Abstract

Background

Romania is one of the European countries reporting very high antimicrobial resistance (AMR) rates and consumption of antimicrobials. We aimed to characterize the AMR profiles and clonality of 304 multi-drug resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter baumannii (Ab) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pa) strains isolated during two consecutive years (2018 and 2019) from hospital settings, hospital collecting sewage tanks and the receiving wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) located in the main geographical regions of Romania.

Methods

The strains were isolated on chromogenic media and identified by MALDI-TOF-MS. Antibiotic susceptibility testing and confirmation of ESBL- and CP- producing phenotypes and genotypes were performed. The genetic characterization also included horizontal gene transfer experiments, whole-genome sequencing (WGS), assembling, annotation and characterization.

Results

Both clinical and aquatic isolates exhibited high MDR rates, especially the Ab strains isolated from nosocomial infections and hospital effluents. The phenotypic resistance profiles and MDR rates have largely varied by sampling point and geographic location. The highest MDR rates in the aquatic isolates were recorded in Galați WWTP, followed by Bucharest. The Ab strains harbored mostly blaOXA-23, blaOXA-24, blaSHV, blaTEM and blaGES, while Pa strains blaIMP, blaVIM, blaNDM, blaVEB, blaGES and blaTEM, with high variations depending on the geographical zone and the sampling point. The WGS analysis revealed the presence of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) to other antibiotic classes, such as aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, sulphonamides, fosfomycin, phenicols, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as well as class 1 integrons. The molecular analyses highlighted: (i) The presence of epidemic clones such as ST2 for Ab and ST233 and ST357 for Pa; (ii) The relatedness between clinical and hospital wastewater strains and (iii) The possible dissemination of clinical Ab belonging to ST2 (also proved in the conjugation assays for blaOXA-23 or blaOXA-72 genes), ST79 and ST492 and of Pa strains belonging to ST357, ST640 and ST621 in the wastewaters.

Conclusion

Our study reveals the presence of CP-producing Ab and Pa in all sampling points and the clonal dissemination of clinical Ab ST2 strains in the wastewaters. The prevalent clones were correlated with the presence of class 1 integrons, suggesting that these isolates could be a significant reservoir of ARGs, being able to persist in the environment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13756-022-01156-1.

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, Nonfermenting gram-negative Bacilli, Nosocomial infections, Wastewater, Epidemic clones

Background

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is an increasing worldwide concern. Romania is one of the European countries reporting elevated AMR rates and the country with the third highest consumption of antibacterials for systemic use in the community sector (according to data from 2020) [1]. Antibiotics are one of the most popular pharmaceuticals used in human medicine, veterinary care, and farming [2–4]. Unfortunately, antibiotics are also frequent contaminants in domestic wastewater, municipal sewage and wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluents from where they dissipate into the environment [5–7]. Hospitals generate huge amounts of wastewater daily, high in pathogenic microorganisms, antibiotics and other pharmaceutical or toxic substances, discharged in urban wastewater systems. Hospital wastewaters, coupled with urban, industrial etc. wastewaters reach the WWTPs turning them in key sources of both antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) and antibiotic resistant genes (ARGs). ARGs are disseminated via mobile genetic elements (MGEs) to other non-resistant bacterial strains [8–10] during wastewater treatment. The WWTPs standard procedures only partially remove ARGs, ARBs and other resilient pollutants. The remaining contaminants are contributing to the pollution of the natural environments, facilitating the selection and dissemination of ARGs and ARB [7, 11–13] into crops, animals, and humans, from which they could be (re)introduced into the medical environment [14]. Also, the ARGs can be transmitted to the aquatic microbiota via horizontal gene transfer (HGT), being increased in natural environment bacterial biofilms and under pharmaceutical and heavy metal contamination induced stress [15].

The lack of surveillance of non-clinical reservoirs is considered one of the main contributors to the spread of AMR, particularly in developing countries. In this context, during the last few years, international authorities have made considerable efforts to improve the monitoring of AMR in different environments, underlining the necessity to strengthen intersectoral human, animal, and agricultural cooperation. One of the priority topics of The Joint Programme Initiative on Antimicrobial Resistance (JPIAMR) is represented by the elucidation of the role of the environment as a source for the selection and dissemination of AMR. One important goal is mapping the distribution of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens and plasmids of different genomic lineages in different clinical and aquatic compartments. This important insight could be translated into policy measures to monitor AMR and control the emergence and spread of ARB [16, 17].

Acinetobacter baumannii (Ab) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pa) are members of the initially designed “ESKAPE”, then “ESCAPE” (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus; Clostridioides difficile, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacteriaceae) group [18, 19]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classified them urgent threat due to their often MDR features [20] and therefore requiring concerted research and management efforts [21]. Ab and Pa exhibit all known AMR mechanisms, such as drug inactivation/alteration, modification of drug binding sites/targets, cell permeability modification and biofilm development [22]. One of the most clinically relevant mechanisms of resistance in Ab and Pa strains is represented by the production of antibiotic inactivating hydrolytic enzymes, especially carbapenemases (CPs).

So far, five main groups of acquired chromosomal or plasmid located class D β-lactamases (CHDLs) with different geographic distribution have been identified in Ab strains, i.e., OXA-23, OXA-24/-40, OXA-58, OXA-143 and OXA-235 [23]. In Pa strains, there were identified eleven families of class B metallo-β-lactamases (MBL) [Verona integron-encoded MBL (VIM); imipenemases (IMPs); New Delhi MBL (NDM); Australian imipenemase (AIM); Central Alberta MBL (CAM); Dutch imipenemase (DIM); Florence imipenemase (FIM); German imipenemase (GIM); Hamburg MBL (HMB); São Paulo MBL (SPM) and Seoul imipenemase (SIM)], chromosomal/plasmid encoded or integron-borne, the VIM, IMP and NDM types being distributed worldwide [24].

Presently, there is insufficient data on the Ab and Pa dissemination and survival from hospitals in wastewater and finally into the natural recipients. Despite the huge burden of AMR presence in Romania and its significant overall impact on European AMR rates, the genetic relationships between the bacterial strains isolated from different aquatic environmental and clinical compartments were not investigated at a national level.

We aimed to perform a phenotypic and molecular characterization of the acquired resistome of a significant number of MDR Ab and Pa strains isolated in the same temporal sequence from the hospital environments and the receiving wastewater network from different counties in Romania.

Methods

Phenotypic characterization of the Ab and Pa strains

Sampling location

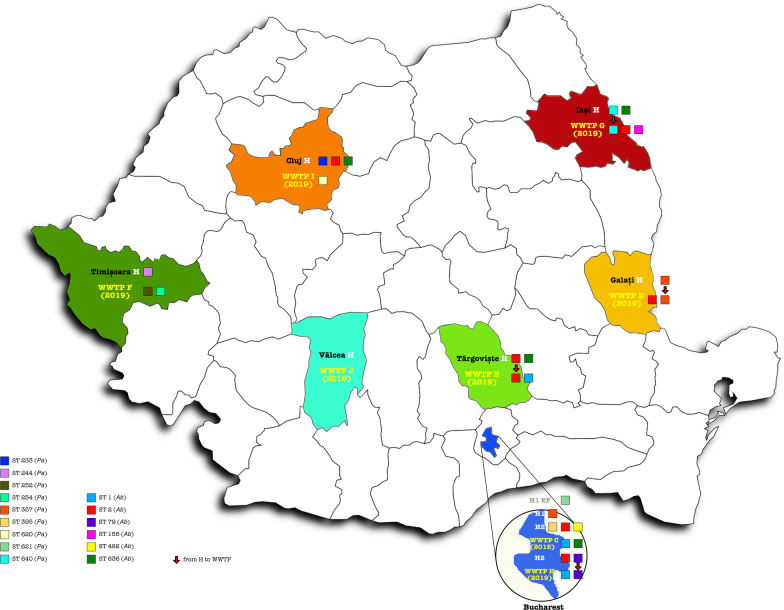

Water sampling was performed from September 2018 to August 2019. The collection points were represented by sewage tanks from eight hospital units and their wastewater collecting WWTPs. The eight sampling locations covered several Romanian regions such as the Southern region, with sampling locations in Bucharest (C/H—Glina municipal WWTP 2018/2019), WWTP Târgoviște (E) and WWTP Râmnicu-Vâlcea (J); Central and Western regions: WWTP Cluj (I) and WWTP Timișoara (F); Northern and Eastern regions: WWTP Iași (G) and WWTP Galați (D) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Geographic distribution of the sampling points

The different sampling points from the selected locations were: hospital/WWTP effluent (EF), WWTPs influent (IN), activated sludge (AS) and returned sludge (RS), where all isolated strains were considered within a single group.

