Abstract

Objective

Antimicrobial resistance is an increasing health problem worldwide with serious implications in global health. The overuse and misuse of antimicrobials has resulted in the spread of antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms in humans, animals and the environment. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance provides important information contributing to understanding dissemination within these environments. These data are often unavailable in low- and middle-income countries, such as Peru. This review aimed to determine the levels of antimicrobial resistance in non-clinical Escherichia coli beyond the clinical setting in Peru.

Methods

We searched 2009–2019 literature in PUBMED, Google Scholar and local repositories.

Results

Thirty manuscripts including human, food, environmental, livestock, pets and/or wild animals’ samples were found. The analysis showed high resistance levels to a variety of antimicrobial agents, with >90% of resistance for streptomycin and non-extended-spectrum cephalosporin in livestock and food. High levels of rifamycin resistance were also found in non-clinical samples from humans. In pets, resistance levels of 70–>90% were detected for quinolones tetracycline and non-extended spectrum cephalosporins. The results suggest higher levels of antimicrobial resistance in captive than in free-ranging wild-animals. Finally, among environmental samples, 50–70% of resistance to non-extended-spectrum cephalosporin and streptomycin was found.

Conclusions

High levels of resistance, especially related to old antibacterial agents, such as streptomycin, 1st and 2nd generation cephalosporins, tetracyclines or first-generation quinolones were detected. Antimicrobial use and control measures are needed with a One Health approach to identify the main drivers of antimicrobial resistance due to interconnected human, animal and environmental habitats.

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, One health, Escherichia coli

Highlights

-

•

In livestock and food >90% of streptomycin and cephalosporin resistance was detected.

-

•

High levels of rifamycin resistance were found in non-clinical samples from humans.

-

•

High levels to quinolones tetracycline and cephalosporins were detected in pets.

-

•

Environmental samples showed 50–70% of resistance to cephalosporins and streptomycin.

-

•

In general, high levels of resistance to ancient antibacterial agents was observed.

Antimicrobial resistance; One health; Escherichia coli.

1. Introduction

1.1. Antibiotic resistance: origin and where we are

From the last third of the 19th century, efforts to find or synthetize molecules able to efficiently fight infectious diseases were continuous, with the introduction of penicillin into clinical practice in the 1940's [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Since then, antimicrobial agents play a crucial role in reducing morbidity and mortality caused by bacterial infections, being indispensable for the practice of modern medicine. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is an ancient phenomenon related to a series of mechanisms, which have coevolved in parallel with antibiotics to either avoid self-killing of antibiotic-producer microorganisms or to provide a selective advantage to other microorganisms when near an antibiotic source [7, 8]. Nonetheless, different factors, such as the maintenance of a series of additional structures, expression genes or related cellular network alterations, often negatively impact bacterial fitness and result in a selective disadvantage in free-antibiotic environments [9].

Currently, AMR has been reported for all the antimicrobial families, with the presence of pan-resistant microorganisms being considered a major and growing health challenge with serious economic impact [10, 11, 12, 13]. Thus, in 2019, the Center for Diseases Control (CDC) considered that in the USA more than 2.8 million people developed infection by multidrug-resistant (MDR) microorganisms, leading to 35,000 deaths [14]. Also, it estimated that 4.95 million deaths were associated with bacterial AMR, being 1.27 million deaths attributable to bacterial AMR [15]. While controversial, the most negative forecast has projected that around 10,000,000 deaths worldwide related to antibiotic-resistant microorganisms can be foreseen in 2050 [16], resulting in an economic loss of $ 1.2 trillion worldwide, with a special impact on the most disfavored countries [17]. In 2015, this situation led the World Health Organization to design a worldwide strategy to fight AMR with posterior discussion in a plenary session of United Nations on September 21, 2016 of the problem of antibiotic resistance (https://www.un.org/pga/71/event-latest/high-level-meeting-on-antimicrobial-resistance/). These findings have underlined the absolute need to design strategies and actions to avoid the risk of a full loss of usefulness of antibiotics.

1.2. Antibiotic resistance in low- and middle-income countries

Low- and middle-income countries are characterized by a high burden of infectious diseases, and resistance rates that are even greater than in industrialized countries [18]. The emergence and spread of resistance to antimicrobials in Latin America is not an exception, producing an even greater challenge for the fight against infectious diseases. In these countries, resistance to antimicrobials is multifactorial, and it is especially related to inadequate use of antibiotics, environmental changes and rapid growth of the population, with the majority of people living in large cities and suburbs with poor hygienic conditions and often inadequate sanitation. In addition, basic problems such as malnutrition and anemia, which have a direct impact on the immune system, and even sociocultural attitudes that affect the misuse of medications, also play a role in this scenario [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. It is important to highlight that the lack of regulation and control of access to antibiotics, both by humans and for veterinary use are also key points to be considered. Indeed, the overuse of antibiotics in human and veterinary medicine contributes to high local antibiotic pressure inducing major selective pressure leading to the emergence and spread of resistance [22, 23, 24].

1.3. Antibiotic resistance: situation in Latin America and Peru

Fueled by the above-mentioned aspects, in recent years, antibiotic resistance has been a growing problem in Latin America [25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. The data available suggest that in this region, antibiotic resistance of the most common pathogens has reached unacceptable levels, with reported values of 90–100% resistance to different antimicrobial, such as carbapenems in Acinetobacter baumannii [27, 30]. Peru is a upper-middle-income country (https://data.worldbank.org/?locations=PE-XT), with around 33 million inhabitants in 2020; of these ∼9.7 million inhabitants (29.7%) live in the Lima department, mostly in the metropolitan area (http://m.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/noticias/notadeprensa006.pdf). The country has 3 clearly delimited geographical areas: the coast, on the western side, the highlands in the center, and the jungle, on the east side of the country. Peru presents clear inequities between rural and urban areas, although these inequities are declining. This scenario as well as the difficult access to health facilities, either because of distance or economical costs, often results in inadequate medical assistance and a lack of effective control of access to antibiotics, contributing to self-medication practices [21, 31].

1.4. Antibiotic resistance beyond clinical data

Different interconnected human, animal and environmental media contribute to the emergence and dissemination of antibiotic resistance, with this concept being the basis of the so-called One Health approach [23]. Thus, the antibiotic resistance levels of these habitats can have a final impact on human health [32]. Data on the relevance of commensal and environmental microorganisms as a reservoir of antibiotic resistance determinants is growing worldwide [33, 34, 35]. Nonetheless, regarding Peru data are scarce, being mostly fragmented and sometimes reported in difficult to access documents.

1.5. Escherichia coli

Escherichia coli ranks among the most relevant human pathogens isolated as a cause of a high diversity of pathogenic process [36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42], even involving animals [43, 44, 45]. Moreover, it colonizes the gastrointestinal tract of humans and animals as a commensal microorganism, being commonly isolated from foods of animal origin, as well as vegetables, water and soil [42, 46, 47, 48]. Thus, E. coli is a good bacterial marker for studies including a variety of sources and would be an excellent marker to draw the antibiotic resistance scenario beyond classical clinical approaches and points of view.

In this scenario, this manuscript aims to provide an overview of the resistance profiles of non-clinical recovered E. coli in Peru in relation to the sources from which they were found from 2009-2019.

2. Search method

Articles containing the terms ((Escherichia coli) AND Peru) AND antibiotic resistance) were sought in PubMed. The results were complemented by searching in Google Scholar and local academic repositories. Limits were placed on reports (articles or Thesis) published from 2009-2019 in either Spanish or English languages. Only studies reporting numeric or percentual values of antibiotic resistance levels (obtained by disk diffusion or by minimal inhibitory concentration) in E. coli recovered from non-clinical (i.e.: E. coli does not isolate as a cause of human disease) human sources were considered. When more than one report referred to the same bacterial collection only one was considered for statistical purposes irrespective of complementing the resistance data with information present in other related reports.

Studies reporting resistance data in non-standardized formats such as “median of halo diameter” were not included in the study because of the inability to establish the levels of antibiotic resistance. Although the articles in which the microorganisms were isolated in antibiotic-supplemented media were included in the bibliometric analysis and the data were used in the discussion, they were not used to determine and analyze the levels of resistance due to selection bias. All E. coli from healthy people were collectively analyzed irrespective of their pathogenic potential [49]. Finally, intermediate isolates were added to resistant isolates to determine the number of non-susceptible isolates.

