Abstract

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium can differentiate into hyperflagellated swarmer cells on agar of an appropriate consistency (0.5 to 0.8%), allowing efficient colonization of the growth surface. Flagella are essential for this form of motility. In order to identify genes involved in swarming, we carried out extensive transposon mutagenesis of serovar Typhimurium, screening for those that had functional flagella yet were unable to swarm. A majority of these mutants were defective in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) synthesis, a large number were defective in chemotaxis, and some had defects in putative two-component signaling components. While the latter two classes were defective in swarmer cell differentiation, representative LPS mutants were not and could be rescued for swarming by external addition of a biosurfactant. A mutation in waaG (LPS core modification) secreted copious amounts of slime and showed a precocious swarming phenotype. We suggest that the O antigen improves surface “wettability” required for swarm colony expansion, that the LPS core could play a role in slime generation, and that multiple two-component systems cooperate to promote swarmer cell differentiation. The failure to identify specific swarming signals such as amino acids, pH changes, oxygen, iron starvation, increased viscosity, flagellar rotation, or autoinducers leads us to consider a model in which the external slime is itself both the signal and the milieu for swarming motility. The model explains the cell density dependence of the swarming phenomenon.

Several genera of flagellated eubacteria show a behavior known as swarming when propagated on the surfaces of certain solid media (22, 29, 38, 67). Swarming involves flagellum-dependent surface translocation by groups of cells. Swarmer cells are generally longer and more flagellated than cells of the same species propagated in liquid media (swimmer cells). Swarmer cells move within an encasement of slime, a nondescript term for a complex mixture of polysaccharides, surfactants, proteins, and peptides, etc., that surrounds the colony. The morphology of swarmer cells, along with the extracellular slime, probably helps overcome surface friction, favoring rapid expansion of the swarmer colony. In some organisms, the swarmer cell state may be associated with pathogenesis (67, 70).

Although the swarming phenomenon has been described for several bacterial genera, very little is known about the signaling events or signal transduction mechanisms that lead to the production of swarmer cells. The discovery of swarming motility in the well-characterized bacteria Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (39) allows us to use these organisms as model systems for the study of swarming behavior. We have exploited them in three ways in this study. First, extensive transposon mutagenesis was used to identify genes involved in swarming. Second, existing mutants were rationally chosen for testing swarming defects. Third, medium conditions were altered to test for specific chemical signals for promoting swarming.

S. enterica serovar Typhimurium was chosen for transposon mutagenesis because it is less fastidious than E. coli K-12 strains for swarming. Most laboratory strains of E. coli swarm best on media solidified with Japanese Eiken agar, while wild-type serovar Typhimurium can swarm on either Difco or Eiken agar. We have reported earlier that mutants of these two organisms with mutations in the chemotaxis pathway are defective in swarming (39). Here we report the isolation of a large class of conditional mutants that did not swarm on Difco agar but did so on Eiken agar. A large number of these mutants were defective in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) synthesis and many had mutations in genes controlling the physiological state of the cells, while some mutations mapped in putative two-component signaling genes. A swarming model integrating all the current information for S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and E. coli is presented.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, phage, and plasmids.

Bacterial strains, phage and plasmids are listed in Table 1. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain SJW1103 (a fliC-stable derivative of serovar Typhimurium LT2) was the starting strain for all transposon mutagenesis experiments. For TnphoA mutagenesis, SJW1103 was made phoN by transducing phoN::Tn10dtet from MST308 to construct AT190. AT538 was constructed by transducing cheA::Tn10 from KK2051 into SJW1103. SJW2971 is an SJW1103 derivative with a point mutation in motB.

TABLE 1.

Strains, phage, and plasmids

| Strain, phage, or plasmid | Relevant genotype | Source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | ||

| SJW1103 | LT2(fljB-off) Δ(hin-fljAB) | S. Yamaguchi (105) |

| AT538 | SJW1103 cheA::Tn10 | This study |

| SJW2971 | motB | S. Yamaguchi |

| MST308 | LT2 phoN51::Tn10dtet | S. Maloy |

| MST2001 | hisG10085::TnphoA his(H or A)9556::MudP22/pJS28 (gp9-tails) | S. Maloy |

| AT190 | SJW1103 phoN51::Tn10dtet | This study |

| AT527 | SJW1103 luxS::cat | This study |

| KK2051 | LT2 ΔfljAB cheA::Tn10 | K. Kutsukake (52) |

| E. coli | ||

| SM10λpir | recA::RP4-2-Tc::Mu Knr (λpir) | 86 |

| DH5α | Δ(lacIZYA-argF) | |

| φ80dlacΔ(lacZ)M15 | New England Biolabs | |

| RP437 | thr(Am)-1 leuB6 his-4 metF(Am)159 eda-50 rpsL136 thi-1 ara-14 lacY1 mtl-1 xyl-5 tonA31 tsx-78 | J. S. Parkinson |

| V. harveyi | ||

| BB152 | Autoinducer 1−, autoinducer 2+ | B. Bassler (91) |

| BB170 | Sensor 1−, sensor 2+ | B. Bassler (91) |

| Phage and plasmids | ||

| P22 | HT12/4int103 | C. Miller (80) |

| pUC19 | Cloning vector | New England Biolabs |

| pKAS 32 | Suicide vector | K. Skorupski (86) |

| pCHL884 | cat marker | 56 |

pUC19 and DH5α were used for cloning DNA fragments flanking transposon insertions. The suicide vector pKAS32 (86) was used for disruption of luxS.

Media and chemicals.

Swim medium consisted of 0.3% Difco Bacto agar and Gibco BRL L-broth (LB) base (20 g/liter). Swarming bacteria were propagated on either Eiken swarm medium (0.45% Eiken agar, Eiken broth base [20 g/liter], and 0.5% glucose) or Difco swarm medium (0.6% Difco Bacto agar, LB base [20 g/liter], and 0.5% glucose). Minimal swarm medium was made as described previously (3). Both swim and swarm plates were allowed to dry overnight at room temperature before use. Vibrio harveyi was grown in AB medium (34). Antibiotics used were kanamycin (50 μg/ml), ampicillin (100 μg/ml), tetracycline (20 μg/ml), and chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml). The phosphatase activity indicator XP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate) was used at 40 μg/ml.

Eiken products were from Eiken Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan. Bacillus subtilis surfactin, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LPS (L 6511), and mitomycin C were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co.

Transposon mutagenesis using TnphoA and Tn10dCm.

TnphoA was delivered using Mud-P22 phage derived from MST2001 (Table 1). Induction of Mud-P22 and preparation of lysates were as follows (8). A 30-ml culture of MST2001 grown in LB-ampicillin to 5 × 108 CFU/ml at 37°C was induced by the addition of 30 μl of a 2-mg/ml solution of mitomycin C and incubated overnight with shaking. Five milliliters of the overnight culture was treated with 0.5 ml of chloroform and vortexed for 1 min, and the lysate was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 20 min. Chloroform treatment and centrifugation were repeated with the supernatant. TnphoA was delivered by mixing equal volumes of a 10−2 dilution of the lysate with an overnight culture of recipient bacteria. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature, 200 μl of the mixture was plated on LB-kanamycin with XP. Blue colonies are the result of insertions that generate in-frame PhoA fusions to membrane or periplasmic proteins (60). Insertions that do not form such fusions (indicated by white colonies) can be in either membrane or cytoplasmic protein genes.

Tn10dCm was delivered using a P22 lysate (provided by Nick Benson, Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center, San Diego, Calif.) (9, 47) that had been propagated on a pool of serovar Typhimurium colonies containing random Tn10dCm insertions. Equal volumes of a 0.5 × 10−2 dilution of the lysate and an overnight culture of the recipient strain were treated as described above for TnphoA delivery, except that the mixtures were plated on LB-chloramphenicol.

Analysis of swarming defects.

All mutants were screened on swim and Difco swarm media (six per plate) at 37°C to identify those that had functional flagella yet failed to swarm. Defects in flagellar function were identified on swim medium, where an absence of outward migration can be due to defects in synthesis of flagella (Fla−), ability to rotate flagella (Mot−), or chemotactic behavior (Che−). Che− mutants can be visually distinguished from Fla− and Mot− mutants by their fuzzy appearance at the site of inoculation, contrasted to the tight mound of cells formed by other two classes of mutants. The Che− phenotype was confirmed by examination of the mutants in a drop of liquid under a light microscope, where they showed biased running or tumbling behavior.

Swarming mutants other than the Fla− and Mot− mutants were further tested on Eiken swarm medium.

Identification of mutant genes.

Genomic DNA from TnphoA insertion mutants of interest was digested to completion with TaqI. DNA fragments were circularized with T4 DNA ligase and amplified by PCR using Vent polymerase (New England Biolabs) and appropriately designed primers that included phoA sequence. PCR products were cloned into pUC19 and sequenced using one of the amplification primers. DNA sequences linked to phoA were analyzed using the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST program (4), National Center for Biotechnology Information Microbiol Genome Blast databases (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast/unfinishedgenome.html), and Genome Sequencing Center Salmonella Sequencing Project data (www.genome.wustl.edu/gsc/).

