Abstract

Urinary tract infection (UTI) accounts for a significant morbidity and mortality across the world and is a leading cause for antibiotic prescriptions in the community especially in developing countries. Empirical choice of antibiotics for treatment of UTI is often discordant with the drug susceptibility of the etiologic agent. This study aimed to estimate the prevalence of community-acquired UTI caused by antibiotic resistant organisms. This was a cross-sectional study where urine samples were prospectively collected from 4,500 patients at the icddr,b diagnostic clinic in Dhaka, Bangladesh during 2016–2018. Urine samples were analyzed by standard culture method and the isolated bacteria were tested for antibiotic susceptibility by using disc diffusion method and VITEK-2. Descriptive statistics were used to estimate the prevalence of community acquired UTI (CA-UTI) by different age groups, sex, and etiology of infection. Relationship between the etiology of CA-UTI and age and sex of patients was analyzed using binary logistic regression analysis. Seasonal trends in the prevalence of CA-UTI, multi-drug resistant (MDR) pathogens and MDR Escherichia coli were also analyzed. Around 81% of patients were adults (≥18y). Of 3,200 (71%) urine samples with bacterial growth, 920 (29%) had a bacterial count of ≥1.0x105 CFU/ml indicating UTI. Women were more likely to have UTI compared to males (OR: 1.48, CI: 1.24–1.76). E. coli (51.6%) was the predominant causative pathogen followed by Streptococcus spp. (15.7%), Klebsiella spp. (12.1%), Enterococcus spp. (6.4%), Pseudomonas spp. (4.4%), coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp. (2.0%), and other pathogens (7.8%). Both E. coli and Klebsiella spp. were predominantly resistant to penicillin (85%, 95%, respectively) followed by macrolide (70%, 76%), third-generation cephalosporins (69%, 58%), fluoroquinolones (69%, 53%) and carbapenem (5%, 9%). Around 65% of patients tested positive for multi-drug resistant (MDR) uropathogens. A higher number of male patients tested positive for MDR pathogens compared to the female patients (p = 0.015). Overall, 71% of Gram-negative and 46% of Gram-positive bacteria were MDR. The burden of community-acquired UTI caused by MDR organisms was high among the study population. The findings of the study will guide clinicians to be more selective about their antibiotic choice for empirical treatment of UTI and alleviate misuse/overuse of antibiotics in the community.

Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) in both community and hospital settings are estimated to affect around 405 million people globally and nearly 0.23 million people died of UTIs, contributing to 5.2 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in 2019 [1]. Treatment of UTI begins empirically often with different broad-spectrum antibiotics [2]. The incidence of UTIs caused by multidrug-resistant uropathogens has been increasing at an alarming rate worldwide. Such common infections can turn into life-threatening illnesses, especially in developing countries [3, 4]. The frequency, spectrum, and antibiotic resistance in uropathogens differ according to geographical locations and time, which necessitates a thorough understanding of the epidemiology of community-acquired UTIs (CA-UTIs) [5].

The predominant organism causing both complicated and uncomplicated UTI is uropathogenic Escherichia coli followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis, Proteus mirabilis, and group B Streptococcus (GBS) [6]. Further, multi-drug resistant E. coli and K. pneumoniae are increasingly recognized to cause both CA-UTIs and hospital-acquired UTIs [7, 8]. Because of these two pathogens, empirical treatment for acute pyelonephritis frequently involves a third-generation cephalosporin [9]. However, inappropriate use of antibiotics is very common in the management of CA-UTI. In developing countries, the scenario is debilitating as a significant proportion of UTI patients purchase antibiotics directly from community pharmacies without prescription or any expert consultation [10, 11]. Consequently, common antibiotics become ineffective. Although UTI can occur in any age and sex groups, female children, women in their reproductive age, and older women are more vulnerable to infections [12].

UTI is a significant public health problem in Bangladesh, which accounts for considerable morbidity [13], health care cost [14] due to frequent treatment failure, and recurrent infections. UTI is also one of the main reasons for misuse of antibiotics in the community leading to the escalating burden of antimicrobial resistance [11]. A study carried out in 2012 among 443 suspected UTI patients in a regional medical college hospital in Bangladesh showed that 43% of patients had significant bacterial growth of uropathogens in their urine samples [15]. A recent study has shown that more than 75% of E. coli causing UTI are resistant to third-generation cephalosporin [16]. Existing reports are based on either a small sample size, targeting only a specific population or age group, analysis of retrospective data from hospital registry, or characterization of convenience samples of bacterial isolates obtained from urine samples of UTI patients [17, 18]. The proportion of multi-drug resistant uropathogens is likely to have increased over time. There is no large-scale prospective survey of UTIs in Bangladesh that can provide an up-to-date information on the burden of infections in the community. Continuous monitoring of the etiology of infections and antibiotic resistance pattern is essential not only for selecting appropriate antibiotics for empirical therapy but also for reducing the overuse/misuse of antibiotics. We carried out a community-based study to investigate the etiologies of UTI along with antibiotic resistance profiles for 2 years in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Methods

Ethical approval

All participants provided written informed consent before taking part in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents/guardians of the minors (<16 years of age) included in this study. The research team explained the background and objectives of the study clearly to the participants. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of icddr,b (protocol number: PR 16071).

