Abstract

The apicoplast, a relict plastid found in most species of the phylum Apicomplexa, harbors the ferredoxin redox system which supplies electrons to enzymes of various metabolic pathways in this organelle. Recent reports in Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium falciparum have shown that the iron-sulfur cluster (FeS)-containing ferredoxin is essential in tachyzoite and blood-stage parasites, respectively. Here we review ferredoxin’s crucial contribution to isoprenoid and lipoate biosynthesis as well as tRNA modification in the apicoplast, highlighting similarities and differences between the two species. We also discuss ferredoxin’s potential role in the initial reductive steps required for FeS synthesis as well as recent evidence that offers an explanation for how NADPH required by the redox system might be generated in Plasmodium spp.

Keywords: ferredoxin, Apicomplexa, malaria, toxoplasmosis, isoprenoids, redox system

Elusiveness of the apicoplast

The phylum Apicomplexa consist of more than 5,000 species of unicellular, obligate intracellular organisms, including the human malaria-causing Plasmodium falciparum, and Toxoplasma gondii, the causative agent of toxoplasmosis in humans and animals. Besides being pathogens with large impacts on human and livestock health, both species have also become prime model organisms to study their biochemical adaptations to their respective hosts [1, 2]. Experimental studies are facilitated by a large molecular toolbox which allows the genetic manipulation of both parasites, albeit with varying efficiencies and ease in generating such mutants and with somewhat more advanced techniques available for T. gondii. Together with the different host cell specificities and economics of cultivation, both models have thus distinct advantages and disadvantages. It is therefore beneficial to use complementary approaches in the two organisms to study common biological aspects, compare the outcomes and exploit potential vulnerabilities as potential drug targets.

Apart from shared structural features such as the presence of invasion related organelles, most organisms within this phylum harbor a four-membrane bound plastid-derived organelle called “apicoplast”. Exceptions are Cryptosporidium spp. and several gregarines due to secondary loss of the organelle [3]. Its presence and its elusive function raised special interest right from the beginning of its description.

The apicoplast and ferredoxin - a link to the ‘dark metabolism’ of plant plastids

Almost six decades ago, electron microscopical studies on several apicomplexans revealed a single organelle surrounded by multiple membranes that was given different names depending on the organism under study [4]. It was later called “apicoplast” (apicomplexan plastid) and shown to be composed of four membranes based on ultrastructural studies of T. gondii [5], later also confirmed for P. falciparum [6]. It harbors a 35-kb circular DNA, and its nucleotide sequence revealed its similarity to plastid genomes of red algae, except that the apicoplast lacks photosynthesis-related genes [7]. It is thought to be a product of secondary endosymbiosis (see Glossary) between an apicomplexan ancestor and a red algal endosymbiont [8–10]. Through endosymbiotic gene transfer to the nucleus the gene content of the apicoplast genome became highly reduced, leaving only limited traces in the form of SufB (see Box 1) of its present metabolic capabilities. Hundreds of nuclear-encoded proteins are transported to the apicoplast via topogenic N-terminal bi-partite targeting sequences, and together with genomic data analysis and transcriptomics, initially in P. falciparum, they allowed the construction of a core map of apicoplast metabolism [11]. It fast raised the hope for selective inhibitors of plant-derived pathways with minimal side effects in humans, exemplified by the description of the antibiotic fosmidomycin (Fos) as an inhibitor of an enzyme of the apicoplast-resident isoprenoid pathway (Figure 1, Key Figure) and which impairs the growth of Plasmodium spp. in vitro and in vivo [12].

Box 1. Iron-sulfur clusters and the general concept of their biogenesis.

Iron-sulfur cluster (FeS) cofactors are one of the most ubiquitous protein cofactors and are found in organisms from every kingdom. They can help to stabilize proteins as well as having roles in electron transfer, sulfur donation reactions, and oxygen sensing [66, 86, 87]. Proteins can contain single or multiple FeS, with the most common forms being rhombic 2Fe-2S and cubic 4Fe-4S. When bound to proteins, they show typical absorbance peaks characteristic for the type of cluster in the respective context (for examples see [74]).

The general mechanism of FeS formation in the mitochondrion and apicoplast involves pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent cysteine desulfurases which liberate sulfur (S0) from cysteine and transfer it to relay proteins in the form of a persulfide. The sulfur is then transferred to a scaffold protein (or proteins), where the FeS is formed with iron. Subsequently, the clusters are transferred to apoproteins via carrier proteins. Mitochondrial proteins rely on the mitochondrial ISC (iron-sulfur cluster formation) pathway and proteins in the cytosol and nucleus rely on the CIA (cytosolic iron-sulfur protein assembly) pathway (reviewed in [87]). In the ISC system, the role of 2Fe-2S-cluster containing mtFd and its cognate partner mtFNR in reducing the S0 to S2- by providing electrons to the cysteine desulfurase or to the FeS scaffold proteins is well documented [74, 88]. By contrast, in the plastid-localized SUF pathway (sulfur utilization factor) the electron source has not been defined. In apicomplexan parasites, this could be the ptFd/ptFNR system. Strikingly, two recent reports stated that non-photosynthetic plastids of two protists have lost all FeS-requiring enzymes and connected pathways, like the SUF system or MEP, and also show no signs of Fd in their genomes or transcriptomes [89, 90]. If confirmed, it could provide an argument for the ptFd redox system being this source.

From early on, one of the few proteins encoded on the apicoplast genome was recognized as SufB of the SUF system. It suggested the apicoplast to be a place of FeS synthesis, the only trace of a metabolic pathway encoded on its genome [67, 68]. SufB was proposed to be essential, and therefore loss of the plastid’s genome would be lethal for the parasite, providing an argument for its retention.