3. Results of the bibliometric analysis

The PubMed search resulted in 42 articles fulfilling the search criteria, 10 of which were selected after visual inspection. In addition, 20 other studies were obtained from Google scholar and university repositories: 1 article from a PubMed indexed journal (but not detected using the search strategy), 11 articles published in local or other non-PubMed indexed journals (LJ/NPM) and 8 Doctoral [1], Master [2] or Grade [5] Theses (hereafter called Thesis) extracted from local repositories (Table 1). Thus, a total of 30 different studies were considered. Of these, 7 (23.3%) related to livestock and 7 (23.3%) to the environment. Five (16.7%) studies were focused on human commensal E. coli, while 4 (13.3%) and 3 (10.0%) were analyzed pets and wild animals, respectively, and 1 (3.3%) included meat samples. Finally, 3 (10.0%) studies reporting E. coli from different sources were also included. Overall, 4 studies were only considered in the bibliometric analysis because of the above-mentioned selection bias. In the tables, these studies are numbered from 1 to 30 with to facilitate reading and interchangeability of data present in the tables. Five additional studies performing complementary analysis of the same E. coli collections were also revised (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reports of antimicrobial resistance levels in Peruvian non-clinical Escherichia coli published from 2009-2019.

| Sampling |

E. coli |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Yeara | Area | N | Rb | Ref | Type | |

| Human | |||||||

| 1 | Undetermined | 2002 | Lt | 111 | 89 | 50c | PM |

| 2 | Children | 2005 | Lt | 164 | 66 | 51d | PM |

| 3 | Children | 2006–2007 | Lm | 753 | 168 | 49e | PM |

| 4 | Children | <2009 | Cj, Ic Lm, Lt | 523 | 523 | 52 | PM |

| 4 | Adults | <2009 | Cj; Ic, Lm, Lt | 164 | 164 | 52 | PM |

| 5 | Undetermined | 2009 | Lt | 34 | 29 | 28d | PM |

| 6 | Children | 2014–2015 | Cs, Sm | 179 | 179 | 53 | PM |

| Sub-Total | 1928 | 1218 | |||||

| Food | |||||||

| 4 | Chicken | <2009 | Cj, Ic Lm, Lt | 252 | 252 | 52 | PM |

| 7 | Chicken | 2012 | Lm | 159 | 56 | 47 | PM |

| 7 | Pork | 2012 | Lm | 45 | 22 | 47 | PM |

| 7 | Beef | 2012 | Lm | 57 | 25 | 47 | PM |

| 8 | Beef | 2015 | Lm | 154 | 154 | 54 | TH |

| Sub-Total | 667 | 509 | |||||

| Environmental | |||||||

| 9 | Sea water | 1999–2000 | Lm | 55 | 41 | 55 | LJ/NPM |

| 10 | Hospital surfaces | 2009–2010 | Cj | 20 | 20 | 56h | PM |

| 11 | Hospital cell phones | 2012 | Lm | 34 | 34 | 57 | PM |

| 8 | Slaughterhouse | 2015 | Lm | 35 | 35 | 54 | TH |

| 12 | Drinking water (untreated) | 2015–2016 | Cj | 117 | 117 | 58 | PM |

| 13 | Sea water | 2016 | Pr | 108 | 108 | 59 | TH |

| 14 | Sea water | 2017 | Lm | 64 | 64 | 60 | TH |

| 15 | River water (urban area) | 2018–2019 | Pr | 31 | 31 | 61 | TH |

| Sub-Total | 464 | 450 | |||||

| Livestock | |||||||

| 4 | Chicken | <2009 | Lm | 242 | 242 | 52 | PM |

| 16 | Alpaca (Vicugna pacos) | 2007 | Ar, Pn, Cs | 30 | 30 | 44 | LJ/NPM |

| 17 | Pig | 2010–2015 | Lm | 36 | 36 | 62 | LJ/NPM |

| 18 | Pig | 2013 | Lm | 36 | 36 | 63 | LJ/NPM |

| 19 | Alpaca (Vicugna pacos) | 2013 | Hc | 82 | 82 | 64 | LJ/NPM |

| 8 | Cattle (feces) | 2015 | Lm | 70 | 70 | 54 | TH |

| 20 | Variousi | 2015 | Lm | 10 | 10 | 65j | PM |

| 21 | Chicken | 2015–2016 | Ar; Ic; Ll, Lm; Uc | 185 | 185 | 66 | LJ/NPM |

| 22 | Chicken | 2017 | Pr | 50 | 50 | 67 | TH |

| 23 | Cattle | 2017–2018 | Cj | 32 | 32 | 68 | TH |

| Sub-Total | 773 | 773 | |||||

| Pets | |||||||

| 4 | Varioush | <2009 | Cj, Ic, Lm, Lt | 526 | 526 | 52 | PM |

| 24 | Dog | ? | Lm | 12 | 12 | 69 | LJ/NPM |

| 25 | Dog | 2003–2012 | Lm | 14 | 14 | 43 | LJ/NPM |

| 26 | Dog | 2012–2017 | Lm | 45 | 45 | 70 | LJ/NPM |

| 27 | Dog | 2016–2017 | Cj | 100 | 100 | 71 | TH |

| Sub-Total | 697 | 697 | |||||

| Wild Animalsf | |||||||

| 28 | Northern Caiman Lizard (Dracaena guianensis) | 2014 | Lm | 17 | 17 | 72 | TH |

| 29 | Spectacled caiman (Caiman cocodrilus) | 2014 | MdD | 7 | 7 | 73 | LJ/NPM |

| 20 | Common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) | 2015 | Lm | 5 | 5 | 65g | PM |

| 30 | Monkey (Ateles, Callicebus, Lagothrix) | ? | Lt | 45 | 45 | 74 | LJ/NPM |

| Sub-Total | 74 | 74 | |||||

| Overall | 4603 | 3721 | |||||

Ar: Arequipa; Cj: Cajamarca; Cs: Cusco; Hc: Huancavelica; Ic: Ica; Ll: La Libertad; Lm: Lima; Lt: Loreto; MdD. Madre de Dios; Pr: Piura; Pn: Puno; Sm: San Martin; Uc. Ucayali. N: Number of isolates; R: Antimicrobial resistant isolates. PM: PubMed journals; TH: Thesis; NPM: non-PubMed indexed journals; LJ: Local journals.

When the same sampling recovered E. coli from different sources, these are indicated in different rows. Nonetheless, in several cases the data were reported together to avoid an excessive fragmentation of the Table and because they were mainly analyzed together in the original articles, making it difficult to adjudicate the specific results to specific sampling sources. In these cases, the sampling composition is indicated below. Articles 1, 2, 5 and 20 presented a selective bias and were only considered for bibliometric purposes [28, 50, 51, 65]. a: Sampling year. b: The number of E. coli is limited to those for which data on antimicrobial resistance was available. c: Isolates recovered from plates containing antibiotic disks (direct plating method). d: Samples cultured in the presence of 0.12 μg/ml of ciprofloxacin. e: Data about sampling or AMR may also be found in Gomes et al., 2013, Gomes et al., 2019 Ochoa et al., 2009, and Pons et al., 2014 [75, 76, 77, 78]. f: Includes free wild animals [73] and wild animals living in captivity or in semi-captivity [72, 74]. g: The article only reports isolates possessing ESBLs. h: Data about sampling and/or AMR may also be found in Rivera-Jacinto et al., 2015 [79]. i: The sampling including: 20 cows, 8 pigs, 5 sheep, 2 horses and 2 donkeys. j: The article only reports isolates possessing ESBLs (6 from pigs, 4 from cows). h: The sampling included: 224 dogs, 95 cats, 77 guinea pigs, 72 pigs, 64 ducks, 34 cows, 30 rabbits, 27 sheep, 23 turkeys, 15 donkeys, 12 doves, 12 goats, 8 horses, 8 canaries/parrots, 2 geese, 2 monkeys, 1 quail, 1 squirrel, 1 unknown. Note that in Peru guinea pig is considered a food-producing animal, not a pet.

Thirteen studies (43.3%) included samples collected in the department of Lima while 14 (46.7%) used samples from other Peruvian departments, and an additional 3 (10%) studies analyzed samples from more than one department (2 including samples from Lima) (Table 1, Figure 1). Thus, 50% of the studies included samples from the Lima area, clearly showing that the data generated are strongly influenced by the specificities of the Lima department.

Figure 1.

Geographical origin of the studies. The primary politic subdivision of Peru is in Departments. Those Departments from which were analyzed samples, are highlighted in color, and the name has been added in the map. Note that these marks does no preclude the authorship of authors based in these regions. Similarly, the symbols in the map only refers to Department, no to specific areas within each department. Note that in the map Callao, a special Peruvian administrative region, with range equivalent to Department, is included within Lima department. In fact, Callao is surrounded by the sea and the metropolitan area of Lima city.

3.1. Overall vision of non-clinical Escherichia coli studies in Peru

The number of analyzed non-clinical E. coli during the 2009–2020 period is scarce, with only 3721 isolates with data of antimicrobial resistance. Of note, most of them (1218 isolates, 32.7%) being human commensal isolates, with that analyzing wild-animal recovered E. coli accounting only for 74 isolates (Table 1). This finding, together the presence of a series of data non-reported in an article format, highlighting the need for new and longer studies.

3.2. Human Commensal Escherichia coli

Three studies reported the AMR levels of human commensal E. coli. Of these, 1 analyzed samples from Lima [49], another samples from San Martin and Cusco [53], and the remaining study analyzed samples from 4 Peruvian departments, including Lima [52].

While not included in the analyses of resistance to antimicrobial agents because of the use of antibiotic supplemented media (ciprofloxacin) or colony selection inside halos of antibiotic disks, 3 studies reported resistance levels of E. coli from non-pathogenic human samples [28, 50, 51] collected from 2002, 2005 and 2009 respectively in remote areas of the Loreto department.

The studies focused on healthy people ranks among the most ancient of those included in the present study (Table 1). This scenario showing that the number of studies reporting the levels of AMR among human commensal E. coli in Peru are scarce and mostly outdated, with all but one referring E. coli collected before 2009, with this panorama also extended to the 3 non-included studies [28, 49, 50, 51, 52]. The remaining study analyzing isolates collected on 2014–2015 [53]. This scenario is probably common to a series of low- and middle-income countries for which this type of data is scarce or often unavailable.

