Abstract

The predominant photolesion in the DNA of UV-irradiated dormant bacterial spores is the thymine dimer 5-thyminyl-5,6-dihydrothymine, commonly referred to as spore photoproduct (SP). A major determinant of SP repair during spore germination is its direct reversal by the enzyme SP lyase, encoded by the splB gene in Bacillus subtilis. SplB protein containing an N-terminal tag of six histidine residues [(6His)SplB] was purified from dormant B. subtilis spores and shown to efficiently cleave SP but not cyclobutane cis,syn thymine-thymine dimers in vitro. In contrast, SplB protein containing an N-terminal 10-histidine tag [(10His)SplB] purified from an Escherichia coli overexpression system was incompetent to cleave SP unless the 10-His tag was first removed by proteolysis at an engineered factor Xa site. To assay the parameters of binding of SplB protein to UV-damaged DNA, a 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide was constructed which carried a single pair of adjacent thymines on one strand. Irradiation of the oligonucleotide in aqueous solution or at 10% relative humidity resulted in formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (Py◊Py) or SP, respectively. (10His)SplB was assayed for oligonucleotide binding using a DNase I protection assay. In the presence of (10His)SplB, the SP-containing oligonucleotide was selectively protected from DNase I digestion (half-life, >60 min), while the Py◊Py-containing oligonucleotide and the unirradiated oligonucleotide were rapidly digested by DNase I (half-lives, 6 and 9 min, respectively). DNase I footprinting of (10His)SplB bound to the artificial substrate was carried out utilizing the 32P end-labeled 35-bp oligonucleotide containing SP. DNase I footprinting showed that SplB protected at least a 9-bp region surrounding SP from digestion with DNase I with the exception of two DNase I-hypersensitive sites within the protected region. (10His)SplB also caused significant enhancement of DNase I digestion of the SP-containing oligonucleotide for at least a full helical turn 3′ to the protected region. The data suggest that binding of SP lyase to SP causes significant bending or distortion of the DNA helix in the vicinity of the lesion.

Endospores of Bacillus subtilis, as well as other Bacillus and Clostridium spp., are significantly more resistant to 254-nm-wavelength UV radiation than are their exponentially growing counterparts. Spore UV resistance is due to the unique UV photochemistry of spore DNA and the efficient repair of spore DNA damage during germination (reviewed in references 14, 15, and 23). In the spore or in vitro, binding of spore DNA by small, acid-soluble spore proteins (SASP) of the α/β class results in an alteration of the helical conformation of dormant-spore DNA from the B form to an A-like form (10). UV irradiation of either spores (1, 22) or SASP-DNA complexes in vitro (16) favors production in DNA of the unique spore photoproduct (SP) 5-thyminyl-5,6-dihydrothymine and suppression of cyclobutyl pyrimidine dimer (Py◊Py) formation (references 1 and 16; reviewed in references 23 and 24).

An important determinant of SP repair during spore germination is its direct reversal to two thymines in DNA by the enzyme SP lyase (11, 12), encoded by the splB gene in B. subtilis (2). SplB was first characterized as a 40-kDa protein with limited similarity to members of the DNA photolyase/(6-4) photolyase/blue-light receptor protein family (2, 14, 27) but did not appear to be a true photolyase, as repair of SP by SP lyase during spore germination proceeds in the absence of photoreactivating light (11, 12). The first clue to the enzymatic mechanism of SP lyase came from examination of the deduced amino acid sequence of the B. subtilis SplB protein. The 342-amino-acid sequence of SplB was observed to contain only four cysteines, three of which were tightly clustered at residues 91, 95, and 98 (2). The SplB sequence surrounding residues C91, C95, and C98 was found through sequence database searching to be highly similar to the amino acid signature for the [4Fe-4S] clusters of a family of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-dependent, radical-utilizing enzymes represented by anaerobic (type III) ribonucleotide reductase, pyruvate-formate lyase, lysine-2,3-aminomutase, biotin synthase (BioB), and lipoic acid synthetase (LipA) (13, 15, 20).

SP lyase activity was purified from B. subtilis spores expressing an engineered splB gene encoding a tag of six histidine residues at its amino terminus [(6His)SplB] (20). (6His)SplB was able to cleave SP in vitro, and its activity was dependent upon reducing conditions and SAM, but the protein was present in spores in exceedingly small quantities (20). Another version of SplB containing a more complex N-terminal tag consisting of 10 histidines and a factor Xa cleavage site, called here (10His)SplB, was engineered, overproduced, and purified in large amounts from Escherichia coli (20). The purified (10His)SplB protein was shown to contain an intact FeS cluster but was incapable of cleaving SP in vitro (20); furthermore, until recently the 10-His tag was refractory to proteolytic cleavage with factor Xa. In this communication, we report that successful cleavage of (10His)SplB by factor Xa restores the enzyme to an active conformation; thus, active SP lyase consists of only SplB protein. Furthermore, SP binding and SP cleavage activities can be separated by the presence of the 10-His tag on SplB.

