Abstract

In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, many exoproduct virulence determinants are regulated via a hierarchical quorum-sensing cascade involving the transcriptional regulators LasR and RhlR and their cognate activators, N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone (3O-C12-HSL) and N-butanoyl-l-homoserine lactone (C4-HSL). In this paper, we demonstrate that the cytotoxic lectins PA-IL and PA-IIL are regulated via quorum sensing. Using immunoblot analysis, the production of both lectins was found to be directly dependent on the rhl locus while, in a lasR mutant, the onset of lectin synthesis was delayed but not abolished. The PA-IL structural gene, lecA, was cloned and sequenced. Transcript analysis indicated a monocistronic organization with a transcriptional start site 70 bp upstream of the lecA translational start codon. A lux box-type element together with RpoS (ςS) consensus sequences was identified upstream of the putative promoter region. In Escherichia coli, expression of a lecA::lux reporter fusion was activated by RhlR/C4-HSL, but not by LasR/3O-C12-HSL, confirming direct regulation by RhlR/C4-HSL. Similarly, in P. aeruginosa PAO1, the expression of a chromosomal lecA::lux fusion was enhanced but not advanced by the addition of exogenous C4-HSL but not 3O-C12-HSL. Furthermore, mutation of rpoS abolished lectin synthesis in P. aeruginosa, demonstrating that both RpoS and RhlR/C4-HSL are required. Although the C4-HSL-dependent expression of the lecA::lux reporter in E. coli could be inhibited by the presence of 3O-C12-HSL, this did not occur in P. aeruginosa. This suggests that, in the homologous genetic background, 3O-C12-HSL does not function as a posttranslational regulator of the RhlR/C4-HSL-dependent activation of lecA expression.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic human pathogen that produces a wide spectrum of exoproduct virulence determinants and secondary metabolites (33, 44, 53, 56). These include elastase, alkaline protease, LasA protease, exotoxin A, phospholipase C, exoenzyme S, hydrogen cyanide, and pyocyanin. P. aeruginosa also synthesizes two lectins termed PA-IL and PA-IIL (21, 26). These lectins appear to function as adhesins (66) as well as cytotoxins for respiratory epithelial cells (1, 2, 5). PA-IL, which exhibits specificity for the sugar galactose (21), is a tetrameric protein consisting of four 12.75-kDa subunits (21, 49). The gene encoding the PA-IL lectin gene has been isolated from P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (3). Subsequent sequence analysis identified an open reading frame (ORF) of 369 bp corresponding to the lectin structural gene, later termed pa-1L (3, 4) and here renamed lecA to conform with standard genetic nomenclature. PA-IIL is approximately 12 to 13 kDa (24) and exhibits a high specificity for fucose (19, 22, 26). PA-IL and PA-IIL in addition to mannose affinity have both been shown to interact with the ABO(H) and P blood group glycosphingolipid antigens which may contribute to the tissue infectivity and pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa (27). However, in contrast to many Pseudomonas virulence determinants, there is little information concerning lectin expression at the molecular level. Cell density and age of the culture are known to affect lectin synthesis, and the production of PA-IL and PA-IIL lectins and that of several other virulence factors have been reported to be coregulated (23, 25), suggesting the existence of common regulatory mechanisms.

The expression of multiple virulence and survival genes in P. aeruginosa is cell density dependent and relies on a cell-cell communication system termed “quorum sensing.” This generic term is now commonly used to describe the phenomenon whereby the accumulation of a diffusible, low-molecular-weight signal molecule (sometimes referred to as a “pheromone” or “autoinducer”) enables individual bacterial cells to sense when the minimal population unit or “quorum” of bacteria has been achieved for a concerted population response to be initiated (15). Quorum sensing is thus an example of multicellular behavior and modulates a variety of physiological processes including bioluminescence, swarming, swimming and twitching motility, antibiotic biosynthesis, biofilm differentiation, plasmid conjugal transfer, and the production of virulence determinants in animal, fish, and plant pathogens (for reviews, see references 10, 15, 29, and 57).

P. aeruginosa employs N-acylhomoserine lactones (AHLs) as quorum-sensing signal molecules and has evolved a sophisticated regulatory hierarchy linking quorum sensing to virulence and survival in the stationary phase (38, 52). Two separate quorum-sensing circuits (termed las and rhl), each of which possesses an AHL synthase (LasI or RhlI, respectively) and a sensor-regulator (LasR or RhlR, respectively), modulate gene transcription in response to increasing AHL concentrations (6, 17, 18, 37, 46, 47, 68). The AHLs that signal within the las and rhl systems are N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone (3O-C12-HSL) and N-butanoyl-l-homoserine lactone (C4-HSL), respectively. Together, the two systems comprise a hierarchical cascade that coordinates the production of virulence factors and stationary-phase genes (via the alternative sigma factor, RpoS [38, 52]). Individually, each system's sensor-regulator modulates a regulon comprising an overlapping set of genes. However, the las system directly regulates the rhl system, thus providing overall coordination of quorum sensing and temporal gene expression in response to cell-to-cell communication (31, 67).

In the present paper, we demonstrate that (i) the production of both PA-IL and PA-IIL is regulated via quorum sensing, (ii) the expression of the lecA gene is directly dependent on both RhlR/C4-HSL and RpoS, and (iii) the addition of exogenous 3O-C12-HSL to P. aeruginosa does not advance or inhibit RhlR/C4-HSL-driven lecA expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli JM109 and XL1-Blue MR were used for cloning experiments. E. coli CC118 λpir was used for the construction of pCol2, pCol4, and pCol9, and E. coli S17-1 λpir was used for reporter gene studies and conjugation experiments. Bacteria were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or on LB agar plates (58). For studying growth-phase-dependent lectin production, strains were grown at 37°C for 24 h in 250 ml of LB medium with shaking at 200 rpm. Samples were taken approximately every 2 h over the first 16 h and finally at 24 h. Where indicated, C4-HSL, C6-HSL, or 3O-C12-HSL was added to the growth medium prior to inoculation, at concentrations ranging from 0 to 100 μM. Standard methods were used for the preparation of competent cells and for plasmid electroporation into E. coli and P. aeruginosa (58, 62). Conjugal transfer was performed as described by Kaniga et al. (36). Where required, kanamycin, chloramphenicol, and ampicillin were added at 25, 34, and 50 μg/ml, respectively, for E. coli. For P. aeruginosa, kanamycin, streptomycin, and carbenicillin were added at 250, 150, and 300 μg/ml, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or phenotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PAO1 | Wild type | Holloway collection |

| PANO67 | NTGa mutant derived from PAO1 | 34 |

| PAO1 lecA::lux | lecA::luxCDABE genomic reporter fusion in PAO1 | This study |

| PAOR | lasR mutant derived from PAO1 | 38 |

| PDO100 | rhlI mutant derived from PAO1 | 6 |

| PDO111 | rhlR mutant derived from PAO1 | 6 |

| PAO1 rpoS negative | rpoS mutant derived from PAO1 | 35 |

| E. coli | ||

| JM109 | recA1 supE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 thi Δ(lac-proAB) F′ [traD36 proAB+ lacIqlacZΔM15] | 72 |

| S17-1 λpir | thi pro hsdR hsdM+ recA RP4-2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 λpir | 61 |

| CC118 λpir | Δ(ara-leu) araD ΔlacX74 galE galK phoA20 thi-1 rps-1 rpoB argE(Amp) recA thi pro hsdRM+ RP4-2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 λpir | 32 |

| XL1-Blue MR | Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSB421 | EcoRI fragment containing luxCDABE cassette and Kmr element cloned into pUC18Not | 70 |

| pUCP18 | Like pUC18 but additional 1.8-kb stabilizing fragment for maintenance in Pseudomonas spp. | 60 |

| pKNG101 | Suicide vector carrying the sacBR genes for sucrose sensitivity; Smr | 36 |

