Abstract

Background

Sexual and physical abuse are associated with binge eating and overeating, but few studies have examined association of the identity of the perpetrator with survivors’ risk of binge eating and overeating.

Purpose

To examine the risk of binge eating and overeating by (1) type of abuse and identity of the perpetrators and (2) cumulative abuse experiences/perpetrators.

Methods

Data came from Eating and Activity over Time (N= 1407; ages 18–30 during 2017–2018). Sexual abuse perpetrators included family members, non-family members, and intimate partners. Physical abuse perpetrators included family members and intimate partners. Cumulative abuse experiences were defined as the number of types of abuse experienced. Modified Poisson regressions were used to examine the risk of binge eating (overeating with loss of control) and overeating (without loss of control), by (1) abuse type and perpetrator and (2) cumulative abuse experiences.

Results

For binge eating, risk factors included familial and intimate partner sexual abuse (RR=1.48 [95% CI=1.01–2.17] and 2.41, [95% CI=1.70–3.41], respectively) and physical abuse (RR=1.84, [95% CI=1.33–2.53] and 1.95, [95% CI=1.35–2.81], respectively), after adjustment for sociodemographic variables. For overeating, associations with physical abuse were close to the null, and those with sexual abuse were modest, with wide CIs that overlapped the null. Abuse experiences were cumulatively associated with binge eating, but not overeating.

Conclusion

Assessment of identity of the perpetrator, and cumulative abuse experiences/perpetrators may assist in identifying people at the greatest risk of binge eating.

Keywords: Sexual Abuse, Physical Abuse, Perpetrator, Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), Overeating, Binge Eating

Introduction

Overeating (i.e., consumption of unusually large quantities of food) and binge eating (i.e., overeating accompanied by a sense of loss of control) are public health concerns, given their associations with poor psychosocial outcomes (1–3), eating disorders (4), and excessive weight gain (5). To prevent binge eating and overeating, there is a need to identify and address factors related to such eating behaviors. A growing body of literature suggests that sexual abuse and physical abuse are associated with binge eating and overeating (6–10). Survivors of sexual or physical abuse may engage in problematic eating behaviors as a coping strategy to dissociate themselves from the emotional impact of abuse experiences (11–14). Thus far, however, studies investigating the relationship of sexual and physical abuse with binge eating and overeating have paid little attention to how the association may differ depending on the identity of the perpetrator (i.e., the nature of the relationship of the perpetrator with the survivor).

Theories suggest that coping strategies may differ depending on the identity of the perpetrator. For example, family betrayal theory (15–17) and the betrayal trauma theory (18–20) suggest that survivors abused by a person close to them, such as a family member, may realize the need to maintain the relationship with the perpetrator to have access to resources that the perpetrator provides (e.g., food and shelter). This, in turn, may lead to greater pressure to adapt to the experience of abuse (15–17,19,20). In contrast, if the perpetrator is a less central person who has no or minimal caretaking responsibility for the survivors (e.g., non-family members), survivors may experience less distress (18–20) and have more options for coping skills, strategies, and resources (e.g., support from family members) that may function as a source of resilience. However, what these theories may mean for binge eating and overeating remains unclear. The dearth of research on the identity of the perpetrator of sexual and physical abuse as a predictor of binge eating and overeating is a critical research gap.

Importantly, survivors of one type of abuse by one type of perpetrator are at a high risk of experiencing other types of abuse victimization by other perpetrators. For example, survivors of childhood abuse, regardless of the identity of the perpetrator, frequently experience intimate partner violence (21–25). Likewise, it is possible that survivors of childhood abuse by family members are more likely to have experienced repeated abuse compared to survivors of childhood abuse by non-family members (6). For these reasons, the identity of the perpetrator may have a significant impact on the survivors. Such cumulative abuse episodes may place a person at greater risk of engaging in binge eating and overeating than a single type of abuse alone (6–10,26,27). Understanding how different types of abuse accumulate over childhood and beyond to affect later eating behaviors requires long-term follow-up beyond adolescence. However, to date, most studies of abuse and binge eating have been conducted among adolescents (6,8,10); as a result, little information is available about the longer-term association among emerging adults.

To address these gaps, the present study aims to examine the risk of binge eating and overeating among emerging adults by (1) the type of abuse (sexual or physical) and the identity of the perpetrator (i.e., family member, non-family member, or intimate partner), and (2) cumulative abuse experiences by the type and identity of the perpetrator. Building upon prior studies that examined the associations of abuse with disordered eating (6–10,28,29), we hypothesized that both sexual and physical abuse by all types of perpetrators (i.e., family members, non-family members, and intimate partners) would be associated with binge eating and overeating. Based on family betrayal theory (15–17) and the betrayal trauma theory (18–20), we further hypothesized that a person who experienced abuse perpetrated by a family member would be at the greatest risk of binge eating and overeating. Finally, because studies in adolescents and young adults suggest that multiple experiences of abuse confer greater risk of disordered eating behaviors (6–10,27), we hypothesized that there would also be a cumulative association between the number of abuse experiences (by type and perpetrator) and binge eating and overeating among adults.

