Abstract

Cigarette smoking (CS) remains a cause of considerable morbidity and mortality, despite recent progress in smoking cessation in the United States. Epidemiologic studies in humans have reported associations between CS and development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) after a number of inciting risk factors. We have assessed the effects of CS exposure on lung vascular permeability and inflammation in mice and found that both acute and sustained CS exposure increased the severity of acute lung injury caused by subsequent intrapulmonary instillation of lipopolysaccharide. In addition to enhanced inflammation, CS exposure directly impaired lung endothelial cell barrier function. Our results indicate that mouse strains differ in susceptibility to CS exacerbation of acute lung injury and that there are differences in transcriptomic effects of CS. These results demonstrate the biologic basis for the association of CS with development of ARDS. We propose that CS be considered a cause of heterogeneity of ARDS phenotypes and that this be recorded as a risk factor in the design of clinical trials.

INTRODUCTION

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a syndrome of acute respiratory failure, with high morbidity and mortality, despite advances in supportive care (1). Numerous and diverse risk factors predispose to ARDS, including trauma, sepsis, and blood transfusions. Recent research done by Calfee and colleagues has provided insight into clinical phenotypes of ARDS with “hyper-inflammatory” and “hypo-inflammatory” phenotypes (2). Secondary analyses of clinical trials have indicated that these phenotypes respond differently to treatments, such as fluid restriction (3) and simvastatin (4). Thus, it is important to better understand predisposing risk factors and how these relate to ARDS phenotypes.

Not all individuals exposed to the same inciting insults develop ARDS. Therefore, it is important to understand the biologic basis for differences in susceptibility to ARDS. Growing epidemiologic evidence indicates that exposure to cigarette smoke is associated with increased risk of ARDS. This includes ARDS following blunt trauma (5), pulmonary and non-pulmonary sepsis (6), and hemorrhage (7). We hypothesized that cigarette smoke exposure might predispose to risk of acute lung injury and ARDS. For the past several years, our laboratory has investigated the biologic basis of cigarette smoke exposure-induced risk of acute lung injury and ARDS using mouse and cell models. We have found that both acute and more sustained exposure of mice to cigarette smoke increases the severity of acute lung injury caused by lipopolysaccharide (8). We have also demonstrated that more chronic exposure to cigarette smoke increases apoptosis of lung microvascular endothelial cells (9). Mouse strains differ in response to cigarette smoke exposure, suggesting a genetic basis for differing susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced risk of ARDS (10). Exposure of cultured pulmonary vascular endothelial cells to aqueous extracts of cigarette smoke increases monolayer permeability due to RhoA GTPase signaling through a mechanism that involves impairment of RhoA GTPase and Focal Adhesion Kinase activation (11). This work indicates that there is a biologic basis for cigarette smoking-induced increased risk of ARDS. Cigarette smoking is a cause of heterogeneity in risk for ARDS and should be taken into account in the design and interpretation of clinical trials.

METHODS

Reagents

Lipopolysaccharide (L5418, LPS, 1mg/ml) from Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5 (endotoxin level = 500,000 endotoxin units/mg) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). LPS was filtered with 0.2 µm filters and the same lot of LPS was used for experiments.

CS Exposure of Mice

All animal protocols were approved by the Providence VA Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and complied with the Health Research Extension Act and the Public Health Service policy. Male C57BL/6 and AKR mice six to eight weeks old were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Mice were exposed to room air (RA) or CS for three to six hours per day. Longer-term exposures were for six hours per day for four days per week for three weeks using a TE-10 mouse smoking machine (Teague Enterprises, Woodland, CA) and 3R4F reference cigarettes (University of Kentucky, Tobacco Research Institute, Lexington, KY) (10). The smoke machine produced a mixture of sidestream (89%) and mainstream (11%) smoke. The smoking chamber atmosphere was monitored for total suspended particles at a concentration of 120 mg/m3.

Intratracheal Administration of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

By the end of the final CS exposure, mice were anaesthetized with 3% isofluorane and intratracheally instilled with 2.5 mg/kg of LPS (dissolved in 50 µl of saline) or an equal volume of saline. Eighteen hours after LPS administration, mice were sacrificed, and lung injury was assessed.

Assessments of Acute Lung Injury

Lung mechanics, including static lung compliance, were assessed using the FlexiVent system (SCIREQ, Montreal, Canada) (10).

