predominantly at the cell poles (within 1 μm of the pole). In 111 cells examined, 93 cells contained one or two polar Z rings each, and the total number of polar rings was calculated to be 111. However, only 23 of these 111 cells had one or two nonpolar rings, with a total number of 24 nonpolar rings (see Fig. 1G to I and Table 2). This resulted in a strikingly high polar/nonpolar ring ratio of 4.58. In contrast, in the single ΔminCDE mutant grown at 22°C, we counted 110 rings in a typical cell sample; of these, 70 were nonpolar and 40 were polar, giving a polar/nonpolar ring ratio of 0.57 (Table 2). Polar rings were never observed in the single ftsZ84 mutant at the permissive temperature. These results indicate that the polar bias of Z-ring localization in the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant was significantly greater than that in the single ΔminCDE mutant and must therefore be favored in some way by the presence of the ftsZ84 mutation.

TABLE 2.

Polar Z-ring positioning bias in different mutants

| Strain | % Polar ringsc | % Nonpolar ringsc | Polar/nonpolar ring ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| TX3772 (wild-type)a | 0 | 100 | 0.00 |

| WM947 (ΔminCDE)a | 36 | 64 | 0.57 |

| WM1125 (ftsZ84)a | 0 | 100 | 0.00 |

| WM1147 (ΔminCDE ftsZ84)a | 82 | 18 | 4.58 |

| WM1151 (ΔminCDE ftsZ84*)b | 61 | 39 | 1.56 |

Measured with cells grown at 22°C.

Measured with cells grown at 37°C.

Percentages were calculated from sampling at least 100 cells. Polar rings were defined as rings within 1 μm of the pole which were not separated from the pole by a nucleoid.

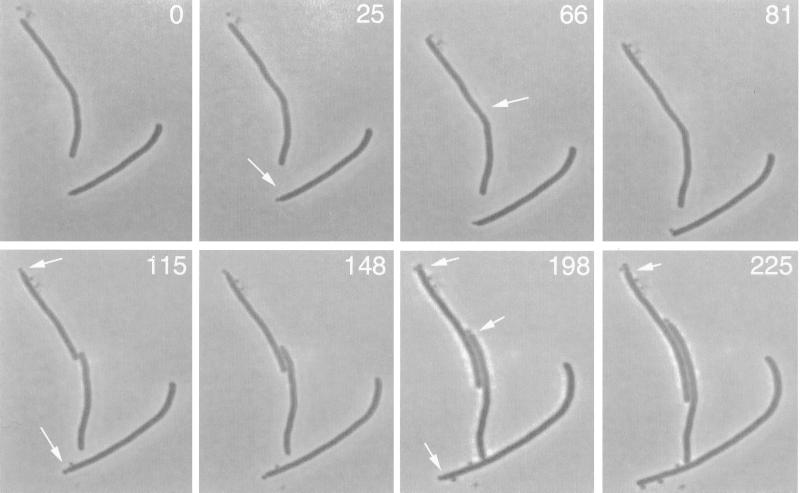

To test whether the polar rings in the double mutant were active in cell division, we monitored cells growing on a thin layer of LB agar on glass slides at 22°C by phase-contrast microscopy. One example of several such experiments is shown in Fig. 3. Growth and division of two short filaments were followed over a course of 225 min. During this time, we could clearly observe seven polar division events (see arrows) but only one nonpolar division event (see arrow in the 66-min panel). As a result, three short filaments and seven minicells were formed over the 225-min time frame. This result and others from similar experiments (data not shown) are consistent with the IFM evidence for preferential localization of Z rings at the cell poles in the double mutant and strongly suggest that these polar Z rings are functional for division.

FIG. 3.

Time-lapse monitoring of the polar bias of cell division during growth of individual ΔminCDE ftsZ84 cells on agar. Strain WM1147 (ΔminCDE ftsZ84) was grown at 22°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.1 to 0.2. Then 5 μl of the cell culture was loaded onto a thin layer of LB agar on a glass slide and grown for several hours at approximately 22°C under a cover glass for time-lapse photomicrography. A 100× oil immersion phase-contrast objective was used to capture the images of the cells at the times indicated (in minutes). Each arrow highlights a division event. The arrow in the 66-min panel highlights initiation of a nonpolar septum. The other seven arrows highlight polar division events leading to the formation of minicells.

