Abstract

This review analyzes new data on the mechanism of ultrafast reactions of primary charge separation in photosystem I (PS I) of cyanobacteria obtained in the last decade by methods of femtosecond absorption spectroscopy. Cyanobacterial PS I from many species harbours 96 chlorophyll a (Chl a) molecules, including six specialized Chls denoted Chl1A/Chl1B (dimer P700, or PAPB), Chl2A/Chl2B, and Chl3A/Chl3B arranged in two branches, which participate in electron transfer reactions. The current data indicate that the primary charge separation occurs in a symmetric exciplex, where the special pair P700 is electronically coupled to the symmetrically located monomers Chl2A and Chl2B, which can be considered together as a symmetric exciplex Chl2APAPBChl2B with the mixed excited (Chl2APAPBChl2B)* and two charge-transfer states P700+Chl2A− and P700+Chl2B−. The redistribution of electrons between the branches in favor of the A-branch occurs after reduction of the Chl2A and Chl2B monomers. The formation of charge-transfer states and the symmetry breaking mechanisms were clarified by measuring the electrochromic Stark shift of β-carotene and the absorption dynamics of PS I complexes with the genetically altered Chl2B or Chl2A monomers. The review gives a brief description of the main methods for analyzing data obtained using femtosecond absorption spectroscopy. The energy levels of excited and charge-transfer intermediates arising in the cyanobacterial PS I are critically analyzed.

Keywords: Photosystem I, Primary charge separation, Electron transfer, Femtosecond absorption spectroscopy

Introduction

Solar energy conversion in oxygenic photosynthesis occurs in the two types of pigment-protein complexes known as photosystem I (PS I) and photosystem II (PS II). Whereas PS I operates at extremely low redox potential of −1 V vs NHE, which is necessary for the reduction of NADP+, PS II generates extremely high oxidative potential of +1 V vs NHE required for water photolysis (Nelson 2013). The core complexes of PS I and PS II are generally well conserved and, in both, chlorophyll (Chl) a represents the main pigment participating in light harvesting and in primary photochemical reactions, which occur in a functionally specialized compartment known as the reaction center (RC).

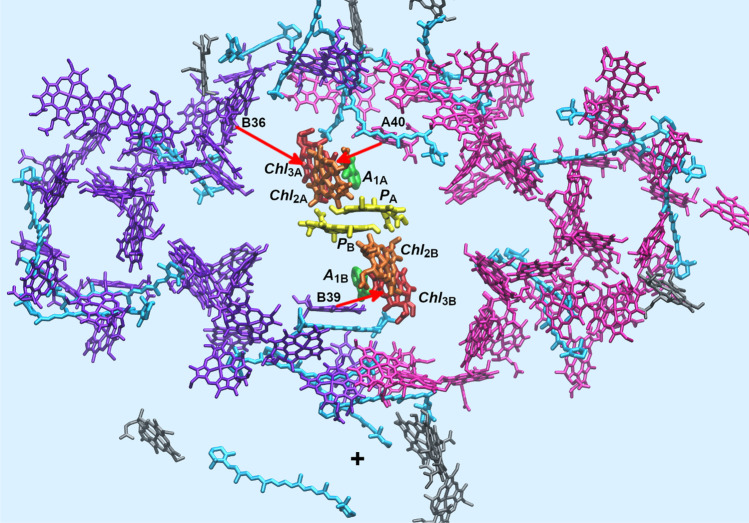

This review discusses energy and electron transfer in PS I complexes by means of femtosecond time-resolved optical techniques. A detailed description of the method of broadband femtosecond pump-probe spectroscopy can be found in the review by (Berera et al. 2009). PS I of plants, algae and cyanobacteria includes also the light-harvesting antenna (LHA) integrated in one structurally unified pigment-protein complex (Byrdin et al. 2002; Fromme et al. 2001; Jordan et al. 2001; Malavath et al. 2018; Mazor et al. 2014; Mazor et al. 2017). The LHA of cyanobacteria contains 90 Chl a and 22 β-carotene molecules separated from the redox active pigments of the RC by a protein layer about 2 nm in thickness (Fig. 1). In contrast to the bacterial RC and PS II, the light-harvesting pigments of the PS I are embedded in the same protein as the redox-active pigments of the RC and cannot be detached from the latter. This creates a challenge for studying the molecular mechanism of primary charge separation because energy migration and electron transfer are intimately connected, each process being “entangled” with the other (Savikhin and Jankowiak 2014). The monomeric PS I complexes from cyanobacteria Thermosynechococcus elongatus and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 are comprised of 14 protein subunits from which the central subunits PsaA and PsaB obey almost strict C2-symmetry (Jordan et al. 2001). Three PS I monomers form a trimeric supercomplex, which obeys the C3-symmetry (Mazor et al. 2014). The redox active pigments in the RC of the PsaA/PsaB heterodimer include six Cha and two phylloquinone molecules, which form two symmetrical redox cofactor branches labeled A and B (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Cofactors of the monomeric PS I complex from the cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus (Jordan et al. 2001). Shown are macrocycles of chlorophyll molecules in the antenna (PsaA subunit - magenta, PsaB - violet, peripheral subunits - gray) and the reaction center (P700 - yellow, Chl2 - orange, Chl3 - mulberry), b-carotene molecules (light blue), and heterocycles of phylloquinone A1 (green). The cross denotes the C3-symmetry axis of the trimer supercomplex. The red arrows mark the main pathways for the excitation energy transfer from the antenna to the reaction center (Byrdin et al. 2002; Kramer et al. 2018)

Fig. 2.

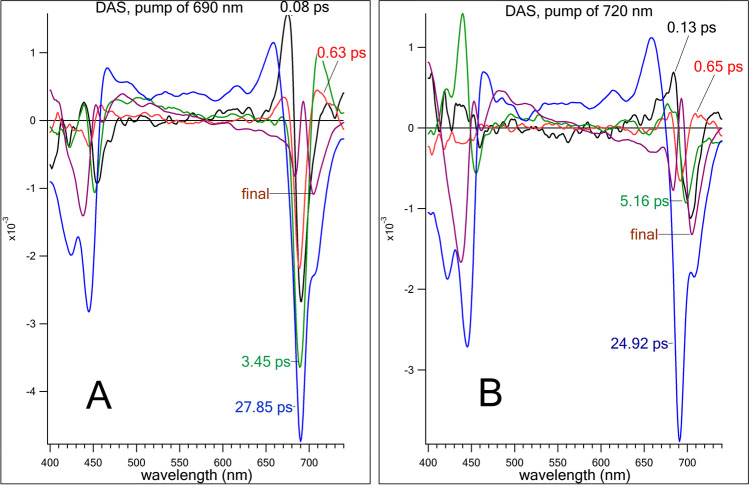

Two branches of redox-active cofactors and the bifurcating electronic transitions in the RC of PS I. A. The cofactors include symmetrical pairs of chlorophyll PA/PB (yellow), Chl2A/Chl2B (orange), Chl3A/Chl3B (red), and phylloquinone A1A/A1B (green). Water molecules (silver spheres) coordinated by the PsaA-N600 and PsaB-N582 asparagine side chains (cyan) serve as the axial ligands to Chl2B and Chl2A. B. The bifurcated kinetic scheme illustrates the key role of the symmetric tetrameric exciplex Chl2APAPBChl2B (red box) in which the excited state (Chl2APAPBChl2B)* is quantum mechanically mixed with two charge-transfer states P700+Chl2A− and P700+Chl2B−. A redistribution of the unpaired electron between the two branches in favor of the A-branch takes place in the picosecond time scale

A special pair of Chl a/a’ molecules, P700, joins the branches near the luminal side of the thylakoid membrane. P700 is assembled from monomers PA and PB (structurally considered as Chl1A and Chl1B), which are coupled by strong dipole-dipole and short-range intermolecular interactions (Madjet et al. 2009) and function as the excitation energy sink for energy trapping (Adolphs et al. 2010; Kramer et al. 2018; Yang et al. 2003). Each of the branches includes two Chl a molecules, Chl2 and Chl3, alternatively called Aacc and A0, bound in the ec2 and ec3 sites, respectively. The second Chl2 is a structural analog of the accessory (bacterio)chlorophyll in the bacterial RC and PS II complexes, where this pigment functions as a primary electron acceptor. In PS I, the exact sequence of primary electron transfer events and the functional role of Chl2 as the primary acceptor is still a matter of controversy (Cherepanov et al. 2017a, 2021; Molotokaite et al. 2017; Müller et al. 2003; Müller et al. 2010; Savikhin & Jankowiak 2014; Shelaev et al. 2010). The PsaA and PsaB subunits also bind a phylloquinone molecule in each of the A1A and A1B sites which function as a secondary electron acceptor. The branches converge at the FX iron-sulfur cluster, which is located at the pseudo C2-axis near the stromal side of the PsaA/PsaB heterodimer.

