Abstract

Multitarget drugs are a promising therapeutic approach against Alzheimer’s disease. In this work, a new family of 5-substituted indazole derivatives with a multitarget profile including cholinesterase and BACE1 inhibition is described. Thus, the synthesis and evaluation of a new class of 5-substituted indazoles has been performed. Pharmacological evaluation includes in vitro inhibitory assays on AChE/BuChE and BACE1 enzymes. Also, the corresponding competition studies on BuChE were carried out. Additionally, antioxidant properties have been calculated from ORAC assays. Furthermore, studies of anti-inflammatory properties on Raw 264.7 cells and neuroprotective effects in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells have been performed. The results of pharmacological tests have shown that some of these 5-substituted indazole derivatives 1–4 and 6 behave as AChE/BuChE and BACE1 inhibitors, simultaneously. In addition, some indazole derivatives showed anti-inflammatory (3, 6) and neuroprotective (1–4 and 6) effects against Aβ-induced cell death in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells with antioxidant properties.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, BACE1 inhibitor, BuChE inhibitor, indazole, multitarget drug

1. Introduction

The current treatments for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are unsatisfactory because of their low effectiveness in the acute phase and their adverse side effects. During the last 19 years, a large number of clinical trials have been carried out; however, despite these efforts, no new drug has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)1. Recently the FDA approved Aduhelm (aducanumab) via the accelerated approval pathway2. However, it appears that Phase III studies are not giving the expected results3,4.

The cognitive impairments suffered by AD patients are associated with cholinergic neurotransmission, which seems to be closely related to the pathological formation of ß-amyloid5,6; therefore, cholinergic drugs like acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors7–11 are currently the most commonly prescribed.

In relation to cholinesterase enzymes, AD is characterised by a significant reduction in AChE activity and an increase in butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) activity. This increase in BuChE activity, especially found in the hippocampus, might be related to the loss of episodic memory12. Moreover, it has been reported that BuChE might facilitate the transformation of an initial benign form of senile plaque to a malignant form associated with AD13. On the other hand, BuChE-selective inhibitors have been reported to reduce ß-amyloid (Aß) and ß-amyloid precursor protein (APP) secretion in vitro and in vivo14,15. The generation of Aß deposits together with the formation of neurofibrillary tangles16–18 requires ß-secretase, also know as ß-site amyloid precursor protein (APP)-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1), which cleaves APP to release a soluble N-terminal fragment and a membrane-anchored C-terminal fragment19,20.

As the most recent clinical trials of BACE1 inhibitors have not shown great progress21, further research and a new strategy are required. Genetic evidence indicates that a gradual deletion of BACE1 not only reverses existing amyloid plaques, but also reduces gliosis and neuritic dystrophy while improving synaptic functions, therefore improving cognitive functions22. Thus, BACE1 inhibitors have multiple beneficial effects such as the reduction of Aβ generation and amyloid deposition; additionally, it can also reduce levels of potentially toxic APP-processing products such as the APP intracellular domain (AICD).

It is clear that the BuChE and BACE1 enzymes play an important role in AD and are therefore interesting targets for research into alternative drugs for the treatment of this pathology12,13,23,24. Considering that AD is a complex pathology in which a large number of pathways and therapeutic targets are involved25, it is reasonable to think that strategies such as multitarget drugs26–30 can be a good alternative as an effective treatment to fight this disease.

In this context, continuing with our effort of the advancement of an efficient strategy against AD from a multitarget approach, the development of new BACE1 inhibitors with simultaneous cholinergic properties has been the objective of this work. Thus, we describe the synthesis and biological evaluation of a new family of compounds based on the indazole ether scaffold extending the lateral chain at the 5-position in order to increase interactions with BACE1 receptors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. General

Melting points were determined using a MP70 (Mettler Toledo) apparatus and are uncorrected. 1H-NMR spectra (300 or 400 MHz) and 13 C-NMR spectra (75 or 100 MHz) were recorded on Varian INNOVA-300 (300 MHz) and Varian MERCURY-400 (400 MHz) spectrometers. The signal of the solvent was used as a reference. The chemical shifts are in ppm. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed using a Waters 2695 apparatus with a diode array UV/Vis detector Waters 2996 and coupled to a Waters micromass ZQ using a Sunfire C18 column (4.6 × 50 mm, 3.5 µm) at 30 °C, with a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min. The mobile phases used were: CH3CN and 0.1% formic acid in H2O. Electrospray in positive mode was used for ionisation. The sample injection volume was set to 3 µL of a solution of 1 mg/mL CH3CN. Gradient conditions, time of gradient (gt) and time of retention (rt) are specified in each case and a different gradient elution was specified in each case. Automated chromatographic separations were carried out in the Isolera Prime (Biotage) equipment with variable detector, using silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh) cartridges or KP C18-HS cartridges, both from Biotage. Elemental analyses were performed on a Heraeus CHN-O Rapid Analysis apparatus. The purity of all compounds was >95% prior to biological testing (Supporting Information).

Reagents and solvents were purchased from common commercial suppliers, mostly Sigma-Aldrich and Alfa-Aesar, and were used without further purification. 5-nitro-1H-3-indazolol (13) was prepared from the procedure reported by Pfannstiel31, 1-benzyl-5-nitro-3-indazolone (16) was prepared from the procedure reported by Palazzo32 and 1-benzyl-3-benzyloxy-5-nitroindazole (14)33, 1-(2-naphthylmethoxy)-3-(2-naphthylmethoxy)-5-nitroindazole (15) and 5-amino-1-benzyl-3-(benzyloxy)indazole (27) were synthesised using methods described by group34.

