Abstract

Background

Prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity are problematic for individuals with schizophrenia partly because atypical antipsychotics and mental distress themselves increase appetite, thus promoting subsequent body weight gain and deterioration of glycemic control. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists have been gaining attention for their glucose-lowering and body weight-reducing effects in obese individuals with type 2 diabetes generally, but their effects in those also having schizophrenia have not been adequately addressed.

Case presentation

This case was a 50-year-old obese woman having type 2 diabetes and schizophrenia. Although she was receiving oral anti-diabetes treatment, her HbA1c remained inadequately controlled (8.0–9.0%) partly due her difficulty in following instructions on heathy diet and exercise. In addition, she was repeatedly hospitalized due to suicide attempts by overdosing on her anti-psychotic and anti-diabetes drugs. Her HbA1c was elevated to as high as 10.2% despite the use of multiple anti-diabetes drugs including the GLP-1 receptor agonist dulaglutide, and she was hospitalized in our department. We chose the GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide to replace dulaglutide along with a multidisciplinary team approach that included a cognitive–behavioral therapist. The patient perceived that her hunger was suppressed when she started receiving semaglutide 0.5 mg. After discharge, semaglutide was remarkably more effective than dulaglutide in that it reduced and maintained the patient’s HbA1c and body weight for 6 months after initiation of the drug.

Conclusion

The GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide can be effective in maintaining appropriate control of glycemia and body weight in diabetes and obesity with schizophrenia.

Keywords: GLP-1 receptor agonist, Schizophrenia, Obesity, Type 2 diabetes, Bodyweight

Introduction

Prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and obesity are problematic for individuals with schizophrenia. Almost half of patients with schizophrenia have body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 and 2.5 times higher risk of developing T2D compared to healthy individuals [1]. For long-term control of body weight in individuals with obesity generally, the multidisciplinary team approach, which provides self-management education and support for healthy diet, physical exercise, and instruction in coping with stress, is known to be effective. However, following a healthy diet and exercise routine is often difficult or even impossible for individuals with schizophrenia. To make matters worse, while mazindol is the only anti-obesity drug approved for use in Japan, it is contraindicated in individuals with schizophrenia. In addition to obesity, type 2 diabetes is also frequently seen in individuals with schizophrenia; both obesity-related elevation of insulin resistance and antipsychotic drugs are known to disturb glucose tolerance in schizophrenia [1]. Thus, both effective anti-obesity and anti-diabetes therapies need to be established for individuals with schizophrenia.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, a class of anti-diabetes drug, have been gaining attention for their glucose-lowering and body weight-reducing effects together with their cardiovascular and renal protective effects in individuals with T2D and obesity [2]. In fact, the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide reduces body weight and improves glucose tolerance in obese individuals with prediabetes and schizophrenia [3]. On the other hand, it has been demonstrated that exenatide once‐weekly failed to reduce body weight in obese, antipsychotic‐treated patients with schizophrenia [4]. It remains to be investigated whether or not other GLP-1 receptor agonists are effective in treatment of T2D and obesity in individuals with schizophrenia.

Here we report a case of schizophrenia with T2D and obesity that was treated with the GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide, which was found to be remarkably effective in improving and maintaining glycemic control and body weight.

Case presentation

This case was a 50-year-old obese woman having type 2 diabetes and schizophrenia. Her body weight was normal during childhood and was 50 kg at the age of 20. At the age of 31, she began to have hallucinations and exhibit inappropriate laughter and autistic behavior; she was diagnosed with schizophrenia by a psychiatrist in our institution. At the age of 34, her body weight rose to 107 kg, possibly related to overeating due to atypical antipsychotic use. At the age of 40, her psychiatrist-in-charge found elevated fasting glucose levels and referred her to our department. While no one in her family was obese, her father had T2D. Upon analysis in our outpatient ward, she was diagnosed with T2D. Although she started receiving oral anti-diabetes treatment, her HbA1c remained inadequately controlled (8.0–9.0%), partly due her difficulty in following instructions on heathy diet and exercise. In addition, she was repeatedly hospitalized due to suicide attempts by overdosing on her anti-psychotic and anti-diabetes drugs. At the age of 50, her HbA1c was elevated to as high as 10.2% despite the use of multiple anti-diabetes drugs (i.e., q.w. dulaglutide 0.75 mg, q.d. luseogliflozin 2.5 mg, t.i.d. metformin 500 mg, and q.d. pioglitazone 7.5 mg), likely due to eating between meals associated with atypical antipsychotic use (i.e., q.d. risperidone 4 mg), and she was hospitalized in our department.