Consecutive division events at the new pole.

In addition to the polar preference for division events, the time-lapse data in Fig. 3 reveal that the polar divisions appear to occur sequentially at one pole, suggesting that one pole is more active than the other for cell division. For example, three minicells each were produced from one pole of the two original filaments in Fig. 3, while the other poles remained quiescent over the period of the experiment. The seventh minicell became visible at the 198- and 225-min time points (see middle arrow in 198-min panel), and this minicell was formed near the pole most recently formed by the nonpolar division of the filament.

One explanation for this result is that in the double mutant, poles generated by the most recent cell division events (new poles) are the most active for Z-ring assembly and cell division, whereas potential division sites at nonpolar sites and old poles are much less active. If this hypothesis is correct, then nonpolar sites should be no more active than sites at old poles and Z rings should form at nonpolar sites and at old poles with equal probability. Because the long filaments of the double mutant contain many more potential division sites between nucleoids than polar sites, it follows that cells containing two polar rings should occur much less frequently than cells with one polar ring or with nonpolar rings. Data from additional time-lapse experiments strongly supported this idea. Of a total of 36 cell division events that could be unambiguously attributed to a new or old pole based on prior division, 3 occurred at an old pole, 26 occurred at a new pole, and 7 were nonpolar. This high percentage of division events at new poles suggests that new poles are by far the most active regions for cell division in the double mutant.

Further examination of the polar ring distribution indicated that among the 111 cells counted previously, 72 cells contained one polar ring, 21 cells contained two polar rings, and 23 cells had one or more nonpolar rings. The number of cells with two polar rings is clearly lower than that with just one polar ring, which is consistent with our hypothesis. However, the number of cells with nonpolar rings is surprisingly low given the number of nonpolar potential division sites expected within these filaments. A closer examination of nucleoid staining in the double mutant (Fig. 1G to I) indicates that many nucleoids are not properly segregated at the permissive temperature for colony formation by the ftsZ84 mutant. Such segregation problems have been noted previously in min mutants (2, 21) and in ftsZ mutants (16, 34). Our recently proposed integrated model for positioning of cell division sites (41) predicts that the presence of large unpartitioned chromosomes within the double mutant filaments might prevent Z-ring formation by nucleoid occlusion effects, except at nucleoid-free areas at the cell poles. This would result in a bias towards formation of rings at polar sites. As can be seen in Fig. 1G to I, the cell poles in these mutants are often nucleoid-free and such regions contain Z rings.

It should be emphasized, however, that many nucleoids are well-segregated in cells of the double mutant (Fig. 1H and I, arrows). The resulting nucleoid-free spaces remain mostly devoid of Z rings (Fig. 1G to I, arrows, and data not shown), indicating that segregation problems cannot be the sole cause of the polar bias of Z-ring positioning. Furthermore, large nucleoid-free areas are present at both poles in many of these filaments, which is a typical Min− phenotype (2, 41), yet the majority of these cells have a single Z ring at only one pole (see also Fig. 1G to I). This suggests that the bias towards localization at a single pole is not because nucleoids block the other pole. This evidence supports our idea that rings have a preference for one pole, probably the new pole, in these short filaments.

Elongated septa and persistence of FtsZ84 at newly formed poles.

We have presented evidence for preferential Z-ring assembly at new poles over other potential division sites in the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant. Wild-type FtsZ does not have any obvious polar preference in a ΔminCDE mutant (Fig. 1D to F); instead, Z rings are formed at all nucleoid-free gaps (41). Therefore, we hypothesize that the polar bias in the double mutant stems from defects inherent in the FtsZ84 protein. The major known defects of FtsZ84 are its much lower GTP binding and hydrolysis activities as compared to the wild-type protein. The GTP binding defect correlates with lower activity in self-assembly (29), and it is likely that the GTPase defect inhibits polymer turnover, which is dependent on GTP hydrolysis (20). Because ftsZ84 mutants survive at temperatures below 42°C, these defects obviously do not compromise the ability of FtsZ84 to divide cells at these temperatures in the presence of the Min system. As we have shown, the absence of the Min system enhances the defective effects of the FtsZ84 protein. The most obvious effects are the reduced ability to form stable Z rings at a given temperature, probably as a result of the low GTP binding activity of FtsZ84. However, the other predicted defect in polymer turnover, caused by reduced GTP hydrolysis, might be manifested in vivo by a delay in the constriction and/or disassembly of existing rings.