2.2. Chemistry

General procedures for the preparation of 5-piperidinopropylaminoindazole derivatives 1–6 and 5-carbonylamino derivatives 7–12, N-1 substituted 3-indazolol derivatives 17–20, and 5-aminoindazoles 28–34, together with spectroscopic characterisation of new compounds can be found in the Supporting Information.

2.3. Biological assays

2.3.1. In vitro cholinesterase inhibition assays

AChE from human erythrocytes (EC 3.1.1.7) (min. 500 units/mg protein in buffered aqueous solution) and BuChE from human serum (EC 3.1.1.8) (3 units/mg protein, lyophilised powder) were purchased from Sigma.

Compounds were evaluated in 100 mM phosphate buffer pH 8.0 at 30 °C, using acetylthiocholine and butyrylthiocholine (0.4 mM) as substrates, respectively. In both cases, 5,5-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic) acid (DTNB, Ellman’s reagent, 0.2 mM) was used and the values of IC50 were calculated by UV spectroscopy from the absorbance changes at 412 nm. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.3.2. Kinetic study of BuChE inhibition

To investigate the mechanism of action of the compounds on AChE or BuChE, a kinetic analysis was performed. The experiments were carried out using combinations of four substrate concentrations and three inhibitor concentrations. Double-reciprocal Lineweaver–Burk plots of the data obtained, in which each point is the mean of three different experiments, were analysed.

Competitive inhibitors have the same y-intercept as uninhibited enzymes (since Vmax is unaffected by competitive inhibitors the inverse of Vmax also doesn’t change), but there are different slopes and x-intercepts. Non-competitive inhibition produces plots with the same x-intercept as uninhibited enzyme (Km is unaffected) but different slopes and y-intercepts. Uncompetitive inhibition causes different intercepts on both the y- and x-axes, but the same slope. Mixed inhibitors cause intersects above or below the x-axes.

The Ki, values were determined by fitting the kinetic data to a competitive, non-competitive, or mixed inhibition model by nonlinear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism35.

2.3.3. The BACE1 enzymatic assay

The BACE1 (EC 3.1.1.8) assay was carried out according to the manufacturer’s described protocol which is available from Invitrogen36.

Briefly, BACE1 in vitro assays were carried out using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). An APP-based peptide substrate (rhodamine-EVNLDAEFK-quencher, Km of 20 μM) carrying the Swedish mutation and containing rhodamine as a fluorescence donor and a quencher acceptor at each end was used. The intact substrate is weakly fluorescent and becomes highly fluorescent upon enzymatic cleavage. The assays were conducted in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.5, at a final enzyme concentration of 1 U/mL. Inhibitor screening was performed at 10 μM. The mixture was incubated for 60 min at 25 °C under dark conditions and then stopped with 2.5 M sodium acetate. Fluorescence was measured with a FLUOstar Optima (BMG Labtechnologies GmbH, Offenburg, Germany) microplate reader at 545 nm excitation and 585 nm emission. The assay kit was validated by the manufacturer.

2.3.4. Oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay

The ORAC-FL method of Ou et al.37, partially modified by Dávalos et al.38, was followed, using a FLUOstar Optima (BMG Labtechnologies GmbH, Offenburg, Germany) with 485 excitation and 520 emission filters. 2,2′-Azobis-(amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH), (±)-6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchromane-2-carboxylic acid (trolox) and fluorescein (FL) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The reaction was carried out in 75 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and the final reaction mixture was 200 µL. Antioxidant (25 µL) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a concentration of 1 mM and diluted in advance in an assay buffer to the desired concentration; the final DMSO concentration in the reaction mixture did not exceed 1% and FL (150 µL; 10 nM) solutions were placed in a black 96-well microplate (96 F untreat, NuncTM). The mixture was pre-incubated for 30 min at 37 °C and then AAPH solution (25 µL, 240 mM) was added rapidly using a multichannel pipette. The microplate was immediately placed in the reader and the fluorescence was recorded every 90 s. for 90 min. The microplate was automatically shaken prior to each reading. Samples were measured at four different concentrations (10−1 µM). A blank (FL + AAPH in phosphate buffer) instead of the sample solution and four calibration solutions using trolox (10−1 µM) was also used in each assay. All of the reaction mixtures were prepared in duplicate and at least three independent assays were performed for each sample. Raw data were exported from the Fluostar optima Software to an Excel sheet for further calculations. Antioxidant curves (fluorescence vs. time) were represented and the area under the curve (AUC) is calculated as:

where fo = initial fluorescence reading at 0 min and fi = fluorescence reading at time i. The net AUC is obtained by subtracting the AUC of the blank from that of a sample. The relative Trolox equivalent ORAC value is calculated as:

2.3.5. Nitrite determinations

The content of nitrite, one of the end-products of NO oxidation, was monitored by a procedure based on the diazotidation of nitrite by sulphanilic acid (Griess reaction). Twenty-four hours after the incubation of Raw 264.7 cells with 0.4 µg/mL of LPS, 50 µL of sample aliquots were mixed with 50 µL of Griess reagent in 96-well plates and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The absorbance (520 nm) of the mixture was measured on a microplate reader. The concentration of nitrite was calculated with the linear equation derived from the standard curve generated by known concentrations of sodium nitrite.

