Abstract

Puerarin (Pue), known as a phytoestrogen, has salient bioactivities and is promising against cardiovascular diseases. This article summarizes the underlying molecular mechanisms of Pue in treating cardiovascular diseases, especially regulating the intracellular signal transduction, influencing ion channels, modulating the expression of microRNA, and impacting on the autophagy, which are mainly involved in the inflammatory signaling pathways, fatty acid/lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and the like. The protective effect of Pue against cardiovascular diseases mainly involves attenuating the myocardial injury and decreasing the myocardial fibrosis, improving the myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, as well as inhibiting the myocardial hypertrophy and atherosclerosis. The molecular mechanisms of Pue’s cardiovascular protective effects for the first time and comment on the state-of-the-art research methods and principles of Pue’s regulation of small molecules were reviewed, so as to provide the rationale for its basic research and clinical applications.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, molecular mechanism, puerarin, signaling pathways

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a major cause of death and health burden globally (Mirzadeh Azad et al., 2020, Piko et al., 2021). Therefore, the prevention and treatment of CVD are particularly imperative. The onset of CVD is often complicated by multiple symptoms, so clinical medications are mostly used in combination with multiple drugs, such as Compound Danshen Dripping Pills combined with conventional antihypertensive drugs in the treatment of hypertension (Chen et al., 2021) and Rosuvastatin combined with Ezetimibe Tablets against hyperlipidemia (Barrios & Escobar, 2021). Given the characteristics of multi-target, multi-channel, and multi-level interactions, searching for CVD related active ingredients from traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) is always a hot topic in and outside China (Li et al., 2018, Xu et al., 2021). For example, astragaloside IV displayed a neuroprotective effect in rats with neurological disorders through the Sirt1/Mapt pathway (Shi et al., 2021) and JAK2/STAT3 pathway (Xu, Yang, Huang, & Huang, 2021). Likewise, isoflavone puerarin (Pue), as a monomer derived from TCM extracts, also showed the multi-target effect.

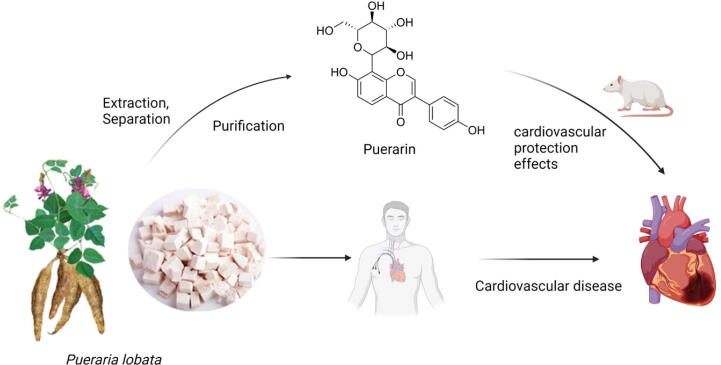

The main source of Pue (8-C-β-D-glucopyranosyl-7,4-hydroxy-isoflavone, C21H20O9, Fig. 1) is the dried roots of leguminous plant Pueraria lobata (Willd.) Ohwi. The Chinese Pharmacopoeia stipulates that the content of Pue in P. lobata shall not be less than 13%. P. lobata is sweet/pungent in flavor, cool in nature, and belongs to the meridians of spleen and stomach; it promotes body fluids and quenches thirst, raises yang and relieves diarrhea, and promotes meridian and collaterals. It is widely used for quenching thirst, treating dizziness, headache, stroke and hemiplegia, chest pain, among others (Wang, Nie, Zhu, & Liu, 2021). Modern pharmacological studies have shown that Pue has the noteworthy effects of lowering blood sugar, lowering lipids, lowering blood pressure and anti-myocardial ischemia (Song et al., 2014, Zhou et al., 2014), which are closely related with the traditional application of P. lobata. Modern pharmacology studies clarified that some components of Pue exhibited excellent estrogen-like effects (Dong et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2018), while epidemiological studies have associated the CVD morbidity with the level of endogenous estrogen in the body (Knowlton and Lee, 2012, Menazza and Murphy, 2016). However, the long-term estrogen replacement therapy increases the risk of endometrial cancer and breast cancer (Lan et al., 2017). Thus, Pue as a phytoestrogen has good potential application in CVD. Happily, the Pue injection has been used in the clinic and achieved certain therapeutic effects (Xie et al., 2018, Zheng et al., 2017). Pue exhibited various cardiovascular protective effects through various mechanisms of action, such as activating endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (Li et al., 2017) to reduce blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats, and inhibiting the rat myocardial fibrosis via the TGFβ pathway (Jin et al., 2017). However, so far the molecular mechanisms of Pue’s cardiovascular protective effect, as well as its basic studies and clinical applications, have not been well reviewed and summarized. Here, we reviewed the in vivo and in vitro pharmacological investigations of Pue against CVD in recent years, and summarized its molecular mechanisms and research methods (Table 1), with view to contributing to the subsequent drug target research and expansion of clinical applications.

Fig. 1.

Source of Pue and its cardioprotective effect.

Table 1.

Cardiovascular disease animal/cell model of Pue's cardiovascular protective effect and its potential mechanism on different signaling pathways.

| Animal/Cell models | Routes | Doses | Time | Pathways | Molecular changes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD (female, 150–180 g) + OVX + ACC | i.p. | 50 mg/kg/d | 8 week | PPARα | PPARα↑, NEFA↓, ATP↑ | (Hou et al., 2021) |

| C57BL6/J + AngⅡ (2.5 μg/kg,15 d) | oral | 50 mg/kg/d | 15 d | MicroRNA | miR-15b↑, miR-195↑ | (Zhang, Liu, & Han, 2016) |

| NRCs + H/R | Pre-treated | 50, 100, 200 μmol/L | 2 h | Autophagy | BAG3↑, LC3-II↑, p62↓, Akt↑, mTOR↓ |

(Tang et al., 2017) |

| SD + AB | SC | 100 mg/kg/d | 3 weeks | (Liu et al., 2015) | ||

| Primary cardiomyocytes + H/R | Pre-treated | 50, 100, 200 μmol/L | 24 h | (Ma, Gai, Yan, Jian, & Zhang, 2016) | ||

| C57BL6/J (male, 23.5–27.5 g) + TAC | Premixed in feed | 65 mg/kg/d | 1 week + 8 weeks | TGFβ-1/smad2 | TGF-β1↓, MCP-1↓, α-SMA↓, Smad2↓, Smad3↓, CO-1↓, CO-3↓ |

(Jin et al., 2017) |

| HUVEC + TGF-β1 (10 ng/mL) | Pre-treated | 10, 25, 50 μmol/L | 30 min + 48 h | (Jin et al., 2017) | ||

| C57BL6/J(male,18–22 g) + MI | i.p. (48 h) | 50, 100, 200 mg/kg/d | 4 weeks | (Tao et al., 2016) | ||

| Wistar rats (150–180 g) + TAC | oral | 400 mg/kg/d | 1 week + 10 weeks | TLR4-NF-κB | TLR4↓, NF-κB↓ | (Ni et al., 2020) |

| SD (150–180 g) + AB | i.p. | 50 mg/kg/d | 6 weeks | Nrf2 | Keap 1↓, Nrf2↑, ROS↓ |