1. Methods

2.1. Participants

EAT 2018 (Eating and Activity over Time) is the follow-up of EAT 2010, a population-based study of eating patterns, weight control behaviors, and weight status among 2793 middle and high school students at 20 urban public schools in Minneapolis and St Paul, Minnesota (30–32). EAT 2018 survey was completed by 1568 (65.8%) of the original participants of EAT 2010 eligible for contact at follow-up in 2017–2018. Data on a history of child abuse or intimate partner violence, and on current eating behaviors, were collected at EAT 2018. Among those who were included in EAT 2018 (N = 1568), participants with missing information regarding history of childhood abuse (n= 53), intimate partner violence (n= 51), binge eating or overeating (n= 19) and sociodemographic variables (n= 38) were further excluded, resulting in an analytic sample of 1407 participants. As attrition from EAT 2010 to EAT 2018 did not occur completely at random, inverse probability weighting (IPW) was used for all analyses to account for missing data (33,34) IPW minimizes potential response bias due to missing data and allows for extrapolation back to the original EAT 2010 school-based sample. Weights for IPW were derived as the inverse of the estimated probability that an individual responded at the two-time points based on several characteristics reported in 2010, including demographics, past year frequency of dieting, and weight status. Non-responders at follow-up were more likely than responders to be male (53.3% versus 41.7%); identify as black, Indigenous, or a person of color (87.0% versus 76.7%); report being born outside the U.S. (20.0% versus 16.3%); have parents with low educational attainment (41.4% versus 36.0%); and have never been on a diet (62.6% versus 59.9%) in 2010. Non-responders were also found to have a slightly greater mean BMI in 2010 (23.1±5.4 versus 22.9±5.3). After weighting, there were no significant differences between the analytic sample and the full EAT 2010 sample in demographic characteristics, dieting, or weight status (p > 0.9). Among the 1407 participants who were assessed for abuse during childhood and emerging adulthood, the mean age was 22.0 years, 20.1% were white, and 53.9% were female (Table 1). Of the 1407 participants in this study, 15.0% and 15.9% self-reported a history of childhood sexual abuse and physical abuse, respectively, and 6.7% and 8.0% reported a history of intimate partner sexual violence and intimate partner physical violence, respectively. More than 12% and 8%, respectively, reported engagement in binge eating (overeating with loss of control) and overeating without loss of control. All study protocols were approved by the University of Minnesota’s Institutional Review Board Human Subjects Committee.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, presented with row percentages (N=1407)

| History of abuse | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever (N=408) |

Never (N=999) |

P-value | |

| Age in years M±SD | 22.0 (2.0) | 22.0 (2.0) | 0.83 |

| Race (n, row %) | |||

| White | 102 (29.3%) | 243 (70.7%) | 0.76 |

| Black or African American | 91 (30.4%) | 208 (69.6%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 70 (28.5%) | 176 (71.5%) | |

| Asian American | 69 (21.6%) | 250 (78.4%) | |

| Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (12.5%) | 7 (87.5%) | |

| American Indian or Native Americans | 25 (45.5%) | 30 (54.6%) | |

| Mixed or others | 50 (37.0%) | 85 (63.0%) | |

| Gender (n, row %) | |||

| Male | 120 (21.2%) | 463 (78.8%) | <0.01 |

| Female | 288 (34.9%) | 536 (65.1%) | |

| Socioeconomic status (n, row%) | |||

| Low | 157 (30.2%) | 354 (69.8%) | 0.63 |

| Low-Medium | 85 (28.0%) | 216 (72.1%) | |

| Medium | 72 (29.5%) | 165 (70.5%) | |

| Medium-high | 57 (24.3%) | 171 (75.7%) | |

| High | 37 (27.6%) | 93 (72.4%) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.6 (7.3) | 26.8 (6.9) | 0.06 |

Note: % are weighted to reflect the original EAT 2010 participants.

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Independent variables

2.2.1.1. Abuse type and relationship with perpetrator

Verbatim questions assessing abuse on the EAT 2018 survey are provided in Table 2, along with response options, categorization, and psychometric properties. Briefly, childhood sexual abuse was categorized into familial or non-familial abuse; a third sexual abuse category was included for intimate partner sexual violence, in which the perpetrator was either a dating partner or spouse. Physical abuse was categorized into either familial childhood physical abuse or intimate partner physical violence from a dating partner or spouse (Table 2). The EAT 2018 survey did not ask about non-familial childhood physical abuse because childhood physical abuse is most often perpetrated by family members (35,36).

