Abstract

Objective

Peptidyl alkaloids, a series of important natural products can be assembled by fungal non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs). However, many of the NRPSs associated gene clusters are silent under laboratory conditions, and the traditional chemical separation yields are low. In this study, we aim to discovery and efficiently prepare fungal peptidyl alkaloids assembled by fungal NRPSs.

Methods

Bioinformatics analysis of gene cluster containing NRPSs from the genome of Penicillium thymicola, and heterologous expression of the putative gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans were performed. Isolation, structural identification, and biological evaluation of the product from heterologous expression were carried out.

Results

The putative tri-modular NRPS AncA was heterologous-expressed in A. nidulans to give anacine (1) with high yield, which showed moderate and selective cytotoxic activity against A549 cell line.

Conclusion

Heterologous expression in A. nidulans is an efficient strategy for mining fungal peptidyl alkaloids.

Keywords: anacine, biosynthesis, non-ribosomal peptide synthetase, peptidyl alkaloid

1. Introduction

Natural products play a pivotal role in drug discovery and fungi have been proved to be important resource of bioactive natural products. Peptidyl alkaloids are a significant class of bioactive secondary metabolites with characteristic multicyclic, constrained rings in their chemical structures, and mainly produced in filamentous fungi (Walsh, Haynes, Ames, Gao, & Tang, 2013). Typical examples of peptidyl alkaloids included asperlicins as cholycystokinin antagonist (Liesch, Hensens, Zink, & Goetz, 1988), ardeemins with function of obstruction the multiple drug resistance in tumor cells (Boyes-Korkis et al., 1993, Hochlowski et al., 1993), as well as fumiquinazolines with diverse bioactivities (Takahashi et al., 1995).

Biosynthetically, the core scaffold of peptidyl alkaloids is assembled by short non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs), and then further modified via a series of tailoring enzymes to increase structural complexity and diversity, such as oxidation, acylation and pentenylation (Haynes et al., 2011, Yin et al., 2009). It was reported that NRPSs have ability to select, activate, and incorporate the nonproteinogenic amino acid anthranilate (Ant) as building block in peptidyl alkaloids biosynthesis, exampled by fumiquinazolines (Gao et al., 2012, Haynes et al., 2013). Therein, fumiquinazolines F (FQF), containing a 6–6–6 tricyclic core, has the simplest modification in this family. Biochemical characterization has confirmed that FQF is a tripeptidyl skeleton assembled by anthranilic acid (Ant), L-tryptophan (L-Trp), and L-alanine (L-Ala) (Ames, Liu, & Walsh, 2010). As one of the most structurally complex quinazoline alkaloids, alanditrypinone was characterized to be biosynthesized by only three enzymes in the Aldp cluster, where a tri-modular NRPS, AldpA, catalyzed the generation of a tripeptide 14-epi-FQF, then an α-KG-dependent oxygenase AldpC led to the formation of an iminium containing intermediate, and a mono-modular NRPS, AldpB, loaded an additional L-Trp moiety to construct the final structure (Yan et al., 2019).

In order to discover more peptidyl alkaloids from fungi, we commenced to mining gene clusters with tri-modular NRPS homologous to AldpA. When analyzing the gene clusters for natural product biosynthesis from the sequenced Penicillium thymicola genome, we found a new gene cluster (named Anc) containing a tri-modular NRPS which was supposed to be responsible for a fungal quinazoline tripeptidyl alkaloid biosynthesis with unknown structure. As Aspergillus nidulans has been established as a convenient expression host, which could increase the level of gene expression by strong/inducible promoters, amenable to large-scale fermentation, and easily manipulated (Nielsen et al., 2013, Ryan et al., 2013, Yin et al., 2013), it is a perfect host to express fungal natural products biosynthetic gene clusters.