2.3.6. Amyloid-beta peptide neurotoxicity

SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere in DMEM-Glutamax supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% foetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. All experiments with Aβ1–42 used DMEM-Glutamax without phenol in the media.

The compounds were dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) as a 10 mM stock and diluted with culture medium to final concentrations. Aβ1–42 powder (AnaSpec, Inc., San Jose, CA) was dissolved in acetic acid (0.1 M) obtaining a 2 μg/μL stock. Then Aβ1-42 was oligomerised in no phenol red DMEM for 24 h at 37 °C. The final concentration in cells cultures was 5 μM. All dilutions of stock were prepared fresh before addition to the culture medium.

SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 5 μM Aβ1-42 for 24 h and pre-treated or not for 1 h with increasing concentrations of compounds. After treatment, cultures were processed for a cell viability assay using MTT assay.

2.3.7. Cell viability assay

Cell viability was measured using the 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay, based on the ability of viable cells to reduce yellow MTT to blue formazan. Briefly, cells cultured in 96-well plates and treated with the indicated compounds for 16 h were incubated with MTT (0.5 mg/ml, 4 h) and subsequently solubilised in DMSO. The extent of reduction of MTT was quantified by absorbance measurement at 595 nm according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

3. Results and discussion

Based on previous results, one possible way to develop BACE1 inhibitors consists of introducing different functional groups in position 5 of the indazole structure. Thus, different functionalised groups such as indazolyl benzamides, indazolyl ureas and 5-piperidinopropylaminoindazole derivatives were chosen. In the other two positions of the of the indazole system, N-1 and O-3, different groups were also included to achieve different families and therefore chemical diversity. A variety of aromatic groups such as benzyl, 4-chlorobenzyl, 2,3-dichlorobenzyl, 3,4-dichlorobenzyl, 1-naphthylmethyl and 2-naphthylmethyl were selected as substituents at position 1 and oxygen at position 3 of indazole ring.

3.1. Chemistry

Representative sets of compounds (1–12) were proposed as potential candidates (Table 1). The synthetic methodology for accessing the target compounds 1–12 was based on the introduction of the different groups at N-1 position or at the hydroxyl group of the 5-nitroindazolol 13 through well-established N-alkylation or O-alkylation procedures34 (Scheme 1) and further transformation of the nitro group at position 5 of the indazole ring (Scheme 2).

Table 1.

Inhibition of AChE, BuChE, BACE1 (IC50, μM) and antioxidant activity (ORAC) of selected indazole derivatives and inhibition type of BuChE inhibitors.

| compd | R 1 | R 2 | R 3 | AChEa IC50 (µM) | BuChEa IC50 (µM) | Type of Inhibition (BuChE)b | BACE1c IC50 (µM) | ORACd (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ph | 1-naphthyl | NH(CH2)3-piperidino | >10 (23 %) | 3.2 ± 0.5 | M | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| 2 | 2,3-diClPh | Ph | NH(CH2)3-piperidino | >10 (27 %) | 0.40 ± 0.04 | M | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| 3 | 3,4-diClPh | 1-naphthyl | NH(CH2)3-piperidino | >10 (38%) | 0.17 ± 0.05 | M | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| 4 | 3,4-diClPh | 2-naphthyl | NH(CH2)3-piperidino | >10 (26%) | 0.57 ± 0.2 | M | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| 5 | 1-naphthyl | 2,3-diClPh | NH(CH2)3-piperidino | >10 | >10 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | |

| 6 | 2-naphthyl | 2-naphthyl | NH(CH2)3-piperidino | 9 ± 1 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | M | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 0 |

| 7 | Ph | Ph | NHCO(2,3-diClPh) | 7.6 ± 0.3 | >10 | (60%) | 0 | |

| 8 | Ph | 1-naphthyl | NHCO(NEt2) | >10 (29 %) | >10 | 9.1 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | |

| 9 | 4-ClPh | 1-naphthyl | NHCON(Ph,Me) | >10 | >10 | >10 (29%) | 0.6 ± 0.1 | |

| 10 | 3,4-diClPh | 1-naphthyl | NHCON(Ph)2 | >10 (28 %) | >10 | >10 (10%) | 0.2 ± 0.1 | |

| 11 | 2,3-diClPh | Ph | NHCO(4-methylpiperazino) | >10 | >10 (47%) | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | |

| 12 | 1-naphthyl | 2,3-diClPh | NHCO(1-pyrrolidinyl) | >10 | >10 | >10 (43%) | 0.5 ± 0.1 | |

| 27 | Ph | Ph | NH2 | 8.6 ± 0.5 | >10 (21%) | >10 (2%) | 0.9 ± 0.1 | |

| 28 | 2-naphthyl | 2-naphthyl | NH2 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | >10 (24%) | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | |

| 29 | 2,3-diClPh | Ph | NH2 | >10 | >10 | >10 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | |

| 30 | 1-naphthyl | 2,3-diClPh | NH2 | >10 (36 %) | >10 | (79%) | 0.8 ± 0.1 | |

| 31 | 3,4-diClPh | 2-naphthyl | NH2 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | >10 (30%) | (69%) | 0.63 ± 0.04 | |

| 32 | Ph | 1-naphthyl | NH2 | >10 | >10 | >10 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | |

| 33 | 4-ClPh | 1-naphthyl | NH2 | >10 | >10 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | |

| 34 | 3,4-diClPh | 1-naphthyl | NH2 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | >10 (32%) | (72%) | 0.33 ± 0.05 |

IC50 values (mean ± SEM) were determined from 3 different experiments using acetylthiocholine and butyrylthiocholine (0.8 and 0.5 µM, respectively) as substrates. In parentheses: percentage of inhibition at 10 µM.