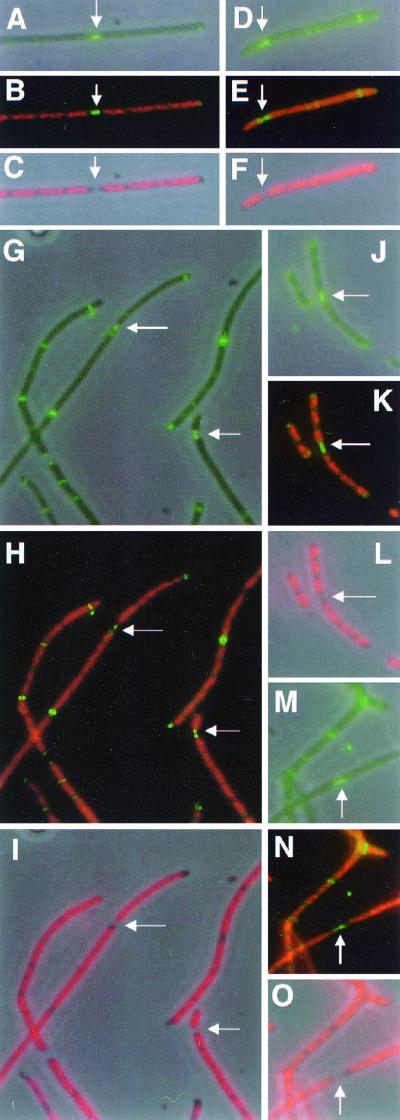

To address this possibility, we examined cells of the double mutant for evidence of defective septum disassembly. In many cases, we found that the septum was dramatically elongated when the two daughter cells were at the last stage of separation (Fig. 4A to C). In this strain (data not shown) and a derivative of this strain (Fig. 4D to O, see below), the FtsZ septal ring structure often appeared to be duplicated, with foci at each newly formed daughter cell pole (arrows). This phenomenon is never observed in cells containing wild-type FtsZ, presumably because wild-type Z rings have normal GTPase activity and can disassemble rapidly upon septation (35). In a min+ ftsZ84 strain, rings also appear to disassemble rapidly upon thermoinduction (1), and we have only rarely observed the elongated septum phenotype in this strain background (data not shown). We conclude that the absence of the Min system exacerbates both the assembly defect of FtsZ84 and the apparent disassembly defect of FtsZ84 as evidenced by these unusually persistent septal structures.

FIG. 4.

Persistence of FtsZ staining at elongated septa in the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant and its thermoresistant derivative. Cells were treated as described in the legend to Fig. 1. (A to C) Strain WM1147 grown at 22°C; (D to O) strain WM1151 grown at 37°C. Three images were taken of each field of cells: FtsZ, FtsZ plus DAPI overlay, and DAPI only. These appear as the top, middle, and bottom images within each set of three. Panels A to C and J to L each show a filament with an elongated central septum with FtsZ staining (arrows). Panels D to F, G to I, and M to O show cases of apparent bisection of FtsZ staining by an elongated septum to yield two separate FtsZ foci at the newly formed poles (arrows).

Suppression of the thermosensitivity of the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant by increased FtsZ84 levels.

When cells of strain WM1147 were plated on LB agar and grown at the nonpermissive temperatures of 37°C or higher, surviving colonies arose at frequencies as high as 10−4. To investigate the mechanism behind this suppression, we characterized one thermoresistant strain (WM1151). Although this strain formed colonies at 37°C on LB agar, it grew very poorly at 42°C on LB agar. Like its parent WM1147, WM1151 did not form colonies on LBNS agar plates at 37°C, which is a more stringent test of thermosensitivity of the ftsZ84 mutation than growth on LB agar because the lack of NaCl causes reduced expression of ftsZ (25). Both of these results indicated that the thermoresistant phenotype was not a result of a simple reversion of the original point mutation in ftsZ84 back to the wild type.