Six Chl a molecules in the RC of PS I are excitonically coupled (Gibasiewicz et al. 2003; Yin et al. 2007). P700 has the lowest excitation energy (the QY band at 700 nm) compared to other two Chl pairs (Chl2A/Chl2B and Chl3A/Chl3B) in the RC, and has been considered as the primary electron donor (Brettel and Leibl 2001). The Chl a molecules Chl2 and Chl3 have similar spectral properties (the QY band of both molecules was determined at ~685 nm (Cherepanov et al. 2021; Dashdorj et al. 2004; Savikhin et al. 2001). The Chl2 and Chl3 molecules in both A and B branches were observed as functionally unified electron acceptors A0A and A0B (Badshah et al. 2018; Chauvet et al. 2012; Cherepanov et al. 2020a; Shuvalov et al. 2007). The Chl3A and Chl3B molecules are the bottleneck gateways on the excitation transfer pathways from the antenna to the reaction center (marked by red arrows in Fig. 1, see (Byrdin et al. 2002; Kramer et al. 2018).

The LHA complex is substantially heterogeneous, both structurally and spectrally, where diverse types of Chl clusters can be distinguished spectroscopically (Owens et al. 1987; Beauregard et al. 1991; Brecht et al. 2008; Brüggemann et al. 2004; Byrdin et al. 2000; Byrdin et al. 2002; Cheng et al. 2007; Chenu and Scholes 2015; Cherepanov et al. 2017a; Cherepanov et al. 2017b; Cherepanov et al. 2020c, d; Dashdorj et al. 2004; Fromme et al. 2001; Fuller et al. 2014; Giera et al. 2010; Giera et al. 2018; Hastings et al. 1994; Hastings et al. 2002; Holzwarth et al. 1993; Holzwarth et al. 2005; Ihalainen et al. 2005; Laible et al. 1994; Mazor et al. 2014; Melkozernov et al. 2000a; Melkozernov et al. 2000b; Melkozernov et al. 2000c; Melkozernov et al. 2006; Müller et al. 2003; Müller et al. 2010; Pålsson et al. 1998; Pawlowicz et al. 2007; Savikhin et al. 1999; Searle et al. 1988; Shelaev et al. 2010; Slavov et al. 2008; Trissl 1993, b; Akhtar and Lambrev 2020; Akhtar et al. 2018; Akhtar et al. 2021; Proppe et al. 2020; Zamzam et al. 2019). Several long-wavelength chlorophyll (LWC) forms absorbing below P700 were found in the LHA core of PS I (Akhtar and Lambrev 2020; Akhtar et al. 2018; Giera et al. 2018; Gobets et al. 2001b; Goyal et al. 2022; Herascu et al. 2016; Holzwarth et al. 2005; Ihalainen et al. 2005; Melkozernov et al. 2000c; Pålsson et al. 1998; Rätsep et al. 2000; Trissl 1993; Van Stokkum et al. 2004; Zazubovich et al. 2002).

To measure the kinetics of ultrafast charge separation involving P700, it is necessary to use ultrashort pulses. These pulses inherently have a wide spectrum. A broad-spectrum femtosecond pulse inevitably excites the LHA. Selective excitation of P700 is not possible because of the unavoidable presence of the LWC forms, the transient spectra of which overlap with the transient spectra of P700. This circumstance complicates the interpretation of the transient kinetics of the primary charge separation in RC. To increase the contribution of the transient absorption of RC (P700 and A0) in relation to antenna, several approaches were employed: 1) using PS I complexes with low amount of red-antenna chlorophyll, e.g. from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803; 2) tuning pump pulse to the main P700 absorption QY band; 3) modification of PS I by site-specific mutagenesis; 4) study of P700 complexes with long-wavelength Chl forms Chl f and Chl d. Fine tuning of the pump pulse spectrum to the QY band of P700 requires a narrow bandwidth, which results in decrease of temporal resolution. To achieve high temporal resolution, a broadband pulse centered e.g. ~720 nm can be used. This approach is justified in the case of PS I with low amount of red antenna chlorophyll, such as PS I from cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803.

Methods for the analysis of transient absorption dynamics

Pump–probe spectroscopy examines the excited state dynamics related to the third-order nonlinearity (Yan and Mukamel 1990). The pump pulse affects the sample by changing the energy level population of chromophores, so the population of excited states increases at the expense of the ground state. In a typical pump–probe experiment several effects are observed: increase of the transmission of the probe pulse due to the ground state depletion (ground state bleaching, GSB); absorption of the probe pulse by the excited state of chromophore (excited state absorption, ESA). In addition, when the probe pulse is resonant with the transition of the lowest excited state to the ground state, an increased transmission is observed (stimulated emission, SE). As a whole, the observed absorption difference spectra ΔA(λ,t) reflect the excited state dynamics and subsequent photochemical reactions on a time scale from tens of femtoseconds to several nanoseconds (Berera et al. 2009).

To quantify the photochemical transitions, the spectral dynamics should be analyzed by using numerical approaches that approximate the spectral-temporal matrix ΔA(λ,t) in terms of mathematical models. Several assumptions on the specificity of photochemical processes in PS I are commonly accepted. The common assumption is that the kinetic behavior is homogeneous and can be described by a small number of kinetic parameters associated with the dynamics of several individual members of an ensemble of pigments. Since the light-harvesting antenna of PS I includes about hundred pigments, describing the processes of energy migration in terms of several kinetic parameters is an obvious oversimplification. In contrast to energy transfer, the kinetic homogeneity seems to be more applicable to the electron transfer reactions in the two branches of redox-active cofactors in the RC.

Homogeneous models

A common assumption, known as the Beer–Lambert law, approximates the total absorption of the system by the sum of the contributions of n different electronic states weighted by their concentration:

| 1 |

where εj(λ) and cj(t) denote the spectrum and concentration of the state j. In some cases, there is an a priori information on concentration dynamics (kinetic model) or spectral properties (spectral model) of electronic states that imposes certain constraints on the functional forms in this equation.

Kinetic models

If the photochemical processes can be described in terms of first order kinetics by linear differential equations, their solution represents a sum of exponential decay functions

| 2 |

The respective Decay-Associated Spectra (DAS) Sj(λ) and the decay times τj can be obtained by global multi-exponential decomposition (Beechen and Ameloot 1985). In this approximation, the decay times τj are considered as roots (eigenvalues) of the characteristic polynomial of the system of linear differential equations:

| 3 |

where the kinetic matrix K describes transitions between n electronic states and the vector denotes external transitions being equal to zero for conservative kinetic systems (Shinkarev 2006).

While quantitative evaluation of the number n, the amplitudes Sj(λ) and the decay times τj of the decomposition (2) is mathematically reliable (Provencher 1976), it is impossible to determine the coefficients of the kinetic matrix K and the kinetic components ĉ(t) from the experimental data without additional assumptions, since any rotation of the vector ĉ(t) by an orthogonal transformation U in the ℝn space, K′ = U−1KU, does not change the characteristic roots. In other words, a single set of DAS in (2) corresponds to an infinite number of different kinetic models (3), the choice between which can be made on the basis of additional information.

In the simplest case, which describes well the charge transfer reactions within PS I, it is possible to enumerate the DAS components in accordance with increasing decay times and to consider formally n sequential kinetic transitions:

| 4 |

The difference spectrum of the intermediate k is expressed through the DAS components in simple terms:

| 5 |

If the decay times differ significantly, τ1 < < τ2 < <… < < τn, the observed decay times τi are approximately equal to the inverse rate constants ki.

It is worth noting that the two active electron transfer branches in the RC of PS I differ slightly in their kinetic properties, so a more accurate description of the kinetics requires branching kinetic models with different kinetic constants in each of the branches (Cherepanov et al. 2020a, 2021; Molotokaite et al. 2017; Müller et al. 2010).

Spectral models

An alternative method of the spectral analysis employs assumption that the absorption and bleaching bands of spectral intermediates have the Gaussian shape. In this case, the spectral-temporal matrix is decomposed into Gaussian components:

| 6 |

In this approximation, the Gaussian position λj(t) and dispersion σj parameters are subjects of nonlinear minimization while the amplitudes Aj(t) are found by linear regression. This approximation is applicable for practical purposes if there are some specific spectral markers, e.g. the electrochromic shift of carotenoid band at ~500 nm (Cherepanov et al. 2020a).

Principal components

Constraints on the decomposition (1) can be effectively relaxed by using the method of principle components (Segtnan et al. 2001; Tzeng and Berns 2005). The principal component analysis (PCA) is model-independent method, which does not require a priori assumptions on the kinetic or spectral properties. In this method, the matrix ΔA(λ, t) is expanded in a series

| 7 |

where Sj(λ) is the spectrum and Tj(t) is its time-dependent contribution (score) of the jth component (Esbensen and Geladi 2009). The first principal component (j = 1) accounts for the highest possible variation of ΔA(λ, t), the second for the largest remaining variation, and so on until the residual nonsystematic noise is reached. In matrix terms, the PCA is an orthogonal rotation T

| 8 |

where the score matrix T (m × p) represents a projection of the experimental matrix ΔA(t, λ) of the dimension (m × n) to a small number p of collective variables (principal components) combined into a load matrix S (n × p), and E is the residual (m × n) matrix, which is minimized. The following constraints are imposed on the PCA transformation:

i) T is orthogonal: (9).

ii) S is orthonormal: STS=I (I is the identity matrix); (10).