Table 2.

Verbatim questions, response options and psychometric properties of variables

| Variables | Verbatim question | Response options, categorization | Psychometric properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | |||

| Familial childhood sexual abuse (52,53) | Someone in your family touched you in a sexual way against your wishes or forced you to touch them in a sexual way. | No Yes |

Test-retest % agreement = 92% at EAT 2018 |

| Non-familial childhood sexual abuse (52,53) | Someone outside your family touched you in a sexual way against your wishes or forced you to touch them in a sexual way (do not include events that involved a dating partner) | No Yes |

Test-retest % agreement = 92% at EAT 2018 |

| Intimate partner sexual violence (52) | Been forced to touch a dating partner or spouse sexually or had some type of sexual behavior forced on you | No Yes (in the past year or more than a year ago) |

Test-retest % agreement =93% at EAT 2018 |

| Familial childhood physical abuse (52,53) | An adult in my family hit me so hard it left me with bruises or marks | Never Rarely, sometimes, often, very often |

Test-retest % agreement = 96% at EAT 2018 |

| Intimate partner physical violence (53) | Been hit, shoved, held down or had some other physical force used against you by a spouse or someone you were dating | No Yes (in the past year or more than a year ago) |

Test-retest % agreement = 89% |

| Dependent variable | |||

| Binge eating (36,37) | In the past year, have you ever eaten so much food in a short period of time that you would be embarrassed if others saw you (binge eating)? During the times when you ate this way (overeating in a short period of time), did you feel you could not stop eating or control what or how much you were eating? |

0: no 1: yes (overeating accompanied by loss of control) |

Test-retest % agreement = 94% |

| Overeating (36,37) | In the past year, have you ever eaten so much food in a short period of time that you would be embarrassed if others saw you (binge eating)? | 0: no 1: yes |

Test-retest % agreement = 90% |

Test-retest reliability of measures was examined using data from a subgroup of 112 young adult participants who completed the EAT 2018 survey twice within a period of three weeks

2.2.1.2. Cumulative abuse experiences from childhood through emerging adulthood

Cumulative abuse experiences were assessed as the number of different abuse experiences reported (i.e., the sum of familial childhood sexual abuse, non-familial childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner sexual violence, familial childhood physical abuse, and intimate partner physical violence) and ranged from 0 to 5. Because of the small number of participants who had experienced three or more abuse experiences, these were combined into a single category, resulting in four categories (0, 1, 2, and 3 or more abuse experiences).

2.2.2. Dependent variables

2.2.2.1. Binge eating and overeating

Binge eating and overeating were assessed with two items. The first item asked, “In the past year, have you ever eaten so much food in a short period of time that you would be embarrassed if others saw you binge eating)?” Participants who confirmed overeating were asked about a “sense of loss of control” during “overeating.” Items were adapted from Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns-Revised (37) and Minnesota Adolescent Health Survey (38). We defined binge eating as eating large quantities of food accompanied by loss of control. Overeating was defined as eating large quantities of food without loss of control. Details of the dependent variables, including verbatim questions, response options, categorization, and psychometric properties, are provided in Table 2.

2.2.3. Covariates

Sociodemographic variables, including age, ethnicity/race, gender, and socioeconomic status were self-reported. Ethnicity/race was assessed based on responses to the questions, “Do you think of yourself as (a) white, (b) black or African American, (c) Hispanic or Latino, (d) Asian American, (e) Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or (f) American Indian or Native American.” Socioeconomic status was derived from parental education level, family eligibility for public assistance, eligibility for free or reduced prices school lunch, and parental employment status in EAT 2010 when the participants for this study were 11–20 years old (39,40). These variables were included as adjustment variables to represent individuals’ positions within racialized, gendered, and class-based social hierarchies, which are important influences on individual vulnerabilities to both abuse and eating behaviors (41).

