Abstract

Collection of data for Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) persons that is disaggregated by ethnic subgroup may identify disparities that are not apparent in aggregated data. Using content analysis, we identified national population surveys administered by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and evaluated trends in the collection of disaggregated AANHPI data between 2011 and 2021.

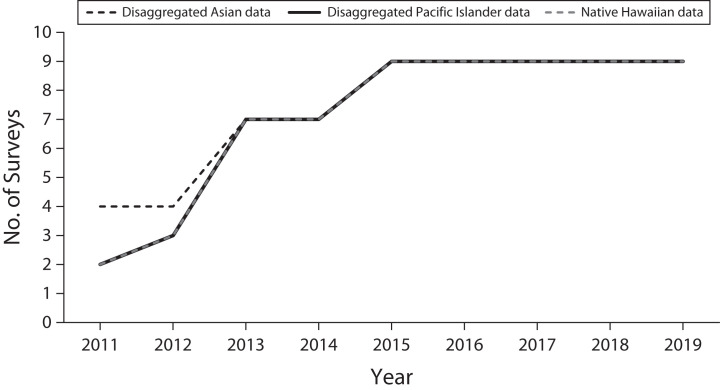

In 2011, 4 of 15 surveys (27%) collected disaggregated data for Asian American, 2 of 15 surveys (13%) collected data on Native Hawaiian, and 2 of 15 surveys (13%) collected disaggregated data for Pacific Islander people. By 2019, 14 of 21 HHS-administered surveys (67%) collected disaggregated data for Asian American (6 subgroups), 67% collected data on Native Hawaiian, and 67% collected disaggregated data on Pacific Islander (3 subgroups) people.

Collection of disaggregated AANHPI data in HHS-administered surveys increased from 2011 to 2021, but opportunities to expand collection and reporting remain. Strategies include outreach with community organizations, increased language assistance, and oversampling approaches. Increased availability and reporting of these data can inform health policies and mitigate disparities. (Am J Public Health. 2022;112(10):1429–1435. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306969)

Approximately 7% of the US population self-identify as Asian American, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander (AANHPI).1 Though often treated as a monolith, the AANHPI population in the United States is diverse, with origins from 50 countries and speaking more than 100 languages.1,2 Disparities between non-Hispanic White and AANHPI people—which are the product of racism, xenophobia, and other structural inequities—are well documented, including higher prevalence of chronic conditions, higher cancer incidence rates, and worse access to care.3–5 While AANHPI people have historically been aggregated as 1 race in many federal surveys, studies suggest that this amorphous category masks wide variation in access to medical resources and health outcomes by ethnic subgroup (e.g., Asian Indian, Chinese).3,6 For example, Filipinx, Asian Indian, and Korean adults have a high prevalence of diabetes; Chinese and Korean people have a higher prevalence of current smoking; and Pacific Islander people have higher rates of obesity.6

Disaggregation of health data for AANHPI people has been a priority of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) for more than 20 years.7 Advocates argue that more granular data are a critical first step for identifying various experiences of care in ethnic subgroups and that this information may be used to inform robust targeted interventions, health policies, and resource allocation. Poor data quality (or failure to collect and report disaggregated data) can codify racist biases and mask health inequities among AANHPI people.8 Organizations such as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation have announced renewed commitment to data disaggregation.9

Population health survey data can be leveraged for assessing disparities in patient-reported access to care, health services utilization, and diagnoses.10 The extent to which disparities can be detected, however, depends on the data that are collected. As such, Section 4302 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 mandated that the HHS Secretary establish data collection standards for race, ethnicity, sex, primary language, and disability status for federally conducted or supported public health surveys by 2012.11 Data collection standards were to be adopted to the extent practicable in all national population surveys.11 The data collection standards, which were developed by the Office of Minority Health (OMH), required more granular data collection for some AANHPI subgroups.11

In 2010, a review by Islam et al. indicated that 4 of 17 federal data sets collected limited AANHPI subgroup data: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), and Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey.12 We extended this work by examining how the landscape of disaggregated AANHPI data collection in population surveys has changed since 2010 and assessing the impact of the mandate on collection and reporting of disaggregated AANHPI data in HHS-administered surveys. We then discuss barriers to expanding data collection in other surveys and identify strategies to promote further adoption of disaggregated AANHPI data and advance AANHPI health equity.

