Highlights

-

•

The COVID-19 pandemic has magnified already worrying levels of loneliness in Europe.

-

•

Young adults have been the most severely hit by social distancing measures.

-

•

Living alone has made social distancing measures more painful.

Keywords: Loneliness, COVID-19 pandemic, Risk-factors, Europe

Abstract

Objective

The purpose of the study is to examine the prevalence of loneliness in Europe in 2016 and during the first months – April-July 2020 – of the COVID-19 pandemic, and to assess whether the risk factors associated with loneliness have changed after the outbreak of the pandemic.

Method

The analysis is based on two cross-country surveys, namely the 2016 European Quality of Life Survey and the 2020 Living, Working and COVID-19 Online Survey.

Results

The COVID-19 pandemic has magnified already worrying levels of loneliness in Europe. Young adults have been the most severely hit by social distancing measures. Living alone has made social distancing measures more painful. Health and financial status are strong associates of loneliness, irrespective of the time period.

Conclusion

This analysis will help anticipate the potential consequences that forced social isolation might have triggered in the population and identify populations more vulnerable to loneliness. Further monitoring is important to assess whether the registered increase in loneliness is transient or chronic and to design targeted loneliness interventions.

1. Introduction

A series of studies compares loneliness to obesity and smoking in the mortality risks that it entails [[1], [2], [3]]. There is evidence that loneliness is associated with physical and psychological health problems [4]. Lonely adults tend to suffer from higher levels of cortisol (the ‘stress hormone’), raised blood pressure, impaired sleep, and cardiovascular resistance compared to non-lonely individuals [5,2]. Over time, this translates into chronic inflammation and higher morbidity and mortality rates. Loneliness is also associated with depressive symptoms and unhealthy behaviours [[6], [7]].

Against this background, loneliness is increasingly recognized as an important public health issue. In 2018 the United Kingdom government established a ministerial-rank figure to coordinate a loneliness reduction strategy. In the Netherlands, the Directorate of Long-Term Care of the Ministry of Health has been allocating considerable financial and human resources to combat loneliness [8]. In 2021, the Japanese government appointed a minister to combat loneliness and alleviate social isolation [9]. Contextually, the attention dedicated to the issue by media worldwide magnified the salience of loneliness in the public sphere (see, e.g. [10,11]).

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization first called COVID-19 a pandemic. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, lockdowns, curfews, distancing measures as well as the cancellation of community activities and events have been implemented across Europe. Whilst these measures were needed to control the spread of the virus, they also engendered forms of social isolation unprecedented in living generations, with potential long-term effects on mental health, including an increase in loneliness.

Monitoring which populations are vulnerable to loneliness is important to design targeted and effective intervention strategies. This paper contributes to this monitoring by using European survey data and comparing the incidence of loneliness in 2016 and during the first months – April-July 2020 – of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, it examines whether the risk factors associated with loneliness have changed after the outbreak of the pandemic.

Apart from Varga et al. [12] and Bonsaksen et al. [13], which both cover 4 countries, the recent literature dedicated to the risk factors of loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic [[14], [15], [16], [17], [18]] is based on data from a single country. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first study which includes the 27 countries from the European Union.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 defines loneliness and presents the data used in the empirical analysis. Section 3 maps out loneliness prevalence in EU Member States before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Section 4 examines the risk factors of loneliness and tests if some groups show a greater vulnerability to social distancing measures. Section 5 reviews the limitations of the empirical analysis and concludes.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

In this study, we rely on two data sources (i) the 2016 European Quality of Life Survey (EQLS) and (ii) the Living, working and COVID-19 e-survey (LWC).

The 2016 EQLS survey is the fourth edition of a cross-national survey based on a stratified random sampling design and face-to-face interviews, taking place between September 2016 and March 2017. The EQLS data cover all EU Member States, the United Kingdom and five EU candidate countries, with sample sizes between 1000 and 2000 people per country. The target population includes all people aged above 18 and residing in private households.