The components of T are ordered according to their descending size, they are found by the method of singular value decomposition (Wall et al. 2005).

The PCA was used to quantify mutation-induced shifts of equilibrium between the excited state of primary donor P700* and the primary charge-separated state P700+Chl2− in three pairs of PS I complexes from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 with residues PsaA-N600 or PsaB-N582 (coordinating Chl2B or Chl2A through a H2O molecule) substituted by Met, His, and Leu (Cherepanov et al. 2021).

Inhomogeneous models

In many cases the photochemical processes cannot be treated in the framework of homogeneous models. Particularly, energy migration through a network of exciton-coupled pigments in the LHA of the PS I complexes from cyanobacteria Thermosynechococcus elongatus and Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 cannot be described in such terms (Melkozernov et al. 2001). In a more general case, the inhomogeneous kinetics arise due to effects of conformational heterogeneity of the chromophore environment. The impact of conformational mobility on electronic transitions may manifest itself in two distinct ways. First, inhomogeneous patterns may appear as time-dependent shifts of the ESA (Smitienko et al. 2021) and SE (Khyasudeen et al. 2019; Silori et al. 2020) bands prompted by coherent conformational dynamics. The mathematical description of such conformational gating is based on stochastic diffusion equations, which generally lead to nonexponential kinetics (Cherepanov et al. 2001; Medvedev et al. 2006; Nadler and Marcus 1987; Sumi and Marcus 1986). Second, inhomogeneous spectral broadening and non-exponential kinetics appear when the conformational mobility of the polar environment (pigment-protein complex and solvent) is slower than the electronic transition (static heterogeneity); in such cases the observed kinetics N(t) is approximated by a model with distributed (blurred) parameters (Gorka et al. 2020; McMahon et al. 1998; Palazzo et al. 2002):

| 11 |

where the variation of reaction rate constant k is characterized by a distribution function ρ(k). The eq. (11) is Laplace transform of the function ρ(k). If ρ(k) is sharp, the kinetics N(t) is monoexponential. For systems with static heterogeneity, the distribution ρ(k) can be calculated by inverse Laplace transform of the observed nonexponential kinetics, this method is implemented in the programs CONTIN (Provencher 1982) and MemExp (Steinbach et al. 2002). Both programs were applied to analyze inhomogeneous processes of energy migration in the LHA and electron transfer reactions in RC (Cherepanov et al. 2018, 2021; Malferrari et al. 2016, Kurashov et al. 2018; Milanovsky et al. 2019) of PS I from the cyanobacteria Thermosynechococcus elongatus and Synechocystis sp. PCC6803.

Sequence of charge separation reactions in photosystem I

The exact sequence of electron transfer events in PS I remains incompletely understood in spite of active study. Unambiguous identification of intermediates arising in the primary charge separation reactions and determination of their kinetic characteristics are hampered by two prerequisites: the transfer of excitation energy to RC should not limit the subsequent electron transfer within RC, and the spectral characteristics of the charge-transfer states must differ from the difference spectra of excited LHA. Unfortunately, both of these conditions are extremely difficult to fulfill in the native PS I. There are currently two alternative views on the nature of the primary electron donor: whether it is the P700 from which an electron is ejected down either of the two branches of electron carriers with the formation of the primary ion-radical pairs P700+A0A− or P700+A0B− (Melkozernov et al. 2000a; Savikhin and Jankowiak 2014; Shelaev et al. 2010), or it is any of the two Chl molecules symmetrically located in the positions Chl2A and Chl2B, so the primary ion-radical states are Chl2A+Chl3A− and Chl2B+Chl3B− (Donato et al. 2011; Holzwarth et al. 2006; Müller et al. 2003; Nürnberg et al. 2018; Zamzam et al. 2019).

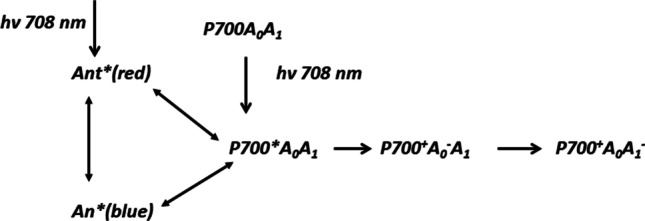

The first mechanism was supported by measurements of the absorption transients associated with electron transfer through the primary electron acceptor A0 in the RC of PS I isolated from spinach (~45 Chl molecules per RC) after excitation by low intensity femtosecond laser pulses at 708 nm, duration of <50 fs (White et al. 1996). Authors suggested that at this wavelength the electron donor P700 is excited directly, although some antenna chlorophylls are also excited. Transient spectra were measured for reduced and oxidized states of P700. Experimental data were interpreted in terms of classical scheme:

The difference spectrum (A0−-A0) does not appear promptly but takes ~3 ps to reach maximum intensity and resembles those previously obtained spectra with a maximum bleaching at 685 nm and a shoulder in the region 670–675 nm. In this system the intrinsic rate constant of the primary radical pair P700+A0− formation cannot be measured directly due to a fast energy migration in the antenna, but the kinetic modelling by Scheme 1 gave an estimate of the intrinsic time of about 1.4 ps (White et al. 1996). Even a shorter estimate of 0.8–1.5 ps was obtained in chemically modified PS I preparations (Kumazaki et al. 2001). The results of femtosecond pump/infrared-probe spectroscopy with excitation at 700 nm revealed the appearance of Chl cation signal already at 200 fs delay (Donato et al. 2011).

Scheme 1.

Energy and charge transfer reactions in PS I from Spinacea oleracea, adapted from (White et al., 1996)

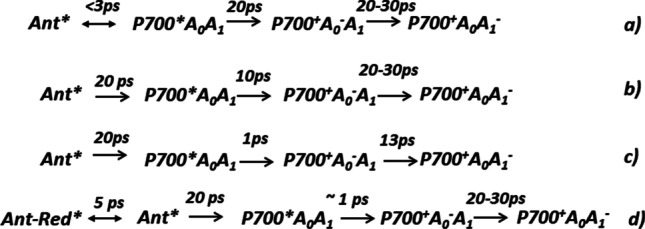

Scheme 2 summarizes variants of charge separation in PS I suggested by different groups. These hypotheses have the general assumption that charge transfer occurs according to the classical mechanism, i.e. the charge separation starts from the excited P700* forming a primary ion-radical state P700+A0−A1 and then a secondary ion-radical pair P700+A0A1−. All groups of researchers agree that the characteristic time of the secondary ion-radical pair P700+A0A1− formation is 20–40 ps. The characteristic times of the intermediate stages of energy and electron transfer differ significantly, which is due to the ambiguity of the global analysis of the femtosecond transient spectra.

Scheme 2.

Suggested charge separation mechanisms for a) RC from C. reinhardtii and cyanobacterial PS I (Gibasiewicz et al. 2001; Melkozernov 2001); b) RC from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Savikhin et al. 2000) c) revised scheme for RC from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Savikhin et al. 2001) d) cyanobacterial PS I (Gobets et al. 2001b, a; Gobets and Van Grondelle 2001)

Müller et all analyzed the energy transfer and charge separation mechanisms in PS I core particles from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii derived from ultrafast transient absorption measurements in the femtosecond-to-nanosecond time range (Holzwarth et al. 2006; Müller et al. 2003; Müller et al. 2010). Excitation was carried out by 60 fs laser pulses with a full-width at half-maximum of 8–9 nm. Transient absorption spectra have been measured upon excitation of PS I at 670 nm (only antenna excited) and 700 nm (primarily RC excitation) with open and closed RC. Based on the global kinetic analysis, alternative mechanisms for the primary charge separation processes were considered in the framework of the results (Scheme 3):

Scheme 3.

Complementary interpretations of transient spectral intermediates and characteristic times of main electronic transitions in PS I core particles from C. reinhardtii. Adapted from (Müller et al. 2003)

Müller and coworkers interpreted their data that the Chl2 (or Aacc) molecules serve in PS I as a primary donor and Chl3 (or A0) as a primary acceptor (Holzwarth et al. 2006; Müller et al. 2003; Müller et al. 2010). The main reason for considering Chl2 as the primary donor was the presence of the 6–9 ps kinetic component with a small amplitude, which was attributed to the primary ion-radical pair RP1 with bleaching minima at ~696 nm (Chl2) and ~ 680 nm (Chl3) (Müller et al. 2003; Müller et al. 2010). The analysis of transient absorbance of PS I complexes from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 with the genetically altered Chl2A and Chl2B monomers allowed us to determine the position of the QY band of Chl2 at 687 nm (Cherepanov et al. 2021), which turned out to be very close to the QY band of Chl3 at ~685 nm (Dashdorj et al. 2004; Savikhin et al. 2001). The equivalence of the spectral properties of Chl2 and Chl2 casts doubt on such an interpretation of the RP1 component suggested by Müller and coworkers.