(Cai et al., 2018) |

| NRCFs + AngⅡ (1 μmol/L) | 10, 100, 1000 μmol/L | 24 h | (Cai et al., 2018) | |||

| C57BL6/J (male, 25 ± 2 g) + ISO (5 mg/kg, 30 d) | oral | 600, 1200 mg/kg/d | 40 d | TGFβ-1 | PPARα↑, PPARγ↑, TGF-β1↓ | (Chen, Xue, & Xie, 2012) |

| SD (200–220 g) + STZ (60 mg/kg, 72 h) + ACC | i.p. | 50, 100, 200 mg/kg/d | 8 weeks | NF‑κB | TNF-α↓, NF‑κB ↓, COX-2↓, ICAM-1↓ | (Yin et al., 2019) |

| H9c2 + HG (33 nmol/L) | Pre-treated | 10−4, 10−5, 10−6 mol/L | 12 h | (Yin et al., 2019) | ||

| C57BL6/J (male, 20–25 g) + MI/R (30 min + 3 h/24 h) | i.p. | 100 mg/kg | 15/30 min | NLRP3 | SIRT1↑, NLRP3↓, TLR4↓ | (Wang et al., 2020) |

| SD (male, 240–260 g) + IR (30 min/24 h) | oral (40 min) | 10, 30, 100 mg/kg | 24 h | (Wang et al., 2021) | ||

| SD (male, 240–250 g) + IR (45 min/2h) | Jugular vein | 2.5 mL/kg (40 g/L) | 2 h | eNOS/NO | eNOS↑, NO↑ | (Li, Lin, Qiao, Ding, & Lu, 2015) |

| SD (male,180–200 g) + MI | i.p. | 50, 100 mg/kg/d | 4 weeks | VEGFA↑, Ang-Ⅰ↑, Ang-Ⅱ↑ | (Ai et al., 2015) | |

| SD (male, 220 ± 5 g) + IR(30 min/2h) | Tail vein | 50 mg/kg | 24 h | Autophagy | ANRIL↑ | (Han et al., 2021) |

| SD (male, 150–180 g) + ACC | i.p. | 50 mg/kg/d | 6 weeks | Nrf2 | Nrf2↑, HO-1↑, NQO1↑ | (Zhao et al., 2018) |

| Wistar rats (200–250 g) + burn | i.p. | 10 mg/kg | 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 h | p38-MAPK | NF‑κB ↓, TNF-α↓ | (Liu et al., 2015) |

| H9c2 + H/R (6 h/12 h) | Pre-treated | 50, 100, 200 μmol/L | 1 h | MicroRNA | MicroRNA-21↑ | (Xu et al., 2019) |

| HUVECs + TNFα (10 ng/mL) | After treatment | 10, 20, 50 μmol/L | 6 h | NF-κB | TNF-α↓, NF-κB↓ | (Hu, Zhang, Yang, Wang, & Sun, 2010) |

| New Zealand white rabbits (2.0–2.1 kg) + HLD | i.p. | 20 mg/kg/d | 6 weeks | (Ji, Du, Li, & Hu, 2016) | ||

| HAVSMCs + PM2.5 (400 mg/L) + 24 h | Pre-treated | 12.5, 25, 50 μmol/L | 1 week | eNOS/NO | eNOS↑,NO↑ | (Shi et al., 2019) |

| SHR (male), Wistar Kyoto (WKY) | i.p. | 40, 80 mg/kg/d | 9 weeks | (Shi et al., 2019) |

Note: i.p.: Intraperitoneal injection; SC: Subcutaneous injection; SD: Sprague–Dawley rats; OVX:Bilateral ovariectomy ACC:Abdominal aortic constriction; NRCs:Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes; AB: Aortic banding; H/R: Hypoxia/reoxygenation; HUVEC: Human umbilical vein endothelial cells; ISO: Isoprenaline; TAC: Transverse aortic constricition; HG: High-glucose; HAVSMCs: Human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells; SHR: Spontaneously hypertensive rats; HFD: High-fat diet; MI: Myocardial infarction; STZ: Streptozotocin.

2. Signaling pathways involved in Pue’s cardiovascular effects

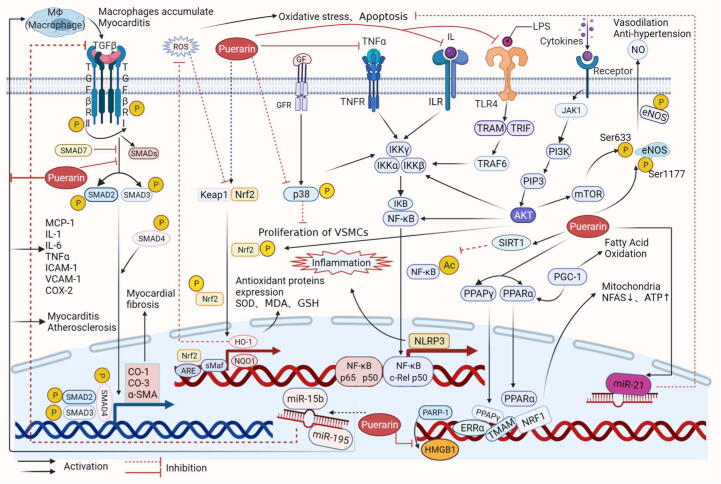

2.1. NF-κB signaling pathway

The nuclear factor‐kappa B (NF‐κB) signaling pathway is considered the canonical pathway in modulating the inflammatory response, in which there is the binding between extracellular stimulating factors and receptors on the cell membrane (Adelaja et al., 2021). The extracellular stimuli, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), activate IκB kinase (IKK), thereby releasing NF‑κB; the latter translocates to the nucleus and mediates the transcriptional regulation of pro-inflammatory genes (Tsai et al., 2015). Pue protected the myocardia by alleviating inflammatory responses (Deng et al., 2022, Ni et al., 2020). Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) helps maintaining the structural integrity of chromosomes and genome stability, participates in the DNA repair and cell death, and such like. High mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1) is a DNA binding protein in the nucleus; the activation of PARP-1 induces the release of pro-inflammatory HMGB1 from the nucleus (Bangert et al., 2016). It binds to Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and activates the TLR4, which subsequently leads to the activation of NF‐κB pathway to induce the inflammation and promote the fiber formation (Deng et al., 2022, Ni et al., 2020). Suppressing the expression of PARP1 could inhibit the binding of HMGB1 to DNA and prevent the release of HMGB1 into the extracellular fluid; Pue showed the inhibitory effect on PARP1 and prevented the TLR4-NF-κB inflammatory signaling pathway mediated by HMGB1 (Ni et al., 2020).

