Abstract

The sepL gene is expressed in the locus of enterocyte effacement and therefore is most likely implicated in the attaching and effacing process, as are the products encoded by open reading frames located up- and downstream of this gene. In this study, the sepL gene of the enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) strain EDL933 was analyzed and the corresponding polypeptide was characterized. We found that sepL is transcribed monocistronically and independently from the esp operon located downstream, which codes for the secreted proteins EspA, -D, and -B. Primer extension analysis allowed us to identify a single start of transcription 83 bp upstream of the sepL start codon. The analysis of the upstream regions led to the identification of canonical promoter sequences between positions −5 and −36. Translational fusions using lacZ as a reporter gene demonstrated that sepL is activated in the exponential growth phase by stimuli that are characteristic for the intestinal niche, e.g., a temperature of 37°C, a nutrient-rich environment, high osmolarity, and the presence of Mn2+. Protein localization studies showed that SepL was present in the cytoplasm and associated with the bacterial membrane fraction. To analyze the functional role of the SepL protein during infection of eukaryotic cells, an in-frame deletion mutant was generated. This sepL mutant was strongly impaired in its ability to attach to HeLa cells and induce a local accumulation of actin. These defects were partially restored by providing the sepL gene in trans. The EDL933ΔsepL mutant also exhibited an impaired secretion but not biosynthesis of Esp proteins, which was fully complemented by providing sepL in trans. These results demonstrate the crucial role played by SepL in the biological cycle of EHEC.

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) strains are the major cause of bloody diarrhea and acute renal failure (10, 18). EHEC interacts with the gut mucosa, leading to histopathological changes which are collectively called attaching and effacing (A/E) lesions (18). While the production of Shiga toxins is a distinctive feature of Shigella and EHEC, the capacity to cause A/E lesions of EHEC is shared by many other enteric pathogens like enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), diffusely adhering E. coli, Hafnia alvei, and Citrobacter freundii (2, 37, 44). These bacteria contain a pathogenicity island called the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE), which codes for bacterial products sufficient for triggering the A/E lesions (33, 34). The LEE sequences of EPEC and EHEC have been published (15, 42), and most of the open reading frames (ORFs) are highly conserved, in particular the identified components of the type III secretion apparatus (98 to 100% identity), except for the sepZ gene. The secreted structural and putative effector proteins EspA, EspB, EspD, and Tir are more diverse (84.63, 74.01, 80.36, and 66.48% identity, respectively).

Despite the overall sequence similarities of the ORFs within the LEE in EPEC and EHEC, Esp proteins appear to be involved to different extents in the interactions between pathogenic E. coli and eukaryotic cells (31). EspA apparently plays a major role in the attachment of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli to host cells (7, 14), whereas only a slightly impaired attachment was observed in EPEC and rabbit EPEC strains carrying an espA mutation (1, 26). EspD is essential for the generation of EspA-containing filaments in EHEC, whereas in EPEC the abrogation of EspD expression leads only to the production of shorter EspA-containing filaments (28, 31).

In addition, it seems that there are important differences in transcriptional regulation. In fact, we have recently reported that the espA, espB, and espD genes are transcribed as a polycistronic operon, whereas sepL, the gene located upstream of espA, is transcribed independently (7). In contrast, analysis of the transcriptional organization of the LEE from EPEC revealed that the espA, -D, and -B genes form part of a polycistronic operon, which also encompasses the upstream (sepL) and downstream (orf27, escF, orf29, and espF) ORFs (36).

Despite its location within a conserved region encompassing essential virulence factors and its designation by homology to a type III secretion factor (15), no evidence has been produced yet concerning the potential relevance of the product encoded by sepL in the infection process. In this study, we report the construction and characterization of an EHEC mutant containing an in-frame deletion of the sepL gene. The obtained results allowed us to confirm the critical role played by SepL in the infection process of EHEC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

Bacteria (Table 1) were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (43) or on LB agar, minimal M9 medium supplemented with 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose as the carbon source (43), or serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (GIBCO, Karlsruhe, Germany) supplemented with 100 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. Plasmids (Table 1) were maintained in E. coli strain DH5α, and strain INVαF′ was used as a recipient for cloning fragments amplified by PCR into the pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen). Media were supplemented with chloramphenicol (50 μg/ml), ampicillin (200 μg/ml), or nalidixic acid (50 μg/ml) when required.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype, phenotype, or serotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 λ− | 51 |

| XL1blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F′ proAB laclqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| M15(pREP4) | Nals Strs Rifslac ara gal mtl F−recA+uvr+ | Qiagen |

| INVαF′ | F′ endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 φ80 lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169 deoR λ− | Invitrogen |

| S17-1(λpir) | Tpr Smr, recA thi pro hsdR M+ RP4:2-Tc:Mu:Km Tn7 λpir | 12 |

| E32511/0 | O157:H− EHEC strain | 50 |

| E32511/0 Nalr | Nalr spontaneous derivative of EHEC E32511/0 | 30 |

| EDL933 | O157:H7 EHEC strain | 41 |

| EDL933ΔsepL | EDL933 derivative containing an in-frame deletion of the sepL gene | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pANK1 | Cmr Kmr pMAK700oriT derivative with a multiple-cloning site and an aph-A3 cassette in the HindIII site | 31 |

| pANK84 | Apr Kmr pCR2.1 derivative containing the PCR fragment generated using primers ANK7191 and AE19 encompassing the region between eaeA (position 1891 of the sequence AF071034_26a) and espB (position 4739 of the sequence Y13068a) | 31 |

| pANK157 | Cmr Kmr pANK1 derivative with a ΔsepLEDL933 fragment | This study |

| pAKSK79 | Derivative of pANK84 encompassing the region between eaeA (position 1891 of the sequence AF071034_26a) and start codon of espA | This study |

| pUJ9TT | Apr multicopy promoter probe vector to generate fusions with the lacZ gene | 24 |

| pUJ2 | Apr pUJ9TT derivative containing a 725-bp PCR-generated fragment encompassing the sepL promoter region | This study |

| pQE30-sepLEE | Apr pQE30 derivative containing the PCR fragment generated within the primers ANK10 and ANK11 and translationally fused to an N-terminal His tag for purification of overexpressed protein | This study |

EMBL database accession number.

DNA manipulations.

