Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

We estimate the longitudinal spending attributable to Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) to the United States government for five years post-diagnosis.

METHODS:

Using data from the Health and Retirement Study matched to Medicare and Medicaid claims, we identify a retrospective cohort of adults with a claims-based ADRD diagnosis along with matched controls.

RESULTS:

The costs attributable to ADRD are $15,632 to traditional Medicare and $8,833 to Medicaid per dementia case over the first five years after diagnosis. Seventy percent of Medicare costs occur in the first two years; Medicaid costs are concentrated among the longer-lived beneficiaries who are more likely to need long-term care and become Medicaid-eligible.

DISCUSSION:

Because the distribution of the incremental costs varies over time and between insurance programs, when interventions occur and the effect on the disease course will have implications for how much and which program reaps the benefits.

Keywords: Medicaid, Medicare, spending, longitudinal costs

1. Background

Over 5.7 million adults are currently living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) in the United States (US) today1-4. Current estimates suggest that ADRD is costing Medicare (Parts A and B) between $3,019 and $10,598 per person per year, in 2017 dollars5-9. However, these cost estimates are incomplete. The prescription drug program within Medicare, Part D, was enacted in 2006 and thus these expenditures are missing from the older literature. Medicaid, the public insurance program for the low-income population and the primary payer for long-term care in the U.S.10, is often ignored. Since ADRD is characterized by cognitive impairment leading to difficulties with daily activities11, long-term care expenditures are likely considerable. Medicaid’s role in covering those expenditures is also considerable, since over one-quarter of people with ADRD are dual-eligible (covered by both Medicare and Medicaid), compared to 11 percent for the general population12. The literature estimating the impact of ADRD on Medicaid is sparse due to data limitations7. Four papers estimate the costs to Medicaid nationally, relying on self-reported utilization and imputed Medicaid expenditures7,13-15. Two papers use Medicaid claims, but only for one state16 or one urban area17. In order to prepare for the future, policy makers need to be armed with reliable estimates of the incremental costs of ADRD to both public health insurance programs, Medicare and Medicaid.

In addition to the incompleteness of the costs estimated, the literature has predominantly focused on estimating costs based on prevalent cases. Prevalent cost estimates are useful for knowing current spending but have limited use for predicting future costs if either the case mix is changing or if the costs of the disease vary over the course of the disease. Recent work suggests both are happening. The incidence rate of ADRD is declining in high-income countries2,18, leading to a changing case mix, and evidence suggests that costs associated with dementia vary greatly based on time since diagnosis or time prior to death15,19-24.

This paper builds on work by White et al.21 to estimate the incremental costs of ADRD to the public purse through the Medicare (Parts A, B, and D) and Medicaid programs for the first five years after diagnosis. We estimate total spending and spending by cost component (inpatient, prescription drugs, nursing homes and home health care, and other spending) to understand what utilization is driving costs. These elements are crucial to understanding the current and future cost burden of ADRD.

2. Methods

2.1. Data

We use data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) 1992-2015, a publicly available, nationally representative bi-annual survey that gathers information on the health, health services utilization, and financial resources of older Americans (age 50+). We use the subset of survey respondents who consented to link survey responses to Medicare Parts A (inpatient), B (outpatient), and D (prescription drug) claims from 1992-2015 (over 80% of Medicare-eligible participants). These data include carrier, durable medical equipment, home health, hospice, inpatient, outpatient, and skilled nursing facilities. Minimal bias is introduced by this sample restriction25,26.

In addition, we use linked Medicaid claims (MAX files) from 1999-2012 for those who were enrolled in Medicaid fee-for-service at any point during the study period. We do not use the limited information in the MAX files on Managed care enrollees.27 We do include individuals with both full- and partial-benefits within the Medicaid program since they represent costs to the system.

2.2. Sample

We defined the dementia cohort using ICD-9 diagnostic codes from Medicare claims. To qualify as a dementia case, individuals were required to be enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B coverage for at least 12 months before and one month after receipt of one of the following diagnosis codes in an inpatient, skilled nursing facility (SNF), home health, hospital outpatient or carrier claim: 331.x, 290.x, 294.x, or 797.19,28 (Specific codes provided in Appendix Table A1.) We defined the diagnosis date for dementia cases as the date of the first qualifying diagnosis code, which is likely after the true onset date. We eliminate individuals in Medicare Advantage plans around the time of diagnosis due to incomplete utilization information available in claims data.