Tn10dCm insertions were identified by ligating a 3- to 5-kb size range of a partial TaqI digest of genomic DNA into the AccI site of pUC19, with selection for Cmr. Primers within the cat (chloramphenicol acetyltransferase) gene were used for identifying DNA sequences linked to Tn10 ends, which were analyzed by BLAST searches as described above.

luxS null mutant and activity.

The luxS gene (listed as ygaG in the Salmonella typhi database [www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_typhi/blast_server.shtml]) from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SJW1103 was amplified by PCR and cloned into pUC19. luxS was disrupted by insertion of a cat gene (1.14-kb Klenow-filled XhoI fragment, originally isolated as an HhaI fragment from pCHL884 [Table 1]) into an EcoRV site and cloned into the SacI site of the suicide vector pKAS32. The resulting plasmid was conjugated from SM10λpir into SJW1103, with selection for Cmr. Chromosomal disruption of luxS in AT527 was confirmed by Southern analysis (78). AI-2 activity in cell-free culture fluids (CFCFs) was measured using the reporter strain BB170 as described previously (91) with the following modifications: 0.2 ml of CFCFs was combined with 1.8 ml of BB170 and incubated at 30°C with shaking for 5 h, and then 0.1 ml of the mixture was transferred to a scintillation vial and light production was measured in an SAI Technology integrating photometer (model 3000).

Testing of sensitivity to phage P22.

A 0.1-ml portion of an overnight culture of the tester strain was mixed with 2.5 ml of soft agar (0.5%) and overlaid on 1.5% LB agar plates. Three microliters of a P22 lysate (HT12/4 int 103; 1011 PFU/ml) was spotted on the lawn and incubated at 37°C overnight.

Complementation of swarming defects with LPS and surfactin.

Five-microliter drops of solution containing S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LPS (3.5 mg/ml) or B. subtilis surfactin (10 mg/ml) were spotted directly on Difco swarm medium, allowed to dry, and inoculated with the tester strains. The plates were incubated overnight at appropriate temperatures (37°C for serovar Typhimurium and 30°C for E. coli [E. coli is nonmotile at 37°C]).

Flagellin estimation.

Two hundred microliters of an overnight broth culture was spread on Difco swarm medium. After 5 h of incubation, cells were harvested in LB and the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of each sample was adjusted to approximately 0.7. Equal aliquots (30 μl) of whole-cell samples were boiled (5 min), electrophoresed on sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gels, and subjected to Western blot analysis using cross-reacting anti-Serratia marcescens flagellin antibodies (2). Flagellin bands were quantified using a Bio-Rad densitometer equipped with Multi Analyst software. A similar procedure was followed for broth-grown cells harvested at mid-log phase.

Anaerobic culturing.

Swarm plates were stored in a Forma 1024 anaerobic glove box for at least 5 h to deplete the medium of oxygen. The oxygen-free plates were then inoculated with bacteria grown on swim plates and incubated anaerobically for 17 h. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (tested on Difco and Eiken swarm media) was incubated at 35°C, while E. coli (tested on Eiken swarm media) was incubated at 26°C. An identical set of plates was incubated aerobically.

pH measurements.

pH measurements were done on Eiken swarm medium, with and without 0.5% glucose, and with 0, 50, 100, and 200 mM MES [2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid] buffer. In unbuffered media, an initial pH range of 5 to 8.3 was set by adjusting the pH with either HCl or NaOH. pH readings were taken using an Orion pH microelectrode (model 98-10) connected to a Corning pH meter (model 220). Readings were accurate within 0.05 pH unit. pH measurements of swarm medium were made by inserting the tip of the electrode approximately 1 mm into the agar. pH measurements within a swarming colony were made similarly, except that measurements were taken at approximately 2-mm intervals starting at the perimeter of the colony and moving towards the center. The efficiency of surface colonization under different pH conditions was estimated by measuring the colony radius every 30 min, starting 1 h after inoculation.

RESULTS

Analysis of transposon mutants of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium that are defective in swarming.

Two different transposons were used for mutagenesis. TnphoA allows one to specifically examine insertions in membrane and periplasmic proteins (60). Tn10dCm was used in addition to avoid any insertional bias associated with use of a single transposon. Delivery of transposons and mutant analysis are described in Materials and Methods. Since swarming is dependent on functional flagella, all Fla− mutants (lacking flagella) and Mot− mutants (with nonfunctional flagella) were eliminated from further analysis.

TnphoA mutagenesis generated 5,000 independent blue colonies. Assuming that approximately 10% of the 4,290 open reading frames in E. coli (13) encode membrane proteins, this screen is expected to saturate insertions in all viable and adequately expressed membrane protein-encoding genes of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. Thirty-five mutants which showed normal swimming behavior but did not swarm were identified on Difco swarm medium (Table 2). Preliminary analysis of these mutants showed that 29 were resistant to phage P22, which uses the O antigen as its receptor (24). These mutants were likely to harbor defects in LPS biosynthesis. Twelve of the P22r mutants and all six of the P22s mutants were subjected to sequence analysis. The P22r mutants were all affected in the synthesis or modification of the LPS core and O antigen. Three of the P22s mutants had defects in mdo genes, which are responsible for synthesis of membrane-derived oligosaccharides. The functions of the remaining genes are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

TnphoA screen: Pho+ strains affected in swarminga

| Type of function affected and mutant | Swarming phenotype on:

|

P22 resistanceb | Mutant gene | Functionc | Referenced | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difco medium | Eiken medium | |||||

| Surface or membrane | ||||||

| 11-50 | − | + | r | waaLe | LPS biosynthesis | |

| 41-11 | − | + | r | waaLe | LPS biosynthesis | |

| 42-6 | − | + | r | waaLe | LPS biosynthesis | |

| 44-35 | − | + | r | waaLe | LPS biosynthesis | |

| 47-34 | − | + | r | waaLe | LPS biosynthesis | |

| 46-17 | − | + | r | waaCf | LPS biosynthesis | |

| 2-47 | − | + | r | wbaPe | LPS biosynthesis | |

| 44-28 | − | + | r | wbaPe | LPS biosynthesis | |

| 50-22 | − | + | r | wbaPe | LPS biosynthesis | |

| 57-39 | − | + | r | wzxe | LPS biosynthesis | |

| 15-31 | − | + | r | ddhBe | LPS biosynthesis | |

| 24-9 | − | + | r | ddhBe | LPS biosynthesis | |

| 3-10 | − | + | s | mdoG | MDO biosynthesis | 54 |

| 4-6 | − | + | s | mdoG | MDO biosynthesis | 54 |

| 38-34 | − | + | s | mdoH | MDO biosynthesis | 54 |

| Other | ||||||

| 2-7 | −/+ | + | s | ptsH | PTS pathway | 101 |

| 6-7 | Dpsg | + | s | parB | Virulence plasmid partitioning | 79 |

| 2-44 | − | + | s | yihG | Unknown | 13 |

Five thousand blue colonies were screened. There were 35 swarm-negative mutants, and 18 were sequenced.

r, resistant; s, sensitive.

MDO, membrane-derived oligosaccharides; PTS, phosphotransferase system.

For all unreferenced LPS genes, see reference 73.

LPS O-antigen synthesis.

LPS core synthesis.

Dps, defective in progressive swarming.

To analyze mutants with mutations not confined to membrane proteins, 10,000 white TnphoA colonies and 25,000 Tn10dCm insertions were analyzed. A total of 311 Fla+ mutants from both screens were defective in swarming on Difco swarm medium (Table 3). Of these, 235 were P22r and likely harbored LPS defects (Table 2). Only two of these were sequenced. Another 44 of the mutants were defective in chemotaxis. Che− mutants were not sequenced, since the swarming defects of che mutants of both serovar Typhimurium and E. coli have already been reported (39), and detailed analysis of these mutants will be presented elsewhere (A. Toguchi and R. M. Harshey, unpublished data). Sequence analysis of the remaining mutants is shown in Table 3. Several mutations were in genes for cellular metabolism and for membrane components, while three were in members of two-component regulatory systems of unknown function. We note that except for hisD, all mutations in Table 3 were isolated only once. It is possible that multiple insertions in hisD are related to a TnphoA hot spot.

TABLE 3.

