Abstract

The Escherichia coli chromosomal determinant for tellurite resistance consists of two genes (tehA and tehB) which, when expressed on a multicopy plasmid, confer resistance to K2TeO3 at 128 μg/ml, compared to the MIC of 2 μg/ml for the wild type. TehB is a cytoplasmic protein which possesses three conserved motifs (I, II, and III) found in S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM)-dependent non-nucleic acid methyltransferases. Replacement of the conserved aspartate residue in motif I by asparagine or alanine, or of the conserved phenylalanine in motif II by tyrosine or alanine, decreased resistance to background levels. Our results are consistent with motifs I and II in TehB being involved in SAM binding. Additionally, conformational changes in TehB are observed upon binding of both tellurite and SAM. The hydrodynamic radius of TehB measured by dynamic light scattering showed a ∼20% decrease upon binding of both tellurite and SAM. These data suggest that TehB utilizes a methyltransferase activity in the detoxification of tellurite.

Tellurite (TeO32−) resistance, which is found in many microorganisms (37), is carried on plasmids of IncHI, IncHII, and IncP incompatibility groups (3, 36, 39) and/or on chromosomes (9, 10, 29, 33). Tellurite resistance (Ter) determinants are very diverse, and at least five different determinants have been identified (37). Ter determinants are unrelated, and probably different resistance mechanisms are involved. Except for that encoded by the Pseudomonas syringae tpm gene, Ter mechanisms are not clearly understood. tpm encodes a methyltransferase that catalyzes S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) methylation of 6-mercaptopurine, a substrate for human thiopurine methyltransferase. It was assumed that tellurite is also a substrate for this enzyme (11).

The Ter determinant tehAB, an operon located at 32.3 min on the Escherichia coli K-12 chromosome (38), encodes proteins of 330 (TehA) and 197 (TehB) amino acids. TehA is a membrane protein with 10 transmembrane segments, whereas TehB is a soluble protein. The closest homologues of these two genes are found in Haemophilus influenzae (15).

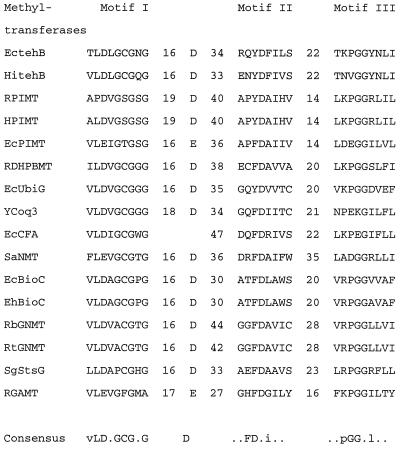

A sequence search performed with the BLAST program (National Center for Biotechnology Information), followed by alignment analysis with the Genetics Computer Group software package (University of Wisconsin) (12), demonstrated that TehB displays some amino acid sequence similarity to many SAM-dependent non-nucleic acid methyltransferases. These proteins have three shared motifs, and the TehB proteins show homologies within all regions with comparable sequence interval distances (Fig. 1). Motif I is a glycine-rich region agreeing well with the consensus sequence h(D/E)hGxGxG, where h represents a hydrophobic residue and x is any residue (27, 46). Motif I is generally followed by an acidic residue on the C-terminal side, about 17 to 19 residues from the motif (27). In TehB, there are 16 residues before this aspartate (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Alignment of sequences of E. coli TehB, H. influenzae TehB, and some non-nucleic acid methyltransferases to demonstrate the three motifs. The three homologous regions (motifs) of the methyltransferases are shown in the one-letter amino acid code. The numbers represent the residue number spacings between the motifs. The sequences are from the National Center for Biotechnology Information database. The names are abbreviated, and their accession numbers are in parentheses. EctehB, protein encoded by E. coli tellurite resistance gene tehB (M38696); HitehB, protein encoded by an H. influenzae tellurite resistance gene tehB homologue (U32807); RPIMT, rat protein l-isoaspartyl carboxyl methyltransferase (D11475); HPIMT, human protein l-isoaspartyl carboxyl methyltransferase (P22061); EcPIMT, E. coli protein l-isoaspartyl carboxyl methyltransferase (P24206); RDHPBMT, rat dihydroxypolyprenylbenzoate methyltransferase (L20427); EcUbiG, E. coli ubiquinone biosynthesis-related protein (M87509); YCoq3, Saccharomyces cerevisiae 3,4-dihydroxy-5-hexaprenylbenzoate methyltransferase (M73270); EcCFA, E. coli cyclopropane fatty acid synthetase (M98330); SaNMT, Streptomyces anulatus N-methyltransferase (X92429); EcBioC, E. coli biotin synthesis protein (P12999); EhBioC, Erwinia herbicola biotin synthesis protein; RbGNMT, rabbit glycine N-methyltransferase (D13307); RtGNMT, rat glycine N-methyltransferase (X06150); SgStsG, Streptomyces griseus methyltransferase involved in the N-methyl-l-glucosamine pathway (Y08763); RGAMT, rat guanidinoacetate methyltransferase (J03588).

