Abstract

Background

Pulmonary tuberculosis infection can manifest in different states, including subclinical tuberculosis. It is commonly defined as confirmed tuberculosis without the classic symptoms (commonly, persistent cough for ≥2 weeks). This narrow definition likely poses limitations for surveillance and control measures. The aims of the current study were to characterize the clinical presentation of tuberculosis; estimate the prevalence of subclinical tuberculosis among individuals with bacteriologically confirmed tuberculosis, using various definitions; and investigate risk factors for subclinical as opposed to clinical tuberculosis in a population-based survey.

Methods

We conducted a secondary analysis of data from a nationally representative tuberculosis prevalence survey from Zambia in 2013–2014, in which participants were screened for tuberculosis based on chest radiographic findings and symptoms. Tuberculosis was defined as culture-positive or GeneXpert MTB/RIF test–positive sputum. Risk factors for subclinical tuberculosis were assessed by means of multivariable logistic regression.

Results

Of 257 participants with confirmed tuberculosis, 104 (40.5%) were without cough persisting ≥2 weeks. Only 23 (22.1%) of these did not present with any other common symptoms. Those without cough persisting ≥2 weeks frequently reported other symptoms, particularly chest pain (46.2%) and weight loss (38.5%); 36 (34.6%) reported experiencing other symptoms persisting ≥4 weeks. Female subjects were more likely to report no cough persisting ≥2 weeks, as were relatively wealthier individuals.

Conclusions

The commonly used definition of subclinical tuberculosis includes a large proportion of individuals who have other tuberculosis-suggestive symptoms. Requiring cough ≥2 weeks for tuberculosis diagnosis likely misses many active tuberculosis infections and allows a large reservoir of likely transmissible tuberculosis to remain undetected.

Keywords: tuberculosis, subclinical, asymptomatic, screening, prevalence

The commonly used and narrow definition of subclinical tuberculosis is insensitive to a large reservoir of symptomatic active cases. We performed secondary analysis of 2013–2014 Zambia tuberculosis prevalence survey data to investigate the presentation of subclinical tuberculosis.

Infection with pulmonary tuberculosis and associated disease within any infected individual exist on a continuous spectrum. Models of human infection with pulmonary tuberculosis , however, have historically been simplified to 2 states: latent tuberculosis infection and active tuberculosis disease. Latent tuberculosis infection is a state in which the individual is infected with viable tuberculosis bacteria, but the infection is, for the time being, successfully suppressed by the host immune system. About 10% of these infections are expected to ever progress to active disease. Active tuberculosis disease is a state that reflects symptomatic disease in the host and can be detected by radiologic or microbiologic means. However, as further achievements in tuberculosis control are made and progress more commonly is represented by incremental gains, the adequacy of a simplified binary model of tuberculosis infection has been brought into question.

Control of tuberculosis is focused on detecting and treating cases of active tuberculosis disease, as these may result in disease and death and may be a source of transmission to others. In resource-constrained settings, where most of the global tuberculosis burden is found, clinical screening for a diagnostic investigation of active tuberculosis often relies on a simple symptom screen, namely, whether the patient has experienced cough persisting for ≥2 weeks. Less frequently, other symptoms—such as fever, weight loss, and chest pain—are used in the clinical screening. It is recognized, however, that active disease is not necessarily accompanied by the symptoms necessary to trigger a diagnostic investigation, should an individual with active disease present to clinic. These infections are referred to as subclinical tuberculosis and represent 1 of 4 proposed states to replace the binary paradigm including latent infection, incipient infection, subclinical disease, and active disease [1].

