Abstract

Female sex workers (FSW) are a key population in the HIV epidemic and face high levels of violence. While women globally are predominantly at risk of intimate partner violence (IPV), FSW are additionally vulnerable to violence from clients, police, and pimps associated with their occupation. FSW are therefore at risk of cumulative trauma from polyvictimization, or violence from multiple types of perpetrators. Polyvictimization is a driver of morbidity and mortality in numerous populations, but there has been little research on how multiple types of victimization are related to one another in FSW. A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 754 FSW from three cities in the Russian Federation. Surveys assessed lifetime experiences of client, police, intimate partner, and pimp violence. Multivariate log-binomial and Poisson regression were used to test associations between these types of violence. Forty-five percent experienced any type of violence, including 31.7% from clients, 16.0% from police, 15.7% from intimate partners, and 11.4% from pimps. One fifth (20.4%) experienced polyvictimization. Client violence was central to polyvictimization: Only 5.9% of polyvictimization occurs without client violence. When client violence was not present, police, pimp, or IPV co-occurred significantly less than would be expected under an assumption that these types of violence occur independently (p < .001). However, they co-occurred more than would be expected when client violence is present. After adjusting for other types of violence experienced and demographic factors, experiencing client violence was independently associated with police violence (adjusted relative risk [ARR] = 2.77, 95% confidence interval [CI] [1.67, 4.59]), IPV (ARR = 3.67, 95% CI [1.95, 6.89]), and pimp violence (ARR = 5.26, 95% CI [2.80, 9.86]). Client violence may drive exposure to other types of violence and enable polyvictimization in a way that other types of violence do not in this setting. Violence prevention interventions may achieve maximal effect in reducing multiple types of violence by focusing on client violence.

Keywords: polyvictimization, sex work, intimate partner violence, client violence

Introduction

Sex workers are an underserved population at high risk of violence (Decker, Crago, et al., 2014). Women globally are most at risk of physical and sexual violence from intimate partners (Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006), but female sex workers (FSW) face additional violence from clients, pimps, and police in the course of their work (Decker, Crago, et al., 2014). Violence from each of these perpetrators is distinct and typically different in context, frequency, intensity, and impact on physical, sexual, and mental health (Decker, Pearson, Illangasekare, Clark, & Sherman, 2013; Panchanadeswaran et al., 2008).

Polyvictimization, defined as experiencing multiple different types of violence, crime, abuse, or victimization, is a concept that arose in the field of child abuse research. Tools from polyvictimization research have been underutilized to study exposures to multiple types of violence in adulthood and among FSW, even though FSW frequently face multiple types of violence. Studying the effects of a single type of violence can be problematic when other co-occurring types of violence may contribute to negative health outcomes, because it fails to take into account other relevant violence exposures that also drive health risk (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2009). The ground-breaking Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study showed that experiencing one type of violence is a risk factor for experiencing other types of violence, leading to a clustering of violence in individuals and an increasing cumulative burden on health (Felitti et al., 1998). For instance, children who experience physical assault are 5 times more likely to have been sexually assaulted, 4 times more likely to have been maltreated, and 2.5 times more likely to witness violence (Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, & Hamby, 2009). Few surveys of FSW assess multiple types of violence and tend to study either a single type of violence (usually client violence) or violence from “any” unspecified perpetrator (Deering et al., 2014). In this analysis, we apply a polyvictimization framework to FSW to develop a comprehensive understanding of violence victimization experiences in this population.

Similar to polyvictimization, other fields explore multiple types of victimization and arose in parallel disciplines or different study populations, such as syndemic theory, complex trauma, and cumulative trauma theory (Musicaro et al., 2017; Singer, 1996). We use language drawn from a polyvictimization framework due to its focus on interpersonal trauma and its focus on how multiple types of violence cluster with, are associated with, and may potentiate the risk for one another.

Polyvictimization as Applied to HIV Risk Among FSW

The singular focus on client violence and lack of attention to intimate partners in research with FSW is in part due to persistent myths in the HIV literature that FSW do not have intimate partners (Strathdee, Crago, Butler, Bekker, & Beyrer, 2015). As recognition of the full range of perpetrators of violence against FSW has grown, research has begun to specify perpetrators to understand, for example, violence from intimate partners of FSW (Beattie et al., 2016; Ulibarri et al., 2018) and police (Decker, Crago, et al., 2014). Recent work with FSW in South Africa used a polyvictimization lens and found high levels of polyvictimization by clients, police, and intimate partners (Coetzee, Gray, & Jewkes, 2017). Similarly, work from India found that violence from multiple perpetrators was common and that polyvictimization was linked to sexually transmitted infections and sexual risk (Beksinska et al., 2018). Because literature about FSW often focuses on how a type of violence is associated with HIV risk, relatively few studies assess associations between types of violence. We seek to describe polyvictimization in a sample of Russian FSW and to quantify the relationship between different types of violence: intimate partner violence (IPV), client violence, pimp violence, and police violence.

Although much polyvictimization research divides violence type by whether the violence is physical or sexual in nature regardless of perpetrator, we define violence types based on perpetrator for the purposes of this study with FSW for several reasons. First, from a public health perspective, perpetrator type is often more directly linked to health impact than whether the violence is physical or sexual. For instance, police violence can impact HIV risk among FSW through many pathways beyond direct HIV transmission during police sexual violence, including (a) pushing FSW to more “underground” locations with less police surveillance, which may feature riskier clients or less ability to refuse riskier types of sex; (b) encouraging FSW to not carry condoms on their person so that they will not be used as evidence of prostitution by police; or (c) leading to arrest and detention in prisons where needle sharing may be common (Decker, Crago, et al., 2014). All of these pathways toward increased HIV risk are relevant for police violence whether the police officer uses physical or sexual violence. Second, recent evidence from a systematic review has shown that interventions that attempt to protect potential victims from abuse often have limited success at reducing victimization, and that primary prevention interventions should focus on potential perpetrators (Ellsberg et al., 2014). The focus of our analysis on perpetrator-specific types of violence can inform interventions for primary prevention of violence against FSW targeted at perpetrators, rather than perpetrator-non-specific measures of “physical violence” or “sexual violence.” Third, women may be most likely to group all violence they experienced from one perpetrator, whether physical or sexual, as part of the same abuse experience. For instance, if a sex worker is both beat up and sexually assaulted by a police officer (multiple “types” of violence but one perpetrator), she will likely conceptualize this as a single incident of police abuse, rather than dividing the experience into being “polyvictimized” with physical and sexual violence. Finally, while women generally are primarily at risk of violence from intimate partners (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2006), perpetrators of violence against FSW are much more varied. This makes studying polyvictimization by perpetrator much more critical in FSW populations than it may be in women who are not FSW.