| pNQluxIII | luxCDABE genes cloned into pNQ705 | This laboratory |

| pNQ705 | Cmr suicide plasmid derived from pGP704 | 45 |

| Supercos1 | Cosmid vector, pBR322-derived ori, Ampr | Stratagene |

| pMW47.1 | 2-kb PstI PAO1 DNA insert (rhlRI) in pUCP18 | 37 |

| pMW471.2 | 1.3-kb PstI-EcoRI fragment containing rhlR in pUCP18 | 37 |

| plasR | lasR locus cloned into pUCP18 | This laboratory |

| pCF6b | 32.6-kb PAO1 DNA insert containing the lecA gene in Supercos1 | This study |

| pCF1 | 4.4-kb PstI fragment derived from pCF6b containing the lecA gene in pUCP18 | This study |

| pCF2 | 3.1-kb PstI-HindIII fragment derived from pCF6b containing the lecA gene in pUCP18 | This study |

| pCF3 | 600-bp EcoRI fragment derived from pCF6b containing the lecA gene in pUCP18 | This study |

| pCol2 | PCR fragments encoding the lecA gene region cloned into EcoRI and KpnI sites upstream and downstream of luxCDABE Kmr in pSB421 | This study |

| pCol4 | ∼8-kb NotI fragment from pCol2 cloned into pKNG101 | This study |

| pCol9 | 496-bp PCR fragment, encoding the lecA upstream region, cloned into the NotI site of pNQluxIII | This study |

NTG, N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine.

DNA manipulation.

DNA was manipulated by standard methods (58). Restriction enzymes (Promega UK Ltd.) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Agarose gel electrophoresis and Southern blot transfer were performed essentially as described by Sambrook et al. (58). DNA probes were labeled with digoxigenin and detected using the DIG Luminescent Detection Kit supplied by Boehringer Mannheim. The IsoQuick kit (ORCA Research Inc.) was employed for the isolation of chromosomal DNA of P. aeruginosa. For isolation of plasmid DNA from E. coli, the Qiagen Mini and Midi kits (Qiagen Ltd.) were used.

RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA of P. aeruginosa was isolated according to the hot phenol-chloroform procedure described by Oelmüller et al. (48) with the modifications described by Gerischer and Dürre (20). For Northern blots, RNA was separated in denaturing formaldehyde gels and transferred to Hybond N+ nylon membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Ltd.) as described by Sambrook et al. (58). Probes were labeled with [α-33P]ATP using the Random Primers Labeling kit (Life Technologies Inc.). The probe was generated by PCR using the primers lecA.1F (ATATATCGGAGATCAATCATGGCTTGG) and lecA.1R (CGTTCAGACCGAAGCGTGTTGAAGC). The DNA template was pCF1. Hybridizations and washings were performed as previously described (20). Fragment sizes were estimated by comparison with the 0.16- to 1.77-kb RNA ladder from Life Technologies Inc.

Primer extension analysis.

Primer extension analysis was carried out as described by Gerischer and Dürre (20) except that SuperScript reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies Inc.) was used. The oligonucleotide used was RNA2 (ACCTGCCCTGCTTCGTTATTAG).

S1 nuclease analysis.

For S1 nuclease analysis, single-stranded DNA was synthesized and labeled with α-35S-dATP using a T7 sequencing kit from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Ltd. The sequencing instructions of the manufacturer were modified as follows. After denaturation of plasmid DNA and annealing of the respective oligonucleotide (RNA2), 3 μl of labeling mix, 1 μl of α-35S-dATP (10 μCi), and 2 μl of T7 polymerase (1.5 U/ml) were added and incubated at 37°C for 3 min. After addition of 1 μl of deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (800 μM each) and incubation at 37°C for 15 min, the reaction was stopped by phenol-chloroform extraction, and subjected to ethanol precipitation. The DNA pellet was suspended in 20 μl of H2O and stored at −20°C. Labeled DNA (0.25 μg) and RNA (10 to 40 μg) were mixed, dried, and incubated at 85°C for 10 min after the addition of 15 μl of hybridization buffer (40 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)] [pH 7.0], 1 mM EDTA, and 400 mM NaCl in 80% [vol/vol] formamide). Hybridization was performed at 40°C for 4 h. RNA and single-stranded DNA were removed by the addition of 300 μl of S1 mapping buffer (40 mM sodium acetate [pH 5.0], 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM ZnCl2, 20 U of S1 nuclease per ml, and 20 μg of denatured salmon sperm DNA per ml) and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by phenol-chloroform extraction after the addition of 6 μl of 10% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 30 μl of 0.2 M EDTA (pH 8.0), and 30 μl of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 8.0) followed by ethanol precipitation and suspension of the precipitate in 5 μl of H2O.

PCR.

PCR amplifications were performed in 100-μl volumes as described previously (71).

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis.

Automated nonradioactive sequencing reactions were carried out using the BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit in conjunction with a 373A automated sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems). For radioactive sequencing, the T7 sequencing kit from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Ltd. was used. Sequence analysis and database searches were performed with the Genetics Computer Group (Madison, Wis.) software packages and the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST server (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). For sequence comparisons, the program Gap (complete protein sequences) or BestFit (for truncated protein sequences) was used. Genes encoding tRNAs were identified using the tRNAscan-SE program (http://www.genetics.wustl.edu/eddy/tRNAscan-SE/) (39).

Synthesis of AHLs.

C4-HSL, C6-HSL, and 3O-C12-HSL were synthesized essentially as described previously by Chhabra et al. (8). AHLs were dissolved in acetonitrile before being added to growth medium.

Detection of lectins by Western blotting.

P. aeruginosa cells grown in LB medium as described above were suspended to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0 in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer and lysed by sonication. Prior to electrophoresis, samples were boiled and loaded onto SDS–15% polyacrylamide gels and either stained with Coomassie brilliant blue or electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose. PA-IL and PA-IIL were detected on immunoblots using the respective monospecific polyclonal antibody (13) followed by an anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase conjugate and developed with diaminobenzidine and H2O2 as described by Harlow and Lane (30).

Cloning of the lecA gene.

Based on the structural gene coding for PA-IL cloned from P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (3, 4), the oligonucleotide primers lecA.1F and lecA.1R were designed (for sequence, see “RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis”) and used to amplify a 599-bp fragment from P. aeruginosa PAO1 by PCR. This fragment was labeled with digoxigenin and used to probe a PAO1 cosmid library constructed in the Supercos cosmid vector (Stratagene). Four positive cosmids were identified and designated pCF5a, pCF9a, pCF6b, and pCF10a. Southern blot analysis of the four cosmids revealed that the probe hybridized with a 4.4-kb PstI fragment, a 7-kb HindIII fragment, and a 0.6-kb EcoRI fragment in each of the four clones. The probe also hybridized to equivalent-size restriction fragments from chromosomal DNA, digested with the same restriction enzymes, confirming that the four cosmid clones are derived from P. aeruginosa PAO1 (data not shown). Cosmid pCF6b was chosen for subcloning, and subsequently, a 4.4-kb PstI fragment, a 3.1-kb HindIII-PstI fragment, and a 0.6-kb EcoRI fragment were cloned separately into the vector pUCP18 (60), resulting in plasmids pCF1, pCF2, and pCF3, respectively.

Construction of lecA::luxCDABE reporter fusion.

For construction of the E. coli-based lecA::luxCDABE reporter plasmid, pCol9, a DNA fragment containing the region upstream of lecA was amplified by PCR, incorporating NotI restriction sites, using the primers Col21 (CCGGTTCGACCCCGGCTGCGGCCGCCATTGTGTTTCCTGGCGTTCAGC) and Col22 (CGACGATGGTAATGACAGCGGCCGCATTCTAGATAATCGACGTTACC). The resulting 496-bp promoter fragment was cloned in the correct orientation into the unique NotI site in pNQluxIII to create pCol9. For the PAO1 chromosomal reporter construct, the 5′ and 3′ regions of the lecA gene were PCR amplified using the primers Col1 (CCCGGGCACCATTGTGTTTCCTGGCGTTCAGCCGACTTC) and Col2 (CCCGGGATTGACCGGAATTCCTCAGCTGTTGCCAATCTTCATGACCAG) and primers Col3 (CGACGTGCGGGGTACCCCTGGCAATAACTCCGGCTCGTT) and Col4 (GGTACAGGTTGGCGGGGTACCGCGTGCAATCGTACAGGC), respectively. The 5′ PCR fragment was cloned in the correct orientation into the EcoRI site upstream of luxCDABE in pSB421 (70), while the 3′ PCR fragment was cloned in the correct orientation into the KpnI site downstream of luxCDABE in pSB421, resulting in plasmid pCol2. The NotI fragment containing luxCDABE Kmr flanked by the lectin sequence was cloned into the unique NotI site in pKNG101 (36), resulting in plasmid pCol4. Finally, chromosomal integration was achieved using the protocol described by Kaniga et al. (36) and confirmed by Southern blotting and PCR analysis (data not shown).