Study design

This study is a cross-sectional survey of patients from communities who visited the clinical diagnostic center of the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) from 1st September 2016 to 30th November 2018. The icddr,b clinical diagnostic center serves as reference laboratories for clinical diagnostic analysis of human diseases cohorts and control subjects. Approximately 1500 patients and individuals avail diagnostic services each day from the diagnostic outpatient department. The diagnostic laboratories are the only accredited laboratories under ISO15189 (quality) and ISO15190 (safety) in Bangladesh for as many as 160 different tests and parameters. The diagnostic center only offers on-payment clinical diagnostic services and does not provide any consultancy services to the patient. During the study period, patient’s consents were taken every day from 9 am to 5 pm except for the weekends and government holidays. Study physicians approached only those patients at the diagnostic center who ordered for urine culture and sensitivity analysis and requested for their willingness to allow the study team to use culture-sensitivity results of their urine sample and use the resulting bacterial isolates for further characterization. In Bangladesh, it is not required to show physician’s order to the diagnostic clinics for urine culture and sensitivity test and patients can order for the test by themselves. We did not assess whether they had any urinary tract complaints or had any symptoms of UTI but we used the following exclusion criteria for enrolment of the patients: 1) patients having any medical or surgical device in their bodies (e.g., catheter, cannula) 2) patients having renal stone 3) patients admitted to hospital. Enrolled patients were segregated into three age groups: adults (≥18y), adolescents (11-17y) and children (0-10y).

Sample collection and processing

Clean catch midstream urine was collected in a sterile urine container by the patient or by the caregiver of the patient (in case of children). Samples from the consented patients were labeled with a green color sticker containing our study name for tracking. Urine culture was done in the clinical microbiology lab of icddr,b following standard procedure within 1 h of collection [19]. Briefly, a loopful (~10μl) of urine samples were streaked on MacConkey agar (Oxoid Ltd., UK) and blood agar (Oxoid Ltd., UK) by a semi-quantitative method using a calibrated loop. Plates were incubated at 35°C aerobically and examined at 18–24 hours and they were further incubated for another 24 hours before a negative report was issued. Cultures were quantitated, and ‘significant’ bacteriuria was defined as a case of UTI in specimen containing bacterial species ≥1.0x105 CFU/ml of urine according to the standard guideline [20]. Patients with non-significant bacteriuria (<1.0x105 CFU/ml) were excluded from further analysis.

Identification of bacterial species

Isolates obtained from 1st September 2016 to 17th December 2017 were identified based on Gram’s stain reaction, culture characteristics and biochemical properties as described earlier [21], while the isolates obtained from 18th December 2017 to 30th November 2018 were identified using VITEK-2 system.

Antibiotic susceptibility tests

Antibiotic susceptibility testing of uropathogens isolated during the period from 1st September 2016 to 17th December 2017 was performed by the disk diffusion method following the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines using commercially available antibiotic disks (Oxoid Ltd., UK) [22]. Susceptibility testing for isolates obtained between 18th December 2017 to 30th November 2018 was done with VITEK 2 system. Antibiotic susceptibility tests were performed against 37 commonly prescribed antibiotics from 13 different classes of which aminoglycoside (gentamycin 10μg), macrolide (azithromycin 15μg), cephalosporins (ceftriaxone 30 μg; cefotaxime 30μg; ceftazidime 30μg; cefepime 30μg; cefixime 5μg), penicillin (ampicillin 10μg), penicillin/beta lactamase inhibitor combination(piperacillin-tazobactam 110μg), phenicols (chloramphenicol 30μg), tetracycline (tetracycline 30 μg), linezolid (linezolid 30μg), (fluoro)quinolone (nalidixic acid 30μg; ciprofloxacin 5μg), carbapenem (imipenem 10μg, meropenem, 10μg), nitrofurans (nitrofurantoin 300μg), glycylcyclines (vancomycin 30μg) and sulfonamides (sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim 25μg) were tested against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. In addition, polymyxin (polymyxin-B 300μg) and glycopeptide (vancomycin 30μg) antibiotics were tested only against Gram-negative and Gram-positive organisms, respectively. Isolates were categorized as sensitive, intermediate, or resistant according to the CLSI guideline. All third-generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli isolates were tested for ESBL production by combination disk diffusion test as described by CLSI using cefotaxime (CTX 30 μg), ceftazidime (CAZ, 30 μg) alone and in combination with clavulanic acid (CLA, 10 μg) [22]. Isolates were considered as ESBL-producer if the inhibition zone diameter was 5 mm larger with CLA than without [22]. If an organism was resistant to at least one agent in three or more classes of antibiotics, it was categorized as multidrug resistant (MDR) [23]. All MDR E. coli isolates were subcultured on fresh MacConkey plates and isolated colonies were stored at -80°C for further analysis.

