Abstract

The ferric uptake regulator, Fur, represses iron uptake and siderophore biosynthetic genes under iron-replete conditions. Here we report in vitro solution studies on Vibrio anguillarum Fur binding to the consensus 19-bp Escherichia coli iron box in the presence of several divalent metals. We found that V. anguillarum Fur binds the iron box in the presence of Mn2+, Co2+, Cd2+, and to a lesser extent Ni2+ but, unlike E. coli Fur, not in the presence of Zn2+. We also found that V. anguillarum Fur contains a structural zinc ion that is necessary yet alone is insufficient for DNA binding.

Iron is essential for survival and virulence of bacterial pathogens; however, its concentration in host tissues is limited. To acquire iron, bacterial pathogens rely on iron uptake systems that consist of an iron siderophore (a small-molecule chelator) and membrane transport proteins, which import Fe3+-siderophore complexes into the cell (7, 18). These systems are regulated by the DNA-binding protein Fur (ferric uptake regulator) in response to iron availability (3, 11, 20). When the intracellular concentration of iron increases above a certain level, Fur represses the transcription of genes encoding components of the membrane transport system as well as enzymes involved in siderophore biosynthesis.

To date, the most extensive biochemical studies have been limited to the Escherichia coli Fur protein, which in the presence of various divalent metals that act as corepressors binds a conserved 19-bp operator sequence, the iron box, which is located in the promoter region of iron uptake genes (4, 5, 9). Moreover, these studies have indicated that E. coli Fur possesses two metal ion-binding sites. One, the corepressor binding site, uses histidines and carboxylate ligands to coordinate binding of Fe2+ (and two of its functional mimics, Mn2+ and Co2+) (1). This event promotes a conformational change that leads to DNA binding. The other cation-binding site is involved in protein structure and stability and binds Zn2+ with high affinity, using the thiols of Cys92 and Cys95 as two of the four coordinating ligands (2, 3, 14). These cysteines are essential for E. coli Fur activity both in vivo and in vitro (6).