Time- and cell-density-dependent measurement of bioluminescence.

Bioluminescence was determined as a function of cell density using a combined, automated luminometer-spectrometer (the Anthos Labtech Lucy1). Overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa were diluted 1:100 in fresh medium, and 0.2 ml was inoculated into microtiter plates. Luminescence and OD495 were automatically determined every 30 min. Luminescence is given in relative light units (RLU) divided by OD495. For bar charts, the sum of the RLU/OD495 readings taken over the growth curve between 4.5 and 10 h was calculated and presented as a percentage of the control (no exogenous AHL added) and denoted as relative cumulative units (percentage of control).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence data reported here have been submitted to the GenBank database under accession no. AF229814.

RESULTS

PA-IL and PA-IIL production is positively regulated by the las and rhl quorum-sensing systems.

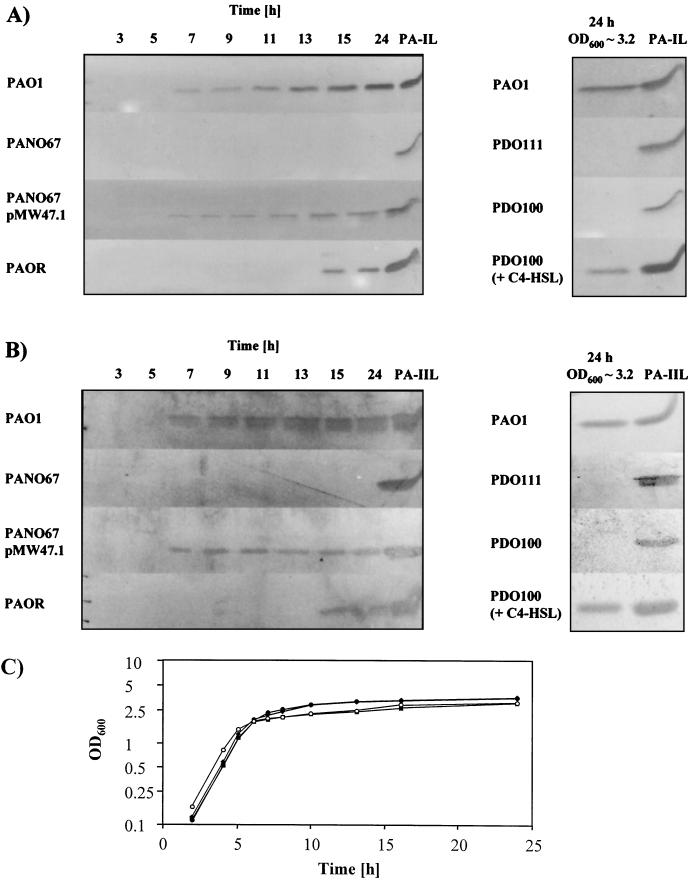

Whole-cell protein extracts prepared from P. aeruginosa PAO1 cells harvested at 2-h intervals throughout growth were analyzed by immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific for PA-IL or PA-IIL. Neither lectin was detected in samples taken during the exponential stage of growth; however, at high cell densities, during the transition to stationary phase, production of both lectins was observed (Fig. 1). To determine whether quorum sensing is involved in the regulation of PA-IL and PA-IIL, their production was studied in P. aeruginosa PANO67. This is a pleiotropic PAO1 mutant, which lacks the ability to produce many different virulence factors and secondary metabolites, and although it produces 3O-C12-HSL (indicative of a functional lasRI locus), it is unable to synthesize C4-HSL (34, 37, 38, 69). PANO67 can be restored to wild type by the introduction of rhlRI but not lasR on a multicopy plasmid (37). Immunoblot analysis of PANO67 extracts prepared from cells taken at different time points throughout growth revealed that PANO67 does not produce either PA-IL or PA-IIL. However, transformation of PANO67 with pMW47.1 (containing the rhlRI locus) restored the growth-phase-dependent production of PA-IL and PA-IIL (Fig. 1A and B), suggesting that the rhl locus is required for lectin synthesis in P. aeruginosa. PANO67 transformed with the pUCP18 vector alone did not produce either lectin (data not shown). Further evidence that both lectins are regulated via quorum sensing was provided by studying lectin production in the P. aeruginosa mutant strains PDO100 (rhlI negative) and PDO111 (rhlR negative) (6). In both strains, PA-IL and PA-IIL production was abolished. Addition of C4-HSL to cultures of PDO100 overcame the rhlI mutation and restored lectin levels to that of the wild type (Fig. 1A and B). Furthermore, in the lasR mutant strain PAOR, production of both lectins was severely down regulated such that they were detected only during the late stationary phase (Fig. 1A and B).

FIG. 1.

Production of PA-IL (A) and PA-IIL (B) by P. aeruginosa PAO1, PANO67, PANO67(pMW47.1), PAOR, PDO100, and PDO111. For strains PAO1, PANO67, PANO67(pMW47.1), and PAOR, samples for immunoblot analysis were taken every 2 h and processed as described in Materials and Methods over the first 15 h and finally at 24 h (left panels). For PDO100 and PDO111, samples taken after 24 h were analyzed (right panels). As a control, the rightmost lane in each panel contained the purified PA-IL or PA-IIL lectin. For panel A, immunoblots were probed with a monospecific polyclonal antibody to PA-IL, and for panel B, immunoblots were probed with an antibody to PA-IIL. Growth curves (C) are shown for P. aeruginosa PAO1 (○), PANO67 (⧫), PANO67(pMW47.1) (■), and PAOR (●). All strains were grown in LB medium at 37°C and entered stationary phase after approximately 6 h. Strains PDO100 and PDO111 showed very similar growth curves (data not shown).

Cloning and sequence analysis of the lecA gene.

The sequence published for the ATCC 27853 pa-IL gene (here renamed lecA) region contained only 18 bp upstream of the structural gene (3, 4). To obtain the complete promoter region for further sequence analysis and reporter gene construction, the lecA gene region of PAO1 was cloned, resulting in plasmids pCF1, pCF2, and pCF3 with inserts of 4.4, 3.1, and 0.6 kb, respectively (see Materials and Methods for details). Expression of the recombinant lecA gene in E. coli occurred only when it was transformed with the plasmid pCF3. E. coli transformed with the plasmid pCF1 or pCF2 failed to express the recombinant PA-IL protein, as determined by immunoblotting (data not shown). Plasmid pCF3 contains only a 627-bp EcoRI fragment. Thus, it seemed probable that expression in E. coli(pCF3) was under the control of the pUCP18 lac promoter.