Data analysis

We entered data into SPSS 20.0 (IBM Inc., Chicago, USA). Data cleaning, statistical analyses, and data visualization were done in Stata 13.0 (College Station, Texas, USA) and MS Office Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Washington, USA). Descriptive statistics including frequency distribution, percentage, and cross-tabulation were done among different age groups, sex, and etiology of infection. Percent of resistance to different antibiotics and resistance to multiple antibiotics in each organism was determined. Data were analyzed to determine the association between the proportion of samples that tested positive for MDR, non-MDR, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant, and carbapenem-resistant organisms, with age and sex by Chi-square test and Fisher exact test where applicable. Binary logistic regression was done by considering a sample positive for MDR as a dependent variable and age, sex as independent variables. Seasonal trends in the prevalence of CA-UTI, MDR pathogens, MDR, and non-MDR E. coli were analyzed to see the changing patterns of infection over two years (September 2016-November 2018). Statistical significance was determined at alpha = 0.05 for all tests.

Results

Prevalence of community acquired UTIs

During the period from September 2016 to November 2018, around 39,000 patients visited the icddr,b diagnostic center in Dhaka for doing culture and sensitivity analysis of their urine samples. In this study we enrolled 4,500 patients of which 3,643 (81%) were adults and 3,263 (73%) were females. Of these urine samples, 3,200 (71%) tested positive for microbial growth on culture plates, of which 920 (29%) had a significant bacterial count (≥1.0x105 CFU/ml of urine), defined as cases of UTI (Table 1). According to this criterion, the prevalence of CA-UTI cases among samples tested was 20% (920 of 4,500). The prevalence of CA-UTI was significantly higher among adult patients compared to adolescents and children (OR: 1.86, CI: 1.48–2.34) (Table 2). The prevalence of CA-UTI was also significantly higher among female patients (OR: 1.48, CI: 1.24–1.76) (Table 2). However, age-adjusted female patients and sex-adjusted age showed a lower risk of CA-UTI than the crude rate (Table 2).

Table 1. Characteristics of patients according to their age, sex and urine culture status.

| Covariates | Male (N = 1,237) n (%) | Female (N = 3,263) n (%) | Total (N = 4,500) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | |||

| Adult (18 & above) | 895 (72) | 2,748 (84) | 3,643 (81) |

| Adolescent (11–17) | 48 (4) | 95 (3) | 143 (3) |

| Child (0–10) | 294 (24) | 420 (13) | 714 (16) |

| Growth status | |||

| Growth positive | 747 (60) | 2,453 (75) | 3,200 (71) |

| Significant growth (≥105 CFU/ml of urine) | 199 (27) | 721 (29) | 920 (29) |

| Insignificant (<105 CFU/ml of urine) | 548 (73) | 1,732 (71) | 2,280 (71) |

| No growth | 477 (39) | 720 (22) | 1,197 (27) |

| Collection Contamination (≥ 3 organisms) | 13 (1) | 90 (3) | 103 (2) |

Table 2. Prevalence of community-acquired UTI among patients according to different age and sex groups.

| Characteristics | No (%) of UTI patients | Age (Mean±SD) | COR (CI) | AOR (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Adult (n = 3,643) | 808 (22) | 45.96±16.11 | 1.86 (1.48,2.34) | 1.76 (1.40,2.22) |

| Adolescent (n = 143) | 17 (12) | 14.33±4.56 | 0.88 (0.51,1.52) | 0.86 (0.49, 1.49) |

| Child (n = 714) | 95 (13) | 4.70±5.25 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (n = 1,237) | 199 (16) | 37.00±24.43 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female (n = 3,263) | 721 (22) | 38.95±20.18 | 1.48 (1.24,1.76) | 1.39 (1.17, 1.66) |

COR, crude odds ratios; AOR, adjusted odds ratios, CI, confidence intervals, SD, standard deviation