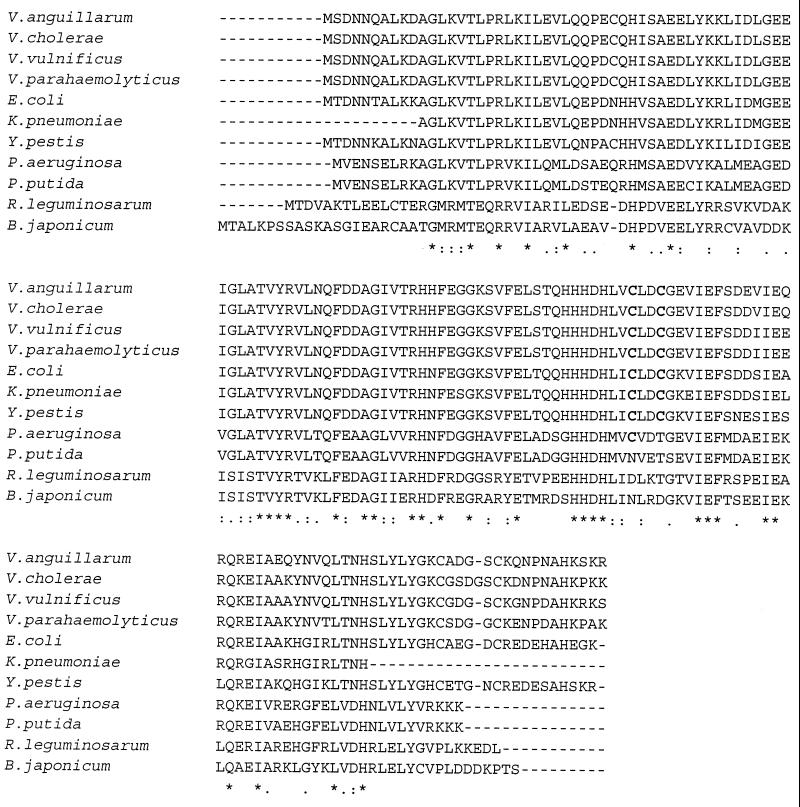

Fur homologues have been identified in multiple bacteria, where they also regulate iron acquisition. In the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum strain 775, Fur represses production of a siderophore, anguibactin, and of Fe3+-anguibactin transport proteins in response to abundant iron (21). V. anguillarum Fur is closely related to its counterparts from other Vibrio species, including Vibrio cholerae (93% sequence identity), Vibrio vulnificus (91%), and Vibrio parahaemolyticus (91%) (Fig. 1). Yet V. anguillarum Fur is less homologous to E. coli Fur (76% sequence identity), and the two proteins have different numbers of cysteines and histidines (Fig. 1). Therefore, to test whether V. anguillarum Fur is functionally distinct from E. coli Fur, we characterized the DNA- and divalent-cation-binding properties of V. anguillarum Fur. We also investigated the effect of chemical modification of cysteines on the ability of Fur to bind a consensus 19-bp iron box in a metal-dependent manner. Here, we report that Fur binds the iron box in the presence of Mn2+, Co2+, Cd2+, and to a lesser extent Ni2+ but, unlike E. coli Fur, not in the presence of Zn2+. In addition, V. anguillarum Fur contains a structural Zn2+ ion that appears to be required for DNA binding.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of selected Fur sequences. Asterisks and colons indicate positions of identical and similar amino acids, respectively. Cysteines 92 and 95 of E. coli Fur and their counterparts in other Fur proteins are shown in bold.

The V. anguillarum fur gene subcloned into the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible pT7-5 vector (21) was kindly provided by A. M. Wertheimer. E. coli BL21(DE3) cells transformed with this vector were induced with 1 mM IPTG. Fur, which contains nine histidines, binds tightly to nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Novagen) and is eluted in 1 M imidazole. Protein purity was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. After dialysis against the storage buffer [0.1 M Tris HCl (pH 7.9), 0.1 M NaCl, and 0.1 to 0.2 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP HCl), in the presence or absence of 1 mM EDTA], the protein concentration was measured spectrophotometrically by using an extinction coefficient, ɛ280, of 12,007 M−1 cm−1, which was determined from amino acid hydrolysis.

The affinity of Fur for DNA was measured by fluorescence anisotropy (16). As it is performed in solution, this method provides a true equilibrium measurement of binding. All measurements were done using a Beacon fluorescence polarization instrument (Pan Vera) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 494 and 520 nm, respectively. The DNA used in this work is a 25-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide that encompasses the 19-bp iron box from E. coli (5). Each DNA duplex was prepared by annealing two complementary 25-mers, one of which contained a 5′ fluorescein label (Genosys and Oligos, Etc.). The sequence of the labeled nucleotide is 5′-GCAGATAATGATAATCATTATCGGA-3′. The inverted repeat of the iron box is underlined. All fluorescence anisotropy measurements were carried out at 25°C in 1 ml of binding buffer (100 mM HEPES with potassium salt [pH 7.5], 250 mM potassium glutamate, 150 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM magnesium acetate, and 5% glycerol) (15), with 1 μg of poly(dI · dC) per ml and 2 nM labeled DNA duplex. Fur was titrated into the mixture, and measurements were made after a 30-s equilibration. The DNA-binding assays were carried out initially in the presence or absence of Mn2+, which has been shown to substitute effectively for the easily oxidized Fe2+ (9).

