Summary

Tafasitamab and lenalidomide was approved for second-line treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) based on a single-arm phase II study. This combination was superior to routine immunochemotherapy regimens when comparing matched observational cohorts. “Synthetic” control groups may support use of novel DLBCL therapies in the absence of randomized studies.

In this issue of Clinical Cancer Research, Nowakowski and colleagues performed an observational retrospective matched cohort study(1) to compare outcomes of patients treated with tafasitamab and lenalidomide on the L-MIND clinical trial(2) (NCT02399085) with real-world matched patients treated with any systemic therapies, bendamustine and rituximab (BR), or rituximab and gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (R-GemOx). Tafasitamab, an anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody, combined with the immunomodulator lenalidomide, gained approval based a single-arm phase II study of patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) ineligible for autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). The RE-MIND study used propensity score-matching and weighting of nine baseline variables to compare a cohort of patients treated on L-MIND with a real-world retrospective cohort treated with lenalidomide monotherapy(3). Tafasitamab and lenalidomide demonstrated clear superiority in overall response rates (ORR), progression free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) over single-agent lenalidomide. In the RE-MIND2 article, the authors compare tafasitamab and lenalidomide in a similar manner to routinely used immunochemotherapy regimens.

The exclusion criteria of L-MIND (maximum of 3 prior lines of therapy, no primary refractory disease, no double-hit lymphoma) enriched for patients with lower risk characteristics compared to similar single-arm studies of other novel agents(2,4,5). Lower-intensity immunochemotherapy regimens such as BR or R-GemOx may also have improved efficacy in lower risk patients, historically a population with greater chemotherapy sensitivity. The authors addressed this possibility effectively by comparing patients from L-MIND with real-world patients from a large, multi-center observational cohort using propensity score-based 1:1 matching, balanced for 9 baseline characteristics, including age, disease stage, number of prior lines of therapy, primary refractory disease, and prior ASCT(1).

Three comparisons were made to independent cohorts of real-world patients receiving any systemic therapy (N=76), BR (75), or R-GemOx (74). Tafasitamab and lenalidomide demonstrated prolonged OS, PFS, duration of response, and time to next treatment compared to all 3 cohorts. Sensitivity analysis adding additional balancing covariates and subset analysis stratifying patients by baseline characteristics of interest corroborated the findings.

This study represents a growing trend of using “synthetic” control groups to contextualize the findings of single-arm prospective studies of novel agents. RE-MIND and RE-MIND2 evaluated tafasitamab and lenalidomide, whereas a similar approach was employed for patients treated with the CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) on the single-arm ZUMA-1 study(6) and the SCHOLAR-1 pooled cohort of patients with refractory DLBCL(7). Propensity scoring incorporated 7 baseline covariates to match the compared cohorts and demonstrated that axi-cel led to an improved ORR and 73% reduction in risk of death over traditional therapies(8). CAVALLI was a phase Ib/II study evaluating the modified frontline regimen of venetoclax plus rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP)(9). An unbalanced comparison with the R-CHOP control group from the prospective GOYA phase III study(10) suggested improved PFS in the overall population as well as BCL2 positive subgroup with the addition of venetoclax.

A randomized control study can only make a limited number of comparisons at a time, and its control arm may become outdated by the time of analysis. Synthetic control groups identified using robust statistical methodology as described here represent an alternative resource to answer current research questions in an evolving field, albeit with the caveats of comparing real-world and clinical trial-treated patients. For example, only 14% of patients from L-MIND were ASCT-ineligible due to medical comorbidities(2), but an equivalent statistic was not available for the matched cohorts from RE-MIND2(1). If a greater prevalence of comorbidities precluding clinical trial enrollment was present in real-world patients, that could influence differences in OS and bias results even with otherwise matched patients. Thorough capture of relevant baseline covariates in real-world datasets used for matched comparisons is essential. Synthetic control comparisons are not a replacement for randomized studies, but are a powerful tool to improve our capacity to minimize biases which often make comparisons of distinct cohorts difficult.

The treatment landscape for R/R DLBCL has seen numerous changes with approvals of novel agents including polatuzumab vedotin with BR(4), tafasitamab and lenalidomide(2), selinexor(11), loncastuximab tesirine(5), in addition to 3 CAR T-cell products(6,12,13). Axi-cel gained Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for second-line treatment of DLBCL refractory to or relapsing within one year of first-line therapy based on the randomized phase III ZUMA-7 study (14). Lisocabtagene maraleucel identified similar results to ZUMA-7, and potentially could be approved as a second-line therapy as well(15,16).