Etiologies of CA-UTI

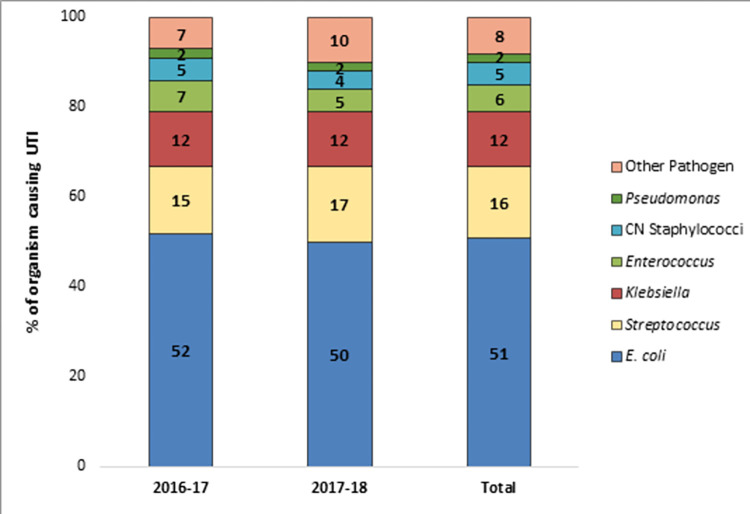

Culture of urine samples from 920 patients yielded significant growth of uropathogens including 849 (92%) monomicrobial (single bacterial species) and 71 (8%) polymicrobial (pair of two different bacterial species) growths. A total of 991 [849+ (71*2)] isolates were obtained from 920 patients of which 989 were bacterial isolates and 2 were identified as Candida spp. Among bacterial isolates, E. coli was the predominant (51.6%), followed by Streptococcus spp. (15.7%), Klebsiella spp. (12.1%), Enterococcus spp. (6.4%), Pseudomonas spp. (4.4%), coagulase negative Staphylococcus spp. (2.0%), Enterobacter spp. (1.8%), Proteus spp. (1.6%), Acinetobacter spp. (1.0%), Staphylococcus saprophyticus (1.1%), Staphylococcus aureus (0.6%), Corynebacterium spp. (0.3%), Serratia spp. (0.3%), and Sphingomonas paucimobilis (0.3%). A significant proportion of Streptococcus spp. and Enterococcus spp. were Streptococcus agalactiae (52%), and Enterococcus faecalis (59%), respectively. Due to some limitations of conventional culture-based methods in identifying organisms at species level we report the prevalence of some organisms at genus level. Distribution of isolates over two years showed almost similar trends with E. coli being the predominant organism in year 1 (52%) and year 2 (50%), followed by Streptococcus spp. (15%, 17%, respectively), Klebsiella spp. (12%, 12%), Enterococcus spp. (7%, 5%), coagulase negative Staphylococcus spp. (5%, 4%), Pseudomonas spp. (2%, 2%), and other pathogens (7%, 10%) (Fig 1). Of 71 polymicrobial infections, 39 (55%) tested positive for only Gram-negative bacteria, 17 (24%) tested positive for only Gram-positive bacteria and 15 (21%) tested positive for a mix of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The predominant pair of organisms (13 of 71) included lactose fermenting and non-fermenting E. coli followed by a pair of E. coli and Klebsiella spp.

Fig 1. Prevalence of major bacterial pathogens causing community-acquired UTI among patients from 2016 to 2018.

Antibiotic resistance patterns of uropathogens

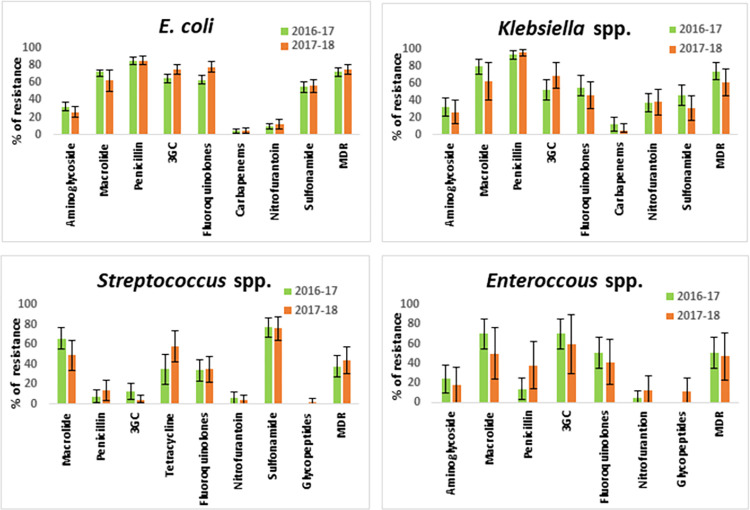

Among Gram-negative bacteria, E. coli and Klebsiella spp. were resistant to different classes of antibiotics with the highest rate of resistance to penicillin (85%, 95%, respectively) followed by macrolide (70%, 76%), third-generation cephalosporins (69%, 58%), fluoroquinolone (69%, 53%) and sulfonamide (56%, 41%). The difference in the prevalence of resistance in E. coli and Klebsiella spp. was significant for several antibiotics including third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, nitrofurantoin, and sulphonamide (Fig 2). For both E. coli and Klebsiella spp. no significant variation in resistance frequency was observed between the two years (Fig 2). Carbapenem resistance was the least prevalent in both E. coli (5%) and Klebsiella spp. (9%) (Fig 2). Overall, 454 (71%) Gram-negative isolates were multidrug-resistant and E. coli and Klebsiella spp. were the predominant with a prevalence of 74% and 68%, respectively. Of 510 E. coli isolates, 350 (69%) were third-generation cephalosporins resistant (3GCr) and 233 (67%) of 3GCr E. coli were positive for ESBL.

Fig 2. Antibiotic resistance profiles of four major pathogens causing community-acquired UTI from 2016 to 2018.

Only those antibiotics were included in the analysis for which the minimum number of isolates tested was 10.

Of 260 Gram-positive bacterial isolates, antibiotic susceptibility test results were available for 194 (75%) isolates. Among the prevalent Gram-positive organisms, both Streptococcus spp. and Enterococcus spp. were predominantly resistant to macrolide (59%, 65%, respectively). Only a small proportion (9%) of Streptococcus spp. was resistant to third-generation cephalosporin (Fig 2). Overall, 46% of Gram-positive isolates were identified as MDR, Streptococcus spp. and Enterococcus spp. were predominant with a prevalence of 37% and 35%, respectively.