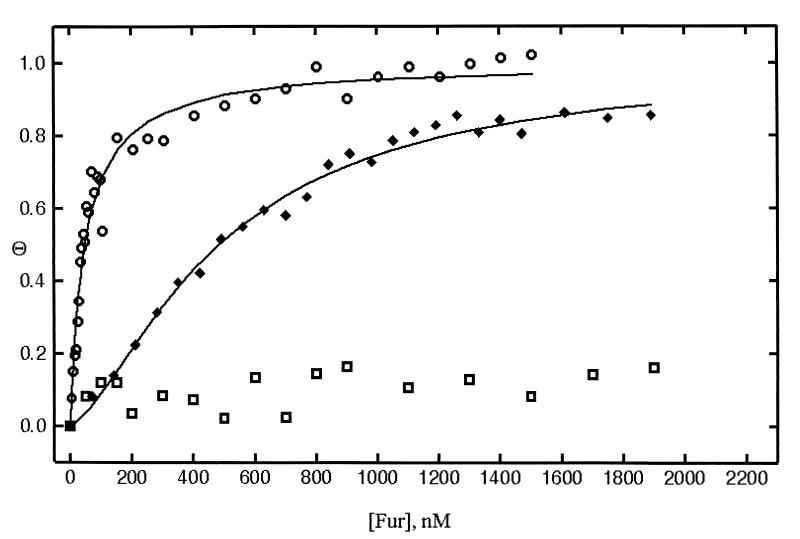

In the presence of Mn2+, V. anguillarum Fur binds the consensus E. coli iron box with a Kd of 50 nM. In the absence of Mn2+, V. anguillarum Fur does not bind the iron box and no changes in fluorescence anisotropy are observed, even at Fur concentrations greater than 2 μM (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Fur also binds its cognate DNA site with high affinity in the presence of Co2+ (Kd = 30 nM) or Cd2+ (Kd = 50 nM). In the presence of Ni2+, V. anguillarum binds the iron box specifically, but with lower affinity (Kd = 230 nM). In the presence of Zn2+, Fur does not bind the iron box, and the binding data are similar to those recorded in the absence of metal. By contrast, in the presence of Zn2+, E. coli Fur binds the iron box specifically, albeit with a lower affinity (4, 9). These data indicate that, unlike E. coli Fur, V. anguillarum Fur cannot use Zn2+ as a corepressor ion.

TABLE 1.

Kds of V. anguillarum Fur for the consensus iron box operator

| Fur | Metala | Kd (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| Unmodified | Mn2+ | 50 ± 2 |

| Unmodified | Co2+ | 30 ± 1 |

| Unmodified | Cd2+ | 50 ± 2 |

| Unmodified | Ni2+ | 230 ± 15 |

| Unmodified | None | >2,000 |

| Unmodified | Zn2+ | >2,000 |

| DTNB modified | Mn2+ | 500 ± 20 |

The metal ion concentration was 1 mM in each binding experiment.

FIG. 2.

Binding isotherms of unmodified Fur to the consensus iron box in the presence (○) and absence (□) of Mn2+ and binding of DTNB-modified Fur in the presence of Mn2+ (⧫). Binding data were analyzed and fitted by nonlinear least-squares regression (Sigma Plot) to the following equation describing a cooperative binding model: θ = (A − A0)/(Amax − A0) = [P]h/(Kd + [P]h), where θ is the fractional saturation of the operator with Fur, A is anisotropy, Amax is maximum anisotropy, A0 is initial anisotropy, [P] is the total protein concentration, and h is the Hill or cooperativity coefficient, which was in the range of 2.0 to 2.5. The graph shows θ as a function of total Fur concentration.

To determine the concentration of Mn2+ that induces half-maximal binding, 2 nM iron box DNA in the presence of 500 nM V. anguillarum Fur was titrated with MnSO4. The concentration of Mn2+ at which Fur achieves half-maximal DNA binding (apparent Kd) is 90 μM (data not shown). This affinity is very similar to that found for E. coli Fur (12) and suggests that the corepressor-binding sites of these two proteins are similar.