In order to better understand at the molecular level how SP lyase binds to SP, we report here the construction of a synthetic 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide which contains a single pair of adjacent thymines which can be manipulated to form either T◊T or SP. We report that (10His)SplB protein purified from an E. coli overexpression system (i) binds specifically to the oligonucleotide containing SP, (ii) protects SP from digestion with DNase I, and (iii) dramatically alters the DNase I footprint of the SP-containing oligonucleotide.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sources of SplB protein and SP lyase assay.

(6His)SplB was purified from dormant spores of B. subtilis strain WN417 (metC14 sul Δ(splAB)::ermC splA-(6his)splB::amyE Cmr thyA1 thyB1 trpC2) as described in detail previously (20). Due to the exceedingly small quantity of the protein present in dormant spores, purification of (6His)SplB was monitored by Western blot analysis as described in detail previously (20). The N-terminal amino acid sequence of (6His)SplB was determined to be MHHHHHHQNPFV by nucleotide sequencing of the cloned engineered splB gene (the italicized residues denote the natural SplB sequence [2]).

(10His)SplB was overexpressed and purified from E. coli strain AD494[DE3] carrying plasmid pCLK201 essentially as described previously (20), with the modifications described below in the case of its preparation for factor Xa cleavage. The purified protein was judged to be >99% pure on Coomassie blue-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels (data not shown). The N-terminal sequence of (10His)SplB was determined by Edman degradation to be MGHHHHHHHHHHSSGHIEGR/HMQNPFV (the underlined residues and shill indicate the factor Xa cleavage site; the italicized residues denote the natural SplB sequence [2]).

The purified enzymes were subjected to activation of their FeS clusters and were assayed for SP cleavage essentially as described previously (20), except that moist argon gas replaced the hydrogen-CO2 mixture used previously and the assays were performed in sealed septum vials.

Factor Xa cleavage of (10His)SplB.

When exposed to oxygen at high protein concentrations, SplB rapidly aggregates and precipitates from solution. Therefore, in order to successfully cleave (10His)SplB with factor Xa, all procedures were performed under anaerobic conditions. (10His)SplB was purified by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid chromatography from a cell extract of E. coli strain AD494[DE3] which had been IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induced. The high-concentration imidazole eluate of (10His)SplB was collected and incubated under moist argon with factor Xa at room temperature for 4 h. Under these conditions, the 10-His tag was removed from approximately 20% of the SplB molecules, as judged by SDS-PAGE (data not shown). The resulting protein was activated and assayed for SP lyase activity as described above and previously (20).

Sources of DNA for assay.

B. subtilis chromosomal DNA was labeled by growth and sporulation of strain WN175 (metC14 splB1 sul thyA1 thyB1 trpC2 uvrB42) in the presence of 5-methyl [3H]thymidine. Chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis strain WN175 containing either SP or Py◊Py was prepared from UV-irradiated spores or vegetative cells, respectively, as described previously (26). The DNA concentration was determined by fluorescence assay using PicoGreen reagent (Molecular Probes). Quantitation of SP or Py◊Py in UV-treated DNA was performed as described below.

Construction and labeling of the 35-bp oligonucleotide.

Two complementary 35-mer oligonucleotides were synthesized (Genosys, Inc.), one of which contained a single pair of adjacent thymines (denoted in boldface type): 5′-CCCGGGGATCCTCTAGAGTTGACCTGCAGGCATGC-3′ and 5′-GCATGCCTGCAGGTCAACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGG-3′. The oligonucleotides were resuspended in sterile distilled water, quantitated by their A260 values (21), and hybridized by mixing them in equimolar proportions, heating them to 90°C, and cooling them slowly to room temperature in a water bath. Thymine residues in the 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide were radiolabeled in a PCR amplification reaction using the PCR primers 5′-CCCGGGGATCCTCT-3′ and 5′-GCATGCCTGCAGG-3′, thermostable DNA polymerase (Deep Vent; New England Biolabs), and unlabeled dATP, dCTP, dGTP, TTP, and 5-methyl [3H]TTP (Amersham). The PCR products were quantitated by scintillation counting and by fluorescence assay for DNA (PicoGreen; Molecular Probes) in a Turner Model 430 spectrofluorometer.

UV irradiation conditions.