Thirty-four residues downstream from motif I is motif II, which comprises 8 residues. Motif II is unusually rich in aromatic amino acids (Tyr, Trp, and Phe), which are located around a central invariant aspartate residue (27). Aromatic rings are considered to be involved in binding SAM through cation-quadrapole interactions with the positively charged sulfonium moiety of SAM (13, 31). The importance of tyrosine in motif II of rat guanidinoacetate methyltransferase (RGAMT) has already been demonstrated (22). In TehB, four aromatic residues were found in this region; they are Phe (−5 position with respect to Asp), Tyr (−1), Phe (+1), and Phe (+10). Motif III is 22 residues away from motif II and consists of a 9-residue block. In the middle of the block are two highly conserved Gly residues. Motif III is consistent with the consensus sequence L(R/K)PGG(R/I/J)(L/I)(L/F/I)(I/L) (25, 27). However, the significance of motif III in methyltransferases has been questioned, because site-directed mutagenesis of several residues of RGAMT motif III minimally affected enzymatic activity (19).

To date, crystal structures of six methyltransferases have been elucidated; four are DNA methyltransferases: HhaI DNA methyltransferase (M.HhaI) (7), TaqI methyltransferase (M.TaqI) (30), HaeIII methyltransferase (M.HaeIII) (34), and PvuII methyltransferase (M.PvuII) (20). Two are small-molecule methyltransferases: catechol O-methyltransferase (45) and glycine N-methyltransferase (17). Generally DNA and RNA methyltransferases lack motifs II and III of the non-nucleic acid methyltransferases but possess a glycine-rich sequence which shows a weak resemblance to motif I (25, 27). Despite the low degree of sequence similarity among these six enzymes, the tertiary structures of their SAM-binding domains are strikingly similar, suggesting that many (if not all) methyltransferases may have a common structure for SAM binding (8, 17, 35). Escherichia coli TehB exhibits sequence similarities to all three motifs of glycine N-methyltransferase (Fig. 1); thus, it is likely that TehB has a similar SAM-binding site.

To determine if the SAM-binding motifs in TehB are involved in tellurite resistance, we performed site-directed mutagenesis on two aspartate residues in motif I and on three residues in motif II (Table 1). Mutagenesis was performed by the two-stage PCR-based overlapping extension method (23). MICs were determined as previously described (42) with the tehAB operon expressed from pTWT101, a pTZ19R (47) clone, in E. coli JM109. The MICs of K2TeO3 for all three motif I mutants and two motif II mutants (Phe98Tyr and Phe98Ala) were reduced to 2 μg/ml from 128 μg/ml. The Tyr96Ala and Asp97Asn mutations had only a partial effect on tellurite resistance, whereas Asp97Glu had no effect. The drop in MIC was not due to decreased expression of the mutants since sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) showed that the level of expression of mutant TehB proteins was similar to that of the wild type (data not shown). These results suggest that motifs I and II in E. coli TehB, like those that play a direct role in SAM binding in other non-nucleic acid methyltransferases, are directly involved in TehB's role in tellurite resistance.

TABLE 1.

Tellurite resistance encoded by plasmids with mutations in TehB methyltransferase

| Mutation or plasmid | MICa (μg of K2TeO3/ml) | Motif containing mutationb |

|---|---|---|

| pTWT101c | 128 | |

| pTZ19Rd | 2 | |

| Asp36Ala | 2 | I |

| Asp36Asn | 2 | I |

| Asp59Ala | 2 | I |

| Tyr96Ala | 16 | II |

| Asp97Glu | 128 | II |

| Asp97Asn | 64 | II |

| Phe98Tyr | 2 | II |

| Phe98Ala | 2 | II |

MICs were measured several times with no variation in the resistance end points.