Sex Work in Russia

This study was conducted in the Russian Federation, where physical and sexual violence against FSW is prevalent (Decker et al., 2012; Decker, Wirtz, et al., 2014; Odinokova, Rusakova, Urada, Silverman, & Raj, 2014). Sex work is criminalized as an administrative offense in the Russian Federation and punishable by a fine of 2,000 rubles (US$60), while drug use is punishable with punitive detoxification programs, fines, or imprisonment (United States Department of State, 2014). Sex workers’ rights groups report that the number of FSW has increased dramatically in Russia since the 2014 financial crisis, and that over 12,000 FSW were charged with administrative offenses in 2015, with many more subject to extortion by police and charged with crimes (Sharkov, 2016; Silver Rose, 2016). Although sex work is technically an administrative rather than a criminal offense, rights groups complain that police often arrest and jail FSW without basis in law and extort larger fines than are legally allowed (Silver Rose, 2016). Pimps and managers often have monetary arrangements with police, so law enforcement efforts fall primarily on FSW. The Russian government has increasingly pushed “traditional values” in cooperation with the Russian church, resulting in a lack of recognition of sex workers’ rights and a lack of inclusion of sex workers in HIV programming (Silver Rose, 2016). Anti-violence work is further complicated by a law passed in January 2017 that partially decriminalized domestic violence unless it results in a “serious” injury or is a repeat offense (Solomon, 2017). In spite of repression, increasing organizing and advocacy by FSW recently resulted in submission of an Alternative Report to the UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights and the committee’s subsequent recommendation to decriminalize sex work in Russia to prevent human rights violations (Silver Rose, 2016). FSW typically recruit clients on the street, in saunas, in hotels, online, or from tochkas (areas along streets where sex workers gather and meet clients out of cars), with street sex workers typically being lower paid and more vulnerable to client and police violence and HIV. Russia is one of just a few countries in the world where HIV prevalence and incidence are still increasing dramatically, with incidence increasing nearly 5% to 10% per year (Beyrer, Wirtz, O’Hara, Léon, & Kazatchkine, 2017; Clark, 2016; Pokrovskiy, Ladnaya, Tushina, & Buravtsova, 2015). In the parent study, conducted in 2011, HIV prevalence was 3.9% (Decker, Wirtz, et al., 2014).

In this study, we use a polyvictimization framework to understand how client, intimate partner, police, and pimp violence cluster in a sample of Russian FSW.

Method

Study Setting

Data were collected in 2011 from a sample of N = 754 FSW from Tomsk, Kazan, and Krasnoyarsk, Russia, as part of a large-scale program evaluation for Global Fund program activities, Global Efforts Against HIV/AIDS in the Russian Federation (GLOBUS; Decker, Wirtz, et al., 2014). Kazan is the eighth-largest city in the Russian Federation and is 500 miles east of Moscow. Tomsk and Krasnoyarsk are smaller cities located in Siberia, the region with the fastest growing HIV epidemic in Russia in 2017 (Beyrer et al., 2017).

Study Recruitment and Eligibility

Recruitment at each site was via respondent-driven sampling (RDS), a type of chain-referral sampling designed for hard-to-reach or hidden populations that builds on snowball sampling by restricting the number of recruits allowed per participant to promote longer recruitment chains, and by allowing for weighted prevalence estimates that adjust for bias introduced by nonrandom sampling (Heckathorn, 1997). Individuals were eligible for the study if they were cisgender women, at least 18 years old, worked or resided in one of the three cities, and had exchanged sex for money, drugs, or shelter in the past 3 months. Seeds were purposively selected by local partners to maximize diversity, including street and off-street sex work and injecting and non-injecting FSW. Respondents were given five recruitment coupons each to recruit up to five FSW peers. Study interviewers were local Russian nongovernmental organization (NGO) staff (AIDS Infoshare) trained by Johns Hopkins University staff. Interviews in Tomsk and Krasnoyarsk took place in the local NGO’s office; in Kazan, interviews were also conducted in a mobile unit at locations across the city due to the remoteness of the local office. Verbal informed consent was used to protect confidentiality and administered by NGO staff. As part of the consent process, participants were told that their participation was completely voluntary and that receipt of HIV-related services from the NGO did not depend on participation. Interviews were self-administered on a computer and took 20 to 30 min, followed by OraQuick HIV testing. Women received a small gift (<US$5) for participation. The study was reviewed and approved by the Open Health Institute in Moscow. Because the primary focus of the survey was to evaluate the quality of services provided by the NGO, the study was considered exempt as public health practice by the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (IRB). The current secondary analysis of existing, de-linked, deidentified data was considered not human subjects research by the same IRB (Decker, Wirtz, et al., 2014).

Measures

Extensive qualitative formative research informed survey development and implementation (Decker, Wirtz, et al., 2014). The survey was developed in English, translated into Russian, and piloted by NGO staff and adjusted before implementation.

The violence exposures are lifetime exposure to violence by four perpetrators: IPV (hit, pushed, slapped, or otherwise physically hurt by a boyfriend, husband, or someone they were dating), client violence (hit, pushed, slapped, otherwise physically hurt, beaten, strangled, choked, stabbed, threatened with a weapon, thrown out of a moving car, or physically forced to have vaginal or anal sex by a client), pimp violence (hit, pushed, slapped, otherwise physically hurt, beaten, strangled, choked, stabbed, threatened with a weapon, thrown out of a moving car, of forced to have sex by a pimp or momka, i.e., female pimp), and police violence (involved in a subbotnik, i.e., sexual violence from police under threat of incarceration, or coerced to provide sex to police to be able to sell sex without risk of fine or arrest). Intimate partner, client, pimp, and police violence were assessed with 1, 4, 3, and 2 questions, respectively. Extensive formative research identified these types of violence as most relevant in the lives of FSW in this setting. Measures are based on the Conflicts Tactics Scale 2 (CTS-2) which asks about specific behaviors rather than asking about abuse generally (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). CTS-2-based questionnaires have been used successfully in diverse samples of FSW (Carlson et al., 2012; Gupta, Reed, Kershaw, & Blankenship, 2011). Formative research also informed development of setting-specific adaptations, such as including common types of physical abuse from pimps or momkas and subbotnik, or coerced sex with police officers to avoid arrest (Decker, Wirtz, et al., 2014). We use the term “polyvictimization” to refer to experiencing violence from more than one of the four types of perpetrators, and the term “monovictimization” to distinguish those who experience violence by exactly one type of perpetrator.

The following variables were selected as potential confounders and included in all multivariate models based on a review of the literature and bivariate association with at least one type of violence at p < .10: demographic factors (age, current number of nonpaying intimate partners, education level, having another income besides sex work, relationship status, recent injecting drug use, and monthly salary) and sex work contextual factors (engaging in street-based sex work, average number of vaginal or anal sex clients per night, duration of time in sex work, and age of entry into sex work).

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for (a) the prevalence of each of the four types of violence (client, police, intimate partner, and pimp violence); (b) the prevalence of experiencing only one type of violence (monovictimization) versus violence that is perpetrated by two, three, or four different types of perpetrators (polyvictimization); and (c) the prevalence of each violence victimization profile (16 possible profiles from the four types of violence). To evaluate whether violence experienced from the four different types of perpetrators are independent or clustered, we calculated the expected prevalence of each violence profile assuming violence from each perpetrator is independent (i.e., multiplying the independent probabilities of experiencing or not experiencing each type of violence), and compared the expected prevalence to that observed within the sample using the Clopper–Pearson exact method (Clopper & Pearson, 1934).

Corresponding to the polyvictimization concept that violence exposures are mutually reinforcing and that experiencing one type of violence may increase risk for experiencing violence from additional perpetrators, we used a series of multivariate log-binomial regression models to quantify the relative risk (RR) of experiencing violence by each of the four perpetrators as a function of the presence of violence from the remaining three perpetrators. First, we estimated the adjusted relative risk (ARR) for each of the 12 possible pairwise combinations of perpetrators (i.e., client and police, client and intimate partner, client and pimp, etc.) adjusted only for potential confounding variables related to demographics and sex work context (Model 1). We subsequently estimated the ARR accounting for violence experienced from the other perpetrators and the potential confounding variables (Model 2). In several cases, the log-binomial regression did not converge and was replaced by a Poisson regression model. All regression models were fit accounting for the stratified clustered survey design, with city defining the strata and recruitment chain defining the cluster (Szwarcwald, de Souza Júnior, Damacena, Junior, & Kendall, 2011). RDS estimators were not used, as participants could not confidently estimate their network size.

