Abstract

Objective:

The present study tested the protective role of youth’s school-age extracurricular involvement and multiple informants’ reports of adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems in a sample of youth from low-income households.

Method:

Participating youth (n = 635, 49% female, 49% White, 28% Black/African American, 14% biracial, 8% other race, 13% Hispanic/Latinx) were drawn from the Early Steps Multisite Study. At ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5, primary caregivers reported the number of extracurricular activities for which youth participated (Parent Aftercare Survey). At ages 14 and 16, measures of internalizing and externalizing problems were collected from primary and alternate caregivers (Child Behavior Checklist) and target youth (Child Depression Inventory – Short Form, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, and Self-Report of Delinquency). At age 16, target youth also contributed measures of risky sexual behaviors and substance use (Youth Risk Behavior Survey). Teachers contributed measures of youth’s internalizing and externalizing problems at age 14 (Teacher Report Form).

Results:

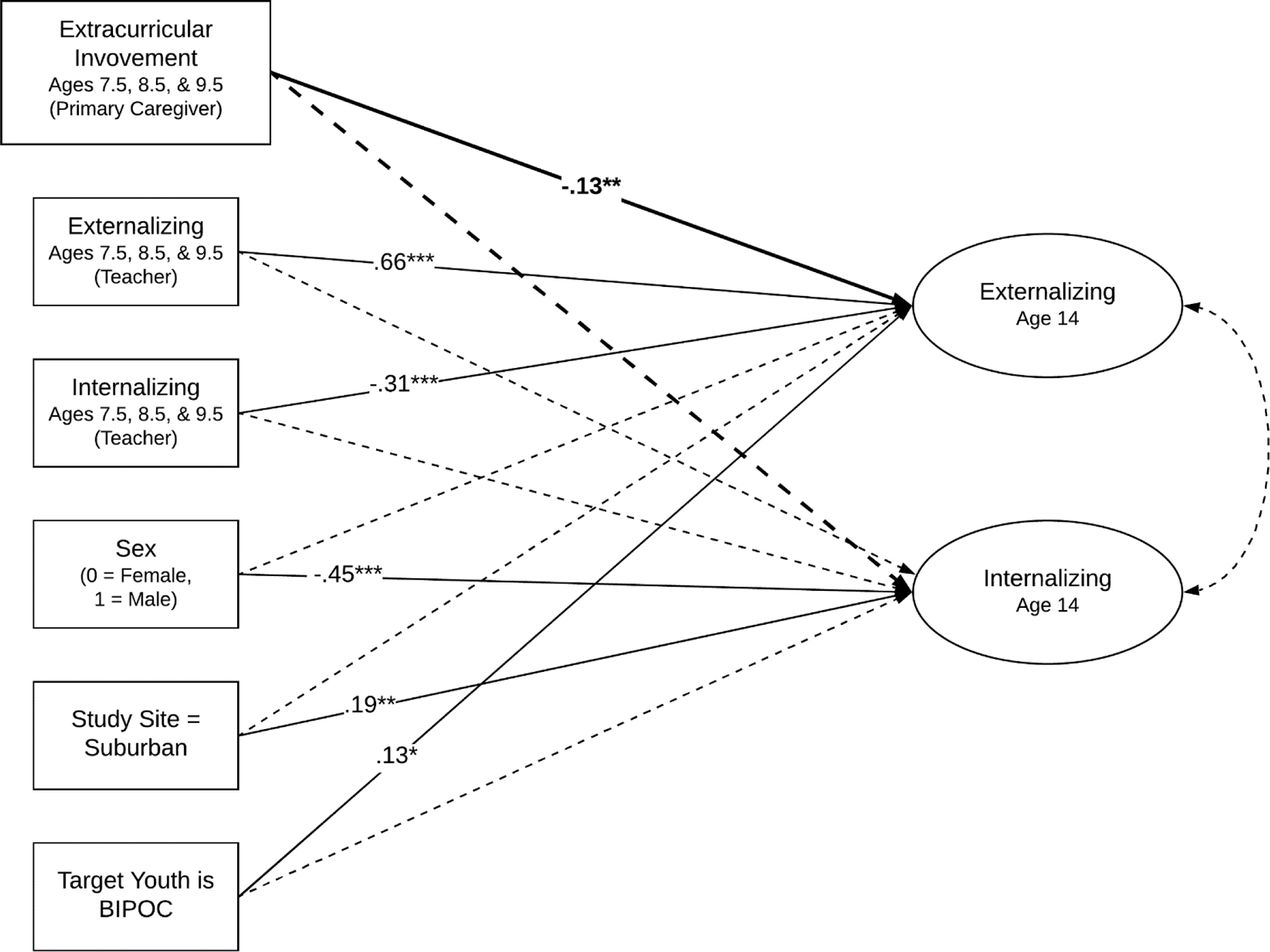

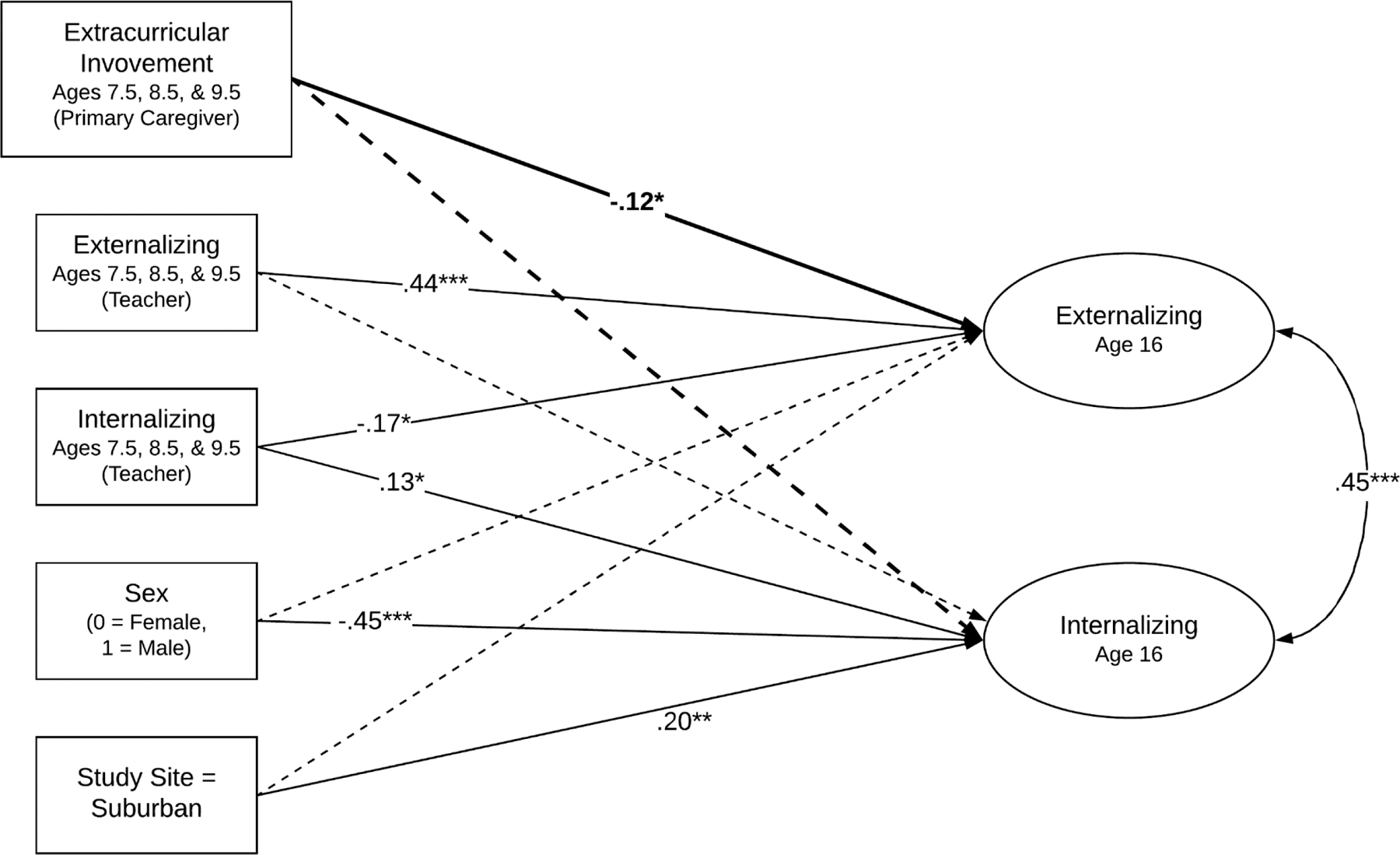

After accounting for the effects of multiple sociodemographic factors, initial levels of child problem behavior, and intervention group status, structural equation models revealed that school-age extracurricular involvement was inversely associated with latent factors representing adolescent externalizing, but not internalizing, problems at ages 14 (β = −.13, p < .01) and 16 (β = −.12, p = .02).

Conclusions:

The present study suggests that low-income, school-age children’s involvement in extracurricular activities serves a protective function in relation to adolescent externalizing problems. Future studies should assess underlying mechanisms and expand the scope of adolescent outcomes to include prosocial functioning.

