Abstract

Panax japonicus, which in the Tujia dialect is known as “Baisan Qi” and “Zhujieshen”, is a classic “qi” drug of Tujia ethnomedicine and it has unique effects on disease caused by “qi” stagnation and blood stasis. This paper serves as the basis of further scientific research and development of Panax japonicus. The pharmacology effects of molecular pharmacology were discussed and summarized. P. japonicus plays an important role on several diseases, such as rheumatic arthritis, cancer, cardiovascular agents, and this review provides new insights into P. japonicus as promising agents to substitute ginseng and notoginseng.

Keywords: chikusetsusaponin, ginsenoside, Panax ginseng C. A. Mey, Panax japonicas (T. Nees) C. A. Meyer, Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F. H. Chen

1. Introduction

Panax japonicus (T. Nees) C. A. Meyer (Fig. 1), which in the Tujia dialect is known as “Baisan Qi” and “Zhujieshen”, is a classic “qi” drug of Tujia ethnomedicine and it has unique effects on disease caused by “qi” stagnation and blood stasis. Modern research suggests that P. japonicus plays an important role on several diseases, such as rheumatic arthritis, cancer, and cardiovascular agents. In 2000, it was included in Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China. It is said that P. japonicus rhizomes possess conserving vitality activities of Panax ginseng C. A. Mey and replenishing blood activities of Panax notoginseng (Burkill) F. H. Chen ex C. H. simultaneously (Zhang et al., 2015). It was traditionally used as P. ginseng for enhancing immunity, in addition, it can be applicated in rheumatic arthritis as P. notoginseng (Yang et al., 2014). Thus, P. japonicus rhizomes were also named as “the king of herbs” in traditional Tujia and Hmong medicines.

Fig. 1.

Whole plants (A), flowers (B), fresh fruits (C), and dried roots (D) of P. japonicus.

Triterpenoid saponins are important active components and usually named ginsenoside in Panax species (Yi, 2019). Many pharmacological effects of ginsenoside are reported to play critical roles in preventing and treating many human diseases, including cancers, neuronal, cardiovascular, inflammatory, immunity adjustment, and metabolic diseases (Lee & Kim, 2014; Lee, Park, & Cho, 2019; Mohanan, Subramaniyam, Mathiyalagan, & Yang, 2018). Dammarane-type triterpenoid saponins are abundant in ginseng and notoginseng. Therefore, most of researches were focused on dammarane-type triterpenoid saponins other than oleanane-type and lots of review concerned about ginsenosides are actually dammarane-type triterpenoid saponins (Zhu, Zou, Fushimi, Cai, & Komatsu, 2004). P. japonicus also possessed considerable amount of saponins including dammarane-type and oleanane-type, especially oleanane-type saponins (Zhu, Zou, Fushimi, Cai, & Komatsu, 2004). The total saponin content in the roots of P. japonicus can reach 15%, which is 2- to 7-fold higher than that of P. ginseng. Due to the unique traditional utilization of P. japonicus, in recent years, main researches were conducted on main saponins from it. Hence, in this review, pharmacology effects of molecular signaling and clinical application of chikusetsusaponins from P. japonicus were discussed and summarized.

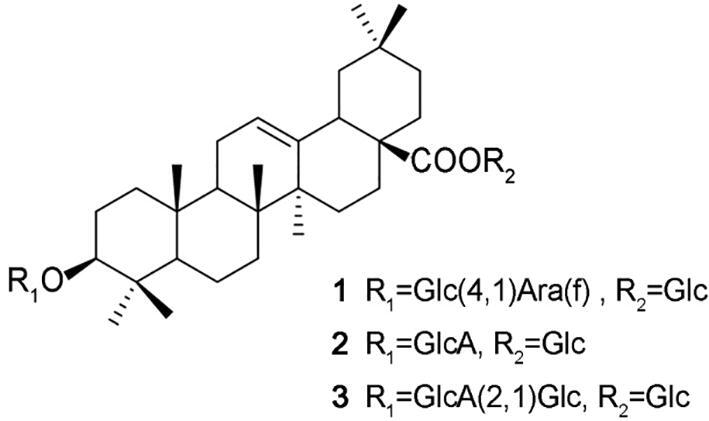

Triterpenoid saponins (SPJ) are the most abundant and main active components of P. japonicus, mainly including dammarane and oleanane-type triterpenoid saponins. Triterpenoid saponins in P. ginseng are usually dammarane-type sapoins and called ginsenoside, such as ginsenoside Rb1, ginsenoside Ro, and ginsenoside Rg3. In the primary time, triterpenoid saponins found in P. japonicus are oleanonic type saponins and called chikusetsusaponin by Japan researchers, such as chikusetsusaponin IV, chikusetsusaponin V and chikusetsusaponin IVa, and then most of ginsenosides were also isolated from P. japnonicus (Liu et al., 2015, Noriko et al., 1971, Tzong et al., 1976, Zou, Zhu, Tohda, Cai, & Komatsu, 2002). Totally, there are four kinds of triterpenoid saponin found in Panax species nowadays (Liu et al., 2017, Yoshizaki et al., 2012, Yoshizaki & Yahara, 2012). The contents of oleanane triterpenoids are abundant, >85% of which composed the saponins of P. japonicus, but dammarane saponin are with more varieties (Yoshizaki et al., 2013, Zhu, Zou, Fushimi, Cai, & Komatsu, 2004). Chikusetsusaponin IV (1), chikusetsusaponin V (2) (same as ginsenosides Ro), and chikusetsusaponin IVa (3) are the main oleanane-type triterpenoid saponins of P. japonicus (Fig. 2) (Liu et al., 2015, Liu et al., 2016, Zhu, Zou, Fushimi, Cai, & Komatsu, 2004). Other oleanane-type triterpenoid saponins, such as chikusdtsusaponin IVa derivatives, also possess diverse bioactivities. The three compounds not only exist in P. japonicus, but also in other plants, such as Achyranthes bidentata Blume., Aralia taibaiensis Z. Z. Wang et H. C. Zheng (Dahmer et al., 2012, Jaiswal et al., 2018, Li et al., 2018, Zhang et al., 2015). These plants are used for thousands years in traditional Chinese medicine. Moreover, the three compounds are reported to possess many kinds of pharmacological activities (Cao et al., 2017, Weng et al., 2014, Xu et al., 2014). Here we discuss the activities of chikusetsusaponins so as to get comprehensive information of P. japonicus (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Main chikusetsusaponin in P. japonicus.

Fig. 3.

Brief summary of associated pathways and targets of P. japonicas.

2. Pharmacological activities

2.1. Antitumor activity

Oleanane triterpenoids exhibit cytotoxic activity against various types of cancer cells (Liby, Sporn, & Esbenshade, 2012, Liu et al., 2013). Chikusetsusaponins belongs to oleanane triterpenoids and many studies reported its anticancer activities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Anticancer activities of chikusetsusaponins.

| No. | Components | Cell lines or models | Doses | Functions | Target molecules | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ginsenoside Ro | HT29 cells, Female BALB/c mice | 0, 1, 20, 50, 100 μg/mL (24 h); 25, 250 mg/kg, 40-day oral (in vivo) | No toxicity (100 μg/mL); Inhibit migration and invasion ability (100 μg/mL); produced a signifcant decrease in the number of tumor nodules on the lung surface (in vivo) | (↓) αvβ6, MMP-2, MMP-9, ERK phosphorylation | (Jiang et al., 2017) |

| 2 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa methyl ester | HCT116 cells | 0, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 μmol/L for 24 h | Inhibit cell proliferation at the G0/G1 phase (>20 μmol/L), Inhibits the binding of beta-catenin to specific DNA sequences (TCF binding elements, TBE) in target gene promoters (30 μmol/L). | Inhibited Wnt/β-catenin pathway, (↓) β-catenin in nucleus,disrupted β-catenin nuclear translocation and repressed the transcriptional activity of β-catenin, (↓) Cyclin D1(representative target for beta-catenin, CDK2 and CDK4) | (Lee et al., 2015) |

| 3 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa | SK-Hep-1 cells | Crude 50, 100, and 300 for 18 h | IC50 value = 18.9 μg/ml; Control: cisplatin (IC50 = 12.7 μg/mL) Crude Achyranthes Roots (IC50 > 300 μg/mL) and Heat Processed Achyranthes Roots (IC50 = 99.8 μg/mL) | No report | (Yoo, Kwon, & Park, 2006) |

| 4 | Deglucose chikusetsusaponin IVa | HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cell | 0.02, 0.04,0.06,0.08,1.0 μmol/mL (24 h) | Inhibited growth of cell line and viability in dose-dependent manner; Induced chromatin condensation, margination and apoptotic body formation; Increased cell apoptosis and induced G2/M cell cycle arrest | (↑) Bax, (↓) Bcl-2 | (Song et al., 2015) |

| 5 | Plant powder | Male Sprague-Dawley rats induced by diethylnitrosamine | 2 g/100 g, perform a two-thirds partial hepatectomy (PH) after 3 weeks, treat orally for 10 weeks | The number of proliferating cell nuclear antigen–positive hepatocytes in the GST-P–positive area was significantly decreased in the fresh ginseng group but not in the Panax japonicus CA Meyer or P. quinquefolius L groups | No report | (Kim et al., 2013) |

| 6 | Oleanolic acid 3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-β-D-glucuronopyranosyl-6′-O-n-butyl ester | A2780 cells; OVCAR-3 cells |

IC50 value = 21.1 mg/mL; IC50 values = 35.2 mg/mL |

No report | (Zhao et al., 2010) | |

| 7 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa methyl ester | A2780 cells, HEY cell | 0, 4, 10 μmol/L; 0, 4, 10, 20 μmol/L; (24 h) |