The amount of missing data for each variable used in the analysis ranged from 0.3% to 10.4%; IPV was the only variable missing more than 10% of values. Approximately 16% of the sample was missing at least one of the four key violence exposure variables. Variables that were missing less than 2% of values were imputed using the mean or mode of respondents in the same recruitment chain. The remaining variables were imputed via multiple imputation with 20 multiply imputed datasets. Both descriptive statistics and regression model results are averaged across the imputed datasets.

Results

The average FSW was in her mid-20s and had entered sex work in her early 20s (Table 1). On average, FSW made 38,732 rubles (US$685) per month and three quarters (74.0%) relied on sex work as their only source of income. Slightly more than half (57.2%) had at least one intimate partner. The most common relationship status was never married (41.6%), with the next most common responses dating someone (19.8%) and living together as if married (19.1%). Nearly half (44%) had at least one child. Most had a secondary education (44.4%) or a secondary education with a diploma (35.4%). Street-based sex work was the most common sex work venue (65.9%), with hotel-based (32.1%), Internet-based (15.3%), and escort (17.6%) services also common. Nearly half currently work with a pimp, momka, agency, or tochka (a loosely organized group operating out of cars on the side of the road; 45.4%), with a roughly equal number never having worked with anyone (43.9%) and the remainder (10.5%) formerly having done so.

Table 1.

Demographic and Sex Work Context Factors in a Sample of Russian Female Sex Workers (N = 754).

| Demographic Factors | |

|---|---|

| Mean (range) | |

| Age, years | 26.0 (18, 49) |

| Age of entry into sex work, years | 21.6 (13, 40) |

| Monthly salary, rubles | 38,732 (77, 200,000) |

| Prevalence % (n)a | |

| Current number of nonpaying intimate partners | |

| None | 42.8 (323) |

| 1 | 52.8 (398) |

| 2 or more | 4.4 (33) |

| Education level | |

| Never attended school, have not completed primary school, or primary education | 1.5 (11) |

| Secondary education | 44.4 (335) |

| Specialized secondary education (diploma) | 35.4 (267) |

| Undergraduate education | 13.4 (101) |

| Graduate education | 5.3 (40) |

| Other income besides sex work | |

| Yes | 26.0 (196) |

| No | 74.0 (558) |

| Current relationship status | |

| Never married | 41.6 (314) |

| Dating someone | 19.8 (149) |

| Living together as married | 19.1 (144) |

| Legally married | 0.5 (34) |

| Divorced or separated | 13.1 (99) |

| Widowed | 1.9 (14) |

| Number of children | |

| Zero | 56.0 (422) |

| One | 32.6 (246) |

| Two or more | 11.4 (86) |

| Injecting drug use | |

| Yes, in the past 6 months | 10.7 (81) |

| Never or more than 6 months ago | 89.3 (673) |

| Sex Work Context Factors | |

| Duration of time in sex work | |

| Six months or less | 5.1 (38) |

| Six months or more, but less than 1 year | 7.6 (57) |

| One year or more, but less than 2 years | 15.2 (115) |

| Two years or more, but less than 3 years | 20.2 (152) |

| Three years or more, but less than 4 years | 12.9 (97) |

| Four years or more | 38.9 (293) |

| Sex work venue | |

| On the street | 65.9 (497) |

| Hotel | 32.1 (242) |

| Train station | 0.1 (1) |

| Through the Internet | 15.3 (115) |

| Escort service | 17.6 (133) |

| Salon that serves clients | 3.2 (24) |

| Club | 3.3 (25) |

| Sauna | 1.9 (14) |

| Other | 24.8 (187) |

| Works with pimp agency, pimp, momka, or tochka | |

| Currently | 45.4 (342) |

| Formerly, but now independent | 10.5 (79) |

| Never worked with one | 43.9 (331) |

| Average number of vaginal or anal sex clients per night | |

| None (only oral sex) | 4.5 (34) |

| One | 7.4 (56) |

| Two | 23.8 (179) |

| Three | 18.4 (139) |

| More than three | 45.8 (345) |

The ns are approximate given averaging across multiple imputation datasets.

Distribution of Types of Violence and of Polyvictimization in the Sample

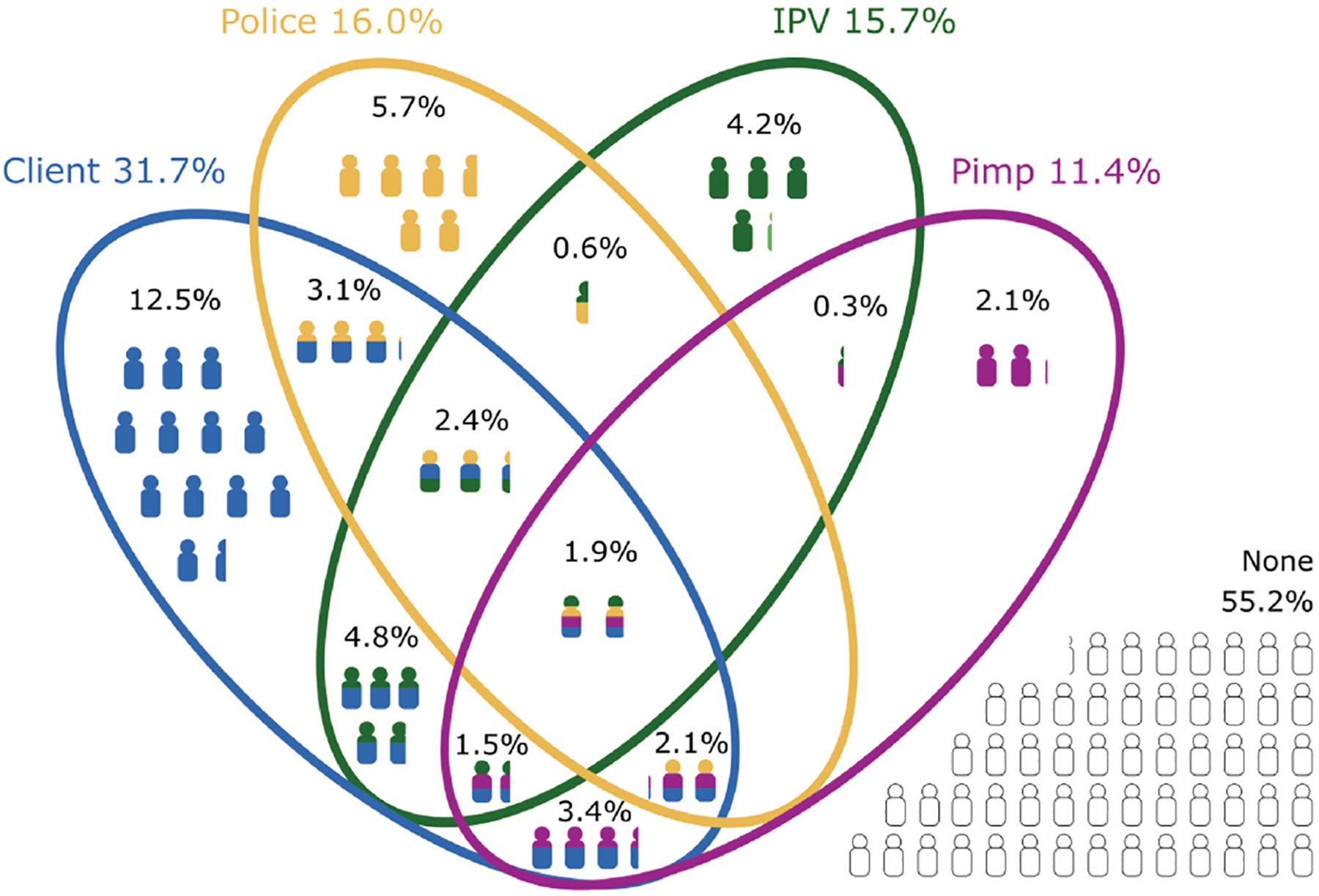

Figure 1 shows the lifetime prevalence of each type of violence and each victimization profile. Client violence (31.7%) was more common than police (16.0%), intimate partner (15.7%), or pimp (11.4%) violence. Slightly less than half the sample (44.8%) experienced at least one type of violence (Table 2). Of those who experienced at least one type of violence, 45.4% experienced polyvictimization (20.4% of the total sample).

