Abstract

The gene encoding alginate lyase (algL) in Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae was cloned, sequenced, and overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Alginate lyase activity was optimal when the pH was 7.0 and when assays were conducted at 42°C in the presence of 0.2 M NaCl. In substrate specificity studies, AlgL from P. syringae showed a preference for deacetylated polymannuronic acid. Sequence alignment with other alginate lyases revealed conserved regions within AlgL likely to be important for the structure and/or function of the enzyme. Site-directed mutagenesis of histidine and tryptophan residues at positions 204 and 207, respectively, indicated that these amino acids are critical for lyase activity.

Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae causes disease in many plant species and produces the exopolysaccharide alginate, a linear polymer of O-acetylated β-1,4-linked d-mannuronic and l-guluronic residues (7, 11). Alginate functions as a virulence factor in P. syringae and also enhances epiphytic fitness, resistance to desiccation, and tolerance to toxic molecules (22, 29).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a leading cause of mortality in cystic fibrosis patients (24). Alginate contributes to the virulence of P. aeruginosa and protects the organism from antibiotics (13) and phagocytosis (1). The alginate biosynthetic and regulatory genes are located in several discrete regions of the P. aeruginosa chromosome (9). The alginate biosynthetic operon in P. aeruginosa is located at 34 min (4), and it is arranged similarly in P. syringae (21). Several genes in P. syringae have been identified that have homologs in P. aeruginosa, including algA, algD, algF, algG, alg44, alg8, algL, and algT (14, 21). Of particular interest to us was algL, which encodes alginate lyase.

Alginate lyases depolymerize alginate by cleaving the β-1,4 glycosidic bond, resulting in a molecule containing an unsaturated uronic acid residue at the nonreducing end (10, 15, 27). They prefer d-mannuronic or l-guluronic acid residues and may be affected by acetylation (10, 27). Alginate lyases from bacteria, algae, invertebrates, fungi, and bacteriophages have been characterized (27).

P. syringae pv. syringae FF5 produces low levels of alginate in vitro and appears nonmucoid (16); however, FF5 exhibits a mucoid colony morphology following the introduction of the 200-kb plasmid pPSR12 (16). Mutagenesis of FF5(pPSR12) resulted in the isolation of several alginate-defective mutants, including FF5.31, which contains a Tn5 insertion in algL (21).

Cloning of algL.

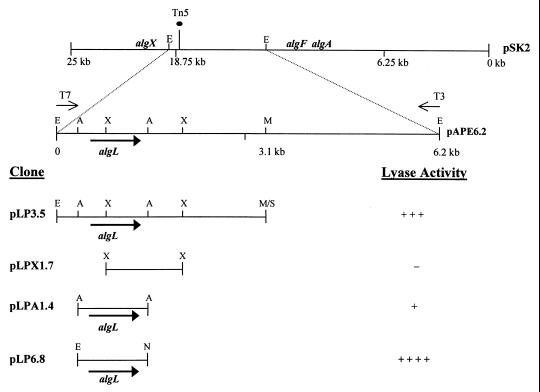

Escherichia coli strains (Table 1) were maintained on L medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C, and ampicillin was added at a concentration of 100 μg/ml. Pseudomonas spp. were grown on King's medium B (17) and cultured at 28°C (P. syringae) or 37°C (P. aeruginosa). pAPE6.2, which contains algL, algF, and algA (21), was used to construct pLP3.5, pLPX1.7, and pLPA1.4 (Fig. 1; Table 1). All genes were oriented to facilitate transcription from the T7 promoter of pBluescript SK+. To optimize the expression of algL, a 1.4-kb EcoRI/NotI fragment from pLPA1.4 was subcloned in pET21a in the same orientation as the T7 promoter and named pLP6.8 (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this studya

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm | Novagen |

| P. syringae pv. syringae FF5 | Cur; contains pPSR12; stably mucoid | 16 |

| P. aeruginosa FRD462 | algG4 (polyM-producing derivative of FRD1) | 8 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript SK(+) | Apr; ColE1 origin | Stratagene |

| pET21a | Apr; ColE1 origin | Novagen |

| pET21b | Apr; ColE1 origin | Novagen |

| pAPE6.2 | Apr; a 6.2-kb EcoRI fragment in pBluescript SK+; contains algL from P. syringae FF5 | 21 |

| pLP3.5 | Apr; a 3.5-kb EcoRI/MluI(SmaI) fragment from pAPE6.2 in pBluescript SK+ | This study |

| pLPX1.7 | Apr; a 1.7-kb XmnI fragment from pAPE6.2 in pBluescript SK+ | This study |

| pLPA1.4 | Apr; a 1.4-kb AflIII fragment from pAPE6.2 in pBluescript SK+ | This study |

| pLP6.8 | Apr; a 1.4-kb EcoRI/NotI fragment from pLPA1.4 in pET21a | This study |

| pLPH204A | Apr; a 1.1-kb EcoRI/XhoI fragment with mutated algL (His→Ala) in pET21b | This study |

| pLPW207A | Apr; a 1.1-kb EcoRI/XhoI fragment with mutated algL (Trp→Ala) in pET21b | This study |

Abbreviations: Apr, ampicillin resistance; Cur, copper resistance.