Keywords: extracurricular, low-income, externalizing, internalizing

Although approximately two-thirds of American youth participate in after-school lessons, sports, or clubs, rates of participation are much lower for children from low-income households (Knop & Siebens, 2014). Youth from low-income households may face many challenges accessing extracurricular activities, beyond family-level financial constraints. For instance, in recent years many schools have cut funding for after-school activities, with low-income schools disproportionately being affected (Snellman, Silva, & Putnam, 2015). Beyond activities offered by schools, less affluent neighborhoods also tend to offer fewer extracurricular activities compared to more affluent neighborhoods because of neighborhood-level income constraints (Bennett et al., 2012; Dearing et al., 2009; Snellman, Silva, Frederick, et al., 2015). Even when available, children may be unable to participate in activities because of a lack of access to affordable transportation (Holloway & Pimlott-Wilson, 2014). Compared to more privileged peers, youth from low-income households are already at elevated risk for poor socioemotional and physical health outcomes (Duncan et al., 2010; Miller & Chen, 2013), and thus may be especially harmed by decreased access to extracurricular activities. However, research on the protective effects of extracurricular involvement for low-income youth is needed to inform policies that fight to retain funding for community activity offerings and encourage youth to participate in extracurricular activities. Thus, the present study attempts to improve understanding of the impact of school-age extracurricular involvement on socioemotional outcomes in adolescence.

