Abstract

A regulatory gene-like open reading frame oriented oppositely to mdcL, coined mdcY, was found upstream from the structural genes of the mdcLMACDEGBH operon in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus KCCM 40902. To elucidate the function of this gene, mdcY was expressed in Escherichia coli, and the MdcY protein was purified to homogeneity. Its DNA binding activity and binding site were examined by gel retardation and footprinting assays in vitro and by site-directed mutagenesis of the binding sites in vivo. The regulator bound target DNA regardless of the presence of malonate, and the binding site was found centered at −65 relative to the mdcL transcriptional start site and contains a 12-bp palindromic structure (5′-ATTGTA/TACAAT-3′). Using a promoter fusion to the reporter gene luc, we found that the promoter PmdcY is negatively regulated by MdcY independent of malonate. However, the promoter PmdcL recovered its activity in the presence of malonate. When mdcY was introduced into A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 in which the gene is inactivated by an IS3 family element, malonate decarboxylase was significantly repressed in cultures growing in acetate, succinate, or Luria-Bertani medium. However, in cells growing in malonate, malonate decarboxylase was induced, indicating that MdcY is a transcriptional repressor and that malonate or a product resulting from malonate metabolism should be the intracellular inducer of the mdc operon.

Dimroth's group and our laboratory have extensively characterized malonate metabolism in Malonomonas rubra, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (2, 10, 14, 15, 18–20, 30). The first enzyme in the malonate metabolism, malonate decarboxylase, which catalyzes the decarboxylation of malonate to acetate, has also been studied in various other bacteria (6, 13, 18, 20, 30). Acinetobacter malonate decarboxylase is an oligomeric enzyme consisting of four subunits, α (65kDa), β (33kDa), γ (25kDa), and δ (11kDa), in a 1:1:1:1 stoichiometry (20). Recently, gene clusters from A. calcoaceticus, K. pneumoniae, M. rubra, and Pseudomonas putida encoding the component enzymes and proteins involved in the decarboxylation of malonate have been cloned and sequenced (2, 15, 19, 20). In the soil bacterium A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902, the mdc genes include mdcA, encoding malonate:ACP malonyltransferase, which replaces an acetyl group on the prosthetic group of the δ subunit by a malonyl group; mdcC, encoding acyl carrier protein; mdcD, encoding the decarboxylase γ subunit; mdcE, encoding a protein factor for stabilization of the complex or a co-decarboxylase; and the mdcGBH genes, encoding enzymes for posttranslational modifications (20). The mdc gene cluster of nine genes, mdcLMACDEGBH, is located on the genomic DNA of A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902, which is a bacterium isolated from soil and identified on the basis of malonate consumption (17). In addition to these, a potential repressor gene, mdcY, which is inactivated by insertion of a putative IS3 element (20), was discovered in the upstream region of this gene cluster, and it is predicted to be transcribed in the opposite direction of the mdc operon. In fact, it has been reported that A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 grown on acetate, succinate or Luria-Bertani (LB) medium also produces malonate decarboxylase constitutively (4).

An mdcY gene which is reconstructed by deletion of the IS3 element is predicted to encode a protein which is homologous to the transcriptional repressor GntR for the gluconate operon with about 25% identity and 45% similarity (12). Moreover, the gene structure and organization of malonate decarboxylase of A. calcoaceticus are similar to those of K. pneumoniae and P. putida (7, 15, 20). The malonate decarboxylase of P. putida is induced 28-fold by the addition of malonate (7). Also, the regulatory protein MdcR in K. pneumoniae has been described to play a role as an activator (25). The mdcR gene product, which is a LysR-type activator, activates the expression of the mdc genes in K. pneumoniae and represses the transcription of its own gene, mdcR, indicating a negative autoregulatory control similar to that of other LysR-type activators (25). These results suggest that MdcY in the upstream region of the mdc operon plays a role in the regulation of the mdc operon as well as the autoregulation of its own gene. However, little is known about the molecular mechanism of action of the mdcY gene product on the mdc operon in the soil bacterium A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902.

Here we report the expression and purification of the MdcY protein from the reconstructed mdcY gene, characterization of MdcY as a repressor, identification of the operator site region, and in vivo regulatory properties of MdcY or malonate as a repressor or inducer, respectively, in A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902. This is the first report of a repressor and inducer system in malonate metabolism in bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, oligonucleotide primers, and growth conditions.

All bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotide primers used in this study are shown in Table 1. A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 was grown under aerobic conditions at 30°C in a growth medium consisting of 0.6% malonic acid, 0.3% KH2PO4, 0.3% NH4Cl, 0.04% MgSO4 · 6H2O, and 0.01% FeSO4 · 7H2O. The pH was adjusted to 6.8 with KOH (18). All Escherichia coli strains were grown aerobically at 37°C in LB medium. For recombinant strains, media were appropriately supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), and tetracycline (10 μg/ml). Recombinant A. calcoaceticus cells (carrying chloramphenicol-resistant plasmids) were cultured in the above media supplemented with 25 μg of chloramphenicol per ml on plates and 25 μg of chloramphenicol per ml in liquid culture. DNA fragments were subcloned in pBluescriptK.SII+ and used to transform E. coli DH5α. For the expression of the mdcY gene in E. coli BL21(DE3) or E. coli NovaBlue(DE3), plasmid pET22b (Novagen) was used.

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Relevant characteristic(s) or sequence | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 | Wild type | 17; KCCMa |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | φ80 lacZΔM15 Δ(argF-lac)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) deoR thi-1 supE44 gyrA96 relA1 | 28 |