2.3. Statistical analysis

Participant characteristics are presented as mean (SD) or % frequency. All models were adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics. Modified Poisson regressions were used to model the relationship of binge eating and overeating as a function of perpetrator type separately for sexual and physical abuse. To examine which perpetrator was most strongly and independently associated with binge eating and overeating, models were mutually adjusted for perpetrators, separately for sexual abuse and physical abuse. Similar models were run as a function of cumulative abuse experiences. To further examine how the risks of binge eating and overeating among survivors abused by both perpetrators (i.e., a family member and an intimate partner) differs compared with those of survivors who have been abused by a family member only, separate modified Poisson regressions were run with dummy coded independent variables. Interactions between abuse and gender were tested to determine if analyses should be stratified by gender. However, no interactions were statistically significant, (p interaction .06 to .82), therefore non-stratified results are presented in this study. In the results, relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are provided with the null value being 1.0. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

2. Results

3.1. Prevalence of adverse experiences and eating behaviors

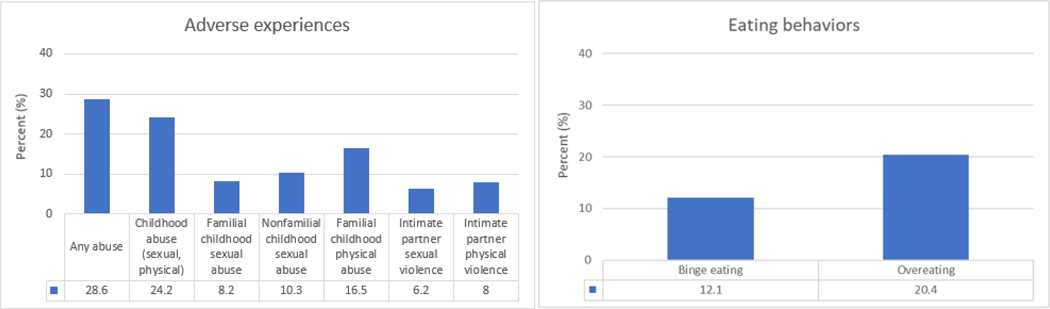

In this study, 24% of young adults recalled experience of childhood abuse and 11% reported experience of intimate partner violence. In particular, of a history of any abuse, physical abuse perpetrated by a family member was most prevalent (16.5%), followed by sexual abuse perpetrated by a family member (10.3%). Regarding eating behaviors, 12.1% of the young adults reported binge eating and 20.4% reported overeating (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of adverse experiences and eating behaviors (N=1407)

3.2. Risk of binge eating by type of abuse and identity of the perpetrator

Sexual abuse by all types of perpetrators (i.e., family members, non-family members, and intimate partners) showed moderate associations with binge eating, although some CIs included the null value after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics. Amongst perpetrators, sexual abuse perpetrated by intimate partners was most strongly associated with binge eating. Childhood sexual abuse perpetrated by family members and childhood sexual abuse perpetrated by non-family members were each associated with modestly elevated risk of binge eating (Table 3). Sexual abuse perpetrated by both family members and intimate partners was more strongly associated with binge eating compared to sexual abuse perpetrated by family member only, although the point estimate was accompanied by wide CI and overlapped the null value after adjustment for sociodemographic variables (RR=1.58, 95% CI=0.81–3.10).

Table 3.

Relative risk (RR) and confidence intervals (95% CI) for self-reported binge eating and overeating by type of abuse and identity of the perpetrator

| Binge eating | Overeating | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of abuse | Perpetrator | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 |

| RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | ||

| Sexual abuse | None | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Family members (N=119) | 1.48 (1.01–2.17) | 1.04 (0.65–1.66) | 0.68 (0.32–1.45) | 0.60 (0.26–1.42) | |

| Non-family members (N=157) | 1.32 (0.90–1.95) | 0.88 (0.55–1.42) | 1.23 (0.72–2.09) | 1.47 (0.72–2.98) | |

| Dating partner/spouse (N=94) | 2.41 (1.70–3.41) | 1.92 (1.23–2.99) | 1.17 (0.62–2.19) | 1.27 (0.61–2.64) | |

| Physical abuse | None | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Family members (N=223) | 1.84 (1.33–2.53) | 1.59 (1.09–2.32) | 0.80 (0.46–1.40) | 0.81 (0.45–1.46) | |

| Dating partner/spouse (N=113) | 1.95 (1.35–2.81) | 1.25 (0.81–1.93) | 0.85 (0.42–1.75) | 0.80 (0.37–1.71) | |

RR = relative risk; CI= confidence interval

Model 1: Adjusted for adjusted for age, ethnicity/race, gender, and socioeconomic status

Model 2: Model 1+ mutual adjustment for perpetrators

Findings are weighted to reflect the original EAT 2010 participants

Physical abuse perpetrated by family members and physical abuse perpetrated by intimate partners were each strongly associated with binge eating (Table 3). Physical abuse perpetrated by both family members and intimate partners was more strongly associated with binge eating compared to physical abuse perpetrated by family members only, although the CI included the null value (RR=1.67, 95% CI = 0.97–2.87).

3.3. Risk of binge eating by abuse type and identity of the perpetrator, mutually adjusted for other perpetrators

Regarding sexual abuse, intimate partner perpetration was associated with binge eating compared to no experience of sexual abuse, independent of other perpetrator types. Point estimates for family members and non-family sexual abuse perpetration were close to null once intimate partner sexual violence was taken into account. Regarding physical abuse, perpetration by family members and by intimate partners were each associated with binge eating, although the latter association was modest with a wide CI that included the null (Table 3).