To isolate the incremental costs due to ADRD, we selected a comparison group of HRS participants matching on sex, race/ethnicity, birth year, HRS-survey entry year, and state of residence. After matching the dementia cases, up to five controls were randomly selected for each case. The comparison group faced similar inclusion criterion; they had to be enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B for the 12 months before and one month after the diagnosis date of their matched case. Additionally, controls had no dementia diagnosis themselves or for a household member (as identified through the household member’s claims data) prior to diagnosis or for the 72 months following the diagnosis date of their matched dementia case. This last criterion addresses the concern that the health and health care costs of these participants may have been influenced by their household member’s dementia.29,30 Individuals who eventually received a dementia diagnosis were eligible to be controls at younger ages (at least 6 years prior to diagnosis). This was allowed to ensure comparable longevity spells between our cases and controls. Controls were given the diagnosis date of their assigned case to allow for a comparison of equivalent time periods.

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington, the University of Pennsylvania, the HRS Restricted Data Applications Processing Center, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Privacy Board.

2.3. Outcomes

We measured expenditures covered under Medicare and Medicaid. We separately estimate total Medicare spending, total Medicaid spending, and spending by service component within each program: inpatient, prescription drugs, nursing home and home health, and all other spending (for example, durable medical equipment), the largest component of which is physician services. We categorize expenditures based on the delivery location, but recognize the types of services covered in home health and nursing facilities differ– post-acute care in Medicare, and would include long-term care for Medicaid.

Monthly expenditures for the 12 months prior to and 60 months following the diagnosis date were calculated. We adjusted expenditures for inflation using the Personal Consumption Expenditures price index for health care and report all amounts in 2017 dollars.

2.4. Statistical analysis

To calculate the marginal effect of dementia on public expenditures, we used the estimator described by Basu and Manning (2010) for estimating costs under censoring.31 Censoring appears in our data for two reasons: individuals can switch out of traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage, or their 60 month follow-up period can extend beyond 12/31/2015, the endpoint of our claims data. Estimation was done in several steps. First, costs were estimated using a two-part model due to the skewness in medical cost data; the first part of the model estimated the probability of any costs during each month using a logit model, while the second part estimated the magnitude of costs when costs were greater than zero using a generalized linear model with gamma family and log link. This two-step procedure is estimated on two separate samples when estimating Medicare expenditures, both total and by service component, and when estimating total Medicaid expenditures: (1) for all observed months prior to death or censoring, and (2) for the month in which death occurred. We estimate separately for the month of death due to the high concentration of costs around the time of death. Due to small sample sizes when estimating Medicaid expenditures by service component, only one sample is used, combining all observed months including the month in which death occurred. Finally, an accelerated failure time model based on the lognormal distribution for time was used to estimate each subject’s survival function after accounting for censoring.

All models controlled for age, sex, race, marital status, education (< college, college+), quartile of total Medicare expenditures for the 12 months prior to the diagnosis date, and indicator variables for the following comorbid conditions: anemia, arthritis, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, diabetes, heart disease (atrial fibrillation, ischemic heart disease, or heart failure), hypertension, and stroke. Additionally, models included time from diagnosis (in months), an interaction term for dementia status and time from diagnosis, indicators for years since diagnosis, and interactions between time since diagnosis and the year indicator variables. These terms allow for non-linearity in the relationship between time and costs, and for this relationship to differ based on the year from diagnosis.

The marginal effects from each of the models were estimated using recycled predictions for the dementia cases. Standard errors were obtained via bootstrapping with 1,000 iterations. All analyses were conducted in Stata 17 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

3. Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the sample, comparing dementia cases (n=3,658) to the first matched control. We match on sex, race/ethnicity and birth year, so we see no statistical differences in those characteristics by design. There are no statistical differences in marital status. However, there are differences in levels of education, with the dementia cohort being slightly less educated than their first control. Further, the dementia cohort is significantly sicker across the board, with every comorbidity, except cancer, more prevalent at baseline. This difference in baseline health helps to explain the difference in baseline Medicare expenditures between the two cohorts; Medicare spending on the dementia cohort is almost twice as high as spending on the controls before the dementia diagnosis. We adjust for these covariates in all regression models.