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−)gal dcm (DE3) | Novagen |

| NovaBlue(DE3) | endA1 hsdR17(rK12− mK12+)supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac[F′ proA+B+ lacIqZΔM15::Tn10](DE3) | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRK2013 | Helper plasmid | 8 |

| pBBR1MCS | 4,717-bp broad-host-range cloning vector; Cmr | 21 |

| pGL3-Basic | 4,818-bp promoterless, luciferase reporter vector; luc+ Ampr | Promega |

| pBluescript IIKS | Cloning vector; Ampr | Stratagene |

| pET22b | Overexpression vector; His6 affinity tag; Ampr | Novagen |

| pK124 | Pfu PCR fragment containing mdcY and inserted into EcoRV cleavage sites of pBluescript IIKS+; Ampr | This study |

| pK125 | Pfu PCR fragment containing 237-bp intergenic region of mdcY and mdcL gene and inserted into EcoRV cleavage sites of pBluescript IIKS+; Ampr | This study |

| pK129 | 2-kbp SacI-SalI fragment from pGL3-Basic inserted into SalI-SacI cleavage sites of pBluescript IIKS+; Ampr | This study |

| pK131 | 2,019-bp ApaI-SacI fragment from pK129 inserted into ApaI-SacI cleavage sites of pBBR1MCS (luciferase reporter gene in broad-host-range vector); Cmr | This study |

| pK133 | 230-bp HindIII-SspI fragment from pK125 inserted into HindIII-SmaI cleavage sites of pK131(PmdcY-luc+ fusion vector); Cmr | This study |

| pK134 | 284-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment from pK125 inserted into BglII-SmaI cleavage sites of pK131(Pmdc-luc+ fusion vector); Cmr | This study |

| pK137 | 1,156-bp NruI-KpnI fragment from PCR product containing promoter, mdcY, and a putative termination dyad symmetric sequence gene and inserted into SmaI-KpnI cleavage sites of pBBR1MCS, Cmr (complementation test vector containing mdcY) | This study |

| pK215 | 678-bp NdeI-XboI fragment from pK124 inserted into NdeI-XhoI cleavage sites of pET22b; Ampr | This study |

| Primers | ||

| General | ||

| C-1 | 5′-CGAACGCTATGGTGCTTCTCGCACGCCGATTCG-3′ | This study |

| C-2 | 5′-GAACGCCTCGAGCGATTTAGGCTGTAGACT-3′b | This study |

| C-com | 5′-GCATTGACATTTGCGCATGGG-3′ | This study |

| N-1 | 5′-TGGTGACATATGAACTCAATTGCGG-3′b | This study |

| N-2 | 5′-TGCGAGAAGCACCATAGCGTTCGCACAGCTCCTG-3′ | This study |

| N-com | 5′-TGGCAGGTGTCCACGTTTTGC-3′ | This study |

| Int-A | 5′-ATTTGAATAGAAAGAGGG-3′ | This study |

| Int-B | 5′-ACCTAGAATATTACCTAG-3′ | This study |

| Site-directed mutagenesisc | ||

| A-F | 5′-CACTGAATACAGATGCCGTATAACTATACCAAA-3′ | |

| A-R | 5′-TTTGGTATAGTTATACGGCATCTGTATTCAGTG-3′ | |

| B-F | 5′-GTACACTGAATACACCCAGGCTATAACTATACC-3′ | |

| B-R | 5′-GGTATAGTTATAGCCTGGGTGTATTCAGTGTAC-3′ | |

| C-F | 5′-CAAAGCATTGTACAGGCAATACAGATAGGCTA-3′ | |

| C-R | 5′-TAGCCTATCTGTATTGCCTGTACAATGCTTTG-3′ | |

| D-F | 5′-GTACAAAGCATTGTGGGCTGAATACAGATAGGC-3′ | |

| D-R | 5′-GCCTATCTGTATTCAGCCCACAATGCTTTGTAC-3′ | |

| E-F | 5′-GAGTACAAAGCATCCCACACTGAATACAGATAG-3′ | |

| E-R | 5′-CTATCTGTATTCAGTGTGGGATGCTTTGTACTC-3′ | |

| F-F | 5′-TATGTTTATTTGAGTGGGAAGCATTGTACACTG-3′ | |

| F-R | 5′-CAGTGTACAATGCTTCCCACTCAAATAAACATA-3′ | |

| G-F | 5′-ATTTATGTTTATTTGCCCACAAAGCATTGTACAC-3′ | |

| G-R | 5′-GTGTACAATGCTTTGTGGGCAAATAAACATAAAT-3′ | |

| H-F | 5′-GTATACAATTTATGTCCCTTTGAGTACAAAGC-3′ | |

| H-R | 5′-GCTTTGTACTCAAAGGGACATAAATTGTATAC-3′ | |

| I-F | 5′-ATTGAACAATTTACCCTTATTTGAGTACAAAGC-3′ | |

| I-R | 5′-GCTTTGTACTCAAATAAGGGTAAATTGTATACAAT-3′ | |

| J-F | 5′-CACCAAAAAAATTGTGGGCAATTTATGTTTATT-3′ | |

| J-R | 5′-AATAAACATAAATTGCCCACAATTTTTTTGGTG-3′ | |

| K-F | 5′-CATCACCAAAAAAATCCCATACAATTTATGTTT-3′ | |

| K-R | 5′-AAACATAAATTGTATGGGATTTTTTTGGTGATG-3′ |

Korean Culture Collection of Microorganisms, Seodaemun-Ku, Seoul, Korea.

Restriction enzyme cloning sites are underlined, and relevant mutagenized nucleotides are shown in italics.

The underlined bases in the sequences of the oligonucleotides used for site-directed mutagenesis represent the changes introduced into the wild-type sequence.

DNA manipulation and sequencing.

Routine molecular biology procedures and DNA manipulations were carried out by the methods described previously (28). The constructed plasmids more specific to this study are summarized in Table 1. Large-scale plasmid isolation was undertaken with a QIAGEN plasmid Midi kit. Restriction endonuclease, DNA ligase, calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (New England Biolabs), Turbo Pfu/Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene), and a Promega labeling system were used according to the manufacturers' instructions. DNA sequencing was performed on both strands for new constructs with the Tag DyeDeoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer) on an ABI 310 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems Division of Perkin-Elmer).

Primer extension assay.

Mapping of the transcriptional start site was carried out by a primer extension assay. Two synthetic oligonucleotides, Int-A and Int-B (∼8.1 × 105 cpm, 0.1 pmol, Table 1) were 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase, and each was hybridized to 15 μg of total RNA isolated from A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 cells grown at 30°C. The annealed primer was extended at 42°C for 90 min with 10 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Promega), and the extended products were analyzed by electrophoresis on denaturing sequencing gels (6%) followed by autoradiography. The same labeled oligonucleotide was used in parallel dideoxy chain termination sequencing reactions with pK134 template DNA to generate a size standard sequence ladder.

Reconstruction of mdcY by the deletion of orfAB.