Isolation and characterization of Ab and Pa strains

The water samples were collected in sterile glass containers, transported to the laboratory at 5 ± 3 °C and processed within the first 24 h. The water samples were diluted and filtered through 0.45 μm pore size membrane filters (Millipore, France), as described in SR EN ISO 9308–2/2014 (for coliform bacteria) and then cultivated on ChromID ESBL agar and ChromID CARBA agar (BioMérieux, France). The resistant colonies developed after cultivation at 37 °C for 24 h in aerobic conditions were subsequently inoculated on the corresponding antibiotic-enriched media for the confirmation of ESBL-(ChromID ESBL) or CP- (ChromID CARBA) producing phenotypes. All resistant strains were identified by MALDI-TOF-MS (Bruker system). In the same time frame with the collection of the water samples (i.e., during a ten-day period prior to the water sampling), Ab and Pa clinical strains were isolated from intra-hospital infections that occurred in the units discharging the wastewater in the sampled WWTPs.

The antibiotic susceptibility profiles of the identified strains (220 Ab and 84 Pa), were determined using the standard disc diffusion method according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI guidelines) for 2018 and 2019 [25, 26] (see Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2).

PCR for ESBL and CP genes

The strains were screened for CP (blaVIM, blaIMP, blaNDM, blaKPC for Pa), and blaOXA-51/69-like, blaOXA-23-like, blaOXA-24-like, blaOXA-58-like, blaOXA-143, blaOXA-235, blaNDM genes in the case of Ab strains) and ESBL encoding genes (blaCTX-M, blaTEM, blaSHV, blaPER, blaVEB, blaGES for strains belonging to both species) using previously described primers and PCR protocols [27, 28].

Mating experiments

Transferability of blaOXA-23 and blaOXA-24 genes by conjugation was tested using the solid mating method, with rifampicin (RIF) resistant Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1 as recipient. Briefly, equal amounts (100 µL) of overnight cultures of the donors (n = 40 Ab strains from all isolation sampling points) and recipient strains were mixed and incubated in Brain heart infusion agar plates. Cells were resuspended in saline solution and selected in plates containing RIF (300 mg/L) and meropenem (MEM) (0.5 mg/L) [29]. Characterization of the transconjugants was conducted by PCR.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS), assembling, annotation and characterization

To determine the genetic relationships between the clinical and wastewater isolates, 54 strains (Ab, n = 34 and Pa, n = 20) were selected for WGS based on the isolation source, geographical region, temporal sequence and the presence of MDR phenotype in order to have a complete picture of the antibiotic resistance in different Romanian regions. Total DNA was isolated using DNeasy UltraClean Microbial Kit (Qiagen) and subjected to Illumina (Nextera DNA Flex Library Prep Kit) sequencing on a MiSeq platform (V3, 600 cycles). The sequencing quality was very good (with an average of 88% over Q30 and 95% over Q20 for Ab (78% over Q30 and 89% over Q20 for Pa), and an average of 1.53 million reads per sample for Ab and 1.66 million reads per sample for Pa. Raw reads were checked for quality using FastQC v0.18.8 [30], assembled using Shovill v1.1.0 pipeline [31] and primarily annotated using Prokka v.1.14.6 [32], while the prediction of resistance profiles was performed by using ABRicate v0.5 [33], ResFinder, PlasmidFinder v2.1.1 [34–37], PathogenFinder [38], CARD [39]. Strain relatedness was investigated using MultiLocus Sequence Typing (MLST v2.9) [35, 40] and Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) (v3.1) [41]. Comparative gene analyses were performed using Roary v.3.13.0 [42] and the output was used to infer phylogenies using RAxML v8.2.12 (Maximum Likelihood inference using bootstrap value N = 1000) [43] and visualized using iTOL [44]. The assembled sequences have been deposited in GenBank with BioProject ID PRJNA841266.

The 34 selected Ab WGS assemblies were subjected to phylogenetic analysis to further attain their relationship to other Ab strains from the NCBI database. For this, all Ab sequences available (n = 4175) were downloaded from NCBI and from those, 71 were randomly selected. MLST predictions and annotations were performed on this dataset and, together with the 34 selected strains, were subjected to further pangenome analysis using Roary and aligned with Mafft v.7.741. The resulted phylogenetic tree was drawn with FigTree v.1.4.4 and the final form of the supplementary image was then represented using Affinity Designer v.1.10.5.

Results

Identification and antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Ab and Pa strains

A total number of 220 Ab and 84 Pa were isolated from clinical and water samples during the two consecutive years.

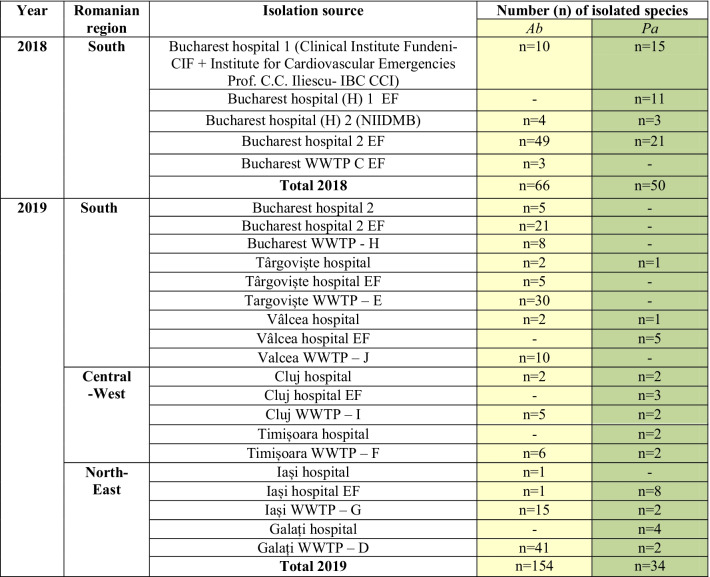

Two pilot sampling campaigns were performed in Bucharest in 2018 from which 66 Ab and 50 Pa strains were isolated (Table 1).

Table 1.

The distribution of Ab and Pa strains selected for this study

In 2019, the sampling campaign was extended, including, in addition to Bucharest, six other cities that are representative of the main country regions, i.e., North-East (Iași, Galați), Central-West (Cluj, Timișoara) and South (Târgoviște, Râmnicu Vâlcea). A total of 154 Ab and 34 Pa resistant isolates were recovered (Table 1).

Within the same time frame, clinical Ab and Pa clinical strains were isolated in hospital units from which wastewater samples were collected. The hospital wastewater was collected and treated by the corresponding WWTPs from the same town.

The analysis of MDR rates from the hospital to the collecting WWTP in the first sampling campaign in 2018 has revealed the following aspects: (1) clinical isolates—all Ab and the majority of Pa strains (93.3–100%) were MDR (Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2); (2) hospital EF—all Ab isolates were MDR (Additional file 1: Table S1), while the Pa strains exhibited various MDR rates (from 25 to 100%) (Additional file 1: Table S2); (3) WWTP C, collecting the two hospital EFs—all Ab isolates were MDR (Additional file 1: Table S1).

In 2019, the MDR rates from hospital to the collecting WWTP were as follows: (1) clinical isolates—with one exception, all Ab isolates were MDR (Additional file 1: Table S1), while the Pa strains expressed a high variation of MDR rate (from 0 to 100%) within and between the geographical locations (Additional file 1: Table S2); (2) hospital EF – all Ab isolates were MDR (Additional file 1: Table S1), while the Pa strains exhibited various MDR rates (from 0 to 100%) (Additional file 1: Table S2); (3) WWTPs, collecting the sewages of the sampled hospital units effluents—the MDR resistance rates varied from 0 to 100% for both Ab and Pa strains.