BuChE inhibition type, M: mixed.

IC50 values (mean ± SEM). In parentheses: percentage of inhibition at 10 µM.

ORAC: Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity. Data are expressed as μmol of Trolox equivalents/μmol of tested compound.

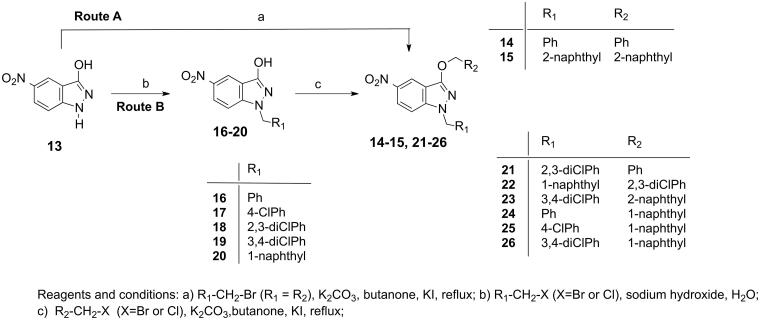

Scheme 1.

Synthetic routes for the preparation of 5-nitroindazole derivatives 14–26.

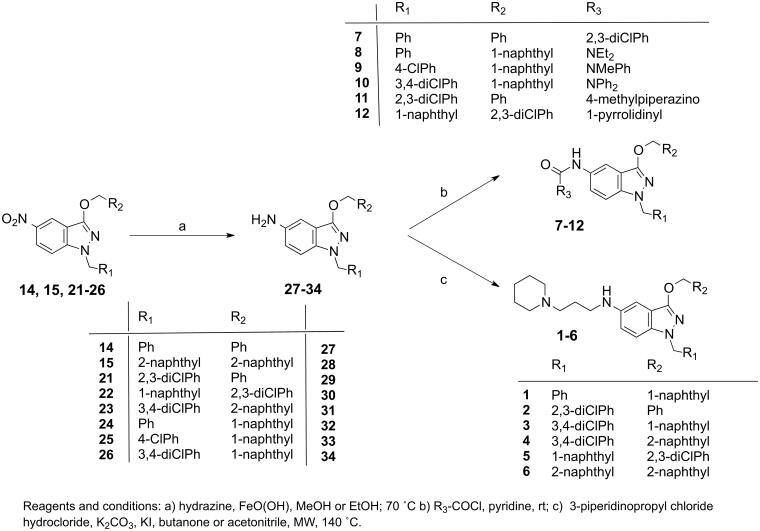

Scheme 2.

Synthetic routes for the preparation of 5-aminosubstituted indazole derivatives 1–12.

The reaction of the starting 5-nitroindazole 13 with alkyl halides under refluxing of butanone solvent (route A, Scheme 1) was useful to obtain disubstituted derivatives with identical groups at both N- and O-positions (14, 15). For derivatives with different groups at N-1 and OH at C3, route B was applied (Scheme 1).

This synthetic route consists of a two-step sequence involving initial alkylation with the suitable benzylic halide at the more nucleophilic N-1 position of the indazole derivative and then introduction of the second substituent at position 3-OH using different benzylic halides.

Following route A, when the indazole ether derivative has the same substituent at both the N-1 and O-3 positions, the reaction was carried out in potassium carbonate and potassium iodide in butanone. Thus, the preparation of the 1-substituted benzyl and naphthyl indazole ethers 14 and 15 were carried out starting from 5-nitroindazolol 13 and benzyl bromide and naphthyl bromide34, respectively (Scheme 1).

The synthesis of 1,3-disubstituted indazoles with different groups at N-1 position and ether function were performed following a more versatile synthetic route B, starting from 5-nitroindazolol 13 and the corresponding halides in an aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide.

Thus, the reaction of 13 with the corresponding bromides or chlorides afforded the N-1 benzyl, 4-chlorobenzyl and 2,3-dichlorobenzyl 16–18 and the 3,4-dichlorobenzyl and 1-naphthylmethyl 3-indazolol derivatives 19–20, respectively. Subsequent O-alkylation of 16–20 with the corresponding bromides of benzyl, 2,3-dichlorobenzyl and 2-naphthylmethyl and the 1-naphthylmethyl chloride afforded the indazole ethers of benzyloxy 21, 2,3-dichlorobenzyloxy 22, 2-naphthylmethoxy 23 and 1-naphthylmethoxy 24–26, respectively.

For the preparation of 5-aminoindazole ethers, we performed novel modifications in the indazole ether system via the reduction of 5-nitroindazoles (Scheme 2). In this sense, the conversion of the nitro group at C-5 into the corresponding 5-amino derivative was achieved by treatment with hydrazine and ferric oxyhydroxide FeO(OH) as a catalyst34. The FeO(OH) was prepared by the treatment of FeCl3 and sodium hydroxide solution39. Thus, the reduction of the 5-nitro derivatives 14, 15 and 21–26 afforded the corresponding 5-amino derivatives 27–34, respectively.