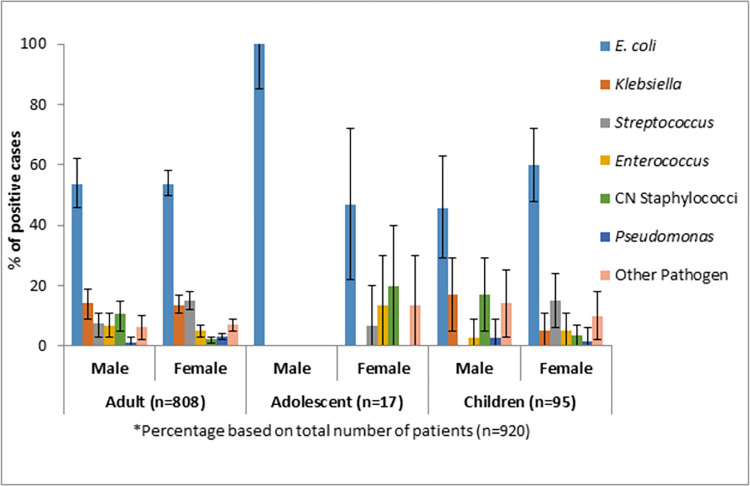

Distribution of uropathogens according to age and sex

A significantly higher number of female patients (n = 721) had an infection with both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (p<001). Male to female ratio among laboratory-confirmed CA-UTI patients were 1:3 (age-adjusted odds ratio: 1.39, CI: 1.17–1.66). E. coli was the predominant uropathogen among adult female patients followed by Streptococcus spp., Klebsiella spp., and Enterococcus spp. We observed similar trends among adult male patients except that coagulase negative Staphylococcus spp. was more prevalent than Enterococcus spp. (Fig 3).

Fig 3. Distribution of the prevalence of major pathogens causing CA-UTI among patients by age and sex.

Distribution of MDR uropathogens according to age and sex

The prevalence of MDR-UTIs did not differ significantly in patients of different age groups. However, a significantly higher proportion of male patients (73%) tested positive for MDR organisms compared to their female counterparts (63%) (p = 0.015). The difference was prominent among child patients. Male children had 72% (CI: 22%-90%) higher odds of being infected with MDR organisms compared to their female counterparts (Table 3). However, the difference was not statistically significant among patients positive for 3GCr and carbapenem resistant organisms at any age group, although higher proportions of male adult and child patients were positive for 3GCr organisms compared to their female counterparts (Table 4).

Table 3. Prevalence of MDR community-acquired UTI among patients according to different age and sex groups.

| Covariates (n = 892)* | MDR (n = 575) | Age (yrs) (Mean±SD) | Non-MDR (n = 317) | Age (yrs) (Mean±SD) | OR (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult (n = 781) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Male (n = 157) | 109 (69) | 57.11±13.68 | 48 (31) | 51.79±17.75 | 1 |

| Female (n = 624) | 393 (63) | 51.99±15.33 | 231 (37) | 46.25±16.37 | 0.75 (0.51, 1.09) |

| Adolescent (n = 17) | |||||

| Male (n = 2) | 1 (50) | - | 1 (50) | - | 1 |

| Female (n = 15) | 9 (60) | 13.18±2.41 | 6 (40) | 14.33±3.32 | 1.50 (0.07, 28.89) |

| Child (n = 94) | |||||

| Male (n = 35) | 29 (83) | 2.66±2.66 | 6 (17) | 1.42±1.24 | 1 |

| Female (n = 59) | 34 (58) | 4.44±3.07 | 25 (42) | 4.35±3.03 | 0.28 (0.10, 0.78) |

*Antibiotic susceptibility results were available for 892 out of 920 patients

Table 4. Prevalence of 3GCr and carbapenem-resistant pathogens among patients with community-acquired UTI.

| Covariates* | 3GCr n (%) | Age (yrs) (Mean±SD) | OR (CI) | Covariates* | CarbR n (%) | Age (yrs) (Mean±SD) | OR (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult (n = 521) | Adult (n = 521) | ||||||

| Male (n = 107) | 77 (72) | 58.88±12.97 | 1 | Male (n = 107) | 5 (5) | 62.40±7.64 | 1 |

| Female (n = 414) | 271 (65) | 53.27±14.17 | 0.74 (0.46–1.18) | Female (n = 414) | 20 (5) | 53.15±16.58 | 1.04 (0.38–2.83) |

| Adolescent (n = 8) | Adolescent (n = 8) | ||||||

| Male (n = 2) | 1 (50) | - | 1 | Male (n = 2) | 1 (50) | - | - |

| Female (n = 6) | 4 (67) | 14.00±3.46 | 2 (0.07–51.59) | Female (n = 6) | 0 | - | - |

| Child (n = 58) | Child (n = 58) | ||||||

| Male (n = 21) | 15 (71) | 2.00±1.85 | 1 | Male (n = 21) | 2 (10) | 1.23±0.86 | 1 |

| Female (n = 37) | 24 (65) | 4.67±3.03 | 0.74 (0.23–2.36) | Female (n = 37) | 2 (5) | 8±1.41 | 0.54 (0.07–4.17) |

CarbR, carbapenem resistant; n, number; 3GCr, 3rd generation cephalosporin resistant

*One isolate represents one patient. A total of 587 Gram-negative isolates were tested for susceptibility against third-generation cephalosporin and carbapenem antibiotics.