METHODS

Considering the vast number of data systems and data collection activities at HHS, we included lists of HHS surveys and data systems developed by the HHS Assistant Secretary of Planning and Evaluation,13,14 the National Center for Health Statistics,15 and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).16 We supplemented these lists with data sources from previous work examining disaggregated AANHPI data collection.1,12

The scope of our study was to examine trends in disaggregated AANHPI health data among HHS-administered population surveys. Therefore, we excluded provider surveys or facility-level data sets, administrative data, vital records, disease surveillance systems, and area-level data sets (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org). Though some non-HHS federally administered surveys (e.g., American Community Survey) collect health-related data for AANHPI people, we excluded them from our study.

Using content analysis, we reviewed the available documentation from each survey that met our inclusion criteria, such as questionnaires, codebooks, and result summaries. To extend previous work, we reviewed available documentation between 2011 and 2021.3,14 Our unit of analysis was the survey-year, as all surveys were collected on an annual or biennial basis. For each survey, we searched documents for the keywords of “race,” “ethnicity,” “Asian,” “Native Hawaiian,” and “Pacific Islander” to assess whether disaggregated AANHPI data were collected and, if so, for which subgroups. When documentation was not available publicly (n = 5), the study team directly contacted the corresponding agencies.

While we present collection of disaggregated AANHPI data in population surveys through 2021, we focused our examination of trends between 2011 and 2019, as many surveys and data collection systems were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.14 Some HHS-administered surveys were introduced in our study period or were collected for only 1 year. A total of 14 HHS surveys consistently collected data in our study period. Using those 14 surveys, we conducted a separate analysis examining trends in disaggregated AANHPI data collection.

RESULTS

Of 52 data systems administered by HHS in our study period, 26 (50%) were excluded because they were provider surveys, administrative data, disease surveillance systems, vital records, or area-level files (Table A). In Table A and Table B (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org), we summarize collection of disaggregated AANHPI data by 6 HHS agencies (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CMS, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Institutes of Health, and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) administered between 2011 and 2021. The total number of surveys in our sample ranged from 15 in 2011 to 21 in 2019. Four surveys (Health Center Patient Survey, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander National Health Interview Survey, Home and Community-Based Services Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Provider and Systems [CAHPS], and Nationwide Adult Medicaid CAHPS) were each collected for 1 year.

Among surveys that collected disaggregated AANHPI data in their most recent year of data collection, the number of Asian American subgroups ranged between 7 and 35, and the number of Pacific Islander subgroups ranged between 3 and 10. Some surveys—particularly CAHPS surveys—also documented the availability of linguistically inclusive survey materials, in which the most common languages were Cantonese, Mandarin, Korean, and Vietnamese.

Trends in Disaggregated Data Collection

In 2011, about one quarter of HHS-administered surveys (4 of 15, or 27%) collected disaggregated Asian American data, and fewer (2 of 15, or 13%) collected Native Hawaiian data and disaggregated Pacific Islander data. By 2019, two thirds of HHS-administered surveys (14 of 21, or 67%) collected disaggregated data for Asian American (6 subgroups), Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (3 subgroups) people. There were 14 HHS surveys that consistently collected data in our study period. In 2011, of the 14 surveys, 4 surveys (29%; MEPS, NHIS, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES], and NSDUH) collected disaggregated Asian American data, 2 surveys (14%; NHIS and NHANES) collected Native Hawaiian data, and 2 surveys (14%; NHIS and NHANES) collected disaggregated Pacific Islander data (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Trends in Collection of Disaggregated Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Data: US Department of Health and Human Services‒Administered Surveys