The more interesting family selected, the 5-piperidinopropylaminoindazole derivatives, were prepared from the corresponding 1,3-disubstituted 5-aminoindazoles with piperidinopropyl chloride. Thus, the synthesis of indazole ethers 1–6 was carried out starting from the 5-amino-1-substituted derivatives of benzyl 29, 2,3-dichlorobenzyl 30, 1-naphthyl 32 and 34 and 2-naphthylmethyl ethers 28 and 31.

Finally, the second selected family, the indazolyl carboxamides 7–12, was analysed through the reaction of 1,3-disubstituted 5-aminoindazoles with acyl chloride. Thus, the indazolyl-2,3-dichlorobenzamide 7 was obtained by the reaction of the 5-aminoindazole 27 with the corresponding acyl halide in the presence of pyridine.

The indazolyl urea derivatives were prepared in a similar way. The reaction of 3-naphthylmetoxy derivatives 32–34 with diethylcarbamoyl chloride, N-Methyl-N-phenylcarbamoyl chloride and diphenylcarbamyl chloride afforded the corresponding indazolyl ureas 8–10, respectively. Finally, the piperazinyl and pyrrolidinyl carboxamides 11 and 12 were prepared from 29 and 30 with the 4-methyl-1-piperazinecarbonyl chloride and the 1-pyrrolidinecarbonyl chloride, respectively.

The structures of synthesised compounds (1–12, 14–35) were established as N1 and N-1/O3 disubstituted indazoles on the basis of NMR data (Supplemental Tables S1 and S2). The position of the 1 and 3 substituents can be clearly distinguished by 13 C-NMR spectra examining the chemical shifts (supplemental Table S2). Thus, the signals corresponding to aromatic methylene group attach at O-3 (68.5–71.8 ppm) appear at lower fields in relation to aromatic methylene at N-1 (51.1–53.0 ppm).

3.2. Biological assays

3.2.1. Ache/BuChE inhibitory activity

The derivatives corresponding to final families 1–12 and their precursors, the 5-aminoindazoles 27–34 were subjected to enzymatic assays40 in order to evaluate their capacity to inhibit human AChE and BuChE. Those compounds that inhibited >50% had their IC50 calculated. The experimental values, both % inhibition and IC50, are shown in Table 1. Unfortunately, not all quantitative values of IC50 could be determined for solubility reasons.

In relation to 5-aminoindazoles 27–34, regarding AChE inhibition, compounds 27, 28, 31 and 34 showed enzymatic inhibition with IC50 values less than 10 µM. However, in relation to BuChE inhibition, neither compound showed interesting activity, although the compounds that behave as BuChE inhibitors (27, 28, 31 and 34) showed a very slight inhibition at 10 µM.

The results obtained for AChE inhibition of target indazoles (1–12) indicate that several derivatives have significant activity as inhibitors of this enzyme, with compounds 6 and 7 showing lower IC50 values among the 5-substituted indazoles.

However, the most relevant activity was found in relation to BuChE enzymatic assays, with the 5-aminosubstituted indazoles 1–4, 6 and 11 being the most interesting compounds in relation to the inhibition of BuChE. It should be noted that the N-1 dichlorobenzyl derivatives 2–4 showed the lowest IC50 values, in the submicromolar range, among the piperidinopropylamino derivatives.

According to values of inhibitory activity for BuChE and AChE, the most interesting compounds in BuChE enzymatic inhibition are derivatives 2–4, which showed lower activities in AChE. The naphthyl derivative 6 is the only compound that showed activity in both enzymes in the micromolar range.

3.2.2. Kinetic study of BuChE inhibition

In order to obtain better knowledge about the mechanism of action of this family of compounds, a kinetic study was carried out with the most promising BuChE inhibitors. Lineweaver–Burk plots were used for the indazole derivatives 1–4 and 6, with donepezil as a reference compound; these are shown in supplementary material (supplemental Fig. S1) and the data gathered in Table 1.

The IC50 for BuChE inhibitors (Table 1) was determined by fitting the kinetic data to a competitive, non-competitive, or mixed inhibition model by nonlinear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 535.

Regarding the inhibition type of BuChE, Lineweaver–Burk plots obtained for 1–4 and 6 (supplemental Figure S1) showed both increasing slopes (decreased at increasing inhibitor concentrations) and increasing intercepts with a higher inhibitor concentration and similar plots to those shown by donepezil and therefore according to a mixed type competitive BuChE inhibition mode of action. Kinetic studies suggested two potential different sites of interaction: the active site and the peripheral binding site.

3.2.3. BACE1 enzymatic assay

The BACE1 assay was carried out according to the described protocol available from Invitrogen36. The percentages of inhibition for BACE1 were determined for all 5-aminoindazole ethers 27–34, 5-piperidinopropylamine 1–6, indazolyl benzamide 7 and indazolyl ureas 8–12 at 10 µM (Table 1).

Those compounds that inhibit 100% up to 10 µM were selected for the determination of IC50 and consideration for later studies (Table 1). The results presented in Table 1 indicate that only the 5-amino derivatives 28 and 33 showed activity as inhibitors of BACE1. In relation to the selected family of indazolyl carboxamides 7–12, only the indazolyl derivative 8 and the piperazinyl carboxamide derivative 11 showed activity as inhibitors of BACE1. The most interesting results correspond to all indazoles bearing the 5-piperidinopropylamine substituent 1–6, which showed the lowest IC50 values, and 5-piperazinocarboxamide 11.