Standard DNA techniques were carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (43). Oligonucleotides (Table 2) were synthesized by GIBCO. DNA sequencing and electroporation were carried out as described before (30). Restriction and modification enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Schmalbach, Germany). Database searches and amino acid sequence analysis were performed using the BLASTP + BEAUTY (4, 52), TBLASTN (46), PSORT (39), and TMPred (22) algorithms.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used for PCR and sequencing

| Name | Nucleotide sequence (5′→3′) | Positiona |

|---|---|---|

| ANK10 | GCAGGATCCATGGCTAATGGTATTG | 1627–1642 |

| ANK11 | GCAGGTACCTCAAATAATTTCCTCCTTATA | 2682–2662 |

| ANKA291 | GTGAGTTTCCAATGGCTAATGG | 1616–1637 |

| ANKA292 | GGATCCCGGGAGCAGCTTCTCGATTGTCG | 1880–1862 |

| ANKA293 | GAAGCTGCTCCCGGGATCCGATAGTGAGCAGAGAGAGAATG | 2611–2632 |

| ANKA294 | CATCTTTTGTGCCGTGGTTGAC | 2980–2959 |

| ANK22 | CCGGATCCCGTTATCTTCCGTACCTAGC | 1385–1404 |

| ANK9952 | CCGCCTTCACTGTTTGCAGATCACC | 3161–3137 |

| 1627-lac1 | CCGGATCCGTAGCACCAATCACGCTC | 1099–1116 |

| 1627-lac2 | GCGGATCCCCCAGGCTTAGCCCTTCAATCG | 1823–1802 |

| ORF1-PE | TGAATTAGAATTAAAAACAGATGC | 1683–1659 |

Position of the oligonucleotide respect to the published sequence (EMBL accession no. Y13068). Restriction sites are underlined.

β-Galactosidase assays.

A fragment comprising the sepL promoter region was generated by PCR using the primers 1627-lac1 and 1627-lac2, which incorporated additional BamHI restriction sites. The PCR fragment was then digested with BamHI and translationally fused to the lacZ gene of the promoter probe vector pUJ9TT (24), thereby generating plasmid pUJ2. To perform β-galactosidase assays, bacteria were grown until they reached the exponential growth phase and cultures were reinoculated to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 into the appropriate medium. To test the influence of oligoelements on gene expression, bacteria were grown in M9-glucose medium supplemented with either MgSO4 (1, 7, and 30 mM), MgCl2 (1, 7, and 30 mM), MnSO4 (0.0033, 0.33, and 3.3 mM), CaCl2 (0.01, 0.1, and 1 mM), FeSO4 (0.25, 25, and 250 μM), or Fe(NO3)3 (1 mM). NH4Cl was added to nitrogen-free M9 medium at concentrations of 0.5, 2, and 10 mM. Osmotic regulation was tested in minimal M9-glucose medium by the addition of NaCl or sucrose at final concentrations of 10 or 430 mM. Samples were taken at different time intervals, the OD600 was determined, and aliquots were removed and centrifuged at 8,000 × g to recover bacterial pellets. The β-galactosidase assay was performed with the β-GAL reporter gene assay chemiluminescent kit (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the supplier's instructions, except that lysis was performed by resuspending bacteria in 500 μl of the supplied lysis solution supplemented with chloroform (20 μl) and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (20 μl) and incubating them subsequently for 30 min at room temperature. The samples were measured using a Victor 1420 multilabel counter fluorometer (EG&G WALLAC, Turku, Finland), and the results were normalized for the number of bacterial cells used. Nonspecific effects on β-galactosidase activity resulting from the composition of the media were ruled out by using adequate protein standards.

Primer extension analysis.

Overnight bacterial cultures were grown in LB medium at 37°C for 30 or 60 min, and total RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Midi Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the supplier's instructions. To perform the primer extension analysis, the primer ORF1-PE mapping 34 bp downstream of the ATG start of sepL was end labeled with [γ-32P]dATP at 37°C for 40 min. The labeled primer was hybridized with 25 μg of RNA at 50°C for 20 min and extended with 1 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, Wis.) at 42°C for 40 min (43). The primer extension products were analyzed on a sequencing gel using ladders generated with the same primer and the Deaza G/A T7Sequencing Mixes Kit (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) as a reference.

Construction of a nonpolar mutation.

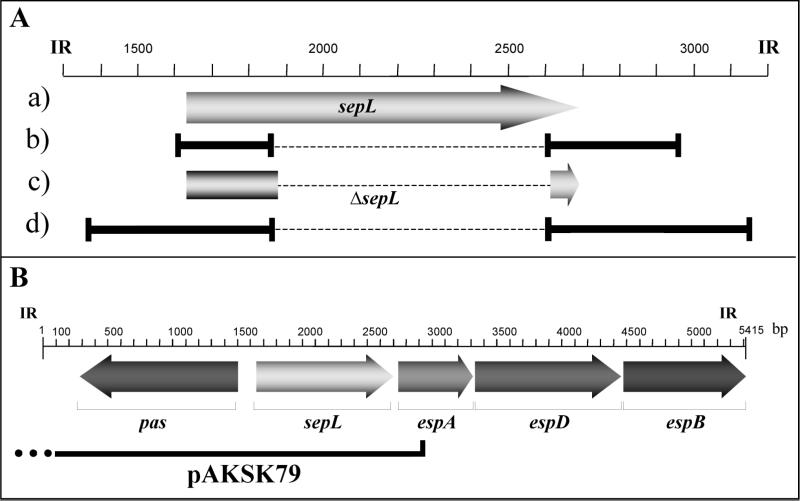

By overlap extension PCR (21), an in-frame deletion in the sepL gene from EHEC strain EDL933 was generated (Fig. 1A). Two PCR fragments were obtained by colony PCR using the Expand High Fidelity kit (Boehringer) with the primer pairs ANKA291 and ANKA292 and ANKA293 and ANKA294. The obtained products were then mixed and used in a second PCR with the primers ANKA291 and ANKA294. The resulting 336-bp fragment contained the first 255 bp and the last 72 bp of the sepL ORF, thereby generating a ΔsepL gene which codes for a polypeptide (108 amino acids [aa] and additionally 3 aa by insertion of a BamHI restriction site) in which 243 aa of the wild-type SepL protein (351 aa) are deleted. After cloning into the vector pCR2.1 and control of the DNA sequence, the ΔsepL fragment was subcloned into KpnI- and XbaI-digested pANK1 (31), thereby generating pANK157. This plasmid was transformed into S17-1 (λpir) and then transferred by conjugation (20) into the recipient EHEC strain E32511/0 Nalr. Plasmid pANK157 was recovered from E32511/0 Nalr and subsequently electroporated into EHEC strain EDL933. The cointegration and excision of the suicide vector were performed as previously described (30). The in-frame deletion contained in the EDL933ΔsepL mutant resulting from the allelic exchange was confirmed by PCR analysis using the primers ANK22 and ANK9952, which are homologous to adjacent external sequences (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Construction of an in-frame deletion mutant of the sepL gene in EHEC. The corresponding positions, according to the published sequence of the intergenic region (IR) between eaeA and espB (EMBL accession number Y13068) are also shown. (A) The ORF of sepL in wild-type EHEC strain EDL933 (a), the PCR products generated for the overlap extension PCR (b), the recombinant ORF of the sepL mutant EDL933ΔsepL (c), and the PCR product generated with ΔsepL by external primers (d) are schematically shown. Dotted lines indicate deleted regions; solid lines and vertical bars indicate PCR products and primer positions, respectively. (B) Position of the fragment contained in pAKSK79 which was used for the complementation studies performed with EHEC strain EDL933ΔsepL.