Table 1.

Characteristics of dementia cases and the first matched control

| Participants with dementia diagnosis (N=3,653) |

First

matched control (N=3,653) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age at diagnosis in years, mean (sd) | 79.9 (7.4) | 79.7 (7.4) | 0.230 |

| Male, % | 36.8 | 36.8 | 1.000 |

| Race, % | 0.178 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 79.3 | 79.3 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 13.2 | 12.7 | |

| Hispanic | 6.3 | 6.2 | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 1.2 | 1.8 | |

| Marital status at diagnosis, % | 0.686 | ||

| Married | 38.2 | 38.9 | |

| Separated/divorced | 6.7 | 7.4 | |

| Widowed | 40.7 | 39.5 | |

| Never married | 2.9 | 2.7 | |

| Unknown marital status | 11.5 | 11.5 | |

| Educational attainment, % | <0.001 | ||

| Less than high school | 37.9 | 33.1 | |

| High school graduate | 33.9 | 34.3 | |

| Some college | 15.8 | 17.5 | |

| College and above | 12.4 | 15.1 | |

| Veteran, % | 20.9 | 22.9 | 0.041 |

| Health characteristics at baseline * | |||

| Comorbid conditions, % | |||

| Anemia | 40.0 | 21.7 | 0.000 |

| Arthritis | 37.3 | 28.1 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 13.5 | 8.3 | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 10.2 | 9.6 | 0.388 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 17.4 | 9.1 | <0.001 |

| COPD | 19.2 | 11.7 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 23.5 | 5.7 | 0.000 |

| Diabetes | 30.6 | 23.3 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 32.7 | 20.2 | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 34.8 | 32.1 | 0.014 |

| Hypertension | 69.2 | 55.1 | <0.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 47.7 | 34.9 | <0.001 |

| Stroke/TIA | 15.0 | 3.3 | 0.000 |

| Total Medicare reimbursement, mean (sd) | 18,328 (30,397) | 9,517 (18,882) | 0.000 |

| Insurance coverage at diagnosis | |||

| Medicare Part D, % | 53.6 | 48.5 | 0.006 |

| Medicaid, % | 10.1 | 8.4 | 0.048 |

| Insurance coverage at death ** | |||

| Medicare Part D, % | 55.2 | 52.3 | 0.127 |

| Medicaid, % | 13.9 | 12.1 | 0.098 |

The baseline period was defined as the 12 months prior to the diagnosis date.

Among the sub-sample where death is observed in the data. N=2,947 and 2,385 in dementia and first matched control cohorts, respectively.

Insurance coverage varies between the cases and the first-matched control, with higher Medicaid and Part D coverage among cases at baseline. However, the Part D coverage difference disappears by the time of death among the deceased. Medicaid coverage is higher at baseline among the dementia cohort. However, there are minimal differences in Medicaid coverage between the dementia cohort and controls at death.