Note. Limited to 14 surveys that consistently collected data between 2011 and 2019 (Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, Fee for Service Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Provider and Systems, Health and Retirement Study, Health Outcomes Survey, Home Health Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Provider and Systems, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Provider and Systems, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES], National Health Interview Survey, National Immunization Survey [NIS], National Survey of Family Growth, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, National Youth Tobacco Survey). Disaggregated Asian American data for all surveys included Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and other Asian. Disaggregated Pacific Islander data included Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamorro, Samoan, and other Pacific Islander. NHANES collected data on 29 additional Asian American subgroups (Bangladeshi, Bengalese, Bharat, Bhutanese, Burmese, Cambodian, Cantonese, Dravidian, East Indian, Goanese, Hmong, Indochinese, Indonesian, Iwo Jiman, Lao-Hmong, Laotian, Madagascar/Malagasy, Malaysian, Maldivian, Mong, Nepalese, Nipponese, Okinawan, Pakistani, Siamese, Singaporean, Sri Lankan, Taiwanese, and Thai) and NIS collected data on 6 additional Pacific Islander subgroups (Chuukese, Pohnpeian, Palauan, Yapese, Kosraean, and Marshallese).

Following the ACA mandate, the number of surveys collecting disaggregated data increased for AANHPI people, reaching a total of 9 (64%) by 2015, where it has since plateaued. Of surveys currently being collected, 8 do not collect disaggregated AANHPI data: Health and Retirement Survey, Home Health CAHPS, Hospital CAHPS, Medicare Fee-for-Service CAHPS, Medicare Advantage Health Plan Disenrollment Survey, Qualified Health Plan Enrollee Survey, National Youth Tobacco Survey, and Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Collection of Disaggregated Data on Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Patients: US Department of Health and Human Services Patient Surveys, 2011–2021

| Survey | Agency | Years of Data Collection | Disaggregated AANHPI Data Collected | Year Disaggregated AANHPI Data Collection Began |

| Medical Expenditure Panel Survey | AHRQ | 2011–2018 | Yes | 2011 (Asian American), 2012 (NHPI) |

| Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System | CDC | 2011–2020 | Yes | 2013 |

| National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey | CDC | 2011–2021 | Yes | 2011 |

| National Health Interview Survey | CDC | 2011–2021 | Yes | 2011 |

| National Immunization Survey | CDC | 2011–2021 | Yes | 2015 |

| National Survey of Children’s Health | CDC (2011–2012), HRSA (2016–2020) | 2011–2012, 2016–2021 | Yes | 2016 |

| National Survey of Family Growth | CDC | 2011–2019 | Yes | 2013 |

| National Youth Tobacco Survey | CDC | 2011–2020 | No | NA |

| Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander National Health Interview Survey | CDC | 2014 | Yes | 2014 |

| Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System | CDC | 2011–2021 | No | NA |

| CAHPS for Accountable Care Organizations Participating in Medicare Initiatives | CMS | 2013–2021 | Yes | 2013 |

| CAHPS for Merit-Based Incentive Payment System | CMS | 2016–2021 | Yes | 2016 |

| Fee for Service CAHPS | CMS | 2011–2021 | No | NA |

| Health Outcomes Survey | CMS | 2011–2021 | Yes | 2013 |

| Home and Community Based CAHPS | CMS | 2017 | Yes | 2017 |

| Home Health CAHPS | CMS | 2011–2021 | No | NA |

| Hospital CAHPS | CMS | 2011–2019 | No | NA |

| In-Center Hemodialysis CAHPS | CMS | 2015–2021 | Yes | 2015 |

| Medicare Advantage and Prescription Drug Plan Disenrollment Survey | CMS | 2013–2021 | No | NA |

| Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey | CMS | 2011–2021 | Yes | 2015 |

| Nationwide Adult Medicaid CAHPS | CMS | 2014 | Yes | 2014 |

| Outpatient and Ambulatory Surgery CAHPS | CMS | 2016–2021 | Yes | 2016 |

| Qualified Health Plan Enrollee Survey | CMS | 2020–2021 | No | NA |

| Health Center Patient Survey | HRSA | 2014 | No | NA |

| Health and Retirement Survey | NIH | 2010–2021 | No | NA |

| National Survey on Drug Use and Health | SAMHSA | 2011–2019 | Yes | 2011 (Asian American), 2013 (NHPI) |