3.4. Risk of overeating by type of abuse and identity of the perpetrator

Point estimates of the associations between identity of perpetrators of sexual abuse and overeating were highly imprecise, with 95% CIs including the null after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics. However, sexual abuse perpetrated by both family members and intimate partners was more strongly associated with overeating compared to sexual abuse perpetrated by family members only, although the CI overlapped the null value after adjustment for sociodemographic variables (RR=1.21, 95% CI=0.71–2.06).

In regard to physical abuse, associations between identity of perpetrators and overeating were close to the null, suggesting no associations (Table 3). However, physical abuse perpetrated by both family members and intimate partners was more strongly associated with binge eating compared to physical abuse perpetrated by family members only, although the 95% CI included the null value (RR=1.37, 95% CI = 0.85–2.22).

3.5. Risk of overeating by type of abuse and identity of the perpetrator, mutually adjusted for other perpetrators

No substantial changes in point estimates were observed between models adjusted for sociodemographic variables compared to models mutually adjusted for different types of perpetrations. In the models mutually adjusted for perpetrator types, childhood sexual abuse perpetrated by non-family members and sexual violence perpetrated by intimate partners retained suggestive independent association with overeating, though CIs overlapped the null. Associations between physical abuse perpetrated by family members or intimate partners were close to the null.

3.6. Associations of cumulative abuse experiences with binge eating and overeating

There was a step-wise association between the cumulative number of abuse experiences and risk of binge eating, with the point estimate reaching a plateau and leveling off after two or more abuse experiences (Table 4). For overeating, the RRs were close to the null (Table 4).

Table 4.

Relative Risk (RR) and confidence intervals (95% CI) for cumulative experiences of lifetime abuse (N=1407)

| Cumulative number of abuse experiences | Binge eating | Overeating |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | |

| 0 (N=999) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1 (N=231) | 1.84 (1.30–2.61) | 1.11 (0.68–1.81) |

| 2 (N=91) | 2.18 (1.38–3.44) | 0.91 (0.43–1.94) |

| 3–5 (N=86) | 2.17 (1.41–3.33) | 0.78 (0.35–1.77) |

RR = relative risk; CI= confidence interval

Adjusted for adjusted for age, ethnicity/race, gender, and socioeconomic status

Findings are weighted to reflect the original EAT 2010 participants

3. Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine associations of sexual and physical abuse by different types of perpetrators (i.e., family members, non-family members, and intimate partners) with binge eating and overeating among emerging adult survivors, and to assess whether abuse experiences are cumulatively associated with binge eating and overeating. We found that abuse was associated with binge eating, but not with overeating. Specifically, sexual abuse and physical abuse perpetrated by family members or intimate partners were associated with binge eating. We also found that abuse experiences were cumulatively associated with binge eating, with a threshold of 2 or more abuse experiences. In contrast to binge eating, for overeating, there was no evidence of associations with any abuse type; although non-familial and intimate partner sexual abuse were modestly associated with overeating, they were accompanied by very wide CIs compatible with estimates ranging from a reduced risk to an almost threefold higher risk.

In this study, the prevalence of any childhood abuse or intimate partner violence (28.6%) is similar to that reported in other population studies and in national and state level reports, in which approximately 25% of adults report a history of childhood abuse or intimate partner violence (3,4). Regarding the rate of binge eating and overeating, the prevalence reported in our study (10.3% and 20.4% respectively) is greater than the prevalence reported in other studies (< 10%) (5,6). Unlike other studies where binge eating and overeating are defined as episodes occurring at least once a week, the frequency was not inquired in our study, which may have resulted in a greater estimated prevalence of binge eating and overeating.

Regarding binge eating, sexual abuse perpetrated by intimate partners was strongly and independently associated with binge eating, after adjustment for sociodemographic variables and other perpetrator types. This finding is in contrast to our hypothesis that abuse perpetrated by a family member would be most strongly associated with binge eating. The stronger association with intimate partner sexual abuse compared to familial or non-familial childhood sexual abuse may reflect the shorter amount of time elapsed between the occurrence of abuse and assessment of eating behaviors (i.e., intimate partner abuse was likely more proximal to when binge eating, and overeating were assessed than childhood family or non-family abuse). With regard to physical abuse, findings were as expected. Perpetration of childhood physical abuse by a family member showed a greater independent association with binge eating compared to perpetration by an intimate partner, which aligns with family betrayal theory (15–17) and betrayal trauma theory (18–20). Our examination of the abusive relationship with binge eating suggests that different perpetrators may have different impacts on binge eating, which extends the literature examining childhood abuse and intimate partner violence on disordered eating behaviors (6,8–10,42,43). Regarding cumulative abuse experiences, we found a cumulative association of abuse experiences with binge eating, but not with overeating. This finding of a cumulative association between abuse experiences and binge eating aligns with other studies reporting that cumulative exposure to multiple abuse types poses a greater risk of disordered eating behaviors (6,8–10,27,42).