For complementation studies of the EDL933ΔsepL mutant, a derivative of the plasmid pANK84 (30), which was generated by ExoIII digestion (19) and harbors a region from the 3′ end of the eaeA gene to the 5′ end of the espA gene, was electroporated into EDL933ΔsepL, thereby generating EDL933ΔsepL(pAKSK79) (Fig. 1B).

Production of a SepL-specific antiserum.

The sepL gene was amplified by PCR with the primer pair ANK10 and ANK11. The resulting product was digested with BamHI and KpnI, ligated with predigested pQE30 (Qiagen), and subsequently transformed into E. coli strain M15(pREP4). The resulting pQE30-SepLEE plasmid carries a histidine-tagged SepL fusion protein. Overexpression and purification of the recombinant protein were performed under denaturing conditions in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations (Qiagen). A rabbit was immunized intraperitoneally (100 μg of protein) and given three boosters (EuroGenTec, Seraing, Belgium). After blood collection, the serum containing the SepL-specific antibodies was separated and stored at −20°C. For the purification of SepL-specific antibodies, purified recombinant SepL protein was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane after discontinuous SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transiently stained with Ponceau red solution and the protein band was cut from the membrane. After blocking with 5% (wt/vol) low-fat milk (1.5%) in phosphate-buffered saline for 2 h, the membrane was incubated with the serum overnight at room temperature. The membrane was washed with 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.6, and the bound antibodies were eluted from the membrane by incubation in 1 ml of 0.2 M glycine (pH 2.2). The antibody solution was immediately neutralized with 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.5, and stored in aliquots at −20°C.

Detection of secreted and cellular proteins and cellular fractioning.

Previously described protocols (30, 31) were used to obtain whole-cell extracts, secreted proteins, and bacterial fractions, as well as to perform SDS-PAGE and Western blotting experiments. The EspA, EspB, EspD, Tir, and SepL proteins were detected using mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for EspA (MAb B71), EspB (MAb A289), EspD (MAb-anti-EspD), and Tir (MAb B51) (11, 13, 14, 31) and purified rabbit polyclonal antibodies against SepL (see above) as first antibodies and a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM as secondary antibody (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Antigen-antibody complexes were visualized by chemiluminescence using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Life Science, England).

Tissue culture methods and analysis by immunofluorescence microscopy.

HeLa cells (ATCC CCL2) were maintained, and infection with EHEC was carried out as previously described (30), except that bacteria grown overnight were activated for 3 h at 37°C in DMEM-HEPES immediately before infection. After 4 h of incubation, monolayers were treated as described before (30) and bacteria were stained using a rabbit polyclonal antiserum against O157 K− (Behring, Marburg, Germany), EspA-specific monoclonal antibodies (14), or SepL-specific polyclonal antibodies. After washing, the rabbit antibody was visualized using tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany), EspA filaments were labeled using indiocarbocyanine (Cy5)-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse antibodies (Dianova), and F actin was detected (29) using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated phalloidin (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany). Stained coverslips were washed, mounted, and examined using a Zeiss inverted microscope attached to the Bio-Rad MRC 1024 UV confocal laser microscope (Bio-Rad Laboratories) equipped with an argon-krypton laser with the E2-and-T1 filter set at 488 nm (green channel), 568 nm (red channel), and 647 nm (blue channel).

Quantitative determination of bacterial attachment.

For quantitative determination of bacterial attachment, HeLa cells were grown, infected, and processed as previously described (31). Reported results are mean values of three independent experiments ± standard errors of the means. The statistical significance of the obtained results was evaluated by Student's t test; differences were considered significant at P values of ≤0.05.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of sepL reported here is accessible in the EMBL database under the accession number Y13068 (30).

RESULTS

Sequence and transcriptional analysis of sepL.

sepL of the EHEC strain EDL933 codes for a product of 351 aa with a predicted molecular mass of 39.95 kDa and a pI of 4.7. Analysis using the PSORT and TMPred algorithms did not predict an N-terminal signal sequence or transmembrane regions, respectively. The comparison of SepL from Shiga toxin-producing E. coli and EPEC strains showed that SepL is highly conserved (93.7 to 94.3% identity) among pathogenic E. coli. Homology sequences in databases using the BLASTP + BEAUTY algorithm indicated SsaL from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium as the closest homologue in non-E. coli strains (24.3% identity and 35% similarity). To date, the function of SsaL has not been elucidated.

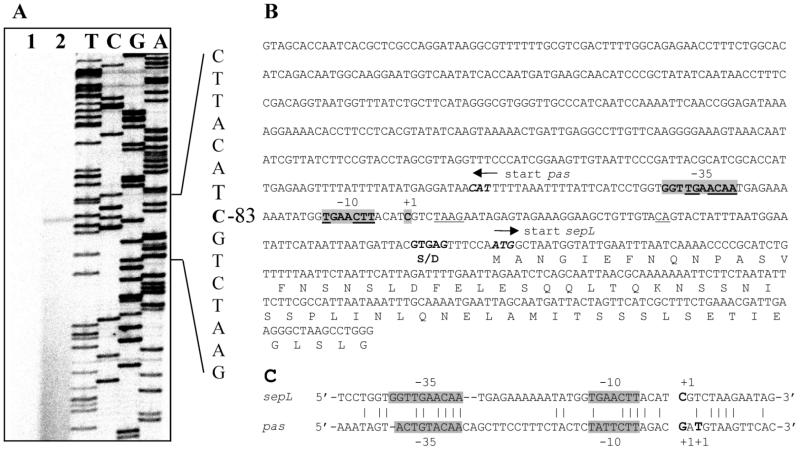

Northern blot analysis of total RNA from EDL933 suggested that the esp genes and sepL are independently transcribed (7). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the detected signals result from the degradation of a major transcript or that under other experimental conditions a cryptic promoter can direct the synthesis of a longer transcript. To further determine the transcriptional start of sepL, primer extension studies were performed using total RNA from EDL933(pUJ2) grown on LB medium at a temperature of 37°C. This allowed us to identify a single start of transcription located 83 bp upstream from the ATG start codon of sepL (Fig. 2). The analysis of the region upstream of the start of transcription led to the identification of promoter sequences between positions −5 and −36 (Fig. 2), which exhibit a high degree of homology to the pas promoter (8). This suggests that common regulatory factors are involved in the activation of these two promoters.