The LWC survey is drawn from an online survey launched in the days following the COVID-19 outbreak in Europe by Eurofound. The first round of the fieldwork took place between 9 April and 27 July 2020. The survey was carried out online, open to anybody aged 18 and above. The recruitment of the participants was insured through snowball sampling methods as well as with advertisements on social media networks. Therefore, the LWC sample size varies substantially across countries. More than 5,000 observations were collected in Croatia, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Portugal, Romania or Spain but less than 1,000 respondents filled in the survey in Luxembourg.

A note of caution is in order before moving on. The characteristics of respondents participating, respectively in the EQLS and LWC might differ as the two surveys are based on different survey modes. We partially control for this by using post stratification weights. These weights account for country population size and the demographic characteristics of the target population. This ensures that the weighted statistics for both surveys are similar along the dimensions used to derive the weights (see Table A2 in Appendix Supplementart materials).

2.2. Measuring loneliness

While social isolation has an objective connotation, loneliness is a subjective feeling of discrepancy between the actual and desired level of meaningful social connections [[19], [20]]. Loneliness is thus not necessarily about having too few social contacts per se, but about the perception that these relationships are not satisfying enough [[20], [21], [22]].

Both the EQLS and LWC surveys collect information on loneliness and other well-being indicators, as well as detailed information on the socio-economic status of the respondents [23,24]. The wording of the question on loneliness is the following: “[…] please tell me how much of the time during the last two weeks you felt lonely?” with the possible answers being “All of the time”, “Most of the time”, “More than half of the time” “Less than half of the time”, “Some of the time” and “At no time”. We consider respondents reporting to have felt lonely “All of the time”, “Most of the time”, “More than half of the time” as frequently lonely.

2.3. Analysis

To examine the risk and protective factors of loneliness, we fit two nonlinear regression models (logit), one for each time period (i.e. 2016 and 2020). This allows us to study whether the risk factors associated with loneliness have changed following the pandemic outbreak. The dependant variable in each regression model is a binary indicator equal to one if the respondent reports to be frequently lonely and zero otherwise. The explanatory variables, capturing the socio-economic, demographic and household characteristics of the respondent, include gender, age and health status, household type (presence of children, marital status), educational level, labour market status, financial situation, and living area (rural/urban). Country fixed effects are included in each regression model. Table A.1 (see Appendix Supplementart materials) describes the explanatory variables in more detail.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

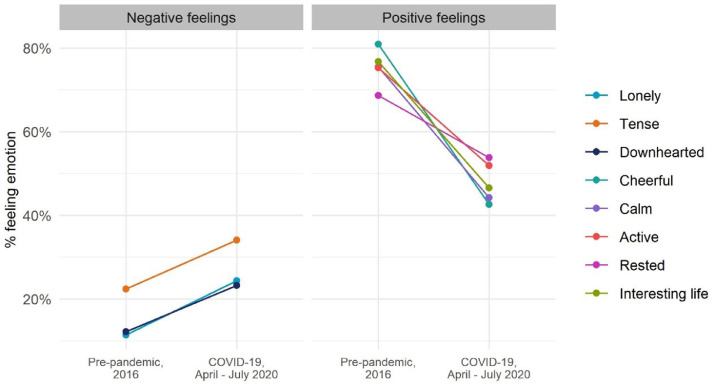

Fig. 1 compares the prevalence of loneliness and well-being in Europe in the pre-pandemic period, as well as during the first months following the COVID-19 outbreak. Loneliness prevalence rose sharply in the first months following the outbreak. In 2016, around 12% of EU citizens reported feeling frequently lonely whereas, during the pandemic, this share amounted to 25%. Mental wellbeing deteriorated as well. Negative emotions such as feeling tense or downhearted also increased. At the same time, the share of EU citizens having positive emotions, like feeling cheerful, calm, active or rested, “more than half of the time” dropped from 70 to 80% of people to around 50%.

Fig. 1.

Mental well-being before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data sources: Eurofound, 2016 EQLS and 2020 LWC surveys. Lonely, tense and downhearted measure the share of respondents who, over the two weeks preceding the interview, felt more than half of the time, respectively lonely, particularly tense and downhearted/depressed. Cheerful, calm, active, rested, and interesting life are 5 indicators indicating the share of respondents who, over the two weeks preceding the interview, felt more than half of the time, respectively: cheerful and in good spirits, calm and relaxed, active and vigorous, fresh and rested, and that their daily life is filled with interesting things. These items are inputs to the world health organisation's WHO-5 mental wellbeing index.