Resistance to ancient antimicrobial agents such as ampicillin or cotrimoxazole was high, being of note that these agents are widely used in pediatric population in the area [80]. In this regard, Kalter et al. analyzed samples from both children and adults finding ampicillin and cotrimoxazole resistance levels of 53.7% and 51.8% in children and 37.2% and 21.3% in adults, respectively [52]. Macrolides are also used in pediatric populations for the treatment of respiratory infections and diarrhea [80, 81], with analyzed data reporting resistance to azithromycin ranging between 15,6% and 27.4% [53, 76]. In contrast to quinolones, resistance to macrolides in E. coli (and other Enterobacteriales) is mostly related to transferable mechanisms (especially mphA), with a role for efflux pumps rather than to target mutations [76, 82].

Of note, resistance to ancient quinolones, such as nalidixic acid, ranged between 38.7 and 43.0%. Quinolones are usually not used in pediatric populations. Mosquito et al. showed that non-diarrheagenic E. coli were significantly more resistant to ancient quinolones than diarrheogenic E. coli, recovered from either ill or healthy children [49]. Furthermore, while transferable mechanisms of quinolone resistance have been described in the area [83], including in several of above-mentioned isolates [77], resistance to these antimicrobial agents is largely mediated by chromosomal mutations [77, 84], suggesting an exogenous origin of these isolates. High levels of quinolone resistance in microorganisms from other sources, such as food-samples [47] could make this a plausible option.

Except for tetracycline, resistance levels to other antimicrobial agents were almost negligible, including resistance to carbapenems as shown in samples from other sources (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage of antimicrobial resistance in human commensal Escherichia coli.

| Articles | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Ch | Ch | A | Ch |

| No | 168 | 523 | 164 | 179 |

| Year | 2006–2007 | <2009 | <2009 | 2014–2015 |

| Antimicrobial Resistance | ||||

| Amp | 76.8 | 53.7 | 37.2 | 51.4 |

| A/C | 15.1 | |||

| Ctx | 5.6 | |||

| Cxm | 7.7 | |||

| Fox | 2.8 | |||

| Cro | 0.0 | 0.6 | 4.5 | |

| Imp | 4.0 | |||

| Tc | 56.5 | |||

| Sxt | 62.5 | 51.8 | 21.3 | 50.8 |

| Chl | 22.0 | |||

| Azm | 27.4a | 15.6 | ||

| Nal | 38.7 | 43.0 | ||

| Cip | 13.1 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 9.0 |

| Gm | 3.4 | |||

| Nit | 2.3 | |||

| Rfx | 93.2b | |||

| Other | ||||

| MDR | 50.1 | |||

Year: Sampling year. Ch: Children; A: Adults; Amp: Ampicillin; A/C: Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid; Ctx: Cefotaxime; Cxm: Cefuroxime; Fox: Cefoxitin; Cro: Ceftriaxone; Imp: Imipenem; Tc: Tetracycline; Sxt: Cotrimoxazole; Chl: Chloramphenicol; Azm: Azithromycin; Nal: Nalidixic acid; Cip: Ciprofloxacin; Gm: Gentamicin; Nit: Nitrofurantoin; Rfx: Rifaximin; MDR: Multidrug Resistance. a Eighty-four isolates analyzed [76]. b Seventy-four isolates analyzed, all with a MIC ≥32 μg/L [75].

3.3. Escherichia coli recovered from food

The studies on food samples were all focused on pre-marketed (meat food in slaughterhouses) or marketed meats (chicken, beef and pork) with no study reporting data on vegetables or other foodstuffs. Three studies were included in the analysis [47, 52, 54]: 2 from Lima and 1 including samples from Lima and 3 other Peruvian regions (Cajamarca, Ica, Loreto) (Table 1, Figure 1).

All the studies showed high levels of resistance to ampicillin, tetracycline, nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin, ranging from 19.5% to 96.4%, irrespective of the meat sample. Meanwhile, resistance levels to other antimicrobial agents varied among different studies and samples. For instance, resistance to cotrimoxazole ranged from 1.2% in beef samples to 100% in chicken samples [47, 54]. Similarly, resistance to chloramphenicol varied from 8% in beef samples to 83.9% in chicken samples [47]. Regarding furazolidone, the resistance levels of 35.7% and 31.8% were of note in chicken and pork samples, respectively. Azithromycin resistance of 39.3% was relevant among chicken samples. Cephalothin, sulfamethoxazole, streptomycin, amikacin and gentamicin were only tested in one type of meat sample, showing resistance values ranging from 14.9% to 98.7%. Of note, while used until 2019 in veterinary medicine in Peru [85], none of the studies provided data about colistin resistance. Finally, resistance to ceftriaxone in chicken meat was low with 0.8% [52]. MDR values ranged from 28.0% to 98.2% among beef and chicken samples, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage of antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli from marketed foods.

| Articles |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 | |

| General Data | |||||

| Sample | C | C | B | B | P |

| No | 252 | 56 | 25 | 154 | 22 |

| Year | <2009 | 2012 | 2012 | 2015 | 2012 |

| Antimicrobial Resistance (%) | |||||

| Amp | 46.0 | 94.6 | 44.0 | 65.6 | 95.4 |

| A/C | 41.1 | 16.0 | 4.5 | ||

| Kf | 91.7 | ||||

| Cro | 0.8 | ||||

| Tc | 94.6 | 56.0 | 20.1 | 90.9 | |

| Sxt | 100.0 | 20.0 | 1.2 | 54.5 | |

| Smz | 52.5 | ||||

| Chl | 83.9 | 8.0 | 54.5 | ||

| S | 91.5 | ||||

| Azm | 39.3 | 8.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Nal | 94.6 | 44.0 | 38.3 | 77.3 | |

| Cip | 20.6 | 96.4 | 48.0 | 19.5 | 81.8 |

| Ak | 22.7 | ||||

| Gm | 14.9 | ||||

| Fur | 35.7 | 4.0 | 31.8 | ||

| Other | |||||

| MDR | 98.2 | 28.0 | 86.4 | ||

| ESBL | 59.4c | 0.0d | |||

| pAmpC | 6.2c | 5.0d | |||

Year: sampling year. Amp: ampicillin; A/C: amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid; Kf: cefalotin; Cro: ceftriaxone; Tc: tetracycline; Sxt: cotrimoxazole; Smz: sulfamethoxazole; Chl: chloramphenicol; S: streptomycin; Azm: azithromycin; Nal: nalidixic acid; Cip: ciprofloxacin; Ak: amikacin; Gm: gentamicin; Fur: furazolidone; MDR: multidrug-resistant; ESBL: extended-spectrum β-lactamases, pAmpC: plasmid-encoded AmpC; C: chicken; B: Beef; P: pork. a Following the order described in Table 1. b Sampling year. c Thirty-two samples analyzed. d Twenty samples analyzed.

Overall, the analysis of the studies showed high levels of AMR which may be related to food-production systems, with chicken generally showing the highest levels of resistance to the antimicrobial agents tested. This finding agrees with the high levels of poultry production in Peru (>1.5 million of Tm in 2018) [86]. Further, Kalter et al. [52] reported that chicken samples from the Lima area showed higher levels of resistance to ampicillin and ciprofloxacin than those collected from other Peruvian regions. This finding, together the high levels of resistance to these and other antimicrobial agents observed in other studies using samples from Lima [47, 54], suggest that chickens consumed in Lima were grown in the presence of higher levels of antimicrobial agents. In this sense, antibacterial agents such as enrofloxacin, a member of the quinolone family, or ampicillin and amoxicillin (both β-lactam agents), have been largely used in poultry [87, 88]. Regarding Peru, while updated data of specific antibiotic usage on poultry are lacking, studies analyzing the presence of antibiotic residue in marketed chicken meat have described the presence of enrofloxacin traces in 56% of the samples analyzed [89].

The presence of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) and pAmpC was sought in a subset of chicken (32 samples) and beef (20 samples), showing significant differences related to the sample source. Thus, 59.4% of chicken samples presented ESBL-producing E. coli, while none was detected from beef samples. Meanwhile, 6.8% and 5% of pAmpC-producing E. coli were detected in chicken and beef samples, respectively. This finding again agrees with a high antibiotic pressure in poultry farms. Likewise, the presence of other microorganisms such as MDR Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis carrying ESBL has been observed in chicken meat marketed in Lima [47], presenting the same clone in both chicken meat and ill children [90].

All these findings highlight the potential role of marketed meat in Peru as a diffusor of pathogenic microorganisms as well as AMR determinants. While most E. coli would be not pathogenic and would remain unnoticed, they, or any of their AMR genes, might be incorporated into the human gut microbiota and thereby act as a hidden AMR reservoir [34].

3.4. Environmental Escherichia coli

Of a total of 8 studies [54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61], 3 were developed with sea water, 1 with river water and another with untreated water used for all household purposes. The remaining 3 studies were developed in hospital surfaces, personal devices of health workers, and over devices and surfaces of a slaughterhouse. All studies but 3 were performed in Lima, while 2 were performed in Cajamarca samples (hospital surfaces and drinking water respectively) and 1 in Piura analyzing river water.