To determine if the thermoresistance of WM1151 correlated with an increase in Z-ring frequency, we examined Z rings in cells grown at 37°C by IFM. As shown in Fig. 4D to O, most cells contained polar and nonpolar rings. The frequency of Z rings, while still below wild-type levels, was much higher than that in WM1147 at this temperature, with an average cell length per ring of 5.7 μm. Of 117 rings counted, 46 (39%) were nonpolar, which is approximately twice the frequency of nonpolar rings in WM1147 grown at its permissive temperature of 22°C (Table 2). Nevertheless, the ratio of polar to nonpolar rings is still significantly higher than that in the ΔminCDE single mutant. These results indicate that WM1151 has properties midway between the single mutants and the WM1147 double mutant parent.

We next determined, by immunoblotting, whether the increased frequency of Z rings in WM1151 correlated with increased levels of FtsZ. As shown in Fig. 2A, FtsZ levels in WM1151 were 40 to 50% higher than in wild-type cells and about twofold higher than in the WM1147 double mutant or the ftsZ84 single mutant (WM1125) at 37°C, the nonpermissive temperature for the double mutant. The high frequency of thermoresistant suppressors, combined with the higher FtsZ levels in the suppressor strain WM1151, suggest that these modestly increased levels of FtsZ84 may be sufficient to promote assembly of more nonpolar rings and to suppress the thermosensitivity of the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant.

Abnormal septal morphology and cellular branching in the strain with higher FtsZ84 levels.

Despite the higher Z-ring frequency in WM1151 relative to the double mutant parent, WM1147, WM1151 cells, like those of WM1147, often contained Z rings that appeared to be defective in disassembly. FtsZ staining was often found in dramatically elongated septa (Fig. 4G to L, arrows). As in WM1147, the FtsZ staining pattern was often bisected. This resulted in the appearance of two clear FtsZ foci, one at each of the two new poles that were juxtaposed (Fig. 4E, H, and K, arrows). The morphology of these foci suggested that they were no longer Z rings, but rather more amorphous aggregates of FtsZ.

When grown at 37°C for more than 5 h, strain WM1151 routinely produced branched cells at a high frequency (Fig. 5A to C). The frequency ranged from 2 to 10%, depending on the temperature and how long the cells were cultured. It was previously reported that min mutants can form branched cells at similarly high frequencies, but branching depended on specific strain backgrounds and specialized defined slow-growth media (3). In the case described herein, branching occurs in an otherwise wild-type strain background in standard rich LB medium.

FIG. 5.

Branched cells and abnormal septal morphology in the thermoresistant derivatives of ftsZ84 or the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant. Strains WM1151 (thermoresistant ΔminCDE ftsZ84) (A to C) and WM1175 (thermoresistant ftsZ84) (D to F) were grown at 37 and 42°C, respectively, for 5 h to mid-exponential phase. Cells were then fixed and stained with anti-FtsZ/Alexa 488 to visualize Z rings (B and E) and DAPI to visualize nucleoids (C and F) as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Phase-contrast images of the fixed cells are shown in panels A and D. To visualize asymmetric constriction in live cells of a thermoresistant ftsZ84 mutant, strain WM1175 was grown in LB broth at 42°C for 6 h, and 5 μl of culture was loaded onto a glass slide and covered with a cover glass. (G and H) Phase-contrast images were taken at 1/60 sec with a video camera. Unseparated cells and filaments moving and tumbling together were easily distinguished from separated cells.

To examine whether branching of WM1151 cells was dependent on the ΔminCDE mutation, the ftsZ84 mutation, or the increased levels of FtsZ84 protein, we decided to go back and isolate thermoresistant suppressors of an ftsZ84 single mutant to determine if they also generated large numbers of branched cells. Such suppressors arose at high frequency at 42°C, similar to those of WM1147, and one was chosen and designated strain WM1175. This thermoresistant strain formed colonies at 42°C on LB agar but did not form colonies on LBNS, consistent with it not being a reversion of the original ftsZ84 mutant. Sequence analysis confirmed that the original ftsZ84 mutation but no other mutations were present within the ftsZ gene. When grown at 42°C for more than 5 h, many cells of WM1175 formed branches and exhibited elongated septa similar to those produced by strain WM1151 grown at 37°C. Examples of such cells are shown in Fig. 5D to F. In addition, WM1175 often formed abnormal, asymmetric septa that appeared to be precursors of branches (Fig. 5G and H). Z-ring placement appeared between segregated nucleoids in the branched cells and did not correlate with any particular location with respect to the branch points (Fig. 5B to C and E to F and data not shown).