Extracurricular involvement may protect youth from the development of socioemotional and behavioral problems in a myriad of ways. Depending on their content, activities may provide opportunities for youth to learn specific skills, express themselves creatively, become more physically active, and/or improve academic performance (Snellman, Silva, Frederick, et al., 2015). Such benefits provide youth opportunities for enjoyment and an empowering sense of self-efficacy which, in line with theories and research that support the use of behavioral activation for youth depression and anxiety (Bandura et al., 1999; Martin & Oliver, 2019; Muris, 2002), may prevent or dampen the onset of internalizing symptoms. Furthermore, participation in extracurricular activities allows for youth to be monitored by adults, while their caregivers may still be working when they get out of school. Adults who lead such prosocial extracurricular activities may also serve as positive role models and mentors for youth. Thus, extracurricular involvement may prevent youth from engaging in antisocial behavior via adult monitoring and reduced exposure to and affiliation with deviant peers (Dishion et al., 2002; Wright et al., 2010). In addition, the school-age years may be an especially important time as participation in prosocial activities may prevent early negative cascading processes, including the affiliation with deviant peers (Dishion et al., 2010), which often lead to the onset of adjustment problems prior to adolescence (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). Beyond preventing negative cascades associated with deviant peer affiliation, higher levels of engagement in prosocial behaviors have also consistently been found to be associated with lower levels of emotional and behavior problems for youth across childhood and adolescence (Memmott-Elison et al., 2020). Similar benefits have been found for youth adjustment in relation to social support (Chu et al., 2010), friendships with prosocial peers (Vitaro et al., 2009), and mentoring relationships (DuBois et al., 2011; Miranda-Chan et al., 2016).

Youth involvement in extracurricular activities in the school-age years has been associated with better socioemotional adjustment later in the school-age years (Aumètre & Poulin, 2018; Denault & Déry, 2015) and adolescence (Metsäpelto & Pulkkinen, 2012; Vandell et al., 2020). Similar concurrent benefits have been found for adolescents from low-income households (Abraczinskas et al., 2016); however, longitudinal research is lacking.

The present study assesses longitudinal associations between youth extracurricular involvement in the school-age years and multiple-informant reports of adolescent externalizing and internalizing problems. To test the reliability and generalizability of long-term associations, outcomes were assessed at both ages 14 and 16. We hypothesized that higher levels of extracurricular involvement in the school-age years would be associated with lower levels of youth externalizing and internalizing problems in adolescence after accounting for sociodemographic factors.

Method

Participants

Youth with data on their school-age extracurricular involvement (n = 635) were drawn from the larger cohort of the Early Steps Multisite study (N = 731). The Early Steps Multisite study is a randomized controlled trial designed to test the effectiveness of the Family Check-Up (FCU) intervention (Dishion et al., 2008). Families were recruited between 2002 and 2003 from Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Nutritional Supplement Centers in Pittsburgh, PA; Eugene, OR; and Charlottesville, VA. Families with a child between ages 2 years 0 months and 2 years 11 months were approached at WIC sites and screened for socioeconomic, family, and child risk factors for future behavior problems. Families who met criteria by demonstrating risk on at least two domains were invited to participate. A total of 1666 families were approached at WIC centers, 879 subsequently met the eligibility criteria, and 731 agreed to participate in the study. After recruitment, families were randomly assigned to receive the FCU intervention or WIC services as usual (control group).

Chi-square and independent samples t-tests revealed no significant difference between the analytic subsample and those excluded from the current study in intervention group status, household income (averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5), study site, child gender, child race, child ethnicity, teacher-reported internalizing or externalizing problems (averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5), or any of the age 14 or 16 outcome measures.

Procedures

Children and their caregivers were assessed 10 times between child ages 2 and 16. Institutional review boards at all participating universities approved the research and informed consent was obtained from caregivers at each age. Children provided informed assent starting at age 5. For the present study, data from the age 7.5, 8.5, 9.5, 14, and 16 assessments were used. Families participated in 1.5- to 3-hour home visits, during which primary caregivers (mostly biological mothers) completed demographic interviews and questionnaires about their children’s extracurricular involvement and psychosocial functioning (Feldman et al., 2021). The following individuals also contributed information about the target youth’s socioemotional adjustment: target youth (ages 14 and 16), alternate caregivers (i.e., adults identified by primary caregivers as someone who helped take care of the target youth; ages 7.5, 8.5, 9.5, 14, and 16), and teachers (ages 7.5, 8.5, 9.5, and 14). To select a teacher, primary caregivers and target youth were asked to provide the names of up to three teachers who knew the target youth best. If the first teacher on the list did not want to participate, then the second teacher on the list was asked and, if the second teacher also declined to participate, the third teacher was asked. If no teachers were identified, then the homeroom teacher was invited.