FIG. 1.

Constructs used to localize, sequence, and overexpress algL from P. syringae pv. syringae. pSK2 contains the alginate structural gene cluster from P. syringae pv. syringae FF5 (21). The location of the Tn5 insertion in the algL mutant FF5.31 is indicated (●), and the transcriptional orientation for algL is shown (→). Restriction site abbreviations: A, AflIII; E, EcoRI; M, MluI; N, NotI; S, SalI; and X, XmnI. Symbols for lyase activity: −, no activity; +, 50 to 100; +++, 500 to 750; ++++, 750 to 1,000.

Overproduction of AlgL and measurement of alginate lyase activity.

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells containing various constructs were grown at 37°C until the optical density at 600 nm was ∼0.6. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a concentration of 1.0 mM, and cells were incubated an additional 3 h at 37°C. Whole-cell protein extracts were prepared and separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels (23). For the isolation of periplasmic alginate lyase, cells were grown at 27°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6, induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (1.0 mM), and incubated an additional 6 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation (8,000 × g for 15 min), and the periplasmic fraction was isolated by temperature shock (5). Alginate lyase activity was measured by the thiobarbituric acid assay (26) and recorded as enzyme units (EU), with 1 EU equal to the amount of AlgL needed to produce 1 μmol of β-formyl-pyruvate/min. The protein concentration was determined by measuring the A280 where an absorbance of 1.0 = 1 mg of protein/ml.

BL21(DE3) cells containing pLP3.5 and pLPA1.4 had AlgL activity, whereas cells containing pLPX1.7 did not (Table 2). These results localized algL between nucleotides 400 and 1800 with respect to the 5′ EcoRI site in pLP3.5, a hypothesis which was confirmed by sequence analysis. AlgL was overproduced in E. coli BL21(DE3) containing pLP6.8, and high levels of lyase activity correlated with the induction of a ∼40-kDa band, which was found to be related to AlgL from P. aeruginosa when analyzed by immunoblotting.

TABLE 2.

Alginate lyase activity in E. coli BL21(DE3) containing various constructs

| Construct | AlgL activity (EU/ml)a | Protein concentration (mg/ml) | Specific activity (EU/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pBluescript SK+ | 0 | 3.15 | 0 |

| pLP3.5 | 523 | 4.42 | 118 |

| pLPX1.7 | 0 | 2.86 | 0 |

| pLPA1.4 | 82 | 2.27 | 36 |

| pET21a | 0 | 3.10 | 0 |

| pLP6.8 | 806 | 3.65 | 221 |

Numbers of EU/ml were determined with the thiobarbituric acid assay. See the text for an explanation.

Sequence analysis.

The translational start for algL was located at bp 477 with respect to the 5′ EcoRI site in pAPE6.2 (Fig. 1), and the sequence extended to a stop codon at bp 1611. A potential ribosome-binding site was present 7 bp upstream from the start codon. The deduced protein product of algL contained 378 amino acids with a predicted N-terminal signal peptide. The N terminus of partially purified AlgL was sequenced, and the first 10 residues (A L V P P K G Y D A) confirmed that the protein was cleaved between 2 alanine residues (A28 and A29). AlgL was found to have a mass of 42,541 Da and an isoelectric point of 8.19 when analyzed using PeptideSort (version 10.0; University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group).

Multiple sequence alignments of AlgL and site-directed mutagenesis.

AlgL from P. syringae was related to AlgL from Halomonas marina (76%), P. aeruginosa (63%), Azotobacter chroococcum (61%), and Azotobacter vinelandii (59%). CLUSTALX (25) was used to construct a multiple sequence alignment of alginate lyases. The region containing NNHSYW (residues 202 to 207 in P. syringae AlgL) was conserved among bacterial alginate lyases and included the active site identified in the crystal structure of alginate lyase A1-III from Sphingomonas (28). The importance of these residues in the activity of AlgL from P. syringae was investigated by replacing the histidine (H204) and tryptophan (W207) residues with alanine.