TnphoA and Tn10dCm swarming mutantsa

| Type of function affected and mutantb | Swarming phenotype on:

|

P22 resistancec | Mutant gened | Function | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difco medium | Eiken medium | |||||

| Metabolism | ||||||

| 8-11* | − | + | s | hisD | Histidine biosynthesis | 19 |

| 17-7* | − | + | s | hisD | Histidine biosynthesis | 19 |

| 64-7* | − | + | s | hisD | Histidine biosynthesis | 19 |

| 16-48* | − | + | s | cybC | Cytochrome synthesis | 96 |

| L6-393 | − | + | s | dhnA | Carbohydrate metabolism | 94 |

| S28-14 | − | + | s | purH | Purine biosynthesis | 20 |

| S122-27 | − | + | s | iadA | Peptide metabolism | 30 |

| M151-44 | − | + | s | fadH | Fatty acid metabolism | 106 |

| M176-16 | − | + | s | fdhF | Formate metabolism | 104 |

| Surface or membrane | ||||||

| 16-6* | − | + | s | wcaK | Capsular polysaccharide region | 87 |

| AF20* | − | + | r | waaKe | LPS biosynthesis | 73 |

| 58-19* | − | + | r | waaPe | LPS biosynthesis | 73 |

| L9-50 | − | + | s | shdA | Similar to adhesin | GenBank accession no. AF140550 |

| S82-3 | − | + | s | ompS1 | Outer membrane protein | 25 |

| S126-45 | − | + | s | sfiX | Cell wall biosynthesis | 27 |

| M17-48 | − | + | s | marA | Membrane permeability | 90 |

| M210-43 | − | + | s | corA | Magnesium transport | 43 |

| Signaling | ||||||

| L5-192 | − | + | s | baeS | Sensor kinase | 68 |

| M208-35 | − | + | s | yfhK | Putative sensor kinase | 13 |

| S28-31 | − | + | s | yojN | Putative sensor kinase | 13 |

| Other | ||||||

| L5-225 | − | + | s | xerC | Chromosome segregation | 12 |

| M112-47 | − | + | s | ydhC | Unknown | 21 |

| M153-43 | − | + | s | yihP | Unknown | 13 |

| M156-250 | − | + | s | ybeS | Unknown | 13 |

| M17-39 | − | + | s | yehE | Unknown | 13 |

| L7-85 | − | + | s | UN-1 | ||

| S71-32 | − | + | s | UN-1 | ||

| S80-24 | − | + | s | UN-2 | ||

| S116-25 | − | + | s | UN-2 | ||

| S118-35 | − | + | s | UN-1 | ||

| M16-43 | − | + | s | UN-1 | ||

| M156-29 | − | + | s | UN-2 | ||

| M209-40 | − | + | s | UN-1 | ||

A total of 35,000 mutants (10,000 TnphoA and 25,000 Tn10dCm) were screened. There were 311 swarm-negative mutants (235 LPS, 44 Che, and 32 others), and 34 were sequenced.

Asterisks indicate TnphoA insertions; all others have Tn10dCm insertions.

r, resistant; s, sensitive

UN-1 and UN-2, contiguous sequences (contigs) identified in the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (Washington University) and S. typhi (BLAST) unfinished genome databases, respectively.

LPS core modification.

Testing of known mutants for swarming defects.

Since most of the isolated transposon mutations were recovered only once (Table 3), we thought it also prudent to test several defined mutations in both S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and E. coli that could be expected to affect swarming, based either on known requirements for these genes in other bacteria that show surface motility (e.g., fliL, lrp, pepQ, and flgN in Proteus mirabilis; lon in Vibrio parahaemolyticus; the luxR homologue sdiA [due to involvement of homoserine lactone autoinducer] in Serratia liquifaciens; and fim [due to requirement for fimbrae] in Myxococcus xanthus) or on their effects on physiological functions, including environmental sensing, signaling, gene activation, or possibly intercellular interactions, that might be reasonably expected to affect swarming. The data are presented in Table 4. No obvious defects were observed except for ntrA and CL79 in serovar Typhimurium, which showed a Dps phenotype. A Dps (for defective in progressive swarming) phenotype is one in which movement is restricted to the area of inoculation. This is likely the result of an absence of surface-active compounds that promote colony expansion (61, 69). ntrA (encoding sigma 54) is involved in nitrogen regulation but is also known to regulate other physiological functions, such as anaerobic metabolism (11) and flagellar regulation in Campylobacter coli and Vibrio cholerae (46, 48). The phenotype of CL79 is harder to understand since it carries a MudJ insertion in a non-open-reading-frame region of the virulence plasmid pSLT and since the absence of pSLT had no effect on swarming (Table 4). We note that a mutation in parB, which regulates, but is not essential for, partitioning of pSLT, also showed a Dps phenotype (Table 2). Defined LPS mutants are discussed separately below.

TABLE 4.

Potential nonswarming mutant candidates

| Species | Mutant gene | Swarming phenotype on:

|

Function | Source (reference[s]) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difco medium | Eiken medium | ||||

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | fliL | + | + | Flagellar biosynthesis | R. Macnab (6, 74) |

| flgM | + | + | Flagellar biosynthesis | K. Hughes (31) | |

| flgN | + | + | Flagellar biosynthesis | K. Hughes (35, 53) | |

| pepQ | + | + | Aminopeptidase | C. Miller (6, 66) | |

| lon | + | + | Protease | SGSCa (33, 88) | |

| sirA | + | + | Response regulator | B. Ahmer (45) | |

| ntrA | Dpsb | + | Sigma-54 | S. Kustu (42, 46, 48) | |

| fnr | + | + | Anaerobic regulator | C. Miller (82) | |

| rck | + | + | Adhesin | B. Ahmer (41) | |

| CL79 | Dps | + | MudJ insertion in virulence plasmid, pSLT | B. Ahmer (1) | |

| pSLT(−) | + | + | Cured of pSLT | B. Ahmer (79) | |

| sdiA | + | + | luxR homologue | B. Ahmer (100) | |

| luxS | + | + | AI-2 synthase | This study | |

| Wild type | + | + | SGSC SL3770 | ||

| waaLc | − | + | LPS biosynthesis | SGSC SL3749 | |

| waaKd | − | + | LPS biosynthesis | SGSC SL733 | |

| waaTe | − | + | LPS biosynthesis | SGSC SL3750 | |

| waaGe | + | + | LPS biosynthesis | SGSC SL3769 | |

| waaFe | − | + | LPS biosynthesis | SGSC SL3789 | |

| waaEe | − | + | LPS biosynthesis | SGSC SL1102 | |

| waaPd | − | + | LPS biosynthesis | SGSC SH7770 | |

| galEe | + | + | LPS biosynthesis | SGSC SL1306 | |

| E. coli | lrp | NTf | + | Transcriptional regulator | J. Calvo (18, 40) |

| ompR | NT | + | Response regulator | T. Silhavy (28) | |

| rpoS | NT | + | Sigma-S | D. Siegele (55) | |

| fur | NT | + | Transcriptional regulator | S. Payne (37) | |

| cadB | NT | + | Lysine/cadaverine antiporter | G. Bennett (64) | |

| envZ | NT | + | Sensor kinase | T. Silhavy (28) | |

| tonB | NT | + | Energy transducer | K. Postle (72) | |

| aer | NT | + | O2 chemoreceptor | J. Parkinson (10) | |

| tsr-aer | NT | + | Serine and O2 chemoreceptors | B. Taylor (76) | |

| kdpD | NT | + | Sensor kinase | T. Mizuno (98) | |

| mscL | NT | + | Mechanosensitive channel | C. Kung (89) | |

| fim | NT | + | Type 1 fimbrae | I. Blomfield (14) | |

SGSC, Salmonella Genetic Stock Center.

Dps, defective in progressive swarming.

LPS O-antigen synthesis.

LPS core modification.

LPS core synthesis.

NT, not tested because E. coli K-12 strains swarm only on Eiken agar.

Effect of luxS disruption on swarming.

In S. liquefaciens, a homoserine lactone autoinducer plays an important role in swarming (23) by controlling the production of the surfactant serrawettin (57). Recently E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium were shown to produce another type of autoinducer (AI-2), and a gene, luxS, homologous to the AI-2 synthase gene from V. harveyi was identified as being responsible for its synthesis (92, 93). To test whether AI-2 plays a role in serovar Typhimurium swarming, luxS was disrupted (see Materials and Methods). To ascertain that AI-2 synthesis was abolished in the resulting mutant, AT527 (Table 1), CFCFs were assayed using the V. harveyi reporter strain BB170 as described in Materials and Methods. CFCFs from the AI-2 positive (BB152) and AI-2 negative (DH5α) control strains generated approximately 8,500 and 100 arbitrary light units, respectively, while those from wild-type serovar Typhimurium (SJW1103) and its luxS derivative (AT527) produced 23,000 and 100 arbitrary light units, respectively (data not shown). Thus, AI-2 production is indeed abolished in the luxS mutant AT527. However, swarming was unaffected in this mutant (Table 4), showing that luxS was not required for swarming under these conditions.

Flagellin upregulation in LPS mutants: rescue of swarming with external surfactin.