See Fig. 1 for motifs in methyltransferase proteins.

Positive control with wild-type tehAB expressed on a multicopy plasmid.

Negative control with vector lacking tehAB.

To further assess whether TehB possesses SAM-binding ability, we performed in vitro experiments on purified TehB. The coding sequence for E. coli TehB was cloned by PCR which allowed for insertion of an N-terminal His6 fusion construct into the vector pRSETC (Invitrogen), resulting in pTWT124. E. coli C41(DE3) (32), a derivative of BL21(DE3) (hsdS gal λcIts857 ind1 Sam7 nin5 lacUV5-T7 gene 1) was found to be the best expression host for the purification of His6-TehB. Growth conditions, time of induction, and harvest were optimized to achieve the highest possible level of accumulation of soluble protein. As much as 90% of the total TehB was lost in the low-speed-centrifugation pellet as inclusion bodies depending on the method and host chosen. The best conditions involved addition of a 2% inoculant of overnight culture into 1 liter of Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and growth for 3 h at 37°C. After the 3-h time period (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], ∼0.5), IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added to 0.5 mM and the culture was incubated for another 3 h. Cells were harvested at 5,500 × g for 10 min, resuspended in 50 ml of buffer (50 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [MOPS; pH 7.5], 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]) per liter of culture, and repelleted at 5,500 × g for 10 min. The cell pellet was resuspended (1 ml of buffer per 0.5 g of paste), and the cells were lysed by two passages through a French pressure cell (16,000 lb/in2). Unbroken cells and cellular debris were removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min.

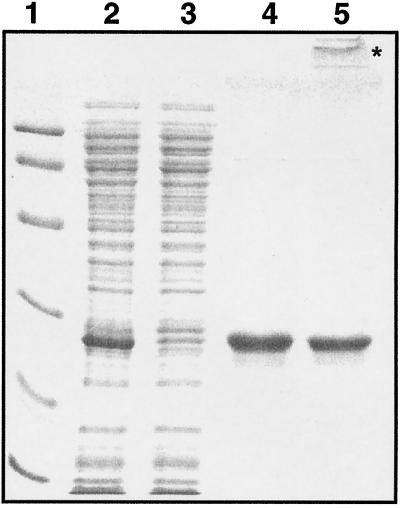

To purify the His6-TehB, a 2.5-ml column bed of Superflow nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Qiagen) was poured and equilibrated with buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4 [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole), and 2 to 3 ml of the cell extract was loaded. An equimolar amount of MgCl2 was added to the cell extract to coordinate the EDTA of the lysis buffer. The column was washed with 10 bed volumes of wash buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4 [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole); His6-TehB was eluted with 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 8.0)–300 mM NaCl–250 mM imidazole, and 1-ml fractions were collected. All fractions were electrophoresed on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel, and purity was evidenced as a single band stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G250 and R250 (Fig. 2). Fractions with the highest TehB content and purity were pooled, and the A280 of the pooled fractions was measured. The concentration was estimated by using an ɛ280 of 12,000 M−1 cm−1 for TehB.

FIG. 2.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of the purification of E. coli TehB. Lane 1, protein molecular size standards with molecular masses of (from top to bottom) 97.4, 66.2, 45.0, 31.0, 21.5, and 14.4 kDa; lane 2, cell extract of induced E. coli C41(DE3)/pTWT124; lane 3, cell extract of uninduced E. coli C41(DE3)/pTWT124; lane 4, freshly purified TehB from the nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity resin; lane 5, TehB after storage at 4°C for 2 weeks, showing the presence of a high-molecular-mass aggregate protein (∗).

The protocol described above affords the production of ∼3 mg of pure soluble protein per liter of culture. The pure TehB was found to be unstable under conditions of low ionic strength and formed insoluble aggregates (Fig. 2, lane 5) upon freezing, dialysis, extended storage (more than 1 week), or concentrating (to >10 mg/ml). Therefore, all enzymatic and biophysical studies were carried out within 1 day of purification.