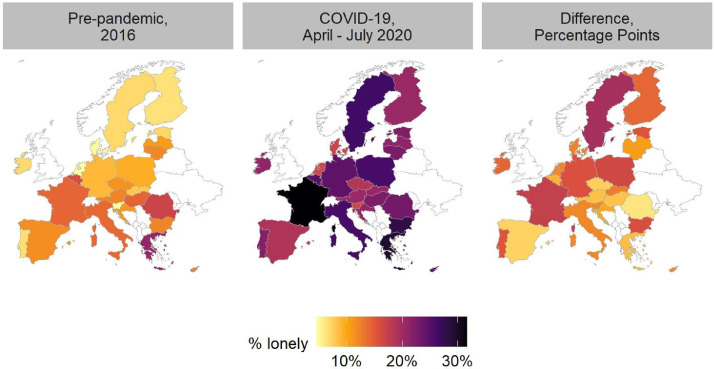

Loneliness was lowest in the pre-pandemic period in Northern Europe. The regional pattern observed before the pandemic with the European Quality of Life Survey is similar to the one found in other existing cross-national studies [[25], [26], [27], [28]]. More specifically, the lowest shares of loneliness were observed in Denmark and the Netherlands with less than 5% of the population feeling lonely. In contrast, Greece exhibited higher loneliness prevalence, with almost 20% of the respondents indicating to feel lonely (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Loneliness in the EU. Data sources: Eurofound, 2016 EQLS and 2020 LWC surveys; The figure displays by country the share of individuals who felt lonely more than half of the time over the two weeks preceding the interview.

During the pandemic, loneliness increased by more than 15 percentage points in Bulgaria, Estonia, France, Germany, Poland, Portugal and Sweden. In contrast, Belgium, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Romania and Spain experienced an increase by less than 10 percentage points (Fig. 2). We note that the increase in loneliness was stronger for countries with lower levels of loneliness in the pre-pandemic period (see Figs. A.1 and A.2 in Appendix Supplementart materials).

These macro-regional and country-specific figures in the first months of the pandemic might be at first sight a bit surprising. First, during the first wave of the 2020 survey, Southern and Western European countries had imposed more stringent lockdowns than the rest of Europe. Sweden did not enforce a lockdown, whereas most countries in Northern and Eastern Europe put in place softer lockdowns when infection rates were still relatively low. Second, we would expect the effect of social distancing to be more severe in countries or macro regions where people are more tactile and family ties are strong [25]. This is not what we observe. A possible explanation might be that the pandemic also created a sense of belonging in several countries, at least during the first months of the pandemic. Back in March and April 2020, people in countries such as Italy, Spain or France applauded or sang every evening on their balcony to support medical workers. In addition, people in Southern and Eastern Europe tend to reside closer to their family of origin than in other European countries, often within the radius of movement allowed during lockdowns periods. Therefore, social distancing measures might have impacted less on family-related interactions in these countries.