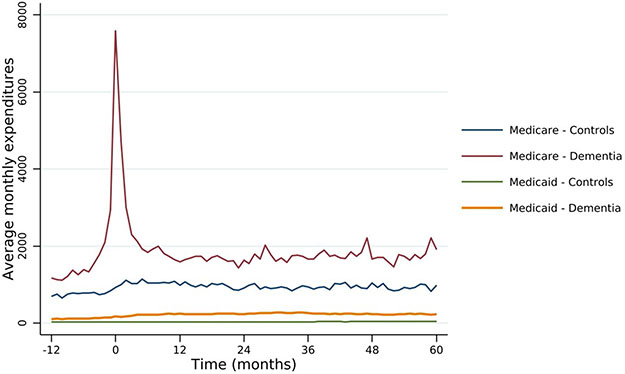

Figure 1 presents the unadjusted average monthly expenditures to the Traditional Medicare and Medicaid programs among those who have not died or been censored for both the dementia and control cohorts. Prior to diagnosis, the dementia cohort has a higher level of spending for both the Medicare and Medicaid programs, but the trends start roughly parallel prior to diagnosis. A few months before diagnosis, there are significant and substantial increases in spending for Medicare – which is consistent with 40 percent of the cohort first having diagnosis codes appear during an inpatient event (hospital or SNF setting). Medicare expenditures decline almost as quickly as they rose, and again appear to be stable, although at a higher level, one year after diagnosis. Medicaid expenditures increase at the time of diagnosis, although much less than Medicare expenditures, and maintain at this level after diagnosis, while the control cohort’s Medicaid expenditures remain close to zero throughout.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted mean FFS Medicare and Medicaid expenditures for participants with and without dementia diagnosis

Table 2 presents the regression-adjusted absolute and incremental costs of ADRD to the Traditional Medicare and Medicaid programs in the first 5 years from diagnosis. Medicare expenditures on the dementia cohort were $72,722 (95% CI: $70,701; $75,399) in the first 5 years after diagnosis. Unlike Figure 1 where we compared to controls, Table 2 presents the predicted costs from our model for the cases under the counterfactual scenario that these same individuals did not have dementia. Under the counterfactual scenario, their 5-year expenditures would be $57,091 (95% CI: $54,895; $59,214), for an incremental cost attributable to dementia of $15,632 (95% CI: $12,780; $18,588) over five years. As highlighted in Figure 1, these costs are concentrated around diagnosis, with more than 87 percent of these costs incurred within the first two years of diagnosis. When we eliminate the costs associated with the hospitalization or nursing facility stay within which the diagnosis first occurs, the first year’s incremental costs decrease to $7,314, and 82 percent of costs occur within the first two years (See Appendix Table A2).

Table 2.

Period-specific absolute and incremental costs to FFS Medicare and Medicaid

| Total costs | Incremental costs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with dementia diagnosis |

Predicted costs without dementia |

Incremental costs if survival held constant |

Incremental costs due to changed survival |

Total incremental costs |

|

| FFS Medicare | |||||

| Months 1-12* | $24,501 (23,494; 25,477) | $15,213 (14,512; 15,928) | $10,093 (9,039; 11,183) | -$805 (−960; −665) | $9,288 (8,241; 10,357) |

| Months 13-24 | $15,709 (15,009; 16,449) | $11,481 (10,920; 12,063) | $5,646 (5,072; 6,264) | -$1,418 (−1,679; −1,173) | $4,229 (3,617; 4,850) |

| Months 25-36 | $12,723 (12,056; 13,382) | $10,642 (10,120; 11,201) | $3,796 (3,282; 4,337) | -$1,715 (−2,004; −1,416) | $2,081 (1,510; 2,653) |

| Months 37-48 | $10,986 (10,287; 11,663) | $10,401 (9,811; 11,028) | $2,534 (1,959; 3,147) | -$1,949 (−2,310; −1,614) | $585 (−103; 1,294) |

| Months 49-60 | $8,802 (8,160; 9,493) | $9,353 (8,792; 9,977) | $1,386 (716; 2,057) | -$1,937 (−2,294; −1,592) | -$551 (−1,337; 270) |

| Total | $72,722 (70,185; 75,399) | $57,091 (54,895; 59,214) | $23,456 (20,861; 26,188) | -$7,825 (−9,198; −6,476) | $15,632 (12,780; 18,588) |

| Medicaid | |||||

| Months 1-12* | $2,442 (2,113; 2,837) | $657 (521; 802) | $1,826 (1,468; 2,214) | -$41 (−56; −30) | $1,785 (1,429; 2,168) |

| Months 13-24 | $2,324 (2,006; 2,683) | $659 (526; 798) | $1,752 (1,442; 2,068) | -$87 (−114; −64) | $1,665 (1,347; 1,989) |

| Months 25-36 | $2,404 (2,066; 2,770) | $700 (564; 854) | $1,823 (1,502; 2,170) | -$119 (−156; −88) | $1,704 (1,378; 2,047) |

| Months 37-48 | $2,491 (2,112; 2,899) | $735 (588; 907) | $1,901 (1,542; 2,296) | -$145 (−191; −106) | $1,756 (1,390; 2,157) |

| Months 49-60 | $2,734 (2,285; 3,240) | $811 (631; 1,006) | $2,100 (1,637; 2,609) | -$177 (−232; −129) | $1,924 (1,444; 2,442) |

| Total | $12,395 (10,847; 13,981) | $3,562 (2,928; 4,292) | $9,402 (7,861; 10,981) | -$570 (−746; −421) | $8,833 (7,267; 10,509) |