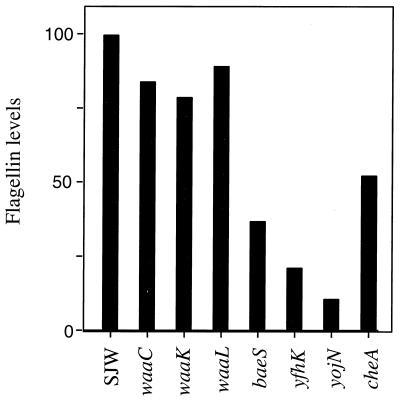

Since a large number of the transposon mutants isolated in this study had mutations that mapped to the LPS biosynthetic pathway, we chose representative waa mutants affected in O-antigen synthesis (waaL mutant 41-11), core synthesis (waaC mutant), and core modification (waaK mutant) (Tables 2 and 3) for characterization. Flagellin upregulation was used as a marker for swarmer cell differentiation. When propagated on swarm medium, the LPS mutants had flagellin induction levels comparable to that of the wild type, suggesting that their inability to swarm on Difco medium was not due to signaling defects that interfered with regulating flagellar synthesis (Fig. 1). All LPS mutants showed normal motility on swim plates, suggesting that they did not harbor flagellar assembly defects. Elongation defects were not characterized, because this phenotype is not as dramatic in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium as it is in other organisms. No gross defects were obvious.

FIG. 1.

Flagellin levels in representative swarming mutants propagated on swarm medium. A wild-type strain (SJW1103 [SJW]) and the indicated mutants were grown on swarm medium for 5 h and harvested as described in Materials and Methods. Flagellin amounts in OD600-equalized aliquots of cells were analyzed by Western blotting followed by densitometry. Flagellin levels (arbitrary densitometry units) were normalized to 100 for the wild-type strain. Results from one experiment are shown. Absolute flagellin values differed in several repititions of the experiment, but the trend was very reproducible.

Like the LPS mutants (Tables 2 and 3), a large number of S. marcescens mutants that were swarming defective on Difco swarm medium (69) could swarm if the agar used to solidify the medium was obtained from a Japanese commercial source (Eiken agar) (61). We have also reported that E. coli K-12 strains swarm only on Eiken swarm medium (39). Since several of the S. marcescens mutants that could swarm only on Eiken medium were defective in production of the biosurfactant serrawettin (61), we reasoned that Eiken agar may perhaps provide a more “wettable” surface. To test if the hydrophilic O antigen provides a similar function, representative mutants were inoculated on Difco swarm medium and exposed to a biosurfactant (surfactin) from B. subtilis, as well as commercially available serovar Typhimurium LPS.

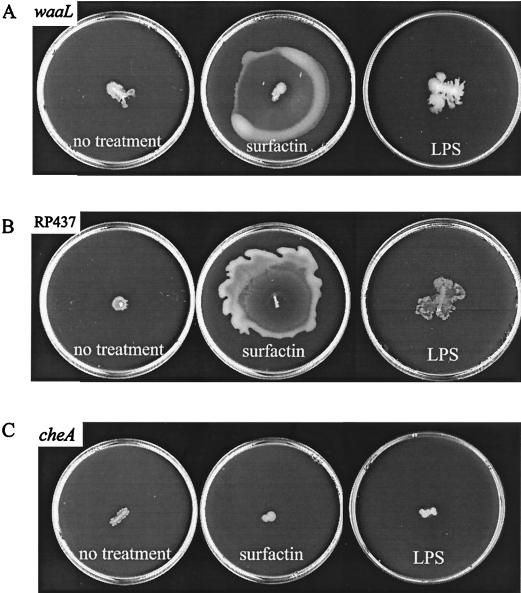

Figure 2A shows that an waaL mutant lacking O antigen (41-11) (Table 2) was rescued for swarming by surfactin but was rescued only poorly with external LPS. E. coli strain RP437, which lacks O antigen (58) and can swarm only on Eiken medium (39), showed a similar response (Fig. 2B). Neither surfactin nor LPS stimulated swarming of a cheA mutant (Fig. 2C). It is not clear why addition of LPS was not as effective as addition of surfactin. This may be due to the presence of associated impurities in the commercially obtained LPS or because the right concentrations of LPS were not achieved. Alternatively, the O antigen may function best only when covalently attached to the cell or when naturally discharged.

FIG. 2.

Rescue of swarming defects with external addition of surfactin and LPS. Five-microliter drops of solution containing surfactin or LPS were placed at the center of 0.5% Difco swarm medium, inoculated with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (waaL and cheA) and E. coli (RP437) strains, and incubated overnight as described in Materials and Methods.

The rescue of LPS mutants with surfactin is consistent with the notion that the O antigen may provide a surfactant or wettability function during swarming. Also, Eiken swarm medium likely promotes swarming by a similar mechanism in the mutants isolated in this study, suggesting that a large number of genes contribute to generating requisite external surface conditions for swarming.

Precocious swarming phenotype of an LPS core mutant.

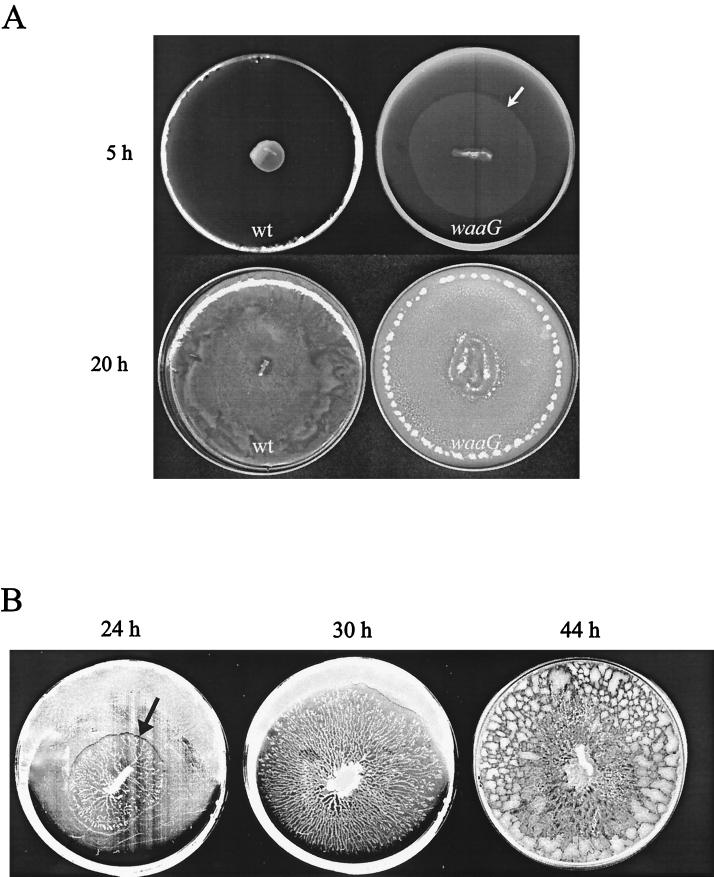

Given that the majority of the swarming mutants harbored LPS defects (Tables 2 and 3), we also tested the swarming abilities of a collection of known LPS mutants obtained from the Salmonella Genetic Stock Center (Table 4). While most of these mutants also showed conditional defects, one mutant (the waaG mutant) swarmed earlier and faster than its wild-type parent on Difco swarm medium and secreted copious amounts of slime (Fig. 3). The growth rates of the waaG mutant and its wild-type parent were comparable. After 5 h of incubation, while the wild-type strain had just begun outward progression, the waaG strain had swarmed over half of the plate (Fig. 3A). This mutant can be described as a precocious swarmer (7). The swarming pattern of the waaG colony was unusual in that the cells swarmed in a monolayer (observed microscopically; the arrow in Fig. 3 points to the swarming front), in contrast to a wild-type colony, which is several layers thick. However, by the time the wild-type front had covered the plate, the waaG colony had grown denser than the wild-type colony and was very rough in appearance. The slime on the plate was so plentiful that the whole colony could slide off the plate as a mat upon tilting. (The circular pattern of dots near the edge of the 20-h waaG colony is not reproducible and is likely related to the rough nature of the mat.) This mutant was also able to swarm on minimal medium (Fig. 3B), which does not support swarming of wild-type S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (see below). On minimal medium, swarming was initiated with a delay of about 20 h. Interestingly, although a slime ring was clearly visible as a circular halo around the waaG colony propagated on minimal medium, the path of the swarming cells within this slime was highly branched. We were unable to determine if flagellin expression was constitutively upregulated in this mutant, because the cells aggregated easily in broth, lysed readily, and resisted Western blotting (likely due to the slime).

FIG. 3.

Precocious swarming of waaG LPS core mutant. (A) A wild-type (wt) S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain (SL3770) and its waaG mutant derivative (SL3769) were inoculated on Difco Bacto swarm medium and incubated at 37°C. Photographs were taken after 5 and 20 h of incubation. The arrow points to edge of the waaG swarm colony. (B) The waaG strain was inoculated on minimal swarm medium and incubated at 37°C. Photographs were taken after 24, 30, and 44 h. The arrow indicates edge of the slime ring. Swarming movement was confined to regions that appear as branches emanating from the center.

Flagellin induction in baeS, yfhK, and yojN mutants.