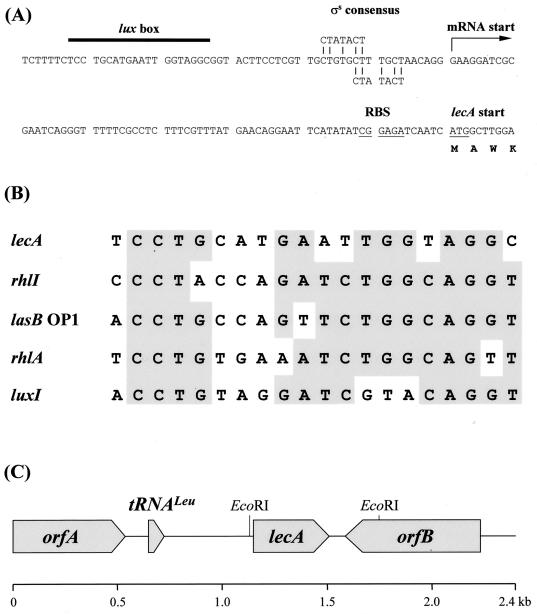

A 2,407-bp stretch of the putative lecA gene region of pCF1 was sequenced by primer walking, and the sequence was deposited as GenBank accession no. AF229814. DNA sequence analysis revealed an ORF of 369 bp, commencing with an ATG start codon and terminating with two consecutive stop codons, TGA and TAA. The putative PAO1 ORF is almost identical to the PA-IL lectin gene from P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853. One mismatch between the nucleotide sequences was identified, but the deduced amino acid sequences for the PA-IL proteins from the two strains were identical. Sequence comparison revealed a putative ribosome binding site (GGAGA) located 7 bp upstream of the ATG start codon, as has previously been described by Avichezer et al. (4) for strain ATCC 27853. A putative operator sequence, similar to the lux box upstream of luxI of Vibrio fischeri, was identified centered 112 nucleotides upstream of the ATG start site. This 20-bp sequence, although not an inverted repeat, does show significant sequence similarity to the putative luxI, rhlA, and rhlI and the lasB-OP1 operators (Fig. 2A and B). A potential Rho-independent RNA polymerase terminator was present immediately downstream of lecA. Further analysis identified the presence of a putative tRNALeu gene and a truncated ORF upstream of lecA (Fig. 2C). The deduced amino acid sequence of the truncated ORF (orfA) showed significant similarity to the AtoS sensor protein of E. coli and to other histidine protein kinases (data not shown). Downstream of lecA, a second ORF (orfB) was identified. Database searches using the deduced amino acid sequence of orfB did not reveal any significant similarity to any other proteins.

FIG. 2.

The lecA upstream DNA sequence (A); a comparison of the lux box-like elements located upstream of the genes rhlI, luxI, lecA, lasB, and rhlA (B); and a schematic representation of the lecA locus (C). (A) The putative lecA lux box is indicated by a black bar, and the putative mRNA start point is indicated by an arrow. The proposed ribosome binding site (RBS) and the ATG start codon are underlined. Potential ςS consensus sequences are aligned with the upstream region (short vertical lines). (B) Grey boxes indicate that at least four of five nucleotides are identical. lux box sequences were obtained from reference 9 (luxI and rhlA), reference 37 (rhlI), reference 55 (lasB-OP1), and this work (lecA). (C) The organization of orfA, the putative tRNALeu, lecA, and orfB is shown.

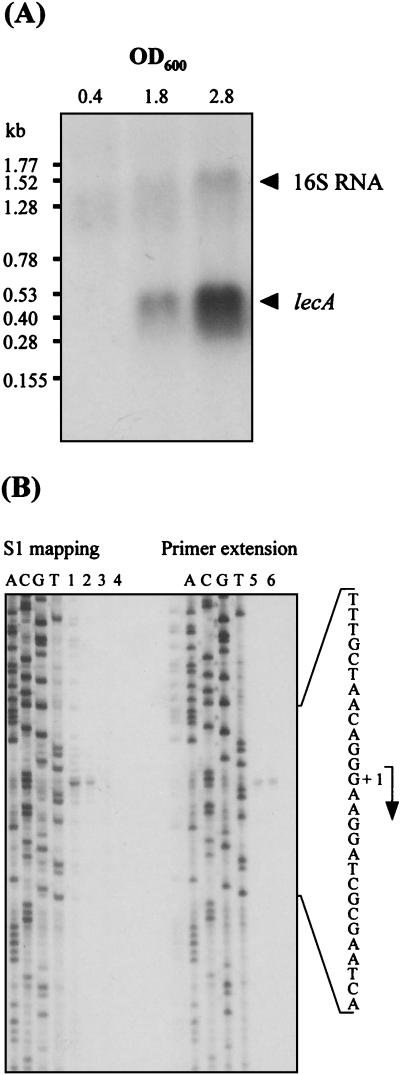

lecA transcript analysis.

For Northern blot analyses, RNA was isolated from P. aeruginosa cells harvested during mid-exponential, early stationary, and late stationary phase. A lecA-specific signal was obtained only with RNA isolated from stationary-phase cells with a transcript length of approximately 500 bp indicating a monocistronic organization (Fig. 3A). The transcriptional start site of lecA was determined by primer extension and S1 nuclease analysis, using oligonucleotide RNA2 (see Materials and Methods) and RNA isolated from stationary-phase cells. Identical signals, at position −70 relative to the ATG start codon, were obtained by both methods (Fig. 3B). Therefore, the putative lecA lux box is centered 42 nucleotides upstream of the transcriptional start site (Fig. 2A). Two potential ςS −10 regions (CTGTGCT and CTTTGCT) were located in positions −18 to −12 and −13 to −7 upstream of the transcription start point (Fig. 2A), with five of the seven bases being identical to the consensus sequence (CTATACT) (12).

FIG. 3.

Northern blot analysis of lecA transcripts (A) and mapping of the 5′ end of lecA transcripts (B). (A) RNA was isolated from cells harvested during exponential phase (OD600 = 0.4), early stationary phase (OD600 = 1.8), and late stationary phase (OD600 = 2.8). The lecA structural gene was amplified using the primers lecA.1F and lecA.1R and the template pCF1. The resulting PCR product was labeled with [α-33P]ATP and used as a probe. (B) For S1 nuclease analysis, 35S-radiolabeled DNA was synthesized using oligonucleotide RNA2 and hybridized to 10 μg of total RNA isolated from cells harvested in early stationary phase (OD600 = 1.8). After S1 nuclease digestion, 50% (lane 1), 20% (lane 2), and 5% (lane 3) of the radiolabeled DNA were subjected to electrophoresis. A control reaction mixture containing radiolabeled DNA but no RNA is shown in lane 4. The sequencing ladders were obtained by using the same oligonucleotide in DNA sequencing reactions. For primer extension analysis, the 33P-radiolabeled oligonucleotide RNA2 complementary to the mRNA of the lecA gene was hybridized to 10 μg of total RNA isolated from early-stationary-phase cells (OD600 = 1.8) of P. aeruginosa. Of the resulting cDNA, 10 and 20% were subjected to electrophoresis on the gel presented (lanes 5 and 6, respectively).

RhlR and its cognate autoinducer C4-HSL are the transcriptional activators of lecA expression.

To characterize the transcriptional regulation of lecA, lecA::luxCDABE gene fusions were constructed in both P. aeruginosa and E. coli (for details, see Materials and Methods). The P. aeruginosa-based reporter contains a single, chromosomally located lecA::luxCDABE Kmr fusion (lecA::lux). The E. coli reporter contains the plasmid pCol9, which is based on the lecA::luxCDABE gene fusion cloned into the medium-copy-number vector pNQ705.