Herein, we reported the genome mining, heterologous expression, and bioactivity of a fungal peptidyl alkaloid anacine, which presented the heterologous expression in A. nidulans as an efficient strategy for mining fungal natural products.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strains, and culture conditions

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The fungal strain Penicillium thymicola was grown at 25 °C on potato dextrose agar (PDA, BD). The Aspergillus nidulans strain was grown at 37 °C on glucose minimum medium (GMM) and were supplemented with uracil 0.56 g/L, uridine 1.26 g/L, 0.5 μmol/L pyridoxine HCl when appropriate. The heterologous expression strains were fermented at 25 °C in liquid starch minimum medium (LSMM), with the carbon source in GMM to 2% soluble starch, and 0.5% tryptone addition. All strains were maintained as glycerol stocks at −80 °C. Escherichia coli strain XL1-Blue was used for plasmid multiplication, grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates, supplemented when necessary with ampicillin (100 μg/mL). Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain was used for yeast homologous recombination.

Table 1.

Fungal strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains/Plasmids | Description/Aim |

|---|---|

| A.n-AncA | Overexpression AncA in A. nidulans |

| Penicillium thymicola | Genomic origin |

| Aspergillus nidulans | pyrG89, pyroA4, riboB2, heterologous host |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Yeast homologous recombination host |

| Escherichia coli XL1-Blue | Plasmids multiplication |

| pYTU | URA3, AMA1, glaA::AfpyrG, Amp |

| pYTP | URA3, AMA1, amyB::AfpyroA, Amp |

| pYTR | URA3, AMA1, gpdA::AfriboB, Amp |

| pYTU-AncA | AncA DNA in pANU under the control of glaA promoter |

2.2. Sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

The genomic DNA (gDNA) of P. thymicola was prepared from mycelium stationary grown on PDA at 25 °C for 7 d. The mycelia (100 mg) was grinded in liquid nitrogen, and then gDNA was extracted from the resulting cell powder using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method. Shotgun sequencing was performed at Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China) using Illumina Hiseq2000 platform. Gene clusters were predicted by antiSMASH (https://fungismash.secondarymetabolites.org) and 2ndFind (http://biosyn.nih.go.jp/2ndfind) analysis. The amino acid sequences of AncA (the target NRPS encoded by AncA in Anc cluster) were submitted to the web-based DOMAIN SEARCH PROGRAM for NRPS (http://www.nii.ac.in/~zeeshan/search_only_nrps.html) to analyze the functional domain. The 10-residue specificity sequence (10AA code) of A domain in NRPS was exacted with NRPSpredictor2 server (http://abi-services.informatik.uni-tuebingen.de/nrps2/Controller?cmd=SubmitJob) (Rottig, Medema, Blin, Weber, Rausch, & Kohlbacher, 2011), and aligned with other NRPSs. Sequence alignment analysis of the active sites of CT domains was performed using DNAMAN.

2.3. Gene amplification and plasmid construction

The plasmids utilized in this work were shown in Table 1. The PCR primers used were listed in Table 2. PCR reactions were performed with Q5® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs). The gene sequence of AncA was divided into three parts and amplified from the genomic DNA of P. thymicola, respectively. The plasmid pYTU was digested with PacI and NotI. All of the fragments and linearized vector were gel purified using AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen). The vector pYTU-AncA was constructed by in vivo yeast recombination. Three NRPS fragments and linearized vector pYTU were transformed into S. cerevisiae using yeast homologous recombination method as described by R Daniel Gietz subsequently (Gietz & Schiestl, 2007). All three DNA fragments for in vivo yeast recombination contained a minimum of 30 bp overlapping bases with the flanking fragments. The obtained yeast colonies were characterized by PCR. Yeast plasmids were isolated using Zymoprep™ (D2001) Kit (Zymo Research) and transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue cells. All plasmids were isolated using Axyprep Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Axygen) and confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion and sequencing.

Table 2.