An important difference between the two mechanisms should manifest itself in the electrochemical properties of Chl2. In the classical scheme, Chl2 has a reduction potential close to that of Chl3, so that the unpaired electron is distributed between the second and third monomers in favor of Chl3 (Ptushenko et al. 2008). In other words, Chl2 and Chl3 are treated as an electronically coupled dimer, A0, where the unpaired electron occupies a collective singly occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) representing combination of the LUMO orbitals of two monomers. In the alternative mechanism, the Chl2 monomer has an oxidation potential close to that of the P700 dimer (the HOMO orbitals of neutral Chl2 and P700 have close energies), so the electron hole is distributed between Chl2 and P700.

Gorka and coauthors recently measured by CW and pulsed EPR spectroscopy the electron-nuclear hyperfine couplings of the A0 radical-anion in PS I from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, which revealed a delocalization of the electron spin density between Chl2 and Chl3 monomers (Gorka et al. 2021b). The DFT calculations of hyperfine coupling allowed them to estimate the delocalization of electron spin density between Chl3A and Chl2A rings, which was asymmetric in favor of Chl3A by a factor of 3:1. Although the Chl2 and Chl3 macrocycles have substantially different chemical environments (Chl2A/2B are coordinated to a water ligand and Chl3A/3B to a sulfur ligand from methionine residues Met684PsaA and Met659PsaB, respectively (Jordan et al. 2001), the delocalization of unpaired electron within the Chl2AChl3A heterodimer is very similar to the delocalization of unpaired electron within the symmetrical electronically coupled Chl1AChl1B cation-radical (Gorka et al. 2021a; Madjet et al. 2009). Fine tuning of the energy levels of Chl monomers is necessary to creation of a common delocalized singly occupied orbital, it looks as an important universal principle allowing efficient electron transfer over long distances with a high quantum yield and minor recombination reactions (Gorka et al. 2021b).

Since the direct excitation of RC is difficult due to the presence of a large amount of Chl in the LHA, Shelaev et al. studied PS I from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 by application of pump–probe technique with 20-fs low-energy pump pulses centered at 720 nm. The appearance of a specific double-well bleach with minima at 690 and 705 nm registered at a short time delay upon low-energy excitation (Fig. 3) was interpreted as an ultrafast formation of charge-transfer state P700+A0− in PS I (Shelaev et al. 2010). Similar spectral feature was observed in the SMA-PSI complexes from T. elongatus isolated via a new detergent-free method using styrene-maleic acid copolymers.

Fig. 3.

Transient absorption spectra of PS I from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 by application of pump–probe technique with 20-fs low-energy pump pulses centered at 700 nm (A) and at 720 nm (B). Arrows indicate two bleach peaks arising under excitation at 720 nm. These bleach peaks suggest bleaching of P700 (~705 nm) and A0 (~690 nm)

The energy and electron transfer transitions of PS I in these experiments were assessed using DAS decomposition of the transient absorption changes by Eq. (2). Excitation of the PS I complex from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 at 690 nm induced a cascade of energy transfer transitions in a time range of 0.1–3 ps, the DAS components of which in the Qy region overlap with the changes caused by the reduction of A0 (Fig. 4A). Only the DAS component with τ = 28 ps was reliably attributed to the A0− reoxidation (Fig. 4A, blue). In the case of low-energy excitation, only minor spectral changes in the region of 690 nm in the time interval of 0.1–10 ps were observed, whereas the slow 25 ps component attributed to the A0− reoxidation was predominant (Fig. 4B). Although the energy transfer processes in the antenna were in good agreement with previous interpretations, the authors suggested a revised mechanism of charge separation.

Fig. 4.

Decay-associated spectra of the transient absorption dynamics of PS I from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 upon excitation at 690 nm (A) and 720 nm (B)

The ultrafast (~100 fs) conversion of delocalized exciton into charge-separated state between the primary donor P700 (bleaching at 705 nm) and the primary acceptor A0 (bleaching at 690 nm) was observed (Shelaev et al. 2010). The earliest (<180 fs) absorbance bleaching at 690 nm was also observed when the pump pulse was centered at 760 nm and the wavelength components shorter than 740 nm were cut by Spatial Light Modulator (SLM) lowpass filter, which allowed selective excitation of RC without involvement of LHA (Cherepanov et al. 2017a). An ultrafast (<100 fs) bleaching at 690 nm was observed also in the PS I complexes isolated from Thermosynechococcus elongatus via a new detergent-free method using styrene-maleic acid copolymers (SMA-PS I) excited at 740 nm, but not via conventional n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside solubilization (DM-PSI).

The ultrafast (τ ≤ 100 fs) formation of double-well bleaching at 690 nm and 704 nm in PS I from Synechocystis PCC 6803 was interpreted as an indication of adiabatic mixture of excited P700* and ion-radical P700+A0A− and P700+A0B− states (Cherepanov et al. 2017a) similarly to the ultrafast intradimer electron transfer (τ = 170 fs) observed in synthetic chlorophyll analogues (Giaimo et al. 2002). Such ultrafast charge separation may proceed due to strong electronic coupling between P700 and A0 in the RC (Gibasiewicz et al. 2003; Yin et al. 2007) and considerable electron-phonon interactions in PS I mixing neutral exciton and polar CT states (Cherepanov et al. 2018; Ihalainen et al. 2003).

Excitation in the maximum of P700 absorption generates electronic states with the highest contribution from P700*, whereas excitation in the far-red edge predominantly generates charge transfer state P700+A0− in both branches of redox-cofactors (Fig. 5). The three-level model accounts for a flat-bottomed potential surface of the excited state and adiabatic character of electron transfer between P700 and A0, providing a microscopic explanation of the ultrafast formation of P700+A0−and exponential decline of PS I absorption red shoulder.

Fig. 5.

Effective energy profiles along the reaction coordinate in the adiabatic model of PS I. Diabatic energy terms for ground (black solid), excited (blue dashed) and CT (green and red dashed) states were calculated with parameters ΔG0 = −0.06 eV, λ =0.12 eV, U0 = 1.8 eV; the adiabatic terms with |Vab| =0.1 eV. Bars show the Boltzmann thermal distribution in the ground state. Adapted from (Cherepanov et al. 2017a)

The primary charge separation reactions were also studied in the PS I complexes from cyanobacterium Fischerella thermalis PCC 7521 grown under white-light (WL-PSI) and far-red light (FRL-PSI) illumination (Cherepanov et al. 2020b), the latter complexes contained 7 Chl f molecules in the LHA (Gisriel et al. 2020). The experimental data were analyzed using a classic kinetic scheme of charge separation, which includes reversible transitions between the excited LHA, the exited RC and the primary ion-radical pair P700+A0−, but irreversible reduction of A1:

| 12 |

Whereas the excitation energy exchange between LHA and RC, τ1 = 1/(k1 + k−1), and the secondary electron transfer, τ2 = 1/k2, proceed on a time-scale of several picoseconds (Chauvet et al. 2012; Gibasiewicz et al. 2001; Savikhin and Jankowiak 2014), formation of the ion-radical state P700+A0− completes within a timescale τCT ≤ 200 fs. The kinetic model (12) has a simple analytical solution as a sum of two exponential terms, which allowed determining the rate constants k1, k−1 and k2 from the absorption dynamics; the energy level of the primary charge-separated state [P700+A0−] relative to the excited state of the antenna, determined in this way for PS I from F. thermalis PCC 7521 (Cherepanov et al. 2020b) and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Cherepanov et al. 2021), turned out to be only 10–60 meV lower. These estimates were in good agreement with the data obtained by the time-resolved fluorescence method (Giera et al. 2010).

Recently Akhtar et al. (Akhtar et al. 2021) employed two dimensional coherent electronic spectroscopy to follow the dynamics of energy and electron transfer in a monomeric PS I complex from Synechocystis PCC 6803, containing only subunits A − E, K, and M, at 77 K. In this work, specific bidentate spectral feature in the QY band, which was previously ascribed to the quantum mixing of exciton and charge-transfer states in the RC (Shelaev et al. 2010; Cherepanov et al. 2017b, a, b, 2021) was registered. The absorptive 2D electronic spectra revealed fast excitonic/vibronic relaxation on time scales of 50–100 fs from the high-energy side of the absorption spectrum. Antenna excitations were funneled within 1 ps to a small pool of chlorophylls absorbing around 687 nm, thereafter decaying with 4–20 ps lifetimes, independently of excitation wavelength. The rate of primary charge separation, upon direct excitation of the RC was determined to be 1.2–1.5 ps − 1. The authors suggested activationless electron transfer in PS I (Akhtar et al. 2021).