These results suggest that altered expression of the ftsZ84 allele is necessary to promote high-frequency branching in an otherwise wild-type strain and that the ΔminCDE deletion is not necessary for this effect. It follows that the modest increase in FtsZ84 levels in WM1151 may be the major factor responsible for branching. To test this idea, we investigated whether the thermoresistant suppressor in WM1175 also correlated with increased levels of FtsZ84 protein. Quantitative immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2B) indeed showed that at 42°C, the level of FtsZ84 in WM1175 was about 20% higher than the normal level of FtsZ in wild-type cells and almost twofold higher than the level of FtsZ84 in WM1125 (ftsZ84) cells. The FtsZ levels in WM1175 at 28°C were equivalent to the levels at 42°C, suggesting that the increase in FtsZ expression is constitutive. These results suggest that thermoresistant suppression of the ftsZ84 single mutant, as with the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant, is caused by a modest increase in FtsZ84 levels and that such an increase in the defective protein results in the formation of branches in a large number of cells. Increases of wild-type FtsZ of this magnitude have not been reported to yield branched cells.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that removing the Min system increases the thermosensitivity of an ftsZ84 mutant, which encodes a defective FtsZ with lower GTP binding and hydrolysis activities. This synthetic effect was unexpected, because Z rings form highly efficiently in a ΔminCDE strain and it was predicted that in the absence of the MinCD inhibitor, FtsZ84 might be able to nucleate Z rings at a lower critical concentration. However, deleting minCDE appears to have the opposite effect. While the single ftsZ84 mutant forms colonies on LB agar at all temperatures below 42°C, the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant cannot form colonies at or above 32°C. Cells of the double mutant, even at 22°C, are filamentous and contain numerous potential division sites, defined as nucleoid-free gaps, with no Z rings.

Why is FtsZ84 worse at forming Z rings in the absence of the Min system? Immunoblotting analysis indicated that the levels of FtsZ84, while somewhat lower than levels of FtsZ in a wild-type strain, are no different with or without MinCDE. This rules out the possibility that the lack of Z rings in the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant is simply a result of significantly lowered FtsZ84 levels. While several alternative models are possible, we favor the following model to explain the synthetic effect. The first assumption of the model is that FtsZ84 is defective in forming Z rings because it requires a higher critical concentration, relative to wild-type FtsZ, to assemble into the putative polymers that make up the rings. This might explain why a small increase in FtsZ84 concentration can suppress thermosensitivity. The second assumption is that in a normal min+ cell, the nucleoid and the Min system block most of the cell surface from assembling Z rings (41). According to this model, only the midcell region can support Z-ring assembly because (i) the MinE ring counteracts the inhibition of FtsZ by MinCD elsewhere in the cell, such as the nucleoid-free cell poles, and (ii) initiation of chromosome segregation or some other effect of replication causes the nucleoid occlusion effect to be suppressed at the midpoint of the two chromosome masses, which corresponds to the exact center of the cell.

When the Min proteins are absent, the nucleoid-free poles now become potential sites for Z-ring assembly, increasing the overall number of potential assembly sites per cell length. This increased availability of sites causes FtsZ to distribute to more regions of the cell, effectively decreasing its local concentration at any given potential division site. Wild-type FtsZ responds to the lack of Min proteins by forming rings at all of these sites; this can be explained as its estimated concentration of 10 μM is at least five times higher than the critical concentration for GTP-mediated polymer assembly in vitro (18, 20, 40). Therefore, wild-type FtsZ is not limiting for the formation of rings under these conditions. However, FtsZ84 is not only slightly less concentrated, as found by our immunoblot analysis, but also requires a higher critical concentration for assembly than wild-type FtsZ because of its GTP binding defect. We postulate that the dilution effect caused by the increased number of potential assembly sites results in the general failure of FtsZ84 to form rings in the ΔminCDE mutant and that modestly increasing FtsZ84 concentration increases the number of Z rings proportionately. The model predicts that if nucleoid-free gaps were lengthened, for example in a DNA replication mutant, then FtsZ84 would be even less able to form rings and a greater increase in FtsZ84 levels would be necessary for viability.