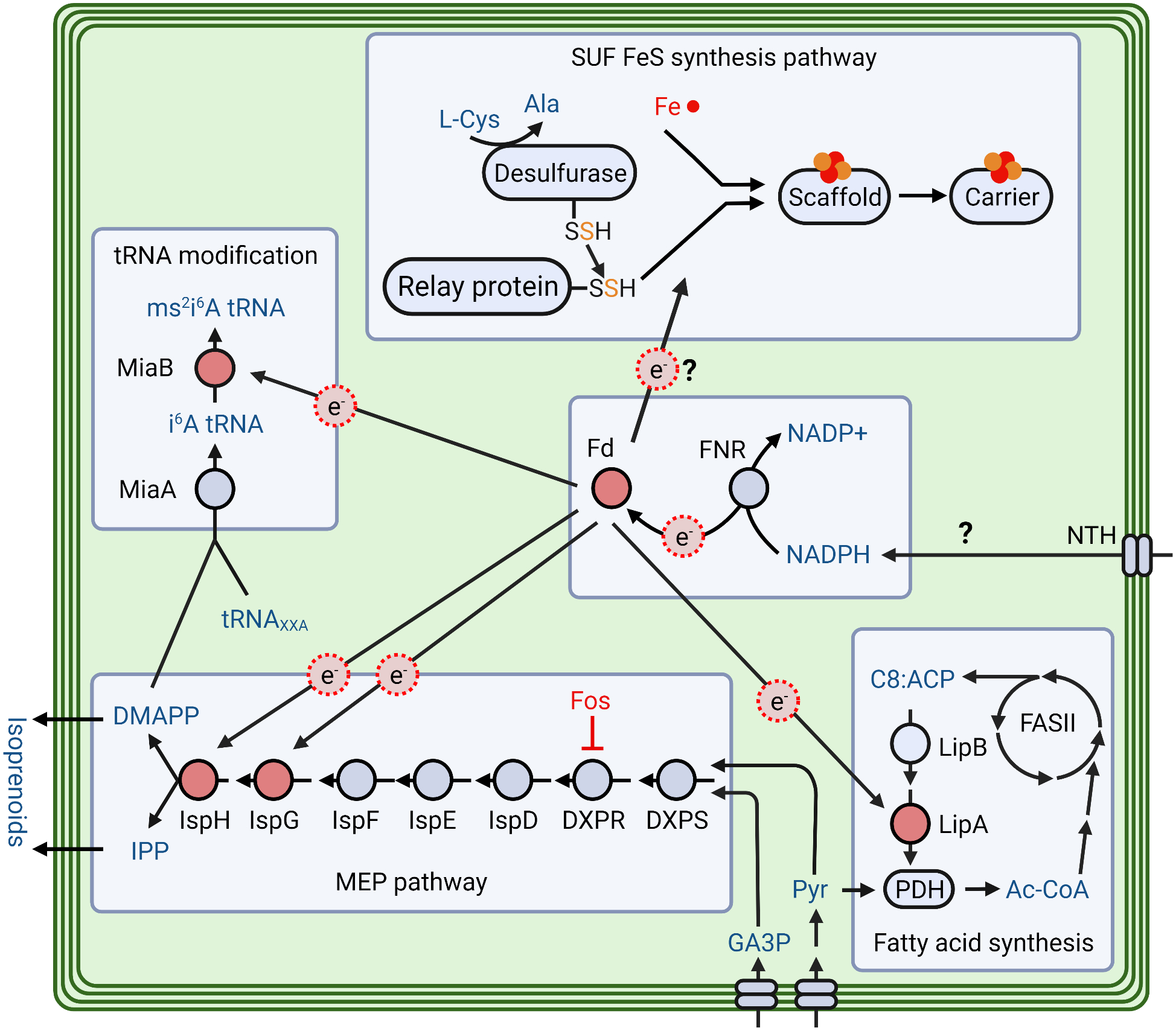

Figure 1, Key Figure. A schematic overview of various ferredoxin (ptFd) and ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase (ptFNR)-dependent metabolic pathways in the apicoplast.

ptFd reduction is catalyzed by NADPH-dependent enzyme ptFNR and could donate electrons (e−) to four other FeS- proteins, and probably to early steps of FeS synthesis itself. The NADP transhydrogenase (NTH) is suggested to provide NADPH for ptFd reduction by ptFNR. The SUF FeS synthesis pathway uses a cysteine desulfurase to mobilize sulfur from the available cysteine pool and transfer it to the scaffold protein complex with the aid of a relay protein. FeS cofactors formed on the scaffold complex are transferred to target proteins (light red) by the carrier proteins. Two proteins, IspG and IspH, that receive electrons from ptFd are the last two enzymes of the essential MEP pathway. The glycolytic metabolites pyruvate (Pyr) and glyceraldehyde-3 phosphate (GA3P) are substrates for the MEP pathway and thought to be imported by apicoplast transporters. In seven subsequent enzymatic reactions the substrates are converted into IPP and DMAPP. DXPR is the target of Fosmidomycin (Fos). Other ptFd/FNR-dependent proteins are LipA (lipoate synthase) of the lipoate synthesis pathway and MiaB (tRNA-i6A37 methylthiotransferase) responsible for ms2i6A (2-methylthiol-N6-isopentenyl adenosine) tRNA modification. DOXP, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate; DXPR, DOXP-reductoisomerase; IspD, 2C-Methyl-D-erythritol 4-Phosphate Cytidyltransferase; IspE, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase; IspF, 2C-methyl-D-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase; IspG, hydroxylmethylbutenyl diphosphate (HMBPP) synthase; IspH, HMBPP reductase; DMAPP, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate; IPP, isopentenyl pyrophosphate; Cys, cysteine; Ala, alanine; Fe, iron; i6A, N6-isopentenyl adenosine; MiaA, tRNA isopentenyltransferase; ms2i6A, 2-methylthiol-N6-isopentenyl adenosine; C8:ACP, octanoyl acyl carrier protein; FASII, type II fatty acid synthesis pathway; LipB, lipoate (octanoyl)transferase; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; Ac-CoA, acetyl CoA. Figure created with BioRender.com.

When more than two decades ago one of the authors searched a list with sequenced top hits of a T. gondii EST cDNA library for potential apicoplast-resident proteins, a single high confidence annotation was “ferredoxin--NADP+ reductase”, a protein known from photosynthesis. Consulting a plant metabolism textbook provided a hint to what ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase (FNR) and its redox partner, the small acidic and iron-sulfur cluster (FeS)-containing protein ferredoxin (Fd) might do in an obviously non-photosynthetic organism [13]. Both proteins are not only involved as essential electron receivers and transmitters in photosystem I (PSI), thereby producing NADPH used in the Calvin cycle for CO2 fixation, but also in the ‘dark side’ of the plastid’s metabolism, i.e. in roots and other non-green tissue (reviewed in [14]). Here, chemical equation (1) works in the opposite direction, thereby transferring electrons to enzymes of several metabolic pathways from NADPH via FNR to Fd:

| (1) |

Plant plastids contain a variety of Fd-dependent enzymes [15] and several of these are present in apicomplexan parasites. Numerous bioinformatic, genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic analyses have established the roles of Fd-dependent enzymes in isoprenoid biosynthesis, fatty acid biosynthesis, tRNA modification and possibly synthesis of FeS clusters [11, 16, 17]. These processes and the central role Fd plays in them are detailed below and summarized in Figure 1.

Biochemical features of ptFd and ptFNR

Ferredoxins are long known as prime electron transfer proteins for a wide range of biochemical redox reactions and can be found in all domains of life [18]. Originally evolved from Fds containing 4Fe-4S clusters (Box 1) in a largely anaerobic world, the less O2-sensitive, small (<200 aa) 2Fe-2S Fds are more abundantly found in aerobic eukaryotes. In addition, lateral gene transfer played an important role in their evolution [18, 19]. In most of these organisms they are either located in mitochondrion-like organelles and are called adrenodoxin- or bacteria- or mitochondrion-type Fd (mtFd), or they are found in plastid-derived organelles, defined as plant-type Fd (ptFd), respectively (Box 2). Strong sequence homology does not necessarily allow precise functional categorization, since similar Fd proteins can differ significantly in reduction potential and/or specificity for their Fd-interacting protein partners [20]. This situation is even more perplexing since flavodoxins, unrelated by sequence and absent in Apicomplexa, can substitute Fds in many organisms (Box 2). Consequently, experimental evidence for their presumed function is usually critical in order to make firm conclusions.

Box 2. Differences and commonalities between adrenodoxin, ferredoxin, and flavodoxin.

Eukaryotes with two metabolically active organelles, i.e. mitochondria and plastids or derivatives thereof, usually also harbor distinctly different 2Fe-2S Fd’s with low sequence homology, adrenodoxin or mtFd, and ptFd, respectively. While these two groups of 2Fe-2S Fds can in some reactions also work interchangeably at least in vitro, mtFd’s main function is considered to be its crucial involvement in the redox chemistry of FeS assembly in mitochondria. Here it is required for both, initial 2Fe-2S synthesis and their subsequent conversion to 4Fe-4S clusters by reductive fusion [74]. Conceptually, a similar task of ptFd would be required in plastid-derived organelles as well, but this has not been addressed so far.

