Abstract

Objective

To investigate the potential effect of Lysimachia capillipes capilliposide (LCC) on the chemo sensitivity and the stemness of human ovarian cancer cells.

Methods

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) was used to measure the IC50 values. The apoptosis of cells was measured through flow cytometry. Evaluation of the stemness and differentiation markers was performed by the immunoblotting and the immunostaining assays. RNA-seq was performed through the Illumina HiSeq PE150 platform and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were screened out through the bioinformation analysis. Overexpression or knockdown of Fos gene was achieved by shRNA transfection.

Results

Pre-exposure of A2780T cells with 10 μg/mL LCC sensitized them to paclitaxel, of which the IC50 value reduced from 8.644 μmol/L (95%CI: 7.315–10.082 μmol/L) to 2.5 μmol/L (95%CI: 2.233–2.7882 μmol/L). Exposure with LCC enhanced the paclitaxel-induced apoptosis and inhibited the colony formation of A2780T cells. LCC exposure reduced the expression of cancer stemness markers, ALDH1, Myd88 and CD44, while promoting that of terminal differentiation markers, NFATc1, Cathepsin K and MMP9. RNA-seq analysis revealed that the expressions of FOS and JUN were upregulated in LCC-treated A2780T cells. A2780T cells overexpressing Fos gene displayed increased paclitaxel-sensitivity and reduced cell stemness, and shared common phenotypes with LCC-treated A2780T cells.

Conclusion

These findings suggested that LCC promoted terminal differentiations of ovarian cancer cells and sensitized them to paclitaxel through activating the Fos/Jun pathway. LCC might become a novel therapy that targets at cancer stem cells and enhances the chemotherapeutic effect of ovarian cancer treatments.

Keywords: cancer stem cell, capilliposide, chemo-resistance, Fos gene, Lysimachia capillipes hemsl, ovarian cancer

1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer represents one of the most lethal gynecological malignant diseases worldwide and accounts for nearly 300 thousand new cases and 200 thousand deaths annually (Bray et al., 2018). Despite advances in surgeries and chemotherapies, the survival rate of patients with a high-grade epithelial ovarian cancer remains extremely low. Standard chemotherapies including carboplatin and paclitaxel (Taxol) combination induce a complete remission (CR) ranging from 50% to 81%. However, more than 80% of patients with an advanced disease of ovarian cancer would experience a disease relapse within two years of their initial treatment (Pokhriyal, Hariprasad, Kumar, & Hariprasad, 2019). Treatment failures are often attributed to primary or acquired resistance to chemotherapeutic agents. Therefore, chemo-resistance of ovarian cancer has emerged as a major challenge for clinicians and researchers.

Increasing evidences indicate that the chemo-resistance of cancers is associated with the behavior of cancer stem cells (CSCs) (Keyvani et al., 2019). CSCs have been defined as a small subpopulation of cells within the tumor bulk mass, which possess the capacity to self-renew and give rise to all heterogeneous cancer cell lineages. Therefore, CSCs were considered as the origin of tumor. CSCs that express distinctive markers, including ALDH1 (Ruscito et al., 2018), CD24, CD44 (Meng et al., 2012), CD117 (Yang, Yan, Liu, Jiang, & Hou, 2017), MyD88 (d'Adhemar et al., 2014), etc., have been identified in ovarian cancer. Moreover, these CSCs often present drug resistance attributed to a series of typical cytological characterizations, including a low proliferation rate, high frequency in G0 phase of cell cycle and resistance to apoptosis (Cole et al., 2020). Targeting CSCs have been supposed to be alternative therapies for the prevention of chemo-resistance in ovarian cancer (Keyvani et al., 2019).

Lysimachia capillipes hemsl (LC), a Chinese herb and medicinal plant, is widely used as a remedy for the treatment of colds and arthritis. Recently, it has been revealed by pharmacological investigations that capilliposide extracted from the Lysimachia genus, exhibits an inhibitory effect on cell growths of various cancers (Fei et al., 2014, Li et al., 2014, Shen et al., 2017). However, the mechanisms by capilliposide from L. capillipes (LCC) exhibiting its effects remain unclear. It was revealed in our previous works that a short-term exposure with LCC could lead to remarkable epigenetic changes (including histone methylation and acetylation) in taxol-resistant cell line A2780T of ovarian cancer. Epigenetic reprogramming represents the major pathway for terminal differentiated cells to acquire stem cell properties (van Vlerken et al., 2013). Therefore, we supposed that LCC might have an effect on stemness remodeling and chemo-resistance regulation in ovarian cancer.