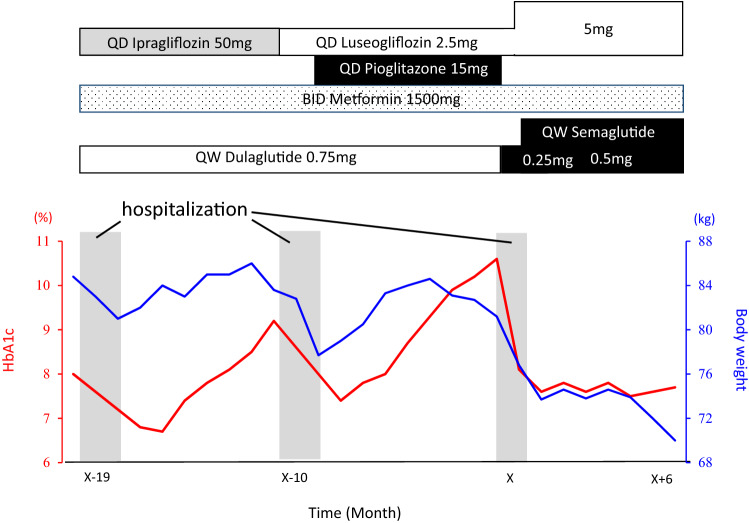

Upon admission to our inpatient ward, her BMI was 34.4 kg/m2 (height 153.6 cm and body weight 81.2 kg), but no abnormal physical findings or endocrinological abnormalities suggesting secondary obesity were noted (Table 1). The case had no micro- or macro-vascular complications. A multidisciplinary team approach, which included diabetes specialists, certified diabetes educators and a clinical psychologist, was taken to provide the case with diabetes self-management education and support. Cognitive–behavioral therapy was delivered by the clinical psychologist. Diet [i.e., 1400 kcal/day (27 kcal/ideal body weight) with carbohydrate 45%, protein 20%, and fat 35%] and aerobic and resistance exercises (approximately 160 kcal/day) was monitored by registered dieticians and physical therapists, respectively. Pioglitazone was then stopped and dulaglutide was replaced by q.w. semaglutide (Fig. 1). The patient perceived that her hunger was suppressed when she started receiving q.w. semaglutide 0.5 mg. Her total score on the eating behavior questionnaire [5] was 124 points upon admission to our inpatient ward, and improved to 80 points at the time of discharge. Six months after discharge, her HbA1c remained well-controlled and her body weight was reduced by > 10 kg without a reduction in skeletal muscle index estimated by bioelectrical impedance analysis [At admission, body weight 81.2 kg, body fat mass 41.4 kg, and skeletal muscle index (SMI) 7.3 kg/m2; at 6 months after discharge, body weight 69.3 kg, body fat mass 23.8 kg, and SMI 8.1 kg/m2] (Fig. 1). The substantial reduction of body fat mass suggested reduced insulin resistance, while fasting insulin levels or visceral fat areas were not measured before or 6 months after initiation of semaglutide.

Table 1.

Laboratory data of the patient

| Urinalysis | Biochemistry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | – | TP (g/dL) | 5.7 (6.6–8.1) | Na+ (mEq/L) | 141 (138–145) |

| Glucose | 4+ | Albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 (4.1–5.1) | K+ (mEq/L) | 3.5 (3.6–4.8) |

| WBC | 2+ | AST (IU/L) | 21 (13–30) | Cl− (mEq/L) | 108 (101–108) |

| RBC | – | ALT (IU/L) | 32 (7–23) | Ca2+ (mg/dL) | 8.7 (8.8–10.1) |

| Ketone | – | LDH (IU/L) | 150 (124–222) | Pi2− (mg/dL) | 3.6 (2.7–4.6) |

| γGTP (IU/L) | 26 (9–32) | ACTH (pg/ml) | 30.8 (7.2–63.3) | ||

| BUN (mg/dL) | 9.7 (8.0–20.0) | Cortisol (μg/dl) | 15.1 (4.5–21.1) | ||

| Complete blood count | CRE (mg/dL) | 0.45 (0.46–0.79) | LH (mIU/ml) | 6.7 | |

| WBC (× 103/μL) | 6.3 (3.3–8.6) | UA (mg/dL) | 0.6 (2.6–7.0) | FSH (mIU/ml) | 26.1 |

| RBC (× 106/μL) | 4.74 (3.86–4.92) | HDL-cho (mg/dL) | 35 (40–96) | E2 (pg/ml) | < 19 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 14.5 (11.6–14.8) | LDL-cho (mg/dL) | 87 (70–139) | Testosterone (ng/ml) | 0.11 |

| Ht (%) | 41.4 (35.1–44.4) | TG (mg/L) | 254 (30–149) | FT3 (pg/ml) | 2.76 (2.30–4.30) |