The definition for subclinical tuberculosis does not yet have consensus. One proposed definition, according to Drain et al [2], is “… disease due to viable [Mycobacterium] tuberculosis bacteria that does not cause clinical TB-related symptoms but causes other abnormalities that can be detected using existing radiologic or microbiologic assays.” Uncertainty arises when attempting to precisely define “clinical TB-related symptoms.” A common definition for subclinical tuberculosis, used by most national programs, is any case of tuberculosis without cough persisting for ≥2 weeks, irrespective of any other symptoms, based on the simple symptom screen for presumptive tuberculosis. Estimates of prevalence of subclinical tuberculosis across countries based on national tuberculosis prevalence surveys have used a negative symptom screen(typically based only on persistent cough) as the definition of scTB [3].

Persons with subclinical tuberculosis are much less likely to be tested for tuberculosis, making them a reservoir nearly invisible to passive surveillance/case detection. Even if these individuals do have interactions with the health system, for any reason, they are undetected because screening for presumptive tuberculosis is targeted to clinical tuberculosis. This raises the question of whether these cases matter to control and elimination programs, because a lack of symptoms has sometimes been assumed to correlate with a lack of infectiousness. Research in recent years, however, has brought this assumption into question. For example, Esmail et al [4] have proposed that transmission during the subclinical tuberculosis phase of infection may be facilitated by causes of chronic or acute cough, unrelated to tuberculosis, while capture of exhaled M. tuberculosis in face masks was not associated with cough frequency [5]. As such, subclinical tuberculosis represents a potentially significant barrier to control and elimination.

The current research is a secondary data analysis of the data collected in Zambia during a nationally representative tuberculosis prevalence survey, conducted in 2013–2014. Specifically, this study used data from the pool of participants with confirmed tuberculosis, to (1) characterize the presentation of tuberculosis and estimate the prevalence of subclinical tuberculosis among persons with confirmed tuberculosis using various subclinical tuberculosis definitions and (2) investigate risk factors for subclinical as opposed to clinical tuberculosis.

METHODS

Study Setting

Zambia (population in 2013 and 2014, respectively: 14 580 290 and 15 023 315 [6]) was among 22 countries selected by the World Health Organization Global Task Force on TB Impact Measurement as high priority for conducting a nationally representative prevalence survey [7, 8]. Based on this survey, nationwide tuberculosis prevalence was estimated in 2013–2014 at 455 per 100 000 population for all age groups [9]. Zambia’s tuberculosis surveillance strategy in 2013 consisted primarily of passive case detection. Estimates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence in Zambia in 2014 vary by source but range from 6.6% to 13% among adults [10, 11] with HIV coinfection in up to 67% of patients with confirmed tuberculosis [12, 13].

Data Source

The study data were sourced from a nationally representative tuberculosis prevalence survey conducted in 2013–2014 [9]. Sixty-six clusters were sampled with probability of selection proportional to cluster size, stratified by urban (40%) and rural (60%). All households within sampled clusters were visited, and de facto members aged ≥15 years were invited to attend a central survey site within the cluster. Of the 54 830 eligible individuals, 46 099 participated in screening for presumptive tuberculosis. Screening for tuberculosis in all 46 099 participants consisted of a chest radiograph read in the field by a medical officer and a symptom screen for the presence and duration of cough, chest pain, and fever. Participants with either abnormal chest radiographic findings or any of the above symptoms for ≥2 weeks were considered screen positive and further examined. All participants were offered an HIV test; 30 605 (68.4%) accepted and 30 584 (99.9%) were tested [11].

Those with a positive result after screening were subject to an in-depth examination of symptoms and invited to provide both on-the-spot and morning sputum samples; subsequently, 6154 (91.7%) submitted ≥1 sample. Both acid-fast bacilli smear and M. tuberculosis culture (mycobacteria growth indicator tube) tests were performed on all samples. Smear-positive cases and specimens from cases with culture indeterminate or with chest radiographic findings suggestive of tuberculosis after review by a panel of specialized radiologists were further evaluated using the GeneXpert MTB/RIF test for confirmation.