FIG. 2.

(A) Identification of the transcriptional start site from sepL by primer extension analysis. Total RNA was extracted from EDL933(pUJ2) grown in LB medium at 37°C until it reached an OD600 of 0.6. A 24-bp oligonucleotide (ORF1-PE), which hybridizes with positions +35 to +59 with respect to the ATG start codon of the sepL gene, was used to perform the primer extension and to generate a sequence ladder. The position of the first base in the main mRNA relative to the adenosine of the ATG start codon is indicated. (B) Nucleotide sequence of the DNA fragment used to study the transcriptional regulation of the sepL promoter. The start of transcription (+1), the −10 and −35 consensus sequences, and the Shine-Dalgarno sequence (S/D) are shaded or boldfaced. Regions of homology between the −10 and the −35 regions of the sepL and the adjacent pas promoter are underlined. The amino acids of the encoded proteins are indicated in one-letter code. (C) Alignment of the sepL promoter with the pas promoter region. The starts of transcription (+1) and the −35 and −10 regions are indicated above and below the sequences, respectively.

Functional characterization of the sepL promoter.

To further characterize the putative promoter of the sepL gene, a DNA fragment spanning nucleotides −528 to +196 with respect to the sepL ATG start codon of strain EDL933 was amplified by PCR using the primer pair 1627-lac1 and 1627-lac2 and cloned into the plasmid pUJ9TT to generate a translational fusion with the lacZ gene, thereby generating plasmid pUJ2. This fragment was considered sufficiently long to include both the promoter and upstream regions containing potential binding sites for regulatory factors. The translation initiation region was also maintained intact to avoid potential artifacts resulting from an altered translational efficiency (45).

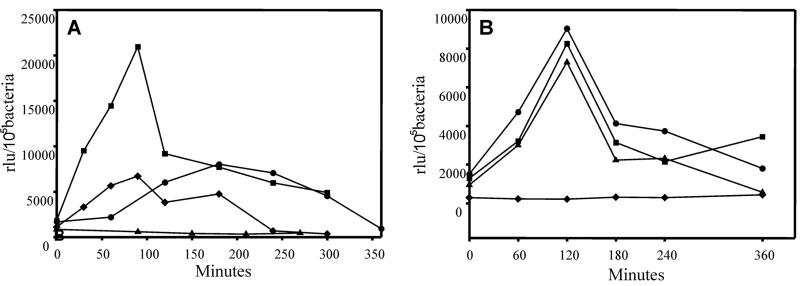

We have recently shown that growth in LB medium can stimulate transcription from both the esp and pas promoters (7, 8). This is probably because bacterial growth in nutrient-rich medium mimics the environmental conditions of the host intestine. To analyze whether this was also true for the sepL promoter, EDL933(pUJ2) was grown in LB medium and DMEM at 37°C, and β-galactosidase activity was measured at different time intervals. While a rapid induction of β-galactosidase activity was observed in the early exponential phase after growth in LB medium, no increase was observed in DMEM (Fig. 3A). This indicates a specific effect of the LB medium in the activation of the sepL promoter. Interestingly, as already observed for the esp and pas promoters, HEPES (100 mM, pH 7) also acted as an inducer for the sepL promoter when added to DMEM (Fig. 3A). Since variations in the pH had no effect by themselves on the activity of the promoter (data not shown), this effect seems to be directly determined by HEPES rather than by the buffering action of this compound.

FIG. 3.

Activation of the sepL promoter in response to different stimuli. (A) EDL933(pUJ2) was grown in LB medium at 25°C (⧫), LB medium at 37°C (■), DMEM alone (▴), or DMEM supplemented with 100 mM HEPES (pH 7) (●). (B) EDL933(pUJ2) was also grown in M9-glucose medium supplemented with MnSO4 at various concentrations. ⧫, 0 mM; ●, 0.0033 mM; ■, 0.33 mM; ▴, 3.3 mM. β-Galactosidase activity was determined at different time intervals. Results are expressed as relative light units (rlu) per 105 bacteria and are means of three independent experiments. Standard deviation was lower than 5%. The background values for EDL933 containing the promoterless plasmid in matching conditions were at least 10-fold lower than the basal values at the tested conditions and were subtracted from each sample.

Micronutrients are known to induce the expression of virulence genes in a wide range of pathogenic microorganisms (reviewed in reference 35). Indeed, Ca2+ and Mn2+ are involved in the transcriptional regulation of the esp operon and the pas gene (7, 8), and the secretion of the Esp proteins is stimulated by the presence of Ca2+ (26). Supplementation of the M9 minimal medium with MnSO4 demonstrated that Mn2+ is able to induce the activity of the sepL promoter (Fig. 3B), whereas no activation was observed in the presence of Ca2+ or at different concentrations of NH4Cl. The activity was only slightly induced by the presence of MgSO4, FeSO4 or Fe(NO3)3, suggesting that these molecules have very little contribution, if any at all, in the activation of the sepL gene (data not shown).

Changes in osmolarity can have a dramatic effect on the activation of different virulence factors (8, 17, 35). Therefore, we analyzed the effect on the induction of the sepL promoter resulting from growing bacteria in minimal medium supplemented with 10 or 430 mM NaCl or sucrose as osmolyte. No significant differences in the production of β-galactosidase were observed during the exponential growth phase, whereas a weak increment was seen in the stationary phase in the high-osmolarity medium (not shown), suggesting that osmolarity does not play a major role by itself in sepL activation.

The first sudden change that enteropathogenic bacteria face when they infect their hosts is the increment in temperature. Previous studies suggested that the expression of components of the EPEC type III secretion system is upregulated at 37°C (25). Therefore, the effect of changes in the growth temperature on the induction of the sepL promoter was analyzed after growth in LB medium. Activation of the sepL promoter was reduced when EDL933(pUJ2) was grown at 25°C (Fig. 3A) with respect to bacteria grown at 37°C. Interestingly, when bacteria were grown at 37°C in high-osmolarity medium (430 mM NaCl), a further increment in the expression of the reporter gene was observed when compared to growth at 25°C (data not shown).

Generation of a sepL deletion mutant.