PCR primer sets utilized in this study.

| Primers | Oligonucleotide sequences (5′−3′) | |

|---|---|---|

| For AncA amplification | AncA-P1 | CTTCATCCCCAGCATCATTACACCTCAGCATTAATTAAATGGCGGACTCTTGTTTATTT |

| AncA-P2 | GCCCACTTGCTCGTTAGG | |

| AncA-P3 | CTTGCTGGAATTGAGGAGAT | |

| AncA-P4 | GAAATAAAGTGGCACGAAAGT | |

| AncA-P5 | GATTGTGAAGAAATGCCTCG | |

| AncA-P6 | CTGCAGCCCGGGGGATCCACTAGTTCTAGAGCGGCCGCGCGTCGTCGTAGATTGGAT | |

| For transformant screening | AncA-test1-F | TTCCTGGAGACGAACTGGT |

| AncA-test1-R | TAGGAGACCGCTTGATGTAG | |

2.4. Transformation of A. nidulans

A. nidulans strain was used as the recipient host. Fungal protoplast preparation and transformation were performed as the description from our laboratory (Yan et al., 2019). The plasmids pYTU-AncA, pYTR and pYTP were co-transformation into A. nidulans to own the AncA overexpression strain A.n-AncA. Co-Transformation with plasmids pYTU, pYTR and pYTP were used as control. Transformants were verified using diagnostic PCR with appropriate primers (Table 2).

2.5. Fermentation and LC-MS analysis

A. nidulans strain A.n-AncA was cultivated at 25 °C, 180 rpm in 5 mL liquid CD-ST medium (GMM liquid medium containing 20 g/L starch without glucose, 2% tryptone is added) for 5 d. The broth (2 mL) was extracted three times with ethyl acetate (EtOAc), the supernatant organic phase gave an oily residue (Labconco Corporation, Dry Evaporators, Concentrators & Cold Traps, MO, USA). The dried material was dissolved in 150 μL of acetonitrile (MeCN) and subjected to LC-MS analysis.

LC-MS were performed on a Waters ACQUITY H-Class UPLC-MS with QDA mass detector (ACQUITY UPLC® BEH, 1.7 μm, 50 mm × 2.1 mm, C18 column) using positive and negative mode electrospray ionization. LCMS grade MeCN and H2O (both with 0.02% formic acid, volume percentage) were used as the mobile phases. The solvent gradient for LC-MS analyses changed as follows: 0–8 min 5%−99% MeCN, 8–12 min 99% MeCN, with a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min.

2.6. Extraction, purification and identification of product from heterologous expression

The desired product was purified from A.n-AncA 7 d cultures in 3 L liquid CD-ST medium. The aqueous phase was filtered from the fermentation broth and then extracted with analytical grade EtOAc (1:1, volume percentage) for three times to offer the EtOAc extract. After evaporation of the organic phase, the EtOAc extract was re-dissolved with HPLC grade MeOH and concentrated by centrifugation to give the MeOH-soluble extract (452.5 mg). The MeOH-soluble extract was fractionated by semi-preparative HPLC with a DAD detector (SSI series 1500, CoMetro Technology Ltd., NJ, USA) and using a Shiseido Capcell Pak 250 × 10 mm 5 μm C18 column. The target compound (1) was isolated by semi-prepared HPLC (MeCN: H2O = 30: 70, flow: 3 mL/min, tR = 14 min) with final yield of 35.23 mg/L. The obtained pure compound was performed NMR analysis at 500 MHz for 1H NMR and 125 MHz for 13C NMR, on an Inova 500 instrument (Varian Associates Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) in CDCl3 with solvent peaks used as references.

2.7. Biological assays

Cytotoxic activities against PC3 (human prostate cancer cell line), MDA-MB-231 (human breast cancer cell line), MCF-7 (human breast cancer cell line), A549 (human lung adenocarcinomic cell line), HL-60 (human leukemia cell line) and THP-1 (human leukemia cell line) cancer cell lines were assayed using the MTT method. All the cells were maintained in Hyclone 1640 or DMEM (low glucose) supplemented with 10% FBS and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The cells were harvested using trypsin and diluted to 1.5–3.0 × 104/mL, then seeded 100 μL of cells per well in 96-well plates and incubated 24 h. Different concentrations (final concentrations were 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5 and 10 μmol/L) of compound 1 were added into the wells in triplicate and then incubated for 96 h. After added 20 μL of MTT (5 mg/mL) into each well, the plates were continue incubated for an additional 4 h. The cells were gently replaced by 200 μL of DMSO and treated on shaker for 10 min, the absorbance was measured at OD = 570 nm with reference at OD = 630 nm on a microplate reader (Synergy-HT, Bio-Tek) subsequently. A total of 200 μL of DMSO was used as control.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Anc gene cluster containing a tri-modular NRPS by bioinformatic analysis