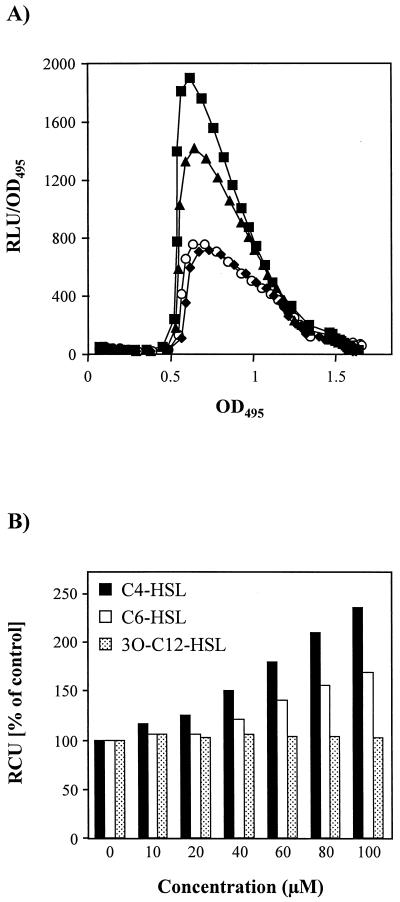

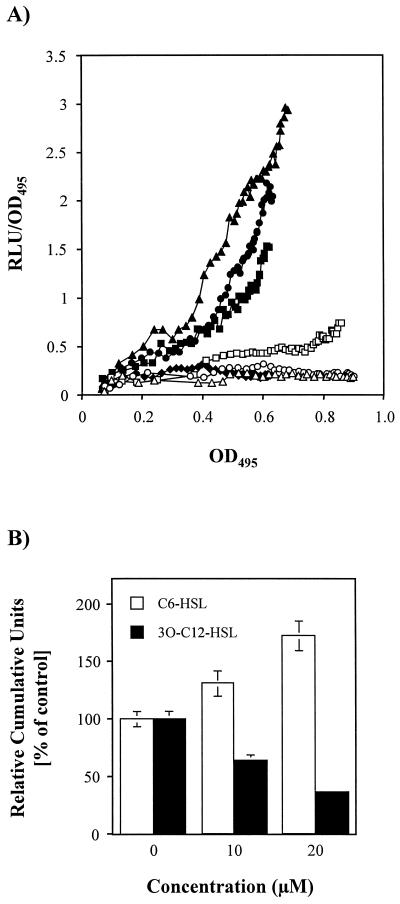

In P. aeruginosa, the PA-IL lectin reporter fusion was induced at the beginning of stationary phase (Fig. 4A), confirming the data obtained by immunoblot analysis. Addition of exogenous C4-HSL or C6-HSL (from 0 to 100 μM) at the time of inoculation increased reporter expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B) but did not advance it (Fig. 4A). C4-HSL was, however, more active than C6-HSL, increasing the expression more than twofold. In contrast, the addition of exogenous 3O-C12-HSL up to 100 μM had no effect on lecA expression (Fig. 4). Cultures grown in the presence or absence of AHLs showed very similar growth curves (data not shown). The rapid decay of light output (Fig. 4A) in stationary phase probably reflects the exhaustion of the substrates (reduced flavin mononucleotide and long-chain fatty aldehyde) required for the bioluminescence reaction (43, 70) since both Western blot (Fig. 1) and Northern blot (Fig. 3) data indicate that lecA is expressed in stationary phase and a comparable decay of light output was also observed with a P. aeruginosa lecA::lux mutant strain constitutively expressing lecA::lux due to a Tn5 insertion upstream of the reporter (K. Winzer and P. Williams, unpublished data).

FIG. 4.

Expression of lecA::lux in P. aeruginosa. (A) P. aeruginosa lecA::lux was grown in LB medium in the absence of exogenously added AHL (○) or in the presence of 100 μM C4-HSL (■), C6-HSL (▴), or 3O-C12-HSL (⧫). RLU and OD495 were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The results represent a single experiment, although the experiment was repeated three times with similar results. (B) Response of the P. aeruginosa lecA::lux fusion to C4-HSL, C6-HSL, and 3O-C12-HSL. Relative cumulative light units (RCU) were calculated as a percentage of the control (no exogenous AHL added) as described in Materials and Methods. For each AHL concentration, the experiment was repeated three times.

For E. coli S17-1(pCol9), only background levels of lecA expression were detected, consistent with the immunoblot data described earlier. This indicates that the lecA gene, when under the control of its native promoter, is not expressed in the heterologous genetic background of E. coli. When E. coli S17-1 was transformed with plasR, pMW471.2 (rhlR), and pMW47.1 (rhlRI), only pMW47.1 induced an approximately threefold increase in the level of lecA transcription (Fig. 5A). In further experiments, C4-HSL or 3O-C12-HSL was added to either E. coli S17-1(pCol9)(pMW471.2) or E. coli S17-1(pCol9)(plasR), at concentrations of 5, 10, and 15 μM. While the addition of exogenous C4-HSL to S17-1(pCol9)(pMW471.2) induced a concentration-dependent increase in the level of lecA expression (Fig. 5A), the addition of 3O-C12-HSL to S17-1(pCol9)(plasR) failed to increase expression (data not shown). Addition of C4-HSL to S17-1(pCol9) and S17-1(pCol9)(pUCP18) also failed to induce lecA transcription (data not shown). These results suggest that lecA expression is directly regulated by RhlR/C4-HSL but not by LasR/3O-C12-HSL.

FIG. 5.

Effect of rhlR, rhlRI, and lasR on the expression of lecA::lux in E. coli S17-1(pCol9) (A) and influence of C6-HSL and 3O-C12-HSL on RhlR/C4-HSL-driven expression of lecA::lux in E. coli S17-1 [pCol9] pMW47.1 (B). (A) Expression of lecA::lux in E. coli S17-1(pCol9) in the presence of pMW47.1 (rhlRI) (□), plasR (▵), pUCP18 (○), and pMW471.2 (rhlR) with no C4-HSL (⧫), 5 μM C4-HSL (■), 10 μM C4-HSL (●), or 15 μM C4-HSL (▴) added. Strains were grown in LB medium in the presence of the indicated additives. RLU and OD495 were measured every 30 min as described in Materials and Methods. The results represent a single experiment, although the experiment was repeated three times with similar results. (B) Response of E. coli S17-1(pCol9)(pMW471.2) grown in the presence of 20 μM C4-HSL to C6-HSL and 3O-C12-HSL. RLU and OD495 were determined every 30 min. Relative cumulative light units were calculated as a percentage of the control (no exogenous AHL added) as described in Materials and Methods. For each AHL concentration, the experiment was repeated three times.

When E. coli S17-1(pCol9)(pMW471.2) was grown in the presence of C4-HSL (20 μM) together with 3O-C12-HSL (10 and 20 μM, respectively), a concentration-dependent decrease in expression was observed, relative to the levels detected following the addition of exogenous C4-HSL alone (Fig. 5B). 3O-C12-HSL, therefore, interferes with RhlR/C4-HSL-dependent activation of lecA::lux in an E. coli background. In contrast, addition of 10 or 20 μM C6-HSL to E. coli S17-1(pCol9)(pMW471.2) in the presence of 20 μM C4-HSL enhanced RhlR-dependent lecA expression (Fig. 5B).

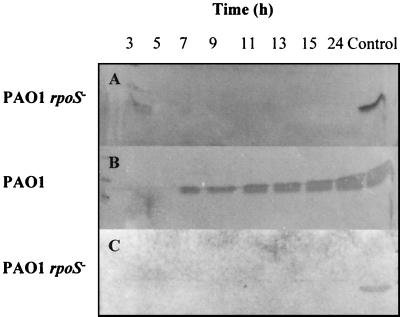

Production of PA-IL and PA-IIL is RpoS dependent.

Given the presence of an RpoS (ςS) consensus sequence upstream of the lecA transcription start site, we used immunoblot analysis to monitor the production of both PA-IL and PA-IIL throughout growth. Figure 6 shows that synthesis of both lectins is abolished in a P. aeruginosa rpoS mutant.

FIG. 6.

Production of PA-IL (A and B) and PA-IIL (C) by P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 (B) and PAO1 rpoS negative (A and C). For each strain, samples for immunoblot analysis were taken every 2 h and processed as described in Materials and Methods over the first 15 h and finally at 24 h. All strains were grown in LB medium at 37°C and showed similar growth curves, each entering stationary phase after approximately 6 h (data not shown). For panels A and B, immunoblots were probed with a monospecific polyclonal antibody to PA-IL, and for panel C, immunoblots were probed with an antibody to PA-IIL. As a control, the rightmost lane in each panel contained the purified PA-IL (A and B) or PA-IIL (C) lectin. PAO1 wild-type samples probed with antibody to PA-IIL are shown in Fig. 1B.