A2780 cells IC50 value = 7.43 ± 1.55 μmol/L; HEY cells IC50 value = 7.94 ± 1.72 μmol/L induced G1 cell cycle arrest (10um); the condensation and fragmentation of the nuclei were observed (20 μmol/L), inhibition of migration and invasion (20 μmol/L) |

(↓) cyclin D1, CDK2, CDK6; (↓) Bcl-2, (↑) Bax, (↑) cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase 3, (↓)Cdc42, Rac, RohA, MMP2, MMP9 (20 uM) | (Chen et al., 2016) |

| 8 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa | PC-3, LNCaP, DU145; RWPE-2 cell; male, Athymic nude mice |

0, 12.5, 25, 50 umol/L (24 h); 100 mmol/L for 48 h; 15 mg/kg, 30 mg/kg, 60 mg/kg, orally for 7 weeks |

Suppresses prostate cancer cell proliferation and enhances cell death a dose- and time-dependent manner (>12.5 mmol/L); without cytotoxicity in prostate normal cells (100 mmol/L for 48 h); prostate tumor was inhibited through apoptosis induction in vivo | (↓) ROS production in intracellular, released cyto-c, apoptosis in Caspases-dependent and independent ways; (↑) Caspases, (↑) AIF, (↑) Endo G translocation |

(Zhu, Tian, & Liu, 2017) |

| 9 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa butyl ester | MDA-MB-231 cells, MCF-7 | 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 μmol/L for 24 h | Induced cancer cell apoptosis, synergizes with TRAIL in breast cancer cells | IL-6R antagonist, inhibits IL-6/STAT3 signaling, (↑) DR5 | (Yang et al., 2016) |

| 10 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa methyl ester (a), chikusetsusaponin IVa butyl ester (b) | MCF-7, A549, A354-S2, HeLa | treated with drugs for 48 h | aIC50 value = 35.6; 38.1; 26.8; 14.3 ug/mL; bIC50 value = 5.2; 3.1; 4.3; 1.4 ug/mL; | No report | (Wang, Lu, Lv, Xu, & Jia, 2012) |

| 11 | Panajaponol A | KB celll lines, DU145 cell lines | 3 d | GI50 values = 6.3 μg/ml GI50 values = 7.3 μg/ml |

No report | (Chan et al., 2011) |

2.1.1. Colorectal cancer

Ginsenoside Ro (chikusetsusaponin V) can inhibit the lung metastatic transmission capability of colon cancer cells HT29, including migration and invasion, and adhesion ability to human endothelium through inhibiting integrin αvβ6, MMP-2, MMP-9, and ERK phosphorylation without toxicity (Jiang et al., 2017). Chikusetsusaponin IVa methyl ester (CSME) can inhibit the growth of HCT116 cells as a novel Wnt/beta-catenin inhibitor. CSME reduces the amount of beta-catenin in nucleus and inhibits the binding of beta-catenin to specific DNA sequences (TCF binding elements, TBE) in target gene promoters. Therefore, CSME inhibits cell proliferation by arresting the cell cycle at the G0/G1 phase after decreasing the cell cycle regulatory proteins, such as Cyclin D1 (a representative target for beta-catenin, CDK2 and CDK4) (Lee et al., 2015).

2.1.2. Liver cancer

Chikusetsusaponin IVa are reported against SK-Hep-1 cells with IC50 value of 18.9 mg/mL and it was comparable to that of cisplatin (IC50 = 12.7 mg/mL) (Yoo, Kwon, & Park, 2006). Deglucose chikusetsusaponin IVa (DCIVa) inhibited cell growth of HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cell line and viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner using an MTT assay. DCIVa lead to chromatin condensation and margination at the nuclear periphery, and apoptotic body formation. Moreover, Hoechst 33,258 staining showed nuclear condensation and fragmentation. Furthermore, DCIVa increased cell apoptosis and G2/M cell cycle arrest, in addition enhanced the expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax, and deceased the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 (Song et al., 2015).

A research presented that fresh ginseng, induces cell cycle arrest in hepatocarcinogenesis, but fresh rhizomes of P. japonicus cannot. In their studies fresh rhizomes of P. japonicus have no effect on reducing the area and number of glutathione S-transferase P (GST-P)-positive foci compared with the diethylnitrosamine control group. In addition, P. japonicus did not decrease the number of proliferating cell nuclear antigen-positive hepatocytes in the GST-P-positive area. In addition, the p53 signaling pathway was not altered and the expression of Cyclin D1, Cyclin G1, Cdc2a and Igf-1 was downregulated by the ginseng but not P. japonicus diet (Kim et al., 2013). By contrast, heat processed extracts of P. japonicas showed suppression of DEN-induced hepatocarcinogenesis at the same concentrations of ginseng components. Heat processing may cause structural changes in ginsenosides and improve absorption rate, consequently, enhance biological activities and effectiveness and. Hye Hyun YOO (Yoo, Kwon, & Park, 2006) also reported heating-process can improve the content of chikusetsusaponin IVa in the BuOH-Soluble fraction and enhance cytotoxic activity.

2.1.3. Ovarian cancer

Compound oleanolic acid 3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-β-D-glucuronopyranosyl-6′-O-n-butyl ester are reported moderate antitumor activities against the A2780 cells and OVCAR-3 cells with IC50 values of 21.1 and 35.2 mg/mL, respectively, but the mechanism research was not conducted (Zhao et al., 2010).

Chikusetsusaponin IVa methyl ester (CSME) exhibited anti-proliferative with the IC50 values at less than 10 μmol/L in both ovarian cancer A2780 and HEY cell lines. In addition, CSME induced G1 cell cycle arrest accompanied with an S phase the cell mitochondrial membrane potential decrease and increased the annexin V positive cells and nuclear chromatin condensation, as well as enhanced the expression of cleaved PARP, Bax and cleaved Caspase-3 while decreasing that of Bcl-2. Moreover, mechanism research proved CSME suppressed the proliferation, migration and invasion of ovarian cancer A2780 and HEY cell lines though downregulating the expression of cyclin D1, CDK2, CDK6, Cdc42, Rac, RohA, MMP2 and MMP9, and decreased the enzymatic activities of MMP2 and MMP9 (Chen et al., 2016).

2.1.4. Prostate cancer

Chikusetsusaponin IVa (CHIVa) resulted in intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and induced apoptosis regulated by mitochondria in vitro studies in both caspase-dependent and -independent manner, which released cyto-c, enhancing caspases expression and promoting apoptosis-inducing factors (AIF) as well as endonuclease G (Endo G) nuclear transfer, respectively. Moreover, prostate tumor was inhibited by CHIVa treatment through apoptosis induction in vivo study (Zhu, Tian, & Liu, 2017). CHI inhibits prostate cancer cell proliferation and induces cell death without cytotoxicity in prostate normal cells, which means P. japonicus is a safe agent against prostate cancer.

2.1.5. Other cancers

The activation of IL6/STAT3 signaling is associated with the pathogenesis of many cancers, which means agents that suppress IL6/STAT3 signaling have cancer-therapeutic potential. CS-IVa-Be can inhibit IL6-IL6Rα-GP130 interaction and showed higher affinity to IL6Rα than to LIFR and Leptin R. CS-IVa-Be as a IL-6R antagonist not only directly induced cancer cell apoptosis but also enhanced MDA-MB-231 cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis via upregulating DR5 (Yang et al., 2016). Chikusetsusaponin IVa methyl ester, chikusetsusaponin IVa butyl ester and panajaponol A are reported cytotoxicity against MCF-7, A549, A354-S2, HeLa, KB cell lines and DU145 cell lines, but mechanisms are unclear (Chan et al., 2011, Wang, Lu, Lv, Xu, & Jia, 2012).

From above, we can conclude that mechanism of anticancer activities of P. japonicus mainly involve inhibition of cell proliferation, promotion of apoptosis, suppression of invasion and migration (Fig. 4). In current research chikusetsusaponins inhibit cell cycle arrest by CDK family protein thereby suppress the growth of tumor cells. Furthermore, promoting apoptosis are mainly concerned with mitochondrial control pathway, such as Caspase-3, Bcl-2, Bax, PARP, Endo G, and AIF. In addition, inflammation is considered a well-established cancer risk factor that leads to genetic and epigenetic damage, as well as unnatural activation of oncogenes, which causes cancer progression and malignant phenotypes of remodeling, angiogenesis, metastasis, and suppression of innate immune responses (Ahuja, Kim, Kim, Yi, & Cho, 2018). Chikusetsusaponin IVa butyl ester as a IL-6R antagonist can induce cancer cell apoptosis through inhibiting IL-6/STAT3 pathway. Since the treatments for cancer are typically unsuccessful due to drug resistance and metastasis, seeking new potential anti-cancer agents is highly desirable. P. japonicus can inhibit invasion and migration through downregulating the expression protein MMP2, ERK phosphorylation, and MMP9. We can conclude the anticancer effect of P. japonicus was realized by multiple components and multiple targets.

Fig. 4.

Possible mechanism for anticancer activities of chikusetsusaponins.

2.2. Anti-inflammatory activity

Inflammation is a well-orchestrated biological reaction that consists of multiple reactions. After the germ-line encoded receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and leucine-rich-repeat-containing receptors (NLRs), recognized external stimuli receptors detect pathogen- or damage-associated molecular patterns. Receptors are activated to stimulate a series of signaling cascades. Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) are very important pathway of inflammation. These transcriptional factors induce the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS, and COX-2. Consequently, cytokines can lead highly reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitrogen species in effector cells (Kim, Yi, Kim, & Cho, 2017, Tasneem et al., 2018). Both inhibiting cytokines and ROS or improving the expression of eNOS and SOD can alleviate inflammation.