In the rat myocardial fibrosis (MF) model, Pue (400 mg/kg) was administered for 10 weeks (Ni et al., 2020). When compared with the control, the degree of MF in the Pue group was significantly suppressed. Extract rat primary cardiac fibroblasts (CFs) and use LPS to induce CFs fibrosis. The 5 μg/mL Pue reduced the levels of PARP1, HMGB1, inflammatory factors and fibrosis-related proteins α-SMA, collagen-1 and collagen-3 in primary cardiac fibroblasts (CFs) after three hours of exposure (Ni et al., 2020). The long-term hyperglycemia destroys the delicate equilibrium between inflammatory factors production and scavenging, leading to cardiomyocyte apoptosis, fibrosis, hypertrophy, which can further lead to ventricular dysfunction (Varga et al., 2015). Pue inhibited the TNF-α stimulation and ameliorated the diabetes-related myocarditis in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats (Yin et al., 2019). In rat hyperglycemia, TNF-α can be induced to stimulate cardiomyocytes, which subsequently leads to the activation of NF‐κB pathway to induce inflammation. Pue blocked this process and inhibited the release of inflammatory factors promoted by NF-κB (Hu et al., 2010, Yin et al., 2019). Atherosclerosis is driven and regulated by inflammatory cells, and the endothelial cell adhesion factors (adhesion molecules, AMs) are up-regulated (Bäck, Yurdagul, Tabas, Öörni, & Kovanen, 2019). In vitro, Pue (20 μmol/L and 50 μmol/L) inhibited the AMs expression stimulated by TNF-α in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) by regulating the NF‑κB pathway for 2 h (Hu et al., 2010). In a rabbit atherosclerosis model induced by the high-fat diet, the continuous intraperitoneal injection of Pue (20 mg/kg/d) for six weeks inhibited the development of atherosclerosis, as Pue inhibited IκBα and the phosphorylation of p65-NF-κB blocked its translocation into the nucleus, thereby preventing the production of adhesion factors (Ji et al., 2016). Both in vivo and in vitro studies confirmed that Pue blocked the inflammatory pathway regulated by NF-κB (Fig. 2) and reduced a series of reactions after myocardial injury by inhibiting the inflammation.

Fig. 2.

Molecular mechanism of Pue protects myocardium by regulating different signal pathways.

2.2. Nrf2 signaling pathway

Pue also inhibits the oxidative stress pathway to exert the cardiovascular protection (Cai et al., 2018, Zhao et al., 2018). Nrf2 is an essential endogenous transcription factor responding to the oxidative stress in myocardial cells and myocardial fibroblasts (Fig. 2); it is also an important negative regulator of myocardial fibroblast proliferation (Li et al., 2009, Zhao et al., 2018). Once the myocardium is damaged, the expression of Nrf2 increases temporarily and then drops to the basal level. The activation of Nrf2 inhibited the oxidative stress and eliminated the reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Cai et al., 2018, Luo et al., 2018). In rats, after the abdominal aortic band was narrowed and the cardiomyocytes were induced by angiotensin II (AngII), the expression of Nrf2 in cardiomyocytes was inhibited, and the level of ROS increased, which promoted the myocardial fibrosis (Cai et al., 2018). The intraperitoneal injection of Pue (50 mg/kg/d) showed a significant inhibition of myocardial fibrosis in these rats. In vitro, Pue reduced the myocardial Keap1 by activating Nrf2, and promoted the expression of two downstream target proteins HO-1 and recombinant NADH Dehydrogenase, Quinone 1 (NQO1), thereby reducing the level of ROS in myocardial cells (Cai et al., 2018). In a rat model of myocardial hypertrophy induced by abdominal aortic constriction (AAC), the intraperitoneal injection of Pue (50 mg/kg/d) activated Nrf2 and inhibited the activation of p38-MAPK, up-regulated the metabolic enzyme UGT1A1, promoted the activation of Nrf2 and regulated the downstream genes HO-1 and NQO1 (Zhao et al., 2018). Therefore, the myocardial protective effect of Pue may be related to the activation of Nrf2-HO-1/NQO1 pathway, which improves the antioxidant level of cardiomyocytes and reduces the myocardial damage caused by oxidative stress.

2.3. PPARα signaling pathway

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) is a ligand-activated transcription factor that plays important roles in the fatty acid metabolism and energy homeostasis; pathologically, the occurrence and development of cardiac hypertrophy involve the inactivation or activation of PPARα (Planavila, Iglesias, Giralt, & Villarroya, 2011). PGC-1 directly binds to PPARα or enhances the PPARα activity, and regulates the expression of diverse genes related to the mitochondrial energy metabolism (Barjaktarovic, Merl-Pham, Braga-Tanaka, Tanaka, & Azimzadeh, 2019). In cardiomyocytes, when PPARα is inhibited, the expressions of downstream estrogen-related receptors (ERRα), nuclear respiration factor (NFR1), and TFAM involved in mitochondrial biogenesis are inhibited, leading to disorders of mitochondrial energy metabolism and causing cardiac muscle hypertrophy, which may evolve to heart failure (Dong et al., 2018, Zhang et al., 2020). Pue, as a PPAR agonist, could increase the PPARα expression and regulate the mitochondrial energy metabolism of cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2). Pue protected against pressure-overload-induced cardiac structure injury and exerted beneficial effects against the cardiac hypertrophy in a rat model (Hou et al., 2021). In vitro, its molecular mechanism is to upregulate the expression of PPARα, PGC-1α and PGC-1β, up-regulate the expression of fatty acid metabolism-related genes and decrease the expression of glucose metabolism-related genes, thereby increasing the production of ATP and reducing the hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes caused by fatty acids accumulation. Strikingly, the inhibition of PPARα by GW6471 treatment restored these changes (Hou et al., 2021). These results suggest that Pue may be an agonist of PPARα, which prevents the myocardial hypertrophy by impacting on the myocardial lipid-related metabolism and preventing the fatty acid accumulation.

2.4. TGF-β signaling pathway

Many cells have TGF-β receptors on the surface, and the TGF-β signaling pathway is an important regulator of fibroblast activation and differentiation (Blyszczuk et al., 2017). After TGF-β binds to its specific receptor TβRⅡ, it phosphorylates TβRⅠ, thereby activating the downstream SMAD2/3 signaling, which in turn regulates the expressions of collagen (collagen-1 and collagen-3) and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) of myofibroblasts (Yao et al., 2019). Thus, enhancing the TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway could increase the area of fibrosis; Pue reduced the production of TGF-β and inhibited the myocardial fibrosis (Fig. 2) (Chen et al., 2012). In mice undergoing the transverse aortic coarctation (TAC) for eight weeks, Pue (65 mg/kg/d) was administered for one week after the operation (Jin et al., 2017). Pue protected mouse heart fibrosis by blocking the endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) process (Jin et al., 2017). In a HUVEC EndMT model, Pue up-regulated the PPAR-γ and TGF-β1/Smad2-mediated inhibition of EndMT, thereby inhibiting expressions of collagen-1/-3 and myofibroblast expression of α-SMA (Jin et al., 2017). In mice, Pue (200 mg/kg/d) reduced the aggregation of macrophages by inhibiting the expression of MCP-1 and decreased the TGF-β expression in macrophages, thereby inhibiting the TGF-β/SMAD pathway and reducing myocardial fibrosis after myocardial infarction (Tao et al., 2016).