In this study, we investigated the effects of LCC on chemo-resistance and cancer cell stemness using two human ovarian cancer cell lines——A2780 and A2780T. It was found that LCC inhibited cellular growths and reversed the resistance to paclitaxel in A2780T cells. Moreover, it was revealed by results of immunostaining and colony formation assays that stemness of CSCs was significantly reduced after an LCC exposure. Mechanistic investigations revealed that the Fos/Jun pathway played a key role in LCC-induced terminal differentiation and anti-cancer effects. These findings indicated that LCC might become a novel anti-cancer therapy that enhances the chemotherapeutic effects of ovarian cancer treatment.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Cells and reagents

The A2780 and A2780T cell lines were both obtained from EK-bioscience Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and maintained in RPMI‑1640 (Thermo) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The paclitaxel (Yangtze River Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) was dissolved and stock according to the manufacturer's instruction. Capilliposide from Lysimachia capillipes was obtained from the Department of Chinese Medicine Sciences & Engineering of Zhejiang University (Hangzhou, China). All of the drugs were diluted with fresh media before each experiment.

2.2. Vector construction and cell transfection

Full length cDNA of human Fos gene (Genbank NM_005252.4) were synthesized at Tsingke Biological Technology (Hangzhou, China) and inserted into the EcoRI/BamHI site of pLV-EF1a-EGFP vector (Inovogen). ShRNAs were synthesized and inserted into the pLV-shRNA-EGFP vector (Inovogen). The sequence that targeted by shRNAs were listed in Supplementary Table S1. Constructed vectors were verified by restriction enzyme digestion and sequencing. Validated vectors were transfected into A2780T cells as needed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) assay

The CCK8 assay was performed according to the manufacture’s instruction (Solarbio). IC50 value was determined using SPSS21.0.

2.4. Apoptosis

Cell apoptosis was evaluated using Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) double staining analysis as described previously. The samples were analyzed on a flow cytometer using the channel FITC and PE. Both early and late apoptotic cells were recorded as apoptotic cells, and the results were expressed as the percentage of apoptotic cells in total cells.

2.5. Colony formation assay

A2780 and A2780T cells were pre-treated with 10 μg/mL LCC or PBS for 72 h. Then, LCC-treated or non-treated cells were both seeded at low density (1000 cells/well) into a standard 6-well plate and grown for about 2 week in normal serum medium. Colonies with more than 50 cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and visualized by crystal violet staining.

2.6. Cancer stemness marker determination

For surface marker immunostaining, cell suspensions were incubated with fluorescently labeled CD24, CD44, CD117 antibodies (Biolegend) for 10 min. For intracellular marker staining, cells were fixed/permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD bioscience) and then incubated with fluorescently labeled ALDH1 and MyD88 antibodies (Santa Cruz). The samples were analyzed on a flow cytometer.

2.7. Western blotting analysis

The western blotting analysis was performed using a standard procedure. A total of 30 μg of protein crude extracts was resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore). The membrane was blocked and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with antibodies against Ki67 (Santa Cruz), NFATc1 (Santa Cruz), MMP9 (CST), Cathepsin K (Sigma), phospho-c-Fos (Ser32) (CST), c-Fos (CST), phospho-c-Jun (Ser73) (CST), c-Jun (CST), or β-actin (Thermo). Next, the membranes were washed twice in TBST and incubated with the secondary HRP-conjugated antibody (Thermo) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the proteins on the membranes were detected with the electro chemi luminescence (ECL) detection kit (Millipore) and visualized using the ChemiDocTM Imaging System (Bio-rad).

2.8. RNA extraction, sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

Biological duplicates of non-treated A2780, A2780T and LCC-treated A2780T cells were lysed in Trizol RNA isolation reagent (Invitrogen), then total RNA was extracted following the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA-Seq was performed using the Illumina HiSeq PE150 platform (Illumina) at Mega Genomics (Beijing, China). Gene annotations were obtained from nr, Swiss-Prot, KEGG databases (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) by BLAST. Genes with |log2 (fold change) | ≥1 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.01 were considered significant for DEGs. The calculated P-value went through Bonferroni Correction, taking corrected P-value < 0.05 as a threshold. Differentially expressed transcriptional factors (TFs) were further identified using AnimalTFDB2.0 database (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/AnimalTFDB2/).