To identify more peptityl alkoilds from fungi, we analyzed gene clusters containing NRPSs from the sequenced P. thymicola genome, and found a gene cluster with a single tri-modular NRPS (named Anc cluster). The Anc cluster encodes a NRPS (AncA) with a domain sequence of A1-T1-C1-A2-T2-C2-A3-T3-CT, and there are no genes encoding redox enzymes around AncA (Fig. 1), which suggested that AncA has potential to activate three amino acids and yield a tripeptide alkaloid without any modification.

Fig. 1.

Gene cluster of Anc.

Prediction of the 10AA code in AncA is useful for identification of the putative ant-activating modules. The amino acid sequence of AncA was submitted to the web-based NRPSpredictor2, and the 10AA code of the first A domain was extracted as GIILlAAGIK. The 10AA codes of AncA and other selected A domains were compared in Table 3. The 10AA code of AncA (A1) was similar to NFIA_057960 (A1) (90%), AldpA (A1) (90%), CtqA (A1) (90%) and AFUA_6g12080 (A1) (80%). Compared with 10AA codes of other nine fungal A domains (A1), the residues positions (Pos) 1 and 8 of AncA were strict conservation glycines, and the distinct residues at positions 2, 4, 5 and 9 are variable hydrophobic residues, which were in consistent with the conclusion (Ames & Walsh, 2010). Thus, module 1 (A1-T1) of AncA was likely to be responsible for selection, activation, and loading of anthranilic acid. AncA was proposed to activate anthranilate (Ant), and two other amino acids, to yield a tripeptide started with Ant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of 10-residue specificity sequences for selecting NRPS adenylation domains.

| Names (module) | Pos1 (235) | Pos2 (236) | Pos3 (239) | Pos4 (278) | Pos5 (299) | Pos6 (301) | Pos7 (322) | Pos8 (330) | Pos9 (331) | Pos10 (517) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFIA_057960(A1) | G | I | I | L | G | A | A | G | I | K |

| AnaPS/NFIA_055290(A1) | G | A | L | F | F | A | A | G | V | K |

| ACLA_017890(A1) | G | V | I | F | L | A | A | G | V | K |

| ACLA_076770(A1) | G | V | I | F | V | A | G | G | V | K |

| ACLA_095980(A1) | G | V | I | I | L | A | G | G | L | K |

| TqaA (A1) | G | V | I | F | M | A | A | G | V | K |

| AFUA_6g12080(A1) | G | V | I | I | L | A | A | G | I | K |

| AldpA(A1) | G | I | I | L | G | A | A | G | I | K |

| CtqA (A1) | G | I | I | L | G | A | A | G | I | K |

| AncA (A1) | G | I | I | L | L | A | A | G | I | K |

| Consensusa | G | Xh | I/L | Xh | Xh | A | A/G | G | Xh | K |

The abbreviation “Xh” stands for variable hydrophobic residues.

Sequence alignment analysis of the active sites of CT domains in AncA with other fungal NRPSs C domains (using the CT domains from AFUA_6g12080, TqaA, AldpA and CtqA, the fungal NRPSs which can produce macrocyclic peptidyl products) were shown in Fig. 2. The CT domain in AncA contained highly conserved HXXXDXXS motif, and was responsible for the macrocyclization reaction (Gao et al., 2012).

Fig. 2.

Sequence alignment analysis of active sites of CT domain with other fungal NRPSs C domains.