2.5. NLRP3 signaling pathway

The dysregulation of NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome could cause excessive inflammation and plays a pivotal role in many human diseases (Huang, Xu, & Zhou, 2021). NF-κB can be rapidly transferred to the nucleus after being activated by various signaling pathways, where it up-regulates the transcriptions of NLRP3 inflammasome and downstream active protein precursors, and triggers a series of inflammatory responses (Schunk et al., 2021, Seok et al., 2020). SIRT1 is a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) dependent class III histone deacetylase (HDAC) that targets NF-kB, a critical transcription factor in the regulation of proinflammatory cytokine production to adapt the gene expression level to the metabolic activity; if the SIRT1 signal is activated, the transfer of Ac-NF-κB and NF-κB to the nucleus can be inhibited (Yang et al., 2012). Pue inhibits the inflammation caused by myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury via this pathway (Fig. 2). In the mouse myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury model, the intraperitoneal injection of Pue (100 mg/kg) 15 min before ischemia effectively inhibited the cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by the inflammation (Wang et al., 2020). Pue activated the SIRT1 signal and inhibited the transfer of NF-κB to the nucleus, thereby inhibiting the expression of NLRP3; nicotinamide (NAM), an inhibitor of SIRT1, reversed the effects of Pue (Wang et al., 2020). In rats, Pue inhibited the NLRP3 inflammasome through the TLR4/Myd88/NF-κB pathway to prevent the myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury (Wang et al., 2021). The activated TLR4 promoted the transfer of NF-κB to the nucleus and enhanced the expression of NLRP3. Pue acts through the TLR4/Myd88/NF-κB pathway, but the specific mechanism remains elusive (Wang et al., 2021). It is more possible that Pue protects against the myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury through the NLRP3 signaling pathway. It is worth mentioning that SIRT1 is currently the most widely studied Sirtuin protein and a popular drug design target in recent years. However, the effect of Pue on the SIRT1 signal has not been fully investigated, and further studies are warranted.

2.6. eNOS/NO signaling pathway

The endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and NO have significant cardioprotective effects (Fraccarollo et al., 2008). In rats with myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury, the Pue injection (40 mg/mL) had no direct effect on the expression of eNOS in rat myocardial cells, but it up-regulated the phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179/1177 and Ser635/633, thereby up-regulating the expression of eNOS, promoting the production of NO (Fig. 2), and alleviating the myocardial injury (Li et al., 2015). In spontaneously hypertensive rats, Pue of 40 mg/kg/d significantly reduced the blood pressure (Shi et al., 2019), with eNOS as a key target in lowering the blood pressure by Pue.

In rats, Pue upregulated the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), vascular endothelin-1, and vascular endothelin-2, which improved the endothelial function and promoted the myocardial angiogenesis. Pue improved the vascular endothelial function, but whether eNOS is involved in this process is uncertain (Ai et al., 2015). In AngII-induced hypertensive rats, Pue protected against the vascular endothelial dysfunction and end-organ damage by up-regulating the phosphorylated Enos (Li et al., 2017), thereby reducing the systolic blood pressure. Pue can relax blood vessels, lower the blood pressure and improve the vascular endothelial function via the eNOS signaling pathway (Fig. 2); it is a potential antihypertensive drug.

2.7. p38-MAPK signaling pathway

The mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) is a group of serine-threonine protein kinases that can be activated by different extracellular stimuli, such as cytokines, neurotransmitters, hormones, cellular stress, cellular adhesion, among others (Yang et al., 2015). When cells are stimulated by external factors, p38-MAPK is activated (Fig. 2), which subsequently activates NF-κB in the nucleus and promotes the development of inflammation (Ito et al., 2006). Pue (10 mg/kg) improved the ultrastructure of cardiomyocytes after severe burns in rats (Liu et al., 2015). It inhibited the activation of p38-MAPK, reduced the content of TNF-α in serum, and inhibited the activity of myeloperoxidase (MPO) and decreased the malondialdehyde (MDA) content in the myocardial tissue (Liu et al., 2015). It is believed that the migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) into the intima are the key pathological basis of atherosclerosis (Wan, Liu, & Yang, 2018). In human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells (HAVSMCs), Pue inhibited the p38-MAPK signaling pathway, which inhibited the proliferation of VSMCs caused by fine particulate matter (PM2.5), thereby playing a role in anti-atherosclerosis (Wan et al., 2018). Therefore, the inhibition of p38-MAPK by Pue can not only inhibit inflammation and protect the myocardia, but also inhibit the proliferation of VSMCs to prevent atherosclerosis (Fig. 2). However, the knowledge about the crosstalk between the above signaling pathways is very limited, and how these pathways cooperate or antagonize warrants deeper studies.

3. Pue regulates expression of microRNA

Some studies have shown that mRNAs is an important regulatory factor of gene expression and is also involved in the regulation of cardiomyocyte apoptosis (Natarajan, Smith, Wehrkamp, Mohr, & Mott, 2013). MicroRNA-15b and microRNA-195 are two expressed genes belonging to the miR-15 family. MiR-15 family members share a common seed domain, which targets multiple members in the canonical and atypical TGF-β pathways (Fig. 2). The activation of TGF-β pathway causes the myocardial fibrosis and induces the heart disease (Porrello et al., 2013). The overexpression of miR-15b and miR-195 interferes with the activation of SMAD2 and SMAD3, leading to an inhibition in the TGF-β signal transduction (Tijsen et al., 2014). Pue attenuates the cardiac hypertrophy partly through increasing the miR-15b/195 expression; suppressing the non-canonical TGF-β pathway and knocking out miR-15b and miR-195 eliminated the protective effect of Pue on the myocardial hypertrophy (Zhang et al., 2016). MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) is one of the most highly expressed miRNAs in cardiac macrophages and emerged as an important miRNA in cardiac biology; it is a crucial post-transcriptional regulator of gene expression and plays an important role in cell differentiation, apoptosis and oxidative stress (Li et al., 2020). The loss of miR-21 targeting genes in mouse macrophages prevented its pro-inflammatory polarization and subsequent pressure-overload-induced cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction (Ramanujam et al., 2021). Therefore, miR-21 could be a central regulator of cardiac fibrosis. In the hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) model of rat H9C2 cardiomyocytes, Pue inhibited the oxidative stress and apoptosis of H/R-treated H9C2 cells by up-regulating miR-21 (Fig. 2); after the transfection of miR‑21 inhibitor, the inhibitory effect of Pue on the apoptosis of H9C2 cardiomyocytes was eliminated (Xu et al., 2019). mRNA-122 regulates Caspase-8 and promotes the apoptosis of mouse cardiomyocytes (Zhang et al., 2017), inhibition of miR-24 can inhibit endothelial cell apoptosis and reduce myocardial infarction size (Fiedler et al., 2011). Knockdown of miR-208a helps to attenuate apoptosis and improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction (Hasahya et al., 2015). Thus, whether Pue may also interact with other miRNA needs to be further verified.