Relevant levels of resistance of ampicillin were detected (Table 4). High levels of ampicillin resistance of river and drinking water [58, 61] is of special concern. In fact, E. coli from river water presented high levels of ampicillin (80.6%) and cotrimoxazole (41.9%) resistance. E. coli from river water also showed significant levels of resistance to other antibiotics such as cefotaxime (35.5%) and gentamicin (19.4%) [61]. In a scenario of uncontrolled access to antibacterial agents, the presence of these levels of resistance to ancient (and relatively cheap) antimicrobial agents such as ampicillin in water sources, seems to be related to anthropogenic activities such as discharge of antimicrobial agents in the environment (either directly or through human/animal excretion), or contamination with fecal antibiotic-resistant microorganisms. In this sense, the problematic of industrial, agrarian and urban discharges in the Piura River has been highlighted [91].

Table 4.

Antimicrobial resistance levels in environmental Escherichia coli.

| Articles |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| General Data | ||||||||

| Sample | Slt | SW | HS | HS | DW | SW | SW | RW |

| No | 35 | 41 | 20 | 34 | 117 | 108 | 64 | 31 |

| Year | 2015 | 1999–2000 | 2009–2010 | 2012 | 2015–2016 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018–2019 |

| Antimicrobial Resistance (%) | ||||||||

| Amp | 80.0 | 19.5 | 60.0 | --- | 51.3 | --- | 48.5 | 80.6 |

| Amx | ---a | 17.1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| A/C | --- | --- | --- | --- | 9.4 | --- | --- | --- |

| Spz | --- | 0.0 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Atm | --- | 2.4 | 25.0 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 25.8 |

| Kf | 100.0 | --- | 75.0 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Ctx | --- | --- | 20.0 | --- | 5.1 | 36.1 | --- | 35.5 |

| Cro | --- | --- | 20.0 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 35.5 |

| Fox | --- | --- | 10.0 | 8.8 | 3.2 | --- | --- | --- |

| Caz | --- | 0.0 | 10.0 | --- | --- | 23.1 | --- | 16.1 |

| Fep | --- | --- | 20.0 | --- | --- | 25.9 | --- | --- |

| Mem | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.0 | --- | --- |

| Tc | 40.0 | 17.1 | --- | --- | 32.5 | --- | 40.4 | --- |

| Sxt | 17.1 | 17.1 | --- | 44.1 | 19.8 | 19.4 | 31.3 | 41.9 |

| Chl | 25.7 | 2.4 | --- | --- | 11.1 | --- | 9.9 | --- |

| S | 71.5 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Azm | --- | --- | --- | --- | 6.8 | --- | --- | --- |

| Nal | 75.7 | 7.3 | --- | --- | 14.5 | --- | 50.0 | --- |

| Nor | --- | 0.0 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Cip | 31.4b | 0.0 | --- | 61.8 | 9.4 | 8.3 | --- | 9.7 |

| Ak | 14.3 | 4.9 | --- | 5.9 | --- | --- | --- | 0.0 |

| Gm | 17.1 | 0.0 | --- | 32.4 | 2.6 | --- | --- | 19.4 |

| Km | --- | 2.4 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Tob | --- | --- | --- | 47.1 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Nit | --- | --- | --- | --- | 5.1 | --- | --- | --- |

| Other | ||||||||

| MDR | --- | 9.1 | --- | 35.3 | 19.7 | --- | 26.6 | --- |

| ESBL | --- | --- | 20.0 | 55.9 | 5.1 | 18.5 | 16.1 | |

| pAmpC | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

Year: sampling year; Slt: Slaugterhouse (devices and surfaces); SW: Sea water; HS: Hospital surfaces (in study 32 referring to medical personal devices); DW: Drinking water; RW: River water; Y: Year; Amp: Ampicillin; Amx: Amoxicillin; A/C: Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid; Spz Sulperazone (cefoperazone plus sulbactam); Atm: Aztreonam; Kf: cefalotin; Ctx: cefotaxime; Cro: Ceftriaxone; Fox: Cefoxitin; Caz: Ceftazidime; Fep: Cefepime; Mem: Meropenem; Tc: Tetracycline; Sxt: Cotrimoxazole; Chl: Chloramphenicol; S: Streptomycin; Azm: Azithromycin; Nal: Nalidixic acid; Nor: Norfloxacin; Cip: Ciprofloxacin; Ak: Amikacin; Gm: Gentamicin; Km: Kanamycin; Tob: Tobramycin; Nit: Nitrofurantoin; MDR: Multidrug Resistance; ESBL: Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases; pAmpC: Plasmid encoded AmpC. a Not reported/not determined/cannot be extrapolated from data. b All intermediate.

Although only 3 studies focused on surfaces and devices, the E. coli from these studies presented overall higher levels of AMR, probably reflecting the specificities of the study settings, a hospital and a slaughterhouse. In hospital environments the use of antimicrobial agents is intense, resulting in direct antimicrobial pressure over microorganisms and the subsequent selection of AMR [92]. Indeed, isolation of MDR, extensively resistant (XDR) and even pan-drug resistant (PDR) microorganisms is frequent worldwide and is of special concern [17, 77, 93, 94, 95]. This finding is extrapolated to Peru, in which the levels of AMR among microorganisms causing infections are extremely high [30, 82, 96]. In this regard, the presence of highly resistant E. coli, including 66% of ESBL-producer E. coli in the personal devices of intensive care unit health care workers (i.e. mobile phones) highlights the ease with which a MDR microorganism may be transported within different hospital areas or outside hospitals [57].

Meanwhile, the high levels of resistance to antimicrobial agents such as ampicillin (80%), cephalothin (100%), nalidixic acid (75.7%) or tetracycline (40%), among others, detected in E. coli from a slaughterhouse environment, probably reflect environmental contamination by antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms colonizing sacrificed livestock. This finding is supported by the available literature about AMR levels of E. coli from both livestock and food-marketed meats (see sections 3 and 3.2 respectively). Curiously, while 31.5% of the isolates from slaughterhouse surfaces were ciprofloxacin intermediate, no ciprofloxacin-resistant was isolated. Nevertheless, 75.5% of isolates showed nalidixic acid resistance (Table 4). Of note, the phenotype NalR, CipI/S (or another fluoroquinolone) is usually related to the presence of a single mutation in gyrA [84, 97] and is associated with enhanced facility to drive to selection of additional target mutations and therapeutic failure when fluoroquinolones are used [97, 98, 99].

In general, the levels of resistance to amikacin and meropenem were low or null. The analysis of E. coli or other Enterobacteriales of clinical origin, also showed that amikacin retains good activity in Peru [26, 96]. Meanwhile, the presence of carbapenem-resistant clinical isolates of E. coli has been described but remains low [82, 100, 101]. Therefore, although only one of the studies analyzed reported susceptibility data of meropenem, the good activity of amikacin and meropenem against environmental E. coli seems to reflect the overall picture of resistance to these antimicrobial agents in Peru.

3.5. Livestock recovered Escherichia coli

Several studies were focused on a variety of livestock, with data about chicken in 3 studies, and of pigs, cattle and alpacas in 2 studies each; thus, 9 studies were considered in the analysis [44, 52, 54, 62, 63, 64, 66, 67, 68]. Of these, only 3 were total or partially developed using samples from Lima (Table 1, Figure 1). Another study was not included due to bacterial selection bias [65].

While a high variety of tested antibiotics was observed (total of 30 antimicrobial agents tested), none was included in all studies, with only members of the quinolone family being tested in all studies, highlighting the relevance of these agents in veterinary medicine during the last decade in Peru.

Resistance to the antibiotics tested was common and high in all studies except in the oldest isolates recovered from chicken prior to 2009, showing the highest resistance to ampicillin and sulfamethoxazole with 12.5% and 12.8%, respectively [52] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Percentage of antimicrobial resistance in livestock samples.

| Articles |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 8 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 23 | |

| General Data | |||||||||

| Sample | Ch | Ct | Alp | Pig | Pig | Alp | Ch | Ch | Ct |

| No | 242 | 70 | 30 | 36 | 36 | 82 | 185 | 50 | 32 |

| Year | <2009 | 2015 | 2007 | 2010–15 | 2013 | 2013 | 2015–16 | 2016 | 2017–18 |

| Antimicrobial Resistance (%) | |||||||||

| Amp | 12.4 | 71.4 | 70.0∗ | 100 | |||||

| Amx | 0.0 | ||||||||

| A/C | 69.4 | 90.2 | |||||||

| Atm | 38.9 | ||||||||

| Kf | 97.2 | 100 | |||||||

| Ctx | 41.7 | ||||||||

| Cro | 0.8 | 33.3 | 28.0∗ | ||||||

| Fox | 25.0 | ||||||||

| Caz | 47.2 | 22.0 | |||||||

| Fep | 44.4 | ||||||||

| Oxt | 94.0∗ | 37.0∗ | 95.0 | 54.0 | 40.6 | ||||

| Dox | 36.0∗ | ||||||||

| Tc | 38.6 | 100.0 | |||||||

| Sxt | 12.9 | 6.0 | 80.6 | 2.0 | 87.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Sulfa | 12.8 | ||||||||