Analytic Data Set for Current Study

The current study primarily used data from all untreated tuberculosis cases from the Zambia prevalence survey, regardless of tuberculosis history. We defined a tuberculosis case as culture positive or Gene Xpert MTB/RIF test positive. A total of 257 participants met these criteria and were included as subjects in the analysis.

Definitions of Subclinical Tuberculosis

Two definitions of subclinical tuberculosis were used in this research (Table 1). In addition to absence of cough persisting for ≥2 weeks (definition 1), we added a definition based on the symptom screen recommended by the World Health Organization for ruling out tuberculosis disease in people living with HIV [14, 15]. It classifies as screen positive anyone who has cough, fever, night sweats, or weight loss of any duration, irrespective of any other symptoms (definition 2). The data set included presence and duration of these 4 symptoms, as well as chest pain. In the following analyses, all cases of tuberculosis were either regarded as meeting the definition for subclinical tuberculosis or were considered clinical (binary classification).

Table 1.

Definitions of Subclinical Tuberculosis

| Definition | Criteria | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Definition 1 | No cough persisting for ≥2 wk, irrespective of other symptoms | Complement to standard screening rule for tuberculosis used in most national tuberculosis programs |

| Definition 2 | No cough, fever, night sweats, or weight loss for any duration of time | Complement to WHO screening rule for tuberculosis in people living with HIV |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; WHO, World Health Organization.

Analytic Methods

The prevalence of subclinical tuberculosis among subjects was reported and their clinical presentation described. Descriptions of clinical presentation included symptom combinations and duration of longest symptom not captured by subclinical tuberculosis definitions. Logistic regression was used to assess age, sex, geography (urban vs rural), socioeconomic status (SES), and HIV status of subjects as potential determinants of subclinical versus clinical tuberculosis. Terms without statistically significant associations were dropped from the model through a backward selection process to arrive at the final model. SES was based on a household wealth index score obtained during the survey and categorized in tertiles. To provide evidence in relation to a hypothesis made in the discussion, Spearman rank correlation was used to assess the presence of a relationship between SES category and duration of longest symptom among subjects screening positive on the symptom screen.

RESULTS

Sample Description

Characteristics of the 257 subjects identified in the survey are outlined in the final column of Table 2. Just more than half (56.4%) were male. Their average age was 42.1 years, and 54.5% lived in urban areas; 14% of subjects tested positive for HIV, and 49.0% declined testing for HIV.

Table 2.

Sample Description, Clinical Characteristics, and Prevalence, Stratified by Definitions of Subclinical Tuberculosis

| Subjects, No. (%)a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subclinical Tuberculosis by Definition 1 | Subclinical Tuberculosis by Definition 2 | ||||||

| Characteristics and Symptoms | Yes (n = 104) | No (n = 153) | P-Value | Yes (n = 32) | No (n = 225) | P-Value | Overall (n = 257) |

| Female sex | 57 (54.8) | 55 (35.9) | .004 | 16 (50.0) | 96 (42.7) | .55 | 112 (43.6) |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 41.0 (31.0–52.0) | 39.0 (30.0–51.0) | 40.0 (32.0–55.0) | 39.0 (30.0–50.0) | 39.0 (31.0–51.0) | ||

| Urban residence | 53 (51.0) | 87 (56.9) | .42 | 20 (62.5) | 120 (53.3) | .43 | 140 (54.5) |