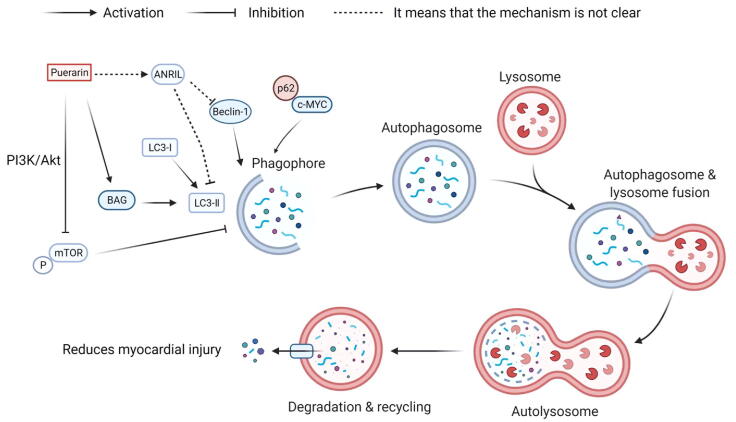

4. Pue regulates autophagy

Some studies have shown that enhancing autophagy at the early stage of ischemia–reperfusion injury reduced the apoptosis and played a protective role (Gu et al., 2020). BAG3 is a protein involved in the regulation of autophagy; the overexpression of BAG3 promoted the formation of LC3-II and the process of autophagy (Knezevic et al., 2015). In rats, Pue directly increased the transcription and translation of BAG3 (Fig. 3), thereby increasing the autophagy of hypoxia-reoxygenated cardiomyocytes and inhibiting cardiomyocyte apoptosis (Ma et al., 2016). Pue decreased the activation of mTOR, an important inhibitor of autophagy induction, by blocking PI3K/Akt (Tang et al., 2017, Yuan et al., 2014); repressing the mTOR increased the autophagic activity. Pue may promote the phosphorylation of Akt, inhibit the activity of mTOR, reduce the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-Ⅰ and promote the degradation of p62-c-MYC, thereby protect the myocardium from the hypoxia-reperfusion injury. The mechanism is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Molecular mechanism of Pue through regulation of autophagy.

Interestingly, recent reports indicated that Pue ameliorated the myocardial injury caused by reperfusion of the rat heart by inhibiting autophagy (Han et al., 2021), which is contrary to the results of previous studies (Fig. 3). In the H/R model of rat H9C2 cardiomyocytes, the expression of autophagy-related genes LC3-II and Beclin-1 was up-regulated, and the expression of LC3-I was inhibited, indicating that the H/R injury promoted the autophagy of cardiomyocytes. The transfection of ANRIL reduced the viability of cardiomyocytes and aggravated the H/R damage by promoting the autophagy (Han et al., 2021). However, this effect was partially reversed by 400 μmol/L Pue. In vivo, Pue up-regulated the expression of ANRIL (Han et al., 2021) and inhibited the process of autophagy. Why the results of two reports are contrary may be related to the role of autophagy itself. Autophagy is a double-edged sword (Lockshin & Zakeri, 2004); the excessive or insufficient autophagy may cause diseases, and Pue may help regulating the balance of autophagy.

5. Other mechanisms

The unbalanced uptake and oxidation of fatty acids lead to the lipid accumulation in heart tissues, which is also crucial for the occurrence and progression of heart disease. The fatty acid translocator (FAT or CD36) is a long-chain fatty acid (LC-FA) transporter that significantly participates in the fatty acid uptake in cells. After the cellular uptake of LC-FA, the complex liposomes form and there is the β-oxidation process under the action of fatty acid-binding protein (FABP); the expression of CD36 in the nucleus is promoted, which increases the uptake of LC-FA on the membrane (Wu et al., 2020), thereby forming a cycle to induce the cardiac fat toxicity. Pue could affect the expression of FATs and inhibit the myocardial lipotoxicity (Fig. 4). In the lipotoxic cardiomyopathy mouse model, Pue (100 mg/kg/d) inhibited the Na+-K+-ATPase-mediated CD36 expression and systemic inflammation, reduced the myocardial lipotoxicity (Qin et al., 2016), and improved the myocardial injury.

Fig. 4.

Diagram of mechanism of action of Pue in regulating ion channels and CD36 expression.

Of note, Pue inhibited the sodium ion reflux (Lin et al., 2020), potassium ion efflux (Xu et al., 2014, Zhang et al., 2011), calcium ion overload (Zhang, Wei, Sun, & Gao, 2012), and sodium/calcium exchange (Zhang et al., 2003); it dose-dependently prolongs the duration of action potential, thereby improving arrhythmia (Fig. 4) (Xu et al., 2016).

6. Discussion and conclusion

Each signaling pathway regulates downstream molecules based on its unique function or action. Nevertheless, no matter how complex their regulatory mechanisms are, they directly or indirectly affect the onset of CVDs, and there may be a synergistic effect between them. The miRNA indirectly affects the myocardial fibrosis by affecting TGF-β (Tijsen et al., 2014), and the expression of miRNA also affects the cardiomyocyte apoptosis (Li et al., 2020), but the specific mode of action is currently unknown. The inflammatory pathways, especially TGF-β, TLR, SIRT1, and p38-MAPK pathways, activated NF-κB (Ni et al., 2020, Wan et al., 2018, Wang et al., 2021, Wang et al., 2020, Yin et al., 2019), increased the NLRP3 expression to induce inflammation, and promoted myocarditis, myocardial fibrosis and atherosclerosis; Pue could act on these targets and pathways to inhibit the production of inflammatory factors. The TGF-β pathway can not only activate the SMADs family, up-regulate the phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3, and increase the production of CO-1, CO-3 and α-SMA to promote the formation of myocardial fibrosis (Jin et al., 2017), but also activate p38-MAPK, thereby activating NF-κB and promoting the expression of inflammatory factors (Wan et al., 2018). The activation of p38-MAPK may also activate PPARα, increase mitochondrial energy metabolism, reduce fatty acid accumulation, increase ATP synthesis, and prevent the cardiac hypertrophy caused by the fat accumulation. However, whether the above-mentioned effects of Pue are mediated by the p38-MAPK pathway has not been confirmed. Nrf2 is a critical regulator of the antioxidant response. After it is activated, it can promote the expression of HO-1 and NQO1, thereby eliminating ROS and inhibiting the oxidative stress. It is also regulated by a variety of pathways. Pue can directly activate Nrf2, and Nrf2 could also be activated through the Akt pathway after activating the SIRT1 signal (Wang et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2020), but this has not been confirmed. In addition, there are contradictions in the mechanism of Pue. For example, in regulating autophagy, Pue can directly increased the transcription and translation of BAG3 (Ma et al., 2016), thereby increasing the autophagy of myocardial cells after injury and inhibiting the myocardial apoptosis. However, Pue was thought to up-regulate ANRIL to inhibit the autophagy (Han et al., 2021). The contradiction may be related to the role of autophagy under physiological conditions. Autophagy repairs cells by degrading aging organelles and helps maintain the normal cellular activities. However, the excessive or insufficient autophagy can lead to the disease onset (Lockshin & Zakeri, 2004); Pue may regulate the balance of autophagy process as a neutralizer. It is interesting to screen out other autophagy modulators that are structurally similar to Pue.

The above-mentioned pathways have differential effects on cellular functions, e.g., the PPARα pathway affects the lipid metabolism (Planavila et al., 2011), NF-κB and NLRP3 (Schunk et al., 2021, Seok et al., 2020) impact on the inflammation, Nrf2 influences the oxidative stress and apoptosis (Li et al., 2009, Zhao et al., 2018), autophagy affects the apoptosis, the eNOS/NO pathway (Fraccarollo et al., 2008) influences the blood vessels, TGF-β affects the myocardial fibrosis, which indirectly explain the complexity of the causes of CVD. In fact, these pathways constitute the regulatory network of CVD at the molecular level. Pue showed multiple effects on these pathways and targets. As long as Pue has an effect on any position in the network, it may eventually have a profound impact on CVD.