Our finding of close to the null associations between abuse, including cumulative abuse exposure, and overeating is difficult to directly compare to prior literature, given limited studies of overeating without loss of control. These findings are inconsistent with the literature on disordered eating generally, which report associations with a history of abuse (6–10,42–46).

The association found with binge eating but not with overeating indicates that the types of abuse and identity of the perpetrator may affect the sense of loss of control, a feature which distinguishes binge eating from overeating. Other studies have found abuse to be associated with concerns related to loss of control including emotional dysregulation and addictive behaviors, such as alcohol use disorder, marijuana abuse, and developing dependence on opioids (47,48). However, it remains unclear whether addictive behaviors in relation to abuse depend on the identity of the perpetrator in a similar manner to loss of control in eating behaviors.

This study has several strengths, including the ethnically/racially and socioeconomically diverse participants from a population-based study. Examination of the associations among adults, a group that has been less frequently studied in examining associations between abuse and disordered eating behaviors also allows findings to be more generalizable to diverse population groups. Lastly, we added to the growing body of literature by integrating and comprehensively examining different perpetrator identities in relation to binge eating and overeating.

Despite the important findings and strengths of this study, several limitations should be noted. First, because abuse was measured via retrospective self-reporting, recall bias may be present. In particular, social stigma associated with abuse may have led individuals to underreport their history of abuse (49). Second, mutual adjustment for each type of perpetrator may have the potential for over-adjustment, but we chose to run mutually adjusted models in an attempt to disentangle the associations of different types of perpetrator–survivor relationships. However, if part of the effect of one type of abuse operates via another type, then this approach may have adjusted away some of the effect. For this reason, we have provided estimates with and without mutual adjustment. Third, our reliance on data from a large epidemiologic survey means that the abuse measures included in this study were more limited than they might have been had the sole focus been on abuse. Fourth, caution is required when interpreting the results of the association of cumulative adverse experience with overeating and binge eating. The cumulative adverse experiences assessed in this study reflect the experience of persons who were subjected to multiple types of adverse experiences, rather than persons who experienced multiple incidents of a single type of adversity. Therefore, the cumulative adverse experiences assessed in the current study reflect the breadth of adverse experiences, rather than the depth or repetition of such experiences. Fifth, overeating and binge eating examined in this study were assessed using a brief assessment tool. Although brief assessment tools are commonly used in large epidemiologic surveys to assess health at a populational level, they may result in some measurement error. Further, the participants were geographically restricted to Minnesota, which may limit the generalizability to other geographical regions. Last, the substantial attrition from EAT 2010 to EAT 2018 (43.8%), which did not occur completely at random, may have led to selection bias. To account for attrition between EAT 2010 and EAT 2018 as well as to represent the original EAT 2010 sample, all models were weighted using IPW (33,34).

Findings from the present study have implications for prevention, future research, and clinical practice. Regarding prevention, we report that both sexual and physical abuse are associated with binge eating. In particular, for sexual abuse, it is those in an interpersonal relationship involving intimacy, and for physical abuse, it is the perpetrators who are responsible for caregiving of the child (i.e., family members) who have the greatest impact on survivors to engage in binge eating. Relatedly, cumulative abuse experiences place individuals at greater risk of binge eating, relative to a single abuse experience. These findings emphasize the importance of proactive action for both primary abuse prevention as well as secondary prevention among survivors to prevent additional abuse experiences. For primary prevention of abuse, at the community level, programs should be developed that assist individuals to develop appropriate parenting skills and healthy relationships. At the societal level, our findings stress the importance of the development and emphasis of programs, regulations, and policies as an important approach and strategy to prevent abuse and violence (50–52). In cases where abuse does occur and is identified, interventions must focus on the prevention of repeated victimization, for example, by building healthy relationship skills in survivors and providing support around their health and wellbeing (53).

With regard to research, more work should be done on the underlying causes and factors that correlate with abuse and violence to identify what risk and protective factors may increase or decrease the risk of abuse and violence. Because individuals who experienced abuse may feel a loss of control, future studies would also do well to further examine associations of perpetrator types with addictive behaviors. Further, future studies should examine other types of disordered eating behaviors across different abuse types and identity of perpetrators. Regarding clinical practice, clinicians who work with individuals who struggle with binge eating may need to assess the individual’s lifetime history of abuse, living environment, and potential for ongoing abuse, which may cause continuous binge eating. Understanding the history of abuse, relationship with the perpetrator, and current living environment may further assist in tailoring an individualized treatment plan. Lastly, for the interventionist, efforts should be dedicated to developing interventions to assist survivors in building resilience and developing healthy coping skills and strategies.