3.2. Risk factors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

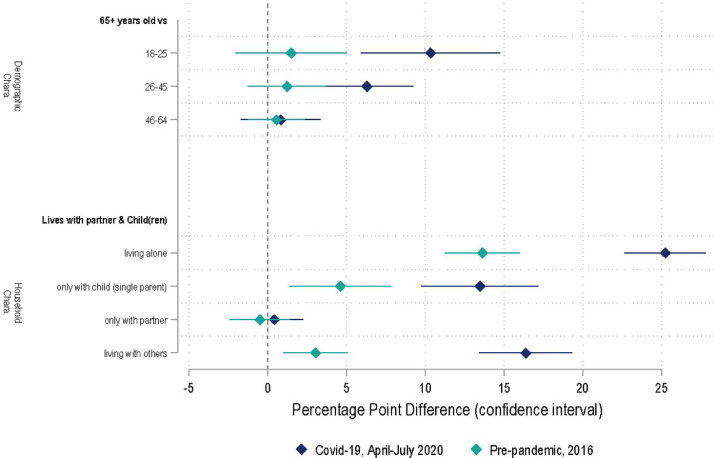

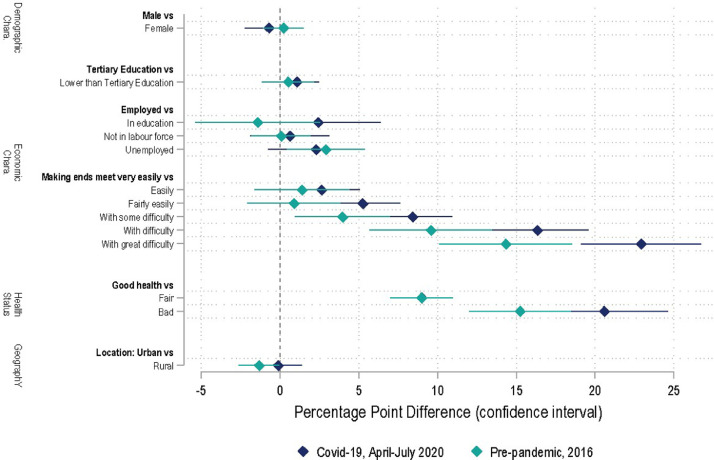

Fig. 3, Fig. 4 plot the marginal effects corresponding to the two regression models. For each variable of interest, the difference in loneliness compared to the reference group (in bold) is shown, along with the 95% confidence intervals. This allows a visual comparison of the pre-pandemic situation (in green) with the one observed during the first months of the pandemic (in blue). The marginal effects for both regression models are reported in Table A.3 (see Appendix Supplementart materials).

Fig. 3.

Factors associated with loneliness – what changed with the COVID-19 pandemic? Data sources: Eurofound, 2016 EQLS and 2020 LWC surveys. The graph displays the percentage-point differences in terms of loneliness between a person with the individual characteristics reported on the y-axis and their reference group reported in bold. Variables included in the model but not displayed in the graph are the labour market and economic characteristics of the respondent, their health status and their localization, (country of residence, rural or urban area). Confidence intervals at 95% level. See Table A.3 (supplementary material).

Fig. 4.

Factors associated with loneliness irrespective of the period. Data sources: Eurofound, 2016 EQLS and 2020 LWC surveys. The graph displays the percentage-point differences in terms of loneliness between a person with the individual characteristics reported on the y-axis and their reference group reported in bold. Variables included in the model but not displayed in the graph are the labour market and economic characteristics of the respondent, their health status and their localization, (country, rural or urban area). Confidence intervals at 95% level. See Table A.3 (supplementary material)..

3.2.1. What changed with the COVID-19 pandemic?

In the pre-pandemic survey, there were no noticeable differences in loneliness in the EU between age groups, after having accounted for the other characteristics of the population. This implies that differences in loneliness in the EU were mainly driven by the underlying characteristics of the various age groups (family arrangements, health status, income situation). However, during the pandemic, those aged 18-25 and 26-45 were 9- and 6-percentage points more likely to feel lonely than respondents aged 65 or more.

Loneliness is strongly linked to family arrangements. This was true both before and during the pandemic. Loneliness rose across all groups, but the gap between those who live alone and those living with a partner widened, when comparing 2016 and 2020. More specifically, during the first lockdown, loneliness among those living alone was 22 percentage points higher compared to respondents living with a partner and children. In comparison, in 2016, the corresponding gap amounted to 7 percentage points.

3.2.2. Some loneliness risk factors are not specifically linked to the pandemic context

Favourable economic conditions shield against loneliness. In 2016, individuals reporting that they found it very difficult, difficult or somewhat difficult to make ends meet were 14, 10 and 4 percentage points more likely to suffer from loneliness compared to those who made ends meet very easily. In 2020 these figures, respectively amounted to 23, 16 and 8 percentage points. However, we notice that the confidence intervals of several of these 2016 and 2020 corresponding point estimates overlap. The other proxies for the economic status - employment status or the educational level – are not statistically associated with loneliness once the household financial condition is accounted for.