CP and ESBL encoding genes in clinical and environmental Ab and Pa strains

Profiles of CP and ESBL genes from the clinical to the aquatic environment in 2018 versus 2019

The Ab strains from the clinical settings to the WWTP effluent and receiving river exhibited different profiles of CP and ESBLs in the two consecutive years, i.e.: (1) clinical strains—Ab strains recovered in 2018 were OXA-23 and OXA-24 producers (64.28/42.85%) and only 7.14% were positive for blaTEM, while in 2019, 41.66% of all intra-hospital Ab strains were OXA-23 and OXA-24 producers, 25% were positive for blaSHV, 16.66% for blaVIM and blaVEB and 8.33% for blaTEM and blaGES (Additional file 1: Table S1); (2) hospital sewage—the identified carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamases (CHLDs) were represented in the two consecutive years by OXA-23 (67.34/96.29%) and OXA-24 (2.04/0%), MBLs by VIM (4.08/14.81%) and ESBLs by TEM (20.41/0%), SHV and PER (each one 0/3.70%), GES (0/18.51%) (Additional file 1: Table S1); (3) WWTPs—some of the enzymes were common for the strains isolated in 2018 and 2019 [i.e. OXA-24 (57.14/10.25%); OXA-23 (42.85/53.84%); TEM (28.57/10.89%); SHV (14.28/0.64%)], while some other were different [i.e. NDM in Ab strains from 2018 (14.28%) and GES (19.87%); VEB (8.97%); CTX-M (2.56%) and PER (0.64%) in 2019].

The CP and ESBL genes identified in the Pa strains isolated among the transmission chain from the clinical sector to the WWTP effluent and receiving river in the two consecutive years were the following: (1) clinical strains—the Pa strains were positive for blaIMP (66.66/0%), blaVIM (33.33/20%) and blaVEB (38.88/30%); (2) hospital sewage—in the two consecutive years the following MBLs were identified in the Pa strains: VIM (9.37/18.75%); IMP (9.37/0%); NDM (0/12.5%); while the ESBLs were represented by GES (6.25/6.25%); VEB (43.75/12.5%) and TEM (0/31.25%); (3) WWTPs—only the Pa strains isolated in 2019 were positive for ESBL encoding genes [blaTEM (16.66%); blaGES and blaVEB (8.33% each)] (Additional file 1: Table S2).

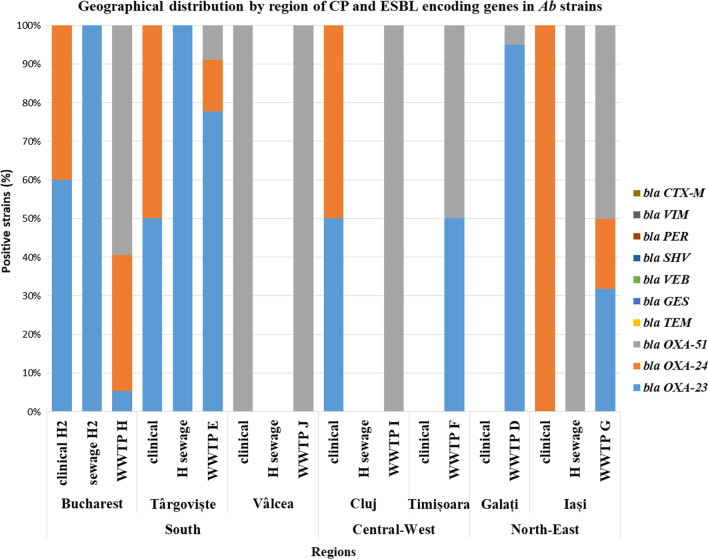

Geographic distribution of CP and ESBL genes in clinical and water Ab and Pa isolates

The 2018 pilot study was limited to the Bucharest region, and then it was extended during 2019 to other regions of the country, allowing us to perform a comparative analysis regarding the geographic distribution of the CP and ESBL encoding genes in the Ab and Pa strains.

Regarding the Ab strains, the isolates from the Southern region expressed the broadest spectrum of CP and ESBL encoding genes, both in clinical [i.e., blaOXA-23 (44.44%); blaOXA-24 (33.33); blaVIM (22.22%); blaTEM and blaSHV (11.11%)] and the aquatic isolates [hospital sewage: blaOXA-23 (100%); blaGES (19.23%); blaVIM (15.38%); blaVEB and blaSHV (3.84%) and WWTPs: i.e. blaOXA-23 (44.44%); blaGES (32.09%); blaTEM (18.51%); blaOXA-24 (14.81%); blaVEB (13.58%); blaCTX-M (4.93%) and blaSHV (1.23%)].

The Ab isolates from the Central-Western region revealed the presence of the following CP and ESBL encoding genes: (1) in clinical settings, all Ab strains were blaVEB positive; 50% were blaOXA-23 and blaOXA-24 positive; (2) the aquatic isolates recovered from the two sampled WWTPs were blaOXA-23 and blaVEB positive (23.07% each of them).

In the North-Eastern region, the CP and ESBL identified in Ab strains from the hospitals to the WWTP were the following: (1) all clinical Ab strains were OXA-24 producers; while in the sampled WWTPs, the Ab strains harbored OXA-23 (72.58%); OXA-24 (6.45%); TEM (3.22%) and PER (1.61%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

CP and ESBL encoding genes in clinical and wastewater Ab from different geographical regions

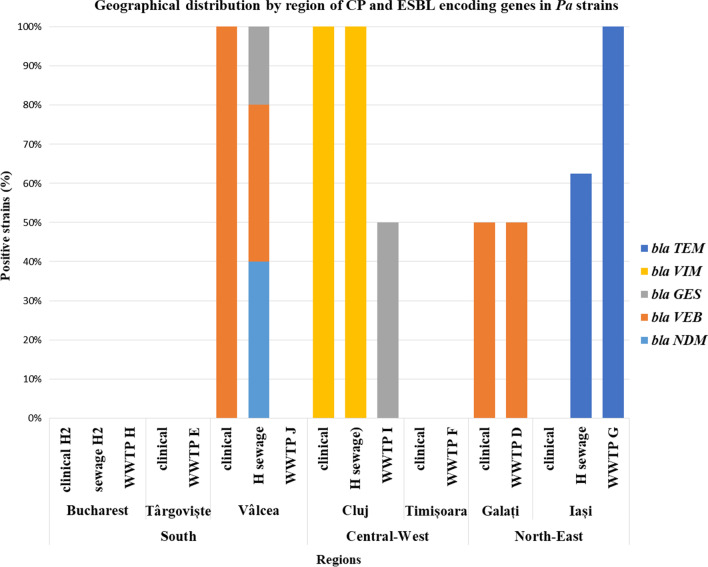

The geographical distribution of the CP/ESBLs found in Pa strains isolated from intra-hospital infections, the hospital sewage tank and the sampled WWTP from the corresponding cities was as follows: in the Southern region, 50% of nosocomial Pa strains were VEB producers, while the wastewater Pa strains harbored blaVEB (40%), blaNDM (40%) and blaGES (20%); in the North-Eastern region, 50% of clinical Pa strains were VEB producers; 62.5% of the hospital sewages strains were positive for blaTEM; 50% respectively 25% of the WWTPs were blaVEB and blaTEM positive. The Pa strains from the Central-Western regions revealed different CP/ESBLs in clinical/hospital sewage (VIM) and in the sampled WWTPs (14.28% were GES positive) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

CP and ESBL encoding genes in clinical and wastewater Pa from different geographical regions

WGS analysis of clinical and wastewater Ab and Pa isolates

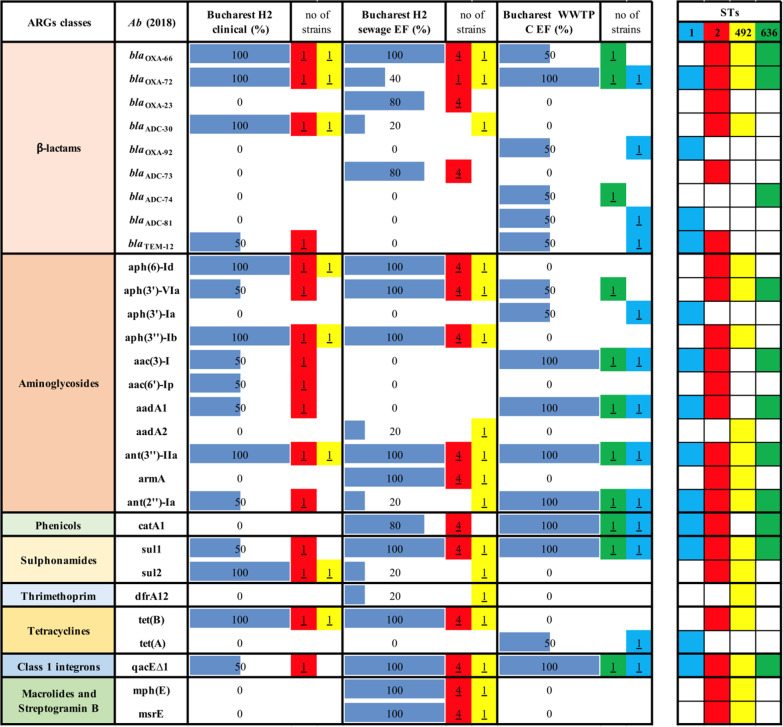

In case of nine Ab strains recovered in 2018 in Bucharest from intra-hospital infections (n = 2), hospital sewage EF (n = 5) and, the corresponding WWTP EF (n = 2) the WGS demonstrated the presence of OXA-72 and OXA-23 encoding genes in the IN and the EF of the collecting sewage tank and of genes encoding aminoglycoside modifying enzymes (AMEs) i.e. aph(3′)-VIa, ant(3″)-IIa, sulphonamides (sul1) and class 1 integrons (qacE∆1 integron-associated gene in 3′ CS region), in all investigated samples (Table 2).