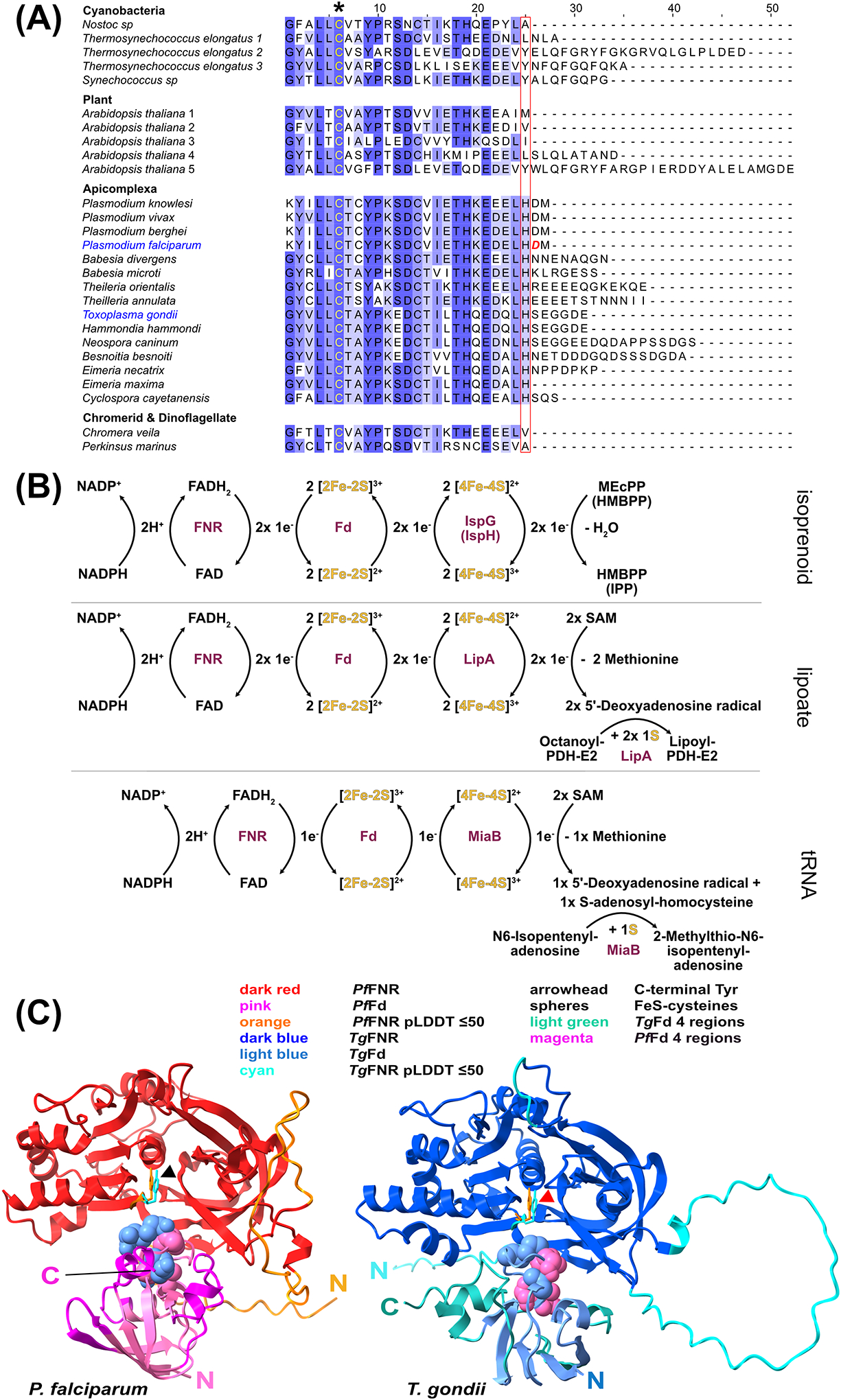

As a typical ptFd, apicomplexan ptFds have a higher redox potential than the Fd isotype present in plant leaves [21]. The overall sequence structure is similar to that of other ptFds, except that the C-terminal region is significantly different, even between TgFd and PfFd (Figure 2A and supplementary Figure S1), with potential functional consequences. For example, a D97Y mutation increases the affinity of PfFd for PfFNR to some extent [22, 23]. A previous genome-wide association study had implicated PfFd to be potentially involved in artemisinin resistance [24] due to the D97Y mutation. However, generating transgenic parasites with this mutation has recently been shown to have no impact on artemisinin resistance in vivo [25].

Figure 2. Biochemical features of Tg/PfFd-FNR and their central role in some apicoplast biosynthetic pathways.

(A) Sequence alignment of the 25 C-terminal amino acids of 27 select ptFds to illustrate the C-terminal differences, in particular within Apicomplexa. * indicates one of the four FeS-coordinating cysteines. The boxed amino acids denote the C-terminal end of the majority of ptFds (not shown). For the entire alignment see supplementary Figure S1. (B) Scheme showing how electrons transferred from NADPH are used to reduce ptFd through ptFNR and its subsequent transfer from ptFdred to enzymes involved in isoprenoid and lipoate biosynthesis as well as tRNA modification of N6-isopentenyladenosine to give 2-methylthio-N6-isopentenyladenosine (ms2i6A). In the two S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-requiring reactions, reductive cleavage of SAM by FeS cofactors generates adenosyl radical capable of hydrogen atom extraction from the substrates (octanoylated PDH-E2 for LipA and N6-isopentenyladenosine for MiaB). The resulting substrate radicals are then thiolated with sulfur from the LipA and MiaB FeS cofactors [102]. (C) Model of ptFd/FNR complex from T. gondii (blue-ish colors; right) and P. falciparum (red-ish colors; left), generated with the ColabFold/AlphaFold2 algorithm [103]. For details see legend. Structures annotated as “pLDDT ≤50” are of low structural confidence. N- and C-termini are indicated. For ptFNR, the C-terminal ends are the two tyrosines in the enzyme’s active center (red arrow). Note the overall high structural similarity between the two redox systems but also the somewhat different position of the FeS-coordinating cysteines in both Fd’s in relation to the C-terminal tyrosines. An overlay of both structures is provided in supplementary Figure S2B, and for an animated 3D structure of it see supplementary Movie S1.

The other component of the redox system is the FAD cofactor-containing FNR which functions as an NADPH-dependent oxidoreductase, utilizing its electrons to reduce Fd [26] (Figure 2B). This is consistent with the phylogenetically closer relationship of TgFNR to non-photosynthetic FNRs from roots than to isoforms of cyanobacterial or chloroplast origin [13]. Within the FAD-binding domain of all apicomplexan FNRs, there is a peptide insertion of variable length and sequence that extends the short loop present in other FNRs and connects this N-terminal domain with the NADPH-binding C-terminal domain [27] (Figure 2C, supplementary Figure S2B and Movie S1). Its function, if any, is not known. In contrast to TgFNR, the 3D structure of PfFNR has been experimentally determined, confirming the two-domain structure known from the plant enzymes [28]. Three chemically reactive residues are relevant for its activity: C99, C284, and H286. They are involved in hydride transfer, maintenance of activity, and NADPH binding, respectively.

Given the importance of ptFd and ptFNR in photosynthesis and chloroplast metabolism, a large body of structural knowledge exists with regard to enzymatically important residues and also amino acids involved in protein-protein interactions (PPI) between both proteins (for review see [27]). In general, these residues are highly conserved in ptFNRs from other species, including Apicomplexa. Despite ptFd being a small protein (around 100 aa without the organellar trafficking sequence), its flexibility to interact specifically with a number of different electron acceptor proteins is remarkable. This is thought to be due to several variable segments along the sequence providing some structural flexibility, allowing different small regions to engage in different PPIs [29] (Figure 2A, B). Most of the interactions are electrostatic due to the negative surface charge distribution around the 2Fe-2S cluster of ptFd, contrasting with e.g. the basic amino acids dominating the hollow surface of the FAD-binding domain of ptFNR [27]. This brings the two prosthetic groups at a distance suitable for electron transfer (one at a time; Figure 2B). The C-terminal tyrosine, highly conserved in all ptFNRs, plays a crucial role in this interaction (Figure 2C). Electrostatic interactions have also been suggested for the modeled structures of PfFd/FNR and TgFd/FNR [30, 31] as well as PfFd/IspH [32].

Isoprenoid biosynthesis and ptFd’s role as electron donor for IspG and IspH

Isoprenoids are diverse metabolites required by all apicomplexan parasites for processes including post-translational modification (prenylation), glycosylation, tRNA modification, and cofactor synthesis (heme A, ubiquinone) [33]. Most apicomplexans synthesize the five-carbon isoprenoid precursors isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) using an apicoplast-localized methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway. It is thought to be essential for all Apicomplexa (for review see [17, 33, 34]), with the notable exception of apicoplast-deficient species since they rely on isoprenoid scavenging from their hosts. The MEP pathway is present in a majority of the eubacteria and plastid-bearing eukaryotes, whereas most eukaryotes, including mammals and land plants (in addition to plastidial MEP), contain a cytosolic mevalonate (MVA) pathway [33]. The two pathways differ significantly from each other (Box 3).

Unlike cyanobacteria and algae, which possess both, ptFd and the flavin mononucleotide (FMN)-containing flavodoxin (Fld) as interchangeable redox proteins, plants and Apicomplexa lack the latter. The accepted view is that Fld is not oxygen-sensitive and also works under iron-deplete conditions whereas the opposite is true for ptFd. Therefore, it is advantageous for organisms living in environments with highly fluctuating iron supply (e.g. marine plankton) to have both proteins [91]. Not surprisingly, the Chromerida, thought to be the closest free-living phototrophic marine alga from which Apicomplexa evolved, possess genes for both proteins [92]. By contrast, in Apicomplexa iron supply from the host cell might not fluctuate dramaticallyand oxygen stress in the apicoplast is fairly low, explaining why Fld could have been lost while maintaining ptFd. Structurally, ptFd and Fld are very distinct but still can interact with the same electron acceptor protein, e.g. ptFNR or proteins from PSI [93]. Whether this flexibility in PPI of Fld with apicomplexan proteins is still preserved is currently unknown.