DISCUSSION

The lasRI and rhlRI quorum-sensing circuits of P. aeruginosa have previously been shown to regulate numerous virulence factors (including elastase, alkaline protease, LasA protease, exotoxin A, pyocyanin, pyoverdine, and hemolysin), components of the Xcp secretion apparatus, the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS, cyanide, rhamnolipids, twitching motility, superoxide dismutases, catalase, and biofilm formation in a cell-density-dependent manner (18, 31, 37, 38, 47, 50, 65, 69). Quorum sensing thus appears to constitute a global regulatory system in P. aeruginosa. Indeed, Whiteley et al. (67) have estimated that up to 4% of P. aeruginosa genes are regulated by quorum sensing. By screening a library of random lacZ transcriptional fusions in a lasI-rhlI double mutant on media supplemented or not with 3O-C12-HSL and C4-HSL, they identified mutations in some 39 P. aeruginosa genes, many of which have no homologues in the databases (67). Their approach did not, however, identify the genes coding for either PA-IL or PA-IIL, which, from the present work, we can now add to the repertoire of gene products now known to be controlled via quorum sensing in P. aeruginosa. The genes examined by Whiteley et al. did not represent the entire set of quorum-sensing-dependent genes, as no saturation mutagenesis was performed, and consequently, some genes that have been described as quorum sensing regulated have not been identified in their experiments (67).

For both PA-IL and PA-IIL, mutation of lasR delayed but did not abolish lectin production. The loss of both lectins in PANO67 and their restoration following the introduction of the plasmid-borne rhl locus suggested that RhlR/C4-HSL rather than LasR/3O-C12-HSL was likely to be directly responsible for controlling their expression. In addition, these data suggest that, although the las system regulates the rhl system, in late stationary phase the rhlRI locus can be activated in a LasR/3O-C12-HSL-independent manner such that the loss, by mutation, of lasR delays, but does not abolish, lectin synthesis.

Immunoblot analysis of lectin production did not, however, reveal whether RhlR/C4-HSL or LasR/3O-C12-HSL could activate lectin production independently, as has been observed for the lasB, rhlAB, and xcp operons (6, 7, 47, 51, 52). Furthermore, the immunoblot data could not exclude the possibility that lectin synthesis was not directly activated by the quorum-sensing circuitry but by other, as yet unidentified regulators, which were themselves controlled via quorum sensing.

To obtain more detailed insights into the quorum-sensing-dependent control of PA-IL regulation required that we first clone the P. aeruginosa structural gene encoding PA-IL, lecA, and flanking DNA for sequence analysis and reporter gene construction. Since the immunoblot data indicated that regulation of the genes for PA-IL and PA-IIL was tightly coupled, it was possible that the two genes were contained within an operon. However, analysis of the lecA gene region of PAO1 failed to identify a gene which when translated matched the deduced N-terminal amino acid sequence of PA-IIL (data not shown). Moreover, the lecA transcript size of approximately 500 bp was in good agreement with the predicted size of 480 bp deduced from the proposed transcription start point and the Rho factor-independent terminator and clearly indicates that lecA is monocistronic. The genes coding for the two P. aeruginosa lectins are therefore unlinked despite the tight coupling of lectin production.

The failure of E. coli to express recombinant PA-IL from the original cosmid clones and plasmids pCF1 and pCF2 suggested that additional P. aeruginosa regulators were required. Expression from plasmid pCF3 was most probably driven by the pUCP18 lac promoter, as the ATG start codon of the lecA gene was only 19 bp from the 5′ end of the encoding DNA fragment, indicating that the lecA promoter sequence was lost during subcloning. To gain further insights into the regulation of lecA, the 5′ end of the lecA gene was mapped using both S1 mapping and primer extension. Both techniques indicated that the transcription start site was 70 bp upstream of the ATG codon. Analysis of the region upstream of the mRNA start point revealed two potential RpoS (ςS) −10 elements in positions −18 to −12 and −13 to −7 relative to the transcription start point. This suggested a possible role for RpoS in lectin gene expression. RpoS was originally identified in gram-negative bacteria as an alternative sigma factor responsible for the activation of genes required for survival in the stationary phase, but it is now clear that RpoS is an important regulator of the general stress response (42). In P. aeruginosa, mutation of rpoS leads to enhanced susceptibility of stationary-phase cells to heat, low pH, high osmolarity, hydrogen peroxide, and ethanol, although the increased sensitivity was not as pronounced as that reported previously for E. coli (35, 63). Intriguingly, in a rat chronic lung infection model, the rpoS mutant was more virulent than the parent strain, suggesting that, in P. aeruginosa, RpoS influences virulence gene expression (63). This was suggested to be due to enhanced pyocyanin synthesis, since exotoxin A production was reduced by 50% and exoprotease production was relatively unaffected in the rpoS mutant (63). For P. aeruginosa, Latifi et al. (38) have demonstrated that rpoS expression is itself directly regulated by RhlR/C4-HSL. Thus, the data presented here indicate that, since lecA expression is RpoS dependent, RhlR/C4-HSL controls expression of the PA-IL lectin both directly (as demonstrated by the RhlR/C4-HSL-dependent regulation of the lecA::lux fusion in E. coli) and indirectly (via the RhlR/C4-HSL-dependent expression of rpoS).

For LuxR-type regulators such as LasR and RhlR, lux box-like elements constitute the DNA-binding site. Recently, it has been shown that the lux box-like operator sequences OP1 and OP2, upstream of the lasB structural gene in P. aeruginosa, are important for the initiation of transcription (14, 55, 73). Furthermore, Zhu and Winans (74) established that TraR, a LuxR-type regulator in Agrobacterium tumefaciens, in vitro binds precisely to a lux box-like element (the tra box). The presence of a putative lux box upstream of lecA therefore suggests that it is directly regulated by LasR and/or RhlR. This lux box-like element is centered 42 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site. Very similar distances have been reported for the lux box elements upstream of rhlAB (51), lasB (OP1) (55), and rhlI (K. Winzer and P. Williams, unpublished data), as well as the elements upstream of luxI in V. fischeri (11) and TraR-dependent promoters (16). As a consequence, these operators are extremely close to, or even overlap with, the respective promoter regions. However, although the putative lecA box is similar to the lux box described for V. fischeri, it is not an inverted repeat, which is also true for other lux box-like elements. While OP1 upstream of lasB is an inverted repeat and matches 13 of the 20 bp of the V. fischeri lux box sequence, OP2 is not an inverted repeat but does match 10 of the 20 lux box nucleotides (55). However, deletion of the OP2 sequence negatively affects LasR-mediated expression of lasB, indicating that it is still a target for LasR in the activation of lasB (55).

Heterologous expression of the lecA::lux plasmid reporter in E. coli together with either lasR or rhlR revealed that RhlR, together with its cognate autoinducer C4-HSL, is sufficient for the activation of the lecA gene in an E. coli background. In the absence of C4-HSL, or in the presence of LasR/3O-C12-HSL, only background levels of expression were observed. These data demonstrate that RhlR/C4-HSL, but not LasR/3O-C12-HSL, directly activates the lecA gene, while the data obtained with the P. aeruginosa mutants support the existence of a regulatory hierarchy in which LasR/3O-C12-HSL serves as the master regulator. Furthermore, 3O-C12-HSL has been suggested to be involved in the posttranslational control of RhlR/C4-HSL-dependent genes (52). This is because, in E. coli, an excess of 3O-C12-HSL drastically reduced the binding of radiolabeled C4-HSL to cells expressing RhlR. Pesci et al. (52) also showed that the ability of RhlR/C4-HSL to activate an rhlA′-lacZ fusion in E. coli decreased in a dose-dependent manner with increasing concentrations of 3O-C12-HSL. These data suggest that 3O-C12-HSL is able to block the binding of C4-HSL to RhlR, thereby controlling RhlR activity at a posttranslational level. In the present study, we show that the RhlR/C4-HSL-dependent expression of a lecA::lux fusion in E. coli is inhibited by 3O-C12-HSL. This finding is consistent with the antagonism exerted by long-chain AHLs on quorum-sensing-dependent genes activated by short-chain AHLs. For example, the C6-HSL-mediated activation of the purple pigment violacein in Chromobacterium violaceum is inhibited by AHLs with N-acyl chains of eight carbons or more (40). Similarly, the C4-HSL-dependent production of exoproteases in Aeromonas hydrophila is inhibited by AHL analogues with acyl side chains of 10, 12, or 14 carbons (64). P. aeruginosa is, however, unusual in producing both short (C4-HSL) and long (3O-C12-HSL) AHLs. When exogenous AHLs (either C4-HSL, C6-HSL, or 3O-C12-HSL) were added to the P. aeruginosa lecA::lux reporter, only C4-HSL and C6-HSL enhanced lecA::lux expression. C6-HSL is generated via RhlI as a minor P. aeruginosa AHL together with C4-HSL (69). The results obtained with the P. aeruginosa lecA::lux reporter are consistent with the ability of C6-HSL to activate the rhlI promoter via RhlR in an E. coli genetic background (69). However, when exogenous 3O-C12-HSL was added to the P. aeruginosa lecA::lux reporter, in contrast to the situation with E. coli, no inhibition of lecA expression was observed. This finding suggests that, at least for lecA, 3O-C12-HSL does not act as a posttranslational regulator of PA-IL production. Whether this will also prove to be the case for other RhlR/C4-HSL-dependent genes remains to be established.