The hydrodynamic radius (Rh) of TehB was studied by dynamic light scattering (DLS) in the presence and absence of SAM and TeO32−. Enzymes generally undergo conformational changes upon substrate binding, thereby trapping substrates and positioning key active-site residues and substrates for catalysis. Such conformational changes are often reflected by changes in the Rh, which can readily be detected by DLS. Therefore, we employed this technique to identify whether TehB does indeed bind SAM and/or tellurite.

DLS was performed in a DynaPro-MSTC dynamic light-scattering instrument (Protein Solutions Inc.). Protein samples were analyzed for their translational diffusion coefficient (DT), which, assuming Brownian motion, was translated, using the Stokes-Einstein equation, to the Rh. Measurements of complexes of TehB with TeO32− and SAM were obtained for 1.5- to 4.0-mg/ml protein solutions incubated with 1 mM SAM and 3 mM K2TeO3, providing at least a 100-fold molar excess of each ligand. Experiments were performed at least three times for different protein expression-purification trials, and each measurement was performed 50 times, with the results being analyzed by using the DYNALS software package. The mean Rh ± standard deviation in phosphate buffer, with or without TeO32− or SAM, was 3.21 ± 0.02 nm. Addition of both TeO32− and SAM gave an Rh of 2.59 ± 0.02 nm.

The sample was not found to be perfectly monodispersed. Although a single, well-defined major species was observed in all experiments, a small amount of a heterogeneous high-molecular-weight aggregate was also observed in all of the samples analyzed. The contributions of the aggregate increased with increased storage time (over weeks), further demonstrating the instability and propensity of this protein to aggregate (Fig. 2). Various buffers and buffer additives (such as glycerol and detergents) helped to diminish this aggregation but did not completely resolve it. These problems likely reflect the localization of TehB as a peripheral membrane protein; as such, it probably interacts with the integral membrane protein TehA. Since freshly purified samples were practically devoid of aggregate, they were always used in the DLS studies.

The calculated formula mass of the His6-tagged TehB is 26,256 Da, and it migrates on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel to a position corresponding to between 27 and 28 kDa. The observed Rh of 3.21 nm relates to a molecular mass of 49.0 kDa assuming that the protein is in the shape of a sphere. This suggests that TehB is a dimer. Although no significant change in Rh was observed when SAM or tellurite was added individually, when the two were added simultaneously the Rh was reduced to 2.6 nm, which correlates with a molecular mass of ∼29.1 kDa. This indicates that there is on the order of a 20% change in TehB molecular free volume upon cofactor-ligand binding. Alternatively, the protein may become a monomer in the presence of SAM and tellurite. These experiments provide evidence that TehB is a SAM- and TeO32−-binding protein and that a SAM-dependent activity forms part of the Ter mechanism.

SAM binding mutants of TehB were also PCR subcloned and purified, using His6 tagging in the same fashion as was done for the wild type. Although no difference in size or shape and no effect of SAM addition on conformation change were expected, the mutant TehB(Phe98Tyr) produced unexpected results. We observed Rh values ranging from 6.1 to 7.5 nm for TehB(Phe98Tyr), which suggests that this particular mutant either is more susceptible to aggregation or oligomerizes into a decamer. The other mutants showed no change with SAM and tellurite binding, which is in agreement with studies of motifs I and II of a rat non-nucleic acid methyltransferase examined by a variety of spectroscopic methods (22). The study observed only minor conformational changes with mutations to key residues and concluded that the SAM-binding site has strict residue requirements.

To determine if the shape change was a general effect of tellurite-SAM addition, a control protein that had been purified in a similar manner was chosen at random. The periplasmic siderophore-binding protein FepB, which has a molecular weight similar to that of TehB, was used. Although a slight change in the Rh was observed upon addition of tellurite alone, no change was observed when SAM and tellurite were added together.

Evidence for a SAM-dependent enzymatic reaction of TehB with tellurite was explored. No volatile tellurium compounds were observed in the head gas of cultures exposed to tellurite (R. J. Turner, V. Van Fleet-Stalder, and T. G. Chasteen, unpublished results). Therefore, the final product is likely more complex than a simple methylated telluride. Because the product of the reaction is unknown at this time, only the loss of substrate could be monitored. Two different assays were developed to examine the SAM-dependent loss of TeO32−. Sodium diethyl dithiocarbamate (DDTC) has been successfully utilized to measure TeO32− levels in bacterial cultures (44). The assay was modified to measure tellurite in buffered solutions. A typical assay mixture consisted of 780 μl of 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10 μl of a 200-mg/ml solution of SAM, 10 μl of a ∼1-mg/ml solution of TehB, and 100 μl of K2TeO3 (10 to 10,000 μmol; added at time zero). Samples were incubated for 30 min at 37°C, after which 100 μl of 10 mM DDTC was added to each. The mixtures were allowed to incubate a further 5 min at 37°C, and the A340s were recorded (ɛ340 = 3.04 × 102 M−1 cm−1), allowing for the determination of any TeO32− remaining.