Second, poor health is a critical risk factor for loneliness both in normal and exceptional times. In the pre-pandemic period, respondents indicating that they were in bad health were 15 percentage points more likely to feel frequently lonely. During the pandemic, the difference between the two groups of respondents increased to 21 percentage points. For both periods, respondents declaring to be in fair health were 9 percentage points more likely to feel lonely compared to the reference group. As for the economic status, the point estimates are not statistically different between the two time periods (confidence intervals overlap). Finally, there are no significant gender differences and no substantial urban-rural divide in self-reported loneliness both before and during the pandemic.

4. Discussion

Young adults were the most severely hit by the COVID-19 outbreak. This finding is in line with recent studies based on British or Canadian data [[14], [17]] and in contrast with the loneliness-age pattern reported in pre-COVID-19 times for Europe [[26], [28], [29], [30]]. This suggests that the increased family time and the use of digital communication modes during the pandemic have been less efficient in alleviating loneliness among young adults. At the same time, moving out of the family house, into a different city, region or country is possibly an isolating experience that, compounded with social distancing measures, could result in an emotional upheaval with long term impacts. Young adults are also likely more in need of in-person interactions. Indeed, in normal circumstances, the time spent with friends is highest among young adults whereas the amount of time alone increases with age [31]. It is therefore not surprising that young people suffered most. However, the level of distress that young people experienced during the pandemic might turn out to be transient.

Living arrangement is a critical factor of loneliness. This result is not new [[27], [32], [33]]. However, during the pandemic, living with someone has become more important to stave off loneliness. Other studies offer similar conclusions using British, Canadian and cross-country data from Australia, United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Norway [13,14,17]. Stay-at-home-order policies, school closures and social distancing measures hit particularly hard those with limited chances of in-person interactions within their household. Arguably, the use of digital tools during the pandemic to communicate with people living outside the household could not replace face-to-face communication, in line with Teo et al. [34].

We find that poor health and unfavourable economic conditions are critical loneliness risk factors, confirming previous literature [19,25,28,30,[35], [36], [37]]. Although the results seem to indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has heightened the association between loneliness and these two risk factors, the overlap of the confidence intervals suggests that the 2020 and 2016 point estimates are mostly not statistically different from each other. We also find that loneliness of individuals in poor health is mostly chronic, i.e. persistent over time, with no statistically significant variations between normal and exceptional circumstances. In this respect, it is important to underline that there might also be a reverse causality at play [2,5,6].

Females and males had, ceteris paribus, about the same likelihood of feeling lonely in the pre-pandemic period as at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. These observations resonate with the recent meta-study [38] reporting “a close-to-zero overall effect” of gender on loneliness in pre-covid times. Finally, the absence of a rural-urban divide coincides with several existing studies [28,39,40].

5. Conclusion

Social connections are critical in our daily lives. This paper examines how the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting limitations on social interactions have exacerbated loneliness in the EU. It brings insights on the significance of the problem for different demographic groups before and during the pandemic.

However, the study suffers from a number of limitations that are worth mentioning. First, the analysis relies on a cross-country design. Hence, we cannot establish causal relationships between loneliness and the risk factors discussed in this study. Longitudinal data would be needed to make causal inference. Second, the analysis does not cover the subsequent waves of the pandemic. Future research should investigate whether the patterns observed during the first outbreak have persisted. Third, loneliness is captured with a single item which explicitly mentions the term ‘lonely’, directly investigating people's subjective feeling. Indirect scales based on multiple indicators such as the ones developed by the University of California Loneliness Scale and the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale [[41], [42], [43]] are often preferred because of the multidimensional nature of loneliness and the fact that they tend to be less affected by cultural-based and country-sensitive differences in people's readiness to admit negative subjective experiences and personal concerns. Finally, as explained, the collection of the 2016 and 2020 data are based on different survey modes and frames. Notwithstanding the use of weighted statistics, there might remain other unobserved differences between the participants to the two surveys which cannot be accounted for. People participating in a voluntary online survey (during the COVID-19 outbreak) may be intrinsically different from those who have been randomly selected for a face-to-face interview. This is particularly likely for the elderly, less prone to use social media networks and/or online media. This suggests that the estimated prevalence of loneliness observed during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to be a lower bound estimate of the actual figure, particularly for the older age group.