Chikusetsusaponins from P. japonicus can inhibit inflammation in different cells with different inducer through inhibiting cytokines and ROS generation. By using colonic aging rats model, Dun et al. investigated the modulating intestinal tight junction of total saponins of P. japonicus (SPJ). The study proved that SPJ increased the expression of the tight junction proteins claudin-1 and occludin. Treatment with SPJ decreased the levels of interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), reduced the phosphorylation of three MAPK isoforms, and inhibited the expression of NF-κB. Consequently, SPJ modulates the damage of intestinal epithelial tight junction and inhibits inflammation in colonic aging rats model (Dun et al., 2018).

Chikusetsusaponin IVa (CSIVa) could significantly inhibit HFD-induced lipid homeostasis, and inhibited inflammation in adipose tissue through inhibiting both NLRP3 inflammasome activation and NF-κB signaling (Yuan et al., 2017). Meanwhile, Chikusetsusaponin IVa (CSIVa) suppresses the production of iNOS, COX-2, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells through inhibiting NF-κB activation and ERK, JNK, and p38 signal pathway phosphorylation (Wang, Qi, Li, Wu, & Wang, 2015). In addition, Chikusetsusaponin IVa methyl ester might inhibit iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β expression through downregulation of NF-κB and AP-1 in macrophages (Lee et al., 2016). Moreover, Chikusetsusaponin IV showed significant anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticoagulant effects through significantly inhibit levels of TXA2, ET, MDA, and COX-2 and improve the activities of eNOS and SOD in vitro (Cao et al., 2017). Moreover, Hsiu-Hui Chan (Chan et al., 2011) reported some chikusetsusaponins (including chikusetsusaponin IVa) exhibited strong inhibition of superoxide anion generation and elastase release by human neutrophils induced by formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl-lphenylalanine/cytochalasin B (fMLP/CB), with IC50 values ranging from 0.78 to 43.6 μmol/L (Table 2).

Table 2.

Anti-inflammatary activities of chikusetsusaponins.

| No. | Components | Experimental models | Doses | Results | Target molecules | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Total saponins | Colon of aging rats (18 mo old, Male Sprague-Dawley rats) | 10 mg/kg, 30 mg/kg, 60 mg/kg, oral daily for 6 months | Modulates the damage of intestinal epithelial tight junction in aging rats, inhibits inflammation | (↑) Claudin-1, occludin, interleukin-1b, (↓) tumor necrosis factor-a (TNF-α), (↓)the phosphorylation of the MAPK and NF-kB signaling pathways; | (Dun et al., 2018) |

| 2 | Chikusetsu saponin IVa | Male C57BL/6 mice, HFD-induced inflammation; mouse bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs); THP-1 from human | Animal:50 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg for 16 weeks; Cell: 0–40 μmol/L | Inhibited HFD-induced lipid homeostasis and inflammation in adipose tissue; inhibited the accumulation of adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs) and shifted their polarization from M1 to M2l | (↓) NLRP3 inflammasome component genes, (↓) IL-1β, Caspase-1 in mice; (↓) activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in BMDMs; (↓) TNFα, IL-1β, HFD-induced NF-κB signaling in vivo and LPS-induced NF-κB activation | (Yuan et al., 2017) |

| 3 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa | LPS-stimulated THP-1 human monocyte-like cells | 0–200 μg/mL | Inhibited inflammation (50–200 μg/mL) | (↓) iNOS, COX-2, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, (↓) NF-κB activation, ERK, JNK, and p38 signal pathway phosphorylation | (Wang, Qi, Li, Wu, & Wang, 2015) |

| 4 | Chikusetsu saponin IVa methyl ester | LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages for 24 h | 0–30 μmol/L | Inhibited inflammation inhibited NO and PGE 2 production | (↓) iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, (↓) NF-κB, AP-1 | (Lee et al., 2016) |

| 5 | Chikusetsusaponin IV | Thrombin-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury model | 200 μmol/L | Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticoagulant | (↓) TXA2, ET, MDA, and COX-2, (↑) eNOS and SOD in vitro. | (Cao et al., 2017) |

| 6 | taibaienoside I chikusetsusaponin-IVa, Ib, chikusetsusaponin IVa butyl ester, stipuleanoside R2, pseudoginsenoside RT1 methyl ester, oleanolic acid | Human neutrophils treated by formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl-Lphenylalanine/ cytochalasin B (fMLP/CB) | 0.78 to 43.6 μmol/L | Inhibition of superoxide anion generation and elastase release, with IC50 values ranging from 0.78 to 43.6 μmol/L | No report | (Chan et al., 2011) |

2.3. Cardiovascular protective activity

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality and includes various diseases such as cardiac ischemia, vascular disease, heart failure, atherosclerosis and hypertension (Lim, Ko, & Kim, 2013).

Cardiac dysfunction caused by ischemia and reperfusion has been ameliorated through the glucocorticoid receptor- and estrogen receptor-activated pathways and the eNOS-dependent mechanism (Kim et al., 2018, Kim, 2018). Also, saponins of P. japonicus (SPJ) exhibited beneficially cardioprotective effects on myocardial ischemia injury (MI) rats, mainly scavenging oxidative stress-triggered overgeneration and accumulation of ROS, alleviating myocardial ischemia injury and cardiac cell death. Moreover, the mechanism was concerned with markedly upregulated mRNA expressions of the SOD1, SOD2 and SOD3, and downregulated Bax and Caspase-3 mRNA and Bcl-2 mRNA expression and ratios of Bcl-2 to Bax (He et al., 2012). In addition, SPJ can inhibit NF-κB, ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK activation, but enhance the expression of SIRT1, alleviate MI injury and cardiac cell death. SPJ might significantly improve cardiac function through decreasing the serum MCP-1, TNF-α levels and Bax protein expression and increasing Bcl-2 protein expression. In addition, SPJ suppressed the protein expressions of NF-κBp65 subunit, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and p38 MAPK and increased the expression of SIRT1 in a dose-dependent manner, but did not show effect on c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (Wei et al., 2014). Moreover, Duan et al. reported Chikusetsu saponin IVa (CHIVa) can markedly reverse treatment of H9c2 cells induced by high glucose (HG) for 24 h, resulted in cell viability losing and ROS, LDH and Ca2+ levels improvement. A further study exhibits protective effect of CHS against hyperglycemia-induced myocardial injury (MI) through SIRT1/ERK1/2 and Homer1a pathway in vivo and in vitro (Duan et al., 2015).

Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) proliferation is the most important risk of atherosclerosis and hypertension (Kim et al., 2019). Liu et al. found chikusetsusaponin IVa methyl ester (3 μmol/L) exhibited a dose-dependent inhibitive effect on angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced VSMC proliferation (Liu et al., 2016). Chikusetsusaponin IVa can prevent hyperglycemia-induced myocardial injuries.

Many researchers have shown that inflammation of blood vessels can result in atherosclerosis and coronary artery dysfunction. Inflammation is widely acknowledged to increase morbidity and mortality in myocardial infarction (MI), and the ideal therapeutic methods should be aimed at the inflammation reaction triggers (Libby, 2005). Ginsenoside plays an important role in the treatment of chronic heart failure. With the Chinese medicine compound Yiqi Fumai Injection containing ginseng, it can be remarkable to improve the cardiac function of mice with chronic heart failure and the activity of inflammatory mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6, and interleukin-1β. In this formula, ginsenoside Ro (chikusetsusaponin V) is proved as an anti-inflammatory component and a new nuclear transcription factor NF-KB inhibition agent (Xing et al., 2013).

Activation of autophagy can effectively inhibit angiotensin II-induced inflammation and cardiac fibrosis (Qi, Li, Li, Li, & Du, 2014). Chikusetsusaponin IV a effectively attenuated myocardial fibrosis induced by isoprenaline in vivo, reduced the heart index, inhibited inflammatory infiltration, decreased collagen deposition and myocardial cell size. In addition, Chikusetsusaponin Ⅳa treatment activate the expression of autophagy-related markers through the activation of AMPK, which in turn inhibited the phosphorylation of mTOR and ULK1(Ser757), rather than directly phosphorylate ULK1(Ser555) by AMPK (Wang et al., 2018) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cardiovascular protective activity.