2.9. Quantitative real time PCR (QRT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA of cells was extracted using a Trizol kit (Invitrogen). The reverse transcription reactions were performed using 2 μg of total RNA that was reverse transcribed into cDNA using oligo (dT) and random mixed primers (Tiangen, China). RT-PCR was carried out using Taqman® one-step PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Sequences of primers for all target gene were listed in Supplementary Table S2 (GAPDH was used as internal control).

2.10. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 statistical software and the data are presented as the mean ± SD. At least three biological replicates were included in each group. Statistical significance was calculated using Dunnett’s test or Student’s t-test for unpaired data, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of LCC on chemo-sensitivity of A2780 and A2780T cells

We first determined the effect of a first-line chemotherapeutic agent——paclitaxel, on growths of human ovarian cancer cell line A2780 and A2780 taxol-resistant cell line A2780T, respectively. With IC50 values determined by the CCK8 assay, we found that A2780T cells response to paclitaxel with IC50 values much higher than A2780 cells (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table S3). This validated the paclitaxel resistance in A2780T cells. To investigate whether LCC can reverse the paclitaxel-resistance of A2780T, we first needed to select an appropriate exposure concentration of LCC. We found that the IC50 value of LCC alone on A2780T cells was 11.393 μg/mL, with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) ranging from 8.48 − 16.156 μg/mL (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table S3). The IC50 value of LCC on A2780 cells was relative lower. Therefore, we used 10 μg/mL LCC prior to paclitaxel to treat A2780T cells, and found that the IC50 value of paclitaxel on A2780T cells was largely restored after LCC pre-treatment for 72 h (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table S3).

Fig. 1.

Effects of LCC on chemo-resistance, apoptosis and colony formation of human ovarian cancer cells A2780T. (A) Cytotoxic effects of paclitaxel on A2780 and A2780T cells, and the pre-exposure of LCC to sensitize A2780T cells to chemo drugs treatment. (B) Cytotoxic effects of LCC on A2780 and A2780T cells. OD450 was normalized to that of A2780 cells in solvent control group. (C) Ratio of apoptotic cells, including early and late phase apoptotic cells, was measured by annexin V/PI dual labeling and flow cytometry analysis. **P < 0.01 vs. A2780 group; ###P < 0.001 vs. A2780T group. (E) Representative images of wells at 2 weeks after seeded with A2780, non-treated A2780T and LCC-treated A2780T cells at low density (1000 cells/well). Colonies were visualized by crystal violet staining. (F) Statistical results of the number of colonies. ***P < 0.001 vs. non-treated A2780T group.

To determine whether LCC affected the drug-induced apoptosis in A2780T cells, Annexin V/ propidium iodide (PI) staining was performed to determine the proportion of apoptotic cells induced by paclitaxel. Smaller proportion of apoptotic cells were found in A2780T cells than A2780 cells at 72 h after treatment of paclitaxel. Pre-exposure with LCC increased the number of apoptotic A2780T cells induced by paclitaxel (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. S1). These results indicated that LCC facilitated chemo-induced apoptosis of A2780T, and sensitized ovarian cancer cells to chemotherapies.

3.2. Effects of LCC on colony formation of A2780T cells

Colony formation abilities of A2780 and A2780T cells were determined by the standard plate colony assay. In the absence of paclitaxel and LCC, A2780 and A2780T cells showed comparable colony formation ability. The addition of LCC did not change the colony number of A2780T cells. In the presence of 400 ng/mL or 800 ng/mL paclitaxel, colony formation of A2780 cells was completely impeded, while colony growth of A2780T cells was minimally affected. However, pre-exposure with LCC dramatically reduced the colony number of A2780T cells (Fig. 1D−E). In conclusion, LCC can inhibit the colony formation of A2780T cells.

3.3. Effects of LCC on stemness of A2780T cells

Effects of LCC on ovarian cancer stemness markers were determined by flow cytometry. In general, our results revealed that A2780T cells expressed high level of CD44, Myd88, ALDH1, and were negative for CD24 and CD117 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Pre-exposure with LCC significantly downregulated the expression of CD44, Myd88 and ALDH1 (Supplementary Fig. S2). These results suggested that A2780T cells exhibited stem-like cell properties, which were somewhat neutralized by LCC.