Note. AANHPI = Asian American, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander; AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; CAHPS = Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Provider and Systems; CMS = Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; NA = not applicable; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NHPI = Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander; SAMHSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. For all surveys that collected disaggregated Asian American data, the subgroups collected were Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and other Asian. For all surveys that collected disaggregated Pacific Islander data, the subgroups collected were Guamanian or Chamorro, Samoan, and other Pacific Islander. NHANES and NIS were the only surveys that expanded upon these groups (see Table D, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org).

Commonly Collected Ethnic Subgroups

There were 7 commonly used ethnic subgroups among Asian American people (Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipinx, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and other Asian) and 3 commonly collected subgroups for Pacific Islander people (Guamanian or Chamorro, Samoan, and other Pacific Islander; Table C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org). All surveys that collected disaggregated Pacific Islander data included a category for Native Hawaiians. The only surveys that included additional response options beyond these 11 subgroups was NHANES, which included a total of 35 response options for Asian Americans, and the National Immunization Survey, which included 10 response options for Pacific Islanders (Figure 1; Tables C and D, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org).

DISCUSSION

In our examination of HHS-administered population surveys, we found that the number of surveys collecting disaggregated AANHPI data increased between 2011 and 2021. Following the ACA mandate, many surveys have aligned with OMH data collection standards to include 11 AANHPI subgroups: Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipinx, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, other Asian, Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamorro, Samoan, and other Pacific Islander. Many—but not all—HHS-administered surveys have expanded data collection since 2010.1,2,12 Importantly, few surveys expanded upon the OMH data collection standards, suggesting additional disaggregation is still necessary for some groups (e.g., Pakistani, Sri Lankan, Burmese, and Nepalese people).2,10

Barriers

Inclusion of subgroup questions on population-based surveys face several interconnected challenges, including limited translation to Asian languages, low response rates, small sample sizes, and variation in reporting.1,2,12 Small sample sizes, for example, can prevent federal agencies’ ability to report statistics disaggregated by subgroup or release public-use files with disaggregated AANHPI categories because of potential confidentiality or data-security issues, and limit researchers’ ability to access such data.2,9,17 Several of the publicly available data sets in our study do not make the disaggregated data publicly available. Though collection of disaggregated data is a critical step, gaps in reporting metrics by AANHPI subgroup and making disaggregated data publicly available remain.

We were unable to examine the reasons approximately one third of HHS surveys do not collect disaggregated AANHPI data. Though sample size could, in part, play a role, in Table B we show that several of the surveys that do not collect disaggregated data have comparable or larger annual sample sizes compared with other surveys. Another possible explanation is that—considering the mandate indicated that standards be adopted “to the extent practicable”—agencies did not prioritize or were unable to implement disaggregated data collection. Even among survey leaders who want to collect more granular subgroup data, administrative constraints have been cited as a barrier: increasing sample sizes, developing approaches for more detailed enumeration, or attempting to implement new methodologies that sufficiently capture subpopulations (e.g., developing oversampling strategies, hiring bilingual interviewers, partnering with translation services) can be expensive and complex. Understanding the reasons and barriers to disaggregated data collection for HHS surveys warrants further exploration.

Opportunities to Expand

Researchers and advocates have proposed multiple potential solutions to increase collection of disaggregated AANHPI data. First, federal or state mandates that may encourage data disaggregation are necessary but insufficient. As our study findings suggest, more HHS-administered health surveys began collecting disaggregated AANHPI data following the ACA’s mandate to develop and implement data collection standards.

Second, innovative and successful approaches to sampling—such as outreach with community organizations to encourage participation, language assistance for limited English proficiency, and data collection using multiple modes—may mitigate issues around small sample size.1,12 For example, the California Health Interview Survey uses multiple approaches to oversample certain ethnic subgroups, including interviewing in several Asian languages (Cantonese, Mandarin, Korean, Vietnamese, Khmer, and Tagalog), using a targeted surname list sample to oversample for Korean and Vietnamese people, and interviewing with both landline or cellphone survey modalities.1 These efforts must be accompanied by increased funding or investments to support the resources needed to successfully expand data collection.