The defect of FtsZ84 in GTP binding can explain the lower frequency of Z rings in the double mutant according to the above model. The other known defect of FtsZ84, besides GTP binding, is in GTP hydrolysis, and this defect also can explain some of the phenotypes we observe. GTP hydrolysis appears to drive FtsZ polymer disassembly in vitro (20). Our results indicate that in vivo, Z-ring disassembly is indeed defective in an ftsZ84 mutant and is observed most readily in the absence of the Min system.

A related and surprising result of our study is that the majority of Z rings within the short filaments of the ΔminCDE ftsZ84 double mutant at 22°C are located at the cell poles. Polar rings are expected in a min mutant and form in addition to medial rings in short cells (41). But the length of the double mutant filaments, largely resulting from the scarcity of prior septation events, means that many nucleoid-free gaps are present within the filaments that should be sites for Z-ring assembly. Nevertheless, most of these internal sites are not used, and instead most Z rings form at a pole. This implies that the pole has a special ability to attract FtsZ84 in the absence of the Min system.

We can come up with two explanations for this polar bias. One is that nucleoid segregation in the double mutant is abnormal, with many filaments containing unsegregated nucleoids. Nucleoid occlusion would theoretically block Z rings from forming throughout most of the cell except at nucleoid-free areas at the poles. We often saw unsegregated nucleoids in these filaments by DAPI staining, consistent with previous reports linking segregation defects with defects in the Min system (2, 21, 41). FtsZ-dependent late cell division proteins, which would not be localized in the absence of Z rings, have also been implicated in segregation (16, 17, 33, 43). However, most filaments of the double mutant, while displaying some segregation defects, still contain multiple gaps between nucleoids as visualized by DAPI staining. The absence of Z rings in virtually all of these gaps suggests a second hypothesis, which we favor: FtsZ84 is actively recruited to form rings near the most recently formed pole. This idea is entirely consistent with (i) the prevalence of cells with a Z ring at only one pole of a short filament, (ii) our time-lapse data showing sequential minicell formation from one pole at the expense of the rest of the cell, including the opposite pole, and (iii) the duplication of FtsZ84 staining upon formation of two new poles, a result of delayed clearance of FtsZ84 from the newly formed septum.

Overall, our results are consistent with the following general model: (i) FtsZ84 protein is defective in assembling into rings and disassembling once the septum is formed; (ii) both of these defects are significantly enhanced in the absence of the Min system, resulting in increased thermosensitivity of the strain, many missing Z rings, and the persistence of FtsZ structures at new poles; and (iii) incompletely disassembled FtsZ84 structures at new poles remaining from the prior division event serve to nucleate new Z rings, resulting in a bias towards Z-ring formation at new poles and the production of sequential minicells in the absence of the Min system. The ring disassembly defect might also directly cause the deficiency in nonpolar rings: by sequestering FtsZ84 at the old poles, its dispersal throughout the cell would be prevented, leading to a lowering of the local FtsZ84 concentration at nonpolar sites and a failure to form nonpolar rings.

One additional hypothesis that arises from this model is that the Min system may have a role in FtsZ polymer turnover. In min+ cells, for example, even though FtsZ84 is normally defective in disassembly, defects such as elongated septa are seldom detected. We speculate that this is because the MinCD inhibitor actively sweeps out any residual aggregated FtsZ84 at the new pole, while in cells lacking the Min proteins this turnover occurs significantly more slowly. Therefore, we propose that MinCD, in addition to inhibiting Z-ring formation (7), may also help to disassemble the Z ring after cell division. This would be consistent with the postulated role of the Min system in negatively regulating FtsZ structures in order to prevent nonspecific Z-ring formation. This model should also prompt a revisiting of the idea that old division sites are used for polar rings in min mutants. Although our integrated division site placement model (41) argues against the existence of predetermined division sites, it could be that under special conditions, such as those described herein, remnants of old sites play a role in polar ring assembly because the MinCD inhibitor is not around to remove them. Such an idea may be relevant to the understanding of how cell division is regulated in the many species, such as alpha-proteobacteria, that lack a discernible Min system (19).