Temporal distribution of antibiotic-resistant uropathogens among patients

We analyzed the distribution of antibiotic resistance in 991 isolates over two years to find the trends across years. There were no significant fluctuations in the prevalence of resistance to any particular antibiotic over the years among major uropathogens such as E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Streptococcus spp., and Enterococcus spp. (Fig 2). Overall, more than 50% of all Gram-negative isolates (range: 53% to 95%) were found consistently resistant to penicillin, third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones. Prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli has significantly increased over the years (p<0.05).

Discussion

Increased resistance to multiple antibiotics among pathogens causing CA-UTI leads to frequent treatment failure and complications. Drug-resistant CA-UTI has become a major global health problem, especially in developing countries like Bangladesh. However, longitudinal surveillance of CA-UTI estimating the burden of infection, etiology and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of uropathogens in Bangladesh is largely missing except for a few small observational studies among specific population groups such as pregnant women, children, and hospitalized patients [15, 17, 24, 25]. We conducted this study to fill this critical knowledge gap. Among 4,500 patients enrolled in this study during the 2 years, the prevalence of laboratory-confirmed CA-UTI cases (as defined by CFU ≥1.0x105 CFU/ml from urine culture) was 20% with women bearing the greater burden (78%), similar to most studies of CA-UTI [26].

Although the majority of UTI cases were caused by a single pathogen, we found a small proportion of patients had polymicrobial growth in their urine culture mostly E. coli coupled with lactose non-fermenting E. coli or Klebsiella spp. In general, polymicrobial infections are less common in young, healthy, sexually active females [27]. In our study, we found that polymicrobial cases were predominant among female adult patients (52.3 ± 15 years), and there was no significant difference in prevalence among different age groups. Studies on polymicrobial cases of UTI in Bangladesh are limited, one study reported that 5% patient had polymicrobial growth in urine samples [15]. It is more likely that polymicrobial infections often go untreated or treated with inappropriate antibiotics leading to the development of antibiotic resistance in uropathogens [28].

Among monomicrobial cases, we found that Streptococcus spp. was the most prevalent cause of CA-UTI after E. coli, which is in agreement with a previous study among adult women in Dhaka slums [29]. However, two studies carried out with patients attending tertiary level hospitals outside of Dhaka (in Rajshahi and Mymensingh), reported that Staphylococcus saprophyticus was the second leading cause of UTI after E. coli [15, 18] while another study (in Comilla) reported Klebsiella pneumoniae as the second leading cause [30]. There might be some geographical variations in the etiology of UTI in Bangladesh, which might also be dependent on the age, sex, sexual activity (for female), clinical features and demographic characteristics of patients. However, irrespective of all variations among patients, E. coli appears to be the most common cause of UTI, and thus combating E. coli infections would largely reduce the burden of CA-UTI in the community. Among all Streptococcus spp. cases S. agalactiae or Group B Streptococcus (GBS) accounted for 52% (n = 80) and around 9% of the total number of patients with UTI; 92% (n = 74) of women were infected with GBS. In a previous study among pregnant women in rural Bangladesh, only a small proportion of (5.3%) patients were infected with GBS [24].

Around 65% of the patients in our study tested positive for an MDR pathogen comprising both Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms, which is higher than the report from a neighboring country Nepal [31, 32]. There is scarcity of data on the overall prevalence of MDR pathogens in CA-UTI in Bangladesh and neighboring countries. The majority of studies focused on resistance patterns of the predominant bacterial pathogen causing UTI, such as E. coli or ESBL-producing E. coli. Among neighboring countries, a study in Kathmandu, Nepal reported that 41% of bacterial pathogens from UTI cases were MDR [32]. A similar study from Alighar, India reported that 42% of uropathogens were ESBL-producing, while another study from Pakistan showed that 66% of uropathogens were ESBL-producing [33]. Studies from India and Pakistan reported the occurrence of MDR E. coli as 43% and 59%, respectively [31, 34, 35]. In this study, we found that 74% of E. coli isolates were MDR and 69% of isolates were resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, which is higher than the prevalence of MDR E. coli (58%) reported earlier from Bangladesh [29]. Overall, 50% of all isolates were consistently resistant to macrolide, and penicillin, and 80% of isolates were sensitive to carbapenem, glycopeptides and rifampicin. In the case of E. coli, a significant proportion (70%) was sensitive to aminoglycosides, nitrofurantoin and carbapenem, which corroborates with data from other countries [36–40].