All UV treatments were performed using a short-wave UV lamp (Model UVS-11; UV Products) which emits mainly monochromatic 254-nm-wavelength UV light. The lamp output was determined using a UVX radiometer (UV Products). All oligonucleotide samples were irradiated to a final dose of 16 kJ/m2. The double-stranded 35-bp oligonucleotide was irradiated in water to produce cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (Py◊Py). To produce SP, the double-stranded oligonucleotide was first air dried from water onto a single layer of Saran Wrap, which transmits approximately 80% of incident 254-nm-wavelength radiation (29). The sample was inverted over a saturated solution of ZnCl2, sealed, allowed to equilibrate to 10% relative humidity (RH) over a period of 4 to 7 days (19), irradiated through the Saran Wrap, and resuspended from the dried state into water.

Identification of DNA photoproducts.

Photoproducts were identified essentially as follows (26). UV-irradiated 3H-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides (105 cpm) were dried in a Speedvac, resuspended in 0.5 ml of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (>99.5% pure high-performance liquid chromatography grade; Pierce), and transferred to glass ampoules which were flame sealed under vacuum. TFA hydrolysis was carried out at 175°C for 60 min, the TFA was removed from the opened vials by evaporation, and the hydrolysates were resuspended in water and subjected to descending chromatography on Whatman no. 1 paper using n-butanol–acetic acid–water (80:12:30) as the solvent. The chromatogram was air dried and cut into 1-cm fractions; each fraction was eluted into water and counted in aqueous scintillation cocktail, and the photoproducts were identified by their Rf values (1, 26).

DNase I protection experiments.

Unlabeled 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide containing either no photoproduct, Py◊Py, or SP (2.8 μg) was mixed with freshly prepared purified (10His)SplB protein (5 μg) in a total volume of 20 μl of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM MgCl2, and 20 mM dithiothreitol, resulting in a 1:1 molar ratio of protein to DNA. After preincubation at 37°C for 15 min, DNase I (1 U) (Promega, Madison, Wis.) was added to the mixture and incubation was continued at 37°C. At 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 60 min after DNase I addition, the reactions were stopped by addition of Na2EDTA to a final concentration of 25 mM. Samples were electrophoresed through nondenaturing 12% PAGE, stained with ethidium bromide, destained with 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA electrophoresis buffer, and visualized by UV transillumination (21). Negative digital images of the gels were scanned, and band intensities were quantitated using NIH Image software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.).

DNase I footprinting experiments.

The 35-base single-stranded oligonucleotide containing two adjacent thymines was 5′-end-labeled with 125 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega). The labeled strand was then hybridized to its complementary strand, air dried, and equilibrated for 2 to 4 days in the presence of saturated ZnCl2 as described above. The labeled oligonucleotide was irradiated at 10% RH with 254-nm-wavelength UV to produce SP and purified after electrophoresis through a 12% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel (21). The footprinting reaction mixtures (20-μl total volume) contained 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM MgCl2, 20 mM dithiothreitol, and 280 ng of 32P end-labeled 35-bp SP-containing double-stranded oligonucleotide. Freshly-prepared (10His)SplB (0.5, 2.5, and 5 μg of protein) was added and prebound to the oligonucleotide at 37°C for 15 min, and then DNase I (0.5 U) was added and the reaction mixtures were incubated again at 37°C for 15 min. DNase I digestion was stopped by adding Na2EDTA to a final concentration of 25 mM. The DNase I digestion products were precipitated by the addition of 1 μl of glycogen (20 mg/ml), 25 μl of 4 M lithium chloride, and 0.5 ml of 95% ethanol and incubation at −70°C for 1 h. The DNA precipitate was harvested by centrifugation (12,000 × g; 30 min; 4°C), air dried, and resuspended in 5 μl of DNA sequencing buffer (U.S. Biochemical, Cleveland, Ohio). The DNA was electrophoresed through 12% polyacrylamide sequencing gels in parallel to the G- and C>T-specific chemical sequencing reactions (7a) performed in parallel on the oligonucleotide. The electrophoresis products were visualized by autoradiography and scanned, and band intensities were quantitated using NIH Image software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Activation of SP lyase activity in (10His)SplB by proteolytic removal of its 10-His tag.

(6His)SplB protein purified from spores of B. subtilis strain WN417 efficiently monomerized SP in UV-irradiated spore DNA in a concentration-dependent manner (20) (Fig. 1). In contrast, (10His)SplB purified from the E. coli overexpression system was inactive in cleavage of SP (Fig. 1), and it was further noted that the 10-His tag was refractory to proteolytic removal from SplB. However, by performing factor Xa cleavage of (10His)SplB under anaerobic conditions, we were able to remove the 10-His tag from approximately 20% of the SplB molecules purified from the E. coli overexpression system. The resulting factor Xa-treated SplB preparation was then assayed for SP lyase activity and was shown to cleave SP, also in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1). The results clearly indicated that the presence of the 10-His tag was preventing (10His)SplB from expressing SP lyase activity. Because (10His)SplB was the only B. subtilis protein overexpressed and purified from the E. coli system, the results also clearly indicated that SP lyase activity derived solely from the splB gene product after removal of its 10-His tag.