3.2. Heterologous expression of AncA in A. nidulans led to production of anacine

To investigate the product encoded by this tri-modular NRPS, we expressed the putative gene cluster in A. nidulans, an established heterologous expression system for production of cryptic natural products. The gene AncA was amplified from gDNA and then cloned directly into pYTU which contains an inducible strong glaA promoter using yeast recombination. Following PCR verification of the integration of pYTU-AncA, the strain A.n-AncA was cultivated in CD-ST media, and the metabolites were extracted and analyzed by LC-MS (Fig. 3A), where a new metabolite (tR = 3 min) with m/z = 343 [M + H]+ was observed compared to the control (Fig. 3C). The new metabolite (1) was purified as amorphous powder (452.5 mg) from the crude extract and fully characterized by NMR analyses (Fig. 4). The 1D NMR spectra data (Table 4) indicated the presence of one ortho-disubstituted benzene ring, three carbonyls, four aromatic protons, three methines, three methylenes, and two methyl groups. Also, the 13C NMR data (Table 4) also revealed the presence of two olefinic groups at δC 126.6, 127.0, 127.3, and 135.1. Comparison of the observed and reported spectroscopic data, compound 1 was identified as anacine, a known natural compound previously found in P. aurantiogriseum (Wang & Sim, 2001). Based on the specific optical rotation ([α]24 D + 142.9, c 0.02 in MeOH), the absolute configuration of 1 could be confirmed. The identified configuration of 1 was also consistent with the feature that no E domain in the tri-modular NRPS AncA. Although 1 was identified as known compound, heterogeneous expression was able to obtain sufficient amount of material for biological assay.

Fig. 3.

LC-MS analysis of A. nidulans heterologous transformants. LC-MS analysis of A. nidulans strains (A). UV absorption of compound 1 (B). Positive and negative masses of compound 1 (C), m/z 343.02 [M + H]+, 341.12 [M - H]-.

Fig. 4.

Structure of compound 1.

Table 4.

1H and 13C NMR data of compound 1 (CDCl3)b.

| Positions | δC | δH (J/Hz) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 168.3 | / |

| 2 | / | / |

| 3 | 54.9 | 4.62 dt (9.6, 4.6) |

| 4 | 151.2 | / |

| 5 | / | / |

| 6 | 147.0 | / |

| 7 | 127.0 | 7.65 d (8.3) |

| 8 | 135.1 | 7.75 t (8.3, 7.1) |

| 9 | 127.3 | 7.47 t (7.8, 7.1) |

| 10 | 126.9 | 8.23 d (7.8) |

| 11 | 119.4 | / |

| 12 | 160.9 | / |

| 13 | / | / |

| 14 | 54.9 | 5.21 dd (10.0, 5.4) |

| 15a | 29.5 | 2.38 m |

| 15b | / | 2.22 m |

| 16 | 32.4 | 2.68 t (7.1) |

| 17 | 174.2 | / |

| 18 | 47.2 | 1.93 m |

| 19 | 24.8 | 1.93 m |

| 20 | 23.4 | 1.05 dt (6.2, 3.0) |

| 21 | 21.3 | 1.05 dt (6.2, 3.0) |

1H and 13C spectra were obtained at 500 and 125 MHz, respectively.

3.3. Biological evaluation of anacine (1)

The cytotoxicities of anacine (1) were evaluated against a series of cancer cell lines by MTT method, including PC3, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7, A549, as well as HL-60 and THP-1, with doxorubicin as positive control. Anacine showed moderate cytotoxic activity against A549 cell (IC50 = 17.3 μmol/L), which was weaker than that of positive control (IC50 = 0.1 μmol/L). Anacine was inactive against other tested cancer cell lines.