Notes:

Month 1 is the month in which the diagnosis date occurred

Further, we estimate the impact of increased utilization compared to changes in survival. We find that increased utilization accounts for most of the increased spending, and differential survival lowers the incremental costs of ADRD by one-third. If the dementia cohort had the same survival as the control cohort, incremental costs would be $23,456 (95% CI: $20,861-$26,188), or $7,825 (95% CI: -$9,198; -$6,476) higher over five years.

Medicaid FFS expenditures on the dementia cohort overall are much lower than the Medicare expenditures within the first five years from diagnosis, totaling $12,395 (95% CI: $10,847; $13,981). However, the estimate of the spending on this cohort if they did not have dementia is low, leading to an incremental cost due to ADRD estimate of $8,833 (95% CI: $7,267; $10,509). Unlike for Medicare expenditures, differential survival plays little role in the incremental Medicaid costs. It is also worth noting that, unlike the unadjusted time trends shown in Figure 1, the adjusted Medicaid expenditures are fairly stable over time, ranging from $2,324 to $2,734 for the dementia cohort. This is due to the fact that Medicaid coverage and expenditures are more prevalent near the end of the five-year window, when more than 67 percent of the sample has already died.

It is important to note that these incremental costs are per person costs for the cohort as a whole, regardless of whether an individual is alive or, in the case of Medicaid expenditures, enrolled in Medicaid. Table 3 presents the average incremental Medicare and Medicaid expenditures for the cohort as a whole and conditional on survival and dual-eligibility status. For Medicare, the average incremental expenditures decrease when examining expenditures on survivors vs. the entire cohort, and the general pattern remains stable. Medicare expenditures are highest in the first few years, and slowly decreases after diagnosis. For Medicaid, however, because living a long time with dementia is positively correlated with enrolling in Medicaid, the time pattern of average incremental expenditures changes. Instead of the stable pattern of Medicaid spending in the overall cohort, among survivors, average expenditures increase with time since diagnosis. Medicaid spending in year five on individuals alive five years after diagnosis is 2.6 times higher than spending in year one on individuals alive one year after diagnosis. However, this still does not reflect the large role Medicaid plays among the enrolled individuals. The level of spending is 1.7 times higher over 5 years ($36,006 vs. $61,482), when conditioning on those who are both alive and enrolled.

Table 3.

Cohort and Conditional Incremental costs of ADRD

| Medicare FFS | Medicaid FFS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort as a whole | Conditional on being alive |

Cohort as a whole | Conditional on being alive |

Conditional on being alive and enrolled |

|

| Months 1-12* | $9,288 (8,241; 10,357) | $12,133 (10,827; 13,437) | $1,785 (1,429; 2,168) | $2,282 (1,846; 2,773) | $36,006 (29,934; 42,832) |

| Months 13-24 | $4,229 (3,617; 4,850) | $8,930 (7,988; 9,933) | $1,665 (1,347; 1,989) | $2,905 (2,394; 3,440) | $35,113 (29,878; 41,297) |

| Months 25-36 | $2,081 (1,510; 2,653) | $7,345 (6,352; 8,436) | $1,704 (1,378; 2,047) | $3,739 (3,113; 4,470) | $42,935 (36,240; 50,479) |

| Months 37-48 | $585 (−103; 1,294) | $5,806 (4,450; 7,204) | $1,756 (1,390; 2,157) | $4,629 (3,777; 5,554) | $47,279 (39,114; 56,672) |

| Months 49-60 | -$551 (−1,337; 270) | $3,693 (1,960; 5,499) | $1,924 (1,444; 2,442) | $5,924 (4,592; 7,330) | $61,482 (49,268; 76,611) |