Understanding the effect of Pue on these pathways can not only guide the basic research of Pue or P. lobata, but also guide clinical drug taboos, drug compatibility and predicting potential adverse reactions. On the other hand, it helps provide evidence-based medicines for the clinical application of P. lobata. Pue can be used in cardiovascular indications such as anti-myocardial fibrosis, anti-myocardial ischemia, inhibiting myocardial hypertrophy and anti-atherosclerosis, and the mechanism studies of Pue help ensure the rational use in clinical settings. In this review, the dose and duration of Pue used in animal studies are also summarized, which has reference value for the clinical administration of Pue or P. lobata. Despite a lot of studies on the molecular mechanism of Pue against CVDs, many underlying mechanisms should be further unveiled, and there might be more potential pathways to explore, so as to provide references for rational clinical application and evidence-based medicines.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Weida Qin: Visualization, Investigation, Software, Validation. Jianghong Guo: Writing – review & editing. Wenfeng Gou: Writing – review & editing. Shaohua Wu: . Na Guo: . Yuping Zhao: Conceptualization, Methodology. Wenbin Hou: Conceptualization, Methodology.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China [Grant No. 2017YFC1702901]; Fundamental Research Funds for the central public welfare research institutes [Project No. JBGS2021002]; China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (CACMS) innovation fund [Grant No. CI2021A05031].

Contributor Information

Yuping Zhao, Email: 18810084632@163.com.

Wenbin Hou, Email: houwenbin@irm-cams.ac.cn.