Recent studies have shown that E. coli Fur cysteine residues 92 and 95 are ligands for a structural Zn2+ ion (2, 14). The binding of this divalent cation is stabile and requires extreme treatment to effect its removal (2). Since these cysteines are conserved in V. anguillarum Fur, we wanted to determine whether V. anguillarum Fur, like its E. coli counterpart, contained a structural Zn2+ coordinated by cysteines. To do so, we measured the Zn2+ content of Fur protein using a Varian-Techtron flame atomic absorption spectrometer (λ = 213.9 nm). Fur that was dialyzed against storage buffer, with or without 1 mM EDTA, contained 1.4 ± 0.1 (mean ± standard deviation from three measurements per sample) mol of Zn2+ per mol of Fur. Interestingly, Fur dialyzed extensively against 50 mM EDTA also contained 1.4 ± 0.1 mol of Zn2+ per mol of protein. These amounts are different from those for the E. coli Fur protein, for which 0.5 to 0.8 (17) or 0.9 (2) mol of Zn2+ was found per mol of EDTA-treated protein, but 2.1 mol of Zn2+ was detected per mol of EDTA-free protein (2). The presence of only one Zn2+ ion per monomer in V. anguillarum Fur versus two Zn2+ ions in E. coli Fur correlates with the inability of V. anguillarum Fur to use Zn2+ as a corepressor and suggests that the corepressor-binding site of V. anguillarum cannot bind Zn2+, whereas that of E. coli Fur can.

Next, we set out to determine the role of cysteines in Zn2+ coordination. To do so, we quantified the accessibility of the thiol side chains of the five cysteines of V. anguillarum as measured by their chemical modification by 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) (10, 19). If Cys92, Cys95, and possibly other cysteine residues were taking part in Zn2+ ion coordination, their chemical modification would eliminate Zn2+ from the protein sample. Our results showed that in the presence of 1 mM EDTA under both nondenaturing and denaturing conditions, 5.2 mol of cysteine per mol of V. anguillarum Fur was modified, which indicates that all five cysteine residues were accessible to DTNB. After DTNB labeling, Fur was dialyzed against its storage buffer, and subsequent Zn2+ analysis indicated the presence of 0.15 ± 0.05 mol of Zn2+ per mol of DTNB-labeled Fur protein. Concomitant with this dramatic decrease in Zn2+ content is a 10-fold-lower affinity of DTNB-labeled Fur for the iron box (Kd = 500 nM) in the presence of 1 mM Mn2+ ion.

The results of our thiol modification experiments indicate that a Zn2+ ion likely serves as the structural cation in V. anguillarum Fur, because modification of all five cysteines eliminates Zn2+ and significantly diminishes DNA binding. These results are similar to those reported for the E. coli Fur, which binds Zn2+ at a structural site (14) using cysteines 92 and 95, and this Zn2+ stabilizes the protein (2). Specifically, mutagenesis of these two cysteines in E. coli Fur (6) as well as their chemical modification (8) results in diminished DNA binding. Further experiments are necessary to determine whether cysteines 92 and 95 are responsible for Zn2+ binding in V. anguillarum Fur. While these two cysteines are conserved between the E. coli and V. anguillarum Fur proteins, they are replaced in the Fur proteins of several other bacteria, such as Pseudomonas putida and Bradyrhizobium japonicum (Fig. 1) (13). Hence, it is unclear whether the structural Zn2+ found in E. coli and V. anguillarum Fur is universally used in Fur proteins from other bacteria and whether the presence of cysteines at positions 92 and 95 is indicative of the structural Zn2+-binding site. Although necessary, this Zn2+ is not sufficient for high-affinity DNA binding by V. anguillarum Fur, which also requires the presence of a divalent corepressor ion, such as Mn2+. On the contrary, E. coli Fur was recently reported to bind its operator with high affinity in the presence of only its structural Zn2+ (2). However, this finding will require additional investigation. Perhaps a side-by-side study of the two Fur proteins would clarify the basis of their different metal ion-binding properties.