Notes:

Month 1 is the month in which the diagnosis date occurred

Table 4 breaks down the public expenditures by payer into their cost components. Medicare expenditures on ADRD are driven by inpatient, SNF and home health care, which represent 95 percent of the incremental costs over the first five years after diagnosis. All are front-loaded; indeed, beneficiaries with ADRD are predicted to spend less on inpatient care five years after diagnosis. The level of the incremental costs due to prescription drugs (Part D) increases over time but remains relatively low, at $68-$269 annually. Medicaid expenditures on ADRD are also driven by long-term care (nursing homes and home health), accounting for 95 percent of Medicaid expenditures in the first five years. Prescription drug spending levels are also low within Medicaid, ranging from $38-$101 annually. All categories of spending except long-term care show a front-loaded pattern of expenditures.

Table 4.

Period-specific incremental costs by payer and service type for the cohort as a whole

| Medicare | Medicaid | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient | Prescription drugs | Skilled

Nursing Facility and Home Health |

Inpatient | Prescription drugs | Skilled

Nursing Facility and Home Health |

|

| Months 1-12* | $4,806 (4,158; 5,477) | $68 (−24; 161) | $4,546 (4,142; 4,926) | $17 (7; 27) | $101 (59; 145) | $1,415 (1,147; 1,716) |

| Months 13-24 | $1,576 (1,262; 1,882) | $97 (11; 174) | $1,978 (1,757; 2,200) | $10 (3; 16) | $81 (47; 117) | $1,369 (1,101; 1,664) |

| Months 25-36 | $459 (175; 765) | $139 (52; 226) | $1,298 (1,092; 1,517) | $7 (1; 13) | $65 (31; 99) | $1,415 (1,124; 1,730) |

| Months 37-48 | -$335 (−671; 4) | $193 (88; 307) | $748 (489; 1,011) | $4 (−3; 11) | $51 (14; 85) | $1,500 (1,197; 1,850) |

| Months 49-60 | -$826 (−1,182; −477) | $269 (126; 422) | $239 (−37; 520) | $2 (−7; 11) | $38 (−1; 78) | $1,597 (1,226; 1,989) |

| Total | $5,680 (4,178; 7,222) | $767 (301; 1,232) | $8,809 (7,667; 9,872) | $39 (9; 68) | $336 (171; 498) | $7,296 (6,039; 8,641) |

Notes:

Month 1 is the month in which the diagnosis date occurred

4. Discussion

ADRD represents a considerable cost to the public purse. Over the first five years after diagnosis, we estimate that ADRD costs $24,465 per person, with a 64-36 split between Medicare ($15,632) and Medicaid ($8,833). There are also different trajectories to this expenditure by insurance program and by expenditure type – Medicare costs are concentrated soon after diagnosis while Medicaid expenditures are relatively evenly distributed over the first five years. Inpatient expenditures within Medicare decrease starting five years after ADRD diagnosis. This is consistent with the literature that has found higher health care utilization around the time of diagnoses.19,32,33 This could be due to decreased utilization since patients are increasing their SNF use, or due to less intense inpatient use, for example by foregoing elective procedures since their health trajectory is already being driven by their ADRD. The estimated Medicaid costs in year 5 among those who are dual-eligible are roughly equivalent to the annual Medicaid expenditure of a nursing home (Medicaid covers approximately 70% of a private pay, which was $235/day for a semi-private room in 2017,34 or $60,042.50).

These longitudinal patterns are important for understanding the future cost burden of the disease. Most current estimates of the cost of ADRD are based on prevalent cases, which can be used to forecast future costs as long as one assumes that costs are not dependent on the time since diagnosis. Our estimates suggest that this approach might give reasonable estimates for forecasting aggregate Medicaid expenditures since they are relatively constant over the first five years after diagnosis. However, the pronounced time-trend in Medicare expenditures makes prevalent case estimates particularly difficult to use in predicting future costs; the time since diagnosis matters for aggregate Medicare costs.