Protein concentration and inflammatory cell counts in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were assessed (10). After assessment of lung mechanics, mice were euthanized using an overdose of pentobarbital (120 mg/kg) through intraperitoneal injection. The lung was lavaged via a trachea catheter with 600 µl of sterilized saline using a 1 ml syringe. The protein concentrations in the BAL fluid were measured by detergent compatible protein assay. The total numbers of inflammatory cells in the BAL fluid were counted using a phase light microscope at 400X magnification.

The loss of lung vascular integrity was assessed by wet/dry lung weight ratios and by leakage of Evan’s blue dye from vessels after intravenous injection (10).

Preparation of Cigarette Smoke Extract (CSE)

Mainstream smoke from Kentucky Research cigarettes (3R4F) was drawn into 30 ml of pre-warmed phosphate buffered saline (PBS) by a vacuum (11). Each cigarette was lit for five minutes, and five cigarettes were used per 30 ml of PBS to generate a CSE-PBS solution. Control solution (sham PBS) was prepared with the same protocol used to generate CSE, except that the cigarettes were unlit. The CSE was diluted with medium and used immediately. Final concentrations of CSE are expressed as percent values (the ratio of volume of CSE-PBS solution to the volume of the final total medium used to treat the cells).

Endothelial Cells

Bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAEC) and rat lung microvascular endothelial cells (LMVEC) were purchased from VEC Technologies Inc. (Rensselaer, NY), used between passages 3–8, and maintained in culture (12).

Endothelial Monolayer Permeability

Endothelial cells were cultured on gold electrodes, and permeability of confluent monolayers was assessed using electrical resistance (11).

Gel Electrophoresis and Immunoblot Analysis

Lysates were solubilized in Laemmli buffer; proteins were resolved using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes and immunoblotted with specific antibodies (11).

RhoA GTPase Activity Assay

RhoA GTPase activity was assessed by pull-down assay, using pGSTC21 beads. Total RhoA protein in the lysates was also assessed by immunoblot analysis (13).

Data Analysis

For in vitro culture studies, all experiments were performed at least in triplicate. Means and standard errors (SE) were calculated based on the value of individual treatments and the number of experiments performed. For animal studies, three to six mice per group were used. Means and SE were calculated based on the values of each animal in each group and the numbers of animals used in that group. Data are presented as mean ± SE. The difference between two means was assessed using a Student’s t test, and the differences among three or more means were assessed using ANOVA followed by a Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test. Differences among means are considered significant when p<0.05.