| No. | Components | Experimental models | Doses | Results | Target molecules | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Total saponins | Myocardial ischemia injury rats [Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–220 g) | 50 mg/kg/day, 100 mg/kg/day, orally, for 7 d | Scavenging oxidative stress-triggered overgeneration and accumulation of ROS, alleviating myocardial ischemia injury and cardiac cell death | (↑) mRNA expressions of the SOD1, SOD2 and SOD3, (↓) Bax and caspase-3 mRNA expressions, (↑) Bcl-2 mRNA, (↑) ratios of Bcl-2 to Bax | (He et al., 2012) |

| 2 | Total saponins | MI rats (Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 230 ± 20 g) | 50 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg for 7 d | Significantly improve cardiac function, alleviating MI injury and cardiac cell death | (↓) MCP-1, TNF-α, (↓) Bax, (↑) Bcl-2, (↑) SIRT1, (↓) NF-κBp65 subunit, ERK1/2, p38 MAPK activation | (Wei et al., 2014) |

| 3 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa | H9c2 cells with hyperglycemia-induced myocardial injuries(male C57BL/6 mice by intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin at a dose of 50 mg/kg dissolved in 100 mM citrate buffer pH 4.5 for five consecutive day) | 12.5, 25 and 50 μmol/L for 24 h | Against hyperglycemia-induced myocardial injuries. (↓)ROS, LDH and Ca2+ levels, protected myocardium from I/R-introduced apoptosis | SIRT1/ERK1/2 and Homer1a pathway in vivo and in vitro | (Duan et al., 2015) |

| 4 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa methyl ester | Angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced VSMC proliferation | 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, and 30 μmol/L for 24 h | Inhibitive effect on angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced VSMC proliferation, a dose-dependent inhibitive effect | 108.4, 103.2, 99.0, 94.2, 92.2, 72.1 μg/mL | (Liu et al., 2016) |

| 5 | Ginsenoside Ro | Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 230–250 g (CHF model induced by the occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery); Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK 293) cells, Rat cardiac microvascular endothelial cells (CMECs) | 100 mg/(kg/d), for eight weeks. | YQFM exerted cardioprotective effects in the context of CHF. YQFM could suppress the expressions of inflammatory mediators | Inhibitory effect on TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation in HEK 293 cells | (Xing et al., 2013) |

| 6 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa | Balb/C mice (Continuous subcutaneous injection of isoproterenol for 21 days was used to induce myocardial fibrosis in mice) | 5 mg/kg, 15 mg/kg for 20 d | Effectively attenuated isoprenaline-induced myocardial fibrosis in vivo, reduced the heart index, inhibited inflammatory infiltration, decreased collagen deposition and myocardial cell size | Activated autophagy through AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathway | (Wang et al., 2018) |

2.4. Neuroprotective activity

Studies have shown that saponins from Panax species possess neuroprotective effects (Kim et al., 2018ab, Kim et al., 2018ab). Liu et al. (2016) tested 17 compounds for neuroprotective activity to hydrogen peroxide-induced PC 12 cell injury by using the MTT assay. Three compounds exhibited moderate protective effects compared with a positive control. Chikusetsusaponins V, Ib, IV, IVa, and IVa ethyl ester were assessed for anti-Alzheimer disease activity using the PC12 cell model treated with Aβ(25-35), the cell viability of the extract group (100 μg/mL) was 65.12%, and those of chikusetsusaponins V, Ib, IV, IVa and IVa ethyl ester (100 μg/mL) groups were 68.36, 71.56, 69.55, 74.69 and 76.03%, respectively. These compounds increased the growth of PC12 cell (Li, Liu, Liu, & Zhang, 2017).

SH-SY5Y cells are human neuroblastoma cells, which possess many characteristics of dopaminergic neurons and have been widely used in the study of cell model for PD. Chikusetsusaponin V (CSV) mediated neuroprotective effects, including attenuation of MPP+-induced cytotoxicity, inhibition of ROS accumulation, exposure and increasing mitochondrial membrane potential dose-dependently in SH-SY5Y cells through Sirt1/Mn-SOD and GR78/Caspase-12 pathways (Yuan, Wan, Deng, Zhang, Dun, & Dai, 2014). Meanwhile, it can also attenuate H2O2-induced cytotoxicity, inhibit ROS accumulation, increase the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and GSH, and increase mitochondrial membrane potential dose-dependently in SH-SY5Y cells. In addition, CSV can downregulate expression of Bcl-2 and upregulate expression of Bax in a dose-dependent manner. Neuroprotective effects of chikusetsusaponin V are mainly concerned with Sirt1/PGC-1α/Mn-SOD signaling pathways (Wan et al., 2016).

Chikusetsusaponin IVa (CSIVa) exhibited neuroprotective effect on rats after their neonatal exposure to isoflurane by Morris Water Maze (MWM) test. It can improve adolescent spatial memory, ameliorate isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity and cognitive impairment, which might be associated with up-regulation of SIRT1/ERK1/2 (Fang, Han, Li, Zhao, & Luo, 2017).

However, Zou et al. reported protopanaxadiol-type saponins increased the neurite outgrowth in SK-N-SH cells, but not protopanaxatriol-type, ocotillol-type, and oleanolic acid saponins. These saponins are isolated from Ye-Sanchi (Panax japonicus C. A. Meyer (Araliaceae)) and the data of oleanolic acid saponins activity didn’t show (Zou, Zhu, Tohda, Cai, & Komatsu, 2002). Above all, some oleanolic acid saponins of P. japonicus showed neuroprotective effects in hydrogen peroxide or Aβ(25-35) induced PC 12 cell injury, neonatal rats exposure to isoflurane and MPP+-induced SH-SY5Y cells, but does not take effects in improving the proliferation of SK-N-SH cells (Table 4).

Table 4.

Neuroprotective activity of chikusetsusaponins.

| No. | Components | Experimental models | Doses | Results | Target molecules | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baisanqisaponins C, β-D-glucopyranosiduronic acid, taibaienoside I, 2-O-β-D- glucopyranosyl-6-butyl ester | Hydrogen peroxide-induced PC 12 cell injury | 3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, and 50 μg/mL | Exhibited moderate protective effects | No report | (Liu et al., 2016) |

| 2 | Chikusetsusaponins V (a), chikusetsusaponins Ib (b), chikusetsusaponins IV (c), chikusetsusaponins IVa (d), and chikusetsusaponins IVa ethyl ester (e), extracts of Panax japonicus leaf (f) | PC12 cell model treated with Aβ (25–35) | 100 μg/mL for 48 h | IInhibition rate: 68.36 (a), 71.56 (b), 69.55 (c), 74.69 (d), 76.03% (e), 65.12% (f) | No report | (Li et al., 2017) |

| 3 | Chikusetsu saponin V | MPP-induced SH-SY5Y cells | 0.1, 1, 10, 50 μmol/L for 24 h | Inhibits ROS accumulation, and increases mitochondrial membrane potential dose-dependently, down-regulating apoptosis | (↓) Bcl-2, (↑) Bax, (↑) Bcl-2/Bax, Sirt 1/Mn-SOD and GRP78/ Caspase-12 pathways | (Yuan et al., 2014) |

| 4 | Chikusetsu saponin V | H2O2-induced SH-SY5Y cells | 10 μmol/L | Attenuated H2O2-induced cytotoxicity, inhibited ROS accumulation, (↑) superoxide dismutase (SOD) and GSH and increased mitochondrial membrane potential dose-dependently. | (↓) Bcl-2, (↑) Bax, (↑) ratio of Bcl-2/Bax, Sirt1/PGC-1α/Mn-SOD signaling pathways | (Wan et al., 2016) |

| 5 | Chikusetsu saponin IVa | Neonatal rats exposure to isoflurane by Morris Water Maze (MWM) test | 30 mg/kg (100 μL) | Improved adolescent spatial memory, ameliorate isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity and cognitive impairment. | (↑) SIRT1, p-ERK1/2, PSD95, (↓) hippocampal neuron apoptosis and (LDH) release | (Fang et al., 2017) |

| 6 | Ginsenosides Rb1, Rb3, notoginsenosides R4, Fa | SK-N-SH cells | 100 μmol/L | Significant neurite outgrowth enhancing activities in human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells. | No report | (Zou, Zhu, Tohda, Cai, & Komatsu, 2002) |

2.5. Effect on metabolic system

Oleanolic acid glycosides from several medicinal foodstuffs were found to show potent inhibitory activity on the increase of serum glucose levels in oral glucose-loaded rats (Xi et al., 2010). Six chikusetsusaponins (notoginsenoside R1, ginsenoside Rb1, chikusetsusaponin V, chikusetsusaponin IV, chikusetsusaponin IVa and ginsenoside Rd) were screened to be potential α-glucosidase inhibitors by a new assay based on ultrafiltration, liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (Li, Tang, Liu, & Zhang, 2015). Ethanolic extract, n-BuOH (PJB) and H2O (PJW) extract, compound oleanolic acid 28-O-β-D-glucopyranoside are reported to be potential inhibition of R-glucosidase activity compared with acarbose (Chan et al., 2011, Chan, Sun, Reddy, & Wu, 2010).

Chikusetsusaponin IVa (CSIVa) of oral administration increased the level of serum insulin and decreased the rise in blood glucose level with a dose-dependently manner in type 2 diabetic mellitus (T2DM) rats. In vitro, CSIVa potently activated βTC3 cells releasing insulin at both basal and stimulatory glucose concentrations and the effect was changed by the removal of extracellular Ca2+. The signaling of CSIVa-induced insulin secretion from βTC3 cells resulted from GPR40 mediated calcium and PKC pathways (Cui et al., 2015). Moreover, Chikusetsusaponin IVa (CSIVa) effectively decreases blood glucose, triglyceride, free fatty acid (FFA) and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels in T2DM rats. In both normal and insulin-resistant C2C12 myocytes, CSIVa increases glucose uptake or fatty acid oxidation through activating AMPK and enhancing membrane translocation of GLUT4 or CPT-1 activity respectively. In addition, the effects of CSIVa on glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation significantly diminishes by the knockdown of AMPK. Thus, CSIVa is a novel AMPK activator that is capable of by passing defective insulin signaling and might be developed into a new potential for therapeutic agent used in T2DM patients or other metabolic disorders (Li et al., 2015).

Chikusetsusaponins not only relieve disorder of glucose metabolism, but also ameliorate abnormal fat metabolism. Obesity is closely associated with life-style-related diseases. Total chikusetsusaponins, chikusetsusaponin III, 28-deglucosyl-chikusetsu-saponin IV and 28-deglucosyl-chikusetsusaponin V prevent obesity induced in mice by a high-fat diet for 9 weeks. It increased the fecal content and triacylglycerol level and inhibited the elevation of the plasma triacylglycerol level 2 h after oral lipid emulsion treatment. The anti-obesity effects of chikusetsusaponins may be partly mediated through delaying the intestinal absorption of dietary fat by inhibiting pancreatic lipase activity (Han, Zheng, Yoshikawa, Okuda, & Kimura, 2005).