Table 2.

ARGs in clinical and wastewater Ab strains isolated in Bucharest in 2018

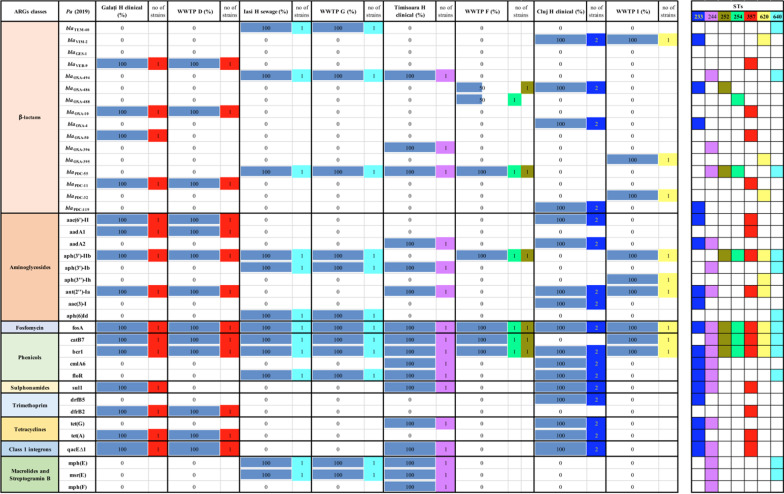

The WGS analysis of 12 Ab clinical strains isolated in 2019 from two hospital units (Bucharest H2 and Târgoviște), the collecting sewage tank of Bucharest hospital 2, and the sampled corresponding WWTPs from Bucharest (H) and Târgoviște (E) revealed the presence of blaOXA-23 in all sampled points from Bucharest. The presence of both blaOXA-23 and blaOXA-72 was shown in clinical Ab strains from Târgoviște hospital unit and in the corresponding WWTP (i.e., blaOXA-23 in EF and blaOXA-72 in the RS) (Additional file 2: Table S3). Similarly, the AMEs (i.e., aph(6)-Id, ant(3″)-IIa), sulphonamides resistance (sul 1) and class 1 integrons (qacE∆1 integron associated gene) were present in all sampled sites from Bucharest. The WGS of nine Ab clinical and wastewater strains from Eastern and Northern Romania revealed a high diversity of ARGs, with differences between different cities, i.e., blaOXA-23, aph(6)-Id, aph(3″)-Ib, armA, sul 1, tet(B), mph(E), msrE and qacE∆ in Galați WWTP (D) and blaOXA-72, aph(3′)-Ia, aac(3)-I, aadA1, ant(2″)-Ia, sul1 and qacE∆1 in Iași WWTP (G) (Additional file 2: Table S3).

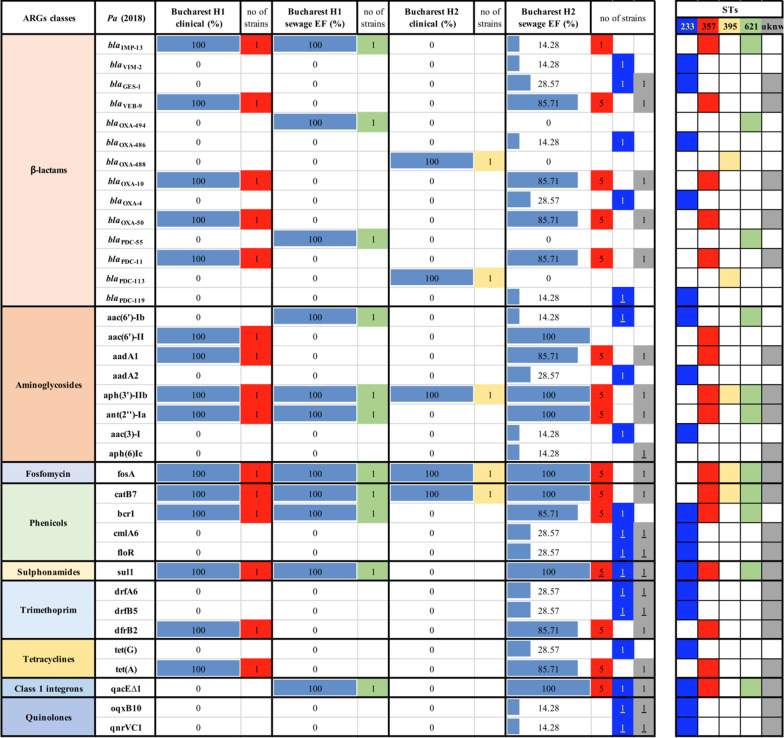

The WGS analysis of the acquired resistome of the 10 Pa strains recovered in 2018 revealed the dissemination of CP blaIMP-13 and genes encoding AMEs (aph(3′)-IIb, ant(2″)-Ia), fosfomycin (fosA), phenicols (catB7, bcr1) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (sul1) resistance genes in strains isolated from one Bucharest hospital and its effluent (Table 3). In the case of the second investigated hospital and the corresponding sewage tank, there has been noticed the presence of genes encoding AMEs (aph(3′)-IIb) and phenicols (catB) (Table 3).

Table 3.

ARGs in clinical and wastewater Pa strains isolated in Bucharest in 2018

The ARGs distribution of four Pa strains, collected from Northern and Eastern Romania in 2019, revealed the presence of ESBL encoding genes (blaTEM-40, blaVEB-9), AMEs encoding genes (aac(6′)-II, aadA1, aph(3′)-IIb) as well as determinants of resistance to fosfomycin (fosA), phenicols (catB7, bcr1), tetracycline [tet(A)] and class 1 integrons (qacE∆1 integron associated gene) in clinical and wastewater samples. Regarding the six Pa clinical and wastewater strains from Central and Western regions of Romania, the presence of resistance genes encoding for fosfomycin (fosA) and phenicols (catB7, bcr1) has been observed in Pa strains from almost all sources (Table 4).

Table 4.

ARGs in clinical and wastewater Pa strains isolated from North-Eastern and Central-Western Romania in 2019

Ab and Pa strains molecular phylogeny

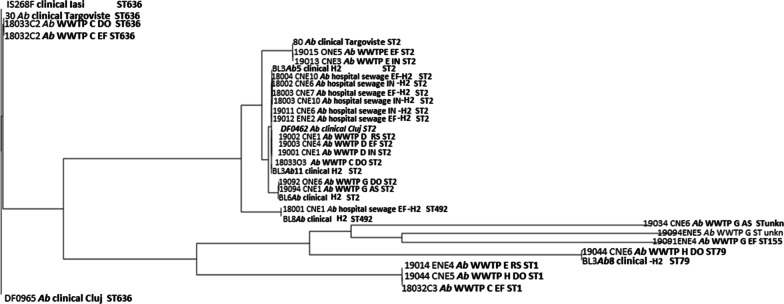

Based on SNP analyses and MLST profiles, the Ab strains were divided in six groups.