To test if the three putative two-component signaling baeS, yfhK, and yojN mutants (Table 3) were defective in swarmer cell differentiation, flagellin levels in these cells on swarm medium were estimated as described for the waa mutants (Fig. 1). Compared to the wild type, all three mutants appeared defective in flagellin induction on swarm medium. A representative che mutant (cheA, encoding the central kinase) was also defective in flagellin induction, consistent with flagellar staining data of Che− mutants reported earlier (16).

Signals for swarming.

It is apparent from the results presented above that external surface conditions play an important role during swarming. At the very least, the milieu or slime elaborated by a swarmer colony must provide the aqueous environment within which cells must rotate their flagella in order to effect movement and allow swarm colony expansion. It is likely that the O antigen or surfactants contribute to such an environment. The slime may also be expected to harbor signals for swarmer cell development, and the two-component signaling systems could be involved in both slime generation and signal detection. Since known autoinducer systems are not required and little is known about the putative baeS, yfhK, and yojN two-component systems, we tested known chemotaxis signals since the che genes are essential for swarming (16, 39, 69). We also tested whether slowed flagellar rotation, the favored model for signaling in V. parahaemolyticus swarmer cell differentiation (62), was required for swarming in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium.

(i) Amino acids were examined for the following reasons: (a) serovar Typhimurium and E. coli do not swarm on minimal media (39); (b) the chemoreceptor Tsr or Tar, whose ligands include amino acids, is essential for swarming in E. coli, but recognition of their cognate amino acids (serine and aspartate) is not required (16); (c) glutamine has been reported to be a signal in P. mirabilis differentiation (3); (d) a mixture of a subset of amino acids is required for signaling in M. xanthus fruiting body formation (50); and (e) the slime may contain a mixture of amino acids and peptides in addition to polysaccharides. We observed that on minimal glucose swarm medium, flagellin synthesis was less than 10% of that on Difco swarm medium, and that only the addition of all 20 amino acids (or Casamino Acids), and not that of single amino acids or subsets of chemically similar amino acids, allowed swarming (data not shown) (39). The requirement for a full complement of amino acids may be due to general metabolic reasons rather than the absence of a specific amino acid signal.

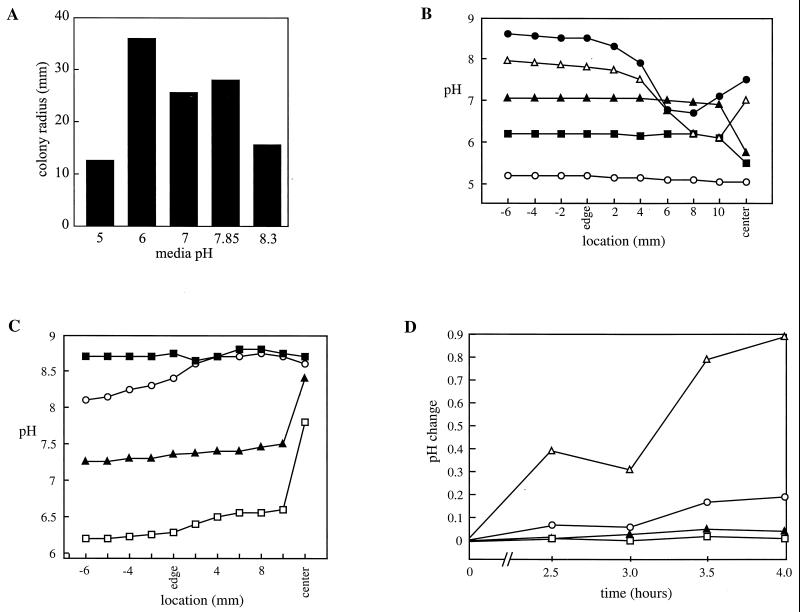

(ii) pH changes were examined because Tsr and Tar are known to be pH sensors (49). Outward swarming migration is initiated a few hours after inoculation of broth-grown cells onto appropriate swarm medium, at a time when the colony has reached a confluent cell density. pH gradients are known to develop in and around a surface-grown colony (99). Apart from some early studies on Vibrio alginolyticus (97), there is no information to date about pH changes within swarming colonies of any bacterial genera. We have therefore examined these in some detail. First, we determined the pH optima for S. enterica serovar Typhimurium on Eiken swarm medium set at five different pH values (5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 7.85, and 8.3) at 37°C. Maximum swarming efficiency was observed on medium set at an initial pH of 6, while swarming on medium with initial pH values of 5.0 and 8.3 was approximately three- and twofold reduced, respectively (Fig. 4A). By the use of a pH microelectrode, we found that on Eiken swarm medium containing 0.5% glucose, the pH stayed close to the initial pH of the medium (5.2, 6.2, 7.0, 8.0, and 8.6) near the edge of the swarm colony (Fig. 4B). However, the pH levels near the center of the swarm colony tended to drop to lower values (presumably due to sugar fermentation) compared to those on glucose-free medium (Fig. 4C). We conclude from these data that swarming initiates and progresses over a wide pH range (between 5.0 to 8.7), with an optimal pH of about 6.

FIG. 4.

pH experiments. (A) SJW1103 was inoculated on Eiken swarm medium preset to different pH values, and colony radii were measured after overnight incubation. (B) SJW1103 was inoculated on Eiken swarm medium (with 0.5% glucose) preset to five different pH values (○, 5.2; ■, 6.2; ▴, 7.0; ▵, 8.0; ●, 8.6). pH measurements were taken with a microelectrode 8 h after inoculation. Positive x-axis numbers indicate distance (in millimeters) within the swarming colony, and negative numbers indicate distance outside the colony. (C) Same as panel B, except with Eiken swarm medium without glucose. The initial pHs of the media were 6.2 (□), 7.2 (▴), 8.0 (○), and 8.7 (■). (D) SJW1103 was inoculated on Eiken swarm medium without glucose and buffered with different MES concentrations (▵, 0 mM MES; ○, 50 mM MES; ▴, 100 mM MES; □, 200 mM MES). The pH at the center of inoculation was measured at the indicated times. The pH change displayed on the y axis is in tenths of a pH unit above the starting pH of 6.1. The results displayed in all panels were highly reproducible.

To test whether transient changes in extracellular pH might serve as signals for induction of swarming, the optimal swarm media (pH ∼6.0) was buffered with 50 to 200 mM MES. pH measurements were taken immediately after inoculation of 2 μl of an overnight culture of serovar Typhimurium at the center of the plate and at 30-min intervals at the same spot during incubation at 37°C (Fig. 4D). MES at 100 and 200 mM prevented any significant pH change within the colony throughout the experiment. Swarming initiated at approximately 2.5 h and progressed normally in all four cases (not shown). Thus, an extracellular pH change is not required to initiate swarming motility in serovar Typhimurium.

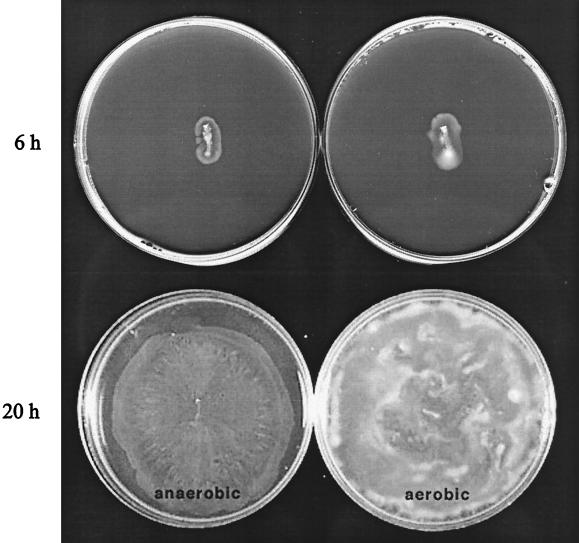

(iii) The O2 requirement was tested because Tsr has been shown to be an important constituent of the response to oxygen (10, 76). In addition, there is no information regarding the swarming ability of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (a facultative anaerobe) under anaerobic conditions. In an aerobically grown colony, oxygen levels are drastically decreased towards the center and bottom (102). To see if a change in oxygen level or the creation of an oxygen gradient is required for swarming, we examined the efficiency of swarming in aerobic versus anaerobic environments. Swarming initiated at approximately the same time under both conditions and cell densities were similar for the first several hours of outward migration (Fig. 5, 6 h). The aerobic colony, however, achieved a higher final cell density and seemed to progress at a slightly higher rate (Fig. 5, 20 h). Characteristic pack movement of cells could be observed microscopically under both conditions. Similar results were obtained for E. coli (data not shown). Thus, oxygen is not essential for swarming. These results are consistent with our observation that a mutation in aer, the newly discovered oxygen sensor gene, had no effect on swarming under aerobic conditions (Table 4).

FIG. 5.

Effect of anaerobiosis on swarming. SJW1103 was grown on Difco swarm medium either anaerobically (left) or aerobically (right) as described in Materials and Methods and photographed after 6 and 20 h.