| SES tertile | .82 | .06 | |||||

| Lowest | 22 (21.2) | 26 (17.0) | 3 (9.4) | 45 (20.0) | 48 (18.7) | ||

| Middle | 25 (24.0) | 41 (26.8) | 6 (18.8) | 60 (26.7) | 66 (25.7) | ||

| Highest | 49 (47.1) | 72 (47.1) | 22 (68.8) | 99 (44.0) | 121 (47.1) | ||

| Missing | 8 (7.7) | 14 (9.2) | 1 (3.1) | 21 (9.3) | 22 (8.6) | ||

| HIV result | .61 | .88 | |||||

| Negative | 39 (37.5) | 56 (36.6) | 11 (34.4) | 84 (37.3) | 95 (37.0) | ||

| Positive | 17 (16.3) | 19 (12.4) | 4 (12.5) | 32 (14.2) | 36 (14.0) | ||

| No test | 48 (46.2) | 78 (51.0) | 17 (53.1) | 109 (48.4) | 126 (49.0) | ||

| Symptoms | |||||||

| Cough | … | … | |||||

| None | 73 (70.2) | 0 (0) | 32 (100) | 41 (18.2) | 73 (28.4) | ||

| <2 wk | 31 (29.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 31 (13.8) | 31 (12.1) | ||

| ≥2 wk | 0 (0) | 153 (100) | 0 (0) | 153 (68.0) | 153 (59.5) | ||

| Fever | <.001 | … | |||||

| None | 79 (76.0) | 73 (47.7) | 32 (100) | 120 (53.3) | 152 (59.1) | ||

| <2 wk | 13 (12.5) | 16 (10.5) | 0 (0) | 29 (12.9) | 29 (11.3) | ||

| ≥2 wk | 12 (11.5) | 64 (41.8) | 0 (0) | 76 (33.8) | 76 (29.6) | ||

| Chest pain | <.001 | … | |||||

| None | 56 (53.8) | 34 (22.2) | 23 (71.9) | 67 (29.8) | 90 (35.0) | ||

| <2 wk | 16 (15.4) | 10 (6.5) | 1 (3.1) | 25 (11.1) | 26 (10.1) | ||

| ≥2 wk | 32 (30.8) | 109 (71.2) | 8 (25.0) | 133 (59.1) | 141 (54.9) | ||

| Night sweats | .008 | … | |||||

| None | 75 (72.1) | 91 (59.5) | 32 (100) | 134 (59.6) | 166 (64.6) | ||

| <2 wk | 10 (9.6) | 8 (5.2) | 0 (0) | 18 (8.0) | 18 (7.0) | ||

| ≥2 wk | 19 (18.3) | 54 (35.3) | 0 (0) | 73 (32.4) | 73 (28.4) | ||

| Weight loss | <.001 | … | |||||

| None | 64 (61.5) | 67 (43.8) | 32 (100) | 99 (44.0) | 131 (51.0) | ||

| <2 wk | 10 (9.6) | 5 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 15 (6.7) | 15 (5.8) | ||

| ≥2 wk | 30 (28.8) | 81 (52.9) | 0 (0) | 111 (49.3) | 111 (43.2) | ||

| Duration of longest symptom, median (IQR), wk | 2.00 (1.0–4.0) | 4.00 (2.0–8.0) | <.001 | 0 (0.0–1.3) | 4.00 (2.0–8.0) | <.001 | 4.00 (2.0–8.0) |

| Duration of longest symptom, excluding cough, median (IQR), wk | 2.00 (1.0–4.0) | 4.00 (2.0–8.0) | <.001 | 0 (0.0–1.3) | 4.00 (2.0–8.0) | <.001 | 3.00 (1.0–6.0) |

| Subclinical tuberculosis: definition 1 | 104 (100) | 0 (0) | <.001 | 32 (100) | 72 (32.0) | <.001 | 104 (40.5) |

| Subclinical tuberculosis: definition 2 | 32 (30.8) | 0 (0) | <.001 | 32 (100) | 0 (0) | <.001 | 32 (12.5) |

Symptoms which defined comparison groups were not included in significance testing.

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; SES, socioeconomic status.

Unless otherwise indicated, data represent no. (%) of subjects, with percentages based on column totals provided in column headings.