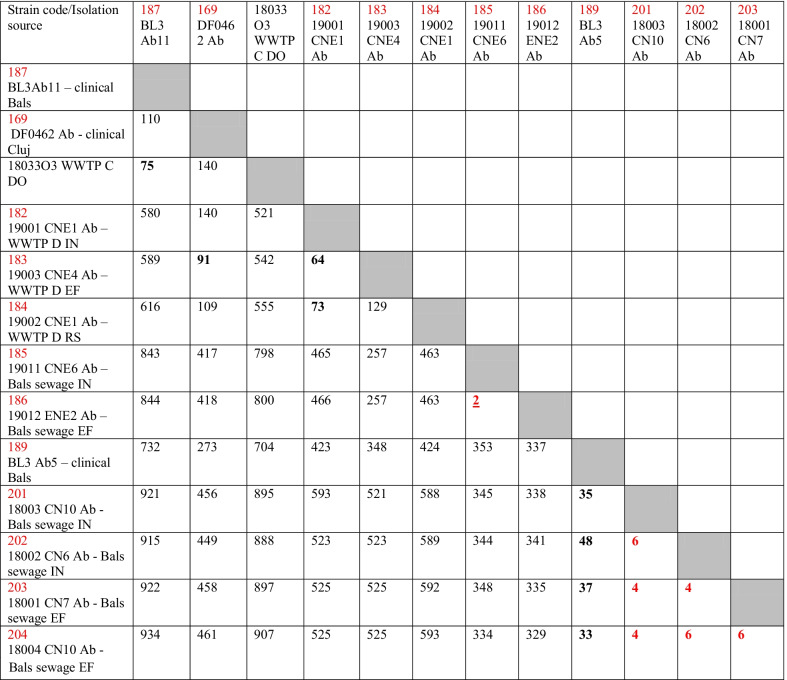

Group I included clinical isolates from Iași, Târgoviște and Cluj and the effluent and downstream of Bucharest WWTP C, belonging to ST636. The SNP analysis suggests the similarity between a clinical isolate sampled in 2019 and two aquatic strains from this group, sampled in 2018 (harboring 51 and, respectively, 60 SNPs); group II included most of the strains (clinical and wastewater isolates from all investigated regions) belonging to ST2, a successful widespread Ab clone. SNP analyses suggest the relatedness between clinical and hospital wastewater strains (189 − 201 + 202 + 203 + 204, thus less than 20 SNPs), and more intriguing, the relatedness between strains sampled in clinics and urban WWTPs (169 − 184 = 15 SNPs, 187 − 18033O3 = 22 SNPs), suggesting the dissemination of the clinical Ab ST2 strains in the wastewaters (Table 5); group III was represented by closely related (26 SNPs) strains isolated from Bucharest hospital and its collecting sewage tank isolates belonging to ST492; group IV included less related (577 SNPs) clinical strains and aquatic strains isolated from Bucharest belonging to ST79; were; group V included less related (> 700 SNPs) wastewater strains isolated from South Romania belonging to ST1; group VI included only environmental strains from the Northern region of the country belonging to ST155 and two related novel STs (Fig. 4).

Table 5.

Matrix representation of calculated SNPs distances between the closely related ST2 A. baumannii strains

Values in red highlights less than 20 SNPs. Values in bold highlight less than 100 SNPs between the related strains

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic tree of clinical and wastewater Ab strains

Pangenome analyses performed on 34 WGS Ab strains and 71 selected genomes from the NCBI database, supported also by conjugation assays revealed clear dissemination of the same circulating clones from the hospital units into different aquatic compartments [i.e., ST2 encountered in Bucharest hospital unit and the corresponding sampled WWTP carrying the same CP encoding gene (blaOXA-23 or blaOXA-72) in Ab strains; ST2 carrying blaOXA-72 gene in Ab strains from Târgoviște hospital unit and blaOXA-23 in the EF of the corresponding WWTP E] and similarities with other international ST2 clones (Additional file 3: Fig. S1).

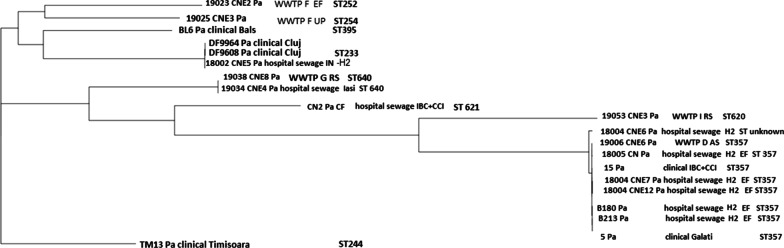

The Pa strains (Fig. 5) were also grouped in six phylogenetic groups: group I included wastewater isolates from Timișoara, and one clinical strain from the Bucharest hospital that belonged to three singleton STs (ST252, ST254 and ST395); group II comprises clinical strains from Central Romania (Cluj hospital) and one collecting sewage tank from a hospital unit in Bucharest that belonged to the epidemic clone ST233; group III included strains isolated from Iași hospital sewage and its collecting WWTP G belonging to ST640; group IV was represented by one Bucharest hospital unit collecting sewage tank isolate belonging to ST621; group V included wastewater strains from central Romania belonging to ST620; group VI contained the majority of the strains (clinical and wastewater isolates from South and East Romania) belonging to the widespread ST357 and one unknown ST (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic tree of clinical and wastewater Pa strains

The spread from the hospital unit into the natural aquatic recipient was observed in some cases, i.e.: for an epidemic clone isolated from Galați hospital unit and the receiving WWTP D (ST357 carrying the blaVEB-9 ESBL encoding gene);two ST640 strains isolated Iași hospital and sludge from the Iași urban WWTP (32 SNPs, thus below the proposed threshold of 37 SNPs). The other Pa strains are more diverse, even within the same clone, the strains being more distantly related (> 100 SNPs); this fact was also suggested by the difference between the core genome (4716 genes) and the pan genome (12,395 genes) calculated for all the Pa strains included in this study.

Discussion

Hospitals are a concentrated source of MDR bacteria, which besides having clinical consequences (treatment options are limited and expensive), can be released in wastewater and finally into the environment [45]. Previous studies have revealed the presence of β-lactams, tetracyclines, quinolones and sulfonamides resistance genes in both natural and polluted aquatic environments, indicating that these determinants are released from clinical into aquatic environments, and then further disseminated to opportunistic pathogens [46]. Therefore, rapid identification of high-risk clones is essential for isolating infected patients, preventing the spread of resistance and improving the antimicrobial treatment. This requires the knowledge of the genetic environment and the carrying platforms of ARGs, as well as the development of new methods for assessing the spreading potential of ARGs mediated by mobile genetic elements in both aquatic and hospital environments.

In Romania, in contrast to clinical studies [27, 28, 47–61], there is little information available on the epidemiology of AMR reservoirs in the environment, especially in polluted water and rivers. We have previously shown that MDR, CP and ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolated from clinics, hospital wastewater and urban WWTPs from different regions of the country exhibit multiple antibiotic and antiseptic resistance, as well as virulence genes, with the ST101 clone being the most frequently encountered in all sampling sites [62]. Also, we have demonstrated the spread of K. pneumoniae ST101 from hospital to wastewater influent and its persistence in the wastewater effluent after the chlorine treatment, suggesting its dissemination in the community and in different aquatic compartments [63]. Our previous research showed that enterococci and Enterobacterales strains in four Romanian natural aquatic fishery lowland salted lakes from Natura 2000 Network carried a high diversity of resistance markers correlated with class 1 integrons [64]. Other authors described tetracycline and sulfonamides ARGs in the WWTP and the receiver river from northwestern Romania and demonstrated that some ARGs, such as blaVIM and blaSHV could persist in the chlorinated hospital wastewater, being detected both in the influent and chlorinated effluent [65, 66].

The purpose of this study was to characterize the AMR profiles and clonality of two of the most dangerous ESKAPE pathogens, Ab and Pa, isolated for two consecutive years from hospital settings, hospital collecting sewage tanks and the receiving WWTPs from three different geographical regions of Romania. The clinical and environmental Ab isolates recovered from different geographical regions of Romania revealed high AMR and MDR levels. In another study, from a significant number of groundwater, surface water, and soil samples from Hungary, there were isolated different Acinetobacter species (i.e., A. baumannii, A. johnsonii, A. gyllenbergii and A. beijerinckii, with 8.10% of A. beijerinckii) exhibiting an MDR phenotype [67].

In our study, imipenem-resistant Ab and Pa strains were also resistant to other classes of clinically important antibiotics, including quinolones (ciprofloxacin) and aminoglycosides (gentamicin). MDR was defined according to Magiorakos et al. [45], as non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial classes. The phenotypic resistance profiles and MDR rates have largely varied by sampling point and by geographic location. The highest MDR rates in aquatic isolates were recorded in Galați WWTP (D) that could be explained by the location of this county on the lower course of Danube River. The Danube River is considered the most important non-oceanic body of water in Europe and the “future central axis for the European Union”, with its Danube Delta included in the Biosphere Reserve and Ramsar Sites lists. The Danube River crosses ten countries, so this basin represents an optimal pool for resistant pathogens and anthropogenic pollutants dissemination and accumulation throughout large and distant areas, being assigned as a reservoir of AMR. The following two locations with high MDR rates in the aquatic isolates were Bucharest (H) (the capital and largest city) and Târgoviște (E), both located in the Southern part of the country.