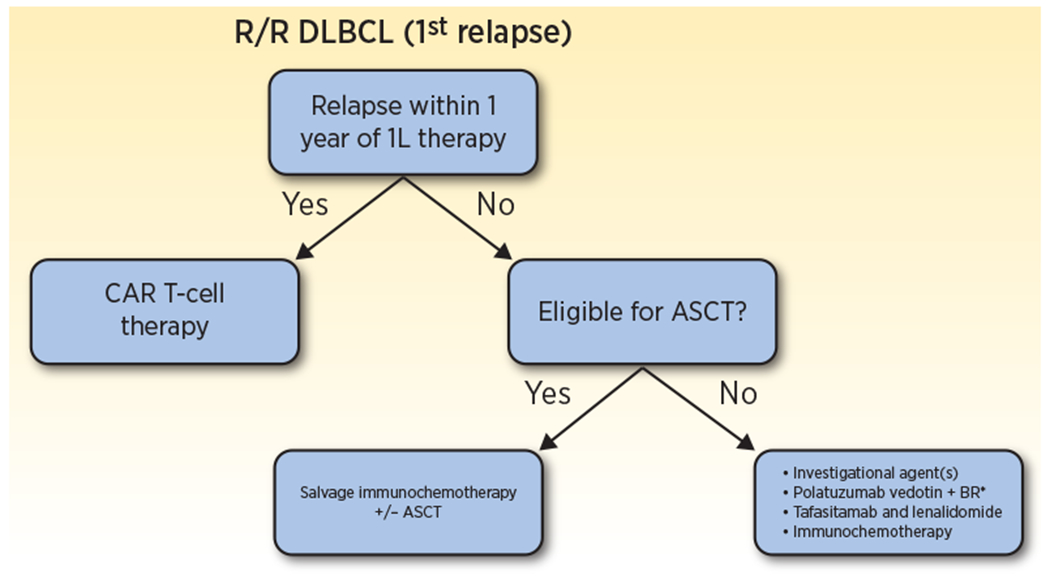

What do RE-MIND and RE-MIND2 mean for tafasitamab and lenalidomide in patients with R/R DLBCL? Patients can receive tafasitamab and lenalidomide after first relapse, with RE-MIND2 demonstrating improved outcomes in comparison with lower-intensity immunochemotherapy regimens. Polatuzumab vedotin with BR is the only other novel therapy listed as a second-line option in the NCCN guidelines(17), though this only carries an FDA approval for third-line treatment; this analysis did not address comparisons to other novel agents. Time to first progression should be used to guide second treatment choice. Patients progressing within one year of primary therapy should be referred to CAR T-cell therapy centers as quickly as possible. ASCT-ineligible patients with first relapse beyond 12 months have multiple treatment options: we suggest that patients could receive tafasitamab and lenalidomide as a continuous therapy, clinical trial treatments, other immunochemotherapy regimens, or polatuzumab vedotin with BR. A suggested treatment algorithm is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Suggested treatment algorithm for patients with R/R DLBCL after one prior line of systemic therapy ineligible for autologous stem cell transplant.

Patients with R/R DLBCL after first-line treatment should be stratified by time to first relapse. Patients with refractory disease or disease that relapses within one year should proceed directly to CAR T-cell therapy. Late relapsers should be evaluated for candidacy for high dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant. Candidates should pursue salvage platinum-based immunochemotherapy followed by transplant in responders, while patients ineligible for transplant have multiple treatment options, including continuous tafasitamab plus lenalidomide, clinical trials, immunochemotherapy regimens, or polatuzumab vedotin with BR.

*Polatuzumab vedotin with BR is listed as a second-line treatment in the NCCN guidelines, though does not carry an FDA approval for this indication.

R/R, relapsed or refractory; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; 1L, first-line; CAR T-cell, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; BR, bendamustine and rituximab.

The data presented by Nowakowski and colleagues(1) demonstrate the utility of synthetic control comparisons between patients treated on single-arm clinical trials and matched patients from real-world cohorts when randomized studies are not feasible. Though such analyses are confounded by biases inherent in comparing clinical trial and real-world patients that are unlikely to completely match patients, they may still offer some guidance, and should be pre-planned for future non-randomized studies. In addition, patients treated with standard of care tafasitamab and lenalidomide should be analyzed against patients treated with other standard of care options. Tafasitamab and lenalidomide appears preferable to some immunochemotherapy regimens in reducing risk of death, and we eagerly anticipate analysis of additional matched comparisons with patients receiving other approved novel therapies for R/R DLBCL from the RE-MIND2 cohort(18).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the MD Anderson NIH/NCI Cancer Support Grant under award number P30 CA016672 (to HJC and JW).

Conflicts of interest

HJC declares no potential conflicts of interest. JW has research funding from Kite/Gilead, BMS, Novartis, Genentech/Roche, Morphosys/Incyte, AstraZeneca, ADC Therapeutics, and consulting funding for Kite/Gilead, BMS, Novartis, Genentech/Roche, Morphosys/Incyte, AstraZeneca, ADC Therapeutics, Merck, MonteRosa, Umoja, and Ikusda.