FIG. 1.

Assay of SP cleavage activity on SP-containing B. subtilis chromosomal DNA from UV-irradiated spores. The proteins assayed were (6His)SplB purified from spores of B. subtilis strain WN417 (triangles), (10His)SplB overproduced in and isolated from E. coli (open circles), and (10His)SplB purified from E. coli and cleaved with factor Xa (solid circles). The data are averages ± standard deviation of duplicate determinations.

SP lyase discriminates between SP and Py◊Py.

In order to test whether SP lyase specifically recognizes and cleaves SP, (10His)SplB protein isolated from the E. coli overexpression system and cleaved with factor Xa was incubated with a substrate consisting of B. subtilis chromosomal DNA which contained a mixture of cis,syn T◊T, cis,syn C◊T, and SP. Quantitation of chromatograms of the TFA hydrolysates resulting from the reactions showed clearly that proteolytically treated (10His)SplB protein cleaved only SP and not cis,syn T◊T or cis,syn C◊T (Table 1), indicating that SP lyase exhibited specificity for SP in vitro. This notion was confirmed in a time course experiment, where (6His)SplB isolated from dormant spores of B. subtilis strain WN417 was shown to cleave SP, but not cis,syn T◊T, in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2).

TABLE 1.

Specificity of SP lyase for SP in vitroa

| Photoproduct | SplB added (μg) | Amt of photoproductb | % Repair |

|---|---|---|---|

| SP | 0 | 3.58 ± 0.13 | |

| SP | 0.63 | 3.13 ± 0.13 | 12.5c |

| cis,syn T◊T | 0 | 3.81 ± 0.28 | |

| cis,syn T◊T | 0.63 | 4.10 ± 0.21 | NSd |

| cis,syn C◊T | 0 | 0.59 ± 0.06 | |

| cis,syn C◊T | 0.63 | 0.60 ± 0.00 | NS |

Factor Xa-cleaved (10His)SplB protein purified from the E. coli overexpression system (3.12 μg of total protein containing 0.63 μg [20%] of active SplB) was incubated with 4.1 μg of B. subtilis chromosomal DNA containing a mixture of SP, cis,syn T◊T, and cis,syn C◊T for 60 min at 30°C. The results are averages of duplicate determinations.

Expressed as percentage of total thymine ± standard deviation.

Significant decrease in SP by ANOVA (P = 0.07).

NS, not significantly different from control by ANOVA.

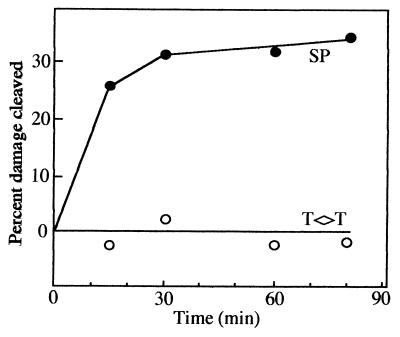

FIG. 2.

Kinetics of reversal of SP (solid circles) or cis,syn T◊T (open circles) by (6His)SplB protein (2 μg) purified from spores of B. subtilis strain WN417. The initial amounts of photoproducts in each reaction mixture were 2.68% SP and 2.72% T◊T (expressed as a percentage of total thymine).

UV photochemistry of the 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide.

In order to study the interaction of SplB protein with SP in DNA, a synthetic 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide was designed and constructed as described in Materials and Methods. Thymine residues in the 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide were labeled with 3H at their 5-methyl positions by PCR amplification, and the UV photochemistry of the synthetic 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide was probed by assaying thymine-containing photoproducts produced after UV irradiation either in aqueous solution or at 10% RH. Quantitation of the TFA hydrolysis products after their separation by chromatography revealed that the unirradiated 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide contained no photoproducts while the 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide irradiated in aqueous solution accumulated Py◊Py in the form of cis,syn T◊T, trans,syn T◊T, and U◊T (the TFA hydrolysis breakdown product of C◊T) (1, 16) at 0.6, 0.55, and 0.3% of total thymine, respectively. In sharp contrast, UV irradiation of the 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide at 10% RH resulted in formation of SP to approximately 5.0% of total thymine. To confirm that the SP-containing oligonucleotide did not contain Py◊Py, it was 5′ end labeled with [32P]ATP and polynucleotide kinase and treated with T4 endonuclease V (Epicentre, Madison, Wis.), which cleaves the phosphodiester backbone 5′ to cyclobutane dimers (2a), and the reaction products were analyzed by autoradiography after electrophoresis through a 12% sequencing gel. No phosphodiester backbone cleavage of the oligonucleotide by T4 endonuclease V was detected (data not shown), indicating that (i) no significant quantities of Py◊Py were formed concomitant with SP by UV irradiation of the 35-bp oligonucleotide at 10% RH and (ii) T4 endonuclease V either does not recognize SP or its AP endonuclease activity does not function on SP.