Implications for Policy and Practice

The need for disaggregated AANHPI data has been particularly critical during the COVID-19 pandemic.18,19 The pandemic, subsequent economic recession, and waves of anti‒AANHPI physical assaults and racism illustrated the persistent structural inequities faced by AANHPI people.18,20,21 Several studies have noted the lack of COVID-19 data for AANHPI communities, despite increased risk for infection because of disproportionate participation in essential workforce, structural inequities, and a higher likelihood of residing in multigenerational households.18,20,22 The disproportionate number of COVID-19‒related deaths among Filipinx nurses underscores the importance of disaggregated data collection and reporting during the pandemic.23

Studies suggest that poor data quality limited the ability to identify and mitigate COVID-19‒related disparities nationwide for AANHPI subgroups, as well as to understand the mechanisms driving them.18,24 In New York City, there was variation in COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and mortality rates across Asian American subgroups.22 Disaggregated AANHPI data also suggest heterogeneity in concern for physical assault and self-reported discrimination by subgroup during the COVID-19 pandemic.21 Despite national efforts to improve disaggregated AANHPI data collection and reporting, the COVID-19 pandemic underscored that these practices remain inconsistent and suboptimal. Importantly, recent state-level initiatives have emerged to collect disaggregated AANHPI data (e.g., Hmong communities in Minnesota).

Population surveys have the unique opportunity to identify health disparities that would be otherwise masked with aggregate grouping.10 A critical first step to understanding the diversity of experiences among AANHPI people and eliminating AANHPI disparities is the collection and reporting of granular subgroup data. More broadly, advancing AANHPI health equity will require concurrent efforts to remove structural barriers, such as lack of funding for AANHPI‒specific research, extrapolation of research findings to all AANHPI subgroups, and omission or limited representation in US clinical trials.17,25 Systems-level implicit and explicit AANHPI biases—including narratives of AANHPI exceptionalism and the perpetuation of the “model minority myth”—may hinder national progress in prioritizing AANHPI health disparities.12,25

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, though we attempted to be comprehensive in our list of HHS-administered population surveys by using multiple data sources, it is possible that some were excluded.

Second, though we limited our study to HHS-administered surveys, many state health surveys and non‒HHS-administered federal surveys have been collecting disaggregated AANHPI data and are considered some of the best sources of information on ethnic subgroups among AANHPI people.12 In November 2021, the New York University Center for the Study of Asian American Health released the AA & NH/PI Web Hub, which provides additional research data sets related to AANHPI people.

Third, disaggregated data collection alone does not address other issues, such as respondents not recognizing or being fearful of self-reporting race or ethnic subgroup information when presented to them and higher likelihoods of Asian Americans reporting “other” or “unknown” race. Moreover, collection of disaggregated data does not necessarily guarantee reporting or availability of such data to researchers.

Lastly, despite inclusion of subgroup questions in national questionnaires, it is possible that there is variation by state as to whether these questions are asked for some surveys (e.g., Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System).1

CONCLUSIONS

The growth in collection of disaggregated AANHPI data in HHS-administered population surveys is encouraging and a critical first step to identifying and addressing AANHPI health disparities across subgroups. As the United States becomes more diverse, it is important to be attentive to how subgroups are collected and defined in survey-based research and to ensure that survey data are comprehensive and inclusive. While there has been improvement in data collected in the past decade, some gaps remain. Failure to collect these data may prevent a detailed understanding of characteristics, health status, and health needs of AANHPI people, thereby affecting the development of policies and allocation of resources.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