The most frequently CPs encountered in clinical and environmental Ab strains were OXA-23 and OXA-24, while the ESBLs were represented by SHV, TEM and GES. Hrenovic et al., in 2016 investigated the AMR of Ab recovered from the IN and the final EF of a municipal WWTP in Zagreb, Croatia and revealed that 66.66% of the Ab isolates were positive for the acquired CP blaOXA-23 and blaOXA-24 [68]. Previous data has also indicated the presence of different A. baumannii complex species with MDR phenotypes isolated from environmental samples in Hungary [67]. For Pa clinical strains, the following CPs and ESBLs have been detected: IMP, VIM, NDM, VEB, GES and TEM.

WGS bioinformatic analysis of Ab strains highlighted that the international clone ST2 is broadly spread in our country (Additional file 3: Fig. S1), with 56% of the analyzed Ab strains belonging to this clone. Two ST2 strains were included in ST2 branch since the ST492 is a single locus variant of ST2 [61]. The other STs (in the set highlighted with grey in Additional file 3: Fig. S1) have phylogenetic relationships in accordance with the reference sequences, meaning that the whole cluster highlighted with grey is not homogenous, due to random selection of the reference sequence for the phylogenetic analysis. Therefore, the following STs belong to the cluster (in the same order as in the phylogenetic tree): ST499, ST78, unknown, unknown, ST155, ST622, ST46, ST16, ST40, ST403, unknown, ST429, unknown, ST71, ST113, ST25, unknown, ST10, ST10, ST10, ST108, ST514, unknown (Additional file 3: Fig. S1). Worldwide CP producers are mostly associated with international clone II and OXA-23 [61, 69, 70]. Other clinical and wastewater isolates belonged to ST636, ST1, ST79, ST492 and ST2 and were correlated with OXA-72. In Zagreb (Croatia) carbapenem-resistant Ab positive for blaOXA-23 recovered from different sampling points of a WWTP and the sewage of a nursing home belonged to the international clonal lineage IC2, the OXA-72 producers belonged to IC1, while the susceptible ones were unclustered [71, 72]. The OXA-23, OXA58, and OXA-72 CPs linked to ST2 in hospital environments have also been reported in other countries such as Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina [73–76].

The WGS analysis of Pa strains has shown that ST357 was correlated with IMP-13 in one clinical strain; in the sewage effluent, ST357 was correlated with VEB-9 and with both IMP-13 and VEB-9; the epidemic clone ST233 was correlated with VIM-2 in clinical and wastewater Pa strains; ST640 with TEM-40 in hospital sewage and WWTP; ST621 with IMP-13 in hospital sewage; ST620 with GES-1 in WWTP, while an unknown ST was correlated with VIM-2 in a sewage strain. The singletons ST252, 254, 244, 395 were not CP or ESBL producers.

A class 1 integron (qacE∆1 integron-associated gene) was present in most of the identified Ab clones. This association could be the result of co-selection processes due to the spread of successful clones (such as ST2, ST636 and ST1 Ab) that were selected by antibiotic treatment in the hospital settings and were able to accumulate various CPs and ESBLs (i.e., OXA-23, OXA-72, TEM-12, ADC-30, ADC-74, ADC-73, ADC-81). Class 1 integrons were revealed in 80% of Pa strains and 50% of Pa belonging to the epidemic clones ST233, ST357 and the ST244.

Since the prevalent clones have a great potential for transmission among patients, the observation that those prevalent clones are correlated with the presence of class 1 integrons suggests that those isolates could be a significant reservoir of ARGs and can persist in the environment.

One of the limitations of this study arises from the fact that we have selected, using antibiotic supplemented culture media, only the resistant Ab and Pa strains, while the total population structure of these pathogens (including the antibiotic-sensitive strains) could not be assessed by this approach. However, we have isolated non-MDR strains in few cases (e.g., Ab strains from Cluj WWTP I and Pa strains from Târgoviște, Vâlcea, Iași hospitals and from Iași WWTP G and Timisoara WWTP F), but these isolated were not investigated at the genetic level (Additional file 1: Tables 1 and 2).

Conclusion

Our study emphasized the presence of carbapenem-resistant MDR Ab and Pa belonging to international high-risk clones in all investigated sampling points (hospital units, their collecting sewage tanks and the sampled WWTPs) and the clonal dissemination of clinical Ab ST2 strains in the wastewaters. The reported data highlight the importance of the screening for acquired AMR in the environment and could provide important knowledge for monitoring the ARB and ARGs transmission from hospital into water bodies.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Tables S1 and S2 AR profiles in clinical and wastewater Ab and Pa strains.

Additional file 2. Table S3 ARGs in clinical and wastewater Ab strains isolated in 2019.

Additional file 3. Fig. S1 Phylogenetic tree of 105 genomes based on pangenome analysis. It was observed that 5 ST2 resistant clinical strains (GCF_000186645.1, GCF_000302075.1, GCF_018928195.1, GCF_000189655.1 and GCF_005819175.1) of the 71 reference strains were closely related with sequences belonging to strains isolated from intra-hospital infections in H2, Târgoviste and Cluj and from wastewater strains isolated from the collecting sewage tanks of hospital H2 Târgoviste and WWTP D and G.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- AMR

Antimicrobial resistance

- WWTPs

Wastewater treatment plants

- ARB

Antibiotic resistant bacteria

- ARGs

Antibiotic resistance genes

- MDR

Multi-drug resistant

- CP

Carbapenemase

- ESBL

Extended spectrum β-lactamase

- Ab

Acinetobacter baumannii

- Pa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- WGS

Whole-genome sequencing

- MGEs

Mobile genetic elements

- HGT

Horizontal gene transfer

- JPIAMR

Joint programme initiative on antimicrobial resistance

- CDC

Centers for disease control and prevention

- CHDLs

Carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamases

- MBL

Metallo-β-lactamases

- VIM

Verona integron-encoded MBL

- IMPs

Imipenemases

- NDM

New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase

- AIM

Australian imipenemase

- CAM

Central alberta MBL

- DIM

Dutch imipenemase

- FIM

Florence imipenemase

- GIM

German imipenemase

- HMB

Hamburg MBL

- SPM

São Paulo MBL

- SIM

Seoul imipenemase

- VEB

Vietnamese extended-spectrum β-lactamase

- PER

Pseudomonas extended-resistant

- TEM

Temoneira patient’s name

- SHV

Sulfhydryl variable enzyme

- CTX-M

Cefotaxime first isolated in munich carbapenemase

- GES

Guyana Extended Spectrum β-lactamase

- WWTP C and H

Bucharest WWTP

- WWTP E

WWTP Târgoviște

- WWTPJ

WWTP Râmnicu-Vâlcea

- WWTP I

WWTP Cluj

- WWTP F

WWTP Timișoara

- WWTP G

WWTP Iași

- WWTP D

WWTP Galați

- EF

Effluent

- IN

Influent

- AS

Activated sludge

- RS

Returned sludge

- CLSI

Clinical and laboratory standards institute

- RIF

Rifampicin

- MLST

MultiLocus sequence typing

- MEM

Meropenem

- IMP

Imipenem

- CAZ

Ceftazidime

- ATM

Aztreonam

- FEP

Cefepime

- TZP

Piperacillin-tazobactam

- CIP

Ciprofloxacin

- GEN

Gentamicin

- AK

Amikacin

- MH

Minocycline

- SAM

Ampicillin sulbactam

- H

Hospital

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

Author contributions

IG-B, ICB and MCC designed the study and corrected the manuscript; LM, MP, LIP, ICB, GGP, AB, CS; SG, IL, OS performed the isolation and identification of the samples; IG-B, AM, CSD, DT, MP, MMM, MIP screened the phenotypic and molecular markers of the isolates; MS, SP performed the WGS experiments; ICB and LIP contributed to the assembling, annotation and characterization of the obtained data; IG-B and ICB analyzed the WGS and performed the molecular epidemiological studies; MCC, MNL, DO, SP, MS, MP read and corrected the manuscript; IG-B, ICB and MS have equally contributed to this paper as main authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The financial support of the Research Projects PN-III-P1.1-PD-2016-1798 (PD 148/2018), PN-III-P4-ID-PCCF-2016-0114, PN-III-P1.1-TE-2021-1515 (TE 112/2022) and PN-III-P1-1.1-PD-2021-0540 (PD 102/2022) awarded by UEFISCDI and C1.2.PFE-CDI.2021-587/ Contract no.41PFE/30.12.2021 is gratefully acknowledged. The funding had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed or generated during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files. Any additional information is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Irina Gheorghe-Barbu and Marius Surleac have equally contributed to this work.