Bidirectional electron transfer in photosystem I

The mechanism of charge separation in PS I was extensively studied by construction of various site-specific mutants altering the A- and B-branches, mainly near the third Chl3A/Chl3B (Cohen et al. 2004; Dashdorj et al. 2005; Gibasiewicz et al. 2003; Guergova-Kuras et al. 2001; Ramesh et al. 2004; Ramesh et al. 2007; Santabarbara et al. 2010, 2005; Giera et al. 2009; Li et al. 2006; Müller et al. 2010; Sun et al. 2014), and to a lesser degree, near the second Chl2A/Chl2B (Badshah et al. 2018; Cherepanov et al. 2021) monomers in the RC. The data unequivocally indicate the involvement of both branches of cofactors in the electron transfer. Two models of the bidirectional mechanism were proposed to rationalize the observations: the “donor-side equilibrium model” and the “branch competition model” (Li et al. 2006). In the first, the reaction center may adopt two alternative conformations, which regulate the direction of electron transfer down the A- or B-branch, respectively. In the “branch competition model”, both branches compete for electrons, so an effective redistribution of electron density between the branches occurs before the reduction of phylloquinone in one of the A1A or A1B sites. The results obtained with the first group of mutants support the “branch competition model”, but the analysis performed by (Badshah et al. 2018) is more consistent with the “donor-side equilibrium model”, where the relative activity of two branches is determined by the relative populations of two conformational states.

To resolve this uncertainty, the formation of charge transfer (CT) states and symmetry breaking in the two branches of cofactors was studied in the PS I complexes from T. elongatus and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 by measuring the electrochromic Stark shift of β-carotene absorption in the spectral range of 500–510 nm (Cherepanov et al. 2020a). The formation of the primary ion-radical state P700+A1− in the PS I complex form T. elongatus was monitored by carotenoid bandshift at 498 nm, it occurred at 40 ps being controlled by energy transfer from the LWC to P700. In the PS I from Synechocystis 6803, the excitation at 720 nm produced an immediate bidentate bleach at 690/704 nm and synchronous carotenoid response at 508 nm. The bidentate bleach was assigned to the formation of primary ion-radical state P700+Chl2−, where negative charge is localized predominantly at the accessory chlorophyll molecule in the branch B, Chl2B. The following decrease of carotenoid signal at ~5 ps was ascribed to electron transfer to the more distant Chl3. The reduction of phylloquinone in the sites A1A and A1B was accompanied by a synchronous blue shift of the carotenoid response to 498 nm, pointing to fast redistribution of unpaired electron between two branches in favor of the state PB+A1A−.

The ultrafast generation of CT-states was also studied in the PS I from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, where the electronic properties of Chl2A and Chl2B monomers were genetically altered by substitutions of the PsaA-N600 or PsaB-N582 residues (which ligate Chl2B or Chl2A through a H2O molecule) with Met, His, and Leu, respectively (Badshah et al. 2018). Ultrafast experiments on branch-specific complementary mutants of the RC open the unique possibility to distinguish between the two highly symmetrical branches of redox cofactors. The transient absorption spectra of the six PS I variants measured at a time delay of 100 fs were quantified using the principal component analysis, which allowed determination of the mutation-induced shift of the equilibrium between the excited primary donor P700* and the primary charge-separated state P700+Chl2− in the PS I complexes with the altered Chl2A and Chl2B monomers (Cherepanov et al. 2021). The multi-exponential deconvolution of the absorption changes by the model (11) with distributed parameters revealed that the electron transfer reactions in the PsaA-N600M, PsaA-N600H, and PsaA-N600L variants (altering the Chl2B monomer in the B-branch) are similar to those of the wild-type, while the PsaB-N582M, PsaB-N582H, and PsaB-N582L variants (altering the Chl2A monomer in the A-branch) cause significant alterations of the photochemical processes. A redistribution of the electron density between the second and the third monomers Chl2A/Chl2B and Chl3A/Chl3B was detected in the time range of 9–20 ps, and the subsequent reduction of phylloquinone in the A1 sites was found out in the time range of 24–70 ps (Cherepanov et al. 2021). The results confirm the “branch competition model”, where the excited state (Chl2APAPBChl2B)* of symmetric tetrameric exciplex is quantum mechanically mixed with two symmetrical CT states P700+Chl2A− and P700+Chl2B− and the unpaired electron is shared between Chl2A-Chl3A and Chl2B-Chl3B cofactors before reduction of phylloquinone in either A1A or A1B sites (Fig. 1B).

Energetics of primary processes in photosystem I

Due to the extremely low operating redox potential of the primary charge-transfer intermediates in PS I, direct experimental determination of their energy levels is impossible: only the oxidation midpoint potential of the special pair, Em(P700) = +0.45 V (Brettel and Leibl 2001), and the reduction potentials of the iron-sulfur clusters, Em(FA/B) = −0.50 V (Golbeck et al. 1987) and Em(FX) = −0.61 V (Parrett et al. 1989), were measured by direct redox titration. Two alternative approaches were applied to estimate the energy levels of the primary and secondary ion-radical pairs. The energy of the secondary ion-radical pair, P700+A1−, was estimated by the thermally activated charge recombination of the terminal P700+FA/B− state

| 13 |

Using the observed recombination rate k0 = 8 s−1 at room temperature and the known rate of direct charge recombination from the phylloquinone in the A1A site k1 = 9 ×103 s−1, a simple equilibrium consideration gives the energy gap ΔG1 = 0.15–0.19 eV (see the energy scheme in Fig. 6), and the reduction potential of A1 in the range of −0.68 V (Brettel 1997; Milanovsky et al. 2017).

Fig. 6.

Free energy levels of various electronic states in the cyanobacterial PS I. Arrows indicate main electronic transitions. Operating redox potentials of the cofactors participating in charge separation are shown on the vertical axis vs SHE

The energy of the primary ion-radical pair P700+A0− relative to the excited state of PS I (denoted as RC* in Fig. 6) was estimated by analyzing the equilibrium of photoinduced energy transfer, charge separation, and backward recombination processes. Estimates of the respective free energy gap ΔG3 varied between 0.16 eV (Kleinherenbrink et al. 1994) and considerably smaller values of 10–40 meV (Giera et al. 2010; Holzwarth et al. 2005; Cherepanov et al. 2020a). The energy gap ΔG3 for the primary ion-radical pair formation is related to the quantum energy hν0, the difference of midpoint redox potentials of the donor and acceptor, and the electrostatic interaction of the donor and acceptor Δφ0:

| 14 |

where qe is the elementary charge. The electrostatic interaction of P700+ and A0− has magnitude of 0.25 V (Brettel 1997; Ptushenko et al. 2008), so the Δφ0 term should be included in the operating potential of A0 to distinguish it from the equilibrium midpoint potential (Brettel 1997; Ptushenko et al. 2008). Taking the interaction Δφ0 of 0.24 V, the free energy change ΔG2 for the A0 → A1 electron transfer has a magnitude of 0.35–0.4 eV.

Several attempts have been made to estimate the PS I energy in various approximations using ab initio DFT calculations (Heimdal et al. 2007; Renaud et al. 2013; Torres et al. 2003), semi-continual electrostatics (Ishikita and Knapp 2003; Ishikita et al. 2006b, a; Ptushenko et al. 2008) and molecular dynamics (Milanovsky et al. 2014) models. However, implementation of microscopic methods, being rigorous for small systems, requires too many approximations and simplifications for treatment of such a large systems as PS I. The principal drawback of ab initio calculations is a usage of the “absolute electrode potential”, which includes the solvation energy of hydrogen ion that depends on the water surface potential rather than on the chemical solvation energies (Krishtalik 2008; Pleskov 1987). Another difficulty of ab initio calculations is their critical sensitivity to the basis set size, difficulty in performing statistical averaging in a multidimensional configuration space, restrictions in the treatment of long-range electrostatic interactions.

The implementation of continual electrostatics and molecular dynamics simulations is based on the use of empirical parameters, such as the static and electronic permittivity of the protein, as well as on the midpoint redox potentials of cofactors in aprotic solvents (DMF, acetonitrile, etc.) The dielectric constants in semi-continual models depend on the definition and local protein properties, their adequate choice is a difficult task (Ptushenko et al. 2008; Warshel et al. 2006). The correct conversion of electrochemical data obtained for a cofactor in aprotic solvent relative to the standard calomel electrode (SCE) to the midpoint potential of the same cofactors in protein, measured relative to the standard hydrogen electrode in water (SHE), also represents a difficult methodological problem. Such conversion is possible only by using an extrathermodynamic assumption. The measured e.m.f. of the heterogeneous electrochemical cell is not equal to the difference between the two electrode potentials, because the cell includes a boundary between electrolyte solutions in DMF and H2O. At this boundary, a liquid junction potential (l.j.p.) arises as a result of nonequivalent distribution of cations and anions between the two phases due to the differences in their solvation energies. A common assumption is that the potential of the ferrocene Fc/Fc+ couple is the same in all solvents (Lewandowski et al. 2009). Ignoring l.j.p. when converting electrochemical measurements in aprotic solvents to the hydrogen electrode scale (Ishikita & Knapp 2003; Ishikita et al. 2006a) results in an error of 340 mV (Ptushenko et al. 2008).

Conclusions

The primary charge separation in RCs of PS I occurs within the symmetric tetrameric exciplex Chl2APAPBChl2B in which the excited state (Chl2APAPBChl2B)* is quantum mechanically mixed with two charge-transfer states P700+Chl2A− and P700+Chl2B−.