| Plt (× 104/μL) | 21.4 (15.8–34.8) | UA (mg/dL) | 0.6 (2.6–7.0) | FT4 (ng/dl) | 0.84(0.90–1.70) |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0 (< 0.14) | GH (ng/ml) | 0.14 (0.13–9.88) | ||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 132 | IGF-I (ng/ml) | 90 | ||

| HbA1c (%) | 10.6 | PRL (ng/ml) | 60.1 (4.90–29.3) | ||

WBC white blood cell, Hb hemoglobin, Ht hematocrit, Plt platelet, RBC red blood cell, Ret reticulocytes, TP total protein, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, γGTP γ-glutamyltransferase, BUN blood urea nitrogen, CRE creatinine, UA uric acid, HDL-cho high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-cho low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG triglyceride, UA uric acid, ACTH adrenocorticotropichormone, LH Luteinizing hormone, FSH follicle stimulating hormone E2 estradiol, FT3 free triiodothyronine, free thyroxine, GH growth hormone, IGF-I insulin-like growth factor, PRL prolactin

Fig. 1.

Changes in body weight and HbA1 in the current case. Changes of HbA1c (red line) and bodyweight (blue line) are plotted. The patient in this case was hospitalized at X-19 month and X-10 month in our psychiatry department’s inpatient ward, and for at X month in our department’s inpatient ward

Discussion

We demonstrate here that the GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide was remarkably effective in reducing and maintaining HbA1c and body weight in an obese individual with T2D and schizophrenia.

GLP-1 receptor agonists have been gaining attention for their concomitant glucose-lowering and body weight-reducing effects as well as their cardio- and reno-protective effects [2]. It is known that effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on glycemia and body weight vary among various GLP-1 receptor agonists. For example, short-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g., exenatide and lixisenatide) and long-acting ones (e.g., liraglutide, semaglutide and dulaglutide) improve glycemia through different mechanisms: The short-acting ones improve postprandial glucose excursion primarily by delaying gastric emptying, and long-acting ones do so primarily by enhancing insulin secretin and suppressing glucagon secretion [6]. GLP-1 receptor agonists with small molecular weight (e.g., exenatide, lixisenatide, liraglutide and semaglutide) reduce body weight more efficiently than those with large molecular weight (e.g., dulaglutide and albiglutide) [7, 8]. It has been demonstrated that semaglutide is taken up into the central nervous system via the GLP-1 receptors expressed in ependymal cells, thereby directly acting on the hypothalamus to suppress appetite [9]; and it has been speculated that dulaglutide, having a molecular weight of 60 kDa, might less efficiently enter the central nervous system when compared with semaglutide, which has the considerably lesser molecular weight of 4 kDa. While further investigations are needed, the differing effects of dulaglutide and semaglutide on body weight reduction may well underlie the substantial body weight reduction obtained in the current case by switching from dulaglutide to semaglutide.

While the GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide was effective in the current case, effectiveness of GLP-1 receptor agonists in individuals with schizophrenia and T2D has been still controversial. It has been shown that the GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide once‐weekly improves glycemia control and reduce body weight in clozapine-treated obese schizophrenia patients with or without diabetes [10]. It has been also shown that the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide reduces body weight in obese individuals with severe mental illness on various anti-phycotics [11]. On the other hand, it has been demonstrated that exenatide once‐weekly failed to reduce body weight in obese, antipsychotic‐treated patients with schizophrenia [4]. Antipsychotics affect not only the dopamine D2 receptor but also multiple receptors in the brain (e.g., serotonergic, histaminergic and cholinergic receptors) [12]. Lack of clear body weight-reducing effects of GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide in the latter clinical trial suggests that the effect of exenatide may interact with dopaminergic signaling that is known to influence appetite regulation in the brain reward system [4]. However, precise mechanisms how antipsychotics and GLP-1 receptor agonists interact at molecular levels are not fully understood to date. In addition, the recent study by Gabery and his associates demonstrated liraglutide and semaglutide binds to GLP-1 receptors in different brain regions [9], suggesting that potential interactions between antipsychotics and GLP-1 receptor agonists on appetite and body weight reduction may not be uniform. Whether or not all GLP-1 receptor agonists are similarly effective in prevention and treatment of T2D and obesity in schizophrenia patients with or without certain antipsychotics requires adequately powered clinical trials.