| Chl | 7.1 | 70.0∗ | 44.4 | ||||||

| Flor | 65.8 | ||||||||

| S | 88.6 | 75.0∗ | 94.4 | ||||||

| Nal | 78.5 | 88.9 | 94.4 | ||||||

| Cip | 2.5 | 34.3∗ | 47.2 | 33.3 | 26.0∗ | ||||

| Enr | 12.0 | 61.0∗ | 83.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Ak | 37.1 | 16.7 | 11.1∗ | 41.0∗ | |||||

| Gm | 47.2 | 55.0∗ | 44.4 | 19.4 | 5.0 | ||||

| Km | 27.8 | ||||||||

| Nm | 94.0 | 58.3 | 37.5 | ||||||

| Tob | 97.2 | ||||||||

| Nit | 91.3 | ||||||||

| Fos | 12 | 62.7 | |||||||

| Col | 21.3 | ||||||||

| Other | |||||||||

| MDR | |||||||||

| ESBL | 0.0 | 38.4 | |||||||

| pAmpC | 3.0 | ||||||||

Year: sampling year; Alp: Alpaca; C: Chicken; Ct: Cattle; Y: Year; Amp: Ampicillin; Amx: Amoxicillin; A/C: Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid; Atm: Aztreonam; Kf: cefalotin; Ctx: cefotaxime; Cro: Ceftriaxona Fox: Cefoxitin; Caz: Ceftazidime; Fep: Cefepime; Mem: Oxt: Oxytetracycline; Dox: doxyciline; Tc: Tetracycline; Sxt: Cotrimoxazole; Sulfa: Sulfamethoxazole; Chl: Chloramphenicol; Flor: Florfenicol; S: Streptomycin; Azm: Azithromycin; Nal: Nalidixic acid; Cip: Ciprofloxacin; Enr: Enrofloxacin; Ak: Amikacin; Gm: Gentamicin; Km: Kanamycin; Nm: Neomycin; Tob: Tobramycin; Nit: Nitrofurantoin; Fos: Fosfomycin; Col: Colistin; MDR: Multidrug Resistance; ESBL: Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases; pAmpC: Plasmid encoded AmpC. ∗Most of them being intermediate.

Interestingly, as mentioned above, Kalter et al. also analyzed marketed chicken meat, detecting substantially higher levels of resistance to these agents (see section 3.2), suggesting differences in antibiotic use between household and industrially raised chicken [52]. The other 2 studies in industrially raised chicken [66, 67] collected in 2016 and 2017–2018, respectively, showed dissimilar results. The study by Vilchez-Chiara showed high resistance levels to tetracyclines (oxytetracycline and doxycycline) but full susceptibility to amoxicillin, enrofloxacin and cotrimoxazole [67], while Ceino-Gordillo et al. described overall high levels of resistance to all the antibacterial agents tested, reaching 95% and 90.2% in the cases of oxytetracycline and amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid [66]. The only difference between the two studies was the geographic origin of the samples.

While only reported in one out of 9 studies [66], 23.1% of resistance to colistin is worrisome. Colistin is considered as a last resort antibacterial agent in hospital settings, being used when no other alternative is available [102]. Although colistin is currently forbidden for veterinary applications in a growing number of countries, it has been used in veterinary settings for years [103, 104]. In Peru, veterinary uses of colistin were forbidden in December 2019 [85], after the E. coli collection of Ceino-Gordillo et al. [66]. This finding might explain Ceino-Gordillo et al. data, but the analysis of isolates collected from 2020 onwards is of special relevance to determine the stability or reversion of these resistance levels. There are no data about molecular mechanisms underlying resistance to colistin in these isolates, which if mediated through mcr genes is at risk of being horizontally disseminated to pathogenic microorganisms [105].

Of note were the high levels of resistance to quinolones detected in 6 out of 9 studies. In several cases resistance to nalidixic acid was higher than 78% and up to 94% [63] Although the emergence of transferable mechanisms of quinolone resistance has slightly altered the scenario [8], these resistance levels are mostly related to the presence of mutations in quinolone targets [84, 97, 106], which might not imply the surpassing of fluoroquinolone resistance breakpoints, but have been associated with enhanced levels of therapeutic failures during fluoroquinolone treatments [99]. Of note, in other microorganisms, such as Campylobacter spp., isolation of quinolone-resistant isolates in clinical settings was parallel to the increasing levels of quinolone resistance among poultry isolates following the introduction of enrofloxacin in veterinary medicine [22].

Five reports showed >30% of aminoglycoside intermediate or resistant isolates. The presence of intermediate isolates either to aminoglycosides or other antibacterial agents was frequent among E. coli recovered from livestock samples, especially in the 2 studies using E. coli recovered from Alpacas. Thus, Luna et al. reported ∼70%, ∼70%, ∼65%, ∼55% and ∼40% of intermediate isolates to oxytetracycline, streptomycin, ampicillin, chloramphenicol and gentamicin, respectively, and Barrios-Arpi et al. reported 50%, 29%, 28%, 26% and 22% of intermediate levels of resistance to enrofloxacin, amikacin, oxytetracycline, ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin, respectively [44, 64]. The high number of isolates exhibiting intermediate resistance levels to a series of unrelated antibiotics might be related to the presence of subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations favoring the selection of non-specific low-level resistance mechanisms, such as overexpression of efflux pumps or other adaptative responses, or to external factors, such as the presence of environmental contaminants (e.g: heavy metals, chemicals, solvents), which might favor similar scenarios [107, 108, 109]. In this sense, a study analyzing the mechanisms of rifaximin resistance in 74 commensal and 136 diarrheogenic isolates from a periurban area of Lima showed an unusual scenario, with 100% of the isolates having a minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) ≥32 mg/L [75], when studies on E. coli with a very diverse geographical origin only showed the presence of a few E. coli isolates presenting a maximum MIC of ≥32 mg/L [40, 110, 111, 112]. This atypical resistance pattern was related to the presence of overexpressed efflux pumps in 95.2% of the isolates, with only 9 out of 200 (4.5%) isolates having MICs ≥32 mg/L after the use of an efflux pump inhibitor [75]. Of note, the presence of heavy metals such as arsenic, chrome, cadmium, lead, mercury or zinc, and other toxics such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon has been widely described in different Peruvian areas [113, 114, 115, 116].

The presence of ESBLs was reported in 3 studies [62, 65, 66], which were not considered in the analysis of AMR because the samples were directly screened for ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. These studies showed the presence of ESBLs in samples from chickens, cows and pigs, reporting the presence of blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-15 and blaCTX-M-26 [62,65,66].

3.6. Pet-isolated Escherichia coli

Five studies reported data about AMR in E. coli recovered from pets. Of this, four were focused on dogs [43, 69, 70, 71], while the remaining study considered a diversity of animals, including pets such as dogs, and also ducks and guinea pigs, which are consumed, or others including donkeys used in the agrarian setting [52]. Three of these studies were developed in Lima [43, 69, 70], one in Cajamarca (Northern Peru) [71], and the remaining study tested samples from 4 Peruvian regions, including Lima [52]. As with E. coli of other origins, the number and type of antibiotics tested varied among the different studies, with AMR data of a total of 22 different antibacterial agents (Table 6).

Table 6.

Percentage of antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli from pets.

| Articles |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | |

| Sample | V | Dog | Dog | Dog | Dog |

| No | 526 | 12 | 14b | 45c | 100 |

| Year | <2009 | ? | 2003–2012 | 2012–2017 | 2016–2017 |

| Antimicrobial Resistance (%) | |||||

| Amp | 13.5 | 91.7 | 53 | ||

| Amx | 75.0 | ||||

| Pen | 100.0 | ||||

| A/C | 25.0 | 46.0 | 52.6 | ||

| Kf | 91.7 | ||||

| Cfx | 91.7 | 50.0 | 47.0 | ||

| Fox | 41.7d | ||||

| Cro | 0.9 | 33.3d | 45.2 | ||

| Imp | 8.3d | ||||

| Oxt | 75.0 | 75.0 | |||

| Dox | 58.3 | 70.6 | |||

| Tc | 33.0 | ||||

| Sxt | 9.1 | 25.0d | 75.0 | 63.4 | 41.0 |

| Chl | 33.3d | 78.6 | |||

| S | 61.0 | ||||

| Nal | 91.7 | ||||

| Cip | 1.7 | 33.3 | 60.0 | 51.3 | |

| Enr | 41.7 | 46.0 | 77.5 | 10.0 | |

| Ak | 0.0 | 20.6 | |||

| Gm | 25.0 | 33.0 | 63.6 | 40.0 | |

| Tob | 29.0 | ||||

| Nit | 70.0 | ||||

V: various; Year: sampling year; Amp: Ampicillin; Amx: Amoxicillin; Pen: Penicillin; A/C: Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid; Atm: Aztreonam; Kf: cefalotin; Cfx: cefalexin; Fox: Cefoxitin; Cro: Ceftriaxone; Imp: Imipenem; Oxt: Oxytetracycline; Dox: Doxycycline; Tc: Tetracycline; Sxt: Cotrimoxazole; Chl: Chloramphenicol; S: Streptomycin; Nal: Nalidixic acid; Cip: Ciprofloxacin; Enr: Enrofloxacin; Ak: Amikacin; Gm: Gentamicin; Tob: Tobramycin; Nit: Nitrofurantoin. a The sampling included: 224 dogs, 95 cats, 77 guinea pigs, 72 pigs, 64 ducks, 34 cows, 30 rabbits, 27 sheep, 23 turkeys, 15 donkeys, 12 doves, 12 goats, 8 horses, 8 canaries/parrots, 2 geese, 2 monkeys, 1 quail, 1 squirrel, 1 unknown. Note that in Peru guinea pig is considered a food-producing animal, not a pet. Data were classified in the pet category because of the high percentage of dogs (31.7%) and cats (13.4%). In the article, data of resistance were not disaggregated by species [52]. b The number of isolates analyzed for each antimicrobial differed, varying from 6 isolates in the case of gentamicin to 13 for amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid and enrofloxacin. c The number of isolates analyzed for each antimicrobial differed, varying from 12 isolates in the case of nalidixic acid and oxytetracycline to 40 for enrofloxacin. d All intermediate.