Figure 1.

Lifetime prevalence of client, police, intimate partner, and pimp violence among a sample of Russian FSW (N = 754).

Note. FSW = Female sex workers.

Table 2.

Number of Types of Violence Experienced (N = 754) and Prevalence of Each Type of Violence Among Polyvictims in a Sample of Russian Sex Workers (n = 154).

| % (n)a | |

|---|---|

| No violence | 55.2 (416) |

| At least one form of violence | 44.8 (338) |

| Monovictimization | |

| One type of violence | 24.5 (185) |

| Polyvictimization | |

| Two types of violence | 12.2 (92) |

| Three types of violence | 6.3 (47) |

| Four types of violence | 1.9 (14) |

| Any polyvictimization (2–4 types of violence) | 20.4 (154) |

| Prevalence Among Polyvictims % (n)a | |

| Types of violence experienced among polyvictims (n = 154b) | |

| Client violence | 94.1 (146) |

| Police violence | 49.5 (76) |

| Intimate partner violence | 56.4 (89) |

| Pimp violence | 45.1 (69) |

The ns are approximate given averaging across multiple imputation datasets.

Sample size of polyvictims varies slightly by imputation dataset.

Client violence was the defining experience of polyvictimization, with virtually all polyvictims (94.1%) experiencing client violence, as compared with 49.5% of polyvictims experiencing police violence, 56.4% experiencing IPV, and 45.1% experiencing pimp violence (Table 2). While over 20% of FSW experienced polyvictimization, just 0.9% of FSW are polyvictims who did not experience client violence (Figure 1). Polyvictimization frequently occurs without police, intimate partner, or pimp violence, but almost never occurs without client violence.

When client violence is not present, IPV, pimp violence, and police violence co-occur less frequently than would be expected under an assumption of independence (Table 3). IPV and pimp violence occur in 0.3% of the sample where 1.0% is expected (p = .041), IPV and police violence occur in 0.6% where 1.5% is expected (p = .052), police and pimp violence occur in 0% where 1.1% is expected (p < .001), and IPV, police violence, and pimp violence occur in 0% where 0.2% is expected (p = .277). Taken together, the expected occurrence of these four victimization profiles is 3.8% and the observed prevalence is 0.9% (p < .001; not shown in table). These three types of violence rarely co-occur with one another, unless client violence is also present.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Polyvictimization and Observed and Expected Lifetime Prevalence of Each Violence Profile in a Sample of Russian Female Sex Workers (N = 754).

| Observed Prevalence (%) | Expected Prevalence, Assuming Independence (%) | p | Direction of Difference Where Significant Differences Observed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No violence | 55.2 | 42.9 | <.001 | More than expected |

| One type of violence (monovictimization) | 24.5 | 41.5 | <.001 | Less than expected |

| IPV alone | 4.2 | 8.0 | <.001 | Less than expected |

| Client violence | 12.5 | 19.9 | <.001 | Less than expected |

| Police violence | 5.7 | 8.2 | .011 | Less than expected |

| Pimp violence | 2.1 | 5.5 | <.001 | Less than expected |

| Two types of violence | 12.2 | 13.6 | .265 | |

| IPV + client violence | 4.8 | 3.7 | .122 | |

| IPV + pimp violence | 0.3 | 1.0 | .041 | Less than expected |

| IPV + police violence | 0.6 | 1.5 | .052 | |

| Client + pimp violence | 3.4 | 2.6 | .137 | |

| Client + police violence | 3.1 | 3.8 | .340 | |

| Police + pimp violence | 0.0 | 1.1 | <.001 | Less than expected |

| Three types of violence | 6.3 | 1.9 | <.001 | More than expected |

| IPV + client + police | 2.4 | 0.7 | <.001 | More than expected |

| IPV + client + pimp | 1.5 | 0.5 | .002 | More than expected |

| Client + police + pimp | 2.1 | 0.5 | <.001 | More than expected |

| IPV + police + pimp | 0.0 | 0.2 | .277 | |

| Four types of violence | 1.9 | 0.1 | <.001 | More than expected |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence.

There are strong associations between each type of violence and every other type of violence at p < .01, even after adjusting for potential confounding variables related to demographics and sex work context (Table 4, Model 1). For instance, 30.7% of those experiencing police violence also experience IPV, whereas only 12.8% of those who do not experience police violence experience IPV (ARR = 2.39, 95% confidence interval [CI] [1.68, 3.40]). While all four types of violence are associated with one another, the associations between client violence and the other types of violence are particularly strong. Exposure to client violence was associated with the outcomes of police violence (ARR = 3.09, 95% CI [1.92, 4.98]), IPV (ARR = 3.89, 95% CI [2.21, 6.84]), and pimp violence (ARR = 5.95, 95% CI [3.21, 11.03]). These associations persisted after further adjustment for other types of violence experienced; specifically, client violence remained associated with police violence (ARR = 2.77, 95% CI [1.67, 4.59]), IPV (ARR = 3.67, 95% CI [1.95, 6.89]), and pimp violence (ARR = 5.26, 95% CI [2.80, 9.86]), all at p < .001 (Table 4, Model 2). In contrast, the associations observed between police, intimate partner, and pimp violence did not persist after adjustment for other types of violence experienced, with the sole exception of pimp violence being associated with police violence (ARR = 1.33, 95% CI [1.05, 1.68]). Client violence is more strongly associated with IPV, pimp violence, and police violence than nearly any other demographic or sex work context variable (see Appendix Table A1 for full results of multivariate models, including coefficients for demographic and sex work context variables).

Table 4.