Clinical Characteristics and Prevalence of Subclinical Tuberculosis

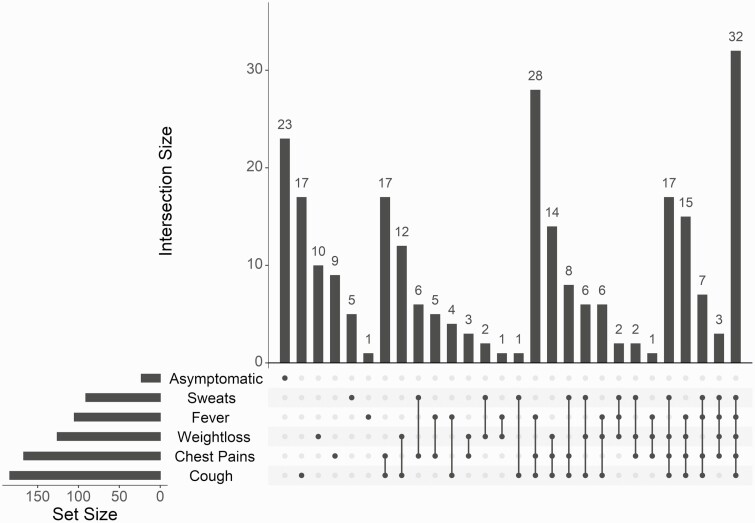

Participants with confirmed tuberculosis most frequently reported cough (71.6%), followed by chest pain (65.0%), weight loss (49.0%), fever (40.9%), and night sweats (35.4%) (for any duration; Table 1 and Figure 1). The most common symptom combinations were all 5 symptoms (12.5%) followed by cough, chest pain, and weight loss (10.9%) (Figure 1). Twenty-three subjects (8.9%) reported none of these symptoms; that is, they were asymptomatic with regard to the inquired symptoms. The prevalence of subclinical tuberculosis among subjects was 40.5% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 34.4%–46.7%) by definition 1 and 12.5% (8.7%–17.1%) by definition 2 (Table 1 and Figure 2). Of the 73 individuals not reporting any cough, the most common symptom combination was chest pain and night sweats (6 [8.2%]), followed by chest pain and fever (5 [6.8%]).

Figure 1.

Upset chart displaying symptom combinations (of any duration) by frequency for subjects. “Asymptomatic” refers to individuals without sweats, fever, weight loss, chest pain, or cough. Intersection size refers to the number of subjects with the indicated combination of symptoms; set size, the number experiencing each individual symptom.

Figure 2.

Euler diagram displaying share (numbers) of subjects meeting various definitions for subclinical tuberculosis. Definition 1: no cough persisting for ≥2 weeks, irrespective of other symptoms. subclinical tuberculosis; definition 2: no cough, fever, night sweats, or weight loss for any duration of time, irrespective of chest pain.