Measures

School-age extracurricular involvement.

At ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5, primary caregivers completed the Parent Aftercare Survey (PAS), a 69-item assessment of children’s after-school care adapted from measures used in the Promising After-School Practices Study (Feldman et al., 2021; Rosenthal & Vandell, 1996). A count of the different types of activities in which the target child participated during the past year was obtained and averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5 (α = .71). The following activities were included in the PAS measure: after school care (both informal and formal), clubs and organizations (e.g., Boys and Girls Club, Boy/Girl Scouts, and 4H), extra classes and formal tutoring, private and group lessons, religious classes and services, and sports teams. The present study’s measurement of extracurricular involvement is similar to other studies that have used composite scores of extracurricular involvement across multiple assessment periods (Metsäpelto & Pulkkinen, 2012; Vandell et al., 2020).

Adolescent socioemotional adjustment.

Caregivers’ responses on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) at ages 14 and 16 were used. The CBCL is a 120-item caregiver questionnaire for assessing emotional and behavioral problems in 4- to 18-year-olds. The broadband factors of Externalizing problems (35 items, αAge 14, PC = .94, αAge 14, AC = .92, αAge 16, PC = .93, αAge 16, AC = .94) and Internalizing problems (32 items, αAge 14, PC = .91, αAge 14, AC = .89, αAge 16, PC = .91, αAge 16, AC = .90) were used in the present study.

Teachers contributed measures of child adjustment using the Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) at child ages 7.5, 8.5, 9.5, and 14. As with the CBCL, the broadband factors of Externalizing and Internalizing problems were used in the present study. Adequate internal consistency was demonstrated at age 14 for both the Internalizing (33, items, α = .88) and Externalizing factors (32 items, α = .95). Furthermore, an average score of teacher-reported adjustment in the school-age years was included as a covariate in analyses.

At ages 14 and 16, target youth completed measures that assessed symptoms of psychopathology and risky behaviors. Depressive symptoms were measured using the Child Depression Inventory – Short Form (CDI-S; Kovacs, 2003) (10 items, αAge 14 = .83, αAge 16 = .86). Symptoms of anxiety were measured using the short form of the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC-10; March, 1998) (10 items, αAge 14 = .78, αAge 16 = .79). Antisocial behavior was measured using the Self-Report of Delinquency (SRD; Elliott et al., 1985) (46 items, αAge 14 = .90, αAge 16 = .91). Higher scores on the CDI, MASC, and SRD indicate higher levels of socioemotional maladjustment. Furthermore, at age 16 target youth also responded to items about risky sexual and drug-related behaviors from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Items from the YRBS were dichotomized (0 = no, 1 = yes) prior to analyses.

Covariates.

Target youth sex (0 = female, 1 = male), ethnicity (0 = not Hispanic/Latinx, 1 = Hispanic/Latinx), race (0 = White, 1 = Black, Indigenous, or Person of Color [BIPOC]), household income (averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5), and study site (dummy coded with Pittsburgh, PA as reference group) were included as covariates in multivariate analyses. Furthermore, teacher reports of school-age internalizing and externalizing problems on the TRF (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) were averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5 and included as covariates.

Analytic Plan

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of study variables were computed in SPSS Version 26. Structural equation modeling was conducted in Mplus Version 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2020) to assess the hypotheses in a multivariate framework. Full-information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was used to estimate missing data (nAge 14 = 85, 13%; nAge 16 = 50, 8%)1 (Enders & Bandalos, 2001). Latent factors for Externalizing and Internalizing problems were estimated at ages 14 and 16. After assessing the integrity of the latent factors, pathways between school-age extracurricular involvement (averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5) and youth’s Externalizing and Internalizing problems were estimated in separate age 14 and 16 models. Target youth sex, ethnicity, race, school-age household income, study site, and school-age teacher-reported internalizing and externalizing problems were entered as covariates. Prior to analyses, all variables were assessed and confirmed to meet required standards for normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity. Model fit was assessed using the Chi-square ratio (χ2/df = 1 to 3), comparative fit index (CFI > .90), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .05 for good fit, RMSEA < .08 for acceptable fit) (McDonald & Ho, 2002).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics of study variables are presented in Table 1. T-scores are presented for the CBCL and TRF (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) outcomes in Table 1 to provide comparison with normative averages. However, raw scores were utilized in analyses to maximize variability. Correlations between study variables are presented in Table 2. School-age extracurricular involvement was negatively correlated with externalizing (rAge 14 = −.10, rAge 16 = −.11, ps < .05), but not internalizing (rAge 14 = .18, rAge 16 = .02, ps > .05), problems at ages 14 and 16. Youth were involved in significantly more extracurricular activities when they were female, BIPOC, and non-Hispanic/Latinx.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables

| Variable | Reporter |

M (SD) or n (%) Ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extracurricular involvement | PC | 2.37 (1.33) | ||