Associations Between Violence Exposure Variables (N = 754).

| Outcome | Exposure | Prevalence of the Outcome Among Exposed vs. Unexposed (%) | Model 1 ARR Adjusted for Potential Confounders Only ARR (95% CI)a | Model 2 ARR Adjusted for Other Types of Violence and Potential Confoundersb ARR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Police | Client | 30.1 vs. 9.5 | 3.09 [1.92, 4.98] *** | 2.66 [1.57, 4.50] *** |

| IPV | 31.3 vs. 13.2 | 1.81 [1.29, 2.54] ** | 1.24 [0.86, 1.78] | |

| Pimp | 36.6 vs. 13.4 | 1.97 [1.42,2.74] *** | 1.35 [1.07, 1.71] * | |

| IPV | Client | 33.2 vs. 7.6 | 3.89 [2.21, 6.84] *** | 3.42 [1.86, 6.28] *** |

| Police | 30.7 vs. 12.8 | 2.03 [1.42, 2.92] *** | 1.43 [0.95, 2.14] | |

| Pimp | 32.7 vs. 13.5 | 2.07 [1.45, 2.95] *** | 1.25 [0.87, 1.79] | |

| Pimp | Client | 28.0 vs. 3.7 | 5.95 [3.21, 11.03] *** | 5.48 [2.90, 10.34] *** |

| Police | 26.1 vs. 8.6 | 1.95 [1.33, 2.86] ** | 1.22 [0.88, 1.69] | |

| IPV | 23.7 vs. 9.1 | 1.97 [1.25, 3.11] ** | 1.14 [0.78, 1.68] | |

| Client | Police | 59.7 vs. 26.4 | 1.92 [1.38, 2.66] *** | 1.54 [1.12, 2.19] * |

| IPV | 67.0 vs. 25.1 | 2.10 [1.47, 2.99] *** | 1.75 [1.26, 2.44] ** | |

| Pimp | 77.8 vs. 25.7 | 2.33 [1.84, 2.95] *** | 1.94 [1.54, 2.43] *** |

Note. ARR = adjusted relative risk; CI = confidence interval; IPV = intimate partner violence.

Adjusted for age, participation in street sex work, average number of vaginal or anal sex clients per day, having another source of income besides sex work, injecting drug use, number of current intimate partners, number of years in sex work, educational level, age of entry into sex work, relationship status, and monthly salary.

Adjusted for other types of violence experienced (client, police, intimate partner, or pimp violence), age, participation in street sex work, average number of vaginal or anal sex clients per day, having another source of income besides sex work, injecting drug use, number of current intimate partners, number of years in sex work, educational level, age of entry into sex work, relationship status, and monthly salary.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Boldface indicate p < 0.05.

Discussion

In this sample of Russian FSW, client, police, intimate partner, and pimp violence were prevalent and 20.4% had experienced lifetime polyvictimization. These types of violence formed a tightly clustered constellation that seemed to revolve around client violence. Client violence was not only the most prevalent type of violence but was also a strong and highly significant correlate of the other three types of violence. Indeed, client violence was more strongly associated with IPV, pimp, and police violence than nearly any other demographic or sex work context variable.

Implications for Interventions

Client violence is strongly associated with police, intimate partner, and pimp violence, and approximately 40% of people experiencing client violence experience one of these other types of violence. If this association is causal and client violence is actually precipitating the other three forms of violence, primary prevention of client violence could substantially lower victimization from other types of violence as well. Given evidence from the syndemic and polyvictimization literatures that there is a dose-response effect whereby accumulating a greater number of types of victimization steadily increases health risks such as HIV, bringing down the number of types of violence experienced could crucially alter outcomes across many domains of health and could be accomplished efficiently by targeting client violence (Gilbert et al., 2015; Meyer, Springer, & Altice, 2011; Stall et al., 2003). If bidirectional causation occurs between client violence and the other types of violence, then targeting multiple types of violence in concert will be critical, as we would expect any one type of violence to be intractable to prevent unless the other types are also addressed.

Disaggregating violence by perpetrator type is critical for designing violence prevention and support interventions, because interventions likely require tailoring specific to perpetrator. For example, interventions to reduce client violence may include structural changes to sex work venues such as requiring client sign-in, emergency call buttons, and supportive managerial policies and crisis response (Shannon et al., 2015). For street-based FSW, interventions to reduce client violence may include improved street lighting, creating safe communal spaces that FSW can go to, use of a “buddy system” with other FSW, and finding locations to sell sex that do not require getting into a client’s car. Interventions to reduce police violence may involve training police to change common practices such as routinely searching sex workers to confiscate condoms (Shields, 2012), policy advocacy to change local laws related to sex work and loitering, and facilitating sex worker–police partnerships (Beattie et al., 2010; Reza-Paul et al., 2012). In the Russian context, such policy interventions are likely to be long-term battles, given a conservative legislative shift toward “traditional values.” At the individual level, a St. Petersburg-based NGO recently released a Russian-language guide by and for sex workers on safety strategies to use while working (Silver Rose, 2017). Communal safe spaces run by sex worker NGOs exist in some Russian cities, but the removal of international funding from Russian HIV response efforts in 2012 and the refusal of the Russian government to supply funding means that support for such interventions is limited (Cohen, 2010).

With regards to secondary prevention or response interventions, these findings affirm that addressing the impact of just one type of violence is an overly narrow approach. Polyvictimization is common, with 20.4% of the sample and nearly half of violence victims (46%) being polyvictims. When working with survivors of violence, violence response programs should comprehensively assess violence these women may be experiencing from multiple sources and not just the first type of violence she may have disclosed, as other types of trauma are likely. Interventions that address one type of violence are also an efficient way of identifying women who have been exposed to another type of violence. For instance, while pimp violence affects roughly 1 in 9 women, a program working with women who experienced client violence could expect more than 1 in 4 women to have experienced pimp violence as well. Experiencing one type of violence is a strong risk factor for experiencing any other type of violence, as shown by the highly significant risk ratios between all pairwise combinations of violence types (Model 1). In the Russian context, anti-violence NGOs are stretched thin, as only 42 domestic violence shelters exist in the entire country, comprising some 400 beds (Lesur, Stelmaszek, & Golden, 2014). Globally, traditional violence intervention programs such as domestic violence shelters have historically not been tailored to the unique needs of FSW; indeed, FSW have experienced discrimination when trying to access social service or criminal justice responses to violence (Jackson, 2016; Law, 1999). Underinvestment in violence response services and insufficient laws and policing of violence against women are not unique to the Russian Federation and are issues globally.

The results from multivariate regression models including demographic covariates also suggest that relationship status may be an underappreciated way to identify women at highest risk for client violence in this setting. Unsurprisingly, having more intimate partners was associated with IPV, but relationship status was also a strong correlate of client violence. Women who were dating someone, women who were living with someone as though married, and women who were divorced or separated were all roughly 2 times as likely to experience client violence as those who were never married, adjusting for other violence experienced and demographic factors. Causal explanations for this observed relationship are unclear. This may be a reflection of the fact that in many settings, intimate partners may start off as clients before becoming boyfriends (Karandikar & Próspero, 2010). It could also reflect greater precariousness in FSW’s living situation when FSW are involved in relationships that are not legally binding marriages or when they extricate themselves from prior relationships. Regardless of the mechanism, relationship status was strongly linked to client violence and should be considered in intervention programming as a risk factor for client violence. Interventions to reduce client violence should also not just focus on interactions between FSW and their clients, but also take into account how intimate relationship context may be shaping risk. Perhaps surprisingly, education and having another income beside sex work were not significantly associated with most types of violence. While being able to draw a reliable income from other types of work can increase FSW’s ability to decline riskier clients and sex work situations, it may be that for some women, needing to hold down an additional job is not indicative of reliable income but is instead reflective of even greater economic precariousness.

Implications for Research

Findings indicate that it is critical for research and surveillance systems to address violence and to address multiple, distinct types of violence among FSW. Early research on violence against FSW did not distinguish between perpetrators or only measured violence by one type of perpetrator (Decker et al., 2010; Lang, Salazar, DiClemente, & Markosyan, 2013; Shannon, Kerr, et al., 2009; Swain, Saggurti, Battala, Verma, & Jain, 2011; Ulibarri et al., 2011). This study expands knowledge of how multiple types of violence are distributed in this population and shows that different types of violence vary in prevalence and are more likely to affect different demographic segments of the population. Due to the clustering effect between types of violence, inquiring about one type of violence is likely insufficient to fully assess cumulative exposure to violence among FSW.