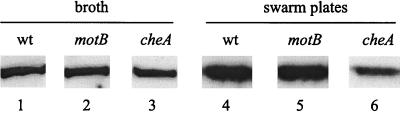

(iv) Mot (paralyzed motor) mutants of V. parahaemolyticus are constitutively induced for lateral flagellum expression (62). To test if the flagellar motor plays a similar role in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, we tested a motB mutant (SJW2971) in broth and on swarm medium (Fig. 6). The flagellin levels of this mutant were similar to those of the wild-type strain in broth (Fig. 6, compare lanes 1 and 2). Like the wild type, the motB mutant also showed upregulation of flagellin on swarm medium (Fig. 6, compare lanes 4 and 5), while the negative control cheA mutant (Fig. 1) did not (Fig. 6, compare lane 3 with lane 1 and lane 6 with lane 4). Several motB and motA mutants of E. coli were also examined. The motB mutants showed normal flagellin levels in broth and higher flagellin induction on swarm medium compared to wild-type bacteria, while motA mutants showed wild-type induction levels (data not shown). The normal surface-specific upregulation of flagellin by the Mot mutants leads to us to conclude that flagellar rotation is not the primary determinant of signaling in the swarming response of serovar Typhimurium and E. coli.

FIG. 6.

Flagellin levels in a Mot− mutant in broth and in swarm medium. Cultures of the indicated strains were grown either in LB broth or on Difco swarm medium as described in Materials and Methods. Aliquots of OD600-equalized cells were analyzed by Western blotting using antiflagellin antibodies as described in Materials and Methods.

(v) We also tested viscosity and iron starvation as possible signals, since these affect swarmer cell differentiation in V. parahaemolyticus (63). While iron starvation did not affect flagellin expression (95), increased viscosity (with 10% Ficoll) produced a two- to threefold increase both in wild-type S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and in mutants with paralyzed motors (95). All of the two-component signaling mutants (cheA, baeS, yfhK, and yojN mutants) also upregulated flagellar synthesis in response to Ficoll (data not shown). The relevance of the Ficoll response to swarm cell signaling is therefore unclear at present.

DISCUSSION

The overall picture emerging from our large-scale search for genes and signals governing swarming motility in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium is that important functions are performed by the LPS layer and the slime and that both known and putative two-component systems play a role in swarming. We have eliminated known autoinducer systems, specific amino acids, pH changes, oxygen, iron starvation, viscosity, and flagellar rotation as primary signals. We will consider an alternate signaling model below.

Role of LPS in swarming.

All LPS mutants isolated in this study showed conditional swarming defects in that they were defective for swarming on Difco Bacto swarm medium but not on Eiken swarm medium. In an earlier study with S. marcescens (69), we reported that mutants unable to make the surfactant serrawettin displayed a similar conditional swarming defect (61). Given that Eiken agar can overcome surfactant defects, we surmised that the permissive quality of this agar may be due to some parameter (such as superior wettability, for example) that affects the surface. The rescue of a wide spectrum of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium mutants on Eiken swarm medium (Tables 2 to 4) argues against a specific chemical component in the medium that is responsible. This view is also supported by our inability to demonstrate a dialyzable constituent in the Eiken agar that promotes swarming on Difco Bacto agar (our unpublished results). It is more reasonable to imagine that all of the conditional mutants are ultimately altered either in their ability to elaborate wetting agents or in some property of the cell surface that hinders surface translocation. The ability of surfactin, which lowers surface tension and improves wettability, to support swarming of the LPS mutants isolated in this study (Fig. 2) is consistent with the notion that Eiken agar provides a more wettable surface.

E. coli K-12 strains are phenotypically rough, having a complete core structure but no O antigen (58). Like the serovar Typhimurium LPS mutants (Fig. 1), E. coli strains are not defective in upregulating flagellar expression (39) and could swarm on Difco swarm medium with added surfactin (Fig. 2). E. coli with an intact O antigen can swarm on Difco swarm medium (39). These results suggest that the O antigen is directly or indirectly involved in increasing the wettability of the swarming surface. Direct effects might including increased hydration of the cell surface by the hydrophilic O antigen (73). It is possible that LPS is converted to exopolysaccharide during swarming, and contributes to the external slime. O-antigen sloughing has been reported for Pseudomonas aeruginosa (17) and has been observed by us in serovar Typhimurium as well (data not shown). Exopolysaccharide from P. aeruginosa has been shown to absorb large amounts of water (77). Indirect effects might include facilitating the secretion of polysaccharides or other compounds that increase wettability (see below) (65). A hydrated shell around the swarming colony would be essential for flagellar rotation.

Besides increasing cell hydration, a second role for LPS is suggested by the behavior of an LPS core modification mutant, the waaG mutant (Table 4), which showed a precocious swarming phenotype and appeared to be making copious amounts of slime (Fig. 3). Slime production by this mutant is in keeping with the reported phenotype of a waaG deletion mutant of E. coli, which was found to induce colanic acid capsular polysaccharide synthesis via stimulation of the two-component signal transduction system RcsB and RcsC (71). Interestingly, precocious swarming mutants of P. mirabilis have mutations that map to rsbA, a gene located next to homologues of rcsB and rcsC, as well as to rcsC (7). The wcaK mutant is defective in a gene which also maps in the capsular polysaccharide region (Table 3). It is possible that in a colony of wild-type cells, changes in O-antigen content or intercellular interactions fostered via O antigens lead to alterations in the LPS core which in turn induce the secretion of various surface-active molecules. The precocious waaG core mutant might be considered to be constitutively induced for slime production.

The importance of the LPS O antigen in other surface phenomena includes swarming motility in P. mirabilis (6) and social motility and multicellular development in M. xanthus (15). Mutation of a gene in P. mirabilis related to the putative sugar transferases required for LPS core modification in Shigella and Salmonella (waaK) was reported not to affect swarm cell differentiation but to abolish production of a surface capsular polysaccharide, diminish surface translocation, and attenuate the ability of P. mirabilis to establish experimental urinary tract infection (36). This defect could be extracellularly complemented by wild-type bacteria, similar to the conditional phenotype of the LPS mutants reported in this study, which included a waaK mutant (Table 3). LPS is also important in biofilm formation and virulence of P. aeruginosa (32), and absence of the O antigen is known to attenuate or abolish virulence in many pathogenic bacteria (26, 44).

Defects in putative two-component signaling systems.

In contrast to the LPS mutants, swarming mutants with homology to two-component signaling systems (baeS, yfhK, and yojN mutants) were all defective in flagellin induction, similar to the defect in the known cheA signaling mutant (Fig. 1). Thus, multiple signaling systems appear to participate in swarmer cell differentiation. Preliminary results indicate that the ability of baeS, yfhK, and yojN mutants to swarm on Eiken agar is not due to induction of swarmer cell differentiation but likely is due to lower surface tension of this substrate that allows surface colonization without having to upregulate flagellar expression (data not shown).

Among the two-component genes, the yojN mutant deserves comment. yojN shares homology with rsbA of P. mirabilis (7); the precocious behavior of rsbA mutants was discussed above. The S. enterica Typhimurium yojN mutant, however, was not precocious. It is not clear whether the difference in the phenotype of the yojN and rsbA mutants in the two organisms is due to the different positions of the transposon insertions (7, 84) or to differences in their function. Belas et al. (7) have suggested that the rsbA and yojN products might be involved in cell density sensing, because of their homology to the sensory proteins LuxQ from V. harveyi (involved in cell density sensing via the AI-2 pathway) and EvgS from E. coli (involved in sensing low temperature, MgSO4, and nicotinic acid). Cell density sensing is discussed in a separate section below.

The baeS gene was identified by Nagasawa et al. (68) as the sensor kinase member of the two-component signal transduction genes in E. coli by a random screen for recombinant plasmids that were able to phenotypically suppress mutational lesions of both the envZ and phoR/creC genes, each of which encodes a well-characterized sensory kinase. The BaeS protein was demonstrated to exhibit a phosphotransfer reaction in vitro in the presence of ATP (68). The specific cellular function of this gene is not known. The yfhK gene (Table 3) also has homology to membrane sensor protein genes, and no specific function has yet been assigned to this gene either.

Autoinducers and other signals in swarming.

Since swarming is not initiated for several hours after inoculation, at which time the colony has reached a confluent cell density, it is reasonable to expect quorum sensing to play a role at some stage in the process. In gram-negative bacteria, two varieties of autoinducers have been identified as cell density signals or quorum sensors (93). Acyl-homserine lactones (HSLs or AI-1) are elaborated by the LuxI-LuxR family of proteins (LuxI is the HSL synthase and LuxR is the transcriptional activator protein that binds to the HSL). HSLs play a role in the swarming response of Serratia. The target genes regulated by this quorum-sensing system are involved in synthesis of the biosurfactant serrawettin (57). In S. liquefaciens, mutations in swrI (encoding HSL synthase) reduce swarming (23). It is important to note, however, that like the LPS mutations described in this study, mutations in the quorum-sensing pathway that produces serrawettin in both S. marcescens and S. liquefaciens do not interfere with swarm cell differentiation and motility but interfere only with swarm colony expansion (57, 69). Thus, serrawettin itself is not the signal for swarm cell differentiation in these organisms.