Clinical Presentation of Subjects Meeting Subclinical Tuberculosis Definition 1

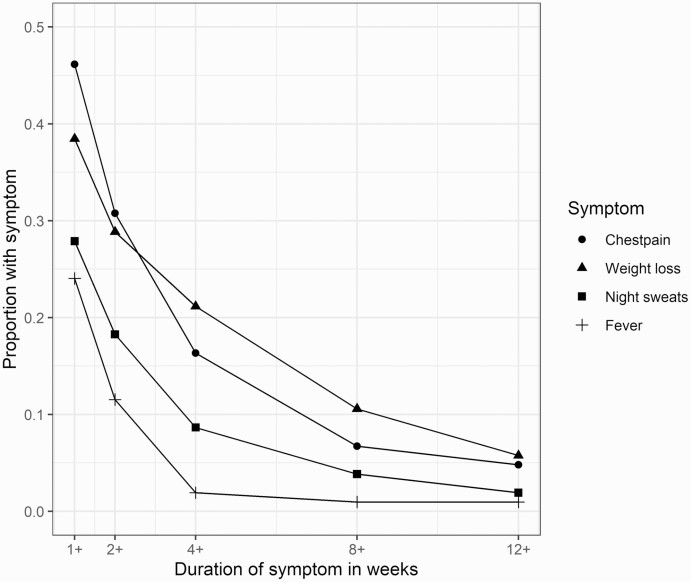

The 104 subjects with confirmed tuberculosis meeting definition 1 for subclinical tuberculosis (no cough persisting for ≥2 weeks) frequently presented with cough for <2 weeks or other symptoms (Figure 3). The median duration of the longest symptom for this group, not including cough, was 2 weeks (Table 2). The numbers of subjects meeting subclinical tuberculosis definition 1 who reported chest pain, fever, night sweats, and weight loss for <2 weeks were 48 (46.2%), 25 (24.0%), 29 (27.9%), and 40 (38.5%), respectively. For symptoms persisting ≥2 weeks, these numbers were 32 (30.8%), 12 (11.5%), 19 (18.3%), and 30 (28.8%), respectively. The numbers of subjects meeting subclinical tuberculosis definition 1 reporting their longest symptom duration (for symptoms other than cough) as ≥1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks were 79 (76.0%%), 58 (55.8%), 36 (34.6%), 17 (16.3%), and 10 (9.6%), respectively.

Figure 3.

Proportion of subjects with subclinical tuberculosis (defined according to definition 1) with chest pain, fever, night sweats, or weight loss, disaggregated by duration of symptoms.

Determinants

From logistic regression models, sex was found to be significantly associated with meeting the criteria for definition 1 of subclinical tuberculosis, and SES was found to be significantly associated with meeting the criteria for definition 2 (Table 3). The odds of meeting definition 1 for male subjects were 46% of the odds for female subjects (95% CI: 28%–77%). The odds of meeting definition 2 for those in the middle SES tertile was >3 times that of those in the lowest tertile (95% CI: 1.08–14.59). Spearman rank correlation test for duration of longest symptom versus SES tertile returned a ρ value of −0.137, indicating a tendency for the duration of longest symptom to be shorter for higher SES tertiles (P = .04).

Table 3.

Regression Table With Odds Ratios and Confidence Intervals for Unadjusted Associations, the Full Adjusted Model, and the Final Reduced Model for Both Definitions of Subclinical Tuberculosis

| Odds Ratio (95% CI)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subclinical Tuberculosis Definition 1 | Subclinical Tuberculosis Definition 2 | |||

| Subject Characteristics | Unadjusted | Final Adjusted | Unadjusted | Final Adjusted |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | Reference | … |

| Male | 0.46 (.28–.77) | 0.46 (.28–.77) | 0.74 (.35–1.57) | … |

| Age group, y | ||||

| 15–24 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| 25–35 | 0.75 (.31–1.8) | … | 1.12 (.33–4.45) | … |

| 35–44 | 0.59 (.25–1.43) | … | 0.54 (.13–2.35) | … |

| 45–54 | 1.46 (.58–3.71) | … | 0.87 (.21–3.77) | … |

| 55–64 | 1.34 (.44–4.12) | … | 2.11 (.49–9.65) | … |

| ≥65 | 0.5 (.17–1.4) | … | 1 (.22–4.63) | … |

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| Urban | 0.79 (.48–1.3) | … | 1.46 (.69–3.21) | … |

| SES tertile | ||||

| Lowest | Reference | … | Reference | Reference |

| Middle | 0.72 (.34–1.53) | … | 1.5 (.37–7.41) | 1.50 (.37–7.41) |

| Highest | 0.8 (.41–1.59) | … | 3.33 (1.08–14.59) | 3.33 (1.08–14.59) |

| Missing | 0.68 (.23–1.88) | … | 0.71 (.03–5.96) | 0.71 (.03–5.96) |

| HIV result | ||||

| Negative | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| Positive | 1.28 (.59–2.79) | … | 0.95 (.25–3.02) | … |

| No test | 0.88 (.51–1.53) | … | 1.19 (.54–2.75) | … |

| Constant | … | 1.04 (.72–1.50) | … | 0.07 (.02–.18) |

| Observations, no. | … | 257 | … | 257 |

| Log likelihood | … | −168.96 | … | −92.77 |

| AIC | … | 341.91 | … | 193.53 |

Abbreviations: AIC, Akaike information criterion; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SES, socioeconomic status.