In order to study the function of MdcY from A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902, the 144-bp N-terminal fragment between the primers N-1 and N-2 and the 572-bp C-terminal fragment between primers C-1 and C-2, which are separated by the IS3 element (orfAB), were PCR amplified independently with pK119 as a template (20) (Fig. 1A). The 692-bp fragment was then amplified with the primers N-1 and C-1 by using the 144- and 572-bp fragments as templates (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The Pfu PCR product was inserted into an EcoRV-cleaved fragment in pBluescriptK.SII+, yielding pK124. The nucleotide sequences of the PCR product and the flanking segment in pK124 were confirmed with universal primers (Promega). The 678-bp NdeI-XhoI fragment from pK124 was inserted into the NdeI-XhoI cleavage sites of pET22b (Novagen), yielding an in-frame ligation of the mdcY gene to the His tag coding region on pET22b, pK215. PCRs were performed with Pfu polymerase in a GeneAmp PCR cycler 2400 (Perkin-Elmer). A typical procedure consisted of 3 min at 95°C; 25 cycles of 40 s at 95°C, 40 s at 50°C, and 2 min at 72°C; and then 10 min at 72°C. During PCR, the elongation time was adapted to the length of the fragment to be amplified. The composition of the reaction mixture (50 μl) was recommended by the manufacturer of the polymerase (Stratagene).

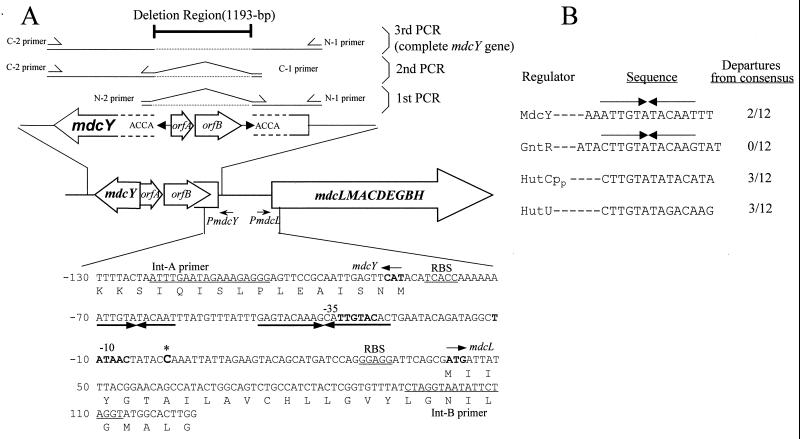

FIG. 1.

The mdc operon region of the A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 showing the schematic representation used for reconstruction of mdcY, construction of the luciferase reporter plasmid, and EMSA (A). The mdcY gene, which encodes a protein homologous with the transcriptional regulator gene product in A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 isolated from soil was inactivated by insertion of an IS element, orfA and orfB. Putative promoters (boldface letters) in the −10 and −35 region were predicted by database analysis based on the gram-negative promoter consensus sequence (11, 23); the region of dyad symmetry is indicated by horizontal arrows. RBS, ribosome binding site; all oligonucleotide primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. Sequence numbers are relative to the transcriptional start site of the mdc operon. (B) Consensus nucleotide sequences at the DNA location where transcription is regulated in the malonate catabolic system. The nucleotide sequence of the 249-bp EcoRI-HindIII fragment contains the mdc operator segment that displays identity to the common consensus operator at 10 of 12 positions. The region showing dyad symmetry in each sequence is indicated by convergent arrows. Shown is the comparison of the mdc operator region with the homologous regions of GntR from Bacillus subtilis (9, 12), HutCpp from Pseudomonas putida (12), and HutU from Klebsiella aerogenes (GenBank accession no. M19665).

Expression and purification of MdcY.

The mdcY gene was expressed as a His6-tagged fusion protein, and the protein was purified on an Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid column according to the manufacturer's instructions (Novagen). LB broth (200 ml) containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml was inoculated with 2 ml of an overnight culture of E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen) containing the plasmid for His-tagged MdcY. Cells were grown aerobically at 37°C to an A600 of 0.5, and then isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) was added to the culture to a concentration of 0.5 mM to induce the protein for 22 h at 20°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g, and then the protein in the cell extract was purified as recommended by Novagen for soluble native proteins on a His-Bind resin column. The estimation of the apparent native molecular weight was carried out with an analytical Superdex 200 PC 3.2/30 column (3.2-mm internal diameter by 300 mm, particle size, 13 to 15 μm), connected to a SMART System (Pharmacia), equilibrated with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.3]) at a flow rate of 70 μl/min, and by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) with 8 to 16% Tris-glycine.

EMSA with the mdcY-mdcL intergenic region.

For the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), a DNA fragment containing the mdcYL intergenic region and partial coding sequences of mdcY and mdcL was generated by PCR with the primers Int-A and Int-B (Table 1) with pK119 as the template. The 237-bp product was ligated into EcoRV-digested pBluescriptK.SII+ vector to yield the plasmid pK125 (Table 1). The probe used for the gel mobility shift assay (5) was prepared by the digestion of plasmid pK125 with EcoRI and HindIII to give a 249-bp fragment. To label the 3′ end of the HindIII site of the noncoding strand, the fragment was separated on a 5% polyacrylamide gel, eluted, and end labeled by filling in with Klenow fragment using [α-32P]dCTP, dGTP, dATP, and dTTP. The radiolabeled probe (2 × 105 cpm, 0.1 pmol) was mixed with different amounts of purified MdcY (1.2 to 4.8 nM) in binding buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.05 mg of poly(dI-dC)-poly(dI-dC) per ml, 6% glycerol] in a total volume of 20 μl. Sodium malonate was added to the reaction mixture at 5 min before the addition of the radiolabeled probe, to a final concentration of 50 to 500 μM. Incubation was carried out for 15 min at room temperature. The DNA-protein complex was separated from the unbound DNA fragment on a 5% native polyacrylamide gel with 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (28) as the electrophoresis buffer.

DNase I footprinting.

The footprinting method used was the Promega core footprinting system. After 10 min of preincubation at 4°C of the MdcY protein and the end-labeled 249-bp fragment (as described above for EMSA), which is the noncoding strand from the mdc operon, in the absence or presence of malonate (50 to 500 μM) in the binding buffer, the mixture was treated for 1 min at room temperature with 0.25 U of DNase I (Promega) in the presence of 2.5 mM CaCl2 and 5 mM MgCl2. The reaction was stopped by the addition 36 μl of DNase I stop solution (200 mM NaCl, 30 mM EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 100 μl of yeast RNA per ml). Nucleic acids were precipitated with ethanol, dissolved in 5 μl of sequencing loading buffer, and heated at 90°C for 3 min prior to electrophoresis through a 7 M urea–8% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide sequencing gel.