| Internalizing | Teacher | 55.26 (8.78) | ||

| Externalizing | Teacher | 56.07 (9.15) | ||

| Annual income | PC | $28441.47 ($16623.00) | ||

| Target youth sex | PC | Female | 311 (49%) | |

| Male | 324 (51%) | |||

| Target youth ethnicity | PC | Hispanic/Latinx | 84 (13%) | |

| Not Hispanic/Latinx | 534 (84%) | |||

| Unknown | 17 (3%) | |||

| Target youth race | PC | Biracial | 89 (14%) | |

| Black/African American | 180 (28%) | |||

| White | 312 (49%) | |||

| Other | 49 (8%) | |||

| Unknown | 5 (1%) | |||

| Study site | Charlottesville, VA | 158 (25%) | ||

| Eugene, OR | 239 (38%) | |||

| Pittsburgh, PA | 238 (38%) | |||

| Group | Control | 320 (50%) | ||

| Intervention | 315 (50%) | |||

| Age 14 | Age 16 | |||

|

| ||||

| Internalizing | PC | 54.33 (12.19) | 54.22 (12.14) | |

| Internalizing | AC | 51.88 (10.63) | 50.16 (11.99) | |

| Internalizing | Teacher | 54.00 (9.68) | ||

| Depression | Youth | 4.22 (5.32) | 13.15 (3.74) | |

| Anxiety | Youth | 1.15 (.57) | 1.05 (.58) | |

| Externalizing | PC | 54.32 (11.74) | 52.90 (11.40) | |

| Externalizing | AC | 53.01 (10.87) | 49.86 (11.57) | |

| Externalizing | Teacher | 54.78 (10.19) | ||

| Antisocial behavior | Youth | 5.78 (7.19) | 5.55 (7.00) | |

| Marijuana use | Youth | 165 (30%) | ||

| Tobacco use | Youth | 90 (17%) | ||

| Vape use | Youth | 141 (26%) | ||

| Alcohol use | Youth | 198 (37%) | ||

| No condom last time | Youth | 62 (11.5%) | ||

| Sex with stranger | Youth | 45 (8.3%) | ||

Note. PC = primary caregiver. AC = alternate caregiver.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Between Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. School-age extracurricular | |||||||||||||

| 2. School-age int. | .24 | ||||||||||||

| 3. School-age ext. | .05 | .50*** | |||||||||||

| 4. Household income | .07 | −.12* | −.16** | ||||||||||

| 5. Sex (0 = female, 1 = male) | −.08* | −.17*** | .26*** | .02 | |||||||||

| 6. Hispanic/Latinx (0 = no, 1 = yes) | −.13** | −.14** | −.13** | .02 | −.02 | ||||||||

| 7. Race (0 = White, 1= BIPOC) | .15*** | .03 | .22*** | −.22*** | −.04 | −.33*** | |||||||

| 8. Site = Charlottesville, VA | .07 | −.04 | −.05 | .03 | −.01 | .12** | .09* | ||||||

| 9. Site = Eugene, OR | −.09* | −.01 | −.12** | .09* | .02 | .16*** | −.40*** | −.45*** | |||||

| 10. Group (0 = control, 1 = intervention) | .04 | −.04 | −.07 | .00 | −.02 | .00 | −.02 | .00 | .03 | ||||

| 11. Int. (age 14) | .18 | .21** | −.22*** | −.04 | −.47*** | −.01 | −.02 | −.02 | .17** | .01 | |||

| 12. Ext. (age 14) | −.10* | .02 | .52*** | −.14* | .26*** | .05 | .05 | −.08 | −.14** | −.02 | .31*** | ||

| 13. Int. (age 16) | .02 | .06 | −.26*** | .01 | −.45*** | −.02 | −.04 | −.06 | .21*** | .03 | .95*** | .37*** | |

| 14. Ext. (age 16) | −.11* | .01 | .39*** | −.05 | .25*** | .07 | −.02 | −.03 | −.13* | −.01 | .48*** | .82*** | .33*** |

Note. Int. = internalizing latent factor. Ext. = externalizing latent factor. BIPOC = Black, Indigenous, or Person of Color. Full correlation table with raw variables available per request.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Externalizing and Internalizing Latent Factors

Externalizing and Internalizing latent factors were estimated within the same measurement model at ages 14 and 16. The latent factors demonstrated adequate model fit at ages 14 (χ2/df = 4.79; RMSEA = .08, 90% CI = [.07,.10]; CFI = .95) and 16 (χ2/df = 1.86; RMSEA = .04, 90% CI = [.02,.05]; CFI = .99). Factor loadings were all significant and in the expected directions (Table 3). Latent factors for Externalizing and Internalizing factors were significantly correlated at ages 14 (r = .31, p < .001) and 16 (r = .33, p < .001).

Table 3.