Suicide attempts by overdosing on anti-diabetes drugs are often problematic and careful drug selection and patient counseling are important. In the current case, we chose semaglutide, luseogliflozin and metformin. It is well known that the overdose of metformin is associated with lactic acidosis [13]. It has been also reported that the overdose of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor may impair renal function [14]. Furthermore, the overdose of GLP-1 receptor agonist may cause sustained gastrointestinal adverse events including nausea and vomiting [15]. We chose anti-diabetes drugs with low risk of hypoglycemia as severe hypoglycemia can be life-threatening. We also asked the patient to visit us every other week to receive prescription of semaglutide, luseogliflozin and metformin for 2-week period. However, there is still a possibility of suicide attempts by overdosing on anti-diabetes drugs, and support from her family members is critical to prevent suicide attempts by overdosing.

In conclusion, the GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide, but not dulaglutide, is shown to effectively reduce and maintain HbA1c and body weight in an obese individual with type 2 diabetes and schizophrenia.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the patient for her contribution to this study. The authors also thank J. Kawada, H. Tsuchida and M. Kato for their technical assistance, and M. Yato, Y. Ogiso, and M. Nozu for secretarial assistance.

Author contributions

KN, TK and DY contributed to the analysis, collection, and interpretation of data and writing of the manuscript. NN, MS, SK, TH, YL, YT, KT, MM, TH, TS and YH contributed to the analysis, collection of data, and interpretation of data as well as critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and contributed to the analysis, collection and interpretation of pathological data and provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the version to be published. TK and DY are the guarantors of this work.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences (JSPS) [KAKENHI Grant Number: 26111004 (DY) and 20K19673 (LY)], and Grants for young researchers from Japan Association for Diabetes Education and Care (TK).

Availability of data and materials

Clinical data from the corresponding author are available upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

DY has received consulting/lecture fees from Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd., Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. DY also received grants from Arkray Inc., Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Taisho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, and Terumo Corporation. YH received lecture fees from Kowa and MSD. KN, TK, NN, MS, SK, TH, YL, YT, KT, MM, TH, KI and TS declare that they have no conflict of interest. All authors declare that they have no competing interests relevant to this study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Formal ethics approval was waived for this paper by the ethics committee of Gifu University Graduate School of Medicine due to its being a case report.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants followed the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Holt RI. Association between antipsychotic medication use and diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19:96. doi: 10.1007/s11892-019-1220-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kristensen SL, Rorth R, Jhund PS. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(10):776–785. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsen JR, Vedtofte L, Jakobsen MSL, et al. Effect of liraglutide treatment on prediabetes and overweight or obesity in clozapine- or olanzapine-treated patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatr. 2017;74(7):719–728. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishoy PL, Knop FK, Broberg BV, et al. Effect of GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment on body weight in obese antipsychotic-treated patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(2):162–171. doi: 10.1111/dom.12795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshimatu H, Sakata T. Behavioral therapy for morbid obesity (in Japanese) Nippon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2001;90:902–913. doi: 10.2169/naika.90.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suganuma Y, Shimizu T, Sato T, et al. Magnitude of slowing gastric emptying by glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists determines the amelioration of postprandial glucose excursion in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig. 2020;11(2):389–399. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pratley R, Aroda V, Lingvay I, et al. Semaglutide versus dulaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 7): a randomised, open-label, phase 3b trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:275–286. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yabe D, Nakamura J, Kaneto H, et al. PIONEER 10 investigators: safety and efficacy of oral semaglutide versus dulaglutide in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 10): an open-label, randomised, active-controlled, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:392–406. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabery S, Salinas CG, Paulsen SJ, et al. Semaglutide lowers body weight in rodents via distributed neural pathways. JCI Insight. 2020 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.133429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siskind DJ, Russell AW, Gamble C, et al. Treatment of clozapine-associated obesity and diabetes with exenatide in adults with schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial (CODEX) Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(4):1050–1055. doi: 10.1111/dom.13167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whicher CA, Price HC, Phiri P, et al. The use of liraglutide 3.0 mg daily in the management of overweight and obesity in people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and first episode psychosis: results of a pilot randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(6):1262–1271. doi: 10.1111/dom.14334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Megna JL, Schwartz TL, Siddiqui UA, et al. Obesity in adults with serious and persistent mental illness: a review of postulated mechanisms and current interventions. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2011;23(2):131–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lalau JD, Race JM. Lactic acidosis in metformin therapy: searching for a link with metformin in reports of 'metformin-associated lactic acidosis'. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2001;3(3):195–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2001.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura M, Nakade J, Toyama T, et al. Severe intoxication caused by sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor overdose: a case report. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2020;21(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s40360-019-0381-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotella JA, Wong A. Liraglutide toxicity presenting to the emergency department: a case report and literature review. Emerg Med Australas. 2019;31(5):895–896. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Clinical data from the corresponding author are available upon request.