The Chl2A/Chl2B strongly interact with adjacent Chl3A/Chl3B molecules, therefore the formation of P700+Chl2A− and P700+Chl2B− is accompanied by the electron redistribution between Chl2A/Chl2B and Chl3A/Chl3B with the formation of P700+A0− state in a sub-picosecond time range.

The electron redistribution between the two branches in favor of the A-branch takes place in the 2–5 ps time scale before the subsequent electron transfer to phylloquinones A1A and A1B.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Lomonosov Moscow State University Program of Development. Optical measurements were performed using core research facilities of FRCCP RAS (no. 1440743, 506694).

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Fedor E. Gostev, Ivan V. Shelaev, Mahir D. Mamedov, Arseniy V. Aybush, Alexey Yu. Semenov, Vladimir A. Shuvalov and Victor A. Nadtochenko. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Dmitry A. Cherepanov and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Fundings

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation Grant RSF 22–24-00705.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adolphs J, Müh F, Madjet MEA, et al. Structure-based calculations of optical spectra of photosystem I suggest an asymmetric light-harvesting process. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3331–3343. doi: 10.1021/ja9072222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar P, Lambrev PH. On the spectral properties and excitation dynamics of long-wavelength chlorophylls in higher-plant photosystem I. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2020;1861:148274. doi: 10.1016/J.BBABIO.2020.148274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar P, Zhang C, Liu Z, et al. Excitation transfer and trapping kinetics in plant photosystem I probed by two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy. Photosynth Res. 2018;135:239–250. doi: 10.1007/s11120-017-0427-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar P, Caspy I, Nowakowski PJ, et al. Two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy of a minimal photosystem I complex reveals the rate of primary charge separation. J Am Chem Soc. 2021;143:14601–14612. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c05010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badshah SL, Sun J, Mula S, et al. Mutations in algal and cyanobacterial photosystem I that independently affect the yield of initial charge separation in the two electron transfer cofactor branches. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2018;1859:42–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard M, Martin I, Holzwarth AR. Kinetic modelling of exciton migration in photosynthetic systems. (1) effects of pigment heterogeneity and antenna topography on exciton kinetics and charge separation yields. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 1991;1060:271–283. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(05)80317-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beechen JM, Ameloot M. Global and target analysis of complex decay phenomena. Instrum Sci Technol. 1985;14:379–402. doi: 10.1080/10739148508543585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berera R, van Grondelle R, Kennis JTM. Ultrafast transient absorption spectroscopy: principles and application to photosynthetic systems. Photosynth Res. 2009;101:105–118. doi: 10.1007/s11120-009-9454-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecht M, Radics V, Nieder JB, et al. Red antenna states of photosystem I from Synechocystis PCC 6803. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5536–5543. doi: 10.1021/BI800121T/ASSET/IMAGES/BI800121T.SOCIAL.JPEG_V03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brettel K. Electron transfer and arrangement of the redox cofactors in photosystem I. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 1997;1318:322–373. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(96)00112-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brettel K, Leibl W. Electron transfer in photosystem I. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2001;1507:100–114. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(01)00202-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüggemann B, Sznee K, Novoderezhkin V, et al. From structure to dynamics: modeling Exciton dynamics in the photosynthetic antenna PS1. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:13536–13546. doi: 10.1021/JP0401473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byrdin M, Rimke I, Schlodder E, et al. Decay kinetics and quantum yields of fluorescence in photosystem I from Synechococcus elongatus with P700 in the reduced and oxidized state: are the kinetics of excited state decay trap-limited or transfer-limited? Biophys J. 2000;79:992–1007. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76353-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrdin M, Jordan P, Krauss N, et al. Light harvesting in photosystem I: modeling based on the 2.5-Å structure of photosystem I from Synechococcus elongatus. Biophys J. 2002;83:433–457. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75181-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet A, Dashdorj N, Golbeck JH, et al. Spectral resolution of the primary electron acceptor A0 in photosystem I. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:3380–3386. doi: 10.1021/jp211246a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y-C, Mančal T, Engel GS, et al. Evidence for wavelike energy transfer through quantum coherence in photosynthetic systems. Nature. 2007;446:782–786. doi: 10.1038/nature05678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenu A, Scholes GD. Coherence in energy transfer and photosynthesis. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2015;66:69–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040214-121713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov DA, Krishtalik LI, Mulkidjanian AY. Photosynthetic electron transfer controlled by protein relaxation: analysis by Langevin stochastic approach. Biophys J. 2001;80:1033–1049. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov DA, Shelaev IV, Gostev FE, et al. Mechanism of adiabatic primary electron transfer in photosystem I: femtosecond spectroscopy upon excitation of reaction center in the far-red edge of the Q Y band. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2017;1858:895–905. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov DA, Shelaev IV, Gostev FE, et al. Excitation of photosystem i by 760 nm femtosecond laser pulses: transient absorption spectra and intermediates. J Phys B Atomic Mol Phys. 2017;50:174001. doi: 10.1088/1361-6455/aa824b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov DA, Milanovsky GE, Gopta OA, et al. Electron–phonon coupling in Cyanobacterial photosystem I. J Phys Chem B. 2018;122:7943–7955. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b03906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov DA, Shelaev IV, Gostev FE, et al. Symmetry breaking in photosystem I: ultrafast optical studies of variants near the accessory chlorophylls in the A- and B-branches of electron transfer cofactors. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2020;20:1209–1227. doi: 10.1007/s43630-021-00094-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov DA, Brady NG, Shelaev IV, et al. PSI-SMALP, a detergent-free Cyanobacterial photosystem I, reveals faster femtosecond photochemistry. Biophys J. 2020;118:337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.11.3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov DA, Shelaev IV, Gostev FE et al (2020c) Generation of ion-radical chlorophyll states in the light-harvesting antenna and the reaction center of cyanobacterial photosystem I. Photosynth Res 1–19. 10.1007/s11120-020-00731-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cherepanov DA, Shelaev IV, Gostev FE et al (2020d) Evidence that chlorophyll f functions solely as an antenna pigment in far-red-light photosystem I from Fischerella thermalis PCC 7521. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1861. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2020.148184 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cherepanov DA, Shelaev IV, Gostev FE, et al. Primary charge separation within the structurally symmetric tetrameric Chl2APAPBChl2B chlorophyll exciplex in photosystem I. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2021;217:112154. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2021.112154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RO, Shen G, Golbeck JH, et al. Evidence for asymmetric Electron transfer in Cyanobacterial photosystem I: analysis of a methionine-to-Leucine mutation of the ligand to the primary Electron acceptor A0. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4741–4754. doi: 10.1021/bi035633f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashdorj N, Xu W, Martinsson P, et al. Electrochromic shift of chlorophyll absorption in photosystem I from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803: a probe of optical and dielectric properties around the secondary electron acceptor. Biophys J. 2004;86:3121–3130. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74360-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashdorj N, Xu W, Cohen RO, et al. Asymmetric electron transfer in cyanobacterial photosystem I: charge separation and secondary electron transfer dynamics of mutations near the primary electron acceptor A0. Biophys J. 2005;88:1238–1249. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.050963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato MD, Stahl AD, Van Stokkum IHM, et al. Cofactors involved in light-driven charge separation in photosystem I identified by subpicosecond infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2011;50:480–490. doi: 10.1021/bi101565w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esbensen KH, Geladi P. Comprehensive Chemometrics. Elsevier; 2009. Principal component analysis: concept, geometrical interpretation, mathematical background, algorithms, history, practice; pp. 211–226. [Google Scholar]