Data represent odds ratios (95% CIs) except in the bottom 3 rows.

DISCUSSION

Of the 257 participants the Zambia tuberculosis prevalence survey with untreated confirmed tuberculosis, 40.5% and 12.5% met the criteria for definitions 1 (no cough persisting for ≥2 weeks) and 2 (no cough, fever, night sweats, or weight loss for any duration) for subclinical tuberculosis, respectively. Only 22.1% of those meeting definition 1 for subclinical tuberculosis did not present with cough, chest pain, fever, night sweats, or weight loss (8.9% of all subjects). Those meeting definition 1 for subclinical tuberculosis frequently reported other symptoms, particularly chest pain (46.2%) and weight loss (38.5%); 55.8% of those meeting subclinical tuberculosis definition 1 reported another symptom persisting ≥2 weeks, and 34.6% reported experiencing other symptoms for ≥4 weeks. Female subjects were more likely to have subclinical tuberculosis by definition 1, and relatively wealthier individuals more likely to meet criteria for definition 2.

Tuberculosis prevalence surveys, done since the 1990s, have reported 36.1%–79.7% (median, 50.4%) of tuberculosis cases to be subclinical, based on absence of cough persisting ≥2 weeks [3]. The current study shows that many are not asymptomatic: 76.0% of the subjects meeting definition 1 have ≥1 other symptom suggestive of tuberculosis, and often (55.8%) with a duration ≥2 weeks. This suggests that clinical practice in which tuberculosis diagnosis is guided only by the presence or absence of cough persisting ≥2 weeks could miss half of the cases that could be found using a more inclusive screening rule. If one would instead apply definition 2 in identifying subclinical tuberculosis, one would capture 87.5% of tuberculosis infections as diagnosed in the Zambia survey but at the expense of more individuals who need to be tested. Although definition 2 was based on a symptom screen for HIV-infected individuals, it is the only established symptom screen apart from the simple screen for cough persisting ≥2 weeks.

Definitions of subclinical tuberculosis found in literature are highly variable, but many use the term “asymptomatic,” suggesting a stricter definition than used in practice. True asymptomatic tuberculosis, by contrast, is uncommon. Only 22.1% of subjects meeting definition 1 for subclinical tuberculosis did not present with cough, chest pain, fever, night sweats, or weight loss (8.9% of all subjects). Our study may have even overestimated the proportion truly asymptomatic, since respondents may not have noticed some symptoms (eg, weight loss) and other, less typical symptoms may have been present but not ascertained. The high prevalence of symptoms in a group labeled “subclinical” is problematic and highlights the need for a standardized definition of subclinical tuberculosis.

The association of subclinical tuberculosis by definition 2 (ie, almost asymptomatic) with socioeconomic status is intriguing. The increasing probability of subclinical tuberculosis with increasing SES suggests a dose-response relationship, pointing to a true association rather than chance variation, which deserves further exploration. One hypothesis is that wealthier individuals have better access to care and on average had shorter duration of disease at the time they were captured in the prevalence survey. A rank correlation test between SES and symptom duration mildly supports this hypothesis.

There are several potential biases to consider when interpreting these results. The screening procedures and other filtration steps used in tuberculosis prevalence surveys, the Zambia survey notwithstanding, likely bias these surveys to identify active clinical tuberculosis as compared with any subclinical categories, including subclinical tuberculosis. In addition, field-read chest radiographs are known to lack sensitivity compared with expert review, particularly in populations with HIV [16]. Consequently, while the screening in the Zambia survey was more inclusive than most tuberculosis prevalence surveys, the estimates of subclinical tuberculosis prevalence presented here likely still strongly underestimate the true prevalence of subclinical tuberculosis by any definition.