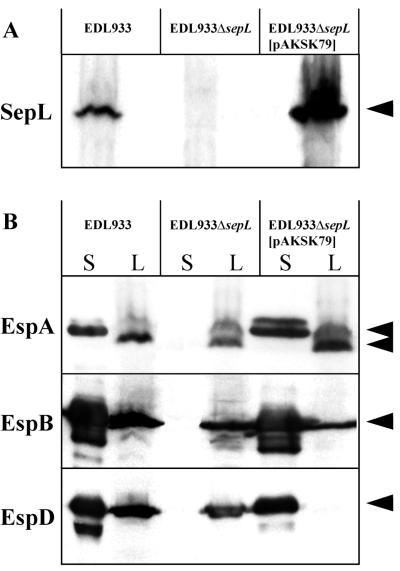

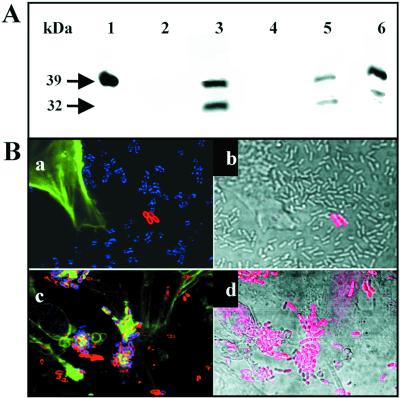

To characterize the role played by SepL in the pathogenicity of EHEC, a mutant (EDL933ΔsepL) that contains an in-frame deletion in the sepL gene (Fig. 1) was generated. The SepL protein was overexpressed, and specific antibodies were raised and purified. Western blot analysis using these polyclonal antibodies allowed us to detect SepL in whole-cell lysates of the wild-type strain but not of the mutant strain (Fig. 4A). In the complemented mutant strain [EDL933ΔsepL(pAKSK79)], SepL was even overexpressed with respect to wild-type bacteria (Fig. 4A). To identify the subcellular localization of the SepL protein, EDL933 cultures were fractionated into supernatants (secreted proteins) and cytoplasmic, periplasmic, inner membrane, and outer membrane fractions, which were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 5A). SepL was detected only in the cytoplasmic and inner and outer membrane fractions (Fig. 5A). The electrophoretic mobility of the major product corresponded to the expected molecular mass of 40 kDa. However, a second signal with a mass of approximately 32 kDa was also observed, suggesting that SepL might be posttranslationally processed (Fig. 5A). No bands were detected in samples obtained from the sepL mutant, indicating the specificity of the antibodies used (not shown). Immunofluorescence studies showed that SepL was associated with the cellular surface of a subset of wild-type strain EDL933 and most of the EDL933ΔsepL(pAKSK79) bacteria (Fig. 5B), whereas no positive signals were obtained when the EDL933ΔsepL mutant was tested (data not shown). The surface localization of SepL was in agreement with the Western blot analysis, demonstrating that a significant portion of the SepL molecules was found associated with the envelope of EDL933.

FIG. 4.

(A) Expression of SepL by the EDL933ΔsepL mutant. The presence of SepL was determined in bacterial culture lysates by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Expression and secretion of Esp proteins by the EDL933ΔsepL mutant. The presence of EspA, EspB, and EspD was determined in bacterial culture lysates and supernatants by Western blotting. S, culture supernatant; L, whole-cell lysate.

FIG. 5.

(A) Subcellular localization of the SepL protein. Bacterial cultures were fractionated, and protein extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE (0.6 μg of protein in lane 1 and 30 μg in all other lanes) and analyzed by immunoblotting using a SepL-specific antiserum. Lane 1, recombinant histidine-tagged SepL protein; lane 2, supernatant fraction; lane 3, cytoplasmic and periplasmic fraction; lane 4, periplasmic fraction; lane 5, inner membrane fraction; and lane 6, outer membrane fraction. The molecular masses of the main protein products are indicated by arrows. (B) Detection of SepL by immunofluorescence microscopy. HeLa cells were infected with EDL933 (a and b) and EDL933ΔsepL(pAKSK79) (c and d) for 4 h. Bacteria were labeled with SepL-specific antibodies (red), EspA was labeled with MAb B71 (blue), and actin was labeled with phalloidin (green). To illustrate the numbers of bacteria which could be labeled with the SepL-specific antiserum, a matching phase-contrast micrograph is also shown (b and d).

Characterization of the sepL deletion mutant strain.

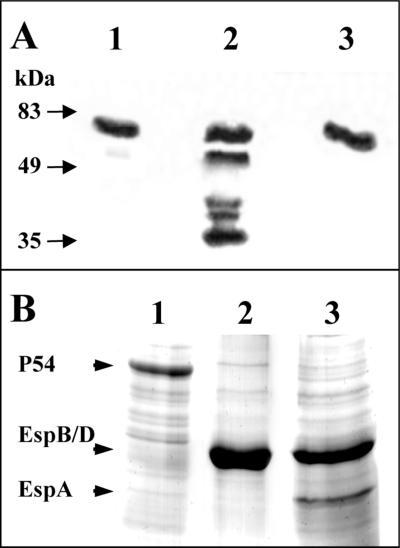

The effect of the deletion in sepL in the expression of secreted proteins was then assessed by Western blot analysis. The mutant harboring the in-frame deletion exhibited an abolished secretion of the EspA, EspD, and EspB proteins, and the wild-type phenotype was completely restored when the sepL gene was provided in trans (Fig. 4B). Since the detected proteins are encoded by a single operon, the secretion of the Tir protein, which is encoded by an ORF located upstream of the eae gene (11, 27), was also analyzed. EDL933 and its ΔespD derivative (as a control) secreted equal amounts of the Tir protein, whereas additional bands characterized by higher electrophoretic mobility were detected only in the EDL933ΔsepL mutant (Fig. 6A). The secretion of Tir rules out the possibility that the expression of the pas gene (30) or the intactness of the type III secretion system can be affected by the deletion of sepL, since this would have resulted in the abrogation of Tir secretion.

FIG. 6.

(A) Secretion of Tir by the EDL933ΔsepL mutant. The presence of Tir was determined by Western blotting in bacterial culture supernatants of EDL933 (lane 1), EDL933ΔsepL (lane 2), and EDL933ΔespD (lane 3). Molecular masses of the protein standard are indicated by arrows. (B) Secretion of a 54-kDa protein by the EDL933ΔsepL mutant. The secretion of proteins into the bacterial culture supernatant was determined by SDS-PAGE and subsequent Coomassie staining. Lane 1, EHEC EDL933ΔsepL; lane 2, EDL933; lane 3, EDL933ΔsepL(pAKSK79). Major proteins are indicated by arrows.