(10His)SplB specifically protects SP-containing DNA from DNase I.

Previous attempts to detect (10His)SplB binding to SP-containing DNA by gel retardation analysis were unsuccessful (data not shown). Therefore, in order to assay (10His)SplB protein for DNA binding activity, a DNase I protection assay was devised. Unlabeled 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotides carrying no damage, Py◊Py, or SP were prepared as described above and used to test (10His)SplB binding affinity. Purified (10His)SplB protein was incubated with double-stranded oligonucleotide at a 1:1 molar ratio, and then the mixture was probed for protein-DNA complex formation by protection from DNase I digestion as described in Materials and Methods. When the double-stranded oligonucleotides remaining after DNase I treatment were visualized by nondenaturing 12% PAGE, it was observed that the double-stranded oligonucleotides containing no photoproducts (Fig. 3A) or Py◊Py (Fig. 3B) were rapidly degraded by DNase I but the SP-containing double-stranded oligonucleotide was protected from DNase I degradation (Fig. 3C). Quantitation of the remaining 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotides by scanning densitometry of negative digital images obtained from three separate experiments allowed us to determine the half-life for each double-stranded oligonucleotide in the presence of (10His)SplB and DNase I. The 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotides containing no photoproducts or containing Py◊Py were degraded rapidly, exhibiting half-lives of 6.1 ± 1.15 and 9.6 ± 4.25 min, respectively, while the SP-containing double-stranded oligonucleotide was degraded much more slowly, demonstrating a half-life of 58.2 ± 19.8 min. The differences in the half-lives of all of the double-stranded oligonucleotides were a direct consequence of their interactions with (10His)SplB and were not due to intrinsic differences in their DNase I susceptibilities, because in control reactions performed in the absence of added (10His)SplB protein, the double-stranded oligonucleotides containing no damage, Py◊Py, or SP were all degraded rapidly, exhibiting half-lives of 6.2 ± 2.56, 8.5 ± 0.90, and 6.2 ± 1.15 min, respectively (Fig. 3). By analysis of variance (ANOVA), the half-lives of the double-stranded oligonucleotides containing either no damage or Py◊Py were not significantly increased in the presence of (10His)SplB, but the increased half-life of the SP-containing double-stranded oligonucleotide bound to (10His)SplB was highly significant by ANOVA (P = 0.010). Therefore, despite the fact that (10His)SplB was inactive in cleaving SP (Fig. 1), the protein bound tightly and specifically to SP-containing DNA (Fig. 3).

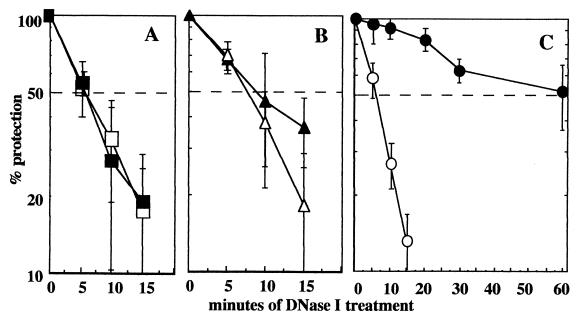

FIG. 3.

DNase I protection experiment. The 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide carrying: no dimer (A), Py◊Py (B), or SP (C) was preincubated either with (solid symbols) or without (open symbols) (10His)SplB and then treated with DNase I and quantitated as described in Materials and Methods. The data are represented as averages ± standard deviations of three independent experiments. The horizontal dashed line represents 50% degradation.

Binding of (10His)SplB to the SP-containing oligonucleotide dramatically alters its DNase I footprint.