Variable Loadings for Externalizing and Internalizing Latent Factors at Ages 14 and 16

| Variable | Reporter | β (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age 14 | Age 16 | ||

| Internalizing Latent Factor | |||

| Internalizing | PC | .56 (.06) | .50 (.05) |

| Internalizing | AC | .46 (.07) | .34 (.05) |

| Internalizing | Teacher | .52 (.05) | |

| Depression | Youth | .59 (.07) | .77 (.05) |

| Anxiety | Youth | .42 (.07) | .57 (.05) |

| Externalizing Latent Factor | |||

| Externalizing | PC | .64 (.05) | .54 (.08) |

| Externalizing | AC | .45 (.06) | .50 (.08) |

| Externalizing | Teacher | .60 (.04) | |

| Antisocial behavior | Youth | .69 (.04) | .70 (.10) |

| Marijuana use | Youth | .39 (.08) | |

| Tobacco use | Youth | .39 (.08) | |

| Vape use | Youth | .30 (.08) | |

| Alcohol use | Youth | .30 (.08) | |

| No condom last time | Youth | .37 (.08) | |

| Sex with stranger | Youth | .36 (.07) | |

Note. PC = primary caregiver. AC = alternate caregiver.

All factor loadings are significant at p < .001.

Relations between School-Age Extracurricular Involvement and Adolescent Adjustment

Model fit was adequate for structural models at ages 14 (Figure 1; χ2/df = 2.20; RMSEA = .04, 90% CI = [.04,.05]; CFI = .92) and 16 (Figure 2; χ2/df = 1.70; RMSEA = .03, 90% CI = [.03,.04]; CFI = .96). Higher levels of extracurricular involvement were associated with lower Externalizing at ages 14 and 16 (βAge 14 = −.13, p < .01, 95% CI [−.22, −.04]; βAge 16 = −.12, p = .02, 95% CI [−.23, −.02]), but not Internalizing (βAge 14 = .01, p = .92, 95% CI [−.09, .10]; βAge 16 = −.04, p = .39, 95% CI = [−.14, .05]), problems.

Figure 1:

Note. Longitudinal relations between school-age extracurricular involvement and age 14 internalizing and externalizing problems. Covariates include teacher reported externalizing and internalizing problems (averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5), study site (Pittsburgh, PA as reference group; rural not in figure), target youth race (BIPOC = Black, Indigenous, or Person of Color), target youth ethnicity (not in figure), target youth sex, and intervention group (not in figure). All paths were estimated, but only significant predictors with their standardized β values are reported. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Figure 2:

Note. Longitudinal relations between school-age extracurricular involvement and age 16 internalizing and externalizing problems. Covariates included teacher-reported externalizing and internalizing problems (averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5), study site (Pittsburgh, PA as reference group; rural not in figure), target youth race (not in figure), target youth ethnicity (not in figure), target youth sex, and intervention group (not in figure). All paths were estimated, but only significant predictors with their standardized β values are reported. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Discussion

Consistent with prior literature on benefits of school-age extracurricular involvement for adolescent development across levels of family income (Metsäpelto & Pulkkinen, 2012; Vandell et al., 2020), we found similarly positive effects for youth from low-income households. Specifically, higher levels of extracurricular involvement in the school-age years were associated with lower levels of adolescent externalizing problems at ages 14 and 16. Unexpectedly, extracurricular involvement was not longitudinally associated with internalizing problems.

The unique associations between extracurricular involvement and externalizing problems, but not internalizing problems, were surprising because prior longitudinal work has tended to find stronger support for associations between lower levels of extracurricular involvement and higher rates of later internalizing problems, relative to externalizing problems (e.g., Aumètre & Poulin, 2018; Metsäpelto & Pulkkinen, 2012). Studies on participation in after-school sports, in particular, have found support for significant associations with lower internalizing, but not externalizing, problems (Findlay & Coplan, 2008; Metsäpelto & Pulkkinen, 2012; Moeijes et al., 2018). However, none of the aforementioned studies included samples comprised exclusively of low-income youth, as in the current study. Further, many prior studies on the benefits of school-age extracurricular involvement have been conducted in countries outside of the United States. Thus, prior longitudinal research on the benefits of extracurricular involvement may not generalize to youth from low-income households, which may explain the discrepancy in findings. Further, our findings may be attributed to the characteristics of the activities. Namely, the adult-led nature of all extracurricular activities likely provide opportunities for youth to be monitored and build relationships with prosocial role models, both of which may protect youth from deviant peer affiliation and thus decrease their risk for developing externalizing problems (Dishion et al., 2002; Wright et al., 2010). Conversely, extracurricular activities may be more likely to protect youth from internalizing problems when the youth wants to participate and when the activity provides specific opportunities for enjoyment and the development of self-efficacy (Bandura et al., 1999; Martin & Oliver, 2019; Muris, 2002). However, we did not ask caregivers to report on why children were involved in different activities, which should be an important goal for future studies. Children who are participating in an activity because they want to may benefit emotionally more than children who are participating because their caregiver insists that they do. Furthermore, not all of the activities included in the present study’s measure would necessarily contribute to youth’s sense of enjoyment and self-efficacy, such as informal after school care. Accordingly, involvement in organized activities, but not supervised care, in the school-age years has been found to be associated with youth positive adjustment in adolescence (Vandell et al., 2020). Thus, although all of the activities included may have protected youth from the development of externalizing problems, a more nuanced measure of the activities may be needed to assess relations between extracurricular involvement and internalizing problems. It is important that future studies test hypothesized mechanisms that may link extracurricular involvement to lower externalizing problems (i.e., monitoring and lower deviant peer affiliation) and internalizing problems (i.e., activity type and initiator).