References

- Adelaja A., Taylor B., Sheu K., Liu Y., Luecke S., Hoffmann A. Six distinct NFκB signaling codons convey discrete information to distinguish stimuli and enable appropriate macrophage responses. Immunity. 2021;54(5):916–930. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai F., Chen M.H., Yu B., Yang Y., Xu G.Z., Gui F., et al. Puerarin accelerate scardiac angiogenesis and improves cardiac function of myocardial infarction by upregulating VEGFA, Ang-1 and Ang-2 in rats. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 2015;8(11):20821–20828. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäck M., Yurdagul A., Tabas I., Öörni K., Kovanen P. Inflammation and its resolution in atherosclerosis: Mediators and therapeutic opportunities. Nature Reviews: Cardiology. 2019;16(7):389–406. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangert A., Andrassy M., Müller A., Bockstahler M., Fischer A., Volz C., et al. Critical role of RAGE and HMGB1 in inflammatory heart disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016;113(2):E155–E164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522288113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barjaktarovic Z., Merl-Pham J., Braga-Tanaka I., Tanaka S., Azimzadeh O. Hyperacetylation of cardiac mitochondrial proteins is associated with metabolic impairment and sirtuin downregulation after chronic total body irradiation of ApoE -/- mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019;20(20):5239. doi: 10.3390/ijms20205239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios V., Escobar C. Fixed-dose combination of rosuvastatin and ezetimibe: Treating hypercholesteremia according to cardiovascular risk. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. 2021;14(7):1–14. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2021.1925539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyszczuk P., Müller-Edenborn B., Valenta T., Osto E., Stellato M., Behnke S., et al. Transforming growth factor-β-dependent Wnt secretion controls myofibroblast formation and myocardial fibrosis progression in experimental autoimmune myocarditis. European Heart Journal. 2017;38(18):1413–1425. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S.A., Hou N., Zhao G.J., Liu X.W., He Y.Y., Liu H.L., et al. Nrf2 is a key regulator on puerarin preventing cardiac fibrosis and upregulating metabolic enzymes UGT1A1 in rats. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2018;9(15):540–552. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Xue J., Xie M.L. Puerarin prevents isoprenaline-induced myocardial fibrosis in mice by reduction of myocardial TGF-β1 expression. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2012;23(9):1080–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Peng Y.Y., Yang F.W., Hu H.Y., Liu C.X., Zhang J.H. Meta-analysis of clinical efficacy and safety of Compound Danshen Dripping Pills combined with conventional antihypertensive drugs in treatment of hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2021;46(10):2578–2587. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20210222.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng C., Zhao L., Yang Z., Shang J.J., Wang C.Y., Shen M.Z., et al. Targeting HMGB1 for the treatment of sepsis and sepsis-induced organ injury. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2022;43(3):520–528. doi: 10.1038/s41401-021-00676-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H.W., Zhang L.F., Bao S.L. AMPK regulates energy metabolism through the SIRT1 signaling pathway to improve myocardial hypertrophy. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2018;22(9):2757–2766. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201805_14973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z., Zhang M.M., Li H.X., Zhan Q.P., Lai F., Wu H. Structural characterization and immunomodulatory activity of a novel polysaccharide from Pueraria lobata (Willd.) Ohwi root. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020;154(2):1556–1564. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler J., Jazbutyte V., Kirchmaier B.C., Gupta S.K., Lorenzen J., Hartmann D., et al. MicroRNA-24 regulates vascularity after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2011;124(6):720–730. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.039008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraccarollo D., Widder J., Galuppo P., Thum T., Tsikas D., Hoffmann M., et al. Improvement in left ventricular remodeling by the endothelial nitric oxide synthase enhancer AVE9488 after experimental myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;118(8):818–827. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.717702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu C.J., Li L.W., Huang Y.F., Qian D.F., Liu W., Zhang C.L., et al. Salidroside ameliorates mitochondria-dependent neuronal apoptosis after spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury partially through inhibiting oxidative stress and promoting mitophagy. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2020;2020(1):3549704. doi: 10.1155/2020/3549704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y.H., Wang H.L., Wang Y., Dong P.S., Jia J.J., Yang S.H. Puerarin protects cardiomyocytes from ischemia–reperfusion injury by upregulating LncRNA ANRIL and inhibiting autophagy. Cell and Tissue Research. 2021;385(9):739–751. doi: 10.1007/s00441-021-03463-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasahya T., Kai M., Bangwei W., et al. MicroRNA-208a dysregulates apoptosis genes expression and promotes cardiomyocyte apoptosis during ischemia and its silencing improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Mediators of Inflammation. 2015;2015(6):479123–479133. doi: 10.1155/2015/479123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou N., Huang Y., Cai S.A., Yuan W.C., Li L.R., Liu X.W., et al. Puerarin ameliorated pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy in ovariectomized rats through activation of the PPARα/PGC-1 pathway. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2021;42(1):55–67. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0401-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W.Z., Zhang Q., Yang X.J., Wang Y.Y., Sun L. Puerarin inhibits adhesion molecule expression in tnf-alpha-stimulated human endothelial cells via modulation of the nuclear factor kappaB pathway. Pharmacology. 2010;85(1):27–35. doi: 10.1159/000264938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Xu W., Zhou R. NLRP3 inflammasome activation and cell death. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2021;18(9):2114–2127. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00740-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K., Hirao A., Arai F., Takubo K., Matsuoka S., Miyamoto K., et al. Reactive oxygen species act through p38 MAPK to limit the lifespan of hematopoietic stem cells. Nature Medicine. 2006;12(4):446–451. doi: 10.1038/nm1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji L., Du Q., Li Y.T., Hu W.Z. Puerarin inhibits the inflammatory response in atherosclerosis via modulation of the NF-κB pathway in a rabbit model. Pharmacological Reports. 2016;68(5):1054–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y.G., Yuan Y., Wu Q.Q., Zhang N., Fan D., Che Y., et al. Puerarin protects against cardiac fibrosis associated with the inhibition of TGF-β1/Smad2-mediated endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. PPAR Research. 2017;2017(4):2647129. doi: 10.1155/2017/2647129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knezevic T., Myers V., Gordon J., Tilley D., Sharp T., Wang J., et al. BAG3: A new player in the heart failure paradigm. Heart Failure Reviews. 2015;20(4):423–434. doi: 10.1007/s10741-015-9487-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton A., Lee A. Estrogen and the cardiovascular system. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2012;135(1):54–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan X.F., Zhang X.J., Lin Y.N., Wang Q., Xu H.J., Zhou L.N.…Li Q.Y. Estradiol regulates Txnip and prevents intermittent hypoxia-induced vascular injury. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):10318. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10442-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.J., Mao C.Y., Zhou E., You J.Y., Gao E.H., Han Z.H.…Wang C.Q. MicroRNA-21 mediates a positive feedback on angiotensin II-induced myofibroblast transformation. Journal of Inflammation Research. 2020;13(3):1007–1020. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S285714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Lin A.X., Qiao D.F., Ding Q., Lu D.Q. Puerarin attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Basic & Clinical Medicine. 2015;35(06):836–837. [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Ichikawa T., Villacorta L., Janicki J., Brower G., Yamamoto M., et al. Nrf2 protects against maladaptive cardiac responses to hemodynamic stress. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2009;29(11):1843–1850. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.189480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Yu H.Y., Wang S.J., Wang W., Chen Q., Ma Y.M., et al. Natural products, an important resource for discovery of multitarget drugs and functional food for regulation of hepatic glucose metabolism. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2018;12(2):121–135. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S151860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.J., Lin Y.H., Zhou H.Y., Li Y., Wang A.M., Wang H.X., et al. Puerarin protects against endothelial dysfunction and end-organ damage in Ang II-induced hypertension. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. 2017;39(1):58–64. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2016.1200603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.H., Ni X.B., Zhang J.W., Ou C.W., He X.Q., Dai W.J., et al. Effect of puerarin on action potential and sodium channel activation in human hypertrophic cardiomyocytes. Bioscience Reports. 2020;40(2) doi: 10.1042/BSR20193369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Wu Z.Y., Li Y.P., Ou C.W., Huang Z.J., Zhang J.W., et al. Puerarin prevents cardiac hypertrophy induced by pressure overload through activation of autophagy. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2015;464(3):908–915. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Ren H.B., Chen X.L., Wang F., Wang R.S., Zhou B., et al. Puerarin attenuates severe burn-induced acute myocardial injury in rats. Burns. 2015;41(8):1748–1757. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockshin R.A., Zakeri Z. Apoptosis, autophagy, and more. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2004;36(12):2405–2419. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J.F., Shen X.Y., Lio C.K., Dai Y., Cheng C.S., Liu J.X., et al. Activation of Nrf2/HO-1 pathway by nardochinoid C inhibits inflammation and oxidative stress in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2018;9:911–929. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.Y., Gai Y., Yan J.P., Jian J., Zhang Y.Y. Puerarin attenuates anoxia/reoxygenation injury through enhancing Bcl-2 associated athanogene 3 expression, a modulator of apoptosis and autophagy. Medical Science Monitor. 2016;22(11):977–983. doi: 10.12659/MSM.897379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menazza S., Murphy E. The expanding complexity of estrogen receptor signaling in the cardiovascular system. Circulation Research. 2016;118(6):994–1007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.305376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzadeh Azad F., Arabian M., Maleki M., Malakootian M. Small molecules with big impacts on cardiovascular diseases. Biochemical Genetics. 2020;58(3):359–383. doi: 10.1007/s10528-020-09948-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan S.K., Smith M.A., Wehrkamp C.J., Mohr A.M., Mott J.L. MicroRNA function in human diseases. Medical Epigenetics. 2013;1(1):106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ni S.Y., Zhong X.L., Li Z.H., Huang D.J., Xu W.T., Zhou Y., et al. Puerarin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced myocardial fibrosis by inhibiting PARP-1 to prevent HMGB1-mediated TLR4-NF-κB signaling pathway. Cardiovascular Toxicology. 2020;20(1):482–491. doi: 10.1007/s12012-020-09571-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piko P., Kosa Z., Sandor J., Adany R. Comparative risk assessment for the development of cardiovascular diseases in the Hungarian general and Roma population. Scientific Reports. 2021;11(1):3085–3096. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82689-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planavila A., Iglesias R., Giralt M., Villarroya F. Sirt1 acts in association with PPARα to protect the heart from hypertrophy, metabolic dysregulation, and inflammation. Cardiovascular Research. 2011;90(2):276–284. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrello E., Mahmoud A., Simpson E., Johnson B., Grinsfelder D., Canseco D., et al. Regulation of neonatal and adult mammalian heart regeneration by the miR-15 family. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(1):187–192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208863110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H., Zhang Y., Wang R., Du X.Y., Li L.P., Du H.W. Puerarin suppresses Na+-K+-ATPase-mediated systemic inflammation and CD36 expression, and alleviates cardiac lipotoxicity in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2016;68(6):465–472. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanujam D., Schön A., Beck C., Vaccarello P., Felician G., Dueck A., et al. MicroRNA-21-dependent macrophage-to-fibroblast signaling determines the cardiac response to pressure overload. Circulation. 2021;143(15):1513–1525. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schunk S., Kleber M., Mrz W., Pang S., Speer T. Genetically determined NLRP3 inflammasome activation associates with systemic inflammation and cardiovascular mortality. European Heart Journal. 2021;42(18):1742–1756. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seok J., Kang H., Cho Y., Lee H., Lee J. Regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by post-translational modifications and small molecules. Frontiers in Immunology. 2020;11(2) doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.618231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W.L., Yuan R., Chen X., Xin Q.Q., Wang Y., Shang X.H., et al. Puerarin reduces blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats by targeting eNOS. American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2019;47(1):19–38. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X19500022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y.H., Zhang X.L., Ying P.J., Wu Z.Q., Lin L.L., Chen W., et al. Neuroprotective effect of astragaloside IV on cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury rats through Sirt1/Mapt pathway. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2021;12(6) doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.639898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W., Li Y.J., Qiao X., Qian Y., Ye M. Chemistry of the Chinese herbal medicine Puerariae Radix (Ge-Gen): A review. Journal of Chinese Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2014;23(6):347–360. [Google Scholar]