Box 3. Differences between MVA and MEP pathway

Isoprenoid biosynthesis in plants rests on two branches, the MEP pathway in the plastid and a cytosolic pathway called mevalonate (MVA) pathway, which is exclusively used by all other eukaryotes (and some gram-positive bacteria). The MVA pathway starts with different initial metabolites (two molecules of acetyl-CoA vs pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate for MEP) and uses different enzymes (six for MVA vs seven for the MEP pathway) with very different chemistries. The MEP pathway produces IPP and DMAPP while the MVA pathway produces exclusively IPP and requires an isomerase to generate DMAPP. This example of convergent evolution results in the situation that the eukaryotic hosts of Apicomplexa, despite relying on the same isoprenoid metabolites, are not vulnerable to drugs targeting the MEP enzymes (e.g. Fos). Vice versa, in the case of T. gondii, inhibitors of the MVA pathway, such as the family of statins (known as cholesterol-lowering drugs for human use), are helpful experimental tools to distinguish host from parasite isoprenoid synthesis since T. gondii is able to scavenge IPP from the host [40, 41]. This is in contrast to the blood stages of P. falciparum since activities of MVA pathway enzymes and their metabolite concentrations in red blood cells are very low [94, 95] and the reported inhibitory activity of atorvastatin on P. falciparum at high micromolar concentrations is presumably due to its inhibition of the parasite’s lactate dehydrogenase [96] rather than an indication of a block in IPP scavenging from erythrocytes. However, the apparent dispensability of PbDXPR in liver stages [54], if confirmed, could hint to a similar situation as in T. gondii, i.e. scavenging of isoprenoids from the host cell. Consequently, the two host systems have very different capabilities with regard to metabolism of isoprenoids, and their contribution to such a scavenging scenario are also quite different.

The MEP pathway uses two glycolytic intermediates, pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, as substrates. In seven subsequent reactions these are converted into IPP and DMAPP (Figure 1). Most of the apicomplexans, including P. falciparum and T. gondii, harbor all seven nuclear-encoded MEP pathway enzymes (Table 1). In both species isoprenoid precursor synthesis is essential, initially demonstrated by drug inhibition (Fos) [12] and later by deletion of its target gene, PfDXPR [35]. Similarly, conditional knockdown of the genes encoding TgDXPR and TgIspH prevents growth of tachyzoites [36].

Table 1.

Ortholog group of some enzymes involved in apicoplast metabolism

| Abbreviation | Protein name | Pathway | Ortholog group* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fd | Ferredoxin | several | OG6_106507 |

| FNR | Ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase | several | OG6_107528 |

| DXPS | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase | MEP | OG6_104068 |

| DXPR | D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase | MEP | OG6_105665 |

| IspD | 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase | MEP | OG6_103820 |

| IspE | 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase | MEP | OG6_492256 |

| IspF | 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase | MEP | OG6_105913 |

| IspG | 4-hydroxy--3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl diphosphate synthase | MEP | OG6_105784 |

| IspH | 1-deoxy 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase | MEP | OG6_105777 |

| LipA | Lipoate synthase | FASII | OG6_100980 |

| LipB | Lipoate (octanoyl)transferase | FASII | OG6_101396 |

| MiaA | tRNA isopentenyltransferase | tRNA mod. | OG6_100923 |

| MiaB | tRNA-2-methylthio-N6-dimethylallyladenosine synthase | tRNA mod. | OG6_101475 |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | NADH generation | OG6_100218 |

| NTH | NAD(P)+ transhydrogenase | transport | OG6_101345 |

access at https://orthomcl.org/

Both, PfIspG and PfIspH, contain 4Fe-4S clusters [32, 37], and the reactions catalyzed by the two enzymes require two electrons at each step (Figure 2B). Accordingly, NADPH oxidation could be observed when recombinant PfIspH was combined with PfFd and PfFNR in presence of hydroxylmethylbutenyl diphosphate (HMBPP) [38]. The suggested electron flow from NADPH to PfIspH via ptFd/FNR was corroborated by PfFd’s physical interaction with PfIspH in vitro.

More recent experiments confirmed the essential role of ptFd in the MEP pathway. Using the P. falciparum mevalonate bypass parasite line, PfMev [35] (Box 4), Swift et al. were able to generate individual knockouts of both, PfIspG and PfIspH [39]. Both lines were dependent on mevalonate supplementation for growth, demonstrating that both enzymes are essential for parasite survival in the infected red blood cells (iRBC). The same mevalonate dependence was observed for knockouts of PfFd and PfFNR, consistent with the reliance of PfIspG and PfIspH on the ptFd/FNR system [39].

Box 4. IPP’s non-permeability for membranes and its experimental consequences.

IPP is able to compensate for the inhibition of the MEP pathway in P. falciparum by e.g. Fos [97]. This is attributed to the fact that IPP and Fos can enter infected red blood cells (iRBC) but not uninfected ones due to a change in membrane permeability for various substrates upon P. falciparum infection [98]. This is in stark contrast to T. gondii, which is not affected by Fos at pharmacological concentrations due to the inability of the highly charged Fos (and likewise IPP) to cross biological membranes by passive diffusion [36, 98]. The resulting experimental consequences are profound since it provides an easy (though expensive) way in P. falciparum to compensate for knock-outs of essential individual apicoplast functions by adding 200 μM IPP to the culture medium. Such compensation in T. gondii is currently not possible or requires the time-consuming generation of an inducible knock-out of the gene-of-interest. A solution is the exploration of a “mevalonate bypass system” similar to what has been described in bacteria and recently also in P. falciparum [35]. It relies on the transgenic expression of the last three enzymes of the MVA pathway which convert mevalonate added to the growth medium to IPP; a fourth enzyme isomerizes IPP to also provide DMAPP. How efficient mevalonate uptake by nucleated cells occurs is unknown but requires attention since it is only a poor substrate for its possible transporter MCT1 [99]. Nevertheless, a mevalonate bypass system for T. gondii would greatly expand the experimental possibilities and allow direct comparisons of apicoplast’s function in the different host-parasite stages as well as comprehensive metabolic analyses due to the commercial availability of 13C-mevalonate [35].

The products of the MEP pathway are required also outside of the apicoplast and need to be delivered e.g. to the mitochondrion but its mechanism is currently ill defined [16]. In plants, IPP and MEcPP export out of the plastid is known to occur. In Escherichia coli and human γδ T cells the large group of ABC-type transporters has been implicated in the export of IPP or its precursors out of the cell [100, 101]. Such an export mechanism seems necessary, at least in E. coli, to adjust the levels of the precursors of the MEP pathway due to their individual cellular toxicity upon overproduction and a lack of their catabolic consumption. Whether this type of regulation by transporters is also operating in Apicomplexa is currently unknown.

Direct biochemical evidence for ptFd’s role was recently obtained with an inducible genetic knockdown in T. gondii. Henkel et al. observed a dramatic reduction in cellular levels of HMBPP (product of IspG reduction) and IPP/DMAPP (product of IspH reduction) (Figure 2B) in tachyzoites [40]. Notably, a significant influence of host isoprenoid synthesis could be observed, evident by tachyzoite’s faster death upon treatment with the MVA pathway inhibitor atorvastatin. Similar results were reported for a farnesyl diphosphate synthase knockout [41]. This isoprenoid scavenging by tachyzoites from the host cell is, however, not observable in iRBC (Box 3). Collectively, these results strongly support a model in which the synthesis of essential isoprenoid precursors depends on the ptFd/FNR system in the apicoplast (Figure 1) but with differences between both species with regard to metabolite scavenging.