In summary, our results reveal that the closely related E. coli and V. anguillarum Fur proteins possess comparable divalent cation- and DNA-binding characteristics, albeit with significant differences. These findings illustrate the overall conservation of function and metal specificity of Fur proteins from these different gram-negative bacteria and thus expand our understanding of these essential regulatory proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Ralle (Oregon Graduate Institute, Beaverton) for help with measurements of Zn2+ content.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants from NIH to R.G.B. and to J.H.C. E.E.Z. is the recipient of an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adrait A, Jacquamet L, Le Pape L, Gonzalez de Peredo A, Aberdam D, Hazemann J L, Latour J M, Michaud-Soret I. Spectroscopic and saturation magnetization properties of the manganese- and cobalt-substituted Fur (ferric uptake regulation) protein from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6248–6260. doi: 10.1021/bi9823232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Althaus E W, Outten C E, Olson K E, Cao H, O'Halloran T V. The ferric uptake regulation (Fur) repressor is a zinc metalloprotein. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6559–6569. doi: 10.1021/bi982788s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagg A, Neilands J B. Molecular mechanism of regulation of siderophore-mediated iron assimilation. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:509–518. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.4.509-518.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagg A, Neilands J B. Ferric uptake regulation protein acts as a repressor, employing iron (II) as a cofactor to bind the operator of an iron transport operon in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1987;26:5471–5477. doi: 10.1021/bi00391a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calderwood S B, Mekalanos J J. Confirmation of the Fur operator site by insertion of a synthetic oligonucleotide into an operon fusion plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1015–1017. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.1015-1017.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coy M, Doyle C, Besser J, Neilands J B. Site-directed mutagenesis of the ferric uptake regulation gene of Escherichia coli. Biometals. 1994;7:292–298. doi: 10.1007/BF00144124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crosa J H. Signal transduction and transcriptional and posttranscriptional control of iron-regulated genes in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:319–336. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.319-336.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Cardayre S, Neilands J B. Structure-activity correlations for the ferric uptake regulation (fur) repressor protein of Escherichia coli K12. In: Frankel R B, Blakemore R P, editors. Iron biominerals. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 387–396. [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Lorenzo V, Wee S, Herrero M, Neilands J B. Operator sequences of the aerobactin operon of plasmid ColV-K30 binding the ferric uptake regulation (fur) repressor. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2624–2630. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2624-2630.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellman G L. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escolar L, Pérez-Martín J, de Lorenzo V. Opening the iron box: transcriptional metalloregulation by the Fur protein. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6223–6229. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6223-6229.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamed M Y, Neilands J B, Huynh V. Binding of the ferric uptake regulation repressor protein (Fur) to Mn(II), Fe(II), Co(II), and Cu(II) ions as co-repressors: electronic absorption, equilibrium, and 57Fe Mossbauer studies. J Inorg Biochem. 1993;50:193–210. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(93)80025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamza I, Hassett R, O'Brian M R. Identification of a functional fur gene in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5843–5846. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.18.5843-5846.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacquamet L, Aberdam D, Adrait A, Hazemann J L, Latour J M, Michaud-Soret I. X-ray absorption spectroscopy of a new zinc site in the fur protein from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2564–2571. doi: 10.1021/bi9721344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leirmo S, Harrison C, Cayley D S, Burgess R R, Record M T., Jr Replacement of potassium chloride by potassium glutamate dramatically enhances protein-DNA interactions in vitro. Biochemistry. 1987;26:2095–2101. doi: 10.1021/bi00382a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lundblad J R, Laurance M, Goodman R H. Fluorescence polarization analysis of protein-DNA and protein-protein interactions. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:607–612. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.6.8776720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michaud-Soret I, Adrait A, Jaquinod M, Forest E, Touati D, Latour J M. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry analysis of the apo- and metal-substituted forms of the Fur protein. FEBS Lett. 1997;413:473–476. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00963-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neilands J B. Siderophores: structure and function of microbial iron transport compounds. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26723–26726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riddles P W, Blakeley R L, Zerner B. Reassessment of Ellman's reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1983;91:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)91010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stojiljcovic I, Baumler A J, Hantke K. Fur regulon in gram-negative bacteria. Identification and characterization of new iron-regulated Escherichia coli genes by a fur titration assay. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:531–545. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolmasky M E, Wertheimer A M, Actis L A, Crosa J H. Characterization of the Vibrio anguillarum fur gene: role in regulation of expression of the FatA outer membrane protein and catechols. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:213–220. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.213-220.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]