Luciferase assay.

In order to determine the role of MdcY, luciferase activity was measured in E. coli NovaBlue(DE3) containing plasmids pK131 (luc+), pK133 (PmdcY-luc+), or pK134 (PmdcL-luc+) (Table 1) in the presence or absence of MdcY and malonate (Table 2) (15). The cultures for the luciferase assay were grown in LB medium either with or without 20 mM malonate. The medium contained either 25 μg of chloramphenicol per ml (strains with plasmid pK131, pK133, or pK134) or 25 μg of chloramphenicol and 100 μg of ampicillin per ml (strains with pK215 plus pK133 or pK215 plus pK134). The 5 ml of LB medium containing the respective supplements was inoculated from a single colony and grown at 37°C with shaking overnight. The 5-ml overnight cultures were diluted 100-fold into fresh selective media and grown aerobically at 37°C to an A600 of 0.5. The samples were transferred to 22°C, and 0.5 mM IPTG was introduced appropriately. After 15 h, the samples were taken and assayed directly for luminescence in the Turner Designs model TD-20/20 luminometer (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). The effects of several potential inducers on the PmdcL activity were also assayed as described above, except that they contained 20 mM potential inducer respectively. Potential inducers used in this study were acetate, methylmalonate, propionate, succinate, and tartrate.

TABLE 2.

Activities of A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 PmdcY and PmdcL in E. coli

| Activity parametera | Result for E. coli NovaBlue(DE3) cells with plasmid(s)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pK131 | pK133 (PmdcY) | pK133 + pK215 | pK133 + pK215 | pK134 (PmdcL) | pK134 + pK215 | pK134 + pK215 | |

| Malonate | + | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Luciferase activity (%) | 3.4 | 100 | 20.5 | 18.1 | 20.5 | 2.0 | 28.8 |

Sodium malonate was added at a concentration of 20 mM. Luciferase activity was calculated with the data given in luxes per OD600 unit.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the promoter of the mdc operon.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed with the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), using pK134 containing the PmdcL-luc+-fused gene as the template. The synthetic oligonucleotides for site-directed mutagenesis are listed in Table 1.

Plasmids containing these transcription fusions were introduced into NovaBlue(DE3)/pK215.

Luciferase activity was measured as described previously.

Complementation experiment with mdcY-inactivated A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902.

The 1,330-bp DNA fragment amplified with the primers N-com and C-com, using as templates the 433-bp fragment amplified with the primers N-com and N-2 and the 918-bp fragment amplified with primers C-com and C-1 (Table 1), was digested sequentially with NruI and KpnI to generate a 1,156-bp fragment containing mdcY, its natural promoter, and a putative rho-independent terminator downstream of mdcY. This 1,156-bp DNA fragment was ligated into SmaI-KpnI-digested pBBR1MCS (21), a broad-host-range vector, to yield the 5.9-kbp plasmid pK137, containing the mdcY gene in the opposite orientation to Plac for a complementation experiment with mdcY-inactivated A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902. The test strains were prepared by transferring the recombinant plasmid into the mdcY-inactivated A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 by triparental mating with the helper plasmid pRK2013 (8). One loop each of overnight cultures of the recipient, donor, and helper strains, respectively, was resuspended in 0.5 ml of sterile distilled water. Samples of each suspension were mixed in a 2:1:1 ratio of recipient (A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902)-donor (E. coli DH5α strains with plasmids)-helper. An appropriate amount (40 μl) of the mixed suspension was spotted on the surface of an LB agar plate and further incubated for 3 to 6 h at 30°C. The cells grown on the L agar plate were resuspended in 1 ml of sterile distilled water, and 0.1 ml of the suspension was plated out on malonate plates containing 25 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. Chloramphenicol-resistant conjugants were isolated on the malonate media. Subsequently, the selected cells were inoculated into 5 ml of LB medium containing 0.6% succinate or 0.6% sodium acetate instead of malonate and 25 μg of chloramphenicol per ml and incubated overnight at 30°C with shaking. Two milliliters of the overnight-grown culture was transferred to 200 ml of fresh medium for further incubation. In order to measure induction or repression of malonate decarboxylase in various media, these cells were harvested when the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the culture reached 1.0.

Determination of malonate decarboxylase activity.

Malonate decarboxylase activity of A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 grown in various media was assayed in logarithmically growing cells as described by Byun and Kim (3). The protein concentration was estimated by the bicinchoninic acid assay as described by Redinbaugh and Turley (27). SDS-PAGE analysis of proteins was performed with the discontinuous buffer system of Laemmli (22); gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R250.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences obtained in this work have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF209728.

RESULTS

Transcriptional analysis and identification of the promoter of the mdc operon.

The 249-bp EcoRI-HindIII DNA fragment of the mdcYL intergenic region (Fig. 1A) contains a 12-bp segment (5′-ATTGTATACAAT-3′) that displays 83% nucleotide sequence identity to the GntR family operator (Fig. 1B). Total RNA isolated from wild-type A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 grown on malonate was used to map the 5′ ends of the mdc operon and mdcY mRNAs by primer extension. The transcript maps of the mdc operon were complex, in that multiple 5′ ends were revealed by primer extension. The location of the starts was confirmed at positions 37, 40, and 42 with respect to the A of the ATG start codon (Fig. 2). Examination of the DNA sequence upstream from the mdc operon start codon in the mapped 5′ end at −42 revealed a possible ς70 promoter with 5 and 3 bases conserved in both the −10 and −35 regions, separated by a 17-nucleotide spacing, similar to promoters with transcription start points initiating 7 ± 2 bp from the −10 hexamer (11, 23). Primer extension analysis of mdcY failed to reveal any 5′ mRNA ends within the upstream mdcY gene, despite many attempts (data not shown), which suggests that its level of expression is very low or that the 5′ end region is highly unstable.