Lipoate and fatty acid biosynthesis - radical SAM-dependent enzymes also rely on ptFd

Besides three mitochondrial protein complexes (the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase and the glycine cleavage complex), the apicoplast-localized pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) requires the cofactor lipoate for activity [42–46]. PDH catalyzes the decarboxylation of pyruvate into acetyl-CoA for fatty acid synthesis (FAS) by the bacterial-type FASII pathway [47, 48]. This complex consists of E1, E2, and E3 enzyme subunits, with lipoate covalently bound to E2. Strikingly, lipoate is synthesized de novo on E2 by two enzymes, lipoate synthase (LipA) and lipoate (octanoyl)transferase (LipB) (Table 1). FASII produces acyl carrier protein-bound octanoic acid (C8:ACP in Figure 1) as one of its intermediates. LipB then transfers the octanoyl moiety from C8:ACP to PDH-E2. LipA catalyzes the insertion of two sulfur atoms at positions C6 and C8 into the octanoyl moiety of the E2 subunit in a radical S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)-dependent manner (Figure 2B), thus generating the dithiolane ring of lipoate [49]. Active, lipoylated E2 then shuttles reaction intermediates within the other subunits of the PDH complex. Several studies have provided strong evidence that apicoplast-resident LipA and LipB are functional enzymes and that PDH-E2 is the sole lipoylated protein in this organelle [43–46, 50, 51].

PfLipA is a 4Fe-4S cluster enzyme [52] and thought to receive electrons from the ptFd/FNR system. Two-hybrid systems were used to demonstrate that TgLipA is engaged in PPI with both PfFd and TgFd, suggesting electron flow from NADPH via ptFd/FNR to TgLipA [50] (Figure 2B). Despite earlier claims, recently reported genetic deletion of PfLipA in blood-stage P. falciparum resulted in no detectable growth phenotype, which contrasts with the essential phenotype of PfFd knockout [39]. Given the dispensability of PfLipB, the PDH subunits, and multiple FASII enzymes in blood-stage P. falciparum (reviewed in [53]), it was not surprising that PfLipA was also dispensable for parasite growth. The importance of PfLipA in other stages of the P. falciparum life cycle has not been addressed. However, given the essentiality of the FASII pathway in the mosquito- and liver-stages [53], PfLipA is likely to be required for parasite development in those stages. Consistent with this, LipA knockout in P. berghei showed significantly slowed-down parasite maturation in liver-stages, demonstrating essentiality of PbLipA for growth [54]. Furthermore, as recently reported, PfLipB knockout parasites produce morphologically conspicuous oocysts in the mosquito midgut, which eventually result in no salivary gland sporozoites [55], suggesting a crucial role of PbLipB in sporogony. Collectively, these studies demonstrate the essentiality of lipoate biosynthesis in mosquito- and liver-stages of the parasite and are in agreement with PfFd’s crucial role in it.

Both, TgLipA and TgLipB, might be essential in tachyzoites, based on their relatively weak negative phenotypic score (TgLipA: −0.97, TgLipB: −1.74) from a genome-wide CRISPR screen [56]. However, this result could be influenced by several factors (e.g. duration of observation of parasite culture; medium composition etc.), and no targeted genetic deletion of these enzymes has been reported. A significant reduction in the level of medium-chain FAs compared to wild-type T. gondii cells was recently reported in knockout strains of TgFabD or TgFabZ, crucial FASII enzymes [57, 58]. A similar observation in FA reduction was made when TgFd was conditionally knocked-down [40]. However, as long as a sufficient external FA supply is provided, a functional FASII pathway is not essential for optimal growth of tachyzoites, as shown by the former two studies. Since TgFd depletion also affects IPP synthesis, firm conclusions about TgLipA’s essentiality cannot be drawn from these studies and require further attention.

MiaB and tRNA modification, another SAM- and ptFd-dependent reaction

The 2-methylthio-N6-isopentenyladenosine (ms2i6A) modification occurs at position 37 (A37) in transfer RNAs (tRNAs) that have adenine in position 36 of the anticodon. This modification has been identified in tRNAs from bacteria, plants and several mammals and is thought to play an important role in codon recognition by stabilizing tRNA interactions with cognate codons, thus preventing premature stops and frame-shift errors during translation [59, 60]. In E. coli, two enzymes act sequentially to produce the ms2i6A modification [61], MiaA, and the 4Fe-4S containing protein MiaB, the presumed acceptor of electrons coming from Fd (see Figure 2B for details). In Apicomplexa, orthologues of both MiaA and MiaB have been identified (Table 1) and are assumed to be apicoplast-resident [11]. Putative genes with internal stop codons and/or frame-shifts were described in the apicoplast genomes of both P. falciparum and T. gondii [5, 7]. Thus, the ms2i6A tRNA modification is thought to be essential for translational fidelity of these sequences. Recently, MiaB of the bacterium Thermotoga maritima (Tm) has been shown to interact with bacterial-type TmFd and receive electrons from NADPH via TmFNR, resulting in improved production of ms2i6A [62]. This supports the earlier prediction that PfMiaB and TgMiaB will receive electrons via ptFd/FNR [11, 63]. However, neither deletion of PfMiaA [64] nor PfMiaB [39] resulted in any growth defect. This observation shows that ms2i6A modification is not required for parasite replication in RBCs and suggests that the PfMiaA/B enzymes are not necessary for expression of essential apicoplast genes. In T. gondii, TgMiaA and TgMiaB have not been targeted for deletion or knockdown. However, based on their weak negative phenotype score (TgMiaA: −0.48, TgMiaB: −0.18) they wouldn’t be regarded as essential, at least in tachyzoites [56]. Taken together, the role of tRNA modification in the apicoplast and ptFd’s role in it is still ill-defined. In bacteria, the ms2i6A tRNA modification catalyzed by MiaB seems to have a regulatory role in the induction of genes involved in iron accumulation [60]. Whether MiaA/MiaB might have a similar role in other developmental stages or under particular in vivo conditions where the parasites are not under iron-rich conditions (unlike e.g. in the blood stage of P. falciparum) needs to be examined.

FeS biosynthesis and ptFd’s role - only a beneficiary or also an essential player?

Being an FeS protein itself, it is important to have a closer look at ptFd’s potential role in the biogenesis pathway of FeS clusters. Both the 2Fe-2S and 4Fe-4S cofactors are synthesized in the apicoplast by enzymes of the SUF (sulfur utilization factor) pathway (Table 1) [65, 66], while proteins in other compartments follow different routes (Box 1). From early on, one of the few proteins encoded on the apicoplast genome, SufB of the SUF system, was proposed to be essential [67, 68]. and therefore loss of the plastid’s genome would be lethal for the parasite.

Recent studies confirmed the SUF pathway’s indispensability for T. gondii and for malaria parasites. It starts with the cysteine desulfurase SufS, which mobilizes sulfur from L-cysteine, resulting in a SufS-bound persulfide. Sulfur harvested by SufS is then transferred to the FeS scaffold complex (SufBC2D) by sulfur transferase SufE. In vitro studies have shown complex formation by PfSufB, PfSufC, and PfSufD [69, 70] and demonstrated the interaction between PfSufE and PfSufS [71]. Deletion of SufS in T. gondii leads to loss of the apicoplast organelle and parasite death [65]. Similarly, SufS was shown to be essential for blood- and mosquito-stage malaria parasites [69, 72]. Failed attempts to delete PbSufE or scaffold proteins PbSufC and PbSufD in blood-stage P. berghei suggest their importance for the sulfur transfer step and the FeS-scaffold complex [72]. Similarly, targeting SufC in P. falciparum [52] and T. gondii [73] resulted in loss of parasite viability, and in the latter, depletion of TgSufC or TgSufS decreased FA synthesis and showed membrane perturbations also outside of the apicoplast, which hints to reduced isoprenoid synthesis. These phenotypes are consistent with a loss of activity of any of the four essential FeS proteins due to impaired FeS clusters [73].

Interestingly, it appears that the FeS carrier proteins (SufA or NfuApi) responsible for the delivery of clusters formed by the SufBC2D complex are individually dispensable in P. falciparum but display synthetic lethality when both are deleted [39, 72]. This result suggests that PfSufA and PfNfuApi are both capable of transferring 2Fe-2S or 4Fe-4S clusters since clusters of both types are needed for essential apicoplast FeS proteins (i.e. ptFd and IspG/IspH). This is consistent with the finding that the double deletion of PfSufA and PfNfuApi in P. falciparum could be rescued using the mevalonate bypass system [39].