Strengths of the current study include the inclusion of a large sample of children from low-income households across diverse geographic regions of the United States, the longitudinal design, and the inclusion of multiple informants of adolescent adjustment. Furthermore, the inclusion of important covariates in the analytic models (e.g., family income and teacher-reported school-age socioemotional adjustment) strengthen our conclusions. However, the study also has important limitations. First, as alluded to previously, the measure of extracurricular activity involvement was simple and did not allow for more detailed analyses, such as the amount of time youth spent in activities or whether or not the youth actually enjoyed participating. Relatedly, in the present study, daily participation in an extracurricular activity counts the same as an activity that a youth participated in less frequently. Measures of extracurricular involvement frequency and enjoyment should be included in future studies to better understand how different types of extracurricular activities may uniquely benefit youth development in samples of youth from low-income households. Second, given that youth in the present study are now approaching adulthood, it will be important to replicate findings with cohorts of school-age youth who are currently involved in extracurricular activities to rule out cohort effects and increase generalizability.

Despite these limitations, findings from the present study suggest that extracurricular involvement in the school-age years serve as important protective factors for youth from low-income households. Thus, it is especially concerning that youth from low-income households have unique barriers to accessing extracurricular activities (Bennett et al., 2012; Dearing et al., 2009; Holloway & Pimlott-Wilson, 2014; Snellman, Silva, & Putnam, 2015). To further strengthen our conclusions, future studies should attempt to expand generalizability by replicating current findings in samples of children with varying levels of socioemotional and economic risk factors. Furthermore, future studies should include assessments of positive developmental outcomes associated with extracurricular involvement, such as relationships with mentors and academic achievement, and outcomes associated with specific types of extracurricular activities. Finally, the benefits of extracurricular programs that have integrated mental health services should also be explored (e.g., Frazier et al., 2012), as they may provide additional protective benefits for youth and may be better equipped to support youth who have preexisting socioemotional problems. Such research may inform communities with limited resources as to which extracurricular activities to prioritize offering.

Public Health Significance:

This study suggests that extracurricular involvement in the school-age years protects youth from low-income households from developing behavior problems in adolescence.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by grant to authors Shaw and Wilson from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) under Grant DA016110. We also would like to extend our thanks to staff of the Early Steps Multisite Study and the families who have participated in the project over the past two decades.

Appendix 1. Narrative Description of Previously Published Literature

The data reported in this manuscript have been previously published and were collected as part of a larger data collection. Findings from the data collection have been reported in separate manuscripts. A full list of manuscripts may be found at http://www.ppcl.pitt.edu/publications/early-steps-multisite-study-publications. MS1 includes school-age extracurricular involvement as a primary outcome, rather than an independent variable. Adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems were included as outcome variables in MS2, MS3, and MS4. However, the current manuscript assesses longitudinal relations between school-age extracurricular involvement and adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Chi-square and independent samples t-tests revealed no significant difference between the youth with and without ages 14 or 16 outcomes on school-age household income, child gender, child race, school-age teacher-reported internalizing or externalizing problems, or school-age extracurricular involvement. However, youth with missing data were more likely to be Hispanic/Latinx than youth without missing data at age 14 (χ2 (2) = 10.30, p < 05) and 16 (χ2 (2) = 7.90, p < 05). Youth with missing data at age 16 were also more likely to live in Charlottesville, VA and less likely to live in Pittsburgh, PA than youth without missing data (χ2 (2) = 16.02, p < 05).

Data availability:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, JSF, upon reasonable request.

References

- Abraczinskas M, Kilmer R, Haber M, Cook J, & Zarrett N (2016). Effects of extracurricular participation on the internalizing problems and intrapersonal strengths of youth in a system of care. American Journal of Community Psychology, 57(3–4), 308–319. 10.1002/ajcp.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families [Google Scholar]

- Aumètre F, & Poulin F (2018). Academic and behavioral outcomes associated with organized activity participation trajectories during childhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 54, 33–41. 10.1016/j.appdev.2017.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Pastorelli C, Barbaranelli C, & Caprara GV (1999). Self-efficacy pathways to childhood depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(2), 258–269. 10.1037//0022-3514.76.2.258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett PR, Lutz AC, & Jayaram L (2012). Beyond the schoolyard: The role of parenting logics, financial resources, and social institutions in the social class gap in structured activity participation. Sociology of Education, 85(2), 131–157. 10.1177/0038040711431585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS): Item rationale for the 2009 core questionnaire http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/pdf/questionnaire/2009ItemRationale.pdf