3.4. LCC induced transcriptomic changes that were associated with drug resistance and terminal differentiation in A2780T cells

To further explore the molecular mechanisms by which LCC exhibited its effects, we performed RNA-seq to analyze global transcriptomic changes of A2780T with or without LCC treatment. Among 7862 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between A2780 and A2780T cells, 3935 genes were up-regulated and 3927 genes were down-regulated in A2780T cells (Supplementary Table S4). KEGG analysis revealed that these DEGs were involved in critical pathways (Supplementary Fig. S3).

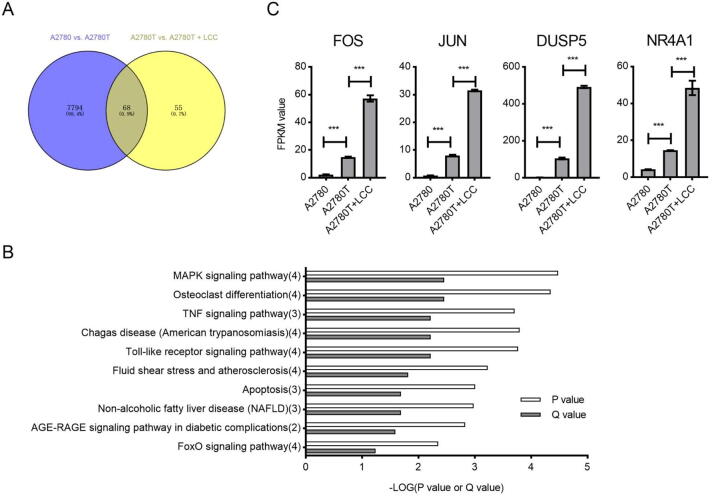

To evaluate transcriptomic changes between non-treated A2780T and LCC-treated A2780T cells, totally 123 DEGs, including 33 up-regulated and 90 down-regulated genes were filtered out and further analyzed. TFs prediction revealed that 16 TF-coding genes were differentially expressed in LCC-treated A2780T cells. When comparing the A2780 vs. A2780T DEGs and the non-treated A2780T vs. LCC-treated A2780T DEGs, we found that more than half of DEGs are overlapped in these two pairs (Fig. 2A). KEGG analysis revealed that the enriched pathways in these two pairs are also highly overlapped (Supplementary Fig. S4). Among these overlapped pathways, MAPK signaling and osteoclast differentiation were most enriched (Fig. 2B). Changes of the mRNA expression level of DEGs involved in this pathway, including FOS, JUN, DUSP5 and NR4A1, were shown in Fig. 2C. Of note, FOS, JUN and NR4A1 all fall into the category of differentially expressed TFs.

Fig. 2.

Results of RNA-seq analysis identified key signaling pathways and DEGs. (A) Venn diagram showing the number of overlapped DEGs between indicated groups. (B) KEGG enrichment analysis showing ranking of the most differentiated signaling pathways. Numbers of DEGs in each pathway were indicated in the brackets after the names of pathways. (C) FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) of indicated genes measured by RNA sequencing. ***P < 0.001.

3.5. LCC promotes chemo-sensitivity and terminal differentiation through activating Fos/Jun pathway in A2780T cells

Next, we aimed to determine which DEG(s) candidates (FOS, JUN or NR4A1) was responsible for the LCC-induced phenotypes. ShRNA-mediated knockdown of these genes was validated by QRT-PCR, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S5). Our results showed that knockdown of FOS and JUN (but not NR4A1) reduced the drug-induced apoptosis of A2780T cells and thus neutralized the effects of LCC treatment (Supplementary Fig. S6). Therefore, the Fos/Jun pathway might be critical for the LCC pharmacology.

In view of functional homogeneity of FOS and JUN genes, we tested whether knockdown of FOS alone could be antagonistic to the LCC effects on the biological phenotypes of A2780T cells. The CCK8 assays revealed that the growth inhibition effect of paclitaxel in A2780T cells was hardly affected after cells were transfected with Fos shRNA alone (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Table S5). However, LCC-induced sensitization of A2780T cells was largely abrogated by the Fos shRNA, with nearly half of the IC50 value restored. Moreover, overexpressing of Fos in A2780T cells mimicked the effect of LCC and significantly decreased the IC50 values compared with the LCC non-treated group (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Table S5). Therefore, our data proved that FOS gene plays a key role in LCC-mediated regulation of chemo-sensitivity.