- Fromme P, Jordan P, Krauß N. Structure of photosystem I. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2001;1507:5–31. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(01)00195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller FD, Pan J, Gelzinis A, et al. Vibronic coherence in oxygenic photosynthesis. Nat Chem. 2014;6:706–711. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaimo JM, Gusev AV, Wasielewski MR. Excited-state symmetry breaking in cofacial and linear dimers of a green perylenediimide chlorophyll analogue leading to ultrafast charge separation. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:8530–8531. doi: 10.1021/ja026422l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibasiewicz K, Ramesh VM, Melkozernov AN, et al. Excitation dynamics in the core antenna of PS I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii CC 2696 at room temperature. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:11498–11506. doi: 10.1021/jp012089g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibasiewicz K, Ramesh VM, Lin S, et al. Excitonic interactions in wild-type and mutant PSI reaction centers. Biophys J. 2003;85:2547–2559. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74677-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giera W, Gibasiewicz K, Ramesh VM, et al. Electron transfer from A0̄ to A1 in photosystem i from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii occurs in both the a and B branch with 25-30-ps lifetime. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2009;11:5186–5191. doi: 10.1039/b822938d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giera W, Ramesh VM, Webber AN, et al. Effect of the P700 pre-oxidation and point mutations near A0 on the reversibility of the primary charge separation in photosystem I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2010;1797:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giera W, Szewczyk S, McConnell MD, et al. Uphill energy transfer in photosystem I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Time-resolved fluorescence measurements at 77 K. Photosynth Res. 2018;137:321–335. doi: 10.1007/s11120-018-0506-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisriel C, Shen G, Kurashov V, et al. The structure of photosystem I acclimated to far-red light illuminates an ecologically important acclimation process in photosynthesis. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaay6415. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aay6415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobets B, Van Grondelle R. Energy transfer and trapping in photosystem I. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2001;1507:80–99. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(01)00203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobets B, Kennis JTM, Ihalainen JA, et al. Excitation energy transfer in dimeric light harvesting complex I: a combined streak-camera/fluorescence upconversion study. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:10132–10139. doi: 10.1021/jp011901c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gobets B, van Stokkum IH, Rögner M, et al. Time-resolved fluorescence emission measurements of photosystem I particles of various cyanobacteria: a unified compartmental model. Biophys J. 2001;81:407–424. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75709-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golbeck JH, Parrett KG, McDermott AE. Photosystem I charge separation in the absence of center a and B. III. Biochemical characterization of a reaction center particle containing P-700 and FX. BBA - Bioenerg. 1987;893:149–160. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(87)90034-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka M, Cherepanov DA, Semenov AY, Golbeck JH. Control of electron transfer by protein dynamics in photosynthetic reaction centers. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;55:425–468. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2020.1810623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka M, Baldansuren A, Malnati A, et al. Shedding light on primary donors in photosynthetic reaction centers. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:2776. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.735666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka M, Charles P, Kalendra V et al (2021b) A dimeric chlorophyll electron acceptor differentiates type I from type II photosynthetic reaction centers. iScience 24. 10.1016/j.isci.2021b.102719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Goyal A, Szewczyk S, Burdziński G, et al. Competition between intra-protein charge recombination and electron transfer outside photosystem I complexes used for photovoltaic applications. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2022;21:319–336. doi: 10.1007/S43630-022-00170-X/FIGURES/7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guergova-Kuras M, Boudreaux B, Joliot A, et al. Evidence for two active branches for electron transfer in photosystem I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4437–4442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081078898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings G, Kleinherenbrink FAMM, Lin S, et al. Observation of the reduction and Reoxidation of the primary Electron acceptor in photosystem I. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3193–3200. doi: 10.1021/bi00177a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings G, Kleinherenbrink FAM, Lin S, Blankenship RE. Time-resolved fluorescence and absorption spectroscopy of photosystem I. Biochemistry. 2002;33:3185–3192. doi: 10.1021/BI00177A007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimdal J, Jensen KP, Devarajan A, Ryde U. The role of axial ligands for the structure and function of chlorophylls. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2007;12:49–61. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0164-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herascu N, Hunter MS, Shafiei G, et al. Spectral hole burning in Cyanobacterial photosystem i with P700 in oxidized and neutral states. J Phys Chem B. 2016;120:10483–10495. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b07803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzwarth AR, Schatz G, Brock H, Bittersmann E. Energy transfer and charge separation kinetics in photosystem I: part 1: picosecond transient absorption and fluorescence study of cyanobacterial photosystem I particles. Biophys J. 1993;64:1813–1826. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81552-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzwarth AR, Müller MG, Niklas J, Lubitz W. Charge recombination fluorescence in photosystem I reaction centers from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:5903–5911. doi: 10.1021/jp046299f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzwarth AR, Müller MG, Niklas J, Lubitz W. Ultrafast transient absorption studies on photosystem I reaction centers from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. 2: mutations near the P700 reaction center chlorophylls provide new insight into the nature of the primary electron donor. Biophys J. 2006;90:552–565. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.059824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihalainen JA, Rätsep M, Jensen PE, et al. Red spectral forms of chlorophylls in green plant PSI- a site-selective and high-pressure spectroscopy study. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:9086–9093. doi: 10.1021/jp034778t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ihalainen JA, Van Stokkum IHM, Gibasiewicz K, et al. Kinetics of excitation trapping in intact photosystem I of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2005;1706:267–275. doi: 10.1016/J.BBABIO.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikita H, Knapp E-W. Redox potential of quinones in both electron transfer branches of photosystem I. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52002–52011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikita H, Saenger W, Biesiadka J, et al. How photosynthetic reaction centers control oxidation power in chlorophyll pairs P680, P700, and P870. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9855–9860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601446103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikita H, Stehlik D, Golbeck JH, Knapp E-W. Electrostatic influence of PsaC protein binding to the PsaA/PsaB heterodimer in photosystem I. Biophys J. 2006;90:1081–1089. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.069781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan P, Fromme P, Witt HT, et al. Three-dimensional structure of cyanobaoterial photosystem I at 2.5 Å resolution. Nature. 2001;411:909–917. doi: 10.1038/35082000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khyasudeen MF, Nowakowski PJ, Nguyen HL, et al. Studying the spectral diffusion dynamics of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b using two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy. Chem Phys. 2019;527:110480. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphys.2019.110480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinherenbrink FAM, Hastings G, Blankenship RE, Wittmershaus BP. Delayed fluorescence from Fe-S type photosynthetic reaction centers at low redox potential. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3096–3105. doi: 10.1021/bi00176a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer T, Noack M, Reimers JR, et al. Energy flow in the photosystem I supercomplex: comparison of approximative theories with DM-HEOM. Chem Phys. 2018;515:262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphys.2018.05.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishtalik LII. The surface potential of solvent and the intraphase pre-existing potential. Russ J Electrochem. 2008;44:43–49. doi: 10.1134/S1023193508010072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumazaki S, Ikegami I, Furusawa H, et al. Observation of the excited state of the primary Electron donor chlorophyll (P700) and the ultrafast charge separation in the spinach photosystem I reaction center. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:1093–1099. doi: 10.1021/jp003122m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurashov V, Gorka M, Milanovsky GE, et al. Critical evaluation of electron transfer kinetics in P700–FA/FB, P700–FX, and P700–A1 photosystem I core complexes in liquid and in trehalose glass. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2018;1859:1288–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.09.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laible PD, Zipfel W, Owens TG. Excited state dynamics in chlorophyll-based antennae: the role of transfer equilibrium. Biophys J. 1994;66:844–860. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80861-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski A, Waligora L, Galinski M. Ferrocene as a reference redox couple for aprotic ionic liquids. Electroanalysis. 2009;21:2221–2227. doi: 10.1002/elan.200904669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Van Der Est A, Lucas MG, et al. Directing electron transfer within photosystem I by breaking H-bonds in the cofactor branches. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2144–2149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506537103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madjet ME-A, Müh F, Renger T. Deciphering the influence of short-range electronic couplings on optical properties of molecular dimers: application to “special pairs” in photosynthesis. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:12603–12614. doi: 10.1021/jp906009j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malavath T, Caspy I, Netzer-El SY, et al. Structure and function of wild-type and subunit-depleted photosystem I in Synechocystis. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2018;1859:645–654. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malferrari M, Savitsky A, Lubitz W, et al. Protein immobilization capabilities of sucrose and Trehalose glasses: the effect of protein/sugar concentration unraveled by high-field EPR. J Phys Chem Lett. 2016;7:4871–4877. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b02449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazor Y, Nataf D, Toporik H, Nelson N. Crystal structures of virus-like photosystem I complexes from the mesophilic cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Elife. 2014;3:e01496. doi: 10.7554/elife.01496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazor Y, Borovikova A, Nelson N. The structure of plant photosystem I super-complex at 2.8A resolution. Nat Plants. 2017;3:17014. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon BH, Müller JD, Wraight CA, Nienhaus GU. Electron transfer and protein dynamics in the photosynthetic reaction center. Biophys J. 1998;74:2567–2587. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77964-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedev ES, Kotelnikov AI, Goryachev NS, et al. Protein dynamics control of electron transfer in reaction centers from Rps. Viridis. Mol Simul. 2006;32:735–750. doi: 10.1080/08927020600880802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melkozernov AN. Excitation energy transfer in photosystem I from oxygenic organisms. Photosynth Res. 2001;70:129–153. doi: 10.1023/A:1017909325669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melkozernov AN, Lin S, Blankenship RE. Excitation dynamics and heterogeneity of energy equilibration in the Core antenna of photosystem I from the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1489–1498. doi: 10.1021/bi991644q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melkozernov AN, Lin S, Blankenship RE. Femtosecond transient spectroscopy and Excitonic interactions in photosystem I. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:1651–1656. doi: 10.1021/jp993257w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melkozernov AN, Lin S, Schmid VHR, et al. Ultrafast excitation dynamics of low energy pigments in reconstituted peripheral light-harvesting complexes of photosystem I. FEBS Lett. 2000;471:89–92. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melkozernov AN, Lin S, Blankenship RE, Valkunas L. Spectral inhomogeneity of photosystem I and its influence on excitation equilibration and trapping in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 at 77 K. Biophys J. 2001;81:1144–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75771-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melkozernov AN, Barber J, Blankenship RE. Light harvesting in photosystem I supercomplexes. Biochemistry. 2006;45:331–345. doi: 10.1021/BI051932O/ASSET/IMAGES/BI051932O.SOCIAL.JPEG_V03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milanovsky GE, Ptushenko VV, Golbeck JH, et al. Molecular dynamics study of the primary charge separation reactions in photosystem I: effect of the replacement of the axial ligands to the electron acceptor A0. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2014;1837:1472–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milanovsky GE, Petrova AA, Cherepanov DA, Semenov AY. Kinetic modeling of electron transfer reactions in photosystem I complexes of various structures with substituted quinone acceptors. Photosynth Res. 2017;133:185–199. doi: 10.1007/s11120-017-0366-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milanovsky G, Gopta O, Petrova A, et al. Multiple pathways of charge recombination revealed by the temperature dependence of electron transfer kinetics in cyanobacterial photosystem I. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2019;1860:601–610. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2019.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molotokaite E, Remelli W, Casazza AP, et al. Trapping dynamics in photosystem I-light harvesting complex I of higher plants is governed by the competition between excited state diffusion from low energy states and photochemical charge separation. J Phys Chem B. 2017;121:9816–9830. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b07064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller MG, Niklas J, Lubitz W, Holzwarth AR. Ultrafast transient absorption studies on photosystem I reaction centers from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. 1. A new interpretation of the energy trapping and early Electron transfer steps in photosystem I. Biophys J. 2003;85:3899–3922. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74804-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller MG, Slavov C, Luthra R, et al. Independent initiation of primary electron transfer in the two branches of the photosystem I reaction center. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4123–4128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905407107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler W, Marcus RA. Dynamical effects in electron transfer reactions. II. Numerical solution. J Chem Phys. 1987;86:3906–3924. doi: 10.1063/1.451951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson N. Evolution of photosystem i and the control of global enthalpy in an oxidizing world. Photosynth Res. 2013;116:145–151. doi: 10.1007/s11120-013-9902-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nürnberg DJ, Morton J, Santabarbara S, et al. Photochemistry beyond the red limit in chlorophyll f–containing photosystems. Science. 2018;360(80):1210–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.aar8313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens TG, Webbt SP, Mets L, et al. Antenna size dependence of fluorescence decay in the core antenna of photosystem I: estimates of charge separation and energy transfer rates. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1987;84:1532–1536. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.84.6.1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo G, Mallardi A, Hochkoeppler A, et al. Electron transfer kinetics in photosynthetic reaction centers embedded in trehalose glasses: trapping of conformational substates at room temperature. Biophys J. 2002;82:558–568. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75421-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pålsson L-OO, Flemming C, Gobets B, et al. Energy transfer and charge separation in photosystem I: P700 oxidation upon selective excitation of the long-wavelength antenna chlorophylls of Synechococcus elongatus. Biophys J. 1998;74:2611–2622. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77967-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrett KG, Mehari T, Warren PG, Golbeck JH. Purification and properties of the intact P-700 and Fx-containing photosystem I core protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;973:324–332. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(89)80439-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowicz NP, Groot ML, Van Stokkum IHM, et al. Charge separation and energy transfer in the photosystem II core complex studied by femtosecond midinfrared spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2007;93:2732–2742. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.105452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleskov YV. Comments on “the absolute potential of a standard hydrogen electrode: a new estimate” by H. Reiss and a. Heller J Phys Chem. 1987;91:1691–1692. doi: 10.1021/j100290a081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Proppe AH, Li YC, Aspuru-Guzik A, et al. Bioinspiration in light harvesting and catalysis. Nat Rev Mater. 2020;511(5):828–846. doi: 10.1038/s41578-020-0222-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher SW. An eigenfunction expansion method for the analysis of exponential decay curves. J Chem Phys. 1976;64:2772–2777. doi: 10.1063/1.432601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher SW. CONTIN: a general purpose constrained regularization program for inverting noisy linear algebraic and integral equations. Comput Phys Commun. 1982;27:229–242. doi: 10.1016/0010-4655(82)90174-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ptushenko VV, Cherepanov DA, Krishtalik LI, Semenov AY. Semi-continuum electrostatic calculations of redox potentials in photosystem I. Photosynth Res. 2008;97:55–74. doi: 10.1007/s11120-008-9309-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh VM, Gibasiewicz K, Lin S, et al. Bidirectional electron transfer in photosystem I: accumulation of A0- in a-side or B-side mutants of the axial ligand to chlorophyll A0. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1369–1375. doi: 10.1021/bi0354177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh VM, Gibasiewicz K, Lin S, et al. Replacement of the methionine axial ligand to the primary electron acceptor A0 slows the A0- reoxidation dynamics in photosystem I. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2007;1767:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rätsep M, Johnson TW, Chitnis PR, Small GJ. The red-absorbing chlorophyll a antenna states of photosystem I: a hole-burning study of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and its mutants. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:836–847. doi: 10.1021/jp9929418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renaud N, Powell D, Zarea M, et al. Quantum interferences and electron transfer in photosystem i. J Phys Chem A. 2013;117:5899–5908. doi: 10.1021/jp308216y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santabarbara S, Kuprov I, Fairclough WV, et al. Bidirectional electron transfer in photosystem I: determination of two distances between P700+ and A1- in spin-correlated radical pairs. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2119–2128. doi: 10.1021/bi048445d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santabarbara S, Kuprov I, Poluektov O, et al. Directionality of electron-transfer reactions in photosystem i of prokaryotes: universality of the bidirectional electron-transfer model. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:15158–15171. doi: 10.1021/jp1044018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savikhin S, Jankowiak R. Mechanism of primary charge separation in photosynthetic reaction centers. In: Golbeck J, van der Est A, editors. The biophysics of photosynthesis. New York: Springer; 2014. pp. 193–240. [Google Scholar]