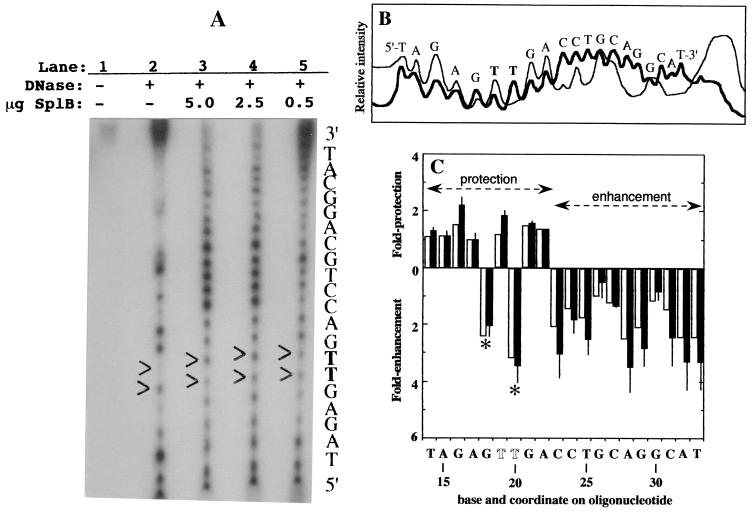

In order to explore SplB binding to SP-containing DNA at a higher level of resolution, the SP-containing 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide was 5′-end-labeled with 32P on the SP-containing strand and complexed with (10His)SplB, the complexes were subjected to limited DNase I digestion, and the resulting DNase I footprints were analyzed. A typical autoradiogram (Fig. 4A) showed that addition of (10His)SplB dramatically altered the DNase I cleavage pattern of the SP-containing oligonucleotide and that the alteration occurred in a manner dependent upon the amount of (10His)SplB added. To quantitate the effect of (10His)SplB binding on the DNase I footprint, a digital image of the autoradiogram was subjected to densitometry (Fig. 4B), and the intensity of each band was quantitated using the program NIH Image (Fig. 4C). Analysis of the data indicated that (10His)SplB protected a region of at least 9 nucleotides (nt) extending from T14 to A22 on the SP-containing strand of the oligonucleotide from DNase I digestion (it was not possible to assess protection of DNA 5′ to this point due to limitations in the resolution of the sequencing gel). In sharp contrast, DNase I digestion was dramatically enhanced on the 3′ side of the protected region for at least a full helical turn from C23 to T33 (Fig. 4C), indicating that binding of (10His)SplB to the oligonucleotide induced bending, unwinding, or distortion in DNA adjacent to the (10His)SplB binding site, reminiscent of that observed in the DNase I footprints of E. coli DNA photolyase on double- and single-stranded DNA containing T◊T (5) and in the nontranscribed strand of DNA entering vaccinia virus RNA polymerase (4). Interestingly, within the 9-nt protected region extending from T14 to A22, binding of (10His)SplB led to an enhancement of DNase I cleavage at two positions: G19 immediately 5′ to SP and T20, the 3′ T within SP itself. DNase I-hypersensitive sites have been detected within the DNase I-protected regions in a number of systems and are generally also attributed to bending or distortion in the DNA helix as a result of protein binding (3–6, 17, 30). Thus, it appears that binding of SP in DNA by (10His)SplB leads to significant distortion of the phosphodiester backbone, as manifested by alterations in the DNase I cleavage pattern on the damage-containing strand and the appearance of DNase I-hypersensitive sites within the protected region.

FIG. 4.

DNase I footprinting experiment. (A) Autoradiogram. Lane 1, untreated SP-containing 35-nt oligonucleotide; lanes 2 to 5, SP-containing oligonucleotide after partial DNase I digestion in the absence (lane 2) or the presence of 5.0 (lane 3), 2.5 (lane 4), or 0.5 μg (lane 5) of (10His)SplB. The molar ratios of (10His)SplB to oligonucleotide were 10:1 (lane 3), 5:1 (lane 4) and 1:1 (lane 5). The two thymines corresponding to the position of SP are shown in boldface and indicated on the autoradiogram by arrowheads. (B) Densitometric scan of lane 2 (thin line) and lane 3 (thick line) of the autoradiogram displayed in panel A. (C) Quantitative summary of DNase I footprinting experiments. The protection (upward bars) or enhancement (downward bars) of DNase I digestion at each base on the SP-containing oligonucleotide by binding of 2.5 (open bars) and 5.0 μg (solid bars) of (10His)SplB was determined relative to the unbound oligonucleotide. The positions of the two DNase I-hypersensitive sites within the footprint are denoted by asterisks. The position of SP is denoted by the two open T residues at coordinates 19 and 20. The data using 5.0 μg of (10His)SplB are the averages of two independent determinations; the error bars denote the maximum value obtained.

Because enzymes causing direct reversal of pyrimidine dimers, such as SP lyase, probably recognize their cognate DNA damage in every sequence context (5), it was not expected that SP lyase would make specific hydrogen bonds within either the major or minor groove within the DNase I-protected region. To explore this point further, dimethyl sulfate (DMS) footprinting was performed on complexes of (10His)SplB and the SP-containing oligonucleotide in parallel with the DMS reactions, giving rise to the “G ladder” used for identification of base positions within the oligonucleotide. Binding of (10His)SplB to the end-labeled SP-containing oligonucleotide resulted in no significant alteration in its DMS digestion pattern (data not shown).