The addition of exogenous 3O-C6-HSL at the time of inoculation overcomes the cell-density-dependent induction of bioluminescence in V. fischeri and carbapenem antibiotic production in Erwinia carotovora (43, 68). However, expression of the P. aeruginosa lecA::lux fusion could not be induced immediately or advanced by the addition of either C4-HSL or 3O-C12-HSL or both even at high, nonphysiological concentrations under the growth conditions employed in this study. This finding suggests that, in the homologous genetic background, other regulatory factors in addition to RhlR/C4-HSL are required but are presumably unavailable early in the growth cycle. Such factors presumably include RpoS, which is not expressed until the onset of stationary phase (38). Interestingly, Whiteley et al. (67) have divided a number of quorum-sensing-dependent genes in P. aeruginosa into four classes depending on whether, in a lasI rhlI double mutant, they responded immediately (class I) or after a delay (class II) to 3O-C12-HSL alone or immediately (class III) or after a delay (class IV) to both 3O-C12-HSL and C4-HSL. The elastase gene lasB, for example, was considered to exhibit the characteristics of a class IV quorum-sensing gene (67). On this basis, either lecA may be considered as a class IV gene, or it may belong to a new class since it can still be well expressed in the absence of LasR and 3O-C12-HSL.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant BIO4-CT96-0119 from the European Union (IVth Framework Biotechnology Programme) and by a grant and studentship from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, United Kingdom (to P.W.).