Fig. 3.

Roles of LCC and c-Fos in chemo sensitivity and cell biological phenotypes of A2780T cells. (A) Cytotoxic effects of LCC and paclitaxel on transfected or non-transfected A2780T cells. (B) Statistical results of the ratio of apoptotic cells measured by annexin V/PI dual labeling and flow cytometry analysis. ***P < 0.001 vs. si-Ctrl group; ##P < 0.01 vs. LCC + si-Ctrl group; (C) Statistical results of the number of colonies in the colony formation assay. 400 ng/mL of paclitaxel was used. ***P < 0.001 vs. si-Ctrl group, ##P < 0.01 vs. LCC + si-Ctrl group. (D) Cells were stained with indicated antibodies and proportion of marker-positive cells were analysis by flow cytometry. ***P < 0.001 vs. A2780 + EV group. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. A2780T + EV group. ςP < 0.05, ςςP < 0.01 vs. A2780T + LCC + si-Ctrl group. (E) Western blot analysis showing the expression changes of indicated proteins. si-Ctrl, shRNA targeting control sequence; siFos, shRNA targeting c-Fos; Fos-OV, c-Fos-overexpressing vectors; EV, empty vectors.

The results of annexin V/PI dual staining revealed that knockdown of c-Fos reduced the number of apoptotic cells in LCC-treated A2780T (Fig. 3B). Overexpression of c-Fos in A2780T reversed this trend and mimicked the effect of LCC. Likewise, knockdown of c-Fos abrogated LCC-mediated suppression of colony formation capacity in A2780T cells (Fig. 3C). These results indicated that LCC promotes apoptosis and inhibits the colony formation of A2780T cells through activating the Fos/Jun pathway.

Given that LCC inhibited CSC formation shown previously, we examined the effect of LCC on differentiation status of A2780T with or without c-Fos overexpression/knockdown. Interestingly, expressions of stemness markers, including Myd88, ALDH1 and CD44 were all elevated by c-Fos shRNA compared with the LCC-treated plus si-Ctrl group (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Fig. S2). LCC-induced terminal differentiation, especially osteoclast differentiation (reflected by the expression of osteoclast-related markers, NFATc1, MMP9 and CTSK) was partially impeded by c-Fos shRNA (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Fig. S7). Moreover, overexpression of c-Fos did mimic the LCC and induced an osteoclast-like differentiation in A2780T cells (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Fig. S7). Taken together, these results indicated that LCC inhibited CSC formation and promoted terminal differentiation of A2780T through activating the Fos/Jun pathway.

4. Discussion

The resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs or chemo-resistance remains great challenges for clinical treatments of ovarian cancer. Here we showed that capilliposide, extracted from LC, exerted growth inhibitory effects on ovarian cancer cells A2780 and re-sensitized paclitaxel responses in taxol-resistant strains A2780T. Capilliposides are mixtures of triterpenoid saponins. Until now, growth inhibitory effects of single components or total extracts of capilliposide have been confirmed in vitro and in vivo on esophageal squamous cancer (Shen et al., 2017), prostate cancer (Li et al., 2014), nasopharyngeal cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (Fei et al., 2014) cells. Indeed, anti-cancer effects of triterpenoid saponins found in higher plants have been proved in their cytotoxic, cytostatic, proapoptotic and anti-invasive effects through many cellular models. Some of them have been clinically approved through their utilization in combination with first-line chemotherapeutic agents, so as to reduce the adverse effects of chemotherapies without attenuating their efficiency (Koczurkiewicz et al., 2019). Moreover, triterpenoid saponins have been proved to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents, including cisplatin (Liu et al., 2011), doxorubicin, and docetaxel (Kim et al., 2009), thus preventing chemo-resistance. Therefore, LCC holds a great potential for being developed into novel therapeutic drugs for ovarian cancer.