Four of the studies reported high levels of AMR [43, 69, 70, 71], with the remaining study of samples collected prior to 2009, described 13.5% of resistance to ampicillin as the highest value [52]. Intermediate isolates were especially frequent in the study by Vega et al [69], with no specific reason to explain this difference, other than the above-commented possible misuse of antibacterial agents or higher exposure to environmental pollution. In this regard is of note that Vega et al. reported E. coli isolates recovered from dog samples collected in shelters (therefore not living in a household as a personal pet) in periurban areas of Lima [69], including areas with deficient access to drinking water (https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1411/cap01_01.pdf).

Neither susceptibility to ceftazidime, cefotaxime or cefepime, nor data about ESBLs or pAmpC was available. Nevertheless, 2 of the studies described levels of intermediate or resistance of 33.3% and 45.2% to cefotaxime [69, 70], suggesting the presence of these enzymes.

Excluding the article of Kalter et al. [52], in general, the levels of resistance detected ranged from 25% to 91.7%. Thus, as described in E. coli from other sources, resistance to quinolones was high, with a maximum of 91.7% of nalidixic acid resistance reported by García et al [70]. Along the same line, levels of resistance of up to 75% to tetracyclines (oxytetracycline) or between 50% and 100% for ancient penicillins and first-generation cephalosporins were reported. The most noticeable exception was the presence of 0% of resistance to amikacin observed by Lujan-Roca et al. [43], and 8.3% of non-susceptibility to imipenem (all isolates were intermediate) described by Vega et al [69]. These data agree with those related to environmental E. coli.

3.7. Escherichia coli recovered from wild Animals

Only 3 studies, one in Lima and the other two in the jungle area of Peru, reported data of susceptibility to antimicrobial agents in E. coli from wild animals [72, 73, 74] (Table 7).

Table 7.

Percentage of antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli from wild animals.

| Articles |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | 29 | 30 | |

| Sample | NC | SC | M |

| No | 17 | 7 | 45 |

| Year | 2014 | 2014 | ? |

| Antimicrobial Resistance | |||

| Amp | 28.6 | ||

| A/C | 26.7 | ||

| SAM | 8.0 | ||

| Atm | 28.6 | ||

| Kf | 62.2 | ||

| Cxm | 46.7 | ||

| Fox | 0.0 | ||

| Oxa | 53.3 | ||

| Cro | 40.0 | 6.6 | |

| Tc | 60.0 | 46.7 | |

| Sxt | 20.0a | 15.5 | |

| Chl | 100.0 | 28.9 | |

| S | 6.7a | ||

| Nal | 60.0 | 14.3 | |

| Cip | 6.7a | 0.0 | |

| Enr | 13.3a | 28.9 | |

| Ak | 20.0 | ||

| Gm | 6.7 | 0.0 | |

| Nm | 46.7 | ||

| Tob | 40.0 | ||

| Nit | 26.7 | ||

Year: sampling year; Callicebus spp., and Lagothrix spp.); Amp: Ampicillin; A/C: Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid; Atm: Aztreonam; Kf: cefalotin; Cxm: Cefuroxime; Fox: Cefoxitin; Oxa: Oxacillin; Cro: Ceftriaxone; Tc: Tetracycline; Sxt: Cotrimoxazole; Chl: Chloramphenicol; S: Streptomycin; Nal: Nalidixic acid; Cip: Ciprofloxacin; Enr: Enrofloxacin; Ak: Amikacin; Gm: Gentamicin; Nm: Neomycin; Tob: Tobramycin; Nit: Nitrofurantoin. a Mostly intermediate.

Of note, while classified as “wild”, only one study involved free-ranging animals (Caiman cocodrilus) [73], while another 2 studies analyzed samples from animals living in captivity or semi-captivity [72, 74]. Another study, including bats (Desmodus rotundus) was not considered because of the presence of selective bias [65].

In a few cases, AMR levels >60% were detected, with nalidixic acid and tetracycline reaching this level in samples collected from Northern Caimans living in semi-captivity in San Juan del Lurigancho [72]. In addition, as in other cases, resistance levels to antimicrobial agents such as ancient β-lactam agents or several aminoglycosides were also high. Of note the study by Castañón also detected a high number of intermediate isolates, in agreement with the results of Vega et al. in shelter dogs in the same area [69], supporting the presence of local specificity favoring the natural selection of E. coli presenting low levels of AMR.

Despite the differences inherent to sampling species, the limited number of studies, and the difficulty in comparing studies using different antimicrobial agents, overall, the results suggest higher levels of resistance in animals living in captivity than in those in free-ranging conditions. The most notorious exception was chloramphenicol, with 100% of resistance in free-ranging C. cocodrilus, and no clear reason for this finding [73].

None of the 3 studies analyzed the presence of ESBLs or other specific AMR determinants. Nevertheless, in a study using selective media for the detection of ESBL-carrying E. coli, Benavides et al. [65], detected the presence of blaCTX-M-15 in E. coli recovered from fecal swabs from bats, showing that the spread of ESBLs in Peru has extended to free-ranging animals.

3.8. Limitations

Among the limitations of the present analysis two are of special relevance: the lack of uniformity and the outdating of most of the samples analyzed. Thus, the lack of uniformity in reporting data inherent to the different origins of the studies makes data comparison difficult. In addition, several reports included isolates obtained more than 20 years ago and were, thus, outdated with respect to the inferred current situation. The later finding highlights the scarcity of recent data in Peru, being especially notable among human commensal E. coli, and the need to perform new AMR surveillances to provide at least of a partial vision of the current AMR panorama. These data are of special relevance in the current scenario of the COVID-19 pandemic, in which the use of antimicrobial agents has incremented worldwide in both hospital and community settings, especially in countries with over-the-counter access to antimicrobial agents, such as Peru, leading to higher selective pressure towards increasing AMR levels [21, 117, 118].

4. Conclusion

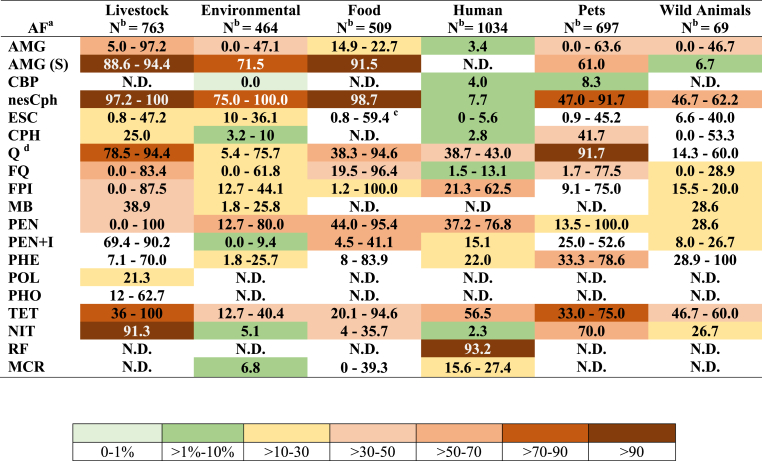

The levels of AMR reported in Peru between 2009 and 2019 are of concern, especially regarding ancient antibacterial agents such as streptomycin, 1st and 2nd generation cephalosporins, tetracyclines or first-generation quinolones (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overall data of antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli (2009–2019). AF: Antimicrobial agents' families; N: Number; AMG: Aminoglycosides (amikacin. gentamicin, kanamycin neomycin, tobramycin) excepting streptomycin; AMG (S): Aminoglycosides (only streptomycin); CBP: Carbapenems (ertapenem, imipenem, meropenem); nesCph: non extended-spectrum cephalosporins (cefazolin, cefalotin; cefalexin; cefuroxime); ESC: Extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ceftazidime, cefotaxime, cefepime, ceftriaxone); CPH: Cefamicins (cefoxitin, oxacillin); Q/FQ: Quinolones (nalidixic acid) and Fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, enrofloxacin); FPI: Folate pathway inhibitors (cotrimoxazole, sulfamethoxazole); MB: Monobactams (aztreonam); PEN: Penicillins (ampicillin, amoxicillin); PEN + I: Penicillins plus inhibitors of β-Lactamases (amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid, sulperazone); PHE: Phenicols (chloramphenicol, florfenicol); POL: Polymyxins (colistin); PHO: Phosphonic acids (fosfomycin); TET: Tetracyclines (tetracycline, doxycycline, oxytetracycline); NIT: Nitrofurans (furazolidone; nitrofurantoin); RF: Rifamycins (rifaximin); MCR: Macrolides (azithromycin); N.D.: No data. The numbers represent the minimum and the maximum percentage of resistance to any of the tested antibacterial agents belonging to each family. The mean values of resistance are represented by colors; to establish this value the maximum mean value of any of the antimicrobial agents belonging to a specific family was considered. Note that these approaches result in a sub estimation of the real levels of resistance to antibacterial agent families. a Following the classification of Magiorakos et al [119]. Families not considered by Magiorakos et al. were reported following standard schemes. b Overall number of isolates included in each group. Note that not all isolates were tested for all antimicrobial agents. c Maximum value inferred from prevalence of ESBL reported by Ruiz-Roldán et al. [47]. d Resistance to quinolones is a risk factor for the development of resistance and therapeutic failure when using fluoroquinolones [97].