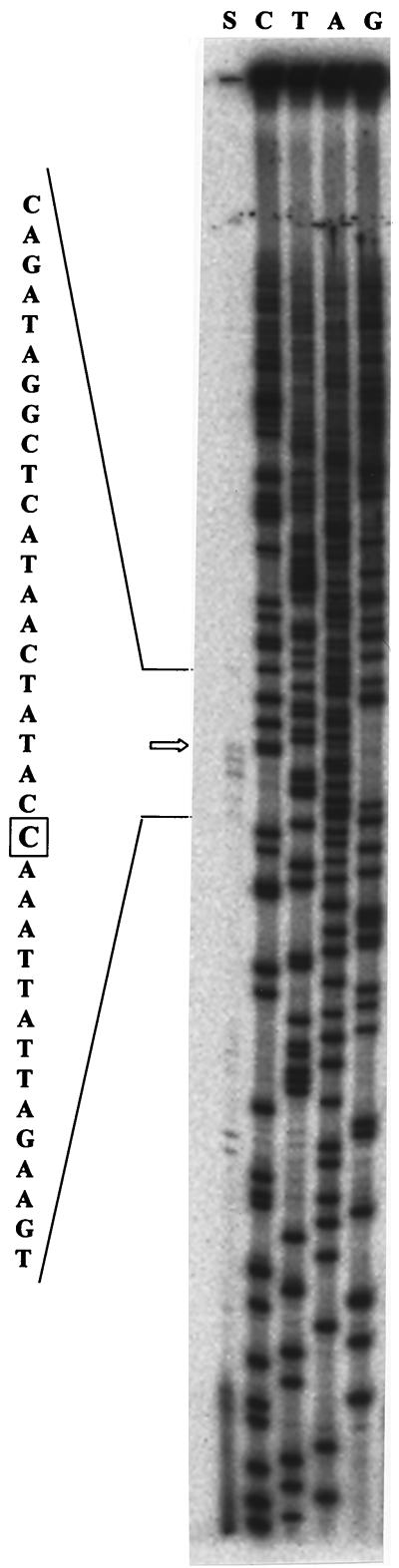

FIG. 2.

Transcript mapping of the 5′ ends of the mdc operon mRNA. Lanes: S, primer extension; G, A, T, and C, the mdc operon sequence ladder (generated with the oligonucleotide used for extension). The boxed C indicates the transcription initiation site.

Reconstruction of mdcY and expression in E. coli.

An mdcY gene was cloned as a part of the mdc operon and sequenced as described by Koo and Kim (20). Database analysis of mdcY revealed that it might encode a regulatory protein, suggesting that the gene product MdcY may regulate expression of the mdc operon (mdcLMACDEGBH genes) encoding proteins for malonate metabolism of A. calcoaceticus. In order to characterize MdcY in A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902, the 675-bp mdcY gene without the 1,193-bp orfAB insert was reconstructed by overlap extension PCR (Fig. 1A). Two segments of mdcY, which are divided by a putative IS3 element, were PCR amplified independently and then fused together in a subsequent ligation reaction. The reconstructed 675-bp mdcY gene encodes a protein with 224 amino acids, yielding a calculated mass of 25,871 Da.

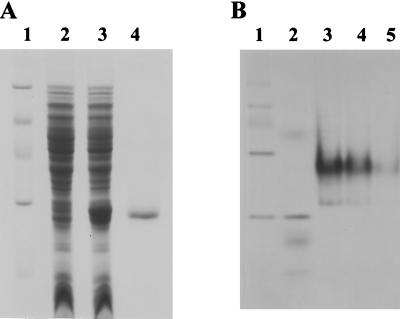

MdcY exhibited significant sequence similarity to bacterial regulatory proteins of the GntR family represented by the GntR repressor of Bacillus subtilis (9, 12, 16, 26, 32). Therefore, MdcY is likely to be a repressor for the mdc operon. The mdcY gene was overexpressed in E. coli by the T7 expression plasmid pET22b (Table 1). That is, the protein was successfully expressed from the plasmid pK215 in E. coli BL21(DE3) (Fig. 3A). The ratio of soluble to insoluble protein could be improved by lowering the temperature and decreasing agitation during growth. Most of the soluble His-tagged (on the C terminus) MdcY was bound to the His-Bind resin. After the column was washed, the protein was eluted in a purity of greater than 95% (Fig. 3A). The molecular mass of the His-tagged MdcY protein as determined by SDS-PAGE is 26.5 ± 1.5 kDa (Fig. 3A). Estimation of the native molecular weight of purified MdcY with an analytic Superdex 200 PC 3.2/30 column connected to a SMART System (Promega) showed that 70% of a tetramer (106 kDa) and 30% of a dimer (58 kDa) form eluted under nondenaturing conditions. Purified His-tagged MdcY protein electrophoresed under native conditions also revealed a major band at 106 kDa (Fig. 3B). This result is consistent with a tetrameric structure of MdcY as described above.

FIG. 3.

Electrophoretic analysis of mdcY expression by 12% SDS–PAGE (A). Lanes: 1, molecular mass markers (20.1, 30, 43, 67, and 94 kDa); 2 and 3, crude extracts of cells without or with induction of His-tagged MdcY by IPTG, respectively; 4, purified MdcY. (B) Eight to 16% Tris-glycine native PAGE. Lanes 1 and 2 contained Pharmacia high (67, 140, 232, 440, and 669 kDa)- and low (30, 43, 67, 94 kDa)-molecular-mass markers, respectively. Lanes 3 to 5 contained 10.5, 7, and 3.5 μg of purified MdcY, respectively.

EMSA with the mdcYL intergenic DNA segment.

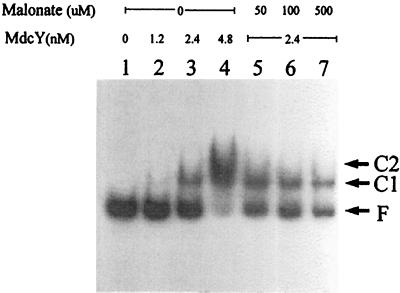

MdcY protein from E. coli BL21(DE3) bearing plasmid pK215 was subjected to gel retardation analysis with a probe DNA fragment carrying the mdcYL intergenic region. As shown in Fig. 4, the mobility of the specific 249-bp DNA fragment that contained the mdcYL intergenic region was shifted upon the addition of purified MdcY. Binding was almost completely abolished, when 10-fold excess of unlabeled probe was added to the reaction mixture 5 min before addition of labeled DNA. However, an excess amount (0.5 to 1 μg) of a nonspecific competitor, poly(dI-dC)-poly(dI-dC), that is routinely used in gel mobility shift experiments had no effect on the formation of the MdcY-mdcYL intergenic DNA segment complex (data not shown). The binding assay was also performed in the presence of different malonate concentrations (50 to 500 μM) in order to determine the effect of malonate on complex formation. As shown in Fig. 4, malonate had no concentration-dependent effect on the formation of complex.