This study has limitations. We rely on diagnosis of dementia in claims data, which is likely not sensitive to the true onset of disease symptoms. Indeed, over 40 percent of our sample is first diagnosed in an inpatient setting. However, there is mixed evidence on the direction of the bias in estimating costs that introduced by this mismeasurement. We do not estimate the incremental costs to the Medicare Advantage program or Medicaid managed care, both of which have increasing coverage rates over the last 20 years and may have very different spending patterns. These estimates are only the direct medical costs to the public purse (Medicaid and Medicare) and are far from a full accounting of the cost of illness, which would include out-of-pocket expenditures and the cost of caregiving by family/friend care partners. We are limited to estimating the incremental costs due to ADRD for the first five years after diagnosis due to data and sample size limitations, while survival after diagnosis can be over 20 years.35 We do not limit the sample based on age, only by Medicare enrollment. Only two percent of our sample is under age 65 and omitting these observations do not change our results.

In conclusion, the incremental costs of ADRD to the US government are substantial. On average, each case of ADRD is costing the government $24,465 over the first five years after diagnosis. Most of the literature has focused on estimating the costs to Medicare, missing over a third of the incremental costs over the first five years after diagnosis. Our estimates show that the cost estimates vary dramatically over the first five years for the Medicare program, and mortality associated with the disease decreases these costs. While aggregate Medicaid costs are relatively constant for the first five years, this is driven largely by enrollment in the Medicaid program.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Systematic review:

The authors reviewed the literature on the costs of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) using traditional sources. While the costs to the Medicare program are well studied, the costs to the Medicaid program are not. Further, no papers combine both sources of data at a national level. The relevant citations are appropriately cited.

Interpretation:

Our findings contribute to the understanding of the costs to both national health insurance programs, in both the level of spending and in the longitudinal pattern of spending after diagnosis.

Future Directions:

This manuscript estimates the incremental costs of ADRD to both the Medicare and Medicaid programs using nationally representative data. Future work could use national linked data to confirm the results and test the robustness of the results to different definitions of ADRD-onset. Future directions could examine how Medicaid program features influence both the level and pattern of Medicaid spending.

Highlights.

Estimated longitudinal costs over the first five years after diagnosis.

Costs due to ADRD are $15,632 to traditional Medicare per dementia case for 5 years.

Costs due to ADRD are $8,833 to traditional Medicaid per dementia case for 5 years.

Which program benefits from interventions depends on the impact on the disease.

Acknowledgements/Conflicts/Funding Sources

This work was funded by the National Institutes on Aging (R01AG049815 - all authors). All authors have received funding through their institutions from the NIH in the last three years. In addition, Dr. Coe has received funding from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in the last three years, both directly and through her institution. Dr. Larson has received UpToDate royalties over the last three years. Dr. Basu has received consulting fees. Dr. Coe is part of the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) Data Safety Monitoring Board and the Advisory Board for the Hopkins Economics of Alzheimer’s Disease & Services (HEADS) Center.

Contributor Information

Norma B. Coe, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, 19104 USA.

Lindsay White, RTI International, Seattle, WA 98104 USA.

Melissa Oney, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104 USA.

Anirban Basu, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195 USA.

Eric B. Larson, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, WA 98101 USA.