RESULTS

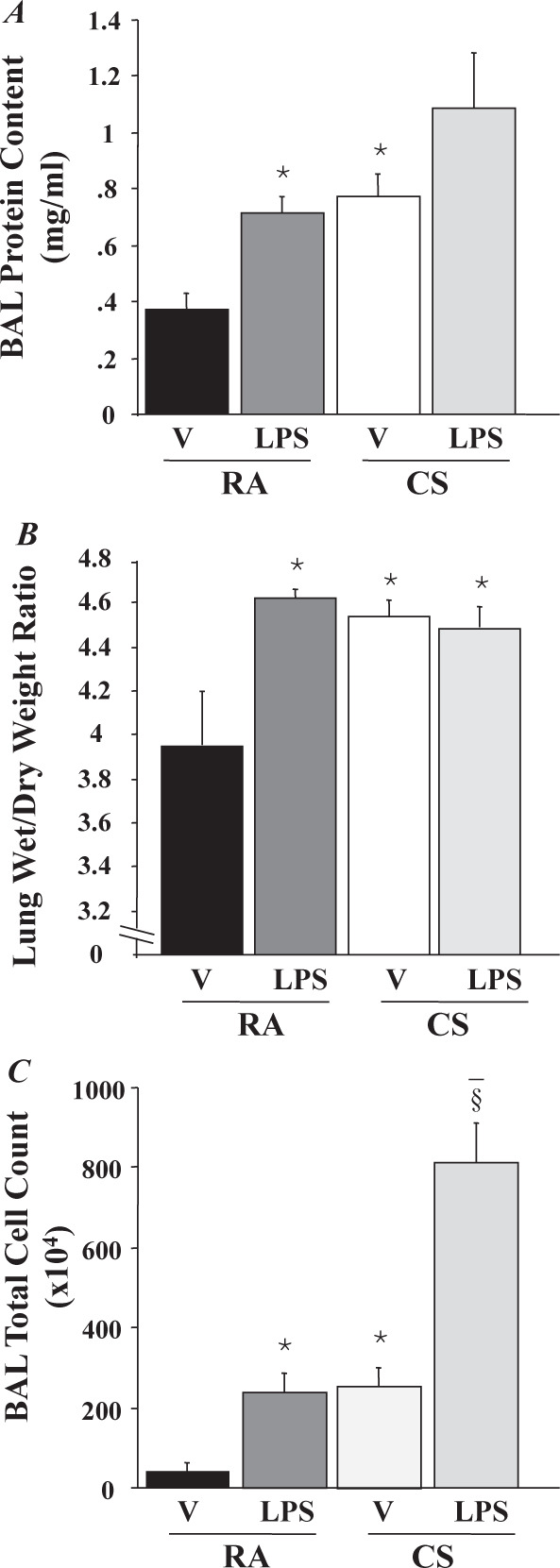

We found that acute exposure of C57BL/6 mice to cigarette smoke for six hours increased acute lung injury, as assessed by wet/dry lung weight and by protein concentration and cell counts in BAL (Figure 1). Instillation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) also caused acute lung injury, and the effect of LPS on BAL protein and cell count was exacerbated by pre-exposure to cigarette smoke (11).

Fig. 1.

Cigarette smoke (CS) increases lung vascular permeability and exacerbates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced lung edema. C57BL/6 mice were exposed to CS or room air (RA) for six hours and then intratracheally given 2.5 mg/kg LPS or an equal volume of 0.9% NaCl [vehicle (V), 50 ml]. At 24 hours after LPS or vehicle challenge, the lungs were lavaged with 600 ml of saline, and the protein content in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was assessed (A). Total cell counts in BAL fluid were also assessed (C). Parallel sets of animals were used for assessment of lung wet-to-dry weight ratio (Wet/Dry) (B). Data are presented as means ±SE per group (n = 6) in each panel, *p< 0.05 vs. mice exposed to RA and treated with vehicle; § p< 0.05 vs. mice exposed to RA and treated with LPS. Reproduced with permission of the American Journal of Physiology (11).