The second procedure involved the reaction of tellurite with DTT followed by assessment of the remaining DTT with dithionitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) as a coupled assay. DTT becomes oxidized by tellurite in a 1:1 molar ratio, and DTNB reacts with DTT in a 2:1 molar ratio. The reaction mixture consisted of 2.4 ml of 50 mM MOPS (pH 7.5), 30 μl of a 1-mM solution of SAM, and 30 μl of a 1-mg/ml TehB solution. At time zero, 300 μl of 0.03 mM K2TeO3 was added, and 400-μl aliquots were removed at regular time intervals for 30 min. After addition of 50 μl of 0.1 mM DTT to each of these aliquots, mixing, and a 1-min incubation, 50 μl of 1 mM DTNB was added to each sample. The A412 of each sample was recorded, and the concentration of reduced DTT (ɛ412 = 1.36 × 104 M−1 cm−1), which is related to the number of moles of TeO32− remaining in the reaction after incubation, was determined.

Although neither of these assays is ideal for examination of the enzymology of TehA and TehB, it was possible to observe a SAM-dependent loss of tellurite on the order of 350 nmol of TeO32−/mg of TehB/min.

Microbial methylation of metalloids to yield various organoderivatives is a well-known phenomenon. The methylated derivatives are typically quite volatile, which provides a means of removing the toxicant. Many bacteria and fungi, and even the protozoan Tetrahymena thermophila, have been found to methylate arsenic compounds (24, 41) and selenium compounds (4, 18, 40), as well as antimony compounds (21, 26) and sulfide (14). While much less work has been done on tellurium methylation, it has been observed that both fungi and bacteria are capable of methylating tellurium compounds. For example, several Penicillium strains (P. brevicaule, P. chrysogenum, and P. notatum) and the bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens were found to produce dimethyltelluride [Te(CH3)2] (2, 6, 16). In addition, the fungi Acremonium falciforme and Penicillium citrinum produce both Te(CH3)2 and dimethylditelluride [Te2(CH3)2] as well as another, unknown compound (6). A Penicillium sp. isolated from evaporation pond water was also capable of yielding Te(CH3)2 and Te2(CH3)2 (24). After administration of tellurium compounds to rats and dogs (28), guinea pigs (1), and ducks (5), a garlic-like breath odor was noted. In these reports, Te2(CH3)2 was considered to be the odorous ingredient, although other compounds of tellurium, selenium, and sulfur also have this property. A study of a nonhomologous tellurite resistance gene (tpm) from Pseudomonas syringae pathovar pisi provided evidence that methylation might be involved in tellurite resistance (11). The chemical nature of the methylated tellurium product was not determined in this study. It is possible that methylation of tellurium compounds is a widespread phenomenon in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms.

Since TehB likely has a methyltransferase activity, a detoxification mechanism for tellurite resistance by tehAB is a logical inference. The chemical modification of TeO32− with methyl groups would provide a means for detoxification. However, it is clear that in our case the final product of the reaction is not a volatile form of methylated tellurium. A detoxification mechanism is supported by tellurite accumulation experiments. The tehAB determinant was found to continuously remove tellurite from the growth medium, whereas other Ter determinants would more rapidly become saturated (43). Such an observation is consistent with the occurrence of a modification to tellurite within the cell.

Acknowledgments

D.E.T. thanks M. Rooker and L.W.T. thanks D. Dougan for technical assistance. We also thank Verena Van Fleet-Stalder and Thomas G. Chasteen from the Department of Chemistry, Sam Houston State University, for attempting to detect volatile tellurium compounds in cultures expressing TehB.