- Savikhin S, Xu W, Soukoulis V, et al. Ultrafast primary processes in photosystem I of the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biophys J. 1999;76:3278–3288. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77480-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savikhin S, Xu W, Chitnis PR, Struve WS. Ultrafast primary processes in PS I from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803: roles of P700 and A0. Biophys J. 2000;79:1573–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76408-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savikhin S, Xu W, Martinsson P, et al. Kinetics of charge separation and A0- → A1 Electron transfer in photosystem I reaction centers. Biochemistry. 2001;40:9282–9290. doi: 10.1021/bi0104165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle GFW, Tamkivi R, Van Hoek A, Schaafsma TJ (1988) Temperature dependence of antennae chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics in photosystem I reaction Centre protein. J Chem Soc Faraday Trans 2 Mol Chem Phys:315–327. 10.1039/F29888400315

- Segtnan VH, Šašić Š, Isaksson T, Ozaki Y. Studies on the structure of water using two-dimensional near-infrared correlation spectroscopy and principal component analysis. Anal Chem. 2001;73:3153–3161. doi: 10.1021/ac010102n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelaev IV, Gostev FE, Mamedov MD, et al. Femtosecond primary charge separation in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 photosystem I. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2010;1797:1410–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkarev V (2006) Functional modeling of Electron transfer in photosynthetic reaction centers. Photosyst I Light PlastocyaninFerredoxin Oxidoreductase 611–637. 10.1007/978-1-4020-4256-0_36

- Shuvalov VA, Yakovlev AG, Vasilieva LG, Shkuropatov AY. Primary charge separation between P700* and the primary Electron acceptor complex a-A0: A comparison with bacterial reaction centers. In: Golbeck JH, editor. Photosystem I. Netherlands: Springer; 2007. pp. 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Silori Y, Chawla S, De AK. Unravelling the role of water in ultrafast excited-state relaxation dynamics within Nano-architectures of chlorophyll a. ChemPhysChem. 2020;21:1908–1917. doi: 10.1002/cphc.202000487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavov C, Ballottari M, Morosinotto T, et al. Trap-limited charge separation kinetics in higher plant photosystem i complexes. Biophys J. 2008;94:3601–3612. doi: 10.1529/BIOPHYSJ.107.117101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smitienko OA, Feldman TB, Petrovskaya LE et al (2021) Comparative femtosecond spectroscopy of primary photoreactions of Exiguobacterium sibiricum rhodopsin and Halobacterium salinarum Bacteriorhodopsin. J Phys Chem B. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c07763 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Steinbach PJ, Ionescu R, Robert Matthews C. Analysis of kinetics using a hybrid maximum-entropy/nonlinear-least-squares method: application to protein folding. Biophys J. 2002;82:2244–2255. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75570-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi H, Marcus RA. Dynamical effects in electron transfer reactions. J Chem Phys. 1986;84:4894–4914. doi: 10.1063/1.449978. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Hao S, Radle M, et al. Evidence that histidine forms a coordination bond to the A0A and A0B chlorophylls and a second H-bond to the A1A and A1B phylloquinones in M688HPsaA and M668HPsaB variants of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2014;1837:1362–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres RA, Lovell T, Noodleman L, Case DA. Density functional and reduction potential calculations of Fe4S4 clusters. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1923–1936. doi: 10.1021/ja0211104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]