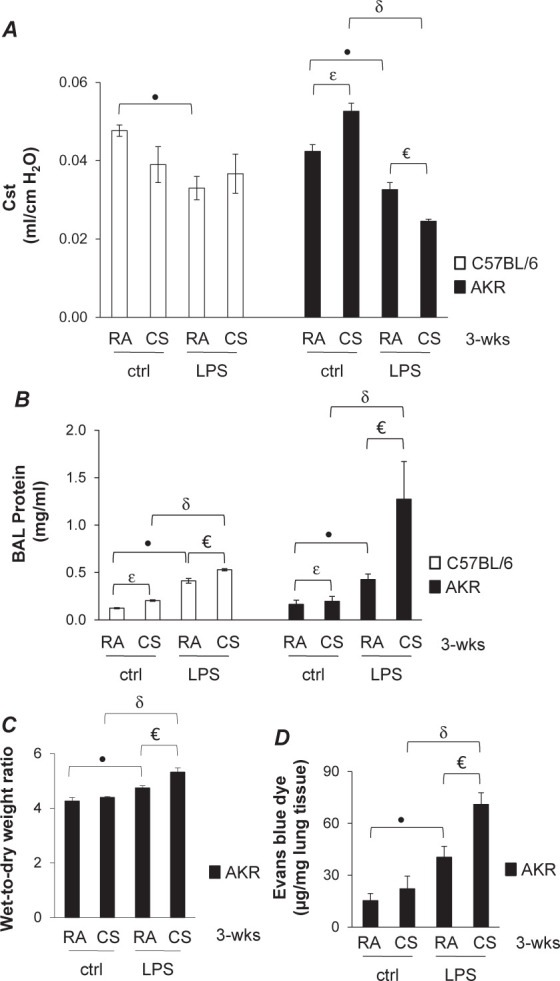

We compared the effects of more sustained exposure to cigarette smoke of C57BL/6 and AKR mice. We found that exposure to cigarette smoke for six hours per day, four days per week, for three weeks resulted in increased static compliance of lungs of AKR mice and only small increases in BAL protein of both C57 and AKR mice (Figure 2A). However, subsequent instillation of LPS caused acute lung injury in both strains with decreased static lung compliance (Figure 2A) and increased BAL protein (Figure 2B). AKR mice were more susceptible than C57BL/6 mice to the double hit of sustained cigarette smoke exposure followed by LPS, with AKR mice also demonstrating increased wet/dry lung weight and Evans blue dye extravasation (Figures 2C and D). AKR mice subjected to three weeks of cigarette smoke had increased pro-inflammatory cytokines in BAL and apoptosis in lung tissue, as assessed by cleaved caspase-3 expression in lung homogenates and TUNEL staining of microvascular lung endothelial cells [data not shown, (10)].

Fig. 2.

Effects of prolonged CS exposure on LPS-induced lung edema in two strains of mice. Male six-week-old C57BL/6 and AKR mice were exposed to RA or CS for three weeks as described in METHODS. One hour after the last CS exposure, mice were intratracheally administered with 2.5 mg/kg of LPS or equal volume of saline as a control. After 18 hours, lung static compliance (Cst) was assessed using a FlexiVent system (A). BAL fluid was collected for assessment of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) protein content (B). Lung wet-to-dry weight ratio (C) and lung extravasation of albumin-conjugated Evans blue dye (EBD) (D) were assessed in additional sets of AKR mice that were subjected to the same treatments. In A, nine to ten C57BL/6 mice per group and nine to eleven AKR mice per group were used; in B, three to four C57BL/6 mice per group and four to six AKR mice per group were used; in C, three AKR mice per group were used; in D, four to five AKR mice per group were used. p <0.05 CS/ctrl vs. RA/ctrl; *p <0.05 RA/LPS vs. RA/ctrl; δp <0.05 CS/LPS vs. CS/ctrl; €p <0.05 CS/LPS vs. RA/LPS. Reproduced with permission of the American Journal of Physiology (10).

The differences among mouse strains in susceptibility to cigarette smoke exposure-induced lung injury are associated with changes in gene transcription, suggesting a genetic basis for these effects (unpublished, data not shown).

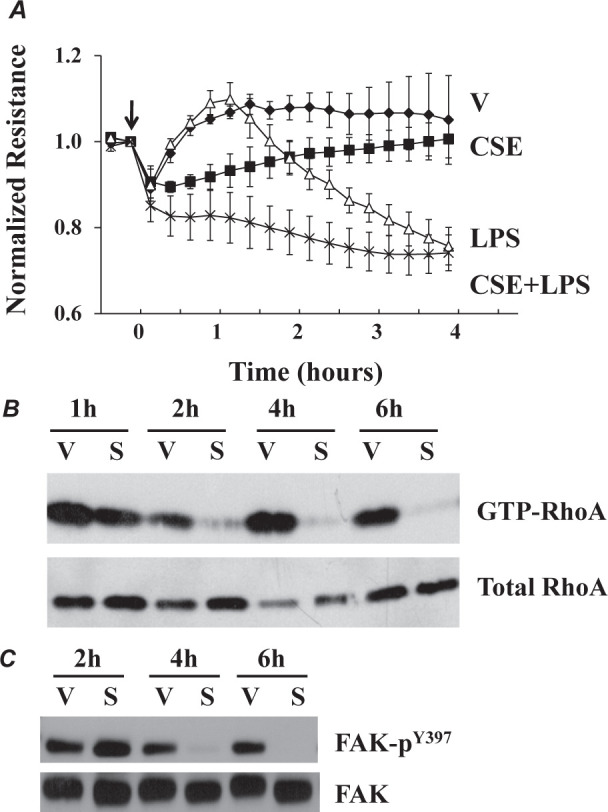

We hypothesized that the effects of cigarette smoke exposure on lung vascular permeability might be due to direct effects on endothelial cell function. We therefore assessed effects of cigarette smoke extract on electrical resistance across cultured pulmonary artery endothelial cell monolayers (11). We found that cigarette smoke extract increased monolayer permeability (Figure 3A) and that this effect was associated with impaired activation of both RhoA GTPase (Figure 3B) and Focal Adhesion Kinase (Figure 3C), which are important in maintenance of normal endothelial barrier function.

Fig. 3.