Clustering of intimate partner, police, and pimp violence with client violence may reflect a number of potential causal explanations that would require longitudinal data to evaluate. The simplest causal explanation for the observed data is that client violence is somehow promoting risk for other types of violence in this setting. This causal pathway would be consistent with our findings that client violence occurs in virtually all polyvictimization situations. It would also be consistent with our finding that client violence is significantly and independently associated with the three other types of violence. For instance, client violence may lead to police violence if women seek recourse from police following client violence, or commotion caused by client violence draws the attention of law enforcement; this contact with law enforcement increases the potential for police violence. In many settings, client violence frequently occurs in the context of negotiating payment for sex or occurs when the client refuses to pay or robs the sex worker (Lim et al., 2015). These lost wages could trigger violence from intimate partners or pimps who often take a cut of the money (Karandikar & Próspero, 2010). Although FSW often do not report theft or violence to the police, this type of client violence could lead to police violence if a woman reports the robbery to police and is abused (Sherman et al., 2015). For FSW who have not disclosed their sex work to their intimate partners, observable injuries from client violence may also trigger revelation of their occupation; partner discovery of sex work status is a frequent trigger of abuse from intimate partners (Decker et al., 2013).

Alternatively, it may be that there are causal mechanisms in the other direction: being exposed to police violence, IPV, or pimp violence increases the risk of subsequently experiencing client violence. Intimate partners may initiate violence to push women to sell sex to more clients or riskier clients to make more money or obtain drugs (Decker et al., 2013). Women may also engage in riskier sex work where they may be more vulnerable to client violence to become financially independent from abusive partners (Choudhury, Anglade, & Park, 2013). Pimps may use physical and sexual violence to ensure compliance with higher client volume or riskier clients than the sex worker would otherwise choose, which could increase exposure to client violence (Decker et al., 2013; Goldenberg et al., 2012; Ratinthorn, Meleis, & Sindhu, 2009). Police violence and harassment pushes sex workers more underground where they may be forced to take riskier or more violent clients (Erausquin, Reed, & Blankenship, 2011; Shannon & Csete, 2010; Shannon, Strathdee, et al., 2009). Further research to understand the strength and direction of causal associations between multiple types of violence, in the Russian Federation and in other settings, is critical for designing effective, comprehensive violence interventions among FSW.

Findings also extend polyvictimization and syndemic frameworks, which often present all types of violence as potentiating all the other types of violence (Singer, 1996). Our findings suggest that not all types of violence are equal in increasing risk for the other types of violence. It may be that only some types of violence (in this study, client violence) increase risk for other types of violence, or that the effect of some types of violence in potentiating risk is stronger than other types.

Findings should be considered in the light of several limitations, particularly the cross-sectional nature of the survey. Longitudinal data would help establish temporality and narrow down potential causal mechanisms for the patterns observed in the study. Qualitative data would also help put results in context and suggest pathways by which each type of violence may potentiate risk for other types of violence. Measurement limitations include inconsistencies in how different types of violence were assessed in the survey, with client violence likely being the most sensitive measure due to a greater number of questions used to assess this exposure; police were not assessed as potential physical violence perpetrators, and intimate partners were not assessed as potential sexual violence perpetrators. Some measurement error may have been introduced by “double counting” a single perpetrator in multiple roles, for example, clients may over time transition into intimate partner and pimp roles (Karandikar & Próspero, 2010). Some FSW may have experienced one incident of violence from a client-cum-intimate partner and based on this one incident reported having experienced both client violence and IPV. Some participants may not have ever been at risk of pimp violence if they have never worked with a pimp, which affects the degree to which they were at risk of polyvictimization compared with participants who have ever worked with a pimp. Future work to understand patterns of polyvictimization among FSW who work with pimps as compared with those who do not would be valuable.

Conclusion

We found that polyvictimization is common and almost never occurs without client violence, and that IPV, pimp violence, and police violence rarely co-occur unless client violence is also present. Client violence was strongly associated with intimate partner, pimp, and police violence, even after adjusting for a range of other factors. Although the cross-sectional nature of the survey precludes conclusions of causality, these striking patterns raise intriguing hypotheses around the centrality of client violence in polyvictimization in this setting. It also raises potential implications for how violence and HIV interventions should be targeted and structured, including adding a focus on client violence to prevention and response interventions for other types of violence. This study is one of the first to explicitly take a polyvictimization lens with FSW, though such scholarship is increasing (Coetzee et al., 2017). Compared with the general population of women, for whom IPV is the most common type of violence experienced, FSW face a unique pattern of polyvictimization in which they are exposed to client violence, police violence, and pimp violence in addition to IPV. Violence research specifically with this underserved and highly polyvictimized population is critical, particularly because these accumulating sources of trauma not only impinge on their human rights but also multiply HIV risk and other health issues in this population (Decker, Crago, et al., 2014). As more research with FSW include assessments for multiple types of violence, a better understanding of polyvictimization and patterns of violence co-occurrence across settings will emerge, supporting the development of evidence-based interventions tailored to the needs of this key population.

Acknowledgments

We thank the female sex workers who participated in this study, Svetlana Sadretdinova and her team at the Simona Clinic (Kazan, Russia), Marina Malisheva and Julia Burdina and their team at the Krasnyi Yar program (Krasnoyarsk, Russia), and Nadezhda Ziryanova and Anna Petrova and their team at the Belaya Siren Project (Tomsk, Russia). We also thank TuQuynh K. Le for her assistance designing and creating Figure 1.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Global Fund (Open Health Institute). Research reported in this publication was supported by NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number F31 DA040558. This publication resulted in part from research supported by the Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research, an NIH funded program (P30AI094189), which is supported by the following NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, FIC, NIGMS, NIDDK, and OAR. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Biographies

Sarah M. Peitzmeier, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow with the Center for Sexuality and Health Disparities at the School of Nursing, University of Michigan. Her research interests focus on violence and sexual health in marginalized populations.

Andrea L. Wirtz, PhD, is an epidemiologist in the Center for Public Health and Human Rights and Department of Epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Her research interests focus on the epidemiology of violence and HIV and implementation science to prevent and respond to these health outcomes.

Chris Beyrer, MD, is a professor in the Department of Epidemiology and the director of the Center for Public Health and Human Rights at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. He is the Immediate Past President of the International AIDS Society.

Alena Peryshkina is the founding director of the Moscow-based nongovernmental organization, AIDS Infoshare, which aims to provide evidence-based HIV prevention and care information within the Russian Federation. She oversees the coordination of the local Eastern Europe and Central Asia AIDS Conference and has collaborated with Johns Hopkins University to implement multiple HIV research studies among key populations in the Russian Federation.

Susan G. Sherman, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Health, Behavior and Society at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Her work focuses on the structural determinants of HIV, overdose, and violence among street-based female sex workers and people who use drugs.

Elizabeth Colantuoni, PhD, is a faculty member in the Department of Biostatistics at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Her research interests focus on the design and analysis of clustered or longitudinal studies of health, with special interest in critical illness and Alzheimer’s disease, as well as patient safety.

Michele R. Decker, ScD, is an associate professor in the Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. She directs the Women’s Health and Rights Program of the Center for Public Health and Human Rights. A social epidemiologist by training, her research focuses on gender-based violence (e.g., sexual assault, intimate partner violence, sex trafficking), its prevention, and its implications for sexual and reproductive health (e.g., sexually transmitted infections [STI]/HIV, unintended pregnancy).

Appendix

Table A1.