FIG. 4.

Electrophoretic mobility of the MdcY-operator complexes. Increasing amounts of purified MdcY (1.2 to 4.8 nM) were added to a 249-bp (0.1 pmol, 2 × 105 cpm) DNA fragment containing the putative regulatory sites in the intergenic region of the mdcY and mdcL genes in the absence (lanes 1 to 4) or presence (lanes 5 to 7) of malonate at different concentrations (50 to 500 μM). In the presence of MdcY, two MdcY-operator complexes (C) were formed. F, free DNA.

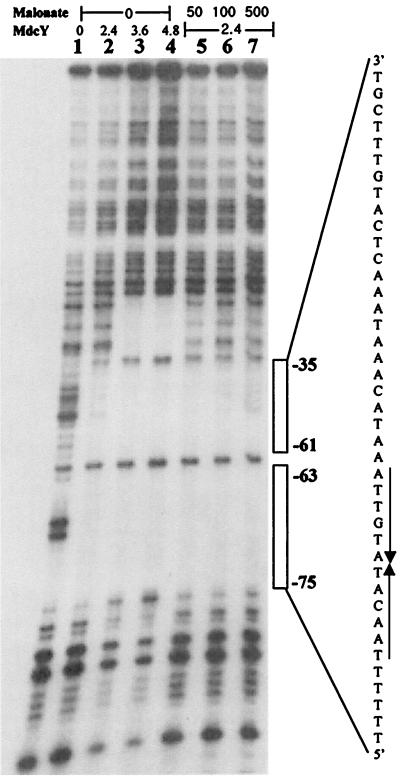

DNase I footprinting assay.

The location of the MdcY-binding site was identified by a DNase I footprinting assay using the purified MdcY and an end-labeled 249-bp DNA fragment containing the mdcYL intergenic region. In the absence of MdcY, DNase I cleavage produced a regular pattern of bands (Fig. 5). In contrast, upon addition of the MdcY protein, a broad protected region was detected, including the 12-bp palindromic structure (5′-ATTGTA/TACAAT-3′) present in this particular region of DNA. DNase I footprinting showing a protected region extending from −35 to −75 starting from the transcriptional start site of the mdc operon was also performed in the presence of different amounts of malonate (50 to 500 μM) in order to confirm the EMSA results. These results are consistent with the indication from the EMSA that malonate had no effect on the binding of MdcY to the mdc operator.

FIG. 5.

MdcY-mediated protection of the mdc operator against digestion by DNase I. Lanes 1 to 4, target DNA (0.1 pmol, 2 × 105 cpm) was incubated in the absence or in the presence of MdcY (the number above each lane indicates the nanomolar concentration of MdcY protein). In lanes 5 to 7, target DNA and 2.4 nM MdcY were incubated with 50, 100, and 500 μM malonate, respectively. The vertical arrows beside the nucleotide sequence indicate a palindromic structure.

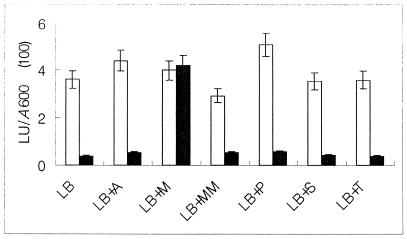

Luciferase assay with PmdcY-luc and PmdcL-luc fusion vectors in vivo.

The mdcYL intergenic region was assayed for promoter activity with a luciferase-based reporter gene system. The mdcYL intergenic region containing the promoters of both mdcY and mdcL (PmdcY and Pmdc) (Fig. 1) was introduced into the reporter plasmid pK131 (Table 1) to create pK133 and pK134, respectively. Both the PmdcY-luc(pK133) and PmdcL-luc(pK134) fusions were expressed in E. coli NovaBlue(DE3). PmdcY(pK133) was a stronger promoter than PmdcL(pK134) (Table 2). In the presence of MdcY(pK215), PmdcY activity was reduced about 5-fold, whereas PmdcL activity was decreased more than 10-fold. Malonate had no influence on PmdcY activity in the presence of MdcY, whereas it completely restored PmdcL activity from MdcY inhibition (Table 2). E. coli NovaBlue (DE3)/pK134+pK215 grown on LB medium containing malonate induced luciferase activity 10-fold more than in the absence of malonate. On the other hand, the bacteria grown on LB medium containing acetate, propionate, succinate, or tartrate showed very low luciferase activity (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Expression of PmdcL-luc+ and PmdcL-Luc+/MdcY in the presence of potential inducers. Transcriptional responses in luxes (LU) per OD600 unit (A600) of E. coli NovaBlue(DE3) containing PmdcL (open columns) or PmdcL/MdcY (solid columns) were measured in the presence of potential inducers. Data are averaged from at least three independent aerobic cultures grown in LB medium plus 20 mM the indicated carbon sources (pH 6.8). The error bar represents the standard deviation from the mean (<10%). A, acetate; M, malonate; MM, methylmalonate; P, propionate; S, succinate; T, tartrate.

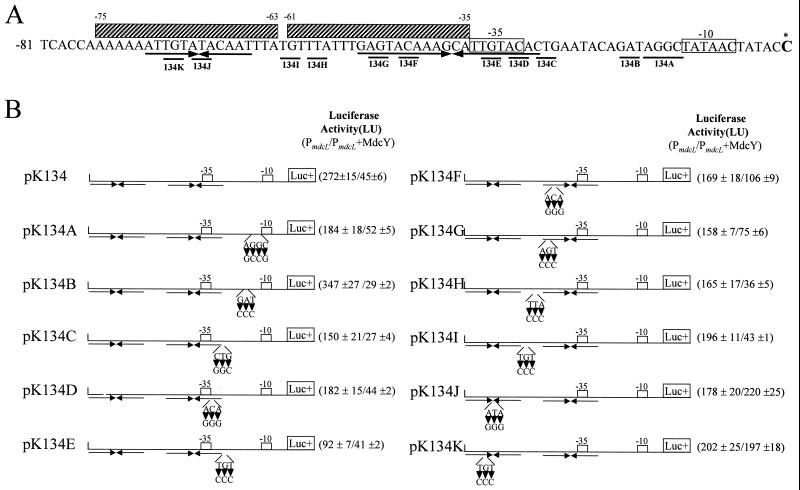

Mutation of operator site of the mdc operon.