A further limitation is that HIV status may confound associations between subclinical tuberculosis status and sex and SES; however, HIV status was missing in a high proportion of subjects (49%) owing to a high rate of test refusal. Refusal may have been linked to known HIV status, but these data were unfortunately not collected, precluding our ability to adequately adjust for this potential confounder.

In conclusion, the commonly used definition of subclinical tuberculosis (no cough persisting for ≥2 weeks) includes a large proportion of individuals with tuberculosis-suggestive symptoms other than cough and thus likely misses a large number of active tuberculosis infections. Therefore, a large reservoir of likely transmissible tuberculosis is allowed to remain undetected. Use of a more sensitive rule, namely the 4-symptom screen on which subclinical tuberculosis definition 2 is based, would enable much higher sensitivity, although at the cost of requiring more testing.

Contributor Information

Logan Stuck, Department of Global Health, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Amsterdam Institute for Global Health and Development, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Aimee Claire van Haaster, Amsterdam Institute for Global Health and Development, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Pascalina Kapata-Chanda, Ministry of Health, Lusaka, Zambiaand.

Eveline Klinkenberg, Department of Global Health, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Nathan Kapata, Ministry of Health, Lusaka, Zambiaand; Zambia National Public Health Institute, Lusaka, Zambia.

Frank Cobelens, Department of Global Health, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Amsterdam Institute for Global Health and Development, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

References

- 1. Barry CE, Boshoff H, Dartois V, et al. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: rethinking the goals of prophylaxis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009; 7:845–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Drain PK, Bajema KL, Dowdy D, et al. Incipient and subclinical tuberculosis: a clinical review of early stages and progression of infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2018; 31:e00021-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frascella B, Richards AS, Sossen B, et al. Subclinical tuberculosis disease—a review and analysis of prevalence surveys to inform definitions, burden, associations and screening methodology. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:e830–e841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Esmail H, Dodd PJ, Houben RMGJ.. Tuberculosis transmission during the subclinical period: could unrelated cough play a part?. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6:244–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Williams CM, Abdulwhhab M, Birring SS, et al. Exhaled Mycobacterium tuberculosis output and detection of subclinical disease by face-mask sampling: prospective observational studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20:607–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Central Statistical Office (Zambia). 2010 census of population national analytical report. Lusaka, Zambia: Central Statistical Office, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization, ed. TB impact measurement: policy and recommendations for how to assess the epidemiological burden of TB and the impact of TB control. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2013. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kapata N, Chanda-Kapata P, Ngosa W, et al. The prevalence of tuberculosis in Zambia: results from the first national TB prevalence survey, 2013–2014. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0146392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health (Zambia), International ICF. Zambia demographic and health survey 2013–14. Lusaka, Zambia: Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health, and ICF International, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chanda-Kapata P, Kapata N, Klinkenberg E, et al. The adult prevalence of HIV in Zambia: results from a population based mobile testing survey conducted in 2013-2014. AIDS Res Ther 2016; 13:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kapata N, Chanda-Kapata P, O’Grady J, et al. Trends of Zambia’s tuberculosis burden over the past two decades. Trop Med Int Health 2011; 16:1404–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2015. World Health Organization, 2015. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/191102. Accessed 20 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hamada Y, Lujan J, Schenkel K, Ford N, Getahun H.. Sensitivity and specificity of WHO’s recommended four-symptom screening rule for tuberculosis in people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV 2018; 5:e515–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization. Guidelines for intensified tuberculosis case-finding and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings. World Health Organization, 2011. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44472. Accessed 28 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reid MJ, Shah NS.. Approaches to tuberculosis screening and diagnosis in people with HIV in resource-limited settings. Lancet Infect Dis 2009; 9:173–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]