K. H. Nguyen completed this work while supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Scholars program.

Note. The results of this study reflect the views of the authors only and do not represent those of the federal government or the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Institutional review board approval was not needed because this study did not use human participants. The unit of analysis was survey-year.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Shimkhada R, Scheitler A, Ponce NA. Capturing racial/ethnic diversity in population-based surveys: data disaggregation of health data for Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islanders (AANHPIs) Popul Res Policy Rev. 2021;40(1):81–102. doi: 10.1007/s11113-020-09634-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chin KK. Improving public health surveillance about Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):827–828. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen KH, Trivedi AN. Asian American access to care in the Affordable Care Act era: findings from a population-based survey in California. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2660–2668. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05328-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng YJ, Kanaya AM, Araneta MRG, et al. Prevalence of diabetes by race and ethnicity in the United States, 2011‒2016. JAMA. 2019;322(24):2389–2398. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.19365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torre LA, Sauer AMG, Chen MS, Jr, Kagawa‐Singer M, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders, 2016: converging incidence in males and females. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(3):182–202. doi: 10.3322/caac.21335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wyatt L, Russo R, Kranick J, Elfassy T, Kwon S, Wong J.2021. https://med.nyu.edu/departments-institutes/population-health/divisions-sections-centers/health-behavior/sites/default/files/pdf/csaah-health-atlas.pdf

- 7.Waksberg J, Levine DB, Marker D.2000. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/assessment-major-federal-data-sets-analyses-hispanic-asian-or-pacific-islander-subgroups-native

- 8.Yi SS, Kwon SC, Suss R, et al. The mutually reinforcing cycle of poor data quality and racialized stereotypes that shapes Asian American health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(2):296–303. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farah K, Doan LN, Lee M, Chin MK, Kwon SC, Yi SS. Disaggregating race/ethnicity data categories: criticisms, dangers, and opposing viewpoints. Health Affairs Forefront. 2022 doi: 10.1377/forefront.20220323.555023. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20220323.555023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponce NA. Centering health equity in population health surveys. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(12):e201429-e. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health. 2022. https://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=23

- 12.Islam NS, Khan S, Kwon S, Jang D, Ro M, Trinh-Shevrin C. Methodological issues in the collection, analysis, and reporting of granular data in Asian American populations: historical challenges and potential solutions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(4):1354–1381. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2012. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/guide-hhs-surveys-and-data-resources

- 14.Queen S, Mintz R, Cowling K. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on major HHS data systems. Washington, DC: US Office of the Assistant Secretary of Planning and Evaluation; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/survey_matrix_2017.pdf

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/CAHPS

- 17.Đoàn LN, Takata Y, Sakuma K-LK, Irvin VL. Trends in clinical research including Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander participants funded by the US National Institutes of Health, 1992 to 2018. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(7):e197432-e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chin M, Đoàn L, Chong SK, Wong JA, Kwon SC, Yi S. Asian American subgroups and the COVID-19 experience: what we know and still don’t know. Health Affairs Blog. 2021 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210519.651079 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang K, Cullen T, Nunez-Smith M. Centering equity in the design and use of health information systems: partnering with communities on race, ethnicity, and language data. Health Affairs Forefront. 2021 doi: 10.1377/hblog20210514.126700. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210514.126700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penaia CS, Morey BN, Thomas KB, et al. Disparities in Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander COVID-19 mortality: a community-driven data response. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(suppl 2):S49–S52. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ha SK, Nguyen AT, Sales C, et al. 2020. [DOI]

- 22.Marcello RK, Dolle J, Tariq A, et al. 2020. [DOI]

- 23.Oronce CIA, Adia AC, Ponce NA. US health care relies on Filipinxs while ignoring their health needs: disguised disparities and the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(7):e211489-e. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quint JJ, Van Dyke ME, Maeda H, et al. Disaggregating data to measure racial disparities in COVID-19 outcomes and guide community response—Hawaii, March 1, 2020‒February 28, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(37):1267–1273. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7037a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obra J, Lin B, Doan LN, Palaniappan L, Srinivasan M. Achieving equity in Asian American healthcare: critical issues and solutions. J Asian Health. 2021;1(1) doi: 10.59448/jah.v1i1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]