4. Discussion and conclusion

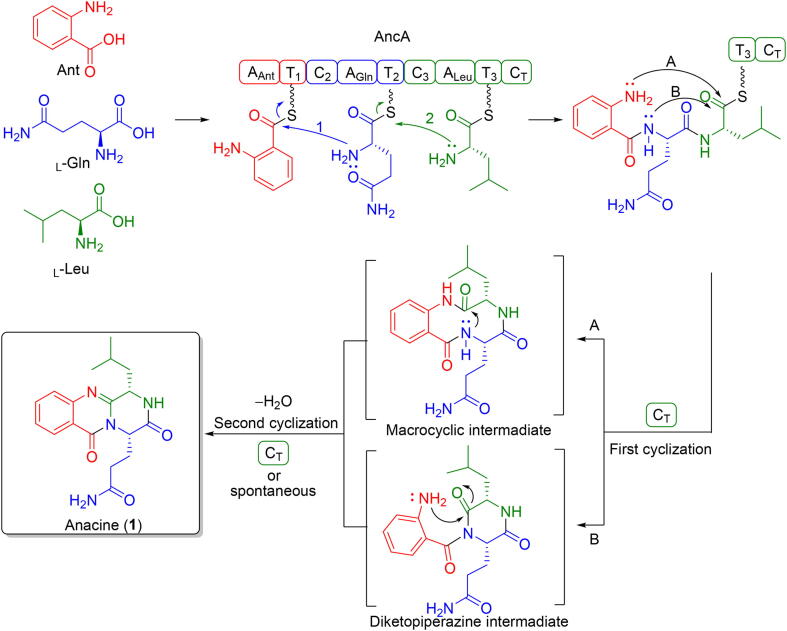

Anacine was firstly identified as benzodiazepine alkaloids from P. aurantiogriseum. Later investigation indicated that anacine had a quinazoline instead of a benzodiazepine core, which was further confirmed by total synthesis (Wang & Sim, 2001). Biosynthetically, it can be synthesized by a tri-modular NRPS with three adenylation domains that incorporates anthranilate (Ant), L-glutamine (L-Gln) and L-leucine (L-Leu). The proposed biosynthetic mechanisms of anacine (1) were shown in Fig. 5. Non-ribosomal peptide synthetase AncA with three modules are responsible for the assembly of the tricyclic scaffold via a process from recognition of Ant to upload the L-Gln and L-Leu in turn. Nucleophilic attack from Ant-free amine to the thioester carbonyl contributes to achieve cyclization and release of the product. As the final step, there are two possible routs of cyclization catalyzed by CT domain in the formation of anacine (1). In route A, the Ant amine attacks on the thioester carbonyl to yield a macrocyclic intermediate, which can later give rise to the ancine (1) through a bridging amide bond cyclization and dehydration. In route B, the L-Gln amide act as an initial nucleophile attacks on the thioester carbonyl to yield a diketopiperazine (DKP) intermediate. Subsequently, The Ant amine and the L-Leu amide carbonyl undergo intramolecular attack and dehydration to form anacine (1).

Fig. 5.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of anacine (1).

Anacine has been reported to be produced by strain P. aurantiogriseum with a yield of 0.4 mg/L (Boyes-Korkis et al., 1993, Xin et al., 2007). Here, we obtained this compound with high yield (35.23 mg/L) through concise biosynthesis by only one single tri-modular NRPS. Our research also supported that heterologous biosynthesis is an efficient strategy for mining cryptic gene clusters from fungi and to obtain enough material of minor secondary metabolites.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported financially by the Drug Innovation Major Project (No. 2018ZX09711001-006) and the CAMS Initiative for Innovative Medicine (No. 2017-I2M-4-004). We are grateful to the Department of Instrumental Analysis, Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College for the spectroscopic measurements.