The high levels of AMR and the detection of relevant resistance levels to other agents such as 3rd and 4th generation cephalosporins or fluoroquinolones, as well as the detected resistance to polymyxins (although only data from livestock samples were available) suggests the need to implement effective controls regarding access to antibacterial agents as well as the development of educational campaigns to increase population awareness of the relevance of prudent use of antibacterial agents and the risks derived from an abusive use.

The unusual number of E. coli isolates presenting intermediate levels of resistance to a series of unrelated agents strongly suggests the presence of an atypical scenario in which factors such as heavy metals or chemical pollutants might play a role in the constitutive overexpression of efflux pumps.

Finally, the data available were scarce, partially outdated and, in several cases, difficult to access, alerting to the need to perform new and extensive surveillance to dispose of a real current scenario leading to more efficient use of antibacterial agents.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This study was supported by Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico, Tecnológico y de Innovación Tecnológica (FONDECYT - Perú) and Universidad Científica del Sur within the “Proyecto de Mejoramiento y Ampliación de los Servicios del Sistema Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Tecnológica” [contract: 08-2019-FONDECYT-BM-INC-INV"]. This study has been performed within the frame of the net P220RT0168 from Programa Iberoamericano de Ciencia y Tecnología para el Desarrollo (CYTED).

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Donna Pringle for language correction.

Contributor Information

Joaquim Ruiz, Email: joruiz.trabajo@gmail.com.

Maria J. Pons, Email: ma.pons.cas@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Duchesne E. Antagonisme entre les moisissures et le microbes. [PhD Thesis] Faculté de Médecine et de Pharmacie de Lyon; Lyon (France): 1897. Contribution à l’etude de la concurrence vitale chez les microorganismes. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Domagk G. Ein beitrag zur chemotherapie der bakteriellen infektionen. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 1935;61:250–253. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emmerich R., Löw O. Bakteriolytische enzyme als ursache der erworbenen immunität und die heilung von infectionskrankheiten durch dieselben. Z. Hyg. Infektionskr. 1899;31:1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming A. On the antibacterial action of cultures of a Penicillium, with special reference to their use in the Isolation of B. influenzae. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1929;10:226–236. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiberio V. Sugli estratti di alcune muffe. An Ig Sper. 1895;5:91–103. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Florey M.E., Adelaide M.B., Florey H.W., Adelaide M.B. General and local administration of penicillin. Lancet. 1943;241:387–397. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrova M., Gorlenko Z., Mindlin S. Tn5045, a novel integron-containing antibiotic and chromate resistance transposon isolated from a permafrost bacterium. Res. Microbiol. 2011;162:337. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz J. Transferable mechanisms of quinolone resistance from 1998 onward. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019;32:e00007–e00019. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00007-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.San Millan A., MacLean R.C. Fitness costs of plasmids: a limit to plasmid transmission. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017;5:5. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.mtbp-0016-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Man TJB, Lutgring J.D., Lonsway D.R., Anderson K.F., Kiehlbauch J.A., Chen L., et al. Genomic analysis of a pan-resistant isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae, United States 2016. mBio. 2018;9:e00440. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00440-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karakonstantis S., Gikas A., Astrinaki E., Kritsotakis E.I. Excess mortality due to pandrug-resistant infections in hospitalized patients. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020;106:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliva A., Ceccarelli G., De Angelis M., Sacco F., Miele M.C., Mastroianni C.M., et al. Cefiderocol for compassionate use in the treatment of complicated infections caused by extensively and pan-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;23:292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pons M.J., Ruiz J. Current trends in epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance in Intensive Care Units. J. Emerg. Crit. Care Med. 2019;3:5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Center for Diseases Control and Prevention . US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; Atlanta: 2019. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neill O.’. Antimicrobial resistance: Tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. London: HM Government/Wellcome Trust; 2014. Review on antimicrobial resistance.https://amrreview.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20-%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Bank Group . International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; Washington DC, USA: 2017. Drug-resistant Infections. A Threat to Our Economic Future. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okeke I.N., Klugman K.P., Bhutta Z.A., Duse A.G., Jenkins P., O'Brien T.F., et al. Antimicrobial resistance in developing countries. Part II: strategies for containment. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2005;5:568–580. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sosa A.J., Byarugaba D.K., Amabile C., Hsueh P.R., Kariuki S., Okeke I.N., editors. Antimicrobial Resistance in Developing Countries. Springer; New York, USA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vila J., Pal T. Update on antibacterial resistance in low-income countries: factors favoring the emergence of resistance. Open Infect Dis. 2010;4:38–54. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zavala-Flores E., Salcedo-Matienzo J. Medicación prehospitalaria en pacientes hospitalizados por COVID-19 en un hospital público de Lima-Perú. Acta Méd. Peru. 2020;37:393–395. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Endtz H.P., Ruijs G.J., van Klingeren B., Jansen W.H., van der Reyden T., Mouton R.P. Quinolone resistance in Campylobacter isolated from man and poultry following the introduction of fluoroquinolones in veterinary medicine. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1991;27:199–208. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiz J. Reflexión acerca del concepto de «Una Salud. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Pública. 2018;35:657–662. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2018.354.3821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarmah A.K., Meyer M.T., Boxall A.B. A global perspective on the use, sales, exposure pathways, occurrence, fate and effects of veterinary antibiotics (VAs) in the environment. Chemosphere. 2006;65:725–759. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartoloni A., Pallecchi L., Riccobono E., Mantella A., Magnelli D., Di Maggio T., et al. Relentless increase of resistance to fluoroquinolones and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins in Escherichia coli: 20 years of surveillance in resource-limited settings from Latin America. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013;19:356–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flores-Paredes W., Luque N., Albornoz R., Rojas N., Espinoza M., Pons M.J., et al. Evolution of antimicrobial resistance levels of ESKAPE microorganisms in a Peruvian IV-level hospital. Infect Chemother. 2021;53:449–462. doi: 10.3947/ic.2021.0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Labarca J.A., Salles M.J., Seas C., Guzmán-Blanco M. Carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii in the nosocomial setting in Latin America. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;42:276–292. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2014.940494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pallecchi L., Riccobono E., Mantella A., Fernandez C., Bartalesi F., Rodriguez H., et al. Small qnrB-harbouring ColE-like plasmids widespread in commensal enterobacteria from a remote Amazonas population not exposed to antibiotics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011;66:1176–1178. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sati H.F., Bruinsma N., Galas M., Hsieh J., Sanhueza A., Ramon Pardo P., et al. Characterizing Shigella species distribution and antimicrobial susceptibility to ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid in Latin America between 2000-2015. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levy-Blitchtein S., Roca I., Plasencia-Rebata S., Vicente-Taboada W., Velásquez-Pomar J., Muñoz L., et al. Emergence and spread of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii international clones II and III in Lima, Peru. Emerg. Microb. Infect. 2018;7:119. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0127-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ecker L., Ruiz J., Vargas M., del Valle L.J., Ochoa T.J. Prevalencia de compra sin receta y recomendación de antibióticos para niños menores de 5 años en farmacias privadas de zonas peri-urbanas de Lima, Perú. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2016;33:215–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernando-Amado S., Coque T.M., Baquero F., Martínez J.L. Defining and combating antibiotic resistance from one health and global health perspectives. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:1432–1442. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0503-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amabile-Cuevas C.F. Antibiotic resistance from, and to the environment. AIMS Environ Sci. 2021;8:18–35. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Penders J., Stobberingh E.E., Savelkoul P.H., Wolffs P.F. The human microbiome as a reservoir of antimicrobial resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2013;4:87. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanz-García F., Gil-Gil T., Laborda P., Ochoa-Sánchez L.E., Martínez J.L., Hernando-Amado S. Coming from the wild: multidrug resistant opportunistic pathogens presenting a primary, not human-linked, environmental habitat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:8080. doi: 10.3390/ijms22158080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fleece M.E., Pholwat S., Mathers A.J., Houpt E.R. Molecular diagnosis of antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2018;18:207–217. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2018.1439381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mandomando I., Vubil D., Boisen N., Quintó L., Ruiz J., Sigaúque B., et al. Escherichia coli ST131 clones harbouring AggR and AAF/V fimbriae causing bacteremia in Mozambican children: emergence of new variant of fimH27 subclone. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2020;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murillo O., Grau I., Lora-Tamayo J., Gomez-Junyent J., Ribera A., Tubau F., et al. The changing epidemiology of bacteraemic osteoarticular infections in the early 21st century. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015;21:254.e1–254.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ormeño MA, Ormeño MJ, Quispe AM, Arias-Linares MA, Linares E, Loza F, et al. Recurrence of Urinary Tract Infections Due to Escherichia coli and its Association with Antimicrobial Resistance Microb Drug Resist. in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Ruiz J., Mensa L., O'Callaghan C., Pons M.J., González A., Vila J., et al. In vitro antimicrobial activity of rifaximin against enteropathogens causing traveler's diarrhea. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007;59:473–475. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teweldemedhin M., Gebreyesus H., Atsbaha A.H., Asgedom S.W., Saravanan M. Bacterial profile of ocular infections: a systematic review. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17:212. doi: 10.1186/s12886-017-0612-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vila J., Sáez-López E., Johnson J.R., Römling U., Dobrindt U., Cantón R., et al. Escherichia coli: an old friend with new tidings. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2016;40:437–463. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuw005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luján-Roca D.A., Saavedra-Espinoa I., Luján-Roca L.M. Antibiotic resistance of pathogenic bacteria isolated from dogs at a veterinary clinic in Callao, Peru. Rev Electron Vet. 2017;18:9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luna L., Maturrano L., Rivera H., Zanabria V., Rosadio R. Genotipificación, evaluación toxigénica in vitro y sensibilidad a antibióticos de cepas de Escherichia coli aisladas de casos diarreicos y fatales en alpacas neonatas. Rev Inv Vet Perú. 2012;23:280–288. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luppi A. Swine enteric colibacillosis: diagnosis, therapy and antimicrobial resistance. Porcine Health Manag. 2017;3:16. doi: 10.1186/s40813-017-0063-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rivera F.P., Sotelo E., Morales I., Menacho F., Medina A.M., Evaristo R., et al. Detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) in healthy cattle and pigs in Lima, Peru. J. Dairy Sci. 2012;95:1166–1169. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruiz-Roldán L., Martínez-Puchol S., Gomes C., Palma N., Riveros M., Ocampo K., et al. Presencia de Enterobacteriaceae y Escherichia coli multirresistente a antimicrobianos en carne adquirida en mercados tradicionales en Lima. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Pública. 2018;35:425–432. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2018.353.3737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van den Bogaard A.E., Stobberingh E.E. Epidemiology of resistance to antibiotics. Links between animals and humans. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2000;14:327–335. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mosquito S.G., Ruiz J., Pons M.J., Barletta F., Durand D., Ochoa T.J. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli isolated from children. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2012;40:544–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bartoloni A., Pallecchi L., Rodríguez H., Fernandez C., Mantella A., Bartalesi F., et al. Antibiotic resistance in a very remote Amazonas community. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2009;33:125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pallecchi L., Riccobono E., Mantella A., Bartalesi F., Sennati S., Gamboa H., et al. High prevalence of qnr genes in commensal enterobacteria from healthy children in Peru and Bolivia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2632–2635. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01722-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kalter H.D., Gilman R.H., Moulton L.H., Cullotta A.R., Cabrera L., Velapatiño B. Risk factors for antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli carriage in young children in Peru: community-based cross-sectional prevalence study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010;82:879–888. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alzamora M.C., Echevarría A.C., Ferraro V.M., Riveros M.D., Zambruni M., Ochoa T.J. Resistencia antimicrobiana de cepas comensales de Escherichia coli en niños de dos comunidades rurales peruanas. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Pública. 2019;36:459–463. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2019.363.4366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flores-Caldas C.A. Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos; Lima (Peru): 2017. Resistencia antibacteriana en cepas de Escherichia coli aisladas del proceso de beneficio bovino en Lima Metropolitana. [BsC Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sulca López M.A., Alvarado Iparraguirre D.E. Asociación de la resistencia al mercurio con la resistencia a antibióticos en Escherichia coli aislados del litoral de Lima. Perú. Rev Peru Biol. 2018;25:445–452. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rivera-Jacinto M.A. Betalactamasas de espectro extendido en cepas de Escherichia coli y Klebsiella sp. aisladas de reservorios inanimados en un hospital del norte del Perú. Rev. Española Quimioter. 2012;25:161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loyola S., Gutierrez L.R., Horna G., Petersen K., Agapito J., Osada J., et al. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in cell phones of health care workers from Peruvian pediatric and neonatal intensive care units. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2016;44:910–916. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Larson A., Hartinger S.M., Riveros M., Salmon-Mulanovich G., Hattendorf J., Verastegui H., et al. Antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli in drinking water samples from rural Andean households in Cajamarca, Peru. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019;100:1363–1368. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alejos Tapia I.G. Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia; Lima (Peu): 2017. Caracterización de la susceptibilidad a antibióticos betalactámicos de espectro extendido, ciprofloxacina y cotrimoxazol de cepas de Escherichia coli aisladas de zonas de amortiguamiento cercanas a crianza de Argopecten purpuratus (conchas de abanico) en seis puntos de la bahía de Sechura, Piura. [BsC Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sánchez Pariona C.Z. Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia; Lima (Peru): 2018. Detección molecular y fenotípica de resistencia antimicrobiana de Escherichia coli aislada de agua de mar utilizada en el expendio de productos hidrobiológicos en los terminales pesqueros de Ancón y Chorrillos. [MsC Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Palacios Farias S.E. Universidad Nacional de Piura; Piura (Peru): 2019. Frecuencia de Escherichia coli resistente a antibióticos aisladas del agua del rio Piura, Perú en un tramo de la ciudad. [BsC Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Monterroso M., Salvatierra G., Sedano A., Calle S. Detección fenotípica de mecanismos de resistencia antimicrobiana de Escherichia coli aisladas de infecciones entéricas de porcinos provenientes de granjas de producción tecnificada. Rev Inv Vet Perú. 2019;30:455–464. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Toledo E., Falcon N., Flores C., Rebatta M., Guevara J., Ramos D. Susceptibilidad antimicrobiana de cepas de Escherichia coli obtenidas de muestras de heces de cerdos destinados a consumo humano. Salud Tecnol Vet. 2015;3:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barrios-Arpi M., Morales S., Villacaqui-Ayllon E. Susceptibilidad antibiótica de cepas de Escherichia coli en crías de alpaca con y sin diarrea. Rev Inv Vet Perú. 2016;27:381–387. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Benavides J.A., Shiva C., Virhuez M., Tello C., Appelgren A., Vendrell J., et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in common vampire bats Desmodus rotundus and livestock in Peru. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:454–458. doi: 10.1111/zph.12456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ceino Gordillo F., Koga Yanagui I., Peña Murillo N. Detección fenotípica y genotípica de Escherichia coli productoras de β-lactamasas espectro extendido aisladas de aves de abasto en Perú. Biotempo. 2019;16:181–186. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vilchez Chiara F.E. Universidad Nacional de Trujillo; Trujillo (Peru): 2019. Aislamiento, identificación y evaluación de la resistencia antimicrobiana de Escherichia coli en pollos de engorde. Piura. [MsC Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chavez Diaz S.K. Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca; 2018. Resistencia de Escherichia coli a antibióticos mediante la prueba de disco difusión en terneros de Tartar Grande–Baños del Inca–Cajamarca, 2018 [BsC Thesis]. Cajamarca (Peru) [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vega H., Fernández V., Morales S., Calle S., Pérez C. Determinación de la susceptibilidad antibiótica in vitro de bacterias subgingivales en caninos con enfermedad periodontal moderada a severa. Rev Inv Vet Perú. 2014;25:77–87. [Google Scholar]