This work was supported by a grant (MT6200) from the Medical Research Council of Canada to D.E.T. L.W.T. is a Fellow and D.E.T. is a Scientist of the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amdur M L. Tellurium dioxide, an animal study in acute toxicity. AMA Arch Ind Health. 1958;17:665–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bird M L, Challenger F. The formation of organo-metalloidal and similar compounds by micro-organisms. II. Dimethyltelluride. J Chem Soc. 1939;1939:163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley D E. Detection of tellurite-resistance determinants in IncP plasmids. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:3135–3137. doi: 10.1099/00221287-131-11-3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brady J M, Tobin J F, Gadd G M. Volatilization of selenite in an aqueous medium by a Penicillium species. Mycol Res. 1996;100:955–961. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlton W W, Kelly W A. Tellurium toxicosis in Pekin ducks. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1967;11:203–214. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chasteen T G, Silver G M, Birks J W, Fall R. Fluorine-induced chemiluminescence detection of biologically methylated tellurium, selenium and sulfur compounds. Chromatographia. 1990;30:181–185. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng X, Kumar S, Posfai J, Pflugrath J W, Roberts R J. Crystal structure of the HhaI methyltransferase complexed with S-adenosyl-l-methionine. Cell. 1993;74:299–307. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90421-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng X. Structure and function of DNA methyltransferases. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1995;24:293–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.24.060195.001453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiong M, González E, Barra R, Vásquez C. Purification and biochemical characterization of tellurite-reducing activities from Thermus thermophilus HB8. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3269–3273. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3269-3273.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiong M, Barra R, González E, Vásquez C. Resistance of Thermus spp. to potassium tellurite. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:610–612. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.2.610-612.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cournoyer B, Watanabe S, Vivian A. A tellurite-resistance genetic determinant from phytogenetic pseudomonads encodes a thiopurine methyltransferase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1379:162–168. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dougherty D A, Stauffer D A. Acetylcholine binding by a synthetic receptor: implications for biological recognition. Science. 1990;250:1558–1560. doi: 10.1126/science.2274786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drotar A, Fall L R, Mishalanie E A, Tavernier J E, Fall R. Enzymatic methylation of sulfide, selenide, and organic thiols by Tetrahymena thermophila. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2111–2118. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.9.2111-2118.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, McKenney K, Sutton G, Fitzhugh W, Fields C, Gocayne J D, Scott J, Shirley R, Liu L-I, Glodek A, Kelley J M, Weidman J F, Phillips C A, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M D, Utterback T R, Hanna M C, Nguyen D T, Sandek D M, Brandon R C, Fine L D, Fritchman J L, Fuhrmann J L, Geoghagan N S M, Gnehm C L, McDonald L A, Small K V, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Venter J C. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1997;269:495–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming R W, Alexander M. Dimethylselenide and dimethyltelluride formation by a strain of Penicillium. Appl Microbiol. 1972;24:424–429. doi: 10.1128/am.24.3.424-429.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu Z, Hu Y, Konishi K, Takata Y, Ogawa H, Gomi T, Fujioka M, Takusagawa F. Crystal structure of glycine N-methyltransferase from rat liver. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11985–11993. doi: 10.1021/bi961068n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gharieb M M, Wilkinson S C, Gadd G M. Reduction of selenium oxyanions by unicellular, polymorphic and filamentous fungi: cellular location of reduced selenium and implications for tolerance. J Ind Microbiol. 1995;14:300–311. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomi T, Tanihara K, Date T, Fujioka M. Rat guanidinoacetate methyltransferase: mutation of amino acids within a common sequence motif of mammalian methyltransferase does not affect catalytic activity but alters proteolytic susceptibility. Int J Biochem. 1992;24:1639–1649. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(92)90182-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong W, O'Gara M, Blumenthal R M, Cheng X. Structure of PvuII DNA-(cytosine N4) methyltransferase, an example of domain permutation and protein fold assignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2702–2715. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.14.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurleyuk H, Van Fleet-Stalder V, Chasteen T G. Confirmation of the biomethylation of antimony compounds. Appl Organomet Chem. 1997;11:471–483. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamahata A, Takata Y, Gomi T, Fujuoka M. Probing the S-adenosylmethionine site of rat guanidinoacetate methyltransferase: effect of site-directed mutagenesis of residues that are conserved across mammalian non-nucleic acid methyltransferase. Biochem J. 1996;317:141–145. doi: 10.1042/bj3170141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho S N, Hunt H D, Horton R M, Pullen J K. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huysmans K D, Frankenberger W T. Evolution of trimethylarsine by a Penicillium sp. isolated from agricultural evaporation pond water. Sci Total Environ. 