The analyses of the results gathered in Table 1, according to values of inhibitory activity for AChE, BuChE and BACE1 enzymes, indicate that the most interesting compounds selected to study their anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects were the multitarget derivatives 1–4 and 6, which behave as BACE1 inhibitors with simultaneous activity as AChE/BuChE inhibitors.

3.2.4. Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activities of the indazole ether derivatives 1–12 and 27–34 were evaluated by following the well-established ORAC-FL method (oxygen radical absorbance capacity by fluorescence)37,38.

The antioxidant activity shown by the amino indazole derivatives is essentially unchanged in the corresponding 5-amino substituted indazoles, except for compound 7 which lost the effect.

In relation to the most interesting compounds 1–12, the results shown in Table 1 indicate that most indazole derivatives exhibit antioxidant properties except compound 6 and 7. The 5-piperidinopropilaminoindazole derivatives 1–5, carboxamides 8, 9 and the piperazinocarbonylamino derivative 11 showed antioxidant properties with values higher than 60% in relation to Trolox. It is worth highlighting that compounds 1 and 11 protect against free radicals in a similar manner as the reference compound Trolox.

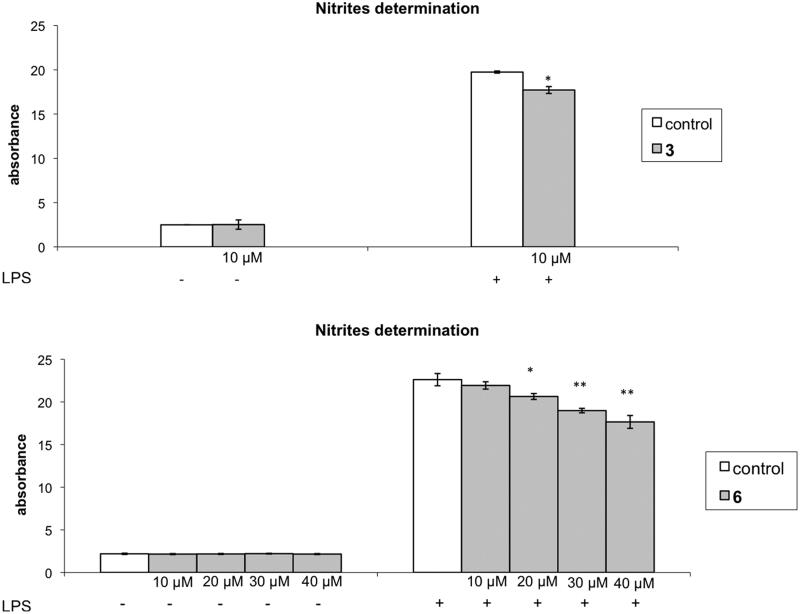

3.2.5. Anti-inflammatory effect of selected indazole derivatives

Among the most commonly employed methods to evaluate anti-inflammatory responses is the LPS-treated Raw 264.7 murine macrophage model. The exposure of Raw 264.7 macrophages to external bacterial toxins like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has been extensively shown to stimulate the secretion of nitric oxide (NO), which is produced by the inducible isoforms of nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)41. Thus, many studies have evaluated the effects of anti-inflammatory agents on the direct inhibition of NO production42.

An analysis of the results (Table 1), according to values of inhibitory activity for AChE, BuChE and BACE1, indicates that the most interesting compounds selected for the study of inflammation and neuroprotective effects should be the multitarget derivatives 1–4 and 6, which behave as BACE1 inhibitors with simultaneous activity as AChE/BuChE inhibitors.

The anti-inflammatory effects of selected 5-substituted indazole derivatives were evaluated from the study of the NO production on cells exposed to LPS and the relevant results are represented in the Figure 1. The effect of indazole derivatives 1–4, 6 on murine Raw 264.7 cells viability was examined. The assays to 10 µM reveal that 1, 2 and 4 show cytotoxicity, while 3 (10 µM) and 6 (10, 20, 30, 40 µM) did not show any significant cytotoxic effect.

Figure 1.

Anti-inflammatory effects of compounds 3 and 6. The production of extracellular nitrite in Raw 264.7 cells stimulated with LPS (0.4 µg/mL) for 24 h with and without compounds 3 (10 µM) and 6 (10–40 µM). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD from two independent experiments and quantified using Griess reagent. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.1 significantly different from LPS-treated cells.

When control cells were exposed to LPS, the piperidinopropylamino derivatives 3 and 6 were able to attenuate LPS-induced NO production at 10 µM, while 6 inhibited NO production at 20, 30 and 40 µM.

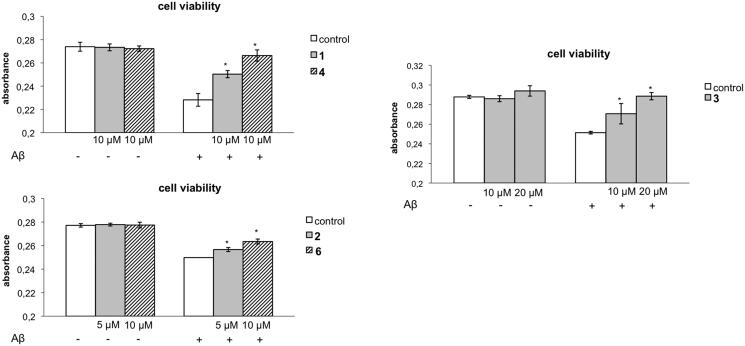

3.2.6. Neuroprotective effect of indazole derivatives on β-Amyloid-Induced death in AD neuronal models

Aβ peptide is toxic to cells both in vivo and in vitro43,44, inducing the death of human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Thus, the human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells45 are used as in vitro models of neuronal function and differentiation being one of the most common cell line used in vitro for biochemical and toxicological studies of Aβ1-42 amyloid peptide46.