In summary, the in situ reversal of SP by the novel DNA repair enzyme SP lyase during germination of UV-irradiated B. subtilis spores is a major determinant of spore UV resistance (14, 15), and an essential first step in SP repair is accurate recognition of and binding to the adduct. In this communication, we showed that (10His)SplB protein purified from an E. coli overexpression system bound to a 35-bp double-stranded DNA oligonucleotide containing a single SP but was unable to complete catalysis unless its N-terminal 10-His tag was first proteolytically removed at the engineered factor Xa site (Fig. 1). Thus, the SP-specific binding and cleavage functions of SP lyase are separable. Factor Xa-cleaved (10His)SplB was able to complete catalysis and specifically cleaved SP but not cis,syn T◊T. DNase I protection experiments revealed that the lack of SP lyase activity of (10His)SplB on cyclobutane dimers is most likely due to the fact the (10His)SplB does not bind to Py◊Py-containing DNA with high affinity (Fig. 3).

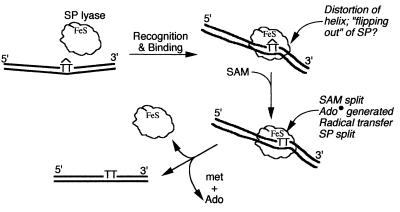

From this communication and previous data (13, 20), the following working model for SP lyase is proposed (Fig. 5). SP lyase specifically recognizes SP in DNA. Recognition is probably sequence context independent, as binding of (10His)SplB did not alter the DMS cleavage pattern of the SP-containing 35-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide. Although the three-dimensional structure of DNA containing SP has not yet been elucidated, it is known that cis,syn T◊T distorts DNA (8, 18), producing a helical kink of 27° and unwinding of 19.7° (18). Because SP lyase binds SP but not Py◊Py with high affinity, it presumably recognizes an SP-specific helical distortion in DNA which differs in its geometry from the distortion caused by cis,syn T◊T. Binding of SP lyase to SP apparently introduces additional distortion in the helix, as manifested by the appearance of DNase I-hypersensitive sites both within and 3′ to the protected region. Enhancement in distortion of Py◊Py-containing DNA by binding of DNA repair proteins has also been observed in the Uvr(A)BC excinuclease (25), DNA photolyase (5), and phage T4 endonuclease V (7). Once SP-specific binding occurs, the [4Fe-4S] cluster of SP lyase (13, 20) interacts with SAM, presumably resulting in the creation of a 5′-adenosyl radical (28) which participates in reversal of SP to two thymines, likely by radical fragmentation (9).

FIG. 5.

Proposed sequence of events in SP cleavage by SP lyase. Abbreviations: Ado, adenosine; FeS, iron-sulfur cluster; met, methionine. See the text for details.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

T.A.S. and R.R. contributed equally to this work.

We thank Cynthia Kinsland and Tadhg Begley for generous donation of the E. coli strain used and Mario Pedraza-Reyes for excellent technical assistance during the early part of this project.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM47461) and the Arizona Agricultural Experimental Station (USDA-Hatch) to W.L.N.