Contributor Information

Irina Gheorghe-Barbu, Email: iryna_84@yahoo.com.

Ilda Czobor Barbu, Email: ilda.barbu@bio.unibuc.ro.

Laura Ioana Popa, Email: lpbio_laura@yahoo.com.

Grațiela Grădișteanu Pîrcălăbioru, Email: gratiela87@gmail.com.

Marcela Popa, Email: bmarcelica@yahoo.com.

Luminița Măruțescu, Email: lumi.marutescu@gmail.com.

Mihai Niță-Lazar, Email: mihai.nita@incdecoind.ro.

Alina Banciu, Email: alina.banciu@incdecoind.ro.

Cătălina Stoica, Email: catalina.stoica@incdecoind.ro.

Ștefania Gheorghe, Email: stefania.gheorghe@incdecoind.ro.

Irina Lucaciu, Email: bioteste.ecoind@gmail.com.

Oana Săndulescu, Email: oanasandulescu1@gmail.com.

Simona Paraschiv, Email: mona_manaila@yahoo.com.

Marius Surleac, Email: marius.surleac@gmail.com.

Daniela Talapan, Email: dtalapan@gmail.com.

Andrei Alexandru Muntean, Email: muntean.alex@gmail.com.

Mădălina Preda, Email: madalina.prd@gmail.com.

Mădălina-Maria Muntean, Email: mmada.muntean@gmail.com.

Cristiana Cerasella Dragomirescu, Email: ceraseladragomirescu@yahoo.com.

Mircea Ioan Popa, Email: mircea.ioan.popa@gmail.com.

Dan Oțelea, Email: dotelea@mateibals.ro.

Mariana Carmen Chifiriuc, Email: carmen_balotescu@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/antimicrobial-consumption/database/country-overview. Accessed at December 28, 2021.

- 2.Baquero F, Martínez JL, Rafael CR. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in water environments. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergeron S, Boopathy R, Nathaniel R, Corbin A, LaFleur G. Presence of antibiotic resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes in raw source water and treated drinking water. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 2015;102:370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2015.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meseko C, Makanju O, Ehizibolo D, Muraina I. Veterinary pharmaceuticals and antimicrobial resistance in developing countries, veterinary medicine and pharmaceuticals. IntechOpen. 2019 doi: 10.5772/intechopen.84888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kümmerer K. Antibiotics in the aquatic environment–a review–part I. Chemosphere. 2009;75(4):417–434. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.11.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang XX, Zhang T, Fang HH. Antibiotic resistance genes in water environment. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;82(3):397–414. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1829-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uluseker C, Kaster KM, Thorsen K, Basiry D, Shobana S, Jain M, et al. A review on occurrence and spread of antibiotic resistance in wastewaters and in wastewater treatment plants: mechanisms and perspectives. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:717–809. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.717809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizzo L, Manaia C, Merlin C, Schwartz T, Dagot C, Ploy MC, Michael I, Fatta-Kassinos D. Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes spread into the environment: a review. Sci Total Environ. 2013;1(447):345–360. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karkman A, Johnson TA, Lyra C, Stedtfeld RD, Tamminen M, Tiedje JM, Virta M. High-throughput quantification of antibiotic resistance genes from an urban wastewater treatment plant. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiw014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsson DGJ, Flach CF. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20:257–269. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00649-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S, Aga DS. Potential ecological and human health impacts of antibiotics and antibiotic-resistant bacteria from wastewater treatment plants. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2007;10(8):559–573. doi: 10.1080/15287390600975137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alrhmoun M. Hospital wastewaters treatment: upgrading water systems plans and impact on purifying biomass. Environmental Engineering. Université de Limoges. 2014. English ffNNT :2014LIMO0042ff. ff.tel-01133490.

- 13.Amarasiri M, Sano D, Suzuki S. Understanding human health risks caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARG) in water environments: current knowledge and questions to be answered. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2020;50(19):2016–2059. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2019.1692611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnasamy S, Vijayan JV, Ramya Srinivasan GD, Indumathi MN. Antibiotic usage, residues and resistance genes from food animals to human and environment: an Indian scenario. J Environ Chem Eng. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2018.02.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karkman A, Do TT, Walsh F, Virta MPJ. Antibiotic-resistance genes in waste water. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26(3):220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.https://www.jpiamr.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/JPIAMR_SRIA_final.pdf. Accesses at 28.12.2021.

- 17.Chokshi A, Sifri Z, Cennimo D, Horng H. Global contributors to antibiotic resistance. J Glob Infect Dis. 2019;11(1):36–42. doi: 10.4103/jgid.jgid_110_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Rosa FG, Corcione S, Pagani N, Di Perri G. From ESKAPE to ESCAPE, from KPC to CCC. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(8):1289–90. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulani MS, Kamble EE, Kumkar SN, Tawre MS, Pardesi KR. Emerging strategies to combat ESKAPE pathogens in the era of antimicrobial resistance: a review. Front Microbiol. 2019;2019(10):539. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karlowsky JA, Lob SH, Kazmierczak KM, Hawser SP, Magnet S, Young K, Motyl MR, Sahm DF. In vitro activity of imipenem/relebactam against Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens isolated in 17 European countries: 2015 SMART surveillance programme. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(7):1872–1879. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CDC. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, Atlanta, GA: US. Department of health and human services, CDC. 2019. 10.15620/cdc:82532.

- 22.Santajit S, Indrawattana N. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Biomed Res Int. 2016;16:2475067. doi: 10.1155/2016/2475067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Da Silva GJ, Domingues S. Insights on the horizontal gene transfer of Carbapenemase determinants in the opportunistic pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. Microorganisms. 2016;4(3):29. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms4030029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoon EJ, Jeong SH. Mobile Carbapenemase genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:614058. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.614058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clinical and laboratory standards institute. 2018. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 28th informational supplement. 2018; M02, M07 and M11.

- 26.Clinical and laboratory standards institute. 2019. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 29th informational supplement. 2019; M02, M07 and M11.

- 27.Gheorghe I, Czobor I, Chifiriuc MC, Borcan E, Ghiță C, Banu O, et al. Molecular screening of carbapenemase-producing Gram negative strains in Roumanian intensive care units during one year survey. J Med Microbiol. 2014;63:1303–1310. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.074039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gheorghe I, Cristea VC, Marutescu L, Popa M, Murariu C, Trusca BS, Borcan E, Ghiță MC, Lazăr V, Chifiriuc MC. Resistance and virulence features in carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii community acquired and nosocomial isolates in Romania. Rev Chim. 2019;10:3502–3507. doi: 10.37358/RC.19.10.7584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng Y, Yang P, Wang X, Zong Z. Characterization of Acinetobacter johnsonii isolate XBB1 carrying nine plasmids and encoding NDM-1, OXA-58 and PER-1 by genome sequencing. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:71–75. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrews S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data [Online]. 2010. Available online at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/

- 31.Seemann T. Shovill: faster SPAdes assembly of Illumina reads (v1.1.0). 2018; https://github.com/tseemann/shovill. Accessed 12.06.2020.

- 32.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(14):2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.https://github.com/tseemann/abricate. Accessed June 30, 2020.

- 34.Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, Vestergaard M, Rasmussen S, Lund O, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(11):2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cosentino S, Larsen MV, Aarestrup FM, Lund O. PathogenFinder-distinguishing friend from foe using bacterial whole genome sequence data. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carattoli A, Zankari E, García-Fernández A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, Villa L, et al. PlasmidFinder and pMLST: in silico detection and typing of plasmids., Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58(7):3895–903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feldgarden M, Brover V, Haft DH, Prasad AB, Slotta DJ, Tolstoy I, et al. Validating the AMRFinder tool and resistance gene database by using antimicrobial resistance genotype-phenotype correlations in a collection of isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63(11):e00483–19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00483-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.http://www.genomicepidemiology.org/. Accessed July 20, 2020

- 39.https://card.mcmaster.ca/. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- 40.Seemann T, mlst (v2.19.0). Github https://github.com/tseemann/mlst. Accessed July 12,2020.