Collectively, all these data support a model in which the SUF pathway is required for the activity of ptFd (and other FeS proteins). Since electrons are required to reduce sulfur (S0) to the S2- form, ptFd, in turn, might be involved in its own activity, leading to a chicken-and-egg situation. In eukaryotic mitochondrial ISC systems, electrons are provided by the mtFd/FNR system (Box 1), but it is unclear how this process occurs in bacterial and eukaryotic SUF pathways. Notably, electron transfer from NADPH via mtFd/mtFNR is essential for reductive fusion of 2Fe-2S2+ to 4Fe-4S2+ clusters assembled on the mitochondrial FeS scaffold proteins [74]. Since all known FeS proteins in the apicoplast contain 4Fe-4S clusters, except ptFd, it provides a strong argument for the ptFd/FNR system being the best candidate for providing electrons to the SUF pathway in the apicoplast. However, experimental verification of this hypothesis is urgently required.

In search for the source of NADPH in the apicoplast

The source of NADPH in the apicoplast required by ptFNR (and also by DXPR and FabG) is of critical importance. Since in the absence of photosynthesis two general sources for NADPH generation, PSI and the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway, are lacking, alternative ways to reduce NADP+ are needed. One possibility that had been proposed in P. falciparum and T. gondii is connected to the triose phosphate/3-phosphoglycerate shuttle [75, 76]. It would convert triose phosphate isomerase (TPI)-generated glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate into 1,3-diphosphoglycerate by glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), thereby generating NADPH. However, several reasons argue against this possibility in P. falciparum. GAPDH is not apicoplast-localized [77, 78] and it is enzymatically active only with NAD+ as substrate but not with NADP+ [79]. Moreover, TPI deletion is without consequences on IPP synthesis in iRBC, implying that this path of NADPH supply is not operating in Plasmodium spp. [80]. This might be different in other Apicomplexa, which contain a second GAPDH isoform presumably present in the apicoplast [81] (Table 1). However, its substrate specificity has not been experimentally verified in any case.

It had also been speculated that NADPH could be replaced by NADH, derived from the PDH complex [76] but this seems unlikely. TgFNR and to a lesser extent PfFNR are very specific for NADPH [26, 82], thereby ruling out NADH as a valid substrate for ptFNR. Moreover, as noted before, the PDH complex is not strictly essential in T. gondii and not at all in blood-stage P. falciparum.

A possible, though puzzling solution emerged recently by the description of a single gene encoding an NAD(P)+ transhydrogenase (NTH) in P. berghei [83]. NTH is usually a mitochondrial transmembrane proton-translocating protein in other organisms [84], thereby enabling the generation of NADPH according to chemical equation 2:

| (2) |

By contrast, PbNTH was described to be apicoplast-localized in sporozoites, and in oocysts in structures called crystalloids. While it is tempting to assume that in equation (2) “out“ could be cytosol and “in“ the apicoplast lumen, non-functional PbNTH did not prevent the sporozoite-to-blood stage transition (although it had some effect) [83], leaving the question how these stages obtain most of their NADPH. T. gondii and other coccidia contain two NTH homologs (Table 1) but with unknown localization. A PDH-independent source for NAD+ might still be required, and it could come from the cytosol, given that a chloroplast-resident NAD+ transporter has been described in the plant Arabidopsis thaliana [85]. Taken together, although current knowledge is still limited, NADPH provision seems to differ substantially between P. falciparum and T. gondii, potentially providing the latter with more metabolic flexibility.

Concluding remarks

Initially considered “photosynthesis proteins” in the wrong place, years of research efforts to characterize apicomplexan ptFd and ptFNR biochemically, structurally, and genetically, now resulted in the definition of the crucial function of this redox system for parasite survival (Figure 1). While focusing on P. falciparum and T. gondii, the functions of ptFd/FNR as the central essential electron hub for more than one metabolic pathway in the apicoplast, in particular isoprenoid synthesis, should hold true also for the other Apicomplexa with this organelle. However, we lack knowledge on ptFd’s role in many other stages of the different life cycles. Examples for possible surprises can already be inferred from the apparent dispensability of PfDXPR in liver stages of P. berghei [54], which would imply that PfFd might be also less crucial and isoprenoid scavenging plays a role. Another exciting aspect comes from the recent emergence of data from outside the Apicomplexa field, which indicate that non-photosynthetic plastids with minimal metabolic capabilities could exist - without ptFd, as long as they got rid of all FeS enzymes and connected pathways (see also Outstanding Questions). Finally, based on the P. falciparum mevalonate bypass parasite line (and hopefully soon similar T. gondii tachyzoites), experiments can now be performed that were previously only possible in surrogate systems like bacteria or yeast, such as testing ptFd mutations in the right cellular context, i.e. the parasite and its host.

Outstanding Questions.

Is the ptFd redox system equally important in all life cycle stages?

Given the fact that Chromerida, the free-living phototrophic ‘cousins’ to the Apicomplexa, still also contain flavodoxin, could it replace ptFd in Apicomplexa? If so, in which reactions, and how conserved is this capability in other flavodoxins?

Is ptFd’s role in FeS synthesis similar to that of mtFd in mitochondria?

Depletion of lipoate synthesis in malaria parasites causes altered expression of proteins involved in redox regulation in both the apicoplast and the cytosol. Could it be a sign of apicoplast-to-cytosol redox signaling, known from plant chloroplasts? If so, what role does the ptFd redox system play in it?

How is ptFd/FNR involved in apicoplast redox balance?

What exactly is the NADPH source for ptFNR in the different Apicomplexa? Is there NAD+ import into the apicoplast similar to what has been observed in chloroplasts?

Fulfilling most criteria for a good drug target, how good are the prospects to find drug-like compounds inhibiting the ptFd redox system? For example, could chemoproteomic approaches lead to specific ‘molecular glues’, inhibiting the PPI between ptFd and its target enzymes?

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Plant-type ferredoxin in the apicoplast provides electrons derived from NADPH to several enzymes, all of which are iron-sulfur cluster-containing proteins.

Deletion of ferredoxin in P. falciparum blood stage parasites or T. gondii tachyzoites is lethal.

Methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis may be the most important ferredoxin-dependent pathway.

Lipoate synthesis, important for functional fatty acid synthesis in the apicoplast, and isoprenoid-dependent transfer RNA (tRNA) modification, also rely on ferredoxin.

Ferredoxin could be required for the biosynthesis of iron-sulfur cluster-containing proteins via the sulfur utilization factor (SUF) system in the apicoplast, but experimental evidence for this activity is still needed.

How NADPH supply, a requisite for the functioning of the ferredoxin redox system, occurs is still a matter of debate.

Acknowledgements

O.A.A. is supported by and F. S. is a member of the International Research Training Group 2290 “Molecular interactions in Malaria”, supported by the German Research Council (DFG). F.S. is supported by the Robert Koch-Institute. S.T.P. was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01 AI125534, and R.E. was supported by Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute postdoctoral fellowship. S.T.P. and R.E. were also supported by the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute, and the Bloomberg Philanthropies. We thank the reviewers for their constructive comments.

Glossary

- Electrons

These are negatively charged sub-atomic particles. In this review, we describe how electrons from ferredoxin are used by some enzymes in the apicoplast to break or form chemical bonds in metabolites during catalysis

- Endosymbiosis

the process whereby a phagotrophic cell engulfs, retains and eventually enslaves another cell known as the endosymbiont. In the context of Apicomplexa it refers to the acquisition of a plastid organelle from a red alga

- Endosymbiotic gene transfer

The flow of genes from an endosymbiont to the host nucleus. In Apicomplexa most apicoplast proteins are encoded in the nuclear genome and then transported post-translationally to the organelle via the secretory pathway with the aid of targeting sequences present in them

- Enzymes

These are biological catalysts (mostly proteins) that speed up the rate of biochemical reaction in living systems. Most of the proteins described in this review with which ferredoxin interacts are enzymes. Many, like FNR, require co-factors for activity

- Metabolic pathway

A series of chemical reactions in a living system linked together in a sequence often involving enzymes that convert substrates to products required for correct functioning of a biological system. Several of these metabolic pathways in the apicoplast relevant to the ferredoxin redox system are described

- Metabolite

The product of an enzymatic reaction, often as part of a pathway where the product of one reaction serves as the substrate for the subsequent step in the enzymatic cascade. For example, isoprenoids of the MEP pathway are metabolites

- Orthologues

Genes with common ancestry in different species, evolved through speciation over the course of evolution, but still retaining a common function. In this review, we predict the presence and/or functions of some genes in apicomplexan parasites based on the known activities of well-characterized orthologues from other organisms. They can be looked-up in a database called OrthoMCL DB

- S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)

a co-substrate involved in several enzymatic reactions, such as methyl group transfer or the generation of 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical. In the context of ferredoxin it is required by lipoate synthase- and MiaB-catalyzed reactions