We found that thermoresistant suppressors of ftsZ84 mutants arose at frequencies considerably higher than expected for a single allele-specific alteration. This fact, combined with the higher expression of ftsZ84 in the suppressors that we tested, suggests that suppression occurs via several different pathways that result in higher ftsZ84 expression. The number of promoters in the gene cluster preceding ftsZ and the known effects of ppGpp on transcription of this region are consistent with this idea. We were not able to successfully map the suppressor by linkage analysis, as the thermoresistant phenotype was unstable (X. C. Yu and N. Choudhary, unpublished results). However, the suppression was not a result of a change in the ftsZ84 gene, as confirmed by sequencing. If upstream transcription is affected in these suppressor strains, it is important to emphasize that expression of upstream genes, such as ftsQ and/or ftsA, may also be increased in these strains and may contribute to the phenotypes observed.

The formation of branches correlates well with the increased synthesis of FtsZ84 protein and altered septal morphology in the thermoresistant suppressor strains tested in this study. Branching has been found in other mutants, such as min, ftsL, and pbp mutants (3, 12, 22), and abnormal septal morphology has been observed with ftsZ26 mutants that form spiral septa (6). Growth rate also seems to play a role in other studies of branching (11). We found that branching frequency in the suppressor strains was greatest at higher growth temperatures. We speculate that this occurs because the defective FtsZ84 protein is less able to keep up with rapid wall growth at higher growth temperatures, resulting in abnormal septa. We also speculate that increased levels of FtsZ84 are not sufficient to overcome these problems because the protein is still defective in polymer turnover. Further work to determine the nature of the thermoresistant suppression and sufficiency of FtsZ84 levels for branching is underway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank N. Choudhary for help with some of the strain constructions and other members of the Margolin lab for comments and criticisms. We also thank D. Weiss for strain EC488.