Chikusetsusaponin IVa pretreatment attenuate cerebral ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury in diabetic mice. It increased APN level and enhanced neuronal AdipoR1, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK-3β) expression in a concentration-dependent manner. Consequently, chikusetsusaponin IVa reduced infarct size, improved neurological outcomes, and inhibited cell injury after I/R (Duan et al., 2016) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effect on metabolic disease.

| No. | Components | Experimental models | Doses | Results | Molecular mechanisms or pathways | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Notoginsenoside R1, Rb1, Rd, chikusetsusaponin V, IV, IVa | Inhibition assay of α-glucosidase | IC50 = 2.19, 1.87, 1.65, 5.16, 4.04, 3.23 mg/mL (R1, Rb1, Rd, V, IV, IVa) | Potential α-glucosidase inhibitors compared with acarbose | No report | (Li et al., 2015) |

| 2 | Ethanolic extract, the n-BuOH (PJB) and H2O (PJW) extracts | α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Assay | Acarbose, IC50 = 5.43 mg/mL PJB, IC50 > 11.75 mg/mL PJW, IC50 > 11.76 mg/mL. | Moderate inhibition of R-glucosidase activity | No report | (Chan, Sun, Reddy, & Wu, 2010) |

| 3 | Oleanolic acid 28-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (a), oleanolic acid (b) | α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Assay | aIC50 values = 75.0; bIC50 values = 50.4 μmol/L, Acarbose, IC50 = 678 μmol/L | Potent inhibition of R-glucosidase activity | No report | (Chan et al., 2011) |

| 4 | Chikusetsu saponin IVa | Type 2 diabetic mellitus (T2DM) rats | Oral administration, 45 mg/kg, 90 mg/kg, 180 mg/kg for 28 d | Increase the level of serum insulin and decreased the rise in blood glucose level in an in vivo treatment | (↑) Intracellular calcium levels in βTC3 cells, the phosphorylation of PKC; GPR40 mediated calcium and PKC pathway | (Cui et al., 2015) |

| 5 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa | Rats with streptozotocin/nicotinamide-induced T2DM and insulin-resistant myocytes | 7.5, 15 and 30 mg/kg intragastrical for 4 weeks | Decreases blood glucose, triglyceride, free fatty acid (FFA) and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels | In both normal and insulin-resistant C2C12 myocytes: (↑) AMPK, (↑) glucose uptake or fatty acid oxidation, (↑) membrane trans-location of GLUT4 or CPT-1 activity | (Li et al., 2015) |

| 6 | Total chikusetsusaponins | Mice fed a high-fat diet | 1000 mg/kg, orally, for 9 weeks; Chikusetsusaponin III and 28-deglucosylchikusetsusaponins IV and V inhibited the pancreatic lipase activity at 125–500 µg/mL | (↓) The increases in body weight and parametrial adipose tissue weight; (↑) fecal triacylglycerol content and level; (↓) the plasma triacylglycerol level | Delaying the intestinal absorption of dietary fat by inhibiting pancreatic lipase activity | (Han, Zheng, Yoshikawa, Okuda, & Kimura, 2005) |

| 7 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa | Type 2 Diabetic + I/R mouse model | 30, 60, and 120 mg/kg for 1 month | (↓) Infarct size, improved neurological outcomes, (↓) cell injury after I/R | (↓) TNF-α, MDA, caspase-3, Bax/ Bcl-2 ratio; (↑) AdipoR1, AMPK, GSK-3β;(↑) glycogen synthase kinase 3 AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of GSK-3β downstream of APN-LKB1 pathway. | (Duan et al., 2016) |

2.6. Effect on hematological system

It is reported P. japonicus var. major and P. japonicus var. bipinnatifidus could be used as a substitute for P. notoginseng as hemostatic herbs (Yang et al., 2018). P. notoginseng is used for treating bleed in bone injury. Meanwhile, the traditional use of P. japonicus is similar with P. notoginseng in folk.

Chikusetsusaponin III, IV and V showed a strong promotion of uroenzyme fibrin plate (Matsuda et al., 1989). Min Li reported some chikusetsusaponins exhibited moderate antiplatelet aggregation activities induced by adenosine diphosphate with IC50 values of less than 25 µmol/L, respectively (Li et al., 2017).

Chikusetsusaponin IVa prolongs the recalcification time, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and thrombin time of normal human plasma in a dose-dependent manner, inhibits the amidolytic activity of thrombin and factor Xa upon synthetic substrates S2238 and S2222. In addition, it preferentially inhibits thrombin in a competitive manner (Ki = 219.6 L mol/L). Furthermore, it inhibited thrombus formation in a stasis model of venous thrombosis and prolonged the ex vivo activated partial thromboplastin time (Dahmer et al., 2012).

Hong Zhang reported polysaccharides (PJPS) and low-molecular-weight compounds (PJSM) accelerate the recovery of the white blood cell (WBC), red blood cell (RBC), and haemoglobin (HGB) levels in the blood deficiency model mice. Haematopoietic activity may result from stimulating the secretion of interleukin-3 (IL-3), interleukin-6 (IL-6), erythropoietin (EPO), GM colony stimulating factor (CSF), and M-CSF and from the resistance of spleen cells to apoptosis (Zhang et al., 2015) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Effect on hematological system.

| NO. | Components | Experimental models | Doses | Results | Molecular mechanisms or pathways | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70% Methanol extract | Endotoxin-induced DIC rats, thrombin-induced DIC rats, normal rats | 50, 200, 500 mg/kg | DIC rats: no preventive effect against DIC; showed a promotive effect on the activation of the fibrinolytic system; chikusetsusaponin III, IV, and V showed promotional effect of fibrinolytic system | Promotional effect on urokinase action for plasminogen | (Matsuda et al., 1989) |

| 2 | (20S)-6′-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-β-D-glucopyranosyl-dammar-20,25-epoxy −3β,6α,12β,24α-tetraol (a) 6-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl(1 → 2)-β-D-glucopyranosyl-dammar-25(26)-ene-3β,6α,12β,20S,24R-pentaol (b) |

Induced by adenosine diphosphate; Arachidonic acid induced |

aIC50 = 23.24 μmol/L (adenosine diphosphate), bIC50 = 18.43 μmol/L (arachidonic acid); bIC50 = 30.11 μmol/L (arachidonic acid) |

Exhibited moderate antiplatelet aggregation activities | No report | (Li et al., 2017) |

| 3 | Polysaccharides (PJPS); low-molecular-weight compounds (PJSM) | Anaemia model mice that were given hypodermic injections of N-acetyl phenylhydrazine (APH) and intraperitoneal injections of cyclophosphamide (CTX) | 150 mg/kg (low) 75 mg/kg (high) |

Accelerate the recovery of the white blood cell (WBC), red blood cell (RBC) and haemoglobin (HGB) levels in the blood deficiency model mice | (↑) IL-3, IL-6, erythropoietin (EPO), GM colony-stimulating factor (CSF), and M−CSF; (↓) spleen cells to apoptosis |

(Zhang et al., 2014) |

| 4 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa |

In vitro: normal human plasma; In vivo: deep venous thrombosis model, Male Wistar rats induced by a tissue factor-rich component with minor modifications |

In vitro, 500 μmol/L, 1000 μmol/L; in vivo 15 and 50 mg/kg |

In vitro: (↑) Time of recalcification, prothrombin, activated partial thromboplastin, thrombin; (↓) amidolytic activity of thrombin and factor Xa upon S2238 and S2222; (↓) thrombin-induced fibrinogen clotting (50% inhibition concentration, 199.4 ± 9.1 μmol/L), (↓) platelet aggregation (thrombin- and collagen-induced). In vivo: (↓) thrombus formation, did not induce a significant bleeding effect |

Increase in fibrinolysis | (Dahmer et al., 2012) |

2.7. Hepatocyte protective activity

Ginsenoside Ro (chikusetsusaponin V) inhibited the increase of connective tissue in the liver of CCl4-induced chronic hepatitic rats (Matsuda, Samukawa, & Kubo, 1991). Moreover, Li (Li et al., 2010) investigated the possible mechanism(s) of saponins from P. japonicus (SPJ) on alcohol-induced hepatic damage in mice. In vitro, SPJ showed significant hydroxyl radical scavenging capacity. In vivo, SPJ (50 mg/kg) could rectify the pathological changes of aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, malondialdehyde, meanwhile, the levels of glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) caused by alcohol metabolism are reduced to normal levels but not that of hepatic GSH and CAT. RT-PCR results proved that total saponins of P. japonicus (SPJ) protect the structure and function of hepatic mitochondria and karyon by directly scavenging reactive oxygen species/free radicals and up-regulating the expression of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, GPX and CAT), especially to GPX3, SOD1 and SOD3.

Fatty liver fibrosis, a severe form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is a key step which can be reversed by effective medical intervention. Saponins of P. japonicus (SPJ) could significantly improve liver function and decrease the lipid level in the serum. SPJ significantly improved the liver steatosis, collagen fibers and inflammatory cell infiltration. In addition, SPJ distinctly attenuate the collagen I (Coll), alpha smooth muscle actin (alpha-SMA), tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMP), CHOP and GRP78 mRNA expression levels; Moreover, the phosphorylated JNK (p-JNK), Coll and 78 kD glucose-regulated protein (GRP78) expression levels were significantly alleviated, which might be caused by the inhibition of the ERS response and the CHOP and JNK-mediated apoptosis and inflammation pathway (Yuan et al., 2018).