The electrophoretic analysis of supernatant fluids from EDL933 and its sepL derivative confirmed an impaired secretion of the Esp proteins, which was restored in the complemented mutant. Interestingly, the sepL mutant also hypersecreted a protein with an estimated molecular mass of 54 kDa (Fig. 6B). This was true when either equal amounts of proteins or equivalent volumes of culture supernatants were analyzed. To characterize this polypeptide, the corresponding band was excised from the membrane after separation of the supernatant by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nylon membrane and the first 20 N-terminal aa were determined. The sequence obtained, MNIQPTIQSGITSQNNQHHQ, showed no homology to N termini present in current databases.

The EDL933ΔsepL mutant exhibits an impaired attachment to HeLa cells, and sepL is required for actin accumulation underneath adherent bacteria.

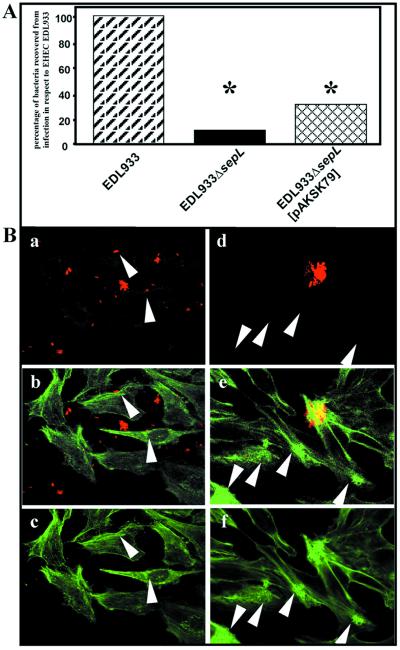

To assess the role played by SepL in the adherence of EHEC strains to epithelial cells, the attachment of the EDL933ΔsepL mutant to HeLa cells was analyzed. The adhesion of EDL933ΔsepL was reduced by 89% from that of the parental strain (Fig. 7A). However, the attachment of EDL933ΔsepL was still significantly higher than that of EDL933 strains carrying mutations in the espA (7) and espD (31) genes. The provision of the full-length sepL gene in trans partially restored the capacity of the mutant to attach to HeLa cells (32% adhesion) when compared to that of the parental strain (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 7.

Interactions of EDL933ΔsepL with HeLa cells. (A) The ability of EDL933ΔsepL and its complementation mutant EDL933ΔsepL(pAKSK79) to attach to HeLa cells after 4 h of infection was analyzed and compared with that of wild-type EDL933. Results are expressed as the percentage of CFU recovered per well with respect to the number of bacteria recovered from cells infected with EDL933 and are mean values of three independent determinations. E. coli strain XL1 blue, used as a control strain, did not attach to HeLa cells (not shown). The differences with the EDL933 strain were statistically significant at P values of ≤0.05 (∗). (B) Analysis of attachment by confocal laser microscopy. HeLa cells were infected with EDL933ΔsepL (a to c) and EDL933ΔsepL(pAKSK79) (d to f) for 4 h. Bacteria were labeled with O157-specific antiserum (a and d), and actin was labeled with phalloidin (c and f). An overlay of actin and O157-specific staining can be seen (b and e). Bacteria which are near host cells but do not induce actin accumulation are shown by arrowheads (a to c), whereas actin accumulation by bacteria that could not be labeled with O157-specific antiserum is indicated by arrows (d to f).

The infection of eukaryotic cells with EDL933 results in the accumulation of actin underneath adherent bacteria, which can be visualized by staining F actin with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled phalloidin. In contrast, the mutant strain EDL933ΔsepL was unable to trigger actin accumulation even when bacteria colocalized with the HeLa cells (Fig. 7B). If the sepL gene in trans under the control of its natural promoter [EDL933ΔsepL(pAKSK79)] was provided, the phenotype of the wild-type strain could be restored (Fig. 7B). This ruled out the possibility that the phenotype of the sepL mutant may be due to an indirect effect resulting from an altered transcription of the esp operon (espA, -D, and -B). Interestingly, a subpopulation of the complemented bacteria could not be properly stained with anti-EHEC serum, resulting in microcolonies which were detectable by phase contrast (not shown) or the typical accumulation of actin (Fig. 7B, arrows). This may be due to the masking of the O antigen by the overexpressed SepL protein. The excess of surface-displayed molecules of SepL may explain, at least in part, the lack of full complementation of the adhesive phenotype observed in the complemented sepL mutant.

DISCUSSION

EPEC and EHEC lead to similar histopathological lesions in infected hosts, although they are targeted to different topologies at intestinal level. The molecular base for the common appearance of the A/E lesions resides in the presence of a common pathogenicity island called LEE (33). The transfer of the LEE from EPEC to a nonpathogenic E. coli K-12 strain is sufficient by itself to confer on the recipient the capacity to cause A/E lesions (34). However, when the LEE from EHEC is transferred to an E. coli K-12 strain, the resulting clone is not able to cause A/E lesions (16). This might be in part due to (i) the lack of essential accessory genes located outside of the LEE in EHEC, (ii) altered biological properties of the encoded products as a result of differences in the coding sequences, or (iii) an altered transcriptional regulation of the virulence factors. Recent studies have suggested that the transcriptional structure of the LEE from EHEC is indistinguishable from that of EPEC (16). However, while Mellies et al. characterized the organization of the LEE in EPEC using different methods for transcriptional analysis (36), the organization of the LEE from EHEC was only predicted by means of sequence analysis (16). Previous work (7) and the data presented here demonstrate that the results of the transcriptional analysis in EHEC contrast with what was observed in EPEC, namely, the presence of two transcriptional units (sepL and the esp operon) in EHEC versus a single transcriptional unit in EPEC called LEE4 (36). This might explain why the Esp proteins are expressed when the LEE of EPEC is transferred to a nonpathogenic E. coli K-12 strain, whereas it does not occur after transfer of the LEE from EHEC.

In this study we investigated the transcription of the sepL gene, which is the first gene downstream of the intimin ORF (eae) with the same orientation. The distance to the start codon of the pas gene from EHEC (designated escD in EPEC), which is located upstream but on the complementary strand (30), is 143 bp. The distance to the espA start codon, which is located immediately downstream of sepL, is 58 bp. Therefore, it has been speculated that sepL might be cotranscribed with the espA, espD, and espB genes (16, 42). However, in the EHEC strain EDL933, the esp and sepL genes seem to be independently transcribed. The promoter elements of sepL have a remarkable similarity to the elements of the pas promoter, suggesting that both genes are transcribed in opposite directions but nevertheless regulated in a similar fashion by a putative common factor. Interestingly, the activation of LEE4 is dependent on a factor that acts in trans, which is not present in EHEC (36). To investigate the transcriptional activity of the sepL promoter, we used lacZ fusions. This analysis revealed that a combination between the physiologic temperature (37°C), high osmolarity, and a rich nutrient environment drives the transcription of sepL. Although nutrient-rich conditions can also be found outside the host, the combination of these different signals seems to be a good indication that the pathogen has reached the right host environment to activate the expression of virulence factors.