From a public policy perspective, this is mostly chronic loneliness that requires interventions and appropriate health and social care policies. We might reasonably expect that loneliness induced by the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated containment measures will prove to be largely transient in nature. Yet further research is needed to assess the long-term consequences of social distancing measures.

There has been an increasing number of people living alone in Europe over the past 20 years, as a result of both ageing and cultural norms. Research shows that living alone might be associated with loneliness. However, there is no substantial evidence overall of a long-term increase in chronic loneliness [29,[44], [45], [46]]. Nonetheless, given the recent prevalence and salience of loneliness in the public sphere, a more systematic understanding of a relatively understudied issue remains key for policymakers in order to destigmatize loneliness, prioritise properly and design targeted loneliness interventions (see also [47]).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations of Competing Interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.09.002.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Cacioppo J.T., Patrick W. W. W. Norton & co; New York: 2008. Loneliness: Human Nature and The Need For Social Connection. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hertz, N., (2020) The lonely century: coming together in a world that's pulling apart, Sceptre eds. 352 pages.

- 3.Holt-Lunstad J., Smith T.B., Baker M., Harris T., Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015;10(2):227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkley L.C., Cacioppo J.T. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2010;40(2):218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkley L.C., Thisted R.A., Masi C.M., Cacioppo J.T. Loneliness predicts increased blood pressure: Five-year cross-lagged analyses in middle-aged and older adults. Psychol. Aging. 2010;25(1):132–141. doi: 10.1037/a0017805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cacioppo J.T., Hughes M.E., Waite L.J., Hawkley L.C., Thisted R.A. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol. Aging. 2006;21(1):140–151. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cacioppo J.T., Yuan Chen H., Cacioppo S. Reciprocal influences between loneliness and self-centeredness: a cross-lagged panel analysis in a population-based sample of African American, Hispanic, and Caucasian Adults. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017;43(8):1125–1135. doi: 10.1177/0146167217705120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelders Y., de Vaan K. European Commission Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion; Brussels: 2018. ESPN thematic report on challenges in long-term care Netherlands 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skopeliti C. Japan appoints “minister for loneliness” after rise in suicides. Independent. 2021 https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/japan-minister-loneliness-suicides-tetsushi-sakamoto-b1807236.html Retrieved 21 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fergusson M. How does it really feel to be lonely? Economist. 2018 https://www.economist.com/1843/2018/01/22/how-does-it-really-feel-to-be-lonely January 22. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lepore J. Vol. 8. The New Yorker; 2020. (The History of loneliness). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varga T., V., et al. Loneliness, worries, anxiety, and precautionary behaviours in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal analysis of 200,000 Western and Northern Europeans. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2021;2:100020. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonsaken T., Schoultz M., Thygesen H., Ruffolo M., Price D., Leung J., et al. Loneliness and its associated factors nine months after the COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-national study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18062841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bu F., Steptoe A., Fancourt D. Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health. 2020;186:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L.Z., Wang S. Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113267. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffart A., et al. COVID-19 Pandemic: Risk Factors and Associations With Psychopathology. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11:589127. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wickens C.M., McDonald A.J., Elton-Marshall T., Wells S., Nigatu Y.T., Jankowicz D., et al. Loneliness in the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with age, gender and their interaction. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021;136:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Tilburg T., G., et al. Loneliness and Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study Among Dutch Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2021;76(7):e249–e255. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Jong Gierveld J., Van Tilburg T.G., Dykstra P.A. In: The cambridge handbook of personal relationships. 2nd edition. Vangelisti A., Perlman D., editors. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2016. Loneliness and social isolation; pp. 485–500. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perlman D., Peplau L.A. In: Preventing the harmful consequences of severe and persistent loneliness. Peplau L.A., Goldston S., editors. National Institute of Mental Health; Rockville, MD, US: 1984. Loneliness research: a survey of empirical findings; pp. 13–46. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersson L. Loneliness research and interventions: a review of the literature. Aging & Mental Health. 1998;2(4):264–274. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss R.S. The MIT Press; Cambridge, MA, US: 1973. Loneliness: the experience of emotional and social isolation. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eurofound . Publications Office of the European Union; Luxembourg: 2017. Quality of life, quality of public services, and quality of society. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eurofound . Publications Office of the European Union; Luxembourg: 2020. Living, working and COVID-19, COVID-19 series. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sundström G., Fransson E., Malmberg B., Davey A. Loneliness among older Europeans. Eur. J. Ageing. 2009;6(4):267–275. doi: 10.1007/s10433-009-0134-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang K., Victor C. Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing Soc. 2011;31(8):1368–1388. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fokkema T., De Jong Gierveld J., Dykstra P.A. Cross-national differences in older adult loneliness. J. Psychol. 2012;146(1-2):201–228. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.631612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.d’Hombres B., et al. Loneliness and Social Isolation: An Unequally Shared Burden in Europe. IZA Discussion Paper. 2021;14245 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3823612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dykstra P.A. Older adult loneliness: myths and realities. Eur. J. Ageing. 2009;6(2):91–100. doi: 10.1007/s10433-009-0110-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luhmann M., Hawkley L.C. Age differences in loneliness from late adolescence to oldest old age. Dev. Psychol. 2016;52(6):943–959. doi: 10.1037/dev0000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ortiz-Ospina, E., Giattino C., and M. Roser (2020) "Time Use". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/time-use' [Online Resource].