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (MCB-9513521) and the National Institutes of Health (1R01-6M61704-01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Addinall S G, Cao C, Lutkenhaus J. Temperature shift experiments with an ftsZ84(Ts) strain reveal rapid dynamics of FtsZ localization and indicate that the Z ring is required throughout septation and cannot reoccupy division sites once constriction has initiated. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4277–4284. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4277-4284.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Åkerlund T, Bernander R, Nordström K. Cell division in Escherichia coli minB mutants. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2073–2083. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Åkerlund T, Nordström K, Bernander R. Branched Escherichia coli cells. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:849–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begg K, Nikolaichik Y, Crossland N, Donachie W D. Roles of FtsA and FtsZ in activation of division sites. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:881–884. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.881-884.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. Analysis of ftsZ mutations that confer resistance to the cell division inhibitor SulA (SfiA) J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5602–5609. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5602-5609.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. Isolation and characterization of ftsZ alleles that affect septal morphology. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5414–5423. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5414-5423.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. Cell division inhibitors SulA and MinCD prevent formation of the FtsZ ring. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1118–1125. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1118-1125.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Boer P, Crossley R, Rothfield L. The essential bacterial cell-division protein FtsZ is a GTPase. Nature. 1992;359:254–256. doi: 10.1038/359254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Boer P A, Crossley R E, Rothfield L I. Central role for the Escherichia coli minC gene product in two different cell division-inhibition systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1129–1133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Boer P A J, Crossley R E, Rothfield L I. A division inhibitor and a topological specificity factor coded for by the minicell locus determine the proper placement of the division site in Escherichia coli. Cell. 1989;56:641–649. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gullbrand B, Åkerlund T, Nordström K. On the origin of branches in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6607–6614. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.21.6607-6614.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guzman L-M, Barondess J J, Beckwith J. FtsL, an essential cytoplasmic membrane protein involved in cell division in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7716–7728. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu Z, Lutkenhaus J. Topological regulation of cell division in Escherichia coli involves rapid pole to pole oscillation of the division inhibitor MinC under the control of MinD and MinE. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:82–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Z, Mukherjee A, Pichoff S, Lutkenhaus J. The MinC component of the division site selection system in Escherichia coli interacts with FtsZ to prevent polymerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14819–14824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang J, Cao C, Lutkenhaus J. Interaction between FtsZ and inhibitors of cell division. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5080–5085. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5080-5085.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huls P G, Vischer N O, Woldringh C L. Delayed nucleoid segregation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:959–970. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu G, Draper G C, Donachie W D. FtsK is a bifunctional protein involved in cell division and chromosome localization in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:893–903. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu C, Stricker J, Erickson H P. FtsZ from Escherichia coli, Azotobacter vinelandii, and Thermotoga maritima—quantitation, GTP hydrolysis, and assembly. Cell Motil Cytoskelet. 1998;40:71–86. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1998)40:1<71::AID-CM7>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margolin W. Self-assembling GTPases caught in the middle. Curr Biol. 2000;10:328–330. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00458-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukherjee A, Lutkenhaus J. Dynamic assembly of FtsZ regulated by GTP hydrolysis. EMBO J. 1998;17:462–469. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulder E, EI'Bouhall M, Pas E, Woldringh C. The Escherichia coli minB mutation resembles gyrB in defective nucleoid segregation and decreased negative supercoiling of plasmids. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;221:87–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00280372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson D E, Young K D. Penicillin binding protein 5 affects cell diameter, contour, and morphology of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1714–1721. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1714-1721.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osteryoung K W, Vierling E. Conserved cell and organelle division. Nature. 1995;376:473–474. doi: 10.1038/376473b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phoenix P, Drapeau G R. Cell division control in Escherichia coli K-12: some properties of the ftsZ84 mutation and suppression of this mutation by the product of a newly identified gene. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4338–4342. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4338-4342.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powell B S, Court D L. Control of ftsZ expression, cell division, and glutamine metabolism in Luria-Bertani medium by the alarmone ppGpp in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1053–1062. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1053-1062.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raskin D M, de Boer P A. The MinE ring: an FtsZ-independent cell structure required for selection of the correct division site in E. coli. Cell. 1997;91:685–694. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raskin D M, de Boer P A. MinDE-dependent pole-to-pole oscillation of division inhibitor MinC in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6419–6424. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6419-6424.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raskin D M, de Boer P A. Rapid pole-to-pole oscillation of a protein required for directing division to the middle of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4971–4976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raychaudhuri D. ZipA is a MAP-Tau homolog and is essential for structural integrity of the cytokinetic FtsZ ring during bacterial cell division. EMBO J. 1999;18:2372–2383. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raychaudhuri D, Park J T. Escherichia coli cell-division gene ftsZ encodes a novel GTP-binding protein. Nature. 1992;359:251–254. doi: 10.1038/359251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith P K, Krohn R I, Hermanson G T, Mallia A K, Gartner F H, Provenzano M D, Fujimoto E K, Goeke N M, Olson B J, Klenk D C. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steiner W, Liu G, Donachie W D, Kuempel P. The cytoplasmic domain of FtsK protein is required for resolution of chromosome dimers. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:579–583. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steiner W W, Kuempel P L. Cell division is required for resolution of dimer chromosomes at the dif locus of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:257–268. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun Q, Margolin W. FtsZ dynamics during the cell division cycle of live Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2050–2056. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2050-2056.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun Q, Yu X-C, Margolin W. Assembly of the FtsZ ring at the central division site in the absence of the chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:491–504. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsui H C, Feng G, Winkler M E. Negative regulation of mutS and mutH repair gene expression by the Hfq and RpoS global regulators of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7476–7487. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7476-7487.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ward J E, Lutkenhaus J. Overproduction of FtsZ induces minicells in E. coli. Cell. 1985;42:941–949. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiss D S, Chen J C, Ghigo J M, Boyd D, Beckwith J. Localization of FtsI (PBP3) to the septal ring requires its membrane anchor, the Z ring, FtsA, FtsQ, and FtsL. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:508–520. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.508-520.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu X-C, Margolin W. Ca2+-mediated GTP-dependent dynamic assembly of bacterial cell division protein FtsZ into asters and polymer networks in vitro. EMBO J. 1997;16:5455–5463. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu X-C, Margolin W. FtsZ ring clusters in min and partition mutants: role of both the Min system and the nucleoid in regulating FtsZ ring localization. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:315–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu X-C, Tran A H, Sun Q, Margolin W. Localization of cell division protein FtsK to the Escherichia coli septum and identification of a potential N-terminal targeting domain. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1296–1304. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1296-1304.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu X C, Weihe E K, Margolin W. Role of the C terminus of FtsK in Escherichia coli chromosome segregation. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6424–6428. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6424-6428.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]