Multivariate Models for Client, Police, Intimate Partner, and Pimp Violence Outcomes in a Sample of Russian Female Sex Workers (N = 754).

| Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Client Violence ARR (95% CI) | Police Violence ARR (95% CI) | IPV ARR (95% CI) | Pimp Violence ARR (95% CI) | |

| Client violence | — | 2.66 [1.57, 4.50] *** | 3.41 [1.86, 6.28] *** | 5.48 [2.90, 10.34] *** |

| Police violence | 1.54 [1.12, 2.19] * | — | 1.43 [0.95, 2.14] | 1.22 [0.88, 1.69] |

| IPV | 1.75 [1.26, 2.44] ** | 1.24 [0.86, 1.78] | — | 1.14 [0.78, 1.68] |

| Pimp violence | 1.94 [1.54, 2.43] *** | 1.35 [1.07, 1.71] * | 1.25 [0.87, 1.79] | — |

| Injecting drug use | 1.63 [1.04, 2.45] * | 1.22 [0.76, 1.96] | 1.68 [1.00, 2.80] * | 0.64 [0.37, 1.11] |

| Age | 0.99 [0.94, 1.04] | 0.96 [0.92, 1.01] | 0.98 [0.90, 1.08] | 1.04 [0.96, 1.12] |

| Any street sex work | 1.05 [0.80, 1.37] | 1.24 [0.74, 2.09] | 1.16 [0.78, 1.72] | 1.13 [0.57, 2.26] |

| Average number of sex partners per nighta | 1.09 [0.90, 1.32] | 0.88 [0.77, 1.01] | 1.07 [0.92, 1.24] | 1.00 [0.83, 1.21] |

| Other income besides sex work | 1.20 [0.96, 1.51] | 0.80 [0.48, 1.34] | 1.01 [0.92, 1.24] | 0.39 [0.17, 0.88] * |

| Current number of intimate partnersb | 0.84 [0.64, 1.11] | 1.25 [0.90, 1.72] | 1.65 [1.18, 2.31] ** | 0.94 [0.62, 1.43] |

| Sex work durationc | 1.04 [0.95, 1.14] | 1.56 [1.24, 1.95] *** | 1.08 [0.79, 1.45] | 1.23 [1.02, 1.49] * |

| Education | 0.86 [0.72, 1.01] | 0.97 [0.75, 1.25] | 1.11 [0.88, 1.40] | 0.89 [0.58, 1.36] |

| Age of entry | 0.94 [0.89, 1.00] * | 1.06 [0.99, 1.15] | 0.98 [0.88, 1.09] | 0.96 [0.89, 1.03] |

| Relationship | ||||

| Never married | — | — | — | — |

| Dating someone | 2.08 [1.51, 2.83] *** | 0.72 [0.50, 1.05] | 0.67 [0.40, 1.12] | 0.97 [0.63, 1.50] |

| Living together | 1.76 [1.23, 2.52] ** | 0.66 [0.39, 1.12] | 1.00 [0.59, 1.67] | 0.83 [0.51, 1.35] |

| Legally married or widowed | 0.87 [0.46, 1.62] | 1.19 [0.62, 2.28] | 1.58 [0.74, 3.39] | 0.23 [0.03, 1.96] |

| Divorced or separated | 2.13 [1.51, 3.01] *** | 0.55 [0.28, 1.05] | 1.15 [0.53, 2.51] | 0.50 [0.19, 1.31] |

| Monthly salary in 1,000 rubles | 1.01 [1.00, 1.01] *** | 0.99 [0.98, 1.01] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.01] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.01] |

Note. Models correspond to Table 4, Model 2. ARR = adjusted relative risk; CI = confidence interval; IPV = intimate partner violence.

Average number of vaginal or anal sex partners. Ordered categorical variable with response options 0, 1, 2, 3, or more than 3.

Ordered categorical variable with response options 0, 1, or 2 or more.

Ordered categorical variable with response options 6 months or less, 6 months to 1 year, 1 to 2 years, 2 to 3 years, 3 to 4 years, and more than 4 years.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

All bold values are p < 0.05

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Beattie TS, Bhattacharjee P, Ramesh B, Gurnani V, Anthony J, Isac S, … Bradley J (2010). Violence against female sex workers in Karnataka state, south India: Impact on health, and reductions in violence following an intervention program. BMC Public Health, 10(1), Article 476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie TS, Isac S, Bhattacharjee P, Javalkar P, Davey C, Raghavendra, … Blanchard JF (2016). Reducing violence and increasing condom use in the intimate partnerships of female sex workers: Study protocol for Samvedana plus, a cluster randomised controlled trial in Karnataka state, South India. BMC Public Health, 16(1), Article 660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beksinska A, Prakash R, Isac S, Mohan H, Platt L, Blanchard J, … Beattie TS (2018). Violence experience by perpetrator and associations with HIV/STI risk and infection: A cross-sectional study among female sex workers in Karnataka, South India. BMJ Open, 8(9), e021389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyrer C, Wirtz AL, O’Hara G, Léon N, & Kazatchkine M (2017). The expanding epidemic of HIV-1 in the Russian Federation. PLoS Medicine, 14(11), e1002462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson CE, Chen J, Chang M, Batsukh A, Toivgoo A, Riedel M, & Witte SS (2012). Reducing intimate and paying partner violence against women who exchange sex in Mongolia results from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 1911–1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury SM, Anglade D, & Park K (2013). From violence to sex work: Agency, escaping violence, and HIV risk among establishment-based female sex workers in Tijuana, Mexico. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 24, 368–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark F (2016). Gaps remain in Russia’s response to HIV/AIDS. The Lancet, 388, 857–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clopper CJ, & Pearson ES (1934). The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika, 26, 404–413. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee J, Gray G, & Jewkes R (2017). Prevalence and patterns of victimization and polyvictimization among female sex workers in Soweto, a South African township: A cross-sectional, respondent-driven sampling study. Global Health Action, 10(1), 1403815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (2010). Praised Russian prevention program faces loss of funds. Science, 329, 168–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MR, Crago A-L, Chu SK, Sherman SG, Seshu MS, Buthelezi K, … Beyrer C (2014). Human rights violations against sex workers: Burden and effect on HIV. The Lancet, 385, 186–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MR, McCauley HL, Phuengsamran D, Janyam S, Seage GR, & Silverman JG (2010). Violence victimisation, sexual risk and sexually transmitted infection symptoms among female sex workers in Thailand. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 86, 236–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MR, Pearson E, Illangasekare SL, Clark E, & Sherman SG (2013). Violence against women in sex work and HIV risk implications differ qualitatively by perpetrator. BMC Public Health, 13(1), Article 876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MR, Wirtz AL, Baral SD, Peryshkina A, Mogilnyi V, Weber RA, … Beyrer C (2012). Injection drug use, sexual risk, violence and STI/HIV among Moscow female sex workers. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 88, 278–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MR, Wirtz AL, Moguilnyi V, Peryshkina A, Ostrovskaya M, Nikita M, … Beyrer C (2014). Female sex workers in three cities in Russia: HIV prevalence, risk factors and experience with targeted HIV prevention. AIDS and Behavior, 18, 562–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deering KN, Amin A, Shoveller J, Nesbitt A, Garcia-Moreno C, Duff P, … Shannon K (2014). A systematic review of the correlates of violence against sex workers. American Journal of Public Health, 104(5), e42–e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsberg M, Arango DJ, Morton M, Gennari F, Kiplesund S, Contreras M, & Watts C (2014). Prevention of violence against women and girls: What does the evidence say? The Lancet, 385, 1555–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erausquin JT, Reed E, & Blankenship KM (2011). Police-related experiences and HIV risk among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 204(Suppl. 5), S1223–S1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti M, Vincent J, Anda M, Robert F, Nordenberg M, Williamson M, … Edwards B (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, & Turner HA (2009). Lifetime assessment of polyvictimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R, & Hamby SL (2009). Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics, 124, 1411–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, & Watts CH (2006). Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. The Lancet, 368, 1260–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L, Raj A, Hien D, Stockman J, Terlikbayeva A, & Wyatt G (2015). Targeting the SAVA (substance abuse, violence, and AIDS) syndemic among women and girls: A global review of epidemiology and integrated interventions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 69, S118–S127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg SM, Rangel G, Vera A, Patterson TL, Abramovitz D, Silverman JG, … Strathdee SA (2012). Exploring the impact of underage sex work among female sex workers in two Mexico–US border cities. AIDS and Behavior, 16, 969–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J, Reed E, Kershaw T, & Blankenship KM (2011). History of sex trafficking, recent experiences of violence, and HIV vulnerability among female sex workers in coastal Andhra Pradesh, India. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 114, 101–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD (1997). Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems, 44, 174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson CA (2014). Being an academic ally: Gender justice for sex workers. In White MK, White JM, & Korgen KO (Eds.), Sociologists in Action on Inequalities: Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality (pp. 109–112). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Karandikar S, & Próspero M (2010). From client to pimp male violence against female sex workers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 257–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang DL, Salazar LF, DiClemente RJ, & Markosyan K (2013). Gender based violence as a risk factor for HIV-associated risk behaviors among female sex workers in Armenia. AIDS and Behavior, 17, 551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law SA (1999). Commercial sex: Beyond decriminalization. Southern California Law Review, 73, 523. [Google Scholar]