Although there is no evidence to suggest that HSLs are synthesized by E. coli or S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, externally added HSLs activate sdiA (a luxR homologue) in serovar Typhimurium (85). However, mutation of sdiA did not affect swarming (Table 4). A second class of autoinducers, AI-2, has been recently described for V. harveyi, E. coli, and serovar Typhimurium (93). While the structure of this non-HSL compound is not yet known, its synthesis is dependent on the luxS gene (93). Disruption of this gene (Table 1) also had no effect on swarming (Table 4). Thus, either the genes regulated by these cell density-sensing systems are not involved in swarming in serovar Typhimurium or other gene products compensate in their absence.

Several environmental conditions (amino acids, pH, oxygen, iron, and viscosity) were examined as potential signals, using increased flagellin production as a marker for the swarmer cell state in some experiments. We ruled out specific amino acids, iron starvation, or increased medium viscosity as relevant signals (data not shown) (95). Neither buffering of medium against pH changes nor lack of oxygen had any pronounced effect on swarming motility (Fig. 4 and 5). We also showed that a rotating flagellum is not necessary for flagellar induction (Fig. 6).

Model for cell density sensing and signaling during S. enterica serovar Typhimurium swarming.

It is apparent that a large number of genes function to ensure external surface conditions (slime) that improve wettability and facilitate expansion of the swarming colony. It is possible that the nonswarming phenotype of mutants with mutations in various metabolic pathways (Table 3) is related to this function. In light of our elimination of many of the obvious candidates for signals, we suggest not only that the external slime plays a critical role in swarm colony expansion but also that polysaccharides in the slime constitute a signal for swarmer cell differentiation. A polysaccharide signal might act by altering external water activity, which may cause changes in physical characteristics of the membranes or periplasmic space where the chemoreceptors required for swarm signaling are located. The isolation of defects in the mdo genes (which synthesize branched glucans found in the periplasm), membrane functions, and several two-component signaling systems may be relevant in this regard. While this suggestion seems to implicate osmolarity as the signal, we note that the known osmolarity sensors EnvZ and Kdp are apparently not essential for swarming (Table 4). Changes in osmolarity (achieved by varying external NaCl or sucrose concentrations) are known to regulate flagellar expression through the EnvZ pathway in E. coli (83) but not to affect flagellar expression in serovar Typhimurium (51). Interestingly, the RcsB-RcsC signaling pathway is reported to influence flagellin expression in response to osmolarity in S. typhi (5). Given that we still do not know the molecular nature of the osmolarity signal in well-studied osmosensing pathways (103), it is difficult for us to suggest how the slime polysaccharide signal would operate. Our understanding of the structure of the periplasm is also very tenuous. It is possible that the polar localization of chemoreceptors (59) may position them to function as specialized osmosensors, detecting gradual rather than sudden shifts in water activity during swarming.

The model considered above, where the slime is both the signal and also the swarming milieu, can explain the cell density dependence of swarming (references 22 and 29 and our unpublished results). In this model, slime buildup is initially constitutive. Multiple sources of polysaccharides (O-antigen sloughing, low-level capsular polysaccharide synthesis, and glycolipid secretion) contribute to this initial slime, whose accumulation is dependent on cell metabolism and growth. Cell-cell interactions within this colony eventually lead to changes in the LPS core that signal (via two-component systems) the secretion of more polysaccharides, which elicit swarmer cell differentiation (via other two-component systems). The concentration of the polysaccharide signal in the slime is thus directly related to cell density. The precocious behavior of the slime-secreting waaG mutant (Fig. 3), which initiates swarming at a lower cell density than the wild type, is consistent with this notion. The model can also explain the generation of regularly spaced concentric zones formed during P. mirabilis swarming (81), where age-weighted swarmer cell density has been postulated as the key determinant of the beginning and ending phases of swarming (75). As swarmer cells move out, they carry the slime with them, thus depleting the signal from the center and diluting it from the edge of the colony. The consolidation phase and the second wave of swarming emanating from the center can both be explained by reaccumulation of the slime and signal in a time-dependent (and hence age-dependent) manner.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Scott Stratemann, Kim Simpson, Joe Robert Mireles, and Hui-Yong Chung for providing undergraduate research help at various stages of this project, Suzanne Barth at the Texas Department of Health for use of the anaerobic chamber, all of our colleagues who supplied us with strains and plasmids, Mike Manson for advice, and Elizabeth Wyckoff for critical comments on the manuscript.