Mutant algL genes were constructed by a two-step PCR (2) using mutagenic oligonucleotides and primers located at the 5′ and 3′ ends of algL. H204 was replaced with alanine (GCG) using the primer set 1 (5′ AATCAACAACGCGTCGTACTGGGCTGC), which contained an AflIII site (boldface). W207 was replaced with alanine using the primer set 2 (5′ AACCACTCGTACGCGGCTGCCTGGTCG). The products of the first PCR were ∼700 or 500 bp when the mutagenic oligonucleotides were used with the 5′- or 3′-end primers, respectively. The products of the first PCR were combined and used as a template in a second PCR with the 5′- and 3′-end primers. The resulting 1.1-kb PCR products were subcloned as EcoRI-XhoI fragments into pET21b, resulting in pLPH204A (His→Ala) and pLPW207A (Trp→Ala). When these constructs were overproduced in E. coli BL21(DE3), neither mutant protein had lyase activity, suggesting a role for these residues in substrate binding or enzyme catalysis (28).

Biochemical properties of AlgL.

The pH optimum for AlgL was investigated using 15 mM sodium citrate and 30 mM NaPO4 (pHs 5 and 6), 30 mM NaPO4 (pH 7), and 30 mM Tris (pHs 8 and 9). The optimum pH for AlgL was 7.0, and only 50% activity was obtained at pH 5.0. AlgL activity was not reduced by 1 mM EDTA, indicating that the enzyme does not require divalent cations. Therefore, all subsequent assays were conducted at pH 7.0 without divalent cations. AlgL did not require NaCl for activity; however, the addition of 0.2 M NaCl enhanced lyase activity by ∼70%. The optimum temperature for AlgL was 42°C, which is similar to that for other intracellular lyases (12, 19). The kinetics of AlgL were measured using different concentrations of sodium alginate from Macrocytis pyrifera (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) as described previously (6). The apparent Km for AlgL was 3.4 × 10−4 M (sugar residues) when the data were analyzed using HYPER.EXE, version 1.1s (http://www.liv.ac.uk/∼jse/software.html), and the maximal catalytic rate was 2.2 × 104 per s.

Substrate specificity of AlgL.

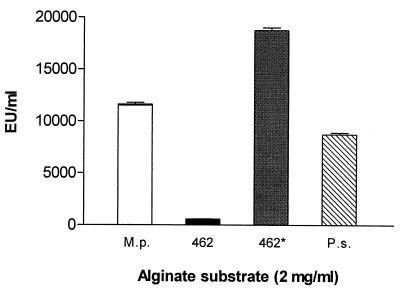

Alginate was isolated from P. syringae FF5(pPSR12) and P. aeruginosa FRD462 using established methods (20) and deacetylated as described previously (8). The substrate specificity of AlgL from P. syringae was evaluated using sodium alginate from M. pyrifera, polymannuronate (polyM) alginate from P. aeruginosa FRD462 before and after deacetylation, and alginate from P. syringae FF5(pPSR12). AlgL degraded deacetylated polyM alginate more efficiently than the other substrates, indicating a preference for polyM and suggesting that acetylation interferes with lyase activity (Fig. 2). Furthermore, AlgL from P. syringae degraded its own alginate, which may indicate a role for AlgL in the biosynthesis of alginate or dissemination of the bacteria when they are exposed to conditions unsuitable for survival and growth (3).

FIG. 2.

Substrate specificity of alginate lyase. The lyase activity of extracts obtained after temperature shock was evaluated in enzyme reaction buffer (30 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0) at 37°C for 2 min using the following substrates at 2 mg/ml: sodium alginate from M. pyrifera (M.p.); polymannuronic acid (polyM) from P. aeruginosa FRD462 (462); deacetylated polyM (462*); and alginate isolated from P. syringae pv. syringae FF5(pPSR12) (P.s.). The data represent the mean ± the standard deviation (n = 4).