- Transporters

Transmembrane proteins embedded in the lipid bilayer of biological membranes which aid the transfer of ions and small molecules across the membrane, sometimes requiring energy. Herein, we make reference to some membrane transporters and their roles in the exchange of metabolites between the apicoplast and other subcellular compartments or the host cell

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Smith NC, et al. (2021) Control of human toxoplasmosis. Int J Parasitol 51, 95–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su XZ, et al. (2019) Plasmodium Genomics and Genetics: New Insights into Malaria Pathogenesis, Drug Resistance, Epidemiology, and Evolution. Clin Microbiol Rev 32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Dooren GG and Striepen B (2013) The algal past and parasite present of the apicoplast. Annu Rev Microbiol 67, 271–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siddall ME (1992) Hohlzylinders. Parasitol Today 8, 90–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Köhler S, et al. (1997) A plastid of probable green algal origin in Apicomplexan parasites. Science 275, 1485–1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemgruber L, et al. (2013) Cryo-electron tomography reveals four-membrane architecture of the Plasmodium apicoplast. Malar J 12, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson RJ, et al. (1996) Complete gene map of the plastid-like DNA of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J Mol Biol 261, 155–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janouskovec J, et al. (2010) A common red algal origin of the apicomplexan, dinoflagellate, and heterokont plastids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 10949–10954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore RB, et al. (2008) A photosynthetic alveolate closely related to apicomplexan parasites. Nature 451, 959–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salomaki ED and Kolisko M (2019) There Is Treasure Everywhere: Reductive Plastid Evolution in Apicomplexa in Light of Their Close Relatives. Biomolecules 9, 378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ralph SA, et al. (2004) Tropical infectious diseases: metabolic maps and functions of the Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast. Nat Rev Microbiol 2, 203–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jomaa H, et al. (1999) Inhibitors of the nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as antimalarial drugs. Science 285, 1573–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vollmer M, et al. (2001) Apicomplexan parasites possess distinct nuclear-encoded, but apicoplast-localized, plant-type ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase and ferredoxin. J Biol Chem 276, 5483–5490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanke G and Mulo P (2013) Plant type ferredoxins and ferredoxin-dependent metabolism. Plant Cell Environ 36, 1071–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Przybyla-Toscano J, et al. (2018) Roles and maturation of iron-sulfur proteins in plastids. J Biol Inorg Chem 23, 545–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kloehn J, et al. (2021) The metabolic pathways and transporters of the plastid organelle in Apicomplexa. Curr Opin Microbiol 63, 250–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seeber F and Soldati-Favre D (2010) Metabolic pathways in the apicoplast of apicomplexa. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 281, 161–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nzuza N, et al. (2021) Diversification of Ferredoxins across Living Organisms. Curr Issues Mol Biol 43, 1374–1390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell IJ, et al. (2019) Evolutionary Relationships Between Low Potential Ferredoxin and Flavodoxin Electron Carriers. Front Energy Res 7, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atkinson JT, et al. (2016) Cellular Assays for Ferredoxins: A Strategy for Understanding Electron Flow through Protein Carriers That Link Metabolic Pathways. Biochemistry 55, 7047–7064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuyama K (2004) Structure and function of plant-type ferredoxins. Photosynth Res 81, 289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimata-Ariga Y and Morihisa R (2021) Functional analyses of plasmodium ferredoxin Asp97Tyr mutant related to artemisinin resistance of human malaria parasites. J Biochem 170, 521–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimata-Ariga Y, et al. (2020) C-terminal aromatic residue of Plasmodium ferredoxin important for the interaction with ferredoxin: NADP(H) oxidoreductase: possible involvement for artemisinin resistance of human malaria parasites. J Biochem 168, 427–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miotto O, et al. (2015) Genetic architecture of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Genet 47, 226–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stokes BH, et al. (2021) Plasmodium falciparum K13 mutations in Africa and Asia impact artemisinin resistance and parasite fitness. Elife 10, e66277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandini V, et al. (2002) Ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase and ferredoxin of the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii interact productively in Vitro and in Vivo. J Biol Chem 277, 48463–48471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aliverti A, et al. (2008) Structural and functional diversity of ferredoxin-NADP(+) reductases. Arch Biochem Biophys 474, 283–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milani M, et al. (2007) Ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase from Plasmodium falciparum undergoes NADP+-dependent dimerization and inactivation: functional and crystallographic analysis. J Mol Biol 367, 501–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kameda H, et al. (2011) Mapping of protein-protein interaction sites in the plant-type [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin. PLoS One 6, e21947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimata-Ariga Y, et al. (2007) Molecular interaction of ferredoxin and ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase from human malaria parasite. J Biochem 142, 715–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomsen-Zieger N, et al. (2004) A single in vivo-selected point mutation in the active center of Toxoplasma gondii ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase leads to an inactive enzyme with greatly enhanced affinity for ferredoxin. FEBS Lett 576, 375–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rekittke I, et al. (2013) Structure of the (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl-diphosphate reductase from Plasmodium falciparum. FEBS Lett 587, 3968–3972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imlay L and Odom AR (2014) Isoprenoid metabolism in apicomplexan parasites. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep 1, 37–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kennedy K, et al. (2019) Delayed Death by Plastid Inhibition in Apicomplexan Parasites. Trends Parasitol 35, 747–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swift RP, et al. (2020) A mevalonate bypass system facilitates elucidation of plastid biology in malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog 16, e1008316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nair SC, et al. (2011) Apicoplast isoprenoid precursor synthesis and the molecular basis of fosmidomycin resistance in Toxoplasma gondii. J Exp Med 208, 1547–1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saggu GS, et al. (2017) Characterization of 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl diphosphate synthase (IspG) from Plasmodium vivax and it’s potential as an antimalarial drug target. Int J Biol Macromol 96, 466–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Röhrich RC, et al. (2005) Reconstitution of an apicoplast-localised electron transfer pathway involved in the isoprenoid biosynthesis of Plasmodium falciparum. FEBS Lett 579, 6433–6438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swift RP, et al. (2022) Roles of Ferredoxin-Dependent Proteins in the Apicoplast of Plasmodium falciparum Parasites. mBio 13, e0302321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henkel S, et al. (2022) Toxoplasma gondii apicoplast-resident ferredoxin is an essential electron transfer protein for the MEP isoprenoid-biosynthetic pathway. J Biol Chem 298, 101468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li ZH, et al. (2013) Toxoplasma gondii relies on both host and parasite isoprenoids and can be rendered sensitive to atorvastatin. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Afanador GA, et al. (2014) Redox-dependent lipoylation of mitochondrial proteins in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Microbiol 94, 156–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allary M, et al. (2007) Scavenging of the cofactor lipoate is essential for the survival of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Microbiol 63, 1331–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crawford MJ, et al. (2006) Toxoplasma gondii scavenges host-derived lipoic acid despite its de novo synthesis in the apicoplast. Embo j 25, 3214–3222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foth BJ, et al. (2005) The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum has only one pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, which is located in the apicoplast. Mol Microbiol 55, 39–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomsen-Zieger N, et al. (2003) Apicomplexan parasites contain a single lipoic acid synthase located in the plastid. FEBS Lett 547, 80–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laine LM, et al. (2015) Biochemical and structural characterization of the apicoplast dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase of Plasmodium falciparum. Biosci Rep 35, e00171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Storm J and Müller S (2012) Lipoic acid metabolism of Plasmodium--a suitable drug target. Curr Pharm Des 18, 3480–3489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCarthy EL and Booker SJ (2017) Destruction and reformation of an iron-sulfur cluster during catalysis by lipoyl synthase. Science 358, 373–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frohnecke N, et al. (2015) Protein-protein interaction studies provide evidence for electron transfer from ferredoxin to lipoic acid synthase in Toxoplasma gondii. FEBS Lett 589, 31–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wrenger C and Müller S (2004) The human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum has distinct organelle-specific lipoylation pathways. Mol Microbiol 53, 103–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gisselberg JE, et al. (2013) The suf iron-sulfur cluster synthesis pathway is required for apicoplast maintenance in malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shears MJ, et al. (2015) Fatty acid metabolism in the Plasmodium apicoplast: Drugs, doubts