We found that male patients were more likely to be infected with MDR organisms than female patients. Similarly, prevalence of 3GCr and carbapenem-resistant organisms was higher among adult male compared to adult females. This finding correlates with the results of a large study conducted in Portugal where the prevalence of MDR uropathogens was higher in men than in women (35% vs. 22%) [41]. However, among adolescents and children, the difference in prevalence was not statistically significant. One of the reasons for the higher prevalence of MDR organisms among adult male in our study could be the older age as we found mean ages of the male adults with 3GCr and carbapenem-resistant infections were 58.9 (±13.0) and 62.4 (±7.6) years, respectively which is higher than the mean age for female adults with 3GCr (53.3±14.2) and carbapenem (53.1±16.6) resistant infections. Older males usually develop UTIs as a result of bladder outlet obstruction from prostate enlargement, which is often associated with a higher prevalence of resistance due to recurrence and prolonged antibiotic treatment with higher therapeutic doses [42, 43].

There were some limitations in our study. We carried out the surveillance among patients who came to icddr,b diagnostic facility to test their urine samples for culture and sensitivity analysis. A large proportion of patients receiving diagnostic services from icddr,b are the residents of Dhaka city and therefore the data may not be representative of the whole country. icddr,b diagnostic facility only provides clinical diagnostic services and does not offer any outpatient services and therefore, we could not estimate the proportion of patients with and without symptomatic infection. Nevertheless, our study provides a recent insight into the etiology of CA-UTI along with trends in antibiotic resistance among uropathogens over 2 years in a large sample size for the first time in Bangladesh.

Conclusions

The burden of CA-UTI caused by MDR pathogens is high among the study participants and there was no significant difference in prevalence and etiology of infection over two years. The findings of the study can serve as an evidence base for updating guidelines for improved management of CA-UTI in Bangladesh and other developing countries with similar settings. It also provides a basis to conduct epidemiologic studies to investigate risk factors for the acquisition of antibiotic-resistant CA-UTI.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of Dr. Progga Paromita and Dr. Refaya Noor for their support in enrolling patients during the first phase of the study. We are grateful for the invaluable assistance of all the patients participated in the project.