The disruption of sepL in EHEC leads to the secretion of an unknown protein (P54), a product which is not encoded by the known sequences of the LEE or the megaplasmid pO157. It would not be surprising if P54 is encoded by a novel chromosomal locus which makes EHEC different from EPEC, as chromosomal variability is a common theme in the dynamic genetics of microbial populations. In fact, a second chromosomal locus was found in EPEC and EHEC, one which is not present in the E. coli K-12 sequence (47), and recently another chromosomal locus, which is essential for the adhesive property of EHEC but is not present in EPEC, was identified (40). Recent studies also support the notion of the existence of different regulators that act in trans on the LEE of EPEC and EHEC (16, 36).

Our results demonstrate that the secretion but not the expression of the EspA, EspD, and EspB proteins is abolished in the ΔsepL derivative of EDL933. On the other hand, the functionality of the type III secretion system is maintained intact, as demonstrated by the continued secretion of the Tir protein. This rules out the possibility that SepL may be involved by itself in the translocation process. A potential explanation for the observed phenotype might be that SepL constitutes an essential chaperon for Esp proteins. However, this seems unlikely since (i) chaperons are generally protein specific rather than universal, (ii) chaperons have been identified for the EspB and EspD proteins (48), and (iii) SepL does not share many of the typical characteristics of chaperons (23, 49). Interestingly, different motifs typical for DNA-binding proteins have been identified in SepL as well as in SsaL. The homology between SepL and SsaL is strengthened by the presence of similar structural properties, such as molecular weights, pI, high numbers of leucine residues, and helix-loop-helix motifs (HLHMs) in the 38-aa N-terminal region, with the loop being a potential turn. However, these motifs do not represent classical helix-turn-helix motifs of DNA-binding proteins, since the turn exceeds 3 aa. HLHMs are present in many eukaryotic regulatory proteins, such as MyoD and Id (9, 38), and seem to be involved in protein dimerization. An N-terminal basic α-helix for DNA binding was not detected in SepL. However, regulatory proteins have been described, which exhibit indirect regulatory functions without a distinctive DNA-binding domain, since the heterodimerization process of HLHM proteins competitively inhibits DNA binding (9). Interestingly, SepL contains a C-terminal HLHM with homology to a conserved motif of the LysR family of regulators. Furthermore, a degenerated leucine zipper motif (LZM), Lx6Lx6Lx6M (positions L212 to M233), was also identified. LZMs are involved in the homo- or heteromerization of DNA-binding proteins and do not necessarily contain leucine but may contain other small hydrophobic residues like methionine (3, 32). When arranged as a helical wheel, the residues of the potential LZM are located opposite positively charged residues, which may serve to stabilize the LZM by generating a hydrophobic interface for interaction of two helices and a hydrophilic outer surface for solubilization of the dimer. In regions upstream from the LZM, two stretches of positively charged residues are observed, which might function as DNA-binding domains (K140K143K147K148K149R152 and K183K185K186K190K192). In this arrangement, four charged regions of a homodimer could establish potential DNA-binding domains. This suggests that SepL might be involved in transcriptional regulation. However, this does not seem to be the case for the espA, -D, and -B genes, since secretion but not expression was affected. Preliminary Southwestern studies also showed that SepL by itself does not bind the esp promoter (data not shown).

Previous reports highlighted the potential role played by a tight coupling between translation and secretion for the export of proteins which are targets of type III secretion systems (5, 6). However, up to now the putative links between translation and secretion have not been found. All in all, the indirect evidence resulting from (i) the presence of nucleic acid-binding motifs in SepL, (ii) the dual topology of this protein (cytoplasm and membrane associated), and (iii) the observed phenotype of the ΔsepL mutant (i.e., affected export but not expression of Esp proteins and the presence of a functional type III secretion system), allow us to hypothesize that SepL might be involved to some extent in the coupling between translation and secretion of some exported proteins. Beyond this functional hypothesis, the infection studies performed here using the ΔsepL mutant clearly demonstrate that abolished production of SepL results in severely impaired bacterial interaction with eukaryotic cells as a result of the blocked secretion of Esp proteins. This confirms for the first time that SepL indeed plays an essential role in the infection process of EHEC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge F. Sasse for his insights on the performance of fluorometry experiments, B. Karge for excellent technical help, and K.N. Timmis for his generous support and encouragement.