Chikusetsusaponin V, the most abundant saponin in P. japonicus, has reported to inhibit inflammation. Also, Dai reported it attenuated elevation of alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels and improved liver histopathological changes in LPS-induced mice. Chikusetsusaponin V decreased serum TNF-α and IL-1β levels and inhibited mRNA expressions of in iNOS, TNF-a and IL-1β. Furthermore, chikusetsusaponin V inhibited NF-κB activation via downregulating phosphorylated NF-κB, IκB-α, ERK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 levels, which ultimately decreased nucleus NF-κB protein level. These data suggested that chikusetsusaponin V could be a promising drug for preventing LPS challenged liver injury through NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways (Dai et al., 2016) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Hepatocyte protective activity.

| No. | Components | Experimental models | Doses | Results | Molecular mechanisms or pathways | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ginsenoside Ro | ANIT-induced, o-galactosamine (GaiN)- and CCl4-induced hepatitic rats | 50 and 200 mg/kg, p.o for 6 weeks | Increase fibrosis around Glisson's sheath; inhibited the increase of connective tissue |

(↑) Hydroxyproline content (↓) the increase of serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (s-GOT) and serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (s-GPT) levels |

(Matsuda et al., 1991) |

| 2 | Total saponins | Male ICR mice (25 ± 2 g), Alcohol-Induced Hepatic injury | 12.5, 25 and 50 mg/kg b.w. for 30 d | Protect the structure and function of hepatic mitochondria and karyon; rectify the pathological changes of aspartate transaminase, malondialdehyde, alanine transaminase; | (↑) Antioxidant enzymes (SOD, GPX and CAT), especially to GPX3, SOD1 and SOD3; scavenging reactive oxygen species/free radicals |

(Li et al., 2010) |

| 3 | Total saponins | fatty liver fibrosis model | 100 mg/kg, 300 mg/kg, once two days for 11 weeks | Significantly improve liver function and decrease the lipid level in the serum Improve liver steatosis, collagen fibers and inflammatory cell infiltration |

(↓) Collagen I (Coll), α smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMP), CHOP and GRP78 mRNA, phosphorylated JNK (p-JNK), Coll and 78 kD glucose-regulated protein (GRP78) protein; Inhibit ERS response and the CHOP and JNK-mediated apoptosis and inflammation pathway. |

(Yuan et al., 2018) |

| 4 | Chikusetsusaponin V | LPS-induced liver injury model | 5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg for 4 d | Attenuated elevation of alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels and improved liver histopathological changes | (↓) (iNOS), TNF-α, IL-1β, phosphorylated NF-κB, IκB-α, ERK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 levels; NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways |

(Dai et al., 2016) |

2.8. Other activities

Ginsenoside Ro showed inhibitory activity against 5αR with IC50 values of 259.4 µmol/L. The rhizome of P. japonicus, which contains larger amounts of ginsenoside Ro, also inhibited 5αR. Topical administration of extracts of red ginseng rhizomes and ginsenoside Ro (0.2 mg/kg) to shave skin inhibited hair re-growth suppression after shaving in the testosterone-treated C57BL/6 mice (Murata, Takeshita, Samukawa, Tani, & Matsuda, 2012).

Methanol extracts from the roots of P. japonicus can suppress Fas-mediated apoptotic cell death of HaCaT cells (a human keratinocyte cell line) and Pam 212 cells (a murine keratinocyte cell line). Chikusetsusaponin IV was the most active compound (12.5 mg/mL) among chikusetsusaponins IV, IVa, V, polysciasaponin P5, which intends to that chikusetsusaponin IV reduced the intracellular hallmark events of apoptosis such as DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation. It also inhibited the apoptotic cell death of Jurkat cells. These results suggest that the use of chikusetsusaponins IV, IVa, V, polysciasaponin P5 is expected to relieve cutaneous symptoms caused by excessive apoptotic cell death in the skin via the Fas/FasL pathway (Hosono-Nishiyama et al., 2006). These results suggest that P. japonicus are a promising raw material for cosmetic use.

Chikusetsusaponin IVa showed antiviral activities against HSV-1, HSV-2, human cytomegalovirus, measles virus, and mumps virus with selectivity indices (CC (50)/IC (50)) of 29, 30, 73, 25 and 25, respectively. Chikusetsusaponin IVa also provided in vivo efficacy in a mouse model of genital herpes caused by HSV-2. These results demonstrate that chikusetsusaponin IVa might be a candidate of antiherpetic agents (Rattanathongkom et al., 2009) (Table 8).

Table 8.

Other activities.

| No. | Components | Experimental models | Doses | Results | Molecular mechanisms or pathways | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ginsenoside Ro | Shaving in the testosterone-treated C57BL/6 mice | IC50 = 259.4 μmol/L 0.2 mg/kg |

Enhances in vivo hair re-growth | Against 5αR | (Murata, Takeshita, Samukawa, Tani, & Matsuda, 2012) |

| 2 | Chikusetsusaponin IV | HaCaT cells (human) Pam 212 cells (murine) |

12.5 mg/mL | Reduce apoptosis of DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation | Excessive apoptotic cell death in the skin through the Fas/FasL pathway | (Hosono-Nishiyama et al., 2006) |

| 3 | Chikusetsusaponin IVa | HSV-1, HSV-2, human cytomegalovirus, measles virus, and mumps virus | (CC (50)/IC (50)) of 29, 30, 73, 25, and 25 | Antiviral activities | No report | (Rattanathongkom et al., 2009) |

3. Commercial formulation in clinical trial

There are some commercial formulations in clinical trial. More and more clinical trial are being conducted recently, and metabolomics are used not only in plant but also the formulation (Xie et al., 2008, Yu, Mwesige, Yi, & Yoo, 2019).

ShenMai Injection (SMI), is an intravenous injection used as an add-on therapy for coronary artery disease and cancer; saponins are its bioactive constituents. Ginsenosides Rb, Rb, Rc, Rd, Ro, Ra, Re, and Rg likely contribute the major part of OATP1B3-mediated ShenMai-drug interaction potential. Ginsenoside Ro (chikusetsusaponin V) inhibited OATP1B3 more potently than the other ginsenosides detected in ShenMai plasma (Olaleye et al., 2019). Another research showed 14 saponins of 21 compounds were quantified in SMI by HPLC–MS. The highest content of ginsenosides Ro and chikusetsusaponin IVa are137 μg/mL, 4.96 μg/mL in ten batches, respectively, indicating these compounds may play an important role in pharmacodynamics of SMI (Li, Cheng, Dong, Li, & Yang, 2016).

The fermented Chinese formula Shuan-Tong-Ling (STL) is composed of Puerariae Lobatae Radix (Gegen in Chinese), Salvia miltiorrhiza (Danshen in Chinese), Curcumae Radix (Jianghuang in Chinese), Hawthorn (Shanzha in Chinese), Salvia chinensis (Shijianchuan in Chinese), Sinapis alba (Baijiezi in Chinese), Astragali Radix (Huangqi in Chinese), Panax japonicus (Zhujieshen in Chinese), Atractylodes macrocephala (Baizhu in Chinese), Paeoniae Radix Alba (Baishao in Chinese), Bupleurum chinense (Chaihu in Chinese), Chrysanthemum indicum (Juhua in Chinese), Cyperi Rhizoma (Xiangfu in Chinese) and Gastrodiae Rhizoma (Tianma in Chinese). The aqueous extract was fermented with Lactobacillus, Bacillus aceticus and Saccharomycetes. ShuanTong-Ling is a formula used to treat brain diseases including ischemic stroke, migraine, and vascular dementia. Shuan-Tong-Ling attenuated H2O2-induced oxidative stress in rat microvascular endothelial cells. Meanwhile, Shuan-Tong-Ling also decreased tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1β levels in the hippocampus on the ischemic side. In addition, Shuan-Tong-Ling upregulated the expression of SIRT1 and Bcl-2 and downregulated the expression of acetylated-protein 53 and Bax. The reduced ROS level was accompanied by increasing SOD and GSH activities. Further assays showed upregulation of SIRT1 and PGC-1αand downregulation of p21 after STL treatment. The results revealed that STL could protect BMECs against oxidative stress injury at least partially through the SIRT1 pathway (Mei et al., 2017, Tan et al., 2016).

4. Predictive analysis on Q-marker

P. japonicus contains a complicated mix of bioactive constituents, including polysaccharides, organic acids, and saponins, such as oleanolic acid-type triterpenoid saponins and dammarane-type triterpenoid saponins. Polysaccharides and triterpenoids saponins are the main components of P. japonicus. Oleanane-type triterpenoid saponins from P. japonicus are called chikusetsusaponin in some literatures and these compounds are usually considered as the special chemical distinct from P. ginseng. So chikusetsusaponin can be Q-marker candidate of P. japonicus. Moreover, P. japonicus is a commonly used traditional Chinese medicine that was first developed in Supplemen to Materia Medica (Zhang et al., 2014). The commonly traditional of P. japonicus usage is tonifying “qi” to remove blood stasis, to promote hematopoietic effects and promote blood circulation and supporting healthy energy (Zhang et al., 2015). “Qi” is a Chinese term used as a broad description of energy-dependent body functions. In the realm of TCM, “qi” is regarded as the “root of life”; body functions are often expounded in terms of “qi” (Ko & Chiu, 2006). “Qi deficiency and blood stasis” is one of the primary pathogenesis characteristics of ischemic stroke (Wang et al., 2020). P. japonicus can protect heart and nervous vascular injury, which is based on tonifying “qi” and activating blood effects. “Qi stagnation and blood stasis” is a common clinical type, and its formation is related to diet, mood, environment and other factors. Metabolic disease and cancer is closely related to life-style. Balancing qi, xue, yin and yang, eliminating phlegm and removing dampness is how TCM compound functions on cancer patients (Wang, Long, & Wu, 2018). Chikusetsusaponin V, chikusetsusaponin IVa and chikusetsusaponin IV have been reported their apparent ability to replenish blood, prevent anti-tumor effects and anti-inflammation, and decrease the effects of myocardial ischemia (Yang et al., 2014). Furthermore, chikusetsusaponin can be qualified by HPLC and our group have established fingerprint chromatogram of P. japonicus from different places (Wu et al., 2019). In summary, triterpenoids can be the Q-marker of P. japonicus according to five basic principles of definition of quality markers (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Brief summary of pharmacological properties of P. japonicus on human healthy issues.