In order to investigate the role of the cis-acting element in the expression of the A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 mdc operon, mutations in the mdcYL intergenic region containing two inverted repeats (Fig. 7A) were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis, and the mutated mdc regulatory region was subcloned into the transcription reporter vector pK131. As shown in Fig. 7B, when three bases were changed on either the left conserved sequences or the left arm of the right inverted repeat, as in transcription fusions pK134F, pK134G, pK134J, and pK134K, higher levels of luciferase activity were observed in cells containing the repressor, the MdcY protein. Figure 7B also shows that nucleotide changes in the putative −35 region of the mdc operon promoter lead to a low level of luciferase activity (pK134E). The point mutation in the spacing between the −10 and −35 regions, however, resulted in a very much higher level of transcriptional activity (pK134B). Site-directed mutagenesis in the mdc operator region has thus indicated a negative regulatory role for this cis-acting element in the expression of mdcLMACDEGBH.

FIG. 7.

Changes in transcriptional activity due to mutation in the PmdcL regulatory region. (A) Nucleotide sequence of the mdcYL intergenic region. Nucleotides shown by underlined letters have been mutated. The hatched rectangles denote the sites evident in footprinting reactions. (B) Schematic representations of the fragments cloned into the transcription reporter vector pK131 and the corresponding luciferase (Luc+) activity of each construct. Site-directed mutations were carried out by the method of the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The arrowheads indicate base changes. All mutant constructs and the control plasmids were assayed for luciferase activity. The luciferase activity values and standard deviations (<10%) represent the averages of three independent assays.

Complementation experiments in a mdcY-inactivated A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902.

The function of MdcY was also tested in a mdcY-inactivated A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 containing pK137. When the mdcY gene was introduced as the pK137 shuttle vector into A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 isolated from soil, in which the gene is knocked out by the insertion element, the Acinetobacter cells grown on acetate, succinate, or LB medium did not produce malonate decarboxylase. However, malonate-grown Acinetobacter sp. strain KCCM 40902 containing pK137 did induce malonate decarboxylase, suggesting that MdcY and malonate are a repressor and possibly an inducer, respectively, for the mdc operon.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this work was to investigate the transcriptional regulation of the mdc operon in response to malonate and a regulatory protein and to identify this regulatory protein, MdcY. Sequence analysis of MdcY has shown that this protein possesses a helix-turn-helix motif at its N terminus, which is typical for DNA-binding proteins (9, 12, 16, 24, 29, 32). Additionally, the deduced amino acid sequence of mdcY has been scanned against the GenBank and EMBL databases. MdcY shares homology with a number of proteins that belong to the GntR family of bacterial transcriptional regulators. It is 24% identical to a transcriptional regulator, GntR, from B. subtilis (GenBank accession no. P10585), 24% identical to the regulatory protein FadR from E. coli (GenBank accession no. S01288), and similar to many other members of the family. Based on sequence homology to the common helix-turn-helix domain of GntR family transcriptional repressors (9, 12, 32), a DNA binding sequence, ERELAAQFGVSRMTVRRALR, in this family was proposed. The N-terminal helix-turn-helix motif, located between amino acids 34 and 53 (EQELCERYGASRTPIREALK), of the MdcY protein is the most conserved part of the consensus sequence. This binding domain is 45% identical and 65% similar to the GntR consensus sequence. The similarities in sequence, molecular size, and predicted secondary structure to GntR suggest that the MdcY protein can be classified as a member of the GntR transcription regulator family. However, it does not show similarity to the C-terminal region encoding a gluconate-binding motif.

Furthermore, it has been reported that insertional inactivation of mdcY by a putative IS3 element leads to constitutive expression of the A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 mdc operon, which suggests that MdcY is a repressor of the mdc operon (20). To verify that MdcY indeed regulates the genes responsible for metabolism of malonate via protein-DNA interaction, the mdcY gene was reconstructed through deletion mutagenesis by PCR (Fig. 1). MdcY was overproduced in E. coli, purified to homogeneity (Fig. 3A), and used in an in vitro binding study. The binding sites of the MdcY protein identified by gel mobility shift and DNase I footprinting assays are very similar to the common operator sequence, 5′-CTTGTATANANNTA-3′, of the GntR family (9, 12, 16, 26, 32) of transcription regulators (Fig. 5). The MdcY binding site identified is located in the intergenic region of mdcYL, extending from −35 to −75 starting from the transcriptional start site of the mdc operon, and it also includes the 12-bp dyad symmetric structure (5′-ATTGTA/TACAAT-3′) representing a typical portion of the mdc operator (Fig. 5).

In spite of the similarity to other GntR systems (1, 9), malonate had no effect on the binding of MdcY to the mdc operator (Fig. 4). The respective positions of the binding sites for the MdcY and GntR family regulators might cause the difference in the effects of the mechanism of action (9). That is, the mdc operator is located from −35 to −75 starting from the transcriptional start site of the mdc operon (Fig. 5), placing the repressor in the immediate vicinity of the binding site of the RNA polymerase (Fig. 7A). The B. subtilis GntR, however, protects a gnt operator region, between −10 and +15, which overlaps with the promoter region (9).

In order to evaluate the transcriptional regulation of the mdc operon, the promoter activity for mdcY and the mdc operon was determined in the presence or absence of MdcY and malonate in vivo with E. coli NovaBlue(DE3). It seems that MdcY binding to the mdcY operator site overlapping the promoter site inhibits its own transcription (Fig. 5 and 7A), but malonate did not affect this inhibition (Table 2). MdcY also significantly inhibits the transcription of the mdc operon, but malonate as an inducer overcomes the inhibition and induces malonate decarboxylase synthesis (Table 2).