Part of this work was supported by a grant from the Lower Saxony-Israel Cooperation Program funded by the Volkswagen Foundation (21.45-75/2).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe A, Kenny B, Stein M, Finlay B B. Characterization of two virulence proteins secreted by rabbit enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, EspA and EspB, whose maximal expression is sensitive to host body temperature. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3547–3555. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3547-3555.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agin T S, Cantey J R, Boedeker E C, Wolf M K. Characterization of the eaeA gene from rabbit enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strain RDEC-1 and comparison to other eaeA genes from bacteria that cause attaching-effacing lesions. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;144:249–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberts B, Bray D, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Watson J D. Molecular microbiology of the cell. 3rd ed. Weinheim, Germany: VCH; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson D A, Schneewind O. A mRNA signal for the type III secretion of Yop proteins by Yersinia enterocolitica. Science. 1997;278:1140–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson D A, Schneewind O. Yersinia enterocolitica type III secretion: an mRNA signal that couples translation and secretion. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1139–1148. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beltrametti F, Kresse A U, Guzmán C A. Transcriptional regulation of the esp genes of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3409–3418. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3409-3418.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beltrametti F, Kresse A U, Guzmán C A. Transcriptional regulation of the pas gene of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;184:119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benezra R, Davis R L, Lockshon D, Turner D L, Weintraub H. The protein Id: a negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell. 1990;61:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyce T G, Swerdlow D L, Griffin P M. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:364–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508103330608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deibel C, Krämer S, Chakraborty T, Ebel F. EspE, a novel secreted protein of attaching and effacing bacteria, is directly translocated into infected host cells where it appears as a tyrosine-phosphorylated 90 kDa protein. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:463–474. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Lorenzo V, Eltis L, Kessler B, Timmis K N. Analysis of Pseudomonas gene products using lacIq/Ptrp-lac plasmids and transposons that confer conditional phenotypes. Gene. 1993;123:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebel F, Deibel C, Kresse A U, Guzmán C A, Chakraborty T. Temperature- and medium-dependent secretion of proteins by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4472–4479. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4472-4479.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebel F, Podzadel T, Rohde M, Kresse A U, Kramer S, Deibel C, Guzmán C A, Chakraborty T. Initial binding of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli to host cells and subsequent induction of actin rearrangements depend on filamentous EspA-containing surface appendages. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:147–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott S J, Wainwright L A, McDaniel T K, Jarvis K G, Deng Y K, Lai L C, McNamara B P, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. The complete sequence of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) from enteropathogenic E. coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott S J, Yu J, Kaper J B. The cloned locus of enterocyte effacement from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 is unable to confer the attaching and effacing phenotype upon E. coli K-12. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4260–4263. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4260-4263.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finlay B B, Falkow S. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:136–169. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.136-169.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin P M, Tauxe R V. The epidemiology of infections caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7, other enterohemorrhagic E. coli, and the associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Epidemiol Rev. 1991;13:60–98. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henikoff S. Unidirectional digestion with exonuclease III creates targeted breakpoints for DNA sequencing. Gene. 1984;28:351–359. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho S N, Hunt H D, Horton R M, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofmann K, Stoffel W. TMbase: a database of membrane spanning protein segments. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1993;374:166. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hueck C J. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:379–433. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.379-433.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jungnitz H, West N P, Walker M J, Chhatwal G S, Guzmán C A. A second two-component regulatory system of Bordetella bronchiseptica required for bacterial resistance to oxidative stress, production of acid phosphatase, and in vivo persistence. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4640–4650. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4640-4650.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenny B, Finlay B B. Protein secretion by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is essential for transducing signals to epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7991–7995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenny B, Lai L C, Finlay B B, Donnenberg M S. EspA, a protein secreted by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, is required to induce signals in epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:313–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenny B, De Vinney R, Stein M, Reinsheid D J, Frey E A, Finlay B B. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) transfers its receptor for intimate adherence to mammalian cells. Cell. 1997;91:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knutton S, Rosenshine I, Pallen M J, Nisan I, Neves B C, Bain C, Wolff C, Dougan G, Frankel G. A novel EspA-associated surface organelle of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli involved in protein translocation into epithelial cells. EMBO J. 1998;17:2166–2176. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knutton S, Baldwin T, Williams P H, McNeish A S. Actin accumulation at sites of bacterial adhesion to tissue culture cells: basis of a new diagnostic test for enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1290–1298. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1290-1298.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kresse A U, Schulze K, Deibel C, Ebel F, Rohde M, Chakraborty T, Guzmán C A. Pas, a novel protein required for protein secretion and attaching and effacing activities of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4370–4379. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4370-4379.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kresse A U, Rohde M, Guzman C A. The EspD protein of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli is required for the formation of bacterial surface appendages and is incorporated in the cytoplasmic membranes of target cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4834–4842. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4834-4842.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landschulz W H, Johnson P F, McKnight S L. The Leucine zipper: a hypothetical structure common to a new class of DNA binding proteins. Science. 1988;240:1759–1764. doi: 10.1126/science.3289117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDaniel T K, Jarvis K G, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1664–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDaniel T K, Kaper J B. A cloned pathogenicity island from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli confers the attaching and effacing phenotype on E. coli K-12. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:399–407. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2311591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mekalanos J J. Environmental signals controlling expression of virulence determinants in bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.1-7.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mellies J L, Elliott S J, Sperandio V, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. The Per regulon of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: identification of a regulatory cascade and a novel transcriptional activator, the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE)-encoded regulator (Ler) Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:296–306. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moon H V, Whipp S C, Argenzio R A, Levine M M, Ginnella R A. Attaching and effacing activities of rabbit and human enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in pig and rabbit intestines. Infect Immun. 1983;41:1340–1351. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.3.1340-1351.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murre C, McCaw P S, Baltimore D. A new DNA binding and dimerization motif in immunoglobulin enhancer binding, daughterless, MyoD, and myc proteins. Cell. 1989;56:777–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakai K, Kanehisa M. Expert system for predicting protein localization sites in gram-negative bacteria. Proteins. 1991;11:95–110. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nicholls L, Grant T H, Robins-Browne R M. Identification of a novel genetic locus that is required for in vitro adhesion of a clinical isolate of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli to epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:275–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Brien A D, Lively T A, Chen M E, Rothman S W, Formal S B. Escherichia coli O157–H7 strains associated with haemorrhagic colitis in the United States produce a Shigella dysenteriae 1 (SHIGA) like cytotoxin. Lancet. 1983;i:702. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91987-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perna N T, Mayhew G F, Posfai G, Elliott S, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B, Blattner F R. Molecular evolution of a pathogenicity island from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3810–3817. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3810-3817.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scaletsky I C, Silva M L, Trabulsi L R. Distinctive patterns of adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1984;45:534–536. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.2.534-536.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schauder B, McCarthy J E G. The role of basis upstream of the Shine-Dalgarno region and in the coding sequence in the control of gene expression in Escherichia coli: translation and stability of mRNAs in vivo. Gene. 1989;78:59–72. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith R F, Wiese B A, Wojzynski M K, Davison D B, Worley K C. BCM Search Launcher—an integrated interface to molecular biology data base search and analysis services available on the World Wide Web. Genome Res. 1996;6:454–462. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.5.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tobe T, Tatsuno I, Katayama E, Wu C Y, Schoolnik G K, Sasakawa C. A novel chromosomal locus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC), which encodes a bfpT-regulated chaperone-like protein, TrcA, involved in microcolony formation by EPEC. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:741–752. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wainwright L A, Kaper J B. EspB and EspD require a specific chaperone for proper secretion from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1247–1260. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wattiau P, Woestyn S, Cornelis G R. Customized secretion chaperones in pathogenic bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:255–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willshaw G A, Smith H R, Scotland S M, Rowe B. Cloning of genes determining the production of Vero cytotoxin by Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:3047–3053. doi: 10.1099/00221287-131-11-3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woodcock D M, Crowther P J, Doherty J, Jefferson S, DeCruz E, Noyer Weidner M, Smith S S, Michael M Z, Graham M W. Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:3469–3478. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.9.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Worley K C, Wiese B A, Smith R F. BEAUTY: an enhanced BLAST-based search tool that integrates multiple biological information resources into sequence similarity search results. Genet Res. 1995;5:173–184. doi: 10.1101/gr.5.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]