The effect of the most interesting derivatives 1–4 and 6 has been studied from the survival of Aβ-treated SH-SY5Y cells and the results are shown in Figure 2. Two conclusions can be drawn from the results: (i) the derivatives do not show cytotoxicity at the concentration studied (Figure 2); and (ii) as expected, Aβ-induced death of SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 2) and the indazole derivatives 1, 3, 4 and 6 tested significantly reduced cell death at 10 µM, meanwhile compound 2 is able to prevent cell death at a lower concentration, 5 µM.

Figure 2.

Neuroprotective effects of compounds 1–4 and 6 on β-amyloid (Aβ)-induced death in neuronal cells. Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 5 µM Aβ for 24 h with and without compounds 1, 4, 6 (10 µM), 2 (5 µM) and 3 (10 and 20 µM) (maximum non-toxic concentrations) added 1 h prior to Aβ incubation. The number of viable cells after drug treatments was measured by the 3–(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazoliumbromide assay. Each data point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean for four different experiments. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.1 significantly different from Aβ-treated cells.

These results could be explained in a similar way to the effect of galanthamine against Aβ1-42-induced genotoxic and cytotoxic damages in the SH-SY5Y cell line. Thus, this compound may exert antigenotoxic properties and regulate cell loss in addition to effects as an AChE inhibitor and antioxidant activity47.

4. Conclusions

The aim of this research was to identify and propose a valid multitarget approach as a potential therapeutic strategy to fight against diseases characterised by inflammatory and neurodegenerative symptoms such as Alzheimer’s disease. Thus, we developed a new series of indazole derivatives with a multitarget profile, being inhibitors of ChE (AChE/BuCHE) and/or BACE-1 enzymes.

The piperidinopropylaminoindazole derivatives have shown the most interesting properties since they behave as simultaneous AChE/BuChE and BACE1 inhibitors. In relation to this series, the derivatives 1–4 and 6 should be emphasised according to neuroprotective effect.

Importantly, the same derivative that behaves as an AChE/BuChE/BACE1 inhibitor, compound 3, was shown to exhibit anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects with antioxidant properties. All of these results together highlight the great potential of this new family as a lead compound for the development of drugs as potential treatments for AD.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This work was supported from Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad, Gobierno de España under Grant RTI2018-096100B-100.

Author contributions

The manuscript was realised through the contributions of all authors. All authors have approved this version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Yiannopoulou KG, Anastasiou AI, Zachariou V, Pelidou SH.. Reasons for failed trials of disease-modifying treatments for Alzheimer disease and their contribution in recent research. Biomedicines 2019;7:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/aducanumab-marketed-aduhelm-information.

- 3.Knopman DS, Jones DT, Greicius MD.. Failure to demonstrate efficacy of aducanumab: An analysis of the EMERGE and ENGAGE trials as reported by Biogen, December 2019. Alzheimers Dement 2021;17:696–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.https://investors.biogen.com/static-files/8e58afa4-ba37-4250-9a78-2ecfb63b1dcb.