Alginate plays an important role in the virulence of both P. syringae and P. aeruginosa, and algL mutants of both species produce less alginate than wild-type strains (18, 21). The lyases from both pseudomonads degrade their own alginate, which is consistent with a role in cleaving preformed alginate and/or in determining the length of the alginate polymer. Elucidating the role of AlgL will provide a better understanding of alginate biosynthesis in both organisms and the diseases they cause in plant and animal hosts.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence for algL from P. syringae was deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF222020.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants AI 36325 (N.L.S.) and AI 43311 (C.L.B.) from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Rick Hatch and Sally Scott for technical assistance and Alejandro Peñaloza-Vázquez and Lisa Keith for advice and criticism.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baltimore R S, Shedd D G. The role of complement in the opsonization of mucoid and non-mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Pediatr Res. 1983;17:952–958. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198312000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barettino D, Feigenbutz M, Valcárcel R, Stunnenberg H G. Improved method for PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:541–542. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.3.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd A, Chakrabarty A M. Role of alginate lyase in cell detachment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2355–2359. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2355-2359.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chitnis C E, Ohman D E. Genetic analysis of the alginate biosynthetic gene cluster of Pseudomonas aeruginosa shows evidence for an operonic structure. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:583–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eftekhar F, Schiller N L. Partial purification and characterization of a mannuronan-specific alginate lyase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Curr Microbiol. 1994;29:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ertesvåg H, Erlien F, Skjåk-Bræk G, Rehm B H A, Valla S. Biochemical properties and substrate specificities of a recombinantly produced Azotobacter vinelandii alginate lyase. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3779–3784. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3779-3784.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fett W F, Osman S F, Fishman M L, Siebles T S., III Alginate production by plant-pathogenic pseudomonads. J Bacteriol. 1986;52:466–473. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.3.466-473.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franklin M J, Chitnis C E, Gacesa P, Sonesson A, White D C, Ohman D E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgG is a polymer level alginate C5-mannuronan epimerase. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1821–1830. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1821-1830.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gacesa P. Bacterial alginate biosynthesis—recent progress and future prospects. Microbiology. 1998;144:1133–1143. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-5-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gacesa P. Enzymic degradation of alginates. Int J Biochem. 1992;24:545–552. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(92)90325-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross M, Rudolf K. Demonstration of levan and alginate in bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris) infected by Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola. J Phytopathol. 1987;120:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haraguchi K, Kodama T. Purification and properties of poly(β-D-mannuronate)lyase from Azotobacter chroococcum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;44:576–581. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatch R A, Schiller N L. Alginate lyase promotes diffusion of aminoglycosides through the extracellular polysaccharide of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:974–977. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.4.974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keith L M W, Bender C L. AlgT (ς22) controls alginate production and tolerance to environmental stress in Pseudomonas syringae. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7167–7184. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.23.7176-7184.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy L, McDowell K, Sutherland I W. Alginases from Azotobacter species. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:2465–2471. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kidambi S P, Sundin G W, Palmer D A, Chakrabarty A M, Bender C L. Copper as a signal for alginate synthesis in Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2172–2179. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2172-2179.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King E O, Ward M K, Raney D E. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescein. J Lab Clin Med. 1954;44:301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monday S R, Schiller N L. Alginate synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the role of AlgL (alginate lyase) and AlgX. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:625–632. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.625-632.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakagawa A, Ozaki T, Chubachi K, Hosoyama T, Okubo T, Iyobe S, Suzuki T. An effective method for isolating alginate lyase-producing Bacillus sp. ATB-1015 strain and purification and characterization of the lyase. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;84:328–335. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohman D E, Chakrabarty A M. Genetic mapping of chromosomal determinants for the production of the exopolysaccharide alginate in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolate. Infect Immun. 1981;33:142–148. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.1.142-148.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peñaloza-Vázquez A, Kidambi S P, Chakrabarty A M, Bender C L. Characterization of the alginate biosynthetic gene cluster in Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4464–4472. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4464-4472.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rudolph K W E, Gross M, Ebrahim-Nesbat F, Nollenburg M, Zomorodian A, Wydra K, Neugebauer M, Hettwer U, El-Shouny W, Sonnenberg B, Klement Z. The role of extracellular polysaccharide as virulence factors for phytopathogenic pseudomonads and xanthomonads. In: Kado C I, Crosa J H, editors. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1994. pp. 357–448. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomassen M J, Demko C A, Doershuk C F. Cystic fibrosis: a review of pulmonary infections and interventions. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1987;3:334–351. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950030510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson J D, Gibson T J, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins D G. The Clustal_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weissbach A, Hurwitz J. The formation of 2-keto-3-deoxyheptonic acid in extracts of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:705–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong T Y, Preston L A, Schiller N L. Alginate lyase—review of major sources and enzyme characteristics, structure-function analysis, biological roles and applications. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:289–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoon H J, Mikami B, Hashimoto W, Murata K. Crystal structure of alginate lyase A1-III from Sphingomonas species A1 at 1.78Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:505–514. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu J, Peñaloza-Vázquez A, Chakrabarty A M, Bender C L. Involvement of the exopolysaccharide alginate in the virulence and epiphytic fitness of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:712–720. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]