The mdcY-inactivated Acinetobacter KCCM 40902 produces malonate decarboxylase constitutively in the presence or absence of malonate (4). However, repression was restored in the mdcY-inactivated strain KCCM 40902 when the mdcY gene was provided in trans, as a plasmid carrying mdcY (pK137). Of course, the control plasmid (pBBR1MCS) did not affect the repression of malonate decarboxylase synthesis (data not shown). These results show that the constitutive mutation is complemented by the reconstructed mdcY gene supplied in trans. It is concluded that the mdcY gene encodes a regulatory protein (MdcY), which represses synthesis of malonate decarboxylase in response to malonate limitation.

It seems that MdcY and RNA polymerase coexist on the operator and promoter in a joint nonproductive complex that can be triggered to make RNA by the addition of malonate (Table 2 and Fig. 4). Although we clearly showed that MdcY represses mdc gene expression, the induction of malonate decarboxylase in mdcY-inactivated Acinetobacter sp. strain KCCM 40902 containing mdcY as a plasmid pK137 was relatively weak. Although the mdcY gene structure and its function in malonate decarboxylase of A. calcoaceticus are similar to those of K. pneumoniae (14, 15, 30), the structural organization and regulation of the mdc operon in A. calcoaceticus are different from those of K. pneumoniae. The genes comprising the K. pneumoniae mdc operon are transcribed from two separate promoters (PmdcL and PmdcR), which are positively regulated by the malonate activator (MdcR) (25), whereas transcriptional regulation of the mdc operon of A. calcoaceticus is mediated by MdcY, which binds to the mdcYL intergenic region containing the 12-bp inverted repeated structure (5′-ATTGTA/TACAAT-3′) and probably represses the initiation of transcription.

These studies enabled us to formulate a model for regulation of the mdc operon from A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 by the mdc repressor. The binding of MdcY to its operator represses initiation of transcription from both promoters. RNA polymerase that has escaped from the initial transcribed sequence after addition of malonate allows transcription to proceed. It has been known that LacR blocks the isomerization of the closed complex to the open complex in transcription initiation (31). The evidence presented here clearly indicates that binding of the A. calcoaceticus KCCM 40902 MdcY protein to the operator results in suppression of transcription of the mdc operon, but releases suppression in the presence of malonate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a grant (97-05-01-06-01-5) from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ajdić D, Ferretti J J. Transcriptional regulation of the Streptococcus mutans gal operon by the GalR repressor. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5727–5732. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5727-5732.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg M, Hilbi H, Dimroth P. Sequence of a gene cluster from Malonomonas rubra encoding components of the malonate decarboxylase Na+ pump and evidence for their function. Eur J Biochem. 1997;245:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byun H S, Kim Y S. Assays for malonate decarboxylase. Anal Biochem. 1994;223:168–170. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byun H S, Kim Y S. Metabolic routes of malonate in Pseudomonas fluorescens and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;28:107–111. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carey J. Gel retardation. Methods Enzymol. 1991;208:103–117. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)08010-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chohnan S, Fujio T, Takaki T, Yonekura M, Nishihara H, Takamura Y. Malonate decarboxylase of Pseudomonas putida is composed of five subunits. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;169:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chohnan S, Kurusu Y, Nishihara H, Takamura Y. Cloning and characterization of mdc genes encoding malonate decarboxylase from Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:311–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figurski D H, Helinski D R. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1648–1652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujita Y, Miwa Y. Identification of an operator sequence for the Bacillus subtilis gnt operon. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4201–4206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Handa S, Koo J H, Kim Y S, Floss H G. Stereochemical course of biotin-independent malonate decarboxylase catalysis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;370:93–96. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harley C B, Reynolds R P. Analysis of E. coli promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:2343–2361. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.5.2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haydon D J, Guest J R. A new family of bacterial regulatory proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;63:291–295. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90101-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilbi H, Dehning I, Schink B, Dimroth P. Malonate decarboxylase of Malonomonas rubra, a novel type of biotin-containing acetyl enzyme. Eur J Biochem. 1992;207:117–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoenke S, Dimroth P. Formation of catalytically active acetyl-S-malonate decarboxylase requires malonyl-coenzyme A:acyl carrier protein transacylase as auxiliary enzyme. Eur J Biochem. 1999;259:181–187. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoenke S, Schmid M, Dimroth P. Sequence of a gene cluster from Klebsiella pneumoniae encoding malonate decarboxylase and expression of the enzyme in Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1997;246:530–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izu H, Adachi O, Yamada M. Gene organization and transcriptional regulation of the gntRKU operon involved in gluconate uptake and catabolism of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:778–793. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim S J, Kim Y S. Isolation of a malonate-utilizing Acinetobacter calcoaceticus from soil. Korean J Microbiol. 1985;23:230–234. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim Y S, Byun H S. Purification and properties of a novel type of malonate decarboxylase from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29636–29641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koo J H, Jung S B, Byun H S, Kim Y S. Cloning and sequencing of genes encoding malonate decarboxylase in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1354:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koo J H, Kim Y S. Functional evaluation of the genes involved in malonate decarboxylase by Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. Eur J Biochem. 1999;266:683–690. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovach M E, Phillips R W, Elzer P H, Roop II R M, Peterson K M. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. BioTechniques. 1994;16:800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lisser S, Margalit H. Compilation of E. coli mRNA promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1507–1516. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.7.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pabo C O, Sauer R T. Protein-DNA recognition. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:293–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.001453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng H-L, Shiou S-R, Chang H-Y. Characterization of mdcR, a regulatory gene of the malonate catabolic system in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2302–2306. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2302-2306.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porco A, Peekhaus N, Bausch C, Tong S, Isturiz T, Conway T. Molecular genetic characterization of the Escherichia coli gntT gene of GntI, the main system for gluconate metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1584–1590. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1584-1590.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Redinbaugh M G, Turley R B. Adaptation of the bicinchoninic acid protein assay for use with microtiter plates and sucrose gradient fractions. Anal Biochem. 1986;153:267–271. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schell M A. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:597–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmid M, Berg M, Hilbi H, Dimroth P. Malonate decarboxylase of Klebsiella pneumoniae catalyses the turnover of acetyl and malonyl thioester residues on a coenzyme-A-like prosthetic group. Eur J Biochem. 1996;237:221–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0221n.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Straney S B, Crothers D M. Lac repressor is a transient gene-activating protein. Cell. 1987;51:699–707. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tong S, Porco A, Isturiz T, Conway T. Cloning and molecular genetic characterization of the Escherichia coli gntR, gntK, and gntU genes of GntI, the main system for gluconate metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3260–3269. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3260-3269.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]