List of abbreviations

- UTI

Urinary tract infection

- CA-UTIs

community-acquired UTIs

- CLSI

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- ESBL

extended spectrum beta-lactamase

- MDR

multi-drug resistant

- 3GCr

third-generation cephalosporin-resistant

- icddr,b

International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant number: [R01AI116471] which was awarded to MAI. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Zeng Z, Zhan J, Zhang K, Chen H, Cheng S. Global, regional, and national burden of urinary tract infections from 1990 to 2019: an analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. World J Urol. 2022;40(3):755–63. doi: 10.1007/s00345-021-03913-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryce A, Hay AD, Lane IF, Thornton HV, Wootton M, Costelloe C. Global prevalence of antibiotic resistance in paediatric urinary tract infections caused by Escherichia coli and association with routine use of antibiotics in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2016;352:i939. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazzariol A, Bazaj A, Cornaglia G. Multi-drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria causing urinary tract infections: a review. J Chemother. 2017;29(sup1):2–9. doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2017.1380395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta A, Bansal N, Houston B. Metabolomics of urinary tract infection: a new uroscope in town. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2012;12(4):361–9. doi: 10.1586/erm.12.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tandogdu Z, Wagenlehner FM. Global epidemiology of urinary tract infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2016;29(1):73–9. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(5):269–84. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim YH, Yang EM, Kim CJ. Urinary tract infection caused by community-acquired extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing bacteria in infants. J Pediatr. 2017;93(3):260–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nai-Chia F, Hsin-Hang C, Chyi-Liang C, Liang-Shiou O, Tzou-Yien L, Ming-Han T, et al. Rise of community-onset urinary tract infection caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in children. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2014;47:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2013.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albaramki JH, Abdelghani T, Dalaeen A, Khdair Ahmad F, Alassaf A, Odeh R, et al. Urinary tract infection caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing bacteria: Risk factors and antibiotic resistance. Pediatr Int. 2019;61(11):1127–32. doi: 10.1111/ped.13911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leski TA, Taitt CR, Bangura U, Stockelman MG, Ansumana R, Cooper WH 3rd, et al. High prevalence of multidrug resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated from outpatient urine samples but not the hospital environment in Bo, Sierra Leone. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:167. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1495-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auta A, Hadi MA, Oga E, Adewuyi EO, Abdu-Aguye SN, Adeloye D, et al. Global access to antibiotics without prescription in community pharmacies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2019;78(1):8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minardi D, d’Anzeo G, Cantoro D, Conti A, Muzzonigro G. Urinary tract infections in women: etiology and treatment options. Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:333. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S11767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noor R, Munna MS. Emerging diseases in Bangladesh: Current Microbiological Research Perspective. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2015;27(2):49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tcmj.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahman MM, Zhang C, Swe KT, Rahman MS, Islam MR, Kamrujjaman M, et al. Disease-specific out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure in urban Bangladesh: A Bayesian analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0227565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haque R, Akter ML, Salam MA. Prevalence and susceptibility of uropathogens: a recent report from a teaching hospital in Bangladesh. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:416. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1408-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acherjya GK, Tarafder K, Ghose R, Islam DU, Ali M, Akhtar N, et al. Pattern of antimicrobial resistance to Escherichia coli among the urinary tract infection patients in Bangladesh. Am J Intern Med. 2018;6(5):132–7. doi: 10.11648/j.ajim.20180605.17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Majumder MI, Ahmed T, Hossain D, Begum SA. Bacteriology and antibiotic sensitivity patterns of urinary tract infections in a tertiary hospital in Bangladesh. Mymensingh Med J. 2014;23(1):99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parvin US, Hossain MA, Musa AK, Mahamud C, Islam MT, Haque N, et al. Pattern of aerobic bacteria with antimicrobial susceptibility causing community acquired urinary tract infection. Mymenshingh Med J. 2009;18(2):148–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray PR, Barron EJ, Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA, Yolken RH. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 8th ed. Washington DC: ASM Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, Rice JC, Schaeffer A, Hooton TM. Infectious diseases society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):643–54. doi: 10.1086/427507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isenberg HD. Essential procedures for clinical microbiology. Washington DC, ASM press,; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 27th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Wayne, PA, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee AC, Mullany LC, Koffi AK, Rafiqullah I, Khanam R, Folger LV, et al. Urinary tract infections in pregnancy in a rural population of Bangladesh: population-based prevalence, risk factors, etiology, and antibiotic resistance. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;20(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2665-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das R, Ahmed T, Saha H, Shahrin L, Afroze F, Shahid AS, et al. Clinical risk factors, bacterial aetiology, and outcome of urinary tract infection in children hospitalized with diarrhoea in Bangladesh. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(5):1018–24. doi: 10.1017/S0950268816002971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linhares I, Raposo T, Rodrigues A, Almeida A. Frequency and antimicrobial resistance patterns of bacteria implicated in community urinary tract infections: a ten-year surveillance study (2000–2009). BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13–19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kline KA, Lewis AL. Gram-positive uropathogens, polymicrobial urinary tract infection, and the emerging microbiota of the urinary tract. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4(2):10. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0012-2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Croxall G, Weston V, Joseph S, Manning G, Cheetham P, McNally A. Increased human pathogenic potential of Escherichia coli from polymicrobial urinary tract infections in comparison to isolates from monomicrobial culture samples. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60(Pt 1):102–9. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahman SR, Ahmed MF, Begum A. Occurrence of urinary tract infection in adolescent and adult women of shanty town in Dhaka city, Bangladesh. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2014;24(2):145–52. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v24i2.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majumder MMI, Ahmed T, Ahmed S, Khan AR, Saha CK. Antibiotic resistance in urinary tract infection in a tertiary care hospital in Bangladesh-A follow-up study. Med Today. 2019;31(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Awasthi TR, Pant ND, Dahal PR. Prevalence of multidrug resistant bacteria in causing community acquired urinary tract infection among the patients attending outpatient department of Seti zonal hospital, Dhangadi, Nepal. Nepal J Biotechnol. 2015;3(1):55–9. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baral P, Neupane S, Marasini BP, Ghimire KR, Lekhak B, Shrestha B. High prevalence of multidrug resistance in bacterial uropathogens from Kathmandu, Nepal. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:38. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sohail M, Khurshid M, Saleem HG, Javed H, Khan AA. Characteristics and antibiotic resistance of urinary tract pathogens isolated from Punjab, Pakistan. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2015;8(7):e19272. doi: 10.5812/jjm.19272v2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kulkarni SR, Peerapur BV, Sailesh KS. Isolation and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of Escherichia coli from urinary tract infections in a tertiary care hospital of north eastern Karnataka. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2017;8(2):176–80. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.210012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ali I, Rafaque Z, Ahmed S, Malik S, Dasti JI. Prevalence of multi-drug resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli in Potohar region of Pakistan. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2016;6(1):60–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang H, Kong H, Yu Y, Wu A, Duan Q, Jiang X, et al. Carbapenem susceptibilities of Gram-negative pathogens in intra-abdominal and urinary tract infections: updated report of SMART 2015 in China. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):493. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3405-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kabugo D, Kizito S, Ashok DD, Graham KA, Nabimba R, Namunana S, et al. Factors associated with community-acquired urinary tract infections among adults attending assessment centre, Mulago hospital Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16(4):1131–42. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v16i4.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dehbanipour R, Rastaghi S, Sedighi M, Maleki N, Faghri J. High prevalence of multidrug-resistance uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains, Isfahan, Iran. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2016;7(1):22–6. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.175020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maraki S, Mantadakis E, Michailidis L, Samonis G. Changing antibiotic susceptibilities of community-acquired uropathogens in Greece, 2005–2010. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2013;46(3):202–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2012.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tillekeratne LG, Vidanagama D, Tippalagama R, Lewkebandara R, Joyce M, Nicholson BP, et al. Extended-spectrum ß-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae as a common cause of urinary tract infections in Sri Lanka. Infect Chemother. 2016;48(3):160–5. doi: 10.3947/ic.2016.48.3.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Linhares I, Raposo T, Rodrigues A, Almeida A. Incidence and diversity of antimicrobial multidrug resistance profiles of uropathogenic bacteria. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:354084. doi: 10.1155/2015/354084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicolle LE. Complicated urinary tract infection in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(6):349–60. doi: 10.1155/2005/385768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lipsky BA. Urinary tract infections in men. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110(2):138–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-2-138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.