REFERENCES

- 1.Donnellan J E, Jr, Setlow R B. Thymine photoproducts but not thymine dimers are found in ultraviolet irradiated bacterial spores. Science. 1965;149:308–310. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3681.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fajardo-Cavazos P, Salazar C, Nicholson W L. Molecular cloning and characterization of the Bacillus subtilis spore photoproduct lyase (spl) gene, which is involved in repair of UV-induced DNA damage during spore germination. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1735–1744. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1735-1744.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Friedberg E C, Walker G C, Siede W. DNA repair and mutagenesis. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gross D S, English K E, Collins K W, Lee S. Genomic footprinting of the yeast HSP82 promoter reveals marked distortion of the DNA helix and constitutive occupancy of heat shock and TATA elements. J Mol Biol. 1990;216:611–632. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagler J, Shuman S. Structural analysis of ternary complexes of vaccinia RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10099–10103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Husain I, Sancar G B, Holbrook S R, Sancar A. Mechanism of damage recognition by Escherichia coli DNA photolyase. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:13188–13197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krummel B, Chamberlin M J. RNA chain initiation by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: structural transitions of the enzyme in early ternary complexes. Biochemistry. 1989;28:7829–7842. doi: 10.1021/bi00445a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee B-J, Sakashita H, Ohkubo T, Ikehara M, Doi T, Morikawa K, Kyogoku Y, Osafune T, Iwae S, Ohtsuka E. Nuclear magnetic resonance study of the interaction of T4 endonuclease V with DNA. Biochemistry. 1994;33:57–64. doi: 10.1021/bi00167a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Maxam A M, Gilbert W. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65:499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAteer K, Jing Y, Kao J, Taylor J S, Kennedy M A. Solution-state structure of a DNA dodecamer duplex containing a cis-syn thymine cyclobutane dimer, the major UV photoproduct of DNA. J Mol Biol. 1998;282:1013–1032. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehl R A, Begley T P. Mechanistic studies on the formation and repair of a novel DNA photolesion: the spore photoproduct. Org Lett. 1999;1:1065–1066. doi: 10.1021/ol9908676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohr S C, Sokolov N V H A, He C, Setlow P. Binding of small, acid-soluble proteins from Bacillus subtilis changes the conformation of DNA from B to A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:77–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munakata N, Rupert C S. Genetically controlled removal of “spore photoproduct” from deoxyribonucleic acid of ultraviolet-irradiated Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol. 1972;111:192–198. doi: 10.1128/jb.111.1.192-198.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munakata N, Rupert C S. Dark repair of DNA containing “spore photoproduct” in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Gen Genet. 1974;130:239–250. doi: 10.1007/BF00268802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicholson W L, Chooback L, Fajardo-Cavazos P. Analysis of spore photoproduct lyase operon (splAB) function using targeted deletion-insertion mutations spanning the Bacillus subtilis operons ptsHI and splAB. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;255:587–594. doi: 10.1007/s004380050532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholson W L, Fajardo-Cavazos P. DNA repair and the ultraviolet radiation resistance of bacterial spores: from the laboratory to the environment. Recent Res Dev Microbiol. 1997;1:125–140. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicholson W L, Munakata N, Horneck G, Melosh H J, Setlow P. Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:548–572. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.3.548-572.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholson W L, Setlow B, Setlow P. Ultraviolet irradiation of DNA complexed with α/β-type small, acid-soluble proteins from spores of Bacillus or Clostridium species makes spore photoproduct but not thymine dimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8288–8292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Outten C E, Outten F W, O'Halloran T V. DNA distortion mechanism for transcriptional activation by ZntR, a Zn(II)-responsive MerR homologue in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37517–37524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearlman D A, Holbrook S R, Pirkle D H, Kim S H. Molecular models for DNA damaged by photoreaction. Science. 1985;227:1304–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.3975615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahn R O, Hosszu J L. Influence of relative humidity on the photochemistry of DNA films. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;190:126–131. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(69)90161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rebeil R, Sun Y, Chooback L, Pedraza-Reyes M, Kinsland C, Begley T P, Nicholson W L. Spore photoproduct lyase from Bacillus subtilis spores is a novel iron-sulfur DNA repair enzyme which shares features with proteins such as class III anaerobic ribonucleotide reductases and pyruvate-formate lyases. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4879–4885. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4879-4885.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Setlow B, Setlow P. Thymine-containing dimers as well as spore photoproducts are found in ultraviolet-irradiated Bacillus subtilis spores that lack small, acid-soluble proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:421–423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Setlow P. Mechanisms for the prevention of damage to DNA in spores of Bacillus species. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:29–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Setlow P. Bacterial spore resistance. In: Storz G, Hengge-Aronis R, editors. Bacterial stress responses. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. pp. 217–233. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi Q, Thresher R, Sancar A, Griffith J. Electron microscopic study of Uvr(A)BC excinuclease: DNA is sharply bent in the UvrB-DNA complex. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:425–432. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90957-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y, Palasingam K, Nicholson W L. High-pressure liquid chromatography assay for quantitatively monitoring spore photoproduct repair mediated by spore photoproduct lyase during germination of UV-irradiated Bacillus subtilis spores. Anal Biochem. 1994;221:61–65. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Todo T, Ryo H, Yamamoto K, Toh H, Inui T, Ayaki H, Nomura T, Ikenaga M. Similarity among the Drosophila (6-4) photolyase, a human photolyase homolog, and the DNA photolyase-blue-light photoreceptor family. Science. 1996;272:109–112. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong K K, Kozaritch J W. S-Adenosylmethionine-dependent radical formation in anaerobic systems. In: Sigel H, Sigel A, editors. Metal ions in biological systems. 30. Metalloenzymes involving amino acid and related radicals. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1994. pp. 279–313. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xue Y, Nicholson W L. The two major DNA repair pathways, nucleotide excision repair and spore photoproduct lyase, are sufficient for the resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to artificial UV-C and UV-B but not to solar radiation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2221–2227. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2221-2227.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Q, Soares de Olveira S, Colangeli R, Gennaro M L. Binding of a novel host factor to the pT181 plasmid replication enhancer. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:684–688. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.684-688.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]