(A) Cigarette smoke extract (CSE) exacerbated LPS-induced increase in endothelial monolayer permeability. Bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAEC) were treated with vehicle (5% sham PBS) or 5% CSE in the absence or presence of LPS (0.5 mg/ml) for indicated times. Endothelial monolayer permeability was assessed by measuring electrical resistance across monolayers over time by electrical cell impedance sensor (ECIS). Data are presented as means ± SE of the normalized electrical resistance relative to the time when agents were added, as indicated by an arrow; n = 6. (B) Changes in RhoA GTPase activation in CSE-treated (S) or vehicle-treated (V) PAEC. (C) Changes in Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK) activation in CSE-treated (S) or vehicle-treated (V) PAEC. Reproduced with permission of the American Journal of Physiology (11).

DISCUSSION

Although the prevalence of tobacco combustion has decreased over the years, cigarette smoking is still a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Cigarette smoking is clearly associated with lung diseases and is also a cause of systemic injury, including inflammation and atherosclerosis of the systemic vasculature (14). We have reviewed the effects of CS on lung endothelial function and the role of lung endothelial injury in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension and emphysema (8).

Our studies have demonstrated that both acute and longer-term cigarette smoke exposure causes acute lung injury in mice that is exacerbated by subsequent exposure to lipopolysaccharide. This effect is associated with acute inflammation and with direct effects of cigarette smoke on endothelial cell signaling mechanisms that are important in maintenance of normal barrier function. The AKR and C57BL/6 mouse strains differ in susceptibility to smoke-induced lung injury and gene transcription.

We have reported that CS changes lung endothelial autophagy and apoptosis (9), microtubule function (15), and mitochondrial function (16). Thus, there is a firm biological basis for the deleterious effects of CS on lung endothelial cell barrier function. Others have demonstrated that CS also predisposes smokers to bacterial infection-induced acute lung injury (ALI), and that it is not limited to LPS-induced injury (17). Although CS undoubtedly also affects lung epithelial and inflammatory cell functions, there is strong evidence to support effects on lung endothelial cells as well (8).

CS is a complex mixture of noxious components, including nicotine, fine particulate matter, gases (e.g., hydrogen cyanide), hydrocarbons (e.g., benzene), oxidants, and aldehydes (e.g., acrolein). We have also investigated the effects of the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde, acrolein, on endothelial cell function and acute lung injury. We found that acrolein alone caused acute lung injury in mice and increased endothelial cell permeability, similar to effects of CS exposure (18). However, it is unlikely that the effects of CS on lung endothelial function and acute lung injury are due a single component of CS, but instead are caused by aggregate effects of multiple noxious agents. Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated the association of both active and passive (“secondhand smoke”) CS exposure with ARDS in humans (5). Importantly, medical history and medical record reviews may not accurately estimate CS exposure; thus, biomarkers, such as urinary 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridol)-1-butanol (NNAL) and plasma cotinine, are more accurate reflections of CS exposure.

We and others have demonstrated heterogeneity among mouse strains in susceptibility to CS-induced acute (10) and chronic lung injuries (19). This suggests that genetic differences might explain differences in susceptibility to ARDS among individuals exposed to similar predisposing injuries. Furthermore, in as yet unpublished work, we have demonstrated differences in transcriptomic responses to CS exposure.

The results of our studies have implications for clinical trials of management of ARDS in patients. Clearly, both active and passive exposure to cigarette smoke should be considered a risk factor for more severe lung injury and ARDS. In addition, we suggest that CS exposure may be one cause of phenotypic heterogeneity of ARDS and that this should be taken into account in the design and interpretation of clinical trials. Furthermore, CS exposure may provide clues to personalized treatments that might ameliorate the severity of ARDS in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND FINANCIAL SUPPORT

The authors thank many colleagues who have contributed to this work, particularly Pavlo Sakhatskyy, Gaurav Choudhary, and Elizabeth Harrington. This work was supported by grant P20 GM103652 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, NIH (SR, QL project 1), R01HL130230 (QL, SR), U54 GM115677 (SR), Brown Medical School DEANS Award (SR, QL), VA Merit Review Award 101 BX002622 (SR), Rhode Island Foundation grant (20190594; JHS), Alzheimer’s Administrative Supplement grant (JHS), and TEAM UTRA grant from Brown University to JHS.