5. Conclusion

Ginsenosides are existed in many plants, and a compound library for pharmacology screening is necessary. P. ginseng is a very important adapted agent in traditional Chinese medicine. P. japonicus used as a substitute herbal medicine in minor ethnomedicine. Therefore, this article is trying to review the bioactivities and pharmacology of P. japonicus and present the possibility of P. japonicus as P. ginseng.

P. japonicus, P. ginseng and P. notoginseng are in the same family. There are some similarities in most of Panax species in the phylogenetic trees reconstructed by trnK-18S rRNA gene sequences (Nguyen et al., 2018). Because of the genetic connection, physiological and biochemical characteristics of them are similar. In result, P. japonicus resembles P. ginseng and P. notoginseng in chemical basis of dammarane-type and oleanane-type saponins. However, the quantity of saponins is a little different which is of concern (Zhu, Zou, Fushimi, Cai, & Komatsu, 2004). In addition, the total saponin content in the roots of P. japonicus can reach 15%, which is 2- to 7-fold higher than that of P. ginseng (Huang et al., 2015), which means that P. japonicus can serve more active components and economic values. Moreover, according to TCM theory, P. japonicus is sweet and slightly bitter in taste, warm in nature and has special tropism to the liver and stomach, which is analogous to P. ginseng and P. notoginseng (B. R. Yang et al., 2018). As to the effects of traditional Chinese medicines, “Ginseng lists first in tonifying qi, which is recorded in Supplement to “The Grand Compendium of Materia Medica”. P. japonicus was traditionally used as P. ginseng for enhancing immunity. In addition, it can be applicated as P. notoginseng for treating blood stasis in minor ethnomedicine (Zhang et al., 2015). In addition, the rhizomes of P. japonicus are used as a folk medicine for treatment of lifestyle related diseases such as arteriosclerosis, hyperlipidemia, hypertension and non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, and ginseng roots in China and Japan are also used as the remedy for life-style-related diseases (Han, Zheng, Yoshikawa, Okuda, & Kimura, 2005). Literatures reported that P. ginseng showed anti-cancer, protection of the cardiovascular system and nervous system, liver protection and other activities. This review summarized the anticancer activity, anti-inflammatory, cardiovascular protective, the nervous system protective and hepatocyte activities of P. japonicus. Some researchers compared the antioxidant, anti-cancer, anti-obesity and anti-inflammatory activities of P. japonicus and P. ginseng. P. japonicus showed similar activities with P. ginseng (Dai et al., 2015, Han, Zheng, Yoshikawa, Okuda, & Kimura, 2005, Liu et al., 2016, Zhang and Huang, 1989). However, there are further research to do in the comparison of P. japonicus and P. ginseng for proving the substitution possibility.

Chikusetsusaponins, as an important material basis of traditional Chinese medicines (such as P. ginseng, P. japonicus, Achyranthes bidentate), the research of them is still not deep enough. It is believed that with the mechanism of action and structure–activity relationship of Chikusetsusaponins, the application value of P. japonicus in medicine, beauty care and other aspects will be further developed.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No. 2017JJ5041, 2018JJ2293), the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2018YFC1707900), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81703819, 81874369, 81803708, 81673579 and 81374062), Key Research and Development Programs of Hunan Science and Technology Department (No. 2018SK2113, 2018SK2119, 2018WK2081).