References

- 1.Nowakowski GS, Yoon DH, Peters A, Mondello P, Joffe E, Fleury I, et al. Improved efficacy of tafasitamab + lenalidomide versus systemic therapies for relapsed/refractory DLBCL: RE-MIND2, an observational retrospective matched cohort study. Clin Cancer Res 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salles G, Duell J, González Barca E, Tournilhac O, Jurczak W, Liberati AM, et al. Tafasitamab plus lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (L-MIND): a multicentre, prospective, single-arm, phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncology [Internet]. 2020. Jul 1 [cited 2022 Jun 1];21(7):978–88. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S1470204520302254/fulltext [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zinzani PL, Rodgers T, Marino D, Frezzato M, Barbui AM, Castellino C, et al. RE-MIND: Comparing Tafasitamab + Lenalidomide (L-MIND) with a Real-world Lenalidomide Monotherapy Cohort in Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res [Internet]. 2021. Nov 15 [cited 2022 May 31];27(22):6124–34. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34433649/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sehn LH, Herrera AF, Flowers CR, Kamdar MK, McMillan A, Hertzberg M, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020. Nov 6;38(2):155–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caimi PF, Ai W, Alderuccio JP, Ardeshna KM, Hamadani M, Hess B, et al. Loncastuximab tesirine in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (LOTIS-2): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology [Internet]. 2021. Jun 1 [cited 2022 Jun 1];22(6):790–800. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S147020452100139X/fulltext [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, Lekakis LJ, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2017. Dec 28 [cited 2020 Jul 26];377(26):2531–44. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1707447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crump M, Neelapu SS, Farooq U, van den Neste E, Kuruvilla J, Westin J, et al. Outcomes in refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the international SCHOLAR-1 study. Blood [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2019 Oct 19];130(16):1800–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28774879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, Lekakis LJ, Reagan PM, Miklos DB, et al. Comparison of 2-year outcomes with CAR T cells (ZUMA-1) vs salvage chemotherapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Advances [Internet]. 2021. Oct 26 [cited 2021 Nov 26];5(20):4149–55. Available from: http://ashpublications.org/bloodadvances/article-pdf/5/20/4149/1830015/advancesadv2020003848.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morschhauser F, Feugier P, Flinn IW, Gasiorowski R, Greil R, Illes A, et al. A phase II study of venetoclax plus R-CHOP as first-line treatment for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood [Internet]. 2020. Sep 21 [cited 2020 Oct 11]; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32959049/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitolo U, Trneny M, Belada D, Burke JM, Carella AM, Chua N, et al. Obinutuzumab or rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone in previously untreated diffuse large b-cell lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017. Nov 1;35(31):3529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalakonda N, Maerevoet M, Cavallo F, Follows G, Goy A, Vermaat JSP, et al. Selinexor in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (SADAL): a single-arm, multinational, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial [Internet]. Vol. 7, The Lancet Haematology. 2020. [cited 2020 Aug 3]. Available from: www.thelancet.com/haematology [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, Waller EK, Borchmann P, McGuirk JP, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2019. Jan 3 [cited 2020 Jul 26];380(1):45–56. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1804980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, Lunning MA, Wang M, Arnason J, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. The Lancet [Internet]. 2020. Sep 19 [cited 2021 Mar 17];396(10254):839–52. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140673620313660/fulltext [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locke FL, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, Perales MA, Kersten MJ, Oluwole OO, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel as Second-Line Therapy for Large B-Cell Lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2022. Feb 17 [cited 2022 Apr 17];386(7):640–54. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2116133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamdar M, Solomon SR, Arnason JE, Johnston PB, Glass B, Bachanova V, et al. Lisocabtagene Maraleucel (liso-cel), a CD19-Directed Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cell Therapy, Versus Standard of Care (SOC) with Salvage Chemotherapy (CT) Followed By Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation (ASCT) As Second-Line (2L) Treatment in Patients (Pts) with Relapsed or Refractory (R/R) Large B-Cell Lymphoma (LBCL): Results from the Randomized Phase 3 Transform Study. Blood [Internet]. 2021. Nov 23 [cited 2022 Apr 17];138(Supplement 1):91–91. Available from: https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/138/Supplement1/91/477568/Lisocabtagene-Maraleucel-liso-cel-a-CD19-Directed33881503 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westin J, Sehn LH. CAR T cells as a second-line therapy for large B-cell lymphoma: a paradigm shift? Blood [Internet]. 2022. May 5 [cited 2022 May 31];139(18):2737–46. Available from: https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/139/18/2737/484263/CAR-T-cells-as-a-second-line-therapy-for-large-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. B-Cell Lymphomas Version 3.2022 [Internet]. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2022. [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/b-cell_blocks.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nowakowski GS, Yoon DH, Mondello P, Joffe E, Fleury I, Peters A, et al. Tafasitamab Plus Lenalidomide Versus Pola-BR, R2, and CAR T: Comparing Outcomes from RE-MIND2, an Observational, Retrospective Cohort Study in Relapsed/Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Blood [Internet]. 2021. Nov 23 [cited 2022 Jun 4];138(Supplement 1):183–183. Available from: https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/138/Supplement1/183/481261/Tafasitamab-Plus-Lenalidomide-Versus-Pola-BR-R2 [Google Scholar]