Footnotes

Correspondence and reprint requests: Sharon Rounds, MD, Vascular Research Laboratory, Pulmonary/Critical Care/Sleep, Department of Medicine, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Ocean State Research Institute, VA Providence Healthcare System, 830 Chalkstone Ave., Providence, RI 02908; Tel: 401-863-1775; Fax: 401-863-5096; E-mail: Sharon_rounds@brown.edu

Potential Conflicts of Interest: None disclosed.

DISCUSSION

Mackowiak, Baltimore: Thank you, Dr. Rounds, very interesting. Cigarette smoke is a complicated gemish of things. What is known about the most specific and important items in smoke? I am extremely interested in this because there might be some beneficial elements there. If you look at some patients who are most susceptible to lung damage, such as those with psychiatric disorders and also inflammatory bowel disease, smoking seems to have a beneficial effect. I wonder what is known about that particular issue.

Rounds, Providence: Yes, that’s an important question. Cigarette smoke is complicated, nasty stuff. There’s probably about 5,000 components ranging from fine particulate matter to, of course, nicotine, the addictive substance. I did not talk today about work from our laboratory that has emphasized the importance of components such as acrolein, an aldehyde that is highly reactive and causes an aldehyde-induced lung injury. Aldehyde acrolein is an important component of cigarette smoke. What about those who vape? Vaping is less complicated perhaps than combustible tobacco, but it’s complicated stuff with flavors, dilutants, and, of course, nicotine. We all know that patients who vape are susceptible to developing acute lung injury, which may in part be due to tetrahydrocannabinol included with the nicotine. Some patients do in fact develop acute lung injury without apparent exposure to cannabis. We may learn more from the vaping epidemic about individuals’ susceptibility to these things, but I’m not sure it really matters because what people are smoking is smoke. With the exception of vaping, they’re inhaling all of these multiple, deleterious substances.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122((8)):2731–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI60331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calfee CS, et al. Subphenotypes in acute respiratory distress syndrome: latent class analysis of data from two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2((8)):611–20. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70097-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Famous KR, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome subphenotypes respond differently to randomized fluid management strategy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195((3)):331–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201603-0645OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calfee CS, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome subphenotypes and differential response to simvastatin: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6((9)):691–8. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calfee CS, et al. Active and passive cigarette smoking and acute lung injury after severe blunt trauma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183((12)):1660–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1802OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calfee CS, et al. Cigarette smoke exposure and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2015;43((9)):1790–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toy P, et al. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: incidence and risk factors. Blood. 2012;119((7)):1757–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-370932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu Q, Gottlieb E, Rounds S. Effects of cigarette smoke on pulmonary endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2018;314((5)):L743–56. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00373.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakhatskyy P, et al. Cigarette smoke-induced lung endothelial apoptosis and emphysema are associated with impairment of FAK and eIF2alpha. Microvasc Res. 2014;94:80–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakhatskyy P, et al. Double-hit mouse model of cigarette smoke priming for acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2017;312((1)):L56–67. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00436.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Q, et al. Cigarette smoke causes lung vascular barrier dysfunction via oxidative stress-mediated inhibition of RhoA and focal adhesion kinase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301((6)):L847–57. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00178.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakhatskyy P, et al. Cigarette smoke-induced lung endothelial apoptosis and emphysema are associated with impairment of FAK and eIF2α. Microvasc Res. 2014;94:80–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu Q, et al. Isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase modulates endothelial monolayer permeability: involvement of RhoA carboxyl methylation. Circ Res. 2004;94((3)):306–15. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000113923.85084.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stämpfli MR, Anderson GP. How cigarette smoke skews immune responses to promote infection, lung disease and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9((5)):377–84. doi: 10.1038/nri2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borgas D, et al. Cigarette smoke disrupted lung endothelial barrier integrity and increased susceptibility to acute lung injury via histone deacetylase 6. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54((5)):683–96. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0149OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z, et al. Mitochondrial fission mediated cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary endothelial injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2020;63((5)):637–51. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2020-0008OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gotts JE, et al. Cigarette smoke exposure worsens acute lung injury in antibiotic-treated bacterial pneumonia in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2018;315((1)):L25–40. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00405.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu Q, et al. Alda-1 protects against acrolein-induced acute lung injury and endothelial barrier dysfunction. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;57((6)):662–73. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0342OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guerassimov A, et al. The development of emphysema in cigarette smoke-exposed mice is strain dependent. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170((9)):974–80. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1270OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]