References

- 1.Alzheimer's Association. 2018 Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langa K, Larson E, Crimmins E, et al. A Comparison of the Prevelence of Dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthews FE, McKeith I, Bond J, Brayne C, Mrc C. Reaching the population with dementia drugs: what are the challenges? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(7):627–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daras LC, Feng Z, Wiener JM, Kaganova Y. Medicare Expenditures Associated With Hospital and Emergency Department Use Among Beneficiaries With Dementia. Inquiry: The journal of health care organization, provision, and financing. 2017;54(Jan). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiner M, Powe NR, Weller WE, Shaffer TJ, Anderson GF. Alzheimer's disease under managed care: implications from Medicare utilization and expenditure patterns. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(6):762–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor DH Jr., , Sloan FA. How much do persons with Alzheimer's disease cost Medicare? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(6):639–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(14):1326–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bynum JP RP, Weller W, Niefeld M, Anderson GF, Wu AW. The relationship between a dementia diagnosis, chronic illness, medicare expenditures, and hospital use. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(2):187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deb A, Sambamoorthi U, Thornton J, Schreurs B, & Innes K Direct medical expenditures associated with Alzheimer’s and related dementias (ADRD) in a nationally representative sample of older adults – an excess cost approach. . Aging & Mental Health. 2018;22(5):619–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reaves EL, Musumeci M. Medicaid and Long-Term Services and Supports: A Primer. December 15 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alzheimer's Association. What is dementia? Alzheimer's Association. http://www.alz.org/what-is-dementia.asp. Accessed 11/05/2016, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alzheimer's Association. 2017. Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures. Chicago, IL: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayyagari P, Salm M, Sloan FA. Effects of diagnosed dementia on Medicare and Medicaid program costs. Inquiry. 2007;44(4):481–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Z, Zhang K, Lin PJ, Clevenger C, Atherly A. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Lifetime Cost of Dementia. Health Services Research. 2012;47(4):1660–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The Burden of Health Care Costs for Patients With Dementia in the Last 5 Years of Life. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2015;163(10):729–U175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bharmal MF, Dedhiya S, Craig BA, et al. Incremental dementia-related expenditures in a medicaid population. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;20(1):73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arling G, Tu W, Stump TE, Rosenman MB, Counsell SR, Callahan CM. Impact of dementia on payments for long-term and acute care in an elderly cohort. Medical care. 2013;51(7):575–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattthews K, Xu W, Gaglioti A, et al. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias in the United States (2015–2060) in adults aged ≥65 years. Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2018;in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin PJ, Zhong Y, Fillit HM, Chen E, Neumann PJ. Medicare Expenditures of Individuals with Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias or Mild Cognitive Impairment Before and After Diagnosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(8):1549–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamb VL, Sloan FA, Nathan AS. Dementia and Medicare at life's end. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(2):714–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White L, Fishman P, Basu A, Crane PK, Larson EB, Coe NB. Medicare expenditures attributable to dementia. Health Services Research. 2019:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson R, Rentz D, Andrews J, Zagar A, Kim Y, Bruemmer V, Schwartz R, Ye W, &Fillit H . Costs of Early Stage Alzheimer’s Disease in the United States: Cross-Sectional Analysis of a Prospective Cohort Study (GERAS-US)1. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2020;75(2):437–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pyenson B, Sawhney T, Steffens C, Rotter D, Peschin S, Scott J, & Jenkins E . The Real-World Medicare Costs of Alzheimer Disease: Considerations for Policy and Care. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy. 2019;25(7):800–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crouch E PJ, Bennett K, Eberth JM. . Differences in Medicare Utilization and Expenditures in the Last Six Months of Life among Patients with and without Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders. . Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2019;22(2):126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meijer E, Karoly LA, Michaud P-C. Estimates of potential eligibility for low income subsidies under Medicare Part D, . Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation;2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meijer E, Michaud P-C, Karoly L. Using Matched Survey and Administrative Data to Estimate Eligibility for the Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidy Program. Social Security Bulletin. 2010;70(2). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruttner L, Borck R, Nysenbaum J, William S. Guide to MAX Data. Medicaid Policy Brief. Mathematica Policy Research; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic conditions data warehouse condition categories. www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories. Accessed August 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ankuda CK, Maust DT, Kabeto MU, McCammon RJ, Langa KM, Levine DA. Association Between Spousal Caregiver Well-Being and Care Recipient Healthcare Expenditures. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2017;65(10):2220–2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu CW, Scarmeas N, Ornstein K, et al. Healthcare use and cost in dementia caregivers: longitudinal results from the Predictors Caregiver Study. Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2015;11(4):444–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basu A, Manning WG. Estimating lifetime or episode-of-illness costs under censoring. Health Econ. 2010;19(9):1010–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suehs B, Davis C, Alvir J, al e. The clinical and economic burden of newly diagnosed Alzheimer's disease in a medicare advantage population. American journal of Alzheiemer's disease and other dementias. 2013;28(3):384–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phelan E, Borson S, Grothaus L, Balch S, Larson E. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA. 2012;307(2):165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Genworth. Annual Costs of Care Survey: Costs Continue to Rise Across All Care Settings. Sept 26 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alzheimer's Association. Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2021;17(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.