We thank A. Lazdunski (C.N.R.S., Marseille, France) for the P. aeruginosa rpoS mutant and M. Brint (Department of Medicine, University of Tennessee and Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Memphis, Tenn.) for P. aeruginosa strains PDO100 (rhlI negative) and PDO111 (rhlR negative).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam E C, Mitchell B S, Schumacher D U, Grant G, Schumacher U. P. aeruginosa PA-II lectin stops human ciliary beating: therapeutic implications of fucose. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:2102–2104. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.6.9196121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adam E C, Schumacher D U, Schumacher U. Cilia from a cystic fibrosis patient react to ciliotoxic Pseudomonas aeruginosa II lectin in a similar manner to normal control cilia—a case report. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:760–762. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100138551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avichezer D, Katcoff D J, Garber N C, Gilboa-Garber N. Analysis of the amino-acid sequence of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa galactophilic PA-I lectin. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23023–23027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avichezer D, Gilboa-Garber N, Garber N C, Katcoff D J. P. aeruginosa PA-I lectin gene: molecular analysis and expression in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1218:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajolet-Laudinat O, Girod-de Bentzmann S, Tournier J M, Madoulet C, Plotkowski M C, Chippaux C, Puchelle E. Cytotoxicity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa internal lectin PA-I to respiratory epithelial cells in primary culture. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4481–4487. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4481-4487.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brint J M, Ohman D E. Synthesis of multiple exoproducts in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is under the control of RhlR-RhlI, another set of regulators in strain PAO1 with homology to the autoinducer-responsive LuxR-LuxI family. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7155–7163. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7155-7163.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapon-Hervé V, Akrim M, Latifi A, Williams P, Lazdunski A, Bally M. Regulation of the xcp secretion pathway by multiple quorum-sensing modulons in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1169–1178. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4271794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chhabra S R, Stead P, Bainton N J, Salmond G P C, Stewart G S A B, Williams P, Bycroft B W. Autoregulation of carbapenem biosynthesis in Erwinia carotovora by analogues of N-(3-oxohexanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone. J Antibiot. 1992;46:441–447. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devine J H, Shadel G S, Baldwin T O. Identification of the operator of the lux regulon from the Vibrio fischeri strain ATCC 7744. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5688–5692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunny G M, Winans S C. Bacterial life: neither lonely nor boring. In: Dunny G M, Winans S C, editors. Cell-cell signaling in bacteria. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egland K A, Greenberg E P. Quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri: elements of the luxI promoter. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1197–1204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espinosa-Urgel M, Chamizo C, Tormo A. A consensus structure for ςS-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:657–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falconer C. Quorum sensing-dependent regulation of lectin expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ph.D. thesis. Nottingham, United Kingdom: University of Nottingham; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukushima J, Ishiwata T, You Z, Chang B, Kurata M, Kawamoto S, Bycroft B W, Stewart G S A B, Morihara K, Williams P, Okuda K. Dissection of the promoter operator region and evaluation of AHL mediated transcriptional regulation of elastase expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;146:311–318. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(96)30495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuqua C, Winans S C, Greenberg E P. Quorum sensing in bacteria: the LuxR-LuxI family of cell density-responsive transcriptional regulators. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:269–275. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.2.269-275.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuqua C, Winans S C. Conserved cis-acting promoter elements are required for density-dependent transcription of Agrobacterium tumefaciens conjugal transfer genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:435–440. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.435-440.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gambello M J, Iglewski B H. Cloning and characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR gene, a transcriptional activator of elastase expression. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3000–3009. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.3000-3009.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gambello M J, Kaye S, Iglewski B H. LasR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a transcriptional activator of the alkaline protease gene (apr) and an enhancer of exotoxin A expression. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1180–1184. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1180-1184.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garber N C, Guempel V, Guempel N, Gilboa-Garber N, Doyle R J. Specificity of the fucose-binding lectin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;48:331–334. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerischer U, Dürre P. mRNA analysis of the adc gene region of Clostridium acetobutylicum during the shift to solventogenesis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:426–433. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.426-433.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilboa-Garber N. Purification and properties of haemagglutinin from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its reaction with human blood cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;273:165–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilboa-Garber N. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lectins. Methods Enzymol. 1982;83:378–385. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(82)83034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilboa-Garber N. The biological function of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lectins. In: Bog-Hansen T C, Sprengler G A, editors. Lectins: biology, biochemistry, clinical biochemistry. Vol. 3. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter; 1983. pp. 495–500. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilboa-Garber N. Lectins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: properties, biological effects and applications. In: Mirelman D, editor. Microbial lectins and agglutinins—properties and biological activity. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1986. pp. 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilboa-Garber N, Avichezer D, Garber N C. Bacterial lectins: properties, structure, effects, function and applications. In: Gabius H J, Gabius S, editors. Glycosciences: status and perspectives. Weinheim, Germany: Chapman & Hall; 1997. pp. 369–398. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilboa-Garber N, Mizrhari L, Garber N. Mannose binding hemagglutinins in extracts of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can J Biochem. 1977;55:975–981. doi: 10.1139/o77-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilboa-Garber N, Sudakevitz D, Sheffi M, Sela R, Levene C. PA-I and PA-II lectin interactions with the ABO(H) and P blood group glycosphingolipid antigens may contribute to the broad spectrum adherence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to human tissues in secondary infections. Glycoconj J. 1994;11:414–417. doi: 10.1007/BF00731276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray K, Passador M L, Iglewski B H, Greenberg E P. Interchangeability and specificity of components from the quorum-sensing regulatory systems of Vibrio fischeri and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3076–3080. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.3076-3080.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardman A M, Stewart G S A B, Williams P. Quorum sensing and the cell-cell communication dependent regulation of gene expression in pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1998;74:199–210. doi: 10.1023/a:1001178702503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hassett D J, Ma J-F, Elkins J G, McDermott T R, Ochsner U A, West S E H, Huang C-T, Fredericks J, Burnett S, Stewart P S, McFeters G, Passador L, Iglewski B H. Quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa controls expression of catalase and superoxide genes and mediates biofilm susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:1082–1093. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herrero M, De Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirakata Y, Furuya N, Tateda K, Matsumoto T, Yamaguchi K. The influence of exo-enzyme S and proteases on endogenous Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteraemia in mice. J Med Microbiol. 1995;43:258–261. doi: 10.1099/00222615-43-4-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones S, Yu B, Bainton N J, Birdsall M, Bycroft B W, Chhabra S R, Cox A J R, Golby P, Reeves P J, Stephens S, Winson M K, Salmond G P C, Stewart G A S B, Williams P. The lux autoinducer regulates the production of exoenzyme virulence determinants in Erwinia carotovora and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. EMBO. 1993;12:2477–2482. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jørgensen F, Bally M, Chapon-Herve V, Michel G, Lazdunski A, Williams P, Stewart G S A B. RpoS-dependent stress tolerance in stationary phase Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology. 1999;145:835–844. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-4-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaniga K, Delor I, Cornelis G R. A wide host range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in gram negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene. 1991;109:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Latifi A, Winson M K, Foglino M, Bycroft B W, Stewart G S A B, Lazdunski A, Williams P. Multiple homologues of LuxR and LuxI control expression of virulence determinants and secondary metabolites through quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:333–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Latifi A, Foglino M, Tanaka K, Williams P, Lazdunski A. A hierarchical quorum sensing cascade in Pseudomonas aeruginosa links the transcriptional activators LasR and RhlR (VsmR) to expression of the stationary phase sigma factor RpoS. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1137–1146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowe T M, Eddy S R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McClean K H, Winson M K, Fish L, Taylor A, Chhabra S R, Camara M, Daykin M, Swift S, Bycroft B W, Stewart G S A B, Williams P. Quorum sensing and Chromobacterium violaceum: exploitation of violacein production and inhibition for the detection of N-acylhomoserine lactones. Microbiology. 1997;143:3703–3711. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merrick M J. In a class of its own—the RNA polymerase sigma factor sigma-54 (sigma-N) Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:903–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muffler A M, Barth M, Marschall C, Hengge-Aronis R. Heat shock regulation of ςS turnover: a role of DnaK and relationship between stress responses mediated by ςS and ς32 in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:445–452. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.445-452.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nealson K H, Platt T, Hastings J W. Cellular control of the synthesis and activity of the bacterial luminescent system. J Bacteriol. 1970;104:313–322. doi: 10.1128/jb.104.1.313-322.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicas T I, Iglewski B H. The contribution of exoproducts to the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can J Microbiol. 1985;31:387–392. doi: 10.1139/m85-074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norqvist A, Wolf-Watz H. Characterization of a novel chromosomal virulence locus involved in expression of a major surface flagellar sheath antigen of the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2434–2444. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2434-2444.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ochsner U A, Kock K A, Fiechter A, Reiser J. Isolation and characterization of a regulatory gene affecting rhamnolipid biosurfactant synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2044–2054. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.2044-2054.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ochsner U A, Reiser J. Autoinducer-mediated regulation of rhamnolipid biosurfactant synthesis in P. aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6424–6428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oelmüller U N, Krüger A, Steinbüchel A, Friedrich C. Isolation of prokaryotic RNA and detection of specific mRNA with biotinylated probes. J Microbiol Methods. 1990;11:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pal R, Ahmed H, Chatterjee B P. Pseudomonas aeruginosa HABS type 2a contains two lectins of different specificity. Biochem Arch. 1987;3:399–412. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Passador L, Cook J M, Gambello M J, Rust L, Iglewski B H. Expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes requires cell-to-cell communication. Science. 1993;260:1127–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.8493556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pearson J P, Pesci E C, Iglewski B H. Roles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa las and rhl quorum-sensing systems in control of elastase and rhamnolipid biosynthesis genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5756–5767. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5756-5767.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pesci E C, Pearson J P, Seed P C, Iglewski B H. Regulation of las and rhl quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3127–3132. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3127-3132.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Preston M J, Fleiszig S M J, Zaidi T S, Goldberg J B, Shortridge V D, Vasil M L, Pier G B. Rapid and sensitive method for evaluating Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factors during corneal infections in mice. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3497–3501. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3497-3501.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ronald S, Farinha M A, Allan B J, Kropinski A M. Cloning and physical mapping of transcriptional regulatory (sigma) factors from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In: Galli E, Silver S, Witholt B, editors. Pseudomonas: molecular biology and biotechnology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 249–257. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rust L, Pesci E C, Iglewski B H. Analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase (lasB) regulatory region. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1134–1140. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1134-1140.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saiman L, Cacalano G, Gruenert D, Prince A. Comparison of adherence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to respiratory epithelial cells from cystic fibrosis patients and healthy subjects. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2808–2814. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2808-2814.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salmond G P C, Bycroft B W, Stewart G S A B, Williams P. The bacterial engima—cracking the code of cell-cell communication. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:615–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Savioz A, Zimmermann A, Haas D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa promoters which contain a conserved GG-N10-GC motif but appear to be RpoN-independent. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;238:74–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00279533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schweizer H P. Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19. Gene. 1991;97:109–121. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simon R, Quandt J, Klipp W. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith A W, Iglewski B H. Transformation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:105–109. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.24.10509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Suh S-J, Silo-Suh L, Woods D E, Hassett D J, West S E H, Ohman D E. Effect of rpoS mutation on the stress response and expression of virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3890–3897. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.3890-3897.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Swift S, Lynch M J, Fish L, Kirke D F, Tomas J, Stewart G S A B, Williams P. Quorum-sensing-dependent regulation and blockade of exoprotease production in Aeromonas hydrophila. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5192–5199. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5192-5199.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toder D S, Gambello M J, Iglewski B H. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasA—a second elastase under the transcriptional control of LasR. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2003–2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wentworth J S, Austin F E, Garber N C, Gilboa-Garber N, Paterson C A, Doyle R J. Cytoplasmic lectins contribute to the adhesion of P. aeruginosa. Biofouling. 1991;4:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Whiteley M, Lee K M, Greenberg E P. Identification of genes controlled by quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13904–13909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Williams P, Bainton N J, Swift S, Chhabra S R, Winson M K, Stewart G S A B, Salmond G P C, Bycroft B W. Small molecule-mediated density-dependent control of gene expression in prokaryotes: bioluminescence and the biosynthesis of carbapenem antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;100:161–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb14035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Winson M K, Camara M, Latifi A, Foglino M, Chhabra S R, Daykin M, Bally M, Chapon V, Salmond G P C, Bycroft B W, Lazdunski A, Stewart G S A B, Williams P. Multiple N-acyl-l-homoserine lactone signal molecules regulate production of virulence determinants and secondary metabolites in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9427–9431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Winson M K, Swift S, Hill P J, Sims C M, Griesmayr G, Bycroft B W, Williams P, Stewart G S A B. Engineering the luxCDABE genes from Photorhabdus luminescens to provide a bioluminescent reporter for constitutive and promoter probe plasmids and mini-Tn5 constructs. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;163:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Winzer K, Lorenz K, Dürre P. Acetate kinase from Clostridium acetobutylicum: a highly specific enzyme that is actively transcribed during acidogenesis and solventogenesis. Microbiology. 1997;143:3279–3286. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-10-3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.You Z, Fukushima J, Ishiwata T, Chang B, Kurata M, Kawamoto S, Williams P, Okuda K. Purification and characterization of LasR as a DNA-binding protein. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;142:301–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhu J, Winans S C. Autoinducer binding by the quorum-sensing regulator TraR increases affinity for target promoters in vitro and decreases TraR turnover rates in whole cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4832–4837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]