- 41.Seemann T. Snippy: fast bacterial variant calling from NGS reads (v4.6.0). https://github.com/tseemann/snippy. 2015, Accessed July 12, 2020.

- 42.Page AJ, Cummins CA, Hunt M, Wong VK, Reuter S, Holden MT, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(22):3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new development., Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47(W1):W256-W259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marinescu F, Marutescu L, Savin I, Lazar V. Antibiotic resistance markers among gram-negative isolates from wastewater and receiving rivers in South Romania. Romanian Biotechnol Lett. 2015;20(1):10055–10069. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mereuţă AI, Docquier JD, Rossolini GM, Buiuc D. Detection of metallo-beta-lactamases in Gram-negative bacilli isolated in hospitals from Romania-research fellowship report. Bacteriol Virusol Parazitol Epidemiol. 2007;52(1–2):45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Radu-Popescu MA, Dumitriu S, Enache-Soare S, Bancescu G, Udristoiu A, Cojocaru M, Vagu C. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of antibiotic resistance patterns in Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated in a Romanian hospital. Farmacia. 2010;3:362–367. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bonnin RA, Poirel L, Licker M, Nordmann P. Genetic diversity of carbapenem-hydrolysing β-lactamases in Acinetobacter baumannii from Romanian hospitals. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(10):1524–1528. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hurezeanu DD, Dragonu L, Canciovici C, Ristea D, Ene D, Cotulbea M, et al. Infections with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients admitted to the “Victor Babeş” clinical hospital of infectious diseases and pneumology. Craiova BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:P40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-S1-P40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gheorghe I, Novais A, Grosso F, Rodrigues C, Chifiriuc MC, Lazar V, Peixe L. Snapshot of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii in Bucharest hospitals reveals unusual clones and novel genetic surroundings for blaOXA-23. J AntimicrobChemother. 2015;70(4):1016–1020. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dortet L, Flonta M, Boudehen YM, Creton E, Bernabeu S, Vogel A, Naas T. Dissemination of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Romania. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(11):7100–7103. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01512-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Timofte D, Panzaru CV, Maciuca IE. Active surveillance scheme in three Romanian hospitals reveals a high prevalence and variety of carbapenamaseproducing Gram-negative bacteria: a pilot study. Eurosurveillance. 2016 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.25.30262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lăzureanu V, Poroșnicu M, Gândac C, Moisil T, Bădițoiu L, Laza R, et al. Infection with Acinetobacter baumannii in an intensive care unit in the Western part of Romania. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1399-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gavriliu LC, Popescu GA, Popescu C. Antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a Romanian hospital at the dawn of multidrug resistance. Braz J Infect dis. 2016;20(5):509–510. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Călina D, Docea AO, Rosu L, Zlatian O, Rosu AF, Anghelina F, et al. Antimicrobial resistance development following surgical site infections. Mol Med Rep. 2017;15:681–688. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.6034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vata A, Pruna R, Rosu F, Miftode E, Nastase EV, Vata LG, Dorneanu O. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in the “Sfânta Parascheva” infectious diseases hospital of Iași city. Ro J Infect Dis. 2018;21(3):115–120. doi: 10.37897/RJID.2018.3.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muntean D, Horhat FG, Bădițoiu L, Dumitrașcu V, Bagiu IC, Horhat DI, et al. Multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli: a retrospective study of trends in a tertiary healthcare unit. Medicina. 2018;54:92. doi: 10.3390/medicina54060092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arbune M, Gurau G, Niculet E, Iancu AV, Lupasteanu G, Fotea S, et al. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance of ESKAPE pathogens over five years in an infectious diseases hospital from South-East of Romania. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:2369–2378. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S312231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buzilă ER, Năstase EV, Luncă C, Bădescu A, Miftode E, Iancu LS. Antibiotic resistance of non-fermenting gram-negative bacilli isolated at a large infectious diseases hospital in North-Eastern Romania, during an 11-year period. Germs. 2021;11(3):354–362. doi: 10.18683/germs.2021.1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gheorghe I, Barbu IC, Surleac M, Sârbu I, Popa LI, Paraschiv S, et al. Subtypes, resistance and virulence platforms in extended-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Romanian isolates. Sci Rep. 2021;2021(11):13288. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92590-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Surleac M, Czobor Barbu I, Paraschiv S, Popa LI, Gheorghe I, Marutescu L, et al. Whole genome sequencing snapshot of multi-drug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains from hospitals and receiving wastewater treatment plants in Southern Romania. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1):e0228079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Popa LI, Gheorghe I, Barbu IC, Surleac M, Paraschiv S, Măruţescu L, et al. Multidrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST101 clone survival chain from inpatients to hospital effluent after chlorine treatment. Front Microbiol. 2021;11(11):610296. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.610296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lazăr V, Gheorghe I, Curutiu C, Savin I, Marinescu F, Cristea VC, et al. Antibiotic resistance profiles in cultivable microbiota isolated from some romanian natural fishery lakes included in Natura 2000 network. BMC VetRes. 2021;17(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s12917-021-02770-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Țugui CG, et al. Studia Universitatis Babeş-Bolyai Biologia, 2015; LX, Sp. Iss., 33–38.

- 66.Lupan I, Carpa R, Oltean A, Kelemen BS, Popescu O. Release of antibiotic resistant bacteria by a waste treatment plant from Romania. Microbes Environ. 2017;32(3):219–225. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME17016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Radó J, Kaszab E, Benedek T, Kriszt B, Szoboszlay S. First isolation of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter beijerinckii from an environmental sample. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2019;66(1):113–130. doi: 10.1556/030.66.2019.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hrenovic J, Goic-Barisic I, Kazazic S, Kovacic A, Ganjto M, Tonkic M. Carbapenem-resistant isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii in a municipal wastewater treatment plant, Croatia, 2014. Euro Surveill. 2016 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.15.30195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mugnier PD, Poirel L, Naas T, Nordmann P. Worldwide dissemination of the blaOXA-23 carbapenemase gene of Acinetobacter baumannii. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:35–40. doi: 10.3201/eid1601.090852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dortet L, Bonnin RA, Girlich D, Imanci D, Bernabeu S, Fortineau N, Naas T. Whole-genome sequence of a European clone II and OXA-72-producing Acinetobacter baumannii strain from Serbia. Genome Announc. 2015;3(6):e01390–15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01390-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Higgins PG, Hrenovic J, Seifert H, Dekic S. Characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii from water and sludge line of secondary wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 2018;2018(140):261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bedenic B, Beader N, Siroglavic M, Slade M, Car H, Dekic S, et al. Acinetobacter baumannii from a sewage of a nursing home in Croatia. Microb Drug Resist. 2015;21(3):270–278. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2014.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mammina C, Palma DM, Bonura C, Aleo A, Fasciana T, Sodano C, et al. Epidemiology and clonality of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii from an intensive care unit in Palermo. Italy BMC Research Notes. 2012;5:365. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Izdebski R, Janusz Fiett J, Waleria Hryniewicz W, Marek GM. Molecular Analysis of Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates from Invasive Infections in 2009 in Poland. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(11):3813–3815. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02271-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Petrova AP, Stanimirova ID, Ivanov IN, Petrov MM, Miteva-Katrandzhieva TM, Grivnev VI. Carbapenemase production of clinical isolates Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa from a Bulgarian University Hospital. Folia Med. 2017;59(4):413–422. doi: 10.1515/folmed-2017-0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goic-Barisic I, Kovacic A, Medic D, Jakovac S, Petrovic T, Tonkic M, et al. Endemicity of OXA-23 and OXA-72 in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii from three neighbouring countries in Southeast Europe. J Appl Genet. 2021;62(2):353–359. doi: 10.1007/s13353-021-00612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Tables S1 and S2 AR profiles in clinical and wastewater Ab and Pa strains.

Additional file 2. Table S3 ARGs in clinical and wastewater Ab strains isolated in 2019.

Additional file 3. Fig. S1 Phylogenetic tree of 105 genomes based on pangenome analysis. It was observed that 5 ST2 resistant clinical strains (GCF_000186645.1, GCF_000302075.1, GCF_018928195.1, GCF_000189655.1 and GCF_005819175.1) of the 71 reference strains were closely related with sequences belonging to strains isolated from intra-hospital infections in H2, Târgoviste and Cluj and from wastewater strains isolated from the collecting sewage tanks of hospital H2 Târgoviste and WWTP D and G.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed or generated during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files. Any additional information is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.