References

- Ames B.D., Liu X., Walsh C.T. Enzymatic Processing of Fumiquinazoline F: A Tandem Oxidative-Acylation Strategy for the Generation of Multicyclic Scaffolds in Fungal Indole Alkaloid Biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 2010;49(39):8564–8576. doi: 10.1021/bi1012029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames B.D., Walsh C.T. Anthranilate-Activating Modules from Fungal Nonribosomal Peptide Assembly Lines. Biochemistry. 2010;49(15):3351–3365. doi: 10.1021/bi100198y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Haynes S.W., Ames B.D., Wang P., Vien L.P., Walsh C.T., Tang Y.i. Cyclization of fungal nonribosomal peptides by a terminal condensation-like domain. Nature Chemical Biology. 2012;8(10):823–830. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz R.D., Schiestl R.H. High-efficiency yeast transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nature Protocols. 2007;2(1):31–34. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes S.W., Ames B.D., Gao X., Tang Y.i., Walsh C.T. Unraveling Terminal C-Domain-Mediated Condensation in Fungal Biosynthesis of Imidazoindolone Metabolites. Biochemistry. 2011;50(25):5668–5679. doi: 10.1021/bi2004922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes S.W., Gao X., Tang Y.i., Walsh C.T. Complexity Generation in Fungal Peptidyl Alkaloid Biosynthesis: A Two-Enzyme Pathway to the Hexacyclic MDR Export Pump Inhibitor Ardeemin. ACS Chemical Biology. 2013;8(4):741–748. doi: 10.1021/cb3006787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochlowski J.E., Mullally M.M., Spanton S.G., Whittern D.N., Hill P., Mcalpine J.B. 5-N-Acetylardeemin, a novel heterocyclic compound which reverses multiple drug resistance in tumor cells. II. Isolation and elucidation of the structure of 5-N-acetylardeemin and two congeners. Journal of Antibiotics. 1993;46(3):380–386. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesch, J. M., Hensens, O. D., Zink, D. L., & Goetz, M. A. (1988). Novel cholecystokinin antagonists from Aspergillus alliaceus. II. Structure determination of asperlicins B, C, D, and E. Journal of Antibiotics, 41(7), 878–881. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Boyes-Korkis J.M., Gurney K.A., Penn J., Mantle P.G., Bilton J.N., Sheppard R.N. Anacine, a new benzodiazepine metabolite of Penicillium aurantiogriseum produced with other alkaloids in submerged fermentation. Journal of Natural Products. 1993;56(10):1707–1717. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M.T., Nielsen J.B., Anyaogu D.C., Holm D.K., Nielsen K.F., Larsen T.O., et al. Heterologous reconstitution of the intact geodin gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans through a simple and versatile PCR based approach. PLoS One. 2013;8(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottig, M., Medema, M. H., Blin, K., Weber, T., Rausch, C., & Kohlbacher, O. (2011). NRPSpredictor2--a web server for predicting NRPS adenylation domain specificity. Nucleic Acids Research, 39(Web Server issue), W362-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ryan K.L., Moore C.T., Panaccione D.G. Partial reconstruction of the ergot alkaloid pathway by heterologous gene expression in Aspergillus nidulans. Toxins (Basel) 2013;5(2):445–455. doi: 10.3390/toxins5020445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi C., Matsushita T., Doi M., Minoura K., Shingu T., Kumeda Y., et al. Fumiquinazolines A-G, novel metabolites of a fungus separated from a Pseudolabrus marine Fish. Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions. 1995;1:2345–2353. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C.T., Haynes S.W., Ames B.D., Gao X., Tang Y. Short pathways to complexity generation: Fungal peptidyl alkaloid multicyclic scaffolds from anthranilate building blocks. ACS Chemical Biology. 2013;8(7):1366–1382. doi: 10.1021/cb4001684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang., H., & Sim., M. M. (2001). Total solid phase syntheses of the quinazoline alkaloids: Verrucines A and B and anacine. Journal of Natural Products, 64(12), 1497–1501 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xin Z.H., Fang Y., Du L., Zhu T., Duan L., Chen J., et al. Aurantiomides A−C, quinazoline alkaloids from the sponge-derived fungus Penicillium aurantiogriseum SP0-19. Journal of Natural Products. 2007;70(5):853–855. doi: 10.1021/np060516h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D., Chen Q., Gao J., Bai J., Liu B., Zhang Y., et al. Complexity and diversity generation in the biosynthesis of fumiquinazoline-related peptidyl alkaloids. Organic Letters. 2019;21(5):1475–1479. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W., Chooi Y.H., Smith A.R., Cacho R.A., Hu Y., White T.C., et al. Discovery of cryptic polyketide metabolites from dermatophytes using heterologous expression in Aspergillus nidulans. ACS Synthetic Biology. 2013;2(11):629–634. doi: 10.1021/sb400048b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W., Grundmann A., Cheng J., Li S. Acetylaszonalenin biosynthesis in Neosartorya fischeri. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(1):100–109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]