References

- Ahuja A., Kim J.H., Kim J.H., Yi Y.S., Cho J.Y. Functional role of ginseng-derived compounds in cancer. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2018;42(3):248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Gu C., Zhao F., Tang Y., Cui X., Shi L., Yin L., et al. Therapeutic effects of Cyathula officinalis Kuan and its active fraction on acute blood stasis rat model and identification constituents by HPLC-QTOF/MS/MS. Pharmacognosy Magazine. 2017;13(52):693. doi: 10.4103/pm.pm_560_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H.H., Hwang T.L., Reddy M.V., Li D.T., Qian K., Bastow K.F., et al. Bioactive constituents from the roots of Panax japonicus var. major and development of a LC-MS/MS method for distinguishing between natural and artifactual compounds. Journal of Natural Products. 2011;74(4):796–802. doi: 10.1021/np100851s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H.H., Sun H.D., Reddy M.V., Wu T.S. Potent α-glucosidase inhibitors from the roots of Panax japonicus C A. Meyer var. major. Phytochemistry. 2010;71(11–12):1360–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Wu Q.S., Meng F.C., Tang Z.H., Chen X., Lin L.G., et al. Chikusetsusaponin IVa methyl ester induces G1 cell cycle arrest, triggers apoptosis and inhibits migration and invasion in ovarian cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 2016;23(13):1555–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Xi M.M., Li Y.W., Duan J.L., Wang L., Weng Y., et al. Insulinotropic effect of Chikusetsu saponin IVa in diabetic rats and pancreatic beta-cells. Journal of Ethnopharmacol. 2015;164:334–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahmer T., Berger M., Barlette A.G., Reck J., Jr., Segalin J., Verza S., et al. Antithrombotic effect of chikusetsusaponin IVa isolated from Ilex paraguariensis (Mate) Journal of Medicinal Food. 2012;15(12):1073–1080. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2011.0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y.W., Yuan D., Wang T. Research progress in inflammation signaling mediated by the pattern recognition receptors and anti-inflammatory of saponins from Panax species. Progress in Modern Biomedicine. 2015;15(1):163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y.W., Zhang C.C., Zhao H.X., Wan J.Z., Deng L.L., Zhou Z.Y., et al. Chikusetsusaponin V attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury in mice. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology. 2016;38(3):167–174. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2016.1153109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J., Yin Y., Cui J., Yan J., Zhu Y., Guan Y., et al. Chikusetsu saponin IVa ameliorates cerebral Ischemia reperfusion injury in diabetic mice via adiponectin-mediated AMPK/GSK-3beta pathway in vivo and in vitro. Molecular Neurobiology. 2016;53(1):728–743. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-9033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J., Yin Y., Wei G., Cui J., Zhang E., Guan Y., et al. Chikusetsu saponin IVa confers cardioprotection via SIRT1/ERK1/2 and Homer1a pathway. Scientific Reports. 2015;5(1) doi: 10.1038/srep18123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dun Y., Liu M., Chen J., Peng D., Zhao H., Zhou Z., et al. Regulatory effects of saponins from Panax japonicus on colonic epithelial tight junctions in aging rats. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2018;42(1):50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X., Han Q., Li S.Y., Zhao Y.L., Luo A.L. Chikusetsu saponin IVa attenuates isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity and cognitive deficits via SIRT1/ERK1/2 in developmental rats. American Journal of Translational Research. 2017;9(9):4288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L.K., Zheng Y.N., Yoshikawa M., Okuda H., Kimura Y. Anti-obesity effects of chikusetsusaponins isolated from Panax japonicus rhizomes. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2005;5(1) doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H., Xu J., Xu Y., Zhang C., Wang H., He Y., et al. Cardioprotective effects of saponins from Panax japonicus on acute myocardial ischemia against oxidative stress-triggered damage and cardiac cell death in rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;140(1):73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosono-Nishiyama K., Matsumoto T., Kiyohara H., Nishizawa A.i., Atsumi T., Yamada H. Suppression of fas-mediated apoptosis of keratinocyte cells by chikusetsusaponins isolated from the Roots of Panax japonicus. Planta Medica. 2006;72(3):193–198. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Lin J., Cheng Z., Xu M., Guo M., Huang X., et al. Production of oleanane-type sapogenin in transgenic rice via expression of beta-amyrin synthase gene from Panax japonicus C A. Mey. BMC Biotechnoloy. 2015;15:45. doi: 10.1186/s12896-015-0166-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal Y., Liang Z., Ho A., Chen H., Williams L., Zhao Z. Tissue-based metabolite profiling and qualitative comparison of two species of Achyranthes roots by use of UHPLC-QTOF MS and laser micro-dissection. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis. 2018;8(1):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z., Qian J., Dong H., Yang J., Yu X., Chen J., et al. The traditional Chinese medicine Achyranthes bidentata and our de novo conception of its metastatic chemoprevention: From phytochemistry to pharmacology. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02054-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.H. Pharmacological and medical applications of Panax ginseng and ginsenosides: A review for use in cardiovascular diseases. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2018;42(3):264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.M., Huh J.W., Kim E.Y., Shin M.K., Park J.E., Kim S.W., et al. Endothelial dysfunction induces atherosclerosis: Increased aggrecan expression promotes apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. BMB Reports. 2019;52(2):145–150. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2019.52.2.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-J., Jung S.-W., Kim S.-Y., Cho I.-H., Kim H.-C., Rhim H., Kim M., Nah S.-Y. Panax ginseng as an adjuvant treatment for Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2018;42(4):401–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Lee H.J., Kim D.J., Kim T.M., Moon H.S., Choi H. Panax ginseng exerts antiproliferative effects on rat hepatocarcinogenesis. Nutrition Research. 2013;33(9):753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.H., Lee D., Lee H.L., Kim C.E., Jung K., Kang K.S. Beneficial effects of Panax ginseng for the treatment and prevention of neurodegenerative diseases: Past findings and future directions. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2018;42(3):239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.H., Yi Y.S., Kim M.Y., Cho J.Y. Role of ginsenosides, the main active components of Panax ginseng, in inflammatory responses and diseases. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2017;41(4):435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko K.M., Chiu P.Y. Biochemical basis of the “Qi-Invigorating” Action of Schisandra Berry (Wu-Wei-Zi) in Chinese Medicine. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2006;34(02):171–176. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X06003734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.H., Kim J.H. A review on the medicinal potentials of ginseng and ginsenosides on cardiovascular diseases. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2014;38(3):161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Joon. l, Park Kyoung Sun, Cho Ik-Hyun. Panax ginseng: A candidate herbal medicine for autoimmune disease. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2019;43(3):342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.J., Shin J.S., Lee W.S., Shim H.Y., Park J.M., Jang D.S., et al. Chikusetsusaponin IVa methyl ester isolated from the roots of Achyranthes japonica suppresses LPS-induced iNOS, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β expression by NF-κB and AP-1 inactivation. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2016;39(5):657–664. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b15-00572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.M., Yun J.H., Lee D.H., Park Y.G., Son K.H., Nho C.W., et al. Chikusetsusaponin IVa methyl ester induces cell cycle arrest by the inhibition of nuclear translocation of beta-catenin in HCT116 cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2015;459(4):591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Cheng T.F, Dong X, Li P, Yang H. Global analysis of chemical constituents in Shengmai injection using high performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2016;117:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.G., Ji D.F., Zhong S., Shi L.G., Hu G.Y., Chen S. Saponins from Panax japonicus protect against alcohol-induced hepatic injury in mice by up-regulating the expression of GPX3, SOD1 and SOD3. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2010;45(4):320–331. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Liu F., Jin Y.R., Wang X.Z., Wu Q., Liu Y., et al. Five new triterpenoid saponins from the rhizomes of Panacis majoris and their antiplatelet aggregation activity. Planta Medica. 2017;83(3–04):351–357. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-117554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.N, Liu C.Y, Liu C.M, Zhang Y.C. Extraction and in vitro screening of potential acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from the leaves of Panax japonicus. Journal of Chromatography B. 2017;1061-1062:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Tang Y., Liu C., Zhang Y. Development of a method to screen and isolate potential alpha-glucosidase inhibitors from Panax japonicus C.A. Meyer by ultrafiltration, liquid chromatography, and counter-current chromatography. Journal of Separation Science. 2015;38(12):2014–2023. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201500064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.Q., Tian Y.Z., Qu S.Y., Lu Z.H., Tu H.H., Qin X.J., et al. Antioxidant and anti-aging effect of chikusetsu saponin Ⅳa, an active ingredient in Aralia taibaiensis. Central South Pharmacy. 2018;16(4):459–464. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.W., Zhang T.J., Cui J., Jia N., Wu Y., Xi M.M., et al. Chikusetsu saponin IVa regulates glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation: Implications in antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic effects: Effects of Chikusetsu saponin IVa on T2DM. Journal of Pharmacy Pharmacology. 2015;67(7):997–1007. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P. Act local, act global: Inflammation and the multiplicity of “vulnerable” coronary plaques. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2005;45(10):1600–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liby Karen T., Sporn Michael B., Esbenshade Timothy A. Synthetic oleanane triterpenoids: Multifunctional drugs with a broad range of applications for prevention and treatment of chronic disease. Pharmacol Reviews. 2012;64(4):972–1003. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.004846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K.H, Ko D, Kim J.H. Cardioprotective potential of Korean Red Ginseng extract on isoproterenol-induced cardiac injury in rats. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2013;37(3):273–282. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2013.37.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Chan M., Huang J., Li B., Ouyang W., Peng C., et al. Triterpenoid saponins from two Panax japonicus varietals used in Tujia Ethnomedicine. Current Traditional Medicine. 2015;1(2):122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.C, Liu H.C, Zhang L, Guo T.T, Wang P, Geng M.Y., et al. Synthesis and antitumor activities of naturally occurring oleanolic acid triterpenoid saponins and their derivatives. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;64:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.L., Wu Q.S., Wang Y.T., Zhang Q.W., Lu J.J. Extraction of Panax Chinese medicines and their anti-cancer effects on HEY ovarian cancer cells. Chinese Journal of Experimental Traditional Medical Formulae. 2016;8:105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Xu Y.R., Yang J.J., Wang W.Z., Zhang J.Q., Zhang R.M., et al. Discovery, semisynthesis, biological activities, and metabolism of ocotillol-type saponins. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2017;41(3):373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhao JP, Chen Y, Li W, Li B, Jian YQ, et al. Polyacetylenic Oleanane-Type Triterpene Saponins from the Roots of Panax japonicus. Journal of Natural Products. 2016;79(12):3079–3085. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H., Samukawa K.I., Fukuda S., Shiomoto H., Chun-ning T., Kubo M. Studies of Panax japonicus Fibrinolysis. Planta Med. 1989;55(01):18–21. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-961767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H., Samukawa K., Kubo M. Anti-hepatitic activity of ginsenoside Ro. Planta Medica. 1991;57(6):523–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei Z.G., Tan L.J., Wang J.F., Li X.L., Huang W.F., Zhou H.J. Fermented Chinese formula Shuan-Tong-Ling attenuates ischemic stroke by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis. Neural Regenaration Research. 2017;12(3):425. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.202946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanan P., Subramaniyam S., Mathiyalagan R., Yang D.C. Molecular signaling of ginsenosides Rb1, Rg1, and Rg3 and their mode of actions. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2018;42(2):123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K., Takeshita F., Samukawa K., Tani T., Matsuda H. Effects of ginseng rhizome and ginsenoside ro on testosterone 5α-reductase and hair re-growth in testosterone-treated mice: hair re-growth activities of ginseng rhizome and ginsenoside Ro. Phytother. Res. 2012;26(1):48–53. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen V.B., Linh Giang V.N., Waminal N.E., Park H.S., Kim N.H., Jang W., et al. Comprehensive comparative analysis of chloroplast genomes from seven Panax species and development of an authentication system. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2018;44(1):135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noriko K., Yasuko M., Junzo S. Studies on the constituents of panacis japonici rhizoma IV. Chemical Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1971;19(6):1103–1107. [Google Scholar]

- Olaleye O.E., Niu Wei, Du F.F., Wang F.Q., Xu F., Pintusophon S., et al. Multiple circulating saponins from intravenous ShenMai inhibit OATP1Bs in vitro: Potential joint precipitants of drug interactions. Acta pharmacologica Sinica. 2019;40(6):833–849. doi: 10.1038/s41401-018-0173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi G.M., Li J., Li Y.L., Li H.H., Du J. Adiponectin suppresses angiotensin II-induced inflammation and cardiac fibrosis through activation of macrophage autophagy. Endocrinology. 2014;155(6):2254–2265. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattanathongkom A., Lee J.B., Hayashi K., Sripanidkulchai B.O., Kanchanapoom T., Hayashi T. Evaluation of chikusetsusaponin IVa isolated from Alternanthera philoxeroides for its potency against viral replication. Planta Medica. 2009;75(8):829–835. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Wang W., Zhang X., Jiang Y., Yang X., Deng C., et al. Deglucose chikusetsusaponin IVa isolated from Rhizoma Panacis Majoris induces apoptosis in human HepG2 hepatoma cells. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2015;12(4):5494–5500. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L.J., Zhang X., Mei Z.G., Wang J.F., Li X.L., Huang W.F, et al. Fermented Chinese formula Shuan-Tong-Ling protects brain microvascular endothelial cells against oxidative stress injury. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016;2016:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2016/5154290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasneem S., Liu B., Li B., Choudhary M.I., Wang W. Molecular pharmacology of inflammation: Medicinal plants as anti-inflammatory agents. Pharmacological Research. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzong D.L., Noriko K., Junzo S. Studies of the constituents of panacis japonici rhizoma V. Chemical Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1976;24(2):253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wan J.Z., Deng L.L., Zhang C.C, Yuan Q., Liu J., Dun Y.Y., et al. Chikusetsu saponin V attenuates H 2 O 2 -induced oxidative stress in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells through Sirt1/PGC-1α/Mn-SOD signaling pathways. Canadian Journal of Physiology Pharmacology. 2016;94(9):919–928. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2015-0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.M., Long S.Q., Wu W.Y. Application of traditional chinese medicines as personalized therapy in human cancers. American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2018;46(05):953–970. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X18500507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Lu J.C., Lv C.N., Xu T.Y., Jia L.Y. Three new triterpenoid saponins from root of Gardenia jasminoides Ellis. Fitoterapia. 2012;83(8):1396–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Qi J., Li L., Wu T., Wang X., et al. Inhibitory effects of Chikusetsusaponin IVa on lipopolysaccharide-induced pro-inflammatory responses in THP-1 cells. International Journal of Immunopathology Pharmacology. 2015;28(3):308–317. doi: 10.1177/0394632015589519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.L., Xiao G.X., He S., Liu X.Y., Zhu L., Yang X.Y. Protection against acute cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by QiShenYiQi via neuroinflammatory network mobilization. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2020;125:109945. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.109945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Yuan D., Zheng J., Wu X., Wang J., Liu X., et al. Chikusetsu saponin IVa attenuates isoprenaline-induced myocardial fibrosis in mice through activation autophagy mediated by AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 signaling. Phytomedicine. 2018;58 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]