Yet, the molecular mechanisms of capilliposides have not been fully elucidated, but preliminary mechanistic investigations have been convergently pointed to several pathways, including JNK, PI3K (Shen et al., 2017), Caspase and MAPK (Li et al., 2014). Previous studies showed that capilliposide inhibited prostate cancer cells by inducing apoptosis through activating the MAPK pathway, decreasing P38 and JNK, but increasing p-P38 and p-JNK (Li et al., 2014). The c-Fos and c-Jun (major products of FOS and JUN) form dimers of TF—AP-1, which was a critical downstream effector of MAPK signaling. Physiological roles of c-Fos and c-Jun are diverse, which may be either oncogenic or tumor-suppressive (Eferl & Wagner, 2003). It has been reported that the expressions of CSC markers were enhanced by exogenous expressions of c-Fos in nontumorigenic headneck squamous cells, thus making these cells tumorigenic in nude mice (Muhammad, Bhattacharya, Steele, Phillips, & Ray, 2017). On the other hand, it is clear that the activation of JNK/AP-1 pathway is involved in the induction of apoptosis through specific stimuli (Shieh et al., 2010). Moreover, Fos/Jun AP-1 has been implicated in cell differentiation process, including osteoclast differentiation (Bakiri et al., 2007). In this study, we provided solid evidence that c-Fos is essential for mediating LCC-induced phenotypic changes, including drug resistance, colony formation, apoptosis and terminal differentiation. Therefore, c-Fos might act as an upstream regulator in response to LCC stimuli, and activation of Fos/Jun might initiate the whole set of downstream events that finally lead cells to terminal differentiation and increase their chemo-sensitivity.

Chemo-resistance is a multifactorial phenomenon. However, the main factors that contribute to cancer resistance remain unclear. Recently, cancer stem cell hypothesis provides a new explanation for the origin of drug resistance in ovarian cancer. The high heterogeneity of the pathological features of ovarian cancer suggests that the initiation and development of ovarian cancer may not be evolved from the cloning of a single mutated cell, but is closely related to a group of specific tumor cells with stem-like cell properties (Hatina et al., 2019). Due to their unique drug-resistant phenotypes, CSCs are more likely to survive from clonal selections under drug stress and initiate cancer recurrence. Extensive efforts have been made to identify and isolate CSCs from ovarian cancer, while researchers attempted to find solutions that specifically target at this population (Moghbeli, Moghbeli, Forghanifard, & Abbaszadegan, 2014). However, it has been found in previous studies that the formation of CSCs is completely random and CSCs themselves are heterogeneous (Macintyre et al., 2018). It seems difficult to eradicate CSCs through direct targeted therapies because even if a small number of CSCs that escape targeted treatments may lead to a recurrence. Here, our data showed that LCC reduced the number of CSCs by globally reduced the expression of stemness markers and the promotion of terminal differentiations. Therefore, targeting the switch that globally controlling the stemness maintenance may be a way to prevent CSC-initiated chemo-resistance.