- 70.García M., Díaz D., Huerta C., Olazábal J., Barrios-Arpi M., Chipayo Y. Análisis retrospectivo de agentes bacterianos y patrones de susceptibilidad antibiótica en casos de infecciones del tracto urinario en caninos domésticos (2012-2017) Rev Inv Vet Perú. 2019;30:1837–1844. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gamarra Ramirez R.G. Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca; 2018. Resistencia antibacteriana de Escherichia coli y su relación con factores asociados en perros mascota en Cajamarca. [MsC Thesis]. Cajamarca (Peru) [Google Scholar]

- 72.Castañón Anaya J.C. Universidad Científica del Sur; Lima (Peru): 2018. Determinación de la resistencia antibiótica de cepas de enterobacterias aisladas de la cavidad oral del lagarto caimán (Dracaena guianensis) en Lima, Perú [BsC Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carlos-Erazo N., Núñez del Prado-Reyes Y., Gonzales-Oré V.H., Capuñay-Becerra C. Enterobacterias y su resistencia antimicrobiana en el caimán blanco (Caiman crocodilus) de vida libre en el río Madre de Dios, Tambopata–Perú. Rev Latinoam Recur Nat. 2016;12:53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Medina C., Morales S., Navarrete M. Resistencia antibiótica de Enterobacterias aisladas de monos (Ateles, Callicebus y Lagothrix) en semicautiverio en un centro de rescate. Perú. Rev Inv Vet Perú. 2017;28:418–425. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gomes C., Ruiz L., Pons M.J., Ochoa T.J., Ruiz J. Relevant role of efflux pumps in the high levels of rifaximin resistance in Escherichia coli clinical isolates. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013;107:545–549. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trt059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gomes C., Ruiz-Roldán L., Mateu J., Ochoa T.J., Ruiz J. Azithromycin resistance levels and mechanisms in Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:6089. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42423-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pons M.J., Mosquito S.G., Gomes C., del Valle L.J., Ochoa T.J., Ruiz J. Analysis of quinolone-resistance in commensal and diarrheagenic Escherichia coli isolates from infants in Lima, Peru. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014;108:22–28. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trt106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]