and knockouts. Mol Biochem Parasitol 199, 34–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stanway RR, et al. (2019) Genome-Scale Identification of Essential Metabolic Processes for Targeting the Plasmodium Liver Stage. Cell 179, 1112–1128.e1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Biddau M, et al. (2021) Plasmodium falciparum LipB mutants display altered redox and carbon metabolism in asexual stages and cannot complete sporogony in Anopheles mosquitoes. Int J Parasitol 51, 441–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sidik SM, et al. (2016) A Genome-wide CRISPR Screen in Toxoplasma Identifies Essential Apicomplexan Genes. Cell 166, 1423–1435.e1412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krishnan A, et al. (2020) Functional and Computational Genomics Reveal Unprecedented Flexibility in Stage-Specific Toxoplasma Metabolism. Cell Host Microbe 27, 290–306.e211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liang X, et al. (2020) Acquisition of exogenous fatty acids renders apicoplast-based biosynthesis dispensable in tachyzoites of Toxoplasma. J Biol Chem 295, 7743–7752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Urbonavicius J, et al. (2001) Improvement of reading frame maintenance is a common function for several tRNA modifications. Embo j 20, 4863–4873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schweizer U, et al. (2017) The modified base isopentenyladenosine and its derivatives in tRNA. RNA Biol 14, 1197–1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Esberg B, et al. (1999) Identification of the miaB gene, involved in methylthiolation of isopentenylated A37 derivatives in the tRNA of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 181, 7256–7265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arcinas AJ, et al. (2019) Ferredoxins as interchangeable redox components in support of MiaB, a radical S-adenosylmethionine methylthiotransferase. Protein Sci 28, 267–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seeber F, et al. (2005) The plant-type ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase/ferredoxin redox system as a possible drug target against apicomplexan human parasites. Curr Pharm Des 11, 3159–3172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Okada M, et al. (2022) Critical role for isoprenoids in apicoplast biogenesis by malaria parasites. Elife 11, e73208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pamukcu S, et al. (2021) Differential contribution of two organelles of endosymbiotic origin to iron-sulfur cluster synthesis and overall fitness in Toxoplasma. PLoS Pathog 17, e1010096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pala ZR, et al. (2018) Recent Advances in the [Fe-S] Cluster Biogenesis (SUF) Pathway Functional in the Apicoplast of Plasmodium. Trends Parasitol 34, 800–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ellis KE, et al. (2001) Nifs and Sufs in malaria. Mol Microbiol 41, 973–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Law AE, et al. (2000) Bacterial orthologues indicate the malarial plastid gene ycf24 is essential. Protist 151, 317–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Charan M, et al. (2017) [Fe-S] cluster assembly in the apicoplast and its indispensability in mosquito stages of the malaria parasite. Febs j 284, 2629–2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumar B, et al. (2011) Interaction between sulphur mobilisation proteins SufB and SufC: evidence for an iron-sulphur cluster biogenesis pathway in the apicoplast of Plasmodium falciparum. Int J Parasitol 41, 991–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Charan M, et al. (2014) Sulfur mobilization for Fe-S cluster assembly by the essential SUF pathway in the Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast and its inhibition. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58, 3389–3398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haussig JM, et al. (2014) Identification of vital and dispensable sulfur utilization factors in the Plasmodium apicoplast. PLoS One 9, e89718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Renaud EA, et al. (2022) Disrupting the plastidic iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis pathway in Toxoplasma gondii has pleiotropic effects irreversibly impacting parasite viability. J Biol Chem 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weiler BD, et al. (2020) Mitochondrial [4Fe-4S] protein assembly involves reductive [2Fe-2S] cluster fusion on ISCA1-ISCA2 by electron flow from ferredoxin FDX2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 20555–20565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fleige T, et al. (2007) Carbohydrate metabolism in the Toxoplasma gondii apicoplast: localization of three glycolytic isoenzymes, the single pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, and a plastid phosphate translocator. Eukaryot Cell 6, 984–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lim L and McFadden GI (2010) The evolution, metabolism and functions of the apicoplast. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 365, 749–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cha SJ, et al. (2016) Identification of GAPDH on the surface of Plasmodium sporozoites as a new candidate for targeting malaria liver invasion. J Exp Med 213, 2099–2112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Daubenberger CA, et al. (2003) The N’-terminal domain of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of the apicomplexan Plasmodium falciparum mediates GTPase Rab2-dependent recruitment to membranes. Biol Chem 384, 1227–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Daubenberger CA, et al. (2000) Identification and recombinant expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Plasmodium falciparum. Gene 246, 255–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Swift RP, et al. (2020) The NTP generating activity of pyruvate kinase II is critical for apicoplast maintenance in Plasmodium falciparum. Elife 9, e50807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Janouškovec J, et al. (2019) Apicomplexan-like parasites are polyphyletic and widely but selectively dependent on cryptic plastid organelles. Elife 8, e49662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baroni S, et al. (2012) A single tyrosine hydroxyl group almost entirely controls the NADPH specificity of Plasmodium falciparum ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase. Biochemistry 51, 3819–3826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saeed S, et al. (2020) NAD(P) transhydrogenase has vital non-mitochondrial functions in malaria parasite transmission. EMBO Rep 21, e47832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang Q, et al. (2017) Proton-Translocating Nicotinamide Nucleotide Transhydrogenase: A Structural Perspective. Front Physiol 8, 1089–1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Palmieri F, et al. (2009) Molecular identification and functional characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana mitochondrial and chloroplastic NAD+ carrier proteins. J Biol Chem 284, 31249–31259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Blahut M, et al. (2020) Fe-S cluster biogenesis by the bacterial Suf pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 1867, 118829–118857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Braymer JJ, et al. (2021) Mechanistic concepts of iron-sulfur protein biogenesis in Biology. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 1868, 118863–118890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gervason S, et al. (2019) Physiologically relevant reconstitution of iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis uncovers persulfide-processing functions of ferredoxin-2 and frataxin. Nat Commun 10, 3566–3577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dorrell RG, et al. (2019) Principles of plastid reductive evolution illuminated by nonphotosynthetic chrysophytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 6914–6923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kayama M, et al. (2020) Highly Reduced Plastid Genomes of the Non-photosynthetic Dictyochophyceans Pteridomonas spp. (Ochrophyta, SAR) Are Retained for tRNA-Glu-Based Organellar Heme Biosynthesis. Front Plant Sci 11, 602455–602467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pierella Karlusich JJ, et al. (2015) Environmental selection pressures related to iron utilization are involved in the loss of the flavodoxin gene from the plant genome. Genome Biol Evol 7, 750–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Woo YH, et al. (2015) Chromerid genomes reveal the evolutionary path from photosynthetic algae to obligate intracellular parasites. Elife 4, e06974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cao P, et al. (2020) Structural basis for energy and electron transfer of the photosystem I-IsiA-flavodoxin supercomplex. Nat Plants 6, 167–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cobbold SA, et al. (2021) Non-canonical metabolic pathways in the malaria parasite detected by isotope-tracing metabolomics. Mol Syst Biol 17, e10023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vial HJ, et al. (1984) A reevaluation of the status of cholesterol in erythrocytes infected by Plasmodium knowlesi and P. falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol 13, 53–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Penna-Coutinho J, et al. (2011) Antimalarial activity of potential inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum lactate dehydrogenase enzyme selected by docking studies. PLoS One 6, e21237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yeh E and DeRisi JL (2011) Chemical rescue of malaria parasites lacking an apicoplast defines organelle function in blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol 9, e1001138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Baumeister S, et al. (2011) Fosmidomycin uptake into Plasmodium and Babesia-infected erythrocytes is facilitated by parasite-induced new permeability pathways. PLoS One 6, e19334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Garcia CK, et al. (1994) Molecular characterization of a membrane transporter for lactate, pyruvate, and other monocarboxylates: implications for the Cori cycle. Cell 76, 865–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Castella B, et al. (2017) The ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 regulates phosphoantigen release and Vγ9Vδ2 T cell activation by dendritic cells. Nat Commun 8, 15663–15676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.George KW, et al. (2018) Integrated analysis of isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) toxicity in isoprenoid-producing Escherichia coli. Metab Eng 47, 60–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Esakova OA, et al. (2021) Structural basis for tRNA methylthiolation by the radical SAM enzyme MiaB. Nature 597, 566–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mirdita M, et al. (2022) ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat Methods 19, 679–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.