5. Conclusion

Our study validated that LCC had anti-cancer properties and enhanced the sensitivity of paclitaxel on human ovarian cancer A2780T cells. In addition, we provided first-hand evidences of the effect of LCC on reducing cancer stemness and inducing terminal differentiations. The reversal of drug resistance and the terminal differentiations by LCC exposures were attributed to the activation of Fos/Jun signaling. Therefore, the combination of LCC with chemotherapeutic agents holds a great potential of being developed into adjuvant therapies for ovarian cancer.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Medical Science, Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. LGF18H160087).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chmed.2021.09.009.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Bakiri L., Takada Y., Radolf M., Eferl R., Yaniv M., Wagner E.F., Matsuo K. Role of heterodimerization of c-Fos and Fra1 proteins in osteoclast differentiation. Bone. 2007;40(4):867–875. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA-A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole, A. J., Iyengar, M., Panesso-Gomez, S., O'Hayer, P., Chan, D., Delgoffe, G. M., Aird, K. M., Yoon, E., Bai, S. M. & Buckanovich, R. J. (2020). NFATC4 promotes quiescence and chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancer. JCI Insight, 5(7). e131486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- d'Adhemar C.J., Spillane C.D., Gallagher M.F., Bates M., Costello K.M., Barry-O'Crowley J.…Romualdi C. The MyD88+ phenotype is an adverse prognostic factor in epithelial ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eferl R., Wagner E.F. AP-1: A double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2003;3(11):859–868. doi: 10.1038/nrc1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Z. H., Wu, K., Chen, Y. L., Wang, B., Zhang, S. R., & Ma, S. L. (2014). Capilliposide isolated from Lysimachia capillipes Hemsl. induces ROS generation, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis in human nonsmall cell lung cancer cell lines. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2014, 497456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hatina J., Boesch M., Sopper S., Kripnerova M., Wolf D., Reimer D.…Zeimet A.G. Ovarian cancer stem cell heterogeneity. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2019;1139:201–221. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-14366-4_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyvani V., Farshchian M., Esmaeili S.A., Yari H., Moghbeli M., Nezhad S.K., Abbaszadegan M.R. Ovarian cancer stem cells and targeted therapy. Journal of Ovarian Research. 2019;12(1):120. doi: 10.1186/s13048-019-0588-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.M., Lee S.Y., Yuk D.Y., Moon D.C., Choi S.S., Kim Y.…Hong J.T. Inhibition of NF-kappaB by ginsenoside Rg3 enhances the susceptibility of colon cancer cells to docetaxel. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2009;32(5):755–765. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-1515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koczurkiewicz P., Klaś K., Grabowska K., Piska K., Rogowska K., Wójcik‐Pszczoła K.…Pękala E. Saponins as chemosensitizing substances that improve effectiveness and selectivity of anticancer drug-Minireview of in vitro studies. Phytotherapy Research. 2019;33(9):2141–2151. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Zhang L., Zhang L., Chen D., Tian J., Cao L.i., Zhang L. Capilliposide C derived from Lysimachia capillipes Hemsl inhibits growth of human prostate cancer PC3 cells by targeting caspase and MAPK pathways. International Urology and Nephrology. 2014;46(7):1335–1344. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0641-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Yang, G., Bu, X., Liu, G., Ding, J., Li, P., & Jia, W. (2011). Cell-type-specific regulation of raft-associated Akt signaling. Cell Death and Disease, 2, e145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Macintyre G., Goranova T.E., De Silva D., Ennis D., Piskorz A.M., Eldridge M.…Brenton J.D. Copy number signatures and mutational processes in ovarian carcinoma. Nature Genetics. 2018;50(9):1262–1270. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0179-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng E., Long B., Sullivan P., McClellan S., Finan M.A., Reed E.…Rocconi R.P. CD44+/CD24- ovarian cancer cells demonstrate cancer stem cell properties and correlate to survival. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 2012;29(8):939–948. doi: 10.1007/s10585-012-9482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghbeli M., Moghbeli F., Forghanifard M.M., Abbaszadegan M.R. Cancer stem cell detection and isolation. Medical Oncology. 2014;31(9):69. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad N., Bhattacharya S., Steele R., Phillips N., Ray R.B. Involvement of c-Fos in the promotion of cancer stem-like cell properties in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2017;23(12):3120–3128. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhriyal, R., Hariprasad, R., Kumar, L. & Hariprasad, G. (2019). Chemotherapy resistance in advanced ovarian cancer patients. Biomarkers in Cancer, 11, 1179299X19860815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ruscito I., Darb-Esfahani S., Kulbe H., Bellati F., Zizzari I.G., Rahimi Koshkaki H.…Braicu E.I. The prognostic impact of cancer stem-like cell biomarker aldehyde dehydrogenase-1 (ALDH1) in ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Gynecologic Oncology. 2018;150(1):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z., Xu L., Li J., Zhang N.i. Capilliposide C sensitizes esophageal squamous carcinoma cells to Oxaliplatin by inducing apoptosis through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Medical Science Monitor. 2017;23:2096–2103. doi: 10.12659/MSM.901183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh J.M., Huang T.F., Hung C.F., Chou K.H., Tsai Y.J., Wu W.B. Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase is essential for mitochondrial membrane potential change and apoptosis induced by doxycycline in melanoma cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;160(5):1171–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vlerken, L. E., Kiefer, C. M., Morehouse, C., Li, Y., Groves, C., Wilson, S. D., Yao, Y., Hollingsworth, R. E. & Hurt, E. M. (2013). EZH2 is required for breast and pancreatic cancer stem cell maintenance and can be used as a functional cancer stem cell reporter. Stem Cells Translational Medicine, 2(1), 43-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yang B., Yan X., Liu L., Jiang C., Hou S. Overexpression of the cancer stem cell marker CD117 predicts poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer patients: Evidence from meta-analysis. OncoTargets and Therapy. 2017;10:2951–2961. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S136549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.