4. Conclusion

Sexual and physical abuse are significant public health problems, as they span a person’s life course and have immediate and long-lasting health consequences. Understanding the potential impact of the perpetrator–survivor dynamics and cumulative abuse experiences has the potential to identify those most at risk of binge eating and overeating and assist providers in developing tailored assessment and intervention approaches for populations with the greatest need.

References

- 1. Goldschmidt AB, Wall MM, Loth KA, Bucchianeri MM, Neumark-Sztainer D. The course of binge eating from adolescence to young adulthood. Heal Psychol. 2014;33(5):457–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonneville KR, Horton NJ, Micali N, Crosby RD, Swanson SA, Solmi F, et al. Longitudinal associations between binge eating and overeating and adverse outcomes among adolescents and young adults: Does loss of control matter? NIH Public Access. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(2):149–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skinner HH, Haines J, Austin SB, Field AE. A prospective study of overeating, binge eating, and depressive symptoms among adolescent and young-adult women. J Adolesc Heal. 2012;50(5):478–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stice E, Marti CN, Shaw H, Jaconis M. An 8-Year Longitudinal Study of the Natural History of Threshold, Subthreshold, and Partial Eating Disorders from a Community Sample of Adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118(3):587–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, Malspeis S, Rosner B, Rockett HR, et al. Relation Between Dieting and Weight Change Among Preadolescents and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):900–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Date violence and date rape among adolescents: Associations with disordered eating behaviors and psychological health. Child Abus Negl. 2002;26(5):455–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer S, Stojek M, Hartzell E. Effects of multiple forms of childhood abuse and adult sexual assault on current eating disorder symptoms. Eat Behav. 2010;11(3):190–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, French S, Story M. Binge and purge behavior among adolescents: associations with sexual and physical abuse in a nationally representative sample: the Commonwealth Fund survey. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;6:771–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hazzard VM, Bauer KW, Mukherjee B, Miller AL, Sonneville KR. Associations between childhood maltreatment latent classes and eating disorder symptoms in a nationally representative sample of young adults in the United States. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Multiple Sexual Victimizations among Adolescent Boys and Girls: Prevalence and Associations with Eating Behaviors and Psychological Health. J Child Sex Abus. 2003;12(1):17–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demitrack MA, Putnam FW, Brewerton TD, Brandt HA, Gold PW. Relation of clinical variables to dissociative phenomena in eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147(9):1184–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gershuny BS, Thayer JF. Relations among psychological trauma, dissociative phenomena, and trauma-related distress: A review and integration. Clin Psychol Rev. 1999;19(5):631–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macfie J, Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Dissociation in maltreated versus nonmaltreated preschool-aged children. Child Abus Negl. 2001;25(9):1253–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanderlineden J, Vandereycken W, Claes L, Vanderlinden J, Vandereycken W, & Trauma Claes L., dissociation, and impulse dyscontrol: Lessons from the eating disordsers field. In: Traumatric dissociation: Neurobiology and treatment [Internet]. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2007. p. 317–31. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-05420-016 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delker BC, Smith CP, Rosenthal MN, Bernstein RE, Freyd JJ. When Home Is Where the Harm Is: Family Betrayal and Posttraumatic Outcomes in Young Adulthood. J Aggress Maltreatment Trauma. 2018;27(7):720–43. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freyd JJ, Birrell PJ. Blind to betrayal. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freyd JJ, DePrince AP, Gleaves DH The state of betrayal trauma theory: Reply to McNally—Conceptual issues and future directions. Memory; 2007. 295–311 p.