- Lesur M, Stelmaszek B, & Golden I (2014). Country report 2013: Reality check on European services for women and children survivors of violence. Vienna, Australia. Retrieved from https://www.wave-network.org/resources/research-reports [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Peitzmeier S, Cange C, Papworth E, LeBreton M, Tamoufe U, … Njindam I (2015). Violence against female sex workers in Cameroon: Accounts of violence, harm reduction, and potential solutions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 68, S241–S247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JP, Springer SA, & Altice FL (2011). Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: A literature review of the syndemic. Journal of Women’s Health, 20, 991–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musicaro RM, Spinazzola J, Arvidson J, Swaroop SR, Goldblatt Grace L, Yarrow A, … Ford JD (2017). The complexity of adaptation to childhood polyvictimization in youth and young adults: Recommendations for multidisciplinary responders. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 20, 81–98. doi: 10.1177/1524838017692365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odinokova V, Rusakova M, Urada LA, Silverman JG, & Raj A (2014). Police sexual coercion and its association with risky sex work and substance use behaviors among female sex workers in St. Petersburg and Orenburg, Russia. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25(1), 96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchanadeswaran S, Johnson SC, Sivaram S, Srikrishnan AK, Latkin C, Bentley ME, … Celentano D (2008). Intimate partner violence is as important as client violence in increasing street-based female sex workers’ vulnerability to HIV in India. International Journal of Drug Policy, 19, 106–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokrovskiy V, Ladnaya N, Tushina O, & Buravtsova E (2015). ВИЧ-Инфекция. Информационный бюллетень №40 [HIV-infection. Informational bulletin #40]. Moscow, Russia. Retrieved from http://www.hivrussia.ru/files/bul_40.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ratinthorn A, Meleis A, & Sindhu S (2009). Trapped in circle of threats: Violence against sex workers in Thailand. Health Care for Women International, 30, 249–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reza-Paul S, Lorway R, O’Brien N, Lazarus L, Jain J, Bhagya M, … Baer J (2012). Sex worker-led structural interventions in India: A case study on addressing violence in HIV prevention through the Ashodaya Samithi collective in Mysore. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 135(1), 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, & Csete J (2010). Violence, condom negotiation, and HIV/STI risk among sex workers. Journal of the American Medical Association, 304, 573–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, Montaner JS, … Tyndall MW (2009). Prevalence and structural correlates of gender based violence among a prospective cohort of female sex workers. British Medical Journal, 339, 442–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, Duff P, Mwangi P, Rusakova M, & Pickles MR (2015). Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: Influence of structural determinants. The Lancet, 385, 55–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, Rusch M, Kerr T, & Tyndall MW (2009). Structural and environmental barriers to condom use negotiation with clients among female sex workers: Implications for HIV-prevention strategies and policy. American Journal of Public Health, 99, 659–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkov D (2016, March 17). Prostitution surges in Russia in wake of financial crisis: A report. Newsweek. Retrieved from https://www.newsweek.com/prostitution-russia-surges-after-financial-crisis-report-437869 [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, Footer K, Illangasekare S, Clark E, Pearson E, & Decker MR (2015). “What makes you think you have special privileges because you are a police officer?” A qualitative exploration of police’s role in the risk environment of female sex workers. AIDS Care, 27, 473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A (2012). Criminalizing condoms: How policing practices put sex workers and HIV services at risk in Kenya, Namibia, Russia, South Africa, the United States, and Zimbabwe. New York, NY: Open Society Foundations. [Google Scholar]

- Silver Rose. (2016). Submission for the committee on economic, social and cultural rights on the implementation of the international covenant on economic, social and cultural rights in the Russian Federation with regards to sex worker population: Alternative report. Retrieved from https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CESCR/Shared%20Documents/RUS/INT_CESCR_ICO_RUS_26447_E.pdf

- Silver Rose. (2017). Основы безопасности секс-работниц [The basics of sex worker safety]. St. Petersburg, Russia. Retrieved from http://www.swannet.org/en/content/safety-guide-sex-workers-russia [Google Scholar]

- Singer M (1996). A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: Conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology, 24, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon F (2017, February 8). Vladimir Putin just signed off on the partial decriminalization of domestic abuse in Russia. Time. Retrieved from http://time.com/4663532/russia-putin-decriminalize-domestic-abuse/ [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, Greenwood G, Paul J, … Catania JA (2003). Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 939–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Crago A-L, Butler J, Bekker L-G, & Beyrer C (2015). Dispelling myths about sex workers and HIV. The Lancet, 385, 4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, & Sugarman DB (1996). The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17, 283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Swain SN, Saggurti N, Battala M, Verma RK, & Jain AK (2011). Experience of violence and adverse reproductive health outcomes, HIV risks among mobile female sex workers in India. BMC Public Health, 11(1), Article 357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szwarcwald CL, de Souza Júnior PRB, Damacena GN, Junior AB, & Kendall C (2011). Analysis of data collected by RDS among sex workers in 10 Brazilian cities, 2009: Estimation of the prevalence of HIV, variance, and design effect. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 57, S129–S135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulibarri MD, Salazar M, Syvertsen JL, Bazzi AR, Rangel MG, Orozco HS, & Strathdee SA (2018). Intimate partner violence among female sex workers and their noncommercial male partners in Mexico: A mixed-methods study. Violence Against Women, 25, 549–571. doi: 10.1177/1077801218794302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulibarri MD, Strathdee SA, Ulloa EC, Lozada R, Fraga MA, Magis-Rodríguez C, … Patterson TL (2011). Injection drug use as a mediator between client-perpetrated abuse and HIV status among female sex workers in two Mexico-US border cities. AIDS and Behavior, 15(1), 179–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of State. (2014). International narcotics control strategy report. Retrieved from http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/222881.pdf