- Chu PS, Saucier DA, & Hafner E (2010). Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(6), 624–645. 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.6.624 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E, Wimer C, Simpkins SD, Lund T, Bouffard SM, Caronongan P, Kreider H, & Weiss H (2009). Do neighborhood and home contexts help explain why low-income children miss opportunities to participate in activities outside of school? Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1545–1562. 10.1037/a0017359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denault A-S, & Déry M (2015). Participation in organized activities and conduct problems in elementary school: The mediating effect of social skills. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 23(3), 167–179. 10.1177/1063426614543950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Bullock BM, & Granic I (2002). Pragmatism in modeling peer influence: Dynamics, outcomes, and change processes. Development and Psychopathology, 14(04), 969–981. 10.1017/S0954579402004169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, & Wilson M (2008). The Family Check-Up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development, 79(5), 1395–1414. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Véronneau M-H, & Myers MW (2010). Cascading peer dynamics underlying the progression from problem behavior to violence in early to late adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 22(03), 603–619. 10.1017/S0954579410000313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Portillo N, Rhodes JE, Silverthorn N, & Valentine JC (2011). How effective are mentoring programs for youth? A systematic assessment of the evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12(2), 57–91. 10.1177/1529100611414806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Ziol-Guest KM, & Kalil A (2010). Early-childhood poverty and adult attainment, behavior, and health. Child Development, 81(1), 306–325. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01396.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, & Ageton SS (1985). Explaining delinquency and drug use. Sage. Enders, C., & Bandalos, D. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 8(3), 430–457. 10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JS, Zhou Y, Weaver Krug C, Wilson MN, & Shaw DS (2021). Indirect effects of the Family Check‐Up on youth extracurricular involvement at school‐age through improvements in maternal positive behavior support in early childhood. Social Development, 30(1), 311–328. 10.1111/sode.12474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay LC, & Coplan RJ (2008). Come out and play: Shyness in childhood and the benefits of organized sports participation. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 40(3), 153–161. 10.1037/0008-400X.40.3.153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier SL, Chacko A, Van Gessel C, O’Boyle C, & Pelham WE (2012). The summer treatment program meets the south side of Chicago: Bridging science and service in urban after-school programs. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 17(2), 86–92. 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00614.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway SL, & Pimlott-Wilson H (2014). Enriching children, institutionalizing childhood? Geographies of play, extracurricular activities, and parenting in England. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 104(3), 613–627. 10.1080/00045608.2013.846167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knop B, & Siebens J (2014). A child’s day: Parental interaction, school engagement, and extracurricular activities (Current Population Reports, pp. 70–159). U. S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M (2003). Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI): Technical manual update. Multi-Health Systems

- March J (1998). Manual for the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC). Multi-Health Systems [Google Scholar]

- Martin F, & Oliver T (2019). Behavioral activation for children and adolescents: A systematic review of progress and promise. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(4), 427–441. 10.1007/s00787-018-1126-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, & Cicchetti D (2010). Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22(03), 491–495. 10.1017/S0954579410000222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, & Ho M-HR (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64–82. 10.1037//1082-989X.7.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memmott-Elison MK, Holmgren HG, Padilla-Walker LM, & Hawkins AJ (2020). Associations between prosocial behavior, externalizing behaviors, and internalizing symptoms during adolescence: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 80, 98–114. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metsäpelto R-L, & Pulkkinen L (2012). Socioemotional behavior and school achievement in relation to extracurricular activity participation in middle childhood. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 56(2), 167–182. 10.1080/00313831.2011.581681 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, & Chen E (2013). The biological residue of childhood poverty. Child Development Perspectives, 7(2), 67–73. 10.1111/cdep.12021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Chan T, Fruiht V, Dubon V, & Wray-Lake L (2016). The functions and longitudinal outcomes of adolescents’ naturally occurring mentorships. American Journal of Community Psychology, 57(1–2), 47–59. 10.1002/ajcp.12031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeijes J, van Busschbach JT, Bosscher RJ, & Twisk JWR (2018). Sports participation and psychosocial health: A longitudinal observational study in children. BMC Public Health, 18(1). 10.1186/s12889-018-5624-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P (2002). Relationships between self-efficacy and symptoms of anxiety disorders and depression in a normal adolescent sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(2), 337–348. 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00027-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R & Vandell DL (1996). Quality of care at school-aged child-care programs: Regulatable features, observed experiences, child perspectives, and parent perspectives. Child Development, 67(5), 2434–2445. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01866.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snellman K, Silva JM, Frederick CB, & Putnam RD (2015). The engagement gap: Social mobility and extracurricular participation among American youth. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 657(1), 194–207. 10.1177/0002716214548398 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snellman K, Silva JM, & Putnam RD (2015). Inequity outside the classroom: Growing class differences in participation in extracurricular activities. VUE, 40, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Vandell DL, Lee KTH, Whitaker AA, & Pierce KM (2020). Cumulative and differential effects of early child care and middle childhood out-of-school time on adolescent functioning. Child Development, 91(1), 129–144. 10.1111/cdev.13136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Boivin M, & Bukowski WM (2009). The role of friendship in child and adolescent psychosocial development. In Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, & Laursen B (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 568–585). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wright R, John L, Duku E, Burgos G, Krygsman A, & Esposto C (2010). After-school programs as a prosocial setting for bonding between peers. Child & Youth Services, 31(3–4), 74–91. 10.1080/0145935X.2009.524461 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, JSF, upon reasonable request.