- 18.DePrince AP, Brown LS, Cheit RE, Freyd JJ, Gold SN, Pezdek K, Quina K. Motivated forgetting and misremembering: Perspectives from betrayal trauma theory. In: True and false recovered memories: Toward a reconciliation of the debate. New York, NY: Springer; 2012. p. 193–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freyd JJ. Memory and dimensions of trauma: Terror may be ‘all too-well remembered’ and betrayal buried. In: Critical issues in child sexual abuse: Historical, legal, and psychological perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. p. 139–73. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freyd JJ. Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maker AH, Kemmelmeier M, Peterson C. Child sexual abuse, peer sexual abuse, and sexual assault in adulthood: A multi-risk model of revictimization. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14(2):351–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arata CM CMA Child sexual abuse and sexual re-victimization. Clin Psychol. 2002;9:135–64. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Urquiza AJ, Goodlin-Jones BL Child sexual abuse and adult re-victimization with women of color. Violence Vict. 1994;9:223–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Re-victimization patterns in a national longitudinal sample of children and youth. Child Abus Negl. 2007;31(5):479–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abus Negl. 2009;33(7):403–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smyth JM, Heron KE, Wunderlich SA, Crosby RD, Thompson KM, Wonderlich SA, et al. The influence of reported trauma and adverse events on eating disturbance in young adults. Int J Eat Disord. 2008. Apr;41(3):195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasselle AJ, Howell KH, Dormois M, Miller-Graff LE. The influence of childhood polyvictimization on disordered eating symptoms in emerging adulthood. Child Abus Negl. 2017;68:55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The Long-Term Health Consequences of Child Physical Abuse, Emotional Abuse, and Neglect: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Bannon S, Salwen J, Hymowitz G. Weight-Related Abuse: Impact of Perpetrator-Victim Relationship on Binge Eating and Internalizing Symptoms. 2017. May 28;27(5):541–54. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larson NI, Wall MM, Story MT, Neumark-Sztainer DR. Home/family, peer, school, and neighborhood correlates of obesity in adolescents. Obesity. 2013. May;21(9):1858–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall MM, Larson N, Story M, Fulkerson JA, Eisenberg ME, et al. Secular trends in weight status and weight-related attitudes and behaviors in adolescents from 1999 to 2010. Prev Med (Baltim). 2012;54(1):77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arcan C, Larson N, Bauer K, Berge J, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Dietary and weight-related behaviors and body mass index among hispanic, hmong, somali, and white adolescents. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(3):375–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Little RJA. Survey nonresponse adjustments for estimates of means. Int Stat Rev. 1986. Aug;54(2):139–57. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seaman SR, White IR. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013. Jun 10;22(3):278–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families CB. Child maltreatment 2012. 2013.

- 36.Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Petta I, McPherson K, Greene A, and Li S. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-4): Report to Congress. 2010.

- 37.Yanovski SZ. Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns—Revised (QEWP-R). Obes Res. 1993;1:319–324. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blum R, Harris L, Resnick M RK. Technical Report on the Adolescent Health Survey. Univ Minnesota Adolesc Heal Progr. 1989; [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Larson NI., Eisenberg ME, Loth K. Dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(7):1004–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Croll J. Overweight status and eating patterns among adolescents: where do youths stand in comparison with the healthy people 2010 objectives? Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):844–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinstein JN, Geller A, Negussie Y, Baciu A. Communities in action: Pathways to health equity. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. National Academies Press; 2017. 1–558 p. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guillaume S, Jaussent I, Maimoun L, Ryst A, Seneque M, Villain L, et al. Associations between adverse childhood experiences and clinical characteristics of eating disorders. Sci Rep. 2016;2(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Capitaine M, Rodgers RF, Chabrol H. Unwanted sexual experiences, depressive symptoms and disordered eating among college students. Eat Behav. 2011;12:86–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ackard DM, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Long-Term Impact of Adolescent Dating Violence on the Behavioral and Psychological Health of Male and Female Youth. J Pediatr. 2007;151:476–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Thompson KM, Redlin J, Demuth G, et al. Eating disturbance and sexual trauma in childhood and adulthood. Int J Eat Disord. 2001. Dec 1;30(4):401–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ericsson NS, Keel PK, Holland L, Selby EA, Verona E, Cougle JR, et al. Parental disorders, childhood abuse, and binge eating in a large community sample. Int J Eat Disord. 2012. Apr;45(3):316–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baudin G, Godin O, Lajnef M, Aouizerate B, Berna F, Brunel L, et al. Differential effects of childhood trauma and cannabis use disorders in patients suffering from schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;175:161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bahk YC, Jang SK, Choi KH, Lee SH. The relationship between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation: Role of maltreatment and potential mediators. Psychiatry Investig. 2017. Jan 1;14(1):37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schönbucher V, Maier T, Mohler-Kuo M, Schnyder U, Landolt MA. Disclosure of Child Sexual Abuse by Adolescents: A Qualitative In-Depth Study. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(17):3486–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jutte D, Miller J, Erickson D. Neighborhood Adversity, Child Health, and the Role for Community Development. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Komro KA, Tobler AL, Delisle AL, O’mara RJ, Wagenaar AC. Beyond the clinic: improving child health through evidence-based community development. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13(172). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hendrikson H, Blackman K. State Policies Addressing Child Abuse and Neglect [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/Documents/Health/StatePolicies_ChildAbuse.pdf

- 53.Robinson AL. Independent Domestic Violence Advisors: A multi-site process evaluation. 2009.