This work received support from NIH grant GM57400.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmer B M, van Reeuwijk J, Timmers C D, Valentine P J, Heffron F. Salmonella typhimurium encodes an SdiA homolog, a putative quorum sensor of the LuxR family, that regulates genes on the virulence plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1185–1193. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1185-1193.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberti L, Harshey R M. Differentiation of Serratia marcescens 274 into swimmer and swarmer cells. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4322–4328. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4322-4328.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison C, Lai H C, Gygi D, Hughes C. Cell differentiation of Proteus mirabilis is initiated by glutamine, a specific chemoattractant for swarming cells. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arricau N, Hermant D, Waxin H, Ecobichon C, Duffey P S, Popoff M Y. The RcsB-RcsC regulatory system of Salmonella typhi differentially modulates the expression of invasion proteins, flagellin and Vi antigen in response to osmolarity. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:835–850. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belas R, Goldman M, Ashliman K. Genetic analysis of Proteus mirabilis mutants defective in swarmer cell elongation. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:823–828. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.823-828.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belas R, Schneider R, Melch M. Characterization of Proteus mirabilis precocious swarming mutants: identification of rsbA, encoding a regulator of swarming behavior. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6126–6139. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6126-6139.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson N R, Goldman B S. Rapid mapping in Salmonella typhimurium with Mud-P22 prophages. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1673–1681. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1673-1681.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benson N R, Roth J. Suppressors of recB mutations in Salmonella typhimurium. Genetics. 1994;138:11–28. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bibikov S I, Biran R, Rudd K E, Parkinson J S. A signal transducer for aerotaxis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4075–4079. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.4075-4079.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birkmann A, Sawers R G, Böck A. Involvement of the ntrA gene product in the anaerobic metabolism of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;210:535–542. doi: 10.1007/BF00327209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blakely G, Colloms S, May G, Burke M, Sherratt D. Escherichia coli XerC recombinase is required for chromosomal segregation at cell division. New Biol. 1991;3:789–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blattner F R, Plunkett G R, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blomfield I C, McClain M S, Eisenstein B I. Type 1 fimbriae mutants of Escherichia coli K12: characterization of recognized afimbriate strains and construction of new fim deletion mutants. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1439–1445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowden M G, Kaplan H B. The Myxococcus xanthus lipopolysaccharide O-antigen is required for social motility and multicellular development. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:275–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burkart M, Toguchi A, Harshey R M. The chemotaxis system, but not chemotaxis, is essential for swarming motility in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2568–2573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cadieux J E, Kuzio J, Milazzo F H, Kropinski A M. Spontaneous release of lipopolysaccharide by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:817–825. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.817-825.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calvo J M, Matthews R G. The leucine-responsive regulatory protein, a global regulator of metabolism in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:466–490. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.466-490.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiariotti L, Alifano P, Carlomagno M S, Bruni C B. Nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli hisD gene and of the Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium hisIE region. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;203:382–388. doi: 10.1007/BF00422061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chopra A K, Peterson J W, Prasad R. Nucleotide sequence analysis of purH and purD genes from Salmonella typhimurium. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1090:351–354. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(91)90202-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eberhardt S, Richter G, Gimbel W, Werner T, Bacher A. Cloning, sequencing, mapping and hyperexpression of the ribC gene coding for riboflavin synthase of Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1996;242:712–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0712r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eberl L, Molin S, Givskov M. Surface motility of Serratia liquefaciens MG1. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1703–1712. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1703-1712.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eberl L, Winson M K, Sternberg C, Stewart G S, Christiansen G, Chhabra S R, Bycroft B, Williams P, Molin S, Givskov M. Involvement of N-acyl-l-hormoserine lactone autoinducers in controlling the multicellular behaviour of Serratia liquefaciens. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:127–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eriksson U, Lindberg A A. Adsorption of phage P22 to Salmonella typhimurium. J Gen Virol. 1977;34:207–221. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-34-2-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernández-Mora M, Oropeza R, Puente J L, Calva E. Isolation and characterization of ompS1, a novel Salmonella typhi outer membrane protein-encoding gene. Gene. 1995;158:67–72. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finlay B B, Falkow S. Virulence factors associated with Salmonella species. Microbiol Sci. 1988;5:324–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flores A, Casadesús J. Suppression of the pleiotropic effects of HisH and HisF overproduction identifies four novel loci on the Salmonella typhimurium chromosome: osmH, sfiW, sfiX, and sfiY. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4841–4850. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4841-4850.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forst S A, Roberts D L. Signal transduction by the EnvZ-OmpR phosphotransfer system in bacteria. Res Microbiol. 1994;145:363–373. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(94)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fraser G M, Hughes C. Swarming motility. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:630–635. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gary J D, Clarke S. Purification and characterization of an isoaspartyl dipeptidase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4076–4087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gillen K L, Hughes K T. Molecular characterization of flgM, a gene encoding a negative regulator of flagellin synthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6453–6459. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.20.6453-6459.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldberg J B, Coyne M J J, Neely A N, Holder I A. Avirulence of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa algC mutant in a burned-mouse model of infection. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4166–4169. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4166-4169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gottesman S. Proteases and their targets in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:465–506. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenberg E P, Hastings J W, Ulitzer S. Induction of luciferase synthesis in Beneckea harveyi by other marine bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1979;120:87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gygi D, Fraser G, Dufour A, Hughes C. A motile but non-swarming mutant of Proteus mirabilis lacks FlgN, a facilitator of flagella filament assembly. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:597–604. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5021862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gygi D, Rahman M M, Lai H C, Carlson R, Guard-Petter J, Hughes C. A cell-surface polysaccharide that facilitates rapid population migration by differentiated swarm cells of Proteus mirabilis. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:1167–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17061167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hantke K. Regulation of ferric iron transport in Escherichia coli K12: isolation of a constitutive mutant. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;182:288–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00269672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harshey R M. Bees aren't the only ones: swarming in gram-negative bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:389–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harshey R M, Matsuyama T. Dimorphic transition in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: surface-induced differentiation into hyperflagellate swarmer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8631–8635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hay N A, Tipper D J, Gygi D, Hughes C. A nonswarming mutant of Proteus mirabilis lacks the Lrp global transcriptional regulator. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4741–4746. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4741-4746.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heffernan E J, Harwood J, Fierer J, Guiney D. The Salmonella typhimurium virulence plasmid complement resistance gene rck is homologous to a family of virulence-related outer membrane protein genes, including pagC and ail. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:84–91. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.84-91.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirschman J, Wong P K, Sei K, Keener J, Kustu S. Products of nitrogen regulatory genes ntrA and ntrC of enteric bacteria activate glnA transcription in vitro: evidence that the ntrA product is a sigma factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:7525–7529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.22.7525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hmiel S P, Snavely M D, Miller C G, Maguire M E. Magnesium transport in Salmonella typhimurium: characterization of magnesium influx and cloning of a transport gene. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1444–1450. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1444-1450.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hong M, Payne S M. Effect of mutations in Shigella flexneri chromosomal and plasmid-encoded lipopolysaccharide genes on invasion and serum resistance. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:779–791. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3731744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnston C, Pegues D A, Hueck C J, Lee A, Miller S I. Transcriptional activation of Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes by a member of the phosphorylated response-regulator superfamily. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:715–727. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.d01-1719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kinsella N, Guerry P, Cooney J, Trust T J. The flgE gene of Campylobacter coli is under the control of the alternative sigma factor sigma54. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4647–4653. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4647-4653.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kleckner N, Bender J, Gottesman S. Uses of transposons with emphasis on Tn10. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:139–180. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04009-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klose K E, Mekalanos J J. Distinct roles of an alternative sigma factor during both free-swimming and colonizing phases of the Vibrio cholerae pathogenic cycle. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:501–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krikos A, Conley M P, Boyd A, Berg H C, Simon M I. Chimeric chemosensory transducers of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1326–1330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.5.1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuspa A, Plamann L, Kaiser D. Identification of heat-stable A-factor from Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3319–3326. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3319-3326.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kutsukake K. Autogenous and global control of the flagellar master operon, flhD, in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;254:440–448. doi: 10.1007/s004380050437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kutsukake K, Ohya Y, Iino T. Transcriptional analysis of the flagellar regulon of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:741–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.741-747.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kutsukake K, Okada T, Yokoseki T, Iino T. Sequence analysis of the flgA gene and its adjacent region in Salmonella typhimurium, and identification of another flagellar gene, flgN. Gene. 1994;143:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90603-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lacroix J M, Tempête M, Menichi B, Bohin J P. Molecular cloning and expression of a locus (mdoA) implicated in the biosynthesis of membrane-derived oligosaccharides in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1173–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R. Identification of a central regulator of stationary-phase gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee C H, Bhagwat A, Heffron F. Identification of a transposon Tn3 sequence required for transposition immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:6765–6769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.6765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lindum P W, Anthoni U, Christophersen C, Eberl L, Molin S, Givskov M. N-Acyl-l-homoserine lactone autoinducers control production of an extracellular lipopeptide biosurfactant required for swarming motility of Serratia liquefaciens MG1. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6384–6388. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6384-6388.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu D, Reeves P R. Escherichia coli K12 regains its O antigen. Microbiology. 1994;140:49–57. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-1-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maddock J R, Shapiro L. Polar location of the chemoreceptor complex in the Escherichia coli cell. Science. 1993;259:1717–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.8456299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manoil C, Beckwith J. TnphoA: a transposon probe for protein export signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8129–8133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Matsuyama T, Bhasin A, Harshey R M. Mutational analysis of flagellum-independent surface spreading of Serratia marcescens 274 on a low-agar medium. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:987–991. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.987-991.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McCarter L, Hilmen M, Silverman M. Flagellar dynamometer controls swarmer cell differentiation of V. parahaemolyticus. Cell. 1988;54:345–351. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McCarter L, Silverman M. Surface-induced swarmer cell differentiation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1057–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meng S Y, Bennett G N. Nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli cad operon: a system for neutralization of low extracellular pH. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2659–2669. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2659-2669.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Michel G, Ball G, Goldberg J B, Lazdunski A. Alteration of the lipopolysaccharide structure affects the functioning of the Xcp secretory system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:696–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.696-703.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miller C G, Green L. Degradation of proline peptides in peptidase-deficient strains of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:350–356. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.350-356.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mobley H L, Belas R. Swarming and pathogenicity of Proteus mirabilis in the urinary tract. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:280–284. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88945-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nagasawa S, Ishige K, Mizuno T. Novel members of the two-component signal transduction genes in Escherichia coli. J Biochem. 1993;114:350–357. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O'Rear J, Alberti L, Harshey R M. Mutations that impair swarming motility in Serratia marcescens 274 include but are not limited to those affecting chemotaxis or flagellar function. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6125–6137. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6125-6137.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ottemann K M, Miller J F. Roles for motility in bacterial-host interactions. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1109–1117. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4281787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parker C T, Kloser A W, Schnaitman C A, Stein M A, Gottesman S, Gibson B W. Role of the rfaG and rfaP genes in determining the lipopolysaccharide core structure and cell surface properties of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2525–2538. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2525-2538.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Postle K. TonB protein and energy transduction between membranes. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1993;25:591–601. doi: 10.1007/BF00770246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Raetz C R H. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides: a remarkable family of bioactive macroamphiphiles. In: Neidhardt F C, et al., editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1035–1063. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Raha M, Sockett H, Macnab R M. Characterization of the fliL gene in the flagellar regulon of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2308–2311. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2308-2311.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rauprich O, Matsushita M, Weijer C J, Siegert F, Esipov S E, Shapiro J A. Periodic phenomena in Proteus mirabilis swarm colony development. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6525–6538. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6525-6538.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rebbapragada A, Johnson M S, Harding G P, Zuccarelli A J, Fletcher H M, Zhulin I B, Taylor B L. The Aer protein and the serine chemoreceptor Tsr independently sense intracellular energy levels and transduce oxygen, redox, and energy signals for Escherichia coli behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10541–10546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Roberson E B, Firestone M K. Relationship between desiccation and exopolysaccharide production in a soil Pseudomonas sp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1284–1291. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.4.1284-1291.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sanderson K E, Roth J R. Linkage map of Salmonella typhimurium, edition VII. Microbiol Rev. 1988;52:485–532. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.4.485-532.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schmieger H. Phage P22-mutants with increased or decreased transduction abilities. Mol Gen Genet. 1972;119:75–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00270447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shapiro J A. The significances of bacterial colony patterns. Bioessays. 1995;17:597–607. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shaw D J, Guest J R. Molecular cloning of the fnr gene of Escherichia coli K12. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;181:95–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00339011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shin S, Park C. Modulation of flagellar expression in Escherichia coli by acetyl phosphate and the osmoregulator OmpR. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4696–4702. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4696-4702.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Siano M. Master of Arts thesis. Austin: University of Texas; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sitnikov D M, Schineller J B, Baldwin T O. Control of cell division in Escherichia coli: regulation of transcription of ftsQA involves both rpoS and SdiA-mediated autoinduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:336–341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Skorupski K, Taylor R K. Positive selection vectors for allelic exchange. Gene. 1996;169:47–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00793-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stevenson G, Andrianopoulos K, Hobbs M, Reeves P R. Organization of the Escherichia coli K-12 gene cluster responsible for production of the extracellular polysaccharide colanic acid. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4885–4893. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4885-4893.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]