- Tang H.X., Song X.D., Ling Y.N., Wang X.B., Yang P.Z., Luo T., et al. Puerarin attenuates myocardial hypoxia/reoxygenation injury by inhibiting autophagy via the Akt signaling pathway. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2017;15(6):3747–3754. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Z.W., Ge Y.B., Zhou N.T., Wang Y.L., Cheng W., Yang Z.J. Puerarin inhibits cardiac fibrosis via monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 and the transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) pathway in myocardial infarction mice. American Journal of Translational Research. 2016;8(10):4425–4433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tijsen A., van der Made I., van den Hoogenhof M., Wijnen W., van Deel E., de Groot N., et al. The microRNA-15 family inhibits the TGFβ-pathway in the heart. Cardiovascular Research. 2014;104(1):61–71. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C., Wu C., Lee J., Chang S.N., Kuo Y., Wang Y., et al. TNF-α down-regulates sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase expression and leads to left ventricular diastolic dysfunction through binding of NF-κB to promoter response element. Cardiovascular Research. 2015;105(3):318–329. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga Z., Giricz Z., Liaudet L., Haskó G., Ferdinandy P., Pacher P. Interplay of oxidative, nitrosative/nitrative stress, inflammation, cell death and autophagy in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2015;1852(2):232–242. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Q., Liu Z.Y., Yang Y.P. Puerarin inhibits vascular smooth muscle cells proliferation induced by fine particulate matter via suppressing of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2018;18(1):146. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2206-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.S., Yan L.Y., Sun S.C., Jiang Y., S.Y., Y., Wang S.B., et al. Puerarin protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation via TLR4/Myd88/NF-κB pathway in rats. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. 2021;56(05):1343–1351. [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.J., Zhang W.Q., Liu J.J., Cui Y., Cui J.Z. Piceatannol protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-induced apoptosis and oxidative stress via the Sirt1/FoxO1 signaling pathway. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2020;22(6):5399–5411. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.M., Nie J., Zhu W.F., Liu H.H. Discussion of the function of Pueraria. Journal of Basic Chinese Medicine. 2021;27(10):1641–1643. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.K., Chen R.R., Li J.H., Chen J.Y., Li W., Niu X.L., et al. Puerarin protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting inflammation and the NLRP3 inflammasome: The role of the SIRT1/NF-κB pathway. International Immunopharmacology. 2020;89(PB) doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W.C., Wang S.S., Liu Q.Z., Shan T., Wang X.X., Feng J., et al. AMPK facilitates intestinal long-chain fatty acid uptake by manipulating CD36 expression and translocation. The FASEB Journal. 2020;34(4):4852–4869. doi: 10.1096/fj.201901994R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X.S., Dong Y.Z., Mu D.P., Pan X.L., Zhang F.Y. Evaluation on safety of puerarin injection in clinical use. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2018;43(19):3956–3961. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20180709.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Zhang L., Gao Z., Ma M.J., Zhang H. Effects of puerarin on action potential of ventricular myocytes of rats. Progress in Modern Biomedicine. 2014;14(19):3635–3637. [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Zhao M.X., Liang S.H., Huang Q.S., Xiao Y.C., Ye L., et al. The effects of puerarin on rat ventricular myocytes and the potential mechanism. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1):35475. doi: 10.1038/srep35475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.X., Pan W., Qian J.F., Liu F., Dong H.Q., Liu Q.J. MicroRNA-21 contributes to the puerarin-induced cardioprotection via suppression of apoptosis and oxidative stress in a cell model of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2019;20(1):719–727. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2019.10266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.Y., Zhang Y.Q., Wang P., Zhang J.H., Chen H., Zhang L.Q., et al. A comprehensive review of integrative pharmacology-based investigation: A paradigm shift in traditional Chinese medicine. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. B. 2021;11(6):1379–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z.H., Yang D.F., Huang X.J., Huang H. Astragaloside IV protects 6-hydroxydopamine-induced SH-SY5Y cell model of Parkinson's disease via activating the JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2021;15(4) doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.631501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.Y., Zhang W., Pan H., Feldser H., Lainez E., Miller C., et al. SIRT1 activators suppress inflammatory responses through promotion of p65 deacetylation and inhibition of NF-κB activity. PloS One. 2012;7(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Wu Z.H., Renier N., Simon D., Uryu K., Park D., et al. Pathological axonal death through a MAPK cascade that triggers a local energy deficit. Cell. 2015;160(1–2):161–176. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y.F., Hu C.Q., Song Q.X., Li Y., Da X.W., Yu Y.B., et al. ADAMTS16 activates latent TGF-β, accentuating fibrosis and dysfunction of the pressure-overloaded heart. Cardiovascular Research. 2019;116(5):956–969. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin M.S., Zhang Y.C., Xu S.H., Liu J.J., Sun X.H., Liang C., et al. Puerarin prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy in vivo and in vitro by inhibition of inflammation. Journal of Asian Natural Products Research. 2019;21(5):476–493. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2017.1405941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Zong J., Zhou H., Bian Z.Y., Deng W., Dai J., et al. Puerarin attenuates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Journal of Cardiology. 2014;63(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G.Q., Hao X.M., Dai D.Z., Fu Y., Zhou P.A., Wu C.H. Puerarin blocks Na+ current in rat ventricular myocytes. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2003;24(12):1212–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Zhang L., Zhang Q., Yang X.Z., Yu J.Y., Shun S.H., et al. Puerarin: A novel antagonist to inward rectifier potassium channel (IK1) Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2011;352(2):117–123. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0746-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Wei X., Sun Y., Gao J.H. Effect of puerarin on related cytokines and calcium of cardiomyocytes induced by high glucose. Chinese Journal of Basic Medicine in Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2012;18(3):266–268. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.J., Wang J., Zhao H.P., Luo Y.M. Effects of three flavonoids from an ancient traditional Chinese medicine Radix Puerariae on geriatric diseases. Brain Circulation. 2018;4(4):174–184. doi: 10.4103/bc.bc_13_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.Z., Liu Y.X., Han Q.L. Puerarin attenuates cardiac hypertrophy partly through increasing Mir-15b/195 expression and suppressing non-canonical transforming growth factor Beta (Tgfβ) signal pathway. Medical Science Monitor. 2016;22(3):1516–1523. doi: 10.12659/MSM.895877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Su H.L., Ahmed R.Z., Zheng Y.X., Jin X.T. Critical biomarkers for myocardial damage by fine particulate matter: Focused on PPARα-regulated energy metabolism. Environmental Pollution. 2020;264(2020) doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.W., Li H., Chen S.S., Li Y., Cui Z.Y., Ma J. MicroRNA-122 regulates caspase-8 and promotes the apoptosis of mouse cardiomyocytes. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2017;50(2) doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20165760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G., Hou N., Cai S.A., Liu X., Li A.Q., Cheng C., et al. Contributions of Nrf2 to puerarin prevention of cardiac hypertrophy and its metabolic enzymes expression in rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2018;366(3):458–469. doi: 10.1124/jpet.118.248369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Q.H., Li X.L., Mei Z.G., Xiong L., Mei Q.X., Wang J.F., et al. Efficacy and safety of puerarin injection in curing acute ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine. 2017;96(1) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.X., Zhang H., Peng C. Puerarin: A review of pharmacological effects. Phytotherapy Research. 2014;28(7):961–975. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]