- 5.Geula C, Darvesh S.. Butyrylcholinesterase, cholinergic neurotransmission and the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Today (Barc) 2004;40:711–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schliebs R. Basal forebrain cholinergic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease–interrelationship with beta-amyloid, inflammation and neurotrophin signaling. Neurochem Res 2005;30:895–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abeysinghe A, Deshapriya R, Udawatte C.. Alzheimer’s disease; a review of the pathophysiological basis and therapeutic interventions. Life Sci 2020;256:117996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Claassen JA, Jansen RW.. Cholinergically mediated augmentation of cerebral perfusion in Alzheimer’s disease and related cognitive disorders: the cholinergic-vascular hypothesis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006;61:267–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulthard E, Singh-Curry V, Husain M.. Treatment of attention deficits in neurological disorders. Curr Opin Neurol 2006;19:613–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villarroya M, García AG, Marco-Contelles J, López MG.. An update on the pharmacology of galantamine. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2007;16:1987–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klafki HW, Staufenbiel M, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J.. Therapeutic approaches to Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2006;129:2840–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamal MA, Qu X, Yu QS, et al. Tetrahydrofurobenzofuran cymserine, a potent butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor and experimental Alzheimer drug candidate, enzyme kinetic analysis. J Neural Transm 2008;115:889–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lane RM, Potkin SG, Enz A.. Targeting acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase in dementia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2006;9:101–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diamant S, Podoly E, Friedler A, et al. Butyrylcholinesterase attenuates amyloid fibril formation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:8628–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greig NH, Utsuki T, Ingram DK, et al. Selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibition elevates brain acetylcholine, augments learning and lowers Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide in rodent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:17213–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and its receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: pathways, pathogenesis and therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009;10:333–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haass C, Schlossmacher MG, Hung AY, et al. Amyloid beta-peptide is produced by cultured cells during normal metabolism. Nature 1992;359:322–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ.. A beta oligomers – a decade of discovery. J Neurochem 2007;101:1172–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung D, Abbenante G, Fairlie DP.. Protease inhibitors: current status and future prospects. J Med Chem 2000;43:305–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durham TB, Shepherd TA.. Progress toward the discovery and development of efficacious BACE inhibitors. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel 2006;9:776–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDade E, Voytyuk I, Aisen P, et al. The case for low-level BACE1 inhibition for the prevention of Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2021;17:703–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu X, Das B, Hou H, et al. BACE1 deletion in the adult mouse reverses preformed amyloid deposition and improves cognitive functions. J Exp Med 2018;215:927–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Annicchiarico R, Federici A, Pettenati C, Caltagirone C.. Rivastigmine in Alzheimer’s disease: Cognitive function and quality of life. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2007;3:1113–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bullock R, Lane R.. Executive dyscontrol in dementia, with emphasis on subcortical pathology and the role of butyrylcholinesterase. Curr Alzheimer Res 2007;4:277–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breijyeh Z, Karaman R.. Comprehensive review on Alzheimer’s disease: causes and treatment. Molecules 2020;25:5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bajda M, Guzior N, Ignasik M, Malawska B.. Multi-target-directed ligands in Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Curr Med Chem 2011;18:4949–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paez JA, Campillo NE.. Innovative therapeutic potential of cannabinoid receptors as targets in Alzheimer’s disease and less well-known diseases. Curr Med Chem 2019;26:3300–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rook Y, Schmidtke KU, Gaube F, et al. Bivalent beta-carbolines as potential multitarget anti-Alzheimer agents. J Med Chem 2010;53:3611–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Incerti M, Flammini L, Saccani F, et al. Dual-acting drugs: an in vitro study of nonimidazole histamine H3 receptor antagonists combining anticholinesterase activity. ChemMedChem 2010;5:1143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piazzi L, Cavalli A, Colizzi F, et al. Multi-target-directed coumarin derivatives: hAChE and BACE1 inhibitors as potential anti-Alzheimer compounds. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2008;18:423–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfannstiel K, Janecke J.. Representation of o-hydrazino-benzoic acids and indazolones by reduction of diazotated anthranilic acids with sulphuric acid. Chem Ber 1942;75:1096–107. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baiocchi L, Corsi G, Palazzo G.. Synthesis, properties and reactions of 1H-indazol-3-ols and 1-2-dihydro-3h-indazol-3-ones. Synthesis-Stuttgart 1978;1978:633–48. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arán VJ, Flores M, Munoz P, et al. Analogues of cytostatic, fused indazolinones: Synthesis, conformational analysis and cytostatic activity against HeLa cells of some 1-substituted indazolols, 2-substituted indazolinones, and related compounds. Liebigs Ann 2006;1996:683–91. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalez-Naranjo P, Perez-Macias N, Campillo NE, et al. Cannabinoid agonists showing BuChE inhibition as potential therapeutic agents for Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Med Chem 2014;73:56–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.GraphPad_Prism . 5.0; San Diego (CA): GraphPad Software; 2013.

- 36.http://tools.invitrogen.com/content/sfs/manuals/L0724.pdf.

- 37.Ou B, Hampsch-Woodill M, Prior RL.. Development and validation of an improved oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay using fluorescein as the fluorescent probe. J Agric Food Chem 2001;49:4619–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davalos A, Gomez-Cordoves C, Bartolome B.. Extending applicability of the oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC-fluorescein) assay. J Agric Food Chem 2004;52:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lauwiner M, Rys P, Wissmann J. Reduction of aromatic nitro compounds with hydrazine hydrate in the presence of an iron oxide hydroxide catalyst. I. The reduction of monosubstituted nitrobenzenes with hydrazine hydrate in the presence of ferrihydrite. Appl Catal A-Gen 1998;172:7. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Featherstone RM.. Jr. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol 1961;7:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee JY, Woo ER, Kang KW.. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by acteoside through blocking of AP-1 activation. J Ethnopharmacol 2005;97:561–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan MM, Ho CT, Huang HI.. Effects of three dietary phytochemicals from tea, rosemary and turmeric on inflammation-induced nitrite production. Cancer Lett 1995;96:23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pike CJ, Burdick D, Walencewicz AJ, et al. Neurodegeneration induced by beta-amyloid peptides in vitro: the role of peptide assembly state. J Neurosci 1993;13:1676–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geula C, Wu CK, Saroff D, et al. Aging renders the brain vulnerable to amyloid beta-protein neurotoxicity. Nat Med 1998;4:827–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biedler JL, Roffler-Tarlov S, Schachner M, Freedman LS.. Multiple neurotransmitter synthesis by human neuroblastoma cell lines and clones. Cancer Res 1978;38:3751–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kruger TM, Bell KJ, Lansakara TI, et al. A soft mechanical phenotype of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma and primary human neurons is resilient to oligomeric Abeta(1-42) injury. ACS Chem Neurosci 2020;11:840–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castillo WO, Aristizabal-Pachon AF, de Lima Montaldi AP, et al. Galanthamine decreases genotoxicity and cell death induced by beta-amyloid peptide in SH-SY5Y cell line. Neurotoxicology 2016;57:291–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- GraphPad_Prism . 5.0; San Diego (CA): GraphPad Software; 2013.