- 32.Hansen T., Slagvold B. Late-life loneliness in 11 European countries: results from the generations and gender survey. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015;124(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lykes V.A., Kemmelmeier M. What predicts loneliness? Cultural difference between individualistic and collectivistic societies in Europe. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2013;45(3):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teo A.R., Choi H., Andrea S.B., Valenstein M., Newsom J.T., Dobscha S.K., Zivin K. Does mode of contact with different types of social relationships predict depression in older adults? Evidence from a nationally representative survey. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015;63(10):2014–2022. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savikko N., Routasalo P., Tilvis R.S., Strandberg T.E., Pitkälä K.H. Predictors and subjective causes of loneliness in an aged population. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2005;41(3):223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Jong Gierveld J., Tesch-Römer C. Loneliness in old age in Eastern and Western European societies: theoretical perspectives. Eur. J. Ageing. 2012;9(4):285–295. doi: 10.1007/s10433-012-0248-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nicolaisen M., Thorsen K. Loneliness among men and women--a five-year follow-up study. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18(2):194–206. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.821457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maes M., Qualter P., Vanhalst J., Van den Noortgate W., Goossens L. Gender differences in loneliness across the lifespan: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pers. 2019;33:642–654. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lyu Y., Forsyth A. Planning, Aging, and Loneliness: Reviewing Evidence About Built Environment Effects. Journal of Planning Literature. 2022;37(1):28–48. doi: 10.1177/08854122211035131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tobiasz-Adamczyk B., Zawisza K. Urban-rural differences in social capital in relation to self-rated health and subjective well-being in older residents of six regions in Poland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2017;24(2):162–170. doi: 10.26444/aaem/74719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Jong Gierveld J., Kamphuis F. The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1985;9(3):289–299. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russell D.W. UCLA loneliness scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 1996;66(1):20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Jong Gierveld J., Van Tilburg T. A 6-Item Scale for Overall, Emotional, and Social Loneliness: Confirmatory Tests on Survey Data. Research on Aging. 2006;28(5):582–598. doi: 10.1177/0164027506289723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beutel M.E., Klein E.M., Brähler E., Reiner I., Jünger C., Michal M., et al. Loneliness in the general population: prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mund M., Freuding M.M., Möbius K., Horn N., Neyer F.J. The stability and change of loneliness across the life span: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2020;24(1):24–52. doi: 10.1177/1088868319850738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suanet B., van Tilburg T.G. Loneliness declines across birth cohorts: the impact of mastery and self-efficacy. Psychol. Ageing. 2019;34(8):1134–1143. doi: 10.1037/pag0000357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duffy B. Atlantic Books; London: 2021. Generations: does when you're born shape who you are? EPUB. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.