1991;105:13–28. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(91)90326-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingrosso D, Fowler A V, Bleibaum J, Clarke S. Sequence of the d-aspartyl/l-isoaspartyl protein methyltransferase from human erythrocytes. Common sequence motifs for protein, DNA, RNA and small molecule S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20131–20139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkens R O, Craig P J, Goessler W, Miller D, Ostah N, Irgolic K J. Biomethylation of inorganic antimony compounds by an aerobic fungus: Scopulariopsis brevicaulis. Environ Sci Technol. 1998;32:882–885. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kagan R M, Clarke S. Widespread occurrence of three sequence motifs in diverse S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases suggests a common structure for these enzymes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;310:417–427. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karlson U, Frankenberger W T. Biological alkylation of selenium and tellurium. In: Sigel H, Sigel A, editors. Metal ions in biological systems. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1993. pp. 185–227. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinkle B K, Sadowski M J, Johnstone K, Koskinen W C. Tellurium and selenium resistance in rhizobia and its potential use for direct isolation of Rhizobium meliloti from soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1674–1677. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1674-1677.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Labahn J, Granzin J, Schluckebier G, Robinson D P, Jack W E, Schildbraut I, Saenger W. Three-dimensional structure of the adenine-specific DNA methyltransferase M.TaqI in complex with the cofactor S-adenosylmethionine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10957–10961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCurdy A, Jimenez L, Stauffer D A, Dougherty D A. Biomimetic catalysis of SN2 reactions through cation interactions. The role of polarizability in catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10314–10321. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miroux B, Walker J E. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:289–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Gara J P, Gomelsky M, Kaplan S. Identification and molecular genetic analysis of multiple loci contributing to high-level tellurite resistance in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4713–4720. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4713-4720.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinish K M, Chen L, Verdine G L, Lipscomb W N. The crystal structure of HaeIII methyltransferase covalently complexed to DNA: an extrahelical cytosine and rearranged base pairing. Cell. 1995;82:143–153. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schluckebier G, O'Gara M, Saenger W, Cheng X. Universal catalytic domain structure of AdoMet-dependent methyltransferase. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:16–20. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Summers A O, Jacoby G A. Plasmid-determined resistance to tellurium compounds. J Bacteriol. 1977;129:276–281. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.1.276-281.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor D E. Bacterial tellurite resistance. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:111–115. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor D E, Hou Y, Turner R J, Weiner J H. Location of a potassium tellurite operon (tehA tehB) within the terminus of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2740–2742. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2740-2742.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor D E, Summers A O. Association of tellurium resistance and bacteriophage inhibition conferred by R plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1979;137:1430–1433. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.3.1430-1433.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson-Eagle E T, Frankenberger W T, Jr, Karlson U. Volatilization of selenium by Alternania alternata. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1406–1413. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.6.1406-1413.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomaki S, Frankenberger W T. Environmental biochemistry. Environ Contam Toxicol. 1992;124:79–110. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-2864-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turner R J, Taylor D E, Weiner J H. Expression of Escherichia coli TehA gives resistance to antiseptics and disinfectants similar to that conferred by multidrug resistance efflux pumps. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:440–444. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner R J, Weiner J H, Taylor D E. Neither reduced uptake nor increased efflux is encoded by tellurite resistance determinants expressed in Escherichia coli. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:92–98. doi: 10.1139/m95-012. . (Erratum, 41:656.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turner R J, Weiner J H, Taylor D E. Use of diethyldithiocarbamate for quantitative determination of tellurite uptake by bacteria. Anal Biochem. 1992;204:292–295. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vidgren J, Svensson L A, Liljas A. Crystal structure of catechol O-methyltransferase. Nature. 1994;368:354–357. doi: 10.1038/368354a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu G, Williams H D, Zamanian M, Gibson F, Poole R K. Isolation and characterization of Escherichia coli mutants affected in aerobic respiration: the cloning and nucleotide sequence of ubiG. Identification of an S-adenosylmethionine-binding motif in protein, RNA, and small-molecule methyltransferases. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:2101–2112. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-10-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]